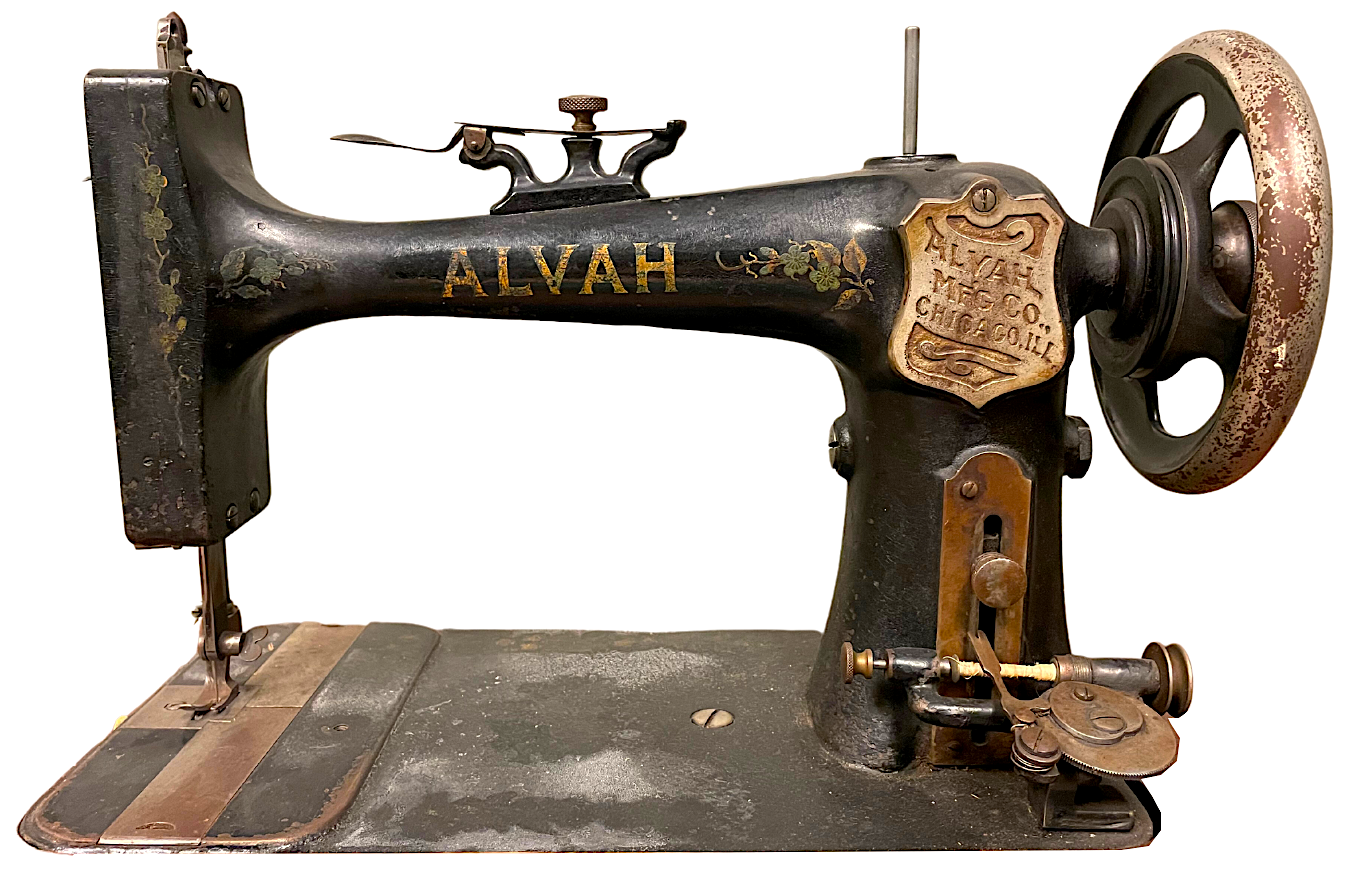

Museum Artifact: Alvah Sewing Machine, c. 1893

Made By: Alvah MFG Co. / Sears, Roebuck & Co. / Ely MFG Co., 149 W. Van Buren St., Chicago, IL [Downtown / The Loop]

Donated to the Museum By: Jerry Cook

This Alvah Sewing Machine, kindly donated to our collection by Mr. Jerry Cook, represents a very specific moment in time–albeit one outside the usual 20th century focus of our museum.

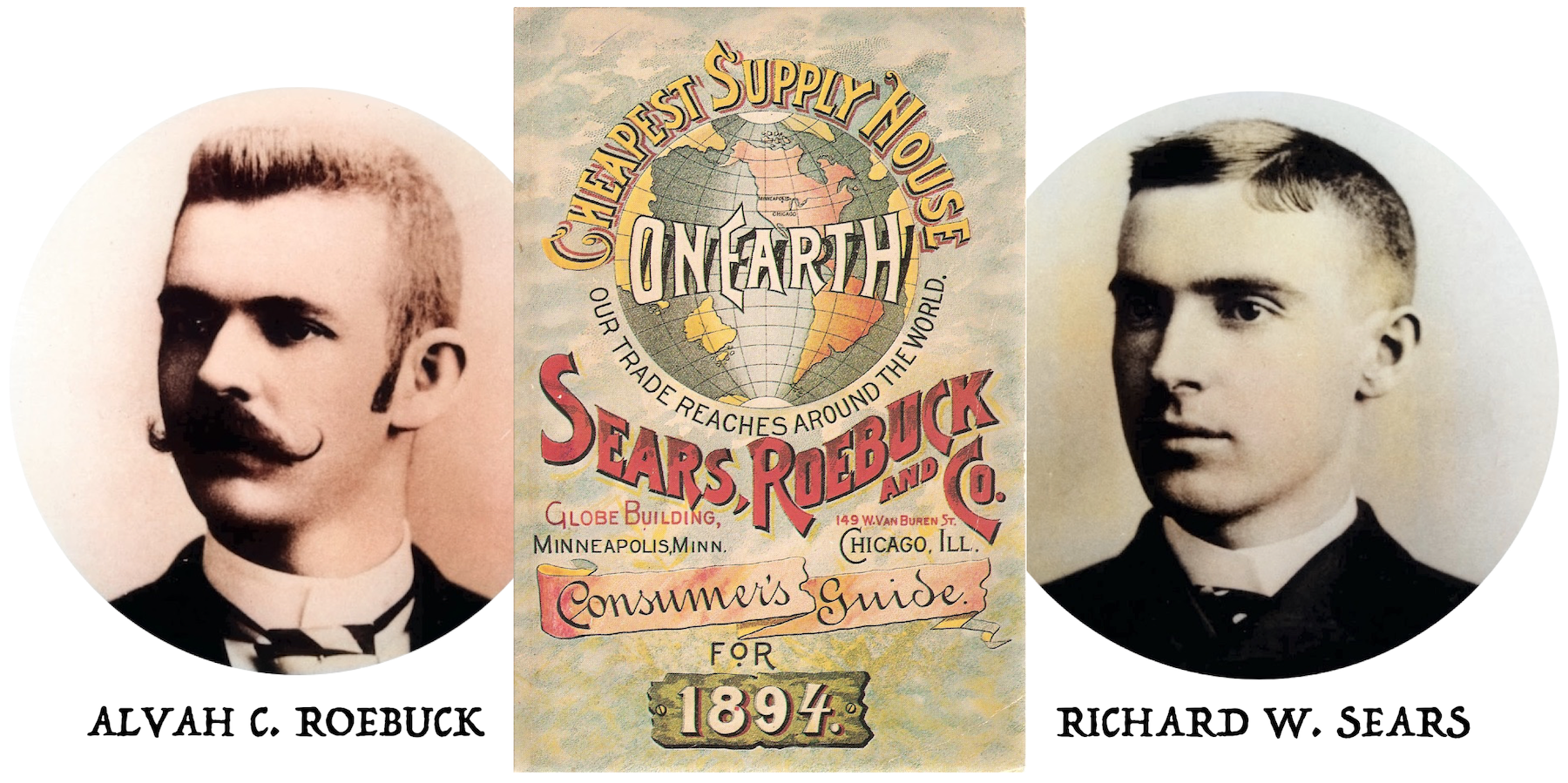

The machine’s supposed manufacturer, as proclaimed by its own identification badge, was the Alvah MFG Co. of Chicago, ILL, a firm that was organized in October of 1892 and dissolved less than a year later. Don’t mourn their loss too much, though. The leaders of the business, Richard W. Sears and company namesake Alvah C. Roebuck, quickly reconstituted their partnership under the slightly more familiar name of Sears, Roebuck & Company, making the Alvah Sewing Machine a sort of “prequel” product for one of the 20th century’s most successful mail order giants.

The machine’s supposed manufacturer, as proclaimed by its own identification badge, was the Alvah MFG Co. of Chicago, ILL, a firm that was organized in October of 1892 and dissolved less than a year later. Don’t mourn their loss too much, though. The leaders of the business, Richard W. Sears and company namesake Alvah C. Roebuck, quickly reconstituted their partnership under the slightly more familiar name of Sears, Roebuck & Company, making the Alvah Sewing Machine a sort of “prequel” product for one of the 20th century’s most successful mail order giants.

Prior to this machine, Sears and Roebuck had focused exclusively on selling third party clocks and watches, by mail order, under the name of the R. W. Sears Watch Company. Sears was the salesman extraordinaire, while Roebuck actually knew how the instruments worked. When the notoriously temperamental Sears decided to sell that business to a competitor around 1891, however, things got a bit awkward.

Banned from selling watches in Chicago as part of a non-compete clause, the regretful Sears soon wanted back in the game, and enlisted his patient cohort Alvah to help him find a loophole. Eventually, to keep Sears’s involvement on the down low, they formed a new business, the A. C. Roebuck Corporation of Minneapolis, followed quickly by Chicago-based offshoots like the Alvah MFG Company. The goal was to expand their mail order business beyond timekeeping and into more big ticket merchandise. These efforts set the stage for Richard Sears’s formal return to the business in 1893 and the launch of the first “Big Book” Sears Roebuck catalog in 1894.

Contextually, then, the Alvah Manufacturing Company qualifies as an obscure interlude in the otherwise epic tale of an American retail icon. If you’re only going to exist as a one-year footnote, though, it might as well be 1892-93 in Chicago; the time and place of the Columbian Exposition and a new wave of innovation in both commerce and engineering. Sears and Roebuck, who were both still in their late 20s, couldn’t possibly have picked a better moment to think big and take a risk . . . even if the general public still needed some convincing.

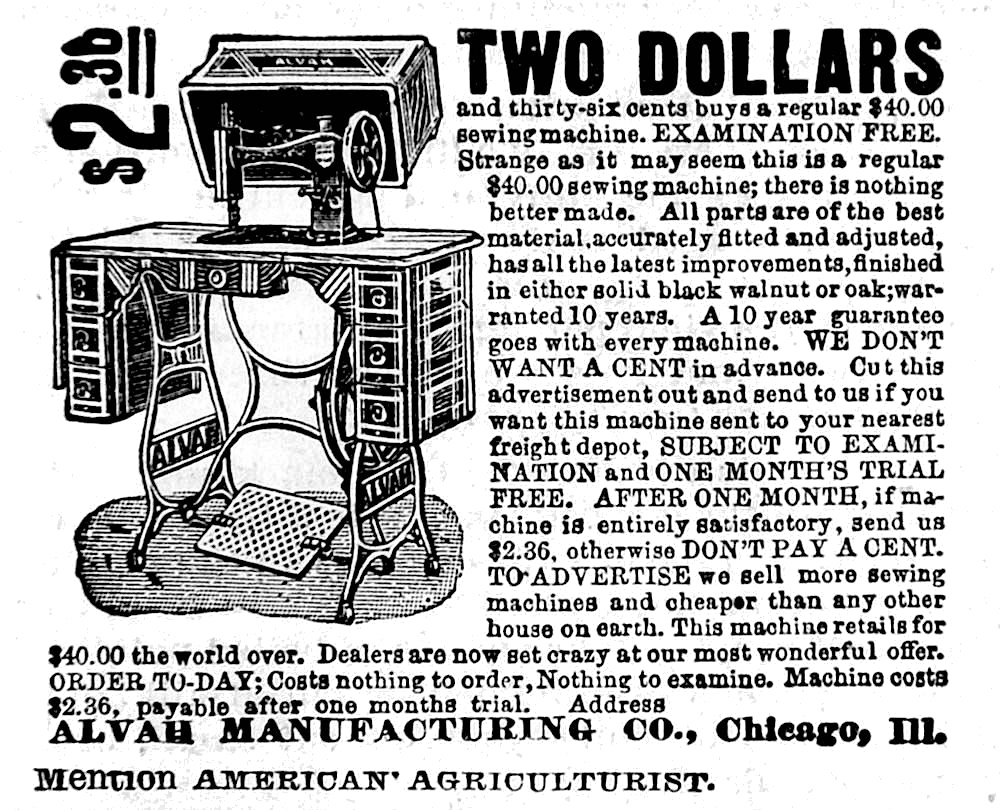

During a brief advertising blitz in the early months of 1893, the Alvah Sewing Machine was widely promoted in major national publications like Scientific American and Colliers, with most listings describing it in Richard Sears’s trademark, carnival barker style:

“TWO DOLLARS and thirty-six cents buys a regular $40.00 sewing machine,” read one ad. “Strange as it may seem this is a regular $40 sewing machine; there is nothing better made. All parts are of the best material, accurately fitted and adjusted. Has all the latest improvements, finished in either solid black walnut or oak. A 10 year guarantee goes with every machine. WE DON’T WANT A CENT in advance. Cut this advertisement out and send to us if you want this machine sent to your nearest freight depot. . . . Dealers are now set crazy at our wonderful offer. Order Today. ALVAH MANUFACTURING CO., Chicago, ILL.”

“TWO DOLLARS and thirty-six cents buys a regular $40.00 sewing machine,” read one ad. “Strange as it may seem this is a regular $40 sewing machine; there is nothing better made. All parts are of the best material, accurately fitted and adjusted. Has all the latest improvements, finished in either solid black walnut or oak. A 10 year guarantee goes with every machine. WE DON’T WANT A CENT in advance. Cut this advertisement out and send to us if you want this machine sent to your nearest freight depot. . . . Dealers are now set crazy at our wonderful offer. Order Today. ALVAH MANUFACTURING CO., Chicago, ILL.”

Similar eyebrow raising offers were promoted by Alvah MFG throughout 1893, not just for its sewing machines, but other high-end goods, including jewelry, carriages and harnesses, and pianos and organs. Some people jumped at the tempting new deals, while others sent out stern warnings against them.

“There is a new concern that has begun to dabble in the piano and organ line, located at Chicago, 44 West Quincy Street, called the Alvah Manufacturing Company,” the Musical Courier noted in an 1893 article titled Look Out! “They address people in mimeograph or printed letters with the unctuous introduction of ‘Kind Friend,’ and they publish pictures, like the medical pictures of ‘before and after taking,’ showing the appearance of the individuals who receive their presents of parlor organs that ‘cost them not one cent,’ because they were the first ones that were lucky enough to write for them. Any fool that gets a letter there first can get an organ for nothing. . . . We warn everybody not to do any business with them until they make direct inquiries from reliable people.”

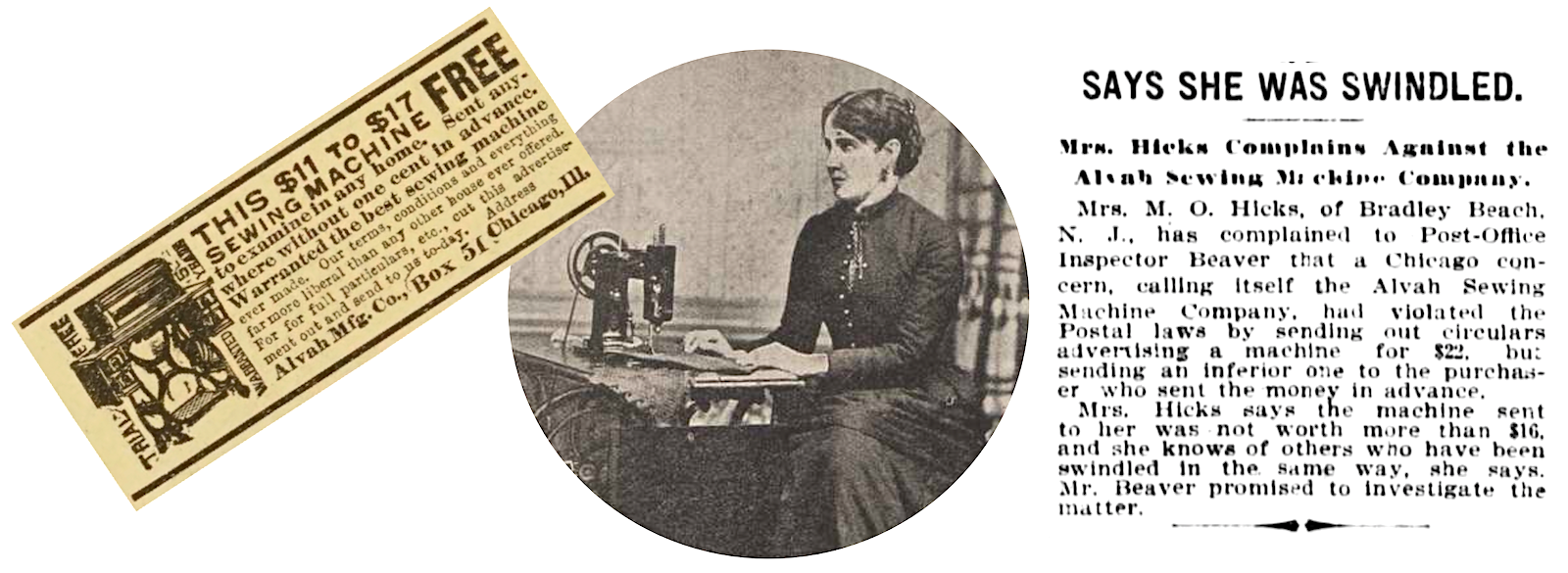

[There is some evidence, such as the above complaint from Mrs. M. O. Hicks in 1894, that advertisements for the Alvah Sewing Machine were blatantly misleading, as customers were sent inferior machines to those described]

The early Sears business model was certainly reckless at the least, illegal by plenty of measures. But as time proved, Americans were willing to roll the dice on their new “kind friends,” eventually turning Sears Roebuck into the country’s largest mail order business. As for the success of the Alvah Sewing Machine . . . that’s harder to determine.

By the time Sears, Roebuck & Co. released their 1894 catalog, the sewing machines there-in were primarily Singer knockoffs manufactured by the National Sewing Machine Co. of Belvidere, IL. Later, turn-of-the-century editions would feature machines by the Free Sewing Machine Co. (Rockford, IL) and the Davis Sewing Machine Co. (Dayton, OH). None of these bore the ALVAH name. So, what became of this machine? And, for that matter . . .

Who Built the Alvah?

Despite the badge on the sewing machine itself, which clearly reads “ALVAH MFG CO., CHICAGO, ILL,” there is no reason to assume that Alvah Roebuck and his crew were manufacturing these units in-house. Roebuck certainly had the technical skill to work on such a machine himself, but based on the mail order business model, it’s more likely the production of the Alvah was outsourced to another manufacturer. It’s also interesting to note that the Alvah MFG Co. wasn’t the only Chicago business to advertise the Alvah Sewing Machine.

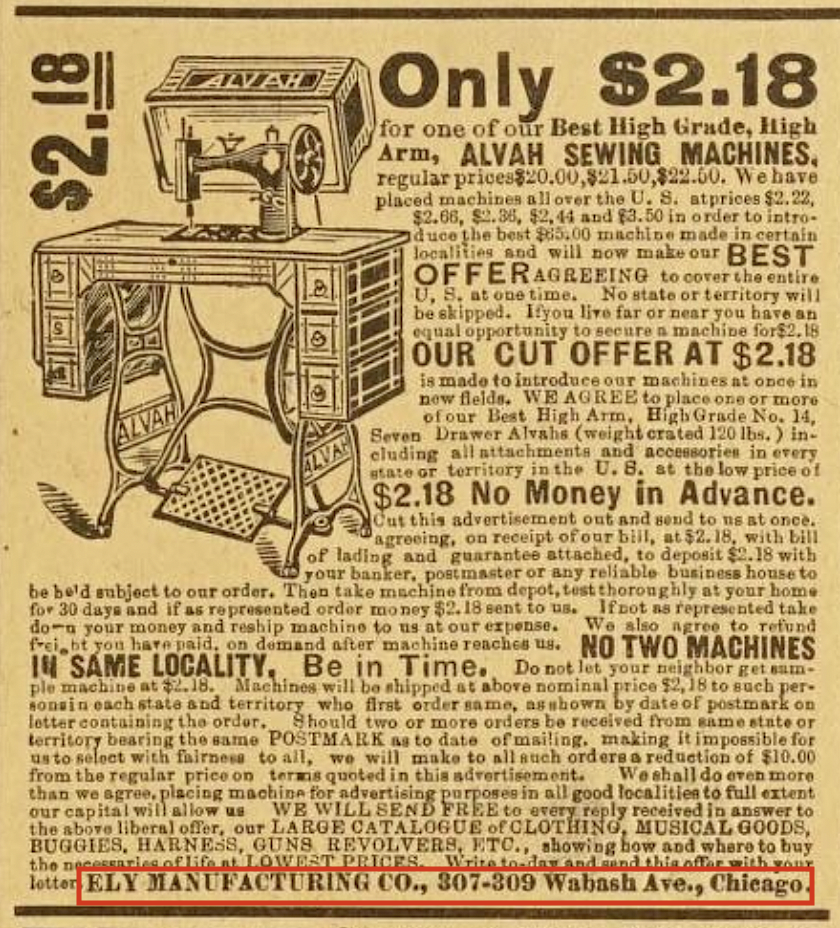

The Ely Manufacturing Company, incorporated in November of 1893 at 307 Wabash, appears to have quickly picked up the mantle after Alvah MFG folded into Sears, Roebuck & Co. From the time of its incorporation through much of 1894, all subsequent advertising for the Alvah Sewing Machine lists Ely as its producer, while using much of the same language and cheeky sales tactics from the Richard Sears playbook. One logical conclusion is that some of the same individuals employed by the defunct Alvah MFG Co. essentially re-organized the same business under the Ely name.

This includes company president Fred F. Ely, who perhaps lacked Mr Sears’s talent for avoiding legal action against his misleading marketing.

Shortly before the Christmas of 1894, Ely was charged with “violating the postal laws respecting the mailing of lottery matter,” according to the Tribune. “. . . His company had been sending out circulars offering an organ for the first order received under the special offer of sewing machines, and a valuable present to every one accepting the offer.” Ely admitted to the scam, but “disclaimed any knowledge of it being a violation of the postal laws.”

The Alvah Sewing Machine advertisements disappeared shortly thereafter, but the Ely MFG Company carried on as a distributor of sewing machines, bicycles, typewriters, and other goods.

Our best guess as to the company that actually manufactured the Alvah machine is actually not a Chicago enterprise at all, but the New York Sewing Machine Company (NYSMCo) of Plattsburgh, NY. According to sewing machine researcher Kelly Pakes, “It was common in the late 1800s for companies to ‘badge’ sewing machines with the name of anyone who paid them money for a label. Many department stores bought badged machines. It is similar to the Craftsman line at Sears: manufactured by many companies, labeled for Sears.”

Pakes believed the design of the Alvah clearly points to the style of other NYSMCo machines from the same era, including early versions of the Demorest brand. Sears and Roebuck then would have then contracted some machines from NYSMCo much in the same business model as the Craftsman line of the future.

Unfortunately, we don’t yet have the smoking gun evidence for this theory, and as such, the Alvah remains something of a mystery machine . . . one of the earliest in a long line of household machines priced to move at all costs.

Sources:

“New Incorporations” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 14, 1893

“Look Out!” – Musical Courier, Dec 20, 1893

“She Says She Was Swindled” – The Evening World (New York), Aug 29, 1894

“Call it a Lottery” – Chicago Tribune, Dec 16, 1894

“Sears Roebuck and Their Sewing Machines” – Charles Law, International Sewing Machine Collectors’ Society

“Sears Co-Founder Got Start Fixing Watches” – Journal & Courier (Indiana), Aug 16, 1998

Check with the Library of Congress trademark sewing machine database. It shows that “Alvah” was a registered trademark in 1894 by Williams Mfg. Co.

I have one of these and it’s in great shape. I’m looking to sell it. Please contact me if you’re interested.

Hello! I think your Alvah was likely manufactured by the New York Sewing Machine Company in Plattsburgh, NY. It looks very similar to this early Demorest:

https://www.kelsew.info/Demorest/WolfgangSN8956.html

I have been researching the Demorest SMCo and I am fairly certain that manufacturing of their first model was contracted out to the New York SMCo, also. I can provide more info and photos but I am not sure this page is still active, so I will await your reply.

I would love a photo of the serial number under the front slide plate and of the underside of the machine. I expect that the underside will have a noticeable and unusual bend in the bar that swings the shuttle which is unique to New York SMCO made machines as far as I know.

Thank you, Kelly. That sounds like a good theory. Feel free to send more info to contact@madeinchicagomuseum.com. I will try to get you a serial number soon (on the road at the moment). –Andrew Clayman, curator, Made in Chicago Museum