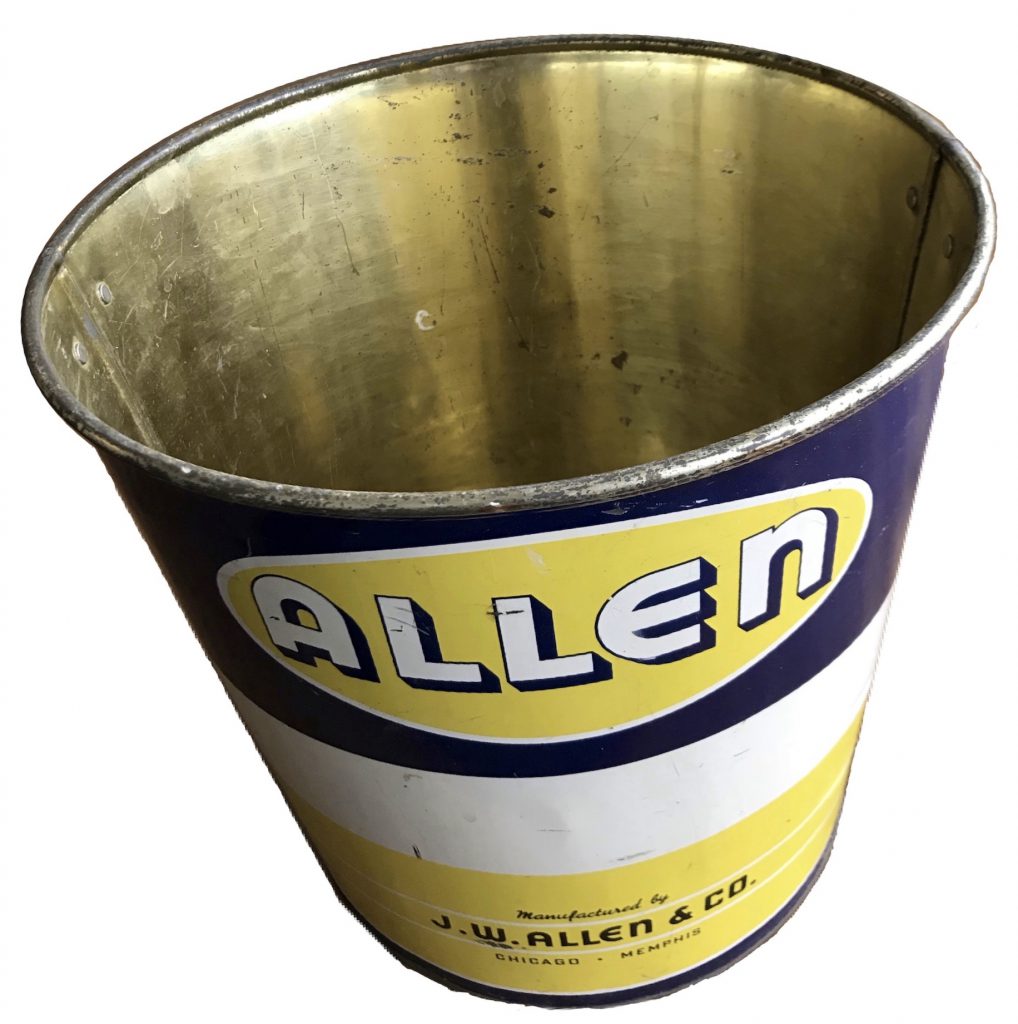

Museum Artifact: J. W. A. Ground Cinnamon Special – 5 LB Container (1930s) and Metal Baking Supply Pail (1940s)

Made By: J. W. Allen & Co., 110 N. Peoria St., Chicago, IL [West Loop]

“Our building in Chicago has come to be known as the acknowledged ‘Bakers’ Headquarters.’ We carry in stock and ready for immediate delivery practically everything required for the Baking Industry. This assures our customers with dependable service.”—J. W. Allen & Co. advertisement, 1921

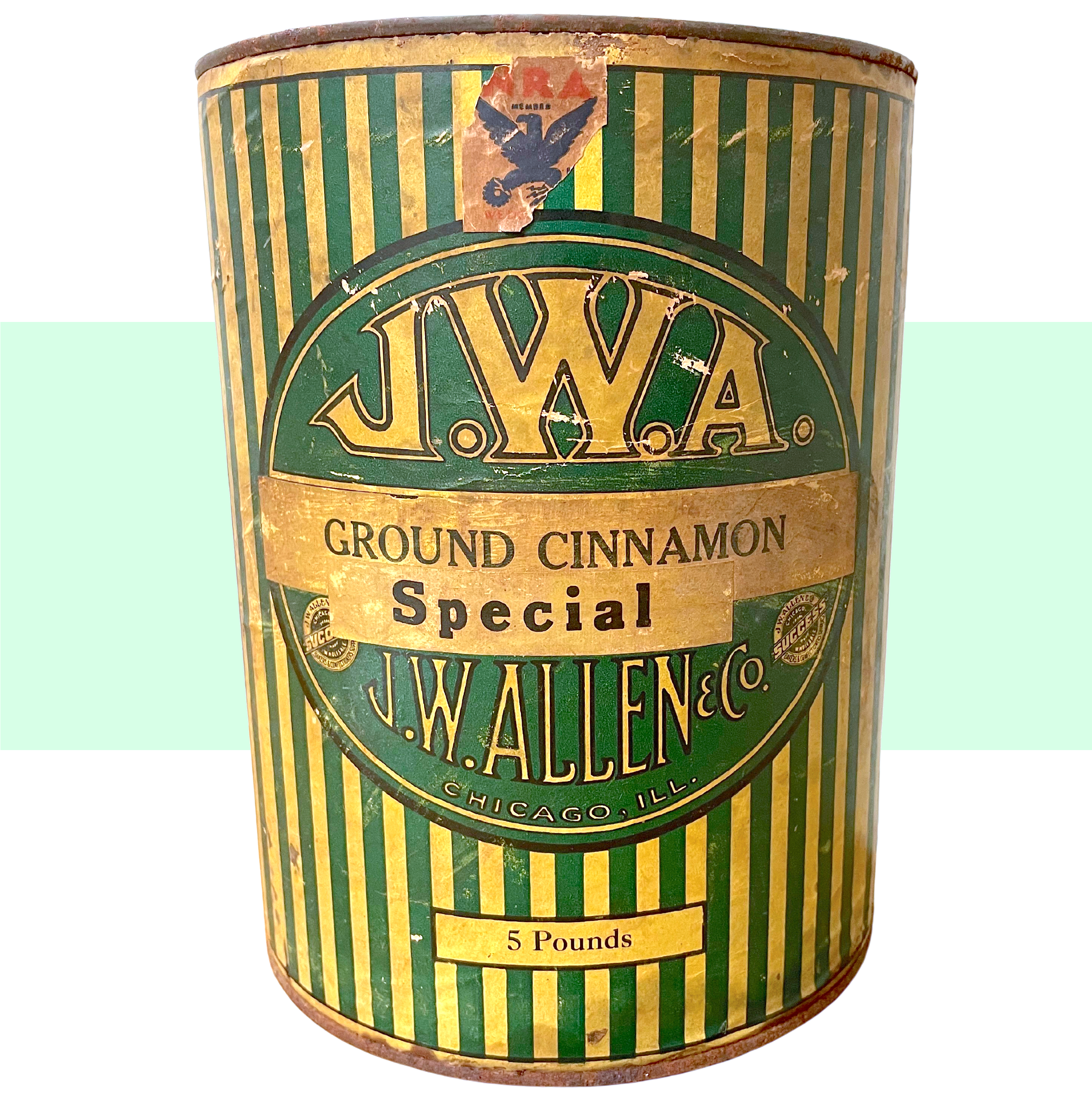

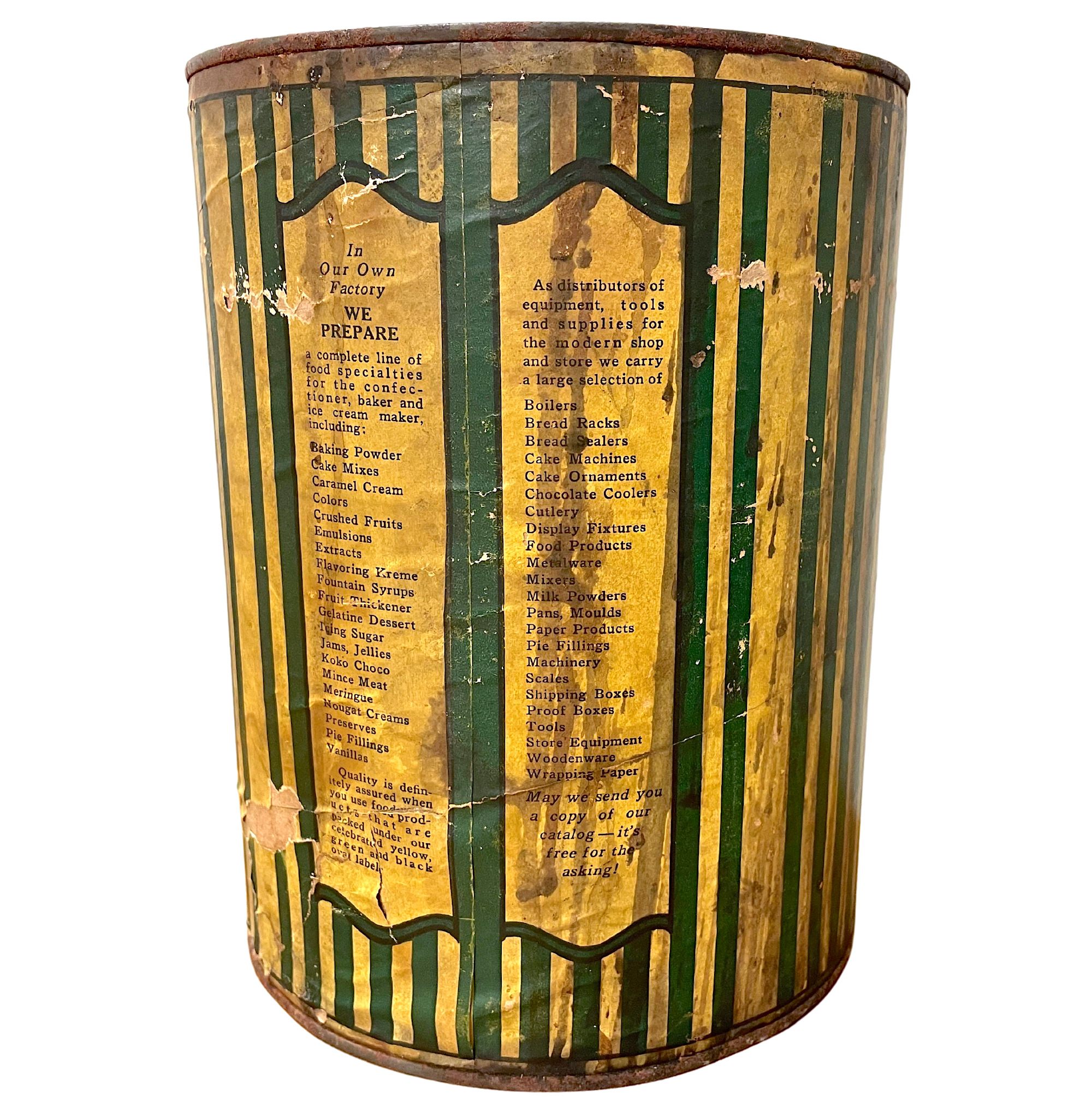

The name J. W. Allen has been associated with baked goods for nearly 140 years—and yet you’ve probably never knowingly eaten a single one of their cookies, cupcakes, or casseroles. Unlike the ubiquitous Betty Crocker or Pillsbury Dough Boy, Allen didn’t really cater to grandma’s kitchen cabinet of branded Americana. This Chicago-based family business was focused more on the professional ranks; selling wholesale supplies and bulk ingredients to bakeries, often packaged in big ugly feed bags or galvanized metal buckets. Occasionally, they also sent out snazzier candy-striped cylinders like the 5LB ground cinnamon container in our museum collection (the National Recovery Administration tag attached at the top indicates this particular artifact dates back to the 1930s).

The name J. W. Allen has been associated with baked goods for nearly 140 years—and yet you’ve probably never knowingly eaten a single one of their cookies, cupcakes, or casseroles. Unlike the ubiquitous Betty Crocker or Pillsbury Dough Boy, Allen didn’t really cater to grandma’s kitchen cabinet of branded Americana. This Chicago-based family business was focused more on the professional ranks; selling wholesale supplies and bulk ingredients to bakeries, often packaged in big ugly feed bags or galvanized metal buckets. Occasionally, they also sent out snazzier candy-striped cylinders like the 5LB ground cinnamon container in our museum collection (the National Recovery Administration tag attached at the top indicates this particular artifact dates back to the 1930s).

I suppose you might call Allen a “behind-the-scenes” operation, and as such, mainstream recognition wasn’t in the cards. But if John William Allen never had the celebrity status of Ms. Crocker and the Doughboy, he did at least have the advantage of being a real person.

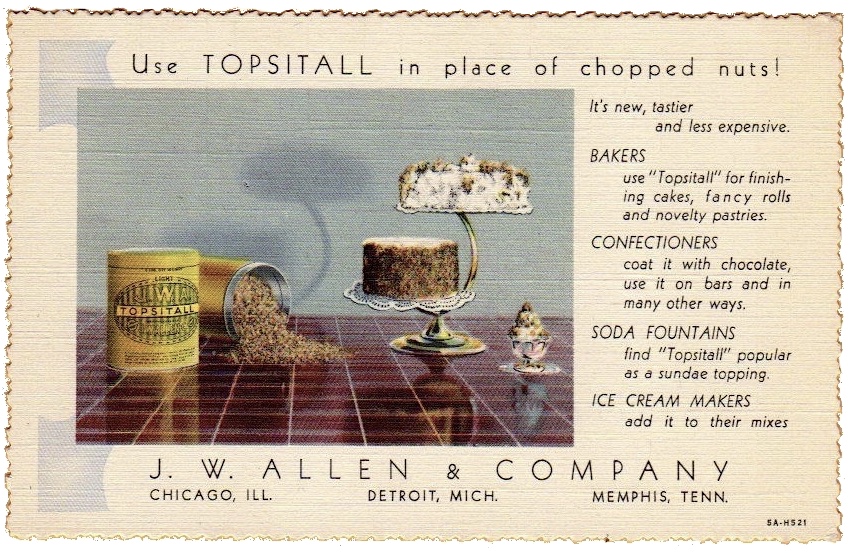

[Postcard advertisement for J. W. Allen’s “TOPSITALL” cake and ice cream topping, circa 1940. The same product was originally marketed as “Kripsy Krumbles”]

[Postcard advertisement for J. W. Allen’s “TOPSITALL” cake and ice cream topping, circa 1940. The same product was originally marketed as “Kripsy Krumbles”]

I. The Founder

In 1931, on the occasion of J. W. Allen & Co.’s 50th anniversary, the trade publication Glass Packer described the company’s origins as “the old, old story of a man—a tea clerk—who was not satisfied with the future that lay before him and believed the solution to his life’s problem was to go into business for himself. So J. W. Allen did just that.”

Believe it or not, that is a slight oversimplification of the tale.

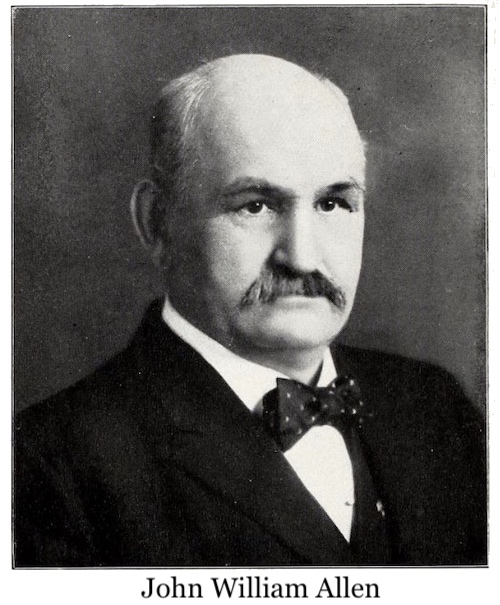

John William Allen (incidentally a dead ringer for J. P. Morgan) was born near Ann Arbor, Michigan, in 1848. Through much of his youth, he was “crippled and in impaired health”—according to the National Cyclopaedia of American Biography—but on the bright side, he was also slightly too young to fight and die in the Civil War. Instead, after overcoming some of his health concerns, Allen found work as a flour miller, helping to run a water-operated Michigan grist mill up until the age of 23. In early 1872, he headed west for Chicago at what might have seemed like a peculiar time to do so. The city was still knee deep in ash from the Great Fire and in the early stages of a very literal rebuilding mode. Rather than seeing this as a bleak predicament, though, J. W. was one of the youngsters tempted by a unique opportunity for a fresh start.

John William Allen (incidentally a dead ringer for J. P. Morgan) was born near Ann Arbor, Michigan, in 1848. Through much of his youth, he was “crippled and in impaired health”—according to the National Cyclopaedia of American Biography—but on the bright side, he was also slightly too young to fight and die in the Civil War. Instead, after overcoming some of his health concerns, Allen found work as a flour miller, helping to run a water-operated Michigan grist mill up until the age of 23. In early 1872, he headed west for Chicago at what might have seemed like a peculiar time to do so. The city was still knee deep in ash from the Great Fire and in the early stages of a very literal rebuilding mode. Rather than seeing this as a bleak predicament, though, J. W. was one of the youngsters tempted by a unique opportunity for a fresh start.

“Mr. Allen arrived with his life’s savings of $500, prepared to go into business for himself,” his grandson Frank W. Allen later wrote in a company newsletter, “but fate ruled otherwise. A pickpocket at the Michigan Central depot relieved him of his money, and his plans for business independence vanished with his savings.”

So, rather than the nice narrative of a young man who followed a whim and immediately struck it rich on the urban frontier, John W. Allen actually had to endure a full decade of grunt work with a Chicago tea and coffee merchant (Lyman and Silliman) before he’d finally earned back enough bread (pun intended) to take another crack at his baking supply business. Fortunately, this developmental period had aligned nicely with Chicago’s supercharged rebirth, and when the J. W. Allen firm was established in 1881, there were customers aplenty.

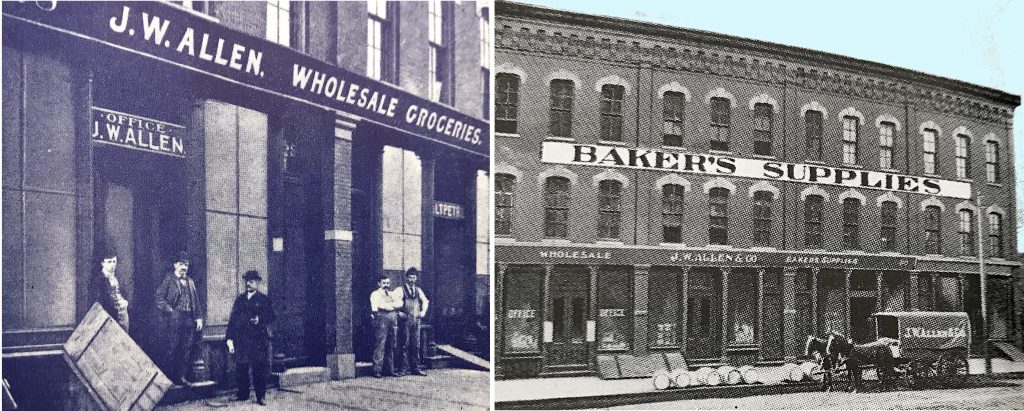

[The original J. W. Allen warehouse at Van Buren Street and Clinton Street, 1880s. John William Allen is pictured in the center of the image on the left.]

[The original J. W. Allen warehouse at Van Buren Street and Clinton Street, 1880s. John William Allen is pictured in the center of the image on the left.]

“During the night he bought his stock and made his goods,” according to Glass Packer. “By day, driving his own wagon, he sold. In the beginning his line was an odd assortment of butchers and bakers — even laundry supplies; but as time went on the money seemed to be in the bakery line and he dropped all but that one.”

By specializing in the sale of spices and extracts to local bakers and confectioners, Allen had pretty well pegged what would remain the core clientele of his family’s business for the next 100+ years. His first building, near the corner of Van Buren Street and Clinton Street in the West Loop, was a fairly humble enterprise, but after his son Harry W. Allen (1874-1933) joined the fold around 1892, J. W. widened his long-term ambitions, eventually relocating in 1900 to a larger five-story plant at 208-210 W. Washington Blvd. (845 W. Washington Blvd. by today’s street numbers).

Utensils and machinery were added to the catalog, and while much of the new manufacturing was outsourced to other businesses, J. W. saved more money by taking a controlling interest in where a lot of his food stuffs were coming from. The Meeker Sugar Refining Company, for example, was a Louisiana sugar mill that produced about 1,000 tons of cane per day—and as the newly anointed vice president of that concern, Allen could push a good chunk of its finished sugars and molasses right up the Rock Island Line to Chicago, essentially cutting out the middle man (or, more accurately, making himself the middle man).

Utensils and machinery were added to the catalog, and while much of the new manufacturing was outsourced to other businesses, J. W. saved more money by taking a controlling interest in where a lot of his food stuffs were coming from. The Meeker Sugar Refining Company, for example, was a Louisiana sugar mill that produced about 1,000 tons of cane per day—and as the newly anointed vice president of that concern, Allen could push a good chunk of its finished sugars and molasses right up the Rock Island Line to Chicago, essentially cutting out the middle man (or, more accurately, making himself the middle man).

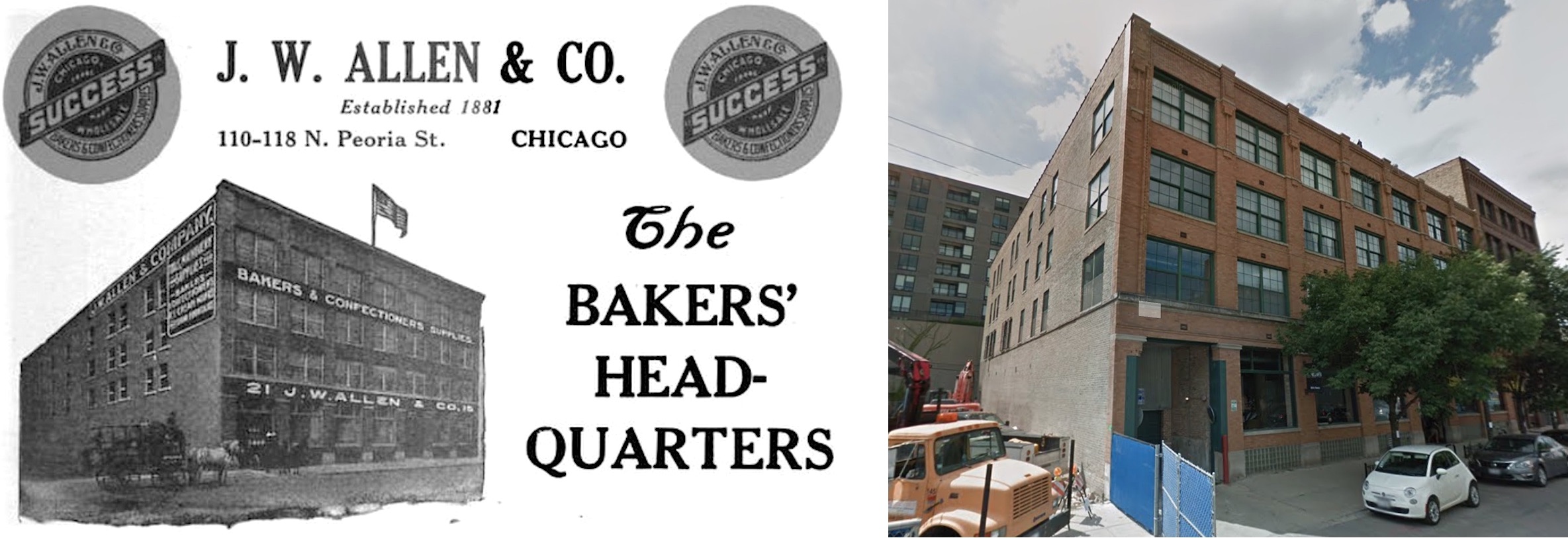

With son Harry elevated to partner status, the family business was officially incorporated as J. W. Allen & Co. in 1906—its 25th year in business. Four years after that, another wave of considerable growth inspired a move to the company’s first dedicated all-purpose plant—a modern four-story facility at 110 N. Peoria Street; aka, the “Baker’s Headquarters.” The building was designed by the architectural firm of Huehl and Schmid, and stood directly beside the warehouse of a rival baking supply business, Edward Katzinger & Co. (later to become the Ekco Products Co.). It would remain J. W. Allen’s central hub for the next 70 years.

[Then and Now: J. W. Allen plant at 110 N. Peoria Street. It was Allen’s HQ from 1910 to 1979, and has since been converted to swanky loft apartments.]

[Then and Now: J. W. Allen plant at 110 N. Peoria Street. It was Allen’s HQ from 1910 to 1979, and has since been converted to swanky loft apartments.]

Opening up the Peoria Street plant was arguably the last great achievement for John William Allen, who at 62, was nearing retirement in 1910. Noted in the National Cyclopaedia of American Biography for his charitable nature (the Allen family were major figures in the Presbyterian community of Oak Park) and “keen sense of humor,” he also had a “rigid standard of business honor and integrity . . . sound judgment and unfailing common sense.”

The 1912 book Chicago: Its History and Its Builders further hailed Allen as “an illustration of the fact that opportunity is open to all. With a nature that could not be content with mediocrity, his laudable ambition has prompted him to put forth untiring and practical effort until he has long since left the ranks of the many and stands among the successful few.”

J. W. Allen died in 1918, and his only son Harry had some big shoes to fill.

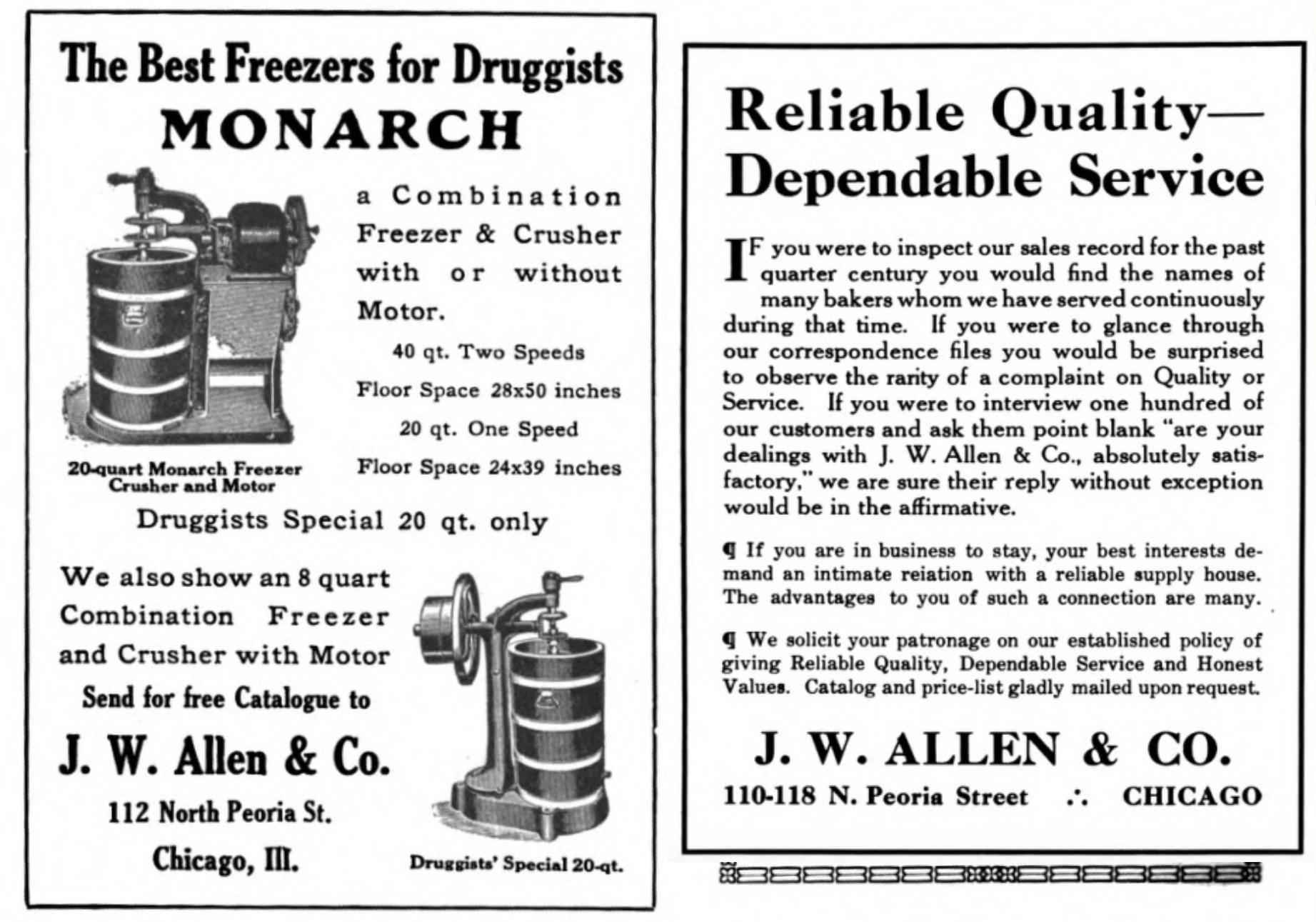

[J. W. Allen trade magazine ads from 1914 and 1916]

[J. W. Allen trade magazine ads from 1914 and 1916]

II. The Harry Era

“The thing which renders the supply house indispensable to the baking trade is the thing we excel in—SERVICE. Our large stocks and prompt attention to your needs enables us to lay emphasis upon this point in asking for your business.” —J. W. Allen ad, 1922

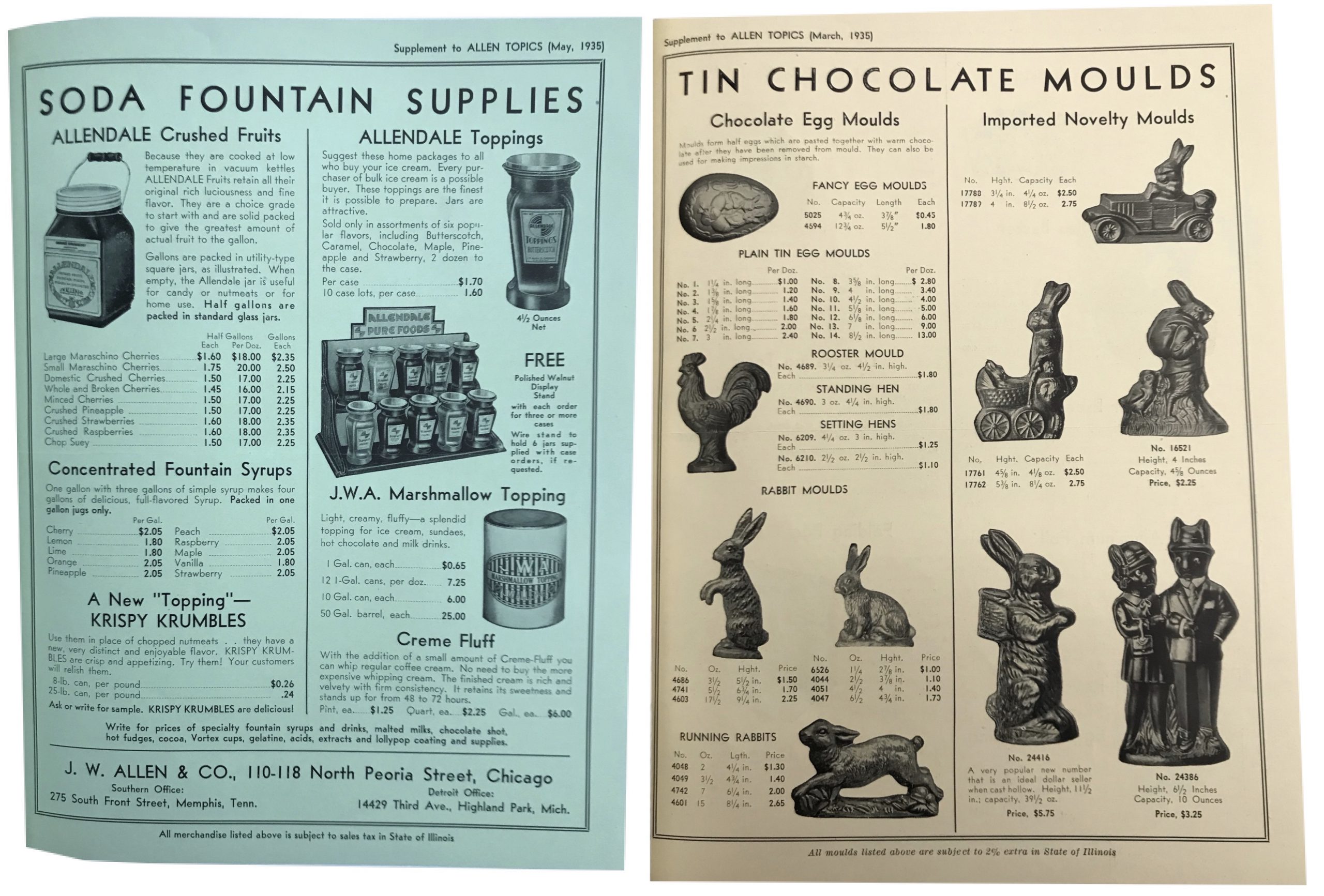

While Prohibition Chicago will inevitably elicit images of tommy gun shootouts and speakeasy raids, it was also a pretty glorious time for the bakery business. For people less inclined to run afoul of the law, new vices had to fill alcohol’s absence, and sugar was certainly a good one. As former bars and pool halls switched over to sweets and soda, Harry Allen proved he had his dad’s talent for serving his customers’ needs. The company reached out to non-traditional clients like hotels and factory cafeterias, offering everything from pails of nougat cream and gelatine to hi-tech ice cream freezers, stoves, and “pastry equipment.” With the capability to outfit facilities on a large scale, Allen collected more than 5,000 independent clients by the early ‘20s.

While Prohibition Chicago will inevitably elicit images of tommy gun shootouts and speakeasy raids, it was also a pretty glorious time for the bakery business. For people less inclined to run afoul of the law, new vices had to fill alcohol’s absence, and sugar was certainly a good one. As former bars and pool halls switched over to sweets and soda, Harry Allen proved he had his dad’s talent for serving his customers’ needs. The company reached out to non-traditional clients like hotels and factory cafeterias, offering everything from pails of nougat cream and gelatine to hi-tech ice cream freezers, stoves, and “pastry equipment.” With the capability to outfit facilities on a large scale, Allen collected more than 5,000 independent clients by the early ‘20s.

“Regardless of where you are located,” read a 1927 ad, “if in the United States, you can buy from J. W. Allen & Co. just as conveniently and satisfactorily as a confectioner who is in the immediate vicinity of Chicago—the supply center of America.”

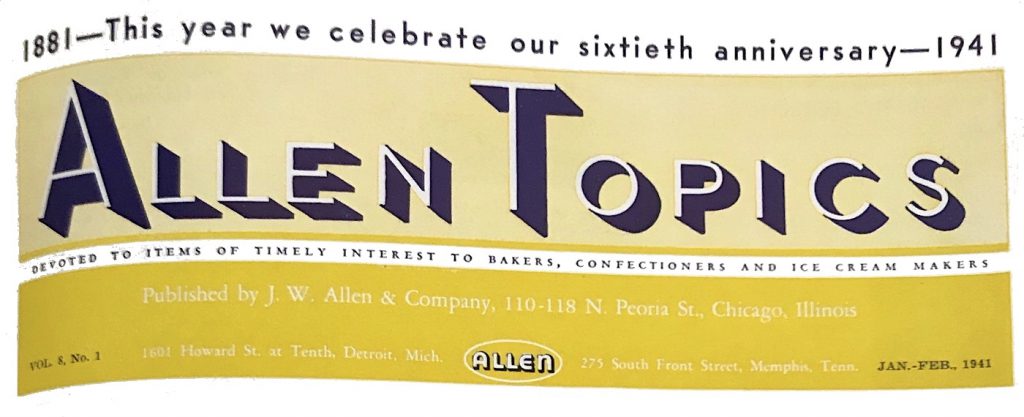

Allen opened up a preserving plant dedicated to jams and jellies in the ‘20s, and satellite factories opened in both Memphis and Detroit by 1933. The main Chicago plant, though, remained the company’s pride and joy. While 110 N. Peoria Street might have lacked some of the fancier frills of other West Loop industrial facilities of the period, it was run with extreme care and efficiency.

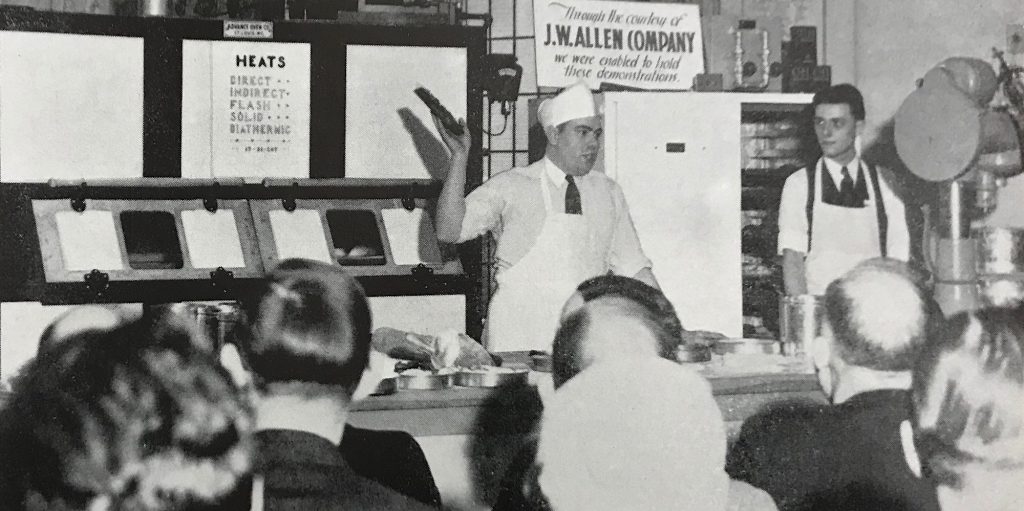

[Top Left: The “Baker’s Room” inside 110 N. Peoria St., dedicated to demonstrations of J.W.A. products. Bottom Left: Giant mixer at the Peoria Street plant could blend 2,500 pounds of flour at a time; the key to making Allen’s “Feather-Fluff Donut Flour.” Right: Allen employee Alex Nielens displaying an Advance Revolving Tray Oven at a baking convention in the 1930s]

[Top Left: The “Baker’s Room” inside 110 N. Peoria St., dedicated to demonstrations of J.W.A. products. Bottom Left: Giant mixer at the Peoria Street plant could blend 2,500 pounds of flour at a time; the key to making Allen’s “Feather-Fluff Donut Flour.” Right: Allen employee Alex Nielens displaying an Advance Revolving Tray Oven at a baking convention in the 1930s]

“The one outstanding highlight of this factory is the fact that it is a money maker,” Glass Packer observed in 1931—an achievement hardly on trend with the time period. “The management states that there is just one reason for this — its equipment policy. Labor eats up the very slender margin of profit in the highly competitive preserve business; so H. W. Allen, president of the company, and J. G. Ford, its general manager, are both committed to the policy that whenever a machine can be found or an installation devised that will shave a cent off production costs—out goes the old machine, be it ever so new, and in goes the newer. Few manufacturers have the courage to scrap their machinery in that cold blooded fashion.”

Harry W. Allen’s hardline philosophies kept J. W. Allen & Co. thriving in the early years of the Depression, when much of its competition was collapsing. But the effort may have involved sacrifices to his own personal health.

Harry W. Allen’s hardline philosophies kept J. W. Allen & Co. thriving in the early years of the Depression, when much of its competition was collapsing. But the effort may have involved sacrifices to his own personal health.

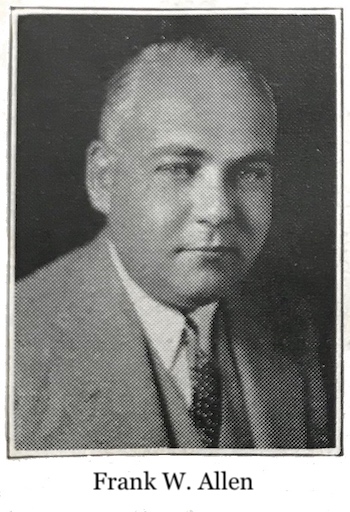

H. W. died in 1933 at the age of just 58, resulting in his own son—34 year-old Frank W. Allen—becoming the third president in the company’s history.

“My father carried on the traditions of the business, seeing it prosper in good times and bad,” Frank later wrote. “I can only regret that he could not have lived to see this enterprise expand its activity. How proud he would have been to see the steady progress that has been made.”

[Workers outside J. W. Allen’s satellite plant in Detroit, 1940. They also had a facility in Memphis, TN.]

[Workers outside J. W. Allen’s satellite plant in Detroit, 1940. They also had a facility in Memphis, TN.]

III. Frank Speaks Frankly

Frank W. Allen (1899-1969) was a Northwestern grad (his education likely kept him out of World War I service) and a dedicated student of his dad and grandpa’s formulas for success. He seemed to value the opportunity to connect personally with employees and clients, too, even penning a regular column for years in the company’s monthly newsletter, Allen Topics.

“Each year our activities become more diversified,” he wrote in the March 1934 edition, during his first full year as president. “To our main business of supplying essentials we have added other services. We manufacture a full line of quality food specialties. An affiliated company processes glace fruits and peels. A contract department takes care of shop and store installations and remodeling. Another division looks after machinery. We even have our own pecan shelling plant in the South.”

“Each year our activities become more diversified,” he wrote in the March 1934 edition, during his first full year as president. “To our main business of supplying essentials we have added other services. We manufacture a full line of quality food specialties. An affiliated company processes glace fruits and peels. A contract department takes care of shop and store installations and remodeling. Another division looks after machinery. We even have our own pecan shelling plant in the South.”

Frank wasn’t shy about expressing frustration, either, whether it was decrying the “ruinous competition of cheap Canadian bread” in the ‘30s or new restrictions on the baking business enacted by the government during World War II, including major increases in the cost of flour.

In the first Allen Topics after Pearl Harbor, F. W. wrote that “From now on, America’s biggest business enterprise is that of winning the war.” But within two months, he felt the need to stick his neck out and discuss what he admitted might be a more “controversial subject.” “We are in a tough war,” he wrote, “and obviously, many conditions are going to be hard to meet. For that reason I think it very reasonable that we avoid pussy-footing in talking about many phases that concern us directly. In the conduct of this war it should not be necessary for an individual or group of business men to give up entirely the right to earn a livelihood, as now seems to be expected of the retail baker and of retail bakers as a group.”

Frank had more than flour costs to worry about when his own son John—a student at Dartmouth College—went off to fight in the Philippines in ’45. Fortunately, after V-J Day in August, John was soon among the many men happily returning to the comparatively blissful scene over at 110 North Peoria Street.

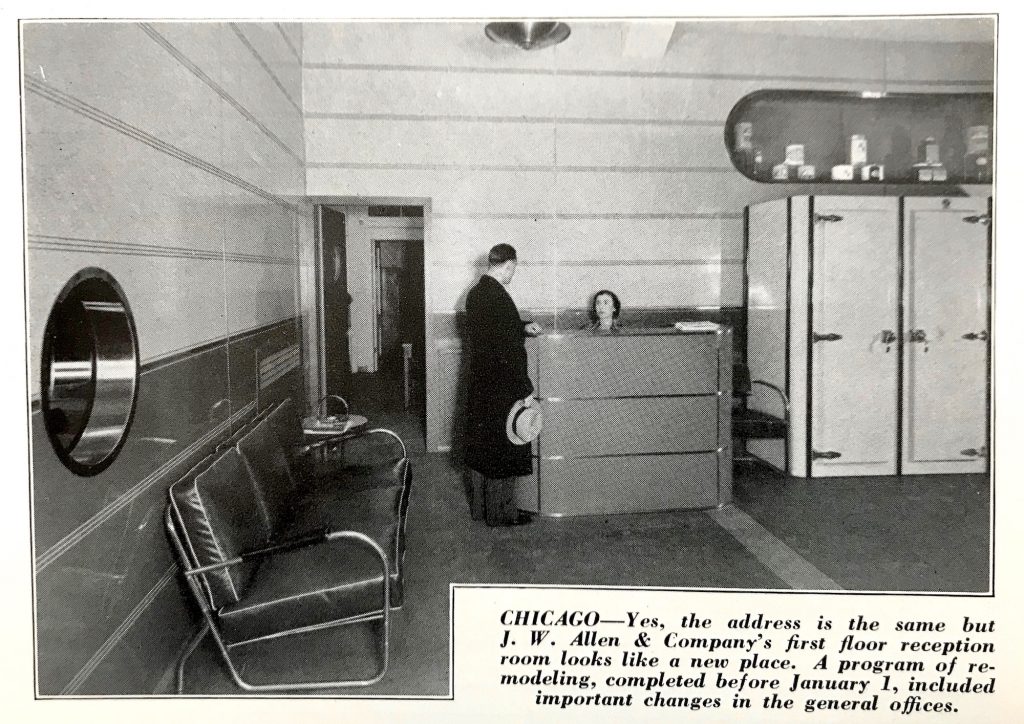

[Clip from a 1941 edition of Allen Topics reveals how the reception room of the Peoria Street plant looked during the WWII years]

[Clip from a 1941 edition of Allen Topics reveals how the reception room of the Peoria Street plant looked during the WWII years]

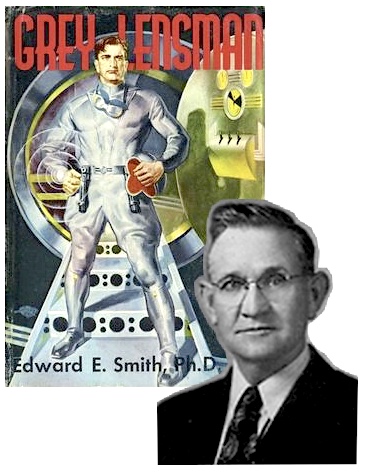

The Chicago factory’s peacetime posse also included a minor celebrity of sorts—pulp sci-fi writer Edward E. Smith (aka E. E. “Doc” Smith), whose various pre-war “space operas” are often credited with influencing George Lucas’s concept for Star Wars years later. Interestingly, Smith wasn’t brought to J. W. Allen & Co. as a copywriter. As a holder of a couple chemical engineering degrees, he had worked for the U.S. Military during the war, and was recruited for his skills in food science rather than science fiction. Among his supposed, unsubstantiated accomplishments in that field: inventing the powdered donut.

“On October 1, 1945, I came to Chicago as manager of the Cereal Mix Division of J. W. Allen & Co.,” Smith explained to his readers in an issue of the sci-fi magazine Other Worlds later that year. “It’s the biggest and best job I ever had. It has only one drawback—unfortunately, I can’t write stories on company time.”

“On October 1, 1945, I came to Chicago as manager of the Cereal Mix Division of J. W. Allen & Co.,” Smith explained to his readers in an issue of the sci-fi magazine Other Worlds later that year. “It’s the biggest and best job I ever had. It has only one drawback—unfortunately, I can’t write stories on company time.”

Smith might have been writing less, but he managed to get a publishing contract during his time with J. W. Allen anyway, and many of his old works from the popular magazine Amazing Stories (a favorite of Lucas and Steven Spielberg) were put out in book form by Fantasy Press in the late ‘40s and early ‘50s, including the Lensman and Skylark series. These dime novels ultimately helped secure the donut scientist’s unlikely cult status.

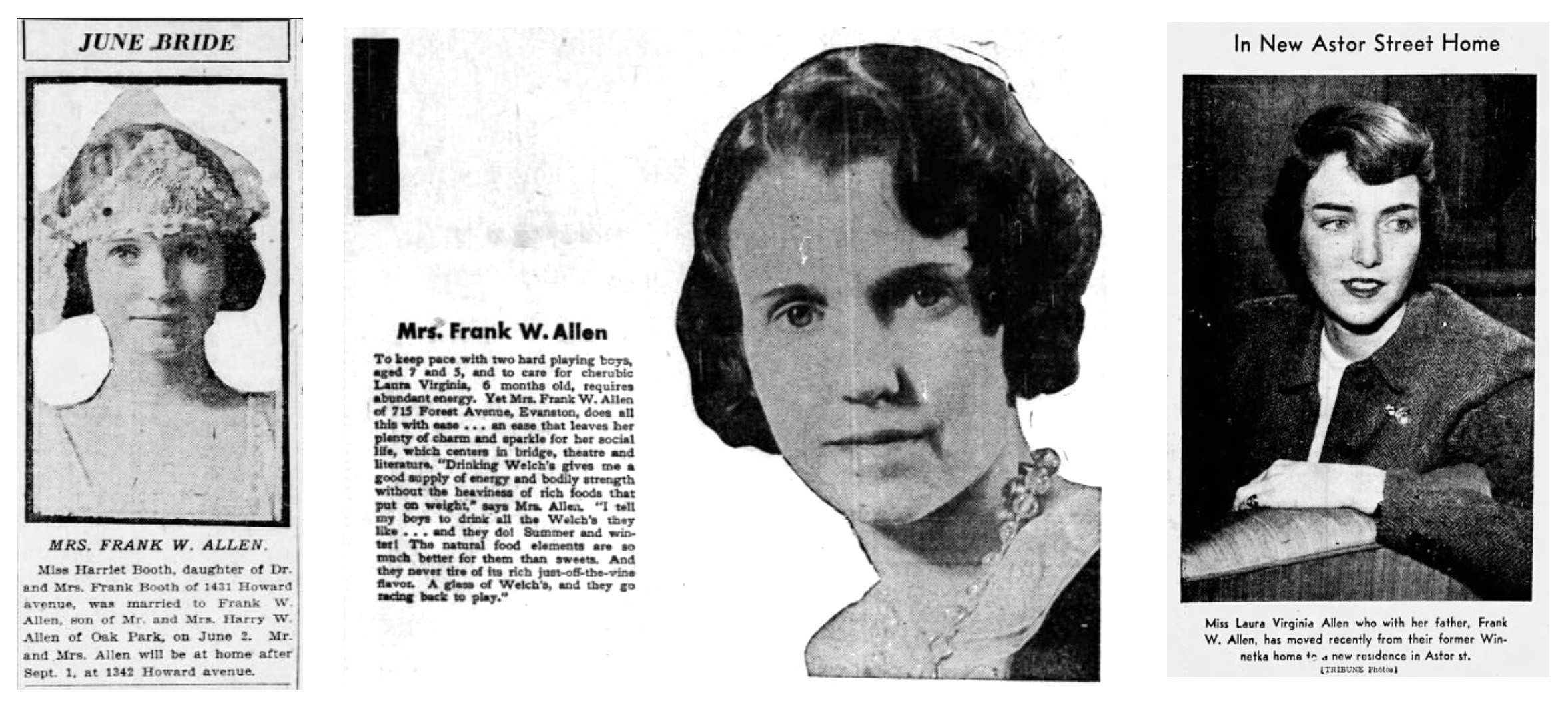

[The women in Frank W. Allen’s life: His wife Harriet, seen in a newspaper announcement of their wedding in 1921 (left) and in a testimonial for Welch’s Grape Juice in 1931 (center), and daughter Laura Virginia (right) in 1951. Harriet died in 1947 at just 49 years of age; Laura lived to be 71 (1930-2001)]

[The women in Frank W. Allen’s life: His wife Harriet, seen in a newspaper announcement of their wedding in 1921 (left) and in a testimonial for Welch’s Grape Juice in 1931 (center), and daughter Laura Virginia (right) in 1951. Harriet died in 1947 at just 49 years of age; Laura lived to be 71 (1930-2001)]

IV. A New J. W.

The aforementioned war vet John W. Allen (1923-2000) added a masters degree from Dartmouth’s Tuck School of Business to his resume in 1947, and by 1962, he’d ascended to the presidency of J. W. Allen & Co., with papa Frank moving to chairman. By that point, 38 year-old John W. was already serving as president of the National Bakery Suppliers Association, and his reputation as an innovator was firmly established.

Like his namesake 80 years earlier, John Allen had an adventurous spirit, including a passion for competitive sailing that he later passed down to his own sons. The competitive approach applied to his work, as well, as he continuously explored new avenues and became “recognized as a pioneer in retail baking”—according to the unbiased analysis of his own Tribune obituary in 2000.

[J. W. Allen’s “Model Bake Shop,” as presented here at a 1940s baker’s convention in St. Louis, was the precursor to the company’s move into becoming a complete service provider for chain store bakeries in the ’60s and ’70s]

[J. W. Allen’s “Model Bake Shop,” as presented here at a 1940s baker’s convention in St. Louis, was the precursor to the company’s move into becoming a complete service provider for chain store bakeries in the ’60s and ’70s]

It’s hard to imagine, but in the 1960s, supermarket bakeries were a rarity rather than the rule—only about 1,000 even existed by 1970. John W. anticipated a spike in that market, however, and aimed a lot of J. W. Allen & Co.’s resources toward addressing these upstart operations.

“We decided not to just sell a product,” John’s son Bill Allen recalled years later, “we would sell a service.”

Half a century earlier, J. W. Allen & Co. had marketed itself as the “House of Service,” but this modern approach was a new animal. Rather than just selling bakers the equipment and ingredients they needed, Allen’s team now acted as an agent for these new chain bakeries, fully outfitting their facilities and instructing managers on marketing, merchandising, and employee training.

“They didn’t know how to do any of that in the beginning,” Bill Allen added, talking to the Daily Herald in 1998. “We were helping create a market for ourselves . . . also, by supplying everything, it was a good way to keep competitors out.”

“They didn’t know how to do any of that in the beginning,” Bill Allen added, talking to the Daily Herald in 1998. “We were helping create a market for ourselves . . . also, by supplying everything, it was a good way to keep competitors out.”

Sure enough, as the number of U.S. supermarket bakeries skyrocketed in the ‘70s, the 100 year-old Allen company reaped the benefits, experiencing its largest profit margins ever in a time when a lot of old, stately Chicago manufacturers were shutting down their plants entirely.

Technically speaking, Allen did shut down the Peoria Street plant in the late 1970s, but it was less out of necessity and more for modernization. The old factory was no longer a vision of efficiency, and a more typical sprawling complex in suburban Wheeling, Illinois, fit the bill better. Weep not for 110 N. Peoria, though. It was given new life, like so many of its ilk, as a loft apartment complex, and still retains much of its original industrial charm.

[One of the current apartments inside the former J. W. Allen plant at 110 N. Peoria Street]

[One of the current apartments inside the former J. W. Allen plant at 110 N. Peoria Street]

V. Allens Get Rich and Rich Gets Allen (The End)

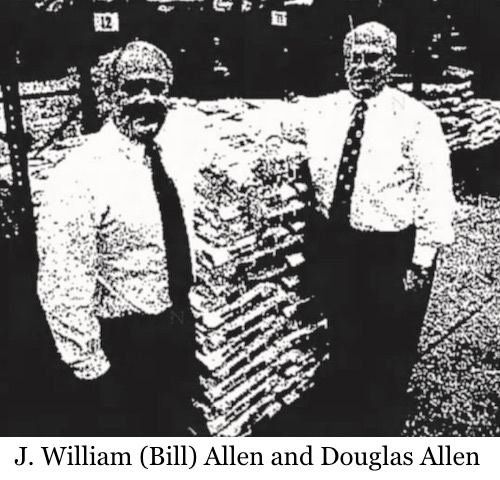

By 1998, when fifth generation company heads John William Allen, Jr. (aka Bill) and Douglas Allen were profiled by Chicago’s Daily Herald, the family business was pulling in $110 million in revenue annually ($40 million in frozen cake manufacturing alone), and had grown 18-fold overall since 1970. There were also 180 workers employed at the Wheeling plant, and another 270 or so at five other national locations.

And this, surprisingly, is where the story comes to an abrupt end.

Following John W. Allen Sr.’s retirement in 1998 (he died two years later), his sons were left to ponder a next course of action. Both kids had been raised with a reverence for the business their great-great-grandfather had founded, but they’d also been raised on racing yachts—exploring the international high seas. As adults, Bill became a trained oceanographer, and Doug, a marine biologist. They loved a good bulk raspberry jelly shipment as much as the next guy, but it might not have been their life’s passion.

Following John W. Allen Sr.’s retirement in 1998 (he died two years later), his sons were left to ponder a next course of action. Both kids had been raised with a reverence for the business their great-great-grandfather had founded, but they’d also been raised on racing yachts—exploring the international high seas. As adults, Bill became a trained oceanographer, and Doug, a marine biologist. They loved a good bulk raspberry jelly shipment as much as the next guy, but it might not have been their life’s passion.

It’s also possible they had their ancestor’s keen business instincts, and knew that selling high—while maybe less adventurous than buying low—was still sometimes just the best way to roll one’s dough.

And so today, J. W. Allen lives on only as a brand, rather than a man or a business. The family firm was sold to the Rich Products Corporation of Buffalo in 1999, which in turn has kept some lines of Allen mixes, icings, and fillers in their arsenal. The Wheeling plant, however, was shutdown in 2012.

[The former J. W. Allen plant at 555 Allendale Ave. in Wheeling, IL]

[The former J. W. Allen plant at 555 Allendale Ave. in Wheeling, IL]

[52 executives and salesmen of J. W. Allen attending a dinner at Chicago’s Union League Club in the 1930s]

[52 executives and salesmen of J. W. Allen attending a dinner at Chicago’s Union League Club in the 1930s]

Sources:

Allen Topics newsletters, 1934-1943 – Chicago History Museum

“H. W. Allen Dead, Head of Bakers’ Supply Company” – Chicago Tribune, June 5, 1933

“Half Century Mark Passed This Year by J. W. Allen Company” – Glass Packer, Vol. 4, 1931

“A Rich Ending for J. W. Allen Bakery-Goods Firm” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 11, 1999

“John W. Allen elected president of J. W. Allen & Co.” – Chicago Tribune, March 21, 1962

“John William Allen” – Chicago: Its History and Its Builders, Vol. 4, by Josiah Seymour Currey, 1912

“John William Allen” – National Cyclopaedia of American Biography, 1922

“Chicago Notes” – Confectioners’ and Bakers’ Gazette, v. 21, 1900

Notable Men of Illinois and Their State, 1912

“Brothers Give Up Life of the Sea to Sail Into a Family Tradition” – Daily Herald (Chicago), June 10, 1998

Allen Logo – Trademark – Justia

John William Allen II obituary – Chicago Tribune, Feb 17, 2000

Is Bill Allen still alive.

My name is Brad Smith, started with J.W. Allen in 1985i the Burnsville, Mn warehouse. I knew About J. W. Allen as I worked for Kristico inc. They were a distributor of JWA and I pick up in Burnsville evert week.

I was transferred to Orlando, Fl in 1987 as branch manager, In 1996 in was transferred to Morristown, Tn

Frozen plant As distribution manager. I knew John and Bill and always felt like family around them. I stayed on after the sale in 1999 and worked for Rich Products Corp. until I retired in 2019.

After the sale the Family aura was gone. I will alway remember my talks with John.

I worked for JW Allen in Memphis from April 85 til October 86 Warehouse men and Truck Driver Making Delivers to Kansas, Missouri,Tennessee Arkansas Oklahoma Alabama Florida. They wanted me to take the Distribution Managers job in Dallas Tx I turned it down they cut my pay by hiring a part time driver to make the delivery runs I was making and was gonna keep me in the warehouse only. I quit and took a job at Yellow Freight in Memphis worked there for 28 years .Retired with a Teamster pension in 2013. If the The area manager had have not cut my pay and delivery runs out I probably would have stayed. The Guy was a asshole I remember his name was Pete a miltary guy.. Thank you Pete you did me a favor.

In the 1.999, I worked for a Wheat Milling company in Brazil. One of my duties was to develop a new portfolio of products. I pushed the family to negotiate a new business that would add value to the milling product.

The best way wasn’t to invent the new wheel but to use oil to lubricate a pre-existent one. My dream was to produce J.W.Allen in Brazil. Unfurtanetelly they sold the company to Rich’s from Buffalo, a lovely company as well. Regards to Bill and Douglas

I was lucky to get to work for the Allen family. I started in June of 1979 night shift Warhouse worker at the Peoria street in Chicago location. Then when the Wheeling location opened I was there aswell on nights. The night shft ended and everyone was moved to days. In 1986 I received a promoton to Distribution Manager to the Dallas Texas area. In 1996 I had to sad duty to close that location but the family moved me to the Orlando Florida warehouse. In 1999 the family sold this was truly a sad day. The Allen family always treated you as if you were part of their Family. Around late 2005 The new owners decided to close all the Distribution warehouses I chosen to close the other locations. Memphis TN Allentown Pa Burnsville MN. One lasst trip to the Wheeling location to turn in all the keys and papework from the closings. To this day I have a picture of John Allen and my father at my fathers retirement party on my wall. Yes my father worked there aswell and waas hired by Frank Allen.

I found a box of “Cookie Dockers” at a yard sale in Tucson, AZ. They are a collection of wooden cookie stamps. Found J W Allen on the box and was delighted to find this article explaining everything about this amazing company.

1. What is the origin of the name “cookie dockers”?

2. What years were they produced?

Thanks to the author for putting all this info together in one place.

I worked for J.W. Allen at the distribution center in Fogelsville Pa from 1991 to 1996 and I enjoyed my job so much! What a great company to work for. Joe Dinelli was the branch manager and my interview for the job was with Pete Hafner and Diane Baker. I remember when we were invited to Chicago overnight to see the facility and the Seminar and I learned so much working for the company. During the last 5 yrs. I started my own Home Bakery and work full time for the Cable Company. I am hoping to retire in about 8 yrs. and then continue with my Home Bakery (SweetsbyJacqueline). I have a question about the pension plan if anyone can help, please contact me at SweetsbyJacqueline57@gmail.com. Thank you for the memories!

I was employed at a very famous ice cream store in wilmette on chicago’s north shore making ice cream.We (Steve the owner and I) started work most days at 5:30 am! the restaurant staff and other managers could never figure out why Steve and I left about 2:00 in the afternoon. I told the staff if they wanted to leave at 2:00, all they had to do was to be at work at 5:30 am!. We bought most of our colors from JW and it was always a pleasure seeing Bill at the yacht club racing sailboats. We both had good laugh when we discovered we had two commonalities: food service and racing sailboats!!

bill fox

I worked as a customer service rep at the Wheeling Plant in the late 70’s. One of my favorite jobs. I reported to Jessie, can’t recall his last name. Also worked with a Ruth. I remember her husband worked there for many years also. Can still remember the great smell of bread and the donut sampling was the best! Great memories!

This is Douglas W. Allen, as cited in this article. Bill (my brother) and I are the fifth generation. My son actually found this website. Very Interesting. To you Debbie, Harold was much admired and a key to our bakery training programs around the country. That part was not mentioned but I have other information which was not touched on in this article. I would be happy to share it with anyone and would like to get in touch with the authors of this article.

To Andrew Clayman, please contact me. I think I could add more to the story and would like to contact you. at least to complete my story that I am writing for the next generation.

Thank you and I look forward to hearing from you. I will send you my email address below. Send me an email and I will give you my cell phone number. Both Bill and I still live in the Chicago area.

Hi Douglas, I certainly welcome any corrections and new details you’d like to add on the company’s history. Will be in touch. –Andrew Clayman

Would like to contact Bill Allen. My father Harold Julian worked with him for years. Bill knew me as Debby Davis. Could you give me his contact information.