Museum Artifact: Adlake Truck Lamp, c. 1910s

Made by: Adams & Westlake Co., 320 W. Ohio St. / 319 W. Ontario St., Chicago, IL [River North]

Much like one of today’s showbiz power couples, the partnership of Chicago railroad supply magnates John McGregor Adams and William Westlake produced its own linguistic portmanteau in the late 1800s, as the name “ADLAKE” (combining ADams and WestLAKE) soon evolved into their company’s primary identity. You can see the all-caps evidence on the lid of our museum artifact, a Model 4435 ADLAKE Oil Side Lamp from the 1910s.

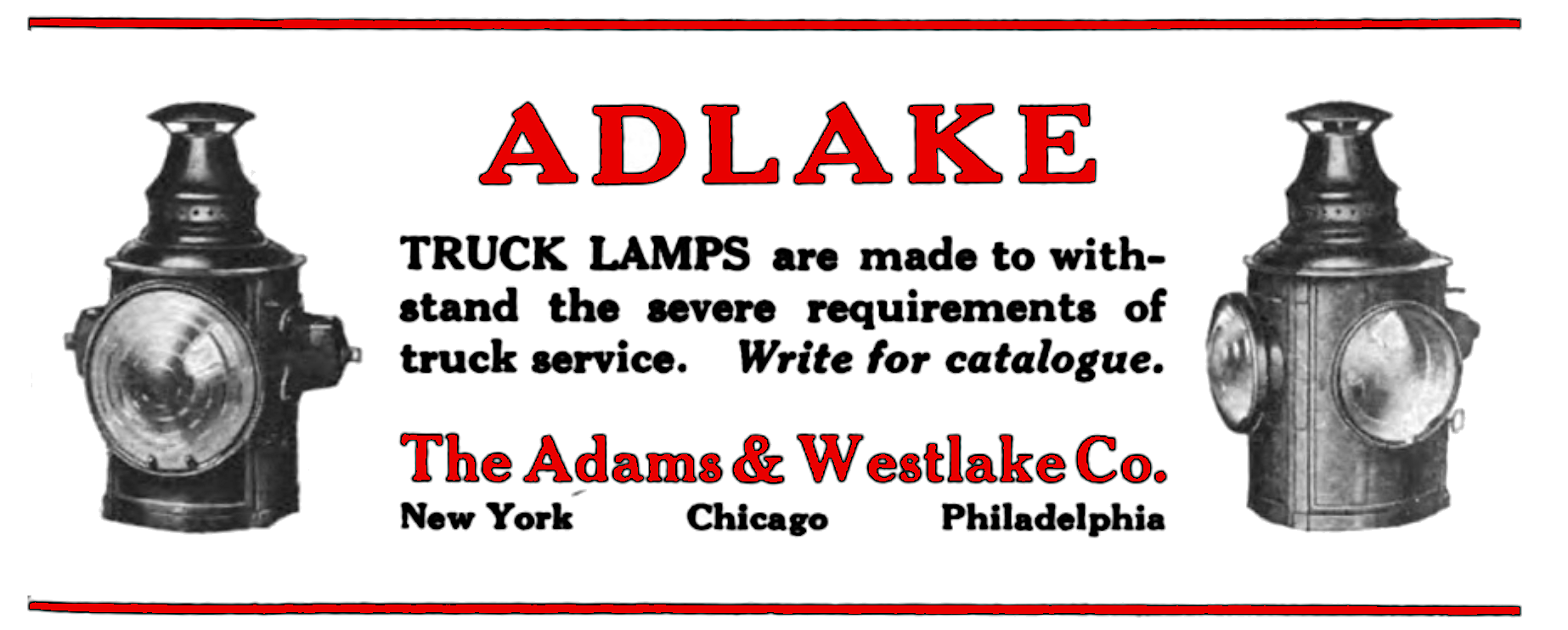

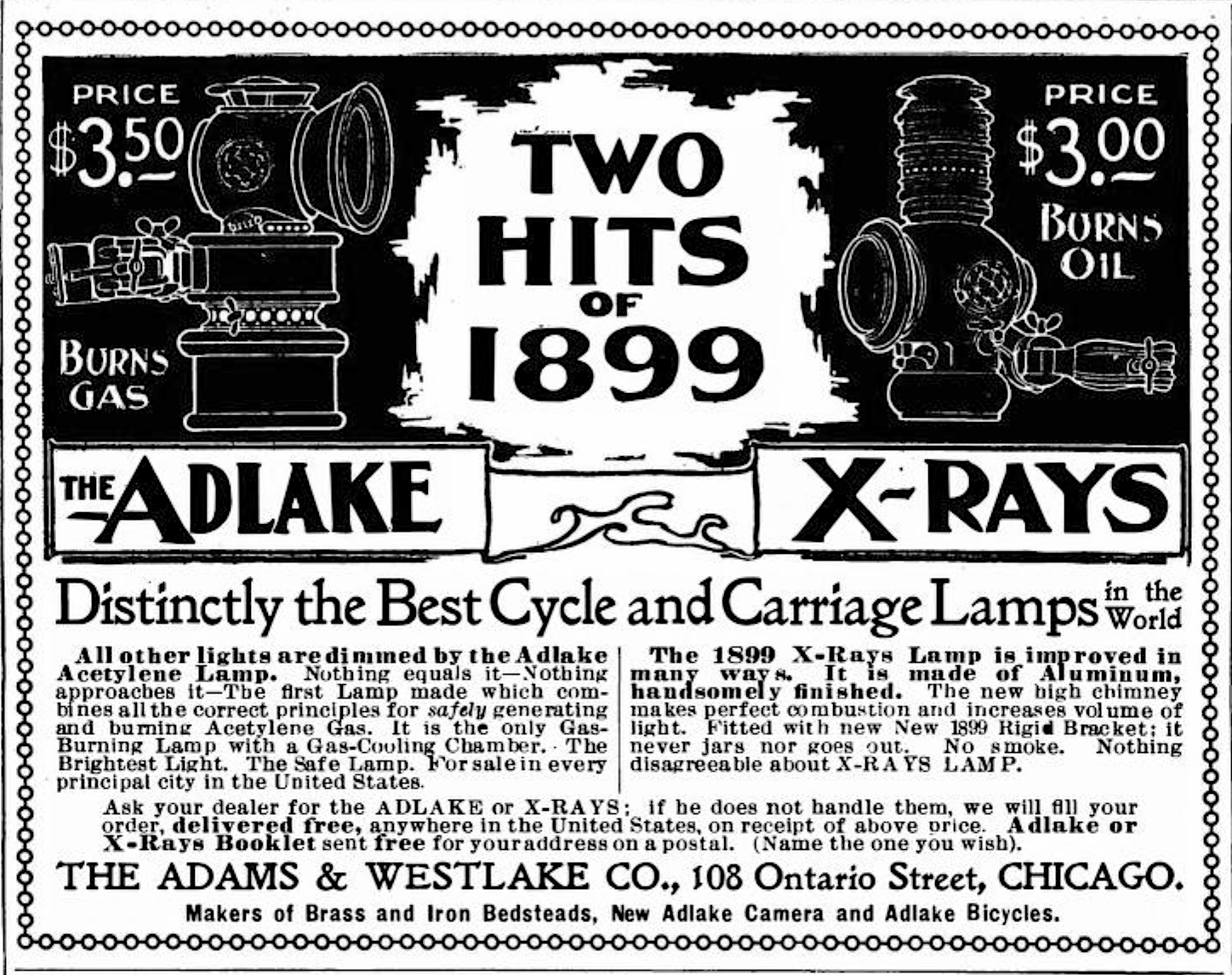

“The word ‘ADLAKE,’ the trademark of the company, has become synonymous with the word ‘BEST’ in the minds of the careful buyers in the railway field,” claimed a 1911 Adams & Westlake Co. advertisement. And indeed, that reputation was carrying into other, more modern modes of transport, as well.

“The word ‘ADLAKE,’ the trademark of the company, has become synonymous with the word ‘BEST’ in the minds of the careful buyers in the railway field,” claimed a 1911 Adams & Westlake Co. advertisement. And indeed, that reputation was carrying into other, more modern modes of transport, as well.

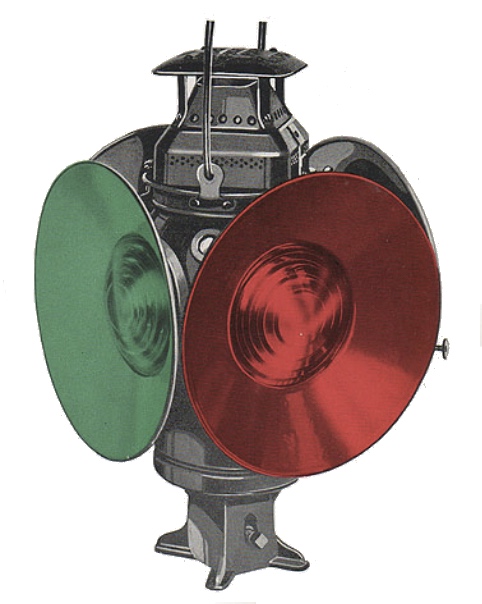

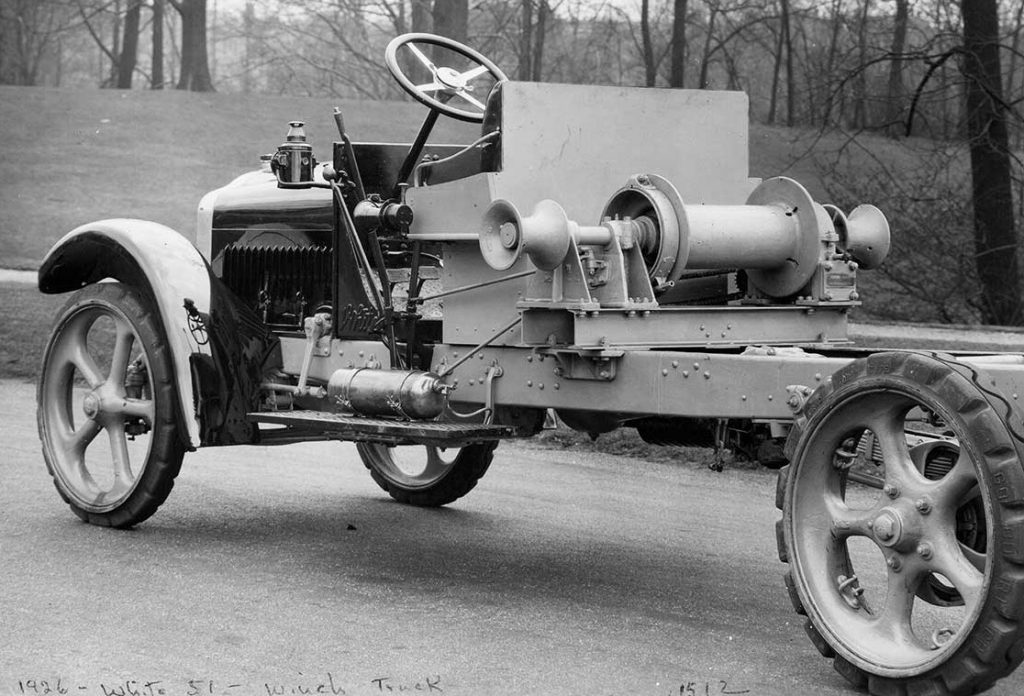

While Adlake has always been associated primarily with railwayana, the lantern in our collection isn’t one of their classic engineer’s signal lamps, but instead represents the company’s gradual adaptation to the demands of the motor age.

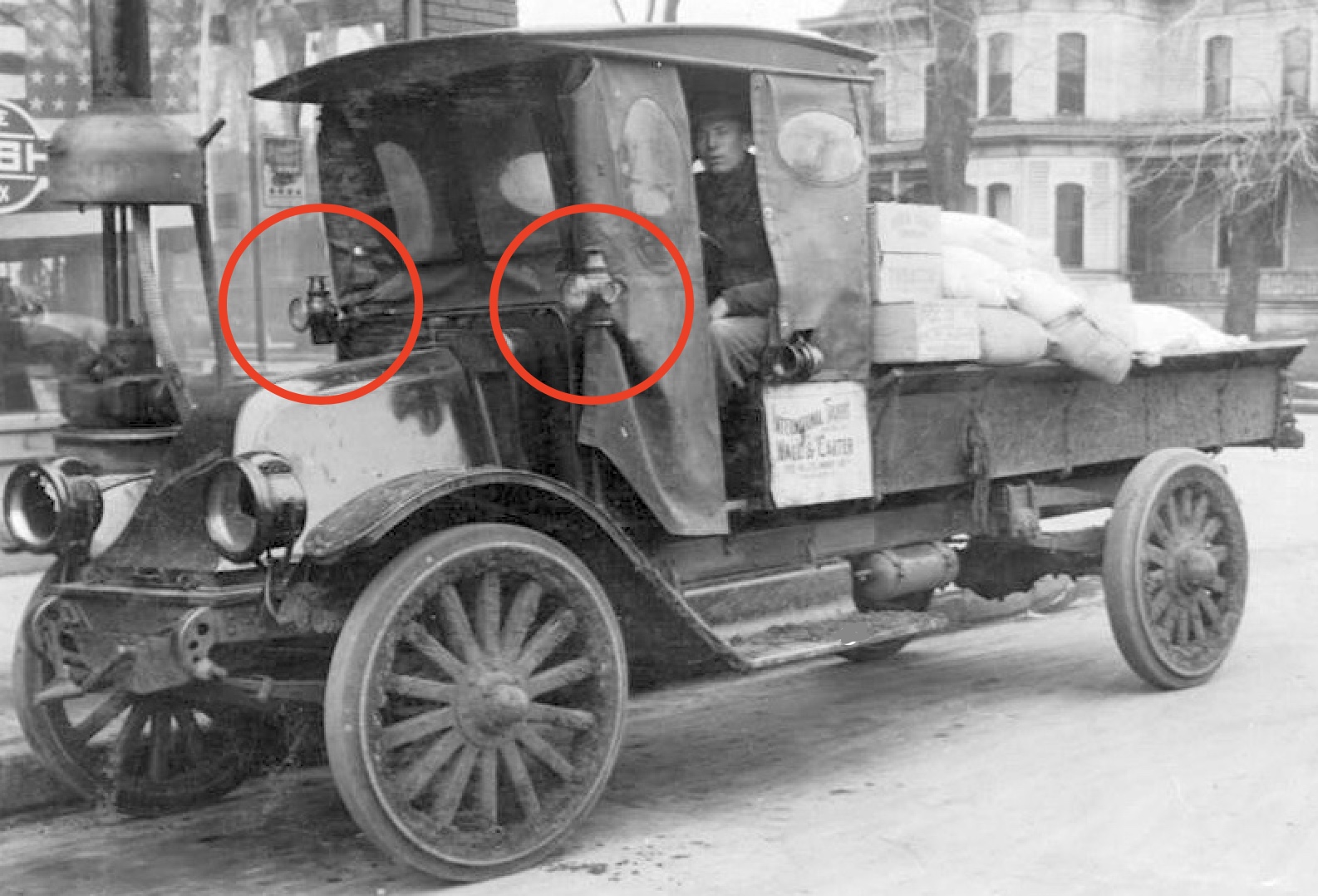

Known as a “side lamp,” “carriage lamp,” or “truck lamp,” our artifact would have been sold in pairs and designed specifically for use on the front of early automobiles (particularly delivery/work vehicles) in the years before electric car lighting became the norm in the 1920s. They were basically makeshift, oil-powered headlights that truck owners could manually attach via double-support fork brackets. Our particular model, the 4435, is a biggish one: 10 inches tall and fitted with a 5-inch clear lens. This was at least sizable enough for America’s pioneering truck drivers to keep their front grills half illuminated.

According to a page in the 1920 catalog of the Pittsburgh Auto Equipment Co., “the Adlake Line of Truck Lamps was put on the market to meet the demand for a lamp which would withstand the severe conditions imposed upon them in truck service. The bodies are made of steel and the lamps are constructed with the Adlake Balanced Draft Ventilation which insures proper burning and a clear lens under all weather conditions.

“Being fitted with Long-time Burners, they will burn 20 to 24 hours with one filling of the oil fount. This fount is contained within the lamps, thus preventing the loss of this part, as is the case with drop bottom lamps. The Adlake lamps are used as standard equipment by most of the prominent truck manufacturers.”

Asking price for a pair of our ADLAKE Truck Lamps in 1920? $15.75, or about $200 after inflation.

Because Adlake lanterns, locks, and latches were produced in enormous volume for a considerably long period of time, it’s not unusual to see these rusty wares still kickin’ around in junk shops. What casual antiquers may not know is that the original company is actually still in business, producing a significantly smaller array of transportation accessories in the same town it’s called home since 1927: Elkhart, Indiana.

If we’re talking about the true salad days of the Adams & Westlake Company, however—when the namesakes themselves were still on the scene—you have to go back a bit further back in time . . . and further west on the map.

The ADLAKE Origin Story

It’s been generally accepted over the decades that the business ultimately known as Adams & Westlake was founded in Chicago way back in 1857. It’s the starting point from which the company has marked its various milestone anniversaries, and it’s still the year of establishment noted on the current Adlake website. Substantiating that date, however, is a bit of a tricky exercise.

For one thing, William Westlake didn’t even arrive in Chicago until 1863, and his official working relationship with J. McGregor Adams wouldn’t begin until nearly a decade after that, in the aftermath of the Great Chicago Fire. With this in mind, the year 1857 looks more like an approximation of Mr. Adams’ arrival in the city, when the then 23 year-old New Hampshire native was sent west by his employer, a growing New York railroad supplies dealer called Morris K. Jesup & Co. (later Jesup, Kennedy & Co.). The firm had rightly foreseen that the future of the American railroad ran through Chicago, and Adams would thus be their young Illinois emissary.

For one thing, William Westlake didn’t even arrive in Chicago until 1863, and his official working relationship with J. McGregor Adams wouldn’t begin until nearly a decade after that, in the aftermath of the Great Chicago Fire. With this in mind, the year 1857 looks more like an approximation of Mr. Adams’ arrival in the city, when the then 23 year-old New Hampshire native was sent west by his employer, a growing New York railroad supplies dealer called Morris K. Jesup & Co. (later Jesup, Kennedy & Co.). The firm had rightly foreseen that the future of the American railroad ran through Chicago, and Adams would thus be their young Illinois emissary.

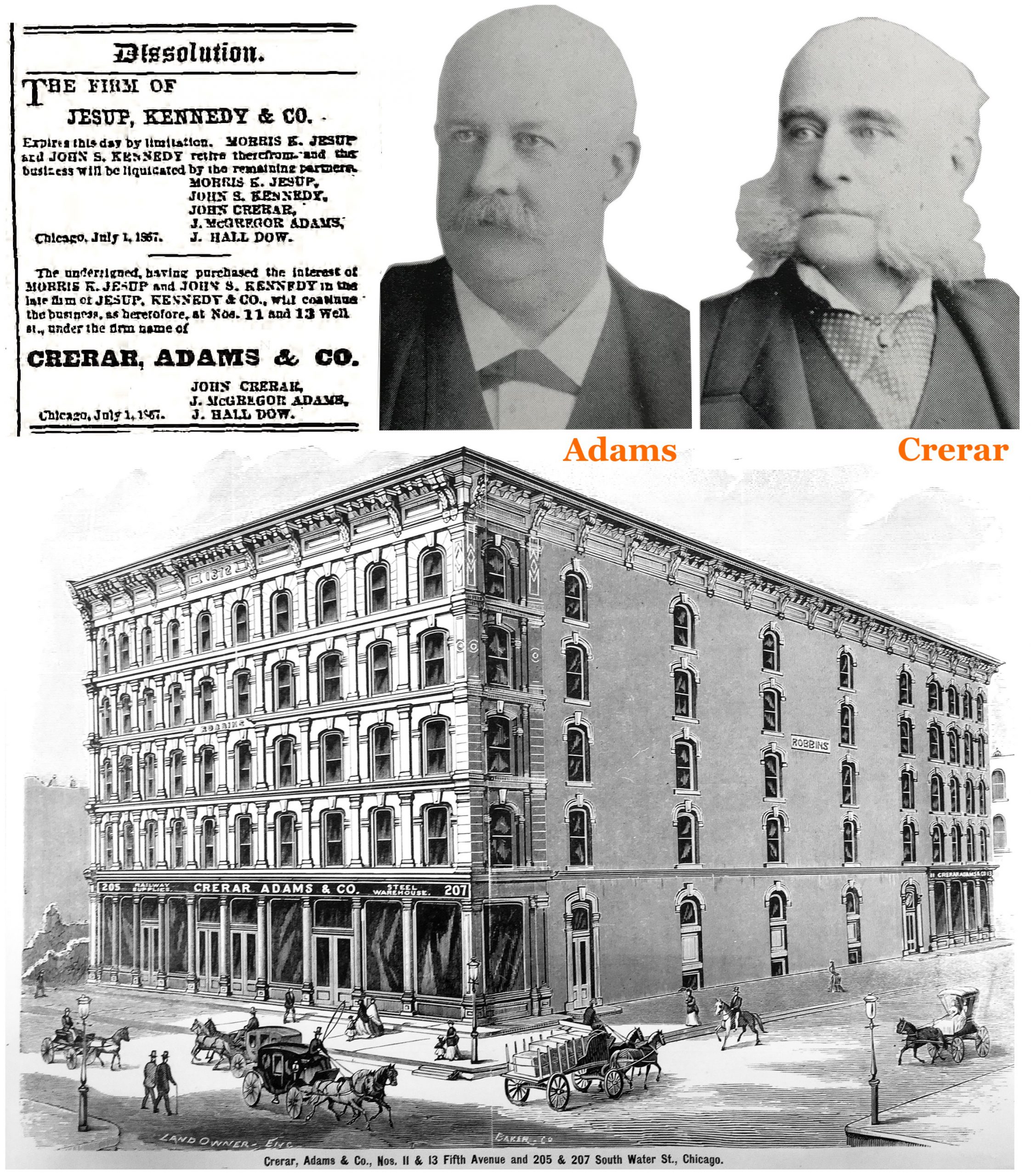

In 1862, in the midst of the Civil War, another partner in the Jesup firm—a 35 year-old New Yorker named John Crerar—joined Adams in Chicago, and the two junior partners soon took a controlling interest in the business. Again, there are a lot of conflicting dates out there as to when Adams and Crerar officially grabbed the reins, but the July 15, 1867 issue of the Chicago Tribune provides us at least a proper public announcement of the dissolution of Jesup, Kennedy & Co. and the formation of its immediate successor: Crerar, Adams & Co.

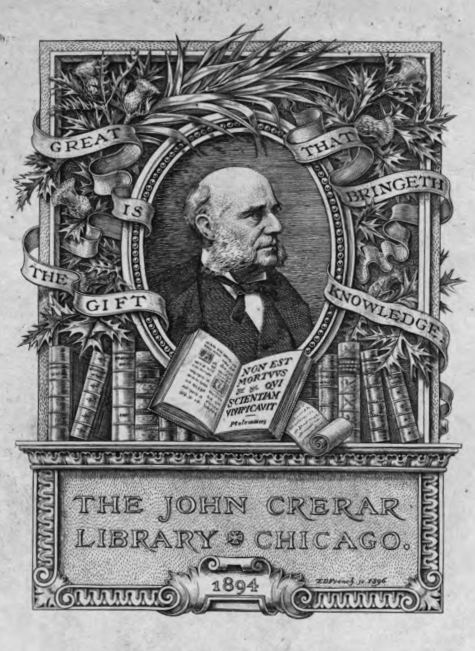

[Top Left: Newspaper report of company name change to Crerar, Adams & Co., 1867. Top Center: J. McGregor Adams and his mustache. Top Right: John Crerar and his mutton chops. Put them together and you’d almost have a full beard. Below: One of the firm’s rebuilt, post-fire office buildings, located at 205-207 South Water Street; engraving from The Land Owner (1873) and scan from Chicagology.com.]

John Crerar, whose name lives on through a substantial personal library now housed at the University of Chicago, was just as essential to the early development of the Adlake business as either of the gentlemen memorialized in its trademark. Taking the slightly younger Adams under his wing, Crerar helped establish the original company offices at 11-13 Wells Street, along with a state-of-the-art new factory on Franklin Street, between Ontario and Ohio Street. When these properties were then swiftly torched and reduced to rubble in the Great Fire of ’71, Crerar financed much of the rebuilding effort, opening new buildings in the same locations within a year or two (interestingly, Wells Street was known as Fifth Avenue for much of the late 19th century, as city officials decided that the seedy stretch of road could be seen as an insult to Mr. Wells himself).

This is also about the time that our friend William Westlake finally enters the picture.

A native of Cornwall, England, Westlake (b. 1831) had come to America with his family as a kid in the 1840s, first settling in Chicago, then Milwaukee. It was in Wisconsin that William found his niche as a metalworker and engineer, supporting his family as a teenager after his father’s death, and eventually becoming a foreman in the tinsmith department of the Milwaukee and LaCrosse Railroad by the age of 26. During the Civil War, he returned to Chicago and co-founded the firm of Cross, Dane & Westlake, which focused on the manufacture of a revolutionary new “removable globe lantern” and other railroad supplies of Westlake’s own invention.

A native of Cornwall, England, Westlake (b. 1831) had come to America with his family as a kid in the 1840s, first settling in Chicago, then Milwaukee. It was in Wisconsin that William found his niche as a metalworker and engineer, supporting his family as a teenager after his father’s death, and eventually becoming a foreman in the tinsmith department of the Milwaukee and LaCrosse Railroad by the age of 26. During the Civil War, he returned to Chicago and co-founded the firm of Cross, Dane & Westlake, which focused on the manufacture of a revolutionary new “removable globe lantern” and other railroad supplies of Westlake’s own invention.

While not a savvy East Coast businessman like Adams or Crerar, Westlake has significantly more to offer when it came to intellectual property. He would eventually collect upwards of 300 patents during his lifetime, and thanks largely to his massively popular lantern and stove designs, was something of a household name throughout the 1860s. He was also a familiar face in courts of law, where he repeatedly defended his inventions against challenges from gold-digging patent trolls.

Like Adams, Westlake lost his original firm’s Chicago plant in the Great Fire—although, critically, he managed to salvage the design specs and patterns for the vast majority of his inventions, and continued his business under the new banner of Dane, Westlake & Covert. Over the course of the rebuild, however, with the vulnerability of his enterprise now glaringly apparent, Westlake began to see the wisdom of consolidation, and took a meeting with J. McGregor Adams.

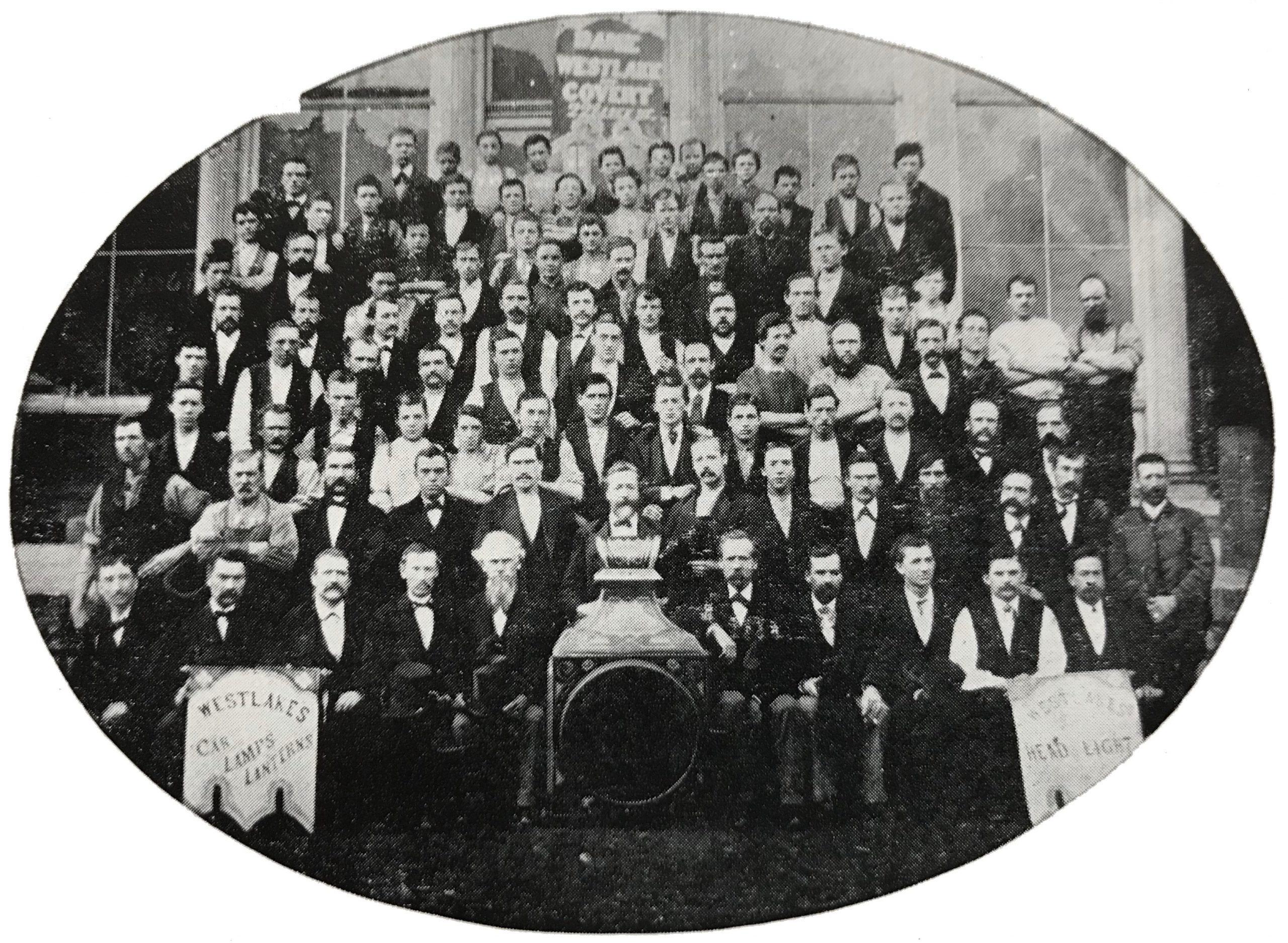

[Employees of Dane, Westlake & Covert, c. 1872, just before Westlake sold out to Crerar & Adams]

[Employees of Dane, Westlake & Covert, c. 1872, just before Westlake sold out to Crerar & Adams]

“You got some swell concepts, Willy,” Adams might have told his new buddy, “and Crerar and I have got the capital. When this city rises again, we could have the largest transportation hub in the country right in the palm of our hands.”

“Cool, cool,” said Westlake, and thus was formed, in 1874, the Adams & Westlake Company—a division of Crerar, Adams & Co.

An Industrial Proteus

On September 11, 1875, the Chicago Tribune published a rather glowing profile of the city’s fastest growing rail supply conglomerate:

On September 11, 1875, the Chicago Tribune published a rather glowing profile of the city’s fastest growing rail supply conglomerate:

“Crerar, Adams & Co., the Union Brass Manufacturing Company, and the Adams & Westlake Manufacturing Company form altogether an industrial proteus, for the three concerns are really one and the same.”

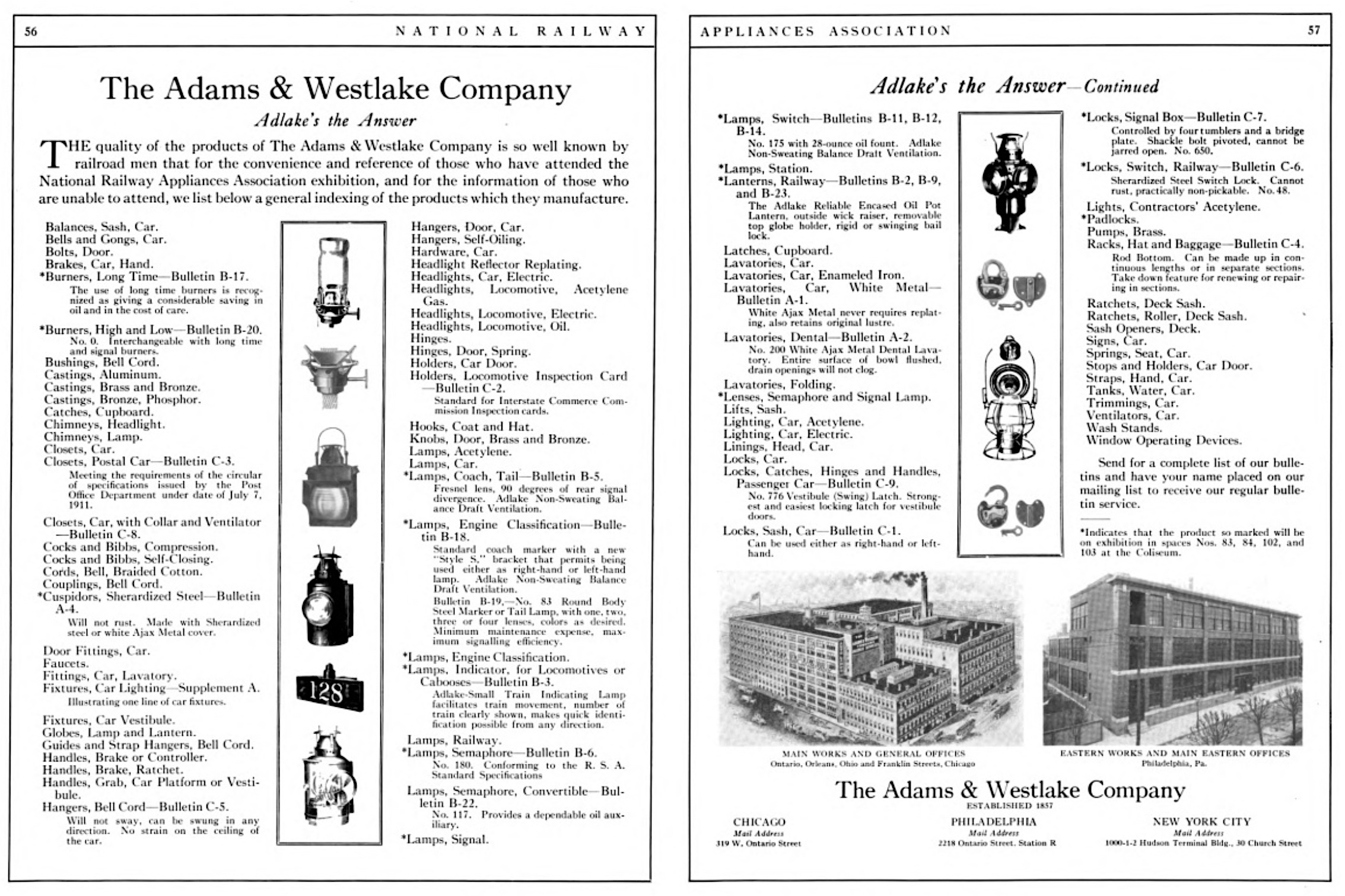

According to the report, Crerar, Adams & Co. was the “mercantile side of the industrial combination;” an enormous wholesale house that supplied “every necessary article for the construction, equipment, and operation of a railroad.” This ran the gamut from small iron and steel hardware to all of the interior fittings of the famous Pullman railcars: seats, water tanks, letter boxes, pull cords, sleeper car curtain rods, door locks, mirror frames, metal signs . . . even the very rails under the car’s wheels were often sold by the firm.

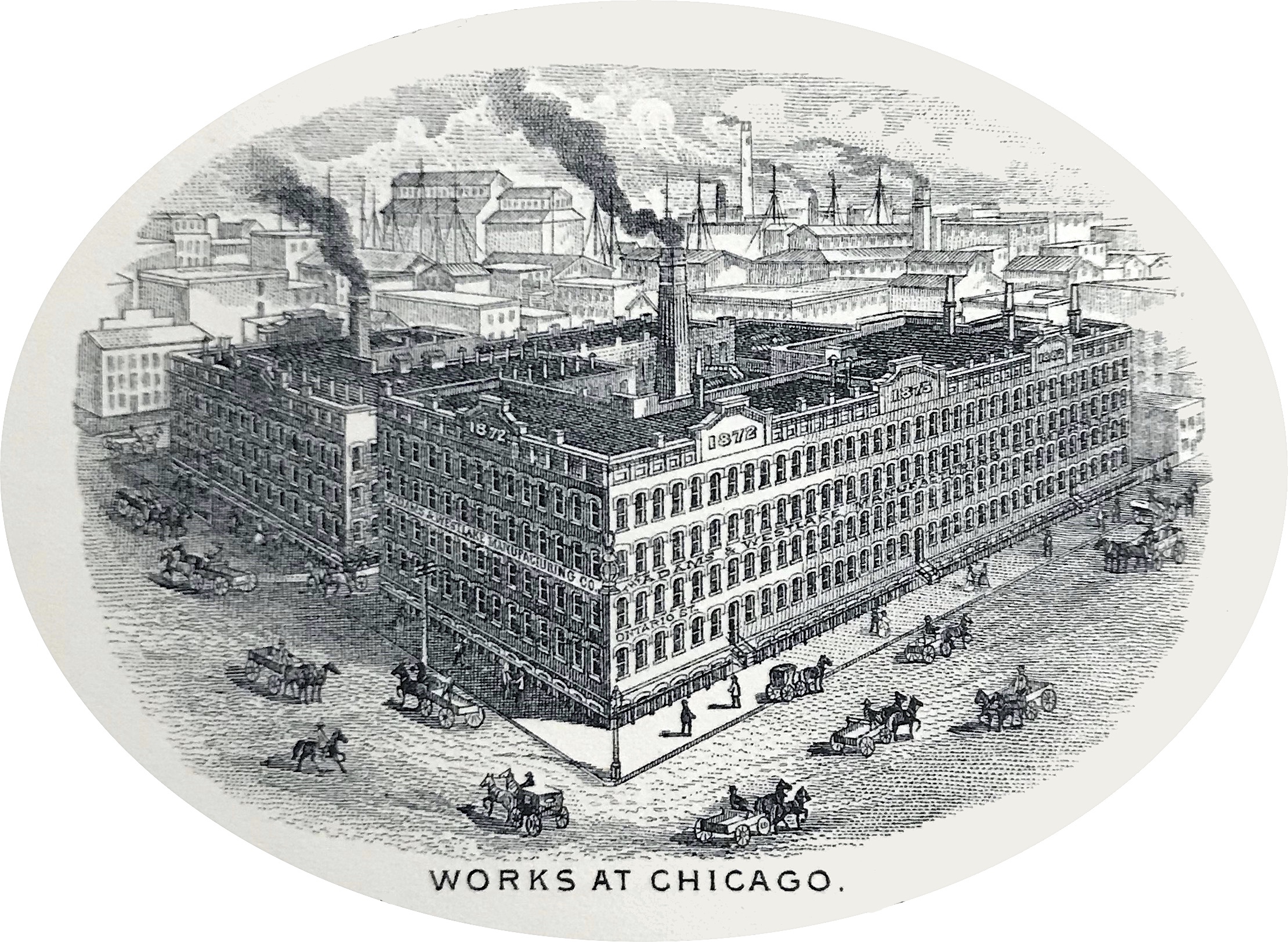

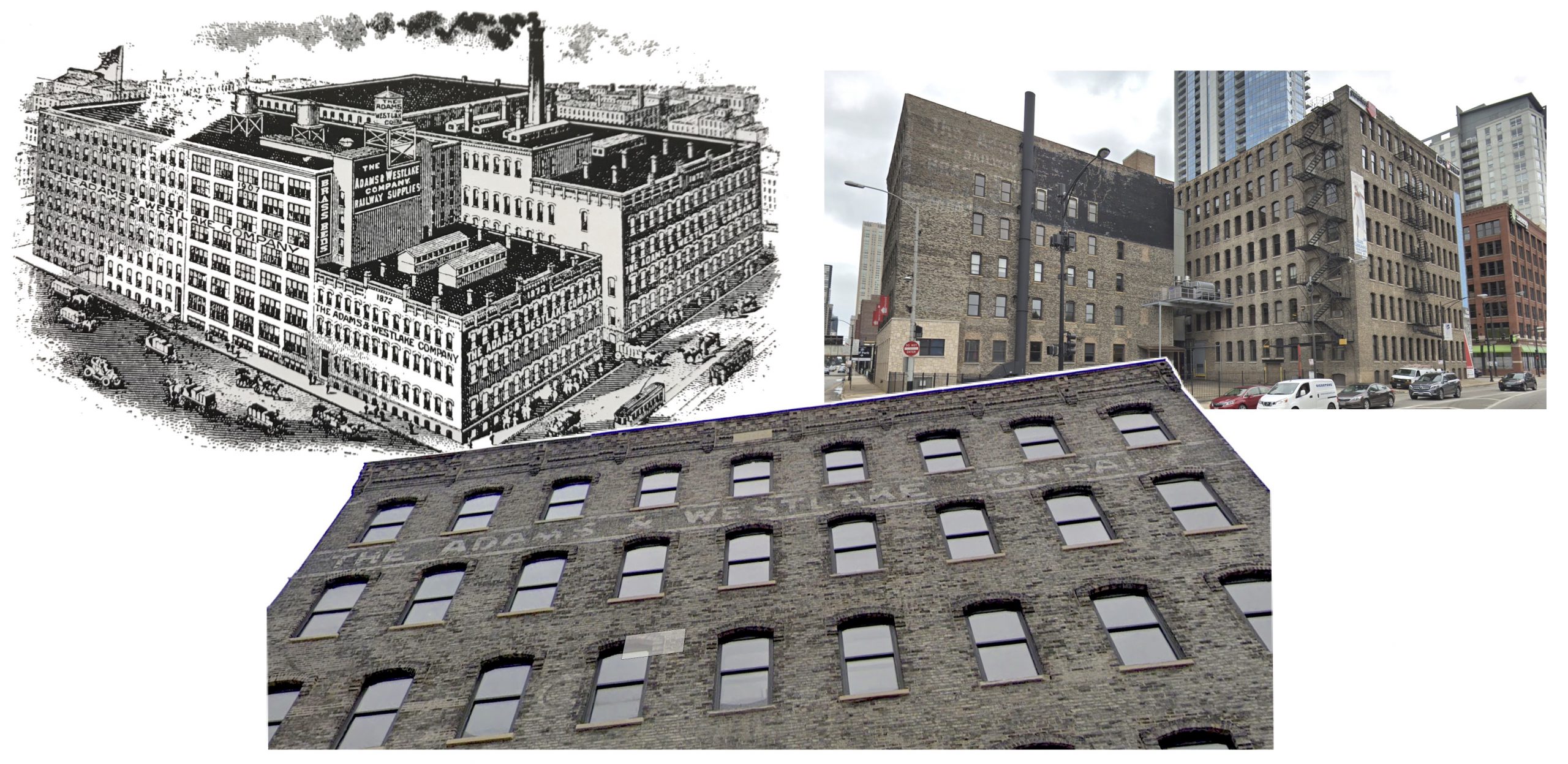

While much of Crerar & Adams’ stock was shipped in from the East Coast, their creation of the Union Brass MFG Co. and Adams & Westlake MFG Co. gave them a powerful in-house manufacturing operation of their own, as the two companies now occupied overlapping production works on the block between Orleans, Franklin, Ohio, and Ontario street.

“The present [Adams & Westlake] building was ready for occupancy only about ten days ago,” according to the 1875 Tribune article, “but the work-rooms are already full of operatives, and the store-rooms of burnished headlights, lanterns, tinware of every imaginable description, etc.

“One little item will give an idea of the extent of the business. The company makes and sells, every year, 100,000 stove boards alone. The figures showing the number of smaller articles manufactured are fairly incomprehensible. The mind cannot grasp them.”

I’m not sure if A&W’s output was legitimately too enormous for the human brain to process, but it was—at the very least—unusual for the time period. The post-war economy was still turbulent through much of the 1870s; another reason why many companies were forced to join forces in the first place—for survival. As the rebirth of Chicago and explosion of the railcar industry gained momentum into the 1880s, however, Adams & Westlake were soon full steam ahead—well, Adams was anyway. The enigmatic Mr. Westlake was a different story.

I’m not sure if A&W’s output was legitimately too enormous for the human brain to process, but it was—at the very least—unusual for the time period. The post-war economy was still turbulent through much of the 1870s; another reason why many companies were forced to join forces in the first place—for survival. As the rebirth of Chicago and explosion of the railcar industry gained momentum into the 1880s, however, Adams & Westlake were soon full steam ahead—well, Adams was anyway. The enigmatic Mr. Westlake was a different story.

Growing weary of the whole industrialist lifestyle, Westlake bowed out of the booming business by 1885, leaving behind his many patents as well as his name on the company banner. He had earned a not-so-small fortune as a celebrated purveyor of light and heat, but from the sounds of it, he was a bit embittered by the whole Adlake experience, claiming he never even made 1-percent of what others did off his inventions. “I sold my stove board for $100,000,” he later told the Milwaukee Sentinel, “and the manufacturers make that much every year out of it.”

Westlake would spend his later years in Brooklyn, NY, designing and sailing yachts and generally shunning the corporate world in favor of more creative pursuits. He died of Brights Disease just after Christmas, 1900.

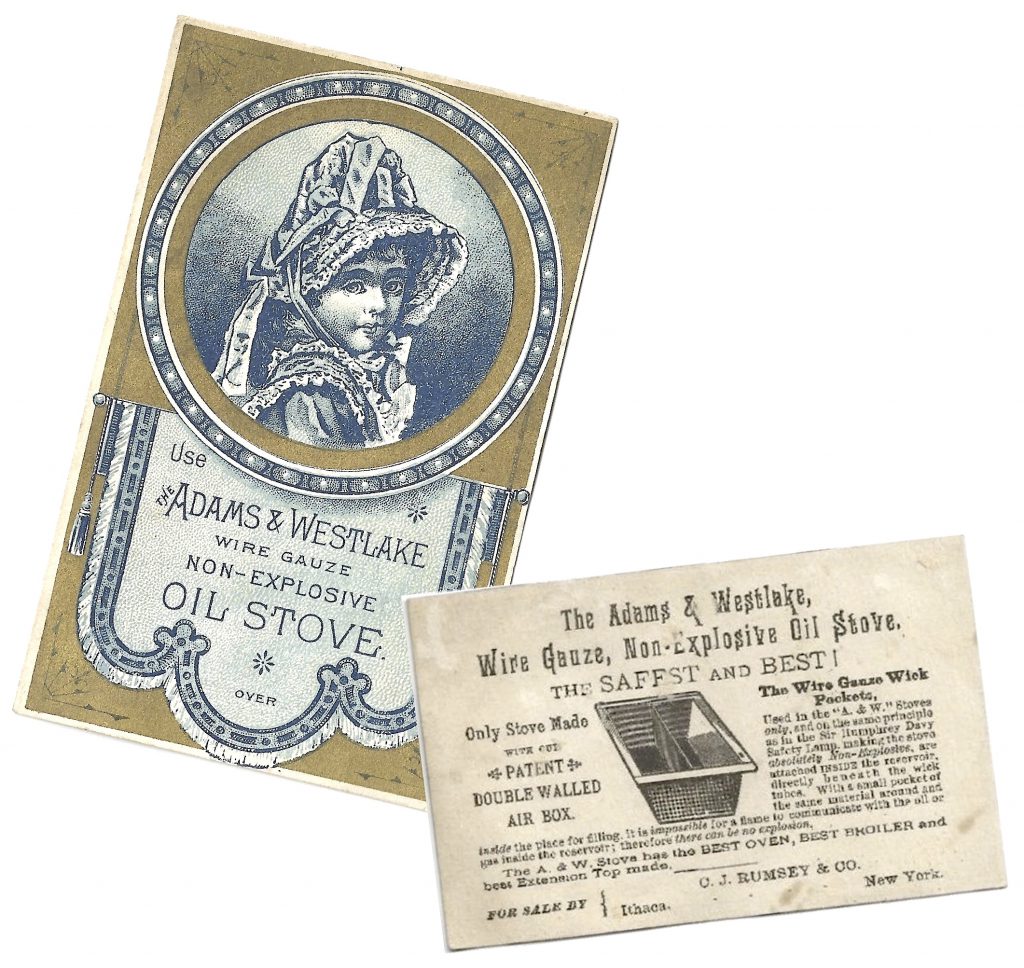

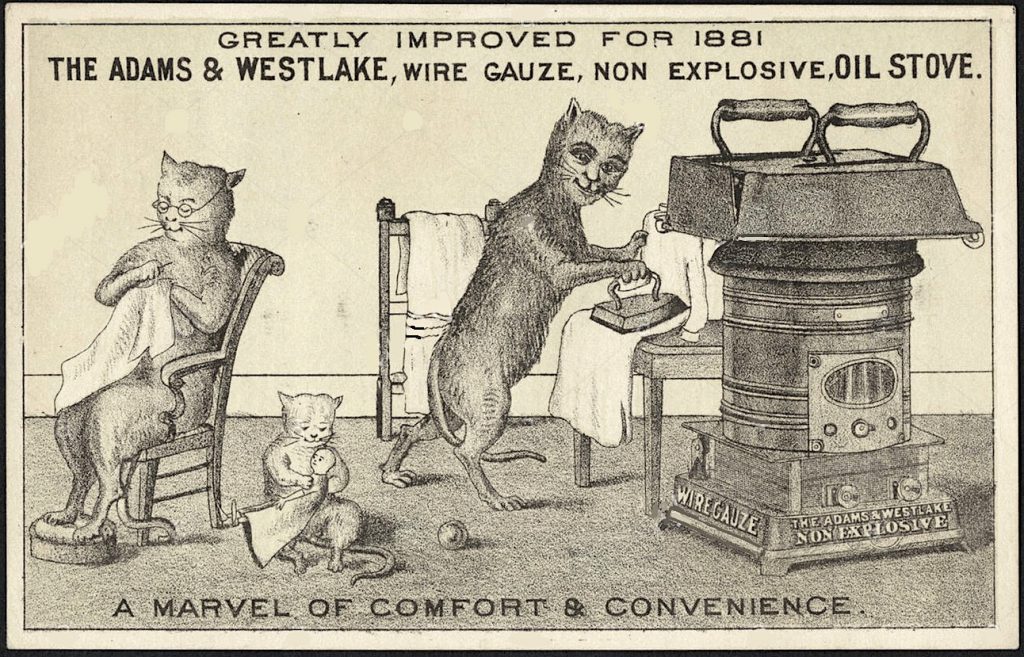

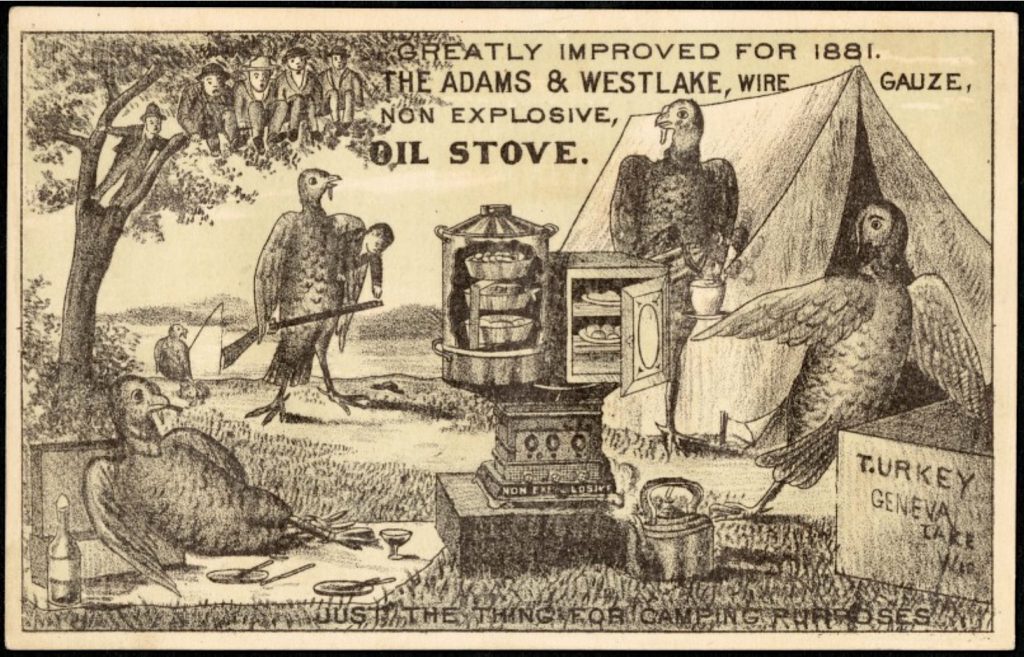

[Two examples from a very weird set of anthropomorphized animal promo cards that Adams & Westlake released in 1881 to market their non-explosive oil stove]

Adams After Westlake

So, while William Westlake’s stoves and lanterns certainly became the first iconic staples of the Adlake brand, the man himself was really only an active participant in the business for about 10 of its 160 years. The true “bro-mance” of this story, it turns out, was that of J. McGregor Adams (who served nearly a half century in the company) and his original partner from the beginning, John Crerar.

Together, these chummy tycoons—leading members of the private, high-society “Chicago Club”—continued to run both Crerar, Adams & Co. and Adlake after Westlake’s departure. And when Crerar died somewhat unexpectedly in 1889, aged 62, Adams still kept both companies running under the same names.

“He was a high-souled generous man,” Adams said of the late Crerar, “liberal in all things, and one whose friendship was a thing to be prized and be proud of. He was a philanthropist of the noblest type and did a wonderful amount of good in a quiet way. For twenty-five years he and I have been business partners and during that long period we never had a quarrel or dispute in any way. To his employees he was always the same; pleasant, genial, approachable.”

“He was a high-souled generous man,” Adams said of the late Crerar, “liberal in all things, and one whose friendship was a thing to be prized and be proud of. He was a philanthropist of the noblest type and did a wonderful amount of good in a quiet way. For twenty-five years he and I have been business partners and during that long period we never had a quarrel or dispute in any way. To his employees he was always the same; pleasant, genial, approachable.”

Adams, for his part, seemed pretty well liked in his day, as well. eventually remembered in the pages of The Railway Age as a “true gentleman at heart” and a “high-minded, generous, public-spirited citizen.”

He also wasn’t shy about expressing himself, and by doing so, his supposed “high-mindedness” often reveals itself to be fairly typical of the time period.

In August of 1888, at a time when little more than a dozen of A&W’s 600 employees were female, Adams told the Chicago Times that factory training could be good for girls—so long as they used the experience more as preparation for life as a wife and mother. Asked separately about immigrant workers taking American factory jobs, he noted that “pauper immigration is undoubtedly [a menace], and it should not be permitted to come in contact with skilled labor and degrade it.”

Just a few months later, when the A&W plant was robbed of $4,500 by a rogue employee, Adams discussed it with the Tribune in the style of an insult comic. “The police think they will get him, and I don’t doubt that they will,” he said of the culprit, Thomas Vines. “That nose of his is a prominent feature. The boys in the office called him ‘Nosey.’”

Physically, J. McGregor Adams had quite a few distinguishing characteristics of his own.

In the spring of 1889, when he was called to testify in a high-profile murder trial (his own philandering nephew Harry King had been gunned down by a heartbroken lover in an Omaha hotel), Adams—on the witness stand—was described in the Omaha Daily Bee as a “rather attractive looking gentleman. He has an intelligent face, large nose, double chin, and small snow white mustache. The top half of his head is entirely devoid of hair. What little hair he has left is confined to a bunch at the back part of his head, and is kept trimmed close down. He is six feet tall, straight and inclined to corpulency. Mr. Adams gave his testimony very deliberately and in a tone that could easily be heard all over the courtroom.”

In the spring of 1889, when he was called to testify in a high-profile murder trial (his own philandering nephew Harry King had been gunned down by a heartbroken lover in an Omaha hotel), Adams—on the witness stand—was described in the Omaha Daily Bee as a “rather attractive looking gentleman. He has an intelligent face, large nose, double chin, and small snow white mustache. The top half of his head is entirely devoid of hair. What little hair he has left is confined to a bunch at the back part of his head, and is kept trimmed close down. He is six feet tall, straight and inclined to corpulency. Mr. Adams gave his testimony very deliberately and in a tone that could easily be heard all over the courtroom.”

While partially there to defend his late nephew’s character, Adams (whom the Daily Bee further described as an “unusually entertaining witness”) also claimed an affection for the defendant / murderess, Elizabeth Biechler, whose case had divided much of the country on a Victorian moral conundrum: is it okay to kill a man who’s a deadbeat and a cheat?

“We have no desire to be hard on that woman,” Adams told a reporter, noting his own heartfelt attempts to help Biechler financially after his nephew had first abandoned her. “The three times I met her she acted very lady-like, and, speaking for myself, I have no desire to be hard on her.”

In the end, Adams wasn’t the only one sympathetic to the scorned woman. While Biechler was acknowledged as the killer of Harry King, she was still found not guilty of murder by the jury, and was set free to huge “bursts of applause” from a crowded courtroom—a pretty remarkable insight on the ethical pecking order of the times. “If a man thinks he can trifle with a woman’s honor without danger to his own carcass, such cases as this prove that he is wrong in his thinking,” the Columbus Journal (of Nebraska) reported.

All things considered, 1889 was not a great year for J. McGregor Adams. His murdered nephew was deemed worthy of his own slaying, and his good friend and business partner Crerar died a few months later, leaving the future of two enormous enterprises in Adams’ hands. Rather than cowering under the pressure or playing it safe, though, Adams seemed to open the playbook again, moving the Adlake brand into some previously uncharted territory, including major production of brass bed frames and bicycles (with specialized bicycle lamps to go with them). The ADLAKE line of bikes was eventually acquired by the Great Western MFG Co. of LaPorte, Indiana, but the respected name brand was retained into the early 20th century.

All things considered, 1889 was not a great year for J. McGregor Adams. His murdered nephew was deemed worthy of his own slaying, and his good friend and business partner Crerar died a few months later, leaving the future of two enormous enterprises in Adams’ hands. Rather than cowering under the pressure or playing it safe, though, Adams seemed to open the playbook again, moving the Adlake brand into some previously uncharted territory, including major production of brass bed frames and bicycles (with specialized bicycle lamps to go with them). The ADLAKE line of bikes was eventually acquired by the Great Western MFG Co. of LaPorte, Indiana, but the respected name brand was retained into the early 20th century.

As the “Gay ’90s” began, Adams & Westlake was a manufacturing firm of “world wide celebrity,” according to the 1891 guide book, Chicago: the Marvelous City of the West. “The Adams & Westlake Company [which had since absorbed the Union Brass Co.] employs from 900 to 1,000 men. The buildings in the block range from one story to seven stories in height, and have an aggregate floor space of 250,000 square feet. Included in their plant is one of the largest brass foundries in the country, having more furnaces, though using smaller pots, than any other concern. Their products are sent to every state in the Union, and exported all over the world.”

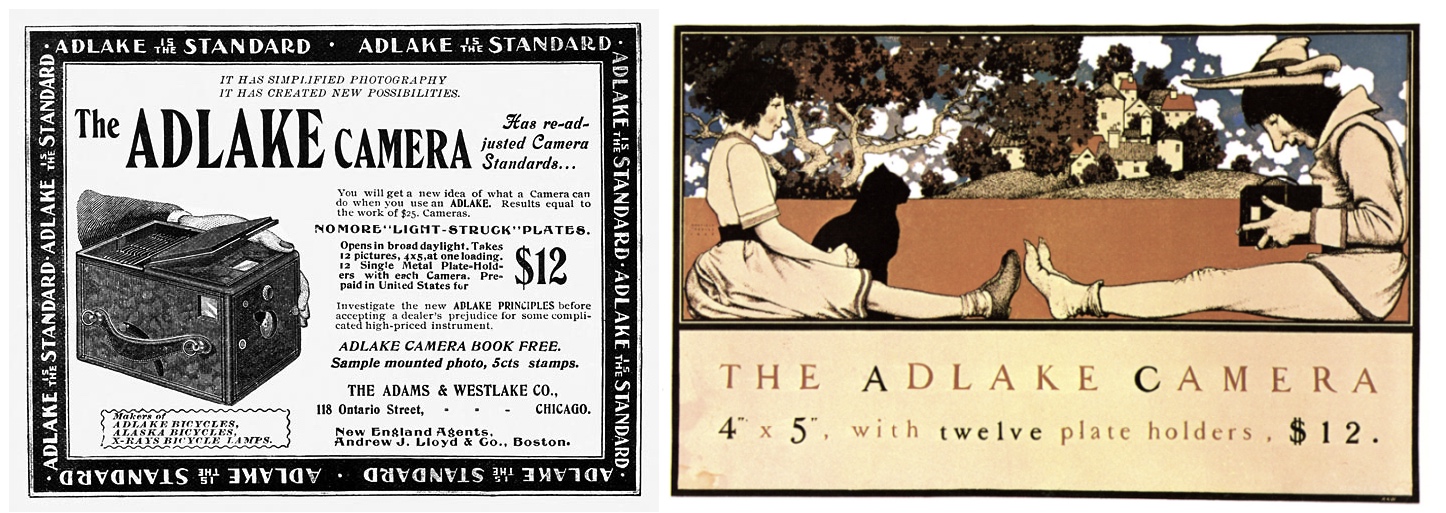

Lamps, lanterns, stove boards, and railroad car trimmings were still the company’s bread and butter, but perhaps inspired by the great innovations seen at the Columbian Exposition, the company continued an aggressive diversification as the century came to a close; introducing, among other things, the ADLAKE camera—another heavily promoted item that ultimately fizzled out.

House of Willits

After the death of J. McGregor Adams in 1904, A&W’s 45 year-old vice president and manager Ward W. Willits ascended to the president’s office. Today, Willits’ name is remembered largely for architectural reasons. His family’s home in Highland Park, built in 1902, is a historic landmark—one of the first Prairie style homes designed by Frank Lloyd Wright.

Within the Chicago Adlake story, though, Willits is a huge presence on his own merits; the man who led the business deep into the 20th century while carrying over the lessons he’d learned from its founder (Willits was a pallbearer at Adams’ funeral and named his own son “MacGregor”).

Within the Chicago Adlake story, though, Willits is a huge presence on his own merits; the man who led the business deep into the 20th century while carrying over the lessons he’d learned from its founder (Willits was a pallbearer at Adams’ funeral and named his own son “MacGregor”).

“We stand behind every article of our products,” Willits wrote in the Magazine of Business in 1906, “and if a complaint is made by a customer which seems reasonably just, we do not try to evade or delay giving him satisfaction. That was the policy adopted by the founders of the firm when it was first incorporated in 1867, and although the original proprietors have long since ceased to manage the company, the foundation policy has always remained the same.

“. . . On the whole, liberality pays. If you put the best material into your product, hire the most skilled labor, sell your goods for the lowest possible price, consistent with quality, and stand ready to make good any defects, you are building up a reputation that will become a valuable asset.”

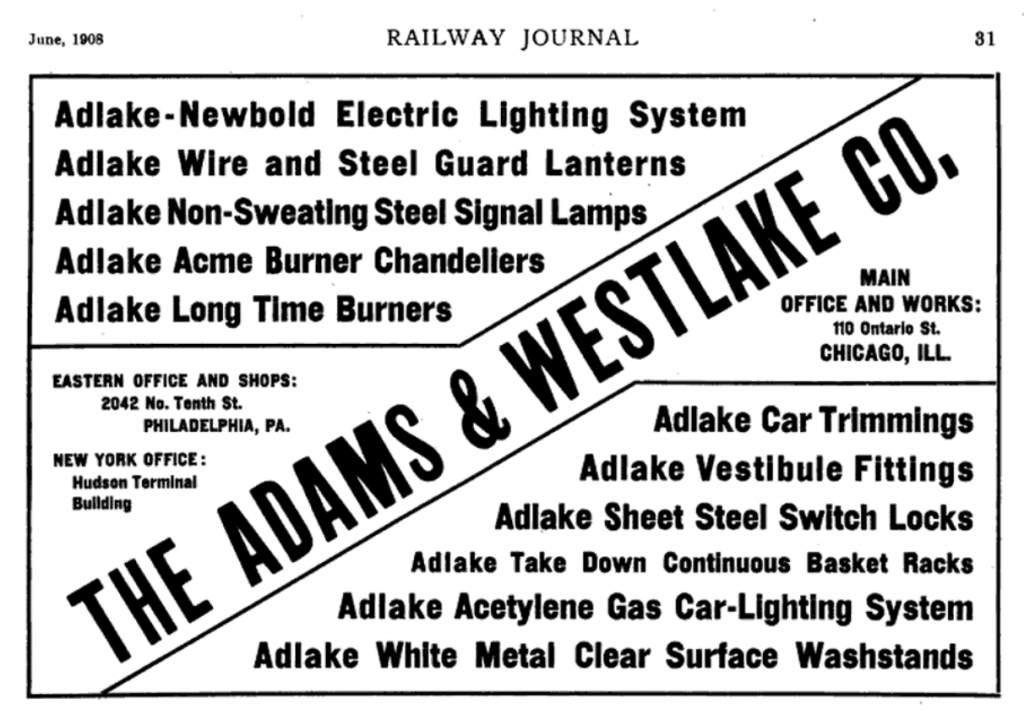

Under Willits’ watch, ADLAKE (which by now also had facilities in New York and Philadelphia) went back to focusing on the transport industry, while also evolving to meet its new demands. This included the development of a self-contained acetylene gas lighting system for railcars (when oil light became less fashionable); followed by the ADLAKE-Newbold electrical system, which included an individual axle-driven generator and voltage regulator to bring an electrical current to each car.

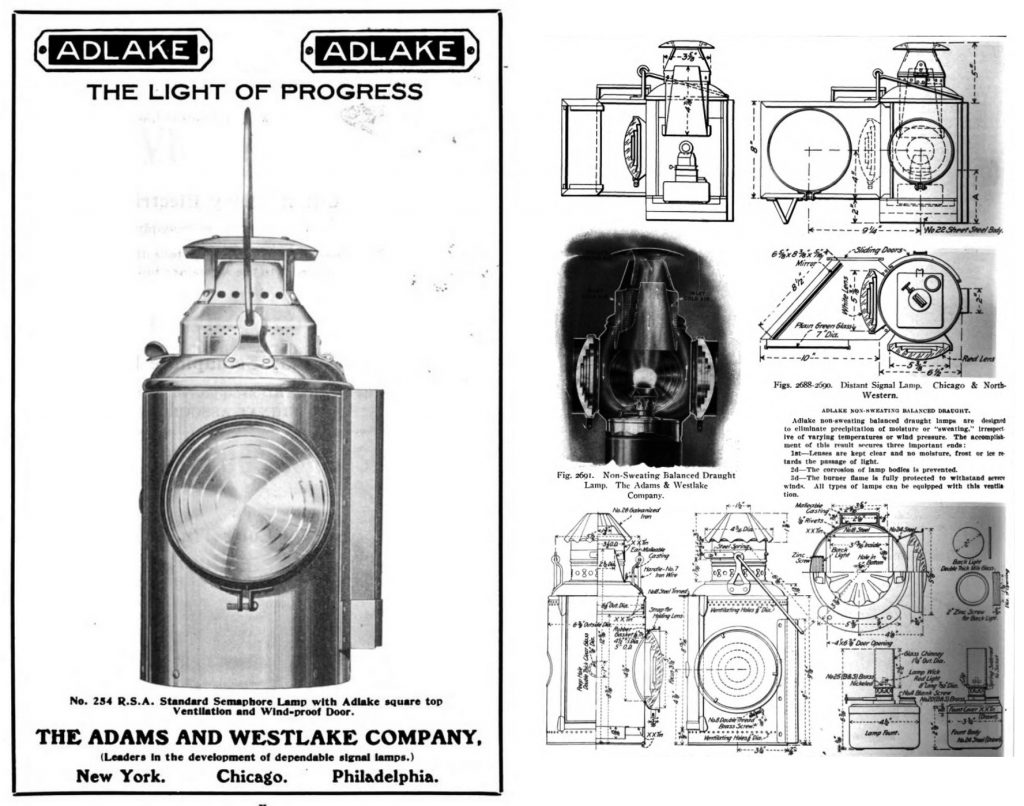

The ADLAKE-Newbold system was later introduced to motor cars, too, but up through World War I and beyond, more traditional oil lamps remained quite common on the open roads, as well as the railroads. These early 20th century signal lanterns were often called “non-sweating” lamps, which meant they were “designed to eliminate precipitation of moisture or ‘sweating,’ irrespective of varying temperatures or wind pressure.” This kept lenses clear and shining through; reduced corrosion of the lamp bodies; and protected the burner flame from high winds.

The ADLAKE-Newbold system was later introduced to motor cars, too, but up through World War I and beyond, more traditional oil lamps remained quite common on the open roads, as well as the railroads. These early 20th century signal lanterns were often called “non-sweating” lamps, which meant they were “designed to eliminate precipitation of moisture or ‘sweating,’ irrespective of varying temperatures or wind pressure.” This kept lenses clear and shining through; reduced corrosion of the lamp bodies; and protected the burner flame from high winds.

In some ways, ADLAKE was almost too good at making lanterns. Their connection to that product and other railway supplies may have hindered the public’s willingness to try out their aforementioned beds, bikes, and cameras, all of which were discontinued before World War I. During the war itself, “ADLAKE devoted all surplus capacity, above the needs of the transportation industry, to production of specialties for the use of the United States Army and Navy,” according to the company’s own 100th anniversary booklet from 1957. “In addition to the lamps for motor trucks there were hand lanterns, timers for shells, and hardware for naval vessels and ships for the Emergency Fleet Corporation. At the close of the war . . . when shipbuilding declined and many yards closed, the ADLAKE plant in Philadelphia was sold and its production transferred to Chicago.”

That might have meant a few more local jobs for returning soldiers in Chicago, but as the 1920s loomed, Willits and his associates knew they were getting squeezed for space in the Ontario Street complex, some buildings of which now dated back 50 years.

[Top Left: Adams & Westlake complex c. 1915, Top Right: Remaining buildings still standing today. Bottom: Closer view of the top of the ADLAKE office building at 319 W. Ontario Street, where the company name can still be seen in faded ghost signs]

[Top Left: Adams & Westlake complex c. 1915, Top Right: Remaining buildings still standing today. Bottom: Closer view of the top of the ADLAKE office building at 319 W. Ontario Street, where the company name can still be seen in faded ghost signs]

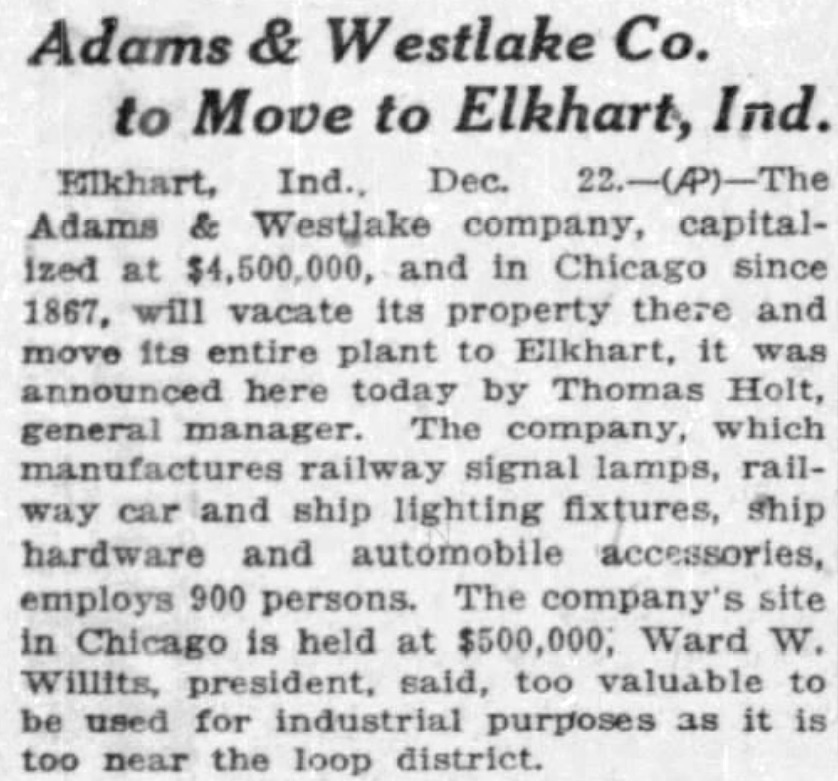

In 1923, one of ADLAKE’s sister companies, the Curtain Supply Co., relocated to Elkhart, Indiana. And when a new, state-of-the-art plant was proposed in that town, Adams & Westlake agreed to merge with Curtain Supply and re-locate entirely, closing its Chicago works for good—save for the corporate offices inside the Adlake Building at 319 Ontario (which remained in use up through Willits’ death in 1950).

From Willits’ perspective, it was no longer viable to have a major manufacturing operation so close to the Loop, and by going to Elkhart, he’d have more square footage, modern amenities, and best of all, cheaper rent. It was the same path that had led other big manufacturers like the Chicago Telephone Supply Co. to uproot and settle in Elkhart years earlier.

From Willits’ perspective, it was no longer viable to have a major manufacturing operation so close to the Loop, and by going to Elkhart, he’d have more square footage, modern amenities, and best of all, cheaper rent. It was the same path that had led other big manufacturers like the Chicago Telephone Supply Co. to uproot and settle in Elkhart years earlier.

Unfortunately, Adlake still employed 900 Chicagoans at the time of its move in 1927, and while some migrated with the business to Elkhart, many others were out of work. Any future innovations from the railway appliance kings would have to come from the Hoosier State.

Adlake Legacy

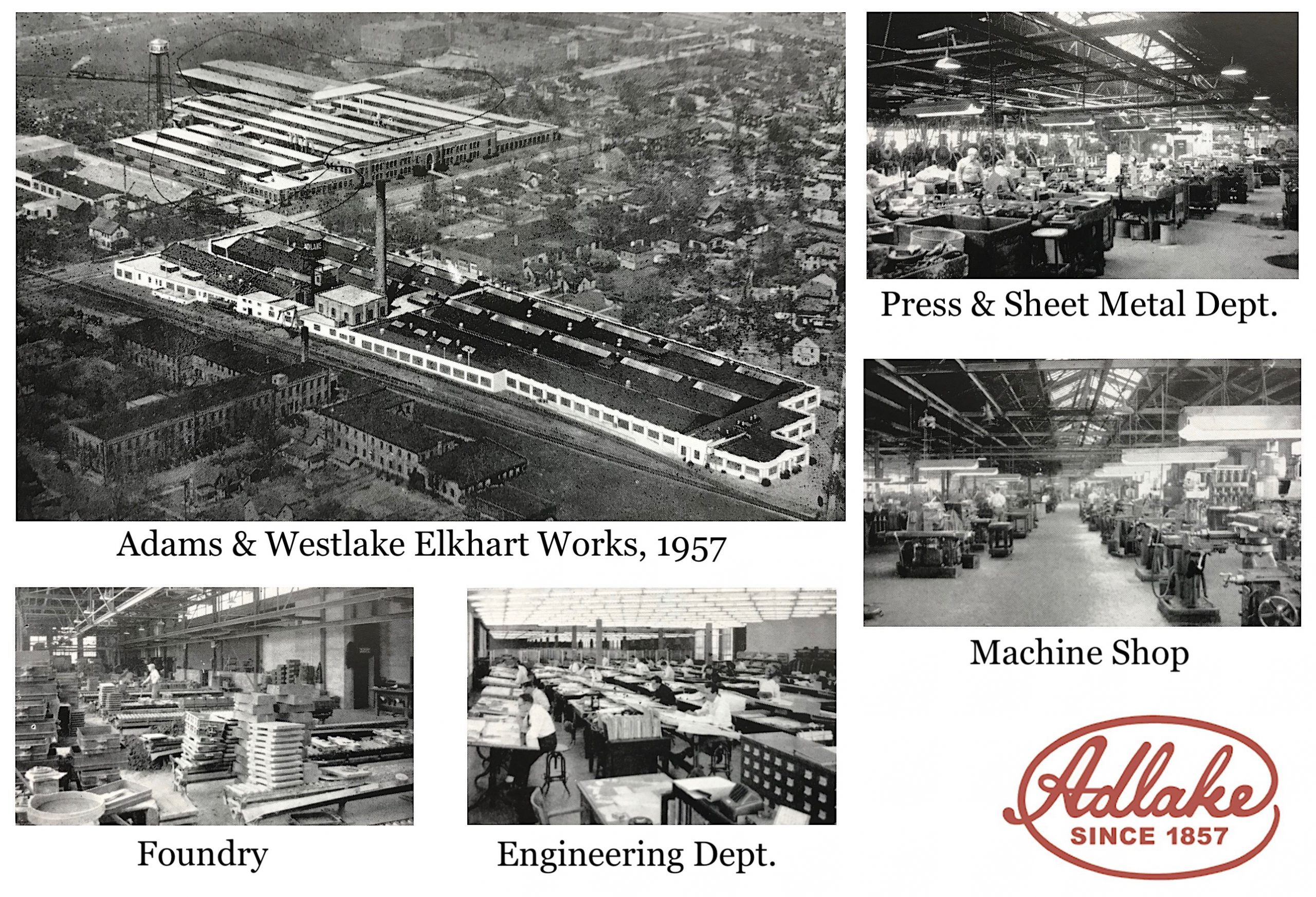

At the expense of just yadda-yaddaing the more recent 90 years of company history, we can at least tip our hats to Adams & Westlake’s staying power. The company ultimately survived the Great Depression, another world war, and several more tsunami-like new waves in transportation tech during its Elkhart years.

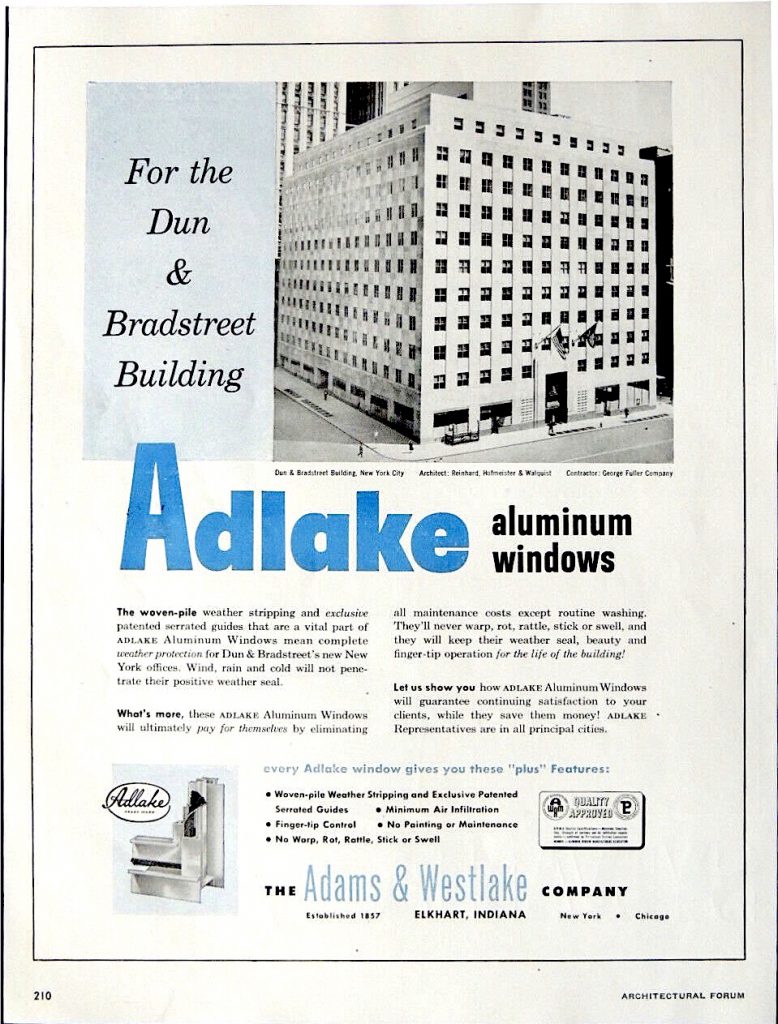

After World War II, they pivoted from window curtains into aluminum window sashes for both railcars and modern buses; then started producing window parts for buildings. Electric relays and new types of car parts were added, as well.

Compared to the bustling conglomerate that once ran a whole city block in downtown Chicago, the current iteration of Adams & Westlake Co. is . . . different. After a long association with the company starting in the 1960s, Dave Elmore sold the business to his son D.G. Elmore in the late 1990s, who then partnered with new company president Randy Schneider in the 2000s.

Compared to the bustling conglomerate that once ran a whole city block in downtown Chicago, the current iteration of Adams & Westlake Co. is . . . different. After a long association with the company starting in the 1960s, Dave Elmore sold the business to his son D.G. Elmore in the late 1990s, who then partnered with new company president Randy Schneider in the 2000s.

By the time Adlake had reached 150 years in the industry, their workforce in Elkhart had dwindled down to just 36, utilizing a 62,000 sq. ft. plant. But, as specialists still connected to the railway industry, they had settled into a solid niche. In 2009, Scheider told the South Bend Tribune that “business is going strong,” adding that ADLAKE had diversified into the RV and military markets, making everything from lock hardware and sun visors to luggage racks, curtains, and windows. More to our interests, they also still make reproduction versions of classic ADLAKE lanterns (about 1,000 per year as of ’09), often made with the same tooling as the old days. A few of these might end up at historic railway stations, while most become gifts or novelties for the old-timey minded.

As of 2019, according to Adlake’s corporate Facebook page, the company has still retained many of the records and blueprints from their early days; a good sign that its history, for now, is in good hands.

SOURCES:

Adlake Website: Adlake.com

Pittsburgh Auto Equipment Co. Catalogue No. 7, 1920

“Adams & Westlake Celebrating 150 Years of Service” – South Bend Tribune, Feb 23, 2009

Biecher murder trail verdict – Columbus Journal (Columbus, NE), April 17, 1889

ADLAKE: 1857-1957, 100 Years of Service to American Industries, 1957

“Dissolution of the firm of Jesup, Kennedy & Co.” – Chicago Tribune, July 15, 1867

“Crerar, Adams & Co” – Chicago Tribune, September 11, 1875

“John Crerar” – The University of Chicago Biographical Sketches, 1922

“City Slave Girls: Opinions of Prominent Men on How to Remedy the Great Evils of Female and Child Labor” – Chicago Times, Aug 21, 1888

“Profit in Little Things: A Successful Inventor Tells What He Has Found Most Advantageous” – Milwaukee Sentinel, Dec 24, 1890

“Plant of American Stove Board Company to be Removed to Chicago Heights” – The Inter Ocean, Nov 27, 1898

“William Westlake Dead” – Chicago Tribune, Dec 29, 1900

“John Crerar: Industrialist, Bachelor Philanthropist, Library Founder” – ATLA.com

“How She Loved Him: The Story of Miss Biechler and Harry King Laid Bare” – Omaha Daily Bee, April 6, 1889

“A Strong Guarantee – Protected By System,” by Ward W. Willits, Magazine of Business, Vol. 10, 1906

“J. McGregor Adams Dies After a Long Illness” – Chicago Tribune, Sept 18, 1904

“Vines and Money Gone: Disappearance of an Adams & Westlake Company Clerk” – Chicago Tribune, Dec 30, 1888

The Railway Signal Directory, 1911

I am trying to find a good picture of the backup lights Adlake produced around 1945 used on the back of locomotive tenders.

What is the age difference from a railroad switch key that has the Adams & Westlake/Chicago oval and ADLAKE. I recently at auction purchased a Santa Fe switch key with the oval hallmark. Thank you.

I have an Adams and Westlake Co. Elkhart, IND. Mercury Wetted Contact switch, CAT. No MW54-16812, or at least that is what the number looks like, though it is difficult to read. Not sure if this is of interest, and not sure where it came from.

I have an Adams and Westlake Company Chicago lantern called “The Adams” that was my great,great grandfathers we think. He was an engineer in North Bay, Ontario, Canada. The glass has L.S.&M.S.R.y. molded into it. I dont know if it is a collectors item or not but I found this website and was looking for some more info on it. Thank you.

The l.s, & m.s.r. is the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway

I was operating from 1833-1914 so I would say it is a very rare piece you have.

I have an Adams-Westlake nickel plated library lamp . I would like to know more about it and part’s availability .

My wife just bought me one of your model 4435 lamps. Is there a way to tell how old it is? It also has a riveted loop type handle on top similar to your railroad lanterns but this does not fold down. I have not found a picture like this one yet. Can you explain to me what this type would be used for? I told the wife it probable is for when you have a flat you would have a light with a handle to change the tire or possible use it to unload the truck at night. Also where do I find a wick for it?

Thanks,

Joe

Hi. I have collected A & W railroad lanterns for more than 45 years. I read your article with much interest and admittedly at age 78 discovered things about their production I wasn’t aware of. However, I was very interested in doubt being raised about the establishment date for the company. I was not aware the date was being questioned but know for sure I own an Adams & Westlake oil fount with a patent date of April 26, 1864 and an Adams & Westlake railroad lantern with a clear patent date of December 12, 1865. It has other patent dates for September, October and November but I haven’t been able to make out the year. In any event this should establish a date earlier than April 26, 1864 for a business establishment date. I would be glad to provide pictures if you are interested. Thank you.

I have a awesome ADLAKE lamp would love to know what year was it in

I have an adams & westlake railroad lantern. On the top it has Chicago Elkhart New York. It also has W T Co. What does W T Co stand for?

W.T. Co stands for Washington Terminal Company, the company that operated the Washington D.C. railroad passenger terminal.

S27102 can u tell me when it was made?

Also imprinted with Santa Fe. That for large

Truck or Santa Fe railroad? Has 4 lites

My husband has a set of what we believe are Adlake 4435 oil truck they have the original lenses from and back. I can not find any to compare for value. Can I send pictures?

I have a brass bed that is just 4 inches larger than full size made by The Adams & Westlake Co. Chicago USA. It has been in our family for over 60 years. There is nothing more than a mention the company made beds. Do you have more information?

My wife and I recently bought 2 lanterns that say Adams and westlake on them but they look brand new and we can’t find any info on them just wondering if you could help thanks Tommy Adams

The Company is still in business and still making the lanterns.

http://adlake.com/index.html