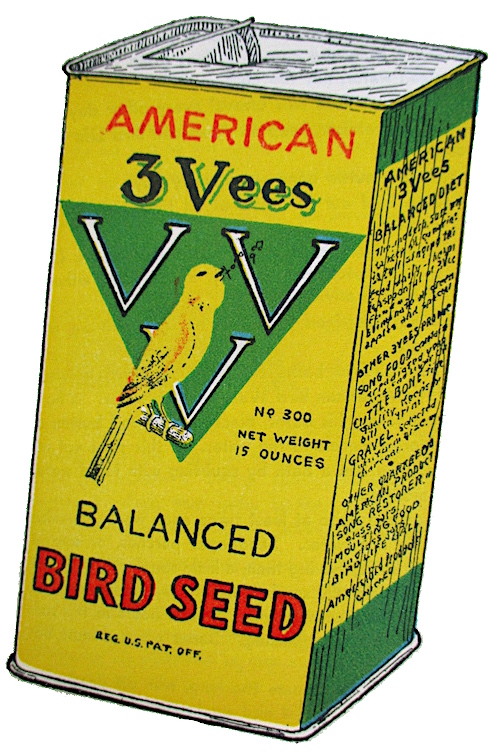

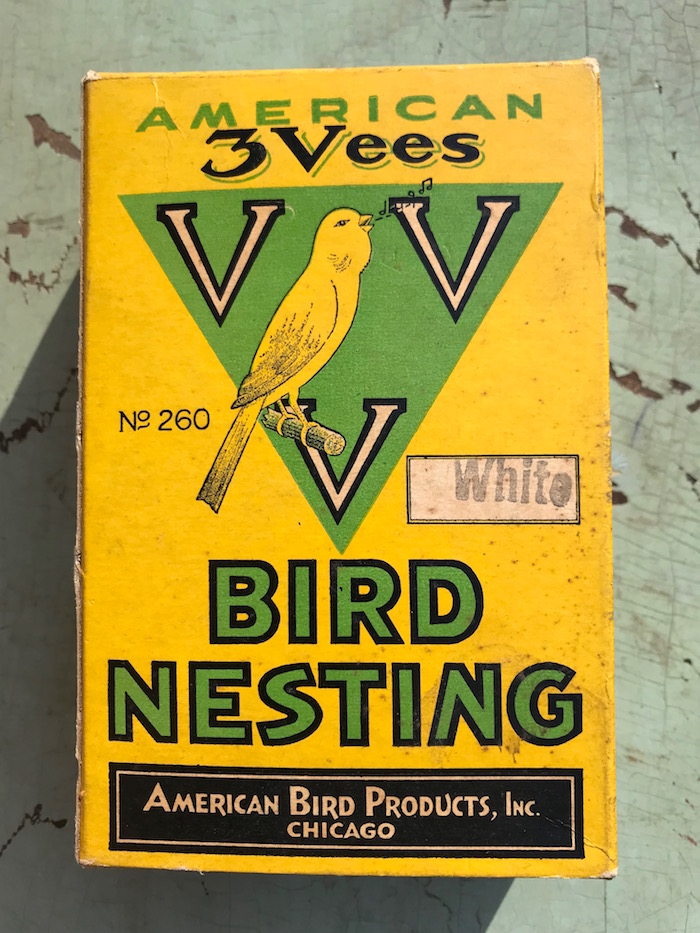

Museum Artifact: American 3 Vees Bird Nesting, c. 1940s

Made by: American Bird Products, Inc., 2610 W. 25th Place, Chicago, IL [Little Village]

Starting with the pet canary craze of the ‘20s and ‘30s up through the post-war budgie boom, Chicago’s American Bird Products, Inc. (aka the American Bird Food MFG Co. and American Bird Corp.) established a nice niche for itself—evolving from a mere seed supplier into something more like a lifestyle brand for the feathered set.

Starting with the pet canary craze of the ‘20s and ‘30s up through the post-war budgie boom, Chicago’s American Bird Products, Inc. (aka the American Bird Food MFG Co. and American Bird Corp.) established a nice niche for itself—evolving from a mere seed supplier into something more like a lifestyle brand for the feathered set.

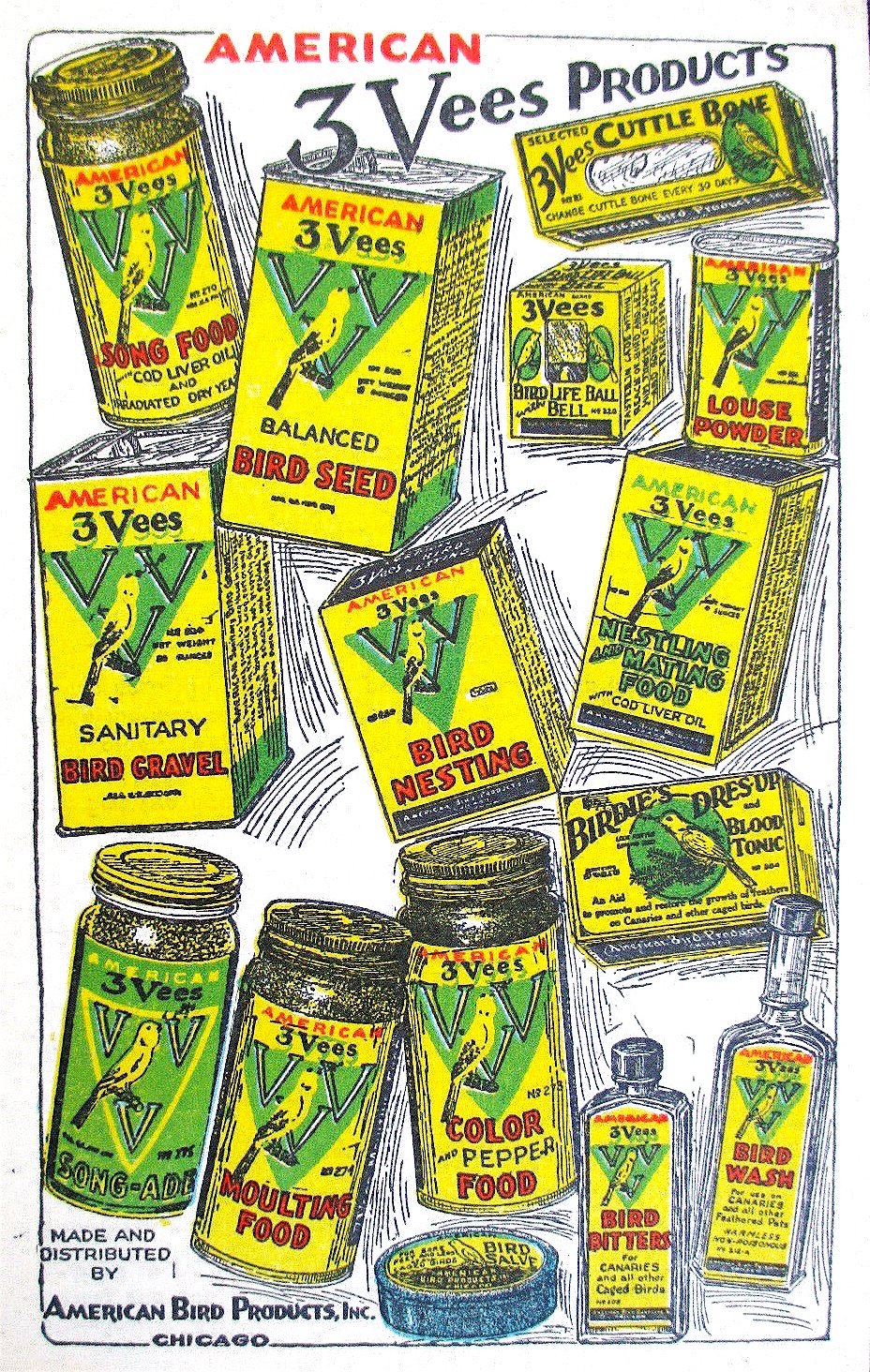

The company produced a ridiculous variety of avian accoutrement under its familiar 3 Vees trademark, including specialized bird foods for moulting, mating, and singing, as well as cuttle bones, sanitary gravel, “Bird Wash,” “Bird Bitters,” “Louse Powder,” and something called “Birdie’s Dres-Up & Blood Tonic.”

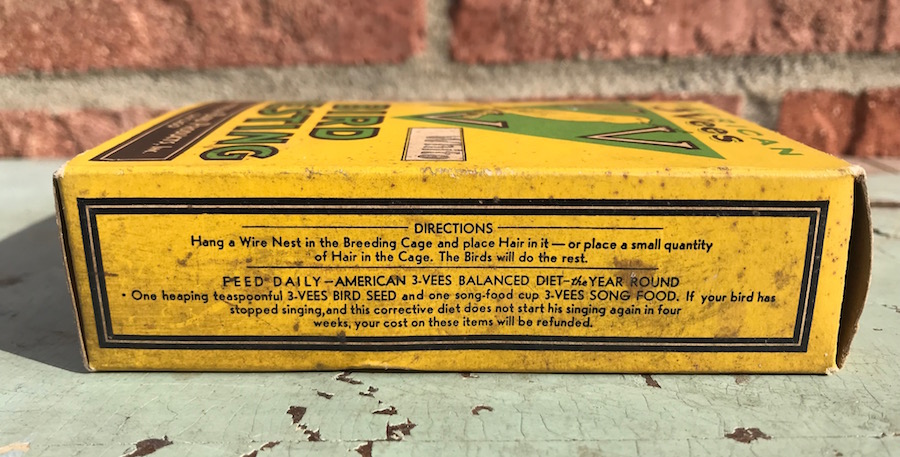

The “Bird Nesting” material in our museum collection, meanwhile—despite looking like something snaked out of the shower drain of the 45th president—could serve a pretty important purpose for pet owners trying to break into the bird breeding game. The box of fluff came with some simple instructions for use: “Hang a Wire Nest in the Breeding Cage and place Hair in it—or place a small quantity of Hair in the Cage. The Birds will do the rest.” They know what’s up.

[The vintage “Bird Nesting” in our collection is described on the box as “hair,” but from what source, we may never know.]

[The vintage “Bird Nesting” in our collection is described on the box as “hair,” but from what source, we may never know.]

The “3 Vees” in the brand name, if you’re wondering, stood for “Vitality, Vigor, and Vitamin.” In retrospect, those first two V’s are basically synonyms, so “2 Vees” probably would have sufficed. But hey, I’m not here to quibble with American Bird Products’ marketing decisions. On the contrary, the company clearly knew what it was doing, expertly peddling a growing line of goods to great success in the midst of a brutal economic era. The strategy seemed to be a clever combination of old-school promotional tricks like the traveling medicine show (featuring “noted bird counselors” showing off their trained canaries at department stores) and new-school mediums like radio advertising, highlighted by one of the longest running single-sponsor programs in WGN’s history—the weekly 15 minutes of Zen known as “American Radio Warblers.”

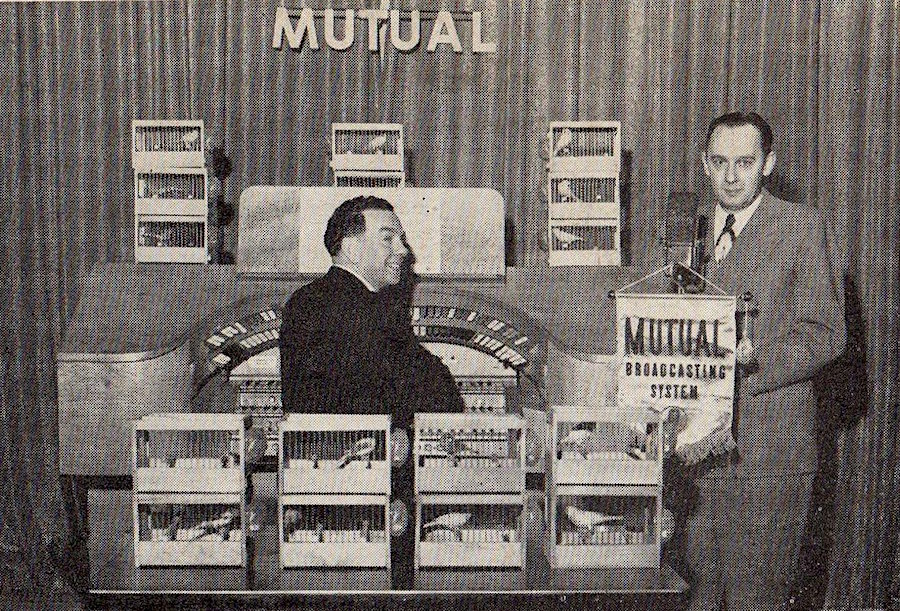

Maybe you’re thinking to yourself, “Wait, is American Radio Warblers really what I am imagining it was?” . . . Well, if you’re picturing a bunch of actual caged canary birds situated around microphones, singing along to slow waltzes in a sweet, cacophonous drone with accompaniment from a creepy Wurlitzer organ, then the answer, thankfully, is YES!

[With the possible exception of WGN’s deeply buried archives, the only place to hear the glory of the American Radio Warblers these days is through the commercial recordings American Bird Products financed in the ’40s and ’50s, which can still occasionally be found in dusty vinyl bins at resale shops. The track above is “Skater’s Waltz,” ft. Preston Sellers on the organ. Produced by Arthur C. Barnett.]

The Fascinating Story of the American Radio Warblers

An excerpt from an American Bird Products sales pamphlet, circa 1940

“In 1929, the makers of the American 3 Vees Products became very enthusiastic about the remarkable singing qualities of a group of ordinary young canaries that were used for a feeding experiment. They were fed a balanced diet, consisting of two products—American 3 Vees Bird Seed and American 3 Vees Song Food.”

“The next step was to inform the canary loving public about this remarkable discovery, and it was decided to use the radio. Several program suggestions were made which included the use of bird calls and mechanical imitations.

“The next step was to inform the canary loving public about this remarkable discovery, and it was decided to use the radio. Several program suggestions were made which included the use of bird calls and mechanical imitations.

“Then the question was asked: ‘If a human being can sing over the radio, why not a canary? Why not allow the canaries to do their own singing?’ A try-out proved that it was possible and practical and so—

“The American Radio Warblers, that peppy little group of birds, fed the American 3 Vees Balanced Diet, originated live canary singing over the air, with an organ accompaniment. That was back in 1929 [some newspaper reports actually date it back to 1927], and today some of the original birds still sing with this popular group.

“These hardy little birds have sung to millions of people over leading stations and today have many imitators***. They have also made personal appearances in larger stores throughout the country where they draw crowds of interested people. They have traveled thousands of miles in all kinds of weather and under conditions that would try the patience and strength of humans.

“The American Radio Warblers broadcast from October to June each year and many bird owners consider them the finest singing teachers. They tune in each Sunday, so their own birds can listen and learn new runs and trills.”

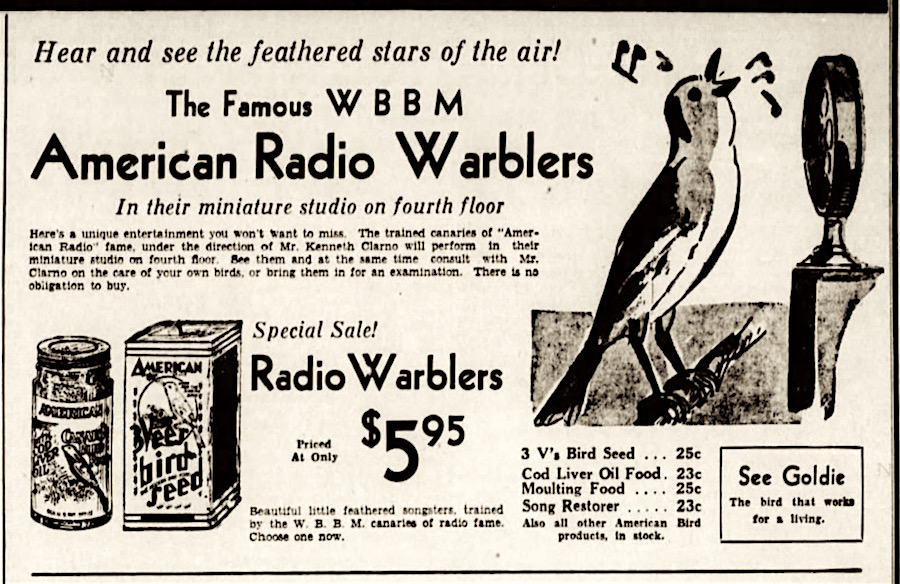

[1934 newspaper ad for American Bird Products ft. the American Radio Warblers, who were then broadcast on Chicago station WBBM. They would eventually move to WGN]

[1934 newspaper ad for American Bird Products ft. the American Radio Warblers, who were then broadcast on Chicago station WBBM. They would eventually move to WGN]

***Yes, you read that one part right: the American Radio Warblers weren’t just an isolated novelty—they had “many imitators.” As the show advanced in the 1930s from its early origins on WBBM to its long run on WGN and the national Mutual Broadcasting System, it inspired similar programs from pet food competitors, including the “Master Radio Canaries” of Hartz Mountain and the “Canary Chorus” of Chicago’s longest standing bird food manufacturer, Kaempfer’s, Inc. It was all part of America’s very real and genuine obsession with the little yellow songsters, a trend jump-started by Hartz founder Max Stern’s bulk imports of the birds from Germany, starting in the mid 1920s.

Each company used its respective radio show as a multi-faceted tool for selling their wider brand of products. Arthur C. Barnett, the advertising man who supposedly hatched the Radio Warblers idea for American Bird Products, really comes off looking like a genius when you break down all the ways 15 minutes of trilling birds could make bank in the USA.

1. The Talent’s Cheap

According to the March 1944 issue of Variety, out of nearly $5 million spent annually on talent by the four main radio networks in Chicago, “the lowest network show in talent costs is the American Radio Warblers show over on Mutual.” Sure, the in-house WGN organist (sometimes Helen Westbrook, sometimes Preston Sellers) had a few dimes thrown their way. But among the birds, even a legendary soloist like Goldie (“the bird that works for a living”) made exactly the same salary as mere fledgling crooners like Ranny, Ronnie and Rudy—the newcomers to the chorus back in ’41. And when I say they made the same money, it is to say they were paid no money. Clearly. Because they were birds.

[WGN organist Preston Sellers and the “Original Feathered Stars of the Air” doing their nationally broadcast American Radio Warblers show, c. 1947]

[WGN organist Preston Sellers and the “Original Feathered Stars of the Air” doing their nationally broadcast American Radio Warblers show, c. 1947]

2. A “Captive” Audience

From the beginning, Arthur Barnett seemed to recognize that the radio show could be used not merely as a generic promotion of canaries and canary food, but as an interactive teaching tool for people who already owned birds. Did pet canaries really listen to the Radio Warblers and “learn” the art form of melodic yodeling in the process? Maybe. But the key was to sell the idea that they could.

Barnett even produced several 78 and 45 RPM records of some of the Warblers’ best jams, selling them as instructional tools. “The birds you hear on this record are known as the ‘Singing Teachers to the Canaries of America,’” he claimed on the cover of one of those records. “All canaries like to hear their little brothers and will sing right along with them. Teaches young birds how to sing better, brings birds back to full song after moulting.”

Barnett even produced several 78 and 45 RPM records of some of the Warblers’ best jams, selling them as instructional tools. “The birds you hear on this record are known as the ‘Singing Teachers to the Canaries of America,’” he claimed on the cover of one of those records. “All canaries like to hear their little brothers and will sing right along with them. Teaches young birds how to sing better, brings birds back to full song after moulting.”

Of course, on the same album sleeve, Barnett also assured the human audience that this was “sweet relaxing music. . . . For bird lovers of all ages, from children to grandparents, shut-ins and others who spend lonely hours at home.” He certainly seemed to know his demographic.

Advertisements in local newspapers (paid for either by American Bird or WGN) pushed the same idea of school time for Tweety Bird. “Free Singing Lessons Await Your Canary on W-G-N Program,” read one blurb in the Tribune in 1937. “If you own a canary, free singing lessons await it through the medium of W-G-N at 10:45 a.m. today and every Sunday thereafter. Your bird may listen at that hour to the singing of the American Radio Warblers. These famous feathered stars of the air have been broadcasting for the last seven years and are excellent teachers. Place your bird within easy hearing distance of the radio. First it will listen with interest, then join right in. Your bird may learn some new bird trills and melodies.”

3. Commercial “Concerts”

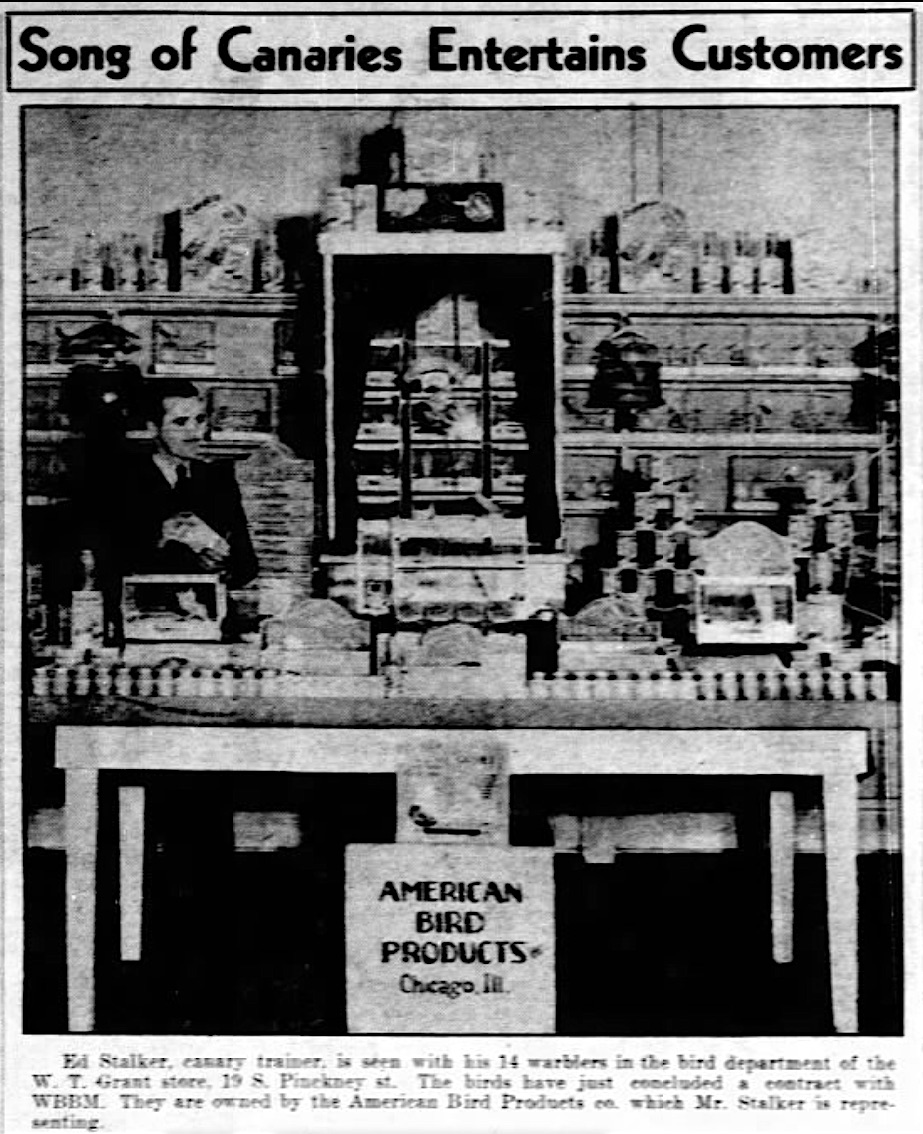

Once they earned fame on the airwaves, the American Radio Warblers (or maybe some totally different canaries, as if anyone would know) would hit the road ostensibly to perform for their “fans.” These department store appearances—heavily promoted in newspapers—were really just elaborate sales pitches for American Bird Products, of course.

Once they earned fame on the airwaves, the American Radio Warblers (or maybe some totally different canaries, as if anyone would know) would hit the road ostensibly to perform for their “fans.” These department store appearances—heavily promoted in newspapers—were really just elaborate sales pitches for American Bird Products, of course.

The presentation would include one of ABP’s resident experts or “bird counselors,” who would answer questions from the audience and sing the praises of various 3 Vees products. There were plenty of actual canaries for sale at each event, too—usually available at two price points. In 1937, for example, if you wanted to buy one of the birds who trained at the very talons of the American Radio Warblers themselves, he might cost you about 6 bucks. If you were content with the raw, untapped talent of a mere “chopper” canary, it’d run you closer to $4. In either case, you would be assured that only using 3 Vees products would guarantee a consistent warble over time.

The radio shows and their related events were still going on into the 1950s, but by that point, both American Bird Products and Kaempfer Inc. had become subsidiaries of the Hartz pet food conglomerate out of New York, essentially bringing the canary radio wars to an end. Overall canary sales in America were dipping a bit, as well, as the whole practice began to take on a less appealing, old-fashioned sort of vibe, best represented by Tweety Bird’s clueless owner “Granny” in the Looney Toons cartoons of the era.

During the height of the canary craze, though, the birds that were bred in America—by some observations—took on a sound and singing style quite unique from those kept in Germany (where the bird market had imploded during the war), the UK, Japan, or other nations. Maybe the radio shows really had left their mark, or maybe canaries just absorbed the other musical influences around them, like big band jazz. We’d have to ask Goldie himself.

[Elaborate American Bird Products display in the pet section of Grant’s Department Store in Portland, Maine, 1930s. from Maine Historical Society]

[Elaborate American Bird Products display in the pet section of Grant’s Department Store in Portland, Maine, 1930s. from Maine Historical Society]

Inside the Business

The American Radio Warblers program was so essential to and synonymous with American Bird Products, Inc., that the company’s entire history seems to begin and end with the run of the show. Any other widely available information relating to the founding of the business or its day-to-day operations is few and far between. [photo below: ABP bird counselor Ed Staulker leads a 3 Vees presentation in 1933]

I couldn’t find a specific record of when the company was first incorporated, but 1926 or 1927 seems a likely guess. From there, we just get a few hints at the key players involved. One of them is Horace R. Wagner (1905-1987), who is listed as a salesman in “bird supplies” in the 1930 census, and is subsequently name-checked in a 1935 Tribune article as the “manager of the American Bird Products company” (he only made the news that day because he’d been robbed at gunpoint). Wagner was still listed as the company’s secretary throughout World War II, but seemed to exit the business a short time after (likely when Hartz bought out the company). He went on to a long career in real estate in Wonder Lake, Illinois, and when he died in 1987 at the age of 81, no mention was made in his obituary of his days with American Bird Products.

I couldn’t find a specific record of when the company was first incorporated, but 1926 or 1927 seems a likely guess. From there, we just get a few hints at the key players involved. One of them is Horace R. Wagner (1905-1987), who is listed as a salesman in “bird supplies” in the 1930 census, and is subsequently name-checked in a 1935 Tribune article as the “manager of the American Bird Products company” (he only made the news that day because he’d been robbed at gunpoint). Wagner was still listed as the company’s secretary throughout World War II, but seemed to exit the business a short time after (likely when Hartz bought out the company). He went on to a long career in real estate in Wonder Lake, Illinois, and when he died in 1987 at the age of 81, no mention was made in his obituary of his days with American Bird Products.

The earliest mention of a company president at American Bird was a Russian-Jewish immigrant and World War I veteran named Morris Handel (1896-1988), who held the position from at least the mid 1930s through the Second World War, according to the List of Domestic and Foreign Corporations of Illinois. With Handel at the helm, American Bird established a corporate office at 1410 W. Harrison Street and its first full-scale manufacturing plant, located at 2610 W. 25th Place in Marshall Square. This three-story factory remained in operation from the 1930s into the ‘50s, and served as a production plant, distribution warehouse, AND—quite likely—a breeding base for the company’s canary stock. It is now the South Campus of St. Augustine College (the same school that owns the former Essanay Studios building in Uptown).

[This building at 2610 W. 25th Pl. was home to American Bird Products, Inc. from the 1930s through the mid 1950s]

[This building at 2610 W. 25th Pl. was home to American Bird Products, Inc. from the 1930s through the mid 1950s]

It’s hard to say how much personal enthusiasm either Horace Wagner or Morris Handel (Horace & Morris!) had for birds, caged or otherwise [no mention of American Bird Products appeared in Handel’s obit either]. But they seemed to try their best to honor the trade by hiring a lot of bird experts to help design and sell their products and raise the company’s signature canaries.

Every exhibition that ABP Inc. hosted included appearances by these special consultants—names like Kenneth Clarno, Ed Staulker, and Fred Weber. The aforementioned advertising man Arthur Barnett was either already a bird lover or became one by working for the company, as he went on to produce a series of additional animal training records, including one for teaching your parakeet how to talk (it was called, coincidentally, “How to Teach Your Parakeet to Talk”). Another longtime expert and author on the bird care circuit, Wilton R. North, eventually became the executive vice president of the company.

Sometime around 1950 or so, the ownership group of Hartz Mountain officially took over the operations of American Bird Products, Inc., along with its sister companies the American Bird Food MFG Corp. and the American Bird Corporation—all of them existing under the banner of another Hartz property, American Shell Products, Inc. Max Stern served remotely as the company president in New York, with his brother Gustav as secretary and a Chicago lawyer named Morris A. Haft as the registered agent. The company offices moved to Haft’s personal office at 134 N. LaSalle Street.

Sometime around 1950 or so, the ownership group of Hartz Mountain officially took over the operations of American Bird Products, Inc., along with its sister companies the American Bird Food MFG Corp. and the American Bird Corporation—all of them existing under the banner of another Hartz property, American Shell Products, Inc. Max Stern served remotely as the company president in New York, with his brother Gustav as secretary and a Chicago lawyer named Morris A. Haft as the registered agent. The company offices moved to Haft’s personal office at 134 N. LaSalle Street.

On February 26, 1954, the Tribune ran a story about Chicago becoming a hub for animal feed manufacturing. The bird feed business and American Bird Products got a special callout.

“Milton R. North, executive vice president of American Bird Food Manufacturing company, believes Chicago in the last three years has become the center of the bird food industry,” reporter Russell Freeburg wrote. “Chicago companies in recent years have expanded to an annual multimillion dollar industry. Volume now amounts to about 10 million pounds of bird, fish, turtle, and hamster foods.

“The increase in Chicago’s bird food business resulted primarily from Chicago being the home of a parakeet craze four years ago, said North. Now canaries are beginning to outsell parakeets again.

“American Bird Food plans a 50,000 square foot addition to its plant and offices at 2610 W. 25th Pl. to meet new business. The company has been in Chicago 27 years. Hartz Mountain Products corporation has had a plant at 659 Hobbie Street for 20 years. . . . The same majority stockholders are associated in the management of Hartz Mountain and American Bird Foods. Hartz Mountain manufactures one food with several vitamins. American Bird puts separate vitamins in different foods. A subsidiary of American Bird sells canaries.

“American Bird Food plans a 50,000 square foot addition to its plant and offices at 2610 W. 25th Pl. to meet new business. The company has been in Chicago 27 years. Hartz Mountain Products corporation has had a plant at 659 Hobbie Street for 20 years. . . . The same majority stockholders are associated in the management of Hartz Mountain and American Bird Foods. Hartz Mountain manufactures one food with several vitamins. American Bird puts separate vitamins in different foods. A subsidiary of American Bird sells canaries.

“Ingredients used by Chicago companies come from all over the world. Among them are thistle seed from India and canary seed from South America and Morocco, North said.”

It seems as though American Bird may have given up on its factory expansion, and instead took over a new HQ in the mid 1950s at 6600 West Armitage Avenue in Galewood, which remained in use by the company up until the early 1970s. By then, classified ads were generally identifying the business as simply the “American MFG Co.”—suggesting they were either moving beyond bird and pets or moving closer to absolute vagueness. Either way, the 3 Vees had disappeared from pet shop shelves, as Hartz products took over a virtual monopoly on small pet goods for years to come.

And that just about does it. I managed to get through that entire article without a single social media canary pun about tweets or twittering. You’re all welcome.

[Shop owners at the Beacon Sport Center in Pompano Beach, FL, circa 1950. Well stocked in American 3 Vees products]

SOURCES:

“Chicago Role in Feeds Built in Grain Pits” – Chicago Tribune, February 26, 1954

American 3 Vees – Feeding, Breeding and Care of Canaries

Eco-Sonic Media, by Jacob Smith, 2015

“Horace Wagner” – Northwest Herald (Woodstock, IL), March 5, 1987

“Max Stern, Yeshiva U. benefactor and Hartz Corp. founder, is dead” – Chicago Tribune, May 21, 1982

“Hedge Fund Woes Dog Hartz Dynasty” – Daily Record (New Jersey), Feb 3, 2004

Talking Parakeets: Complete Manual on Their Care, Training and Breeding, by Milton R. North

“Radio Canaries” – Chicago Tribune, November 17, 1940

“NBC’s $2,308,800 Talent Outlay Tops Webs in Chi; All Nets Total $4,799,600” – Variety, March 1944

“The Mutual Broadcasting System” – Digital Deli Online

“500,000 Singing Canaries Due Here from Japan” – Dunkirk Evening Observer (Dunkirk, NY), May 8, 1950

“American Radio Warblers in 14th Year on Air” – Chicago Tribune, October 26, 1941

“Free Singing Lessons Await your Canary on WGN Program” – Chicago Tribune, Feb 21, 1937

“Song of Canaries Entertains Customers” – Wisconsin State Journal (Madison), May 4, 1933

“Pompano Beach – 1950’s Beacon Sport Center” – Estate Sale Treasure Hunter

“The Hartz Mountain Corporation” – Encyclopedia.com

“Radio’s Singing Canaries Craze of the 1920s-1950s” – Music Weird

American Radio Warblers – “Voice of Spring” music

Archived Reader Comments:

“I remember WAIT-AM used to run a commercial that was the “3 V’s Singing Canaries”. It was a light instrumental song played behind a brood of canaries chirping. Bizarre but memorable! ” —Steve, 2018

” —Steve, 2018