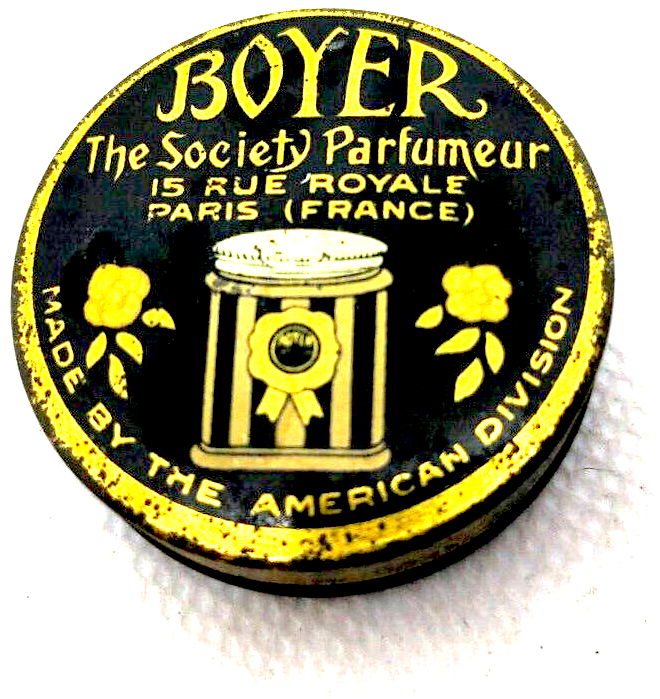

Museum Artifacts: Boyer “Flowers of Beauty” and No. 34 Face Powder, 1930s-40s

Made By: Boyer Chemical Laboratory Co. / Boyer International Laboratories, Inc., 2700 S. Wabash Ave., Chicago, IL [Douglas]

“In France are the great masters of the art of perfumery and preparations for beauty. Nowhere else in the world is the art as highly developed or the materials available as fine or rare in quality. My ambition has been to send the products of this art to America, and my American Division is the result of this ambition.” —promotional flier for Boyer, ‘The Society Parfumeur,’ 1928

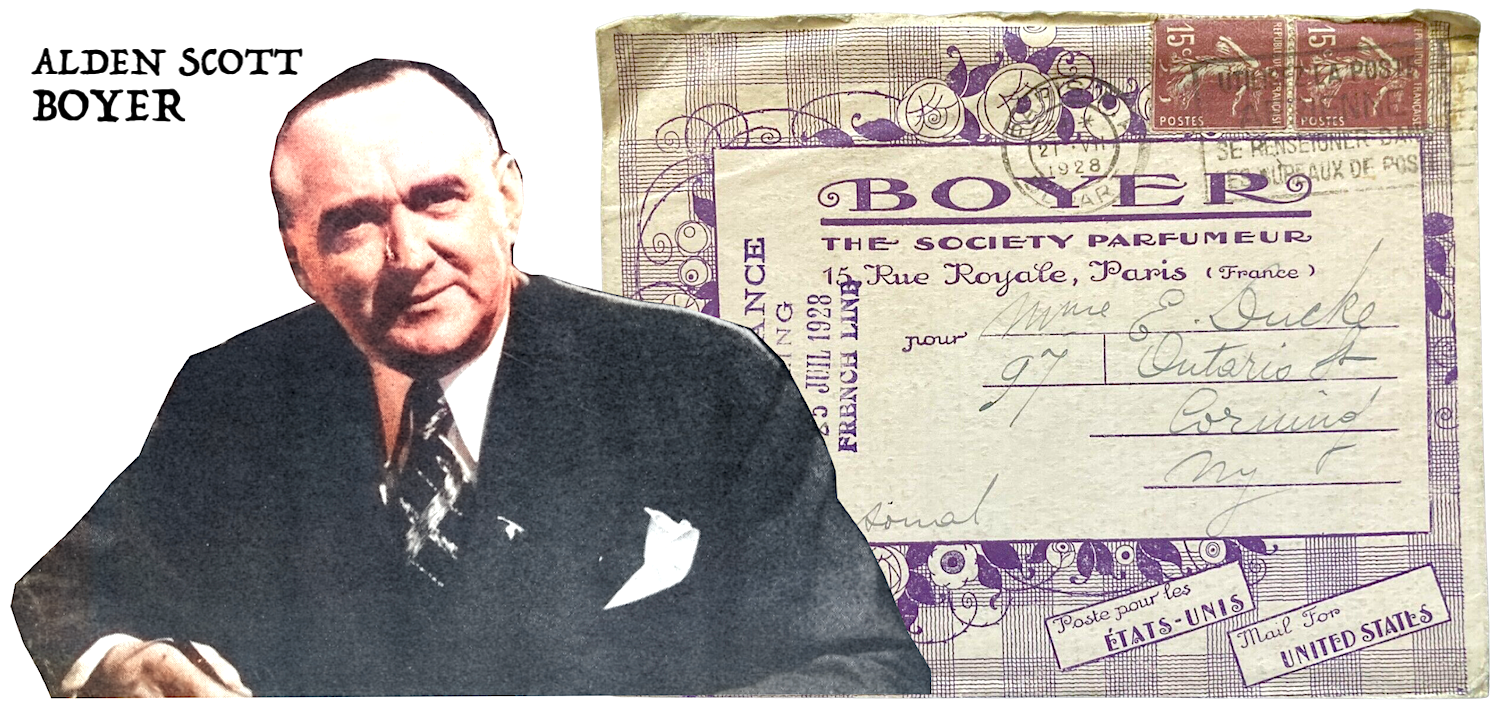

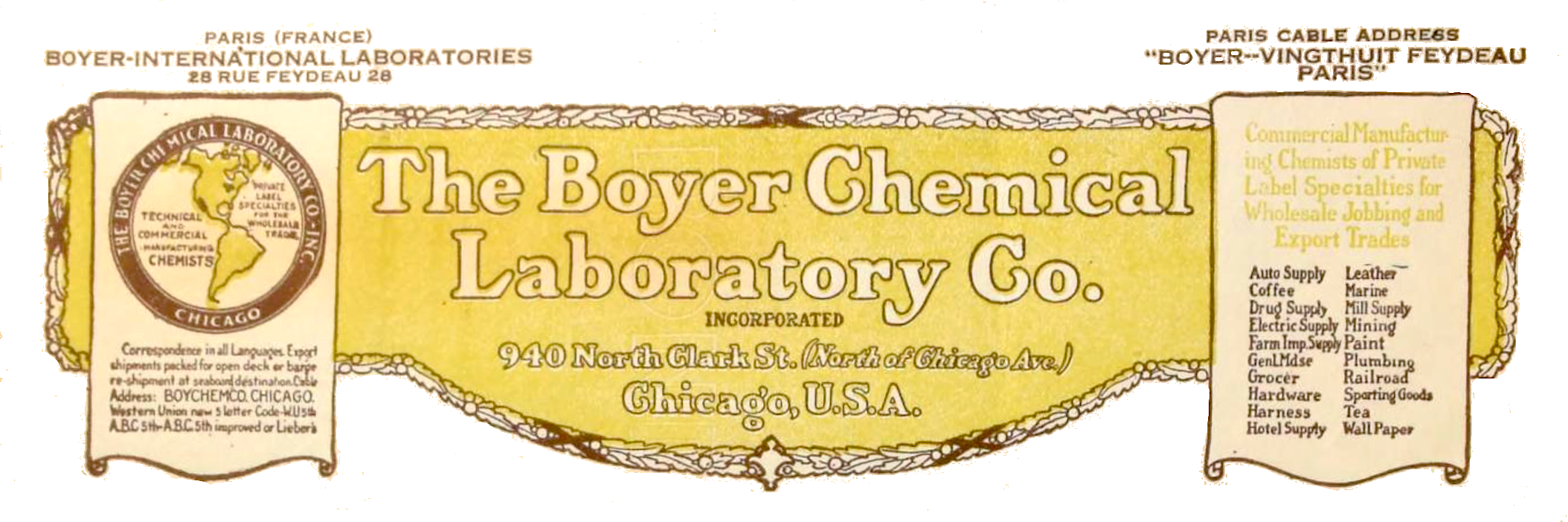

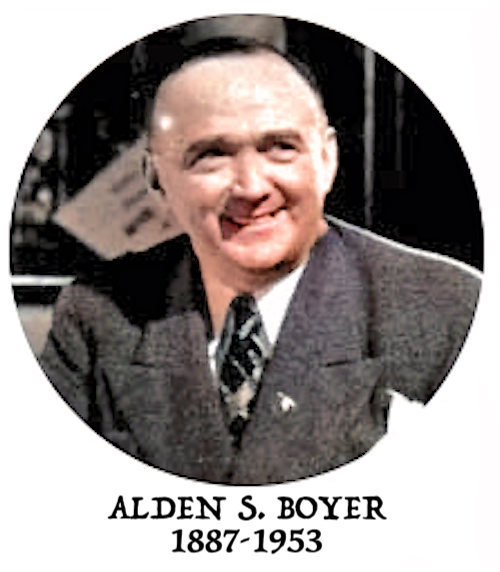

The Boyer Chemical Company—sometimes known as the Boyer Chemical Works, Boyer International Laboratories, or half a dozen other similarly authoritative-sounding designations—was a small Chicago toiletries manufacturer that portrayed itself (at least for a while) as a sophisticated French perfumery. It was a marketing approach that made sense in the 1920s as much as it would today, considering the American public’s magnetic pull toward anything cosmetically “Parisian.” In the mind of company president Alden Scott Boyer, however, there was nothing cynical or misleading about calling himself “The Society Parfumeur” . . . even if he was actually a working class kid from Iowa.

The Boyer Chemical Company—sometimes known as the Boyer Chemical Works, Boyer International Laboratories, or half a dozen other similarly authoritative-sounding designations—was a small Chicago toiletries manufacturer that portrayed itself (at least for a while) as a sophisticated French perfumery. It was a marketing approach that made sense in the 1920s as much as it would today, considering the American public’s magnetic pull toward anything cosmetically “Parisian.” In the mind of company president Alden Scott Boyer, however, there was nothing cynical or misleading about calling himself “The Society Parfumeur” . . . even if he was actually a working class kid from Iowa.

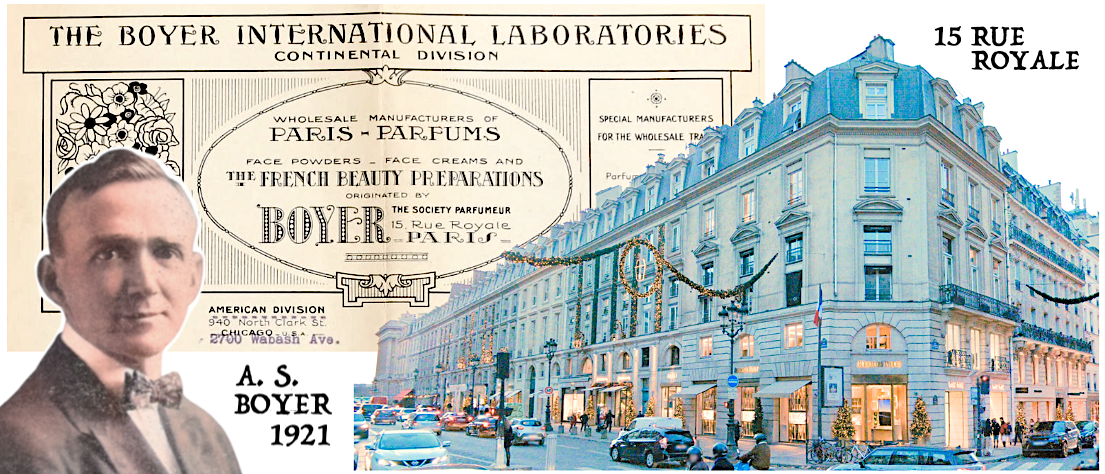

“This year, we had a beautiful spring here in Paris,” Boyer wrote in a 1926 letter to his hometown newspaper. “The second crop of flowers are now in full bloom along the boulevards. The apple and cherry blossom time has come and gone. . . . The Rue Royale, where our city establishment is located, is in the center of the fashion section. . . . In popularity at the Ritz, the Continental, and the Claridge Hotels, gowns of black and white seem to be in the greatest prominence. I saw a new and striking black-red creation which I understand came from Chanel’s. The shade is almost like the inside of a black cherry.”

This type of flowery language—rife with name-dropping and humble-braggery—was very typical of both Alden Scott Boyer’s marketing copy and personal correspondence; every word seemingly selected to reinforce the image of a highly cultured man thriving in the epicenter of all things glitzy and chic. Similar sounding men of this period were usually selling snake oil, but should we presume the same about Boyer?

The short answer is, “maybe not.”

A Chicago cosmetics dealer claiming to have “an establishment in Paris” might feel akin to a Chicago high schooler having a “girlfriend in Canada.” But, as best we can tell, Boyer and his wife Marie really did enjoy a cross-Atlantic life, establishing a second, seasonal home at 15 Rue Royale, according to a 1926 directory of “Americans in France.” The Boyer business operated out of this same address, maintaining offices and a purported “laboratory” in the heart of Paris, while factory production was handled by the company’s “American Division” in Chicago.

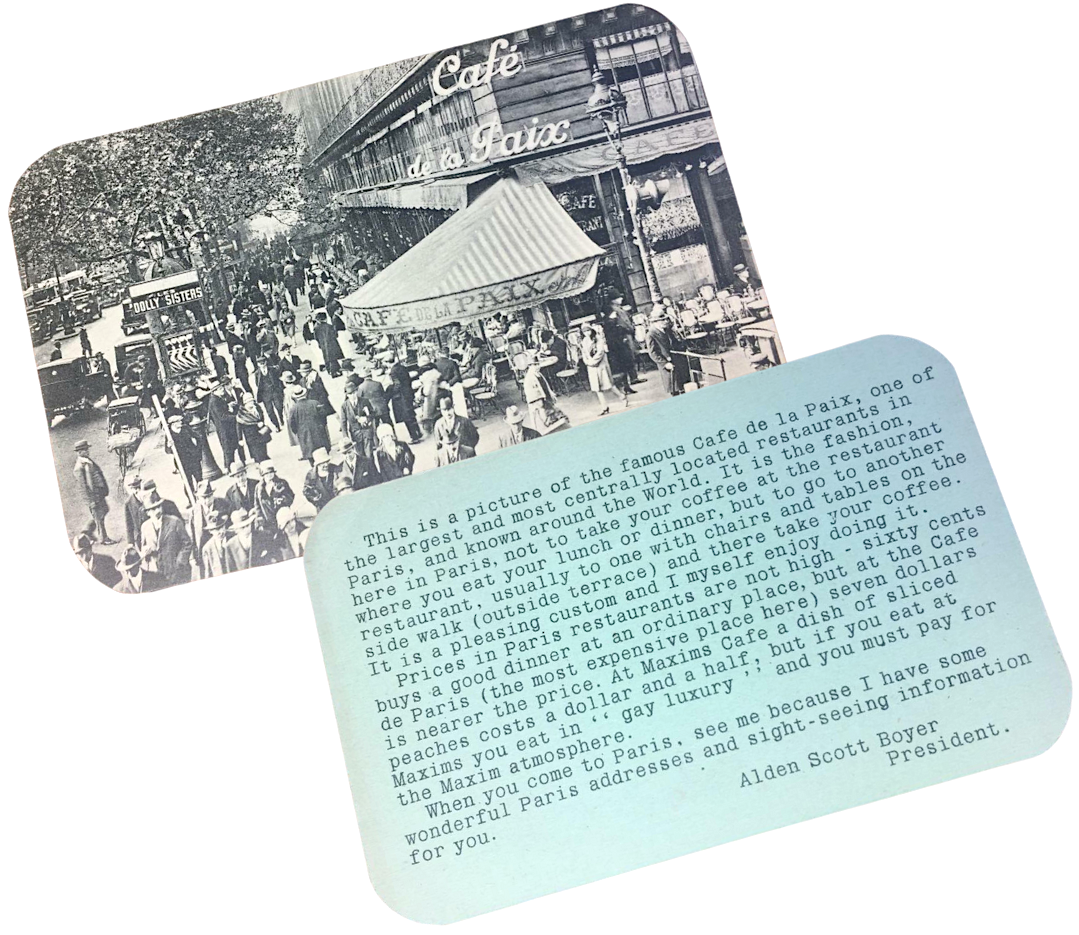

The customer base for Boyer’s products, of course, was also primarily American, and great effort was put into earning their loyalty. If you purchased an article such as Boyer’s “Flowers of Beauty” Face Powder, for example, you could expect to receive additional promotional materials direct from the “Society Parfumeur,” Boyer’s continental alter-ego, communicating the cultural identity of the brand. Sent via mail from France in fancy envelopes, these packets included Parisian postcards (often highlighting one of Alden’s favorite local restaurants) and long-winded newsletters, waxing poetic about all things cosmetic and cosmopolitan in the City of Light. The return address and foreign stamps always seemed to confirm the authenticity of Boyer’s glamorous claims. The Parfumeur couldn’t seem to help himself, though, from going over the top—stamping the names of famous Atlantic steamer ships on many of the envelopes just to give them extra cache.

“There is no evidence that any of Boyer’s mail was actually carried by the named steamers,” researcher David Jennings-Bramly wrote in a 2010 edition of the Journal of the France & Colonies Philatelic Society. “Indeed, some have Paris postmarks dated days after the ships’ quoted departure dates.”

Jennings-Bramly goes as far as to call Alden Scott Boyer a likely “flim flam man,” i.e. a con-man, huckster, etc.

Jennings-Bramly goes as far as to call Alden Scott Boyer a likely “flim flam man,” i.e. a con-man, huckster, etc.

While he may have started out in his career as a country-boy pretender amidst the actual erudite poshos of Europe, however, Boyer’s interest in joining them doesn’t seem to have been motivated purely by ego or greed. He was, first and foremost, a professional appreciator, and his passion for the things he sold—and to a greater degree for the things he collected—was almost certainly genuine. Whether it was perfumes, old currency, stamps, coin-op machines, bicycles, postcards, antique books, or early photography, the kid from Iowa maintained a life-long, child-like fascination for curious objects, and was endlessly preoccupied with finding them. He served for years as president of the Chicago Coin Club and American Numismatic Association, and wrote regularly in the pages of Hobbies magazine. So big were his personal collections, in fact, that he eventually established the “Alden Scott Boyer Museum for the Preservation of American Curiosities” . . . though it notably never opened to the public.

Like many obsessive collectors, Boyer might have let his enthusiasm for “cool old stuff” occasionally cloud and/or define his own identity. But, we’re hardly in a position to judge. In fact, of all the manufacturers we’ve researched over the years, it’s hard to imagine any of them enjoying a visit to the Made In Chicago Museum more than Alden Scott Boyer.

History of the Boyer Chemical Co., Part I: The Cresco Kid

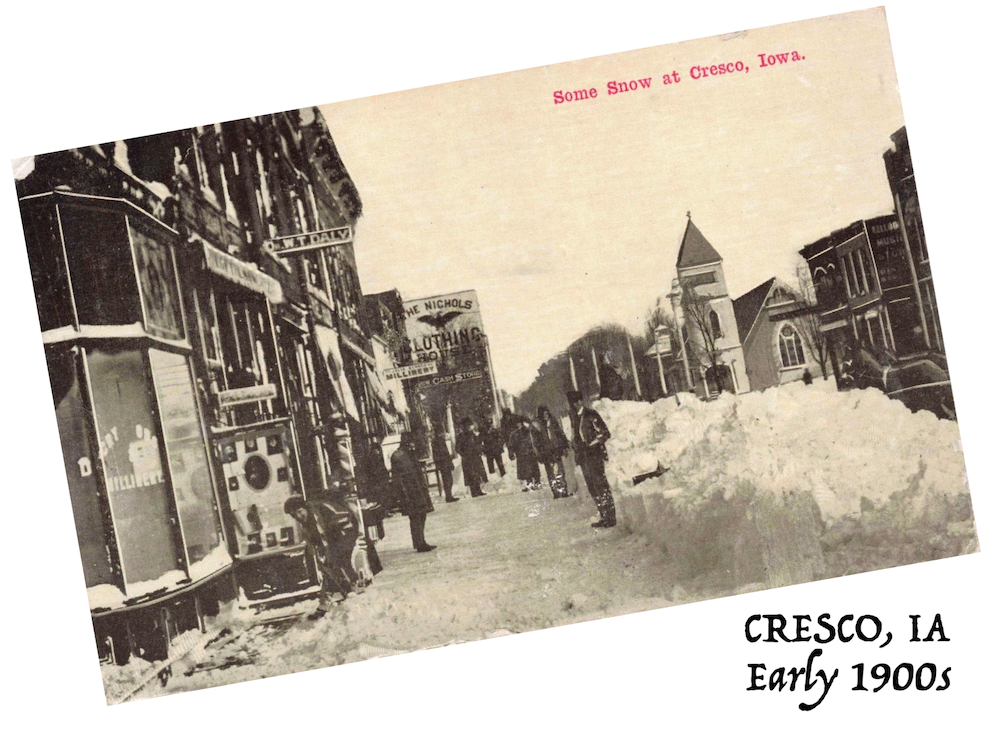

Boyer was born in 1887 in Cresco, Iowa, a railroad prairie town that was practically as new and as small as he was at the time. The local population reached about 2,000 by 1890 and hasn’t quite yet managed to double that mark over the ensuing 130 years. Cresco, if not in terms of literal mileage, was as far away from Paris as just about any place on Earth.

French culture, however, was not quite so alien to a young Alden as one might imagine. According to his own stories—and substantiated by at least a few census documents—Boyer’s father, Moses Albert Boyer, was a French-Canadian, hailing from some unspecified section of Quebec. Alden’s birth certificate goes a slight step further, citing his father’s nationality as simply “French.”

French culture, however, was not quite so alien to a young Alden as one might imagine. According to his own stories—and substantiated by at least a few census documents—Boyer’s father, Moses Albert Boyer, was a French-Canadian, hailing from some unspecified section of Quebec. Alden’s birth certificate goes a slight step further, citing his father’s nationality as simply “French.”

“For many generations, members of the Boyer family had been chemists, but the French father of Alden Scott Boyer chose to be a watchmaker,” the Cedar Rapids Gazette reported in a 1934 profile. “Coming to the United States, he was assigned to work in Cresco—fell in love with a girl of that town and married her. When their son was nine years old the French watchmaker died, but the boy chose to follow family traditions and become a chemist.”

The death of Moses Boyer in 1896, at just 36 years of age, left young Alden to grow up mostly in a woman’s world, raised by his widowed mother Cora alongside his younger sister Helen. At the risk of getting irresponsibly psycho-analytical, this loss almost certainly played a major role in Alden Scott Boyer’s later fascination with all things French, as he could have been seeking out a sort of re-connection to a lost part of his own heritage. The lifelong interest in collecting coins and other paraphernalia also had its roots in the same severed relationship.

“Mr. Boyer inherited his love of numismatics from his father, who was a collector,” the Numismatist (a coin collecting journal) reported in 1921. “He remembers, as a boy, being shown the paper issues of 1896 by his father, who pointed out to him the beautiful engraving on them.”

While still a small child, Alden started collecting advertising picture cards, and the excitement of the “quest” never really let up from that point forward.

“Passing through life,” he later told the Oak Park Camera Club, “I have made collections of colored baby ribbons, tobacco tags, stamps, coins and paper money, ancient books on chemistry, books on perfume manufacture, old perfume bottles, old bicycles, old automatic coin devices, early automobiles, books on early American travel, . . . and the history of photography.”

Long before he started collecting “ancient books” on the subject, chemistry was Boyer’s educational focus during his high school years in Cresco, and he parlayed that interest into a job at “the best drug store in town.”

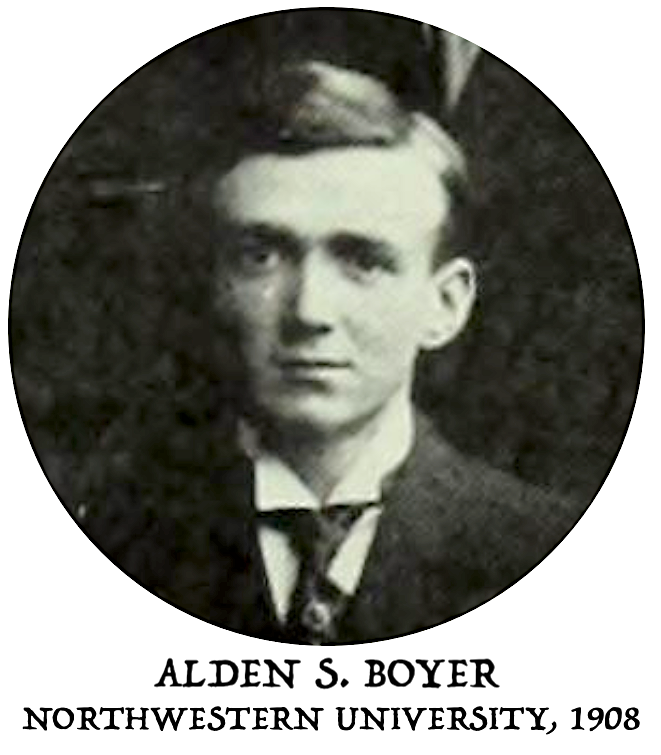

“Some time later,” according to the Numismatist, “with what he had saved and with help from his mother, he left Cresco for Chicago to go to college. He spent one year at the University of Illinois School of Pharmacy and Chemistry, and then two years at Northwestern University, graduating in 1908.”

“Some time later,” according to the Numismatist, “with what he had saved and with help from his mother, he left Cresco for Chicago to go to college. He spent one year at the University of Illinois School of Pharmacy and Chemistry, and then two years at Northwestern University, graduating in 1908.”

Going straight into business for himself, Boyer started up a pharmacy in Carpenter, Iowa; met and married his wife Marie (who shared his love for collecting); and eventually brought his bride back to Chicago in 1912, where he started, on a humble scale, a wholesale chemical manufacturing operation. This included concocting, bottling, or warehousing everything from spot removers and metal polishes to early automobile antifreeze.

The Boyer Chemical Laboratory Company, as it was soon known, had several addresses through the 1910s into the early ‘20s, including 2 E. Michigan Street, 11 W. Austin Ave., 18 E. Kinzie St., 12 W. Kinzie St., and 940 N. Clark Street; suggesting a time of gradual growth. But it wasn’t until 1919, shortly after the end of World War I, that Alden and Marie took a trip to Europe and conceptualized a more glamorous new direction for their chemical enterprise.

II. The Society Parfumeur

“There is one thing positive — there is one thing certain— the Women of Paris are ‘CHIC.’ There are no two ways about it. There is a ‘something’ about their appearance—it is so different . . . so distinctive. The reason is that the women of Paris know HOW to take care of their skin and THEY DO IT. It makes them beautiful. They know the secret.” —promotional flier from Boyer, the Society Parfumeur, 1928

While visiting Paris in the summer of 1919, Alden Scott Boyer didn’t just notice the ladies. In the garden of Napoleon, he happened to sniff some roses, as one does, and in this case, it apparently resulted in an instant olfactory epiphany.

While visiting Paris in the summer of 1919, Alden Scott Boyer didn’t just notice the ladies. In the garden of Napoleon, he happened to sniff some roses, as one does, and in this case, it apparently resulted in an instant olfactory epiphany.

“That’s the business for me—perfumes,” he exclaimed (according to his own recollections in the Cedar Rapids Gazette). “It’s a summer business, just what I need.”

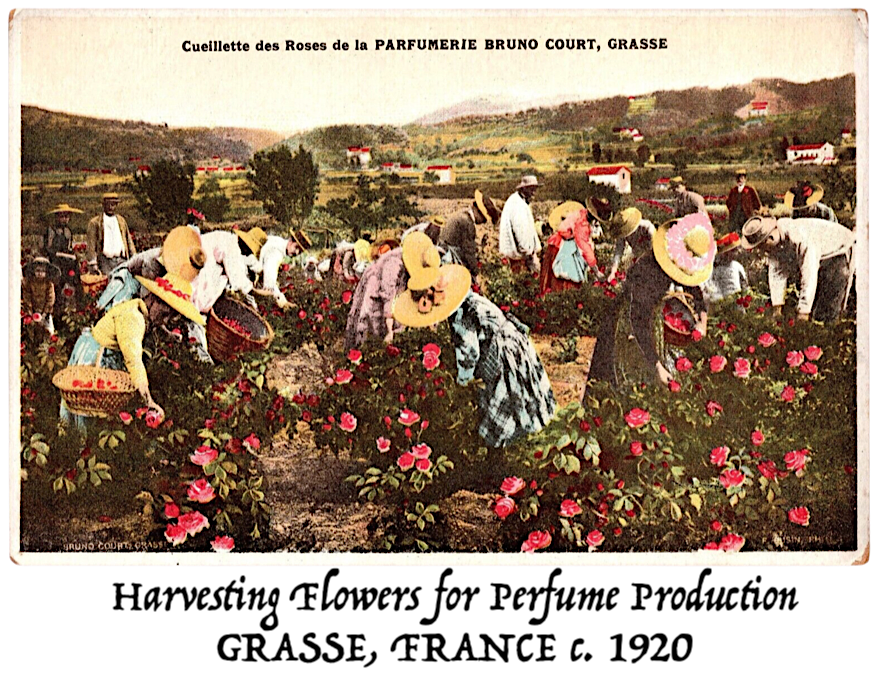

The story of how the “Society Parfumeur” entered this field and learned his craft is predictably ridiculous; involving a sagely French instructor and “dusty volumes of the past” in which Boyer found the inspiration for his own line of scents. In particular, Boyer claimed to have discovered a book containing the formulas of Roure & Bertrand, “manufacturers of famous perfume oils in Grasse, France” during the 1840s. Bertrand had supposedly published the secrets of the company after getting ousted from the partnership, and while a court order had led to the seizure and destruction of all copies of this work, Boyer had supposedly found one “amid a stack of old medical volumes in a bookstore near the Sorbonne.”

Again, this story—while a bit like a wannabe wizard finding an old book of spells— is still well within the range of plausibility when it comes to Boyer and his penchant for digging in the cobwebs. Importantly, he also knew how to weave a good story—true or true-ish— for marketing purposes.

Along with telling his American customers about the fashionable folk walking outside the new company office at 15 Rue Royale in Paris, Boyer routinely wrote about the town of Grasse in the South of France, as well. Inspired by its connection to Roure & Bertrand and other famous perfumeries, Boyer visited Grasse on regular pilgrimages.

“I was down in the South of France at Grasse for the Perfume Oil flower harvest, to secure the precious flower oils and odors that we use in our Preparations,” Boyer wrote in a company letter to customers in 1928. “. . . This is a trip that I have made before, but every time it seems to be more interesting. Our train stopped and picked up several carloads of orange blossoms for the perfume oil makers of Grasse. On the way the air in the train was perfumed by the wonderful odor emanating from these carloads of flowers.”

Boyer understood that, in order to sell the women of America on the quality of his new perfumes and face powders, he would first have to sell them on Alden Scott Boyer—the Society Parfumeur. As the old saying goes, it takes a Gwyneth Paltrow to make a Goop. The source, sometimes, matters more than the substance.

Boyer understood that, in order to sell the women of America on the quality of his new perfumes and face powders, he would first have to sell them on Alden Scott Boyer—the Society Parfumeur. As the old saying goes, it takes a Gwyneth Paltrow to make a Goop. The source, sometimes, matters more than the substance.

“Dear Madame: I have searched the world to secure the finest and most costly ingredients necessary to make this Face Powder for you,” read a small letter packaged with Boyer’s Flowers of Beauty Face Powder. “Here in my laboratory I have proven that better Face Powder than that found in this container cannot be made. . . . If Boyer ‘Flowers of Beauty’ pleases you, tell your friends about it and be sure and get this same brand again.”

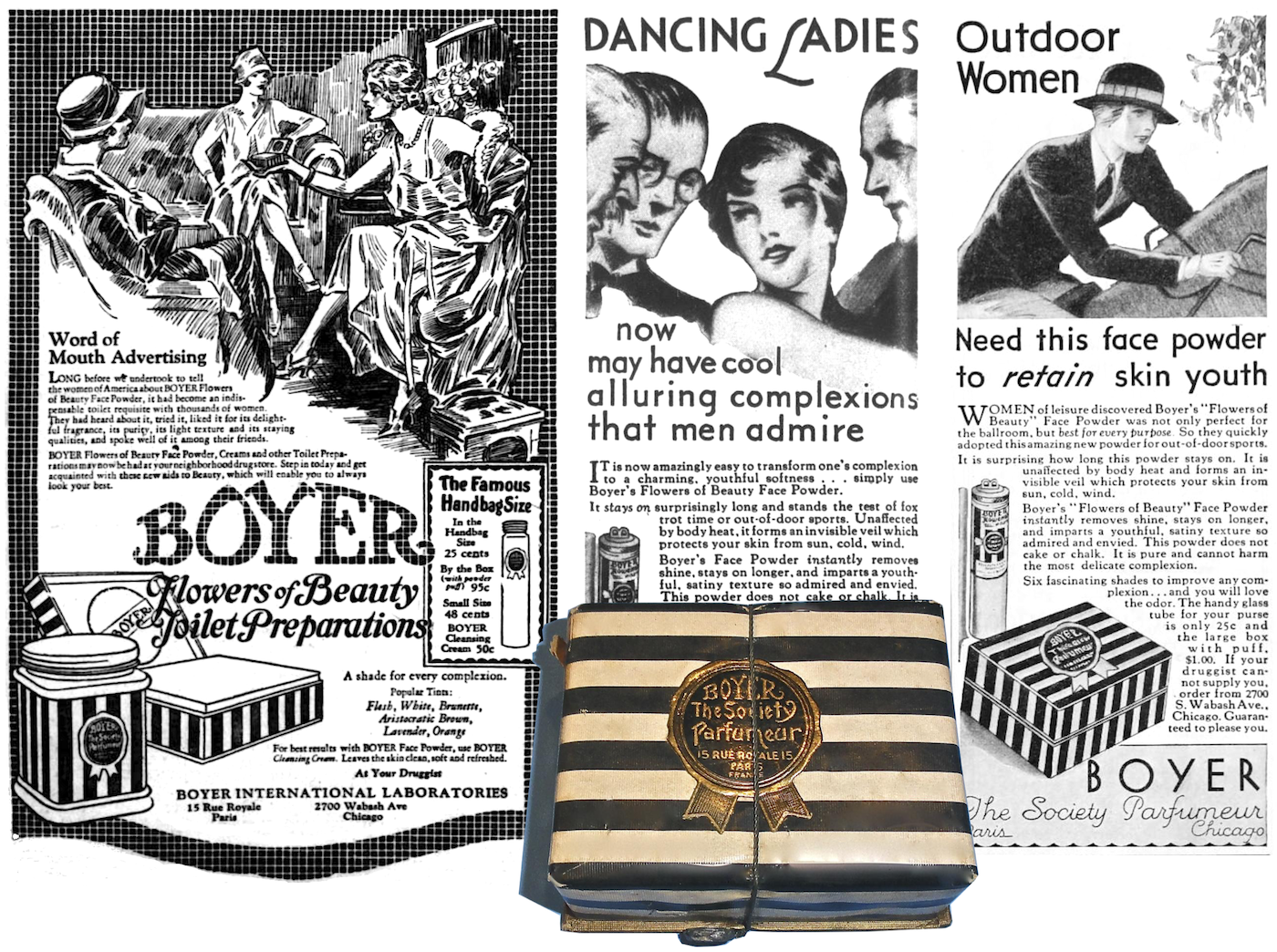

Flowers of Beauty, as seen in the “handbag size” container in our museum collection, was originally packaged with stylish black-and-white striped labels—not unlike those popular dresses worn on the Rue Royale by the women who “knew the secret” of great skin. And while the product was created to appeal to the excess-oriented sensibilities of the 1920s, it remained popular into the early 1930s, as a sort of applicable reminder of fancier times.

“Boyer’s ‘Flowers of Beauty’ Face Powder instantly removes shine, stays on longer, and imparts a youthful, satiny texture so admired and envied,” read a 1931 in Photoplay magazine. “This powder does not cake or chalk. It is pure and cannot harm the most delicate complexion.”

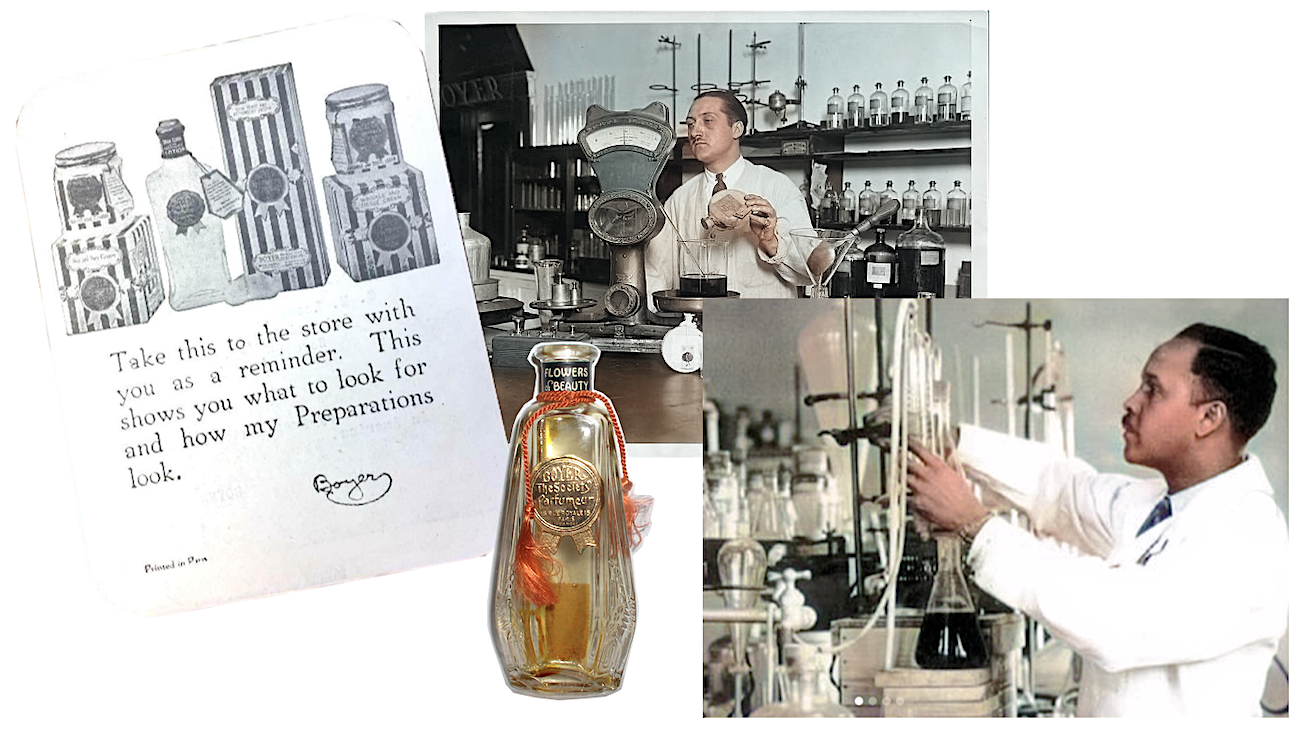

Those claims may or may not have been 100% legitimate, but no one could accuse Boyer of skimping entirely on the science. His own degree in chemistry and studious absorption of perfumery manuals was bolstered by a strong team of researchers in his labs, both in France and in Chicago. In the early days of the business, that roster included a young African-American, Lloyd Augustus Hall, as its chief chemist. Hall would go on to an important career as a major innovator in the science of food preservation.

[The Boyer Chemical Laboratory did, indeed, include a laboratory, led during the 1930s by Louis Clement (top center) and in the early 1920s by the pioneering African-American chemist Lloyd Hall (right)]

In 1933, the Boyer International Laboratories, also known as Boyer Industries, had its own booth at Chicago’s World’s Fair in the General Exhibits Building, where Alden also displayed his private collection of “early rouge jars,” which he deemed to likely be “the finest in the world.”

For all the emphasis on the cosmetics wing of the Boyer business, however, his Chicago enterprise had never actually abandoned its original, less elegant manufacturing lines; the “grunt” utilitarian chemical products that seemed more befitting of the company’s seven-story, ex-sausage factory at 2700 South Wabash.

A Boyer Chemical Laboratory Co. invoice from 1932 reveals the extent of this line, including toilet bowl cleaner, “Laundry Wonder” washing compound, “Kill ‘Em All” household insecticides, soldering pastes and salts, pipe joint compound, metal and furniture polishes, “farmer’s necessities” (including “hog oil”), and a broad array of automotive accessories—including valve grinding compounds, radiator cement, glossy auto paint, waxes, and the “Get Those Canary Birds” brand of anti-squeak penetrating oil. The two best known commercial lines under the Boyer banner, though, were probably its “3B” (“Boyer’s Best Brand”) and “Red Crown” trademarks, used on oil compounds and household cleaners, alike.

A Boyer Chemical Laboratory Co. invoice from 1932 reveals the extent of this line, including toilet bowl cleaner, “Laundry Wonder” washing compound, “Kill ‘Em All” household insecticides, soldering pastes and salts, pipe joint compound, metal and furniture polishes, “farmer’s necessities” (including “hog oil”), and a broad array of automotive accessories—including valve grinding compounds, radiator cement, glossy auto paint, waxes, and the “Get Those Canary Birds” brand of anti-squeak penetrating oil. The two best known commercial lines under the Boyer banner, though, were probably its “3B” (“Boyer’s Best Brand”) and “Red Crown” trademarks, used on oil compounds and household cleaners, alike.

Together, this hefty catalog of chemical goods represented the money-making foundation of a business that probably couldn’t otherwise have sustained its president’s globe-trotting, flower-picking, antique-hoarding pursuits.

III. The Museum Inside a Factory

“Wearing a French beret and driving an imposing Hispano-Suiza car, Alden Scott Boyer, Cresco, Iowa, boy who is now ‘Boyer, Society Parfumeur’ of Paris, France, was in Cedar Rapids Saturday and Sunday, wishing he had time to hunt museum pieces. Attics of old Iowa farm houses, he maintained, are filled with cobwebby treasures. . . . Mr. Boyer, who talks with his hands in the way of the French, despite an annual six months residence in Chicago, found fortune in the beauty of women’s faces.” —Cedar Rapids Gazette, 1934

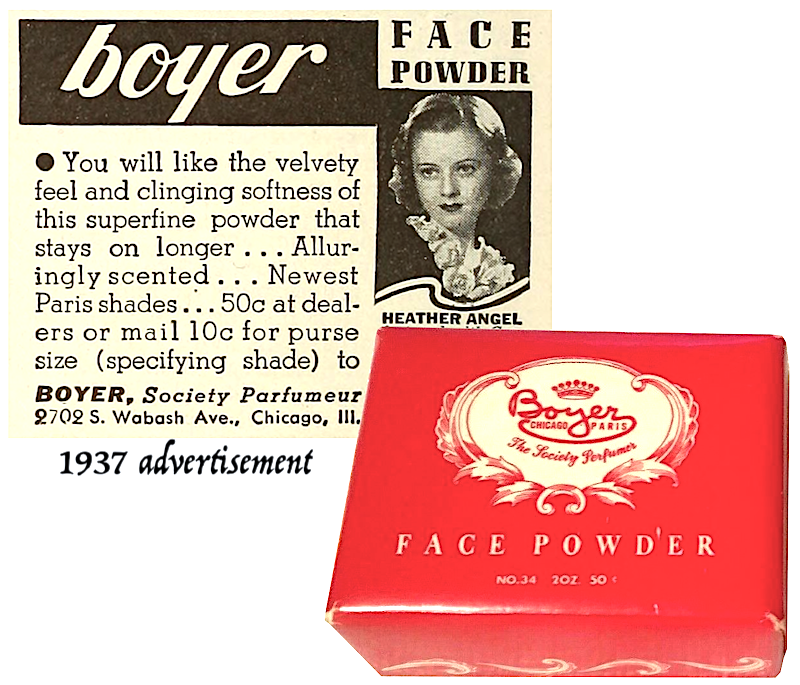

Boyer maintained his “Society Parfumeur” alter-ego (sometimes Americanized to “Society Perfumer”) into the late 1930s, advertising in cheap cinema magazines like Hollywood, Movie Classic, and Romantic. The accompanying Paris address at 15 Rue Royale would disappear from advertisements by 1935, however, and was almost certainly abandoned entirely by the time of the Nazi invasion of the city.

Boyer maintained his “Society Parfumeur” alter-ego (sometimes Americanized to “Society Perfumer”) into the late 1930s, advertising in cheap cinema magazines like Hollywood, Movie Classic, and Romantic. The accompanying Paris address at 15 Rue Royale would disappear from advertisements by 1935, however, and was almost certainly abandoned entirely by the time of the Nazi invasion of the city.

It’s a safe assumption that the Great Depression was not friendly to the ledgers of the Boyer offices in Chicago, either. Like many cosmetics firms, the company’s use of bold, anti-aging claims in its advertising had gone broadly overlooked for a while, but was now coming under closer scrutiny from the Federal Trade Commission, resulting in some cease-and-desist orders in the mid ’30s. Boyer could no longer claim that its face powder was “perspiration-proof” or that it wouldn’t clog the pores.

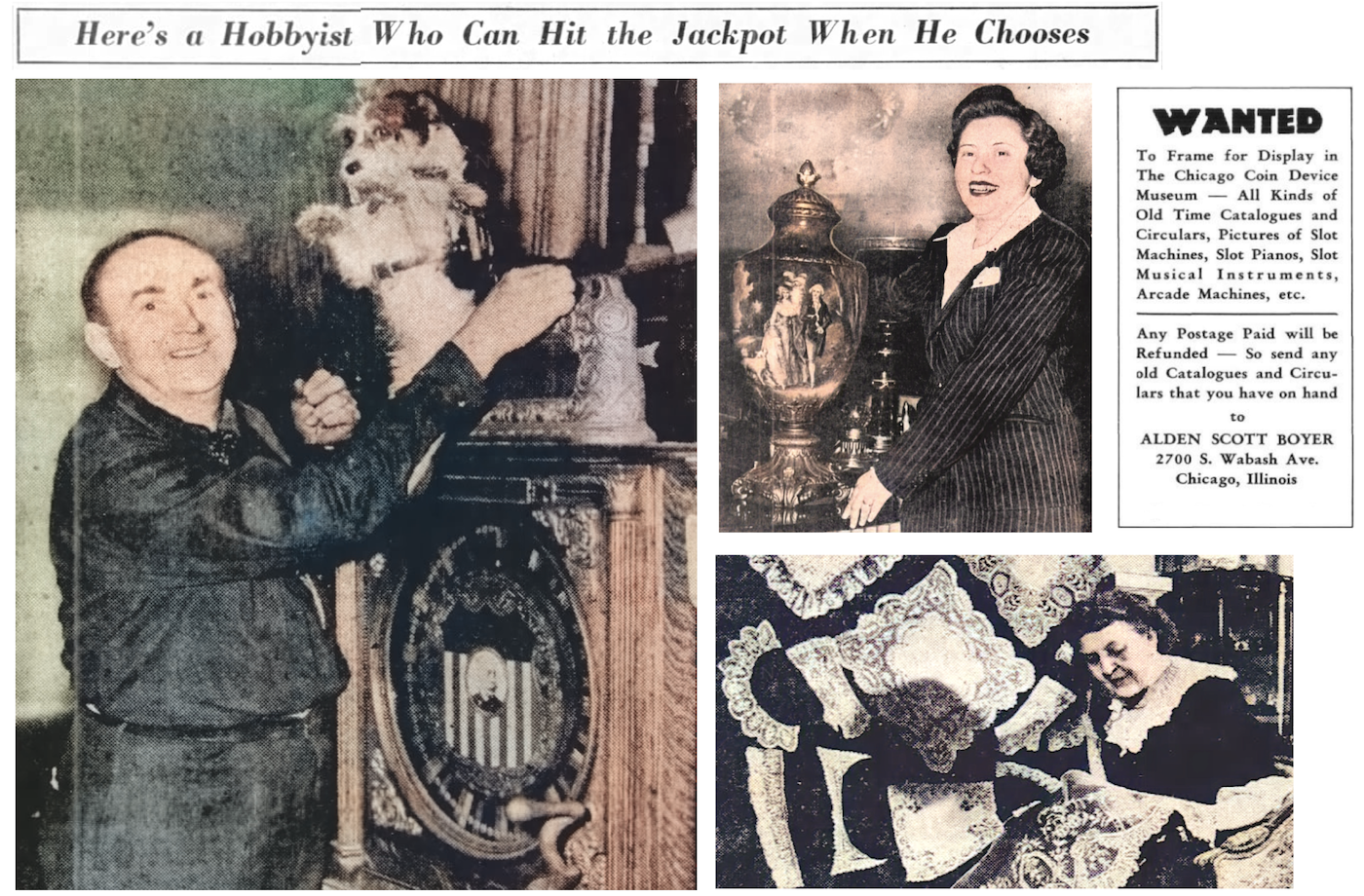

If he had to show restraint in his marketing, though, Alden certainly didn’t need to do the same when it came to his personal expenses, which would soon include a fancy new home at 845 Drexel Square in Hyde Park; no less than seven pet dogs (Garbo, Foxy, Whiskers, Zipper, Coconuts, Peanuts, and Doughnuts were among the pooches’ names); and, of course, many more loads of peculiar antiques.

Starting in 1938, Boyer developed a new fascination for coin-operated devices—a type of collectable that’s quite popular these days, but was in its absolute infancy when Alden decided to anoint himself the singular curator of the genre. Since most folks considered these old machines as cumbersome as they were obsolete, Boyer happily offered to pay the freight for anyone and everyone to send him their “old-time slot-machines, Regina musical boxes, Mills Violanos, and slot pianos,” among other novelties. “I get much pleasure and adventure in the study of the mechanical principles used in these excessively complicated and thoroughly ingenious inventions,” he explained. “They were devised in the old days by men whose names are relatively unknown and whose glory is unsung. I am preserving them for future generations to see.”

[Left: Alden Boyer shows off one of his antique slot machines (a 1898 “Admiral Dewey”) with the help of one of his dogs, Whiskers, 1946. Top Right: Doris White, a Boyer employee, admires a French vase that sits on the boss’s desk, 1946. Bottom Right: Boyer’s wife, Marie Boyer, displays her own considerable collection of antique lace, 1944.]

Within a year or two he’d managed to create the Boyer Coin-Op Museum inside the company offices at 2700 S. Wabash; which would later grow into the larger, ever-unvisitable Museum of American Curiosities.

“Boyer’s employees are accustomed to stumbling over ancient French treasure chests or bumping into an old English lamp post,” the Chicago Tribune reported on a visit to the Boyer Building in 1944. “Strange sounds coming from one of the downstairs rooms don’t perturb them one bit. ‘The fancy player piano?’ one will venture. ‘No, it’s the 1893 music box,’ another will declare. The largest part of Mr. Boyer’s collection is strewn about the laboratory which occupies a seven story building at 2700 Wabash ave.”

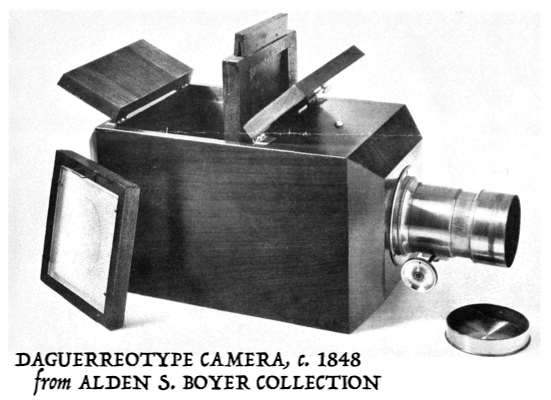

Even if he didn’t have the most considerate methods of storage, Boyer foresaw the value (financially and culturally) of objects that many of his contemporaries considered disposable, and it has made him something of a folk hero in several camps of the collecting world to this day. Maybe above all else, his remarkable library of early photography and photographic equipment—another obsession that started in the late 1930s—remains one of the most important such collections in that field; nearly all of it having been donated to the George Eastman House shortly before Boyer’s death.

Boyer’s Chicago plant continued to operate through World War II, producing insecticides and other chemical products for U.S. Military use. This arrangement didn’t last for long, however, and perhaps as no coincidence, by 1944, the federal government was once again charging Boyer with illegal advertising practices. According to a court filing, Boyer’s “Kill ‘Em All” fly killer liquid was, in the government’s view, “not lethal to the ordinary house fly.” Some of the company’s other 3B products were also mislabeled, either failing to contain listed ingredients or weighing less than their listed weight.

Boyer’s Chicago plant continued to operate through World War II, producing insecticides and other chemical products for U.S. Military use. This arrangement didn’t last for long, however, and perhaps as no coincidence, by 1944, the federal government was once again charging Boyer with illegal advertising practices. According to a court filing, Boyer’s “Kill ‘Em All” fly killer liquid was, in the government’s view, “not lethal to the ordinary house fly.” Some of the company’s other 3B products were also mislabeled, either failing to contain listed ingredients or weighing less than their listed weight.

Maybe Alden Scott Boyer was cutting corners with his business, or maybe he was just too preoccupied with his hobbies. In either case, he soon realized that he needed to get his proverbial house in order.

IV. De-Cluttering

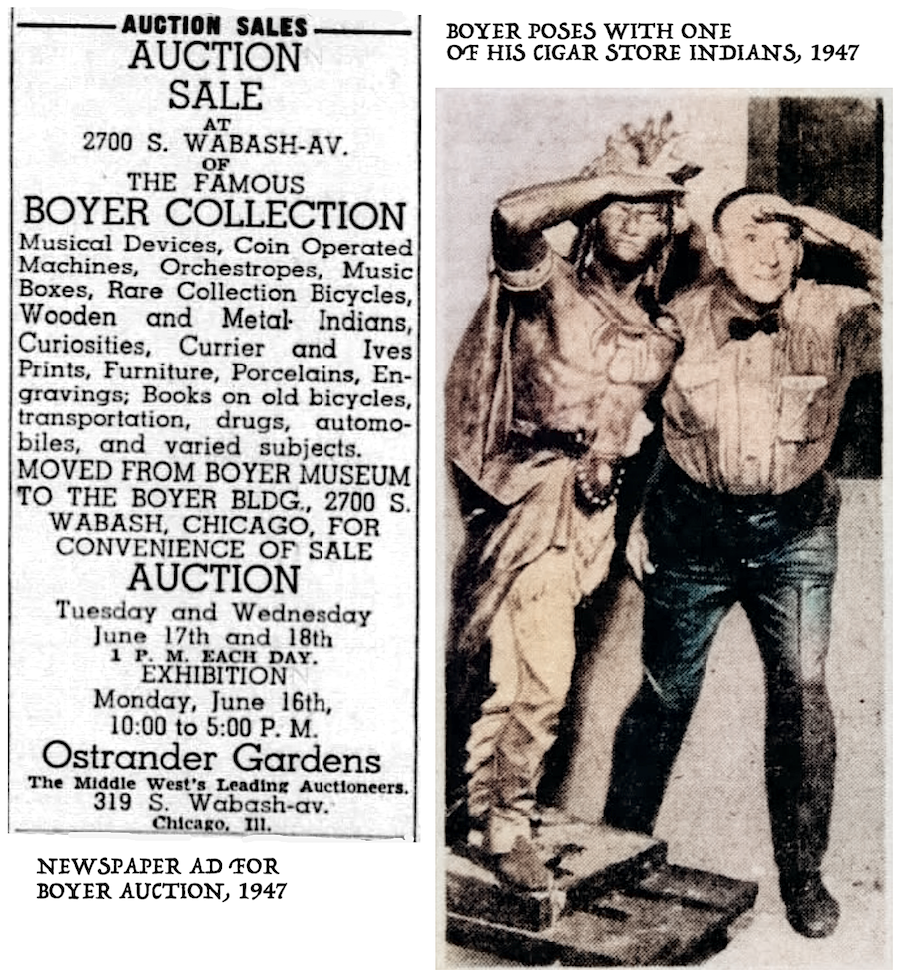

In 1947, a 60 year-old Alden Scott Boyer made headlines around the country as he began the process of unloading some of the bizarre collections he’d spent half his life acquiring. In one example, he sold off all of his man-sized tobacco store Indians—plus some prized jukeboxes and slot machines—during a two-day auction in Chicago. A newspaper report described Boyer as “a large, ruddy-faced man” who spent the auction “perched on a merry-go-round horse left over from the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, watching his ‘toys’ going to the highest bidder.”

“It took me 25 years to collect them,” Boyer said of the wooden Indian figures. “Now I’m letting them go all at once, and for a song. Just don’t have room for them all. . . . Well, I guess I’ve had my fun with ‘em anyway.”

“It took me 25 years to collect them,” Boyer said of the wooden Indian figures. “Now I’m letting them go all at once, and for a song. Just don’t have room for them all. . . . Well, I guess I’ve had my fun with ‘em anyway.”

While later articles would claim that Boyer moved his consolidated museum of curiosities into an old bank building on Michigan Avenue, we could only find evidence of him discussing his plan to do so; none to substantiate that he ever actually did. Every reporter who personally witnessed his collections seemed to do so inside one of his factory buildings, rather than a dedicated space. One such reporter, Maureen Carr of the Chicago Star, asked Boyer in 1947 when he’d finally open his museum to the public.

“Dunno,” Boyer answered.

Carr wrote cynically of this encounter, describing the strange sight of a wooden Indian staring out at the “priceless, preposterous clutter of civilization’s things” in the Boyer factory. “The stolid wooden face told me that this would never be a museum.”

While the media reported eagerly on Boyer’s antique auctions, they’d largely missed the fact that he’d also quietly sold his company’s slumping cosmetics division, known as Boyer International Laboratories, Inc., in 1947. Had they noticed, they would have taken even greater interest in the man to whom he sold the business.

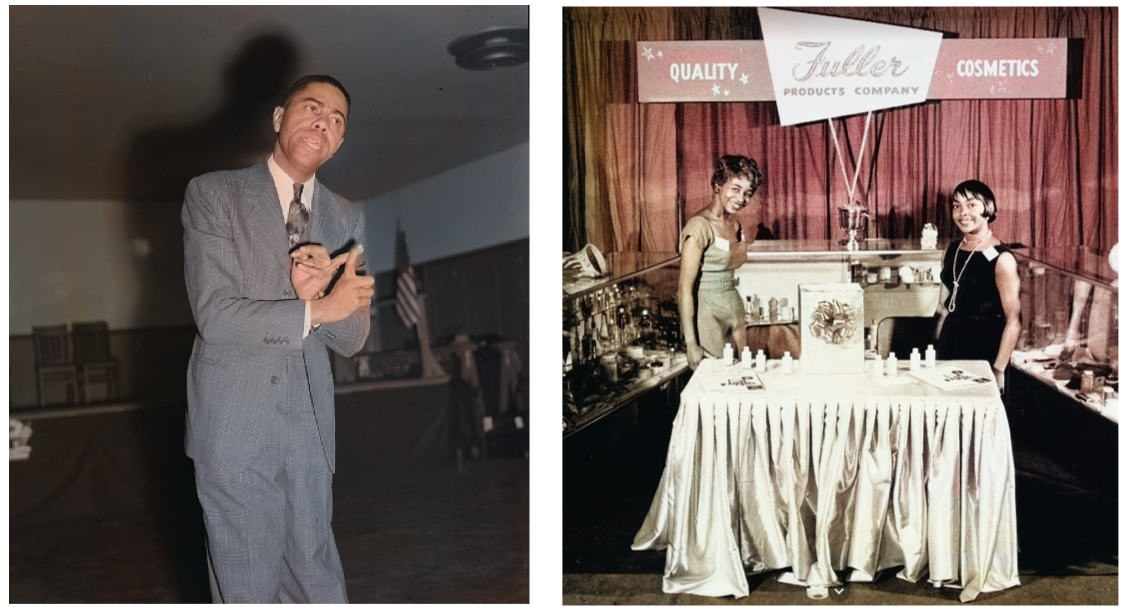

[Left: Samuel B. Fuller, owner of Chicago’s Fuller Products Co., pictured in 1942. Right: The booth of the Fuller Products Company at a convention, 1959]

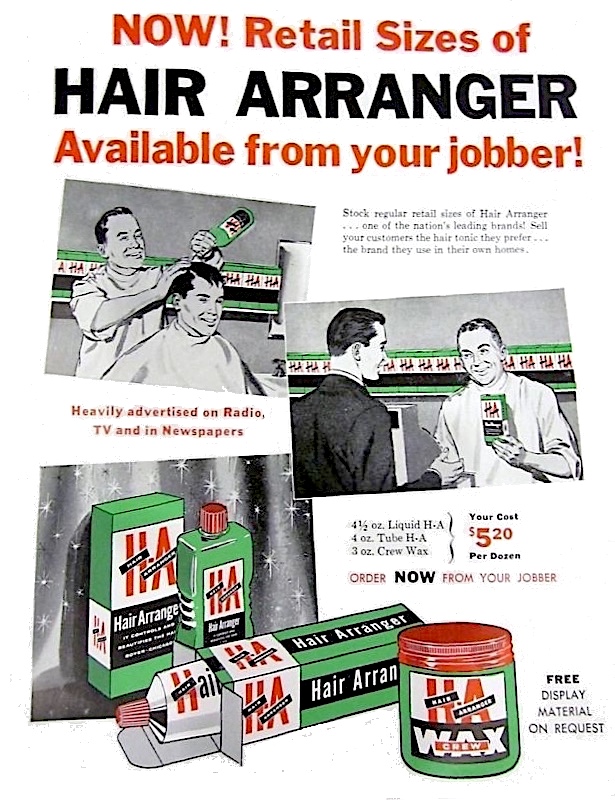

Samuel B. Fuller, president of the Chicago-based Fuller Products Company (not to be confused with the Fuller Brush Co.) and one of the most successful African-American entrepreneurs in America, had purchased the entire Boyer International business, complete with the factory at 2700 S. Wabash, the contracts of the employees therein, and the full line-up of caucasian-centric cosmetic products. By the late 1940s, that included the “Jeanne Nadal” line for women, the “Alden Scott” line for men, and a popular hair tonic called ‘H A Hair Arranger.”

As an open-minded man of the world, Alden Boyer was generally on the progressive side when it came to his public relations, whether it involved negotiating with labor unions or hiring minorities to important positions, as evidenced by his early working relationship with the aforementioned chief chemist Lloyd Hall.

As an open-minded man of the world, Alden Boyer was generally on the progressive side when it came to his public relations, whether it involved negotiating with labor unions or hiring minorities to important positions, as evidenced by his early working relationship with the aforementioned chief chemist Lloyd Hall.

With this in mind, it isn’t entirely shocking that Boyer recognized Samuel Fuller as a man fully capable of running his business successfully. It’s also not surprising, considering the politics of the time period, that the deal was kept quiet. Fuller had more to lose than anyone if his purchase was publicized. Boyer’s cosmetics, by now, had a particularly strong customer base in the American South, and as such, it was best for business if that audience was none the wiser about the skin color of the man now in charge of their favorite face powders and hair tonics.

V. The Fuller Era & Beyond

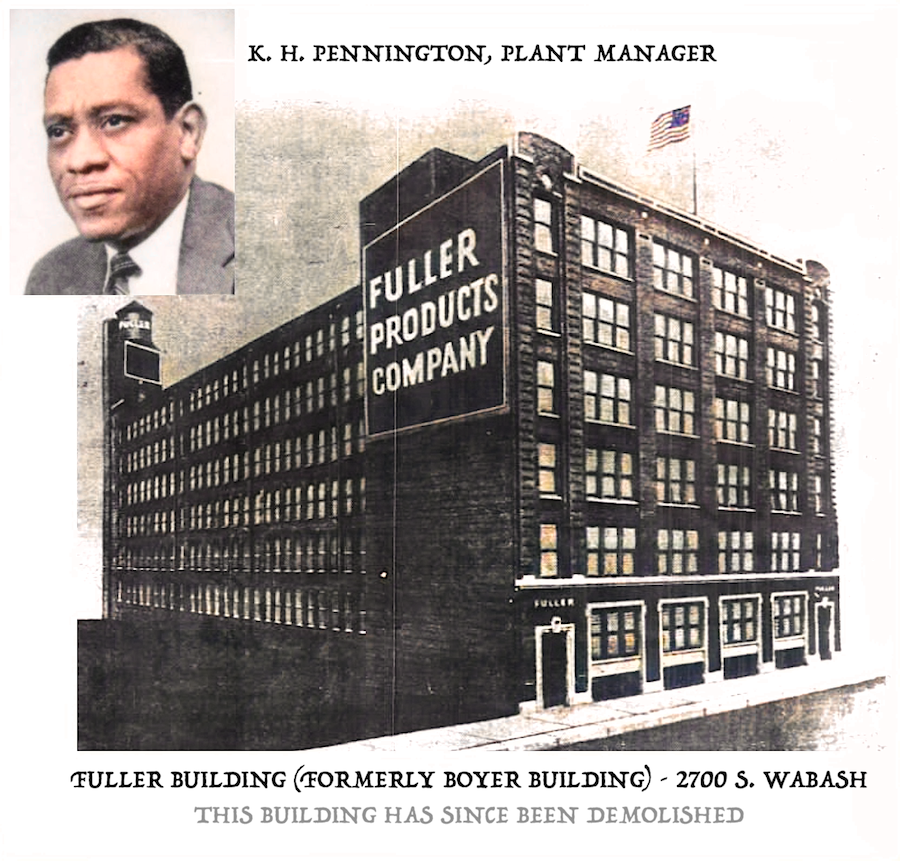

Samuel B. Fuller took over the reins of Boyer International and kept the factory running at 2700 S. Wabash, re-christening the “Boyer Building” as the “Fuller Building” and installing one of his top men, K. H. Pennington, as the new plant manager (another employee, a low level chemist named George Johnson, would go on to form the hugely successful Johnson Products Company). Pennington helped bring the factory into the modern age with more automatic machining, and the pay-off was swift. According to a later account in Black Enterprise magazine, Fuller’s business “soared with the acquisition of Boyer. Sales volume peaked at $10 million. By 1958, 60 percent of the Fuller business was through the Boyer line throughout the South.”

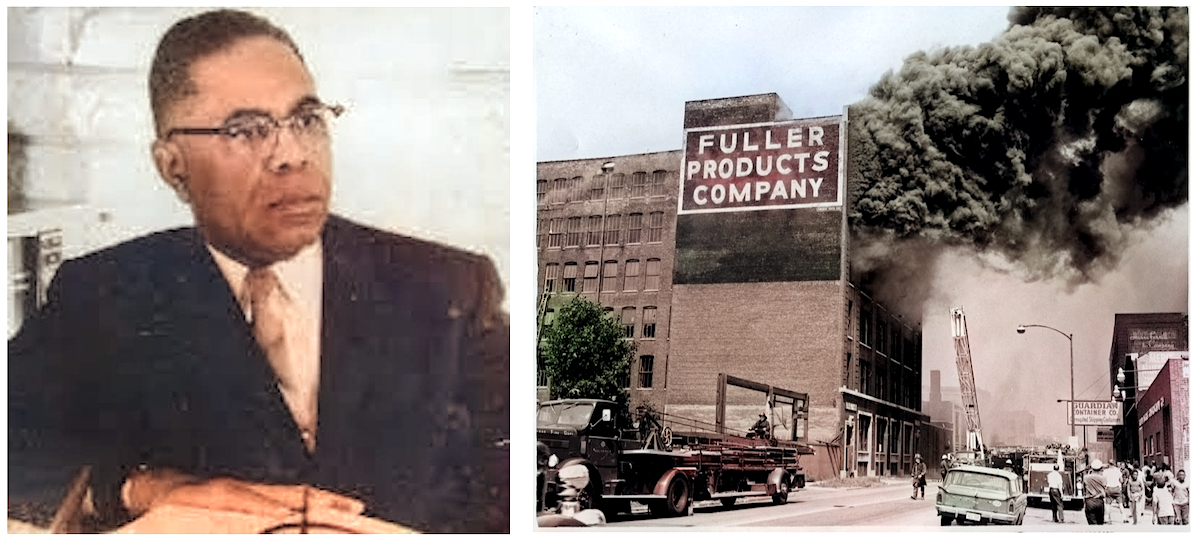

Unfortunately, the tide turned dramatically in the 1960s, as growing tensions during the Civil Rights Movement led to aggressive boycotting of certain businesses along racial lines. This primarily involved African-Americans picketing the racist policies of white-owned businesses, but in Samuel B. Fuller’s case, a group of white Southerners had discovered his ownership of Boyer International, and opted for their own, albeit wholly baseless boycott of its products.

Unfortunately, the tide turned dramatically in the 1960s, as growing tensions during the Civil Rights Movement led to aggressive boycotting of certain businesses along racial lines. This primarily involved African-Americans picketing the racist policies of white-owned businesses, but in Samuel B. Fuller’s case, a group of white Southerners had discovered his ownership of Boyer International, and opted for their own, albeit wholly baseless boycott of its products.

“The boycott spread across the white South rapidly and effectively,” Black Enterprise reported in a 1975 retrospective. “Sales on Jeanne Nadal and Hair Arranger plummeted to zero. In most Southern stores, the products were removed from the shelves.”

Fuller tried to sell off the Boyer line, but when a deal fell through, he ended up in an even deeper financial hole, and his original company, Fuller Products, was soon in bankruptcy . . . all as a direct result of simple bigotry.

[Left: Samuel B. Fuller. Right: A major fire breaks out at the Boyer / Fuller Building, 2700 S. Wabash, in October of 1965. Aside from this photo, actual newspaper reports about the cause or aftermath of the fire have alluded us, but the blaze at least metaphorically signaled the state of the Fuller Products Company at the time, as boycotts by Southern customers tanked its luxury cosmetics brand sales]

It was a sad downfall for the Boyer cosmetics line, as well, although its creator didn’t live to see it.

Alden Scott Boyer died from a heart attack in Chicago in 1953, aged 66. At the time, he was still the listed owner of the Boyer Chemical Laboratory Company—the industrial product wing of his business, which had moved down the street to a building at 2232 S. Wabash Avenue following the Fuller sale. Boyer’s wife Marie had died three years before him, and though he’d remarried (a woman named Elizabeth Johnson), he had no children and no clear heirs to take over the company.

Instead, a man named George A. Radford ascended to the presidency of the business, moving its operations north to Evanston in 1957, at 1609-11 Church Street. By the 1970s, Boyer Chemical had morphed into the Boyer Corporation—still specializing mainly in cleaning products and drain openers—and it would continue on as such, moving to La Grange, IL, in the 1990s, and more recently, Westmont, IL.

The old cosmetic business, Boyer International Laboratories, also had a revival or two after the Fuller era, operating for a time in the 1980s at 50 E. 26th Street.

The old cosmetic business, Boyer International Laboratories, also had a revival or two after the Fuller era, operating for a time in the 1980s at 50 E. 26th Street.

As of 2023, only the Boyer Corp. remains a functioning entity, producing some of the same brands as it did under Alden Scott’s watch (including “Red Crown” lye) and selling them primarily through Amazon. Unfortunately, under its current ownership, Boyer Corp. has lost the plot a bit on its own origin story. The homepage of the corporate website (as of 2023) lists “Charles Boyer” as the founder of the business. Sigh. Charles Boyer was a French-American film actor, but he could never claim to have been the Society Parfumeur.

This isn’t the only posthumous insult to the legacy of Alden Scott Boyer. The Wikipedia page of Cresco, Iowa, that tiny town in which he grew up, doesn’t even list Boyer among its “notable people.”

He spent a life preserving American curiosities, but in some ways, his own curious contributions have been overlooked, not unlike those nameless men who designed the coin-op machines he so admired. Nonetheless, thanks to the wealth of essays, letters, and donated materials he left behind, we at least can get a sense of who Boyer was as a person, not just as a fellow who once owned a chemical business.

“In general, I am afraid of French coffee,” he once wrote, part of a random anecdote that seems to oddly capture his spirit, “especially in cities outside of Paris. The French, as a rule, do not know how to make good coffee, After my dinner I said to the head waiter, ‘Is your coffee truly good here or is it that tincture of iodine kind?’ He said, ‘Monsieur, we are famous for our coffee. We have bought our coffee from one firm in Marseilles for over 130 years. We served this same coffee to Napoleon when he was a guest here, and COFFEE THAT WAS GOOD ENOUGH FOR NAPOLEON OUGHT TO BE GOOD ENOUGH FOR YOU.’ I said, ‘Okay, you are right.’ The coffee was served and it truly was good. I liked that antique coffee—yes I did.”

“In general, I am afraid of French coffee,” he once wrote, part of a random anecdote that seems to oddly capture his spirit, “especially in cities outside of Paris. The French, as a rule, do not know how to make good coffee, After my dinner I said to the head waiter, ‘Is your coffee truly good here or is it that tincture of iodine kind?’ He said, ‘Monsieur, we are famous for our coffee. We have bought our coffee from one firm in Marseilles for over 130 years. We served this same coffee to Napoleon when he was a guest here, and COFFEE THAT WAS GOOD ENOUGH FOR NAPOLEON OUGHT TO BE GOOD ENOUGH FOR YOU.’ I said, ‘Okay, you are right.’ The coffee was served and it truly was good. I liked that antique coffee—yes I did.”

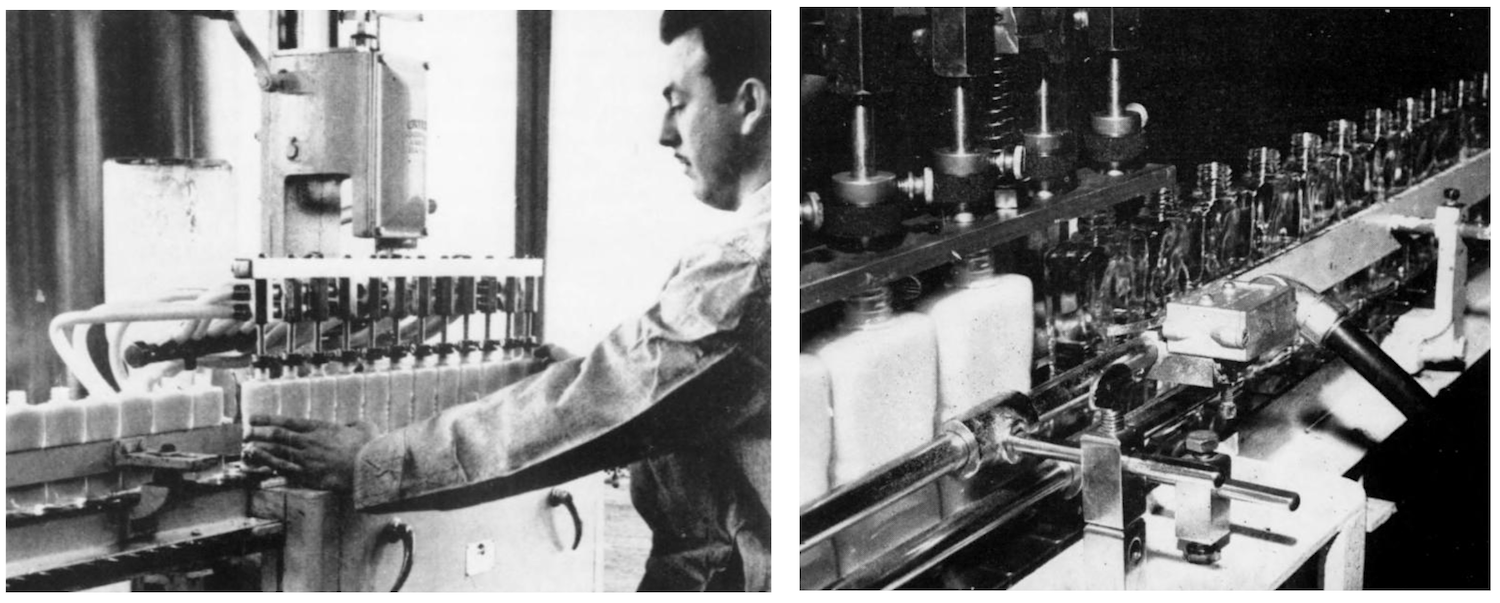

[Automatic bottling process inside the Boyer International / Fuller Products plant at 2700 S. Wabash, 1957]

Sources:

BoyerCorporation.com

“The New General Secretary: Alden S. Boyer” – The Numismatist, October 1921

Americans in France: A Directory, 1926

“Another Letter from Paris” – Nashua Reporter (Iowa), Aug 4, 1926

“Former Iowa Boy Now Heads an International Business in Perfumes and Cosmetics” – Cedar Rapids Gazette, May 20, 1934

“A Few Thoughts While Collecting Antiques,” by Alden Scott Boyer, Hobbies magazine, June 1935

“Indians Dance to ’90 Tunes in Hobby House” – Chicago Tribune, June 18, 1944

“Boyer Charged With Misleading Ad Copy” – Advertising Age, Sept 18, 1944

“Spiders’ Webs are Models for Delicate Laces” – Chicago Tribune, May 26, 1946

“A Collector’s Collection” – Chicago Star, April 19, 1947

“Tribe of Wooden Indians Sold” – Baraboo News-Republic (Wisconsin), June 18, 1947

“Alden S. Boyer, Perfume Firm Executive, Dies” – Chicago Tribune, June 17, 1953

“The Boyer Collection” – IMAGE Journal of Photography of the George Eastman House, October 1953

“Semi-automatic Bottle Filling on a Moving Chain” – Package Engineering, June 1957

“Mechanization of Semi-automatic Bottle Filling” – Package Engineering, August 1958

“S.B. Fuller: A Man and His Products” – Black Enterprise, August 1975

“Literature Discovery from America’s First Coin-Op Museum” – RickCrandall.net

“Lloyd Augustus Hall” – Book of Black Heroes, 2008

“Boyer the Society Parfumeur” – Journal of the France & Colonies Philatelic Society, March 2010

“Boyer Recalls Soap Making Chemicals After Child Suffers Burn Injuries” – Daily Hornet, March 19, 2020

“Boyer, Alden Scott” – CoinsWeekly.com