Museum Artifact: Pulvex Products – Flea & Lice Powder, Analgesic Tablets, and Kitty & Cat Flea Powder, 1930-1960

Made By: William Cooper & Nephews Inc., 1909 N. Clifton Ave., Chicago, IL [Lincoln Park]

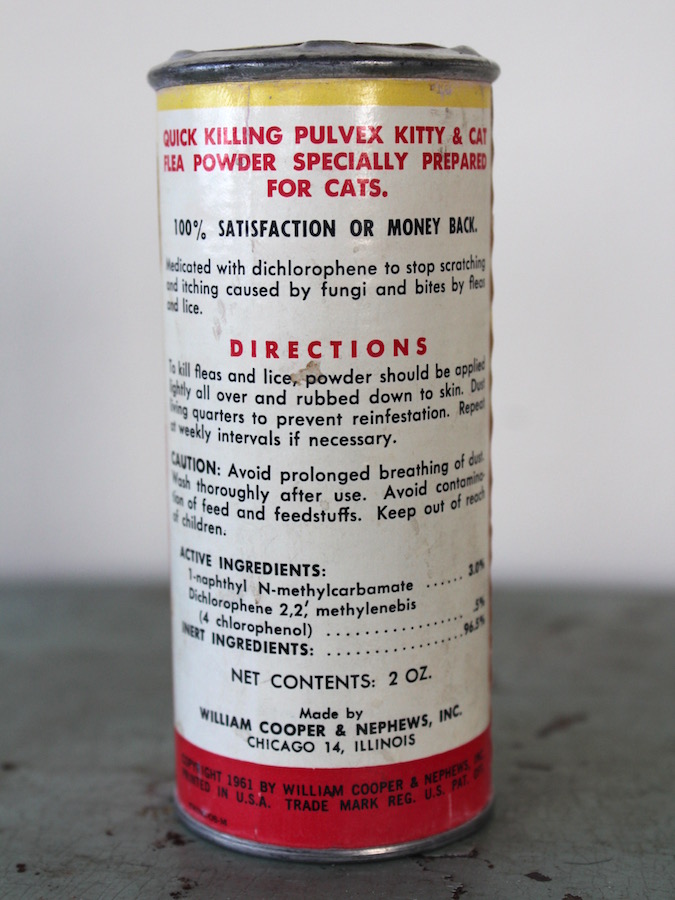

You might not guess it by looking at the cutesy packaging, but the 1961 bottle of Pulvex “Kitty & Cat Flea Powder” pictured above represents an important crossroads in the history of pet-care pesticides.

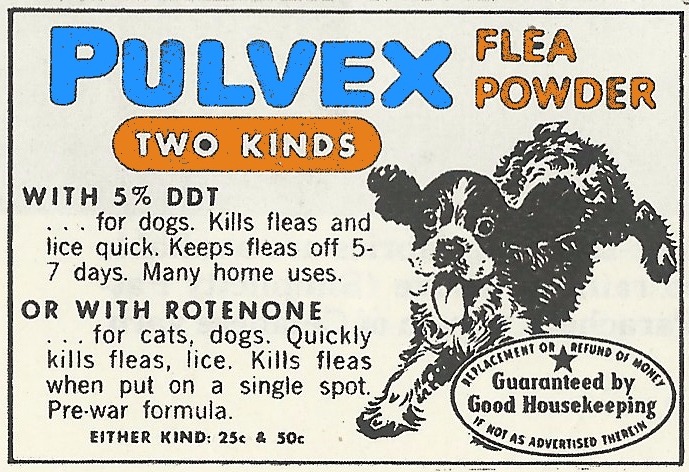

Up through the Second World War, most commercial flea powders in the U.S. were approved for use on both dogs and cats—Felix and Fido could share their itch meds. But when a certain super-powerful bug destroyer called DDT was added to many of these formulas in the late 1940s, the new treatments were soon deemed a tad too dangerous for smaller dogs and just about any size cat (kitties clearly included). Hence, pet owners looking to treat a flea-ridden feline in the Mad Men era were now left to seek out an alternative product. It was provided, in this case, by a company called William Cooper & Nephews Inc.—a British invader into the Chicago industrial landscape, and one of the world’s great innovators of animal cleansing remedies.

Up through the Second World War, most commercial flea powders in the U.S. were approved for use on both dogs and cats—Felix and Fido could share their itch meds. But when a certain super-powerful bug destroyer called DDT was added to many of these formulas in the late 1940s, the new treatments were soon deemed a tad too dangerous for smaller dogs and just about any size cat (kitties clearly included). Hence, pet owners looking to treat a flea-ridden feline in the Mad Men era were now left to seek out an alternative product. It was provided, in this case, by a company called William Cooper & Nephews Inc.—a British invader into the Chicago industrial landscape, and one of the world’s great innovators of animal cleansing remedies.

By this point in time, Wm. Cooper & Nephews already had an accomplished history and an international brand dating back nearly 120 years. Unlike most of the companies represented in the Made In Chicago Museum, however, it hadn’t required the Windy City’s magic touch to fuel its formative years. In fact, William Cooper himself was already long in the grave when the business bearing his name first arrived on the shores of Lake Michigan. They didn’t come seeking religious freedom either—this was a purely imperialistic mission.

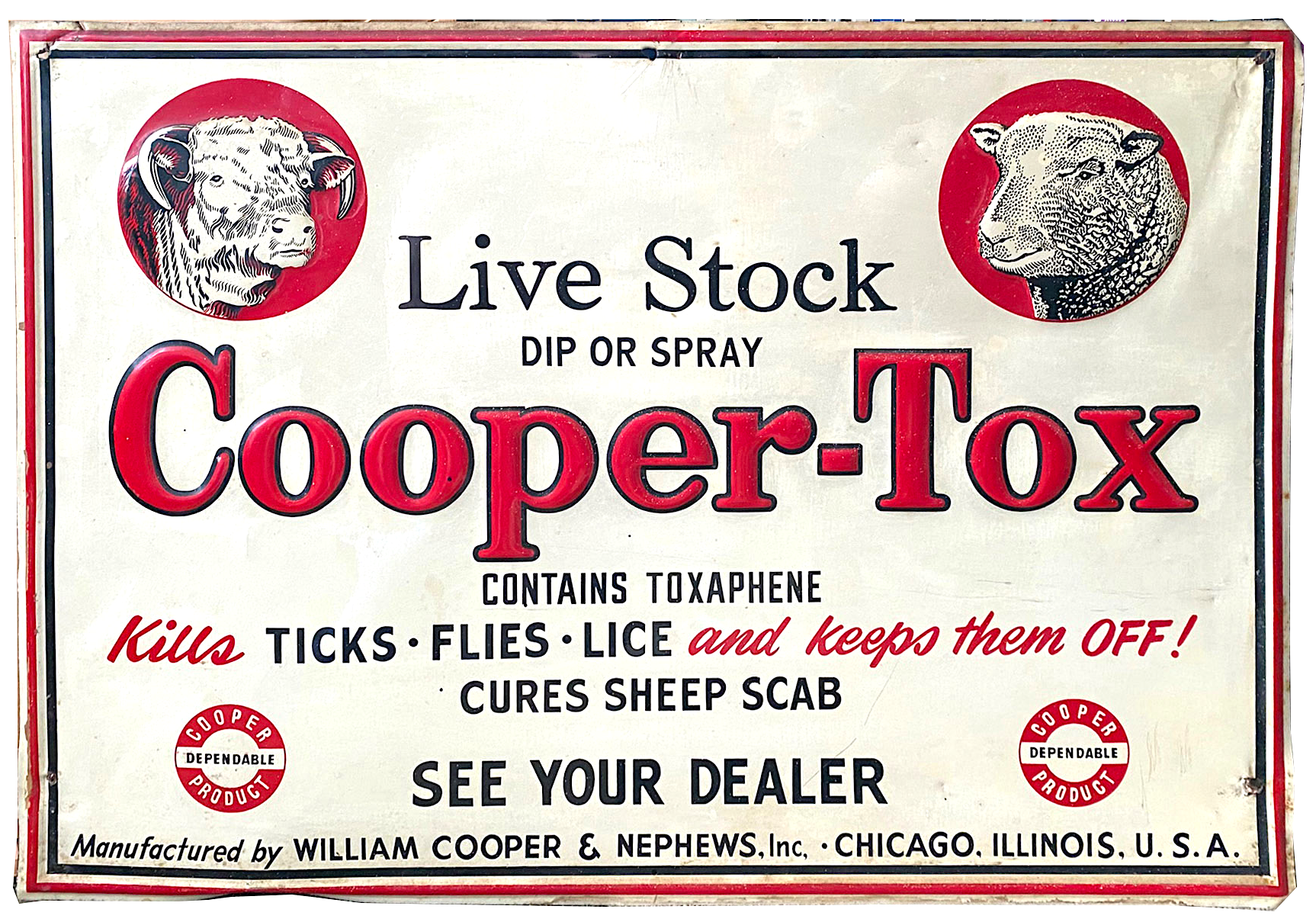

[Large Cooper-Tox advertising sign, circa 1960, donated to the Made in Chicago Museum by Hal Bowman]

History of William Cooper & Nephews, Part I: Wooly Origins

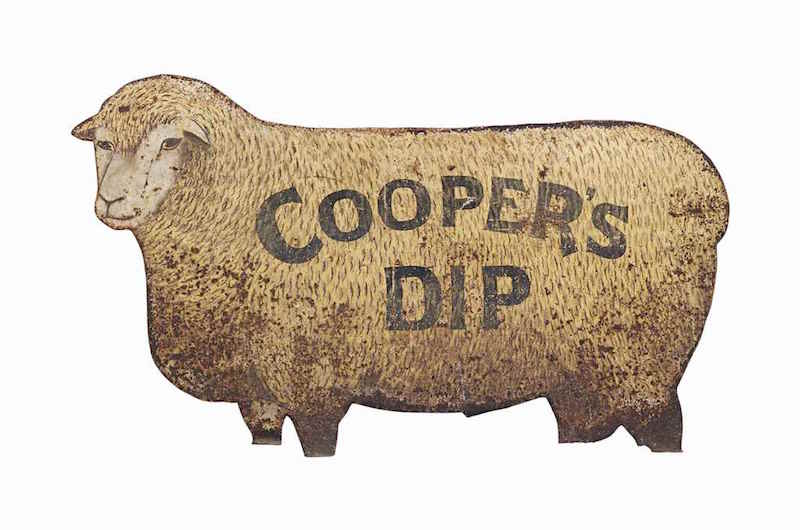

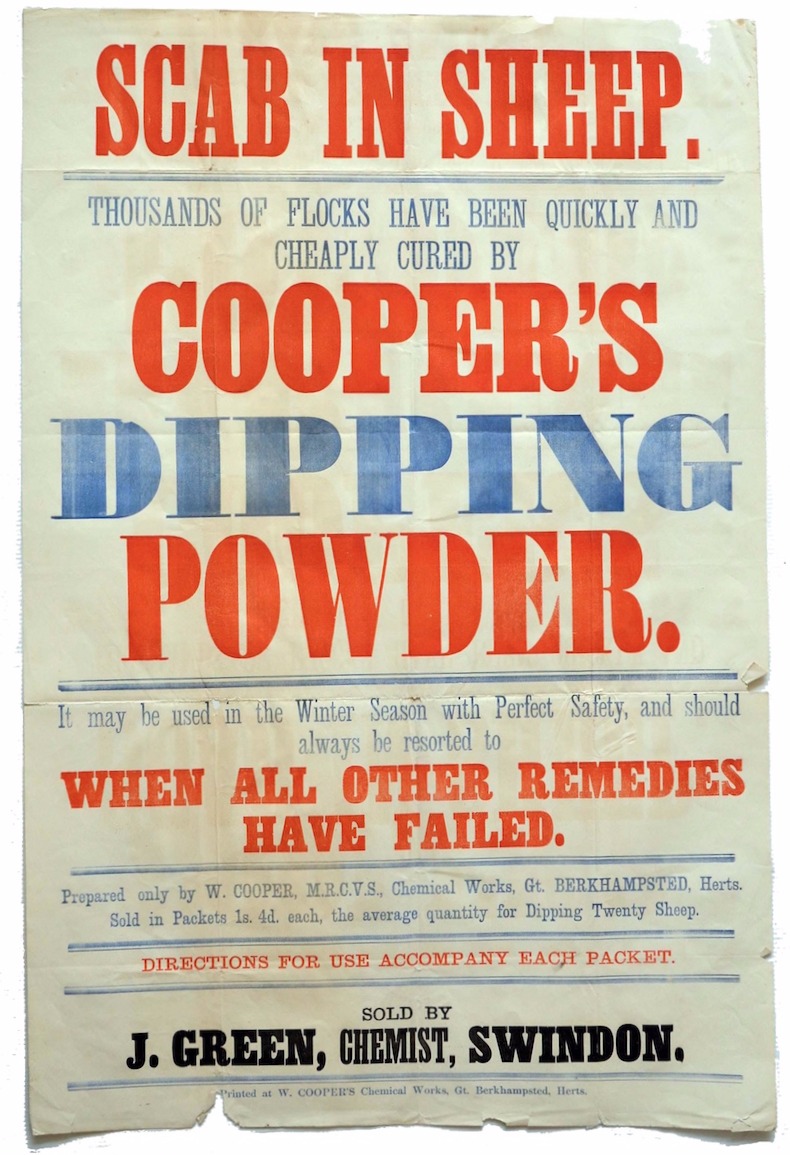

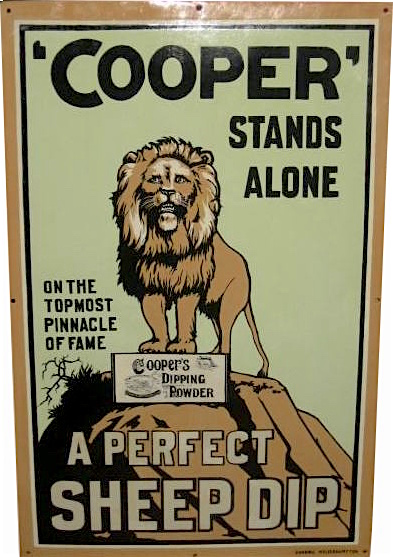

Way baaack in 1843, the original William Cooper—a young veterinary surgeon in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire, England—developed a new chemical preparation for treating the rampant skin diseases affecting the country’s sheep population. Bugs and parasites were decimating the animals and ruining the local wool business, so Cooper came up with a special “dip” that farmers could mix with cold water and douse their flocks in—magically solving the problem. Arsenic and sulfur were involved, regulations were sketchy, results—more importantly—were excellent. Cooper’s “Sheep Dipping Powder” became the great granddaddy of our eventual Kitty & Cat concoction.

From the first packaging of Cooper’s Sheep Dip up until its creator’s death in 1885, the business known as William Cooper & Nephews earned its keep as a massively successful UK pesticide supplier.

From the first packaging of Cooper’s Sheep Dip up until its creator’s death in 1885, the business known as William Cooper & Nephews earned its keep as a massively successful UK pesticide supplier.

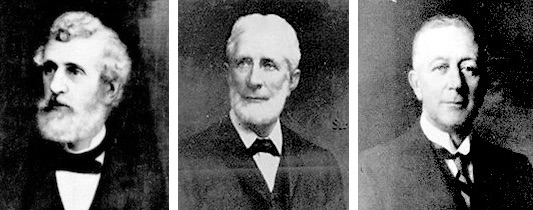

Of the “nephews” in question, Richard Powell Cooper (born, 1848) became the most crucial—taking the reins after his uncle and older brother kicked the bucket. Along with having his own formal training in veterinary surgery, R. P. Cooper was a well-to-do Brit in Victorian times, so he knew that any empire was only as good as its long range reach. With this in mind, he pushed full steam ahead into the global market, targeting Australia, South Africa, South America, and of course, the USA.

[Three generations of Coopers, from left to right: William Cooper, his nephew Richard Powell Cooper, and grand-nephew Richard Ashmole Cooper]

[Three generations of Coopers, from left to right: William Cooper, his nephew Richard Powell Cooper, and grand-nephew Richard Ashmole Cooper]

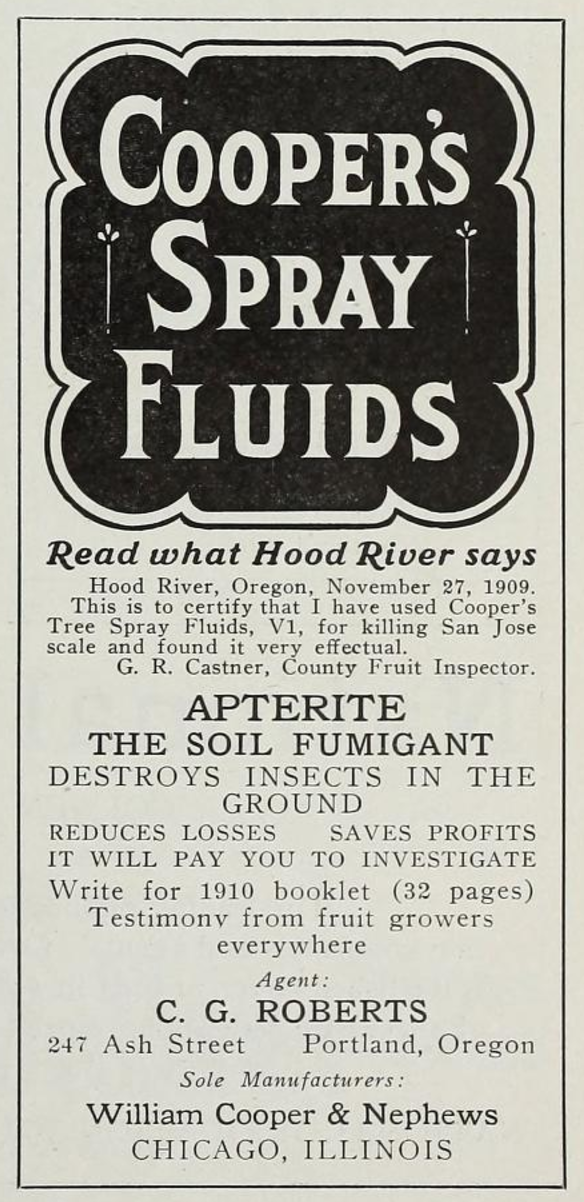

In 1890, Richard P. Cooper dispatched 30 year-old Charles Timson—an employee of Wm. Cooper & Nephews since his teenage years—to Galveston, Texas, where he’d open the company’s first American sales office. A few years later, Timson made his way to Chicago for the 1893 World’s Fair, showcasing all the latest and greatest bug-killing potions coming out of the old country. The Chemist and Druggist, an industry periodical, covered the Cooper exhibit in a November, 1893 issue.

“One of the attractive features of the Fair during the latter months, writes a correspondent, was the exhibit made by Messrs. William Cooper & Nephews, of Berkhampstead [sic] England, and Galveston, Texas. Their exhibit was not put in place until the very end of July, as it was associated with the live-stock exhibit, which did not begin until then. Mr. C. Timson, the manager of the firm’s American business, had a splendid display of his firm’s goods, and it was made doubly interesting by an exhibit of wools of different classes treated with various dips, to show the different effects of leading dips upon the fibre. Under the microscope, living insects—such as the tick, scab-parasite, etc.—were shown. Also in connection with the live-stock exhibition, Messrs. William Cooper & Nephews presented for competition prizes amounting to $750 for the best results in treating sheep with the dip. The prizes included a number of handsome silver cups, and the competition created much interest among stock-rearers.”

“One of the attractive features of the Fair during the latter months, writes a correspondent, was the exhibit made by Messrs. William Cooper & Nephews, of Berkhampstead [sic] England, and Galveston, Texas. Their exhibit was not put in place until the very end of July, as it was associated with the live-stock exhibit, which did not begin until then. Mr. C. Timson, the manager of the firm’s American business, had a splendid display of his firm’s goods, and it was made doubly interesting by an exhibit of wools of different classes treated with various dips, to show the different effects of leading dips upon the fibre. Under the microscope, living insects—such as the tick, scab-parasite, etc.—were shown. Also in connection with the live-stock exhibition, Messrs. William Cooper & Nephews presented for competition prizes amounting to $750 for the best results in treating sheep with the dip. The prizes included a number of handsome silver cups, and the competition created much interest among stock-rearers.”

A couple other fellows who took notice of the Cooper exhibit were John K. Stewart and Thomas J. Clark—a pair of 23 year-old entrepreneurs who’d just launched their own horse-clipper and sheep-shearer manufacturing business: the Chicago Flexible Shaft Co.

II. I Dip, You Dip, We Dip

Stewart and Clark were transplanted New Englanders, which wasn’t the same as being from old England, but they spoke Charles Timson’s language, nonetheless. The groundwork was thus laid for a high-stakes new business partnership—just one of several noteworthy alliances in John K. Stewart’s short but impactful time as a Chicago industrialist.

While William Cooper and Nephews had been affiliated with the clipper products of London’s Wolseley Sheep Shearing Machine Co. through much of the 1890s, Charles Timson finally jumped in with John Stewart at the dawn of the new century, moving to Chicago and co-founding the Cooper-Stewart Sheep Shearing Machinery Co.—an international marketing wing for the Chicago Flexible Shaft Company. Now, Britain’s trusted name in sheep dips was in lockstep with America’s hip new brand of sheep trimmers. It was dream team of shepherding.

While William Cooper and Nephews had been affiliated with the clipper products of London’s Wolseley Sheep Shearing Machine Co. through much of the 1890s, Charles Timson finally jumped in with John Stewart at the dawn of the new century, moving to Chicago and co-founding the Cooper-Stewart Sheep Shearing Machinery Co.—an international marketing wing for the Chicago Flexible Shaft Company. Now, Britain’s trusted name in sheep dips was in lockstep with America’s hip new brand of sheep trimmers. It was dream team of shepherding.

By 1904, Charles Timson and his son Charles Jr. had also acquired 50% interest in the Chicago Flexible Shaft Company itself. This investment quickly put Stewart’s sheep shearers into barns around the globe while loading the pockets of everyone involved.

Even so, the young Americans Stewart and Clark weren’t content to be in the sheep business forever. They were both enticed by the comparative glamour of America’s newest million-dollar industry—automobiles—and soon launched another company, the Stewart & Clark MFG Co. (aka Sterk MFG Co.), to focus on making car parts. This firm would eventually evolve into yet another Chicago industrial giant, the Stewart-Warner Corporation.

Unfortunately, Tom Clark wouldn’t see the new effort come to fruition. He died in a motor crash in 1907 while showing off the Stewart & Clark speedometer on the Glidden racing tour. He was only 38.

Heartbroken by his buddy’s death but now fully focused on their auto-parts vision, John K. Stewart sold the remaining 50% of the Chicago Flexible Shaft Company to the Timsons in 1908, making it an official subsidiary of our flea powder friends, William Cooper & Nephews. A new WC&N manufacturing facility was also established in Chicago, taking over the plant of F. S. Burch & Co.—known for producing the identification tags used on farm animals.

Heartbroken by his buddy’s death but now fully focused on their auto-parts vision, John K. Stewart sold the remaining 50% of the Chicago Flexible Shaft Company to the Timsons in 1908, making it an official subsidiary of our flea powder friends, William Cooper & Nephews. A new WC&N manufacturing facility was also established in Chicago, taking over the plant of F. S. Burch & Co.—known for producing the identification tags used on farm animals.

Now, as the preeminent force in sheep shearing, sheep tagging, AND sheep dipping, Wm. Cooper & Nephews was the bellwether of the flock—a true corporate beast of early 20th century agriculture.

[President William Howard Taft watching the cattle on his Texas ranch receive a dip in Cooper’s Tixol “tick destroyer and mange cure,” 1909. Original photo donated by Hal Bowman]

III. Missed Opportunities

In 1913, just as their empire was shaping into form, Wm. Cooper & Nephews lost its fearless leader, as the last of the original nephews—Richard Powell Cooper—died at 65. His son Richard Ashmole Cooper took over the business, and Charles Timson Sr. was summoned back to England to serve as CEO, with Chuck Jr. left to run the show in the States. A year later, a new Cooper plant was opened in Chicago at 152 W. Huron St. [another facility supposedly existed on N. Winchester Ave., but info remains scant].

By putting together a top-flight research department, William Cooper & Nephews stayed at the forefront of new advances in chemistry and technology, honoring the science-begets-business philosophy of its founder. A few uncharacteristically short-sighted business decisions, however, did put some dents in the Cooper armor, leaving some sizable consequences down the road.

By putting together a top-flight research department, William Cooper & Nephews stayed at the forefront of new advances in chemistry and technology, honoring the science-begets-business philosophy of its founder. A few uncharacteristically short-sighted business decisions, however, did put some dents in the Cooper armor, leaving some sizable consequences down the road.

For one thing, the Brits had failed to take up John K. Stewart on an early offer to invest in his automobile speedometer invention back in 1906. The Timsons felt it was a risk too far outside the established Cooper & Nephews comfort zone (i.e., sheep). Two years later, Stewart speedometers were being installed in every Ford Model T.

During the 1910s, Stewart’s nephew L.H. LaChance took over the presidency of the Chicago Flexible Shaft Company [gee, nephews were really on a hot streak with this firm] and began rolling out a new line of electric household appliances—soon to be sold under the famous “Sunbeam” brand name. Once again, though, ownership overseas didn’t seem to fully appreciate the lucrative potential of this venture. By the 1920s, LaChance had left to join the Stewart-Warner Corp., and—despite the growing success of Sunbeam products—Richard Ashmole Cooper remained a bit distracted. He was, after all, not only running the family business back in England, but also serving as an MP in the British Parliament.

In 1925—having concluded his term in government but still fearing new changes in the pesticide industry—R. A. Cooper decided to merge his business with another British firm, McDougall and Robertson, thus forming Cooper, McDougall & Robertson Ltd. This abruptly ended the “Wm. Cooper & Nephews” era in England. Back in Chicago, however, the name oddly carried on for another several decades, under the slightly tweaked William Cooper & Nephews Incorporated. The company even moved into a new central plant at 1909 North Clifton Avenue in Lincoln Park—the old colonial satellite somehow maintaining a legacy its royal overlords couldn’t.

[As of 2017, the former Cooper & Nephews plant at 1909 N. Clifton Ave. was owned by the controversial and beleaguered General Iron Industries Inc.]

[As of 2017, the former Cooper & Nephews plant at 1909 N. Clifton Ave. was owned by the controversial and beleaguered General Iron Industries Inc.]

In the 1930s, with the Depression forcing the worldwide Cooper business to lighten its load, the Chicago Flexible Shaft Company was gradually sold off and granted its complete American independence under the leadership of another ex-Cooper employee, Horace Caldwell Wright. By the end of World War II, Chicago Flexible Shaft renamed itself Sunbeam Corp, and its home appliance wing became its central focus—eventually turning the business into a billion-dollar juggernaut. The Cooper Co. reaped none of the benefits.

IV. The DDT Dice Roll

Maybe the most memorable of Wm. Cooper & Nephews’ missteps, however, was actually a triumph in its own time.

As mentioned in the intro, the chemical compound known as DDT (Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane if you’re training for an evil spelling bee) became something of a sensation during World War II, temporarily destroying the threat of malaria and typhus in some parts of Europe, and quickly finding its way into numerous household products in America. The Swiss chemist who’d first discovered DDT’s pesticidal power, Paul Hermann Müller, even won the Nobel Prize for his efforts in 1948.

As mentioned in the intro, the chemical compound known as DDT (Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane if you’re training for an evil spelling bee) became something of a sensation during World War II, temporarily destroying the threat of malaria and typhus in some parts of Europe, and quickly finding its way into numerous household products in America. The Swiss chemist who’d first discovered DDT’s pesticidal power, Paul Hermann Müller, even won the Nobel Prize for his efforts in 1948.

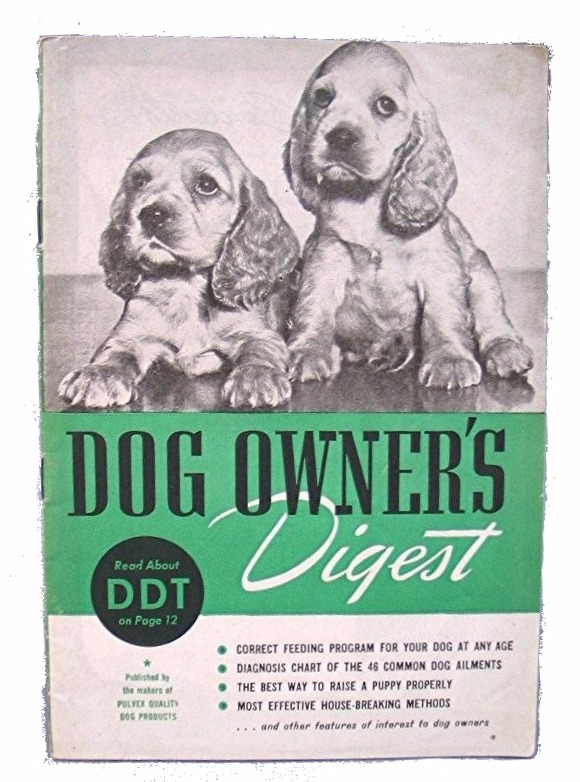

Quite understandably then, the various international subsidiaries of Cooper wore their involvement with DDT as a badge of honor. The parent company had produced much of the DDT-rich AL63 powder used during the war, and in peacetime, they now proudly promoted the introduction of DDT into the war on everyday pests. Even at this stage, some researchers were beginning to raise questions about DDT’s potential long term effects, but to the general public, the three letters carried only a positive context.

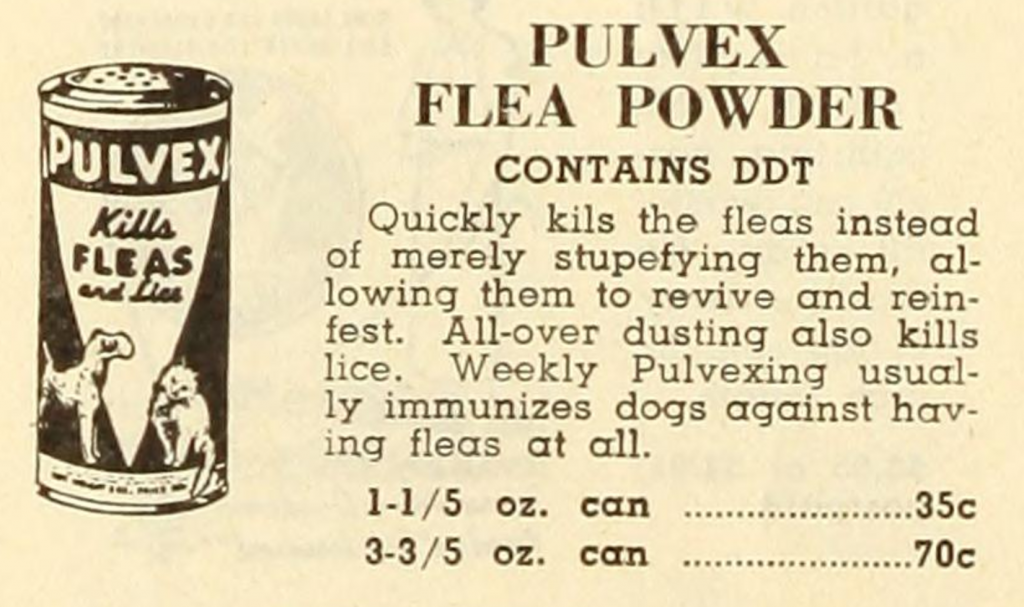

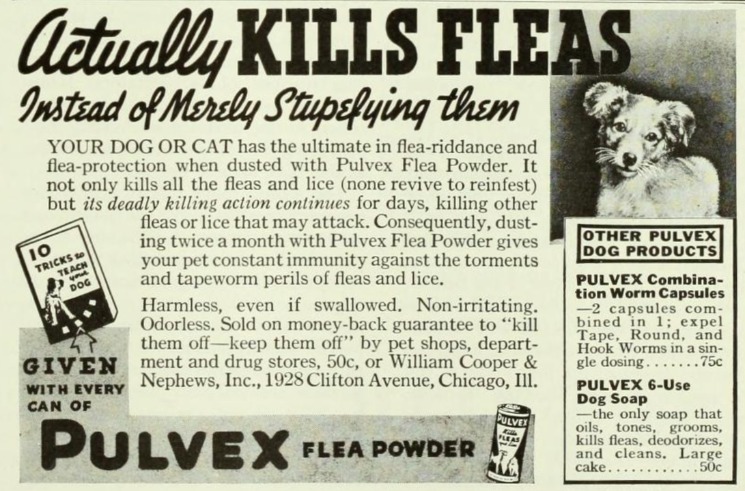

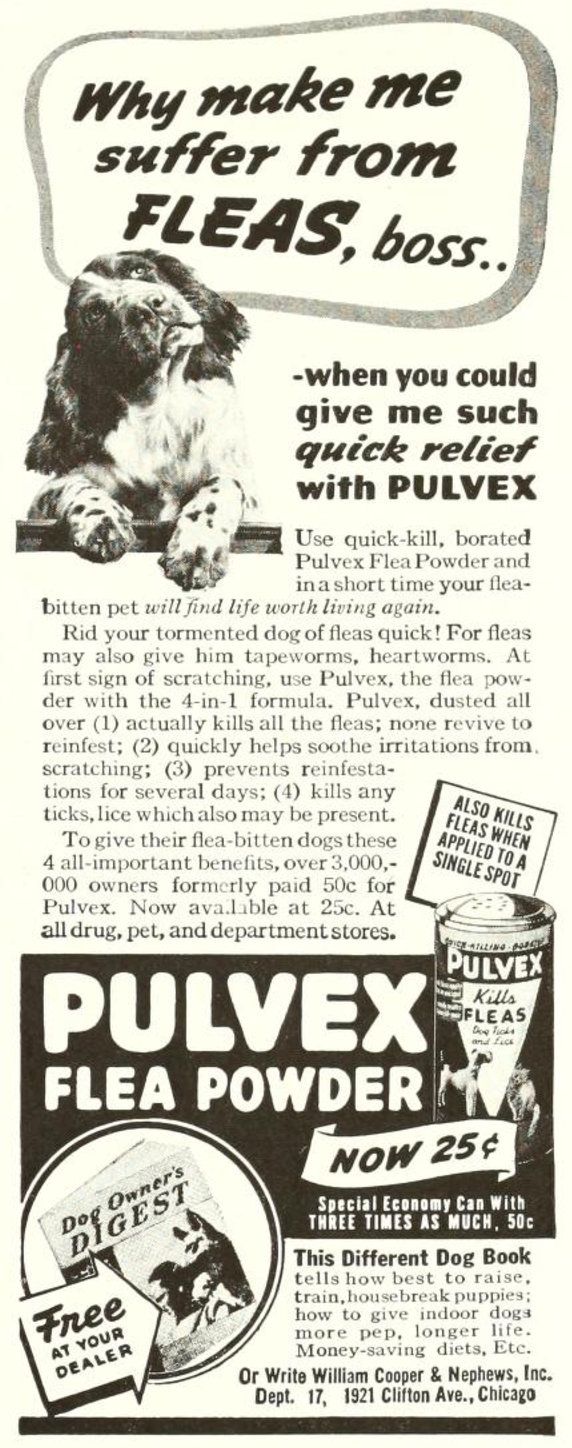

Despite Cooper & Nephews’ elite research department and unmatched experience in the field, the possible health risks of DDT never became a deterrent. In 1946, the compound was added to a number of Cooper’s agricultural and household products, including its well-established Pulvex brand of flea powders. The change was aggressively promoted, from newspaper ads to the front cover of Cooper’s own self-published periodicals, like Dog Owner’s Digest [pictured].

Despite Cooper & Nephews’ elite research department and unmatched experience in the field, the possible health risks of DDT never became a deterrent. In 1946, the compound was added to a number of Cooper’s agricultural and household products, including its well-established Pulvex brand of flea powders. The change was aggressively promoted, from newspaper ads to the front cover of Cooper’s own self-published periodicals, like Dog Owner’s Digest [pictured].

Perhaps as no coincidence, 1946 also found the company under increasing pressure to find new footing, following the end of its wartime contracts and the death of longtime chairman Richard Ashmole Cooper. The rise of new synthetic insecticides was also spelling doom for the 100 year-old Cooper line of animal dip products. And so, they hooked their wagons to the DDT phenomenon likely as much out of desperation as anything else.

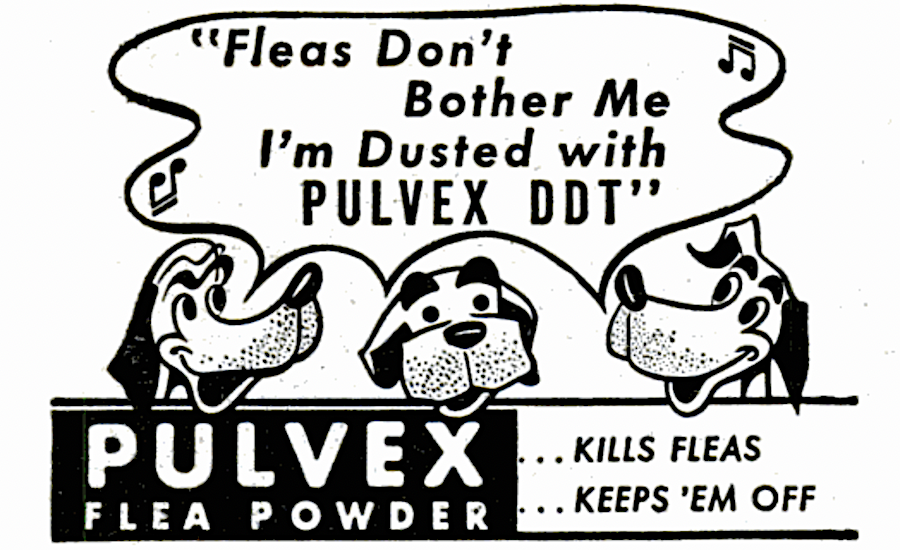

In Chicago, John Smillie—the capable president of Wm. Cooper & Nephews Inc.—supported the DDT push as a sensible marketing strategy. The resulting Pulvex ad campaign, featuring cartoon dogs basking in their DDT baths, have become lasting images of an infamous chapter in environmental history.

[1949 advertisement]

“Fleas don’t bother me,” three cartoon canines sing in a 1949 magazine ad, “I’m dusted with Pulvex DDT.”

Even as late as 1961—when our DDT-free “Kitty & Cat Flea Powder” was produced—Cooper & Nephews was still simultaneously selling its stronger Pulvex powder with DDT included—as seen in this catalog picture from that year.

The U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, in an analysis titled “Controlling Fleas,” also reported quite matter-of-factly on the issue in the 1960s, claiming that “DDT and lindane are effective on dogs but are not recommended for pups or for cats. You can buy these insecticides ready for use as flea powders or sprays. . . . If you use DDT or lindane powder on a dog,” the report further noted, “do not use more than 5 percent of DDT or 1 percent of lindane.”

Everyone seemed aware of the potency of the stuff, but unwilling to follow that thread to its end.

Finally, just a year after our own bottle of Kitty & Cat Flea Powder was sold, author Rachel Carson changed everything with the release of her groundbreaking book Silent Spring, blowing the lid off the DDT threat and revealing its dangerous long term effects on plant, animal, and human life. In short order, the industry was in retreat.

It was another rough blow for William Cooper’s nephews’ descendants. The British parent company Cooper, McDougall & Robertson Ltd. had been purchased by the Wellcome Foundation in 1959, and while some of its various brands would survive into the decades ahead (particularly in places like Australia, where Pulvex is still sold), most ties to the original business were gradually lost. Chicago’s William Cooper & Nephews Inc. operated under the Wellcome banner through the ‘60s and into the ‘70s, as well, but seems to have left its Clifton Ave. plant behind by the 1980s.

Using Your Pulvex Kitty & Cat Flea Powder

Bridging a gap no one knew existed, the marvelous mini 2 oz. can of flea powder in our collection wasn’t merely for cats, but pH balanced for a kitty, too. And maybe even a kitty-cat if you had happened to have one of those. While the bottle doesn’t feature the common Pulvex slogan, “Killing them off and keeping them off,” it does at least include an artful flourish of the word “Kills” on the lid, getting the point across gracefully.

Bridging a gap no one knew existed, the marvelous mini 2 oz. can of flea powder in our collection wasn’t merely for cats, but pH balanced for a kitty, too. And maybe even a kitty-cat if you had happened to have one of those. While the bottle doesn’t feature the common Pulvex slogan, “Killing them off and keeping them off,” it does at least include an artful flourish of the word “Kills” on the lid, getting the point across gracefully.

Since we’ve established that DDT wasn’t safe for meowers, this formula was “specially prepared for cats” and “medicated with dichlorophene to stop scratching and itching caused by fungi and bites by fleas and lice.”

Directions

“To kill fleas and lice, powder should be applied lightly all over and rubbed down to skin [over me or my cat?!]. Dust living quarters to prevent reinfestation. Repeat at weekly intervals if necessary.

CAUTION: Avoid prolonged breathing of dust. Wash thoroughly after use. Avoid contamination of feed and feedstuffs. Keep out of reach of children.

Sources:

“The Famous Dip That Helped Cure the Scourge of Sheep” – Dacorum Heritage Trust

“From Sheep Dip To Shearing Machines” by Ron Wiley, OzWrenches.com

“Cooper, McDougall & Robertson” – Grace’s Guide

“Berkhamsted William Cooper” – Hertfordshire Genealogy

New Scientist – Jan 17, 1963

“Controlling Fleas” – Home & Garden Bulletin 121, U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, 1967

Wellcome: One Hundred Years, 1880-1980, pub. by Wellcome Foundation

I have some pulvex all purpose vetinary ointment ..I want to put on dogs paws..worried about licking

I have a bottle of the Pulvex and I have tried to research it but can not find information on the bottle I have it says Corp. 1946 but their is no animals on it, it has the logo but then states NOW CONTAINS world Famous DDT. I was just curious on the product and when it was actually made. I hope you can help, thanks in advance!