Museum Artifacts: Motor Trend magazines (1961-1964), Report of the Warren Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy – Paperback Book (1964), “House Dope” employee magazines (1942-1945)

Made By: W. F. Hall Printing Company, 4600 W. Diversey Ave., Chicago, IL [Belmont Cragin]

“A deluge of paper stock, ink, glue, and all other printing supplies and equipment enters the plant of W. F. Hall Printing Company, the world’s greatest printer of catalogs and magazines, in Chicago,” the Inland Printer reported in 1949. “These materials leave the plant as a tremendous volume of printed matter bound into millions of mail order catalogs, seed catalogs, pocket-size books, as well as scores of magazines. . . . If the roll stock which is consumed annually in this plant were unrolled and pasted end to end, it would provide ten paper sidewalks to the moon and have sufficient left over to provide for ten paper sidewalks completely encircling the earth.”

In a city with no shortage of esteemed and prolific printing houses (be it Donnelley, Rand McNally, Cuneo, etc.), W. F. Hall is something of an unjustly forgotten juggernaut. Organized in the midst of the Columbian Exposition of 1893, Hall became the “printing press of the people” in some respects, churning out some of the most socially relevant—if not always high brow—reading material of the 20th century. The firm was quick to embrace new technology in its endless quest for bigger volume and faster speeds, but it also cast its wide net without prejudice, amplifying many different types of voices in the process.

In a city with no shortage of esteemed and prolific printing houses (be it Donnelley, Rand McNally, Cuneo, etc.), W. F. Hall is something of an unjustly forgotten juggernaut. Organized in the midst of the Columbian Exposition of 1893, Hall became the “printing press of the people” in some respects, churning out some of the most socially relevant—if not always high brow—reading material of the 20th century. The firm was quick to embrace new technology in its endless quest for bigger volume and faster speeds, but it also cast its wide net without prejudice, amplifying many different types of voices in the process.

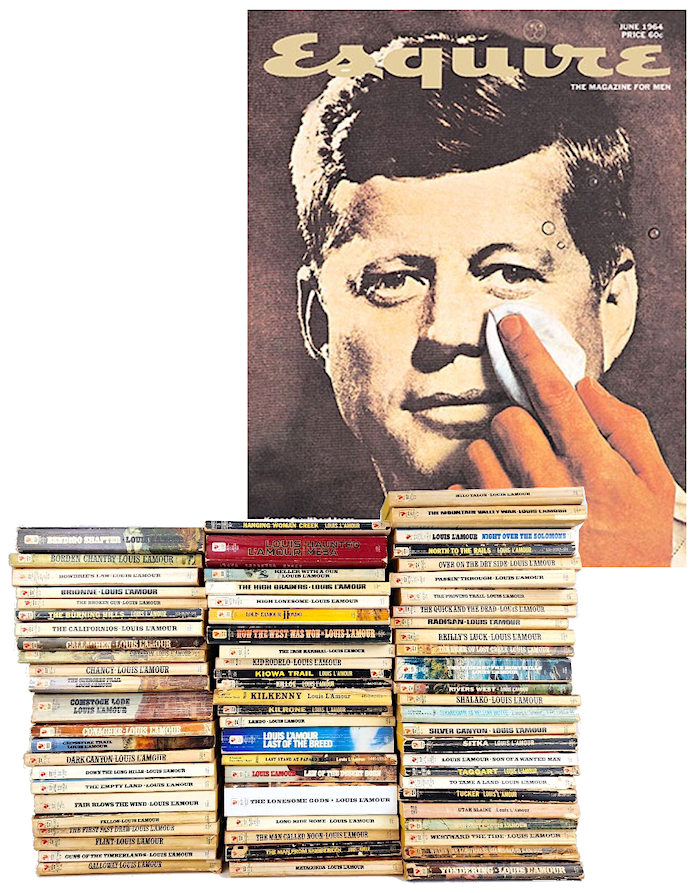

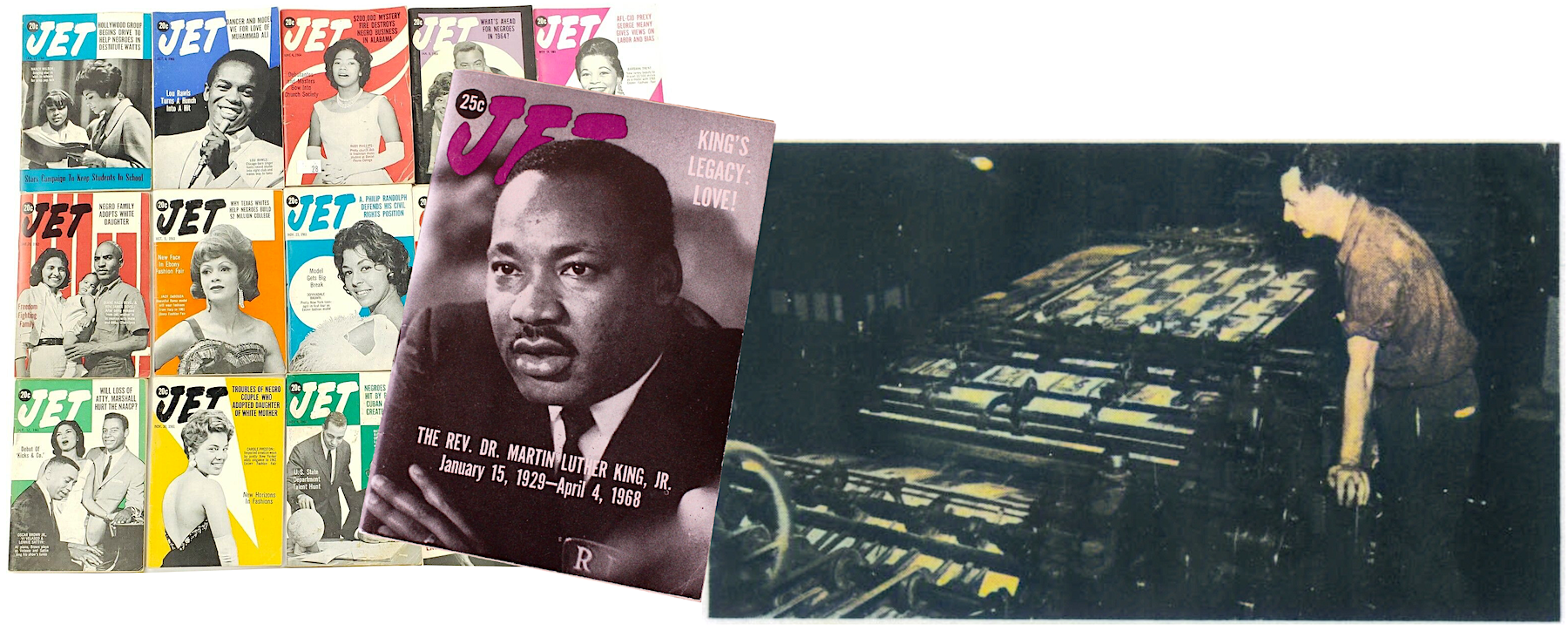

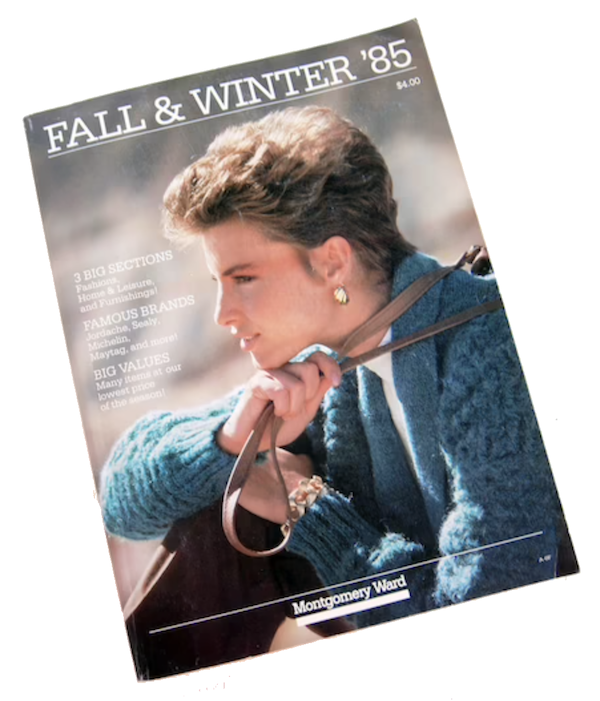

Between 1925 and 1985, during its 60-year occupancy of a cavernous mega-complex in Chicago’s Belmont Cragin neighborhood, W. F. Hall held a claim as the largest printing company on Earth. If you picked up a magazine, flipped through a catalog, or read a paperback novel during that period, you were inevitably going to encounter the company’s handiwork. The Hall portfolio included not only the popular mid-century Motor Trend magazines in our museum collection, but, among others: the hefty mail-order catalogs of Montgomery Ward, Sears, and Spiegel; the dime novels of Bantam and the New American Library; dentist’s office publications like Newsweek and Reader’s Digest; and some of Chicago’s culture-defining contributions to America’s sidewalk newsstands—including Esquire (founded by Arnold Gingrich in 1933), Playboy (founded by Hugh Hefner in 1953), and both Ebony and Jet (founded by John H. Johnson in 1945 and 1951, respectively).

[After 27 year-old Chicago-native Hugh Hefner, a former Esquire copywriter, cobbled together enough money to launch his own magazine in 1953, W. F. Hall soon became his printing partner. Hall would continue to print Playboy until 1985.]

W. F. Hall’s capabilities were seemingly limitless, and they seemed to draw few lines on who they’d do business with—although there is an old myth that they did require Hef to get the centerfold portions of Playboy printed elsewhere.

Some printing jobs also took priority over others. In 1964, for example, when the Report of the Warren Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy was completed, President Lyndon Johnson supposedly “felt it was of vital importance that the whole truth about President Kennedy’s death be given to the world as quickly as possible.” A paperback edition of the report was thus created through Bantam Books and rushed off to Chicago.

“The first printing for 700,000 copies of this 800-page low-priced edition of the Warren Commission Report has been made available to the public just 80 hours after President Lyndon B. Johnson released it,” the editor of Bantam wrote in the introduction to the paperback. “This establishes a new milestone in book publishing. A force of over 150 skilled men and women at W.F. Hall Printing Company in Chicago, Illinois, one of the largest printing plants in the world, accomplished this gigantic task by working in eight-hour shifts around the clock.”

“The first printing for 700,000 copies of this 800-page low-priced edition of the Warren Commission Report has been made available to the public just 80 hours after President Lyndon B. Johnson released it,” the editor of Bantam wrote in the introduction to the paperback. “This establishes a new milestone in book publishing. A force of over 150 skilled men and women at W.F. Hall Printing Company in Chicago, Illinois, one of the largest printing plants in the world, accomplished this gigantic task by working in eight-hour shifts around the clock.”

These days, the atmosphere at the old W. F. Hall HQ is considerably more relaxed. As a loose tie-in to the company’s days as a printer of automobile magazines, part of the long abandoned Cragin plant (specifically a building that housed its Rotoprint subsidiary) has now been converted into Chicago’s largest classic automobile museum, Klairmont Kollections. . . . Since 2022, it’s also been the home of a little exhibit called the Made In Chicago Museum.

All the more reason, then, to pay proper respects to this building, the company that thrived here, and the multiple moon journeys worth of content that was born here.

History of W. F. Hall Printing Company, Part I: Hall of Fame

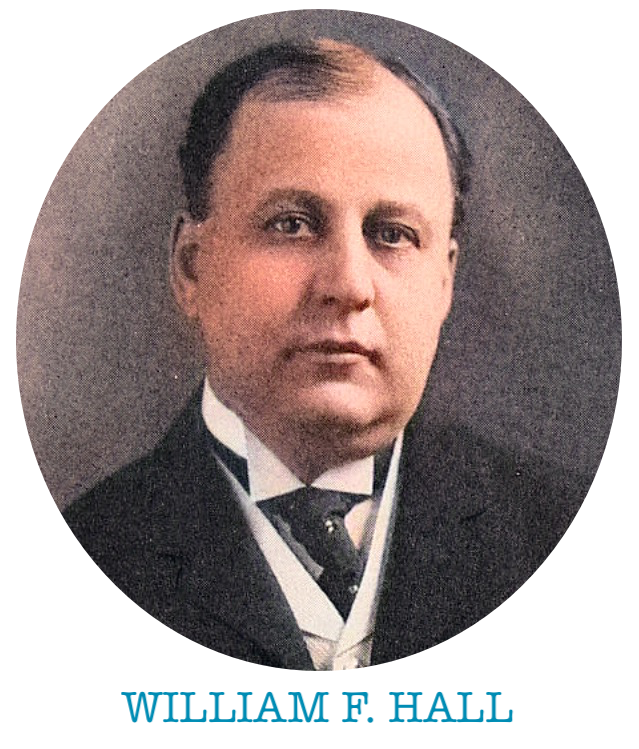

William Franklin Hall was born in Columbia City, Indiana, in 1862; the fifth of eight kids. The family patriarch, a blacksmith and repairman named Alexander Hall, died when William was still a boy, so it mostly fell on his elder twin brothers Peter and John Adolfus to help support their mother Frances and raise the younger siblings. John A. Hall was more than a decade older than William and worked in the local printing trade, so this was likely young Willie’s introduction to that line of business.

According to a later recounting in the Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette, William F. Hall “left school in 1879, when but a lad, and began to earn a living for himself by setting type in the Post Printing company’s office in Columbia City.” Some time between 1882 and 1885, depending on the source, William then opted to move to Chicago, where big brother John A. Hall had already found work with a printing house (we’re not sure which one).

According to a later recounting in the Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette, William F. Hall “left school in 1879, when but a lad, and began to earn a living for himself by setting type in the Post Printing company’s office in Columbia City.” Some time between 1882 and 1885, depending on the source, William then opted to move to Chicago, where big brother John A. Hall had already found work with a printing house (we’re not sure which one).

Upon arrival, W. F. Hall got one of his first gigs working as a type-setter for the Inter Ocean newspaper, then joined the J. L. Regan printing company, where he moved up the ranks to factory foreman. “He soon won the respect and cooperation of men of affairs in Chicago,” the Journal-Gazette claimed, “and grew to be a man of wealth and influence.”

According to the 1912 book, Story of Chicago in Connection with the Printing Business, Hall “demonstrated unusual forcefulness as a workman” and “ambition to advance.”

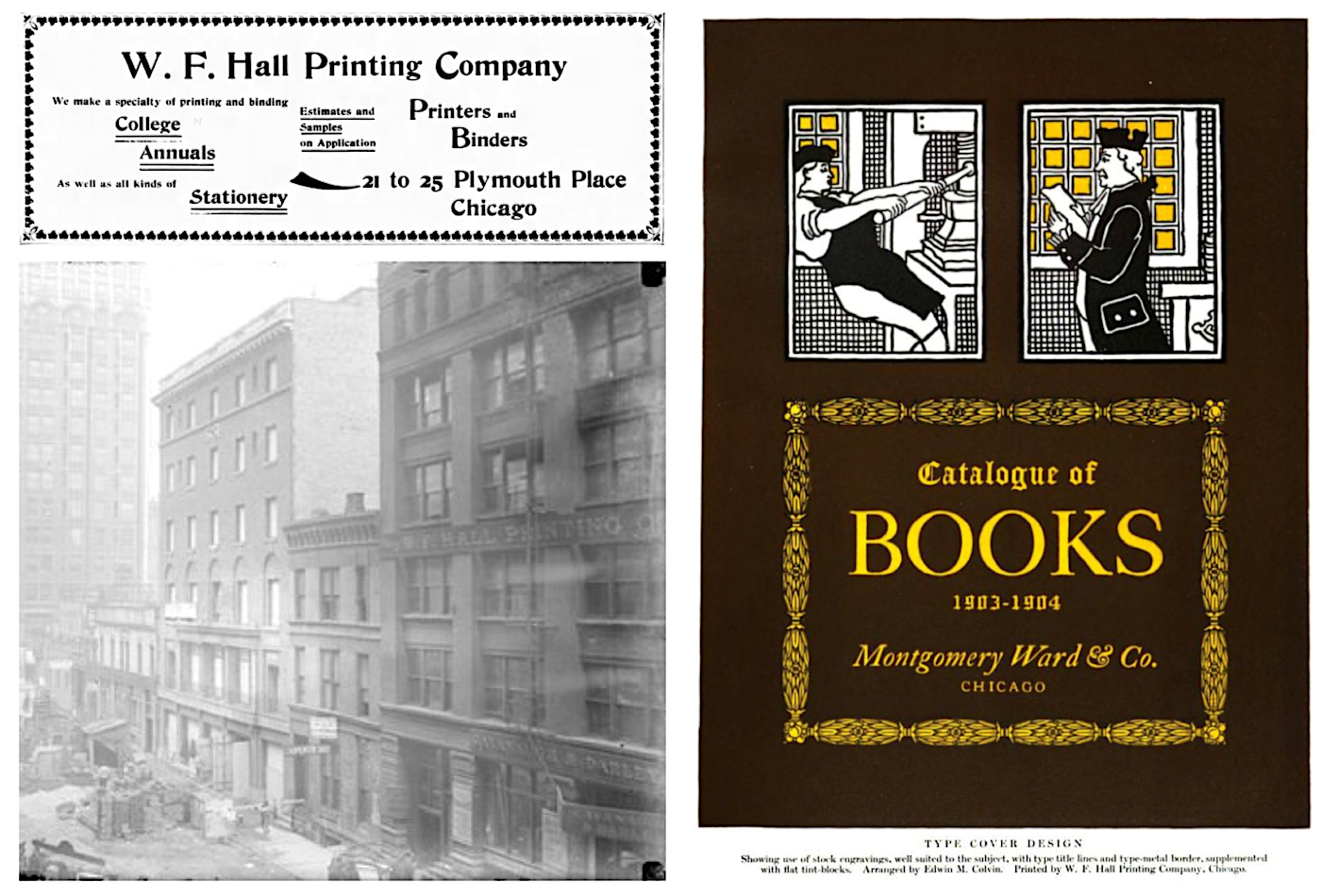

Between 1888 and 1892, Hall formed a partnership with another young, upstart printer named Norton H. Van Sicklen, who’d found some success producing early handbills and notices for the rapidly growing catalog giant Montgomery Ward & Co. Together, they established the Van Sicklen Printing Company in 1893. Just a year later, though, Van Sicklen decided his real passion was transportation—particularly the promotion of new bicycles and automobiles (he would later publish the periodicals Cycle Age and Motor Age). And so, in 1894, he left the printing enterprise to William, who re-christened it the W. F. Hall Printing Company. As part of the same turnover, elder brother John Hall was installed as vice president and director.

[Top Left: Early W. F. Hall advertisement from 1895. Bottom Left: Photograph of the original W. F. Hall building on Plymouth Court, between Van Buren and Jackson, facing north (25 Plymouth is roughly 327 S. Plymouth Ct. by today’s street numbering). Right: A Montgomery Ward book catalog arranged and printed by W. F. Hall Printing Co., 1903]

W. F. Hall’s first headquarters, at 21-25 Plymouth Place (aka Plymouth Court), was part of the budding ecosystem that would later come to be known as “Printer’s Row.” During Hall’s early years here, however, the couple of blocks north of Dearborn Station were known more for brothels and gambling than anything else. It wasn’t until R. R. Donnelley & Sons built its massive Lakeside Press Building in 1897 that the neighborhood’s reputation started to shift.

During W. F. Hall’s 15 years on Plymouth Court, it remained something of a second-tier operation compared to some of the more established printing houses like Donnelley (est. 1864) and M. A. Donohue & Co. (1861). Montgomery Ward’s big 1,000-page catalogs, for example, were still exclusively printed by Donnelley at the turn of the century, while Hall was tasked with handling Ward’s smaller flyers and inserts. Still, with a mailing list of 3 million households, these odd jobs could prove extremely profitable, especially as W. F. Hall began utilizing cheaper, lightweight paper to keep down costs on the front end.

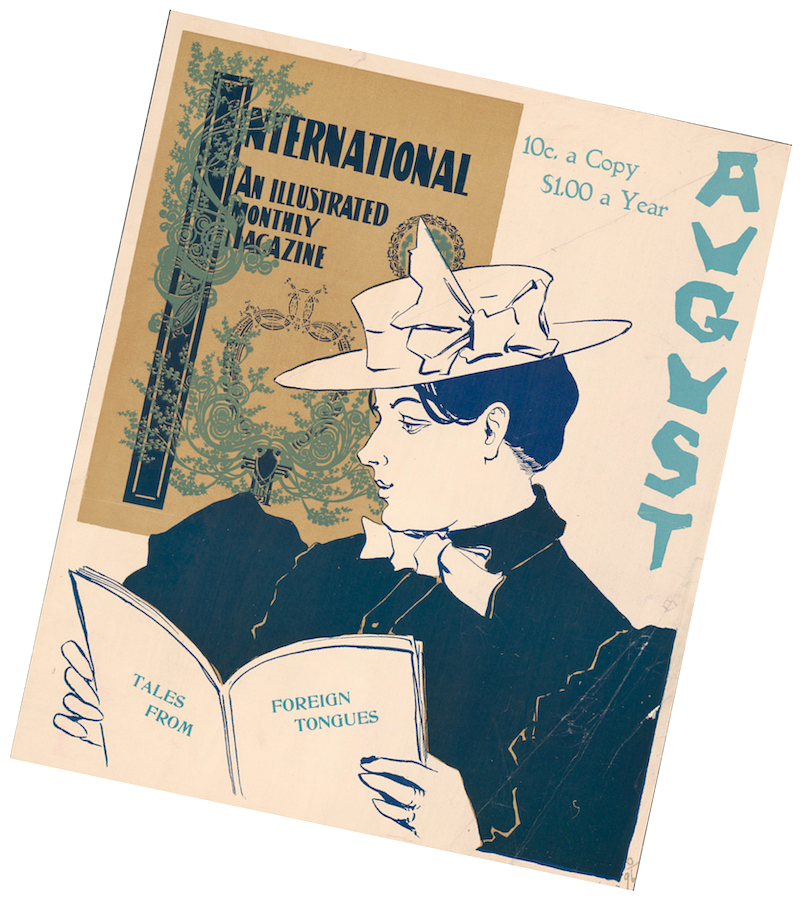

Almost from its inception, the Hall plant had little involvement with leather-bound novels and academic books; its bread and butter were mainstream magazines (including style rags such as The International and an early version of Vanity Fair) and sales materials. It was all “disposable reading,” some might say, but the kind that led to lucrative, long-term contracts with publishers and wholesalers. The industry was taking note.

Almost from its inception, the Hall plant had little involvement with leather-bound novels and academic books; its bread and butter were mainstream magazines (including style rags such as The International and an early version of Vanity Fair) and sales materials. It was all “disposable reading,” some might say, but the kind that led to lucrative, long-term contracts with publishers and wholesalers. The industry was taking note.

“W. F. Hall, still a young man, has been the dominant spirit in the upbuilding of a large and flourishing printing business within a dozen years, and is at the head of one of the most finely organized concerns in the West,” Walden’s Stationer & Printer reported in 1905.

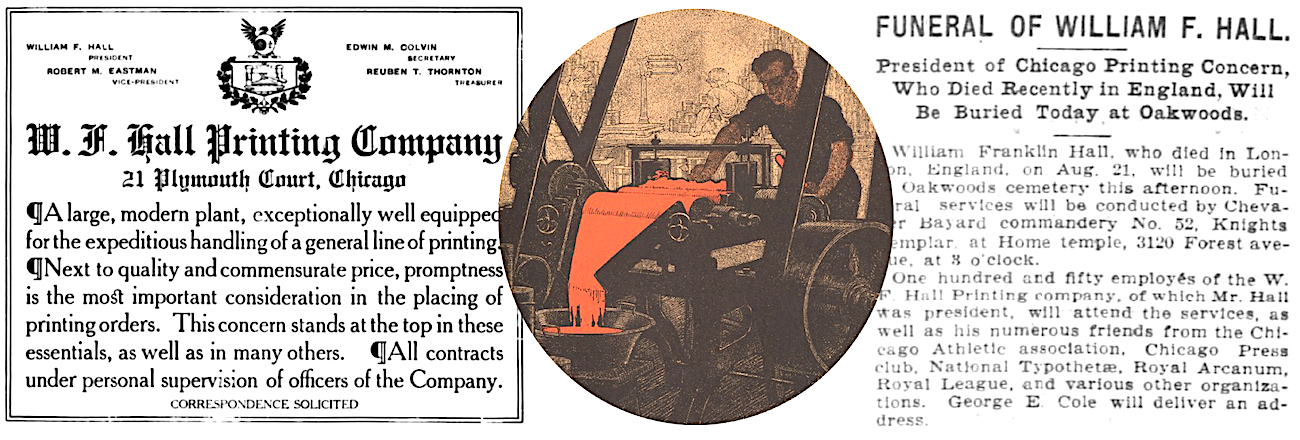

Finally, in the spring of 1908, the company had outgrown its Printer’s Row digs, and announced a move to a larger, seven-story facility at the northeast corner of West Superior and Kingsbury Street. That building was still under construction when William F. Hall informed his employees that he would be taking a leave of absence due to ill health—whether he knew it yet at the time, reports later indicated he had contracted Bright’s Disease (known today as nephritis).

That summer, William and his wife Jessie traveled to England with hopes that the experience would improve his condition. Instead, on August 21, 1908, Hall died in London from paralysis brought on by the disease. He was only 46. At his subsequent funeral in Chicago, 150 employees of his company attended the service, “as well as his numerous friends from the Chicago Athletic Association, Chicago Press Club, National Typothetae, Royal Arcanum, Royal League, and various other organizations.”

[Left: W. F. Hall ad from 1906. Center: Illustration of print industry worker from 1909 edition of the Inland Printer. Right: 1908 Tribune notice of the funeral of William F. Hall]

II. Eastman & Colvin

“Since Gutenberg invented printing at Mentz about 1450, the brains of every generation have done their utmost to make improvements, until today a trip through the great home of the W. F. Hall Printing Company shows the perfection and almost human instinct of every improved device intended to do the job better and save time and possibly considerable money in labor.” —Inter Ocean newspaper, 1912

Without question, the W. F. Hall Printing Company experienced its greatest success after the death of its namesake, but that shouldn’t be seen as any knock against William Hall himself. He had started the ball rolling, and the business partners with whom he’d aligned himself were the same men who carried forward his vision.

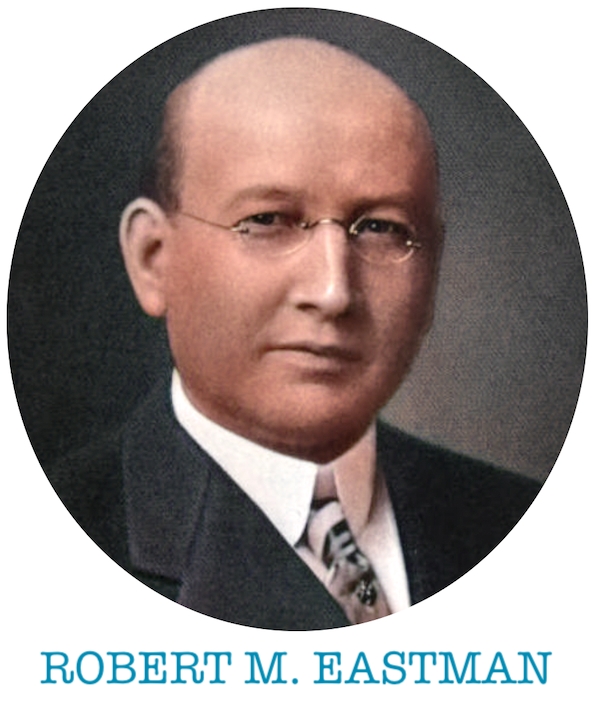

Chief among these figures were Robert M. Eastman (b. 1869) and Edwin M. Colvin (b. 1867), who had long served as Hall’s vice president and secretary, respectively, and who joined forces to purchase the business after their boss’s death in 1908. Now, with Eastman as president, Colvin as VP, and Reuben M. Thornton as secretary, this young but highly experienced crew entered the 1910s with a new determination to see whether supply could meet demand in a country that was now positively gaga for roll-up-able reading material.

“Everywhere is hum and activity,” the Inter Ocean reported after a visit to the West Superior Street plant in 1912. “This concern is printing an average of 100 tons of paper daily in its rotary press room, besides operating over a score of flat bed presses above. It binds close to 200,000 books daily in its pamphlet department and in the magazine bindery 50,000 standard-size magazines per day. . . . Ordinarily the handling of such large rolls of paper is cumbersome and awkward work, and yet the W. F. Hall Printing Company has devices which make the task absurdly easy.”

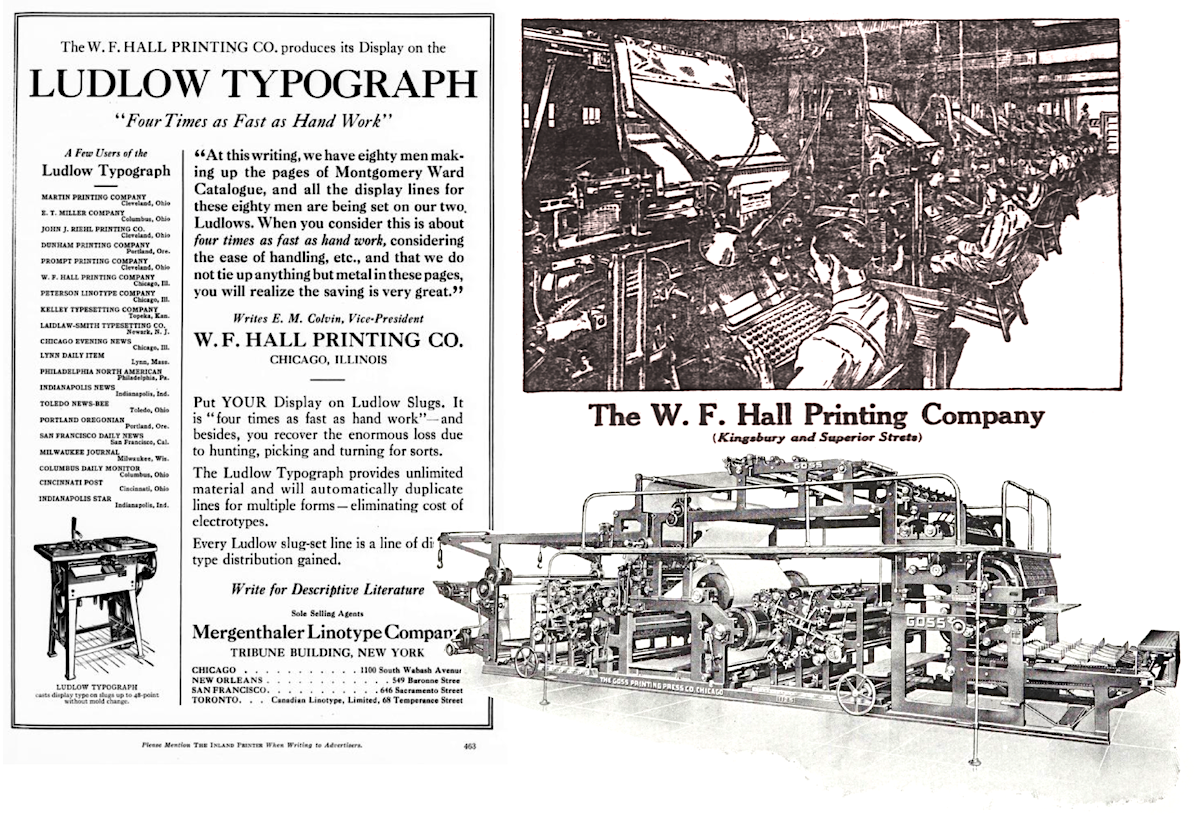

[Left: 1917 ad for the Ludlow Typograph machine, including a quote from Hall vice president Edwin Colvin about the use of the machine in the Hall plant. Top Right: Illustration of Hall’s linotype department from the Inter Ocean, 1910. Bottom Right: A special Goss 80-pgae halftone Magazine Printing Press (also Made in Chicago) that was used in the Hall plant in the late 1910s and ’20s]

Without question, Hall’s explosive growth was dependent on a symbiotic relationship with new electric press and type-setting technology, as the factory was stacked with highly efficient machines that demolished old 19th century limitations on productivity and cost-efficiency.

“We have eighty men making up the pages of the Montgomery Ward Catalogue,” Hall vice president Edwin Colvin said in a 1917 interview, “and all the display lines for these eighty men are being set on our two Ludlow typographs. When you consider this is about four times as fast as hand work, considering the ease of handling, etc., and that we do not tie up anything but metal in these pages, you will realize the saving is very great.”

Many of the big names in print machines were Chicago based, as well, including the Goss Printing Press Co., which custom-built and installed four 80-page halftone magazine presses for W. F. Hall during this same period.

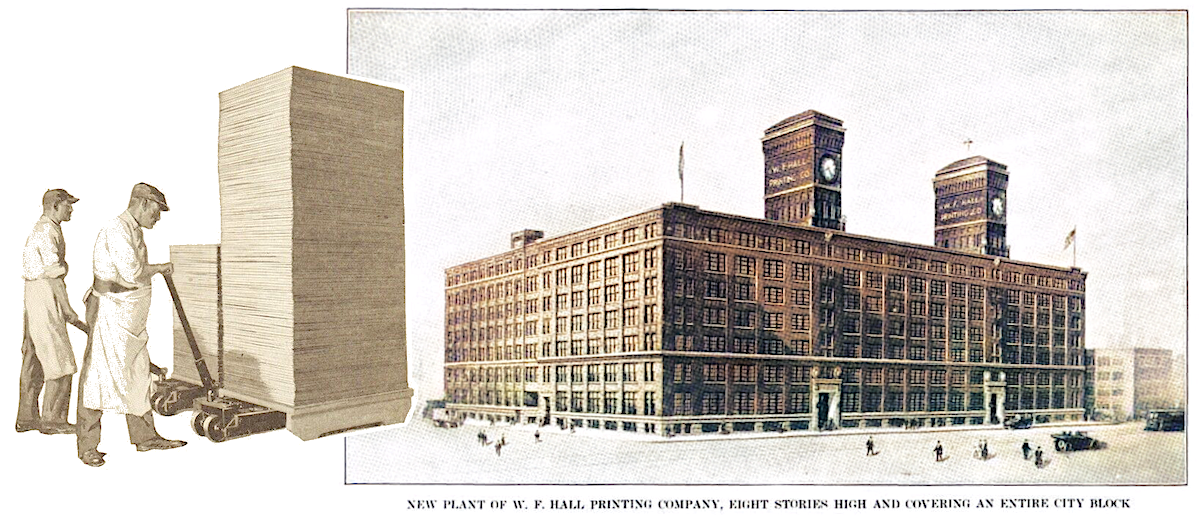

[Left: Illustration of workers using a Stuebing Lift Truck to move huge stacks of paper at the W. F. Hall plant, 1921. Right: Illustration of the expanded Hall factory at Kingsbury and Superior, 1918]

Despite all this miraculous automation, the head-spinning demand for new materials still required plenty of human hands and physical real estate. By 1918, the Hall complex had already been expanded three times, now taking up a whole city block from Kingsbury to Townsend Street, totaling about 8 acres of floor space. It was “an organization unsurpassed in resources, facilities and equipment,” according to the Western Trade Journal, and “the world’s largest plant devoted exclusively to the production of catalogs and magazines,” as assessed in an issue of Ben Franklin Monthly. The plant employed upwards of 2,000 men and women, many of whom were identified as “expert artisans in the printing and binding trades.”

To better serve a working community of that size, especially in the wake of a world war and the Spanish Flu epidemic, Hall’s bindery superintendent Anna V. Harris—one of the printing industry’s few female managers—proposed the creation of a welfare organization within the company, which she called the Mutual Benefit Association. Harris would remain in charge of the “MBA” until her death in 1942, sacrificing much of her personal time to visit ill employees and send care packages to team members in the armed forces.

To better serve a working community of that size, especially in the wake of a world war and the Spanish Flu epidemic, Hall’s bindery superintendent Anna V. Harris—one of the printing industry’s few female managers—proposed the creation of a welfare organization within the company, which she called the Mutual Benefit Association. Harris would remain in charge of the “MBA” until her death in 1942, sacrificing much of her personal time to visit ill employees and send care packages to team members in the armed forces.

Heading into 1920s, W. F. Hall’s growing army of workers now produced “at least twelve national publications, whose combined monthly circulation is nearly 4,000,000, and print catalogs each year to the number of 15,000,000.” Among these titles were some of the best-known Chicago-originated magazines—Popular Mechanics, Red Book, Mother’s, Factory, and Photoplay among them.

Notably, Photoplay was owned and published by Eastman and Colvin themselves, as they’d astutely purchased it when it was a middling movie pamphlet in the early 1910s. By the 1920s, Photoplay had become a leading resource for gossipy news on cinema and celebrities, essentially setting the template for every celeb-centric rag that followed it in the 20th century.

[The influential cinema magazine Photoplay was printed by W. F. Hall from roughly 1915 to 1935, then moved to Hall’s subsidiary, the Art Color Printing Company in New Jersey, during the “Golden Age” of Hollywood. The magazine was owned for over a decade by W. F. Hall’s own top executives, Robert Eastman and Edwin Colvin]

III. “Creative Art and Mighty Industry”

By 1925, W. F. Hall had no more room to expand at its current location and was forced to make its second major migration in company history. Maybe “forced” isn’t the right word. The company had just enjoyed its 30th consecutive profitable year. Growth and success seemed downright preordained. In any case, Hall’s third and ultimately final Chicago headquarters would take them out to the northwest side, where the architectural firm of Weiss and Niestadt built them a series of interconnected buildings (one and two-story) stretching across nearly 15 acres of land along Kilpatrick and Diversey Avenue.

It was promoted as the world’s largest printing plant under one roof, and as the Chicago Reader recounted in a 1988 retrospective, “the pressroom floors were made of creosoted wood and rested on a concrete slab over a sand cushion; they were ‘of ample strength to receive the largest printing presses in the world.’ There were 969 cylinder and 132 rotary presses. Skylights in the saw-toothed roof filled the pressrooms with sun, and the system of electric lights on the 35-foot-high ceilings supposedly cut shadows so well that ‘eyestrain and the resulting fatigue have been eliminated.’ Two heavy-duty hydraulic elevators, two cranes able to lift five tons, and three 500-horsepower boilers also served the plant—state of the art for the period.”

It was promoted as the world’s largest printing plant under one roof, and as the Chicago Reader recounted in a 1988 retrospective, “the pressroom floors were made of creosoted wood and rested on a concrete slab over a sand cushion; they were ‘of ample strength to receive the largest printing presses in the world.’ There were 969 cylinder and 132 rotary presses. Skylights in the saw-toothed roof filled the pressrooms with sun, and the system of electric lights on the 35-foot-high ceilings supposedly cut shadows so well that ‘eyestrain and the resulting fatigue have been eliminated.’ Two heavy-duty hydraulic elevators, two cranes able to lift five tons, and three 500-horsepower boilers also served the plant—state of the art for the period.”

When the cornerstone was laid on the new building, vice president Edwin Colvin made a speech to mark the occasion, titled “Past, Present, Future,” a written copy of which was then placed inside the stone in a time capsule. We’re not sure if that capsule was ever recovered, but thanks to the Inland Printer, we know what Colvin wanted future observers to know about the W. F. Hall Company in its 1920s incarnation.

“We are assembled here this day for the purpose of dedicating a wonderful building to one of the oldest of crafts, that of printing,” Colvin told the employees and press gathered on December 11, 1924.

“Yesteryear, as time is reckoned by geologists, the blue waters of Lake Michigan rolled over the spot where we now stand, and yesterday, by the same reckoning, the North American Indian stalked his prey through the tall grasses of endless prairies. Likewise, tomorrow, some of our descendants now living will congregate here and contemplate what may seem to them our puny efforts, but will without doubt regard this site as the geological center of the greatest city of the world.

[Top Left and Right: Views above and around the new W. F. Hall plant in 1925. Bottom Left: Photo of “the old Rotary Gang,” outside the factory, circa late 1920s or 1930s. The men, as identified in an issue “House Dope” years later, are “Plano, H. Michaels, Joe Marek, E. Thompson, C. Fleeger, J. La Buda, Emmerling, E. Ralstab, and J. Kelly (the latter lost overseas)”]

“We are proud to have been among those pioneers who were instrumental in bringing printing out of the chaos of struggling art into the realm of creative art and mighty industry. In less than two decades we have built one of the world’s greatest institutions devoted to the production of commercial literature, and we owe our success to the loyalty of our employees, the confidence of the people to whom we sell, and the integrity of people from whom we buy.

“. . . You of the future will take your motive power and much of your food from the air; you will take your heat from the depths of the earth; a single revolution of your press, whether photographic or electrical, will imprint its kiss upon the virgin surface of thousands of sheets of paper instead of one; your homes will be widely separated from your activities—twenty-five, fifty, one hundred miles—yet you will go to and fro in fractions of an hour; you will be in close communication with the planets; from your easy chair you will view the entire surface of the earth—icy wastes, mountains, forests, green fields and witching sea—

“. . . You of the future will take your motive power and much of your food from the air; you will take your heat from the depths of the earth; a single revolution of your press, whether photographic or electrical, will imprint its kiss upon the virgin surface of thousands of sheets of paper instead of one; your homes will be widely separated from your activities—twenty-five, fifty, one hundred miles—yet you will go to and fro in fractions of an hour; you will be in close communication with the planets; from your easy chair you will view the entire surface of the earth—icy wastes, mountains, forests, green fields and witching sea—

“But you will be no more abreast of the times than we of the present—you will be simply living in that era when these things shall have come to pass because of the restlessness of man.”

Edwin Colvin died just 18 months after this speech, in May of 1926, aged 59. As with the loss of William Hall, though, there was no slowing down the “restlessness of man” where it concerned the ambitions of the Hall company.

Between 1926 and 1927, the firm acquired the Chicago Rotoprint Company and the Edward Langer Printing Co. of New York, and was now producing over 350 million catalogs and magazines annually, including the hefty sales books of both Ward’s and Sears, as well as Albert Pick, Spiegel, and Gimbel Bros. At the peak of catalog season, the workforce in Chicago ballooned to over 4,000, only trimming down to a small village of 1,500 in the slowest months.

[Left: A group of female catalog inspectors outside the W. F. Hall plant, circa 1930. Identified 4th, 5th , and 6th from the left are Lillian Gloss, Rose Chudzik, and Bert Pardo. Right: Pages from a Spiegel, May, Stern & Co. catalog, 1930s]

Even into the 1930s, when financial setbacks were the general expectation, W. F. Hall steamrolled ahead, acquiring the Art Color Printing Co. of New Jersey in 1931 and reaching a 40th consecutive profitable year in 1933—despite the deaths of chairman Robert Eastman and vice president M. E. Franklin. New company chairman Frederick Secord had been a director with the firm for 20 years, and helped maintain stability at the top, even as the presidency changed hands from Frank Warren to Hadar Ortman to Alfred Geiger in the span of a few years in the mid ‘30s.

While the Great Depression never derailed W. F. Hall, Secord and Geiger faced no shortage of unique challenges during their tenures, starting with labor strikes at the Chicago plant in 1937, then the breakout of World War II a few years later.

[Left: W. F. Hall ad from 1934 encouraging companies to re-invest in magazine advertising during the Depression. Top Right: Hall chairman Frederick Secord (left) greets company president Alfred Geiger, with employee Dorothy Frangiamore in between them. Bottom Right: A W. F. Hall “Hall Mark of Progress” logo from the 1930s and some ephemera with company letterhead.]

IV. War Correspondence

“Every piece of government printing has a direct connection with the war effort. Our fighting men have reached the high level of efficiency which brought about our military successes because of the printed word which directed their efforts in the use of the tools of war. . . . We can feel we are invisible riders in raiding planes over enemy targets tonight.” —address to W. F. Hall plant personnel by Hon. A. E. Geigenback, Public Printer of the U.S., 1945.

During World War II, W. F. Hall continued to print many of its commercial publications, but material shortages and the loss of many workers to overseas service demanded major adaptations, as did new defense contracts, which required the mass production of “army field manuals, selective service questionnaires, and instruction books for the Civilian Defense and Price Administration offices.”

During World War II, W. F. Hall continued to print many of its commercial publications, but material shortages and the loss of many workers to overseas service demanded major adaptations, as did new defense contracts, which required the mass production of “army field manuals, selective service questionnaires, and instruction books for the Civilian Defense and Price Administration offices.”

Produced in much smaller numbers—but of immeasurable value to Hall employees—was the company’s in-house magazine, known by the amusing title “House Dope.” Serving the employees of Hall as well as its major subsidiaries the Chicago Rotoprint Co., the Central Typesetting and Electrotyping Co., and the Art Color Printing Co., House Dope not only covered the weddings, births, and sports club successes of the various departments; it served the important function of connecting workers on the homefront with their cohorts fighting in the war, and vice versa.

Soldiers would receive care packages from W. F. Hall’s Mutual Benefit Association, including the latest issue of House Dope, and would then write back to the office in Chicago, where their letters would be printed in the next edition.

“I have received your Christmas box and was very happy indeed,” Private Anthony Saras wrote just weeks after Pearl Harbor. “It made me feel pretty good to know that you are thinking of us. It’s things like that make a soldier’s not so bright life a little brighter. To the boys in the shipping room, and to all Hall employees, a Happy and Victorious New Year!”

Pfc David Davies, of Hall’s Plate Overly Department, was hit by a mortar shell during the invasion of France in 1944, and wrote back from a hospital bed a day after receiving his Purple Heart. “Say hello to McKenna and McCarthy in the Press Room. See you one of these days. I’m the old veteran of the joint. Was up there [on the front] 52 days and got to thinking they’d never get me. Hello to the Stereotype gang!”

Some Hall employees were able to utilize their professional skills for the war effort, including Lloyd “Shorty” Condor, who did offset printing with a reproduction platoon and traveled through a liberated France in 1945. After visiting Paris, he wrote back that it was “quite a city. But give me Chicago in the good old U.S.A! All I want is to get back there and stay.”

Sgt. F. D. Lochner, working with military intelligence, also stopped through Paris and visited two large printing plants in the city. “Sure felt good to get back into the printing environment again,” he wrote to House Dope. “I saw Time, Newsweek, Yank, and about 20 French magazines being run off. Looked about for new ideas, but it seems we are about 25 years ahead of these people.”

This was probably a fair assessment, even for a patriotic yankee in uniform. And yet, back in Chicago, W. F. Hall’s directors remained ever vigilant when it came to new technology, new methods, and better ideas.

“The company continues to look ahead and plan for post-war development insofar as possible,” president Geiger told the Tribune in 1943. “Studies are being made for post-war markets and possible new types of books and other literature to print, so that the company may be in the best position to create new jobs and increase the production of large volume printing matter.”

Those “new jobs” also included guaranteed spots for all returning soldiers formerly on the Hall payroll, as well as open invitations to the men and women who’d joined the factory force in their absence.

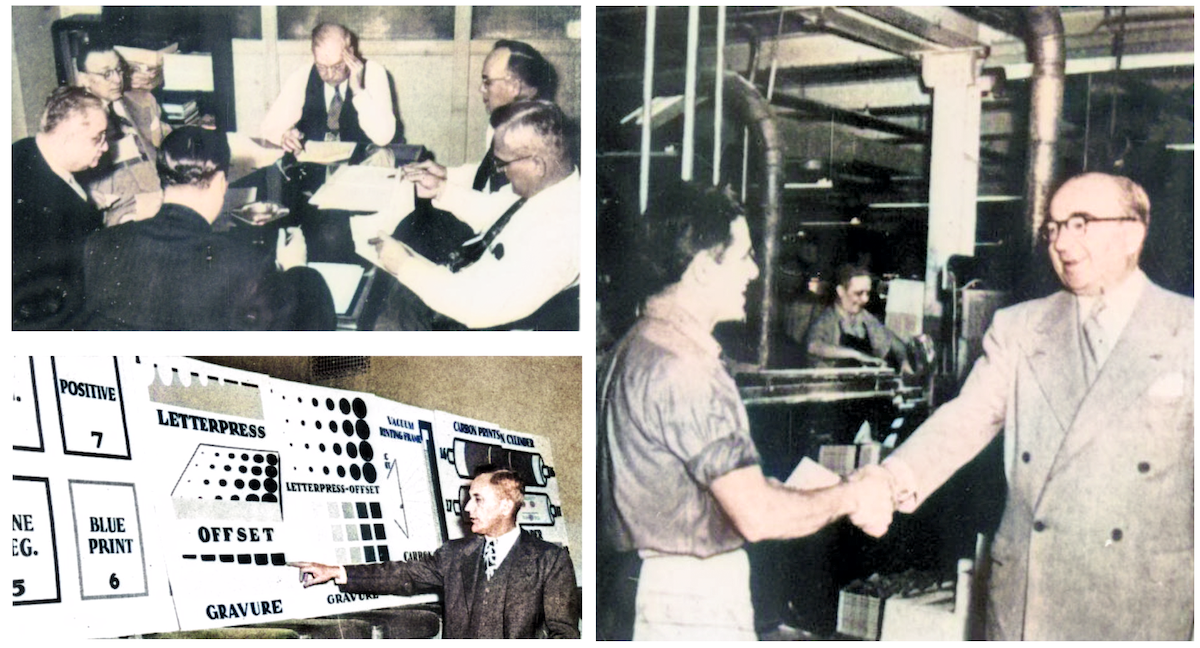

[W.F. Hall workers pictured in “House Dope” during the war years. Top Left: W.F. Hall president Alfred Geiger with eight veteran employees: (back row) Thomas Walsh, John O. Peterson, Buel Johnson, and Gus Baier, (front row) Ella McQuinn, Margaret Neeson, May Flaherty, and Kathleen M. Smith. Bottom Left: “Miss Grant,” described as the “Pin-Up Girl” of the Montgomery Ward line’s night shift. Top Right: Geiger is presented a certificate of merit by A. E. Geigenback, Public Printer of the U.S. Bottom Right: Members of the company bowling league, representing the Chicago Rotoprint 2nd Shift and Central Typesetting’s No. 2 team]

V. Hauls at Hall

After the war, W. F. Hall did indeed bring all hands on deck as its Diversey Avenue operation grew to increasingly precarious degrees of immensity and complexity. The company now employed 3,000 regular workers under its own tent, plus another 3,000 within its sister divisions: Chicago Rotoprint and Central Typesetting (which were housed in the same complex) and Art Color Printing in Dunellen, New Jersey.

This substantial manpower was combined with the latest in every type of machinery for printing, typesetting, cutting, folding, binding, inserting, stitching, packaging, and shipping.

In 1951, a three-story addition was made to the plant specifically for the “mailing and bundling department.” There, employees of the Chicago Post Office had their own regular shifts on site, simply so Hall could send out its sacks of magazines on trucks or box cars without the added nuisance of going through the Main Post Office first.

“The timing of performance in the shipping room,” according to one assessment by the Inland Printer, was “as smooth as Tinker to Evers to Chance”—a reference to the Chicago Cubs’ slick-fielding double-play combination from a generation prior.

Nothing better exemplified the weirdly efficient ridiculousness of the W. F. Hall plant, however, than the private railroad the company operated around its complex—“complete with a diesel locomotive, 6,000 feet of track, several freight cars, and crews for the first and second shifts,” according to a 1955 profile in Book Production magazine. “The railroad handles about 10,000 cars in and out of the yards during the year. Besides items such as new machinery, glue, coal and oil, about 200,000 rolls of paper and 18,000 skids of flat stock are unloaded.”

Such big numbers begat even bigger ones: 595 million magazines produced per year by 1954 (that’s 1,132 issues per minute), along with 315 million big mail-order catalogs and another 300 million smaller catalogs or flyers.

[Top Left: Photo and headline from 1949 Inland Printer article. Bottom Left: W. F. Hall’s private railroad, pictured in 1955. Top Right: Magazines being moved from a Hall gathering machine into a tumbler trimmer, 1955. Bottom Right: A new ink transfer system is inspected by Hall managers Adam Moses (VP of Engineering), Carl Braun (VP of Sales), Arthur Knol (VP of Manufacturing), and John Maxwell (Superintendent of Rotary Dept.), 1955]

A good chunk of that catalog material was churned out during W. F. Hall’s two “peak seasons” (June-July for fall and winter catalogs and December-January for summer editions), during which “about 300 additional women employees are hired to handle hand operations such as inserting, separating, and swatching.

“Many women are recruited from the neighborhood,” according to Book Production. “They look forward to the seasonal employment. One woman, for example, was hired at Hall’s for the first time on July 19, 1937, and has worked for 26 different seasons in the last 18 years.”

Any Hall employee—be it a veteran department head or one of those seasonal catalog gals—was welcomed to contribute to the company’s success not just with their physical labor, but with their brains, as well. Around 1948, a factory-wide “Suggestion System” was implemented, through which any employee could register a formal suggestion for an improvement in the operation of any department. A committee of W. F. Hall higher-ups would then review the entries weekly and hand out cash rewards, weighed by perceived merit and potential cost-saving value—to each suggestor.

Any Hall employee—be it a veteran department head or one of those seasonal catalog gals—was welcomed to contribute to the company’s success not just with their physical labor, but with their brains, as well. Around 1948, a factory-wide “Suggestion System” was implemented, through which any employee could register a formal suggestion for an improvement in the operation of any department. A committee of W. F. Hall higher-ups would then review the entries weekly and hand out cash rewards, weighed by perceived merit and potential cost-saving value—to each suggestor.

“More fully than ever before, we realized what a vast amount of experience and know-how we had within our organization,” Charles Braun, VP of Sales, wrote in a 1951 article. “We knew if that experience could be tapped so that it could be made better available, we would have all that was necessary for further great improvement in our productive activities.”

Many of the suggestions adopted in the early years of the program helped W. F. Hall improve the methodology behind its newest line of products: “pocket sized” paperback books. The company had dipped its toe into this upstart market in 1941, and was already an industry leader by the 1950s, eventually inking deals with new mass-market book publishers Bantam (est. 1945) and New American Library (est. 1948).

[Top Left: Meeting of the W. F. Hall Suggestion Committee, 1951 (clockwise starting with man with back to camera) – Allen Reiffman, Charles Oliff, Carl Braun, William Wendel, Edward Muhl, and George Preucil. Bottom Left: George Preucil, part of the Chicago Rotoprint division, presents a demonstration on intaglio-gravure printing, 1949. Right: President Alfred Geiger presents a $1350 award from the Suggestion Committee to suggestor Richard Foerster of the bindery department, 1951]

“In much the same way that movable type made possible literature for thousands,” Book Production noted in 1955, “the pocket-size book offers educational opportunities to millions.”

That’s a lovely sentiment, but as the 1950s carried into the ‘60s, W. F. Hall’s book department (which produced 75% of the paperbacks in the country) was probably more associated with feeding America’s dime store genre obsessions—romance, Westerns, crime, science fiction, and fantasy stories—than classic lit or “educational” material. Even the aforementioned Warren Commission Report on the Assassination of President Kennedy (1964), for which Hall set a land speed record in mass printing, was arguably a shameless “whodunnit” as much as it was a serious government document.

This high-brow / low-brow dynamic was also apparent in Hall’s mid-century magazine line-up. It’s not so much that counter-culture men’s magazines like Esquire and Playboy were “beneath” the sophistication of Hall’s mainstream publications (i.e., Newsweek, Motor Trend, Woman’s Day, The Rotarian, etc.); in fact, they were often quite a bit classier when it came to political essays, celebrity interviews, and investigative journalism. The duality, as ever, was more about the pictures.

This high-brow / low-brow dynamic was also apparent in Hall’s mid-century magazine line-up. It’s not so much that counter-culture men’s magazines like Esquire and Playboy were “beneath” the sophistication of Hall’s mainstream publications (i.e., Newsweek, Motor Trend, Woman’s Day, The Rotarian, etc.); in fact, they were often quite a bit classier when it came to political essays, celebrity interviews, and investigative journalism. The duality, as ever, was more about the pictures.

Hugh Hefner couldn’t have built his Playboy empire without W. F. Hall, which printed the magazine (most of it, anyway) for its first 30 years. As a consequence of that long-running contract, more than a few men who grew up in the Cragin / Belmont Gardens / Kelvyn Park area of Chicago have fond memories of raiding the loading trucks outside the Hall plant, looking to swipe a “hot off the press” stack of Playboys. Some of those boys might have been in for a surprise, it should be noted. As an equal opportunity offender, W. F. Hall also took the first printing contract on Playgirl magazine in 1972.

Ebony and Jet, two pioneering African-American culture magazines published by Chicago’s Johnson Publishing Co., were also longtime Hall staples, and similarly provided a mix of the low brow (quack advertising, celeb gossip) and important social and political reporting, including Jet‘s important coverage of the race-based murder of Chicago teenager Emmett Till in 1955, and its many profiles on key figures in the Civil Rights movement. A 1968 issue of Jet published after the assassination of Martin Luther King is included in the Made In Chicago Museum collection.

[Left: Selection of 1960s Jet magazines, all printed by W. F. Hall. Right: Worker operating a cylinder press at the Hall plant, 1955.]

VI. Stop the Presses

Through the 1960s, W. F. Hall remained part of the “Big 3” of Chicago printing firms, along with Cuneo and R. R. Donnelley. Hall was also now the exclusive printer of all Montgomery Ward catalogs, a $100 million deal critical to the firm’s ongoing success during this era.

Robert S. Knox, who succeeded the similarly named Arthur N. Knol as head of the company, seemed committed to Chicago, even as many other big manufacturers fled for the suburbs or further afield. He acquired additional local plants at 6630 W. Fullerton and 2441 N. Normandy Avenue and ultimately shut down the Art Color facility in New Jersey to consolidate more work around Hall’s Midwest hub.

Robert S. Knox, who succeeded the similarly named Arthur N. Knol as head of the company, seemed committed to Chicago, even as many other big manufacturers fled for the suburbs or further afield. He acquired additional local plants at 6630 W. Fullerton and 2441 N. Normandy Avenue and ultimately shut down the Art Color facility in New Jersey to consolidate more work around Hall’s Midwest hub.

In the 1970s, though, the situation quickly changed. The cost of maintaining the 50 year-old Hall plant and paying its skilled, unionized workforce was finally pushing Knox and the rest of the company leadership to ponder other options. Despite continuing profits year after year, the “restlessness” that had defined the business since its inception led to some bold, perhaps ill-advised decisions.

In 1977, W. F. Hall managed to win the contract to print National Geographic magazine, a long-time jewel in the crown of R. R. Donnelley (Donnelley, it should be noted, was still doing about 4-times the annual sales of Hall at this point in time). The deal, however, involved building a whole new facility to handle the Nat Geo account—not in Chicago, but on the much cheaper real estate of Corinth, Mississippi. There, the iconic yellow-bordered travel magazines would now be printed on two giant, gravure presses each standing four feet tall and “half a football field long.” This was not a cheap undertaking, even with the trophy of a leading national magazine at the end of the rainbow.

[When W. F. Hall acquired the contract to print National Geographic in 1977, it further pushed the company’s move away from Chicago toward more affordable, modern plants in the southern states. Pictured above is a Hall plant in Dresden, Tennessee, as it looked in the ’70s – courtesy of Epstein Global.]

Suddenly, W. F. Hall needed to cut more costs to balance its books. More production was gradually moved to the budget-friendly southern states—Georgia, North Carolina, Tennessee—and more shares of the business were sold off to the famed Pritzker family of Chicago, owners of the Hyatt hotel chain. These developments set the stage for the announcement, in 1979, that W. F. Hall had been purchased by the Mobil Corporation—the oil giant that had already gobbled up Montgomery Ward—at the cost of about $50 million.

“This is one of the best things ever to happen to us,” Hall chairman Robert Knox said at the time. “This will enable Hall to grow much bigger and faster through the infusion of [Mobil] capital.”

Spoiler alert: this did not happen.

Instead, W. F. Hall was now firmly on course with its own destruction in the 1980s, beginning with the collapse of their longtime relationship with local boy Hugh Hefner and the Playboy printing contract. Some say the conservative executives at Mobil crushed the deal, not wanting to be associated with such perceived “sleaze.” Others say Hefner parted ways on his own accord when Hall started falling short on its deadlines.

Either way, Playboy was gone by 1985, and the knockout blow came that same year, when Montgomery Ward announced it would be discontinuing its big mail order catalog—a mainstay of W. F. Hall’s business going back 60+ years.

In the aftermath, Mobil wanted nothing further to do with the business, selling it off in pieces to the W.A. Krueger Company of Arizona and the Swiss printing firm Ringier A.G. The main Chicago plant swiftly shut its doors, erasing thousands of jobs and devastating the Cragin neighborhood. A final paperback printing facility on Normandy Avenue closed in 1987, representing the last vestiges of the business in Chicago.

[Left: A final look at the main W. F. Hall building at 4600 W. Diversey in 1985, just before its sale, closure, and demolition. Right: The northern end of the former Hall complex, seen here at Belmont and Knox Avenue in 2022, was cleared for a shopping center. Some of the original Hall and Rotoprint buildings were also kept and repurposed for “W. F. Halls Self Storage” (that name really needs an apostrophe) and the Klairmont Kollections auto museum.]

For several years after the Cragin plant closure, there were fierce battles within the community about what would become of the 60 year-old facilities. Many hoped they would be retained for manufacturing, but most buyers didn’t like the location or the layout of the buildings as viable for modern industry, leaving the issue in limbo.

Larry Klairmont of the Imperial Realty Company finally acquired the property in 1988, and ultimately demolished some parts of the complex for new retail space (most notably a Wal Mart and a strip mall called “Hall Plaza”), while renovating some of the other cavernous printing plant buildings for other potential new uses.

Klairmont—a World War II vet who’d first made his fortune in the laundry business—eventually developed the 100,000 square foot Rotoprint building from the northern end of the W. F. Hall complex (located at 3117 N. Knox Avenue) into a private museum and display space for his growing collection of classic automobiles. That museum, Klairmont Kollections, opened to the public in 2019, and in 2022 it welcomed the Made In Chicago Museum as one of its ongoing exhibits.

Klairmont—a World War II vet who’d first made his fortune in the laundry business—eventually developed the 100,000 square foot Rotoprint building from the northern end of the W. F. Hall complex (located at 3117 N. Knox Avenue) into a private museum and display space for his growing collection of classic automobiles. That museum, Klairmont Kollections, opened to the public in 2019, and in 2022 it welcomed the Made In Chicago Museum as one of its ongoing exhibits.

Naturally, within our Made In Chicago showcase at Klairmont, we have a special cabinet dedicated to the W. F. Hall Printing Company.

As Hall’s vice president Edwin Colvin predicted when he marked the opening of this building in 1924, we are no more abreast of the times today than he was 100 years ago. We are simply living in that era when new things have come to pass “because of the restlessness of man.”

[Top Left: Exterior of Klairmont Kollections, which utilizes a former W. F. Hall building at 3117 N. Knox Ave. Bottom Left: Made In Chicago Museum exhibit, which opened at Klairmont Kollections in 2022. Right: View at one small portion of Klairmont’s 300+ classic car collection.]

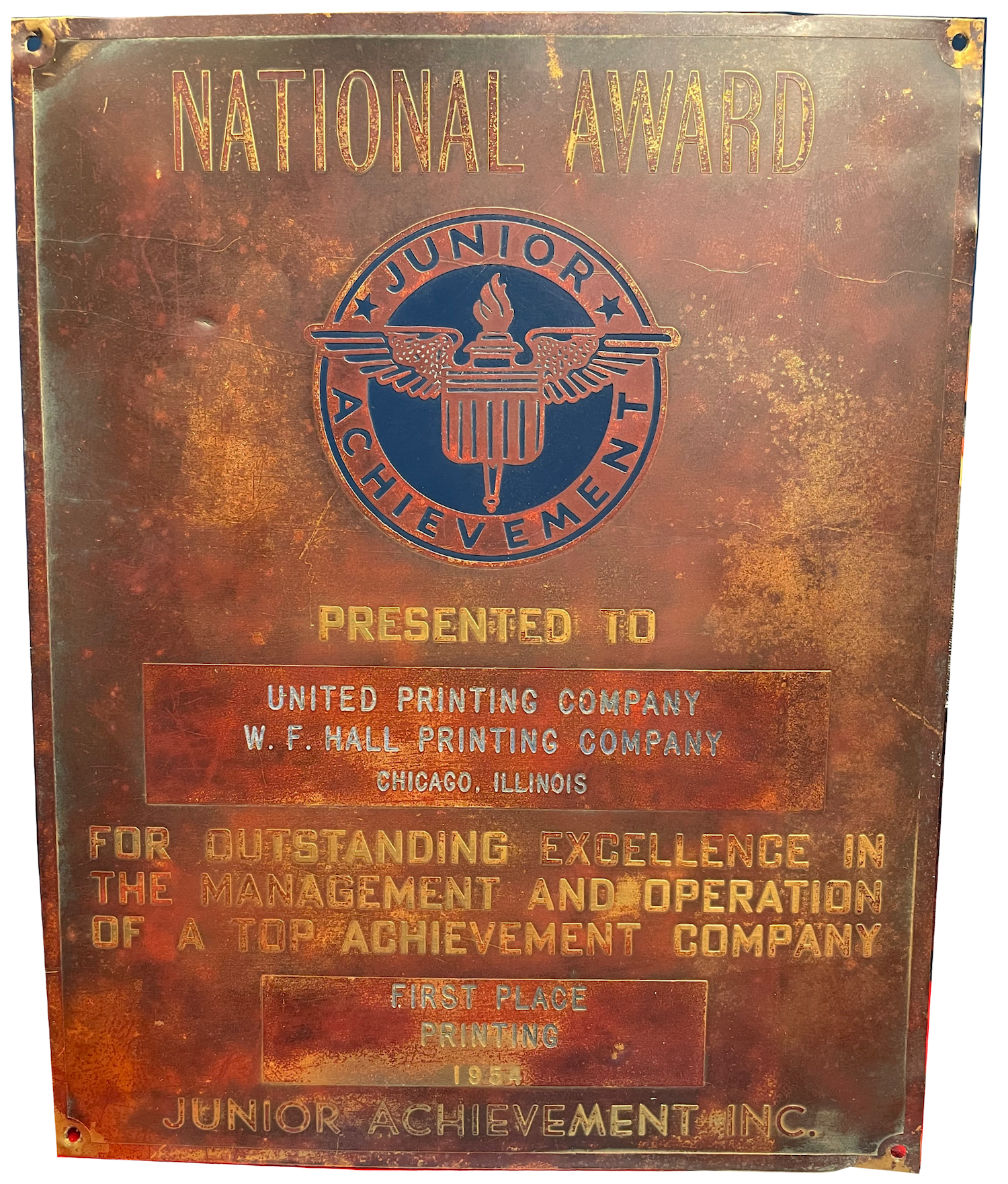

[This Junior Achievement plaque, awarded to W. F. Hall Printing in 1954, was recently found in the Klairmont Kollections building.]

Sources:

House Dope issues: Jan 1942, Sept-Oct 1944, March-April 1945, May-June-July 1945

“Staff of the W. F. Hall Printing Co.” – Walden’s Stationer and Printer, Jan 10, 1905

“Big Building is Planned” – Chicago Tribune, April 18, 1908

“William F. Hall” (obit) – Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette, Aug 23, 1908

“Funeral of William F. Hall” – Chicago Tribune, Sept 4, 1908

“Hall Printing Co.’s Business is Growing” – The Inter Ocean, Jan 1, 1912

Story of Chicago in Connection with the Printing Business, 1912

“The W. F. Hall Printing Company” – Manufacturing and Wholesale Industries of Chicago, Volume 2, 1918

“W. F. Hall Printing Company” – Ben Franklin Monthly, Jan 1919

“W. F. Hall Printing Company” – Press Club of Chicago Official Reference Book, 1922

“Start in June on $2,000,000 Printing Plant” – Chicago Tribune, May 18, 1924

“The New W. F. Hall Building” – The Inland Printer, April, 1925

“W. F. Hall Printing Company Five-Year Record” – Austin American, Dec 8, 1927

“Van Sicklen Motor Pioneer Dies in Chicago at 68” – Automotive Daily News, June 23, 1932

“Robert M. Eastman, Chairman of W. F. Hall Company, Dead” – The Inland Printer, Dec 1932

“W. F. Hall Printing Co.” – Hartford Courant, March 28, 1933

“Hall Printing Nets $701,523 in Fiscal Year” – Chicago Tribune, May 29, 1937

“Hall Printing Profits Slip in Fiscal Year” – Chicago Tribune, June 7, 1943

“Hall Printing Co. Solves the Smoke Problem” – Printing Equipment, March 1948

“How Materials Handling Problems are Solved at the W. F. Hall Printing Plant” – The Inland Printer, Nov 1949

“Suggestion System” – Printing Equipment, Dec 1951

“Chicago Home to Big Three of Printing Trade” – Chicago Tribune, Dec 16, 1951

“That’s Hall’s Brother!”(Parts 1-4) – Book Production magazine, Sept-Dec, 1955

Report of the Warren Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy, Bantam, 1964

“Robert S. Knox, 67, Chicago Printing Official” – Chicago Tribune, Oct 16, 1984

“W. F. Hall to Sell Chicago Plant” – Chicago Tribune, Sept 22, 1985

“W. F. Hall to Close Plant Here” – Chicago Tribune, May 19, 1987

“A Plant Dies In Cragin” – Chicago Reader, Jan 7, 1988

My dad, Milton Peterson, was Assistant Traffic Manager at Hall Printing. He retired on December 1, 1972. My brother, Tom, was a production scheduler there for many years and moved to Corinth, MS when the company opened their facility there. I worked in the Hall-Roto-Central credit union for a time right after graduating from high school.

Hi all, Name is Ray Mohyde. Working at Rotoprint was generational to my family. My grandfather Lawrence, his brother in law Ray Auney, my father Ray, his brother Larry Jr and finally me. Living in Harwood Heights a stop at Village bakery was necessary. My memories of Hall go back to when I was 4 years old. Worked there 74-84. Was an honor and privilege. My old boss Alan Nicolay just passed last week. Many preceeded him. Blessings to all.

I believe my grandfather worked for your company, pre 1947. May have been a custodian, my mother told me he died there. His name was John J Oswald.

My dad worked there for 45 years, retiring in 1985. Was proud to work there, and was the bindery superintendent! Some very interesting reading material, indeed!

My Dad (Bill) William H Quinn was a cylinder lock up craftsman for Hall Printing before computerized offset printing was invented. I was 5 or 6 years old and the time, and have fond memories of how proud Dad was to be a part of the Hall Printing Company. And after work he brought baked goods home from Dinkel’s Bakery to share with the family. He often talked about the challenges of aligning the colors to make beautiful colored photos on printed paper.

I went to work for WF Halls in 1977 right out of high school .

My connection to WF Hall started in joining their sales force for magazine printing clients. I enjoyed the time capsule preserving the history of a vital company. My arrival coincided with the Movil Oil buying Montgomery Ward business because our new printing plant in Augusta Georgia was contingent upon signing our contract. Mobil chose to buy WF Hall to simplify (they thought) the complete circle of acquiring the retail company.

It was my personal honor to have known and worked with Bob Knox.

Thanks for a wonderful, informative story. I grew up blocks from the W. F. Hall plant on Normandy. Part of it still stands, repurposed as a Home Depot. The building was originally occupied by Revere Copper & Brass during the war years, then by Western Electric who built a tall, curved concrete stand to test their radar units. Hall Printing’s rise and fall resembles so many other Chicago firms. Good to know Klairmont Kollections and MICM are putting the old space to good use.

My dad born in 1902 began as a fly boy at art color in Dunellin and became a printer. I have a photo of him at his press. Closing the plant took a toll on those folks and my family.