Museum Artifact: Sterling Desk Fan, c. 1940

Made By: Chicago Electric MFG, Co., 6333 W. 65th Street., Chicago, IL [Bedford Park]

Some time in the early 1970s, the singer/songwriter Gram Parsons—pioneer of the genre later known as “alternative country”—was hanging out with his buddy Keith Richards, talking about song ideas.

“I’ve been writing about a guy that builds cars,” Parsons said—this according to Richards’ own account in his 2010 memoir, Life. When Keith eventually heard the finished product, a lovely pedal-steel inflected track called “The New Soft Shoe” (complete with Emmylou Harris backing vocals), he was blown away.

“Gram was a storyteller,” Richards wrote, presumably mumbling to himself and coughing sporadically as he typed. “He could write you a song that came right around the corner and straight in the front, up the back, with a little curve on it. ‘The New Soft Shoe’—you listen to it and it’s a story—written about Mr. Cord, innovative creator of the beautiful Cord automobile, built on his own dime and deliberately crushed out by the triumvirate of Ford, Chrysler, and General Motors.”

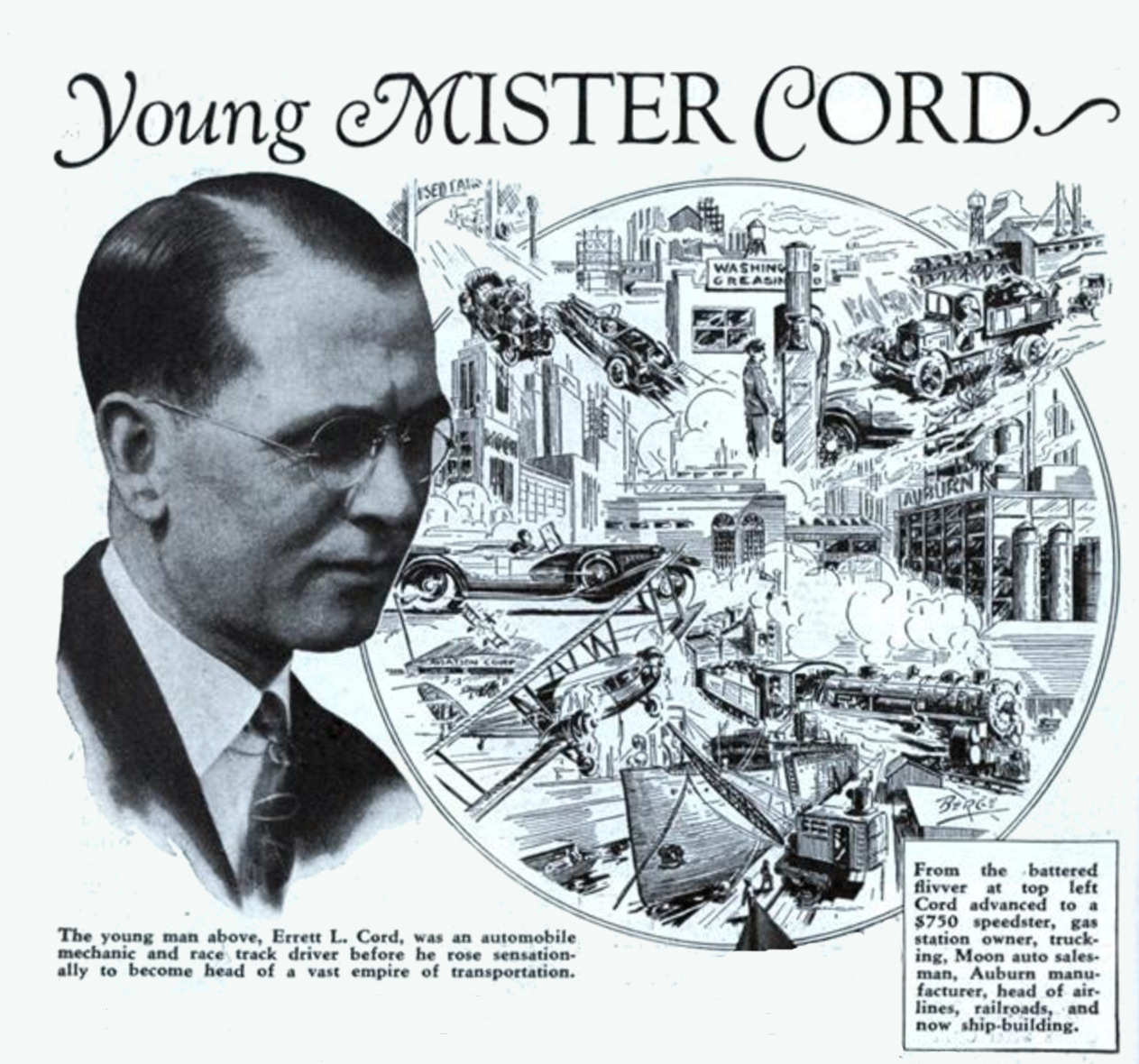

The “Mr. Cord” in question was Errett Lobban Cord (1894-1974), aka E.L. Cord—a transportation magnate and dice-rolling businessman who would have made a fine golf partner for William Randolph Hearst and Howard Hughes.

Equal parts charming and ruthless, Cord owned a controlling share in dozens of different companies across his lifetime, including the likes of the original Checker Taxi Cab Company and American freakin’ Airlines. One of his other pet properties, as you’ll likely be glad to know this far into the article, was the Chicago Electric Manufacturing Company.

According to Griffith Borgeson’s 1984 book, Errett Lobban Cord: His Empire, His Motor Cars, Chicago Electric was actually one of the young tycoon’s personal “favorite companies, one that he downright loved, and of which he was very proud. . . . There was something ingeniously catchy about its products, all of which gave excellent service and were, in addition, priced to give fits to the giants in the field, such as General Electric.”

According to Griffith Borgeson’s 1984 book, Errett Lobban Cord: His Empire, His Motor Cars, Chicago Electric was actually one of the young tycoon’s personal “favorite companies, one that he downright loved, and of which he was very proud. . . . There was something ingeniously catchy about its products, all of which gave excellent service and were, in addition, priced to give fits to the giants in the field, such as General Electric.”

Outsmarting the big boys—that’s what Cord was all about.

Part I: “The New Soft Shoe”

E. L. Cord first acquired his controlling interest in the Chicago Electric MFG Co. in 1927, less than a year after his unorthodox and highly profitable sales tactics had elevated him to the presidency of the Auburn Automobile Company in Indiana.

He was, above all else, a car guy. Coming up in Los Angeles by way of Joliet, Illinois, Cord raced cars in his youth, worked on them as a mechanic, and eventually sold them with a creativity, flair, and intelligence that made him the envy of his own superiors. In the early 1920s, he took a job back in Chicago at the Moon Auto Agency, where he quickly gained a reputation as the Midwest’s car dealer savant. Soon, he was enticed away by some auto industry friends and asked to put his energy toward saving the floundering Auburn Auto Co.

[The 1930 Cord L-29 Cabriolet, from Chicago Vintage Motor Carriage]

[The 1930 Cord L-29 Cabriolet, from Chicago Vintage Motor Carriage]

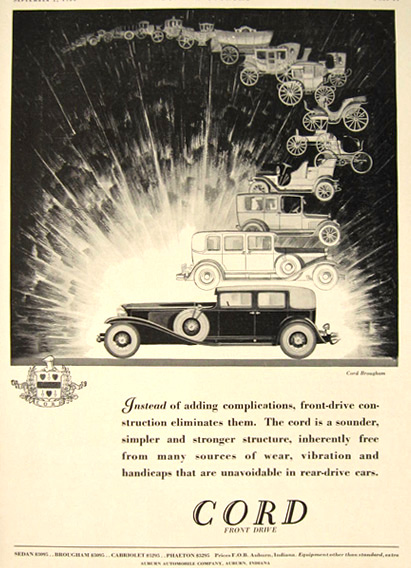

Still just 30 years old, Cord went to work at Auburn in 1924 and didn’t disappoint. He pulled the company from the brink of bankruptcy with some simple, practical moves—repainting the existing 700 car inventory, adding a nickel-plated finish, swapping in a new straight-eight engine, and temporarily slashing prices to get the product moving. Shortly thereafter, he worked with a leading designer to produce the first automobile under his own name—the classy Cord L-29—also the first U.S. passenger car with front-wheel drive. It wasn’t an elite seller, but as Gram Parsons, Keith Richards, and many car connoisseurs would agree, it was a “beautiful” vehicle.

Within a few years, Cord built a whole regional network of parts suppliers, distributors, designers, and craftsmen to ramp up production. He bought the esteemed Dusenberg Motor Co. and worked with experienced pros like A.H. Walker of the A.H. Walker Co. of Indianapolis and James Bobb of the Limousine Body Company to keeps the gears turning and bring his visions to life.

It was forty or fifty years ago

It was forty or fifty years ago

A big shot played with time

Mister Walker held the dough

And both kept Cord in line

Watched and checked on every single day

Building his own special cars

His very special way

Ooh, the new soft shoe

Ooh, the new soft shoe

Keith Richards may have seen Cord as the victimized genius in Gram Parsons’ song, but when you know the history, the first verse of “The New Soft Shoe” becomes a bit less cryptic and more like a commentary. For one thing, we’re transcribing the lyrics differently than 90% of the internet. Rather than “Mr. Walker held the door / and both kept cord and line,” as most sources claim, I think Gram might have done his research, making direct reference to the aforementioned A.H. Walker (Mr. Walker) holding the “dough,” and keeping Cord in line. Even the “both” might actually be “Bobb” for James Bobb, who was doing his own share of keeping E.L. in line.

The phrase “new soft shoe” is also an interesting twist on an old salesman’s expression—when you “give ‘em the old soft shoe,” it means you’re using a calm, conciliatory approach to quietly lure a customer into a purchase; like tap-dancing on soft-soled shoes in the Vaudeville sense. The “new soft shoe,” then, is really a reference to E.L. Cord’s notorious ability to effortlessly charm the buying public—his modern adaptation of a sneaky old sales tactic.

Cord was good at knowing what the people wanted, or at least, what they wanted to hear and how they wanted to hear it. Ironically, Keith Richards—in the same passage of his book—gave Gram Parsons similar credit for his powers of persuasion: “He had this unique thing that I’ve never seen any other guy do: he could make bitches cry. Even hardened waitresses in the Palomino bar who’d heard it all. He could bring tears to their eyes and he could bring that melancholy yearning. . . . It wasn’t boo-hoo, it was heartstrings.” Maybe Gram felt a weird sense of camaraderie with Cord, who coincidentally died the same year this song was released.

In any case, some people are simply born smooth operators. And like many of the great wheelers and dealers of his day, Mr. Cord’s supreme self confidence and meticulousness were the engines behind every decision he made. They didn’t always guide him in the right direction, financially or ethically, and they earned him as many enemies as friends. But he was firmly convinced that the same basic strategies he applied to the auto industry would work in whatever other endeavors he pursued with his newfound fortune.

Part II: Cord Goes Electric in Chicago

According to Borgeson, Cord used to tell his friends, “If you like a certain kind of soap, buy that stock. Don’t let somebody else tell you what to buy. Buy what YOU think is a good company, and then keep informed about the progress that it’s making.”

According to Borgeson, Cord used to tell his friends, “If you like a certain kind of soap, buy that stock. Don’t let somebody else tell you what to buy. Buy what YOU think is a good company, and then keep informed about the progress that it’s making.”

And so, within months of becoming the youngest top auto executive in the world, E.L. Cord also became an electronic appliances executive, buying a large chunk of a long established but scuffling Chicago company that—from his perspective—just needed a little nudge in the right direction.

What Cord may or may not have realized was that the Chicago Electric MFG Co. already had a resident Renaissance Man in the house. Edward S. Preston, who was ten years Cord’s senior, was still the president of the company. He was also the wizard behind many of those “ingenious” kitchen products that Cord would come to admire.

E.S. Preston was born in Belleville, Illinois, in 1884, joined the Chicago Electric MFG Co. in 1916, and became its president in 1926 at the age of 42. The company’s history before his arrival is a bit hard to navigate.

[Chicago Electric magazine ad from 1911]

[Chicago Electric magazine ad from 1911]

Chicago Electric was supposedly founded by a guy named Samuel George Arnold in either 1902 or 1903, with a focus on switchboards, but you can find newspaper accounts of a “Chicago Electric Manufacturing Company” as far back as 1891. This may have been an entirely unrelated company or an earlier manifestation of the same entity. Either way, we’re talking about a business founded at the dawning of the electrical and motor age, and it reached its tentacles into both fields, building electric home appliances and automotive lighting and heating devices. The company also apparently made an electrified “horse trainer” designed to shock giant animals into submission. They were clearly casting a wide net.

As Edward Preston moved up the ranks, perhaps by no coincidence, Chicago Electric began to find its identity a bit, using the “Handy” and “HandyHot” brand names for its expanding line of cheap but fairly dependable car parts and housewares. The factory was located at 2817 S. Halsted Street when Preston took the helm, but it moved to a larger headquarters at 6333 W. 65th Street in Bedford Park by the mid 1930s.

[The former Chicago Electric factory at 6333 W. 65th St., now occupied by NALCO]

[The former Chicago Electric factory at 6333 W. 65th St., now occupied by NALCO]

Preston collected piles of patents during the Depression, mostly on kitchen gadgets. But not unlike Cord, he was really a car guy at heart—a member of the Society of Automotive Engineers—and he fancied himself more of a mechanic than a businessman. This may have fostered a mutual respect between the two men, along with the occasional butting of heads.

Of course, Cord was often too distracted to fight his own battles. While fine-tuning the Cord automobile and running a multitude of other companies through his massive “Cord Corporation,” he appointed his trusted lawyer, Raymond S. Pruitt, to be his eyes and ears at Chicago Electric, serving as vice president. Fortunately, Pruitt and Preston seemed to co-exist effectively, deftly braving the 1930s together. As it turned out, the company’s undercutting price structure—encouraged by Cord—only gained more favor during trying times.

It didn’t hurt that Preston and his team also produced a lot of “handy” and appealing products. Along with its line of electric toasters, waffle molds, corn poppers, juicers, and percolators, Chicago Electric was ahead of the curve on portability. The lightweight Handyhot Deluxe Travel Iron had a fold-down handle for easy storage; an “ice cream freezer” did just that on-the-go; and a bizarre miniature electric washing machine—“about the size of a five gallon can”—moved plenty of units.

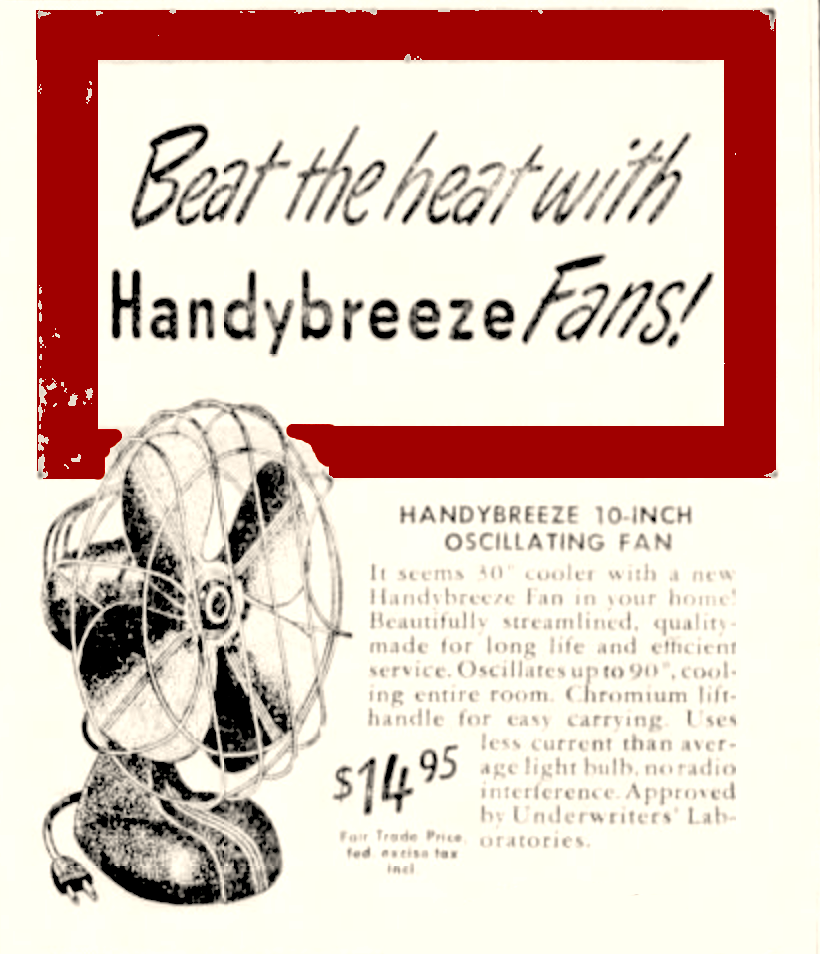

Where the company really outpaced the competition, though, was in the portable fan department. Some of the 1930s and ‘40s era Chicago Electric fans carried the name “Sterling,” like the green one in our collection. But the “HandyBreeze” name was more widely used, and would remain in circulation (again, pun intended) even after Chicago Electric was sold to the Silex Corporation in 1953.

[Chicago Electric “HandyBreeze” ad from 1939]

[Chicago Electric “HandyBreeze” ad from 1939]

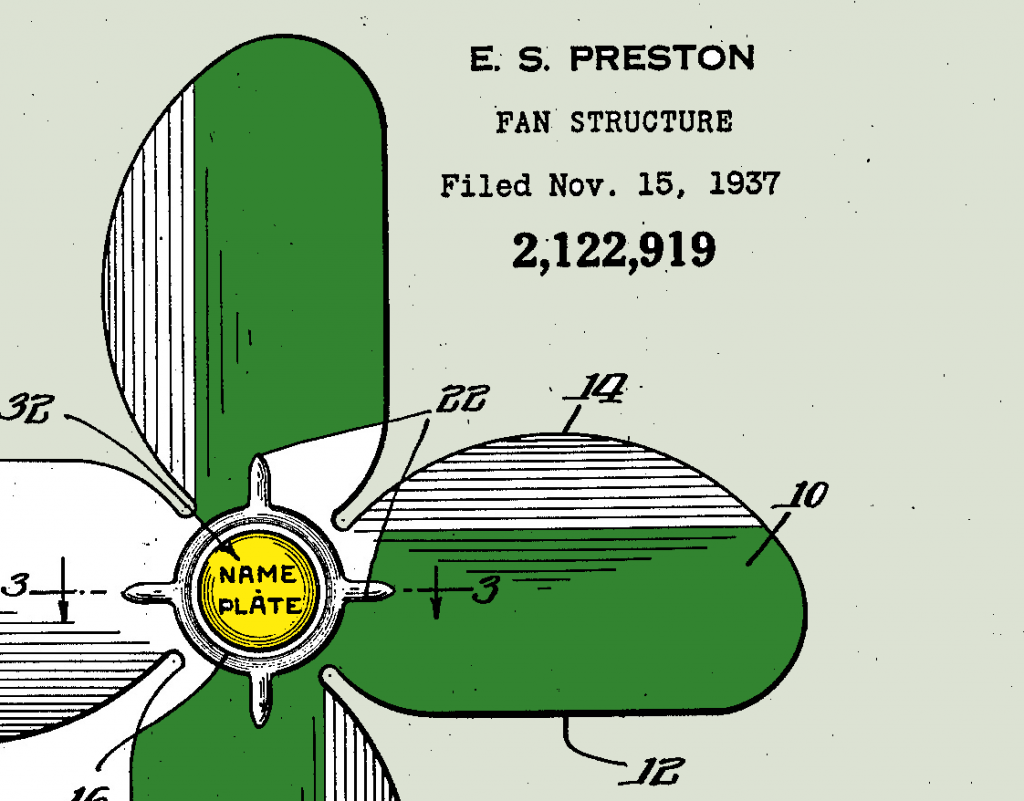

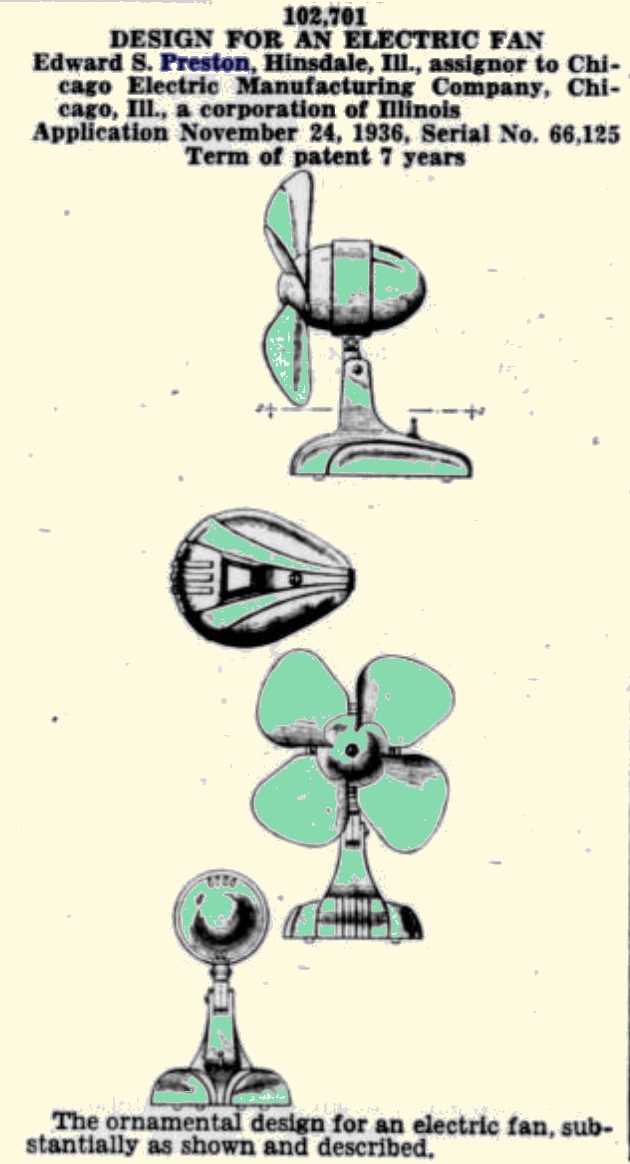

As for the Sterling Fan in our collection, its origin dates back to 1937, when E.S. Preston filed a patent (No. 2,122,919) for a new design that made it easier to install and replace a nameplate in-between the four sheet metal blades. Why was it necessary to start branding fans inside the dangerous interior of the unit instead of just somewhere on the base? Because. . . progress!

“It is an object of the present invention,” Preston wrote, “to provide a fan blade structure which may be readily stamped or otherwise formed out of any suit [in a] central position where it will not interfere with the action of the fan and serves to give a finished appearance to the article, as well as providing an admirable position for the situation of the necessary informative designations relating to the device, such as, for example, the manufacturer’s name.”

Like many electrical products of the era, the Sterling fan also had the stamp of certification from the mighty Underwriters Laboratories, which still operates today out of suburban Northbrook, IL.

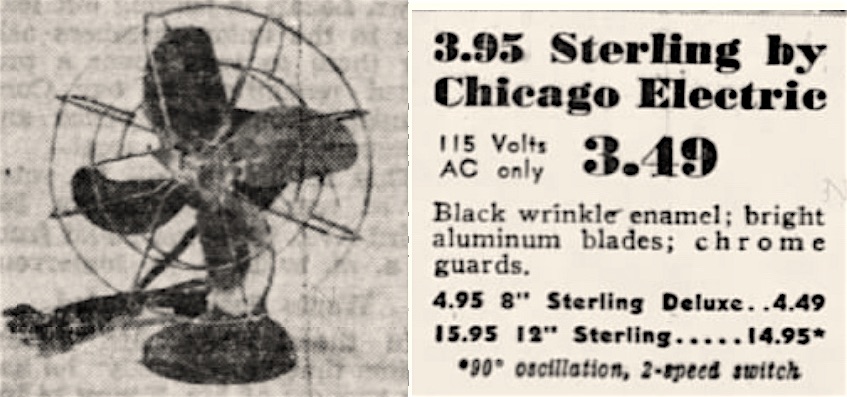

[A later period Sterling desk fan from a newspaper ad in 1951]

[A later period Sterling desk fan from a newspaper ad in 1951]

Worth noting, the Sterling name was also used for some of Chicago Electric’s electric space heater units, one of which we also happen to have in the museum collection. You can click the image below to get a closer look at that shiny satellite dish of yore.

Part III: Cord Unplugged

While things were staying afloat at Chicago Electric in the ‘30s, it was becoming a much more bizarre story for E.L. Cord. From his palatial estate in Santa Monica, CA, he was presiding over a growing industrial empire. But in a country in which millions were falling into poverty, there was increasing government scrutiny on those men who’d improbably bucked the trends of the day.

Without going into detail, let’s just say that not everything about the Cord Corporation was likely on the up-and-up. Shady deals were going down, whispers were being uttered where they shouldn’t, and—on a more observable level—workers were being shortchanged and mistreated.

According to George Hopkins’ 1982 airline industry history, Flying the Line, “E. L. Cord’s real value [at American Airlines] was to make working pilots of that era realize just how ruthless their employers could be, thereby encouraging the growth of unionism.

According to George Hopkins’ 1982 airline industry history, Flying the Line, “E. L. Cord’s real value [at American Airlines] was to make working pilots of that era realize just how ruthless their employers could be, thereby encouraging the growth of unionism.

“Anyone familiar with Cord’s history as an employer knew there was bound to be trouble. His industrial enterprises were notorious for low wages, union-busting, and poor working conditions. But personally Cord was a charmer, a characteristic he shared with a great many other early airline owners.”

In 1932, Cord was leaving his charm at the door entirely. With many of his pilots on strike, he started a smear campaign to paint them all as Communists, going as far as to plead his case to the U.S. Congress, demanding federal protection. New York Rep. Fiorello LaGuardia responded by calling Cord “low, dishonest, a liar and a gangster.”

Two years later, with more heat coming down on his various investments, Cord suddenly moved his whole family, including four kids, to England. Rumors were swirling that he was spooked by kidnapping threats (this was two years after the Lindbergh baby). “Hooey, hooey, hooey,” Cord told reporters in London, claiming he was just on a nice family vacation. “According to these reports, I must have left with my shirttail flying.” Even so, the rumors continued.

E. L. Cord eventually returned to the states, but he sold the Cord Corporation in 1937, bringing at least a temporary end to his work with planes, trains, and automobiles. Even during his semi-retirement out in Nevada, however, he kept investing in new pursuits—buying one of the first TV stations in the region, and getting into ranching, oil, you name it. Through it all, he also maintained his shares in the Chicago Electric Manufacturing Co., his old favorite.

E. L. Cord eventually returned to the states, but he sold the Cord Corporation in 1937, bringing at least a temporary end to his work with planes, trains, and automobiles. Even during his semi-retirement out in Nevada, however, he kept investing in new pursuits—buying one of the first TV stations in the region, and getting into ranching, oil, you name it. Through it all, he also maintained his shares in the Chicago Electric Manufacturing Co., his old favorite.

After World War II—during which Chicago Electric got by making fuses and electrical parts for the military—Cord decided to jump back into the game with his prized Windy City property. Seeing a new golden age ahead in electric appliances during peacetime, he bought out all the shares from a now elderly Edward Preston in 1945, becoming the majority owner of Chicago Electric. Harold Ames—an old buddy from Cord’s early automobile days—was installed as company president.

For the next eight years, the HandyHot and HandyBreeze brands bounced back, and Cord—perhaps feeling redeemed—called it a day. He sold Chicago Electric MFG to the Hartford based Silex Corp., which kept the company as a subsidiary through 1956, with some manufacturing remaining in Chicago. In a typical big-fish-eats-small-fish chain reaction, Silex then merged with Philadelphia’s Proctor & Schwartz Electric Company in the 1960s to form Proctor-Silex, which, in turn, joined with the Hamilton Beach Co. under the banner of NACCO Industries in 1990. Basically, there is one company that makes small kitchen appliances now.

Meanwhile, E. L. Cord lived out his later years in predictably theatrical fashion, eventually becoming a state senator in Nevada in the 1950s—completing the classic American rise from race car driver to mogul to gangster to politician.

Oooh, the new soft shoe.

[Cord, center, meeting John F. Kennedy while serving as a Nevada state senator]

[Cord, center, meeting John F. Kennedy while serving as a Nevada state senator]

Sources:

Errett Lobban Cord: His Empire, His Motor Cars, by Griffith Borgeson

Flying the Line, by George Hopkins

Life, by Keith Richards

“Cord: A Different Roadability” – Second Chance Garage

“The Limousine Body Co.” – Coachbuilt.com

Archived Reader Comments:

“I remember this product! In 1955 in Texas I encountered a Handy-hot product. A miniature black HandyFan!! I REALLY wanted one! “—

“—

Hi, I just purchased a electric fireplace grate, with glass and electric lighting to imitate glowing coal embers, that looks like it had a heater at one time. Its marked with the Chicago Electric Mfg. CO. Do you have any knowledge of that part of the business?

Does anyone know where I can get an old Sunkist Juicer made by the Chicago Electric Mfg. Co. (Handyhot) repaired?

Anyone know how and when Harbor Freight got the Chicago Electric trademark?

I never realized there had been such a company.

I suspected HF chose the name becase it would remind customers of Chicago Pneumatic a well respected maker of air tools.

I found a mangled rusted Fan grill(front only) in a Arizona desert wash.IT was buried 2 feet deep Has the emblem Sterling Part no 2902 Blue color Chicago Electric.Did not find any info on this product. I also am a fan collector .

I have a Handybreeze fan cat. No. 3909

Chicago Electric Manufacturing Co. Can you give me any info on this as to year. Where this item may have been sold in Pa. or eastern state.

I just bought this fan at a garage sale. Wondering what it is worth. It still works. It’s in pretty good shape as well

Do you have any information on the Testall Electric Mfg. Co IGNI-TEST device? Thanks, Fred

I inherited a brand new, still-in-the-box Handyhot waffle iron (cat. no. 4602) complete with the tag attached. I think my grandmother must have acquired it around WW II. It’s very beautiful and interesting. Would be willing to donate to a museum.