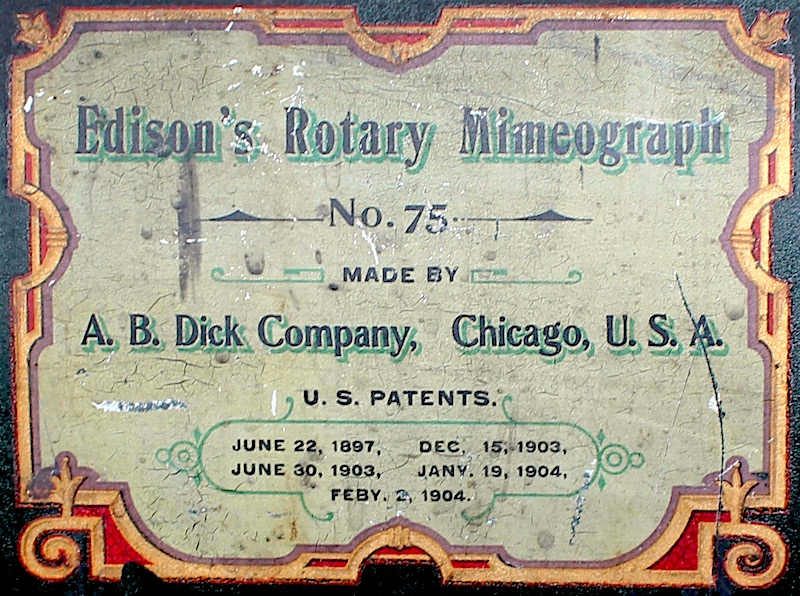

Museum Artifact: Edison Rotary Mimeograph No. 75, c. 1905

Made by: A.B. Dick Company, 163 / 738 W Jackson Blvd., Chicago, IL [West Loop]

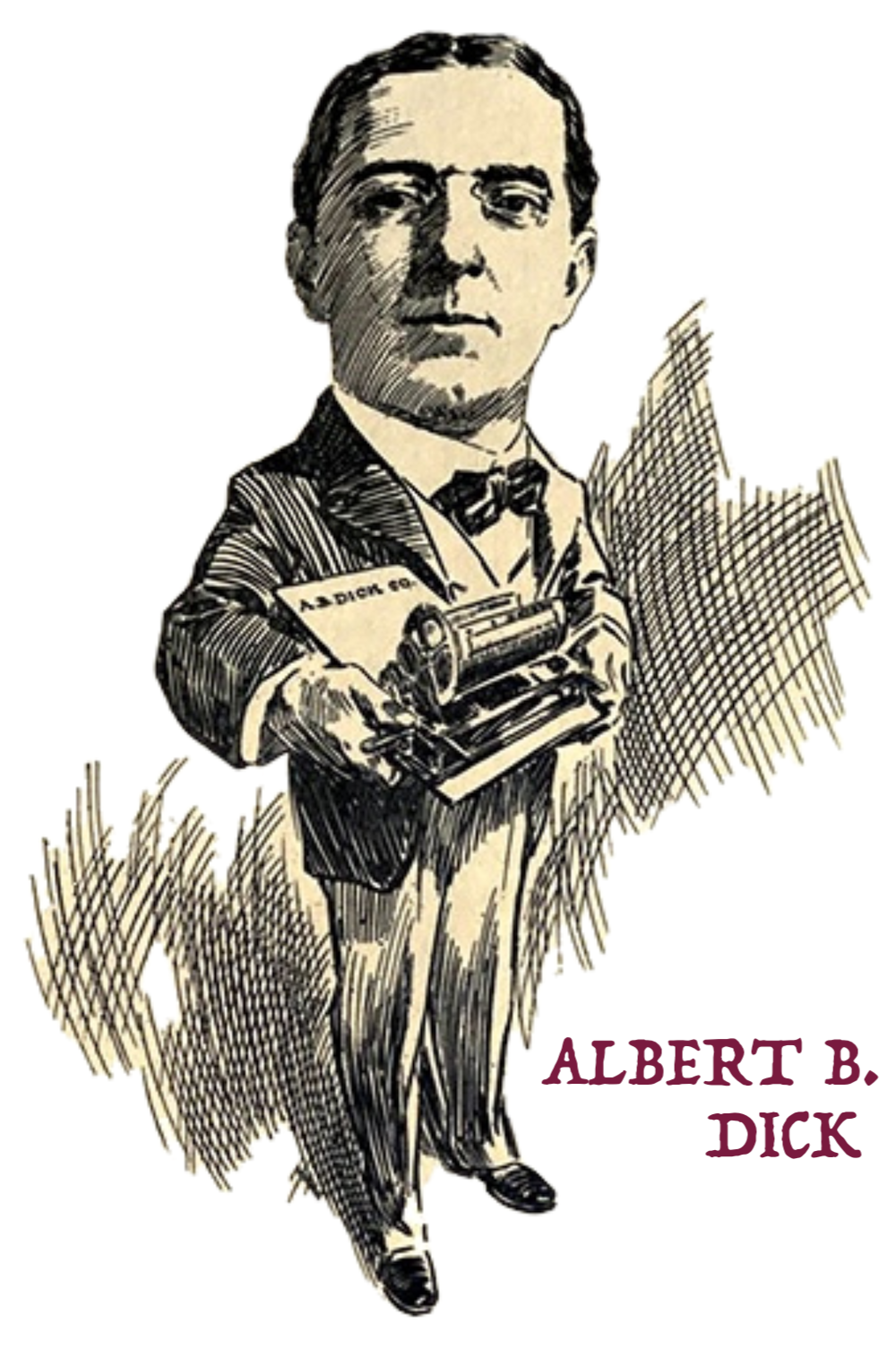

Thomas Edison’s reputation has taken a few stiff punches to the gut in recent years, as the once canonized “Wizard of Menlo Park” has slowly given way to a somewhat less admirable character—one skilled at the arts of patent poaching and monopoly-building at the occasional expense of scientific fellowship. For this reason, the true origins of the mimeograph machine—or stencil duplicator—are likely to remain a bit hazy. Legally speaking, though, it was yet another Edison invention, brought to its fruition in the late 1880s by the further innovations of a Chicago lumberyard owner named Albert Blake Dick [sketched below].

As an 1895 edition of The American Stationer put it, “The A.B. Dick Company, by virtue of an arrangement made in the beginning with Mr. Edison, by subsequent purchases and by various inventions of Mr. Dick himself, controls all of the patents governing the construction of the mimeograph and its proper supplies, and is thus sole manufacturer.”

As an 1895 edition of The American Stationer put it, “The A.B. Dick Company, by virtue of an arrangement made in the beginning with Mr. Edison, by subsequent purchases and by various inventions of Mr. Dick himself, controls all of the patents governing the construction of the mimeograph and its proper supplies, and is thus sole manufacturer.”

Yes, one of the great breakthrough tools in modern communications—which that same article weirdly notes was already in use in “every country on the globe with the single exception of Greenland”—was thoroughly monopolized by the dickish Edison and Edison-esque Dick. This carried on well into the 20th century, even as many challengers took the Dick Company to court to challenge its patent powers.

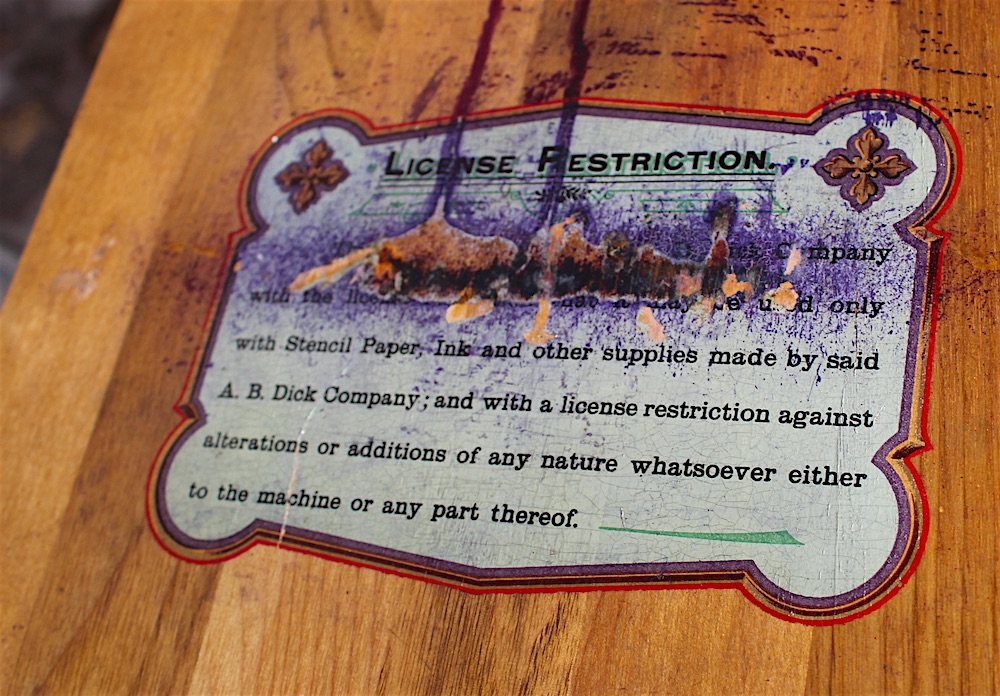

One such case—1912’s “Henry vs. A. B. Dick Co.”—went all the way to the Supreme Court, and became one of the most influential patent law decisions in American history. At the time, the Dick Company was selling its mimeograph machines with “licensing restrictions,” meaning a purchaser could only legally use the machine with stencils, paper, and ink also supplied by A.B. Dick. Incredibly, the company’s power to do this was ultimately upheld by the court in 1912, but it also led directly to Congress passing the Clayton Act two years later, essentially restricting this sort of monopolization of new tech.

Wielding enough power to force Congressional action—that was a far cry from Albert Blake Dick’s early days, when the Galesburg, Illinois native was merely an upstart Chicago businessman annoyed with all the repetitive letter writing his job entailed.

History of the A. B. Dick Company, Part I. Tracing An Outline

“My aim,” Albert Dick later recalled in the pages of his company’s 1934 golden anniversary book, Fifty Years, “was to find a means of duplicating letters other than by printing from movable types—something more economical of both time and money.

“I first attempted to make a typewriter with needle-point type, which would perforate a sheet of paper to make a stencil. But that was not successful. I tried many experiments. I almost let my time and imagination run away with me in the attempt. But I didn’t seem to arrive.”

“I first attempted to make a typewriter with needle-point type, which would perforate a sheet of paper to make a stencil. But that was not successful. I tried many experiments. I almost let my time and imagination run away with me in the attempt. But I didn’t seem to arrive.”

According to lore, Dick finally stumbled upon his solution in 1884 by following a curious whim. He placed a bit of candy wrapper wax paper over a steel file, then drew over it with a piercing awl. When he held the paper up to the light, he had his eureka moment.

“Then I secured the finest file obtainable in Chicago,” Dick said, “traced a few lines on paper held against its surface, and took impressions with a roller and printer’s ink. I then realized I had found the principle for which I was seeking. But the job was not yet done.”

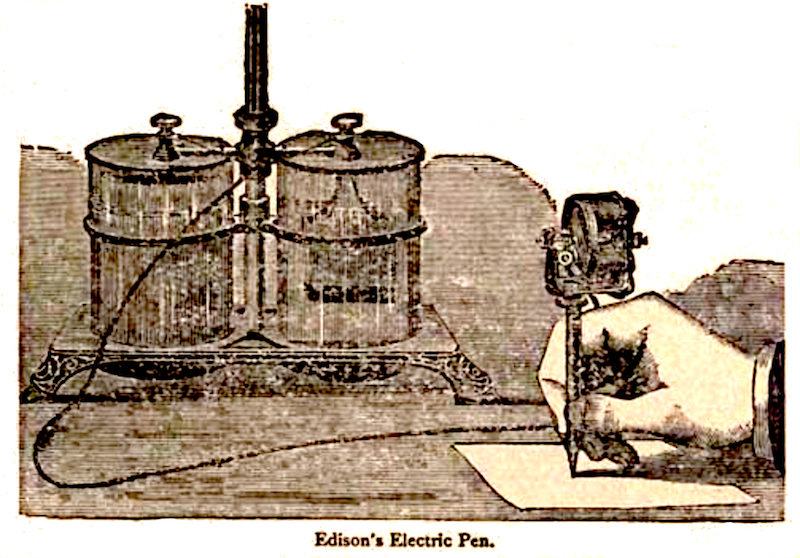

For a while, Dick only used his handy “autograph stencil” to solve his own letting writing issue. But when someone brought up patenting the process and developing a proper machine, he saw dollar signs. He also found some intimidating competition—Thomas Edison’s groundbreaking “electric pen” had already been around for 10 years, and it seemed like any hopes of moving forward with Dick’s machine would result in running into the mighty brick wall of the growing Edison empire. So, rather than challenge the master or flee from him, Albert Dick reached out a friendly hand. And in this fortunate example, 37 year-old Tom Edison was quite amiable himself.

“I immediately got in touch with Mr. Edison,” Dick recalled, “and secured a license agreement to use his patents pertaining to stencil duplication, for Mr. Edison was quick to see the advantages and possibilities of my process. He also furnished me with a device that could be used for coating the wax stencil sheets.”

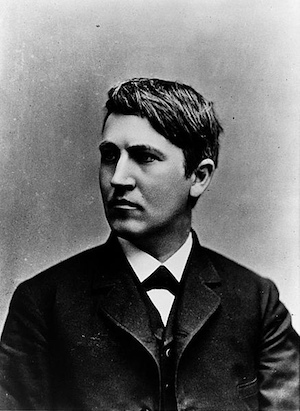

Edison [pictured]—ever motivated by his own dollar signs—saw some advantages to forming a partnership with this 28 year-old Chicago lad, and so, he invested in Dick’s project and forged a long term working relationship and friendship with him. Now all their new machine needed was a name.

Edison [pictured]—ever motivated by his own dollar signs—saw some advantages to forming a partnership with this 28 year-old Chicago lad, and so, he invested in Dick’s project and forged a long term working relationship and friendship with him. Now all their new machine needed was a name.

“I had an old friend in Chicago who was superintendent of one of the schools,” Dick remembered. “He knew that I was on the lookout for a name, and that I didn’t like the term ‘copygraph,’ which had been suggested. One day this friend hit upon the combination of ‘mime’ and ‘graph.’ But it didn’t have the right swing. It wasn’t euphonius. Then the ‘o’ was added, to give it the swing—and the right euphony was acquired.”

The Mimeograph was born—although Thomas Edison did have one last tweak to that name before it hit the market. “We should probably call it the Edison Mimeograph, Albert . . . ya know, just for marketing purposes and stuff,” he said [maybe].

II. Mimeo Mania

The A.B. Dick Company had initially been incorporated in the spring of 1884 as a lumber business, with $25,000 in capital stock (besides Albert Dick, Thomas W. Dunn and Robert R. Harrington were the other incorporators). By 1888, the obsessive stenciling habits of the company president had turned the business into, essentially, a “tech company,” by Victorian standards. The Edison Mimeograph—now refined with nainsook cloths (and later a cheaper Japanese fabric) to handle typewriter stencils—debuted that year. It wasn’t so much a machine, though, as it was an arts-and-crafts kit, complete with a flat bed tray, stylus, roller, and a stack of wax stencils.

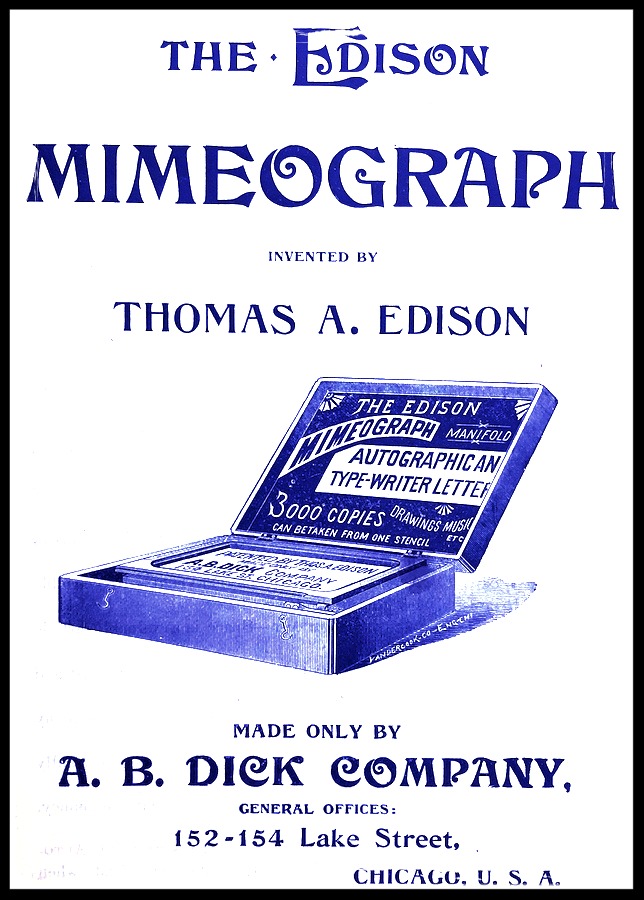

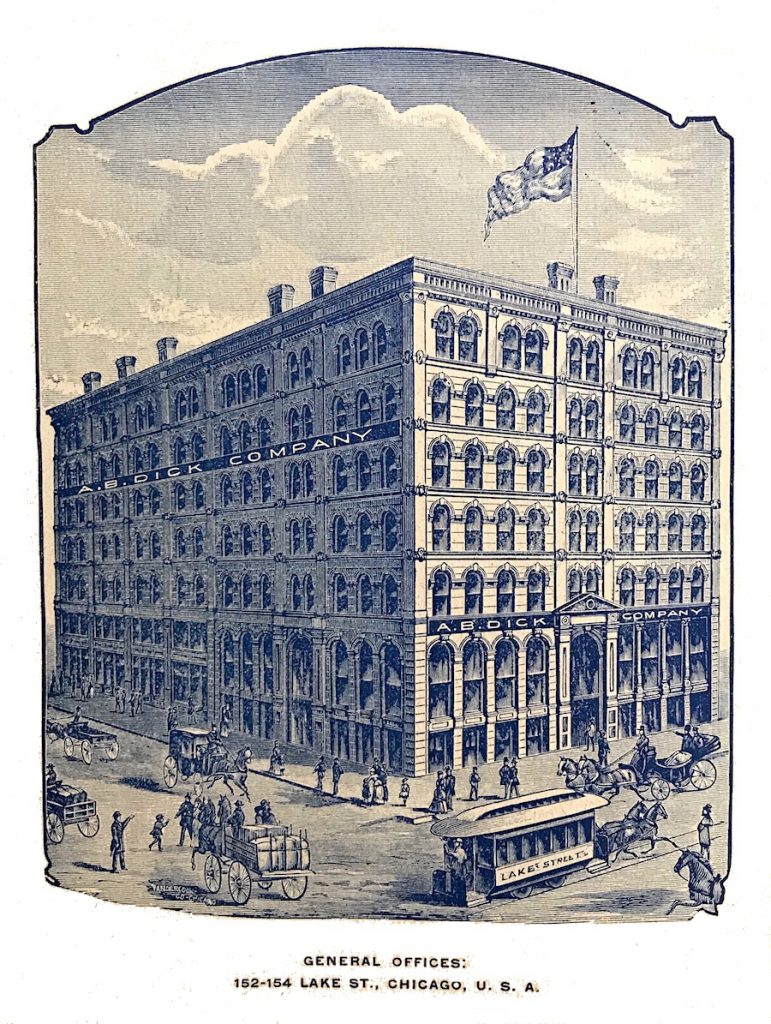

An early pamphlet for the device not only called it the “Edison Mimeograph,” but also included the words “Invented by Thomas A. Edison” on the cover, with no mention of Albert Dick outside of his company’s role as the tool’s sole manufacturer. During these early stages, the A. B. Dick offices were located in a substantial seven-story building at 152-154 Lake Street, with a separate factory location on Desplaines Street.

An early pamphlet for the device not only called it the “Edison Mimeograph,” but also included the words “Invented by Thomas A. Edison” on the cover, with no mention of Albert Dick outside of his company’s role as the tool’s sole manufacturer. During these early stages, the A. B. Dick offices were located in a substantial seven-story building at 152-154 Lake Street, with a separate factory location on Desplaines Street.

After a slow start out of the gate, the Edison Mimeograph quickly and predictably became a phenomenon. If one lumberman in Chicago wanted to save himself the time of re-writing the same letter 50 times, it was safe to assume that thousands if not millions of other people—from railroad men and salesmen to secretaries and school teachers—would share a similar desire.

“The Edison Mimeograph is recognized as the STANDARD DUPLICATING DEVICE for autographic or type-written work by the commercial, educational and religious world,” one pamphlet (c. 1890) claimed. “It will produce copies which so faithfully follow the original that the difference is scarcely perceptible.”

I would go into more detail about how said copies were actually made, but I prefer how The American Stationer handled it in 1895:

I would go into more detail about how said copies were actually made, but I prefer how The American Stationer handled it in 1895:

“No detailed description of the mimeograph—or rather, for the sake of distinction, let it be said Edison’s hand mimeograph—will be attempted here. It is not necessary; it’s stylus, baseboard, stencil sheet, frames, roller, perforating silk, special ink—every detail of its construction and application, in fact—are so well known that to dwell upon them in an article addressed to stationers would be superfluous.”

It was good enough to know that the mimeograph got the job done. The original roller models started at around $20 on average, and could print 600 to 1,000 copies per hour. That was pretty good, indeed. But things would improve in a hurry as the new century dawned.

III. Rotary Style

In 1902, the A. B. Dick Co. moved both its manufacturing and executive offices to 163 W. Jackson Blvd. (which soon became 738 W. Jackson Blvd after Chicago’s street number changes). By 1905, around the time the No. 75 rotary mimeograph from our museum collection was produced, the new factory employed 191 workers—143 men, 48 women, and surprisingly enough, no children.

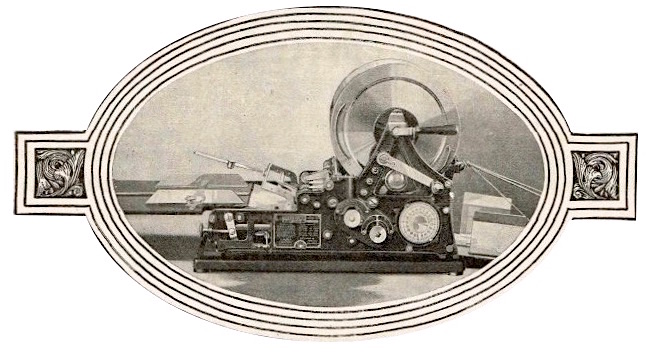

While the Dick Company did manufacture some other products during these early years (including wood filing cabinets and other office conveniences left over from its lumber days), most of the focus was on the next evolution of the duplicator: the “rotary mimeograph.” This new design substituted the sometimes cumbersome flatbed tray and hand roller with a simple turning crank, automatic ink, and a rotating cylindrical drum that looks like a lottery ball dispenser.

Advertisements hailed the rotary mimeographs as “the next step after the typewriter in office economy” and “as far ahead of the typewriter as the typewriter is of the pencil.” That may have been true in some respects, but duplicators still needed an original typewritten or hand drawn document from which to do their magic. A. B. Dick tried to remedy that situation by developing its own typewriter for a while, but it never really took off. They were forever pigeon-holed in their role as the “copy people.”

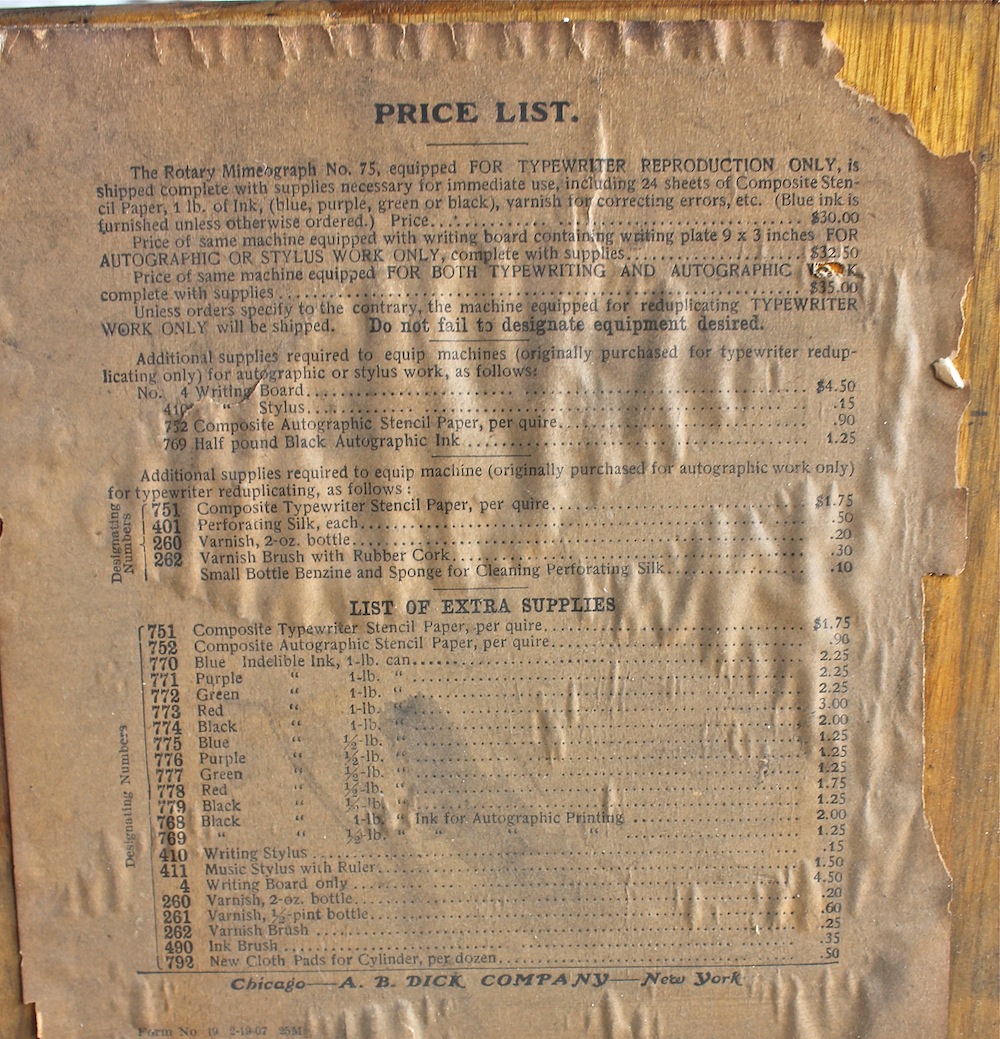

The Edison No. 75 in our collection was equipped only for typewriter reproduction, but the same model came in different variations for handwriting work or dual purpose copying. It was a big seller during the first decade of the 1900s, and included the infamous License Restriction that forced buyers to only use A.B. Dick accessories with the device.

“The Day Has Come,” read a 1907 newspaper ad for the No. 75 in the Charlotte Observer. “when a duplicating machine is a practical or absolute necessity in every progressive business office.

“The Day Has Come,” read a 1907 newspaper ad for the No. 75 in the Charlotte Observer. “when a duplicating machine is a practical or absolute necessity in every progressive business office.

“The No. 75 Rotary Mimeograph is the result of a universal demand for a simple, rapid and economical duplicating machine which will do perfect work. Its strong points are Simplicity, Durability, Rapidity, Cleanliness, Quality of Work, Portability [the drum and its wood base hooked onto a protective green metal cover with a carrying handle], Price, Compactness, Noiselessness, and a device for counting copies.”

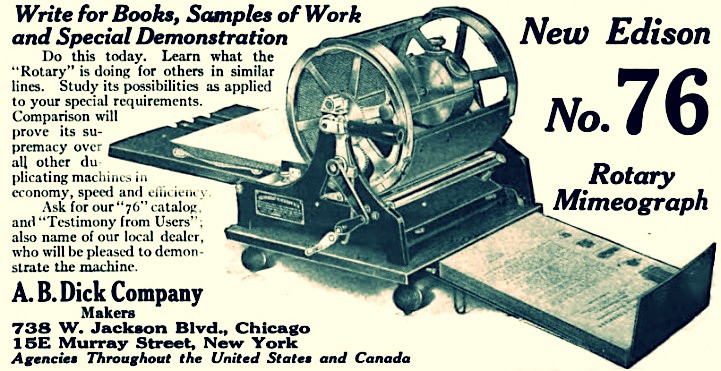

The cost for the machine had risen to $30, but its productivity potential had grown accordingly, with the similar Model No. 76 able to churn out 17,000 to 20,000 copies per day, or a rate of 50 to 100 per minute, depending on the skill of the drum spinner.

[1912 ad for the No. 76 Edison Mimeograph, from Cosmopolitan magazine]

[1912 ad for the No. 76 Edison Mimeograph, from Cosmopolitan magazine]

“This marvelous duplicating machine—the Edison Rotary Mimeograph—places you in command of one of the mightiest constructive forces employed in the business world,” according to a full page ad in a 1912 issue of Cosmopolitan. “The Typewriter, the ‘Rotary’ and the U.S. Mails, working in unison, are irresistible trade winners for merchants and manufacturers.”

That same year, 1912, was the final bow for the old wax stencils, as the company’s tougher “Dermatype” stencils took over the designs for the next decade. When the Edison Mimeograph 77A debuted shortly thereafter, historians believe it was likely used to produce a copy of each and every order communicated by the U.S. Military during World War I.

IV. The Automatic Age

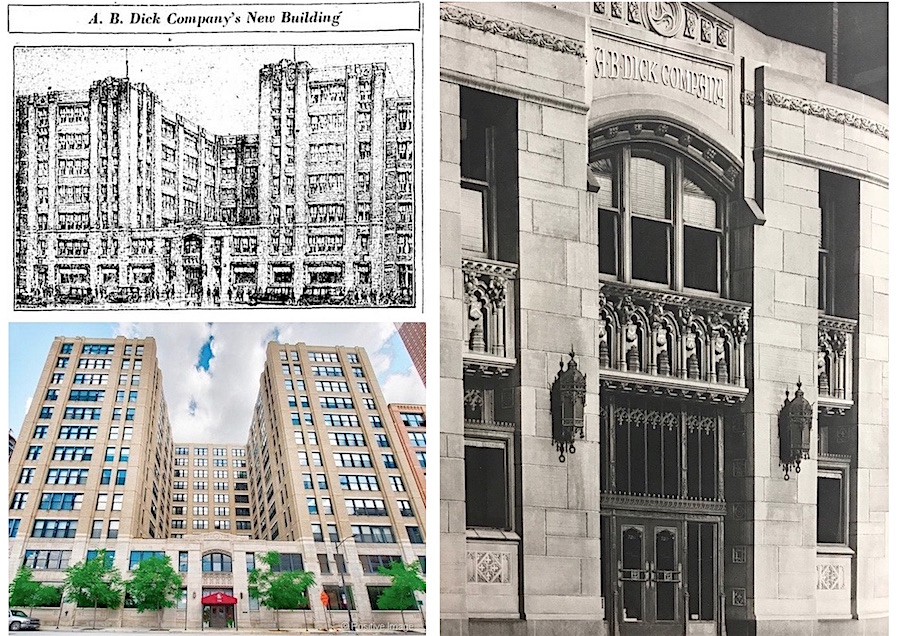

During the 1920s, the A.B. Dick Co. had offices in most major cities in the U.S, and it expanded its Jackson Blvd. headquarters in Chicago with a brand new eight-story, neo-gothic high-rise at 728 W. Jackson, designed by the famed local architect Alfred S. Alschuler. Within a few years, the company’s demands were great enough that another five stories was plopped on top of the building. It would remain A.B. Dick’s home for over 20 years, and would later house the offices of the Hart Schaffner and Marx clothing company. In more recent years, the West Loop building has taken on new life as the upscale “Haberdasher Square Lofts.”

[728 W. Jackson Blvd., A.B. Dick Co. headquarters from 1926 to 1949]

[728 W. Jackson Blvd., A.B. Dick Co. headquarters from 1926 to 1949]

From inside the walls of this fancy new home, Dick’s prime product—now finally known officially as the “Edison-Dick Mimeograph”—continued to evolve. The “Mimeotype” stencil sheet, first developed in 1924, didn’t need to be moistened like earlier sheet types, dramatically improving ease of use. Shortly thereafter, the mimeo machine itself went fully electric and mostly automatic, producing terrific results for any company still in business during the Great Depression.

“As a factor in economy the Mimeograph now towers as a giant,” read a 1932 ad. “There’s no other means of turning out letters, sales data, announcements, bulletins, lists, charts and forms of all kinds so speedily, so economically. By the thousands every hour it duplicates whatever you write, type or draw on its stout stencil sheet.”

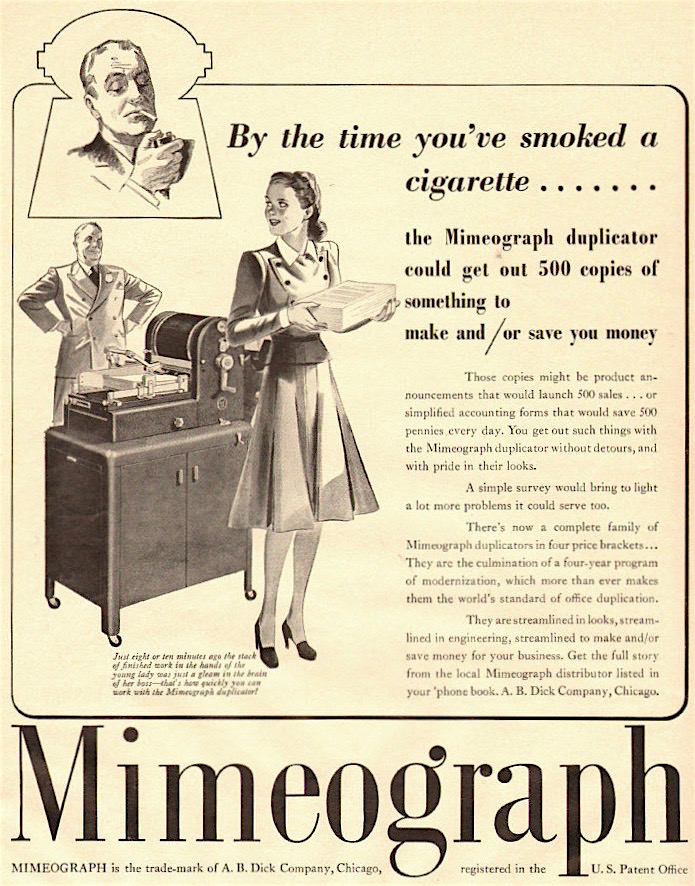

“By the time you’ve smoked a cigarette . . .” a 1940 ad boasted, “the Mimeograph duplicator could get out 500 copies of something to make and/or save you money.”

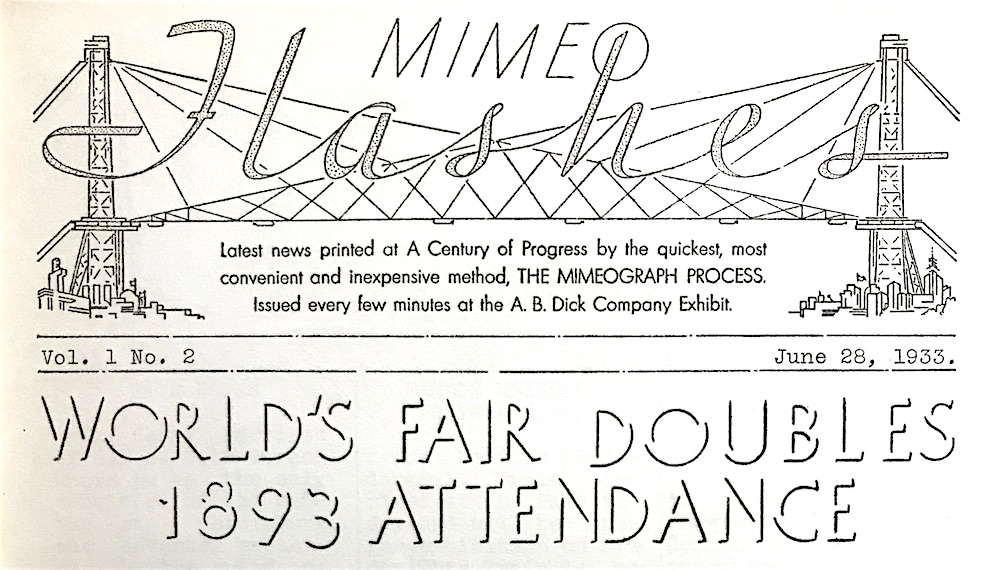

[A.B. Dick had its own exhibit at the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago, and produced a daily newsletter called “Mimeo Flashes,” using its own Mimeotype technology]

[A.B. Dick had its own exhibit at the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago, and produced a daily newsletter called “Mimeo Flashes,” using its own Mimeotype technology]

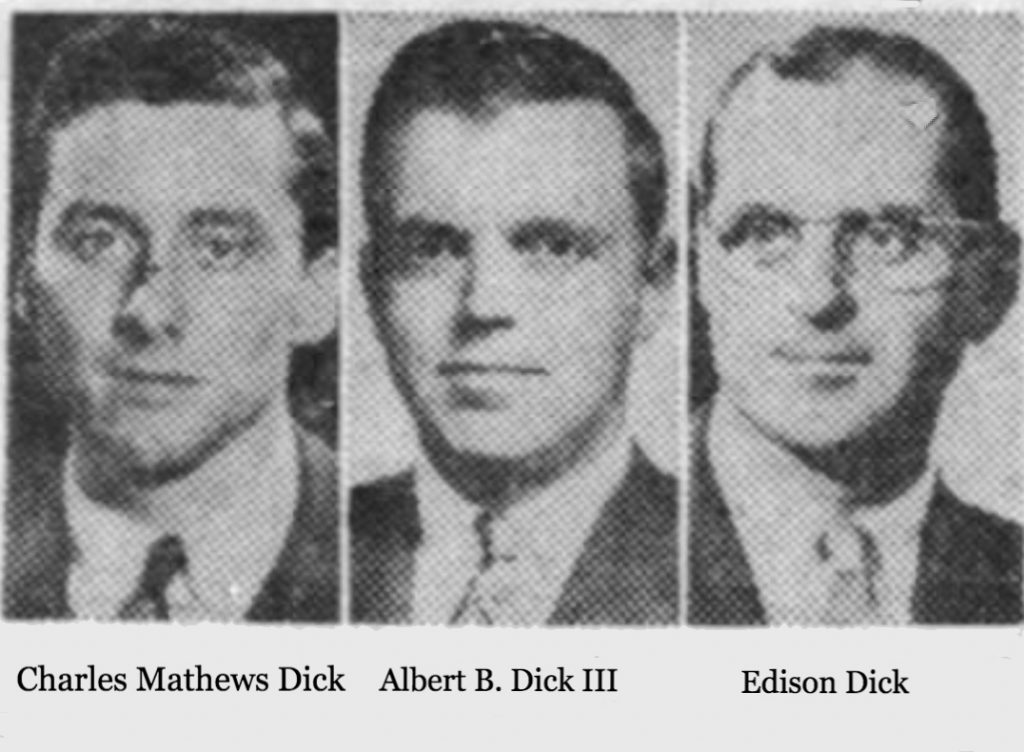

The A.B. Dick Co. celebrated its 50th anniversary in 1934, and with 900 workers in its employ, it had become one of the city’s most respected and resilient enterprises. Even after the death of Albert Blake Dick that same year, aged 78, the company was left in capable hands, with Dick’s sons Albert Jr. and Edison Dick taking over the reins. Its dominance in the duplicator industry would become harder to cling to in the years after World War II, however, as the double-whammy of new competition and the march of technology made for plenty of sleepless nights.

One of Dick’s chief emerging rivals was another Chicago company, Ditto Inc., which manufactured “spirit duplicators”—a similar product that utilized pungent chemical solvents, rather than ink, to produce copies. Into the 1950s and ‘60s, even the word “Ditto” became more of the generic lingo for making copies in an school building or office, as “mimeo” gradually faded. Both brands, of course, were fighting an ultimately losing battle without realizing it. The Xerox age was just waiting around the corner.

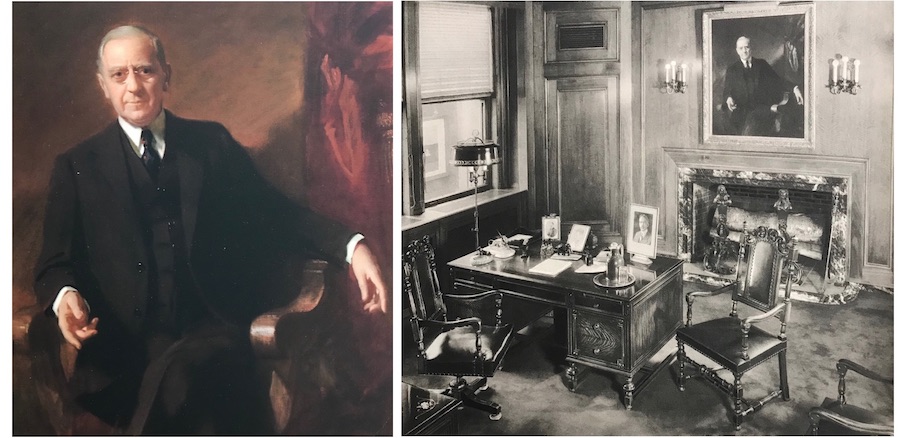

[Left: A painting of Albert Dick Sr. in his later years. Right: Albert Dick Sr.’s office in the 1930s, with his own portrait hanging on the wall right in front of his desk. Bit odd there, Al. Bit odd.]

[Left: A painting of Albert Dick Sr. in his later years. Right: Albert Dick Sr.’s office in the 1930s, with his own portrait hanging on the wall right in front of his desk. Bit odd there, Al. Bit odd.]

V. Stayin’ Alive

Fortunately, Albert Blake Dick III, grandson of the company founder, wasn’t willing to let his family business go down with the sinking ship of the mimeograph era. Shortly after the factory was done producing Norton bomb sights and aircraft landing gear for the war effort, the man we’ll call “ABD3” assumed the presidency in 1947, and remained a guiding force for over 30 years.

Rather than timidly clinging to “the old ways,” ABD3 and his cousin Charles Mathews Dick, Jr. (VP of Sales and Marketing) jumped on dozens of opportunities for expansion into new products, including everything from Dick’s own version of the spirit duplicator to early breeds of photocopiers and primitive computer technology. Those efforts, while hit or miss, ultimately helped the company survive the 20th century as something other than a footnote.

Rather than timidly clinging to “the old ways,” ABD3 and his cousin Charles Mathews Dick, Jr. (VP of Sales and Marketing) jumped on dozens of opportunities for expansion into new products, including everything from Dick’s own version of the spirit duplicator to early breeds of photocopiers and primitive computer technology. Those efforts, while hit or miss, ultimately helped the company survive the 20th century as something other than a footnote.

After leaving Chicago for a major new complex in suburban Niles in 1949, the A.B. Dick Co. had a working staff of over 1,400 throughout much of the ’50s, including a large team stationed in “an acre of space devoted to research,” according to a 1959 company profile by Chicago Tribune writer William Clark.

“It is a true but misleading statement,” Clark wrote, “that the A. B. Dick company built its business around a single product, the mimeograph machine, for 65 years. It is misleading because the vast improvements wrought in the machine, the increasing number of different models in the line, and the company’s research and development in such areas of supply as inks, stencil sheets, and paper coatings provided greater product diversity than one would suppose.”

The Tribune scribe also hailed the Dick family (Albert Jr. and Edison were still chairmen at the time) as having “distinguished itself in community service as well as in industrial achievement. The members who have served the company have been well grounded in all of its operations, and have not been backward about going outside on occasions to acquire talent to create a well balanced, aggressive management team.”

Upon his death forty years later in 1989, Albert Dick III was further praised by a family friend. “His work was important to him, but the people who worked with him were more important. As an example, he could remember the names of thousands of employees at A.B. Dick Co., and he directed the company with great concern for the generations who had worked with his family since it began over 100 years ago.”

Even through the 1970s, when the mighty Xerox was presumably hammering the old mimeograph makers into submission, A. B. Dick was actually still one of the leading employers in Chicagoland, with upwards of 3,000 workers in Niles, and many more across the country. A sale to General Electric of Great Britain in 1979 didn’t stop the plant’s operations, nor did a few subsequent handoffs and a merger with the Multigraphics company in the 1990s, although the Niles staff dipped below 1,000.

With its wheels spinning, A.B. Dick Co. went into bankruptcy in 2004, but was rescued by Presstek, Inc., which later dumped its old ABDCO brand properties into the basket of a Missouri’s Mark Andy Print Products company in 2013.

The former A.B. Dick plant in Niles at 5700 W. Touhy Ave appears to have gone under the wrecking ball around 2008, and the location is now home to a shopping plaza with a Verizon store and a Starbucks. You could almost say it was a direct mimeo copy of every other suburban plaza in America.

[The opening of the A. B. Dick plant in Niles, 1949]

Sources:

The Edison Mimeograph – Sales Pamphlet, 1890

Fifty Years: A.B. Dick Company, 1884-1934

Mimeo Flashes: A Century of Progress, 1933-34

“Dick Family” – Lake Forest – Lake Bluff Historical Society

“Communications Recording Field, That’s Home For A.B. Dick Co.” – Chicago Tribune, Oct 17, 1959

abdick.com – Mark Andy Print Products

“Ex-Exec at A.B. Dick, Grandson of Founder” – Chicago Tribune, May 23, 1989

Henry vs. A.B. Dick Co., U.S. Supreme Court decision, 1912

Archived Reader Comments:

“As the former CEO of a national chain of franchised retail or “quick” printing shops, I’d be very interested to know what became of the historical archives of the A.B. Dick Company. In their former headquarters in Niles, IL., there we files upon files of production records and advertising materials dating back to the late 19th century. In 2001 I was granted access to those files and made copies of some of them. What ever happened to that historical treasure trove?” —Dave Oswald, 2017

“Many records 1884-1998 of ABDick are in the Benson/Ford Research Center. The have most all materials from ABDick. You can research or buy material from the org. for a fee. ” —Samuel Keller, 2018

” —Samuel Keller, 2018

I have six different service manuals that were my Dads. He worked for ABDick 1950 – 1990. I would like to pass on to a collector or museum. Any idea as to who I could contact? I hate to toss them in the garbage.

Je possède le mimeographe n° 78. Si vous avez son manuel d’entretien, même en pdf, ça serait sympa pour le joindre à mon mimeo. Merci

In 1963 there was a U S Army MP in Japan where I was stationed. I think he was A. B. Dick IV.

Dear Sir or Madam,

I am writing to inquire about the possibility of obtaining an image license for an upcoming exhibition. Specifically, I am interested in using the picture entitled “A painting of Albert Dick Sr. in his later years.”

The exhibition, titled “Construction Project of the Exhibition Area of the Legislative Yuan Museum’s Legislative Building,” is a permanent display set to open this October in Taiwan.

One section of the exhibition will focus on the history of the mimeograph room, and we believe that your picture would be a fitting addition to this narrative.

Should you have any questions or require further information, please do not hesitate to reach out to me. Your prompt response would be greatly appreciated.

Thank you for considering my request.

Sincerely,

I was employed by the A B Dick Atlanta Distributor in 1958, then moved to Chicago as a product inventor in 1969 (I worked with both Gary & Tonya Richardson), then to North Carolina to purchase the largest US A B Dick Distributor in 1974. Mr. ABD III was a gracious, much admired and wonderful person. His company nurtured and churned out dozens of successful business owners.

I used an ABD machine while working at Firestone Tire and Rubber in South Gate, CA, in the mid-70’s. I am wondering what the technology was called for the ABD machine that was used in the early 1970’s with a telephone and thermal paper and was an early model facsimile (fax) machine . Both the sender and receiver had to communicate on their phone, then each had to put their phone receivers into a cradle on the machine. The sender placed the typed or handwritten paper in the machine and the machine emitted beeping sounds that transmitted images to the receiving party’s thermal paper. As I recall, this process did not work very well if the sender’s page had a lot of numbers on it. Since I worked for a tire sales division of FT&R, that is what I used to transmit to the National Sales Office in Columbus, OH.

Hi my name is Giovani Bautista so I went to a yard sale I live here in La Mirada California went to a yard sale and the first thing I can’t my eye was this printer that at the time I don’t know what it was I bought it just because they look really antique I did not know what I was buying came home did my research and I found you guys I would like to know what is a price on this just curious

Dear all,

It is a very long shot, but I am hoping that someone might possibly have some information regarding a designer/illustrator who worked for this company in the late 1920’s, Donald Denton.

This artist also illustrated a few books (how I came to hear of him) but apart from knowing he was active in the Chicago area in the 20’s and that he was associated with a small press called the Peacock Press I know absolutely nothing more. Any information would be very gratefully received!

How would you get an estimate of one of these I found at a sale. Almost perfect and has serial number on it.

Jeanie you can call me if you like i am listed in Huntley ill phone book.

Frank, What luck I just happened on this website again. Is there any information online about exactly what happened to him? He passed away last year and I am trying to find out more about his accident. We were together for the past 25 years after his first wife died in 1995. So sad. Jeanie Richardson I admired him greatly!

I know Gary about 3 years after he got hurt in the boiler house.

I am doing some research on a former employee. Is there anyone who knew Gary A Richardson? He worked at AB Dick during the 60’s in Chicago and then as a salesman in Atlanta GA. Any info at all would be appreciated

I have an AB Dick Automatic Folding machine That was patented in 1900 I have never seen anything on the Internet that looks like it have you ever heard of an A.B. dick automatic folding machine It has handcrank in it also does a cross fold with a receding stacker

Hello, my dad has a mimeograph just like the one is advertised where it says “By the time you smoked a cigarrete…” and he was looking for parts like the rubber round things that pushed the sheets. It has been abandoned in his house now, It will be nice to retore it.