Museum Artifacts: Morton’s Free Running Salt and Sausage Seasoning (1930s) + Morton Salt Cardboard Store Display and Advertising Blotters (1950s)

Made By: Morton Salt Company, 1357 N. Elston Ave., Chicago, IL [Goose Island]

“Out of every 10 pounds of salt produced in this country, 9 you never see! . . . Of the salt you do see—table and household salt—only a little more than a billion pounds are consumed each year. But over 30 billion pounds were produced and needed in the nation last year for virtually every phase of commerce, industry, science and agriculture. For salt is the indispensable ingredient of modern life.” –Morton Salt advertisement, 1945

Morton Salt has never been a company too shy or humble to tout its own significance. A visit to the corporate website in 2023 still finds the firm glibly referring to itself as the “Quintessential American Brand,” and they might not even be wrong. Strangely, though, describing it on a smaller, regional scale as the “Quintessential Chicago Brand” actually feels like a more complicated proclamation.

Morton’s world headquarters is indeed still located downtown, most recently at 444 W. Lake Street—not far from where it all began—but there are no longer any active production plants in the city. That said, the company’s most famous Chicago facility—a landmarked warehouse complex at 1357 N. Elston Avenue (opened in 1930)—has arguably achieved a higher profile in recent years than it ever had before its closure in 2015.

In 2022, portions of the complex were re-furbished and officially re-opened as part of a major new indoor/outdoor concert venue called the “Salt Shed,” which—by popular demand—retained the original building’s massive Morton Salt Girl advertising mural on its roof.

It’s free advertising, too, because unlike most billboards visible to gridlocked motorists on the Kennedy Expressway, the sight of Morton’s petite, umbrella-wielding mascot is generally met with universal favor—a pleasant reminder of simple times sitting around the kitchen table with family . . . or, I suppose, a cute symbol of Chicago’s formerly ruthless industrial might.

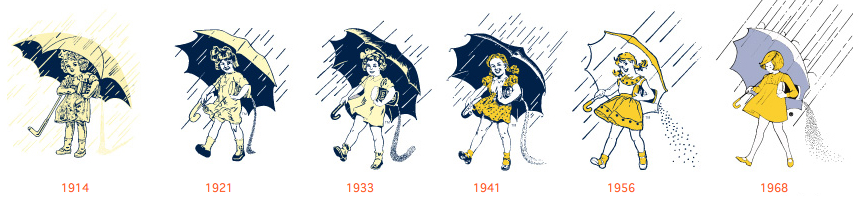

Of course, iconic character though she may be, the Morton Salt Girl has always been a bit of an evolving concept. She has gone through at least six distinct incarnations since making her first appearance in a series of Good Housekeeping advertisements in 1914. The original girl, as far as we know, wasn’t based on anyone in particular. But Girl No. 3—as seen on the Depression-era Morton container in our museum collection—clearly gives a nod to the biggest little movie star on the planet at the time . . . Shirley Temple. The curly hair wasn’t an entirely new twist, though—the very first Morton Girl had sported a similar look 20 years earlier.

[The full-scale Morton Girl logo on the back of our 1930s container includes far more intricate Shirley Temple-esque detailing than the simplified miniature logo on the front side]

Honestly, by the 1930s, Morton Salt could have re-cast the wee lass as an orangutan and it wouldn’t have dented their reputation. The company was already the largest single salt producer in the country, and its pun-tastic “When it Rains, It Pours” slogan had slipped into the everyday American lexicon. Meanwhile, in their home base of Chicago, the Morton family itself employed hundreds of local workers and earned a sterling status among the most charitable and influential forces in the private sector.

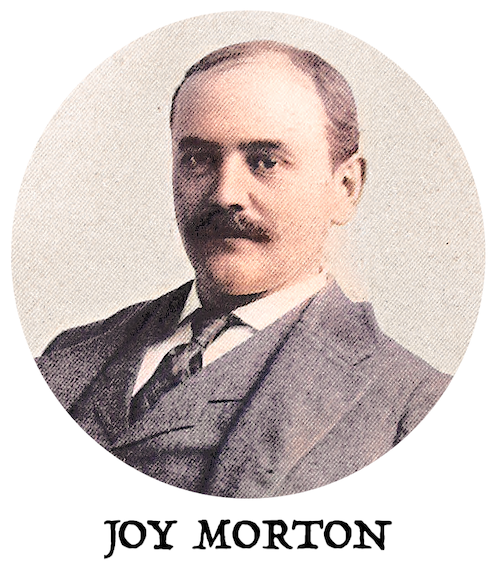

As the family patriarch and company founder, nobody did more to build that rep than Joy Morton, the dapper salt mogul who retained his position of Chairman of the Board right up until his death at the age of 78 in 1934 (shortly after the Shirley Temple salt girl made her debut). And yes, the man’s name was spelled J-O-Y, not J-A-Y . . . it was a tribute to the maiden name of his mother, Caroline Joy. Like Johnny Cash’s “Boy Named Sue,” growing up with a girl’s name might have helped Joy Morton build some personal character. Because even as the king of salt, he managed to connect with the salt of the earth.

[The evolution of the Morton Salt Girl over her first 50 years (mortonsalt.com)]

History of Morton Salt, Part I. Joy to the World

Born in Nebraska Territory in 1855, Joy Morton was the son of Julius Sterling Morton—the Secretary of Agriculture under Grover Cleveland, and the guy perhaps most famous for inventing the holiday of Arbor Day [he had also tried to make Nebraska a slave state before the Civil War, but that’s not a detail you tend to get as much info on in the typical corporate narrative].

Though they lived on the edge of the frontier, the Morton family wasn’t roughing it. Papa Morton earned his fortune as a newspaper publisher before getting his government gig, and he built quite the impressive estate in Nebraska City, complete with a White House look-a-like mansion and accompanying arboretum.

Though they lived on the edge of the frontier, the Morton family wasn’t roughing it. Papa Morton earned his fortune as a newspaper publisher before getting his government gig, and he built quite the impressive estate in Nebraska City, complete with a White House look-a-like mansion and accompanying arboretum.

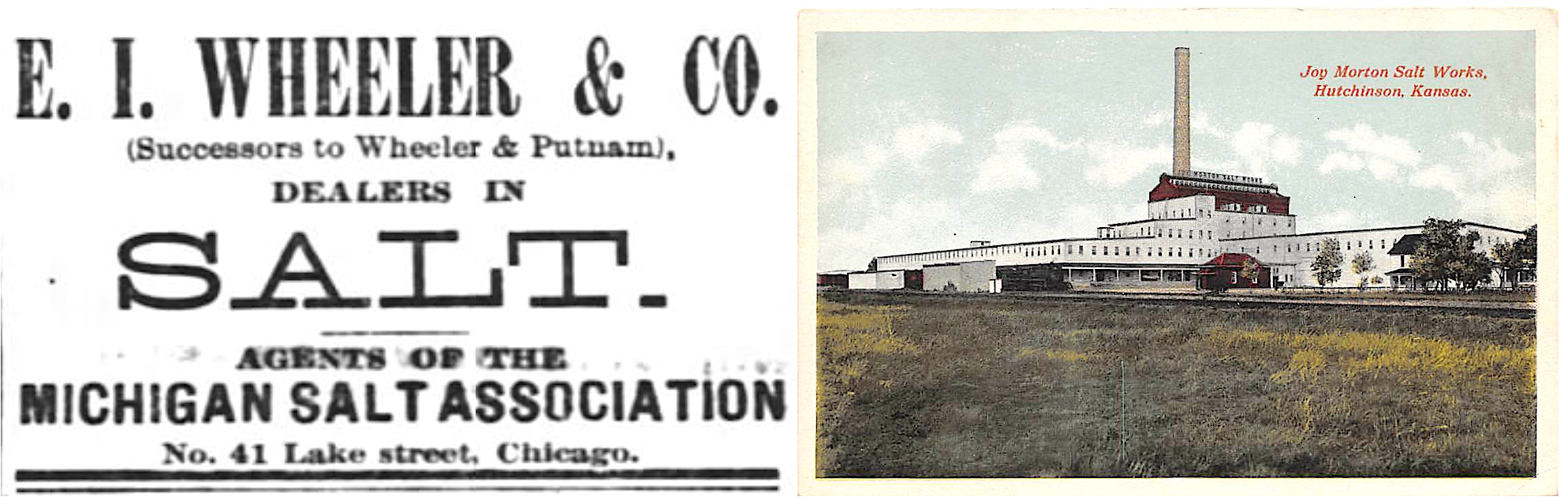

Joy shared his dad’s interest in plants and trees, as you’ll soon see, but he didn’t follow in his professional footsteps. Instead, he went to work in the railroad industry, starting in Omaha as a clerk in the treasurer’s office of the Burlington and Missouri River Railroad, then relocating to Aurora, Illinois, as a supply agent for the Chicago Burlington & Quincy Railroad. This career “track” eventually brought an ambitious and loaded 25 year-old Joy Morton into business in Chicago, where he bought his way into the salt firm of E. I. Wheeler & Company, under the tutelage of veteran salt man Ezra Wheeler (1838-1885). Joy got married the same year, laid down his roots, and went to work on his empire.

[Left: 1880 ad for E. I. Wheeler & Co., the precursor to Morton Salt. Right: The Joy Morton Salt Works in Hutchinson, Kansas, opened in 1898 and shown here, c. 1910s.]

II. Worth Their Salt

By 1885, following the death of Ezra Wheeler, Joy and his brother Mark Morton took over full financial control of Wheeler & Co. and rechristened it Joy Morton & Company. As with hundreds of other businesses, Morton benefited from a “right place / right time” element, as Chicago was the fast-growing central hub of America’s railway system, making it the perfect link between the salt mines and the industries they served.

“Joy Morton & Co.’s salt works receives car loads of salt from eastern points, which, after being worked through a certain process, is again shipped to nearly every point in the country,” the Chicago Chronicle reported in 1896. In the same article, Belt Railway Company superintendent James Warner claimed that Morton’s firm “handles 90 percent of the salt trade in its territory, and has the largest plant of any similar industry in the United States.”

Location wasn’t the whole of it, though. The Mortons were also genuinely savvy businessmen, always one step ahead of the competition, and two steps ahead of their own partners in the industry.

Joy Morton set up a warehouse at Randolph Street on the river, and worked out distribution deals and facility buyouts with top salt producers from Michigan and New York all the way to Kansas and—eventually—Utah. He also wisely balanced the company’s distribution budget with manufacturing and marketing power, and aggressively invested in a wide range of other industries—railroads, corn starch, meatpacking, and oat cereals, among others.

In 1905, the business magazine System interviewed the now 50 year-old Morton, asking the classic question posed to most prominent tycoons: to what did he attribute his success?

“I suppose I ought to say honesty, perseverance, hard work, and a dozen other qualities that the books tell us make fame and fortune,” Morton replied. “But, as a matter of fact, no man can put his finger on any definite qualities and say: ‘I owe my success to these.’ Success comes to the man who seizes the opportunities that come to all of us. Some of us see them and some of us don’t.”

Many of the stories told about Joy Morton in the press at this time seem intent on building him into a capitalist folk hero. For example, he is said to have broken up a labor strike by personally doing the grunt work that his own employees were refusing to do; the striking men were supposedly so gobsmacked that they decided to call the whole thing off. On another occasion, when a 40-year veteran of the salt works became too “infirm” to perform his duties, Joy sent him on a three-month holiday to recuperate, along with a check for $500. When the loyal employee returned to the Morton offices three months later, Joy informed the old-timer that his holiday was actually a full-time retirement, and that his full pay check would continue coming each month thereafter.

Inspiring leader or monopolistic conquerer . . . either way, Joy Morton was already the undisputed top dog of his industry by the early 20th century, controlling dozens of saltworks from his fancy office in the Railway Exchange Building at Jackson and Michigan. He was one of the one-percent of Chicago’s one-percent during the formative years of Daniel Burnham’s 1909 “Plan of Chicago.” But it would still take three more big developments to truly cement the Morton Salt Company as a cultural institution.

III. When It Rains . . .

The first of those big developments was the introduction of magnesium carbonate to the Morton “recipe” in 1911. Up to that point, commercial table salt was notorious for problematically clumping together in humid conditions. As the first major manufacturer to recognize that magnesium carbonate could safely counteract this effect and enable salt to flow freely anytime, anywhere, Morton launched a revolution.

The company capitalized further on this free-flowing innovation by creating a new container with a convenient pour spout and a distinctive blue paper label, which led to Big Development No. 2.

According to company lore, Morton rejected several pitches from the Philadelphia advertising agency N.W. Ayer & Son before jumping on a back-up idea that became the slogan “When It Rains, It Pours”—a clever reference to the aforementioned fact that Morton’s salt wouldn’t cake together when the humidity rose. From this concept, the first Morton Girl, with her yellow dress and umbrella, emerged.

Those original Good Housekeeping ads don’t really explain the science of magnesium carbonate—they just hit you with some mad lyrical flow instead:

“Never cakes or hardens in any kind of weather—it pours.

No need to shake it—No need to bake it—it pours.”

[A pair of advertisements from 1917/1918, featuring the original iteration of the Morton Salt Girl and the “It Pours” slogan on the blue can]

For all its mighty conveniences, though, the addition of magnesium carbonate probably did considerably less for the public good than the introduction of another new ingredient in 1924 . . . Iodine!

During the early 1920s, Dr. David Murray Cowie of the University of Michigan had championed a theory that adding iodine to common table salt could help combat one of the major public health problems of the time—endemic goiters. Since goiters were linked to iodine deficiencies, particularly in high-risk regions throughout the Midwest, making small doses of iodine more readily available in an affordable, everyday food additive seemed the ideal course of action.

Cowie was successful in getting many of the local salt companies in Michigan to embrace the plan, but in Chicago, Morton president Sterling Morton (Joy’s son) and his team were hesitant at first. While those 10-cent pourable containers were dominating America’s kitchen pantries, domestic commercial sales still accounted for a minority of Morton’s overall business, so making a formula change aimed only at the home market sounded risky. As the promising early returns arrived on Cowie’s work in Michigan, however, Morton was quick to reverse course and join the cause. By the fall of 1924, they became the first company to sell iodized salt nationally, and it quickly emerged as a new prominent selling point.

Cowie was successful in getting many of the local salt companies in Michigan to embrace the plan, but in Chicago, Morton president Sterling Morton (Joy’s son) and his team were hesitant at first. While those 10-cent pourable containers were dominating America’s kitchen pantries, domestic commercial sales still accounted for a minority of Morton’s overall business, so making a formula change aimed only at the home market sounded risky. As the promising early returns arrived on Cowie’s work in Michigan, however, Morton was quick to reverse course and join the cause. By the fall of 1924, they became the first company to sell iodized salt nationally, and it quickly emerged as a new prominent selling point.

Within a decade of its debut, iodized salt accounted for more than 90% of the table salt market, and Morton was touting not only its success in drastically reducing the goiter epidemic, but various other benefits, as well.

“Taller! Heavier! Children protected against simple goiter are found to be superior in development,” a 1934 Morton ad read. “Iodine, by protecting children from simple goiter, exerts a remarkably beneficial effect on growth. . . . If you want your children to escape being handicapped by this disorder, begin to use Morton’s Iodized Salt at once!“

[Advertisements for Morton’s Iodized Salt, from 1929 (left) and 1932]

IV. Elston & Elsewhere

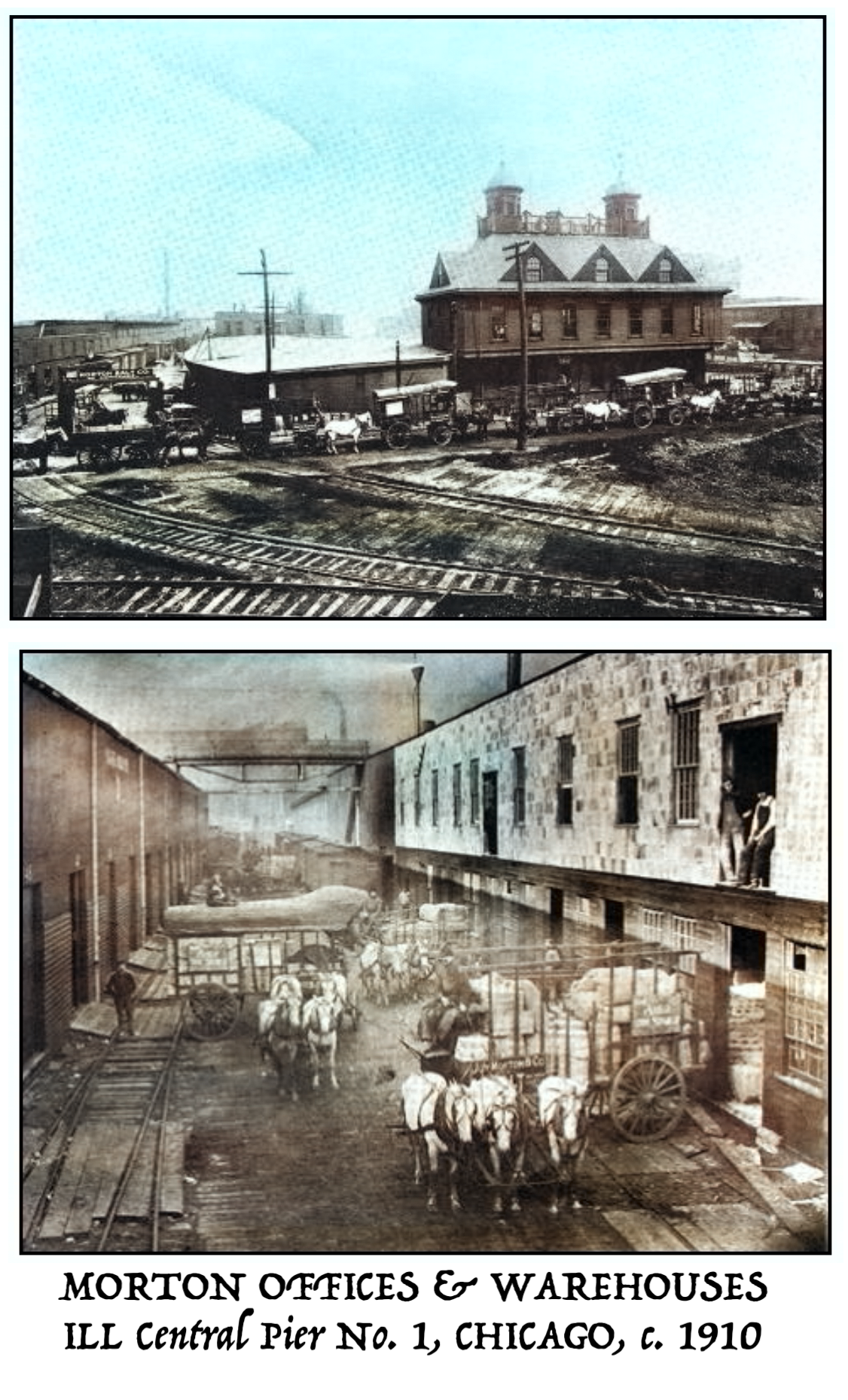

In the midst of the iodized salt revolution, in 1927, Morton’s longtime Chicago hub at Illinois Central Pier No. 1 was severely damaged by a fire. This event began a major transitional phase for the company, as its corporate offices moved into a new high-rise at 208 W. Washington St. (aka the Morton Building) and local production relocated to a brand new facility along the North Branch of the Chicago River. Both the office building and the salt warehouse were designed by the architectural firm of Graham, Anderson, Probst & White; the same chaps responsible for a slew of other iconic building of the period, including Union Station, the Wrigley Building, and the Shedd Aquarium.

As such, the cavernous salt shed on Elston Avenue, aka “Elston Dock,” went above and beyond any type of traditional riverfront warehouse yet seen in the city. The multi-use space included “office space for printing and record storage, a boiler house, main shipping and packing floors, twin bulk salt storage sheds, a garage and repair shop, and an overhead conveyor system,” according to a later account in the building’s official landmark status report.

As such, the cavernous salt shed on Elston Avenue, aka “Elston Dock,” went above and beyond any type of traditional riverfront warehouse yet seen in the city. The multi-use space included “office space for printing and record storage, a boiler house, main shipping and packing floors, twin bulk salt storage sheds, a garage and repair shop, and an overhead conveyor system,” according to a later account in the building’s official landmark status report.

The conveyors, in particular, would still leave a 21st century onlooker in awe, as the main warehouse’s steel truss roof allow workers to manipulate massive amounts of salt into organized piles on the factory floor, ready for carrying out for treatment and shipment. Reinforced concrete walls kept the piles contained; a defense system that remained fairly dependable up until 2014, when the west bulk house famously “overflowed” and sent a cascade of salt into the car dealership nextdoor.

Inside Morton’s Elston Dock Warehouse, 1940s

[Top Left: Salt shed conveyor system. Top Right: Salt being poured from conveyor belt to floor below. Bottom Left: Packaging table salt into cardboard containers. Bottom Right: Loading rock salt from the west shed for use on Chicago’s winter roads. source: Morton’s Spout newsletter, Feb and Aug, 1946]

The completion of the Elston Dock facilities in 1930 coincided with the retirement of Joy Morton from the company presidency at the age of 75 (he died four years later). Daniel Peterkin, a longtime executive, took over the role, while Joy’s son Sterling Morton served as vice president.

Despite the challenges of the Great Depression, or maybe partly as a consequence thereof, the Morton Salt Company continued to expand its influence during the 1930s, acquiring greater control of its product at the source (by buying up salt mines) and entering into the wider chemical additive marketplace. During World War II, the company’s marketing reflected these changes, as the friendly face of the Morton Salt Girl was complemented and contrasted by images of fighter planes and blast furnaces, signifying salt’s significance far beyond the kitchen.

Despite the challenges of the Great Depression, or maybe partly as a consequence thereof, the Morton Salt Company continued to expand its influence during the 1930s, acquiring greater control of its product at the source (by buying up salt mines) and entering into the wider chemical additive marketplace. During World War II, the company’s marketing reflected these changes, as the friendly face of the Morton Salt Girl was complemented and contrasted by images of fighter planes and blast furnaces, signifying salt’s significance far beyond the kitchen.

“Tanks, guns, high octane gasoline, synthetic rubber, dyes and healing drugs are all products that salt helps to produce,” read a 1943 ad. “Morton, the world’s largest distributor of salt, pledges a continued economical supply of this necessary mineral for industry as well as for salt’s more than 1400 other uses. Morton’s famous round blue package of purest salt still costs the average family only about 26 a week to use.”

By 1950, Morton Salt operated at least 12 major production plants across North America, employing close to 4,000 people. A new branch of the business, the Morton Chemical Company, opened a research lab in suburban Woodstock, Illinois, in 1954, the same year that a brand new corporate headquarters for the main business was commissioned in downtown Chicago at 110 North Wacker Drive. The old Elston Dock complex, meanwhile, became far more visible to the average Chicagoan following the completion of the Northwest Expressway (later renamed Kennedy) in 1960.

[The former longtime Morton Salt headquarters at 110 N. Wacker Drive, as seen in the late 1950s / early 1960s. The building has since been demolished. Interior photos from Chicago History Museum’s Hedrich-Blessing Collection]

V: Legacies and Such

Back during the 1920s, a semi-retired and financially unbridled Joy Morton began transforming his sprawling estate in Lisle, Illinois, into a public nature preserve known as the Morton Arboretum.

Still open to visitors today, the Arboretum carried on the legacy started by Joy’s father, and includes 1,700 acres of carefully managed trees and plants from around the world. A library dedicated to Joy’s son Sterling Morton is also on the premises.

Still open to visitors today, the Arboretum carried on the legacy started by Joy’s father, and includes 1,700 acres of carefully managed trees and plants from around the world. A library dedicated to Joy’s son Sterling Morton is also on the premises.

Meanwhile, nearly a century after Joy’s death, the Morton Salt Company remains the number one salt producer in North America, although there have been plenty of the obligatory mergers, acquisitions, and re-formations along the way. In 2009, the company, by then known as Morton International, was purchased by a German conglomerate, K & S Group, which oversaw the closure of the Elston complex in 2015 and the recent opening of Morton’s new Chicago headquarters at 444 W. Lake Street.

Uniquely unchanged, of course, is the company’s product packaging, which just might be, non-coincidentally, the most recognizable of any in America.

Sources:

Chicago: A Food Biography, by Daniel R. Block, Howard B. Rosing

Salt: A World History, by Mark Kurlansky

“Morton Salt Company Warehouse Complex” – Landmark Designation Report, 2021

“Wonder of a Belt Line” – Chicago Chronicle, March 29, 1896

“Successful Through System: Joy Morton” – System Magazine, Vol. 7, 1905

“When it Rains it Pours: Endemic Goiter, Iodized Salt, and David Murray Cowie, MD,” by Howard Markel, MD, American Journal of Public Health, February 1987, Vol. 77, No. 2

Chicago Business: “Morton Salt to Shutter Elston Avenue Warehouse”

Chicago Tribune: May 10, 1934: “Jay Morton Dies Suddenly”

I never find anything about the Morton Salt Boy in Rain Coat as seen on salt and pepper shakers with the wording “premium since 1876? Is there any information about him?

My father Richard Wade Pritchard snd my Grandfather Richard Wesley Pritchard both worked for the Morton Salt Co. … my Grandfather had a stroke when traveling from home in WV into Ohio territory 1963 and didn’t return. My dad put in 42 years and retired around 1986. When he retired he worked the East Coast, office outside Phila. I have a picture of me as an infant 1950 with a copy of Spout Magazine next to me. Is it still printed? Was it just fir employees.

My sister died 5 years ago and I inherited some of her belongings. Among them is a box of land he pieces rock salt sent from Morton Salt Company on 12/2/63, with $.18 postage.

I don’t know why the reason Morton Salt Company sent these to her and I guess I never will. Or maybe someone at the company knows.

Is this of interest to you?

I would like to know the history of the alternate “shaker” on the top which appears in the 50’s. Our family lore tells us that our uncle, Earl Fredette, designed it.

I have picked up , at an estate sale, a 6” in diameter disc: one side cardboard with Morton’s Salt, When it rains it pours in a circle with the trademark girl and umbrella.

At the bottom it reads “ MFG’D BY MONARCH DISPLAY & EQUIPMENT COMPANY DES-MOINES- IOWA. PATENT PENDING.

The opposite side appears to be an attached aluminum disc, with grooved circles throughout.

What was it’s purpose?

P.S. I think my mom had/used one on her gas range, 1954-80. I didn’t know what it was then either!

why did they discontinue the alternate shaker?