Museum Artifact: Tailor’s Measuring Tape, c. 1930s

Made By: Kling Bros. & Co. Inc., 2300 W. Wabansia Ave, Chicago, IL [Wicker Park]

“Garments that combine character and charm with lines that are clean cut, comfortable, and correct. . . . Are you one of the ten thousand dealers who know the immeasurable satisfaction to be found in KLING-MADE clothing specialties?”—1920 ad for Kling Bros. & Co.

Kling Bros. & Co. (not to be confused with their local contemporaries, the wholly unrelated Kling Bros. Engineering Works) was one of Chicago’s most successful wholesale tailoring businesses in the early 20th century. Started, in typical fashion, as a single independent shop powered by highly skilled immigrant labor, the business would eventually partner with or absorb many of its competitors in the custom clothing trade, selling an ever-expanding line of “Klingmade” coats, suits, sweaters, vests, bathrobes, uniforms, and swimwear.

Kling Bros. & Co. (not to be confused with their local contemporaries, the wholly unrelated Kling Bros. Engineering Works) was one of Chicago’s most successful wholesale tailoring businesses in the early 20th century. Started, in typical fashion, as a single independent shop powered by highly skilled immigrant labor, the business would eventually partner with or absorb many of its competitors in the custom clothing trade, selling an ever-expanding line of “Klingmade” coats, suits, sweaters, vests, bathrobes, uniforms, and swimwear.

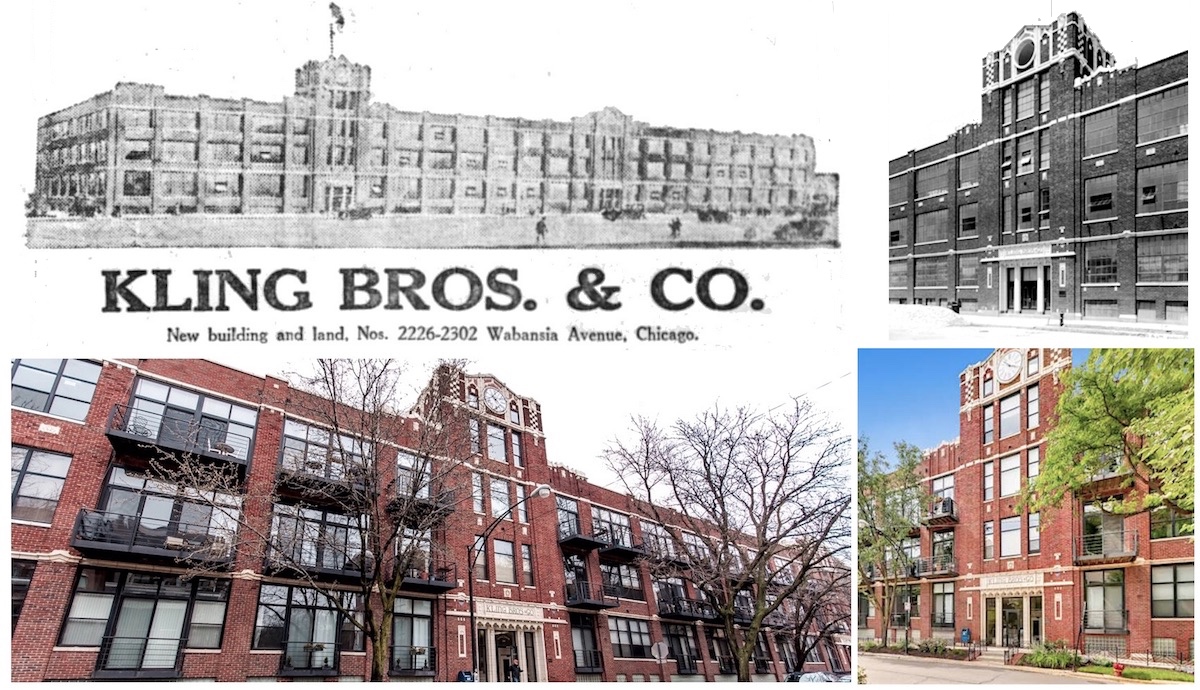

From a modern perspective, there can be an appealing middle-class glamour to Kling’s goods; harking back to a time when Chicagoans seemingly wore their “Sunday best” for every random jaunt to the post office. In 1920, when the company opened its impressive 200,000 sq. ft., terra-cotta laden factory at 2226 W. Wabansia Avenue, they seemed to be the model enterprise for the industry. Behind the scenes, however—in the midst of violent uprisings from clothing workers unions and a losing battle with cheaper “ready-to-wear” styles—the brothers Kling were in a fight for their livelihoods. And sometimes, that led to some dirty pool.

[Current view of the former Kling Brothers factory at 2300 W. Wabansia Ave. in Wicker Park. It was opened in 1920 and converted into the “Clock Tower Lofts” in the 1990s]

[Current view of the former Kling Brothers factory at 2300 W. Wabansia Ave. in Wicker Park. It was opened in 1920 and converted into the “Clock Tower Lofts” in the 1990s]

History of Kling Bros. & Co. – Part I. Dressed for Success

Samuel Kling (1875-1967) and Leopold Kling (1878-1962)—the two brothers in question—were Jewish immigrants from the town of Dauendorf in Alsace-Lorraine; a French region that had recently come under German control after the Franco-Prussian War. In Victorian Europe, Jews played a disproportionately large role in the tailoring trade, albeit usually as low-wage labor. The middle class and multilingual Klings (including oldest brother Kauffmann and baby sister Babette) may have had a few more advantages than their mishpacha further east, however, thus setting them up for a better life way out west.

Samuel emigrated to America in 1892, at just 17, and he was followed two years later by Leopold, who, at 16, already had a degree from a business college. In 1897, the baby-faced brothers formed their first stateside tailoring shop in Chicago’s West Loop at 118 S. Halsted. When the business was more properly organized as Kling Bros. & Co., Leopold, despite being the younger one, was president; Sam was treasurer. They adapted their first company logo into the Star of David, unashamedly advertising their heritage. Jewish immigrants faced no shortage of bigotry, but in the tailoring trade, their reputation for quality work served as a selling point.

Samuel emigrated to America in 1892, at just 17, and he was followed two years later by Leopold, who, at 16, already had a degree from a business college. In 1897, the baby-faced brothers formed their first stateside tailoring shop in Chicago’s West Loop at 118 S. Halsted. When the business was more properly organized as Kling Bros. & Co., Leopold, despite being the younger one, was president; Sam was treasurer. They adapted their first company logo into the Star of David, unashamedly advertising their heritage. Jewish immigrants faced no shortage of bigotry, but in the tailoring trade, their reputation for quality work served as a selling point.

We don’t actually know if the Klings had much skill with a needle and thread themselves, but they certainly recognized good work and knew how to sell their wares. By no coincidence, their business quickly gained traction—building a national sales team and working out arrangements with like-minded manufacturers, jobbers, and retail merchants. From the looks of it, Kling Bros. & Co. would take in bulk articles from various affiliates (coats from a coat factory, pants from a pants factory, etc.), send out its salesmen to flag down clients, then put its own in-house staff to work making alterations with high-tech new electric sewing machines. Eventually, the company started producing more of their own clothes from scratch, requiring repeated factory upgrades.

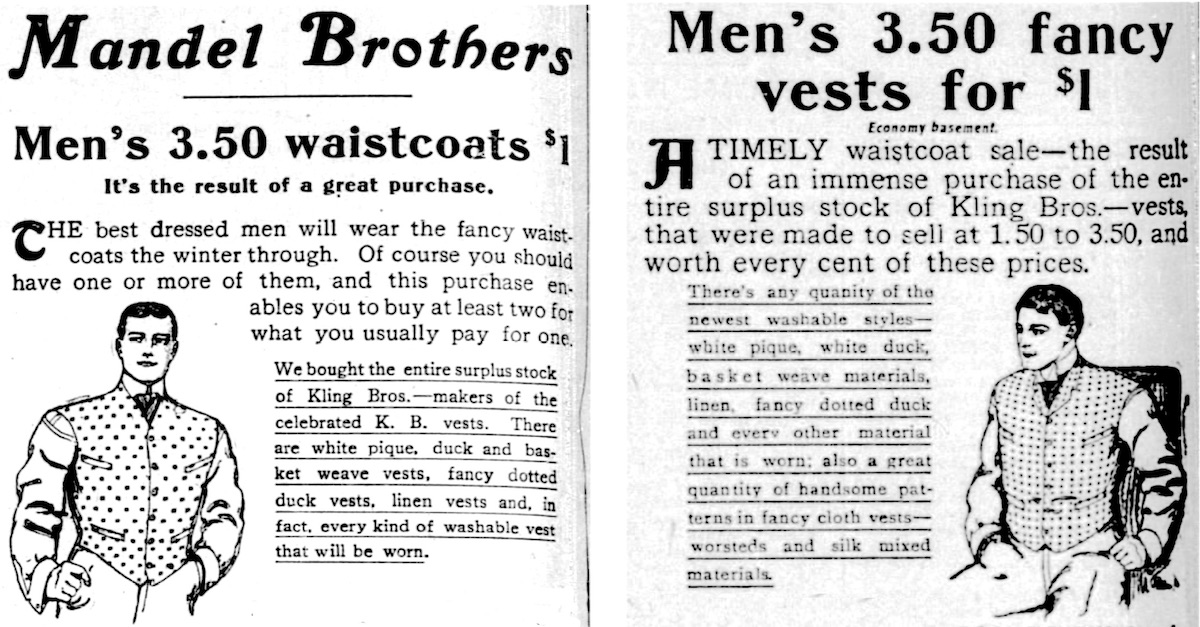

[Above: Kling Bros. classified ad from 1902, noting the storefront on Halsted and factory on Market Street. Below: 1903 advertisements for Chicago’s Mandel Brothers department store (State & Madison), featuring “fancy vests” from the “surplus stock of Kling Bros.—makers of the celebrated K.B. vests.”]

By 1902, Kling Bros. & Co. had 50 employees—39 of them women—working at its main plant at 159 Market Street (a road later erased by Wacker Drive). They then took over the former headquarters of another wholesale tailor, Lamm & Co., at 282 Fifth Ave., in 1904, and by 1906, had a whole network of manufacturing facilities operating under the Kling banner: 45 workers at 899 Milwaukee Ave, 25 at 328 Ohio Street, and 90 more at 862 N. Robey Street.

“Kling Bros., specialty clothing, Chicago, have increased their sales the past season, it is stated, 40 percent,” Men’s Wear magazine reported that year. “This is a phenomenal increase, but they are anxious to make the coming season even greater than the past, and have put on additional men to those already on their force. They are going into the South especially strong,” the article added, noting the hiring of new Kling reps in Birmingham, New Orleans, Houston, and parts of Mississippi, Kentucky, Arkansas, and Tennessee.

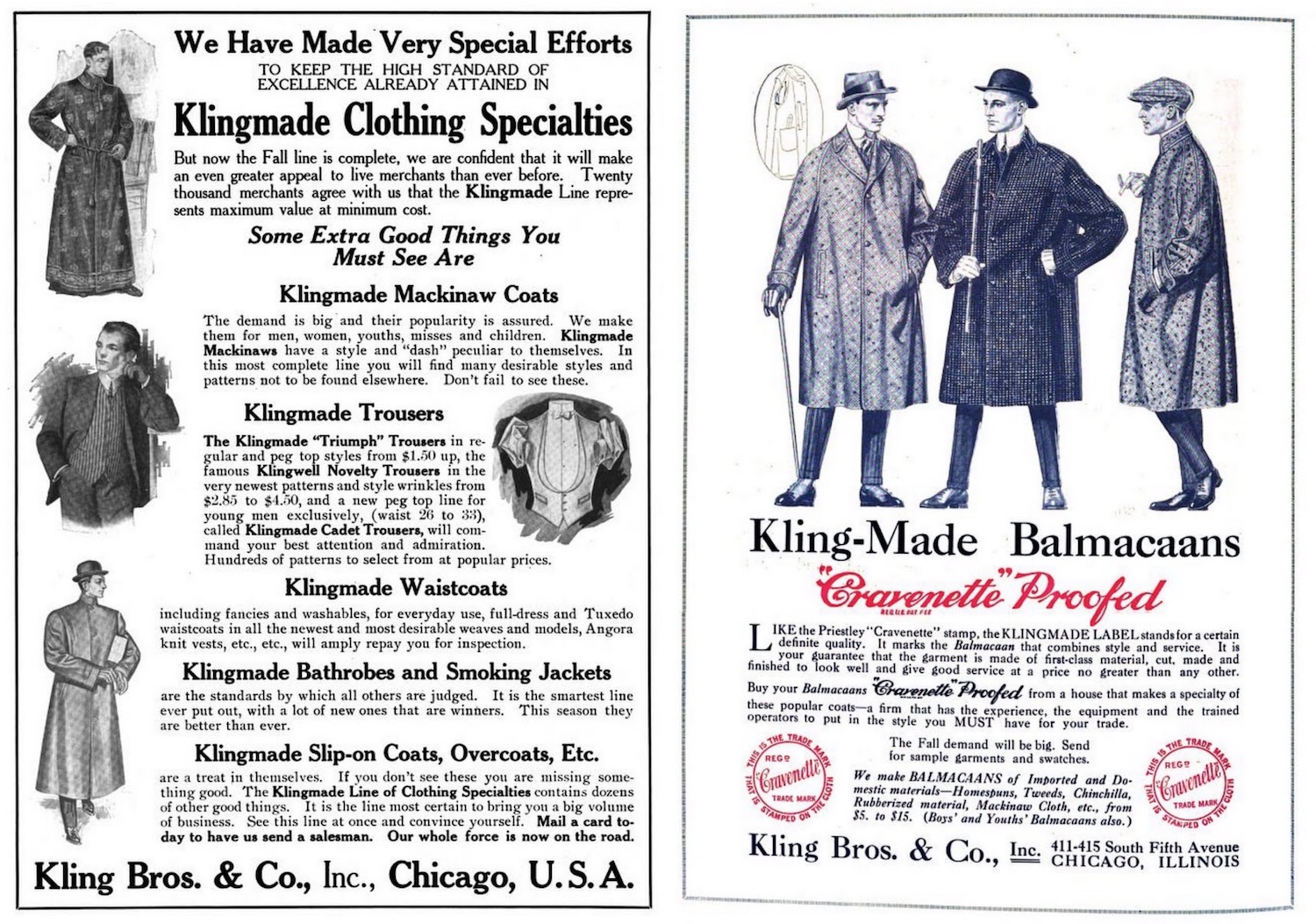

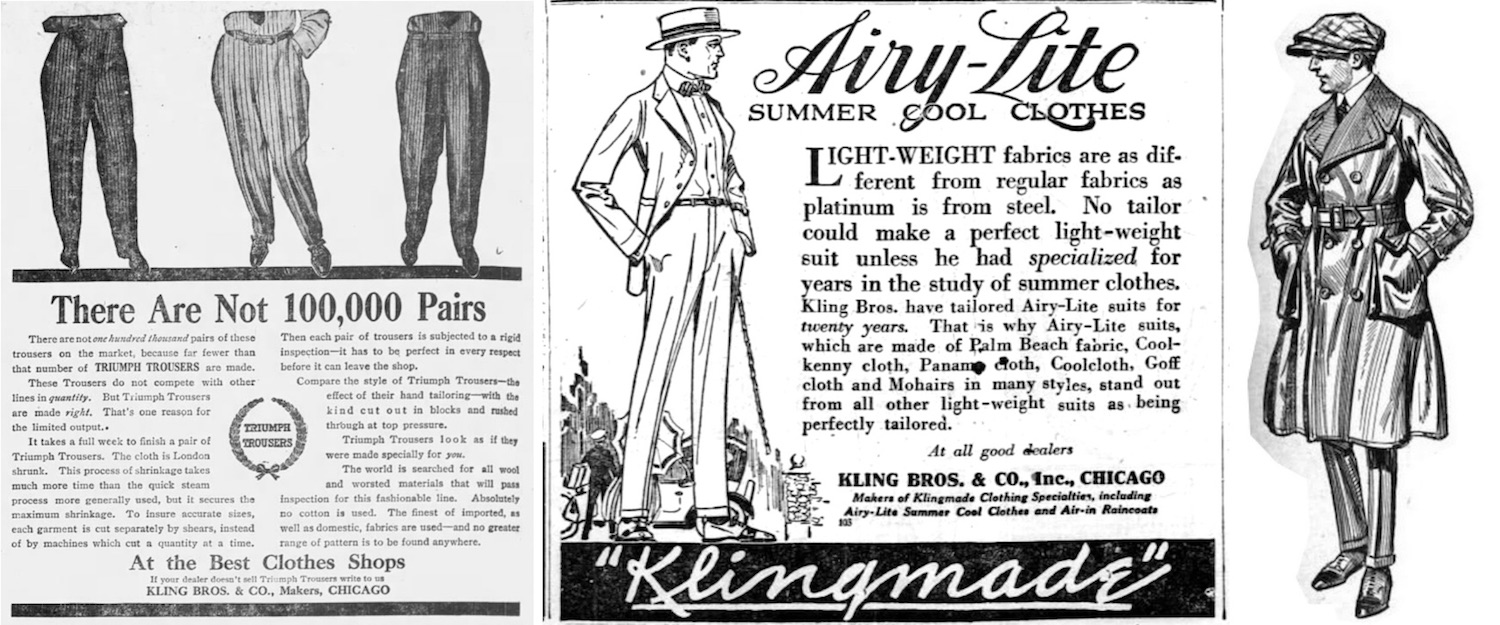

[Pre-war “Klingmade” magazine ads from 1910 and 1914]

[Pre-war “Klingmade” magazine ads from 1910 and 1914]

Kling’s specialties in its early years included “white duck” clothing (thick white canvas fabrics used in military trousers and the cricket attire of posh British dandies), along with “fancy vests,” waiters’ jackets, mackinaw and balmacaan coats, bathrobes, and something called “Triumph Trousers.” It all combined to paint a pretty clear picture of Kling’s target audience: the pre-Gatsby preppy set, America’s new 20th century breed of cane-wielding urban snob, or admirers thereof. Then again, who doesn’t look good in a balmacaan?

II. Clashing Patterns

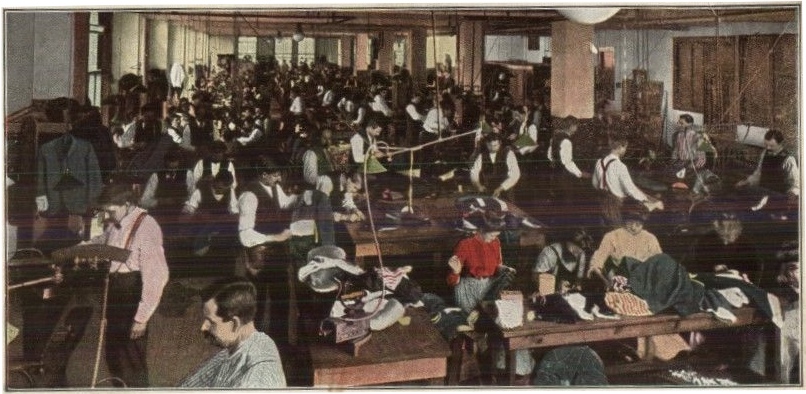

For the workers inside Kling’s Chicago tailoring factories, of course, the life was decidedly less luxurious than the styles. The clothing industry, as a whole, ranked as the third largest in Chicago and the number one employer of women by far, but conditions were predictably rough and pay predictably insulting. Some of the larger wholesale tailors, including Kling Bros., did have arrangements with the United Garment Workers of America and proudly printed the union label in their clothes. But in some respects, this was used more as a marketing ploy—to show consumers that skilled labor had produced their clothes in sanitary conditions (an important selling point in a world still reeling from Upton Sinclair’s revelations).

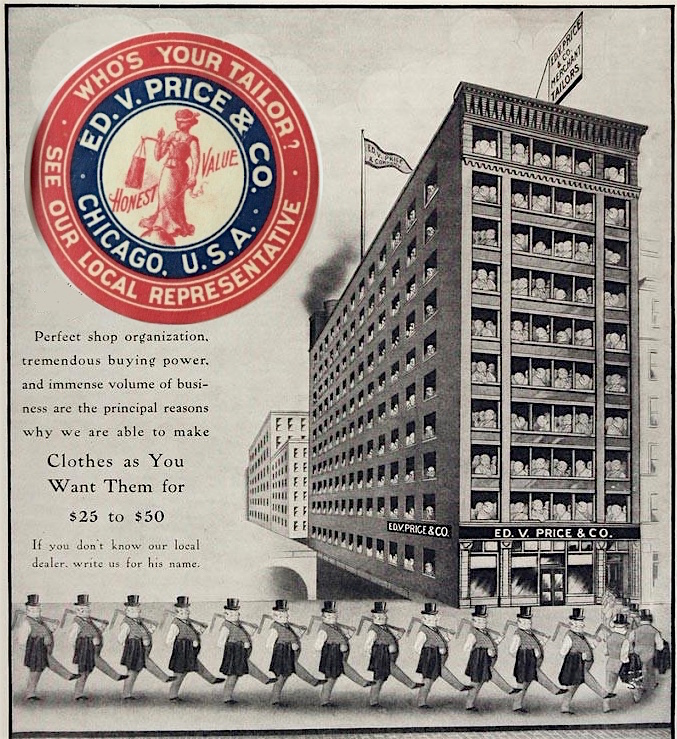

[Tailors at work, circa 1910, inside the coat shop of a Kling Bros. competitor, Ed V. Price & Co.; a company Leopold Kling would later take over]

[Tailors at work, circa 1910, inside the coat shop of a Kling Bros. competitor, Ed V. Price & Co.; a company Leopold Kling would later take over]

On the side, meanwhile, most employers were still saving money by recruiting fresh-off-the-boat, non-unionized immigrants (often displaced Jews from the Klings’ part of the world) and signing them to bogus “piece rate” contracts—meaning, rather than a salary, workers were paid slim wages based on how much product they moved out. Many workers were pushed beyond 12 hours a day, or else, asked to continue their work at home, extending the “factory” into the tenement buildings.

This could only go on unchecked for so long.

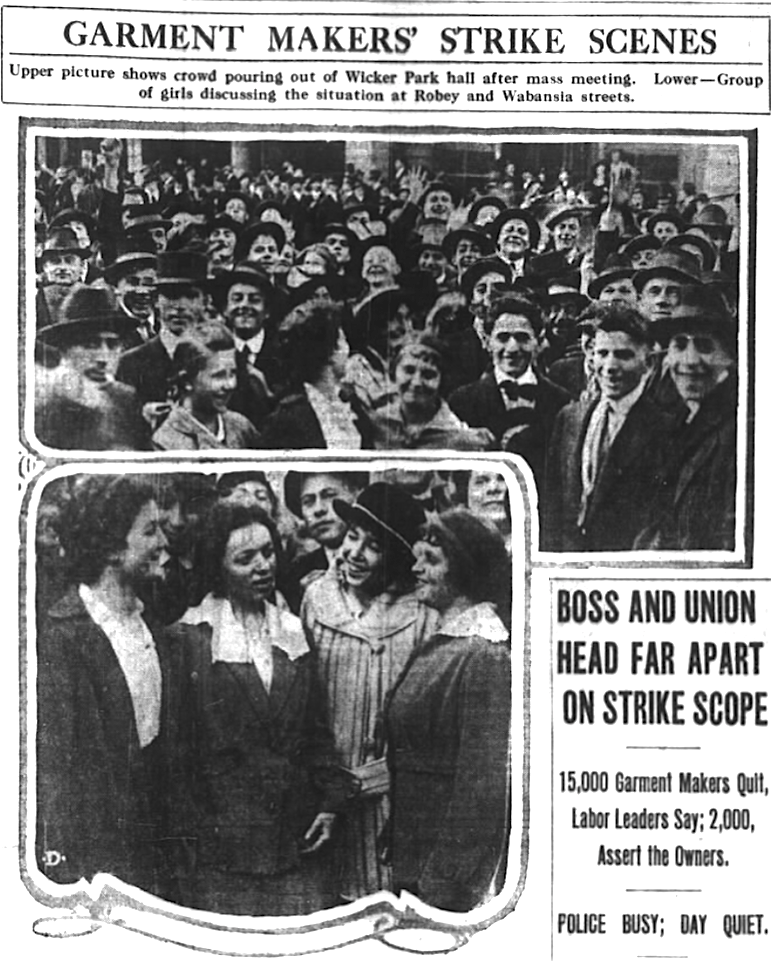

Taking inspiration from the many labor uprisings that had revolutionized other industries around the turn of the century, Chicago’s clothing workers began their rebellion in 1910, when a Jewish woman named Bessie Abramowitz—a button sewer at the major suit-maker Hart Schaffner & Marx—led a walkout with 15 other women. This soon snowballed into a movement across the city, with thousands of striking clothing workers demanding better treatment, often clashing violently with police and other anti-union antagonists in the process (five people were killed over several months). Abramowitz and her fellow organizer and future husband Sidney Hillman eventually won a victory, leading to their creation of a stronger, more progressive labor union: the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America.

Taking inspiration from the many labor uprisings that had revolutionized other industries around the turn of the century, Chicago’s clothing workers began their rebellion in 1910, when a Jewish woman named Bessie Abramowitz—a button sewer at the major suit-maker Hart Schaffner & Marx—led a walkout with 15 other women. This soon snowballed into a movement across the city, with thousands of striking clothing workers demanding better treatment, often clashing violently with police and other anti-union antagonists in the process (five people were killed over several months). Abramowitz and her fellow organizer and future husband Sidney Hillman eventually won a victory, leading to their creation of a stronger, more progressive labor union: the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America.

The fight wasn’t over, however. While Hart Schaffner & Marx had complied with a new labor agreement in 1911, the other big clothing houses weren’t eager to follow suit, and dug their heels in.

When union organizer Fannia Cohn was asked, in 1915, what the average salary was for a woman in a Chicago clothing factory, she responded: “Not enough to live on. It’s the same old story. Six dollars a week is a high average wage. If the girl lives at home she may not need more. If the girl must room and buy her meals, then her best economy cannot keep her from hungry stomach and tattered dress.”

And so, in 1915, another wave of strikes began, with the Ladies Garment Workers joining the Amalgamated Clothing Workers in demanding “outrageous” stuff like: overtime pay, holidays off, collective bargaining rights, a maximum 48-hour work week, and minimum wages ($26 a week for trimmers, $20 for cutters, $20 for examiners and bushelmen, and $8 for apprentices). The Wholesale Clothiers’ Association scoffed at all of it, claiming that most workers were actually very pleased with their situations, and that the unions were corrupting their minds with a false sense of injustice. With no compromise in sight, the walk-outs continued.

And so, in 1915, another wave of strikes began, with the Ladies Garment Workers joining the Amalgamated Clothing Workers in demanding “outrageous” stuff like: overtime pay, holidays off, collective bargaining rights, a maximum 48-hour work week, and minimum wages ($26 a week for trimmers, $20 for cutters, $20 for examiners and bushelmen, and $8 for apprentices). The Wholesale Clothiers’ Association scoffed at all of it, claiming that most workers were actually very pleased with their situations, and that the unions were corrupting their minds with a false sense of injustice. With no compromise in sight, the walk-outs continued.

“Forty raincoat makers just struck at Harrison Raincoat Co., 766 W. Harrison, manufacturers for Kling Bros., 5th av. near Congress,” the Day Book newspaper reported that August.

“’A year ago, the company cut prices 50 per cent,’ said M. Rapaport, executive board member of the union. ‘When we struck the company promised it would resume the old scale when the busy season came. Busy season came; still halved wages. So men struck last week. Old wages were restored, and men returned to work only to buck up against unfair discrimination and bullying foremen. Conditions became so intolerable men had to walk out again yesterday. If Kling Bros. don’t insure a square deal we’ll call strike at six other factories doing work for them.'”

Clearly, our pals Leopold and Samuel weren’t above the fray during this tumultuous time. Their plants—along with those of competitors like Royal Tailors, Lamm & Co., Fred Kaufman, and Alfred Decker & Cohn—were beehives of descent, strong-arming, and instability, even if ownership (benefit of the doubt) might have thought they had the best interests of their fellow immigrant workers in mind.

[15,000 Chicago clothing workers joined in a parade on October 12, 1915, as part of an ongoing strike that fall]

[15,000 Chicago clothing workers joined in a parade on October 12, 1915, as part of an ongoing strike that fall]

“The clothing manufacturers have been given ample opportunity to settle this controversy amicably and have denied our request for a conference,” AGW’s president Hillman said at the time. “We have been forced into this fight by the uncompromising attitude of our employers and we are in it to stay until the clothing workers are accorded a voice in fixing their wages and working conditions.”

During the fall of 1915, more than 25,000 Chicagoans walked out and took to the streets, largely with the support of the general populous. Unlike some other large-scale labor movements of the same period, the clothing workers also maintained a united front across races, ethnicities, and pay grades. They were led largely by Jewish organizers who “would not allow nationality and skill divisions to fuel tensions in workers’ ranks,” according to Lizabeth Cohen’s book, Making a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919-1939. “They made deliberate efforts to recruit Poles, Italians, and even those blacks who worked in the trade through publishing weekly papers in numerous languages, employing organizers from these communities, and encouraging representatives of different nationalities to serve as union officers.”

“The bosses will try to play one race against another,” union leader Sam Levin said. “. . . The Amalgamated must coordinate the different races in a harmonious whole.”

“The bosses will try to play one race against another,” union leader Sam Levin said. “. . . The Amalgamated must coordinate the different races in a harmonious whole.”

These efforts didn’t immediately pay off in 1915, but by the spring of 1919, with veterans returning from World War I and a new era at hand, the entire Chicago clothing market was finally forced to organize under new standards, including across-the-board pay raises and a 44-hour work week—a historic victory for the labor unions.

Leopold and Samuel Kling might have been miffed or just relieved to be done with the battle. Either way, their focus quickly shifted to peacetime profiteering.

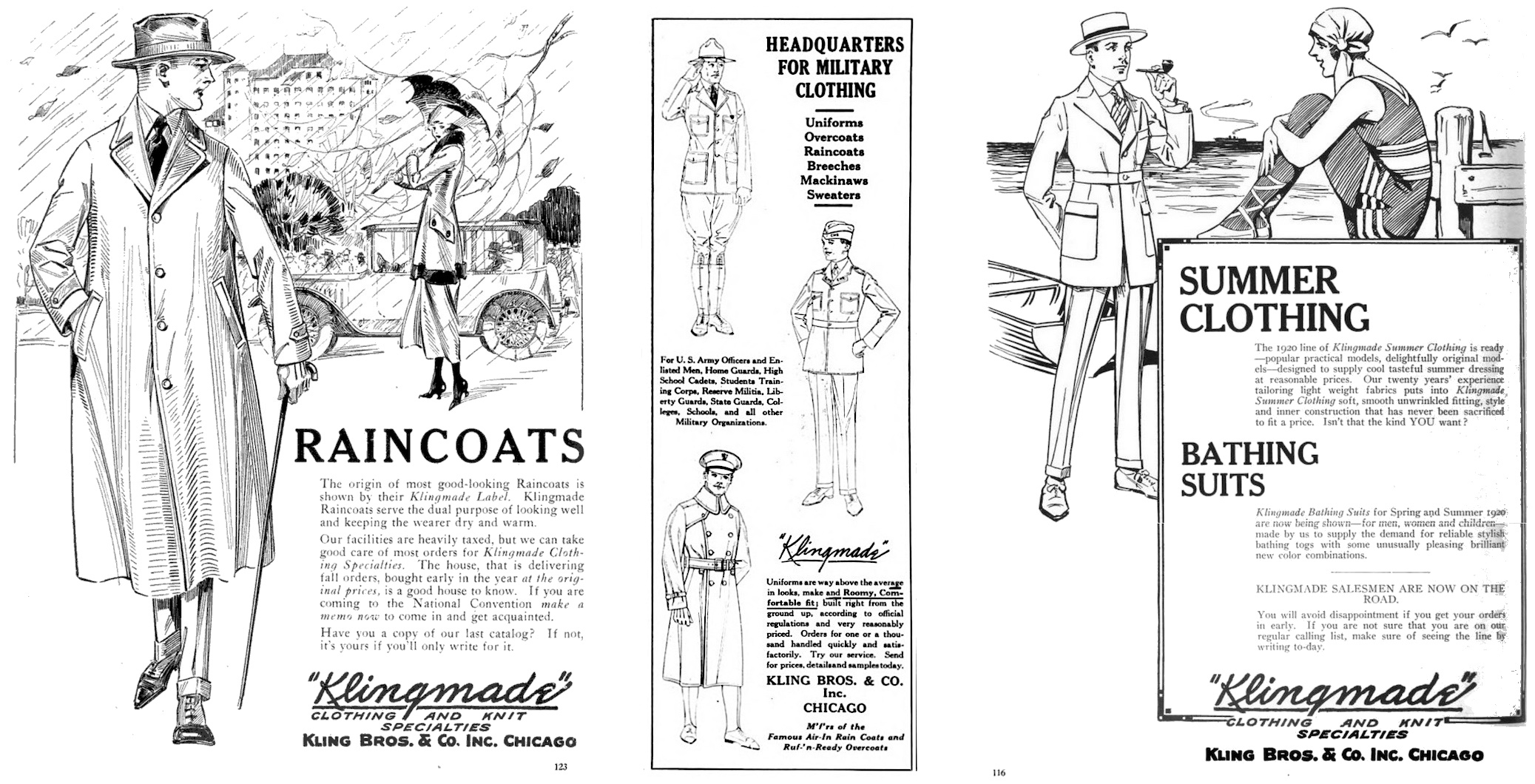

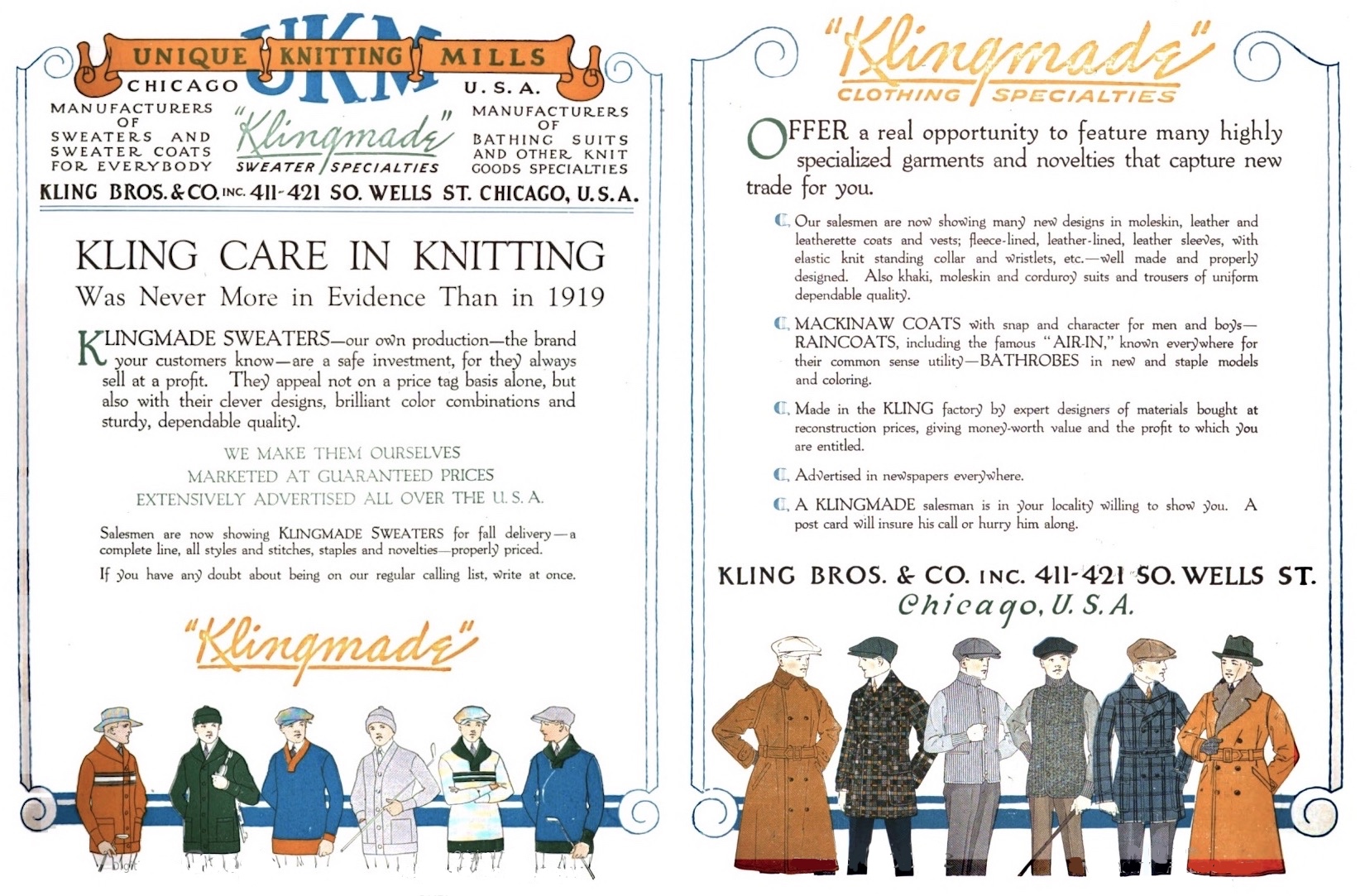

[Kling Brothers advertisements from 1919]

[Kling Brothers advertisements from 1919]

III. “Kling-Made”

During the labor clashes and the horrific world war going on concurrently, Kling Bros. had still managed to expand not only its sales territory, but its range of products. They promoted themselves as the “headquarters for military clothing” during World War I (although it’s unclear if they actually had government contracts to clothe the enlisted men overseas), and made a wide range of uniforms with a “roomy, comfortable fit.” Meanwhile, for the everyday working man, the Kling “Air-In Raincoat” and “Ruf’-n-Ready Overcoat” handled the rough weather, while the “Airy-Lite” line of suits kept things breezy in the summer.

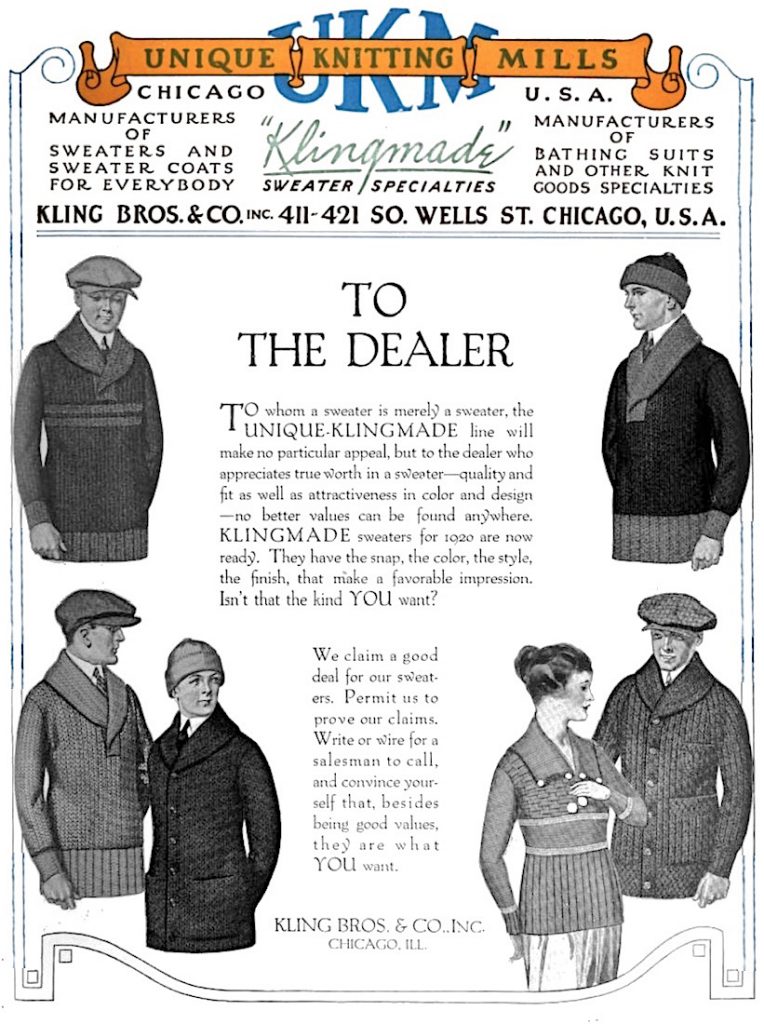

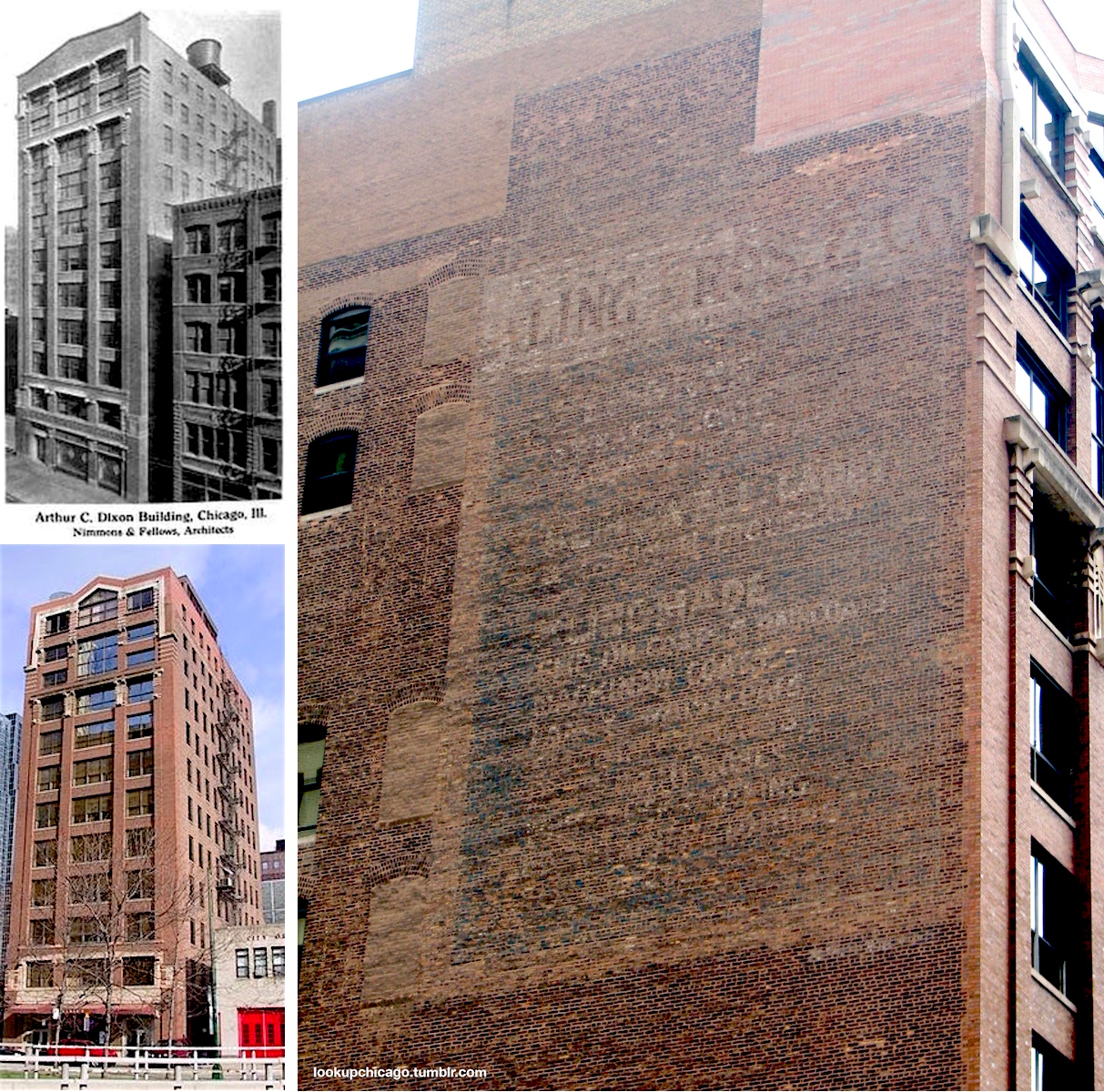

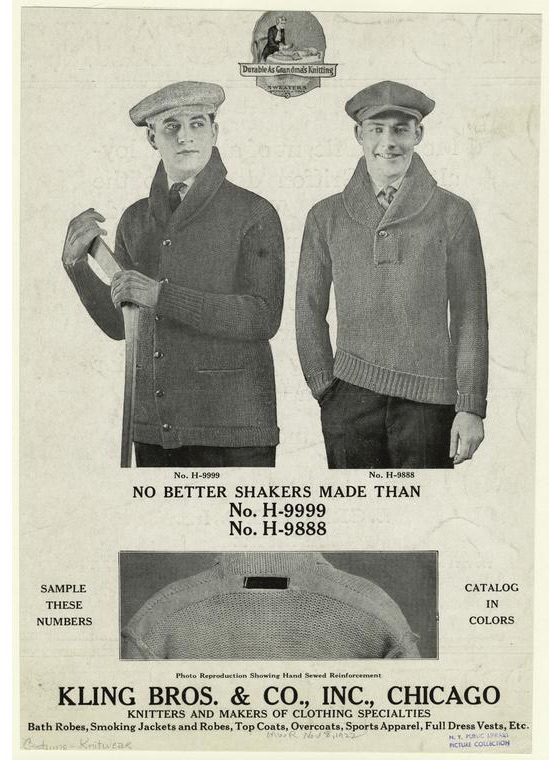

Probably the biggest development, though, was the 1916 acquisition of the Unique Knitting Mills—an upstart maker of sweaters, cardigans, jerseys, and bathing suits. Knits were red hot with civilian gents at the time, and in 1918, the Klings made UKM a center-piece of their new headquarters inside the Dixon Building at 411 S. Wells Street, with 50 workers rolling out what was now dubbed “Klingmade Sweater Specialties.”

Probably the biggest development, though, was the 1916 acquisition of the Unique Knitting Mills—an upstart maker of sweaters, cardigans, jerseys, and bathing suits. Knits were red hot with civilian gents at the time, and in 1918, the Klings made UKM a center-piece of their new headquarters inside the Dixon Building at 411 S. Wells Street, with 50 workers rolling out what was now dubbed “Klingmade Sweater Specialties.”

“Klingmade Sweaters—our own production—the brand your customers know—are a safe investment, for they always sell at a profit,” read a Kling Bros. ad in a 1919 issue of The Haberdasher. “They appeal not on a price tag basis alone, but also with their clever designs, brilliant color combinations and sturdy, dependable quality.”

Beyond just targeting dealers in trade publications, Kling marketed to the general public more during these years than any other point in its history, and it left an impression—literally. A giant painted Kling Bros. advertisement on the side of the company’s Wells Street building is still visible as a faded ghost sign 100 years later.

[The former Kling Bros. building at 411 S. Wells St., complete with surviving ghost sign]

[The former Kling Bros. building at 411 S. Wells St., complete with surviving ghost sign]

In the grand scheme, though, the Wells Street plant was just a brief stopping point. In 1919, the Klings has already put a plan in motion to have a new, expansive three-story factory erected in Wicker Park at 2226 W. Wabansia Street, with famed architect Alfred S. Alschuler leading the project.

The $600,000 structure (about $8 million with inflation) was a marvel; consolidating most of Kling’s extraneous manufacturing entities (now roughly 600-700 workers) under one roof, and becoming one of the largest clothing factories in Chicago, complete with an employee restaurant and a fancy clock tower. The intricate terra cotta entrances included the Kling Brothers name and the Star of David above it. The majority of these features were retained and are still visible in the building today, which was dramatically converted into upscale apartments in the 1990s and is now known as the “Clock Tower Lofts.”

IV. Considerable Adjustments

The Kling brothers were still just in their early 40s when the Wabansia plant opened, and their company seemed to be merely at the beginning of its ascendance. Within the first year at the new mega-factory, though, red flags were already popping up.

In November of 1920, the entire 500-person workforce of the Unique Knitting Mills was laid off, and the plant was temporarily closed due to a “slack season,” according to news reports. Operations renewed in 1921, but it doesn’t seem as though the Klings’ vision for the Wabansia plant ever quite came to total fruition.

In 1925, the superintendent of the factory, Theodore Morrie, was attacked outside his home in Evanston, beaten by two men dressed in golfing togs. The Tribune reported that police believed it to be “a renewal of the recent workers’ war,” suggesting that company-worker relations hadn’t exactly entered a rosy period in the ‘20s.

Adjusting to the realities of a fully unionized workforce—combined with the increasing popularity of more affordable, off-the-rack clothes at department stores—seemed to push the Klings, and many of their fellow wholesale tailors, into a corner. The onset of the Great Depression—spoiler alert—didn’t improve the situation.

Businesses that didn’t go under completely in the 1930s often worked out buyouts and mergers instead, hoping to pool remaining resources. Leopold Kling rented out large portions of the Wabansia plant to other businesses, and acquired the cheaper manufacturing services of Davenport, Iowa’s William Bradford Company as his new primary producer of men’s clothes. Kling Bros. also took a controlling interest in the Louis A. Walton Company and former rivals Lamm & Co., Leeds Tailors Inc., and Ed V. Price & Co. In 1937, the Kling corporate offices moved from Wabansia to the Price Building [pictured] at 319 West Van Buren Street.

Businesses that didn’t go under completely in the 1930s often worked out buyouts and mergers instead, hoping to pool remaining resources. Leopold Kling rented out large portions of the Wabansia plant to other businesses, and acquired the cheaper manufacturing services of Davenport, Iowa’s William Bradford Company as his new primary producer of men’s clothes. Kling Bros. also took a controlling interest in the Louis A. Walton Company and former rivals Lamm & Co., Leeds Tailors Inc., and Ed V. Price & Co. In 1937, the Kling corporate offices moved from Wabansia to the Price Building [pictured] at 319 West Van Buren Street.

In some ways it all amounted to subtraction by addition. Without the advantages of criminally cheap labor, it was harder to keep up production or to afford premium materials. As such, compromises were made on the marketing end—not just in terms of money, but ultimately, principles.

V. Lied in the Wool

No one could accuse Leopold Kling of not being an upstanding member of his community. His wise investments and substantial riches were often funneled into local charities, particularly through his longtime involvement with Chicago’s Mt. Sinai Hospital, where he served on the board for nearly 40 years, including in the role of president and chairman (a residents’ hall was named after Leopold and his wife Nannette in 1958, but was recently demolished). Maybe it was this commitment to doing good, in the long run, that made it easier to cut corners in some other respects.

No one could accuse Leopold Kling of not being an upstanding member of his community. His wise investments and substantial riches were often funneled into local charities, particularly through his longtime involvement with Chicago’s Mt. Sinai Hospital, where he served on the board for nearly 40 years, including in the role of president and chairman (a residents’ hall was named after Leopold and his wife Nannette in 1958, but was recently demolished). Maybe it was this commitment to doing good, in the long run, that made it easier to cut corners in some other respects.

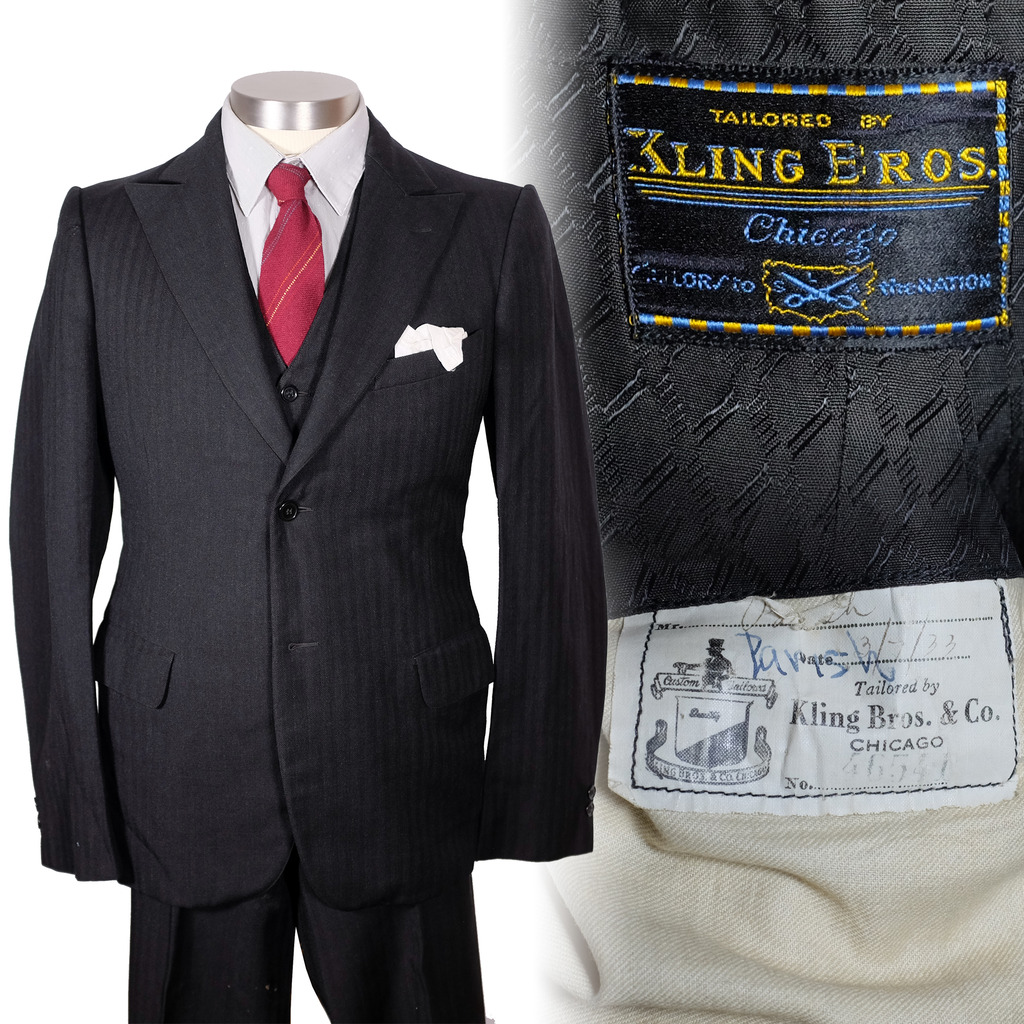

In 1942, when you’d think the government would have had more pressing issues to concern itself with, the Federal Trade Commission brought a case against Kling Bros. & Co. for rampant false advertising, accusing Leopold and Samuel of knowingly misleading the public in their labeling and marketing of Kling clothes.

[Kling Brothers suit and labels, “Tailors to the Nation,” 1933. Courtesy of TheFedoraLounge.com]

[Kling Brothers suit and labels, “Tailors to the Nation,” 1933. Courtesy of TheFedoraLounge.com]

The evidence was damning.

“Among and typical of such false and misleading descriptions and designations used on labels attached to samples of respondents’ materials,” the FTC report noted, “are the following:

“Blue-Green Alpaca—Mohair Knit Back” for material which contains none of the hair of the alpaca.

“Blue-Green Alpaca—Mohair Knit Back” for material which contains none of the hair of the alpaca.

“Camel Hair and Wool Blend.” “Silver Gray Mohair—Camel Wool Blend” for materials which contain none of the hair of the camel.

“Mohair and Wool Knit Back Overcoating—Green” for materials which have a knit back made of cotton.

“Oxford Mohair—Wool Blend Topper” for materials which contain no mohair.

“Green Shadow Stripe . . . pure worsted-silk decoration” for materials in which the decoration is rayon or some fiber other than silk, the product of the cocoon of the silkworm.

“Imported Corona Brown Wool Crisp Spun Homespun” for fabrics that are not imported, but to the contrary are manufactured in the United States.

The FTC’s final cease-and-desist ruling was probably embarrassing for the aging Kling brothers, but hardly headline news, either. They carried on, albeit in an increasingly niche market.

In 1946, after the war and just before Kling Bros. & Co’s 50th anniversary, the entirety of the Wabansia plant was finally sold off to a different sibling set, Smoler Brothers Inc. (makers of dresses and sport suits), who’d already occupied half the building for 13 years. In the 1950s, Kling Bros. & Co. moved its own headquarters for the final time, shifting from Van Buren to 1060 West Adams Street. That building, as well, was eventually converted into modern lofts.

In 1946, after the war and just before Kling Bros. & Co’s 50th anniversary, the entirety of the Wabansia plant was finally sold off to a different sibling set, Smoler Brothers Inc. (makers of dresses and sport suits), who’d already occupied half the building for 13 years. In the 1950s, Kling Bros. & Co. moved its own headquarters for the final time, shifting from Van Buren to 1060 West Adams Street. That building, as well, was eventually converted into modern lofts.

Interestingly, it looks like Samuel Kling may have taken over ownership of the old family business in its final years, while Leopold focused on a more profitable acquisition, the Maier-Lavaty Company—Chicago’s largest manufacturer of custom uniforms. By the 1960s, though, both brothers were probably involved in their businesses more as figurehead financiers than active leaders.

Leopold Kling died in 1962 at age 84, and Samuel followed in 1967 at 91. The Clock Tower Lofts on Wabansia Avenue really stand as the best monument to their success, and to a memorable sea change in Chicago’s now largely extinct garment industry. The old tailor’s measuring tape in our museum collection, featuring the Kling Bros. name and the Wabansia address, is a more humble artifact of that same era—when the American dream still came with a custom fit.

SOURCES

The Clothing Workers of Chicago: 1910-1922, Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, 1922

“Kling Bros. to Go After More Southern Trade” – Men’s Wear, Vol. 21, No. 8, August 1906

“Kling Brothers – Clock Tower Lofts” – ConnectingtheWindyCity.com, Aug 29, 2011

“Exemption from NRA Sought by Davenport Firm” – The Dispatch (Moline, IL), Oct 20, 1934

Federal Trade Commission Decisions: “In the Matter of Louis A. Walton Co., Kling Bros. & Co., Leopold Kling and Samuel Kling,” Aug 14, 1942

“Encyclopedia Judaica: Tailoring” – JewishVirtualLibrary.org

“The Strike That Shook Up an Entire Industry” – Chicago Tribune, June 12, 1988

“Pair in Golfing Togs Use Club on Evanstonian” – Chicago Tribune, Sept 3, 1925

Report of the Factory Inspector of Illinois: 1902 and 1907

“Kling Brothers Will Move Offices to Price Building” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 14, 1937

“Clothing Firm Buys Factory on West Side” – Chicago Tribune, Oct 6, 1946

Making a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919-1939, by Lizabeth Cohen, 1990

“Forgotten Merchants: Kling Bros. & Co.” – ChicagoNow.com, July 9, 2013

“Big Plant for New District: Kling Brothers Soon Will Join Colony of Wholesalers” – Chicago Tribune, March 28, 1908

“Business Man Honored for Service to Hospital” – Chicago Tribune, March 29, 1959

“Leopold Kling Services Set for Tomorrow” – Chicago Tribune, March 22, 1962

“Thousands of Garment Workers Plan Monster Strike, Officials Coming” – The Day Book (Chicago), Aug 28, 1915

Archived Reader Comments:

“My Grandfathers business was started from money given to him by the brothers in the late 50’s on the simple promise of repayment and which later I found out was interest free no strings attached. The banks told him to get F’d… point is they were good hard working people that gave and gave and most of it wasn’t published or talked about. Business owners today in this and many lines similar to make their garbage throw away quality products in China employing 7 year olds 15 hours a day making Jack squat while they sip their martinis in Lake Forest preaching about equality and ethics, so much has changed including these magnificent buildings that were once factories, replaced with thoughtless poorly built overpriced crap designed by “architect’s” popping ritalin and Starbucks tweeting about they’re uber rides being late. The world’s gone down the big pooper in many ways, this article reminds me of the better times.  ” —Samuel C., 2019

” —Samuel C., 2019