Museum Artifact: Denoyer-Geppert Cartocraft Globe, 1938

Made By: Denoyer-Geppert Company, 5235 N. Ravenswood Ave., Chicago, IL [Edgewater]

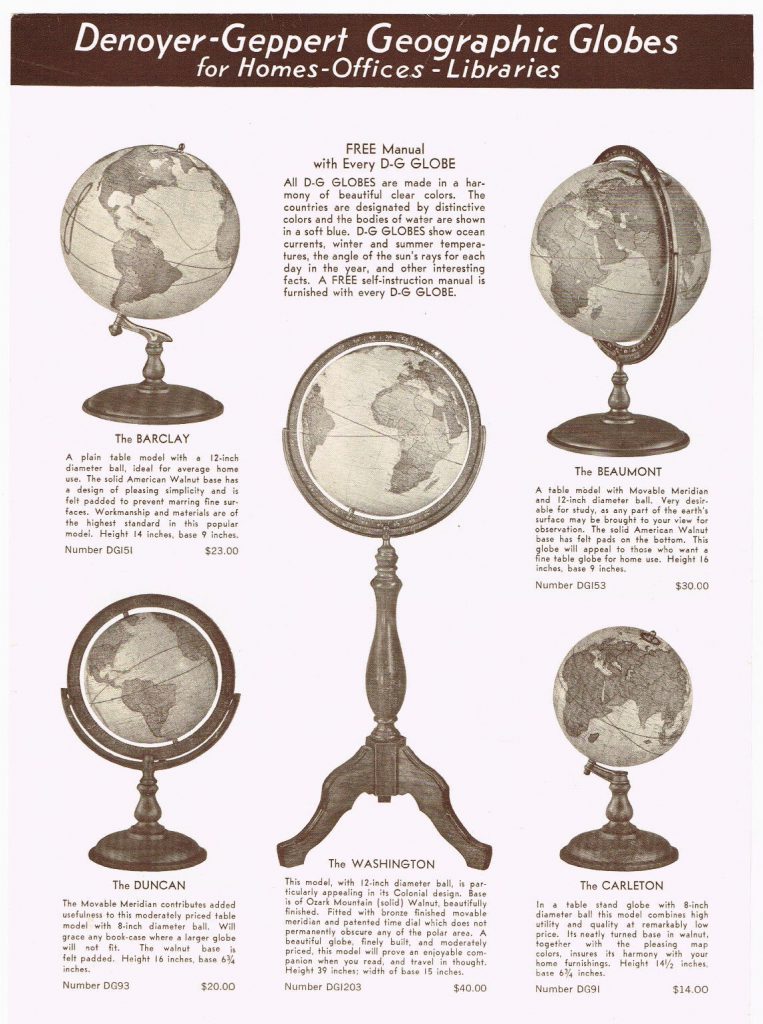

“You now have one of the best globes made,” L.P. Denoyer wrote in the preface to his 1931 guide book, A Teacher’s Manual for Cartocraft Globes, “but we are not satisfied with simply having made the sale, for we want you to get the greatest possible value from your purchase.”

Well, Mr. Denoyer, the fact that I am even looking at your globe today—roughly 80 years after you plopped it on its axis—probably suggests its greatest possible value has indeed been realized.

Generally, if we’re talking about Chicago companies associated with maps, atlases and spherical cartography, two names will always prevail: Rand McNally and Replogle Globes. The Denoyer-Geppert Co. deserves its rightful place in that conversation, however—presuming you really are the sort of person that has conversations about such things.

Generally, if we’re talking about Chicago companies associated with maps, atlases and spherical cartography, two names will always prevail: Rand McNally and Replogle Globes. The Denoyer-Geppert Co. deserves its rightful place in that conversation, however—presuming you really are the sort of person that has conversations about such things.

Before selling their globe and map-making assets to Rand McNally in 1984, Denoyer-Geppert had logged a solid 68 years in that industry—most of them spent at the same aesthetically charming map factory in Edgewater: 5235 N. Ravenswood Avenue (former home of the Swedish-American Telephone Co. and now a landmark on the National Register of Historic Places). The company left that plant for good after the McNally sale, but they stayed in business, relocating to Skokie and re-emerging as the Denoyer-Geppert Science Company—a leading manufacturer of human anatomical models for advanced classroom and laboratory use. Their current Skokie headquarters is actually just a few miles down the road from Rand McNally’s, but that old rivalry lost its teeth long ago.

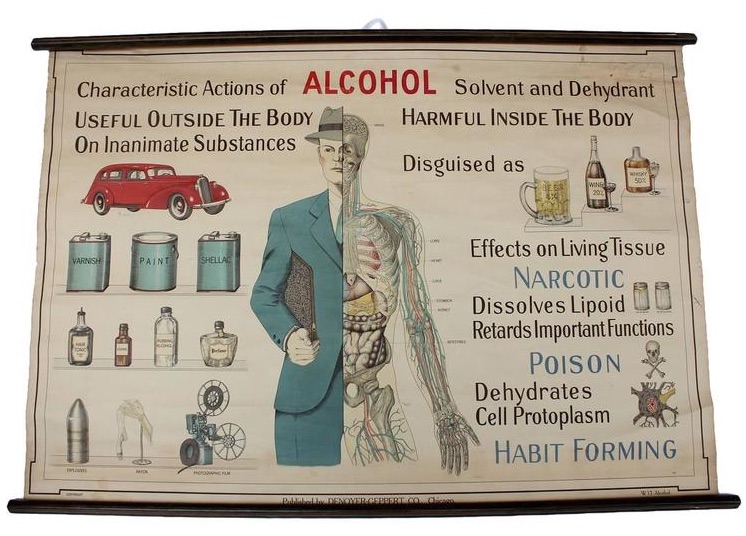

Denoyer-Geppert’s current focus on biology sculptures is not entirely out of left field. From its earliest days, the firm never limited itself to the map-and-globe game. Its founders, if one can dare believe it, were genuinely dedicated to the field of education, and they developed a wide range of visual aids to help teachers better instruct their youngins. If you think about it, making accurate 3-D models of the human heart—or giant canvas pull-down charts about the harmful effects of alcohol consumption—served the same purpose as making an accurate representation of the planet.

[An example of a mid-century Denoyer-Geppert school room chart – quite a work of art in its own weird way]

[An example of a mid-century Denoyer-Geppert school room chart – quite a work of art in its own weird way]

“A map is the visual symbol of something too big [or, by the same logic, too hidden] for the eye to encompass,” Otto E. Geppert wrote in a 1942 issue of The Rotarian.

“Perhaps it is even more than that. When you think of England or of Italy or of Australia, do you not think first of its shape upon the map? Yet no one has ever seen that shape in its totality [not in 1942, anyway]. A map is a potent educative tool, too. But we need to know how to use that tool. It is as important to know its limitations as it is to know its potentiality.”

“Perhaps it is even more than that. When you think of England or of Italy or of Australia, do you not think first of its shape upon the map? Yet no one has ever seen that shape in its totality [not in 1942, anyway]. A map is a potent educative tool, too. But we need to know how to use that tool. It is as important to know its limitations as it is to know its potentiality.”

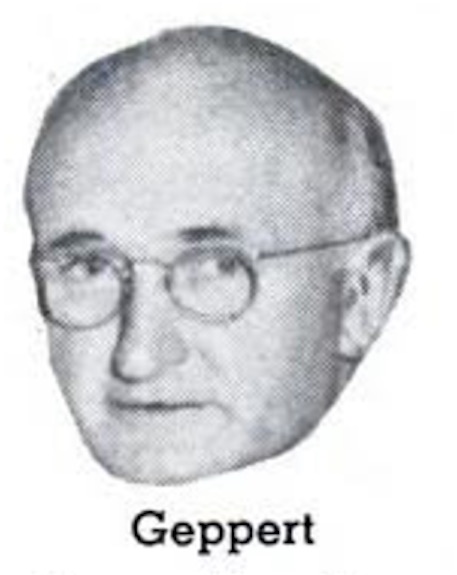

Geppert—who admittedly looks like an anthropomorphic globe in his photo—was writing at a time when demand for maps and globes was at an all-time high—smack in the middle of World War II. In the span of just a few years, the globe in our museum collection—which appears to date from the late 1930s just before the war began—was already spinning into ancient history. People wanted to understand the full scope of the Pacific Theater, and what borders were being defended in Europe. They wanted a sense of how far away their boys were, and how close the enemy might be lurking. “Global war calls for global minds,” Geppert added, “and they, in turn, call for global maps.”

Denoyer-Geppert fulfilled these needs not just with basic plaster globes and flat-maps, but with designs that were interactive, innovative, and full of rich context.

Denoyer-Geppert fulfilled these needs not just with basic plaster globes and flat-maps, but with designs that were interactive, innovative, and full of rich context.

One of the company’s most celebrated globes was a 20-inch wartime model made from industrial, hollow-spun metal with a minimalist three-color look: blue water, black land masses, gold outlines. Besides being exceptionally bad-ass, it was also the favored globe at many military bases, as officers could write on it with chalk—hence the name, “Slated Outline Activity Globe.” Today, those suckers [pictured above] routinely sell for upwards of $2,000.

The globe in our collection has more of a traditional construction, although the base is a solid cast iron and the colorization—while faded by time—is lovely and varied. L. Philip Denoyer himself is credited right on the label as the editor of the piece. He was 63 at the time; still about a decade shy of retirement. He would remain president of the company, more in an advisory role, until just a few months before his death in 1964, age 88.

[Though the 12″ globe in our collection doesn’t include a date of production, the names of countries and borders suggest it was made in the late 1930s, before WWII]

[Though the 12″ globe in our collection doesn’t include a date of production, the names of countries and borders suggest it was made in the late 1930s, before WWII]

“The editor of a globe map must keep constantly before him the purpose for which the globe is to be used,” Denoyer wrote in his 1931 manual. “This can only come from teaching experience or from observation of teachers who are experts in globe instruction. Unfortunately, until recently, few globe maps have been made by editors of teaching experience, and the maps, as a consequence, had on them much material that could not be used. On the other hand, some recent globe maps have been made omitting essential material which must be shown in order to get the most use out of the globe.”

Was Denoyer taking a jab at upstart globe makers like Luther Replogle, who came from a sales background rather than an educational one? Eh, not necessarily. Denoyer’s own partner, Mr. Geppert, was a career salesman himself. The point seems to be that, no matter the nature of the business required to sell your globes, you better be sure they’re more than just a pretty thing to look at.

Was Denoyer taking a jab at upstart globe makers like Luther Replogle, who came from a sales background rather than an educational one? Eh, not necessarily. Denoyer’s own partner, Mr. Geppert, was a career salesman himself. The point seems to be that, no matter the nature of the business required to sell your globes, you better be sure they’re more than just a pretty thing to look at.

Denoyer—who, if we’re being honest, looks very much like his business partner, and thus, very much like a globe—saw his industrial career as an extension of his first career as an educator. Born in Milwaukee in 1875, he was already a high school principal in Urbana, Illinois, by the age of 32, and was doing his graduate studies at the University of Chicago during the same period. In 1909, he was named the first Professor of Geology and Geography at the State Teacher’s College – La Crosse (University of Wisconsin). It was while teaching a course there—legend has it—that Denoyer first crossed paths with a globe salesman named Otto E. Geppert, who’d traveled up from Chicago to sit in on the class.

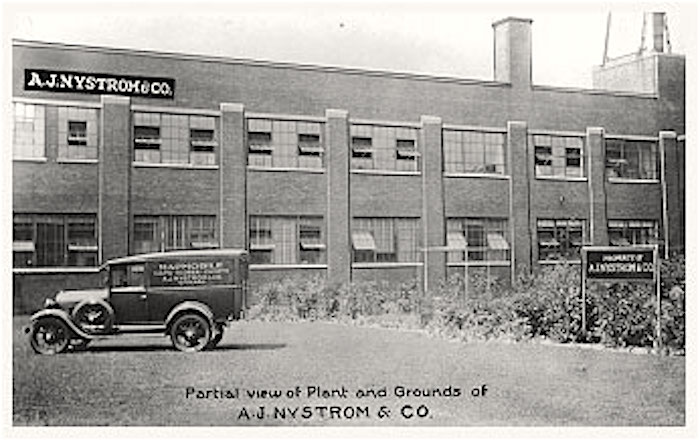

Geppert was just a kid fresh out of school himself, and was employed by A.J. Nystrom & Co., a Chicago mapmaker that had an exclusive distribution deal with the revered W. & A.K. Johnston firm of Edinburgh, Scotland. Nystrom, it should be noted, also still exists today in a loose approximation of its original form, self-identifying as “the United States’ oldest publisher of wall maps and globes for classroom use” (founded in 1903). The Nystrom building at 3333 N. Elston Ave. in Avondale has also remained in continuous use since 1928.

[The factory of A.J. Nystrom & Co. in the 1920s. Denoyer and Geppert first worked together at Nystrom from 1913 to 1916]

[The factory of A.J. Nystrom & Co. in the 1920s. Denoyer and Geppert first worked together at Nystrom from 1913 to 1916]

Anyway, Geppert felt Nystrom & Co. could benefit greatly from the expertise of an esteemed gentleman like Professor Denoyer, so he put on the hard sell. Denoyer had some reservations, but eventually agreed to take a temporary leave from his college gig to return to Chicago. He’d seen enough globes to know they weren’t up to his own high standards. “And if you want something done right. . .” Suffice it to say, he never wound up going back to La Crosse.

For three years, Denoyer learned the business end of mapmaking from Geppert and the Nystrom team. The company was quite successful, but after a while, some differing philosophies began to emerge—as tends to happen. Denoyer felt he’d learned enough to go independent, and his young cohort Otto Geppert was more than happy to join him in the venture. They formed the Denoyer-Geppert Company in 1916, with L.P. making the maps and Geppert selling them to the masses.

Within just six years, the company moved from a 500 square foot garage to what would become its longtime 50,000 sq. ft. home in the Swedish-American Telephone Building.

[Above: 5235 N. Ravenswood Ave., home to Denoyer-Geppert from 1922-1985, seen here in 1930 and 2018. Below: Workers mounting and trimming scientific charts in the factory, c. 1930]

[Above: 5235 N. Ravenswood Ave., home to Denoyer-Geppert from 1922-1985, seen here in 1930 and 2018. Below: Workers mounting and trimming scientific charts in the factory, c. 1930]

Reporting on the company’s progress in 1922, Dr. A.E. Winship of the Journal of Education could barely contain his enthusiasm:

“Denoyer-Geppert Company in their new office plant on Ravenswood Avenue, Chicago, Illinois, have demonstrated remarkable business success in the making and marketing of maps and charts as aids in the teaching of geography and history, and models in aid of teachers of botany, agriculture, zoology, and physiology . . .

“The visual demonstration of the growth may be seen at a glance by studying the two catalogs just issued, the most surprising revelation of the possibilities of such a business that we have ever seen. This catalogue lists 1,200 maps, charts, globes, and associate aids in teaching geography and history, and 800 brilliantly illuminated biological charts and anatomical models. There is literary art in the descriptions and illustrative art in beautifying the book for educational effect.”

“The visual demonstration of the growth may be seen at a glance by studying the two catalogs just issued, the most surprising revelation of the possibilities of such a business that we have ever seen. This catalogue lists 1,200 maps, charts, globes, and associate aids in teaching geography and history, and 800 brilliantly illuminated biological charts and anatomical models. There is literary art in the descriptions and illustrative art in beautifying the book for educational effect.”

The same writer seemed particularly taken with Professor Denoyer’s commitment to the intellectual side of the pursuit and the “profound thought and meticulous care” he put into his products.

“It is [Denoyer’s] belief in history, his love for ‘Current History,’ his mastery of historical geography that has always been in evidence,” Winship wrote. “It is needless to say he realized that there was nothing in the map world, either in history or geography, that has met the needs of those who proposed to lead all teachers in these fields.”

Mr. Winship’s final summation of his trip to the Denoyer-Geppert plant reads more like a declaration of verified miracles and imminent sainthood than a review of a globe factory.

“When the school master with a vision makes an ideal real, all the school world is the gainer. Any man is worthwhile whose message has a mission. On a desert a mirage reveals a lot of things that are not there, but in a forest you may select a path of light, a vista, with the glorious scenery far away. Here we have a wall map vista that will transform the history and geography classroom for years.”

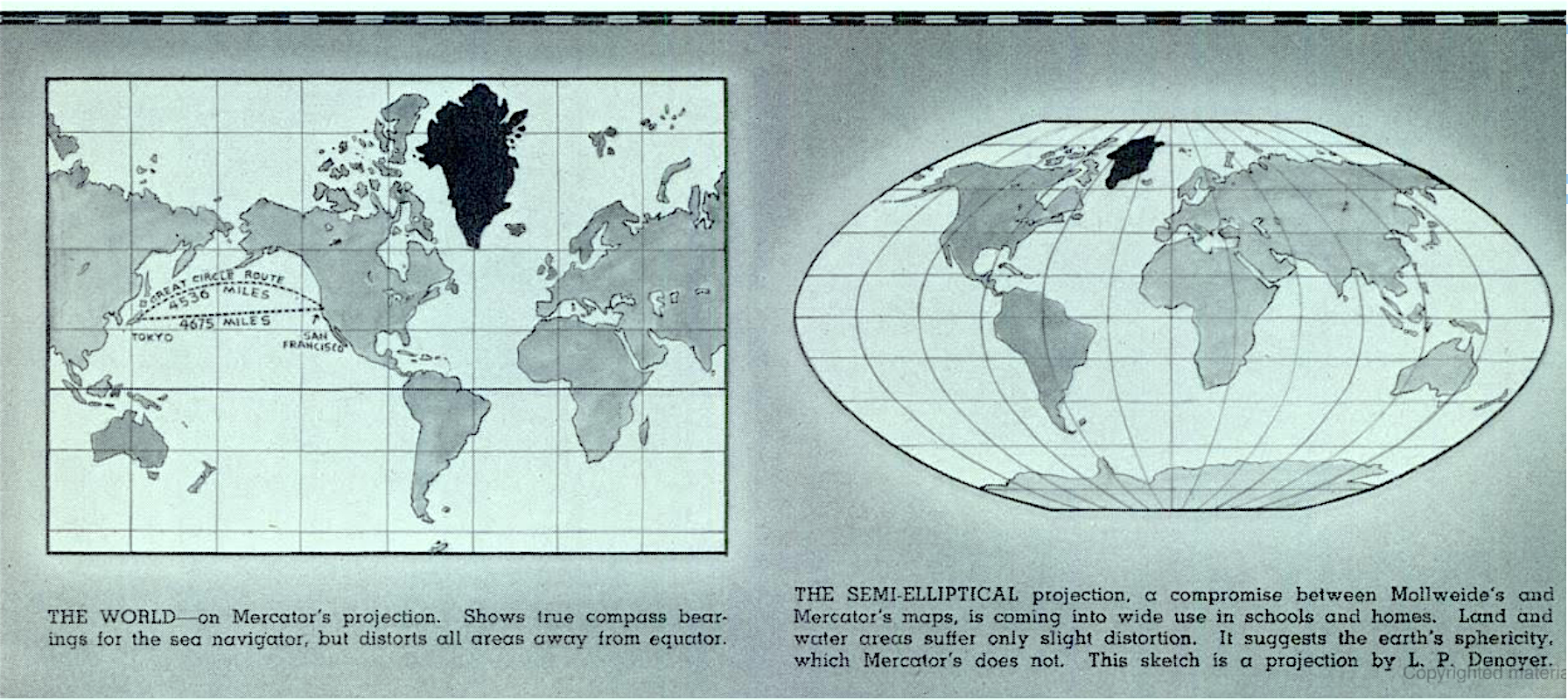

[One of L.P. Denoyer’s most famed contributions to the industry was the “Semi-Elliptical Projection,” an improvement on the classic Mercator Projection that attempted to resolve that old problem of Greeland looking stupidly gigantic]

[One of L.P. Denoyer’s most famed contributions to the industry was the “Semi-Elliptical Projection,” an improvement on the classic Mercator Projection that attempted to resolve that old problem of Greeland looking stupidly gigantic]

By the time our museum globe was built in the late ‘30s, Denoyer-Geppert had topped $600,000 in annual sales, with distribution all over the proverbial globe. They’d also expanded the Ravenswood plant to include a couple additional buildings stretching three blocks from Foster Avenue to Summerdale. By the time of Denoyer’s death in 1964, sales had reached the $6 million mark, and half of Andersonville seemed to be employed at or indirectly benefiting from the plant’s success.

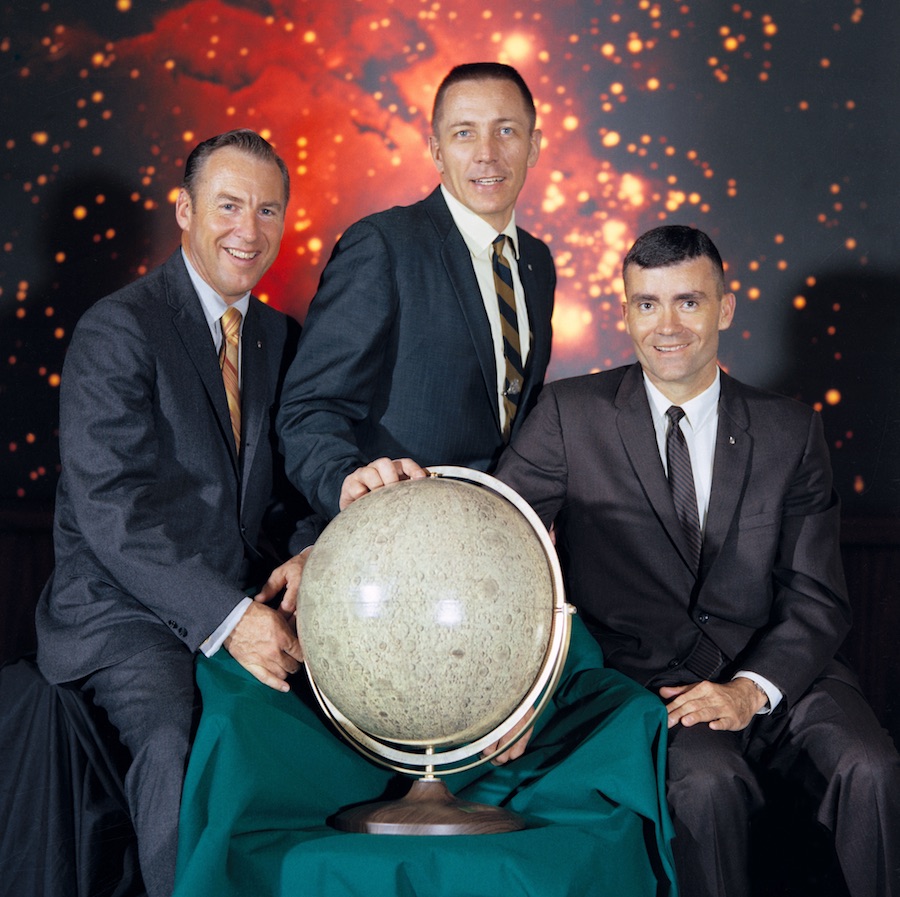

In 1967, with an elderly Otto Geppert as president, the company was purchased by the Times Mirror media conglomerate, but the Ravenswood plant continued to run independently. One of the firm’s great moments came two years later, when Denoyer-Geppert was contracted by NASA to build the first official and accurate “moon globe,” based on footage and photographs from the Apollo 10 mission. The company made 200 of the commemorative lunar globes, the first of which was presented to President Nixon by the actual Apollo 10 crewmen. A year later, the Apollo 13 crew posed with one of the globes before embarking on their fateful mission.

[The astronauts of Apollo 13 posing with the Denoyer-Geppert Lunar Globe in 1970, before Houston had a problem]

[The astronauts of Apollo 13 posing with the Denoyer-Geppert Lunar Globe in 1970, before Houston had a problem]

Sadly, 1970 also marked the death of Otto Geppert at the of age 80. He’d suffered a heart attack shortly after a minor car accident in suburban Wilmette. A gradual decline was underway for the company.

After the Rand McNally buyout in the 1980s, Denoyer-Geppert left its Ravenswood plant behind, bringing an end to a local Edgewater institution. More than 40% of the company’s employees had made their homes in the Andersonville area and simply walked to work each day, creating a true community atmosphere. These days there is really no manufacturing to speak of in the Edgewater / Uptown / Rogers Park area.

The map factory sat empty for years afterward, but after attaining historic landmark status, it met the inevitable fate of every great industrial building that isn’t leveled . . . it’s now loft spaces! The “Map Factory Lofts,” to be specific.

[Kudos to the owners of the “Map Factory Lofts” for honoring the building’s history by hanging original Denoyer-Geppert maps in the lobby. PS, I totally trespassed into the building to snap these photos.]

[Kudos to the owners of the “Map Factory Lofts” for honoring the building’s history by hanging original Denoyer-Geppert maps in the lobby. PS, I totally trespassed into the building to snap these photos.]

Denoyer-Geppert’s legacy—besides building a 100-year old business and a cool future apartment complex—was their shared belief that a successful map wasn’t merely one that sold well, but one that advanced the study of the world.

“It is surprising how much can be learned from a globe if it is understood,” Denoyer wrote. “At first children learn to read, later they read to learn. It is thus with the globe. Its wealth of information lies hidden until we learn to read its distinctive language. Then, generally to our surprise, it reveals a vast amount of information both factual and casual.”

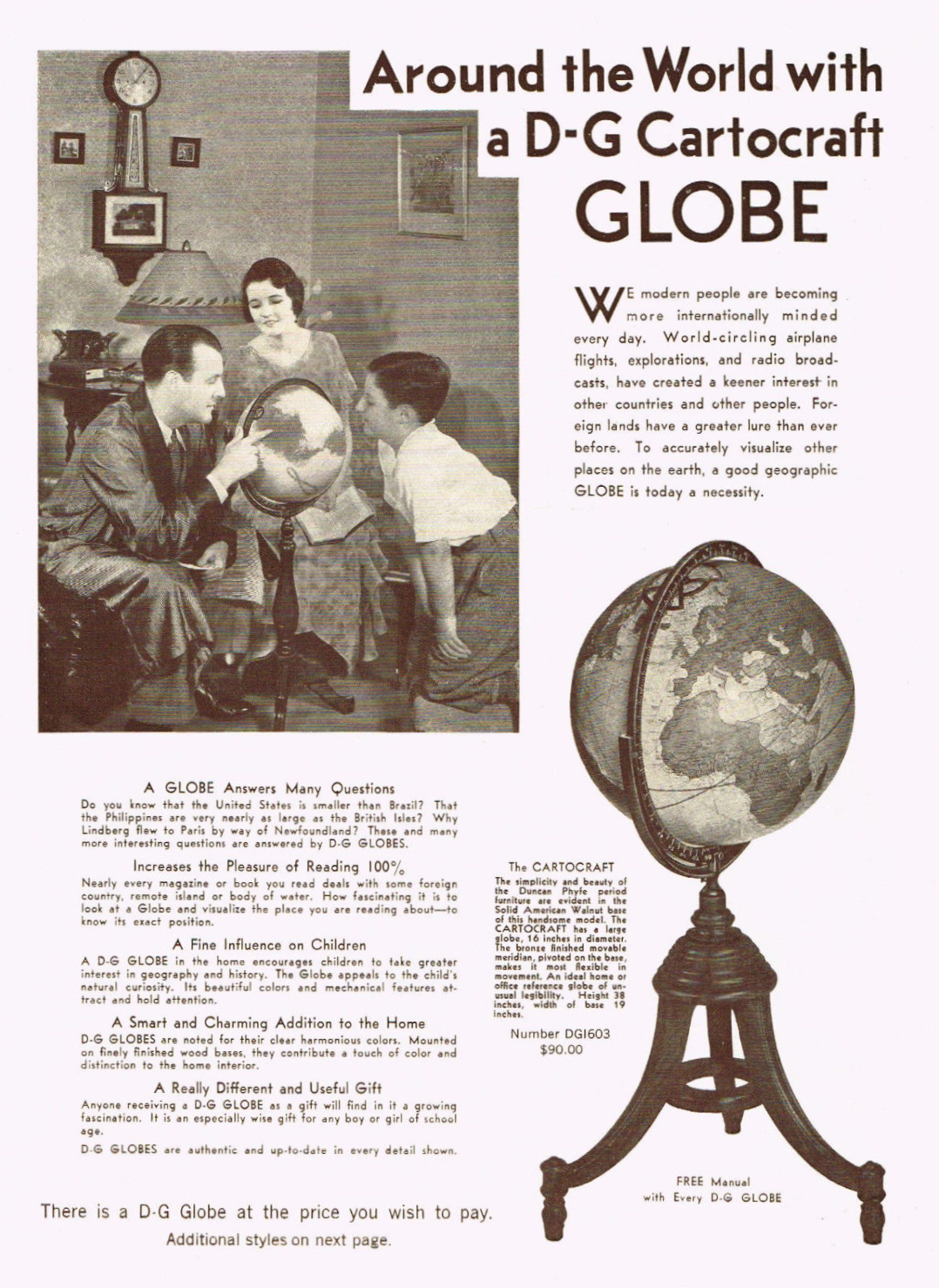

[Catalog page from 1933]

[Catalog page from 1933]

[Magazine ad from 1966, noting Geppert’s 50th year with the company]

[Magazine ad from 1966, noting Geppert’s 50th year with the company]

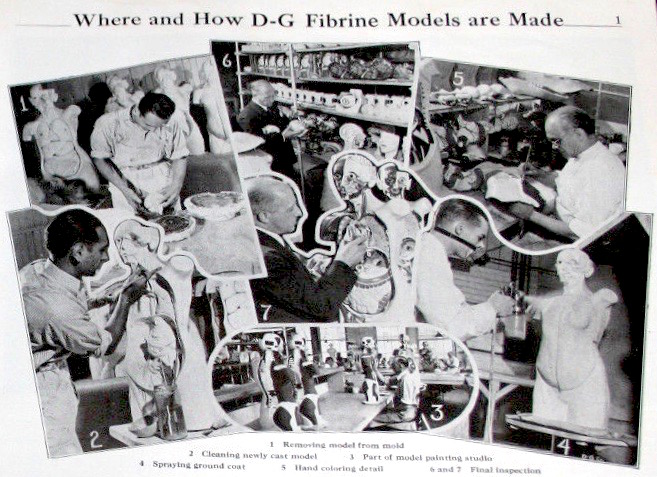

[Anatomical models were part of the Denoyer-Geppert business from early on . . . ]

[Anatomical models were part of the Denoyer-Geppert business from early on . . . ]

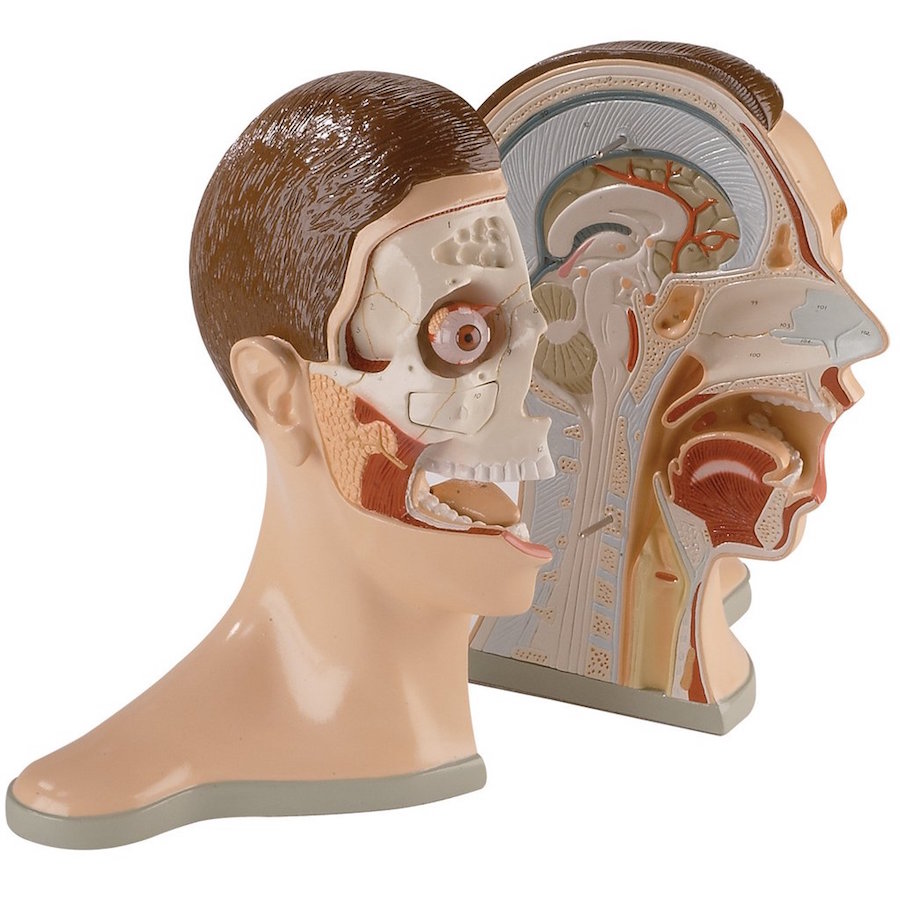

[And this is the kind of stuff today’s “Denoyer-Geppert Science Co.” specializes in at its Skokie plant. Not freaky at all.]

[And this is the kind of stuff today’s “Denoyer-Geppert Science Co.” specializes in at its Skokie plant. Not freaky at all.]

[More looks inside the old factory, aka the “Map Factory Lofts,” 5235 N. Ravenswood Ave.]

[More looks inside the old factory, aka the “Map Factory Lofts,” 5235 N. Ravenswood Ave.]

Sources:

Encyclopedia of American Biography, New Series, Vol. 9, edited by Winfield Scott Downs

A Teacher’s Manual Accompanying Cartocraft Globes, by L.P. Denoyer, 1931

“You Need a New Map” by Otto E. Geppert, The Rotarian, Dec. 1942

CrayonCollecting.com – “Denoyer Geppert”

National Register of Historic Places – Swedish American Telephone Building, 1985

Redfin.com: 5235 N Ravenswood Apartments

Archived Reader Comments:

“i came across a set of Abraham Lincoln prints with the D-G label on the back. Looks like they are mounted on thick cardboard? Did the company provide historical art for classrooms? Not sure where my father in law came to have them in his possession! they are from the artist Louis Bonhojo, was trying to find some info on them… ” —Sandy, 2019

” —Sandy, 2019

“Does anybody know where I can find Tim Baldwin, a former VP with Denoyer-Geppert in the early 1980s? Thanks in advance!” —Terry Mueller, 2019

“D-G actually had three buildings on Ravenswood. I used to walk by it all the time & there was always a Visible Woman model in one of the windows.” —Becca, 2018

“I toured there about 1957 as part of my Boy Scout troop. The globes were impressive but the strongest memory is assembling demonstration skeletons for classrooms out of real human bones shipped in from India.” —Tom F., 2018

“We – Denoyer-Geppert still cast and paint our models by hand – give us a call for a tour. Our business motto is Sharing The Knowledge” —Mary Andros, President Denoyer-Geppert Science Co., 2017

847-965-9600 www.denoyer.com

“Lovely! My husband’s grandfather–Keith Olson–worked for Denoyer-Geppert in Chicago, and had many stories to tell of his time there. He invented and patented the “Vanguard Satellite Demonstrator” mount for D-G, and was involved in the lunar globe. A prolific inventor and a pretty cool guy. Nice post!” —JMOChicago, 2017

My mom worked at Denoyer-Geppert in the mid-1950s. She would take the “L” train down from Wilmette. She used to tell me how she painted anatomical models. She studied at the American Academy of Arts and the Art Institute before getting her first job at D-G. She really liked it.

I just researched a biology set that I own that were sold and mounted by Denoyer-Geppert Company. I cherish them. They are linen lithographs by Jung, Koch & Quentell. They are likely biology maps. I have a set of 10 in the original oak frame. What’s amazing is they survived in the old school. I have owned them for over 40 years. They still have the chalk arrows and numbers that were used for a lab practical.