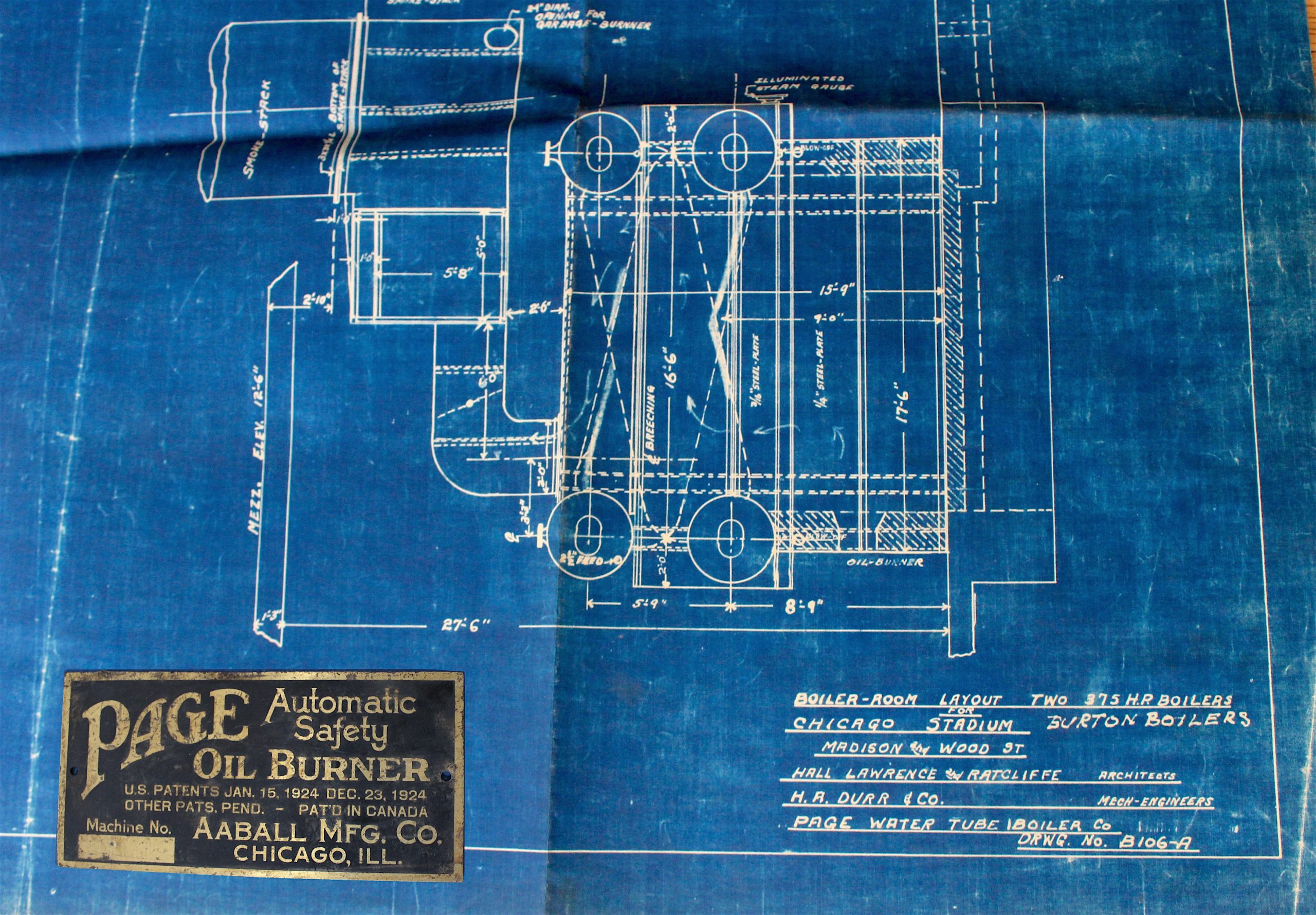

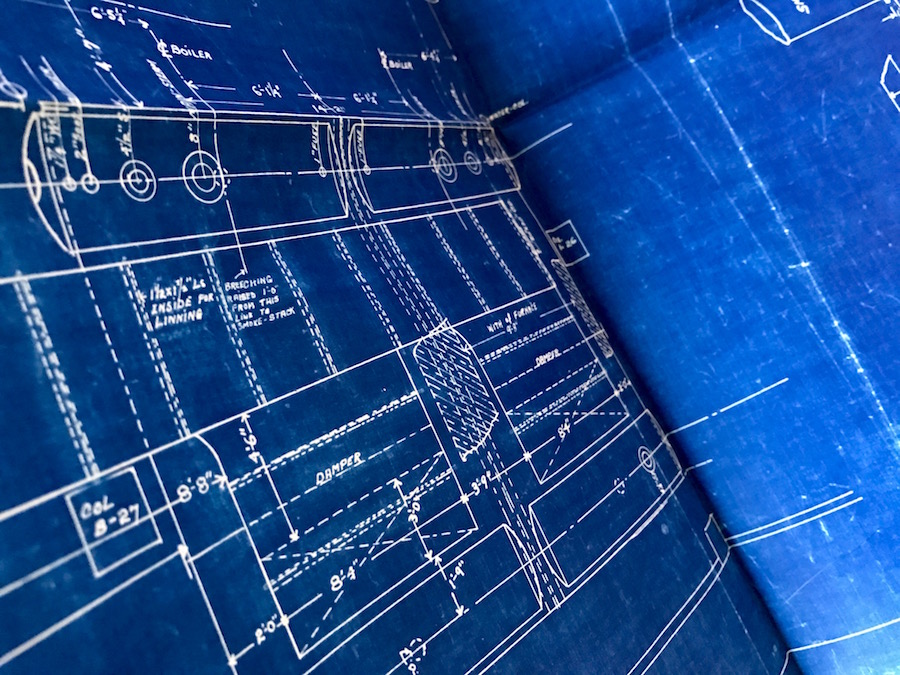

Museum Artifact: Chicago Stadium Boiler Room Blueprint, c. 1940s

Made By: Page Boiler Company, 815-819 W. Webster Avenue, Chicago, IL [Lincoln Park]

In 2015, the Page Boiler Company shut down its last Chicago plant at 2348 N. Damen Avenue in Bucktown, and I guess I can say I attended the funeral.

After 110 years of designing, building, installing and repairing the finest water-tube boilers in the Midwest, you’d think a proper farewell concert—or at least an emotional video montage—would be in order. Instead, the occasion was marked with a rather haphazard “going out of business sale” inside the stark remains of the gutted Page industrial space. Decades worth of old tools and equipment, furniture, photographs, office junk, and odds-and-ends were strewn about for the public to pick over; sans rhyme or reason.

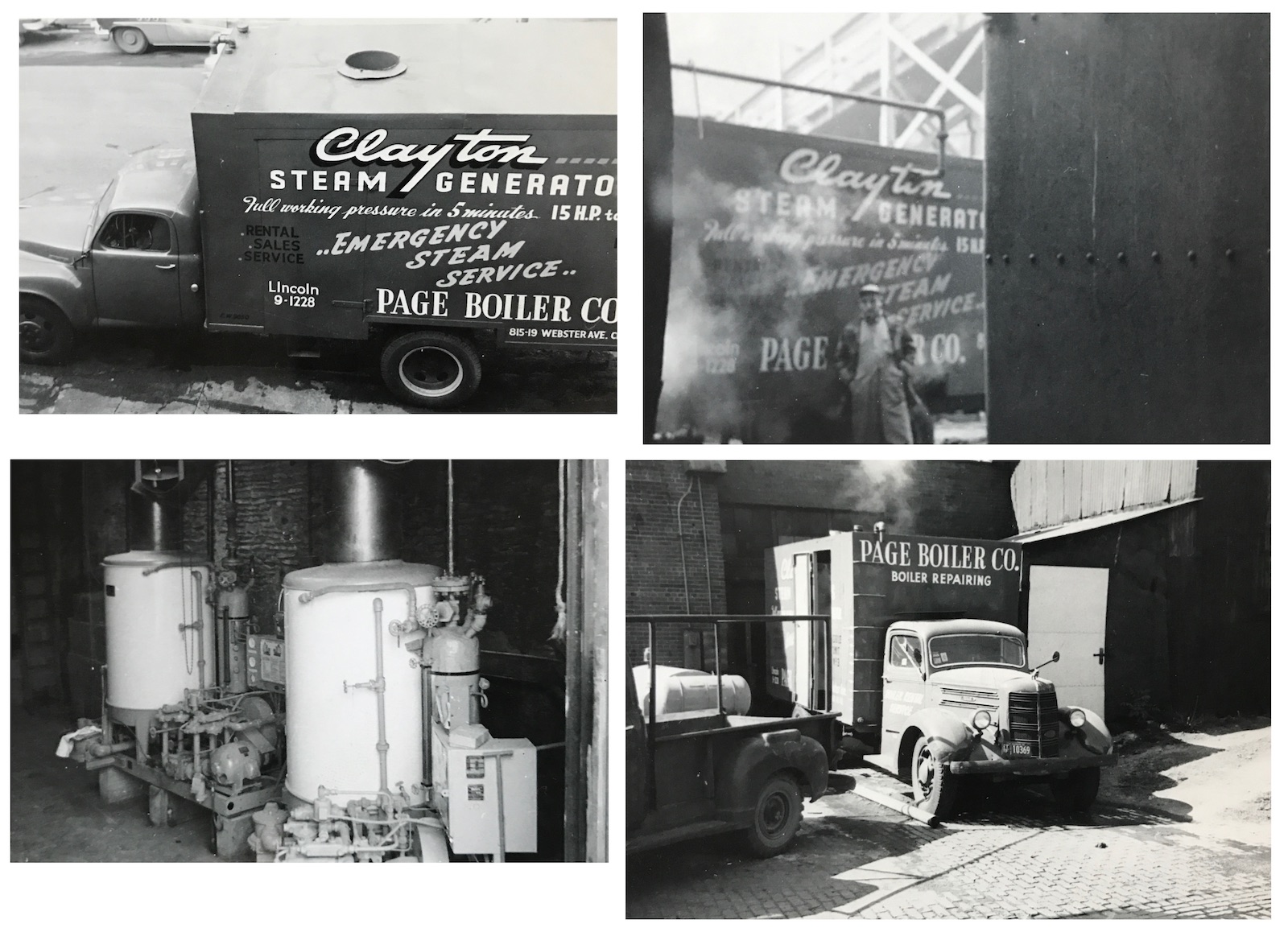

[Page Boiler Co. truck photographs from the early 1960s]

[Page Boiler Co. truck photographs from the early 1960s]

When I strolled into this scene on a cold grey Friday, there were maybe three other zombie pickers wandering through the wreckage. Soon enough, our fingertips were black with dust like we’d been booked down at the precinct. I was surrounded by tangible abandonment and the musty aroma of a carefree boilerhood long forgotten.

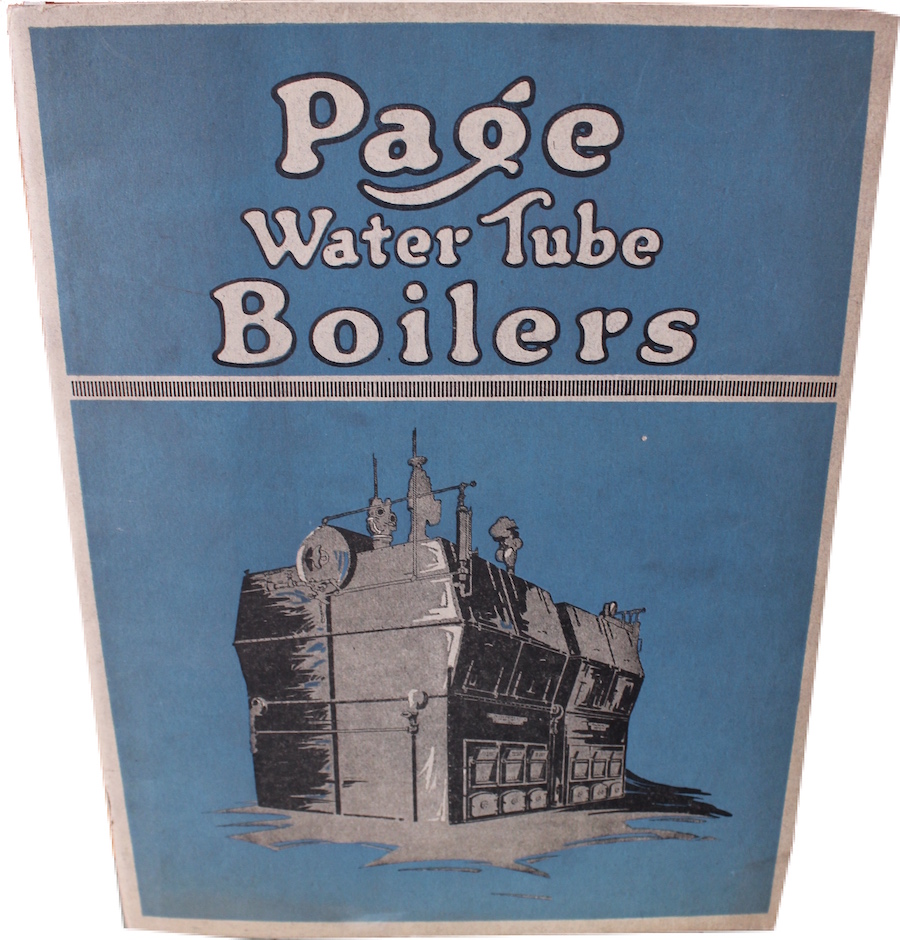

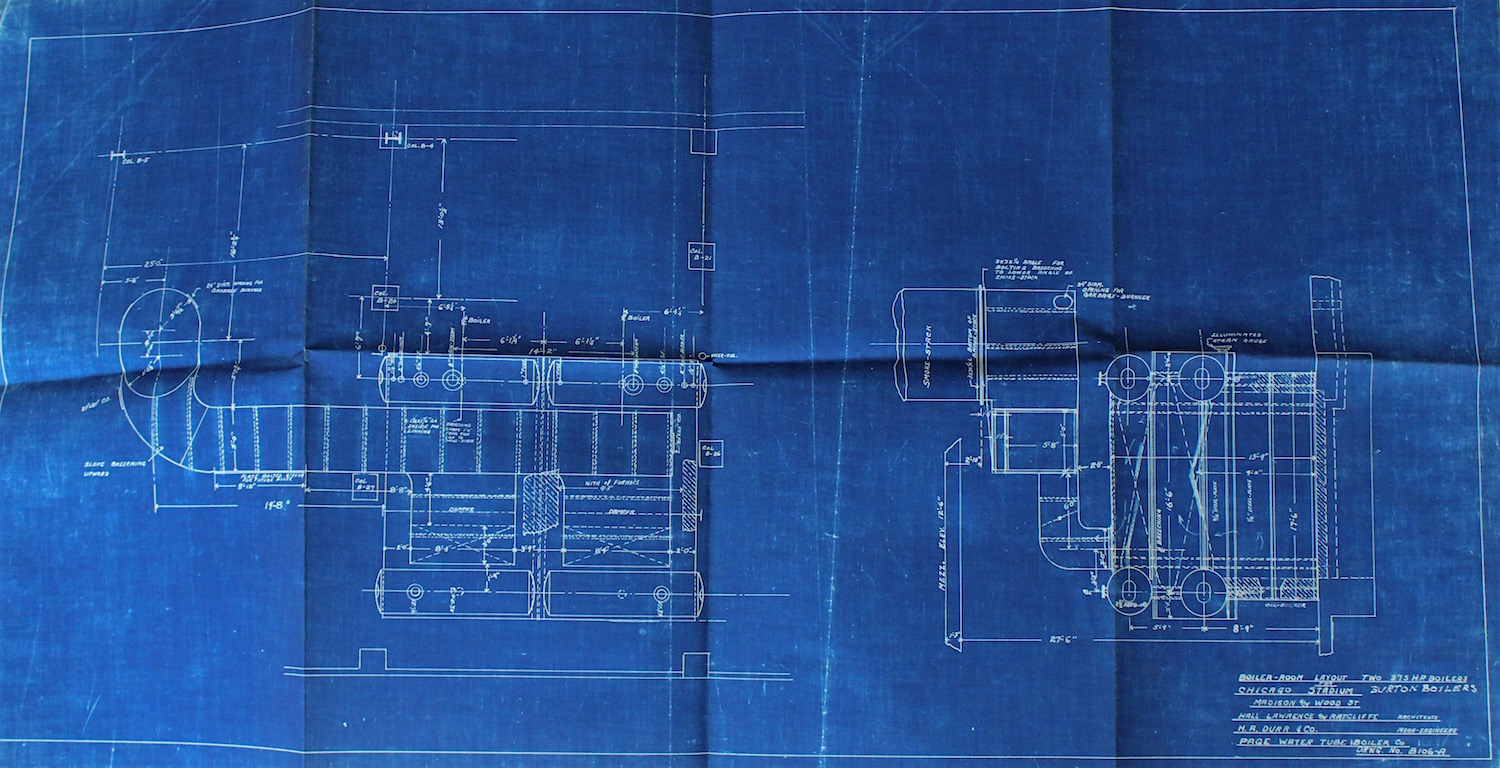

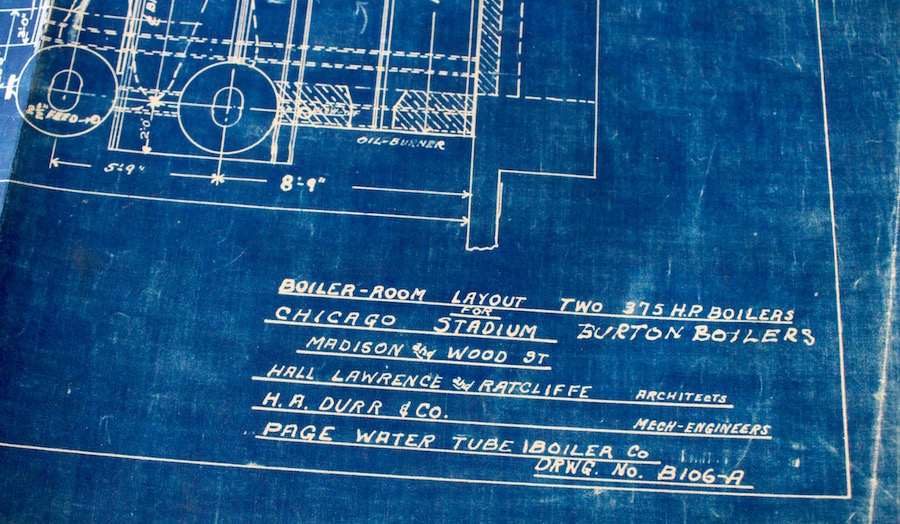

One box had a few pristine Page Boiler catalogs from the 1920s, another contained mid-century blueprints of the company’s work for some familiar clients—Kraft Cheese, the A.B. Dick Company, and—oh, hey—the long lost Chicago Stadium! There was a shelf filled with Turner Brass torches and a shadowy corner occupied by an army of industrial vacuum cleaners.

One box had a few pristine Page Boiler catalogs from the 1920s, another contained mid-century blueprints of the company’s work for some familiar clients—Kraft Cheese, the A.B. Dick Company, and—oh, hey—the long lost Chicago Stadium! There was a shelf filled with Turner Brass torches and a shadowy corner occupied by an army of industrial vacuum cleaners.

Somebody or somebodies at Page Boiler clearly made a concerted effort to keep the company’s long history contained, if not entirely “maintained,” over the years. All of these things could easily have been thrown away or incinerated at one opportunity or another, particularly when Page moved from Larrabee Street to Webster Avenue in the 1930s or from Webster to Damen in the 1990s. But here they were; random snapshots of a century’s worth of work—dusty but golden.

Chicago’s Page Boiler Company—not to be confused with the much older and larger Wm. H. Page Boiler Co. of New York—was incorporated by Milton E. Page, Jr. in 1905. Milton had grown up in a fairly affluent family, but circumstances had forced him to become a self-made man, nonetheless.

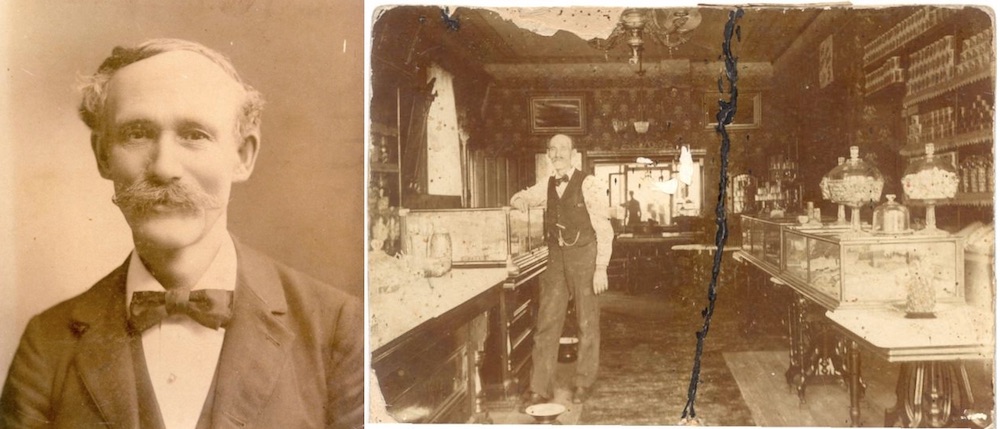

Milton’s grandpa, Samuel Page, was a very early settler to Chicago, bringing his family over from Maine in 1833 with a baby—Milton Page Sr.—in tow. Years later, shortly after the Civil War, Milton Sr. married Dora St. George, a sharp young lady who ran a thriving retail candy business from a shop at Clark Street and Monroe. Milton Jr. was born shortly thereafter, in 1869, presumably giving his dad an excuse to keep poor Dora back at home “with the kid” while he took over the confectionery enterprise for himself—as any good Victorian man would.

[Milton Edwin Page, Sr., in portrait, and manning the counter at the candy shop, c. 1880s]

[Milton Edwin Page, Sr., in portrait, and manning the counter at the candy shop, c. 1880s]

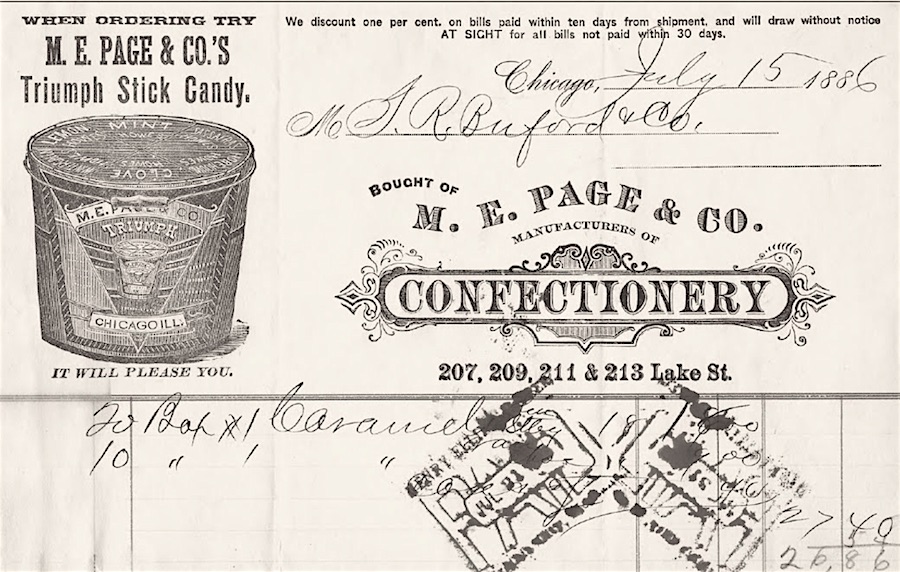

Partnering with a fella named Rufus P. Pattison, Milton Sr. launched M.E. Page & Co., officially beginning his career as a candyman. From the outset, Page’s confectionery delights were getting pretty good reviews, but—this being the 1800s and all— the company had the damndest time keeping its factories from erupting into flames. In 1871 alone, they lost their plant to a blaze in May, rebuilt it, then watched it go up again in the Great Fire a couple months later.

Things seemed to be on a much more solid foundation through the 1880s, as Milton E. Page & Co. had itself an established, sprawling factory home at 211 E. Lake Street and one of the fastest growing confection brands in the country—shipping its rock candy, stick candy, gums and other yums to as far off as Texas and California.

But the party was short-lived. Dora Page died in 1885, leaving Milton Jr. and four other children motherless. Then . . . wouldn’t ya know it? Another fire broke out at the Page factory. And this one was massive, completely destroying the plant and putting the Pages essentially back to square one.

Milton Sr. tried to reorganize the business as a stock company, but he also made some bad investments in desperate efforts to put his family back on track. Soon enough he gave up the fight entirely and moved to a farm in Alabama, marrying a woman 30 years his junior.

Toward the end of M.E. Page & Co., young Milton Jr. had come aboard to manage the machinery department at the candy plant. By 1893, though, he was freed from his father’s expectations and ready for a new start. “I’m trading in this bubblegum for boiler tubes!” he exclaimed.*

*Quote is inferred and may not be entirely historically accurate.

From the looks of things, the son actually took after his father in one respect—he used his wife’s connections to help him break into a new business. In that famous World’s Fair summer of 1893, 24 year-old Milton Page Jr. married a 21 year-old girl named Amalia Pfeiffer. Her father, as it happened, was Mr. Chris Pfeiffer of the Chris Pfeiffer Boiler Company.

Maybe Milton met his bride through his new boss rather than the other way around. Either way, he was in like flynn at the boiler plant.

Page reached the level of vice president at Pfeiffer and remained there through the turn of the century, learning the trade and making connections. The boiler room was not the sexy part of any new factory or arena, perhaps, but it was the engine of its power. It was a fast moving industry, too, with a consistent demand just as reliable as the candy trade. Milton was all-in.

He finally broke out on his own in 1904, naming himself president of the Page Boiler Company, a humble startup he literally ran out of a barn. Purely coincidentally (we hope), his wife Amalia died within a year of her husband leaving her father’s company. And Milton—like his own father—quickly remarried a much younger woman.

[The first major Page Boiler Co. plant at 815 Larrabee Street]

[The first major Page Boiler Co. plant at 815 Larrabee Street]

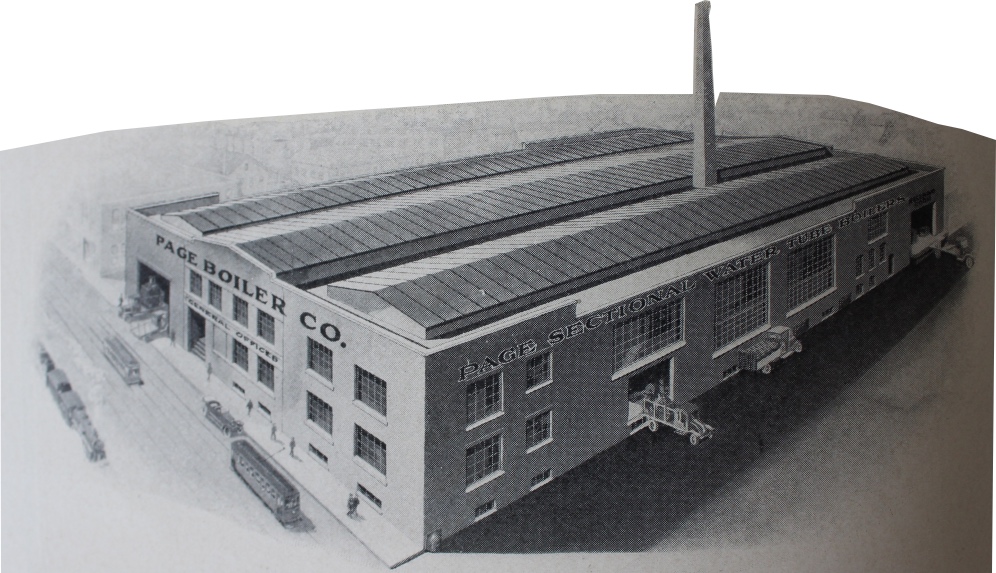

Setting to work with his right-hand men John and Adolph Johanson, Page hand-built the first series of Page boilers, slowly building up a reputation for quality that enabled him to buy a 15,000 sq. ft. factory at 815-819 Larrabee Street. This space was equipped with the latest in modern machinery, and the business was off and running.

“Milton E. Page, Jr. . . . has achieved prominence and influence in connection with the representative industrial activities of the western metropolis,” reported the 1918 edition of Manufacturing & Wholesale Industries of Chicago. “Mr. Page is a member of the National Association of Engineers and of the Chicago Steam Engineers’ Club. He has always manifested a vital interest in all things touching the welfare of his native city, is loyal and progressive in his civic attitude, and is a stalwart supporter of the principles of the republican party. He served several years as a member of the celebrated First Regiment of the Illinois National Guard, has received the thirty-second degree of Ancient Accepted Scottish Rite of the Masonic fraternity, besides being affiliated with Medinah Temple of the Mystic Shrine, the Chicago Lodge of Elks, and the Royal Areanum.”

“Milton E. Page, Jr. . . . has achieved prominence and influence in connection with the representative industrial activities of the western metropolis,” reported the 1918 edition of Manufacturing & Wholesale Industries of Chicago. “Mr. Page is a member of the National Association of Engineers and of the Chicago Steam Engineers’ Club. He has always manifested a vital interest in all things touching the welfare of his native city, is loyal and progressive in his civic attitude, and is a stalwart supporter of the principles of the republican party. He served several years as a member of the celebrated First Regiment of the Illinois National Guard, has received the thirty-second degree of Ancient Accepted Scottish Rite of the Masonic fraternity, besides being affiliated with Medinah Temple of the Mystic Shrine, the Chicago Lodge of Elks, and the Royal Areanum.”

Masons and mystics—sounds weird, but quite par-for-the-course for an early 20th century industrialist. Anyway, Milton Page Jr. succeeded in some respects by learning from his father’s mistakes, starting with an understandable focus on fire safety—a concern that was doubly serious in a time when boiler explosions were killing people on a regular basis.

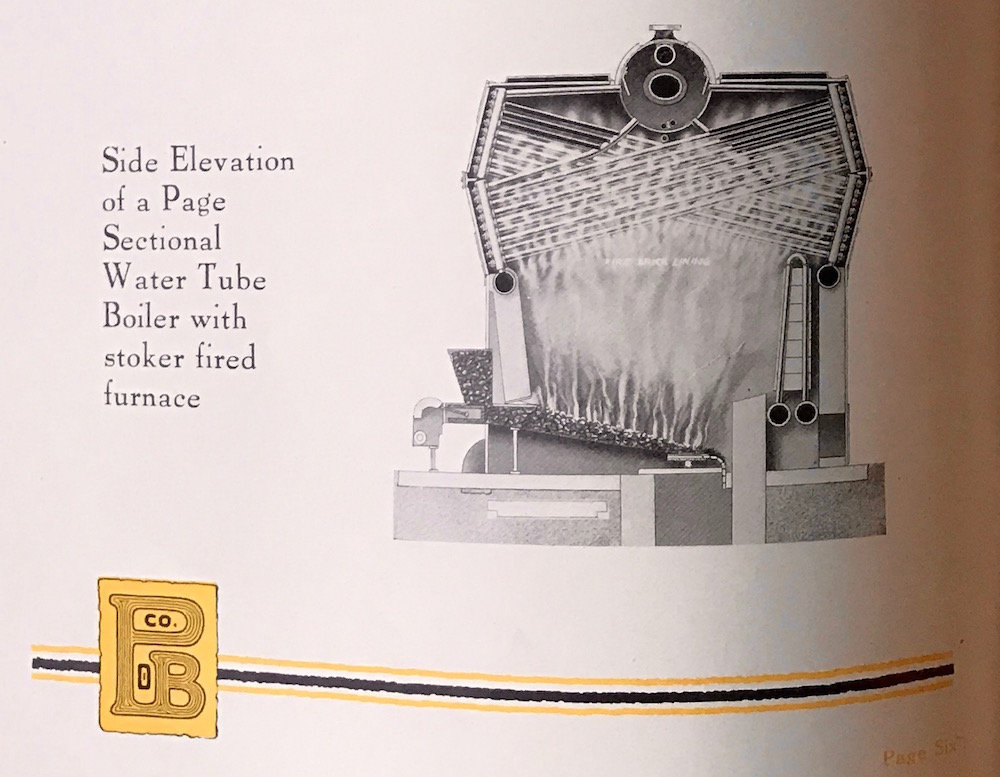

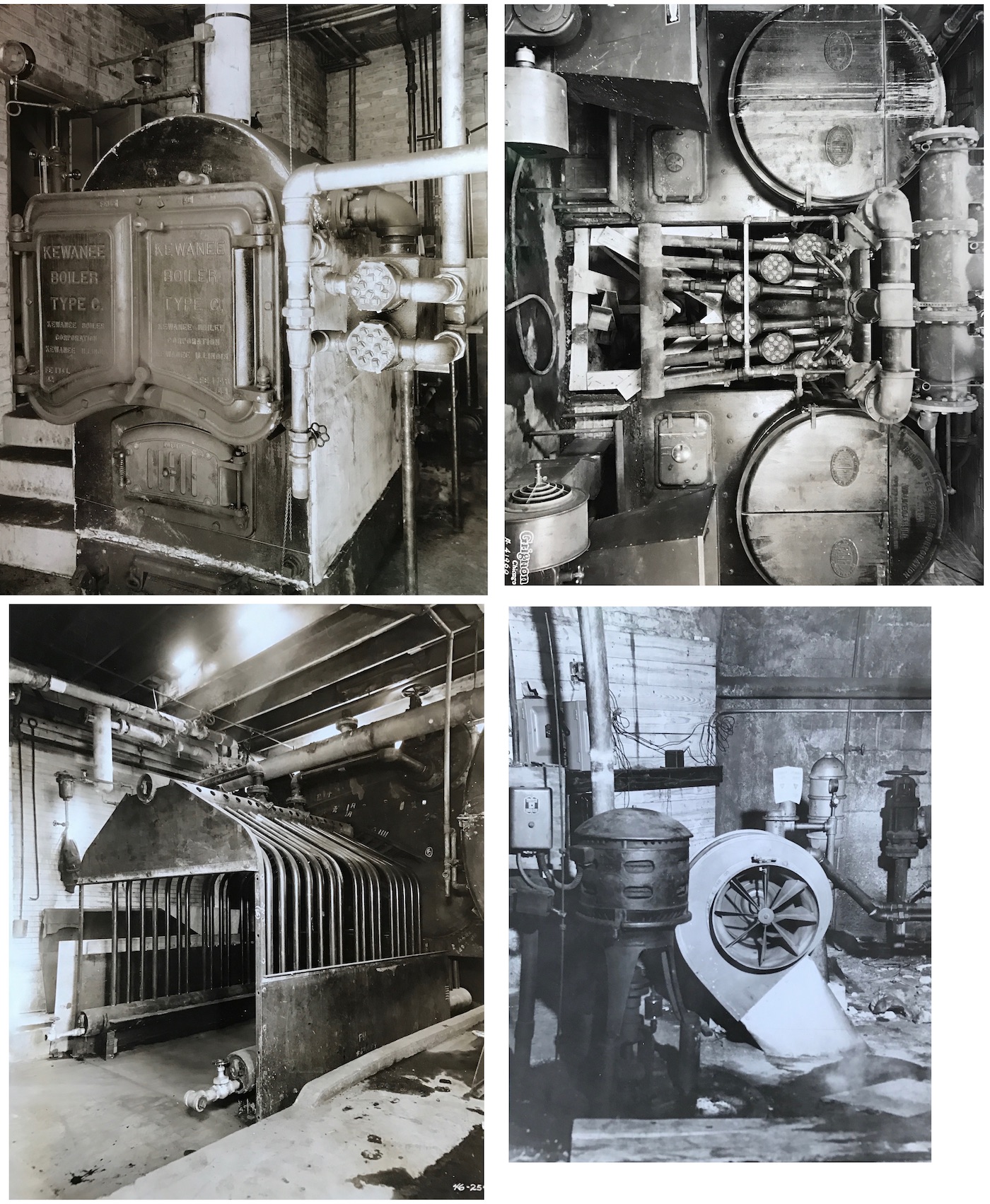

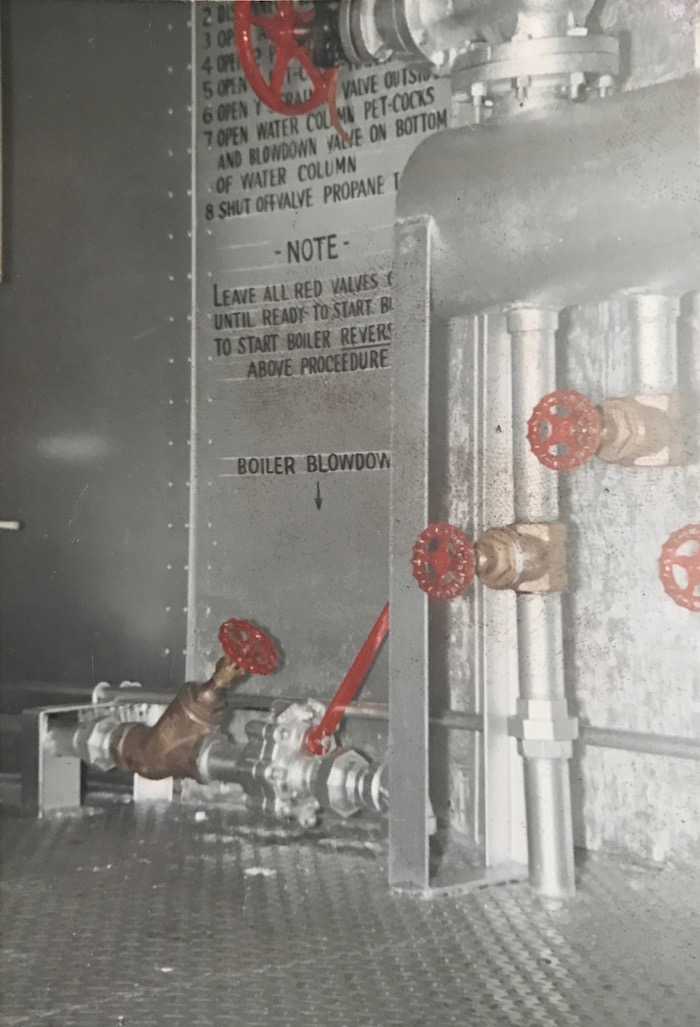

Fortunately, the Page Boiler Company was on the cutting edge when it came to that issue. They specialized in the latest and greatest innovations in water tube boilers—a far safer steam generator than the old combustible fire-tube models of the past.

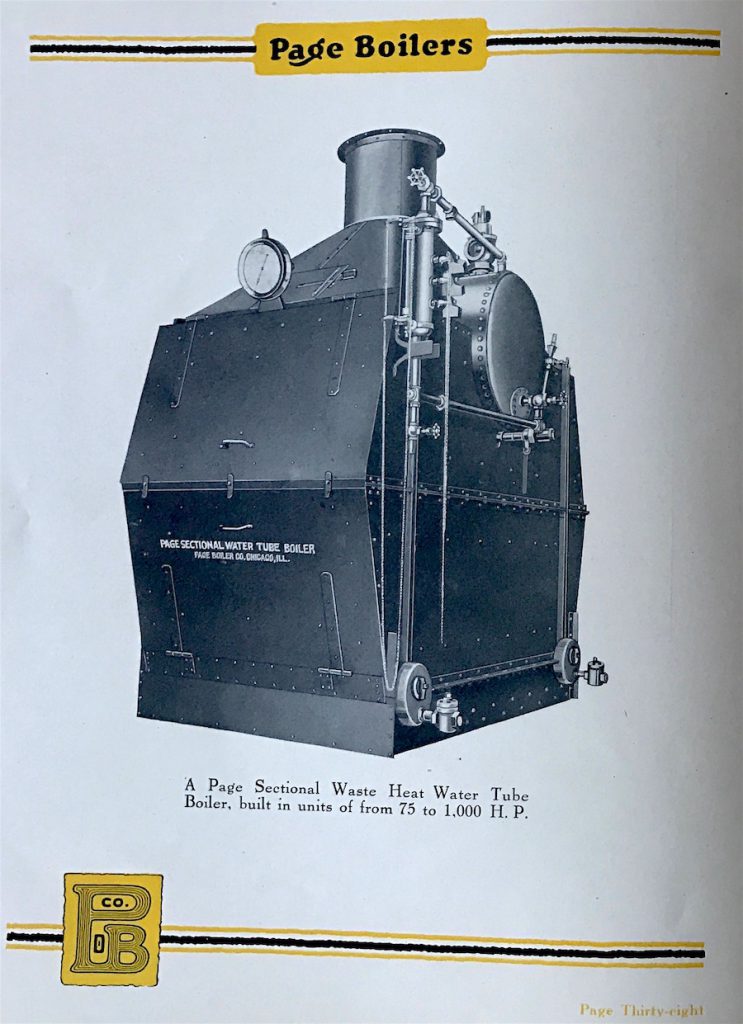

Rhode Islanders George Babcock & Stephen Wilcox had patented the first modern water tube boiler a few decades earlier, but refinements were coming rapidly as manufacturers across the country battled for regional dominance. Page did well enough that their clientele soon spread beyond Illinois, particular as demand grew for the Page-Burton sectional water-tube boilers—introduced in 1914. They were economical, efficient, easy to clean, and—as the marketing put it—“trouble is an unknown factor.”

“The Page Boiler was designed not only to perform all the established and essential functions of a high grade boiler,” M.E. Page, Jr. wrote in his company’s 1920 catalog, “but to fulfill two additional requisites in the installation of power plants, first—the need of a boiler capable of generating high capacity in small space, and secondly, a boiler of such design that it can easily be delivered through a small opening. The Page has well contributed to these requirements, it being the most compact and greatest producer of steam per cubic foot of space occupied, of any boiler on the market.

“The Page boiler,” he added, “is the result of many years of concentrated effort of our water tube boiler experts and is a masterpiece in simplicity and highly perfected boiler construction.”

“The Page boiler,” he added, “is the result of many years of concentrated effort of our water tube boiler experts and is a masterpiece in simplicity and highly perfected boiler construction.”

Both water-tube boilers and fire-tube boilers are still used today to help generate power for industrial facilities. But if you want technical details on how their construction has evolved or the physics behind steam power itself, this is the wrong website for you.

I took home a stack of early blueprints from the Page estate sale, including our featured one here that sketches out a plan for an updated boiler in Chicago Stadium (1929-1994)—former home of the Blackhawks (and later the Bulls). I’m not sure if Page—by now operating as the Page Water Tube Boiler Co.—actually carried on and completed this project, but it seems likely. Since Chicago Stadium is long gone, however, we can’t exactly go and check out the bowels of the building for verification.

By the 1940s, Page had relocated to the Lincoln Park address that would serve as its headquarters for nearly 60 years—815-819 W. Webster Avenue (currently updated into lofts, of course). The company was also operating as two businesses within one, as Milton Page’s inventive old buddy Adolph Johanson was now running his own side venture, the Johanson Water Heater Company, at the same address.

[The longtime Page plant at 815 W. Webster Avenue in Lincoln Park]

[The longtime Page plant at 815 W. Webster Avenue in Lincoln Park]

Both Page and Johanson remained vibrant and active into their later years, including turning the Webster factory into a military production plant during the war. When Milton Page died in 1948 at the ripe old age of 79, Adolph (probably realizing he was part of the last generation to ever bear that first name) took over the company. By the 1960s, it was Adolph’s own son Russell W. Johanson—rather than a Page descendant—who ascended to the top spot.

It wasn’t until the late 1990s that the Page Boiler Company finally left Webster Avenue behind and moved down to Bucktown, with the Johanson Water Heater Co. remaining its sister business. Much of the company’s later history—a bit bizarrely, since it exists in the internet age—is actually harder to research than those black-and-white days of yore. If you worked for the company and want to fill in the blanks of the “final chapter,” by all means!

[A Page Boiler truck, still red as always, in 2011]

[A Page Boiler truck, still red as always, in 2011]

Interestingly, the Better Business Bureau claims the Page Boiler Company “started on August 1, 1954.” Maybe there was some sort of reincorporating at that point under Russell Johansson, but there is no doubt that the modern business that carried into 2015 was the same one Milton Page started in a barn in 1905.

As for that abandoned factory I visited in 2015—it soon found a new tenant; a considerably younger and aesthetically louder one. One Hour Tees: Custom Printed Apparel. If you’re driving down Damen Avenue sometime and see a building with a giant mural of the dear departed wrestler Randy “Macho Man” Savage about to drop the elbow on someone. . . you’re looking at a the old Page Boiler Company plant. Be weirdly wistful.

[2348 N. Damen Avenue, c. 2010 and 2017]

[2348 N. Damen Avenue, c. 2010 and 2017]

[This 1920s nameplate notes the Aaball MFG Co., a common law trust formed by longtime Page VP Adolph Johanson. He clearly chose the name for strategic phonebook reasons.]

[This 1920s nameplate notes the Aaball MFG Co., a common law trust formed by longtime Page VP Adolph Johanson. He clearly chose the name for strategic phonebook reasons.]

[Unknown Page Boiler employees. If you recognize these fellas, let us know]

[Unknown Page Boiler employees. If you recognize these fellas, let us know]

Archived Reader Comments:

“Nice historical background regarding the Page Boiler Company. I noticed the catalog listing of the Sectional Waste Heat Water Tube Boiler of which I have the original artist rendition of this picture framed in my office. I look forward to stopping by the museum soon.” –Russ Rabago, Indeck Power Equipment Company, 2019

I think my great-grandfather is in the photo of “[Unknown Page Boiler employees. If you recognize these fellas, let us know]” on the right. His name was Edward Dixon Nelson and he sold boilers in Chicago in the 1910s-1931. He became a millionaire in 1914 and lost in all by 1931 when customers could not pay for the boilers that were already sold.