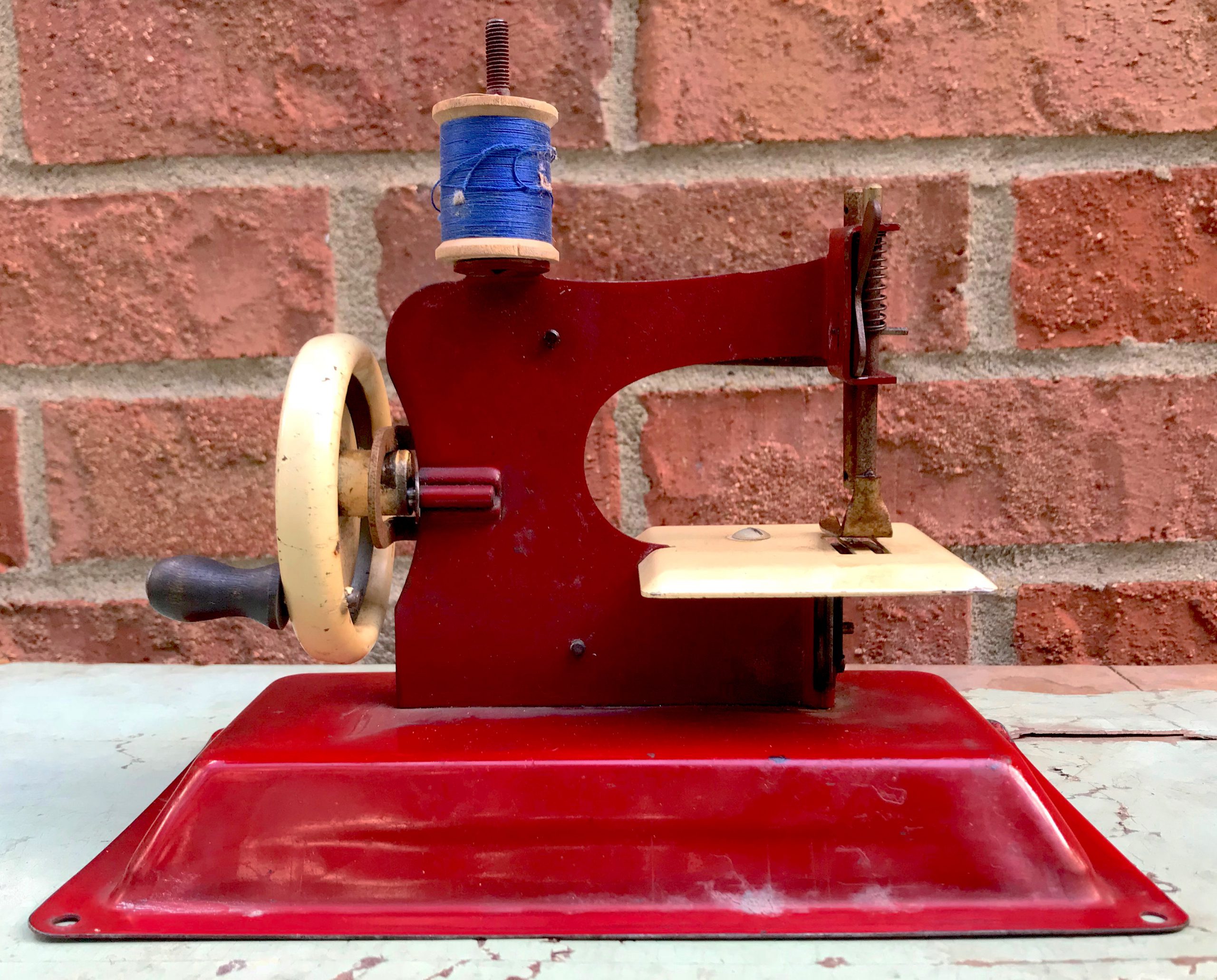

Museum Artifact: Gateway Junior Model NP-1 Sewing Machine, c. 1950

Made By: Gateway Engineering Company / Gateway Erectors, Inc., 233 W. Grand Ave., Chicago, IL [Humboldt Park]

“The Toy Sewing Machine that really sews!” —1948 advertisement for the Gateway Junior Model

Produced only for a short time from the late 1940s into the 1950s, the Gateway line of toy sewing machines represents a case study in a business making the most out of its extraneous materials. The Gateway Engineering Co., as the name would suggest, was not your traditional toy producer. They were, instead, in the “real” steel game, focusing most of their resources on major construction projects around the Midwest. The seemingly random foray into kid stuffs didn’t come until after the rationing of World War II had concluded, and a newfound overabundance of sheet metal likely lent itself to unorthodox ideas for supplementary income.

Produced only for a short time from the late 1940s into the 1950s, the Gateway line of toy sewing machines represents a case study in a business making the most out of its extraneous materials. The Gateway Engineering Co., as the name would suggest, was not your traditional toy producer. They were, instead, in the “real” steel game, focusing most of their resources on major construction projects around the Midwest. The seemingly random foray into kid stuffs didn’t come until after the rationing of World War II had concluded, and a newfound overabundance of sheet metal likely lent itself to unorthodox ideas for supplementary income.

“The original company manufactured supports for the reinforcing of steel on concrete decks,” says George Weiland, Jr., whose father George Sr. founded Gateway Engineering in 1933. “One of my uncles, Art Reiland, designed the toy sewing machine as well as roller skates, which we also made. The toys were a side line to fill in our building products.”

And that’s about the full extent of Mr. Weiland’s comments on the subject. He and his son, George Weiland III, still operate the Gateway Construction Company in Melrose Park—carrying on the same sort of contract work the family’s been doing for almost 90 years. Considering Gateway has had a hand in the construction of local landmarks like the Sears Tower and notorious overhauls like the modernization of Soldier Field, you can perhaps forgive the fact that a fleeting mid-century attempt at toy manufacturing hasn’t proven worthy of inclusion on their official corporate timeline.

[George N. Weiland Sr. founded the Gateway Engineering Co. (aka Gateway Erectors, Inc., Imoco-Gateway, and Gateway Construction Co.) in 1933. Photo: gatewayconstructionchicago.com]

[George N. Weiland Sr. founded the Gateway Engineering Co. (aka Gateway Erectors, Inc., Imoco-Gateway, and Gateway Construction Co.) in 1933. Photo: gatewayconstructionchicago.com]

In our estimation, though, the Gateway Junior sewing machine is an artifact worthy of some commemoration. It wasn’t innovative, exactly; there were dozens of different mini sewing machines out on the market for the “junior housekeeper” in the ’50s, including the the “Sew Master” by KAYanEE (New York), the “Little Lady” by Elm City Toy Products (Connecticut), “Stitch Mistress” by Doane Sales Corp. (California), the “Sew-O-Matic” by F. J. Strauss Co. (NY), and the Betsy Ross by the Gibralter MFG Co. of New Jersey. The king of all sewing machine names, Singer, also made a child’s model. So this was no easy market to waltz in and corner.

And yet, whether due to Art Reiland’s engineering skills (he had cut his teeth as an accordion repairman) or just the talents of a workforce experienced with higher-stakes construction jobs, the Gateway Junior, which sold for less than 3 bucks, seemed to meet with substantial approval. They’re designed to operate much like the full-scale models, and built to last, as well—not exactly par-for-the-course with your average easy-bake oven.

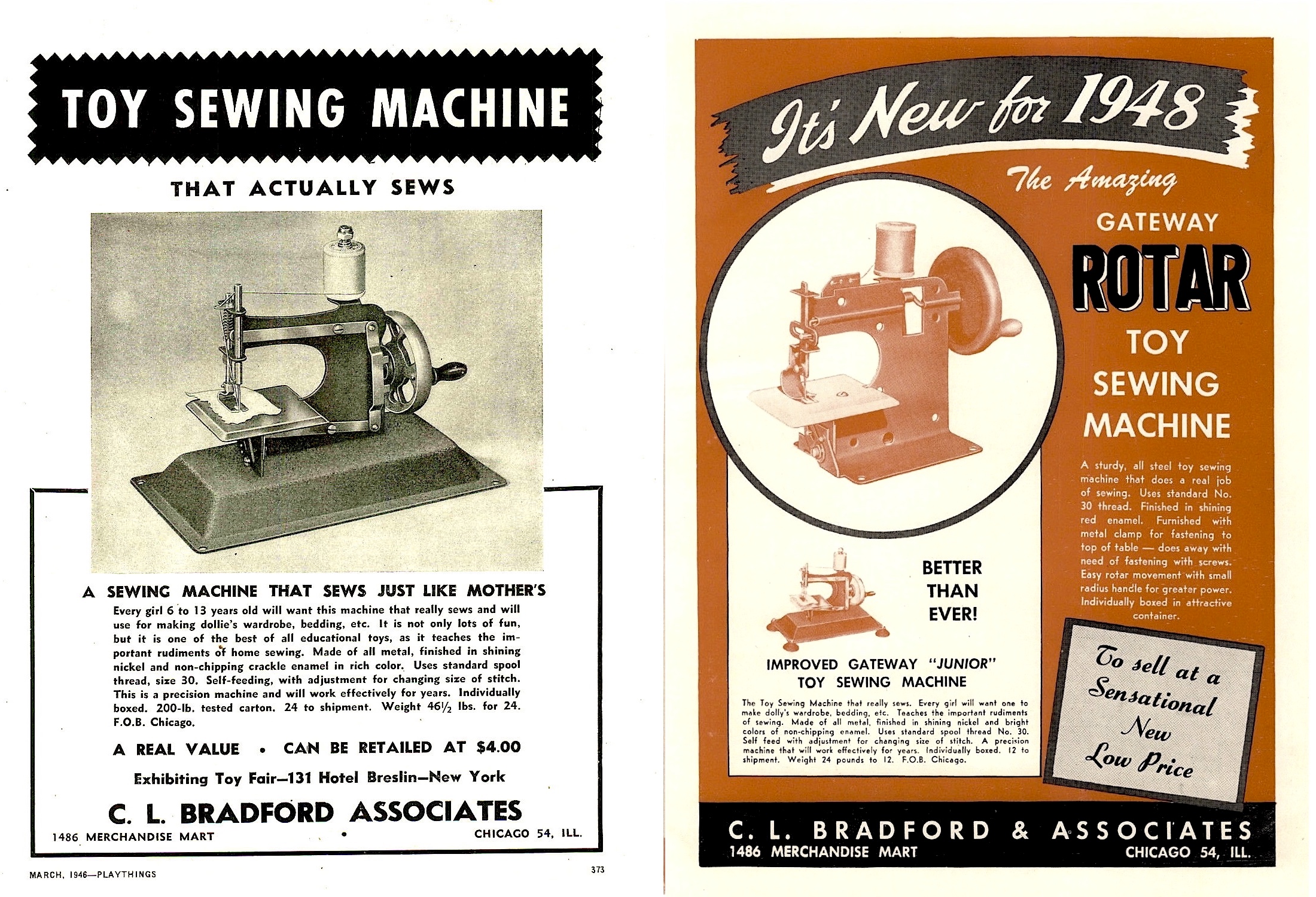

[1946 and 1948 advertisements for Gateway’s toy sewing machines, promoted by Chicago based distributor C. L. Bradford & Associates, 1486 Merchandise Mart]

[1946 and 1948 advertisements for Gateway’s toy sewing machines, promoted by Chicago based distributor C. L. Bradford & Associates, 1486 Merchandise Mart]

“A precision machine that will work effectively for years,” claimed a 1948 listing in a toy catalog.

“Every girl will want one to make dolly’s wardrobe, bedding, etc. Teaches the important rudiments of sewing. Made of all metal, finished in shining nickel and bright colors of non-chipping enamel to look just like Mother’s. Uses standard spool thread No. 30. Easy self-feeding to train small hands to stitch a neat seam.”

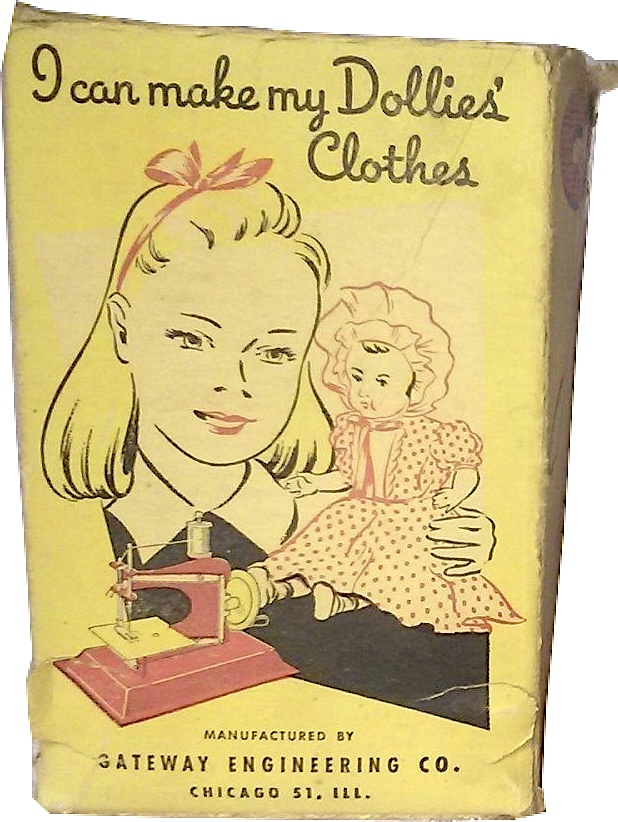

While we don’t have the original box for the Junior Model NP-1 in the museum collection, rare views of the vintage packaging reveal a disturbingly emotionless looking girl thinking to herself, “I can make my Dollie’s Clothes.”

While we don’t have the original box for the Junior Model NP-1 in the museum collection, rare views of the vintage packaging reveal a disturbingly emotionless looking girl thinking to herself, “I can make my Dollie’s Clothes.”

An additional tagline describes the lil’ red machine as “Another Precision Toy By Gateway Craftsmen.”

It’s worth noting that, outside of a supposed attempt at making roller skates (of which we’ve found no surviving evidence), Gateway’s precision toy line seemed pretty limited within the highly specific genre of mini sewing machines, so claiming the NP-1 was yet another offering from this toymaking juggernaut was probably a tad misleading. There was no denying Gateway’s legitimacy on the far grander stage of Chicago building construction, however.

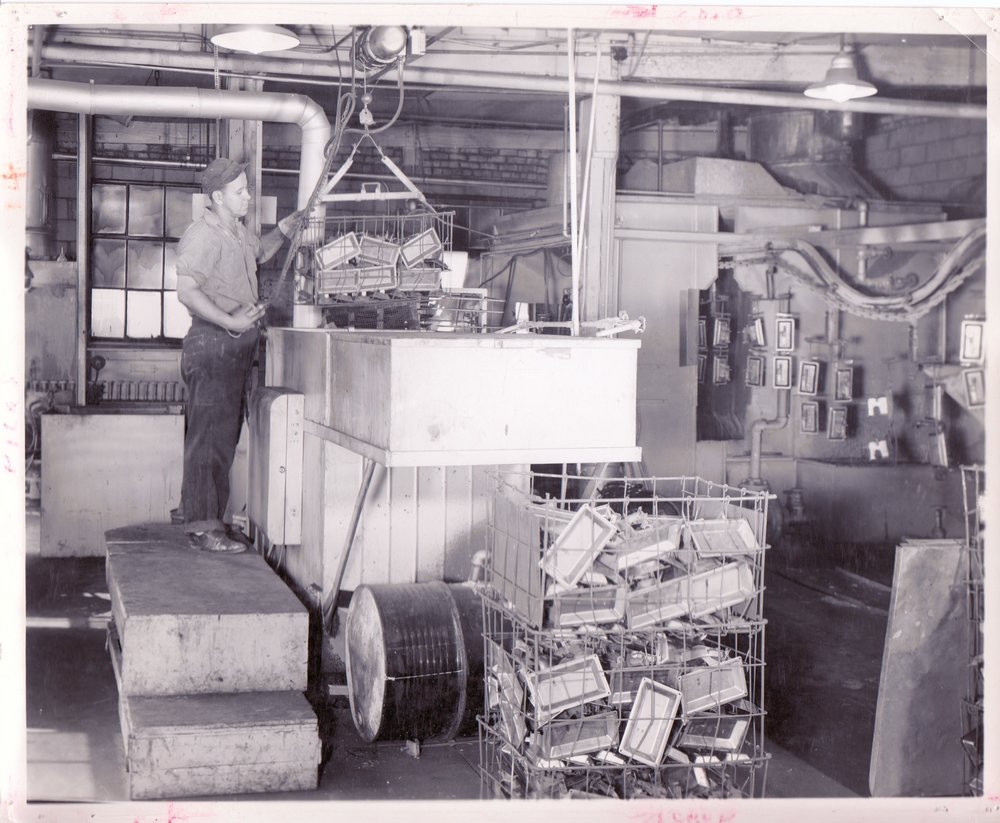

[A worker at the Gateway Engineering warehouse, 3233 W. Grand Ave., circa late 1940s. He appears to be sorting what might be a stack of steel base components for toy sewing machines.]

[A worker at the Gateway Engineering warehouse, 3233 W. Grand Ave., circa late 1940s. He appears to be sorting what might be a stack of steel base components for toy sewing machines.]

Along with George Weiland, Sr. (1908-1988), the Gateway Engineering Co. was led from its inception by Frank D. Reiland (1900-1973)—George’s cousin with the not-quite-identical but confusingly rhyming surname.*

*George Weiland’s widowed father Henry had a sister named Mary who married a fella named Nick Reiland, and Mary and Nick’s sons were thus named Frank and Art Reiland . . . if you’re keeping score at home.

*George Weiland’s widowed father Henry had a sister named Mary who married a fella named Nick Reiland, and Mary and Nick’s sons were thus named Frank and Art Reiland . . . if you’re keeping score at home.

Across 30 years, Frank Reiland had more than 35 patents to his credit—mostly in the field of concrete reinforcement—and it was his brother, the aforementioned Arthur F. Reiland (1906-1971), who apparently took the lead in launching the sewing machine side project.

Gateway had some government contracts during World War II, and the business seemed to grow quickly during that period as a result, moving from a plant at 4824 W. Kinzie in 1942 to another at 4617 W. Fulton Street in 1943. By 1946, the business had relocated to its more longstanding HQ at 3233 West Grand Avenue, where they’d soon begin producing their first toys alongside the usual tools of the building support trade.

[Former Gateway warehouse at 3233 West Grand Ave., as it looks today]

[Former Gateway warehouse at 3233 West Grand Ave., as it looks today]

As a minor coup of sorts, Gateway also inked a deal in 1948 with the Minnesota Mining & MFG Co. (3M) to be the exclusive Chicago contractor for its two new masonry finishes: 3M Vinyl and the plastics-based “Scotch Top”: a “revolutionary” spray-on coating that was supposed to replace plaster, paint and wallpaper in new home construction (it didn’t).

As Gateway’s construction business expanded further beyond Chicagoland, the toy making efforts were literally scrapped—possibly as a result of a warehouse fire in 1956. Shortly thereafter, Art Reiland relocated from the Chicago office to Milwaukee to head up the team there (he died in 1971), and by the start of the 1960s, the company’s construction division was reorganized as Gateway Erectors, Inc., with the old Gateway Engineering name eventually fading from use.

Gateway Erectors always hired skilled union labor and maintained a solid reputation for its work. Unfortunately, when you’re in the construction biz in a city eager to throw up new modern skyscrapers, a lot of your attention from the general public will come more as a result of the unfortunate risks of that dangerous trade.

A building contractor might not get a shoutout at a ribbon cutting ceremony, but tragedies always make headlines. Cases in point:

1954 – Three Gateway employees are injured when a scaffold falls during work on the Prudential Insurance Building, 130 E. Randolph St. This was the first major skyscraper built in Chicago in over 20 years, dating back before the Depression and WWII.

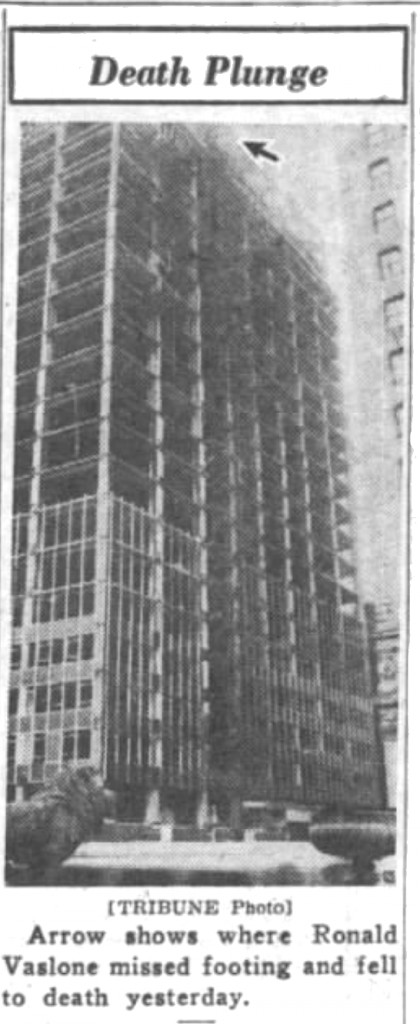

1957 – Gateway employee Ronald Vaslone falls 300 feet to his death while working on the Borg-Warner building at 200 S. Michigan Avenue. The Tribune not only misspelled Vaslone’s first name as “Roland” the next day, but also printed a photo of the building with an arrow pointing out the spot where he fell, under the words: “Death Plunge.”

1957 – Myron Conlee falls 112 feet to his death from a scaffold at the Commonwealth Edison Co. plant, 1111 W. Cermak, while building a boiler room wall.

1959 – Clifford Lewis, a structural steel foreman, is killed after being struck by a falling board at Lake Meadows apartments, 32nd and Rhodes Ave.

Lawsuits occasionally followed these incidents, such as a case in 1963 when Gateway was one of three companies forced to pay close to $500,000 to three workers who’d been pinned under a construction hoist while working on the Saints Faith, Hope & Charity Church in Winnetka.

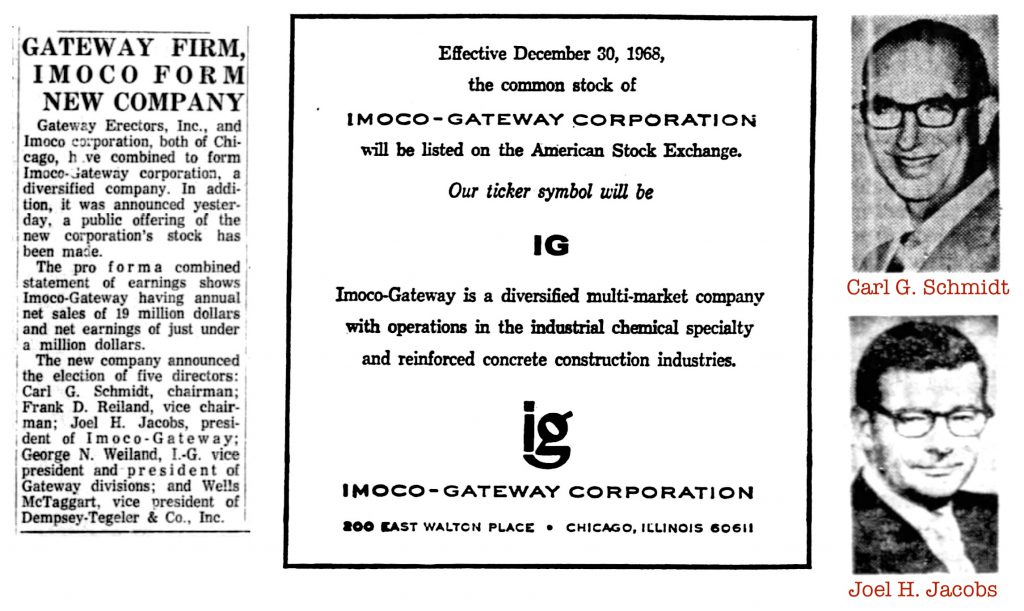

Despite all these challenges, growth was still the norm for Gateway throughout the 1960s. And when Frank Reiland announced his intention to retire in 1968, George Weiland tried to keep the forward momentum going by jumping into a new, ambitious partnership. That year, Gateway Erectors Inc. merged with Chicago’s Imoco Corp., a Volkswagen distributor that also had tentacles in the chemical and fabric industries.

The newly formed Imoco-Gateway Corporation, with former Imoco boss and Weiland/Reiland extended family member Carl G. Schmidt serving as chairman, was a publicly traded entity, and the early returns on the deal looked good for everyone, with profits steadily rising into 1969, highlighted by work on the Sears Tower project. As the 1970s unfolded, however, the trends moved rather severely in the opposite direction.

In 1978, after a decade together, the Imoco-Gateway era was over, as George Weiland Sr. and George Weiland Jr. bought back the original construction and manufacturing divisions and let the rest of the business dissolve. Imoco-Gateway had been hemorrhaging money, but the bigger issue seemed to be a collapsing board room, as company president Joel H. Jacobs had resigned outright “due to a disagreement over management policies and practices” related to construction activities, according to a news release at the time.

Cleaning house and starting anew, the Weilands launched the Gateway Construction Company and maintained both a construction and manufacturing division up into the 1990s, when the manufacturing business was sold off due to “competition from the non union south and manufacturing from overseas,” according to George Jr.

SOURCES:

“New Building Material is Tested Here” – Chicago Tribune, Dec 26, 1948

“Gateway Firm, Imoco Form New Company” – Chicago Tribune, Aug 30, 1968

“Imoco-Gateway Tells Shakeup” – Chicago Tribune, May 5, 1978

“3 Men Injured in Prudential Building Fall” – Chicago Tribune, June 26, 1954

“Death Plunge” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 21, 1957

“Steel Foreman Killed on Lake Meadows Job” – Chicago Tribune, July 14, 1959

“$478,000 Is Given 3 Workmen in Damage Suits” – Chicago Tribune, April 26, 1963

I have a Gateway Stitch Mistress, Model NP-49 SEWING MACHINE which is in great condition. It is in it’s original cardboard box which is also in great condition. Would you please let me know the value of this item.

Thank you very much!

I came across a box containing some sewing items one of them is a pair of 7″ pinking shears chrome plated..ball bearing action. They are yellow Canary still in plastic bag excellent shape in the box the came in which is in fair shape. I also have many odds and ins still in packs price on them like .35 and .69 all in excellent condition. Was wondering if you could help me

What is the value of the sewing machine now? 9/25/2022

I have a gateway junior sewing machine model #1. Wondering if it’s worth anything

I found one of the toy sewing machines does it have any value

I have the “Junior Model NP 1. Label in good condition, a few tiny scraps on paint. The right rear corner is bent up. Many happy hours sewing for my dolls! No-one to pass down to, what

would it be worth in 2021? Are there collectors that would be interested?

I recently obtained one of these amazing toys. I was wondering if it’s worth anything?

Do you know if the design of the toy sewing machine was sold to another company perhaps Genero or Gurlee?

I also have one and have not inquired about the value of such. My mother had it as a child and I have always thought it was cool. Do you have any idea what the value of such might be?

Thank you

I own one of the sewing machines. It was a Christmas gift many years ago. Oh the doll clothes it sewed. It is in pristine condition. Wondering if it is worth anything today. I would like to donate it to a museum if there is such a place that would want it. Wondering how many of these were produced back in the early ’50’s?