Museum Artifact: Menthol Pill Bottle, c. 1910s

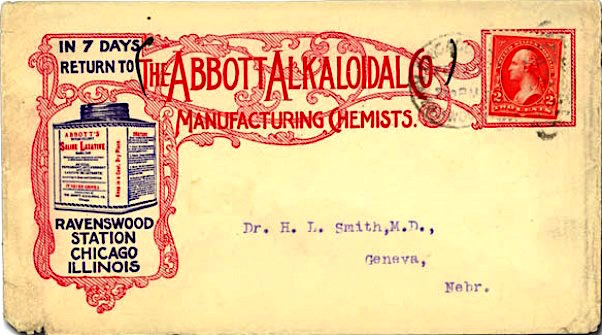

Made by: Abbott Labs / Abbott Alkaloidal Co., 4753 N. Ravenswood Ave., Chicago, IL [Ravenswood]

Established during the “Wild West” era of the pharmaceutical industry—when everybody and their brother seemed to have a cure-all potion to peddle—Chicago’s Abbott Alkaloidal Company managed to strike a unique, calculated balance between carnival-barker salesmanship and scientific legitimacy. As a result, even as hundreds of other early drug companies were vanquished during the quackery purges of the 20th century, Abbott managed to survive and thrive—overcoming no shortage of attacks and skepticism in the process.

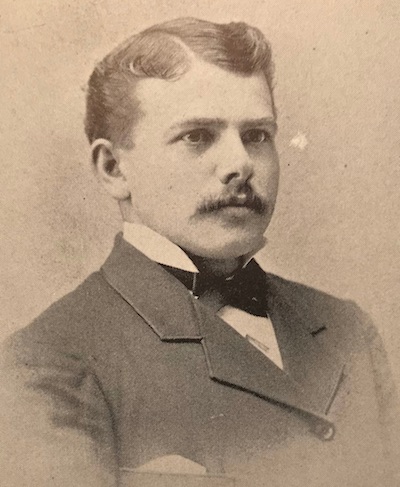

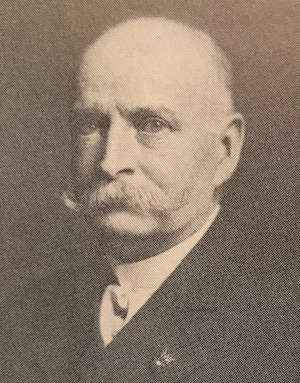

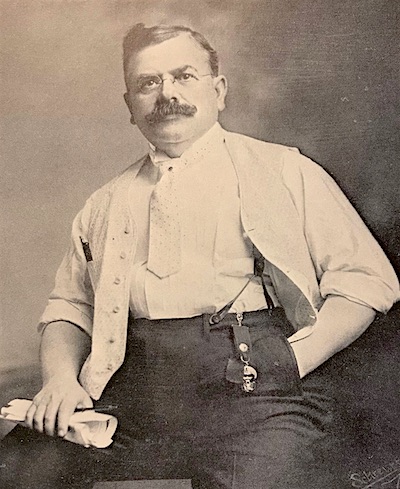

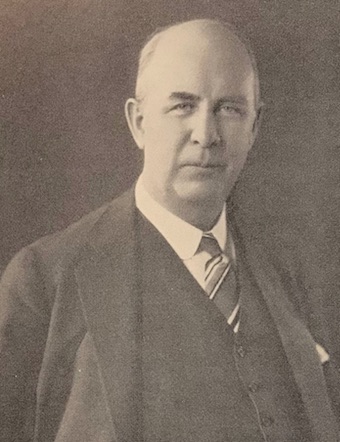

Today, Abbott Laboratories and its sister company AbbVie employ upwards of 90,000 people in over 150 countries, with profits topping $20 billion annually. And whether you perceive them as a great leader and innovator in life-saving medications, or emblematic of the evil rise of Big Pharma, one thing cannot be debated—the whole thing wouldn’t exist without the efforts of one small-time Chicago doctor in the 1890s; a stubborn and visionary fella named Wallace C. Abbott.

The Farm Boy

W. C. Abbott was born in Bridgewater, Vermont, in 1857—a thick-necked but progressive minded kid out of step with his immediate barnyard surroundings. Despite excelling in school, his father deemed young Wallace’s education complete by age 14, sending him to full-time work on the family farm. It was only the intervention of Abbott’s mother, Wealtha, that finally re-opened that door to higher learning more than five years later.

W. C. Abbott was born in Bridgewater, Vermont, in 1857—a thick-necked but progressive minded kid out of step with his immediate barnyard surroundings. Despite excelling in school, his father deemed young Wallace’s education complete by age 14, sending him to full-time work on the family farm. It was only the intervention of Abbott’s mother, Wealtha, that finally re-opened that door to higher learning more than five years later.

“Let the boy get his degree,” she told her husband. “He wants to be a doctor.”

Luther Abbott, grizzled New England farmer, finally gave in with a grunt and a nod.

Driven to catch up on lost time, Wallace Abbott went back to school in his 20s, enrolled in a couple local academies, then got into Dartmouth College at a cheetah’s pace. He eventually earned his medical degree from the University of Michigan at the age of 28, and got his first gig as a traveling physician’s assistant back home in Vermont immediately after. His life may have carried on in that trajectory if not for one of those always convenient twists of fate.

Who Ravens Wouldn’t?

A family friend of the Abbotts by the name of Fred C. Dodge—perhaps recognizing W. C.’s dissatisfaction in his current role—informed him of a possible job opportunity in the far western “frontier village” of Ravenswood, just north of Chicago. Dodge’s older brother, Dr. William C. Dodge, was Ravenswood’s primary physician and ran a pharmacy, as well, but he had fallen ill and wanted to sell the whole shebang—the practice and the drug store—to a worthy candidate for the special one-time-only discount price of $1,000.

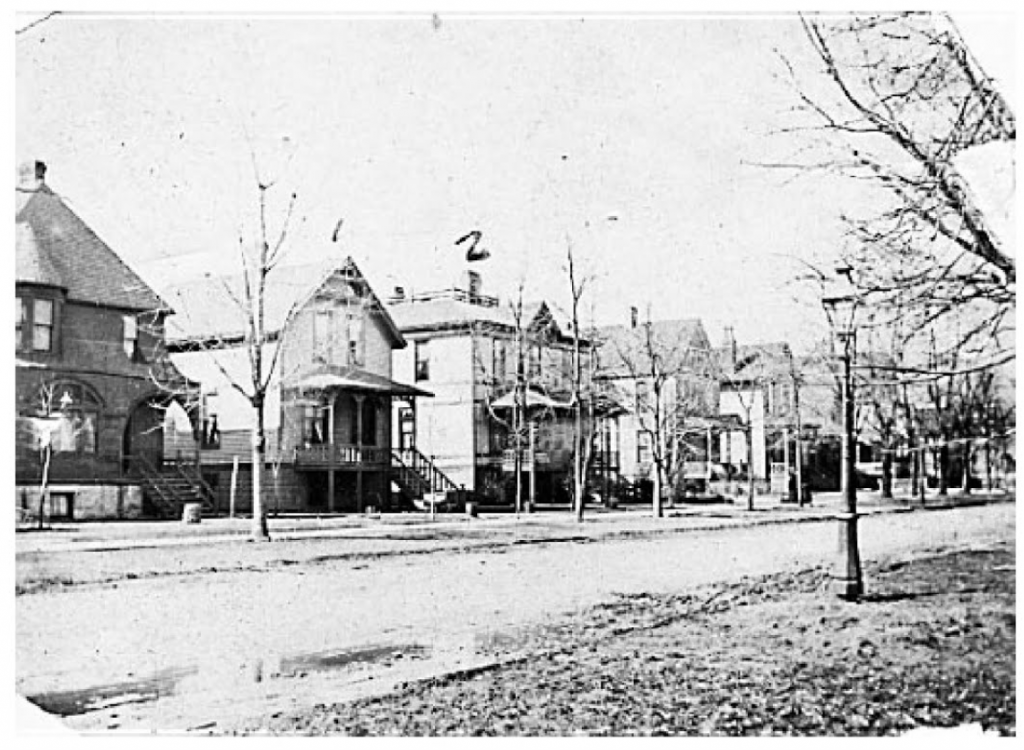

Young Dr. Abbott, like most recent medical students, had no money, but he did have an adventurous spirit. His college days in Ann Arbor had given him a taste for the Midwest, and an exploratory visit to Chicago and the Ravenswood offices of Dr. Dodge inspired him to scrounge together the loans necessary to grab the opportunity. By the summer of 1886, he had moved himself and his bride Clara into their new home in a two-room flat behind the People’s Drug Store on Ravenswood Avenue. [photo: Ravenswood, late 1800s]

Young Dr. Abbott, like most recent medical students, had no money, but he did have an adventurous spirit. His college days in Ann Arbor had given him a taste for the Midwest, and an exploratory visit to Chicago and the Ravenswood offices of Dr. Dodge inspired him to scrounge together the loans necessary to grab the opportunity. By the summer of 1886, he had moved himself and his bride Clara into their new home in a two-room flat behind the People’s Drug Store on Ravenswood Avenue. [photo: Ravenswood, late 1800s]

From early on, Abbott’s dual role as a house-call doctor AND professional druggist provided him a unique perspective on the weird world of late 19th century American medicine. On one hand, as an educated, ethical physician, he was righteously disgusted by the enormous number of bogus patent medicines and quackery being sold and advertised alongside legitimate treatments. At the same time, he gained a simultaneous sort of appreciation for the way many of those drugs were colorfully and cleverly marketed. His frustration, over time, became less about the moral high ground, and more about economics. Real medicines, made and sold by real doctors, ought to be holding a bigger market share than the snake oils peddled by harebrained druggists. And a licensed neighborhood physician, like himself, should be banking more coin than the huckster on the corner!

[W. C. Abbott, left, with secretary Ida Richter, assistant Eugenia Drach, and Dr. Alfred Burdick]

[W. C. Abbott, left, with secretary Ida Richter, assistant Eugenia Drach, and Dr. Alfred Burdick]

“We sincerely hope,” Abbott wrote, “that the physician will eventually awake to realize where he stands. Then, there will not be a drug store for every five or six hundred population, growing rich out of refilling prescriptions, counter prescribing patent medicines, while the hard working doctor in the same locality can scarcely make both ends meet. . . . Let the ordinary ‘drug store’ become what it now really is, a patent medicine stand, a soda water booth and smokers’ headquarters, and let the doctor practice medicine, please his patients, fill his pockets and dispense, if he likes, medicines bought where he pleases.”

One of Abbott’s own favorite sources of “legitimate” medicine was a Chicago drug manufacturer called the Metric Granule Company—led by a veteran salesman named William Thomas Thackeray. It was Thackeray, during some of his first visits to the People’s Drug Store, who played the key role in turning W. C. Abbott from a medicine man to a medicine maker.

What’s an Alkaloidal?

As it turned out, Dr. Thackeray was something of a convert to and missionary for the medical teachings of a controversial Belgian doctor by the name of Adolphe Burggraeve. “Have you heard of him?” he asked Dr. Abbott one day.

“Nope,” answered W.C.

“Well….” replied an excitable, walrus-mustachioed Thackeray [pictured], “you’re missing out on the revolution, my friend.”

“Well….” replied an excitable, walrus-mustachioed Thackeray [pictured], “you’re missing out on the revolution, my friend.”

As Abbott would quickly learn, Dr. Burggraeve—by then an elderly man—was the creator of a style of medicinal treatment called “Alkaloidal Therapy,” aka “dosimetry.” The concept was based on the idea that the traditional approach to administering drugs—via fluid extracts—was inefficient, unreliable, and more dangerous to patients. The alternative, he proposed, was to extract the basic active compound—known as the “alkaloidal”—from a plant or herb, and then to prepare it in a precise, measured form inside a granule. To put it another way, giving a patient a series of identical medicinal pills at regulated intervals was better than giving them a random swig of plant juice and waiting around.

Hearing the theory and absorbing Thackeray’s enthusiasm, Dr. Abbott dutifully did his own research into the matter. He learned that Dr. Burggraeve had received plenty of scorn for his methods, and that some people in the medical community considered him no better than the homeopathic patent medicine peddlers. In the end, Abbott let his own research frame his opinion.

“Thackeray, I’m totally into this alkaloidal thing,” he eventually told his comrade. “You were so right, dude.”

“Thackeray, I’m totally into this alkaloidal thing,” he eventually told his comrade. “You were so right, dude.”

Early drugs Abbott put into practice included aconitine (a fever reducer), digitalin (for heart spasms), atropine (for whooping cough), veratrine (digestive problems), and cicutine—which the Metric Granule Co. recommended for treating colic and to “curb excessive sexual passions.”

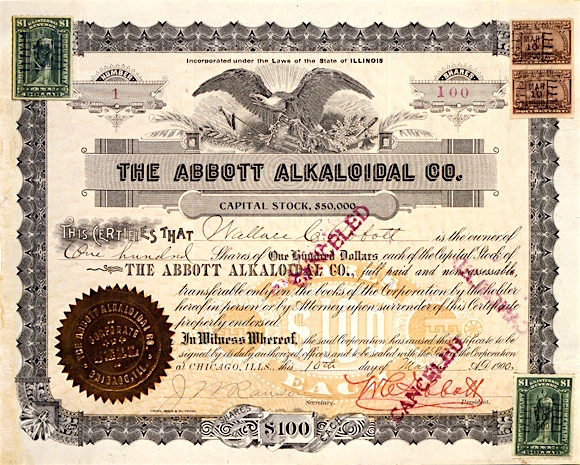

By the end of 1888, Abbott’s conversion to alkaloidism was so strong that he chose to forego paying for shipments of granules from other companies, and decided to start making them himself. The Abbott Alkaloidal Company was unofficially in business.

The A.A. Company

“I went about the thing in a very modest way,” Abbott later wrote, “one helper at a time, and I remember how puffed up with pride I was when my force had grown to five or six good girls. Knowing what I wanted for myself, I made the best granules I could; and I believe they were as good as could then be made.”

A noted work-a-holic, W. C. Abbott started his drug-making business out of his own kitchen, individually mixing his medicines himself while still running his drug store and riding his bike around Ravenswood making his usual house calls. The effort, fortunately, was paying off in spades. Abbott’s income leaped from $2,000 in 1888 to $8,000 in 1890, and he soon was able to employ a staff of helpers—most of them family and friends that had joined him from Vermont—to label products, keep the books, and man the store.

[A staff of young women cut the granules down to size at the Abbott offices]

[A staff of young women cut the granules down to size at the Abbott offices]

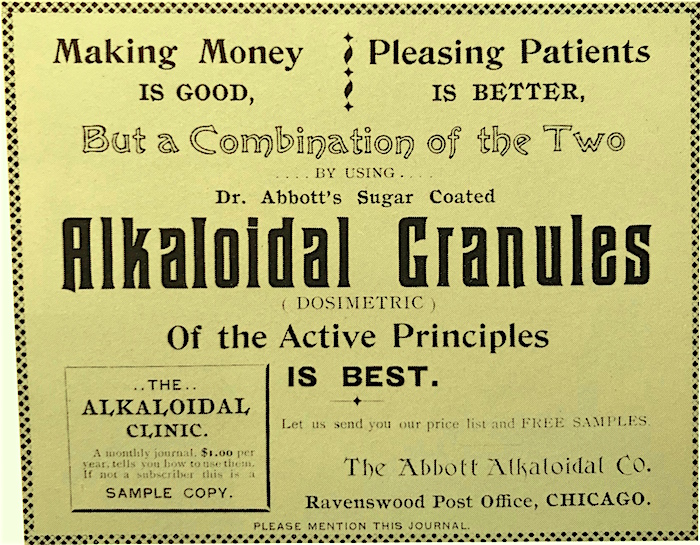

By 1891, feeling validated by his success, Abbott made a play for a new clientele outside the Chicagoland area. He purchased a small advertisement for 25 cents in the national publication The Medical World, in which he introduced his little operation to his fellow doctors nationwide.

WANTED: Every reader of THE MEDICAL WORLD using or interested in DOSIMETRIC GRANULES to send me their address at once. Dr. W. C. Abbott, Ravenswood, Chicago, Illinois.

He bought the same ad for several consecutive months, and each one gained a stronger reply. To those interested, Abbott sent away his new 14-page catalog, filled with 150 of his alkaloidal granules. Each and every one, he wrote, was “reliable, standard, well known to the profession” and “guaranteed to stand this test.”

As Abbott’s reputation and sales requests each ballooned, his new company was perpetually outgrowing its space. A year after the first catalog, the business was being run out of the Abbotts’ new mansion-house at the corner of Wilson Avenue and Hermitage Avenue (a landmark building that’s still there today). Special granulator machines were purchased to speed up manufacturing, and a new printing plant on Ravenswood was soon churning out a series of pamphlets and newsletters touting Abbott’s orthodoxy on all things alkaloidal.

[The former Abbott home and HQ at Hermitage and Wilson is still there today]

[The former Abbott home and HQ at Hermitage and Wilson is still there today]

Abbott never came to Chicago anticipating that’d he wind up running a factory, and as things got out of hand, he tried his best to stick to the familiar. Even after selling off the People’s Drug Store, he remained reluctant to give up his regular physician duties, and continued serving patients in-between his duties at the alkaloidal offices—peddling around town on his familiar bike from the local Beckley-Ralston Cycle Company.

Despite his own husky Teddy Roosevelt appearance, Abbott was a big proponent of fitness, and encouraged his employees to give up cigarettes (which he called the “tip end of the Devil’s tail”), exercise, and ride bikes to work. He didn’t suffer fools, but laziness was far worse than ignorance. Two signs above Abbott’s desk read “EVERYBODY GET BUSY!” and “DO IT NOW!” and he practiced what he preached.

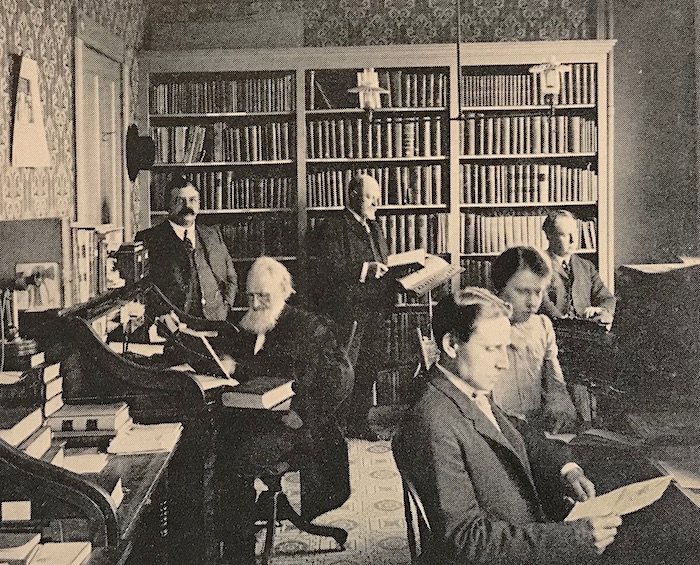

[In the Abbott company library, from left to right: W. C. Abbott, Dr. Ephraim Epstein, Dr. William Waugh, Dr. Henry Candler and his secretary, and Dr. Alfred Burdick, c. 1900]

[In the Abbott company library, from left to right: W. C. Abbott, Dr. Ephraim Epstein, Dr. William Waugh, Dr. Henry Candler and his secretary, and Dr. Alfred Burdick, c. 1900]

“He was at his desk at seven o’clock each morning, long before his staff arrived,” according to Herman Kogan’s interestingly titled 1961 company history, The Long White Line. “He followed an unswerving routine of rolling up his sleeves, removing his tie and then his shoes—he suffered from fallen arches and found shoes especially uncomfortable during the summer—and then preparing replies to the letters heaped on his cluttered desk or drafting articles for The Alkaloidal Clinic and other magazines.”

Fit to Print

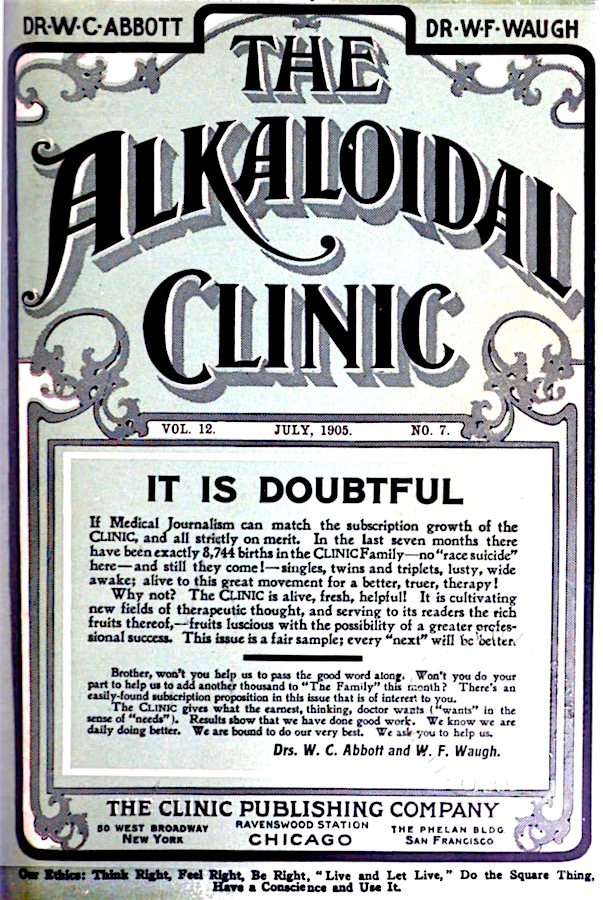

The argument could be made that the Abbott Alkaloidal publishing plant was actually more important to the company’s success than those bottles of granules themselves. Through self-published magazines like the aforementioned The Alkaloidal Clinic, Wallace C. Abbott was able to accomplish far more than he could with a mere catalog. Already deemed by The Medical World magazine as “the American champion of dosimetric medication,” he could now build on that reputation each month with articles and advertising that fine-tuned the alkaloidal manifesto.

Abbott worked on much of the published materials with a new business partner, Dr. William F. Waugh, dubbing themselves “the Alkaloidal Twins.” Along with touting their latest series of new concoctions, the twins always made a strong point of excluding any contributors or advertisers they deemed to be illegitimate or outside the physicians’ fraternity, calling them the unwelcome “hawkers of noxious nostrums.” In reality, Abbott simply didn’t want the bad optics of having quack medicine ads in a journal intended to help alkaloidal therapy escape from its own quack-ish reputation.

Abbott worked on much of the published materials with a new business partner, Dr. William F. Waugh, dubbing themselves “the Alkaloidal Twins.” Along with touting their latest series of new concoctions, the twins always made a strong point of excluding any contributors or advertisers they deemed to be illegitimate or outside the physicians’ fraternity, calling them the unwelcome “hawkers of noxious nostrums.” In reality, Abbott simply didn’t want the bad optics of having quack medicine ads in a journal intended to help alkaloidal therapy escape from its own quack-ish reputation.

Abbott took some considerable heat for elbowing patent drug makers out of the conversation, with some accusing him and others in the American Medical Association of trying to infringe on the individual rights of people to choose their own medicines.

“We say that these are the arguments of the rum hole,” Abbott responded, “and the brothel which steal men’s money and damn men’s souls. . . . Fakes and frauds of all kinds are being exposed. The people’s eyes have been opened to the evils of self-medication and the family physician is being recommended in all cases.”

In this philosophy, Dr. Abbott seemed to be standing shoulder to shoulder with the leading legitimate medical group in the country, the American Medical Association (AMA). He likely didn’t foresee that he’d soon be going to war with that organization himself.

Where There’s Smoke . . .

As annual revenues neared $200,000 at the dawning of the new century, W. C. Abbott finally decided to put his medical practice on the back burner and focus on his burgeoning drug empire.

As annual revenues neared $200,000 at the dawning of the new century, W. C. Abbott finally decided to put his medical practice on the back burner and focus on his burgeoning drug empire.

“In fifteen years,” he wrote, “from the simplest and most modest beginning possible, without a dollar of money outside of the proposition itself (my first public presentation a three-line adv. in The Medical World costing me 25c and pulling over $11.00 worth of orders), I have built up a business in quality second to none; and despite its enormous proportions, its opportunity is scarcely as yet entered upon—the field is scarcely scratched.”

Abbott was now essentially running two companies—Abbott Alkaloidal and the Clinic Publishing Company (each had its own building)—and had become a board member of several others. While mail order was still his bread and butter, increased competition finally led to the hiring of the company’s first traveling salesmen in 1904—each of whom was trained tirelessly to represent the Abbott interests as seasoned ambassadors.

“Always be high class and dignified,” Abbott instructed his sales recruits, “and win the respect of your prospective customers. . . . I would learn the place to get enthusiastic, the place to get solemn, the place to bang my firsts on the druggist’s counter, and the place to shut my mouth and keep quiet. I would defend our house to the last breath. I would try to be cheerful and optimistic at all times, or at least appear so to my trade, for it is the fellow with the cheery voice and the broad smile and the surplus enthusiasm that makes the best impression.”

For all the education he’d gained from the farm to the lab to the publishing office to the sales floor, Wallace Abbott was still very much learning on the fly as a 40-something CEO. And keeping every plate spinning was inevitably gonna lead to a few breaking.

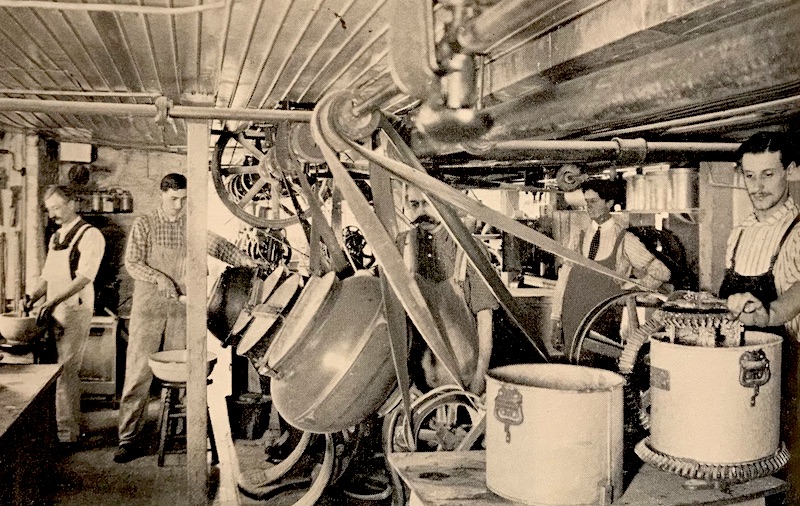

Conditions in the Abbott labs, for example, remained more Victorian than state-of-the-art. Located in the basement of one of Abbott’s Ravenswood office buildings, the lab “had a very low ceiling and a very unpleasant smell and noise,” according to former employee Ernest Richter.

In Herman Kogan’s company history, he further describes the scene:

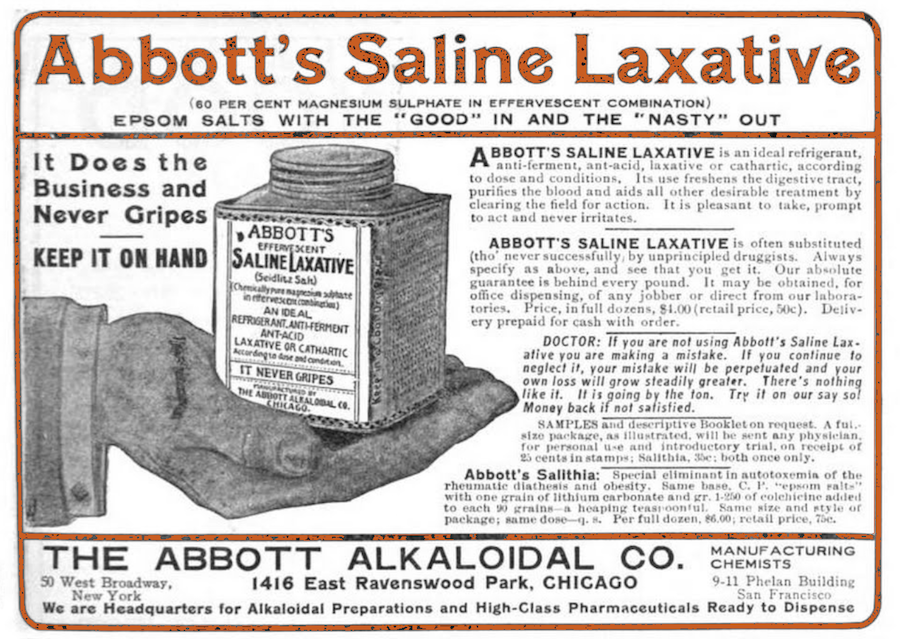

“In the center was a large gas engine with shafts and pulleys leading to the coating pans and tablet machines. In grinding drugs in mills, Richter and other laboratory workers wore no nose guards and sometimes were overcome by heat and odors, especially when preparing aconitine. Finished pills and granules were hauled by a rope elevator in an air shaft to the shipping and bottling room on the floor above, where Jennie Orum and Frank Rastell supervised thirty young girls. On the third floor were stored barrels of saline solution to be used to fill the many orders for Saline Laxative. Finished stock was kept in a two-story shed at the rear of the building, to which it was connected by an enclosed runway.”

[A turn-of-the-century granule production operation]

[A turn-of-the-century granule production operation]

According to the Ravenswood – Lake View Historical Association, “Fumes from the labs often caused workers to have to be sent home ill. And the chemicals, beside causing unpleasant smells, sometimes burst into flames, threatening the wooden homes located on the quiet streets behind the plant.”

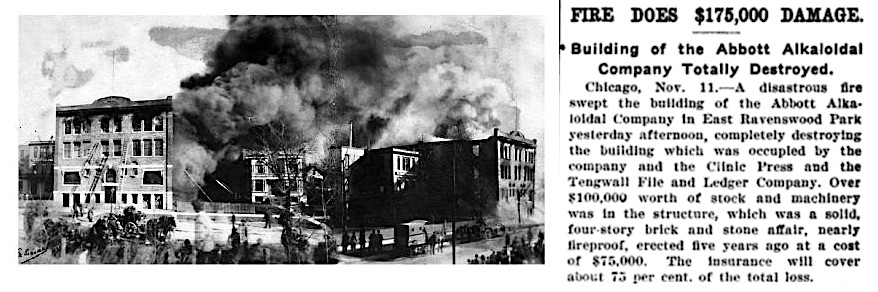

A disaster seemed inevitable, but surprisingly, it was the printing plant next door, rather than the chemical lab, that went up in a massive blaze in 1905, causing nearly $200,000 in damage. No employees had died, but Abbott was pushed to re-assess his entire operation. A new building was immediately commissioned, and a third party publisher was hired to keep Abbott’s various catalogs, flyers, and “medical journals” in circulation.

One of Abbott’s newest business partners, a young marketing guru named Simeon DeWitt Clough, was already injecting the company’s publications with a new level of color and bombast, and from his perspective, the recent fire disaster only offered an opportunity to spin an exciting new narrative. A 1905 issue of The Alkaloidal Clinic informed Abbott’s growing army of followers of the inferno—“one of the fiercest fires ever seen in this part of the city”—and included photos of the smoke plumes and the ugly aftermath. The article then took an inspirational turn, as Abbott talked of a rebuild and asked his loyalists to “Watch us grow, and help us all you can.”

Clough topped it all off with a kind of amazing folk poem / rap called “Keep a Pullin’”—emblematic of Abbott’s next-level approach to connecting with smalltown doctors on an informal, colloquial level.

‘Spose you haven’t got a cent, keep a’pullin’!

‘Spose you haven’t got a cent, keep a’pullin’!

Not a red to pay the rent? Keep a’pullin’!

Gettin’ busted ain’t no crime!

Gorry, ‘mighty—That’s the time

Grit will make a man sublime! Keep a’pullin’!

Can’t fetch business with a whine, keep a’pullin’!

Grin an’ swear you’re feelin’ fine, an’ keep a’pullin’!

Summin’ up, my brother, you

Hain’t no other thing to do:

Simply got to pull her through! So keep a’pullin’!

Remarkably, a new printing plant was completed just three months later, and the poet Mr. Clough was touting it himself in a later edition of The Alkaloidal Clinic: “Not only is the new building bigger than the old one but in every way it is better. It is the most modern and best-equipped printing plant and best of its size in Chicago and one of the best in the United States—We shall take a back seat for no one!”

The Abbott Company’s hyperbole was starting to sound more and more like the quack operators it railed against, and the establishment was taking notice.

The War In Drugs

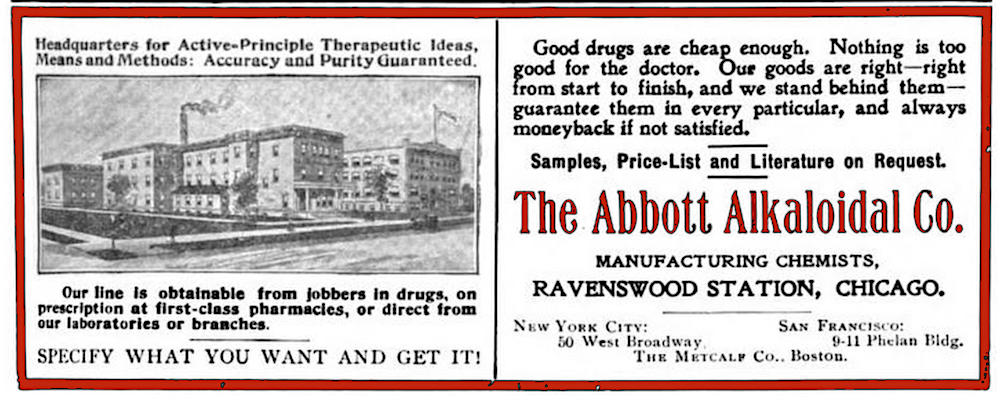

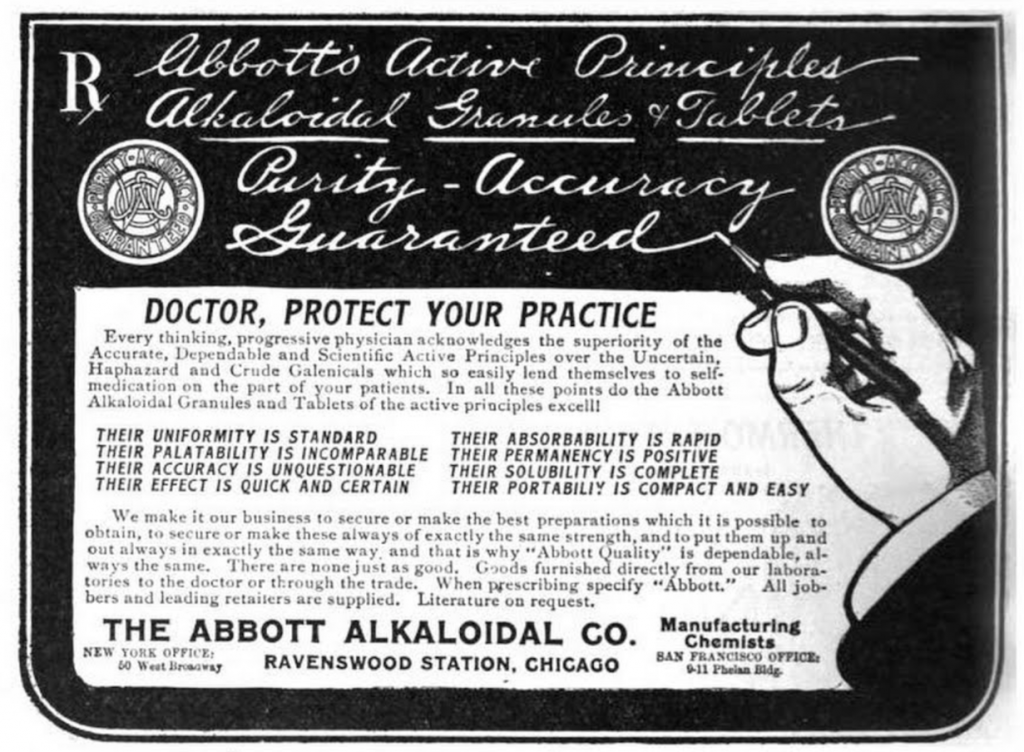

In 1908, Abbott Alkaloidal’s sales rose to an all-time high of $360,000, and distribution offices were running in multiple cities across the country and as far away as London. Yet another new building, a five-story colossus at 4753 N. Ravenswood, was built to house the entirety of the labs and manufacturing wing of the business. When members of the American Medical Association met for a convention in Chicago the following summer, Abbott representatives offered to chauffeur them up Lakeshore Drive to the Ravenswood headquarters, where’d they get a tour of the “huge establishment, employing hundreds of conscientious workers. It’s ‘on the square’ and we want to see you and get acquainted.”

Pride was not the only motivator for these friendly exercises. During this same period, the Abbott Alkaloidal Company was in a knockdown, drag-em-out fight for its very legitimacy, under direct fire from a former ally, the general secretary of the American Medical Association, Dr. George H. Simmons—who now referred to Abbott and his supporters as “the alkaloidal cult.”

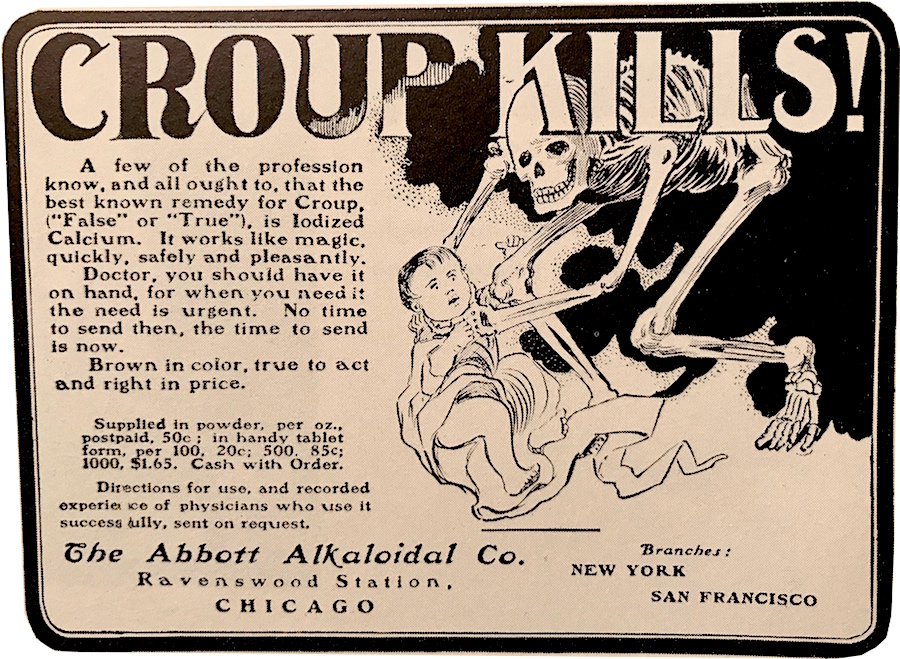

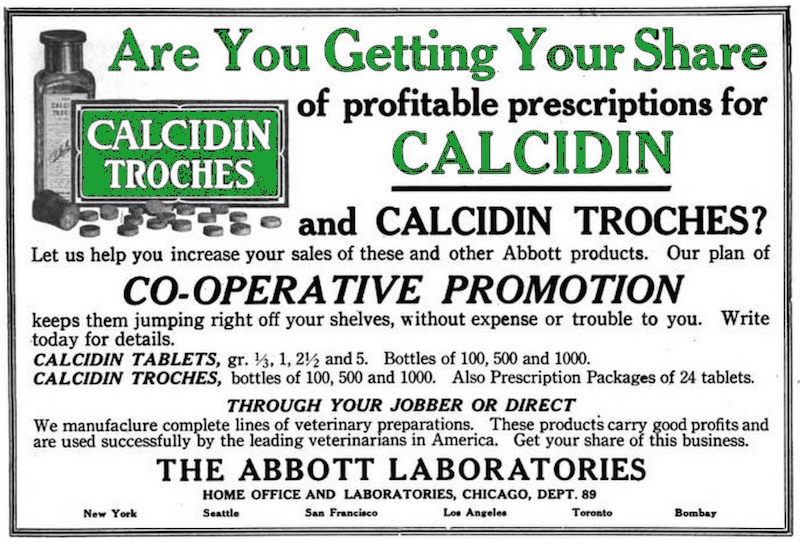

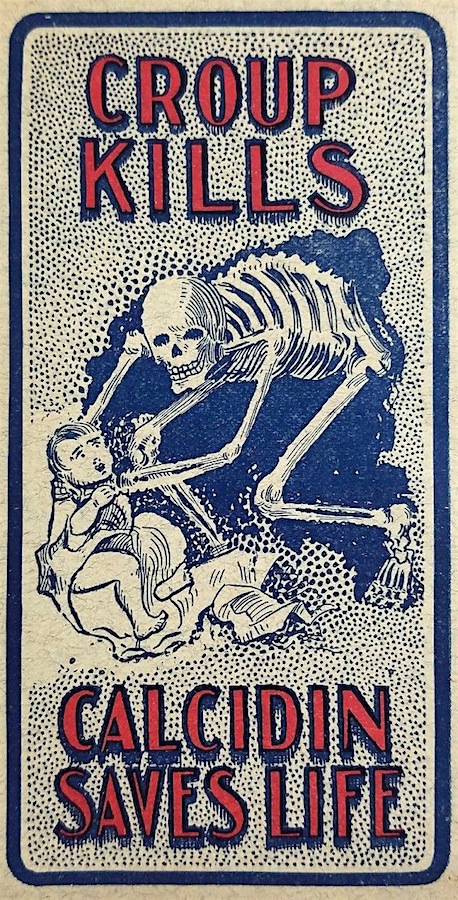

For years, the A.A. Co. had grown exponentially, using its own grass roots campaigns to convince doctors to embrace alkaloidals. This had included increasingly over-the-top editorial claims and eye-catching advertisements like the one below for Calcidin, featuring a skeletal grim reaper strangling a child. CROUP KILLS. CALCIDIN SAVES LIVES. Wallace Abbott sometimes offered his own commentary with that ad, writing, “Dear Doctor, I know this is a gruesome illustration, enough to give one the shivers; but, well, you have seen it more than once. You know how it is yourself, and I don’t want you to forget.”

For George Simmons—a former nostrum peddler himself, who’d been re-born as a crusader for ethical medicine with the AMA—the sensationalist nature of Abbott’s promotions, and the company’s unique ability to control the narrative around their own products by using its own “journals,” became infuriating. From 1907 to 1909, Simmons mercilessly attacked Dr. Abbott and his acolytes, even though the Journal of the American Medical Association itself was still taking ad money from far more obvious quacks in order to cover its budget. [pictured below: Dr. George Simmons]

According to Simmons’ personal “investigations,” he had concluded that W. C. Abbott “has used, and is now using, his position as a member of the medical profession as a commercial asset,” and that “the company is publishing what purports to be a medical journal devoted to the medical sciences and to the interests of medical practitioners, but which, to all intents and purposes, is a house organ devoted to the interests of the company and to the advertising of its products.”

According to Simmons’ personal “investigations,” he had concluded that W. C. Abbott “has used, and is now using, his position as a member of the medical profession as a commercial asset,” and that “the company is publishing what purports to be a medical journal devoted to the medical sciences and to the interests of medical practitioners, but which, to all intents and purposes, is a house organ devoted to the interests of the company and to the advertising of its products.”

Simmons also took aim at those products themselves.

“Alkaloids, as pure as [Abbott] can manufacture, are by no means rare or unique as remedial agents, and, furthermore, investigation by expert chemists has shown that many of his products are neither ‘alkaloids” nor ‘active principles,’ while not a few of them are typical nostrums.”

An enraged Dr. Abbott sparred with Simmons inside the pages of the AMA’s Journal, then threw a haymaker with the release of a 48-page defense treatise titled “An Appeal for a Square Deal,” in which he accused Simmons of being the ringleader of a “great scheme” to undermine the power of physicians to choose their medicines, in order to keep the 1900s version of Big Pharma—aka, professional druggists—in charge.

“What is the reason for these attacks?” Abbott wrote. “Why am I and my Company singled out for persecution when other men and other similar concerns enjoy complete immunity? Has there been complaint on the part of honest professional men using our products, or having financial dealings with us, that we have been unfair; have defrauded them; have given them anything but the ‘square deal’? We have never heard of such complaints. On the contrary, there is abundance of testimony from thousands of physicians all over the country that we have given them trustworthy goods and honest service.

“What is the reason for these attacks?” Abbott wrote. “Why am I and my Company singled out for persecution when other men and other similar concerns enjoy complete immunity? Has there been complaint on the part of honest professional men using our products, or having financial dealings with us, that we have been unfair; have defrauded them; have given them anything but the ‘square deal’? We have never heard of such complaints. On the contrary, there is abundance of testimony from thousands of physicians all over the country that we have given them trustworthy goods and honest service.

“All our literary work,” Abbott added, referring to Simmons attacks on his articles of self-interest, “in Clinical Medicine and elsewhere, is pervaded by two fundamental motives: first, the desire to raise the standard of therapeutic practice in this country; second, to give the greatest amount of practical help to the general practitioner—to support him in rightful, honorable independence.”

Simmons read Abbott’s pamphlet and fired back yet again.

“Astute but unprincipled demagogues have long recognized the physic value of raising the bogey of ‘persecution,” he wrote. “Befogging men’s judgment by means of an appeal to what may be called the commercial ‘unwritten law’ has long been popular with those whose actions would not stand close scrutiny. Convince your hearers that you are the weak and innocent victim of some huge (albeit shadowy and unsubstantial) conspiracy, and your battle is half won. . . . In a widely circulated pamphlet, entitled ‘An Appeal for a Square Deal,’ these tactics, as applied to the commercial side of medicine, have been adopted by the Abbott Alkaloidal Company—through its owner and president, Dr. Abbott—and are being played for all they are worth.

“. . . As has been pointed out, the Abbott Company is equipped to furnish not only the theory, the principles and the practice, but also the drugs for their application. It certainly would seem that a physician who in any way lends his support to the Abbott Company is nothing more than a penny-in-the-slot-machine of which Abbott et al. hold the key.”

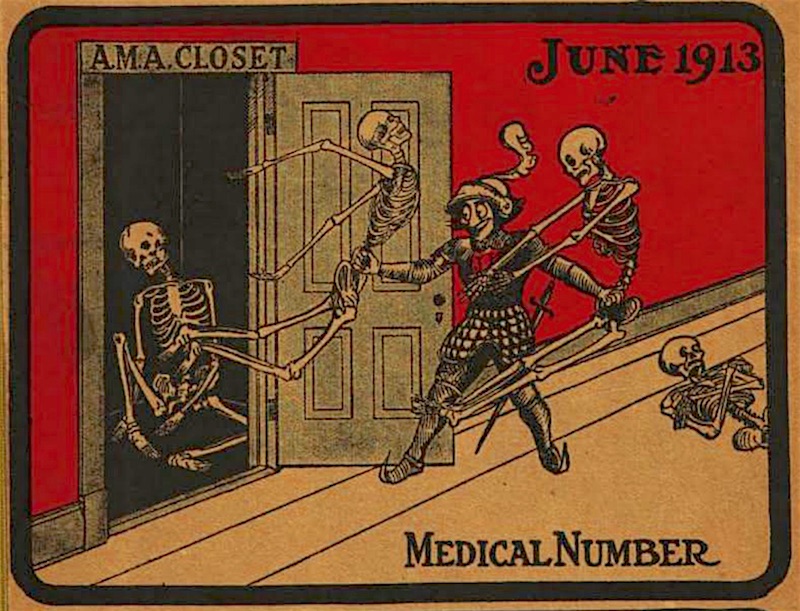

[A Nebraska journal called Jim Jam Jems illustrated what they saw as the hypocrisy of Dr. George Simmons and the AMA in 1913]

[A Nebraska journal called Jim Jam Jems illustrated what they saw as the hypocrisy of Dr. George Simmons and the AMA in 1913]

The war was getting vicious, and Abbott had plenty of supporters ready and willing to call out Dr. Simmons on his own hypocrisy. Abbott’s own final statement on the matter took a wider view, painting himself as representative not just of his beloved alkaloidals, but of freedom for the medical practitioner.

“In the medical profession, as in religion or science, the perils of dominating influence can not be escaped. Every physician having the interest of his profession, and of humanity, at heart, should admit candidly the value of any method, theory, or practice which may promote the common object of alleviating human misery, taking the generous view of things, without which the pursuit of learning is but a jaundiced, melancholy affair.

“. . . I can not close the discussion of this matter, one which is of such vital importance to me, and I believe also to every other member of the profession who believes that intelligent thought and honest independent effort should be free, untrammeled by the incubus of personal hatreds and the fixed and unvarying dicta of self-made authorities, without a plea to you to think gravely on all these things, all this injustice, and to what they and it may lead. With this final thought, this plea for justice, satisfied of the righteousness of my cause, but always seeking to do more for the doctor, I leave my case in your hands.”

Beating the Germans

W. C. Abbott’s epic feud with George Simmons made him a poster boy for a small but growing movement against the American Medical Association. By 1910, however, a 53 year-old Dr. Abbott seemed to realize that continuing to grapple with the powers-that-be would eventually do more harm than good in the almighty pocketbook. Business was too good, and too many people depended on him, to stay in the mud any longer.

“I cannot afford to go hunting for trouble,” he wrote to a cohort. “I have gone through enough in the past few years and am glad to have a little respite.”

[Team Picture, 1916, top row: Simeon DeWitt Clough, Edward Ravenscroft, Franklin Summers, & Dr. Abbott. bottom row: Josiah McLaughlin, John Charles Brown, Dr. Al Burdick]

[Team Picture, 1916, top row: Simeon DeWitt Clough, Edward Ravenscroft, Franklin Summers, & Dr. Abbott. bottom row: Josiah McLaughlin, John Charles Brown, Dr. Al Burdick]

The strategy paid off. Greater transparency and a more conservative approach eased tensions and got Abbott Alkaloidal adverts back into the pages of the Journal of the AMA. At the 1910 AMA convention in St. Louis, Abbott Alkaloidal had its own exhibit, boasting of its relationships with 50,000 out the 130,000 practicing physicians in the U.S., along with 1,000+ in Europe and 500 in Latin America.

In the company pamphlet, Dr. Abbott—while not going on the attack—certainly seemed to claim victory for his side. “By the study of our own clinical observations as well as that of thousands of others with whom we are in touch, we have lived to see a large proportion of the profession come to our standpoint, in this particular at least . . . The alkaloidal movement is the most vital fact in modern therapeutics, and for that matter in all medicine today. It is bound to go forward, for it is right.”

Bold pronouncements aside, Abbott knew he was operating in a changing industry and changing world. The “Pure Food and Drug Act” of 1908, championed by people like George Simmons, was cracking down not only on quack medicine, but on extreme, unsubstantiated claims by any and all manufacturers. As such, Abbott’s marketing approach evolved—out of the Wild West and into the modern era. Though they’d been dragged kicking and screaming, the A.A. Co. was in prime position to flourish in the years ahead.

Part of this development involved expanding beyond the company’s 25 year reputation as “those alkaloidal guys.” Yet another of Dr. Abbott’s apprentices, Dr. Alfred Burdick [pictured], had more foresight than his boss on this matter.

Part of this development involved expanding beyond the company’s 25 year reputation as “those alkaloidal guys.” Yet another of Dr. Abbott’s apprentices, Dr. Alfred Burdick [pictured], had more foresight than his boss on this matter.

Years earlier, Burdick had wisely convinced his cohorts to change the name of their primary periodical, The Alkaloidal Clinic, to the far superior sounding American Journal of Clinical Medicine. Now, with sales starting to slow at the beginning of the 1910s, Burdick’s wisdom came through again, as he argued for synthetic medicinal chemicals to become a much bigger focus of the company’s research and lab production. He also suggested a name change for the company itself—from Abbott Alkaloidal to Abbott Laboratories. The change went official in 1914, right around the time the little bottle of Menthol from our museum collection was likely sold (hence why it is identified with both the “Abbott Laboratories” and “A.A. Co.” names).

When World War I broke out that same year, the company’s recent changes proved massively important, and basically set up it on its course toward 20th century pharmaceutical domination.

“As the war surged on in Europe,” Kogan wrote in The Long White Line, “the shortage in essential drugs and chemical supplies from Germany grew drastic and new opportunities accrued to Abbott Laboratories.”

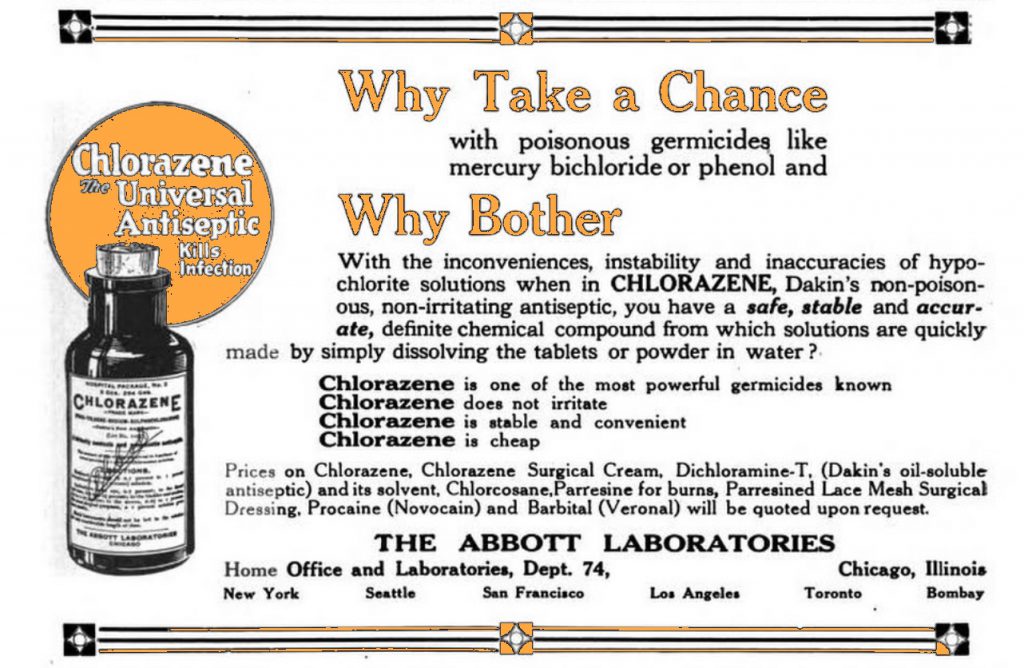

In 1917, the brand new Federal Trade Commission opened the doors for U.S. companies to start manufacturing their own versions of patented German drugs, and Abbott Labs busted through those doors—led by Dr. Burdick and a 28 year-old chemist named Roger Adams, who led their successful development of new synthetic versions of veronal, novocaine, and atophan. Abbott sales topped $1.4 million by the end of the war, and as Kogan put it, “the company had taken its biggest step toward becoming a full-fledged pharmaceutical firm with organized scientific research and diversified products.”

[Abbott advertisement for its new drug Chlorazene in 1919]

[Abbott advertisement for its new drug Chlorazene in 1919]

End of an Era, Birth of a Giant

Even though the Abbott Company was on the rise, there was a bit of sadness hanging over the Ravenswood complex as the 1920s began. For one thing, the company was winding down its days in the neighborhood it had called home for 30 years. The need for more space—and the appeal of cheaper rent—led to the purchase of land in suburban North Chicago, about 30 miles to the north, where a massive new Abbott headquarters was now under construction. A more pressing matter, however, was the failing health of W. C. Abbott himself.

Though he managed to be there for the groundbreaking ceremony on the North Chicago complex, he had long since handed over daily control of the company to Dr. Burdick. Abbott was suffering from kidney disease, and none of his own best methods were going to prevent the inevitable. The Ravenswood era would end with him in 1921.

[Abbott, in his final year of life, still riding his trusty bike among family and friends, his wife Clara seated to his left]

[Abbott, in his final year of life, still riding his trusty bike among family and friends, his wife Clara seated to his left]

“The death of Dr. Wallace Calvin Abbott on July 4th, 1921, takes away a man who possessed to a marked degree the rare twin quantities of a professional man and a sales builder,” the periodical Sales Management reported.

“In a period when a very vicious tendency to therapeutic nihilism and the operative itch unduly obtained,” added Chicago Academy of Medicine secretary Dr. James G. Kiernan, “Dr. Abbott was conscientiously and deeply devoted to therapeutic ideals.”

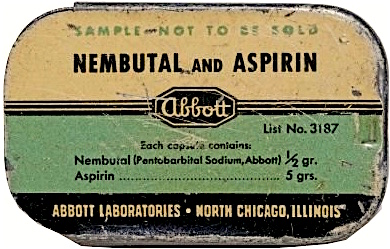

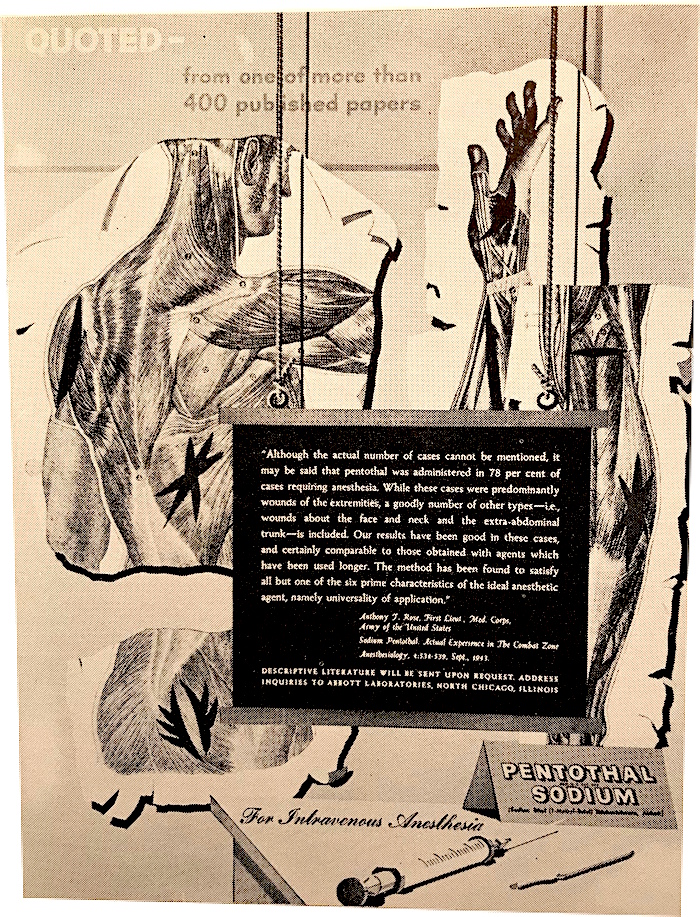

Over the next 100 years, Abbott Laboratories took on a form that would be largely unrecognizable to Wallace Abbott himself. It became a publicly traded company just before the market crash of 1929 (a $32 share from that year would be worth upwards of $300,000 today). In the 1930s, the company braved the hard economic times by developing major medications like Nembutal (a sedative) and Sodium Pentothal, an anesthetic that’s known to some non-professionals as the “truth serum.”

Over the next 100 years, Abbott Laboratories took on a form that would be largely unrecognizable to Wallace Abbott himself. It became a publicly traded company just before the market crash of 1929 (a $32 share from that year would be worth upwards of $300,000 today). In the 1930s, the company braved the hard economic times by developing major medications like Nembutal (a sedative) and Sodium Pentothal, an anesthetic that’s known to some non-professionals as the “truth serum.”

In the 1940s, Abbott was part of a joint effort to produce mass amounts of penicillin for the war effort, and it also developed the drug Tridione to help curb epilepsy attacks in some children. The following decade, the accidental discovery of an ultra-sweet sugar alternative, Sucaryl, gave Abbott one of its first big general consumer products, put to use in the low-calorie cola market, as well as frozen fruits, baked goods, and jams.

The company’s signature accomplishment, in the eyes of many, was the creation of the first FDA-approved HIV test in 1985—a major breakthrough in the early fight against AIDS.

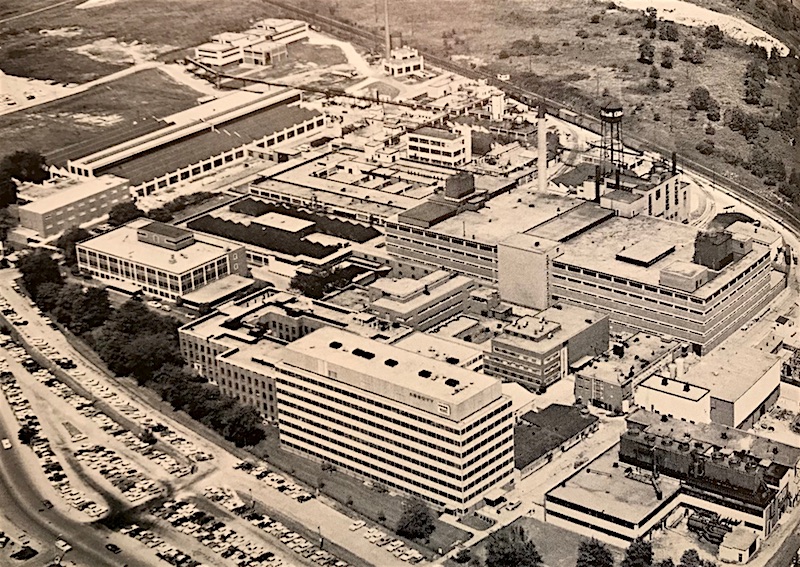

[The Abbott complex in North Chicago, c. 1960]

[The Abbott complex in North Chicago, c. 1960]

Today, the multi-national pharma juggernaut rolls along, headquartered not too far away in Lake Bluff, IL. It’s regularly ranked among the best major American employers in terms of worker treatment and positive atmosphere.

As Wallace Abbott once said, “You cannot talk merit into your product, it must be put there. . . . Give your customer everything he deserves, teach your men how to present it, make your prices right, sell your goods, at get your money!”

I doubt he ever had $20 billion in mind, but he’d sure love to wave that number in his skeptics’ faces.

[During World War II, Abbott published a series of posters to support the effort]

[During World War II, Abbott published a series of posters to support the effort]

SOURCES:

—The Long White Line: The Story of Abbott Laboratories, by Herman Kogan, 1961

–“Concerning the Abbott Alkaloidal Company,” California State Journal of Medicine, Vol VI, No. II, 1908

–“Abbott Alkaloidal Company” – Malcolm A. Goldstein, onbeyondholcombe.wordpress.com

–“Abbott Laboratories: Provisioning a Vision” by Brandon Burrell, Florida State University, 2013

—The Alkaloidal Clinic, Vol. 12, Issue 2

–“An Appeal for a Square Deal” – Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 51, 1908

–“Simmons and His Record,” Jim Jam Jems, June 1913

—Medical Monopoly: Intellectual Property Rights and the Origins of the Modern Pharmaceutical Industry, by Joseph M. Gabriel

–“A Doctor Who Shattered Tradition” – Sales Management, Vol. 3, 1921

—Chicago Portraits: New Edition, by June Skinner Sawyers

—Miracle Medicines: Seven Lifesaving Drugs and the People Who Created Them, by Robert L. Shook

—The SAGE Encyclopedia of Cancer and Society, edited by Graham A. Colditz

—The Encyclopedia of the Industrial Revolution in World History, Volume 3, edited by Kenneth E. Hendrickson, III

–“Wallace Calvin Abbot” – NNDB.com

–“Sodium Thiopental” – wikipedia.com

I love history, learning, and teaching. I am especially interested in the history of medicine, pharmaceuticals, natural medicines, and conventional medicines. Ensure is a product made by the descendants of Dr. Wallace Calvin Abbott’s company that most people in the USA recognize. Thank you Made in Chicago Museum for this informative post!

I have a soft cover (14″×10″) 64 page catalog of “PRIZES” available to Abbott Laboratories sales personnel covering the year 1939. Each item is pictured, described, numbered and accompanied by a number in parentheses, presumably the points(?) necessary to acquire the item. I have been unable to find out anything about this prize book. Contacted Abbott by phone and got switched to multiple dead ends. Found nothing on the internet. HELP!

I have to very old bottles I don’t know what they are they both say abbott on the bottom one amhas a 1 the other has a 6 they are both the same size

I have a doctor medicine full array of drugs in a kit from around the turn of the century.

would like some infomation on

For a take on a physician who discovered, used, and promoted Abbots Alkaloids– and then in 1890s was invited by WC Abbot to come run his library in Ravenswood, and work as an editor of the journal see The Extraordinary Dr Epstein. A biographical novel by his great granddaughter Susan Lee Kerr. Dr Ephraim Epstein is the white-haired elder at the desk seen in the photograph of Abbots’ offices in this article. Thank you for this article– I did not know WC Abbots whole story.

My great grandfather was Ephraim M. Epstein, M.D. He led a rich, colorful life, starting as a child in Czarist Russia and emigrating to the U.S. in the 1840’s. He was an early proponent of Burggraeve’s dosimetric medicine. After he retired from practicing, he was invited to write a regular column called “Gleanings from Foreign Fields” for the American Journal of Clinical Medicine, which he did up until his death in 1913. W.C. Abbott published a thoughtful obituary for him, stating “To say that he has been an essential factor in this work of ours…is putting great facts, treasured in memory, into mere words that but feebly express half the feeling of his coworkers…toward their departed friend…” (from March 1913 edition of the American Journal of Clinical Medicine).

Retired from Abbott/abbvie in 2015 after 29 years. Thanks for the article.

I have a wooden bottle containing calcium iodized #356 gr1-3 Calcidin.. The bottle is 2 inch tall and 5/8 inch diameter. Do you have any idea when this was made and packaged in a corked wooden bottle? The Abbott Alkaloidal Co. So as far as I can tell it was between 1891-1914. This is the only bottle I have seen that was wooden, all others were from that era are brown glass. Does anyone have any information? Thanks

I have a old medal syringe ,all medal , I need it dated ,if could help me call 3035949884 ,thank you !!! It has to be real old !! ON it says veterinary dept The abbott alkaloidal Chicago

Another lil’ fun fact—- my bud is the head engineer at Revolution Brewing—- he found some old bottles at the site when they were excavating for supports for their new giant fermenters—— U.S. Brewing Company , a much older brewer in the same area

I believe Abbott’s old site in Ravenswood became Northwestern golf clubs—- also FYI Miles White Abbott’s former CEO built an EXACT replica of Dr. Abbott’s Ravenswood house in Abbott Park

Very cool! I retired from Abbott/Abbvie North Chicago Chemical/Fermentation Ops—- I mastered all of the most dangerous & dirty jobs they had to offer— we almost succeeded in getting Mike Rowe to film there but the big whigs shot it down