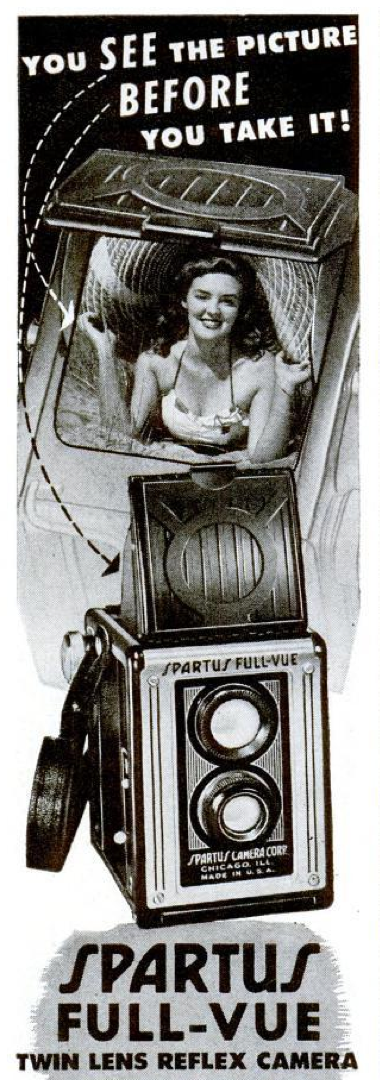

Museum Artifact: Spartus Full-Vue Camera, 1940s

Made By: Spartus Camera Corp. / Galter MFG Co. / Utility MFG Co. / Monarch MFG Co., 711 W. Lake St., Chicago, IL [West Loop]

In 1953, a Chicago business owner submitted an application to the U.S. Trademark Association for a new line of cigarette lighters he’d developed. All the paperwork seemed in order at first, until reviewers saw the actual name the applicant wanted to register for his product… “Kodak.”

At that point in history, New York’s Eastman Kodak Company had already been the most famous name in camera and film equipment for half a century. So what exactly was this Chicago man thinking trying to slap their name on a cigarette lighter? Was he a fool? A jokester?

Nope, none of the above. The man in question was actually Jack Galter—president of Spartus Corp.—and he was merely doing the same thing he’d been doing for 20 years: artfully gaming the system.

Among all the many brilliant entrepreneurs profiled in the virtual halls of the Made-in-Chicago Museum, it’s hard to say any could challenge Mr. Galter when it came to relentless, shameless ingenuity. His inventiveness started with actual product designs and gadgets, but advanced quickly into the boardroom, where his ability to bend the marketplace to his will eventually turned him into one of the richest—and notably, most charitable—men in the city.

Galter didn’t always earn everybody’s respect. In the case of the Kodak incident, the Examiner-in-Chief of the Trademark Assoc. not only rejected the application, but made it known he wasn’t amused by the stunt:

“It is seldom that a newcomer attempts to bodily adopt an arbitrary and coined trade-mark as well-known and as well-advertised as the one in issue. …It is difficult to find any reason in this case for applicant wanting to copy the name ‘Kodak’ except the desire to profit from another’s good will.”

Profit from another’s good will, or… profit from an archaic system of trademark and copyright laws—whichever phrasing you prefer.

In truth, Galter knew it was virtually impossible that he’d be permitted to commandeer a name like Kodak. His goal, however—like a clever velociraptor—was to test the trademark office for weaknesses, as he’d done many times before. Throughout his career, Galter had masterfully and unapologetically experimented with the boundaries of branding, going all the way back to the 1930s. By using a familiar name on a wholly unrelated type of product, for example, he’d found that trademark disputes could sometimes be averted, while the benefits of consumer brand recognition could be achieved. These were choppy waters to navigate, and Galter was certainly thrown overboard a few times, but his monumental success—first in manufacturing and later in real estate—prove he generally got the last laugh when it came to a battle of wits.

In truth, Galter knew it was virtually impossible that he’d be permitted to commandeer a name like Kodak. His goal, however—like a clever velociraptor—was to test the trademark office for weaknesses, as he’d done many times before. Throughout his career, Galter had masterfully and unapologetically experimented with the boundaries of branding, going all the way back to the 1930s. By using a familiar name on a wholly unrelated type of product, for example, he’d found that trademark disputes could sometimes be averted, while the benefits of consumer brand recognition could be achieved. These were choppy waters to navigate, and Galter was certainly thrown overboard a few times, but his monumental success—first in manufacturing and later in real estate—prove he generally got the last laugh when it came to a battle of wits.

Born in Russia in 1904, Galter was still a child when his family fled for America—one of the many Jewish families arriving in Chicago looking for a new start. In his youth, he became interested in music, and spent much of the 1920s as a wunderkind jazz drummer on the Chicago speakeasy circuit—rubbing shoulders with gangsters, rum runners, dirty City Hall deal-makers, ladies of the night, and fat cat industrialists. Actually, he mostly played in perfectly proper dance halls. But according to a 1992 interview that an elderly Jack and his wife Dollie conducted with the Chicago Jewish History newsletter, he did indeed play shows for Al Capone, and even drummed alongside a very young, soon-to-be jazz legend, Benny Goodman.

“Benny Goodman started with us,” recalled Dollie, who began dating Jack when they were still teenagers. “[Goodman] was 14 and we were 19 [her math checks out, by the way]. And we used to pick him up after school. We played mostly on the north shore and the train would take us—if the cars held up—we’d get there… the programs would start at 8. And then Benny would fall asleep. The boys used to carry him upstairs and put him to bed.”

While Goodman went on to become the King of Swing, however, Jack Galter was more of a hired gun, never quite advancing to celebrity status on the big band scene. According to Dollie, the couple only had $100 and a car to their name when they got married in 1925. When the Depression hit a few years later, Galter’s drumming was barely supporting their new family. He started to consider a new career track.

Though his profession was still listed as “musician in an orchestra” in the 1930 census, Jack Galter was now an apprentice of sorts to his father-in-law—an inventor and experienced businessman named Henry T. Schiff. If by any chance you’ve read our page on the Electric Clock Corporation of America, that name should ring familiar.

Like Jack, Henry Schiff was a first-generation Jewish immigrant from Russia, and he became a massive influence on his impressionable mentee / son-in-law. Many years later, in 1992, Jack Galter would remember him as a “fascinating man” and a “fantastic operator.”

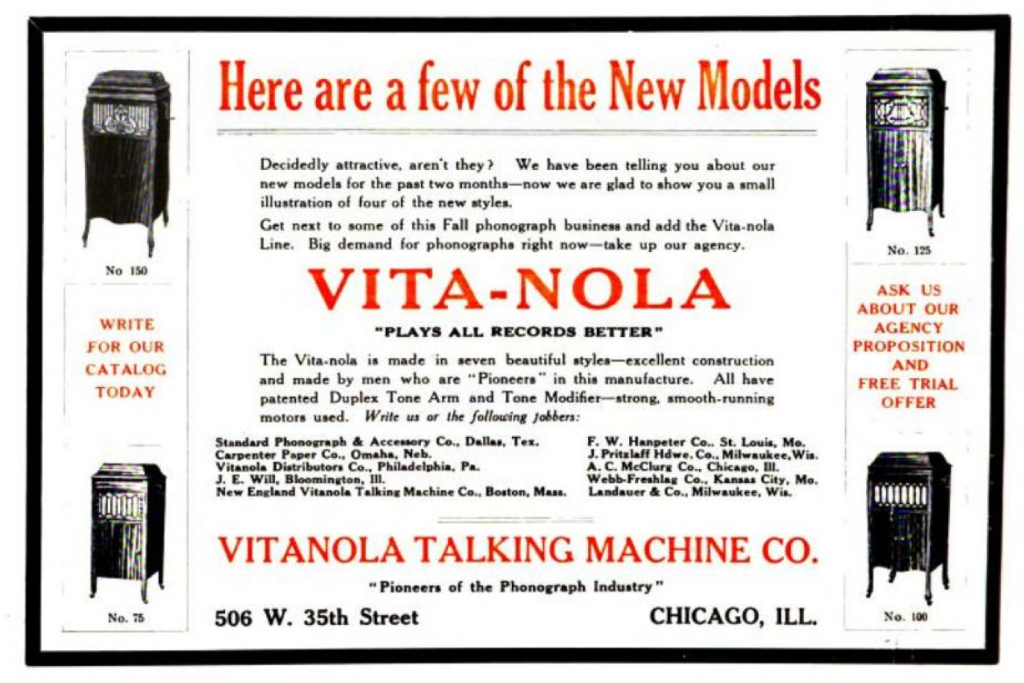

Around the turn of the century, Schiff had started working in the field of phonographs, and eventually launched his own company in Chicago, the Vitanola Talking Machine Company. He had intentionally chosen a name that was similar-sounding to the well-established Victrola machines made by the Victor Talking Machine Company. This sneaky move made Schiff some enemies in the industry, but it also helped him gain a foothold in a very competitive marketplace. “You can go a long way with a name,” he theoretically told Galter, and that lesson stuck.

[A magazine ad for the Vitanola Talking Machine Co. from 1917]

[A magazine ad for the Vitanola Talking Machine Co. from 1917]

Henry Schiff gave up the phonograph trade by the 1930s, and was working on his electric clock business, among a pile of other fly-by-night ventures. He was sued by the Hammond Clock Company in 1934 for patent infringement, and was challenged in court over several trademark disputes, as well, thanks to his use of eyebrow-raising company names like Luckey Strike MFG. Co., Motor Engineering Company, Match King, Inc., Shavemaster, Inc., and Elgin Laboratories. Even Henry’s daughter had been born “Sarah Miriam Schiff” before becoming “Dollie.” Names were simply strategic and negotiable in this family.

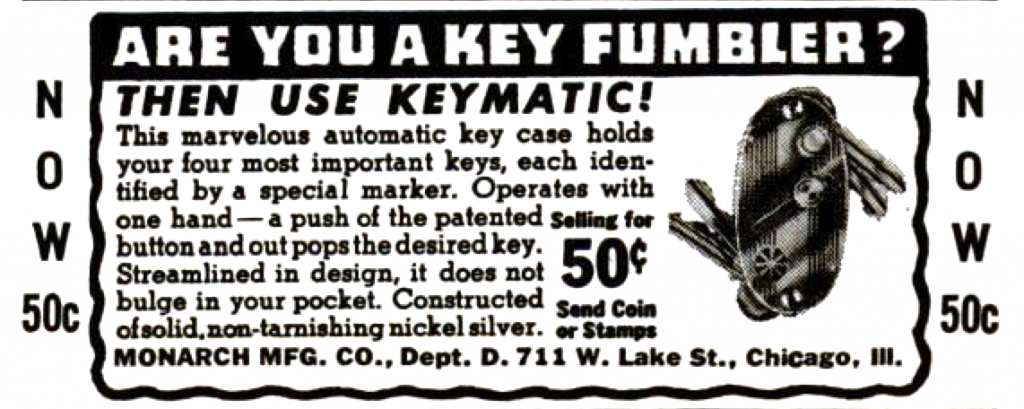

On that front, young Jack Galter was clearly drinking the kool-aid, too. By this point, he was getting into the manufacturing biz himself, emulating old Pa Schiff every step of the way. That included building cheap clocks and razors and experimenting with brand identity. Some of his earliest production in Chicago was done under the banner of the Monarch Manufacturing Co. (sometimes spelled Monarck, sometimes Monark)—through which he developed a key holder of his own design, along with cigarette lighters, irons, electric razors, and other low-cost goods for the average Joe. Some of those products, in turn, had subsidiary manufacturing and brand names of their own, including “Spartus.”

A complicated web was being spun from day one.

[The Keymatic, one of Jack Galter’s early products with the Monarch MFG Co, in an ad from 1939]

[The Keymatic, one of Jack Galter’s early products with the Monarch MFG Co, in an ad from 1939]

Around 1938, Galter caught wind of some new trends in the camera market—a longtime personal area of interest. As an alternative to expensive cameras from the aforementioned Kodak, some companies were starting to roll out miniature, click-and-go bakelite cameras designed for use with 127mm film. They took low-quality pictures, but pictures nonetheless, and retailers could sell them for less than $5, making them good starter cameras for kids. Galter, the retired drummer, understood the show business concept of giving the people what they wanted, and in the cheap plastic camera market, he saw a new goldmine.

Gradually expanding his factory space at 711-715 W. Lake Street [former home of the Randolph Radio Corp], Galter went to work developing his own line of bakelite mini-cameras, while also buying out the rights to existing designs. There were a handful of simple, identifiable molds he used throughout the late ‘30s and early ‘40s, but rather than just putting the Monarch or Spartus name on all the name plates for maximum brand recognition, he negotiated with distributors to customize lens plates with dozens of different manufacturer AND brand names.

In some cases, Galter partnered with other Chicago companies, like Henry Schiff’s Elgin Laboratories (soon to be sued by the Elgin National Watch Company). In other cases, brand names were simply random aliases of Spartus/Monarch/Galter.

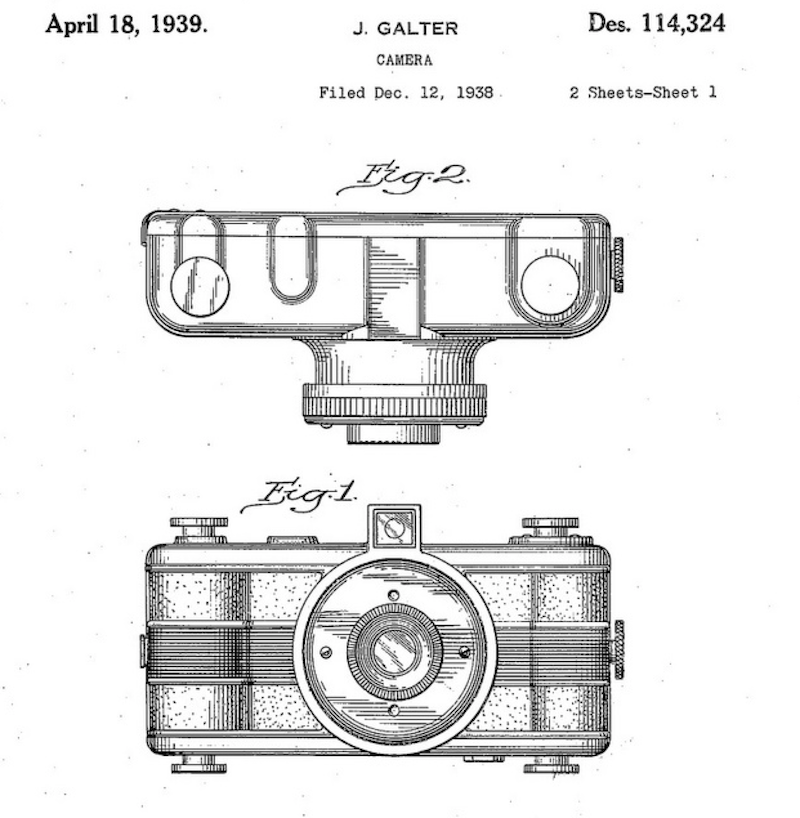

[One of the generic mini camera molds Galter patented, dated April 18, 1939]

[One of the generic mini camera molds Galter patented, dated April 18, 1939]

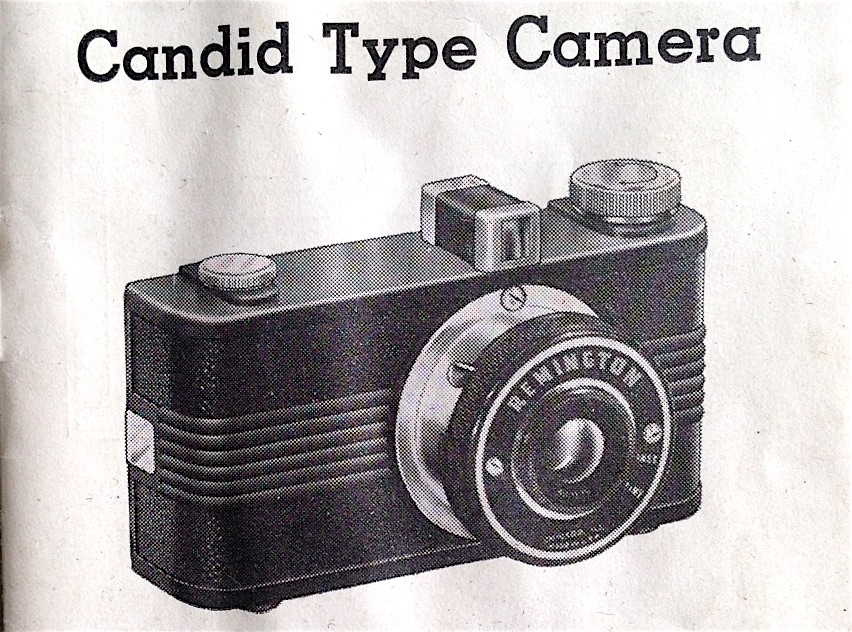

There was truly no rhyme or reason as to which mini camera molds received which branding. Two people could buy the exact same camera type, made in the same Lake Street factory, and one would say it was a “Candex” made by the “General Products Co.,” while another would call itself a “Remington” made by “DeLuxe Products Co.” For added confusion, at some point near the start of World War II, Galter seemingly absorbed what was then the fourth largest camera manufacturer in the country, New York’s Utility Manufacturing Company. Known for its “Falcon” brand, Utility had been using some of Jack Galter’s rangefinder camera patents from 1938-1940. As to whether Galter finally overtook them through legal action, a buyout, or a merger, I do not know. But by the early ’40s, the Utility MFG Co. was just another subsidiary of Galter’s Spartus empire.

By stockpiling loads of brand names, the goal, perhaps, was to create the illusion of variety in the marketplace. When you’re selling a cheap product, it’s also sometimes wise to give it many names, thus making it harder for a bad reputation to stick. But in Galter’s case, there was more to it than that.

[Pictured: The Utility MFG Co. of New York manufactured its own view-finder box camera, the Falcon Magni-Vue, before suddenly becoming the Utility MFG Co. of Chicago in the early ’40s]

[Pictured: The Utility MFG Co. of New York manufactured its own view-finder box camera, the Falcon Magni-Vue, before suddenly becoming the Utility MFG Co. of Chicago in the early ’40s]

In the film Spartacus, all the freed slaves proudly proclaim “I am Spartacus” to show solidarity with their liberator. In the Spartus factory, meanwhile, all the cameras pretended to be something other than Spartus. It was innocent fun, maybe, but much like trying to use the name “Kodak” 15 years later, Jack Galter’s strategy wasn’t necessarily about variety so much as it was about blatant identity theft.

In 1941, following in his father-in-law’s tradition, Galter was finally hit with a cease and desist order from the Federal Trade Commission, primarily due to complaints about his use of three particular trademarks: “Remington,” “Underwood,” and “Elgin.” By now, the well-known Elgin Watch Company of Illinois had already defeated Jack’s father-in-law in court and was looking for more blood. Remington and Underwood, meanwhile, were both established typewriter companies that had caught wind of some guy in Chicago slapping their names on cheap knick-knacks. Galter, quite obviously, had put “Underwood” on an electric razor and “Remington” and “Elgin” on mini-cameras in a ploy to convince customers—perhaps even subconsciously—that they were buying a product from a familiar, trusted manufacturer. . . rather than from some guy in Chicago.

Galter’s accusers pointed to the principle of “trademark dilution,” the concept that “the uniqueness of a trade-mark may be impaired as a result of trademark use by others of the same mark on totally unrelated goods.”

According to documents from the U.S. Court of Appeals Seventh Circuit, this case against Galter was “not an action for trademark violation, but a proceeding to protect the public against fraud and deception. The evidence taken in the companion proceeding did not disclose any right in petitioners to use the names “Elgin,” “Remington” and “Underwood” in such a manner as to mislead the public into believing that petitioners’ products were the products of the Elgin, Remington or Underwood Corporations.”

Galter, meanwhile, never had enough invested in any of his poached trademarks to care too much if they eventually got policed and shut down. It was always a worthy risk, and a practice he could routinely plead innocence on. Because some trademarked words unavoidably pass so far into the common language that they become impossible to own (such as B.F. Goodrich’s “Zipper”), Jack Galter believed there was always another loophole or temporary route available to play the branding game. At least, that’s my interpretation of the guy’s motives.

It’s worth noting that, at the time this was all happening, the general public wasn’t really aware—and/or didn’t care—that all these different cameras were coming from the same place. It’s only been in more recent years that camera collecting junkies have come to identify the so-called “Chicago Cluster” emanating from 711 W. Lake Street.

The Made-in-Chicago Museum has its own pretty substantial collection of mini cameras from the Chicago Cluster [pictured above] which you can check out on our comprehensive Spartus Corp. Cluster page. Some of the Lake Street bakelites we’ve managed to acquire include names like the Acro-Flash, Metro-Cam, Clix, Fleetwood, and Falcon, with company names ranging from the original Monarch MFG Co. to the Rolls Camera MFG Co., The Camera Man, Metropolitan Industries, Elgin Laboratories, and Herold MFG Co., among others.

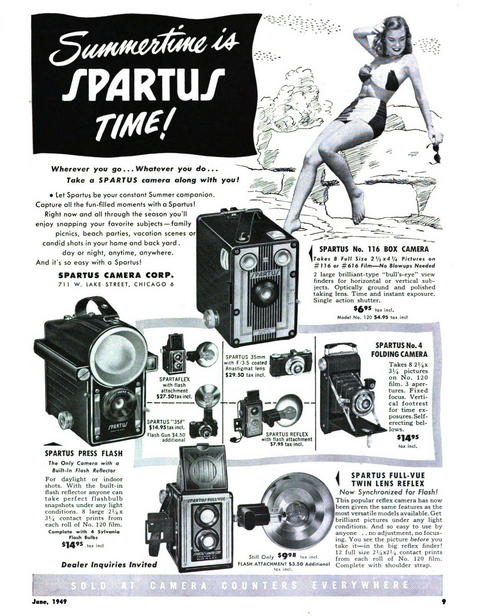

As for the camera featured on this page—the Spartus Full-Vue box camera—it was introduced about 10 years into the company’s existence, in the late ‘40s. Jack Galter had shut down the Monarch MFG Co. during World War II, and his main focus shifted to Spartus brand products, which—for some god forsaken reason—were initially advertised under the banner of “The Spencer Company.” Finally, in 1948, right around the time our Full-Vue camera was making its debut, Galter dropped the Spencer name and changed the camera manufacturing wing of his empire to the “Spartus Camera Corporation.”

The Spartus Full-Vue—which it won’t surprise you to know was an intentional ripoff of an existing British twin-lens reflex camera called the Ensign Ful-Vue—is made of bakelite just like the original Spartus minis. It can use any standard 120mm film, and produces 6×6 square images. The lens is fixed focus and aperture, and there is a rotary shutter with a side-mounted release. The exposure is made by gently holding down the little exposure lever. A big cumbersome flash attachment was sold separately (we don’t have one). Generally, you could buy a Full-Vue on its own, without the flash, for about 10 bucks.

[Peering down into the top viewfinder of our Spartus Full-Vue, toward Lake Michigan]

[Peering down into the top viewfinder of our Spartus Full-Vue, toward Lake Michigan]

To help promote the Full-Vue, Jack Galter actually penned a full-page article in a 1949 issue of U.S. Camera magazine, titled “How to Use a Box Camera.” In it, he wrote: “Everyone knows, but too few will admit, that fine pictures can be made with the simplest of all cameras—the box camera.”

And would you believe it, 70 years later, there is a Flickr group for people still taking “fine pictures” (a subjective concept) with this very same camera: Spartus Full-Vue Flickr Group.

And would you believe it, 70 years later, there is a Flickr group for people still taking “fine pictures” (a subjective concept) with this very same camera: Spartus Full-Vue Flickr Group.

The Full-Vue was manufactured throughout the 1950s, but our model dates from probably 1949ish. We know this because it still says Spartus Camera Corp. on the label. When Jack Galter sold the daily operations of the company to his sales manager Harold Rubin in 1951, Rubin briefly changed the company’s name, yet again, to Herold Products Co. (yes Herold, even though his name was Harold). Rubin continued to sell Spartus brand cameras, but they featured Herold labeling… until the company went back to being the Spartus Corp. a few years later.

I know, it’s all absurd. But you can’t really question the results.

By the late 1950s, Jack Galter was still very much involved in Spartus as its Chairman, and he had factories in several other cities, with the “Galter Products Co.” joining his legion of company identities. He and his wife Dollie Galter also started funneling a lot of their cheap gadget income into the real estate market, where they made an even bigger fortune.

From there, to their absolute credit, they became and remained beloved pillars of the community for decades, giving huge sums of money—$100 million across their lifetimes—to charities, primarily hospitals. In Chicago, both the Northwestern Memorial Hospital and the Swedish Covenant Hospital have pavilions named in Jack and Dollie’s honor.

From there, to their absolute credit, they became and remained beloved pillars of the community for decades, giving huge sums of money—$100 million across their lifetimes—to charities, primarily hospitals. In Chicago, both the Northwestern Memorial Hospital and the Swedish Covenant Hospital have pavilions named in Jack and Dollie’s honor.

Sometimes the ends justify the means, and in the grand scheme of things, if calling a cigarette lighter a “Kodak” could eventually result in a cancer patient getting better treatment, maybe it’s not such a shady bit of business, after all.

Sources:

Galter vs. Federal Trade Commission

California Law Review: Trademark Dilution

Camera Wiki: The Chicago Cluster

Chicago Jewish History, XVI, 1992

i have 2 Spartus co\Flash cameras in boxes is there any value in these cameras

Have a Spartus Press Flash with a small light bulb on the side of the camera. Whenwas it made and what was the small bulb for?

The tape note on your camera- “…used by the Grimes’s in the 1950’s – SURELY

Not the Grimes sisters!? Any info on that note?

Unfortunately no info. The camera was purchased at a flea market in Uptown in 2015, with no explanation as to the taped-on label. It certainly is plausible that it could be connected to the Grimes family, since there seems to be few reasons to write a label like that, in past tense, in any other context. The time period lines up, too. We just don’t have any solid way to prove it, unless a reader can somehow confirm it.

I had purchased one Spartus Folding Camera, image size 1 5/8x 2 1/2, film 127 model S-500. It is with its original card board box. I have used it in the past, it is a good camera and am proud to possess it. The aesthetic look is the same , the plating is good even after so many years. This company’s products are good and long lasting, giving value to the money spent.