Museum Artifact: Turtle Wax “Hard Shell Finish” Auto Polish and Turtle Wax Furniture Polish Set, 1950s

Made By: Plastone Company / Turtle Wax, Inc., 4100 W. Grand Ave. [West Humboldt Park] and 1800 N. Clybourn Ave. [Lincoln Park]

On June 4, 1956—just five years after the first bottles of Turtle Wax “Miracle Auto Polish” hit the consumer market—Chicago workmen began installing a new, ludicrously enormous advertisement for the product, situated atop the roof of the Wendell State Bank “Flatiron” Building at the intersection of Madison, Ogden, and Ashland Avenue.

Described by one newspaper as “an amazing sign that has no counterpart in the whole United States,” the $200,000 electrified structure—built by the Victor Sign and Display Co.—depicted “a giant turtle 34 feet high . . . made from 3,200 square feet of fiberglass and 15,000 pounds of structural and fabricated steel, rising the equivalent of 7-1/2 stories above the roof” of the 10-story office building.

Described by one newspaper as “an amazing sign that has no counterpart in the whole United States,” the $200,000 electrified structure—built by the Victor Sign and Display Co.—depicted “a giant turtle 34 feet high . . . made from 3,200 square feet of fiberglass and 15,000 pounds of structural and fabricated steel, rising the equivalent of 7-1/2 stories above the roof” of the 10-story office building.

Adorned with a top hat and proudly holding up a man-sized bottle of car wax in his outstretched left hand (upper foot?), this “super turtle” also rotated 360 degrees on a steel column; told the time; and magically changed color to communicate impending variances in the local weather. “Red will forecast warmer weather; blue, cold weather; white, rain or snow; and green for no change. There’s never been anything like it before!”

At the official dedication of the reptilian monstrosity on June 15, “a thrilling motorcade of famous celebrities [Peter Lawford, Barbara Britton, and the singing group The Crew-Cuts among them!] wound through the Loop and out to ‘Turtle Square,’ stopping traffic and attracting thousands of spectators to whom were thrown 50,000 little turtles” [hopefully not real ones].

The beloved singer and actor Jimmy Durante was supposed to flip the switch to illuminate the sign that day, but after the event promoters found him passed out in his room at the Drake Hotel with a collection of chorus girls, they thought better of it.

[“Turtle Square” at the intersection of Ashland, Madison, and Ogden Ave. The giant Turtle Wax sign is believed to have been lost when the Flatiron building itself was leveled in the late 1960s]

“When, finally, the lights of the astonishing ‘Turtle in the Sky’ were turned on,” according to the The Herald newspaper of Crystal Lake, Illinois, “thousands of balloons were released in a glorious, colorful, bewildering cloud from the windows of the building on which it stands. . . . The sensational turtle is a new Chicago landmark, visible for miles.”

This, ladies and gentlemen, was not the sort of gaudy spectacle one would generally expect from a “humble family business” still in its foundational years. But it was, in many ways, emblematic of what set Turtle Wax inventor and company president Ben Hirsch apart from most of his contemporaries.

Sure, the car polish itself—which Hirsch first cooked up in the early 1940s—did a nice job helping grease monkeys see their own reflections in the fins of their T-Birds. But competing products like those sold by crosstown rivals Simoniz could already produce a protective sheen quite effectively.

Sure, the car polish itself—which Hirsch first cooked up in the early 1940s—did a nice job helping grease monkeys see their own reflections in the fins of their T-Birds. But competing products like those sold by crosstown rivals Simoniz could already produce a protective sheen quite effectively.

For Hirsch, it was a promotional savvy and love of showmanship that really provided the separator in his industry, helping turn Turtle Wax, Inc. from a $500 investment into one of the largest and best known auto care brands in the world.

As the 34-foot electric rotating terrapin in the top hat would suggest, humbleness didn’t have nothin’ to do with it.

History of Turtle Wax, Part I. “Suited to Salesmanship”

“My father was an entrepreneur, a dreamer. . . . He was my role model because he was so supportive and worked so hard, with honesty and integrity, and brought me along.” —Sondra Hirsch Healy, Turtle Wax executive and daughter of founder Ben Hirsch

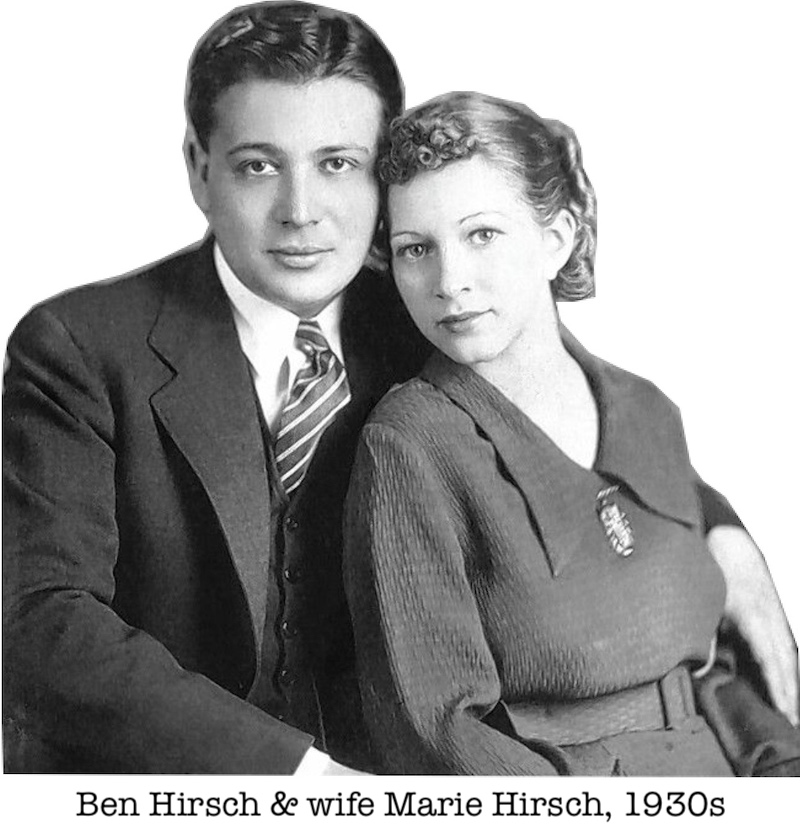

Benjamin Franklin Hirsch was born in Chicago in 1910; a first generation Jewish American and eldest son to an Austrian father and Russian mother. His dad Morris Hirsch (aka Max Hirsch) was a tailor and furrier by trade, and sold minks out of a small storefront in Lake View at 3165 N. Clark Street, right across from the Hirsch family home at 831 W. Fletcher Street.

Benjamin Franklin Hirsch was born in Chicago in 1910; a first generation Jewish American and eldest son to an Austrian father and Russian mother. His dad Morris Hirsch (aka Max Hirsch) was a tailor and furrier by trade, and sold minks out of a small storefront in Lake View at 3165 N. Clark Street, right across from the Hirsch family home at 831 W. Fletcher Street.

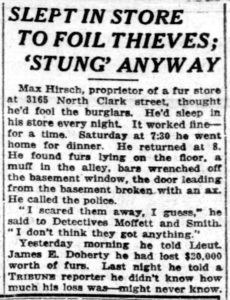

In 1919, when Ben was 9, his father took to sleeping in the store every night as a way to deter burglars—reflecting perhaps on the nature of the neighborhood and/or the anxiety of the shopkeeper.

One October evening, after coming home for a brief dinner with his wife and kids, Max Hirsch returned to the store to find “furs lying on the floor, a muff in the alley, bars wrenched off the basement window, and the door leading from the basement broken with an ax,” according to the Tribune. The furrier’s vigilant commitment to security had perhaps been warranted, after all.

“I scared them away, I guess— I don’t think they got anything,” Max supposedly told the police that night, but the Tribune claimed that his story soon changed, and that Hirsch later notified the cops that $20,000 worth of furs had indeed gone missing. When a reporter from the paper followed up with him, Max doubled back again, saying “he didn’t know how much his loss was—might never know.”

We’ll never know either—although we can certainly consider the antisemitic biases of the era when assessing how the police and news media handled the incident.

We’ll never know either—although we can certainly consider the antisemitic biases of the era when assessing how the police and news media handled the incident.

Anyway, like many sons of immigrants, Benjamin Hirsch both emulated his hard-working father and hoped to achieve something greater for himself. We don’t even need to speculate on the kid’s work ethic, as we have a pretty unique insight on the subject. At the age of 23, Ben was one of dozens of random citizens featured in a 1933 research project called “Civilian Morale,” conducted by the Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues.

“Benjamin Hirsch is 23 years old, of Russian Jewish lineage,” the case study began, featured in a chapter on “Morale During Unemployment.”

“Though he is just finishing his senior year in night school at a municipal college, he has had four and a half years of full-time work experience. His father is a tailor working part time, and it seems both father and son have worked hard at the job of putting Ben through college.”

Ben Hirsch’s daughter later claimed that her dad wanted to be a chemist, but had to drop out of college for financial reasons. According to this study, though, Ben did at least finish community college, as his visit to the Adjustment Service in 1933 was related to “his impending graduation and the need to decide what to do next.”

[In 1933, a 23 year-old Ben Hirsch took part in a study on civilian “morale during unemployment,” as he was one of many young people seeking guidance during a time when unemployment lines, like the one above operated by a local good samaritan named Al Capone, were the norm.]

In the early years of the Depression, Ben had worked for no more than $15 per week—first for a clothing manufacturer, then an auto repair shop—all while taking his night classes. “His intelligence is very high (93d percentile),” the study noted, “and his vocabulary and clerical ability scores are good. . . . He exhibits a high degree of self-sufficiency, but at the same time he enjoys social relationships and makes friends easily. The counselor classifies him as an extrovert, and considers him suited to salesmanship. . . . Although Ben has had to work at an uninspiring job for little money in order to pay his way through college, he considers himself luckier than most people.”

Many of Ben Hirsch’s subsequent adventures—as told through Turtle Wax company lore—seem to routinely tip-toe into tall-tale territory. But the consistent threads of most of those stories do tie back to the same personality traits his counselor saw way back in 1933: self-sufficiency, charm, and persuasiveness.

Many of Ben Hirsch’s subsequent adventures—as told through Turtle Wax company lore—seem to routinely tip-toe into tall-tale territory. But the consistent threads of most of those stories do tie back to the same personality traits his counselor saw way back in 1933: self-sufficiency, charm, and persuasiveness.

When the money crunch of the Great Depression killed his dream of becoming a chemist, for example, Hirsch found ways to earn extra money as a grocer, supposedly inventing new treats like the chocolate-covered banana to entice passersby. Nights and weekends, he traded in his apron for a top hat and wand, working as an amateur magician. And according to at least a few far-reaching sources, he even popped up on the local wrestling circuit as a manager and promoter. This guy was drawn to any just about any bright spotlight like a moth.

Even when Hirsch finally acquired more “legitimate” work as a salesman for the Hartz Mountain Products company in the late ‘30s, he maintained his love of the performance . . . making a connection with a potential customer. Working the sales circuit in St. Louis and as far west as Oklahoma, Hirsch sang the praises of Hartz Mountain’s famous bird seed and likely promoted one of its newer canned pet products, as well: Turtle Food. It might not have been a dream job, but who knows, it could have helped inspire some of Ben’s pivotal marketing concepts a few years later.

Even when Hirsch finally acquired more “legitimate” work as a salesman for the Hartz Mountain Products company in the late ‘30s, he maintained his love of the performance . . . making a connection with a potential customer. Working the sales circuit in St. Louis and as far west as Oklahoma, Hirsch sang the praises of Hartz Mountain’s famous bird seed and likely promoted one of its newer canned pet products, as well: Turtle Food. It might not have been a dream job, but who knows, it could have helped inspire some of Ben’s pivotal marketing concepts a few years later.

By 1940, while still in St. Louis working for Hartz, Hirsch and his wife Marie had their first child, a daughter named Sondra. The couple was now increasingly motivated to build something of their own—to turn that old love of magic potions into something viable for the modern age, and for the long term well-being of their family.

“I don’t care where an idea comes from,” Ben would later tell his daughter. “Just let’s see what we can do with it.”

II. The Plastone Company

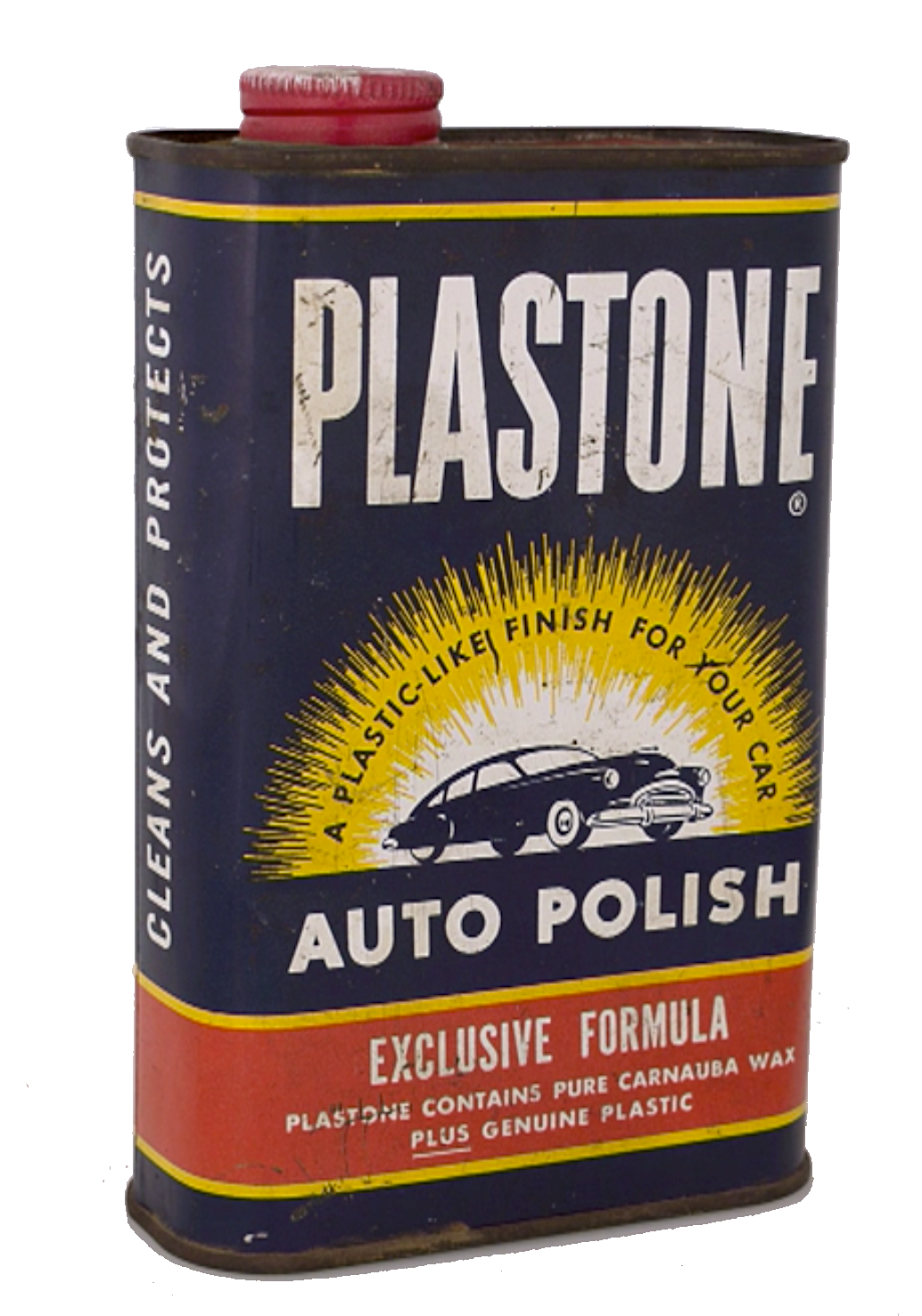

“No other auto polish—ONLY PLASTONE contains 100% Carnauba Wax, Genuine Plastic, plus SILICONES! PLASTONE is not just a car cleaner, not just a car finish, but an exclusive scientific formula that cleans, polishes and protects your car all in one quick simple operation.” —advertisement for Plastone Auto Finish, 1950

In most tellings of the Turtle Wax legend, Benjamin Hirsch is said to have had his “Eureka!” moment in either 1940 or 1941. This is when he supposedly stumbled upon a new liquid formula car wax—a creation he perfected by using the family bath tub as a brew kettle, and which wife and business partner Marie Hirsch then collected into glass bottles for small-time distribution. This original product was NOT called Turtle Wax, mind you, but “PLASTONE,” and it didn’t exactly cause an overnight sensation.

In most tellings of the Turtle Wax legend, Benjamin Hirsch is said to have had his “Eureka!” moment in either 1940 or 1941. This is when he supposedly stumbled upon a new liquid formula car wax—a creation he perfected by using the family bath tub as a brew kettle, and which wife and business partner Marie Hirsch then collected into glass bottles for small-time distribution. This original product was NOT called Turtle Wax, mind you, but “PLASTONE,” and it didn’t exactly cause an overnight sensation.

While Ben and Marie organized the Plastone Company during the war to sell to local garages and gas stations, the business didn’t get a proper acknowledgement in the Certified List of Domestic and Foreign Corporations of Illinois until 1947 (with an HQ at 2014 W. Wabansia Avenue). Newspaper ads for Plastone floor wax and auto polish don’t start popping up until ’46 and ’47 either. This means that—if Hirsch truly did perfect his formula before Pearl Harbor—he likely would have spent the next five long years patiently pondering its commercial peacetime potential. This was no easy road to riches.

“There were several times my dad nearly went bankrupt,” Sondra Hirsch Healy told the Tribune in 1993. “There were times that he borrowed money from his employees and repaid them in stock—just to keep the business from going under.”

Ben Hirsch ran a series of small storefronts in the ‘40s to keep his family fed, but spent much of his own time hopping on and off of streetcars, trying to sell Plastone to disinterested gas station attendants. In another bit of lore, he also apparently enjoyed surveying the parked cars outside Wrigley Field during a game, often applying Plastone to one half of a vehicle as a sort of guerilla-style “before and after” advertisement, communicated by a business card.

[Ben Hirsch posing with a bottle of Plastone, late 1940s]

“We moved around a lot in the Chicago area,” Sondra Healy recalled. “I can remember we, my brother and I, slept on the countertop of the storefront on Clark Street.”

Ben Hirsch had become his father’s son—sleeping in the store out of both dedication and desperation.

Business did, of course, start to pick up.

We don’t really know how closely those early bath tub batches of Plastone resembled the mass-produced bottles of the late ‘40s and early ‘50s, but it seems certain that Hirsch started with ample amounts of carnauba wax (aka Brazil wax and palm wax), which was already used in many cleaning polishes of the day, including O-Cedar floor wax. He then dipped into his amateur chemist’s kit to integrate mysterious portions of “plastic” and “silicone” to create something a bit more tough and weather resistant.

We don’t really know how closely those early bath tub batches of Plastone resembled the mass-produced bottles of the late ‘40s and early ‘50s, but it seems certain that Hirsch started with ample amounts of carnauba wax (aka Brazil wax and palm wax), which was already used in many cleaning polishes of the day, including O-Cedar floor wax. He then dipped into his amateur chemist’s kit to integrate mysterious portions of “plastic” and “silicone” to create something a bit more tough and weather resistant.

The romantic version of the Plastone / Turtle Wax origin story always focuses on the mom-and-pop aspect of the business—Ben and Marie bottling their own wax by hand and personally convincing local gearheads, one by one, to give it a try. By 1950, though, Plastone’s own advertising was trying to communicate something altogether more clinical and much larger in scope.

“From the scientific laboratories that discovered the amazing new auto polish PLASTONE,” one ad read, “comes the story of its dramatic secrecy—the story of painstaking laboratory test after laboratory test. Tests under all conditions! Brutal tests in the heat—the cold—the sun—the rain! Tests by large automobile fleet owners—by scores of used car dealers all over the world—tests to prevent rust, corrosion—tests of all sorts—until finally after years of exhaustive scientific research, the manufacturers of PLASTONE felt they had at last discovered the formula for ONE amazing auto polish that the public had so long been in need of!”

Hey, why end a rant on a preposition when you were on such a self-congratulating roll?

[1950 newspaper ad for “Sensational new PLASTONE”]

Anyway, with bottle production ramping up at the Wabansia plant and a Plastone Company home office secured at 318 W. Randolph Street, the Hirsches seemed to be set for their big breakout as the 1950s began.

Ben Hirsch wasn’t entirely satisfied with the trajectory of the Plastone brand, however. For one thing, there were several other random plastics businesses using the same made-up word to sell unrelated products. For another, marketing Plastone was proving a bit of a clunky undertaking, as people sometimes had trouble connecting the dots between the brand and its intended use. What was Plastone again? A cleaner? A polish? A doo-wop group?

And so there came the fateful day that Ben Hirsch—while on a sales trip outside Beloit, Wisconsin—drove past a sign for “Turtle Creek.” Instantly, a new vision appeared to him, as the course of his company was permanently recalibrated.

III. Hero in a Half Shell

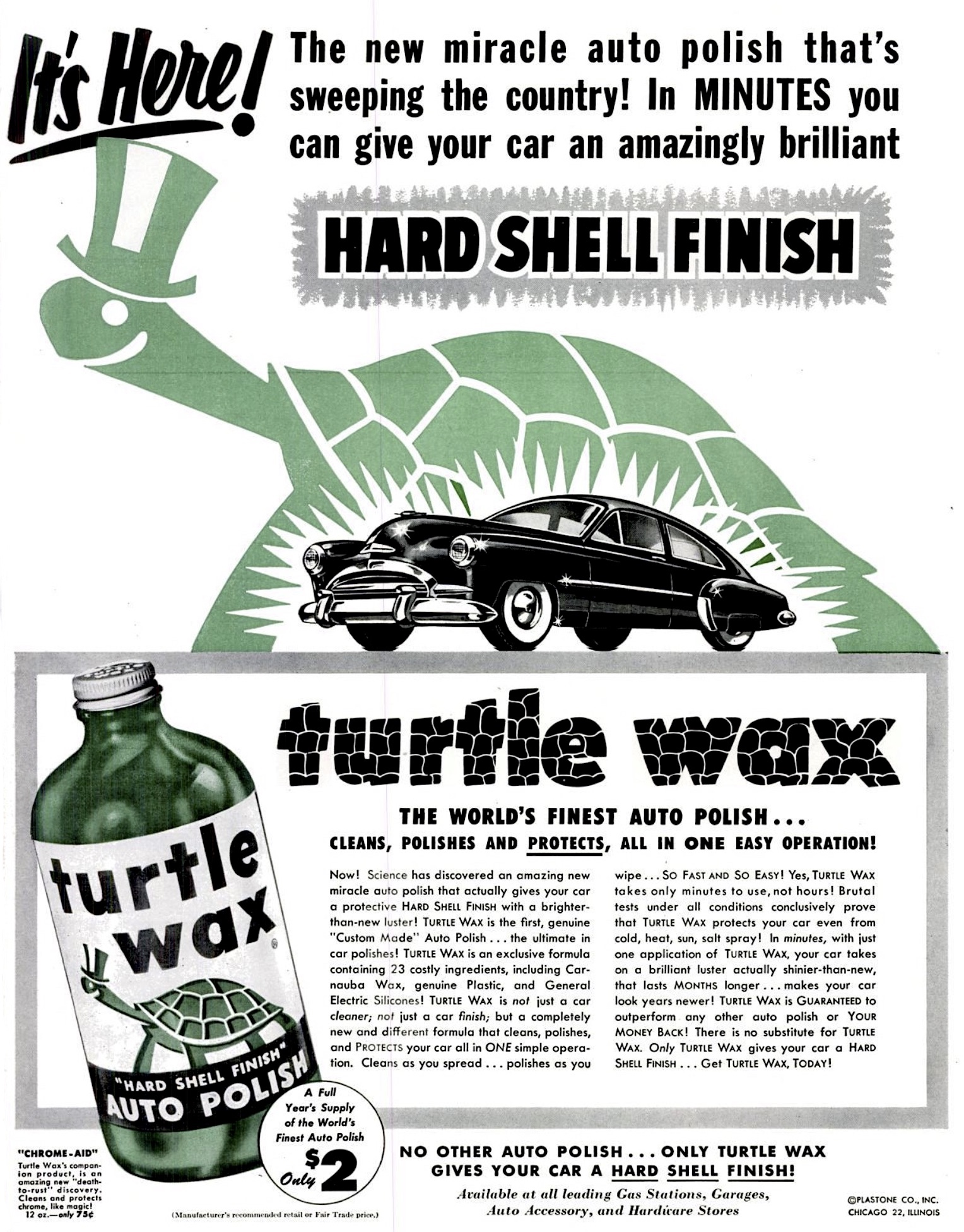

“Now! Science has discovered an amazing new miracle auto polish that actually gives your car a protective Hard Shell Finish with a brighter-than-new luster! Turtle Wax is not just a car cleaner, not just a car finish, but a completely new and different formula that cleans, polishes, and Protects your car all in ONE simple operation.” —Turtle Wax advertisement, 1953

Basically, Turtle Wax was Plastone. The differences between the two original Auto Polishes are negligible, if nonexistent. The difference in sales, of course, was substantial.

Basically, Turtle Wax was Plastone. The differences between the two original Auto Polishes are negligible, if nonexistent. The difference in sales, of course, was substantial.

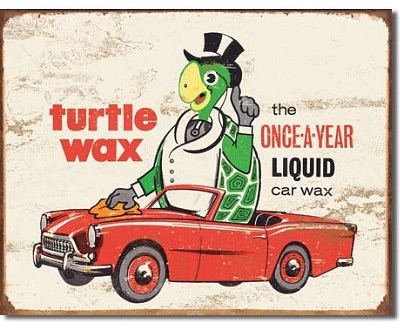

With the branding change, Ben Hirsch had simply likened the texture and protective quality of his Plastone polish to that of a turtle’s shell . . . or perhaps a tortoise, since the mascot seems to be land-dwelling. Maybe a box turtle? In any case, he didn’t phase out the Plastone brand completely, but instead introduced “Turtle Wax” as a new product under the Plastone Company banner. Company histories often suggest this whole concept was born in the late ‘40s, but it doesn’t appear that a full marketing plan was up and running until 1951, when the aggressive Turtle Wax ad campaign began its shelling of America’s newspapers.

Early on, Hirsch had recognized that merely communicating the “idea” of a “hard shell finish” for your car wouldn’t be enough. Turtle Wax would need an instantly recognizable image; a logo, label or character—as was the 1950s trend—to catch the public’s attention in mid-stride. Advertising in the new medium of television, as well, would be essential to the effort.

[1953 Turtle Wax advertisement that appeared in Life magazine]

Towards this end, Hirsch now had a small crew of capable minds to help him tell the world about Turtle Wax, including sales manager Walt Power, art director Glen Baker, former Simoniz VP and advertising manager Harry L. Nehrbass, and the ad men from the W. B. Doner & Co. agency. From somewhere within these pooled resources came the famous Turtle Wax trademark—a green, smiling terrapin wearing a top hat . . . a likely nod to Ben Hirsch’s retired magician attire.

This is the logo featured on our the label of our museum artifact, a one-pint green Duraglass bottle dating from the early 1950s, when the Plastone Company manufacturer name was still in use.

“Cleans as you spread, Polishes as you wipe,” the bottle says, followed by directions for using the product, “So fast and so easy!”

“Cleans as you spread, Polishes as you wipe,” the bottle says, followed by directions for using the product, “So fast and so easy!”

- Apply TURTLE WAX to surface with clean, soft cloth.

- Allow to dry, then merely wipe off!

- Avoid application on hot surface; for best results wash car first.

The turtle logo’s genius speaks for itself, but it’s the way the Plastone marketing department brought it to life that really made all the difference.

The Doner ad agency, for their part, produced a memorable TV commercial featuring a cartoonized version of the mascot, Tommy the Turtle, voiced by a Jimmy Durante sound-a-like. Saving the day in Superman style (in an ad already overstuffed with pop culture references), Tommy defeats “Dangerous Dirt,” “Drippy Rain” and “Torchy Sun” before giving way to one of television’s early ear-worm jingles: Turtle Wax Gives a Hard Shell Finish! Turtle Wax!

[Turtle Wax TV commercial, 1950s]

Colorful newspaper and magazine ads were joined by neon signs and billboards, and of course, by 1956, the coup de grace: the 34-foot turtle towering over the Plastone offices at Ashland, Madison, and Ogden.

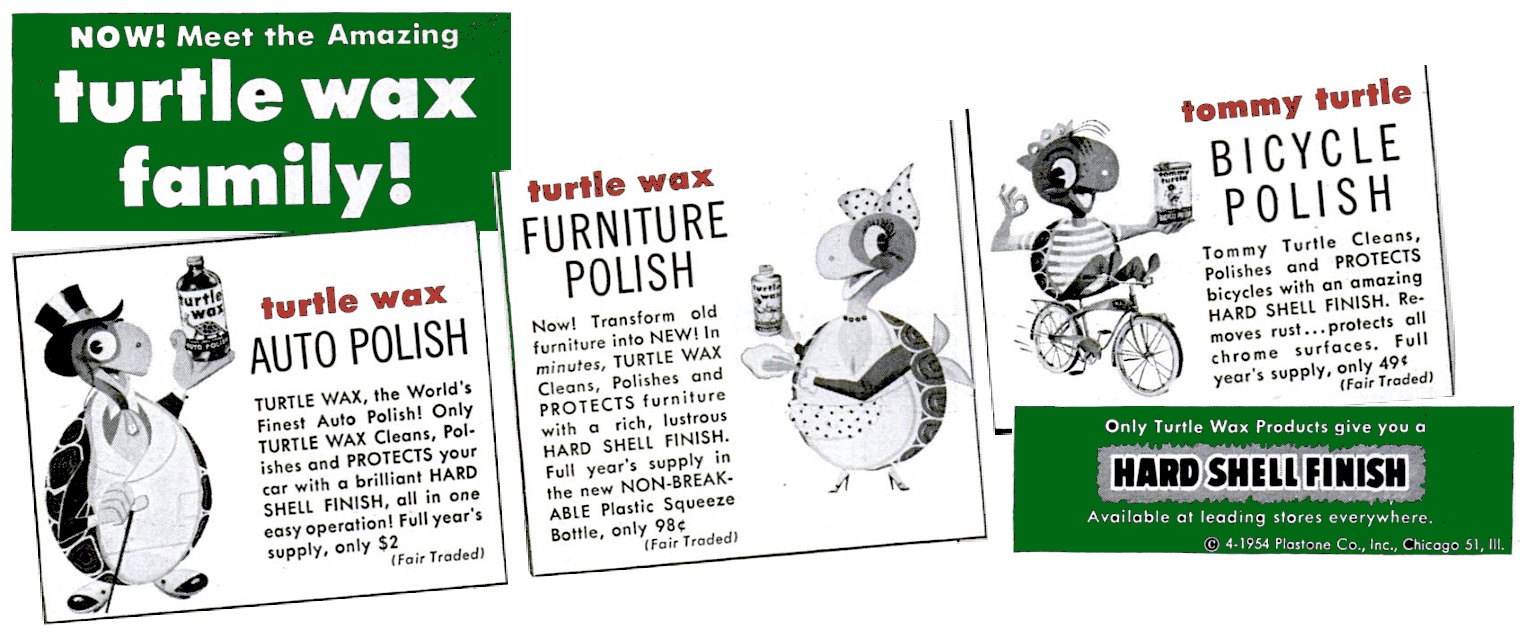

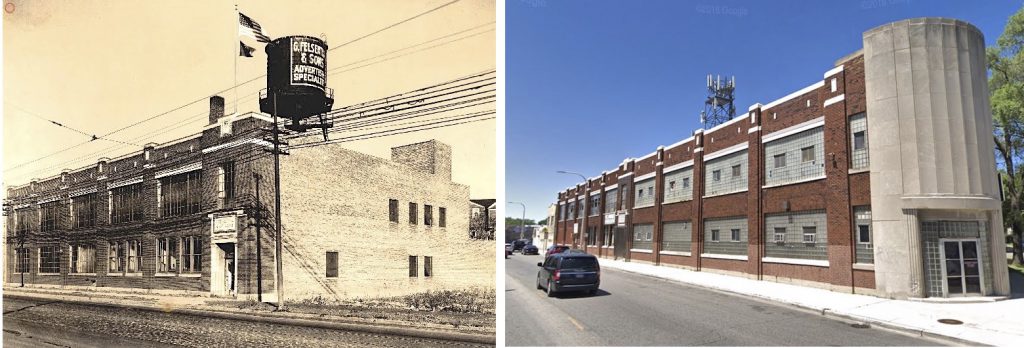

The primary headquarters of the company in the ‘50s was considerably further west, at 4100 W. Grand Avenue; the recently abandoned factory of G. Felsenthal & Co. Here, Hirsch and his creative team hammered out new ways to illustrate the greatness of a product that only cost $2 for a full year’s supply—not to mention developing ideas for new products that might ramp up those sales figures a bit. Soon, there was a whole “Turtle Wax Family” of products, including Turtle Wax Furniture Polish and “Tommy Turtle” Bicycle Polish.

[Above: 1954 ad for the “Turtle Wax Family” of products. Below: The Turtle Wax plant at 4100 W. Grand Ave, seen just before the company took it over from G. Felsenthal & Co. in 1953, and its current look in 2019]

“The yeast in our marketing mix is excellence in packaging and promotional materials,” Hirsch later said. “Alongside product quality and distribution, effectiveness in our success story is art.”

In one issue of the beloved trade magazine Soap, Cosmetics, Chemical Specialties, art director Glen Baker shared his personal philosophy behind the Turtle Wax packaging strategy.

“If you’re going to do the job in packaging,” Baker said, “you’ve got to be prepared to pay the price in time, effort and money.

“. . . First, a package should instantly identify itself to the potential customer. Second, it must offer an unmistakable and distinct benefit. Third, it should provide harmony in physical shape and proportions and in design elements. And fourth, it should be colorful and appealing enough to sell itself on the dealer’s shelves. . . . And one more important thing—don’t change a package just for the sake of change. When you do change, be careful to maintain an identity with the previous package.”

“. . . First, a package should instantly identify itself to the potential customer. Second, it must offer an unmistakable and distinct benefit. Third, it should provide harmony in physical shape and proportions and in design elements. And fourth, it should be colorful and appealing enough to sell itself on the dealer’s shelves. . . . And one more important thing—don’t change a package just for the sake of change. When you do change, be careful to maintain an identity with the previous package.”

By the mid 1960s, Baker and the ever-familiar Turtle Wax brand had won “close to 30 major awards for superiority in package design, display pieces, brochures and catalog sheets,” according to the Soap publication—although the magazine may have collected that random statistic direct from the proverbial turtle’s mouth.

The ‘60s also saw Turtle Wax Inc. (now free of its former Plastone identity) establish its new headquarters at 1800 N. Clybourn Avenue in Lincoln Park; a sprawling factory near Goose Island that was later converted into a major shopping complex in the late 1980s. The company’s first international plant, in England, opened in 1966.

[Left: Part of the former Turtle Wax plant at 1800 N. Clybourn Ave., now part of the shopping complex of the same name (1800 Clybourn). Right: Worker at the Clybourn plant loading Turtle Wax’s second generation glass bottles with plastic twist tops, 1960s. Below: A 1962 advertisement for Turtle Wax Car Wax and Spray Car Wax]

As driven as ever, Ben Hirsch remained intent on expanding his business both within and beyond the automotive market. Soon, there were Turtle Wax branded engine cleaners, vinyl top cleaners, rubbing compounds, aerosol sprays, and “instant saddle soap” to go along with the established floor waxes and furniture polishes. There was even a spray-on, pure wax shoe polish called “Penny Shoe Shine.” Some attempts proved better than others. Penny Shoe Shine, specifically, was a massive failure, cracking the leather on more shoes than it shined. But the R&D team was always encouraged to keep the ideas coming.

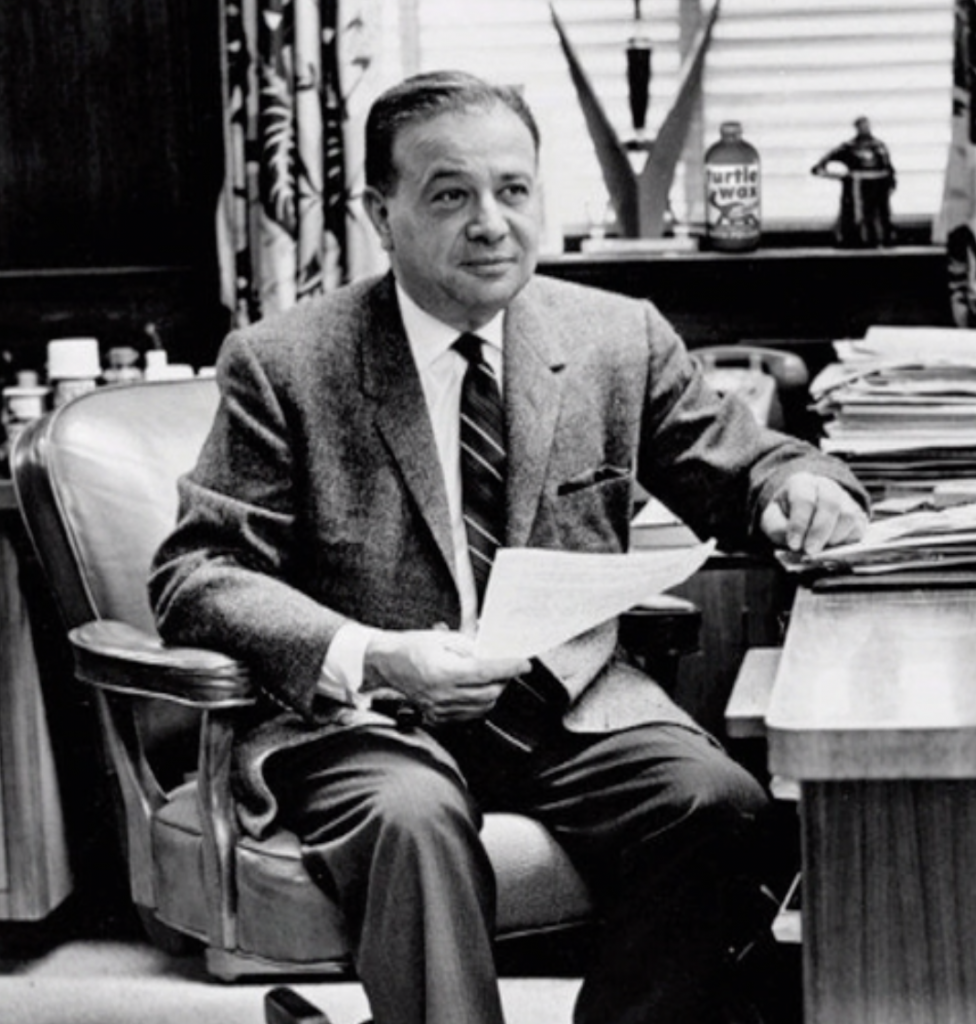

It was only when Benjamin Hirsch died suddenly of heart failure in 1966, at age 55, that surviving board members—including his widow Marie and new president Carl F. Schmid—were forced to reassess the adventurous direction of the company going forward.

[Benjamin Hirsch, 1910-1966]

IV. Healing and Healys

Thrown into this tumultuous transitional period was 24 year-old Sondra Hirsch, a recent graduate of Chicago’s Goodman School of Drama. Up to this point, she had been more inspired by her father’s talents in the performing arts than his victories in the corporate world. But after losing him, the desire to help her mother and the family business altered Sondra’s career track forever.

“I felt I had to hold the company together,” she told the Tribune in 1993, referring to her decision to join Turtle Wax Inc. as its vice president of public relations in 1966. “I came into the business with the idea that I had to preserve my father’s vision.”

“I felt I had to hold the company together,” she told the Tribune in 1993, referring to her decision to join Turtle Wax Inc. as its vice president of public relations in 1966. “I came into the business with the idea that I had to preserve my father’s vision.”

Sondra had a younger brother, Ben Jr., but he was only 13 when their father died. Just five years later, in 1971, their mother Marie passed away, as well, truly putting enormous pressure on the second generation.

To help right the ship, Sondra wound up recruiting her newly wedded husband, an experienced chemist and R&D man named Denis J. Healy (who’d worked for Colgate-Palmolive and Mennen), to join the executive team at Turtle Wax.

“Her dad started Turtle Wax,” Denis Healy recounted in a 2007 chat at Chicago’s Abraham Lincoln Library, “but he had died three or four years before that, and the place was in disarray. There was a guy working there, the executive VP, who said—protecting the family—that I should come aboard. I said, ‘No way!’ Then, when Sondra got pregnant, that guy said, ‘Eighteen years from now, what will you say when that kid asks, Didn’t grandpa found a company?’ Being a Jewish guy, they always believed in family, and I said, ‘You got me.’ So I gave up my job and went to Turtle Wax.”

[Above: The former Turtle Wax facility in Bedfork Park, in use from 1973 to 2005. Below: Company president Denis Healy with a new line of Turtle Wax products in 1985]

Shortly after Healy joined the fold in the early 1970s, Turtle Wax left behind the plant at 1800 N. Clybourn and escaped to the South Side, specifically 5655 W. 73rd Street in Bedford Park—although corporate offices were retained in the Wrigley Building downtown. The new plant, right near Midway Airport, would remain Turtle Wax HQ for a little over 40 years.

Sondra and Denis Healy would continue to lead the company into the 21st century, often navigating a cycle each decade of trying to diversify the Turtle Wax line of products, only to pull back again back to the safety of the automotive market. In the 1980s, Turtle Wax jumped back into the shoe polish game, and made air fresheners that had promotional tie-ins to ‘80s staples like Strawberry Shortcake and the Care Bears. In the ‘90s, greater focus went into producing car cleaning products for the industrial market, and a number of exclusive Turtle Wax Car Wash facilities were even opened around the Chicagoland area (there were as many as 15 locations at one point, but only two remained open as of 2019).

Even after the recession of the early ‘90s, the company retained a workforce of 500 at the Bedford Park complex, with another 100 still employed at the international headquarters near Manchester, England. Annual sales exceeded $100 million quite consistently—not bad for a business that largely relied on products people might use once a year.

Even after the recession of the early ‘90s, the company retained a workforce of 500 at the Bedford Park complex, with another 100 still employed at the international headquarters near Manchester, England. Annual sales exceeded $100 million quite consistently—not bad for a business that largely relied on products people might use once a year.

The continuing influence of the Healys was both reassuring and invigorating to their employees. “The Healys are very open and treat their workers well,” one Bedford Park employee told the Tribune in 1993. “There’s always something new going on,” said another. “And the bottom line is we’re making money.”

Sondra Healy apparently took particular pride in the fact that the Turtle Wax workers had rejected offers to unionize during her tenure, suggesting they felt their interests were already being addressed by ownership. “You have to have as much of an open dialogue as you can,” Sondra once said. “Let them have their due; if you’re having a meeting, this is their meeting.” By the ’90s, though, the workers at the Bedford Park plant had apparently had a change of heart. They were now represented by the Service Employees International Union Local 106.

For all the benefits of steady, one-family ownership over the decades, that stability didn’t always filter down to other levels of the executive board at Turtle Wax. With Sondra and Denis Healy well past retirement age, the business has gone through a boatload of different presidents and CEOS in the 2000s, including Denis Healy, Jr. representing the third generation of the family business.

[From left: Denis Healy Jr, Sondra Healy, and Denis Healy Sr., 2008]

By 2005, the Bedford Park plant was closed as Turtle Wax looked to focus more on building its brands (including its new “Ice” clear polish) while outsourcing its manufacturing to other (cheaper, overseas) locales. The company maintained offices in Willowbrook, Illinois, for a decade or so, then moved to Addison, IL, in 2016. All Chicago-based manufacturing has ceased. The turtle in the top hat, however, marches on, still among the top selling auto care products in the world.

SOURCES

“Strong Family Histories Help Turtle Wax Shine” – Chicago Tribune, April 11, 1993

“Slept in Store to Foil Thieves; ‘Stung’ Anyway” – Chicago Tribune, Oct 7, 1919

“Oral History – Denis Healy” – Talk at Abraham Lincoln Library, Chicago, 2007

“Turtle to Polish Marketing, Let Others Make Products” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 2, 2005

“An Amazing Sign . . . ” – Marengo Republican-News (Marengo, IL), July 5, 1956

“Start Raising Sign Depicting 34 Foot Turtle” – Chicago Tribune, June 4, 1956

“Rappaport” – The Herald (Crystal Lake, IL), June 28, 1956

Harry L. Nehrbass obit – Chicago Tribune, Dec 28, 1956

“Automotive” – Star Tribune (Minneapolis), Dec 4, 1955

“Jimmy Durante: Nose to Nose with Turtle Wax” – A Passion for Winning: Fifty Years of Promoting Legendary People and Products, by Aaron D. Cushman

“Rites Slated Tomorrow for B. F. Hirsch, 55” – Chicago Tribune, Jan 26, 1966

“Turtle Wax Chief Sees Luster in New Markets” – Chicago Tribune, Jan 29, 1985

“Sondra Healy” – Women in Business: The Changing Face of Leadership, 2007

Turtle Wax Packaging – Soap, Cosmetics, Chemical Specialties, 1971

Civilian Morale, edited by Goodwin Watson, Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues, 1942

“Auto Buffs Asked to Let Cat Out of Bag” – Calgary Herald (Canada), May 27, 1988

I saw a spray can of 1960s/ 1970s winter turtle wax heavy duty. I’d like to know more about this vintage product. I saw it on the Pan the Organizer show when he filmed his show from the headquarters. I’m guessing it was a very hard wax you applied just before winter.

What happened to the statue when the building in Chicago was demolished?

Their vinyl top wax is an excellent dressing for interior vinyl such as the dashboard. Seals and protects for years. I wish it was still available.

I have a glass wax bottle with some wax still end it. It’s old is it valluble

Why did yall quit making Turtle Wax ice total interior care 23 oz.

This is a museum about Chicago industrial history. This isn’t Turtle Wax’s corporate site, nor are we affiliated with them.

I have a rare 1954 tin of Tommy Turtle Bicycle Wax in really good condition and about 85% full. I found it here in rural Utah at a home I have cleaning out. I haven’t been able to find a photo of the can I have anywhere online.