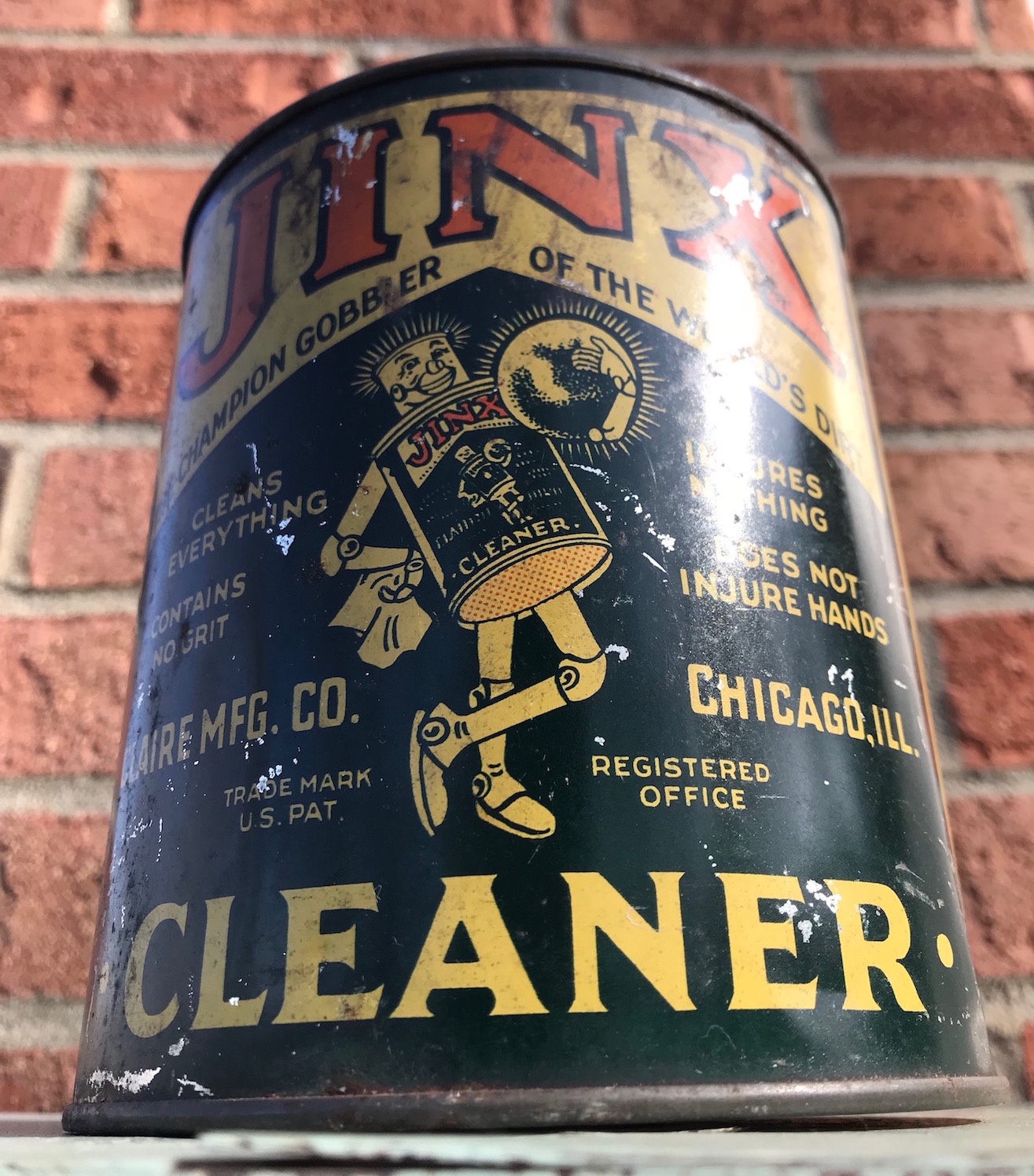

Museum Artifacts: Jinx Cleaner (c. 1920s) and Moth Crystal Vaporizer (c. 1960s)

Made By: Claire MFG Co., 6742 S. Yale Avenue, Chicago, IL [Englewood]

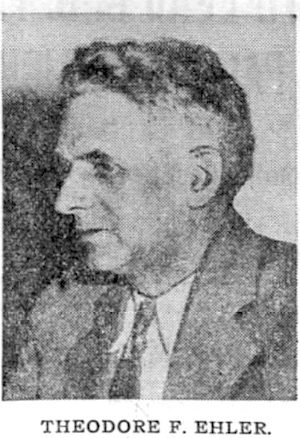

In 1927, Chicago municipal court judge Theodore F. Ehler—presiding during the height of mob warfare and corruption—made headlines for the unusual sentences he started imposing on a less romanticized element of the city’s criminal underbelly: deadbeat husbands.

Rather than sending these sad sacks off to jail, as was the general rule of thumb, Ehler ordered them into their own kitchens to take over the domestic responsibilities from their wives, who could then seek income on their own. “Sentence a loafing husband to kitchen police instead of jail,” he said, “and the Court of Domestic Relations won’t be needed.”

Rather than sending these sad sacks off to jail, as was the general rule of thumb, Ehler ordered them into their own kitchens to take over the domestic responsibilities from their wives, who could then seek income on their own. “Sentence a loafing husband to kitchen police instead of jail,” he said, “and the Court of Domestic Relations won’t be needed.”

One newspaper reporter praised this “interesting experiment in marital economics and psychology,” noting that: “In putting husband and wife in each other’s places, the Chicago judge is just making practical application of the theory that to understand everything is to forgive most of it.”

I suppose we could debate how progressive it actually was to equate house work with jail time, but in retrospect, Judge Ehler might have had his own personal motivations for sending men to the mop instead of the slammer. He was, after all, a longtime stockholder in the Claire Manufacturing Company, makers of the quasi-famous “JINX” house cleaner. And within a few more years, he’d be the company’s sole owner.

I. “One Cleaner for All Cleaning”

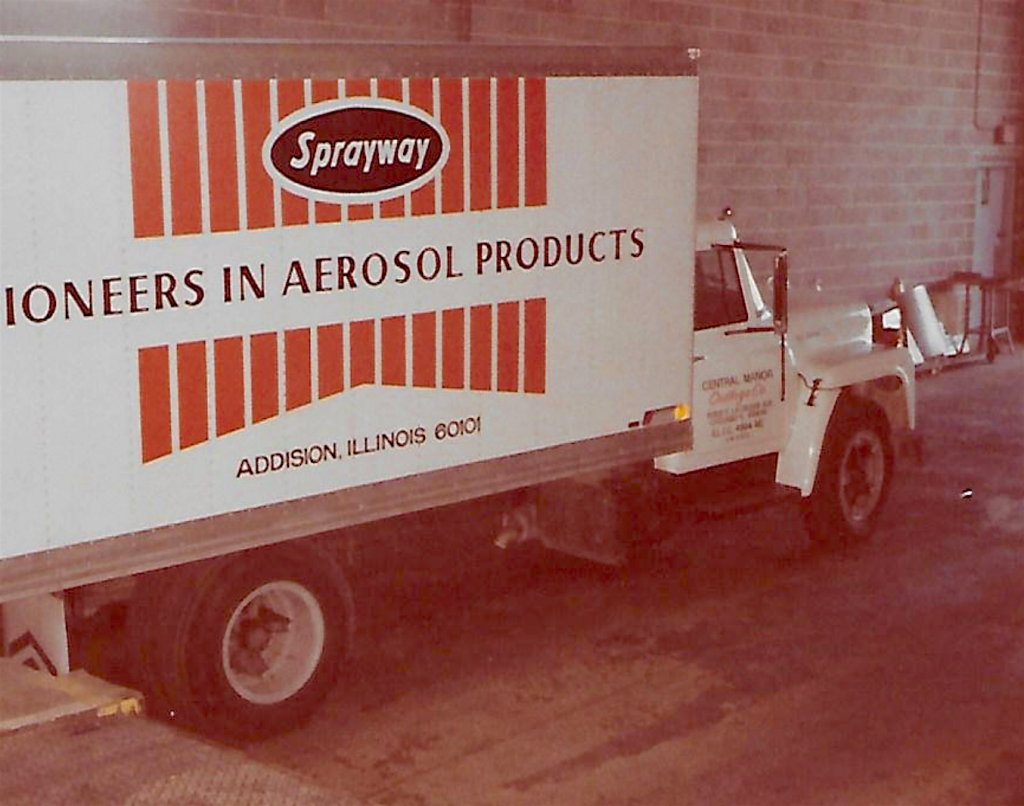

The Claire MFG Co. was founded in 1913 and is still in business today, with offices in suburban Downers Grove, IL. Best known since the 1950s as one of the pioneers of the aerosol spray can, the company has unsurprisingly had to endure some pretty hefty challenges to stay afloat—including adaptations to new environmental standards and several corporate buyouts. All things considered, though, Claire hasn’t deviated that much from its original focus. Cleaning products are still the crux of the business, and “Mr. Jinx”—the flagship brand that introduced the company to the world over 100 years ago—is still part of the fleet.

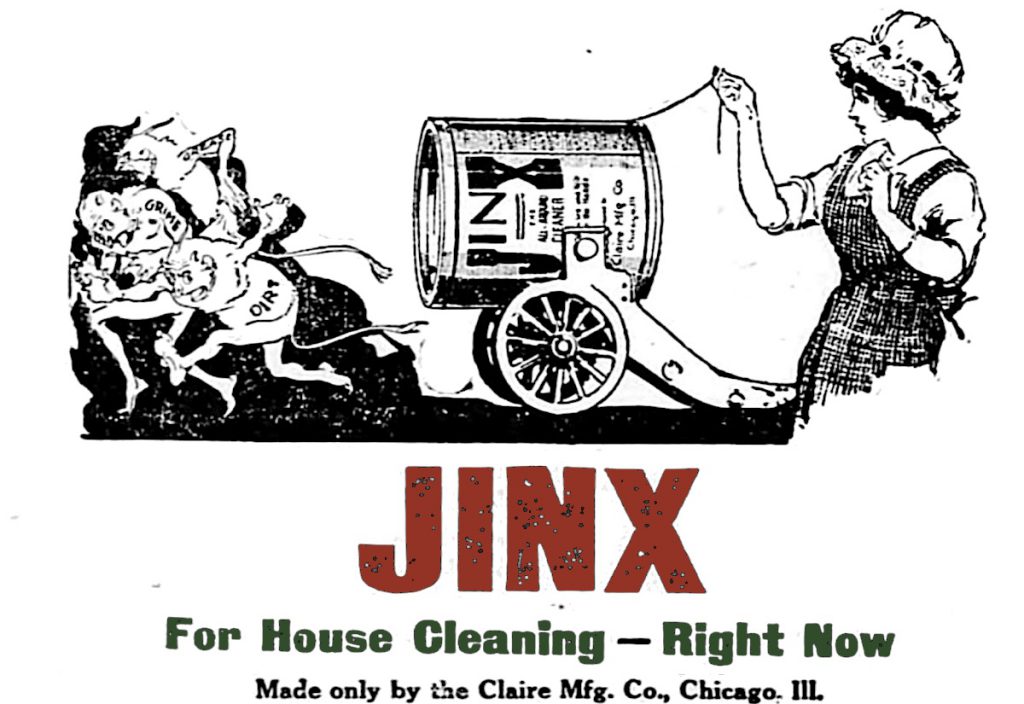

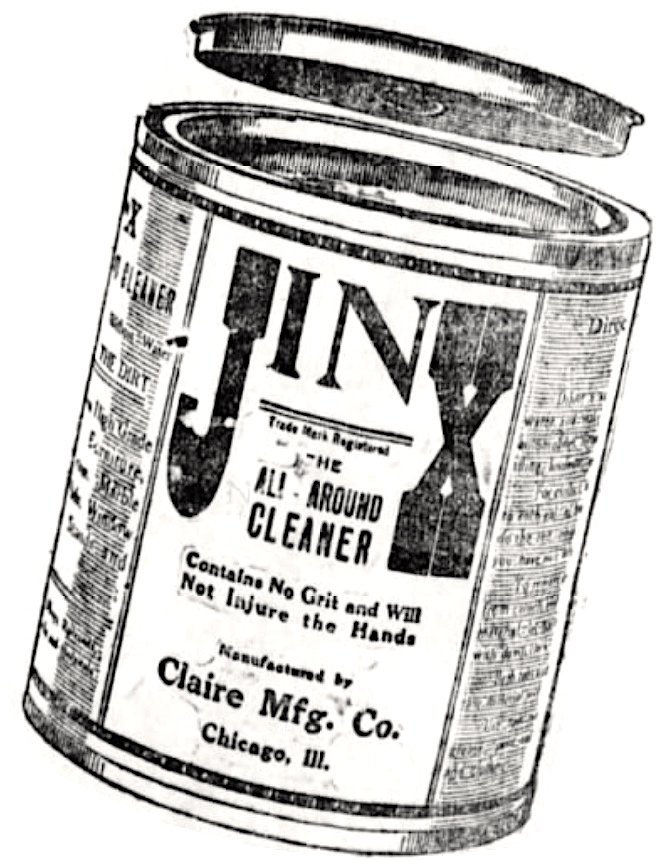

“Now—right now—is the time for you to put JINX to the test,” read one of the very first Claire advertisements in 1914. “JINX, the new cleaner of everything, the new ‘discovery’ that scours without grit, cleans without lye or caustic, makes house-cleaning a pleasure.”

“You’ll hardly believe your own eyes when you see the marvelous cleaning power of this eighth wonder of the world, JINX,” another ad exclaimed. “You never would have dreamed that such a magic destroyer of dirt, grease, smudge and grime could ever exist even in this twentieth century.”

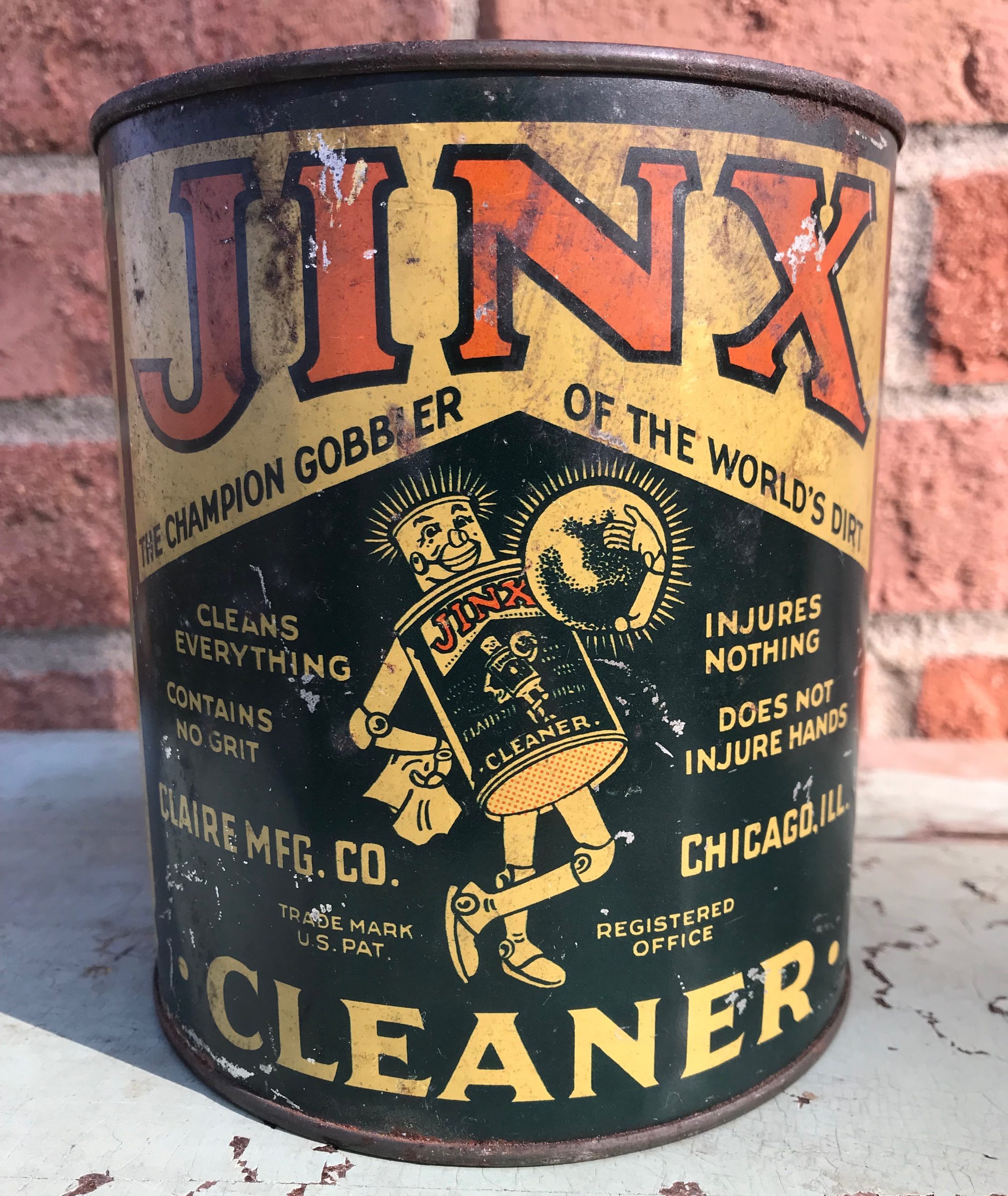

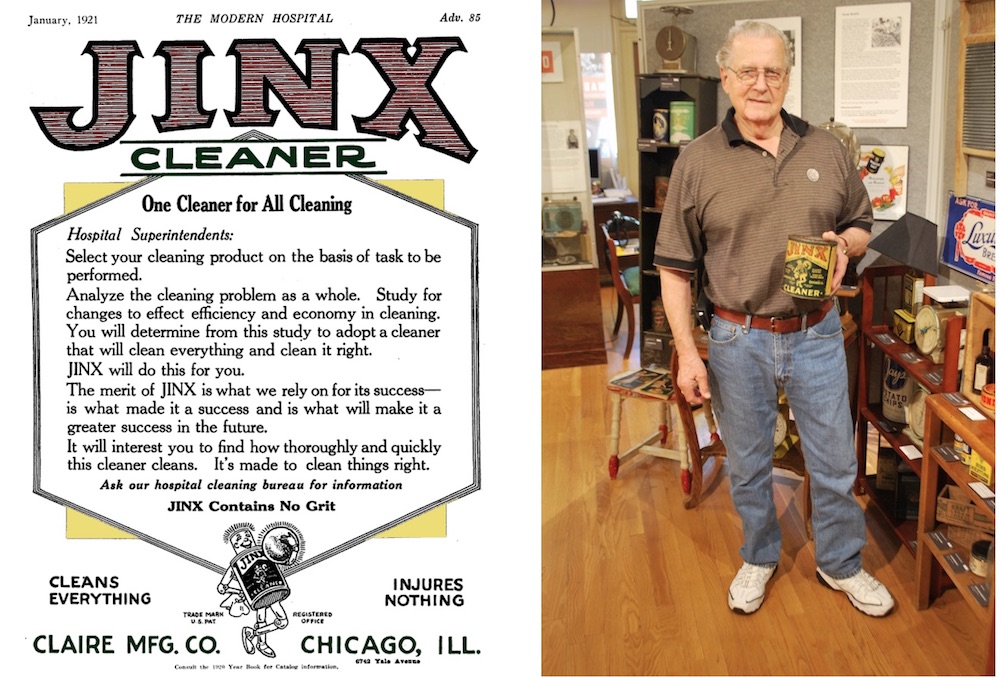

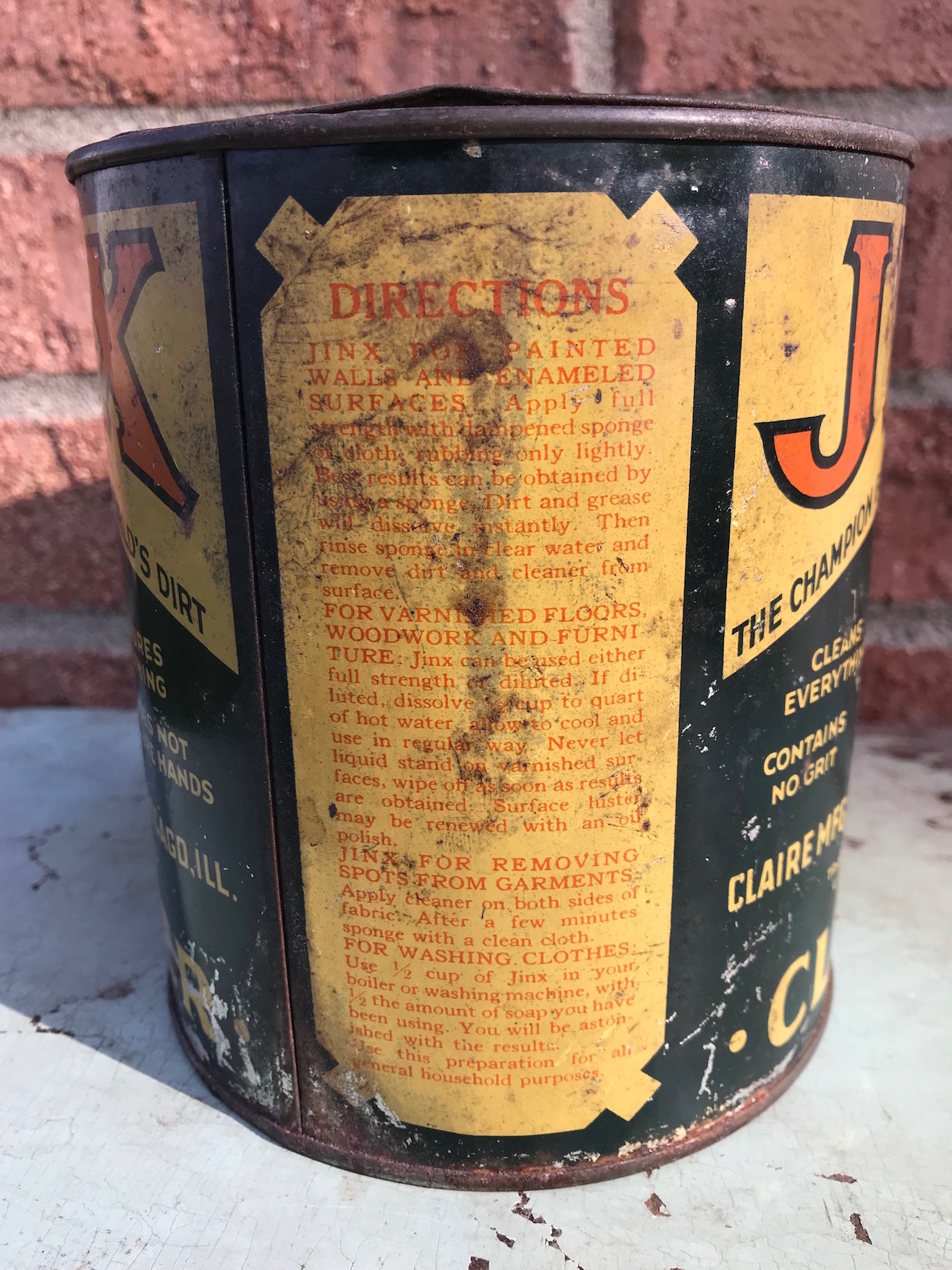

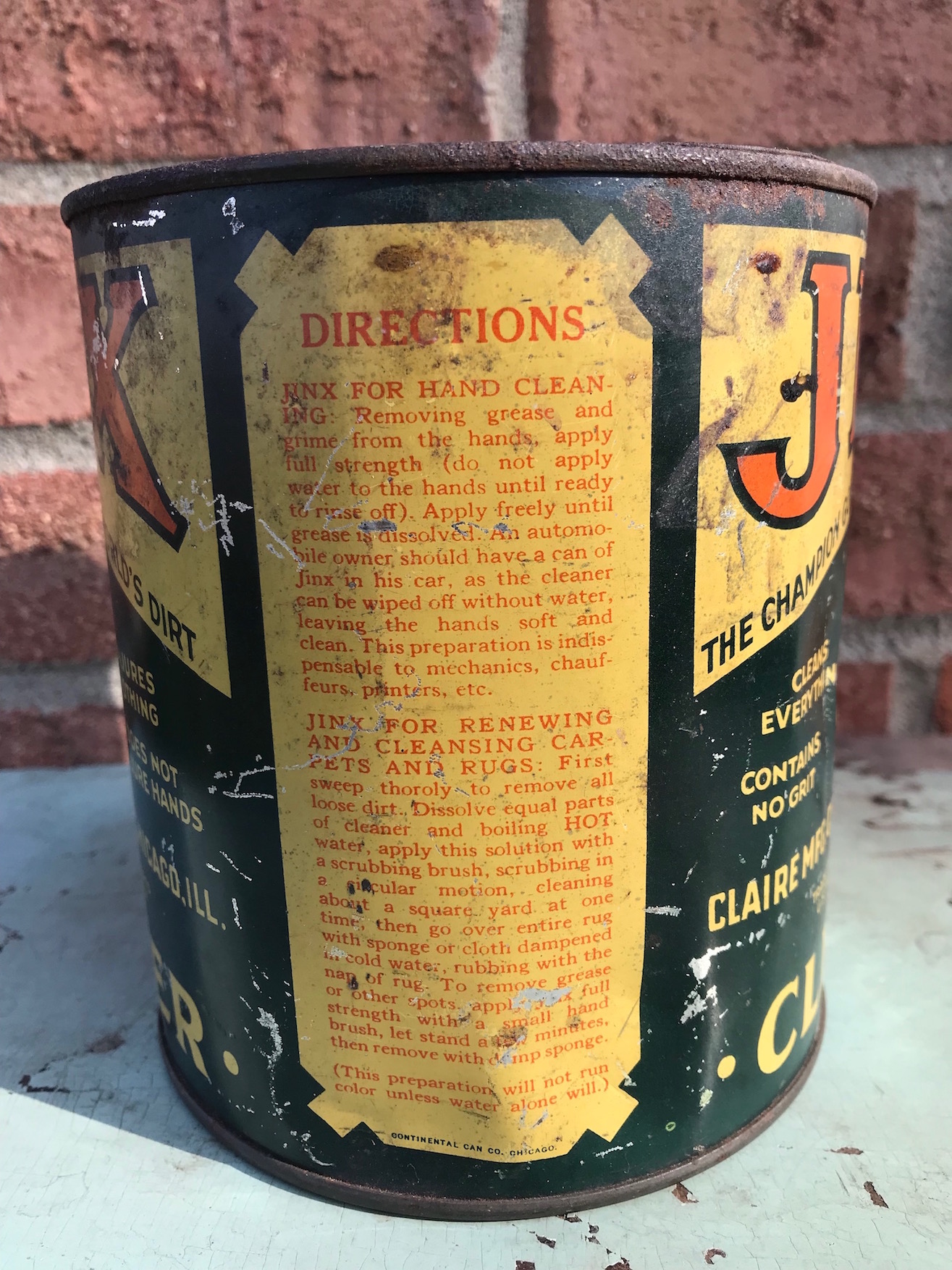

The superlatives were excessive even by the lenient standards of the era. The total lack of any information about the chemical makeup of the Jinx formula, however, was quite typical. Even the vintage container in our museum collection—a big beautiful 27 oz. wonder made by the Continental Can Co.—offers nary a hint as to the science behind the magic. The “what,” “when,” and “where” of any product was far more important to the buying public than the “how.” And if you wanted to know what Jinx could do, the answer was seemingly, whatever you wanted, anywhere you needed it.

The superlatives were excessive even by the lenient standards of the era. The total lack of any information about the chemical makeup of the Jinx formula, however, was quite typical. Even the vintage container in our museum collection—a big beautiful 27 oz. wonder made by the Continental Can Co.—offers nary a hint as to the science behind the magic. The “what,” “when,” and “where” of any product was far more important to the buying public than the “how.” And if you wanted to know what Jinx could do, the answer was seemingly, whatever you wanted, anywhere you needed it.

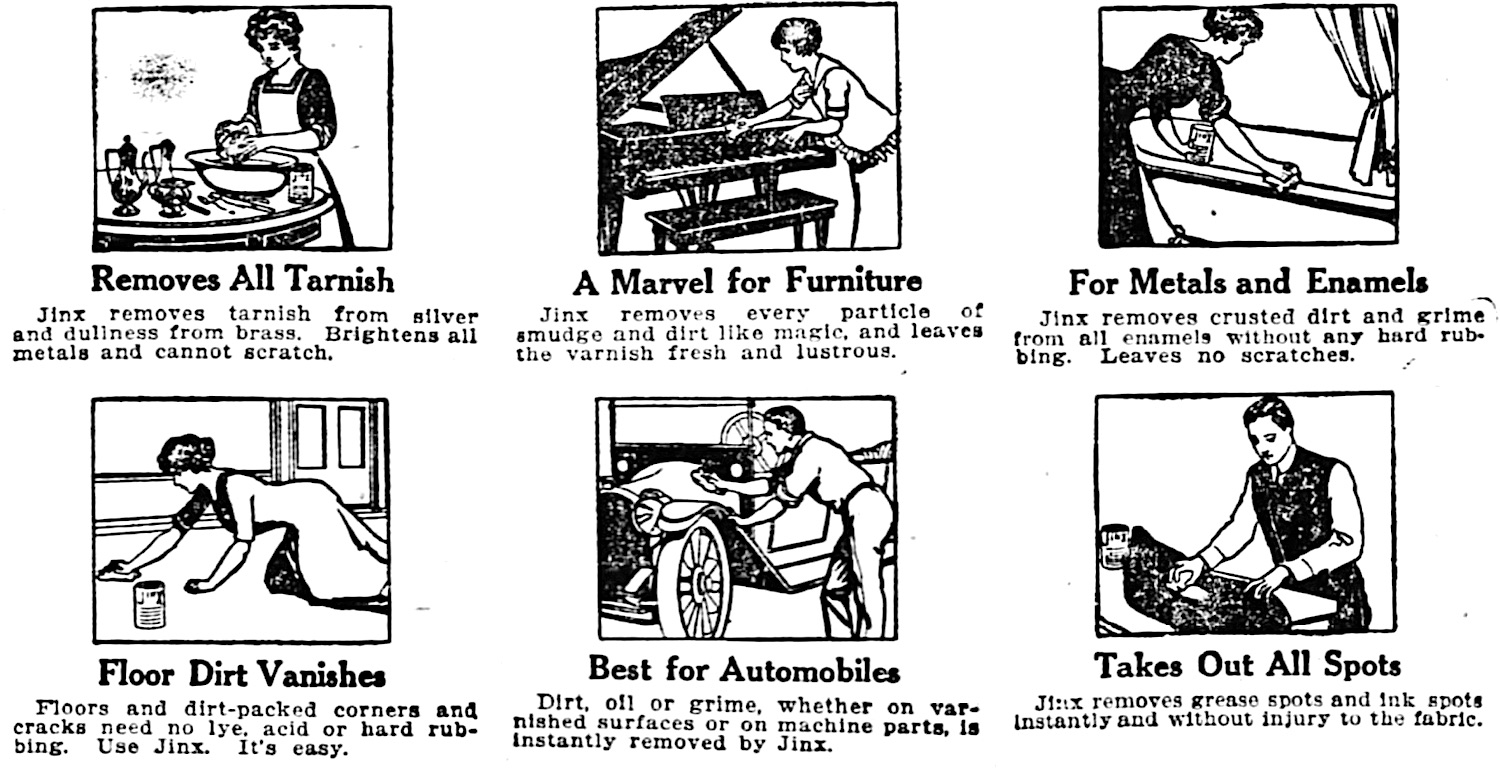

“In fact, it has so many thousands of uses that it would almost bankrupt the English language to try to explain them all,” blurted a Jinx ad, and yet it tried all the same. “It washes clothes and fabrics, from laces to blankets, without any more need of rubbing. It cleans bathtubs and cut-glass, pianos and pans, automobiles and silverware, rugs and buck-skin shoes, sinks and woodwork, machinery and leather, ink and lead from the hands of the printer, grease and grime from the hands of the mechanic—instantly, completely, without the need of one drop of water.”

For a more measured assessment of our artifact, we can turn to a 1914 issue of the Automobile Trade Journal, which reviewed Jinx upon its debut in the market.

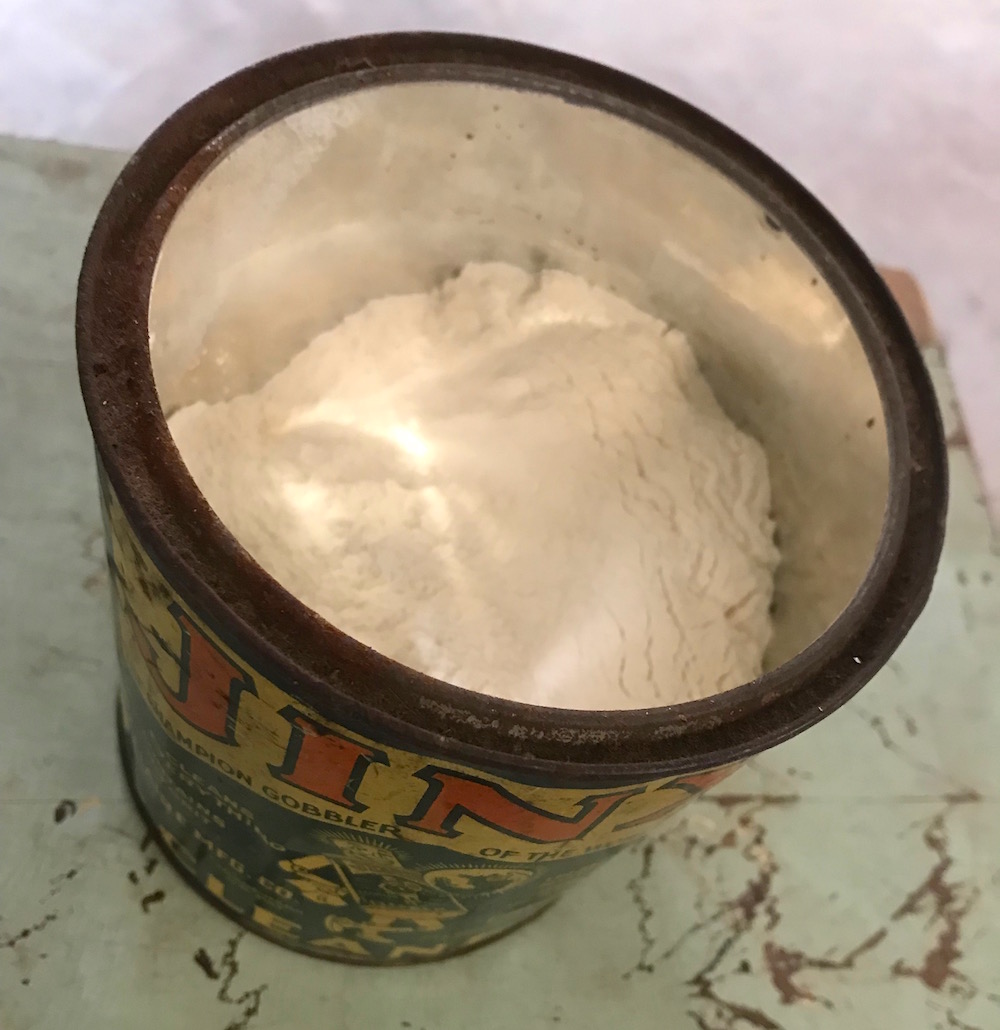

“Claire Manufacturing Company, 336-38 W. 63rd Street, Chicago, Ill., is offering a cleaner, called Jinx, same being a white, jelly-like paste, which can be used in its natural state or diluted in water for cleaning purposes. It possesses the quality of changing hard into soft water, and can be used for removing grease, oil, etc., without danger of its harming the finish on the car. A 2 lb. tin sells at 12-1/2 cents.”

Since the Jinx solution is compared to a jelly-like paste above, and is more poetically described in original ads as “soft, satiny, creamy and pure white,” we were a bit perplexed to remove the lid of our museum tin only to find a clumpy, flour-like powder instead. It’s certainly logical that 100 years of dormancy will change the chemistry of a thing. But since we don’t know what that chemistry originally was, we can only speculate.

II. Smudgy Origins

Speculation is also a big factor when it comes to sorting out the early years of the Claire Manufacturing Company itself. Despite the company’s long legacy of success—and the strong promotional push of the Jinx Cleaner in the 1910s (at least in the Midwest)—it’s quite difficult to determine (a) who actually organized the business in the beginning, and (b) who developed the cleaning formula that made the creation of a business necessary. Even the inspiration for the name “Claire” is a bit of a lingering mystery.

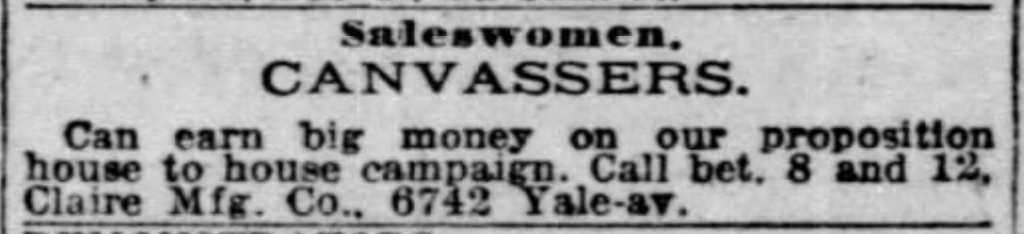

Former company vice president Val Kaspar, who joined Claire MFG in 1967, believes the original 1913 business was backed by more than a dozen investors, and had a storefront location at 6742 S. Yale Avenue in Englewood. The earliest listings I could find—from 1914—put the original headquarters slightly further north at 336 W. 63rd Street, but this was likely the site of the home office, rather than the storefront/factory. The Yale Avenue address begins appearing in Tribune classified ads in the early 1920s and would remain a central base for the company into the 1940s.

[A 1920 classified ad seeking door-to-door saleswomen to push Claire products. The company address is already listed at 6742 S. Yale Avenue, where Claire would remain for several decades.]

[A 1920 classified ad seeking door-to-door saleswomen to push Claire products. The company address is already listed at 6742 S. Yale Avenue, where Claire would remain for several decades.]

Other early advertisements muddy the waters by naming Claire MFG Co. as the “manufacturer of Jinx,” but a different business—E.A. Hamburg & Co., 1408 Masonic Temple Building—as its “sole distributors.”

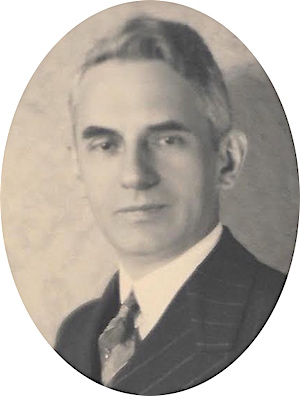

As for the names of the folks running the operation, we can at least confirm from an Englewood neighborhood newspaper that the aforementioned municipal court judge Theodore F. Ehler (1877-1956) was already on board as a stockholder and company secretary by as early as 1917—when he was still just a young lawyer. A second man, John A. Metz [pictured], was serving as Claire’s president at the time, though he was far better known for his role as president of the city’s Carpenters Union during the same period. By 1922, a new president, E. N. Davies, is named in the Certified List of Domestic and Foreign Corporations, with Ehler still on as secretary. Metz had died in 1919.

As for the names of the folks running the operation, we can at least confirm from an Englewood neighborhood newspaper that the aforementioned municipal court judge Theodore F. Ehler (1877-1956) was already on board as a stockholder and company secretary by as early as 1917—when he was still just a young lawyer. A second man, John A. Metz [pictured], was serving as Claire’s president at the time, though he was far better known for his role as president of the city’s Carpenters Union during the same period. By 1922, a new president, E. N. Davies, is named in the Certified List of Domestic and Foreign Corporations, with Ehler still on as secretary. Metz had died in 1919.

According to Kaspar, “Mr. Ehler performed legal matters for Claire, and since the money was very tight and business very poor, he was compensated for his labor by giving him stock in the company. Eventually, to settle his bill, he was given controlling stock and keys to the store.”

Ehler didn’t take over Claire for good until the early 1930s, when the business was reeling from the Depression. Before that, he was far more occupied dishing out courtroom punishment to gangsters and useless husbands. That leaves a gap of more than 10 years (basically all of the 1920s) in which we’re mostly left to guess at the inner workings of the Claire company. For all we know, Mr. Jinx himself was running the show.

III. The Mascot

While ads continued to suggest that the “whole country” was “going wild” for Jinx during its first few years on the shelf, it’s more likely that the product was a moderate success, rather than a sensation (Claire MFG’s capital stock did at least increase from $25,000 to $60,000 in 1917). Set against the backdrop of World War I, though, it was hard to properly gauge any product’s true potential.

So, as the war neared an end, the stockholders at Claire looked to ride a new wave of American optimism and re-introduce Jinx to the nation for a second go-around. They encouraged their advertising agency, Chas. H. Fuller (also one of the Ford Motor Company’s first agencies), to ramp things up in 1918, starting with the creation of a new product mascot—something along the lines of the Michelin Man or the new Morton Salt Girl.

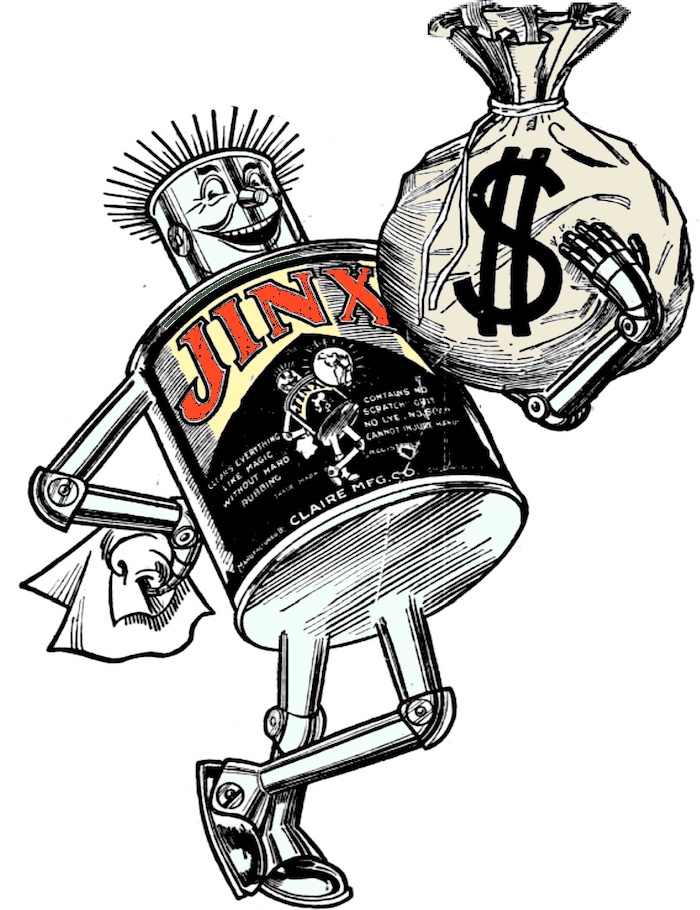

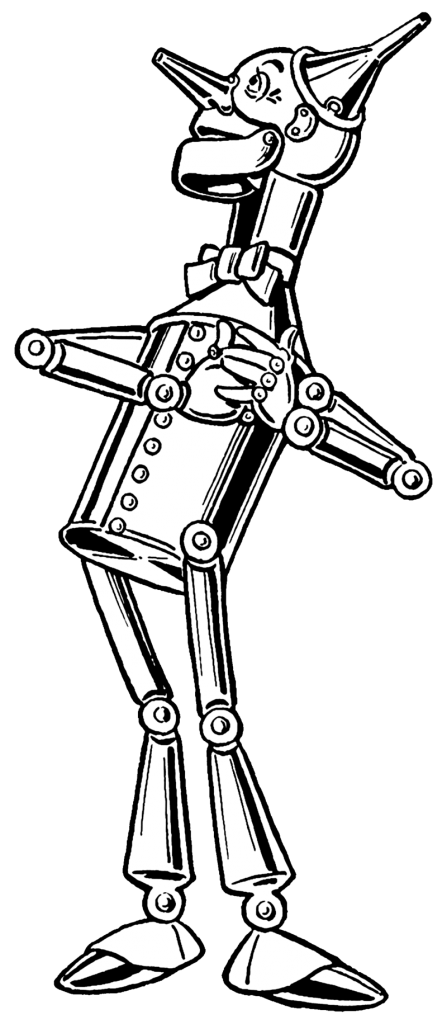

For their inspiration, the ad men at the Fuller offices seem to have turned to the original Wonderful Wizard of Oz illustrations of Chicago artist William Wallace Denslow—specifically his depiction of the Tin Woodman [pictured] in L. Frank Baum’s popular book.

For their inspiration, the ad men at the Fuller offices seem to have turned to the original Wonderful Wizard of Oz illustrations of Chicago artist William Wallace Denslow—specifically his depiction of the Tin Woodman [pictured] in L. Frank Baum’s popular book.

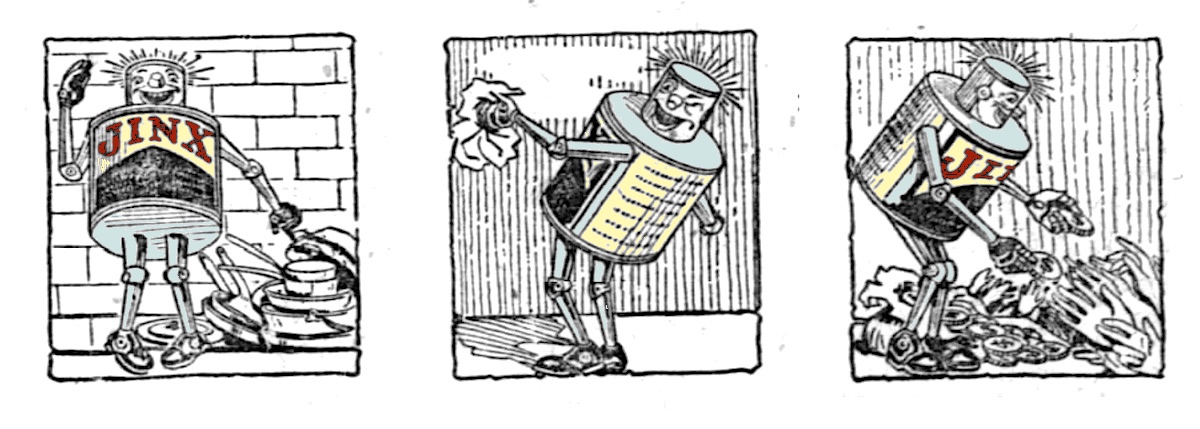

From this template was born “Mr. Jinx”—aka “The Champion Gobbler of the World’s Dirt”—a fastidiously clean metallic man with a Jinx can for a torso [since the Jinx can also now featured a picture of Mr. Jinx, an infinite repeating paradox of Jinx-upon-Jinx imagery was thus created].

The new campaign was backed by a door-to-door sales effort (employing mostly women to sell to women) along with plenty of other gimmicks to help the world choose Jinx as their all-purpose cleaner. At a charity event at Comiskey Park, for example, representatives from Chas. H. Fuller and other local ad agencies took part in a relay race while dressed as popular advertising characters of the day, including the Carnation “Contented Cow,” the Borax Mule, and the O-Cedar Polish Lady. Fuller employee George Stauber was the lucky guy who got to dress as Mr. Jinx, opposed by what was almost assuredly a painfully racist interpretation of the famed Gold Dust Twins from Fairbanks’ Washing Powder. I don’t know who won, but no result probably looks good in that scenario.

[Mister Jinx hard at work, 1918]

[Mister Jinx hard at work, 1918]

Claire also started running full-page newspaper ads, often incorporating write-in contests to entice readers to interact personally with the Jinx brand.

“I Have Dollars Galore I Want to Give Away,” Mr. Jinx announced in a 1918 Tribune ad. “You know me. I’m Jinx. Your old friend Jinx. The chances are you have me out in the kitchen now. . . . I am everybody’s friend; except dirt’s. And I am going to make a whole lot more friends. I have been pretty prosperous. Want to pass it around. So send along a new use for me, how to use me, and get a dollar bill.”

Each week, Jinx would ask for more entries into the contest, with readers suggesting new Jinx uses starting with a different letter of the alphabet. If the suggestion wasn’t already in the “Jinx Dictionary” and presumably not perverse in nature, the contestant would win themselves a buck, which was no small change back then.

Each week, Jinx would ask for more entries into the contest, with readers suggesting new Jinx uses starting with a different letter of the alphabet. If the suggestion wasn’t already in the “Jinx Dictionary” and presumably not perverse in nature, the contestant would win themselves a buck, which was no small change back then.

Again, it’s hard to say how fruitful this aggressive marketing strategy actually was, but judging by the relatively conservative approach the Claire MFG Co. took in advertising later in the 1920s, my guess is that Mr. Jinx hadn’t quite become the Morton Salt Girl. Competition in the cleaning product industry was just too fierce.

[LEFT: Jinx’s versatility allowed Claire to target a wide range of trade magazines, from automobile journals to medical publications like this 1921 issue of The Modern Hospital. RIGHT: Former Claire vice president Val Kaspar, 79, holds a vintage Jinx can during a visit to the Made In Chicago exhibit at the Edgewater Historical Society in 2018]

[LEFT: Jinx’s versatility allowed Claire to target a wide range of trade magazines, from automobile journals to medical publications like this 1921 issue of The Modern Hospital. RIGHT: Former Claire vice president Val Kaspar, 79, holds a vintage Jinx can during a visit to the Made In Chicago exhibit at the Edgewater Historical Society in 2018]

IV. A Family Business is Born

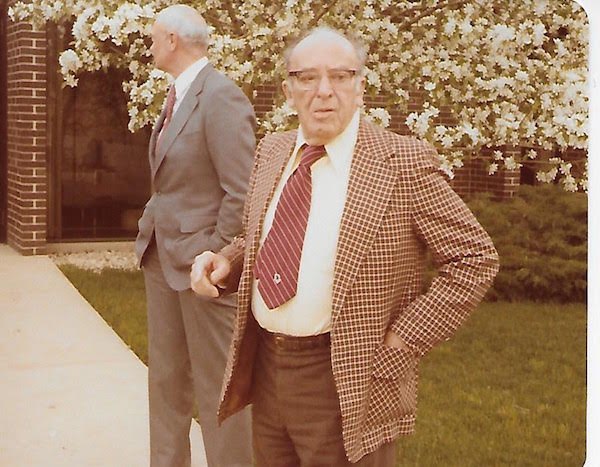

And so, as the Depression threatened to muzzle the World’s Greatest Gobbler of Dirt once and for all, Judge Theodore Ehler was asked to try and save the business that he’d mostly been assisting from the sidelines as a legal analyst for 20 years. Was he enthusiastic about it? Well, his preference was clearly to keep his day job sitting on the bench, doling out sentences. But as a Republican, he was facing almost impossible odds of re-election up against Chicago’s growing Democratic political machine. The Claire MFG Co. became a worthy distraction.

Theodore Ehler [pictured] was an Englewood lifer. His law office was located at 719 W. 63rd Street, just around the corner from where his own father’s blacksmithing shop had been (62nd and Halsted) back in the 1880s. He came to see the growth of Claire and other commercial businesses in the area as emblematic of Englewood’s rise from an agricultural frontier town to a modern piece of the Chicago metropolitan puzzle.

Theodore Ehler [pictured] was an Englewood lifer. His law office was located at 719 W. 63rd Street, just around the corner from where his own father’s blacksmithing shop had been (62nd and Halsted) back in the 1880s. He came to see the growth of Claire and other commercial businesses in the area as emblematic of Englewood’s rise from an agricultural frontier town to a modern piece of the Chicago metropolitan puzzle.

“From truck gardens and open prairie to a thriving, throbbing business community, the equal of which many of our cities would be proud to boast,” Ehler had written in a 1921 editorial for the Englewood Economist. “From crossroads with a few country stores and scattered homes to a hustling, bustling business section, with its miles of paved streets, its beautiful stores, theatres, banks and other improvements that go to make up a modern city; such has been the transformation of that part of Englewood surrounding Halsted and 63rd Sts. within the short space of a quarter of a century, as witnessed by this writer.”

Even after re-organizing the business in 1933, Ehler kept the headquarters at the same humble Englewood storefront plant on South Yale Avenue through World War II.

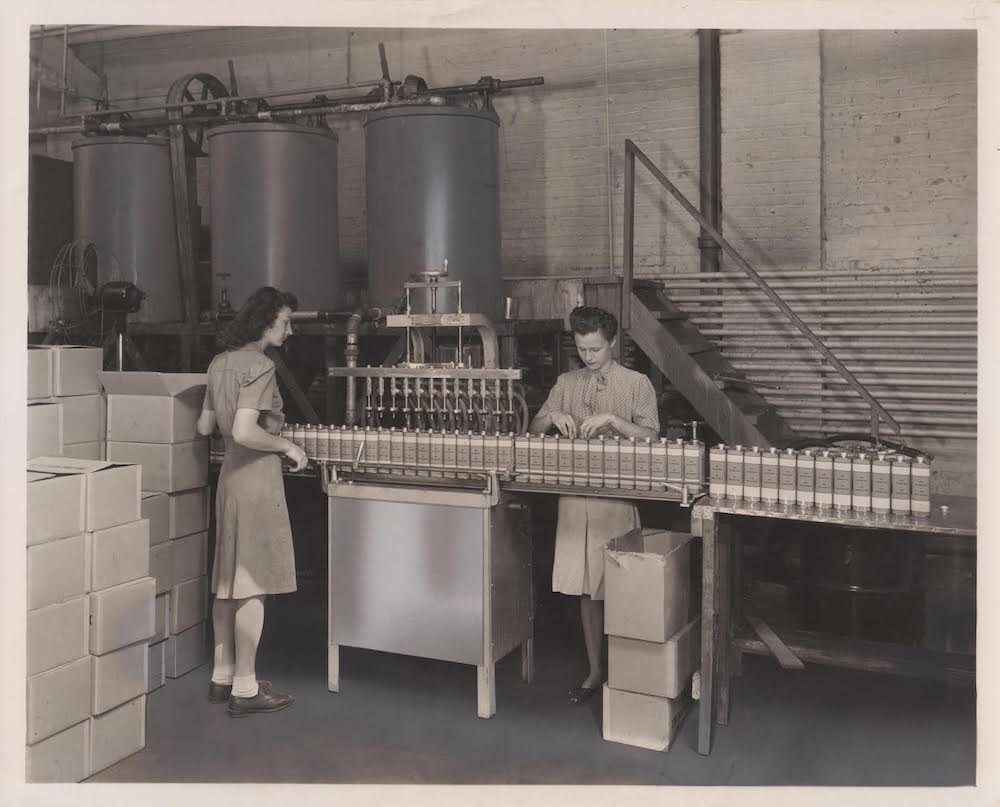

[Women working on Claire’s Pineheart production line, c. 1947]

[Women working on Claire’s Pineheart production line, c. 1947]

There were certainly changes under the new regime, however. Early on, the judge installed his son Herbert Ehler (1900-1983) as the new company president, then brought in his young son-in-law Raymond Lawton Evans (1913-1984) as a product manager, all while maintaining his own longtime role as secretary. Call it nepotism if you like. For Theodore, it was about being practical.

Claire was now a small family-owned business, and after another loss in a heated election in 1938, ex-Judge Ehler had to start looking at it as his new best hope at a lasting legacy . . . even if it meant asking the next generation to do all the heavy lifting.

During the 1930s and 1940s, Herb Ehler [pictured]—a former Hudson automobile salesman who had all the sales tricks of, well, a used car salesman—became Claire’s public face. By this point, the business had expanded well beyond just Jinx cleaner, but with purse strings tight, it was largely dependent on one man alone to sell the entire line of goods.

During the 1930s and 1940s, Herb Ehler [pictured]—a former Hudson automobile salesman who had all the sales tricks of, well, a used car salesman—became Claire’s public face. By this point, the business had expanded well beyond just Jinx cleaner, but with purse strings tight, it was largely dependent on one man alone to sell the entire line of goods.

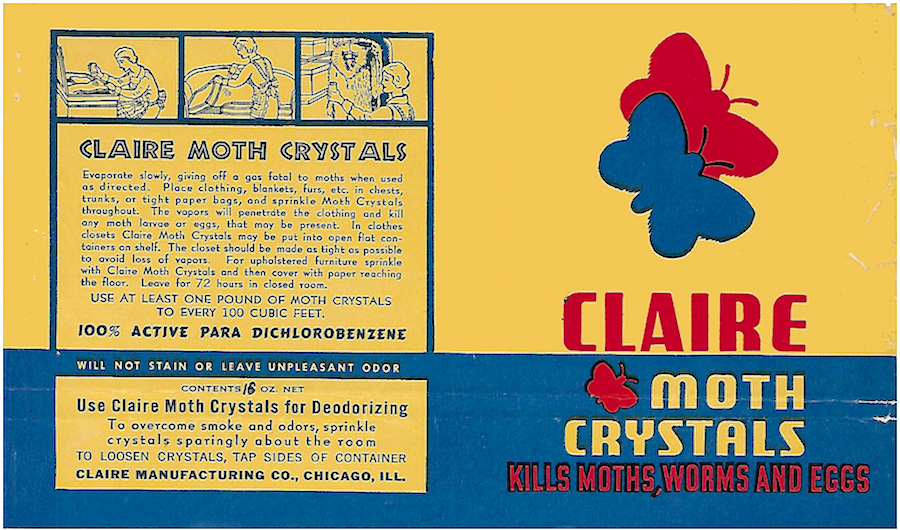

“Herb was the only salesman the company had,” according to Val Kaspar. “He spent many of his days walking south side Chicago streets, going door to door, trying to sell their products. Corner saloons became good places to get customer orders. Herb would buy a round of beer [which had just recently become a legal thing to do again], then offer cleaning products, moth crystals, Pineheart pine oil soap, or pine disinfectants to the people assembled at the bar.”

Ray Evans, meanwhile—a former employee of the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture—was tasked with running the show at the Yale Avenue plant, trying to match Herb Ehler’s pace. “Products were low cost,” Kaspar says, “but the best quality, and they generated a loyal customer base.” [Incidentally, Ray Evans—along with being Theodore Ehler’s son-in-law, was also Val Kaspar’s father-in-law. I think that means Kaspar and Ehler are related, too, but I can’t even attempt to wrap my mind around such complexities].

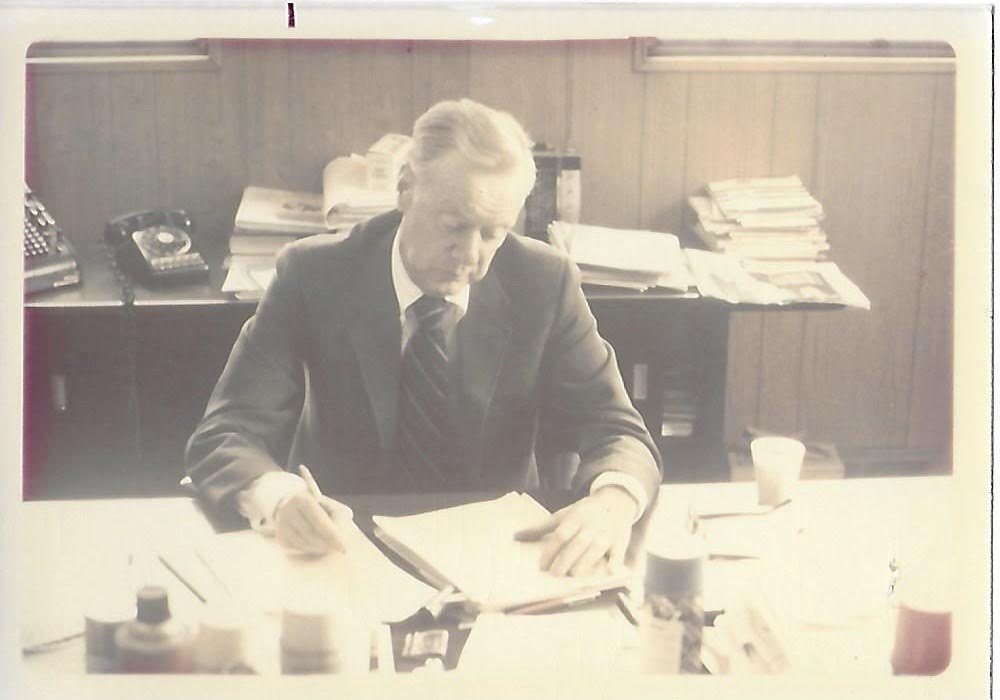

[Raymond Evans at work in the Claire offices, in his later years, c. 1960s]

[Raymond Evans at work in the Claire offices, in his later years, c. 1960s]

Just as business was really starting to pick up, another world war cast everything into doubt. Herb Ehler joined the Coast Guard after Pearl Harbor, while Ray Evans stayed behind to support his family and keep the Claire plant working. By the time Herb returned to civilian life, he had made a new friend—a fellow Coast Guarder named Maury Aronson. A graduate of Michigan State, the energetic Aronson had worked as a salesman for Wyandotte Chemical before the war, and when the fighting was over, Herb Ehler convinced him to bring his talents to Englewood, where they planned out a new side business as a sort of sister enterprise to Claire.

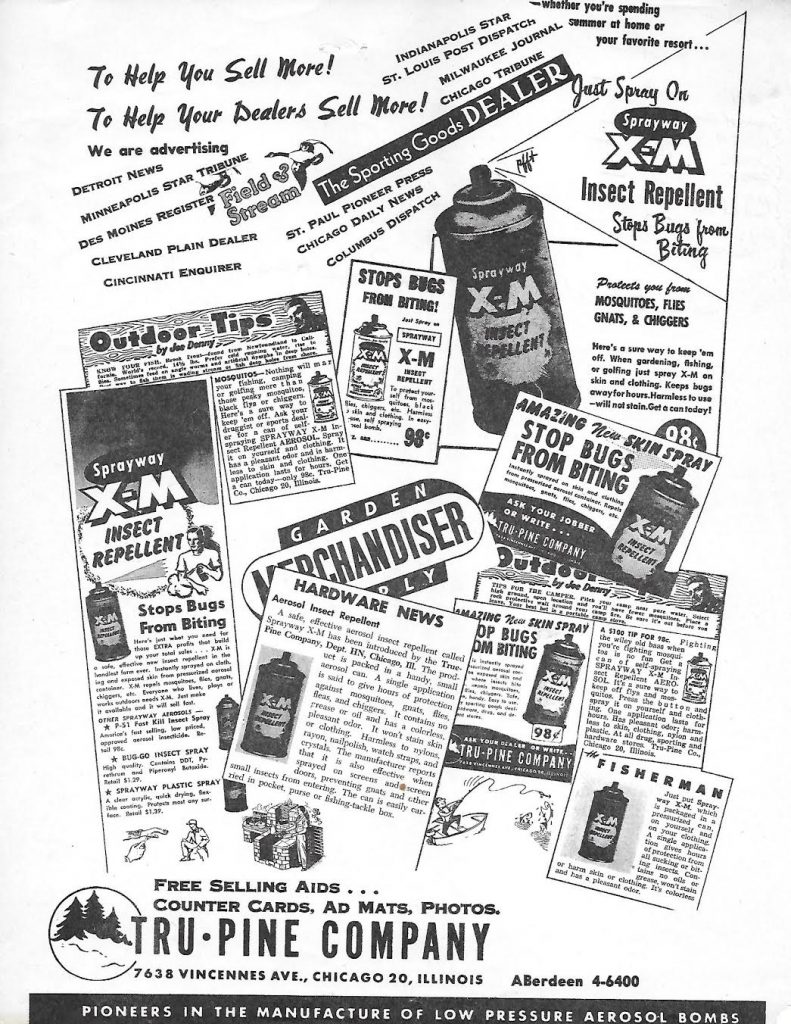

“Herb, with Maury’s help, started the Tru-Pine Company and soon moved to larger quarters at 7638 Vincennes Avenue,” Kaspar says. “Claire MFG moved next door to 7648 Vincennes. They were making and selling lots of Pine Heart Pine Oil Soap, Moth Crystals, Pine Disinfectant and Glass Wax. Maury proved to be a real asset and Herb and Ray could not be happier. Life was good!”

[Above: The former Claire-Sprayway facility at 7640 S. Vincennes Ave., 1965 vs. 2018]

[Below: Warehouse workers, possibly in the new Vincennes facility, boxing Pineheart soaps. Most Claire employees had to do double-duty as sales reps, too, to keep the product moving.]

V. The Sprayway Way

The new Claire factory, which was slightly outside the confines of Englewood—near Harvard Avenue and between 76th and 77th streets—offered up 15,000 square feet of space, enough for the business to expand to 15 workers by 1953. Now, after 40 years in business, a workforce of a little more than a dozen might not sound like a thriving enterprise. But in its small corner of the market, Claire was surpassing most of its sales goals. A big reason for this was the company’s successful foray into aerosols—a pretty novel and celebrated innovation of the time.

Ehler, Evans and Aronson started developing aerosols shortly after the war. They’d been inspired by the freon-pressurized insecticides the U.S. Army had employed overseas—encased in long steel containers. When the Continental Can Company developed a 3-piece can for packaging similar “aerosol” products in the late ‘40s, a new commercial industry opened up.

“Claire contracted with DeMert & Dougherty Co. to make Aerosol Room Air Fresheners labeled with the Claire name,” says Kaspar. “People loved them! A decision was made to get into aerosol production and quick. Herb, Maury and Ray looked for a name for their spray products. They thought the idea of spraying away odors was unique. Thus they coined the name ‘spray-away.’”

That brand was quickly adapted to “Sprayway,” and by 1958, the Tru-Pine Company had re-branded itself Sprayway Incorporated. Around the same time, the joint businesses of Claire and Sprayway purchased additional offices and warehouse space at 7620 S. Harvard Avenue, taking over most of the block.

[Promotional photos for Sprayway Glass Cleaner, 1960s]

[Promotional photos for Sprayway Glass Cleaner, 1960s]

“To make and market these products, they needed the equipment and expertise to do so,” Kapsar explains. “James Wail and Frank Schaefner were added to run the Alpha and Elgin filling lines. Ruggles Turner was in charge of maintenance and repairs to the filling equipment. Russ Murray joined Herb to expand Claire’s sales and grow the business. New manufacturer’s reps were added. In the early 1950s Ralph Scudder joined Sprayway to give Maury Aronson much needed help. Glen Fisher, a formulating chemist, was responsible for the many new aerosol products being developed. Bill Sindewald was responsible for warehousing and traffic needs. Anthony White, formerly with Continental Can Co., was brought in to run the plant. He made many contributions to Claire’s success.”

By this point in time, Theodore Ehler had passed on, and Herbert Ehler—nearing retirement age himself—wanted to run his growing business in a slightly warmer climate. He established a short-lived Sprayway factory in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, and moved down South to run it. Later, he dispatched his son Tom Ehler—the third generation—to return to Chicago and help run the original plant. There was no coaxing Herb back out of Florida.

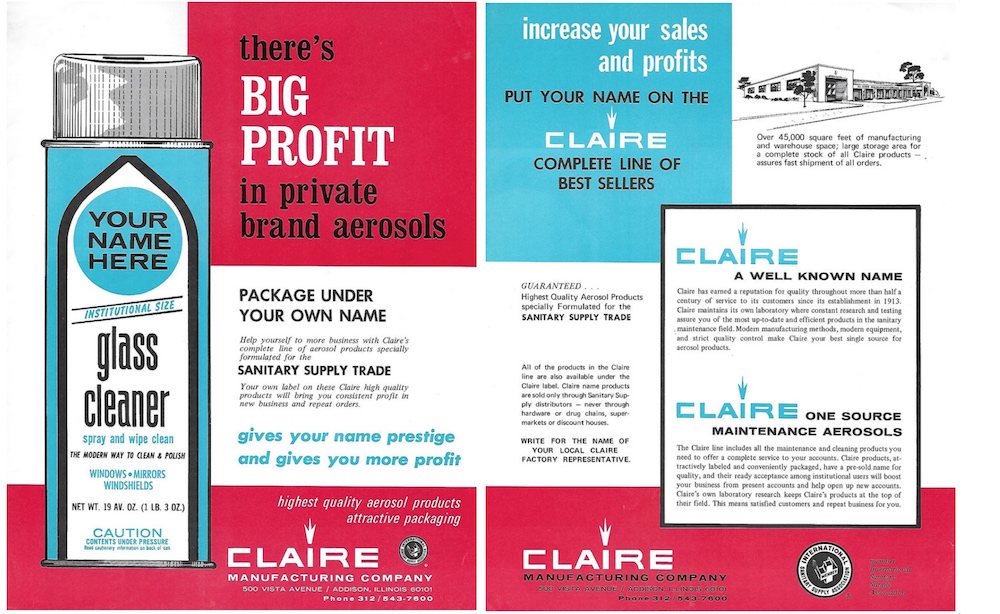

VI: Fluorocarbon Footprints

During the 1960s, sales manager Jim Murray helped guide Claire into the sanitary chemical supply trade, while Sprayway expanded into the glass, automotive, silk screen, and graphic arts industries. By the time Val Kaspar became Claire-Sprayway’s vice president in 1970, there were 43 employees at the Vincennes complex, producing 5 million units annually. [pictured below, from left: Jim Murray (VP of Sales), Val Kaspar (VP), and Thomas Ehler (President), c. 1970s]

With Kaspar’s promotion and Tom Ehler’s arrival, Claire-Sprayway looked well positioned to move confidently into the future. There was one chink in the armor, however—or more accurately, one hole in the ozone.

With Kaspar’s promotion and Tom Ehler’s arrival, Claire-Sprayway looked well positioned to move confidently into the future. There was one chink in the armor, however—or more accurately, one hole in the ozone.

“Just when things seemed to be humming along smoothly,” Kaspar recalls, “the ozone depletion theory of the fluorocarbon ozone controversy was gaining steam and was not going to go away. All of our propellants and blends that we used in our products in Chicago were fluorocarbons. If these were banned, we would be out of business!”

Claire had already been through a similar backlash in the ’60s when DDT—a component in their early insect sprays—proved to be an environmental nightmare. Now, new research from the University of California-Irvine in 1973 was galvanizing a movement against chlorofluorocarbons, as well.

To make matters worse, Kaspar, Tom Ehler, Ray Evans, and plant manager Tony White had just committed in 1973 to moving Claire-Sprayway to a new, larger factory about 20 miles west of Chicago in Addison, Illinois (a building formerly owned by the collapsing Kerr Chemical Co.). They chose the plant with a mind toward rapidly increasing growth in the aerosol trade, but now, things seemed to be teetering on the brink.

To make matters worse, Kaspar, Tom Ehler, Ray Evans, and plant manager Tony White had just committed in 1973 to moving Claire-Sprayway to a new, larger factory about 20 miles west of Chicago in Addison, Illinois (a building formerly owned by the collapsing Kerr Chemical Co.). They chose the plant with a mind toward rapidly increasing growth in the aerosol trade, but now, things seemed to be teetering on the brink.

“Another factor for moving the plant to the ‘burbs was crime,” recalls Mark Kaspar, Val Kaspar’s son. “The Englewood neighborhood was in serious decline. My father had his pride & joy— his first new car, a Chevy Corvair—stolen right off Vincennes while he was at work one day. It was never recovered. The plant was repeatedly broken into at night. I have vivid memories of the phone ringing at 1 or 2 in the morning from the Chicago police for my father. The alarm system would contact the police who would need my father to manually shut it off.”

Theodore Ehler’s utopian vision of Englewood wasn’t holding up. So, it was on to Addison.

[Claire plant at 500 Vista Ave. in Addison, IL; the company’s home from 1974 through to the 2010s]

[Claire plant at 500 Vista Ave. in Addison, IL; the company’s home from 1974 through to the 2010s]

As for the chlorofluorocarbon debate, corporations far larger than Claire were predictably pushing back against the highly publicized UC ozone studies, including DuPont, Allied Chemical and Union Carbide. Nonetheless, by the late ‘70s, the word had come down; the U.S. government finally banned the use of fluorocarbons in aerosols—a move that modern science certainly would support.

The new regulations could have been the death blow for Claire, particularly in the midst of their first factory move in 25 years. Thanks to some industrious chemists across the country, though, ozone-safe alternative formulations for most aerosol propellants were quickly devised. Most of these formulas still use volatile hydrocarbons like propane, n-butane, and isobutane, or in some cases, methyl and dimethyl ether—not exactly the most earth-friendly stuff in the world. Even so, the spray can business—while permanently scarred in many people’s eyes—did survive and thrive.

The new regulations could have been the death blow for Claire, particularly in the midst of their first factory move in 25 years. Thanks to some industrious chemists across the country, though, ozone-safe alternative formulations for most aerosol propellants were quickly devised. Most of these formulas still use volatile hydrocarbons like propane, n-butane, and isobutane, or in some cases, methyl and dimethyl ether—not exactly the most earth-friendly stuff in the world. Even so, the spray can business—while permanently scarred in many people’s eyes—did survive and thrive.

For Claire-Sprayway old-timers Ray Evans and Herb Ehler, however, the rollercoaster ride of aerosol ethics had taken a toll. With both men in failing health, the difficult decision was made to sell the business to a New Jersey company, Oakite Products.

“Tom Ehler, Maurice Aronson, Jim Murray and I were totally against selling the business,” Val Kaspar says. “However, Ray and Herb were the major stock holders and they had the final word.” [pictured below: Herb Ehler, foreground, and Oakite CEO Charles Rell just before the sale of the company in 1980]

Despite the sale, Claire continued to operate out of the Addison plant, and business actually grew steadily through the 1980s and ‘90s. Kaspar and Tom Ehler remained in leadership positions for much of that time, even after another major corporate sale in 1988—this time to a giant investment firm known as the Carlyle Group. Ehler eventually left on less than happy terms in 1992, while Val Kaspar retired after 40 years with the company in 2007. Any remnants of the old family business are no more.

Despite the sale, Claire continued to operate out of the Addison plant, and business actually grew steadily through the 1980s and ‘90s. Kaspar and Tom Ehler remained in leadership positions for much of that time, even after another major corporate sale in 1988—this time to a giant investment firm known as the Carlyle Group. Ehler eventually left on less than happy terms in 1992, while Val Kaspar retired after 40 years with the company in 2007. Any remnants of the old family business are no more.

Val Kaspar’s son Mark Kaspar, who was also a very helpful source for much of this history, told us that the Claire Manufacturing Company is now part of the PLZ Aeroscience family of companies, with the Claire-Sprayway offices now headquartered in Downers Grove. “Sadly,” he says, “production is no longer in the Chicago area. The Addison plant sits vacant, awaiting a buyer. Current manufacturing is now a short hop off U.S. 66 in Pacific, Missouri.”

Though today’s Claire is disconnected from the one his family helped build, Mark Kaspar is still loyal to the company and its brands. “Sprayway glass cleaner still remains my glass cleaner of choice,” he says. “Even with new owners, it will always have my DNA in it!”

Though today’s Claire is disconnected from the one his family helped build, Mark Kaspar is still loyal to the company and its brands. “Sprayway glass cleaner still remains my glass cleaner of choice,” he says. “Even with new owners, it will always have my DNA in it!”

Today, Mark can also purchase a new butane-enriched, spray-can version of “Mr. Jinx” All-Purpose Cleaner. It comes in a recyclable container and contains no ozone depleting compounds. Better still, it’s got a small homage to the original 1918 Mr. Jinx mascot still included on the side of the can. It’s a nice nod to the past—and a reminder of a small Englewood business that made the world just a little bit shinier.

[Workers on the Jinx Wax production line, c. 1947]

SOURCES

“Claire Manufacturing Company” newsletter by Val Kaspar

The Encyclopedia of the Industrial Revolution in World History, Volume 3, edited by Kenneth E. Hendrickson, III

“Official Minutes of Meeting: Claire Manufacturing Co.” – The Englewood Times, January 18, 1918

“Truck Gardens, Open Prairies, Now Englewood” by Theodore Ehler, the Englewood Economist, July 14, 1921

“Washing Apparatus, Engine Cleaners, etc.” – Automobile Trade Journal, April-June 1914

“Hold Services Today for Former Municipal Judge” – Southtown Economist, March 28, 1956

“I Have Dollars Galore I Want to Give Away” – full-page Jinx ad, Chicago Tribune, Feb 17, 1918

“Democrats Rolling In” – The Pantagraph (Bloomington, IL), Nov 10, 1938

“Variety in Advertising” – Agricultural Advertising, v. 26, 1914-15

Archived Reader Comments:

“Thank you to all who contributed for this article and thank you Andrew for it is very well written! Very cool story and great pictures. I can still remember the smell walking into the Addison plant. Some great minds and amazing people really made this place a family environment.” —Joe Ehler, 2018

“Fantastic, Andrew! You’ve uncovered things that are new to us! Thanks! By the way, I got a kick out of “I think that Kaspar & Ehler are related too, but, I can’t even attempt to wrap my mind around such complexities.” Yes, it’s a little confusing. Ray Evans married Theodore Ehler’s daughter Ariel. They had three daughters. Ariel { my mother, who goes by the nickname ‘Boots’ }, Linda & Carol. My father Val married Ray’s daughter Ariel { Boots }, so yes, Kaspar & Ehler are related by marriage.” —Mary Kaspar, 2018