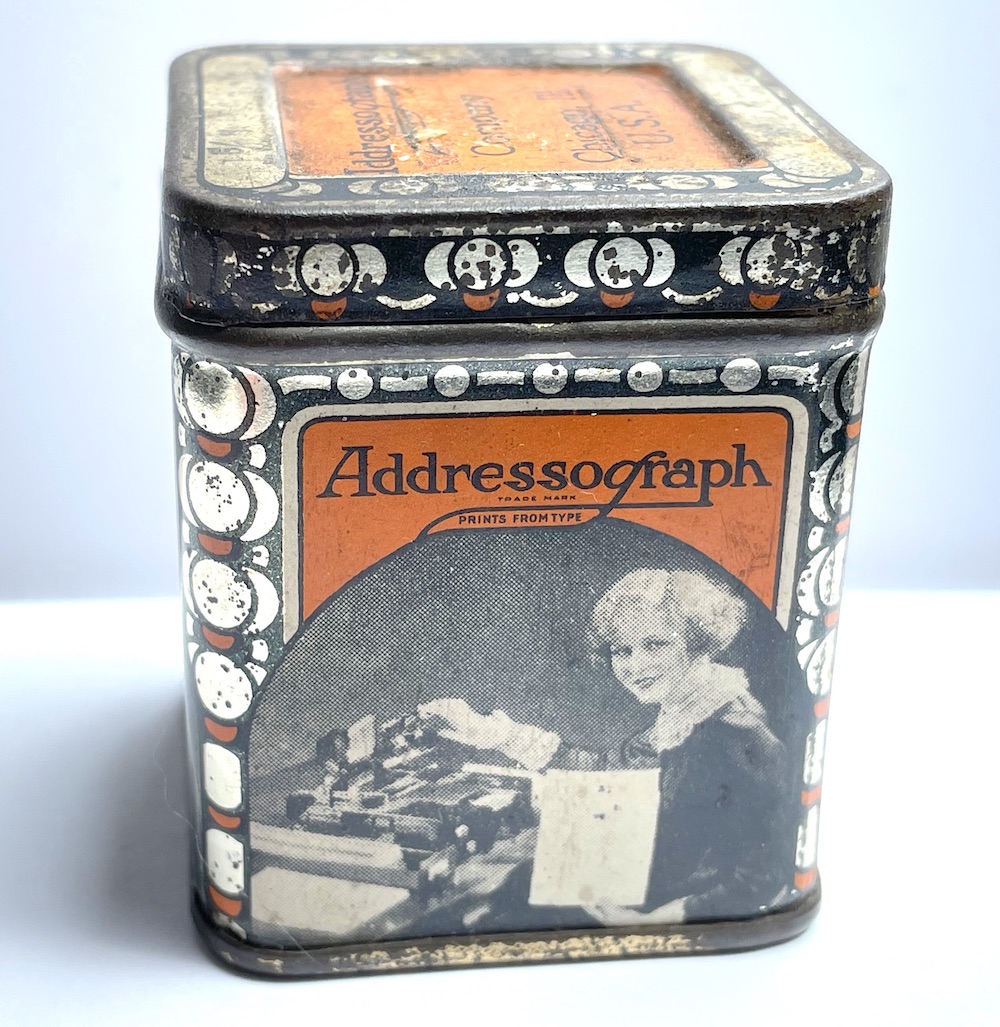

Museum Artifact: Addressograph Print Ribbon Tins, c. 1920s

Made by: The Addressograph Company, 915 W. Van Buren St., Chicago, IL [West Loop]

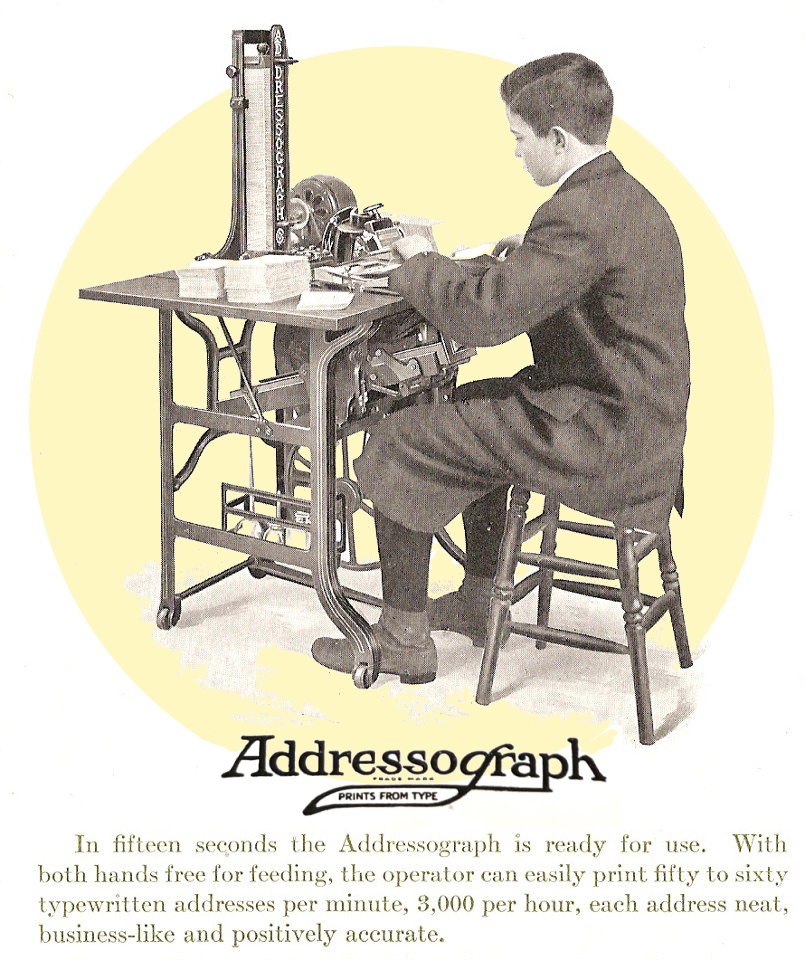

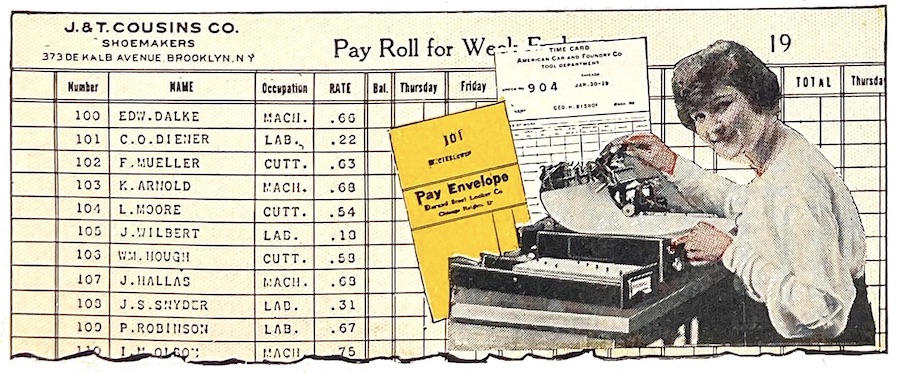

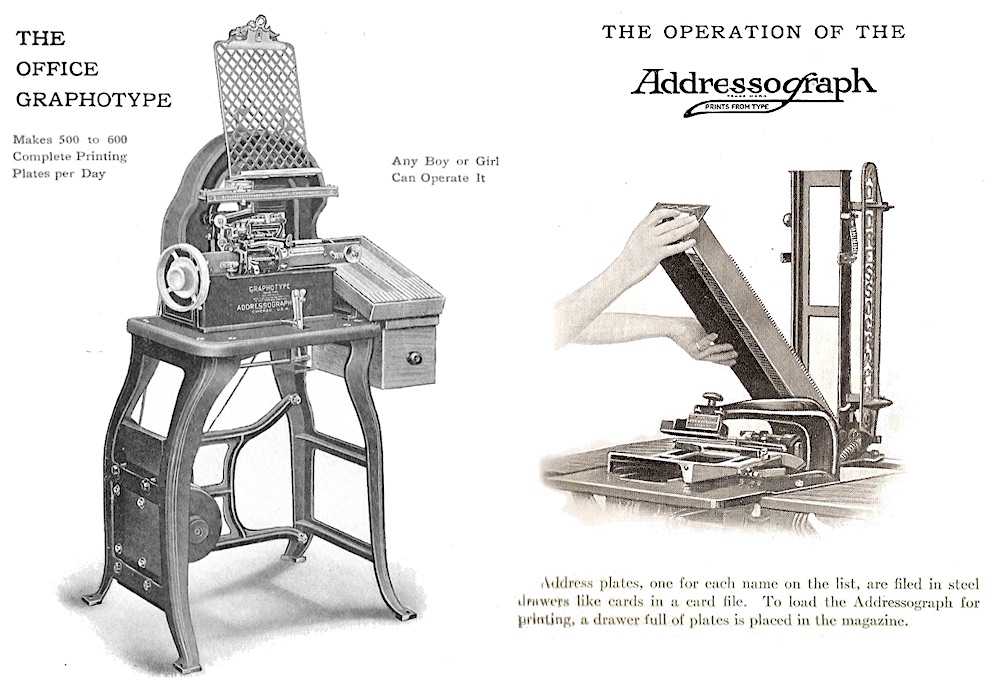

“If tomorrow morning the Addressograph were set down in your office, any sixteen year-old boy or girl in your employ could readily operate it and by noon be addressing envelopes, cards, statements, payroll forms, anything, everything, at the rate of 1,000 an hour. By night he would increase his speed to 2,000 pace, and by the next day would have acquired the average speed of 3,000 addresses an hour without the errors and omissions which are liable in the most careful hand work.” —Addressograph catalog No. 14, c. 1910

Though it may have looked like an unwieldy Rube Goldberg contraption, the Addressograph machine was a real turn-of-the-century godsend for America’s under-age office assistants, many of whom—judging by the excerpt above—were literally expected to work morning, noon and night if a company’s label-making needs required it.

Though it may have looked like an unwieldy Rube Goldberg contraption, the Addressograph machine was a real turn-of-the-century godsend for America’s under-age office assistants, many of whom—judging by the excerpt above—were literally expected to work morning, noon and night if a company’s label-making needs required it.

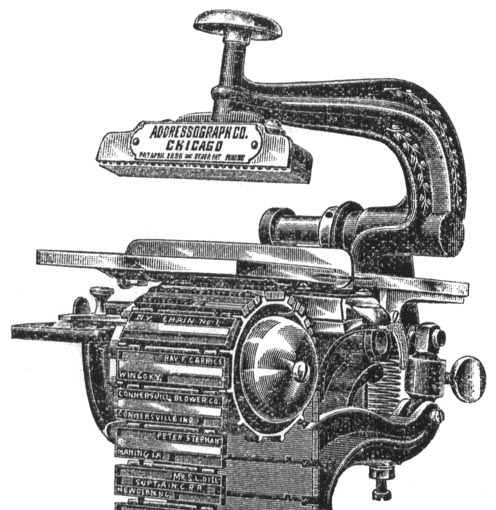

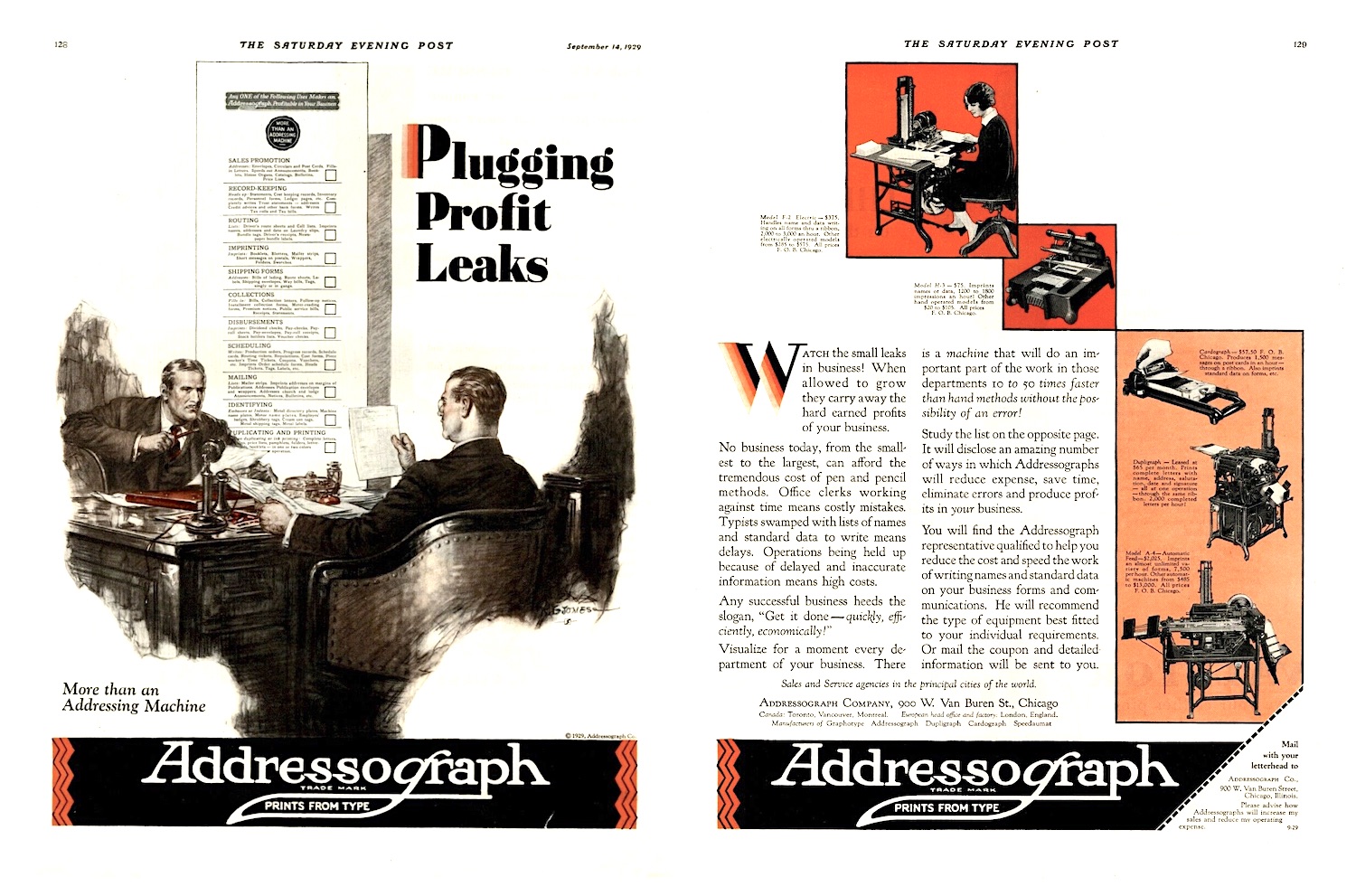

The device, first patented in 1896, was manufactured in Chicago for over 30 years (before production moved to Cleveland), and it went through dozens of iterations and evolutions over that time, spurring numerous related office innovations in the process.

Before the Addressograph and its sister product the Graphotype came along, business mailing lists were a gigantic hand-printed hassle. Afterward, mass mailings—from Sears catalogs to political flyers—could be handled with optimum temporal and clerical efficiency, thus “removing drudgery from the shoulders of brain workers,” as one sales sheet described it. As a less desirable consequence, perhaps, you could also credit the Addressograph for opening the door to the marketing revolution known as direct mail (or, in wider parlance, “junk mail”).

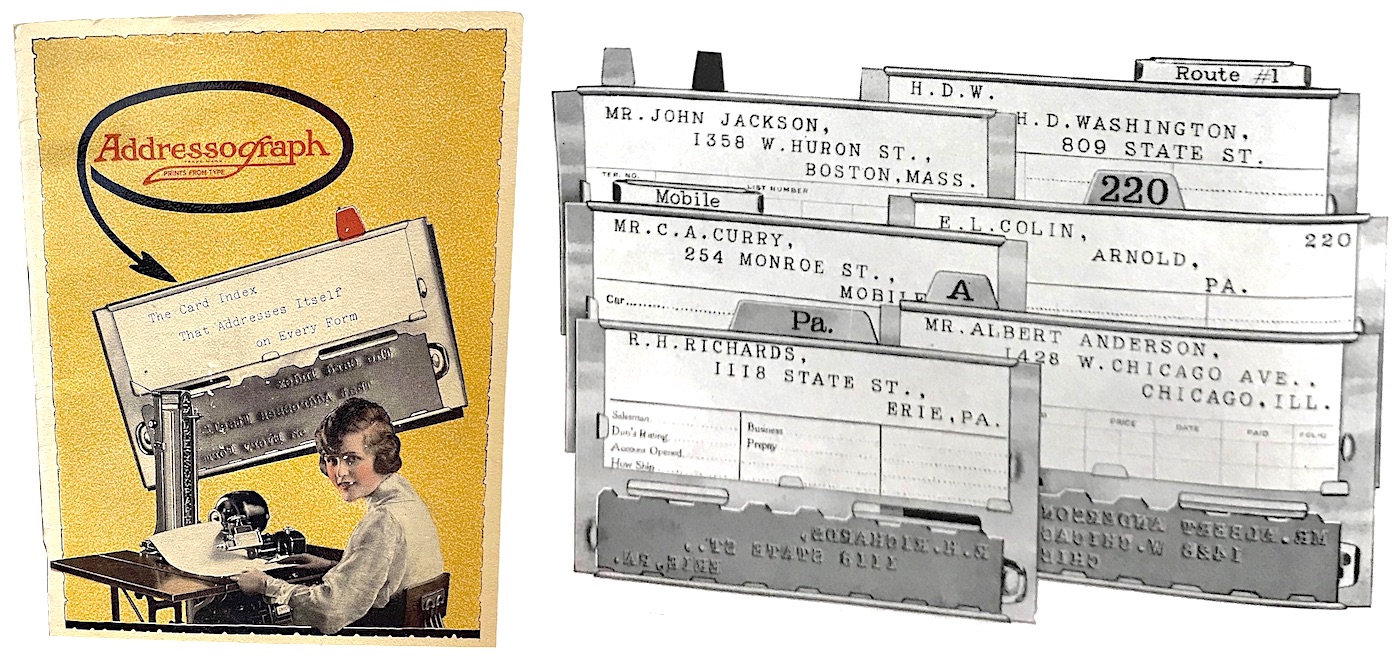

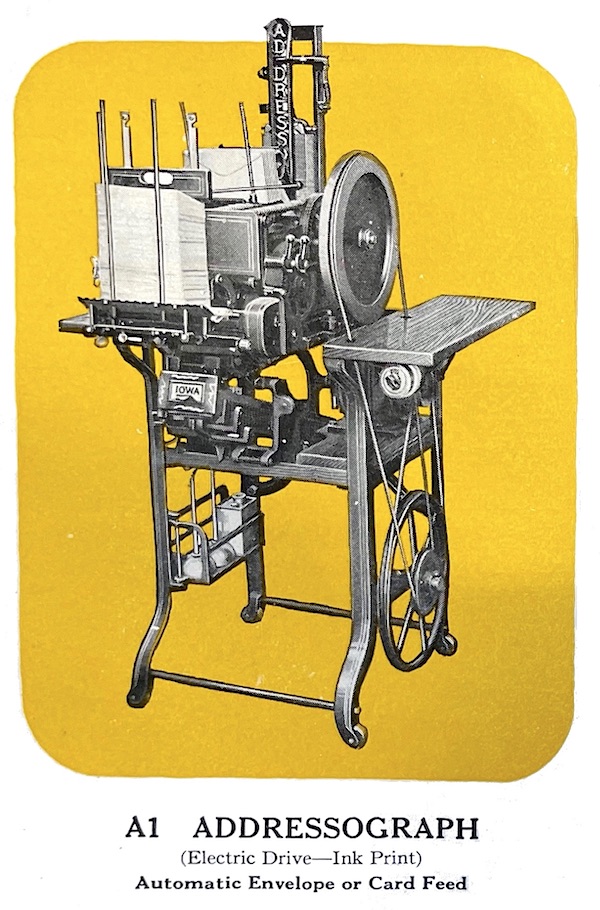

The Addressograph technology itself lands somewhere between that of a traditional printing press and “duplicators” like the Edison Mimeograph and Ditto machine (also both made in Chicago). First, using the Graphotype keyboard, the office worker would create an embossed metal card with a recipient’s name and address (this same technique was used for decades to make military dog tags). From there, the cards would be alphabetically sorted, like a library’s card catalog, in filing trays, which the Addressograph machine could then access; pulling each card in rapid succession and using a dab of ink from a ribbon to stamp the recipient’s info onto the next envelope.

[Addressograph Card-Index Address Plates]

Needless to say, new methods of doing this—without the plates, stamps, and storage cabinets—eventually came along; but maybe not as quickly as you’d think. Many of the same principles were still in use well into the 1960s, and the Addressograph brand itself was popular and prominent for just as many years as the Xerox machines that ultimately took its place.

The specific artifacts in our museum collection date back to the 1920s, and while the ornate design and smiling flapper girls might suggest some sort of Jazz Age jewelry box, each of these tiny 2″ tall tins functioned more like the printer ink cartridges of their day; stored away in desk drawers to ensure an office’s Addressograph machine would never run dry before a big mailing; or worse yet, before payroll day.

The specific artifacts in our museum collection date back to the 1920s, and while the ornate design and smiling flapper girls might suggest some sort of Jazz Age jewelry box, each of these tiny 2″ tall tins functioned more like the printer ink cartridges of their day; stored away in desk drawers to ensure an office’s Addressograph machine would never run dry before a big mailing; or worse yet, before payroll day.

Print ribbon tins like these were in circulation during the Addressograph Company’s most profitable years in Chicago, just before the retirement of inventor/founder J. S. Duncan marked the beginning of a big transition for the business. Duncan, who collected over 200 separate patents across his career, was a wealthy industrialist like plenty of others in Chicago at the time, but he was, above all else, a problem solver.

History of the Addressograph Company, Part I: The Angry Bookkeeper

Born in Pittsburgh, PA, in 1858, Joseph S. Duncan made his way West in the early 1890s, eventually landing a gig as a bookkeeper for the Great Northern Milling Company of Sioux City, Iowa. The work wasn’t particularly inspiring, but Duncan’s smoldering frustration with the inefficiency of that workplace would prove life-changing.

“Among other duties, I had to see that a number of flour price lists and bids for grain were sent out each day to a list of people with whom we regularly did business,” Duncan recalled in the 1918 compendium, Manufacturing and Wholesale Industries of Chicago. “This addressing was a tedious job. It used to keep one of the young men in the office busy most of the time. Every now and then one of these bids would go astray through a mistake in the address with the result that other milling companies would get the business. In a year’s time these losses amounted to a good deal of money. . . . I was much annoyed by this . . .

“Among other duties, I had to see that a number of flour price lists and bids for grain were sent out each day to a list of people with whom we regularly did business,” Duncan recalled in the 1918 compendium, Manufacturing and Wholesale Industries of Chicago. “This addressing was a tedious job. It used to keep one of the young men in the office busy most of the time. Every now and then one of these bids would go astray through a mistake in the address with the result that other milling companies would get the business. In a year’s time these losses amounted to a good deal of money. . . . I was much annoyed by this . . .

“I felt that there ought to be some way of addressing our cards mechanically, a way that would prevent mistakes and that would save most of the time and effort then wasted by the clerks in writing, over and over again, the same names and addresses.”

Duncan went in search of some sort of labeling machine to automate the process, but found nothing. Shortly thereafter, in the spring of 1893, a collapse in the U.S. economy left him suddenly out of the mill business and looking for a means of ensuring his own financial security. In this scenario, vexation gave way to ingenuity.

As the famed columnist Dale Carnegie (How to Win Friends and Influence People) would later write in a 1940 featurette on Duncan, “he capitalized on what seemed to be bad luck. . . . Duncan was not an inventor and knew nothing about mechanics, but he had what was more valuable—an idea and determination.”

Sounds inspiring, but Duncan probably wouldn’t have appreciated that description very much. “I had a good deal of mechanical experience,” he noted in his own 1918 article, “and I decided to experiment with the hope of producing an addressing machine which could be marketed.

“My first experiment was pretty crude,” he continued. “I glued the rubber parts of a number of hand stamps onto a big wooden drum. This drum was then revolved from one address to another to do the printing. The work was readable, and there was no chance to make mistakes in the address. But the drum only held a few names. How was it to take care of even a small mailing list such as we had? Clearly the plan was a failure, because it was not practical.”

What follows in Duncan’s account is a pretty crystal clear portrait of the mindset that separates successful innovators from the rest of us.

“Further trials were not encouraging. At times I tried to convince myself that it was hopeless, that I was wasting my time on a wild idea, and that I had better abandon it and try to get some sort of a position. But ‘myself’ would not be convinced. The conviction that the business world needed a machine to take the place of slow, tiring hand work in routing addressing, and that I could solve the problem if I kept at it, never left me.

“One day it occurred to me that the difficulty might be done away with by setting up the addresses in individual rubber type, and linking them in detachable chains of carriable length. I made a model along these lines and showed it to several of my business friends. Most of them thought the idea very clever, but all were skeptical as to its practicability; in fact, several of them laughed at the thing, and told me I was foolish to waste time in trying to commercialize a device of that kind.

“But no doubting or ridicule could disturb my conviction. Encouraged by a very good friend, I came to Chicago in the latter part of ’93 and rented a small room on Dearborn Street where I proposed to begin the manufacture of the Addressograph.”

In the late summer of 1893, with the Columbian Exposition still in full swing down the road, J. S. Duncan launched the Addressograph Company from his office in the old Caxton Building on Dearborn, and within six months, he had sold off most of his patent-pending prototypes . . . despite the fact that they looked like something out of a Ray Harryhausen monster movie, or perhaps Pink Floyd’s The Wall.

Over the next two years, Duncan went to work designing a more robust second model of the machine, which was manufactured in the plant of Chicago’s C. H. Stoelting Company. He also found himself a worthy business partner and salesman in the form of John B. Hall, who took the Addressograph on a national sales tour to drum up interest, including personal demonstrations for some of America’s leading business tycoons.

“Mr. J.P. Morgan realized the possibilities of the idea,” Duncan later wrote. “and went straight to the heart of the matter by saying, ‘But that isn’t big enough for us. You ll need a bigger machine and more than two lines for the addresses.’ Mr. Hall returned from his trip feeling that the results had been highly satisfactory. He was firmly convinced that not only was there an immediate market for the Addressograph, but that the future held great possibilities as yet unseen.”

Part II. Keep the Plants Running

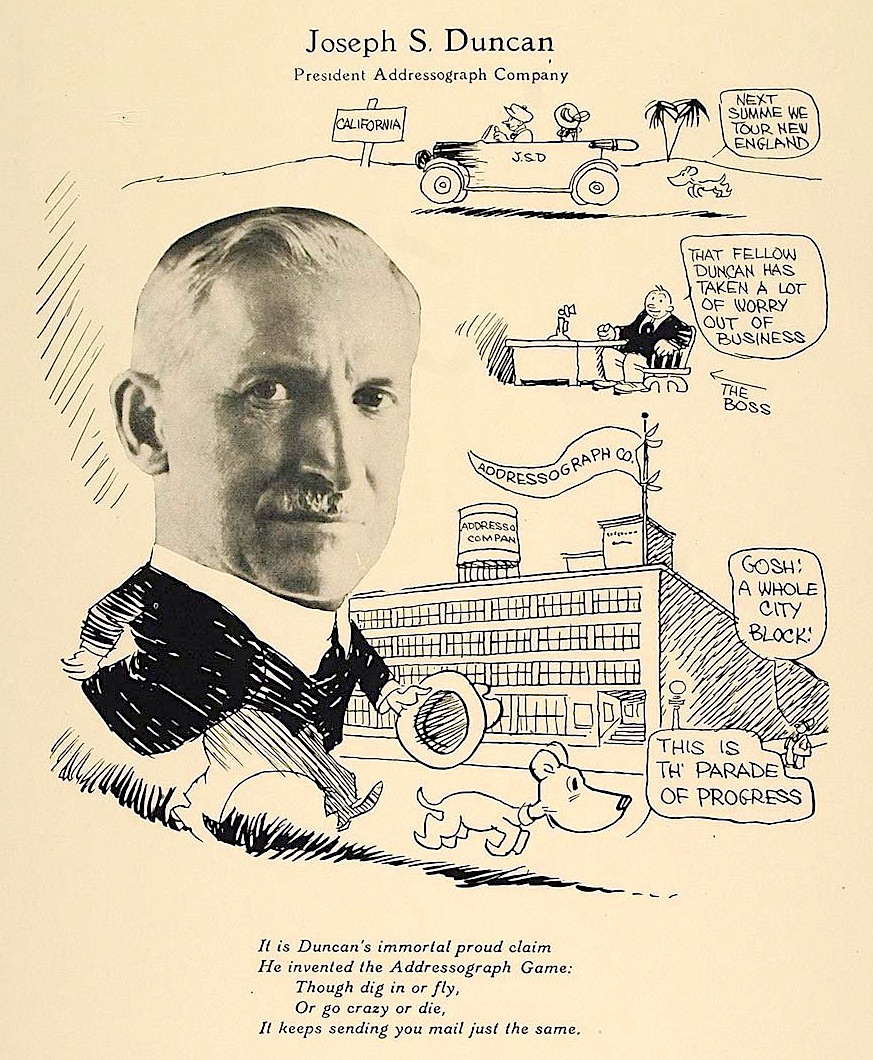

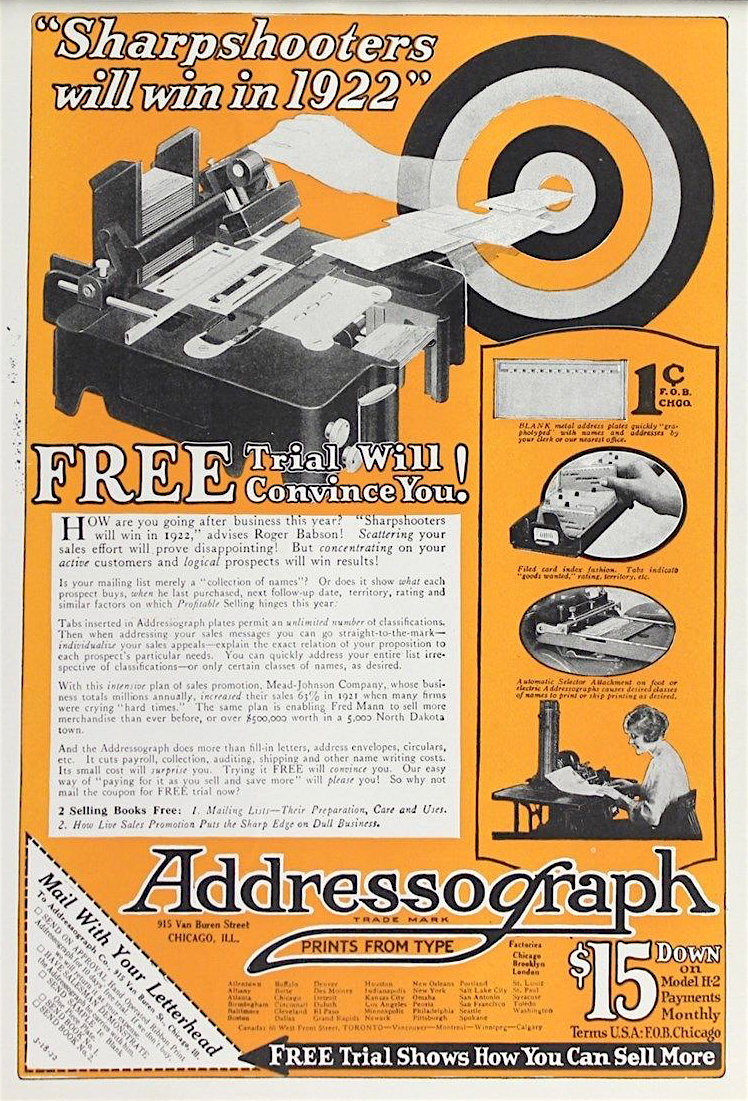

“Our success is the result of our ability to supply what the customer wants by adding an attachment or making changes on one of our standard machines; or by developing a new machine, especially suited for certain classes of work, and yet flexible to use our many standard attachments.” –J. S. Duncan in Forbes magazine, 1921

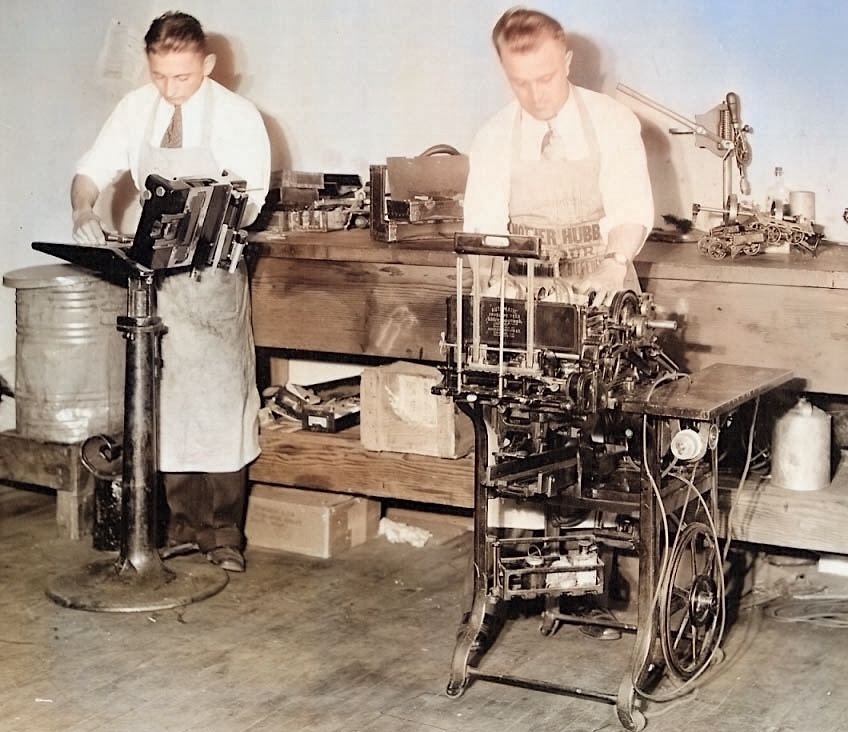

In 1904, construction began on a new, dedicated Addressograph Company factory at the corner of West Van Buren and Peoria Street in the West Loop. The six-story structure employed more than 300 people, about evenly split between men and women, and there was never a shortage of new attachments and design changes to implement on the factory floor.

In 1904, construction began on a new, dedicated Addressograph Company factory at the corner of West Van Buren and Peoria Street in the West Loop. The six-story structure employed more than 300 people, about evenly split between men and women, and there was never a shortage of new attachments and design changes to implement on the factory floor.

J. S. Duncan, by now approaching 50, remained extremely active in the evolution of his product, letting J. B. Hall handle most of the sales details. Along with rolling out new models of the Addressograph an almost annual basis, he invented a machine for more efficiently creating and maintaining the mailing lists themselves, using a keyboard that could emboss recipient names on metal links. This was the aforementioned Graphotype, which went through its own series of regular model updates with increasing automation.

By 1910, the G2 Office Graphotype and A1 Automatic Addressograph were helping bigger clients like Marshall Field & Co. reach 100,000 paying customers per month, with barely any human labor required on the labeling end.

During World War I, the U. S. government relied on Addressograph machines for much of its mass communications, and the company came out of the conflict stronger than ever, increasing its Chicago workforce to over 1,000 employees, and opening additional factories in Brooklyn and the United Kingdom (as Addressograph, LTD).

“In this country we have long recognized that any labor saving device which would minimize hand-labor was a cost reducer,” Duncan told Forbes in 1921, “but it took the World War to drive the lesson home. When labor simply could not be obtained, it became necessary to resort to mechanical devices or ‘shut up shop!’ When men could not be secured to cover sales territories, it meant reaching customers by other means or losing the business. Those who learned this early in the game got the cream of the sales.

“It is the quickness with which a businessman sees a change in condition and adapts his business to that change that builds up his organization. I do not pretend to be an expert salesman, but I never could understand how men expect to enlarge their business interests by curtailing their sales force and shutting down on their advertising just because times are dull. I should think that at such a time all possible pressure should be put on to keep the plants running.”

“It is the quickness with which a businessman sees a change in condition and adapts his business to that change that builds up his organization. I do not pretend to be an expert salesman, but I never could understand how men expect to enlarge their business interests by curtailing their sales force and shutting down on their advertising just because times are dull. I should think that at such a time all possible pressure should be put on to keep the plants running.”

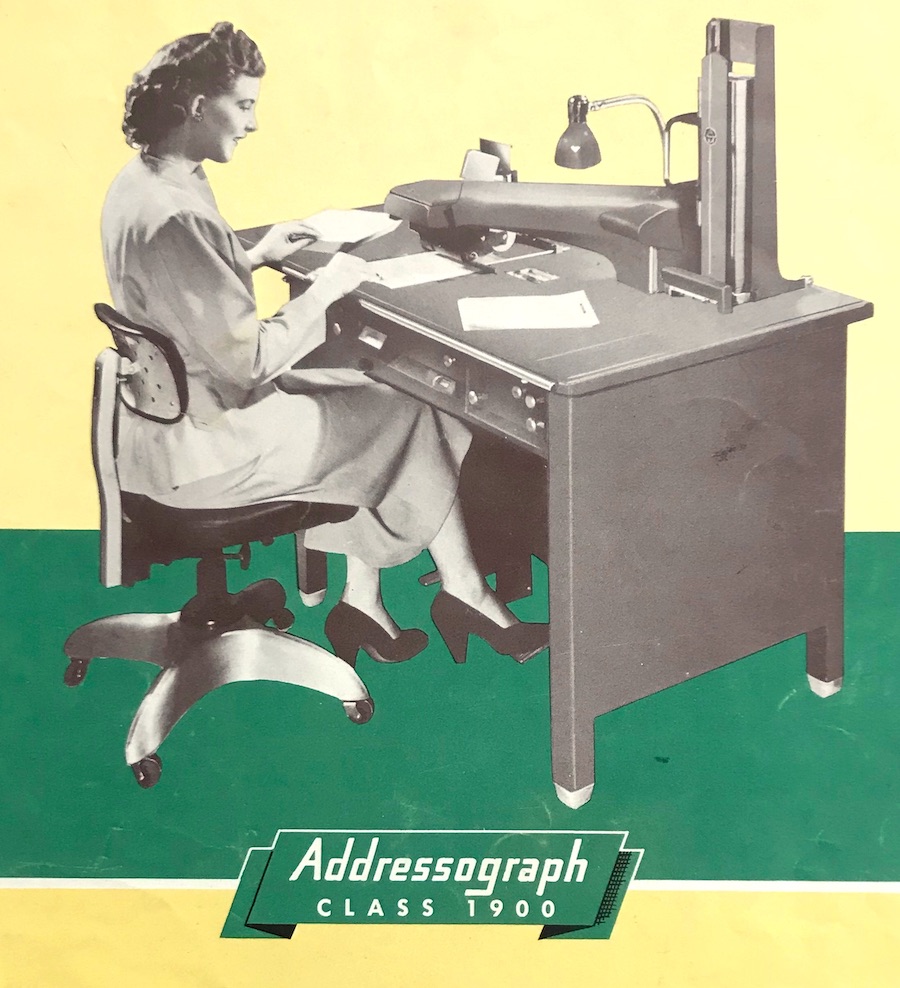

The electrically-operated model F2 Addressograph became the new standard after the war, printing through an ink ribbon sold in the types of fancy ornamented tins featured in our museum collection. It was one of Joseph Duncan’s last big contributions to the company he created.

By the early 1920s, John Hall had passed away, and Duncan was in semi-retirement, spending a lot of his time in Los Angeles with his wife Adelaide. Finally, in 1924, he elected to step away for good, with half the interest in Addressograph staying with the Hall family, and the other half acquired by another Chicago businessman, Frank H. Woods of Lincoln Telephone & Telegraph.

Woods installed Joseph Egerton Rodgers as the new company president, and by 1930, after some legal battles with the Hall family, the new ownership struck a deal to merge the Addressograph International Corp. with one of its chief rivals, the American Multigraph Co. of Cleveland, Ohio. The new organization, known as the Addressograph-Multigraph Corporation, ultimately centralized its operations in Cleveland, effectively ending our segment of the story.

[The former Addressograph building in Chicago, the company’s HQ from 1904-1930, is now owned by the University of Illinois-Chicago, and is known as CUPPA Hall; 412 S. Peoria Street, on the corner of Van Buren. Before & After: 1918 and 2017]

It is worth noting that, once out of the Depression, Addressograph-Multigraph continued to grow, taking forays into credit card manufacturing and engineering graphics, and reaching new sales peaks in the late 1960s. But afterward, the firm was left to scuffle for survival amid the Xerox apocalypse. Addressograph remained its own division of the newly named AM International in the 1970s, and ultimately was purchased by a firm called DBS, Inc. when AM went bankrupt in 1982.

The brand didn’t quite make it to the 21st century, however, and by now, few living businessmen or women would even know the Addressograph name. But the ease of communication so many office workers “enjoy” today is at least partly indebted to J.S. Duncan (1858-1950) and his stubborn drive to fix a thing that annoyed him.

Sources:

Manufacturing and Wholesale Industries of Chicago, 1918

“How to Cash In On Advertising: Methods Used by the Addressograph Company, as Described by its President” – Forbes magazine, Feb 18, 1922

“Little Stories of Beginnings” – Office Appliances, February 1923

“The Story of the Addressograph” – The Wonder Book of Knowledge, by Henry Chase Hill, 1923

“Free Time and Paid Dividends” – Dale Carnegie column, Sept 12, 1940

“Joseph Duncan, Addressograph Inventor, Dies” – Chicago Tribune, May 12, 1950

“Davis’ Try at Reviving Addressograph Hasn’t Turned Trick” – Wall Street Journal, June 30, 1974

“AM International, Inc.” – Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, Case Western Reserve University

I worked in Glasgow Scotland in the 50s where I made addressigraph plates for mass mailing of envelopes and future bets for a large bookies office. Betting on horse racing and football games was/ and still is legal.

I later used that skill for IBM punch cards at a hospital I worked at in Los Angeles, CA.

Found a model G1 Graphotype in a closet at my 100+ year old church. Any collectors or museum that might like to have it? Hate to just trash it.

A friend and I worked in a hospital when we were in our late teens. That was in 1969. We worked in the mail room where we did what was called the night run. The night run consisted of printing up a list of every patient in every wing of the hospital. And in order to do that, we had to sit in front of the addressograph, and after first entering each patient’s info: Name, Date of entry into the hospital, Age, Medical Record #, and Unit, we then took each tray of metal plates, and after carefully slipping the tray of plates into the feeder, and with a loud “Ka-chunk, Ka-chunk, Ka-chunk”, it grabbed each patient’s metal plate and printed the list of hospital-wide patients. We did this every night but only after deleting the patients who went home and adding the new patients who had come in that day. We did this every night just after midnight. It was certainly an experience.

I am ex employee form 1980 -1995. There are now two Facebook groups for AM International/ Addressograph looking for ex colleagues, photos documents, stories etc. One group is in the UK and the other Australia.

I worked at Addressograph Multigraph in Cleveland in the 1960’s in the sales department. Hal Ischay was the department head and Marie Bauer was my supervisor. We kept track of all the sales of the sales personnel of the 144 divisions. It was a great job!

I was gone for quite some time before it was bought and renamed A&M International.

Wondering if anyone ever received a pension from Addressograph Multigraph?

A very interesting account.

I worked at Addressograph headquarters at Hemel Hempstead, Great Britain between 1968 and 1974. l was in Price Control and then Machine order Control (order progressing). I dealt with the photocopier side and addressing machine side of things. It was and still is one of my best memories of being employed during my working life.

I vividly remember the shop floor with the production lines, not just for the above but on the multilith and multigraph machines being worked on and tested. So many memories come rushing back to me. I have a collection of paperwork, sales and other related items including three hand held 500 addressing machines.

I find it very poignant to feel that it went bankrupt only some 8 years after I left. Though I personally thought it went on to about 1990 or 1992. I still remember all the people and can visualise them very easily. I contribute to a website called Hertfordshire Memories, with whose county the factory was. Good luck to you all!

My first job was in the church rectory and I had to learn how to use the addressograph machine to make the church envelopes. Then another job I used the addresograph machine to make employee time cards. Then another job I used the addressograph machine to make slips for retail milk deliveries. THanks Mom for teaching me to use the

addresograph machine. This was all in the 1980’s.

Hi there

My son bought House outside cleveland abnd there is a addressograph cabinet in basement. Any Great idea on who to donate or sell IT or just take IT away!

IT is supra heavy and will need 3 guys to move.

Good morning, great article and information! My father was a repairman for the company in western New York until he passed away. I have been trying to find out for a number of years what happened to his pension? I know they filed for bankruptcy but my mom never received anything. Thanks, Brian

I have inherited a pin with a picture of a man, states “Addressograph Multigraph” on green border, and serial plate of #4705 being held. Any way to see if this was an employee pin, and who this employee was? Any response would be appreciated.

we have a model 2200-H No 2I8033 Addressograph

Not sure if this site is monitored, but I am interested in learning the name of Joseph Egerton Rogers wife’s name? One of the articles I read was he had two daughters and also a house in the Adirondacks? If you can find the name of his wife I would be thrilled!

thanks,

Patricia

Hi Patricia, So funny that I came across this as I have been trying to find his first wifes name as well. I am the granddaughter of one of his daughters. Her name was Virginia. Please let me know if you’ve found anything. Thanks!

P.S. I came across an ad for Addressograph’s incarnation in the 1960s (or early 1970s) in an old issue of National Geographic and scanned it for posterity. I’d be happy to send you a copy, if you’re interested.

I worked at AM Addressograph’s administrative offices in Mount Prospect, IL one summer between my sophomore and junior years of college (a year before the company went belly-up). Since I worked in the purchasing department and we sent communications to locations around the world, I was tasked with operating the Telex machine (early email?) and Telecopier (fax machine?). Needless to say, I never used those skills again, but it was fun while it lasted.

Thanks so much for creating this website. I just discovered it and am having a great time reading the entries.

I have a medal (dia. 9 cm) dedicated to J.S. Duncan. On the obverse is an image of Duncan, as on your hand-drawn poster. I would appreciate any information about this medal. Thanks.

With medal, as I see it, there are still problems. Then may be someone has information about a company employee who worked in the 30s of the past century, named J.B. Ward?

My dad worked at Addressograph-Multigraph in Euclid (Cleveland) for 20 years, lost his job when they moved to California. He was a tool and die maker, for the machines.

I remember my parents receiving all sorts of mail addressed by Addressograph. The typeface and the ink impressions were unique. I remember newsletters from synagogues, schools, etc. Of course, once the tractor fed mailing label made it’s appearance, Addressograph was doomed.

I remember one of these in a storeroom at a Hebrew day school. Both halves – the debosser and the actual addressing machine. There were also a full mailing list of plates. I was 16 and couldn’t figure out (a) what I would do with it and (b) how I would get it home — and past my mother. That room also held an abandoned mimeograph machine and maybe even a ditto machine. The issue of Mothers affected this as well.

I have an identical tin like you show. Would you be able to tell me if it is rare and how do I date it. As an aside do they have any value .

Thank you in advance

Trudy

I have a model 6343 Serial number 261511, it looks very old. Looking for information, is it worth anything, how old anything i can come up with would help. It looks like it needs to be in a museum.

Thank You,

Kenny Cook

I have an old Addressograph that my father used in the 50’s to the 70’s. It looks much like the one pictures above. I would like to donate it to an museum if possible.