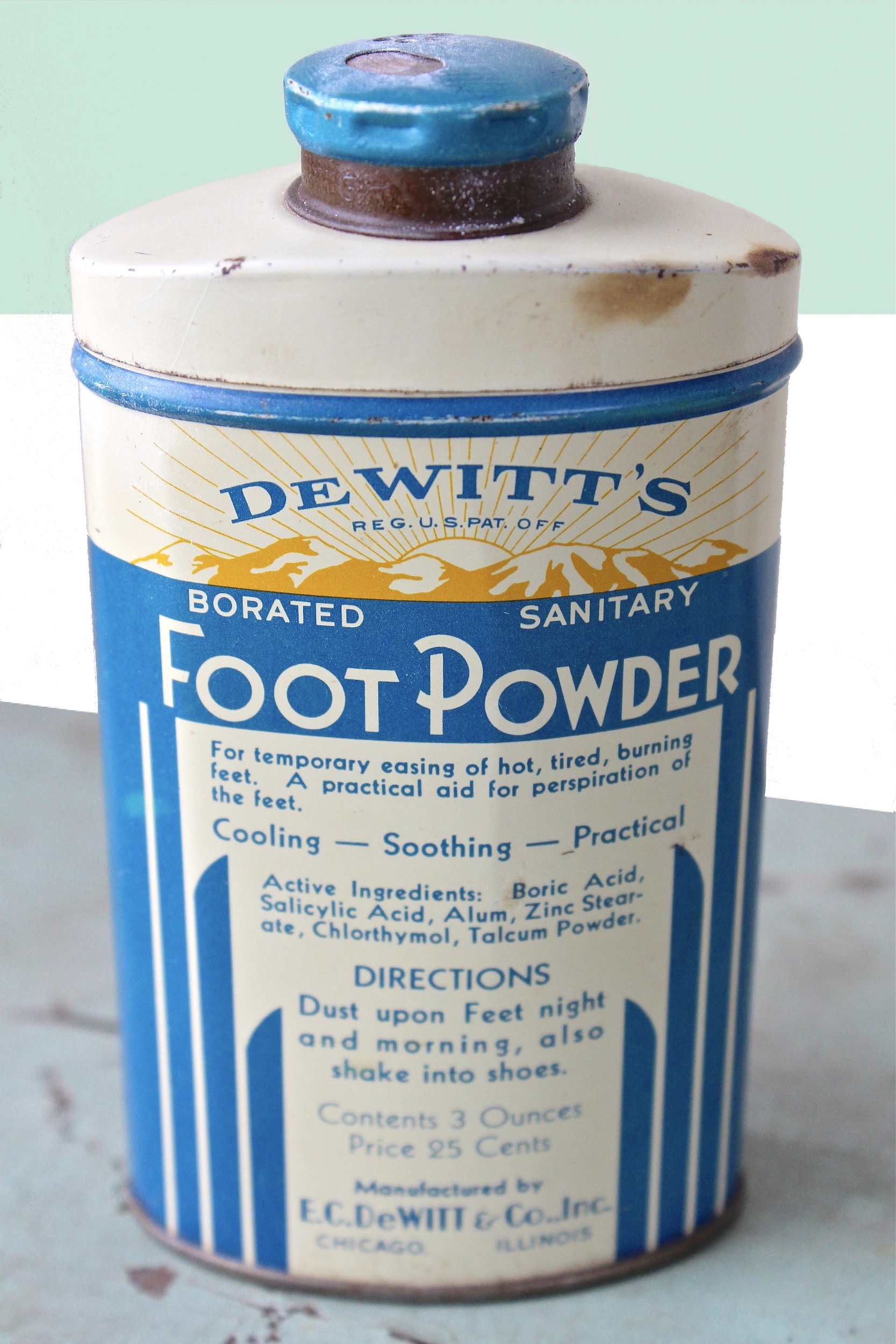

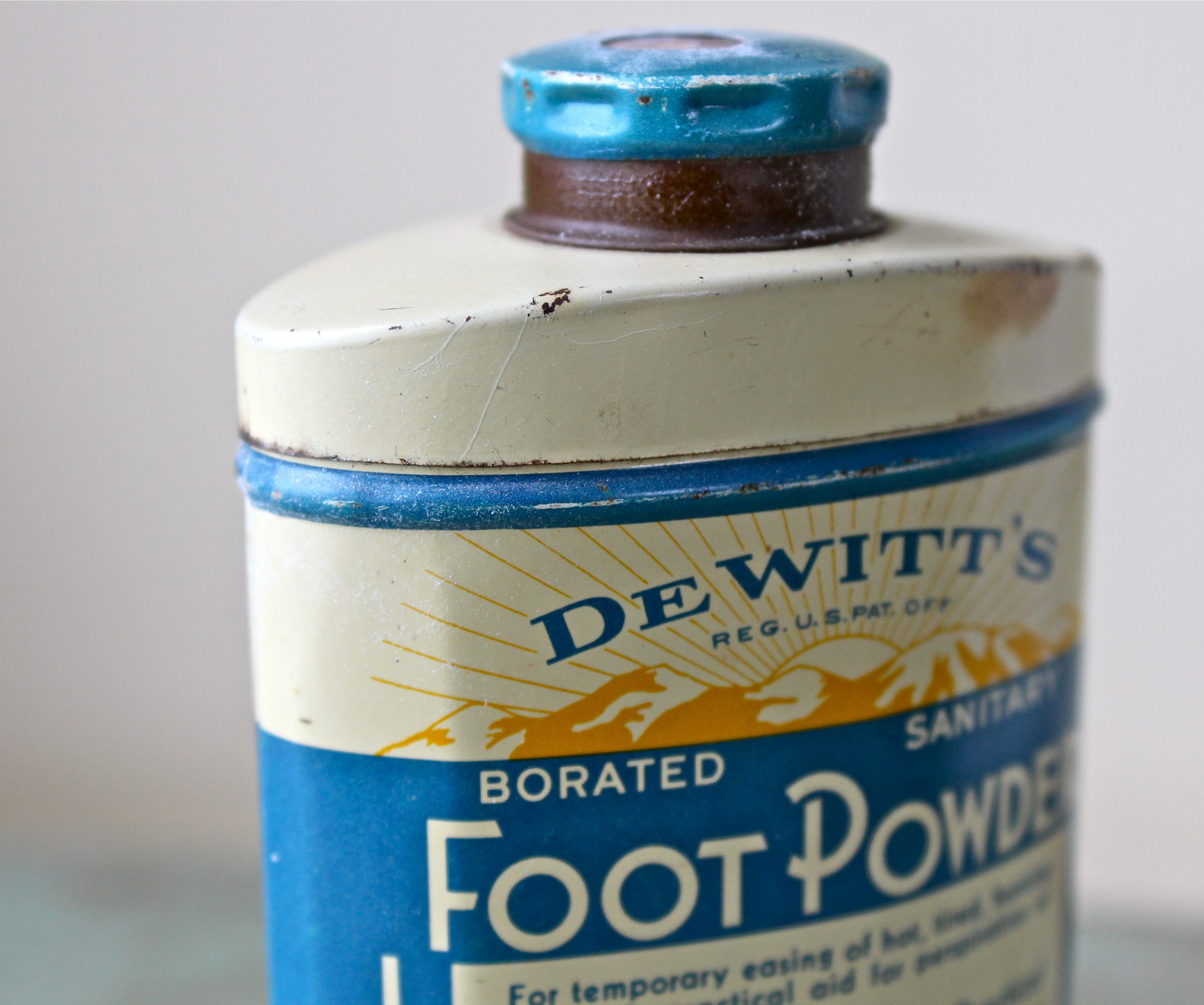

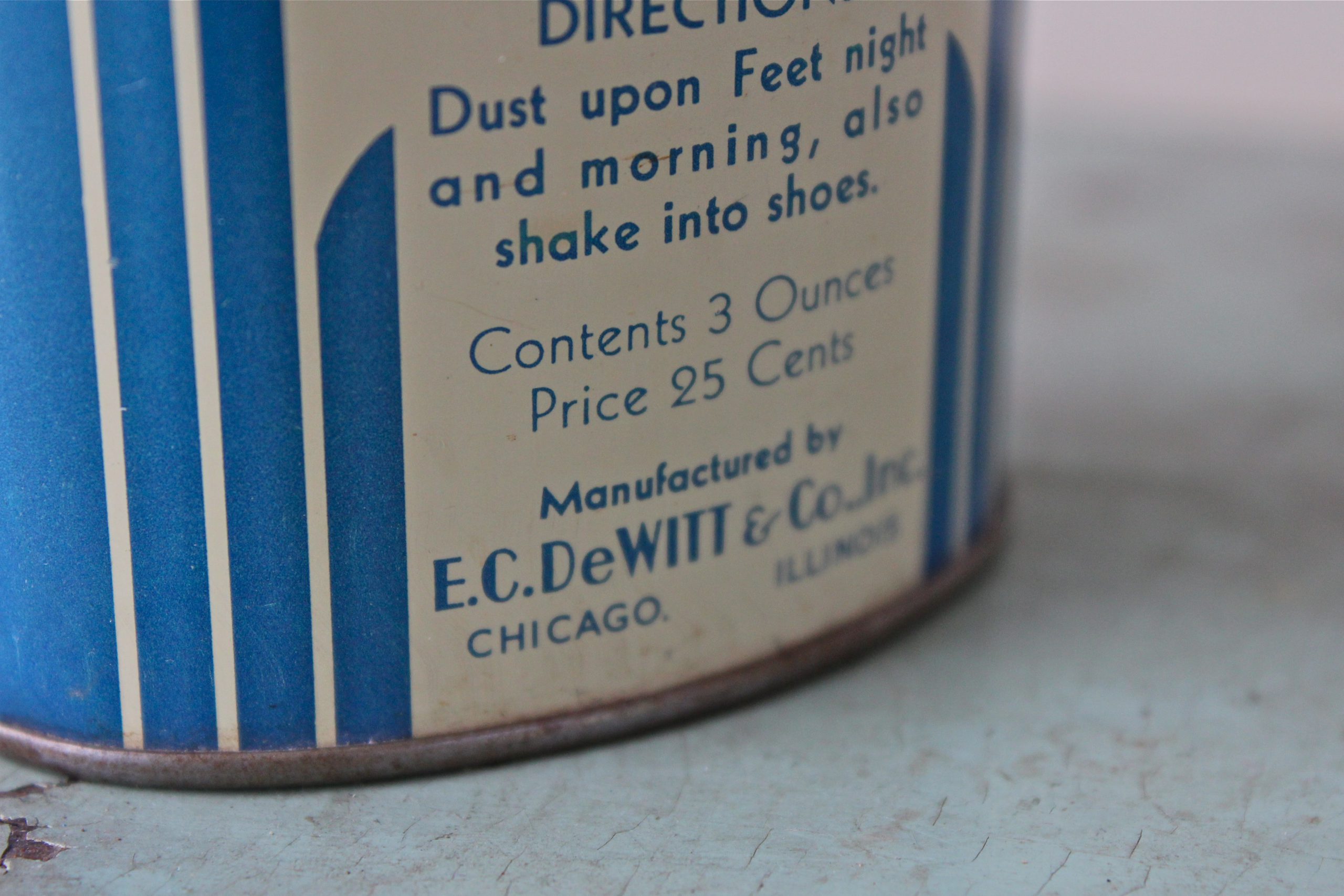

Museum Artifact: DeWitt’s Foot Powder, 1920s

Made By: E.C. DeWitt & Co., Inc., 1127 N. LaSalle St., Chicago, IL [Near North Side]

It probably wouldn’t be fair or accurate to call Elden C. DeWitt a “snake oil salesman.” For one thing, the guy’s been dead for nearly a century, so unless a secret diary surfaces, we’ll never know for sure if he genuinely believed in the quirky patent medicines he peddled. On top of that, the little we do know about the man paints a picture far more peculiar and colorful than your average, fly-by-night charlatan.

In the span of 50 years, DeWitt evolved from a lowly druggist hawking kidney pills in 1870s Dakota Territory to a multi-millionaire and international playboy—stretching his lavish lifestyle beyond the boundaries of logic or good taste, all while keeping an improbably low profile.

In the span of 50 years, DeWitt evolved from a lowly druggist hawking kidney pills in 1870s Dakota Territory to a multi-millionaire and international playboy—stretching his lavish lifestyle beyond the boundaries of logic or good taste, all while keeping an improbably low profile.

The few mentions of E.C. DeWitt in the Chicago Tribune archives (all occurring around the turn of the century) generally place him as part of the wealthy elite—a Lincoln Park Board member; a committee member for a swanky Marquette Club banquet at the Chicago Coliseum—but never the center of attention. It wasn’t until after his death in 1927, at age 72, that the spotlight really found him.

It started with a collective double-take at the value of the deceased’s estate: a staggering $20 million ($300 million in today’s money). “Wait, this is the same E.C. DeWitt that makes those bogus kidney pills?!”

Then came the lawsuit.

In perhaps the most bizarre, quintessentially Roaring ‘20s court case ever committed to the public record, a woman named Mae Brearton sued the estate of the late Mr. DeWitt for recurring payments never received. Her claim? Years earlier, she had allowed herself to be intentionally injected with syphilis germs by DeWitt—all as part of an agreement in which he would then use her as a paid guinea pig in his quest to cure the illness.

According to Brearton, DeWitt vowed to treat her condition and pay her $1,000 per month “for the rest of her natural life” as part of this contract. He had only completed five payments by the time he suffered a stroke in 1926, and now Brearton wanted the rest of her dough.

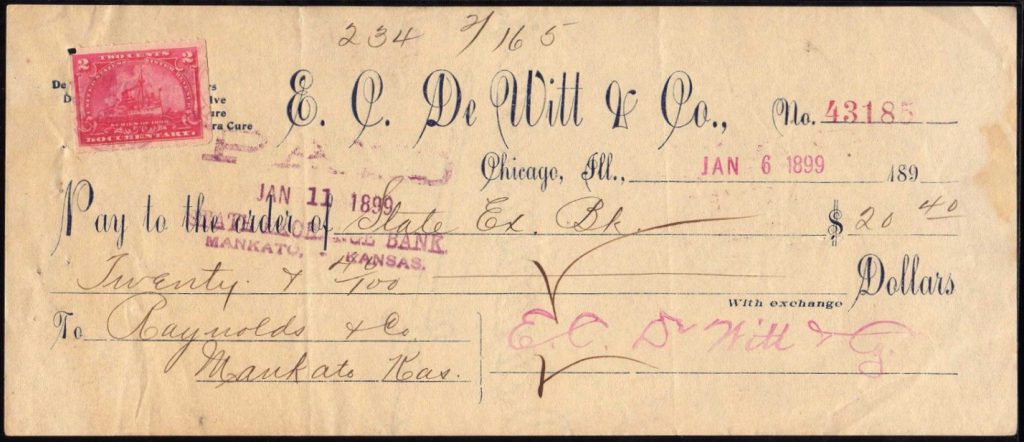

[A check signed by E.C. DeWitt in Chicago, long before his encounters with Mae Brearton]

[A check signed by E.C. DeWitt in Chicago, long before his encounters with Mae Brearton]

The 1930 case and the appeals that followed—while never front page news—make for a sort of absurdist theater, shining a whole new light on E.C. DeWitt and his later years as a philandering New York City high-roller. While the defense argued that Ms. Brearton had completely fabricated the whole story of the contract and the supposed injections, it was acknowledged by everyone that Mr. DeWitt had, in fact, given her a lot of money, and—more disturbingly—taken Brearton’s daughter Pearl as his mistress, setting up the girl in his Park Avenue loft with all the spoils she could ask for. That affair, however—as the defense explained it—was just a natural consequence of being a VIP in the big city.

“Mr. Elden C. De Witt was president of E.C. DeWitt Company, Inc., manufacturer of medicines, with offices in New York, Chicago, and London,” the defense brief read. “He was a man of large affairs and large means. From the record it must be inferred that he lived a fast life and this can not be lived without contact with fast women. Fast women are plentiful.”

“Mr. Elden C. De Witt was president of E.C. DeWitt Company, Inc., manufacturer of medicines, with offices in New York, Chicago, and London,” the defense brief read. “He was a man of large affairs and large means. From the record it must be inferred that he lived a fast life and this can not be lived without contact with fast women. Fast women are plentiful.”

While the defense painted Mae Brearton as a lying, greedy hanger-on—and someone who had annoyed Mr. DeWitt far more than she entertained him—the plaintiff’s team tried to use that argument towards their own cause. Since everyone agreed that DeWitt had given Brearton money on a few occasions, the question became, why?

“The motive sprang either from fear or affection or a sense of obligation,” they argued. “Counsel for respondents have definitely excluded the motive of fear. They point out that at times [DeWitt] ignored and defied [Brearton]. Just before he took her to Florida, that he despised and hated her. Upon their own reasoning, therefore, there remained but one motive for the conduct of Elden C. DeWitt toward this plaintiff. Unlovely to look upon as she was, rotten with disease as she was, there is but one explanation under the sun for the behavior of DeWitt toward her, and that is—HE OWED HER A DUTY.”

Ouch, that’s Mae Brearton’s own lawyers saying that stuff!

[E.C. DeWitt and his wife Cora, from their passport application photos. Cora had to endure the humiliation of the Mae Brearton trial after E.C.’s death]

[E.C. DeWitt and his wife Cora, from their passport application photos. Cora had to endure the humiliation of the Mae Brearton trial after E.C.’s death]

It proved to be all for not, too. The court threw out the case, largely because the supposed contract, if real, would have to be deemed void anyway, since DeWitt—as far as anyone could surmise—was not a licensed physician in the first place. “For DeWitt’s promise being illegal,” the court’s 1930 ruling read, “the contract was void.”

It seems unlikely the whole “syphilis contract” insanity actually went down, but if it did, it certainly opens the door to a flood of additional questions. Rather than selling snake oil, was E.C. DeWitt actually so confident in his untrained medical knowledge that he became more delusional than any of his customers?

It seems unlikely the whole “syphilis contract” insanity actually went down, but if it did, it certainly opens the door to a flood of additional questions. Rather than selling snake oil, was E.C. DeWitt actually so confident in his untrained medical knowledge that he became more delusional than any of his customers?

Beats me. But one thing that cannot be questioned is the success and scope of his business. Looking at our nice little art-deco DeWitt’s Foot Powder can, you’d never have reason to think it was anything but perfectly legitimate. “Cooling, Soothing, Practical,” the label says. And while it does contain a few ingredients that might be a tad controversial by modern standards, overall, it’s just a foot powder. Sprinkle it in your boots. S’all good.

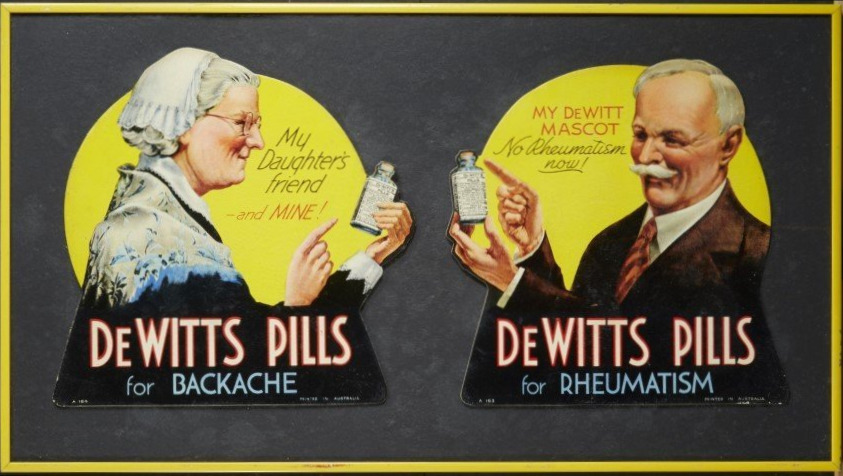

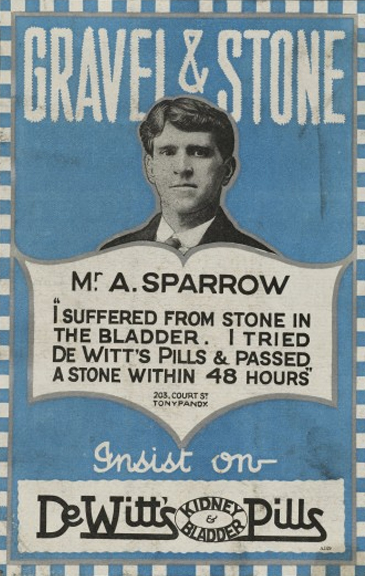

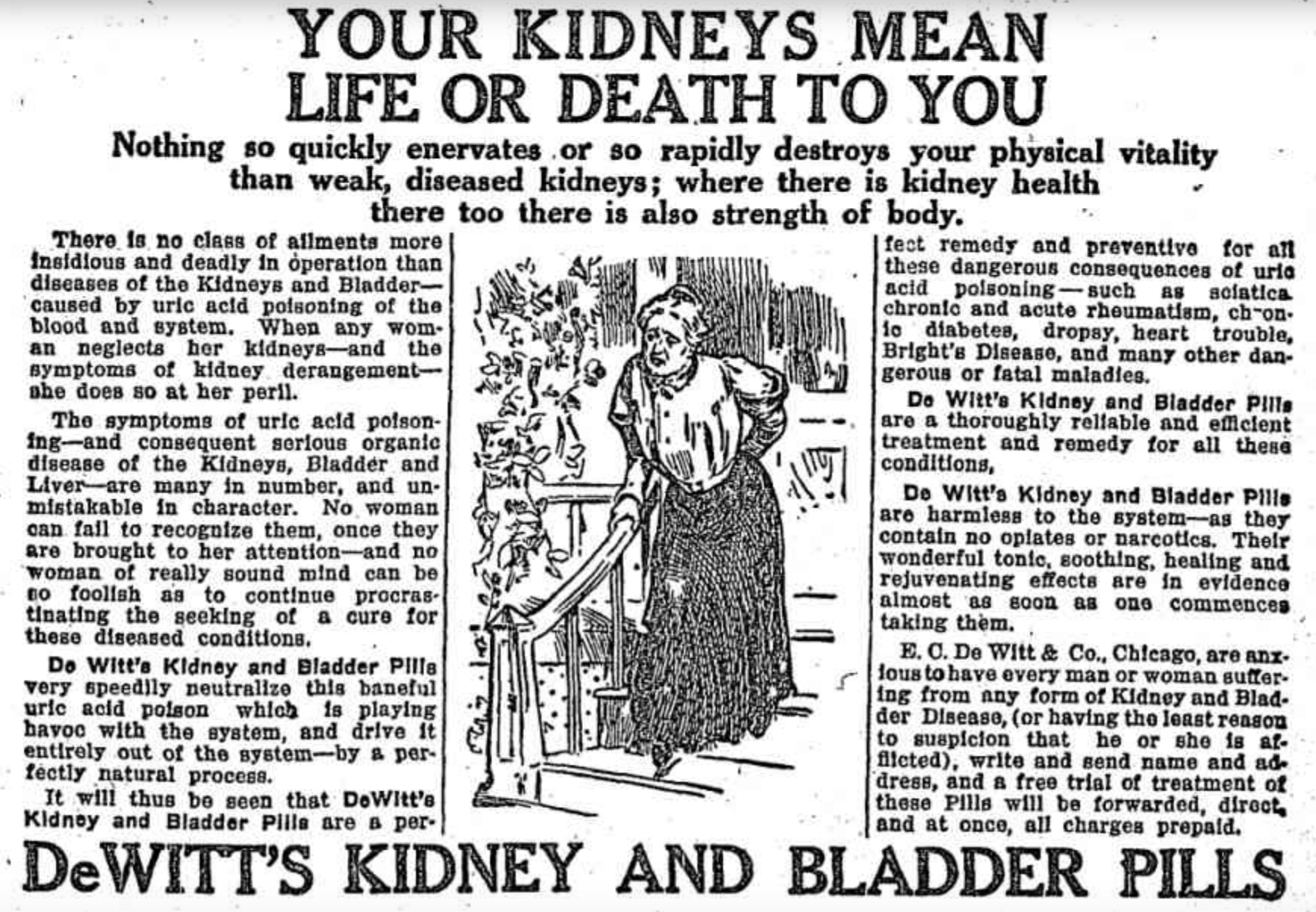

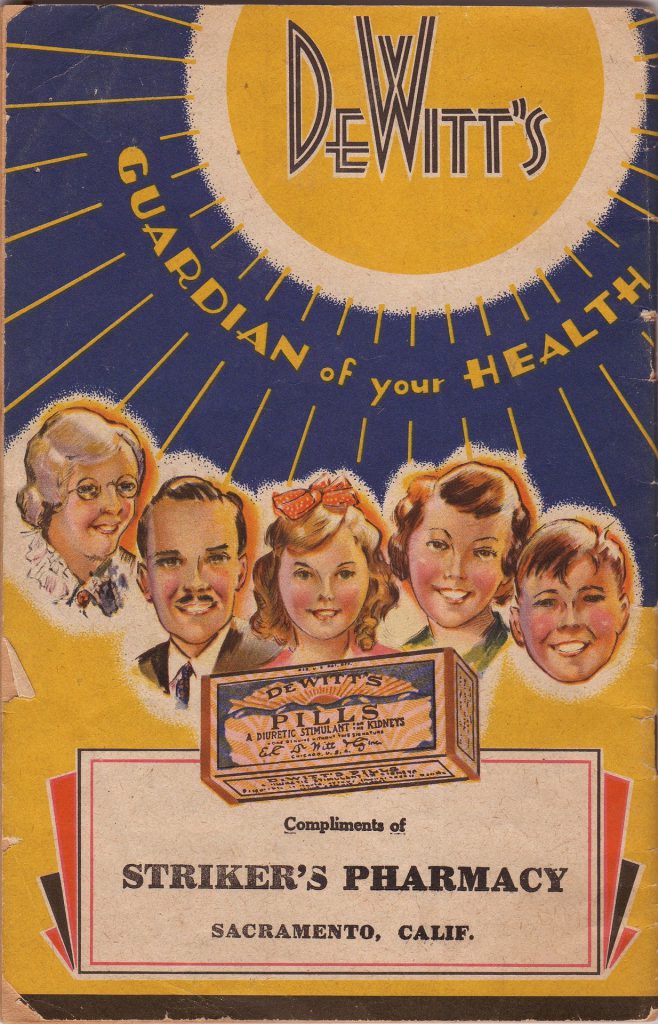

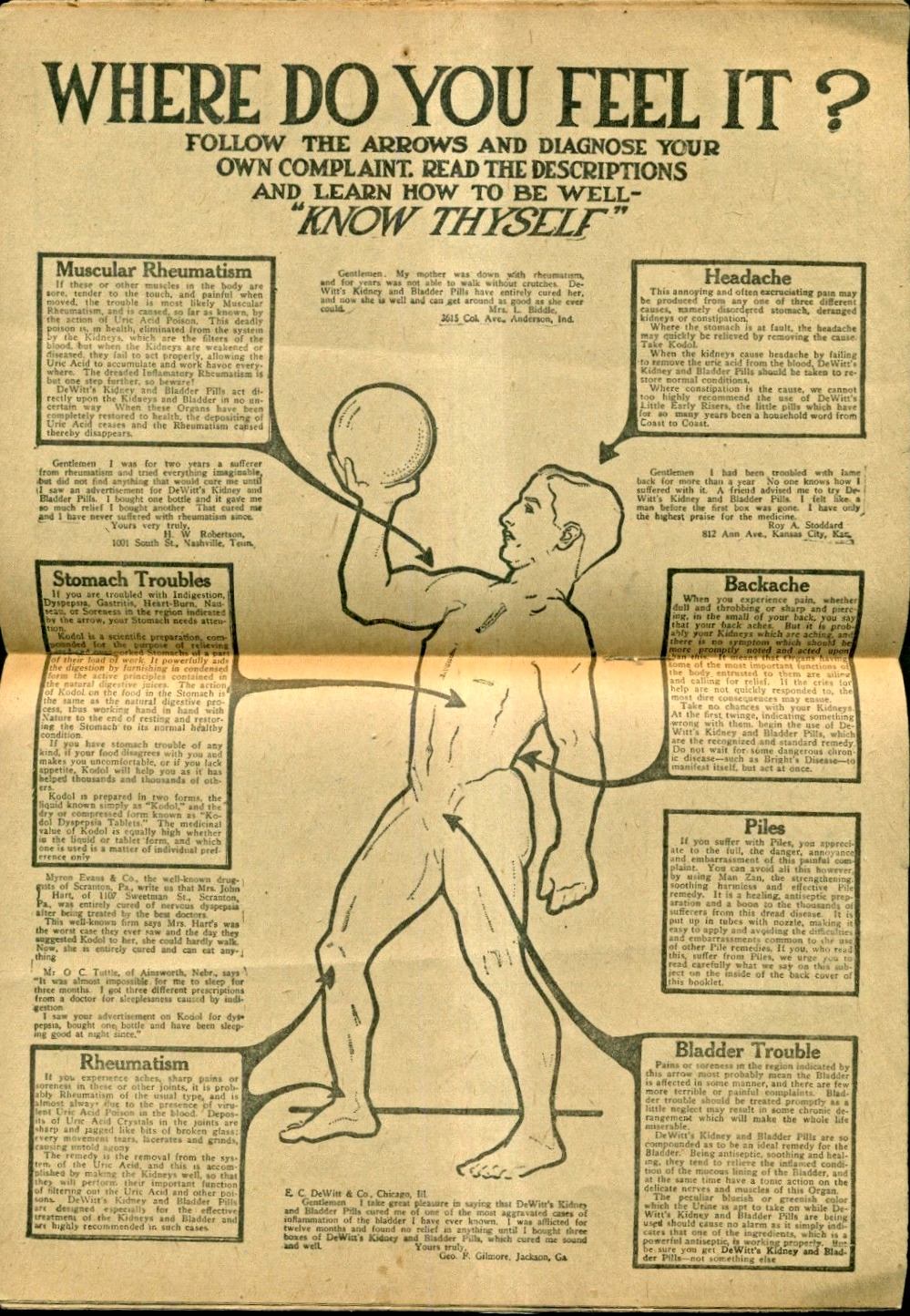

A wider examination of DeWitt’s 1910s/1920s patent drug line reveals some more hokey products with silly names, but nothing that seems stranger than you’d expect for the time: Dewitt’s Pills (“A Diuretic Stimulant for the Kidneys”), Kodol (for indigestion), ManZan (for hemorrhoids, aka, “piles”), Little Early Risers (laxative and cathartic liver pills), Nutos (for muscle pain), and DeWitt’s Hygienic Powder (“A Necessity for Woman’s Personal Cleanliness and Hygiene”), among others.

The “cure in a bottle” thing had been DeWitt’s stock and trade since his youth. He was born in the town of Wyoming, Iowa, in 1855, and by his early 20s, had already become a frontier druggist of sorts, setting up shop in the towns of Elk Point (South Dakota) and Sioux City before finally arriving in Chicago with his wife Cora in 1886.

DeWitt’s first patent medicine company had been a partnership with another former Dakota druggist named Charles W. Beggs. But in Chicago, the Biggs & DeWitt firm quickly was scrapped, and E.C. DeWitt & Co. was born.

The company found its footing largely through clever marketing, and the druggist and pharmaceutical publications of the day were more than happy to legitimize it with full-page DeWitt & Co. advertisements—not just for the company’s products, but their unusual co-op shareholding plans/schemes, as well.

It’s really only when you seek out the opinions of the actual medical establishment that you come to realize just how much of a divide there was between “real” science and the super-batty drug industry of the early 1900s.

The American Public Health Association, for example, believed that companies like DeWitt & Co. were selling “nostrums” that constituted a “grave menace to the public health.”

“Because of the deceptive advertising regularly employed in promoting their sale,” the Association claimed in 1915, “[patent medicines] consistently oppose the influences seeking to educate the public to a better understanding of the nature, causes, and proper treatment of disease. . . . The bulwark of this traffic is secrecy and mystery. . . . Be it resolved that the American Public Health Association opposes the sale of patent medicines and nostrums whose constituents are unknown to the health authorities.”

[DeWitt’s ad from a 1915 issue of the Chicago Tribune]

[DeWitt’s ad from a 1915 issue of the Chicago Tribune]

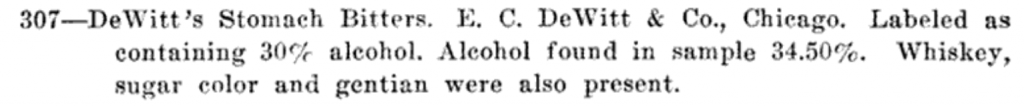

In 1916, Alma K. Johnson of the North Dakota Agricultural College conducted one of the most thorough analyses on record of the actual contents of various patent medicines on the market.

“Not all patent medicines are fakes,” he wrote, “but a large number of those that are extensively advertised and pushed are fakes of the worst kind. Seventy percent of the so-called patent medicines or nostrums found upon the shelves of the average drugstore are practically worthless or simply fakes and a means of drawing money from suffering humanity without giving any real benefit. . . . There is no sure ‘cure-all’ or ‘shot gun remedy,’ and there are many diseases that are recognized by our best physicians as being, so far as any known medicine is concerned, incurable. So why do we expect that some ignorant vendor of drugs, some unsuccessful horse doctor, or a quack, should make a discovery that is going to prove a ‘cure-all’ for suffering humanity?”

In that same publication, Johnson goes on to assess scores of nostrums, including some from E.C. DeWitt & Co.

Since many medical professionals were citing the high alcohol content in some nostrums as a contributor to a new rise in alcohol addiction, this wasn’t a real good look for DeWitt. Products like the DeWitt “One Minute Cough Cure” were problematic, too, as the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 had prevented the use of the word “cure” and other bogus terms on patent drugs, sending the industry scurrying for new methods of BS.

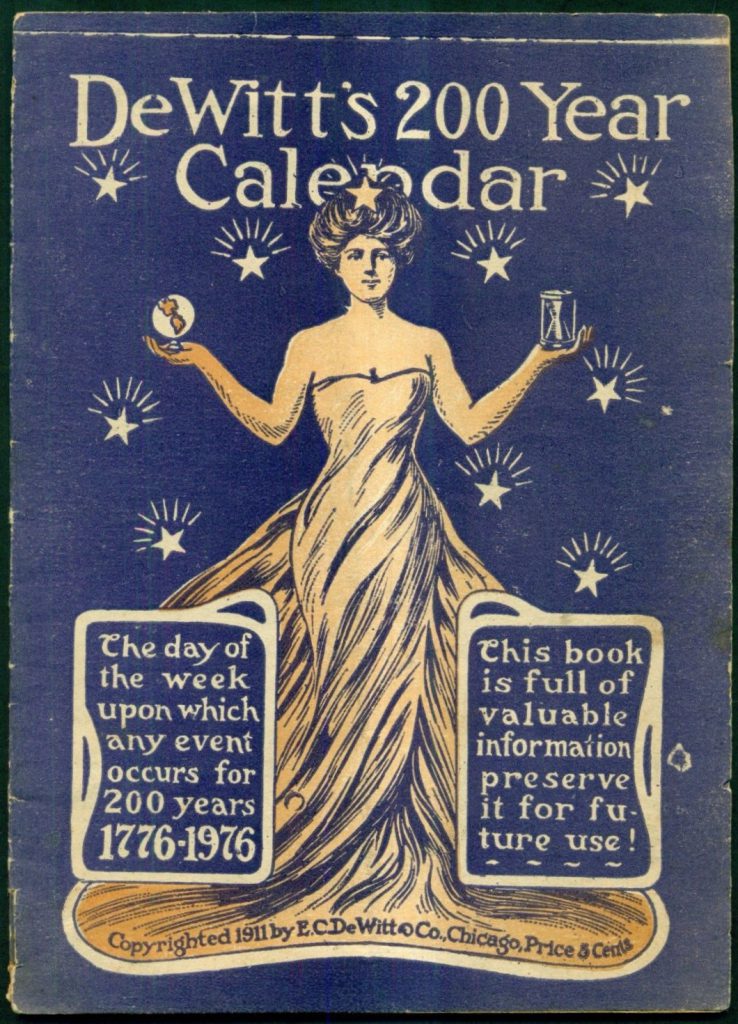

Even DeWitt’s “fun” marketing campaigns—while highly successful in their time—have a bit of a dubious element to them. For example, one of the company’s big annual promotional tools was a booklet called “DeWitt’s 200 Year Calendar and Book of Horoscopes,” which used what they described as “the art or science of Astrology” to woo people into buying a 30-page advertisement for DeWitt drugs.

If your target audience believes that events decades in the future can be predicted by the star charts inside a drug store flyer, you just might be seeking to take advantage of those same people’s belief in magic medicines (no offense to the horoscope lovers out there).

In any case, the E.C. DeWitt & Co. business didn’t end with E.C. DeWitt’s death. Far from it. The humble little drug company—which opened its first big five-story headquarters on LaSalle Street in 1897—had become an unlikely international powerhouse. Along with its offices in New York and London, the “DeWitt International Corp.” eventually came to settle in South Carolina, with pharma satellites in the UK and Australia later in the 20th century. It wasn’t until 1986 that the Church & Dwight Company, a New Jersey based soap and detergent manufacturer, finally bought out the American brand of DeWitt’s—about 100 years after the whole thing started way out in a lonesome South Dakota drug store.

Postscript: Weirdly, you can still find the DeWitt’s name on some 21st century pain medications produced by the Lee Pharmaceutical Co. in China, but that’s likely a case of cashing in on an expired copyright and subliminal familiarity.

Archived Reader Comments:

“I wish you could still buy DeWitt’s oil for ear use. I have no idea what was in that stuff, it could have been used motor oil for all I care. It worked great. Had a bad case of swimmer’s ear as a kid and could not afford to go to the Dr. The oil made my ear feel better and the infection cleared up in a few days after I started using it.” –Ed Bowden, 2020

“Thank you. DeWitt was my great great uncle. I have recently started doing research on my ancestry and this article has been entertaining and illuminating. Its fun to come across a character as interesting as Elden from a family history of largely Iowa farmers. The fact that some of his patent medicines contained 60 proof alcohol makes me wonder if some his sales were fueled by prohibition? Maybe even out the back door. $300 million is a lotta’ liver pills! Thanks again! ” –Lloyd Hauskins, 2019

I used to buy the the kidney and bladder pills for water retention back in the 80s. They actually did work, and also contained methylene blue which now is being prescribed for all the ailments stated the box.

Apologies in advance for a long comment–your article has been very useful for me! I was wondering if y’alI know or have any information that could further help me with dating an item i have.

I have a bottle of DeWitt’s Baby Cough Syrup, cardboard sleeve and product brochure included. Other DeWitt’s Baby Cough Syrup bottles I have found in museum collections or on eBay look nothing like it; the colours and branding are completely different. Currently, I don’t even know the range that DeWitt’s was producing Baby Cough Syrup.

At time of writing, I’ve narrowed down the date range of my bottle to 1954-1978. TPQ is 1954 because of the particular iteration of Owens-Illinois Glass Company maker’s mark on the base of the bottle. The 1978 cutoff is because on the bottle and cardboard sleeve, there is a badge touting how it was featured in Parents’ Magazine. Parents’ Magazine’s name was changed to “Parents” in 1978.

Something that seems important–on the product brochure, the address of DeWitt’s is “2835 Sheffield Ave. Chicago 14, Illinois”. Another commenter on this article mentioned their husband working at that location in the 60’s.

Thank you much for your time and patience. Feel free to email me if you feel inclined–no worries if not, I don’t wish to be a bother.

E C DeWitt was the uncle of a friend of ours. His aunt Flora came to visit in 1955 and spent 3 months with them. I was a little girl and just loved his aunt whose last name was Bell. So I would walk up to her and say hi Aunt Bell and pretend to ring a bell. She was lovely. I’ve been trying to figure out what the company was for years and put it together today. Thank you for the article.

i have DeWitts merthiolate tincture great antiseptic solution that is no longer sold thanks

My name is Jim Treme.I was a salesman for Dewitt.My territory was North Carolina, South Carolina,Georgia,,and Florida.I started in 1982 and left when they were selling out to Church and Dwight. What a wonderful experience it was .It definitely was a throwback to earlier days where I flipped my black case with the products inbedded in Styrofoam .I went from town to town opening new accounts and servicing the existing accounts.We had creosant cough syrup,Penguin Foot Creme,Dewitt Antacid Powder, and the list goes on. Love every minute of it.

I have one share of capital stock of the E.C. DeWitt Co. Inc. dated Sep. 27, 1945. Anyone interested?

I have with me one bottle of de witts Kidney and bladder pills. I have taken the images both sides but it appears there is no provision for attachting the images.

This is absolutely mesmerizing!! It’s so cool to go back in time and see all these pills and powders that were made right here in Chicago! And the alcohol content was even more bizarre! It could probably knock you right on your rear end if you took too much too soon! By making you woozy, one would forget all about the aches and pains and just pass out!!

My husband worked for E.C. DeWitt in Chicago on Sheffield Ave in the 60’s and then they moved to Taylors, S.C. on Watson Rd. He moved down here and worked for them. When the company was sold to Church and Dwight he stayed on when them. My husband has since passed away and I have old pictures of the plant that was in Chicago and also the old hand seals and old weight machine, and a bottle of kidney pills..

Thanks, Bernadette. We’d welcome you to share any stories about your husband’s time with DeWitt. If you wanted to send digital versions of those photos of the Chicago plant, that would be wonderful, too. You can reach us at contact@madeinchicagomuseum.com

I found a bottle of DeWitt ear wax remover in my 90 year old Mother’s medicine cabinet! Did a search and found your site. Thanks for the interesting information!

I found two little balls of the what little early riser. And a little kidney pills it’s a little cork tops in it. Never seen quite anything like it. I wish I could send you a picture. Do you have any input ones are red label and ones are green label has a signature on it

I worked at the Sheffield Ave plant office from 1954 to 1956 as Head bookkeeper acct…enjoyed my last job in Chicago….never knew the history until now….

I’m still going strong after 98 years…..maybe after using their products!!!!!