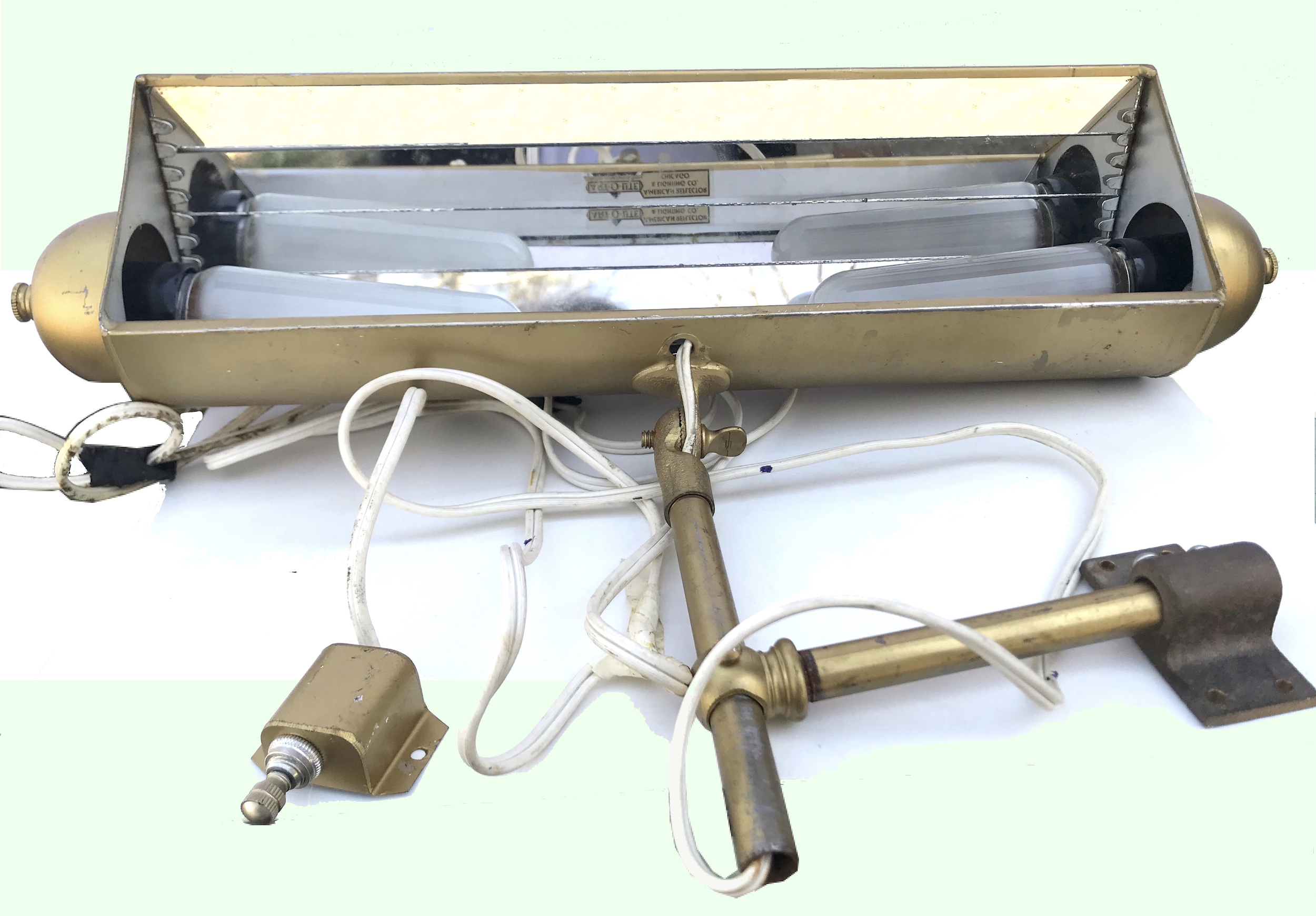

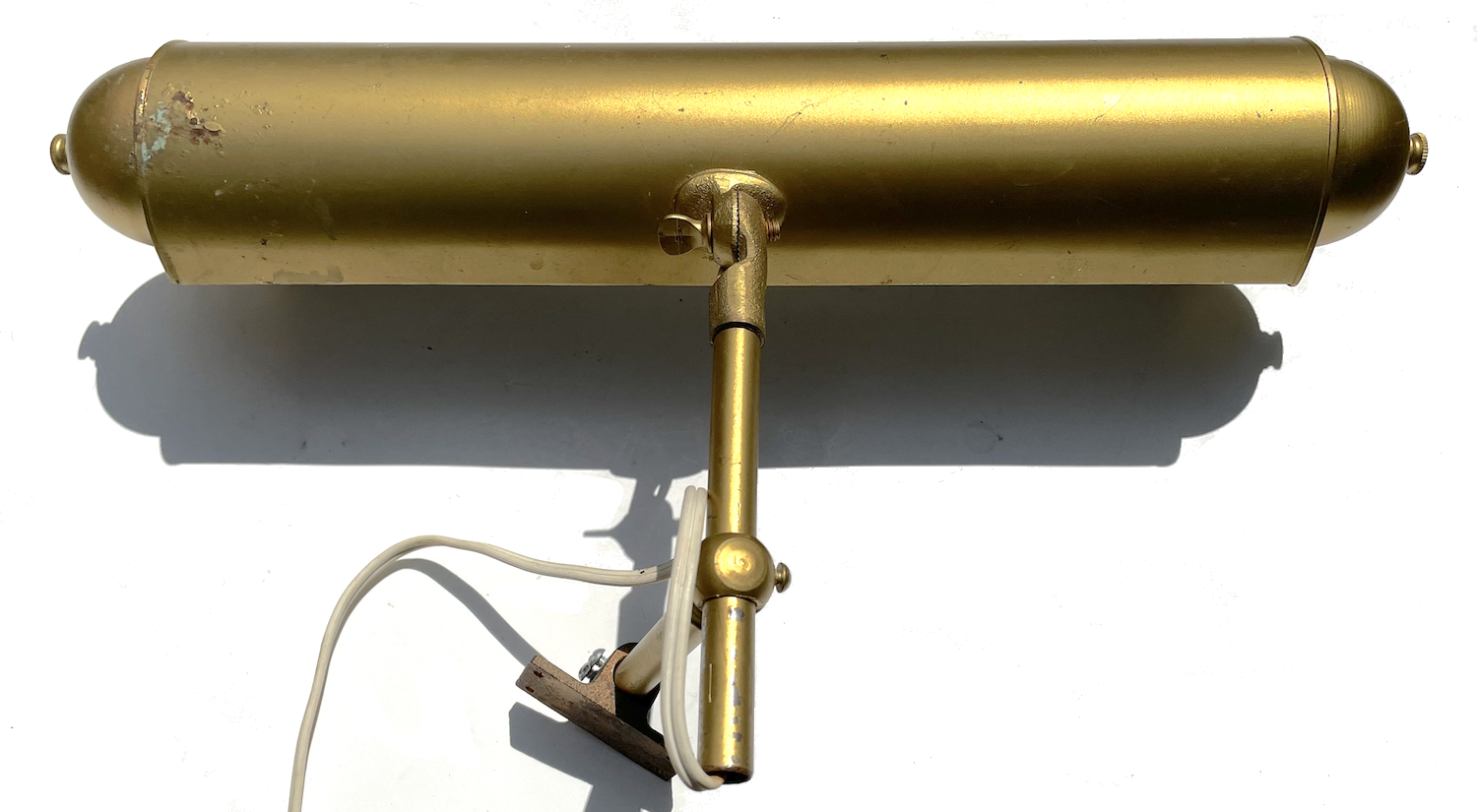

Museum Artifact: Art-O-Lite Reflector Art Lamp, c. 1930s

Made By: American Reflector & Lighting Company, 100 South Jefferson St., Chicago, IL [West Loop]

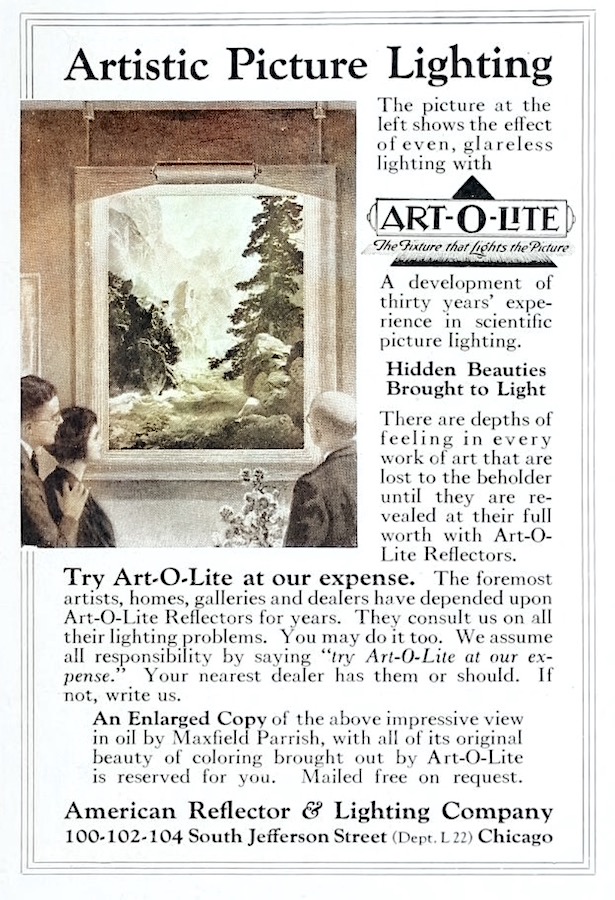

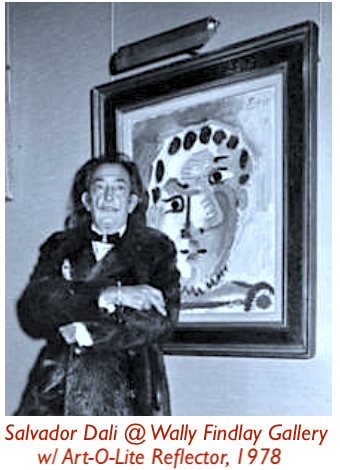

“There are depths of feeling in every work of art that are lost to the beholder until they are revealed at their full worth with Art-O-Lite Reflectors.” —American Reflector & Lighting Company advertisement, 1923

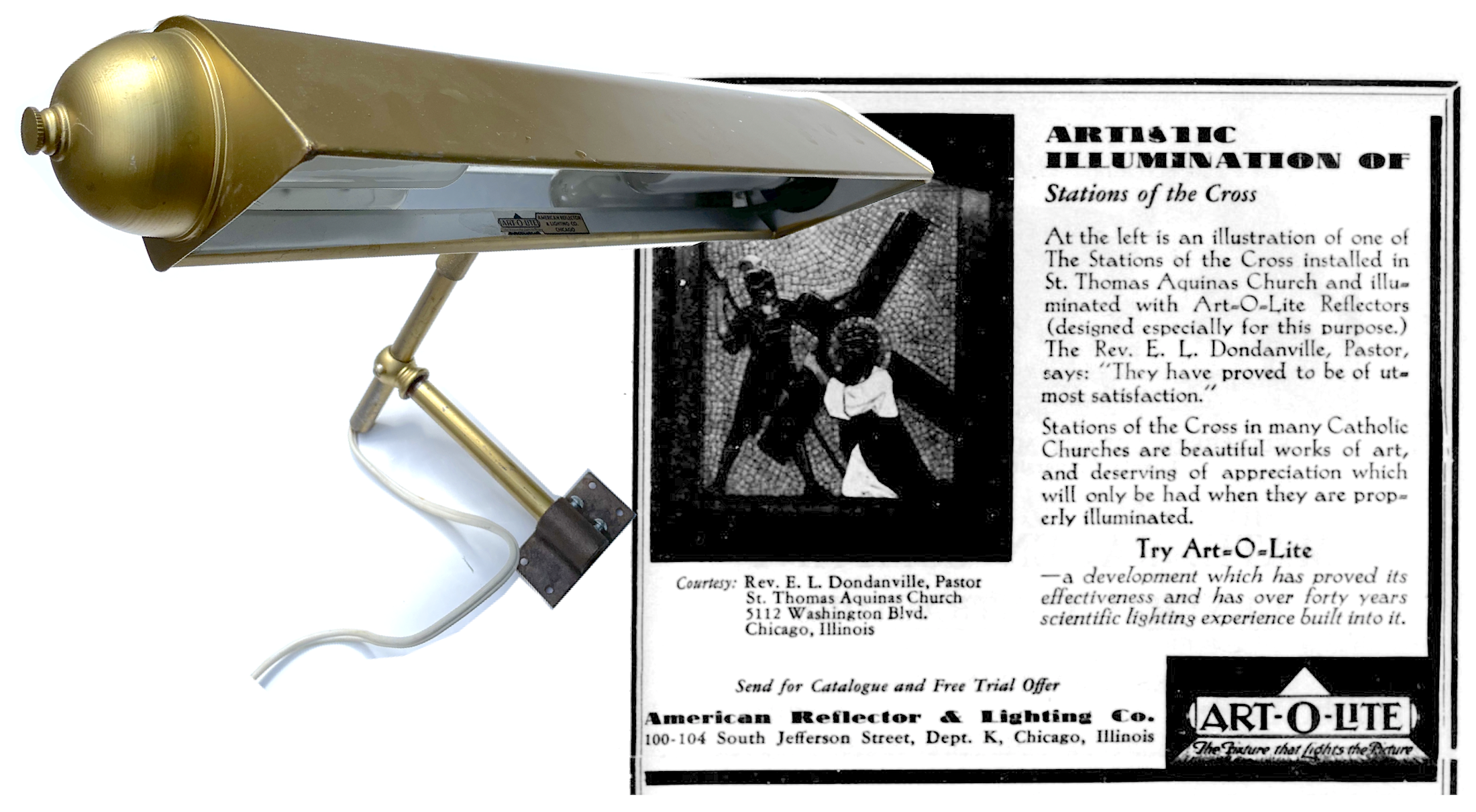

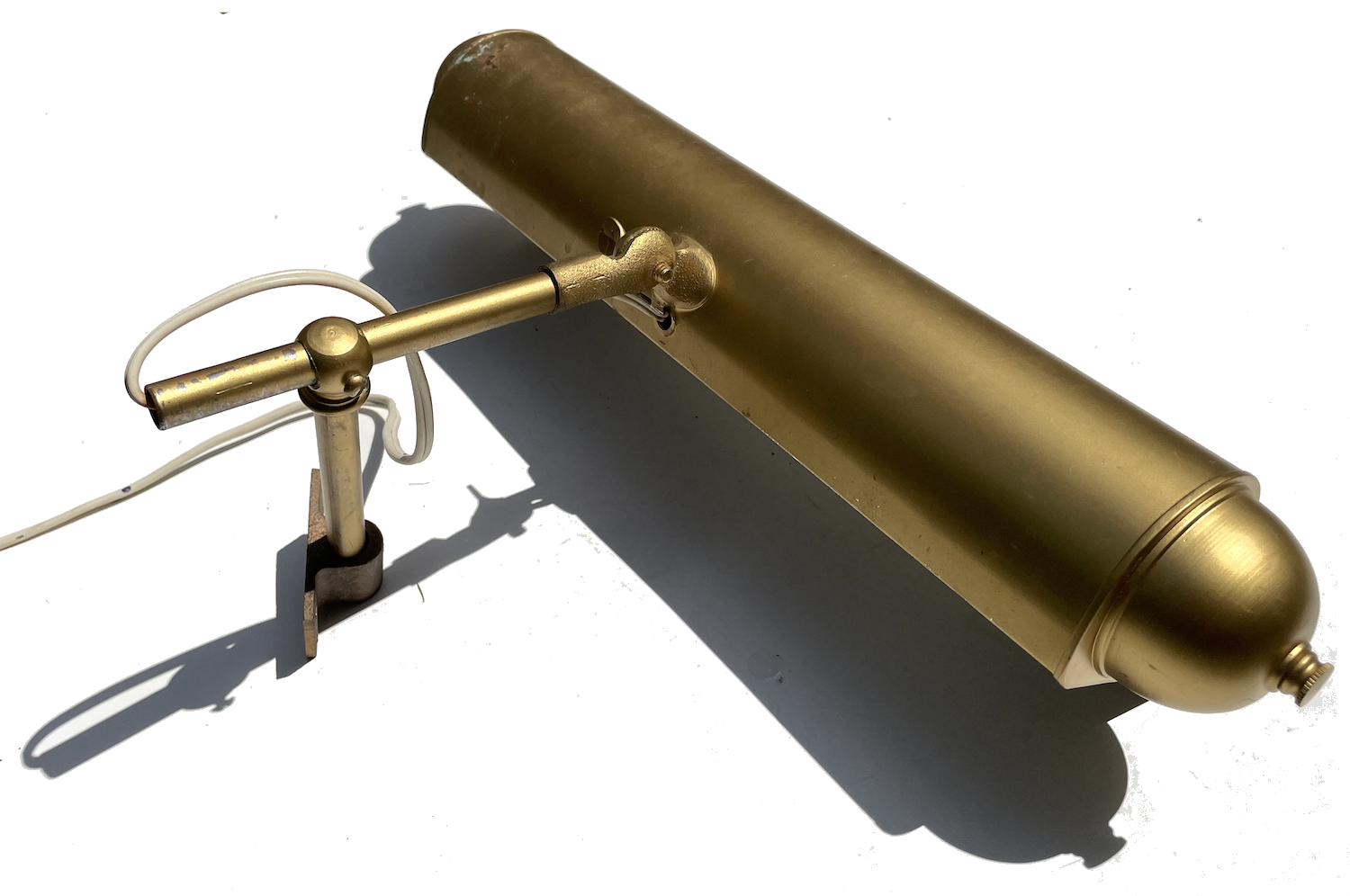

For a business that spent roughly a century specializing in illumination, Chicago’s American Reflector & Lighting Company rarely entered the public spotlight itself. This was a small, family-owned enterprise that, for the vast majority of its existence, served a very particular clientele, making angled picture lighting for museums and art galleries. The “Art-O-Lite” reflector—as seen in our own museum collection—was one of the firm’s leading products and a fine example of its reputation for hand-crafted quality. While we think this model might date back to the 1930s, it can actually be difficult to distinguish changes in the design over the decades. As they say, if it ain’t broke . . .

For a business that spent roughly a century specializing in illumination, Chicago’s American Reflector & Lighting Company rarely entered the public spotlight itself. This was a small, family-owned enterprise that, for the vast majority of its existence, served a very particular clientele, making angled picture lighting for museums and art galleries. The “Art-O-Lite” reflector—as seen in our own museum collection—was one of the firm’s leading products and a fine example of its reputation for hand-crafted quality. While we think this model might date back to the 1930s, it can actually be difficult to distinguish changes in the design over the decades. As they say, if it ain’t broke . . .

“The fixtures were manufactured exactly the same way as the example shown until the very end,” says Doug Lawson, whose family operated American Reflector from the 1910s through the late 1980s. “It has been many years, but I still think I remember how to build them from scratch. . . . I really do appreciate that some people have taken interest in the company and it’s history in recent years.”

Because of its small size and niche focus, there is not a wealth of information out there about the American Reflector & Lighting Company; the firm barely did any commercial advertising after World War II. They also were NOT affiliated, as best we can tell, with the similarly named American Reflector Company of Philadelphia, nor the Art-O-Lite Electric Company out of Moline, IL. Much of what we DO know about the business has been brought to light quite recently through the efforts of two researchers in particular: Paul Martin (grandson of former company president Arthur J. Lawson) and Dr. Wendy Rae Waszut-Barrett, an expert on stage design and scenery.

Following the breadcrumbs all the way back to the company’s beginnings, we can say with some confidence that American Reflector & Lighting was right there at the dawning of the electrical age; incorporated in 1893 and—according to some accounts—organized as early as 1888. While the firm briefly offered a wide range of “general use” lighting fixtures—from chandeliers to lamp posts—its origins were already intrinsically tied to the fine arts; with a specific connection to one of America’s top manufacturers of theater sets and painted backdrops.

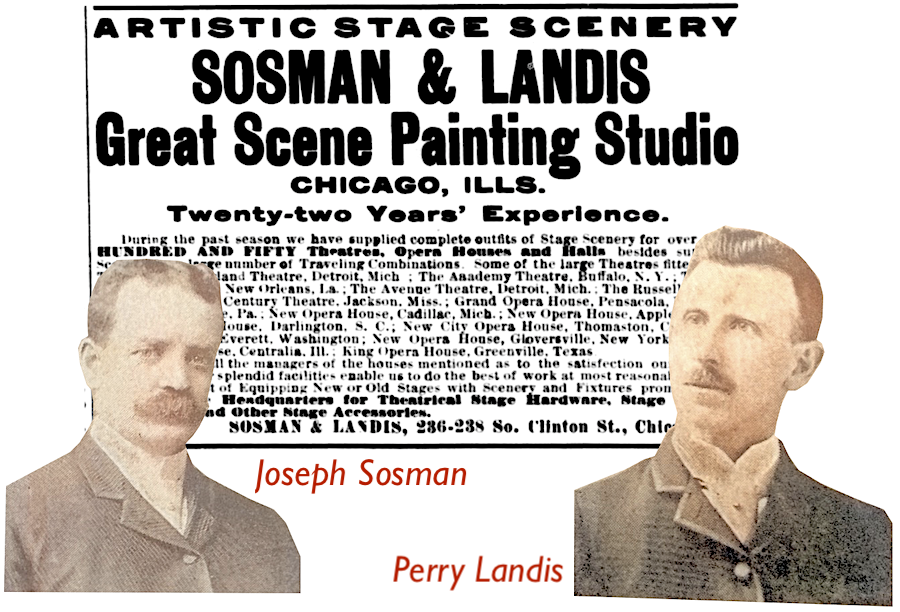

History of the American Reflector & Lighting Co., Part I: Sosman & Landis

When we think of how electricity affected the visual arts, our minds usually jump ahead to the cinema and the “magic” of early motion pictures. But there were big changes inside the more traditional performance spaces, as well, whether it was an opera house, a Vaudeville stage, or one of the country’s numerous masonic temples. Electric lighting offered up lots of new opportunities along with plenty of engineering challenges. Recognizing this, one of Chicago’s established stage art studios of the late 1800s, Sosman & Landis, began offering a wide selection of fixtures and reflectors in its trade catalogues during the years leading up to the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893. This side business was the launchpoint for the American Reflector & Lighting Company, which was officially incorporated just months before the White City opened.

The Sosman & Landis Scene Painting Studio itself was established around 1877 by Joseph S. Sosman and Perry Landis, a pair of Civil War veterans who’d formed a lucrative partnership specializing in “scenery for halls,” as an early 1879 advertisement in the Chicago Tribune described it. Sosman was the creative force and a gifted artist, while Landis showed more of a penchant for sales, schmoozing with theater owners to collect contracts.

The Sosman & Landis Scene Painting Studio itself was established around 1877 by Joseph S. Sosman and Perry Landis, a pair of Civil War veterans who’d formed a lucrative partnership specializing in “scenery for halls,” as an early 1879 advertisement in the Chicago Tribune described it. Sosman was the creative force and a gifted artist, while Landis showed more of a penchant for sales, schmoozing with theater owners to collect contracts.

Rather than employing their own set designers, small independent theaters across the country could hire Sosman and Landis to create hand-painted, reusable backdrops and set pieces that could be shipped straight to them from the company’s Chicago studio at 277 South Clark Street. Standard offerings mentioned in the 1879 ad included: “Elegant Landscape Drop Curtain ($30); Parlor Scene ($18); Wood Scene ($18); Street Scene ($18); Kitchen Scene ($15); and Prison Scene ($15). All new and first class, suitable for small halls or amateur societies.”

Later, when the Tribune reviewed the opening of Chicago’s new Standard Theatre in 1884, it was noted that its “beautiful and effective” scenery was the work of the Sosman and Landis Scenic Studio, “a firm who have almost a national reputation for artistic work.”

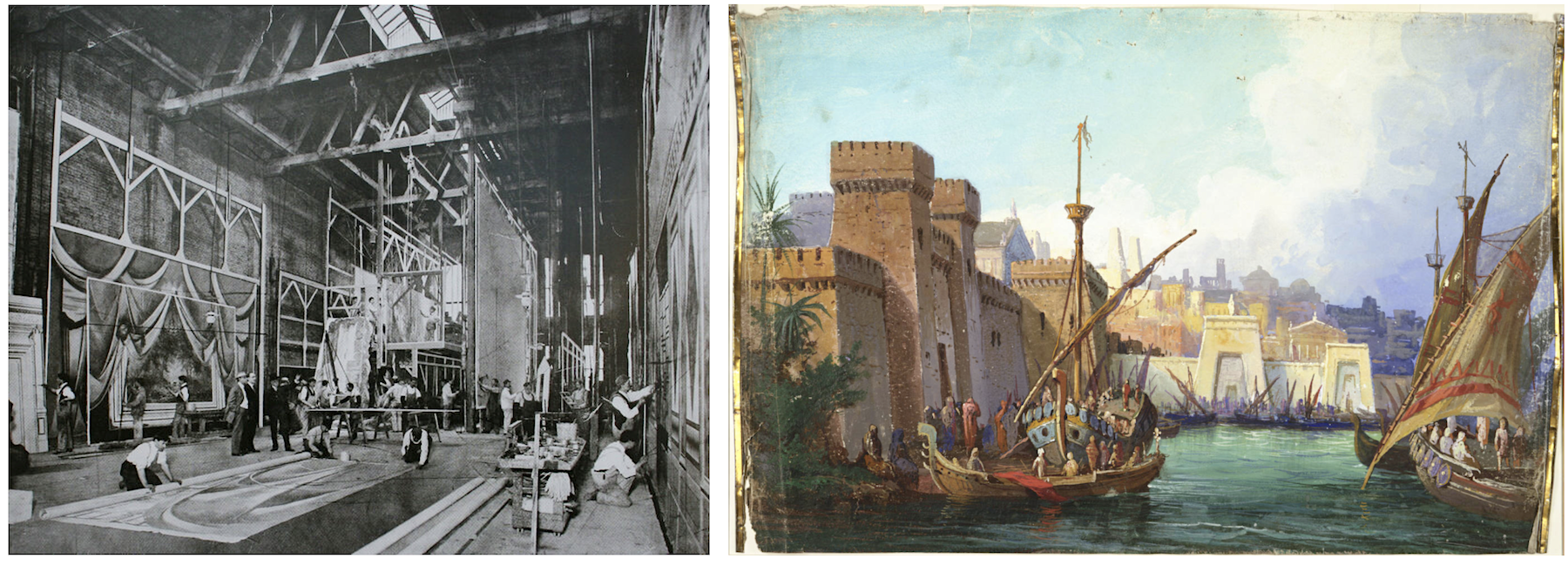

[Left: Inside Sosman & Landis’s Chicago studio, from collection of Dr. Wendy Rae Waszut-Barrett. Right: Backdrop design by Sosman & Landis, from the Holak Collection, Performing Arts Archives, University of Minnesota Libraries]

With increasing influence came an influx of new talent into the S&L offices (including the celebrated painter Thomas G. Moses), as well as an expansion of its services, as Sosman and Landis soon specialized not just in scene painting, but in the “design, construction, rigging, and installation of stage scenery” [Die Verte Wand, 2017].

Understandably then, as an arm of the Sosman and Landis Studio, the American Reflector and Lighting Company was primed for success from the outset, as the same theaters trusting Perry Landis with their lovely backdrops could get two birds with one stone by ordering compatible stage lighting direct from the same reputable fellow.

Landis incorporated American Reflector in 1893 with William A. Toles and Robert L. Latham, at a capital stock of $100,000. Neither Toles nor Latham stuck around long, however, as the primary shareholders would all come from “inside the family” of Sosman and Landis, both literally and figuratively—with Perry Landis and Joseph Sosman holding a majority interest and Perry’s brothers Joseph and Charles Landis also in the fold.

The new business almost certainly got an immediate influx of orders from the Columbian Exposition, and surviving records from early Board of Directors meetings show consistent profits through much of the 1890s.

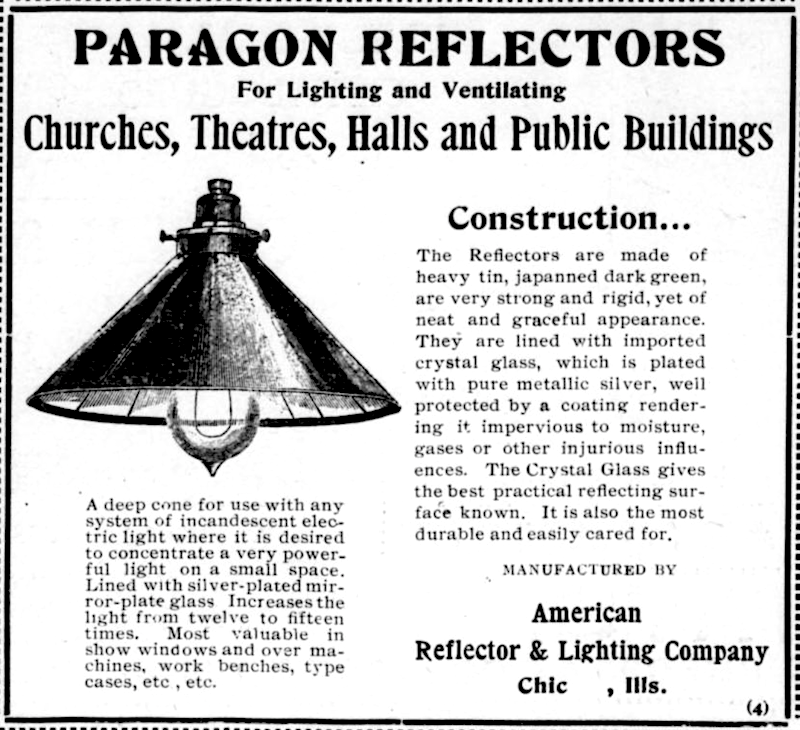

Keeping in mind that the incandescent light bulb had only appeared a little over a decade earlier, this industry represented an exciting but unpredictable basket in which to put one’s eggs. Edison had provided the light source of the future, but independent manufacturers were still competing to harness that light in the most effective and efficient ways possible. The “reflector” was one such means of accomplishing this, and the word took prominence in American Reflector’s name for a reason. This type of fixture, often cone or dome shaped, could now be used “with any system of incandescent electric light, where it is desired to concentrate a very powerful light on a small space,” and it was in extremely high demand heading into the 20th century.

“Treasurer Charles Landis of the American Reflector & Lighting Company of 271-273 Franklin Street, Chicago, reports a factory full of orders,” the Western Electrician magazine reported in 1897. “The American Reflector company manufactures over 150 styles of reflectors for electricity, gas and oil. . . . It makes reflectors for lighting art galleries, window reflectors, orchestra shades, incandescent street electric light hoods, stage dimmers, incandescent calcium light theatrical lamps, reflector chandeliers, hall & vestibule lamps, silver-plated mirror reflectors—in fact, it is safe to say anyone desirous of purchasing anything in the line of reflectors can find goods to suit him in the Chicago salesroom of the American company.”

[Company letterhead and examples of American Reflector fixtures, 1897]

Another issue of the Western Electrician makes particular note of one of American Reflector’s products: the “Paragon” line of reflectors, which was claimed to “utilize all the light possible, distributing it where it is wanted. . . . The reflectors are made of heavy tin, japanned dark green, are very strong and rigid, yet of neat and graceful appearance. They are lined with imported crystal glass, which is plated with pure metallic silver, well protected by a coating, rendering it impervious to moisture, gasses, or other injurious influences.”

Advertisements for the Paragon reflectors claimed they could increase the light “12 to 15 times” what a bulb would manage without them, making them ideally suited for “show windows and over machines, work benches, type cases, etc.” Similar styles of industrial lighting fixtures have seen a renaissance in the 21st century, often installed in hotels, restaurants, and cafes for a cool “vintage” effect.

By 1899, American Reflector was described by Western Electrician as having “a steadily increasing business” and as being “one of the best known in this line of business. Under the careful supervision of manager Charles Landis [Perry’s younger brother], it is meeting with success. It has made some of the largest reflector installations in the United States, and is always on the alert for improvements in this particular line.”

By 1899, American Reflector was described by Western Electrician as having “a steadily increasing business” and as being “one of the best known in this line of business. Under the careful supervision of manager Charles Landis [Perry’s younger brother], it is meeting with success. It has made some of the largest reflector installations in the United States, and is always on the alert for improvements in this particular line.”

Unfortunately, while researchers like Dr. Waszut-Barrett have uncovered remarkable info about various talented artists who came under the employ of the Sosman and Landis Studio during these same years, we know far less about the electrical engineers, designers, and assemblers who might have occupied the early American Reflector offices at 215-219 S. Clinton Street, nor the subsequent turn-of-the-century headquarters at 271-273 Franklin Street (located on the second floor of the Knapp Electrical Works building).

According to reports from the Factory Inspector of Illinois, American Reflector had a team of just four dedicated workers in 1894, increasing to 10 by 1899 and 16 by 1902. However, these counts might be misleading. For a company that featured such a wide variety of products in its catalog, we’re left to wonder whether a lot of the production was outsourced, or if the true workforce of American Reflector was simply never properly recorded. A team of skilled workers, helping to craft some of the country’s first iconic industrial lighting fixtures, will have to remain mostly faceless for now.

Part II: Arthur Lawson & the Art-O-Lite

American Reflector’s first decade was arguably its most impactful, as a combination of increasing competition and unavoidable setbacks slowed the firm’s growth at the outset of the 1900s. While still associated with the studio of Sosman and Landis and largely owned by those two families, the window was gradually closing on the heyday of theater scene painting. Perry Landis, founder of Sosman & Landis and American Reflector, was forced to retire from both firms due to illness in 1903, and he died two years later at just 55 years of age, leaving his brother Joseph Landis as the new company president and Charles Landis and its primary operating manager.

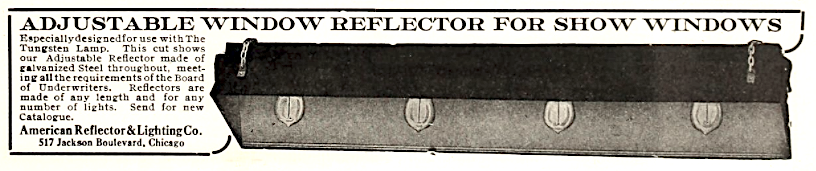

Around this same time, in 1904, a fire inside one of American Reflector’s manufacturing spaces at 201 Van Buren Street proved another financial hit. By 1908, the capital stock of the business was reduced from $100,000 to $10,000. The offices also relocated to a humble space at 517 Jackson Blvd.

Around this same time, in 1904, a fire inside one of American Reflector’s manufacturing spaces at 201 Van Buren Street proved another financial hit. By 1908, the capital stock of the business was reduced from $100,000 to $10,000. The offices also relocated to a humble space at 517 Jackson Blvd.

Prospects might have looked grim, but the company always seemed to find a new niche when it needed it, and during the 1900s and 1910s, American Reflector became the go-to source for retailers looking to illuminate their showcases and window displays with efficient “tungsten” reflectors.

“The proper displaying of merchandise goes a long way in making a business a success,” read a 1912 article promoting the opening of the Rike-Kumler Company’s new department store in Dayton, Ohio. “Realizing this, the Rike-Kumler Co. made it a point to install the very best reflector that the market affords. After investigating many different makes, they decided on the reflector manufactured by the American Reflector and Lighting Co., of Chicago, who installed the same kind of reflectors furnished to Marshall Field, Mandel Bros., Carson Pirie Scott, the Boston Store, A.M. Rothschild (all of Chicago); the Emporium (San Francisco), and the New Marston store (San Diego).”

[1915 advertisement for American Reflector’s Window Reflector for show windows]

Along with these stellar contracts, American Reflector was boosted by new blood in its boardroom. In 1916, shortly after the death of Joseph Sosman, a 33 year-old upstart named Arthur J. Lawson became a partner in the business, and was almost instantly elected the new company president. The aging Landis brothers, Charles and Joseph, while still shareholders, didn’t seem to be actively involved in running the business by this point, and the once presumed heir to American Reflector, Perry Lester Landis (son of the late Perry Landis), also sold his shares by the end of 1916, essentially making Arthur Lawson the sole captain of American Reflector moving forward.

Despite our best efforts and those of researcher Dr. Waszut-Barrett and Lawson’s own grandson Paul Martin, Arthur Lawson remains something of a mystery man, having emerged seemingly from nowhere to become head of a respected electrical manufacturing business. His road certainly wouldn’t have been an easy one.

According to census records from 1900, when Arthur was just 16, his father John Lawson, a cooper by trade, had been removed from the family home in Chicago and committed to the Illinois Northern Hospital for the Insane in Elgin. Arthur’s three older brothers were all working as clerks or salesmen by this point, helping to support the family, and Arthur himself had a paying gig as a “timekeeper.” By 1910, records show Arthur as a lodger in a St. Louis boarding house, apparently unemployed at age 27. So how did he wind up presiding over American Reflector just a few years later?

According to census records from 1900, when Arthur was just 16, his father John Lawson, a cooper by trade, had been removed from the family home in Chicago and committed to the Illinois Northern Hospital for the Insane in Elgin. Arthur’s three older brothers were all working as clerks or salesmen by this point, helping to support the family, and Arthur himself had a paying gig as a “timekeeper.” By 1910, records show Arthur as a lodger in a St. Louis boarding house, apparently unemployed at age 27. So how did he wind up presiding over American Reflector just a few years later?

Well, his grandson Paul Martin believes that Lawson, upon returning to Chicago, became a boarder again in a home owned by a Mr. Fred Eberhardt, the president of a profitable foundry. While a tenant, Arthur met his future wife Irene Eberhardt—his landlord’s daughter. This relationship might have turned his financial fortunes, as well, as the Eberhardts could have helped provide the capital for Lawson to buy his shares in American Reflector.

In the years prior to his romance and cash windfall, it’s plausible that Arthur worked at Eberhardt’s foundry, or perhaps for Sosman & Landis or American Reflector in a creative role.

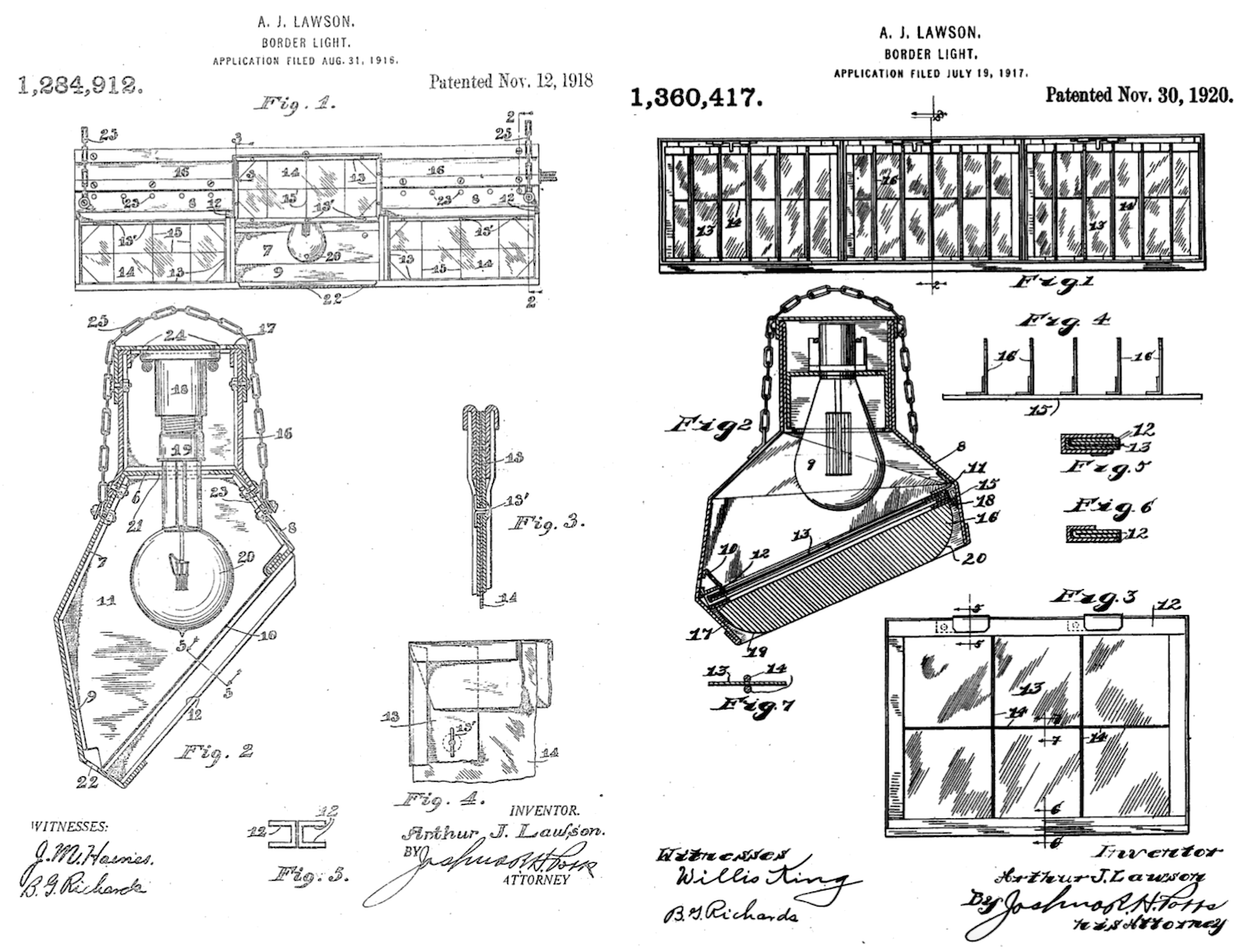

Evidence of Lawson’s potential engineering skills is scant but significant. Within his first year as a shareholder, he applied for patents on two inventions, both described as “border lights” (U.S. Patents 1,284,912 and 1,360,417). “My invention relates to improvements in border lights especially adapted for use along the border of a stage in a theater or as foot lights therefor,” Lawson wrote in his first application, which was ultimately approved in 1918. “The object of the invention is to provide a simple and effective construction of this character adapted to readily supply different colored lights for the stage.”

These patents suggest A. J. Lawson understood his new business intimately, but they also generate more questions, such as why he didn’t assign his inventions to the American Reflector & Lighting Co., and why the well seemed to run dry on new Lawson patents after 1920, despite two more decades at the helm of American Reflector. Was Arthur an unheralded genius or more of a workaday businessman? We don’t know.

We do know that by 1923, another new era was afoot. Former company president Charles Landis died from cancer that year, and with the subsequent liquidation of the old Sosman & Landis Studio, any of its remaining connections to the American Reflector & Lighting Co. were finally severed for good.

Following another building fire, Arthur Lawson had selected a new headquarters for the business at 100 S. Jefferson Street. Manufacturing was likely done there, but it’s also possible that some of it was outsourced, perhaps to the foundry of Eberhardt & Wagner (2357 Elston Ave.), which was now run by Arthur’s brother-in-law Fred Eberhardt, Jr.

Following another building fire, Arthur Lawson had selected a new headquarters for the business at 100 S. Jefferson Street. Manufacturing was likely done there, but it’s also possible that some of it was outsourced, perhaps to the foundry of Eberhardt & Wagner (2357 Elston Ave.), which was now run by Arthur’s brother-in-law Fred Eberhardt, Jr.

Consistently, though, the only other American Reflector executive regularly listed alongside A. J. Lawson in registries during the 1920s and ’30s was company secretary Frances Hallinan (later Stafford), a woman whose own census records suggest she may have merely been Lawson’s secretary in the mode of administrative assistant, rather than business partner (the 1940 census, for example, lists Frances as a “private secretary”).

In terms of product lines, American Reflector moved on to its next niche in the ‘20s, focusing less on the theater or the retailer, and more on the gallery wall.

“The Fixture that Lights the Picture,” read the tagline to a 1923 ad for the Art-O-Lite, American Reflector’s leading product for much of the mid 20th century, and the same artifact featured in our museum collection. “The foremost artists, homes, galleries and dealers have depended upon Art-O-Lite Reflectors for years. They consult us on all their lighting problems. You may do it too. We assume all responsibility by saying ‘try Art-O-Lite at our expense.’ Your nearest dealer has them or should. If not, write us.”

Ads like this continued to run in publications like The Art Digest well into the 1930s, and they provide just about the only clear insight into the company during the Depression.

[The Art-O-Lite from our collection, along with an Art-O-Lite advertisement from 1933]

In 1940, Arthur Lawson died at his home in La Grange, IL, aged just 57. The Chicago Tribune obituary noted that he was “prominent in the fields of indirect and stage lighting. He designed and installed the lighting systems now used in several of Chicago’s theaters.” Arthur and his wife Irene had eight children, several of whom took on roles with the business in the years that followed.

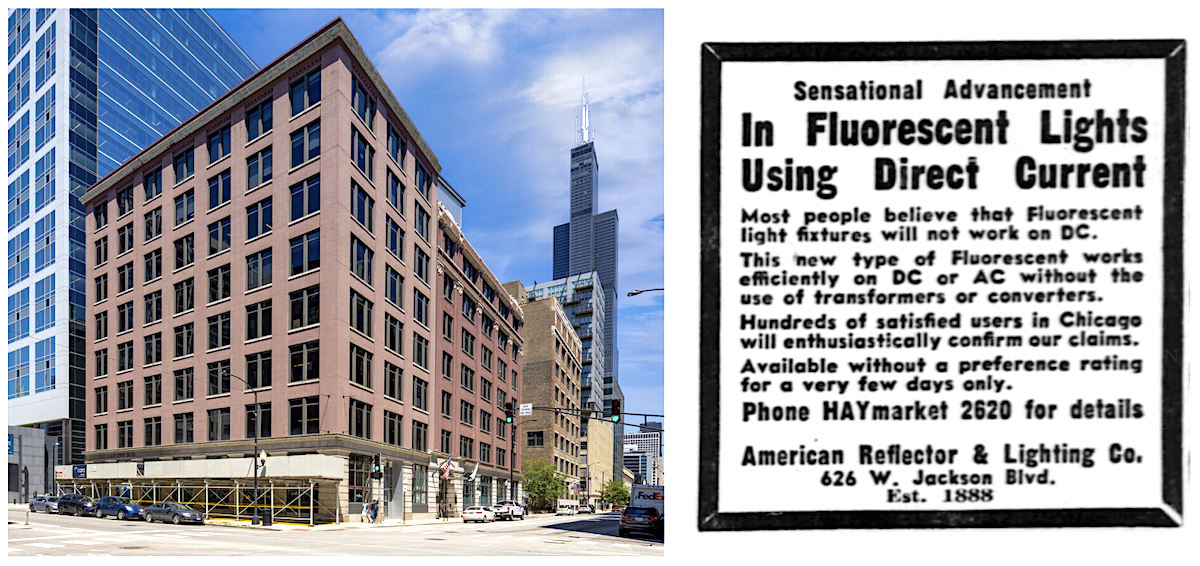

The widowed Irene Lawson, according to her grandson Paul Martin, took over ownership of American Reflector after Arthur’s death. Records also show that Irene’s brother Fred J. Eberhardt served in the role of president for a time in the 1940s. The business moved to 626 W. Jackson Blvd. through the 1940s and 1950s, and dabbled in new fluorescent lighting fixtures, promoted in at least one newspaper ad during World War II.

[Left: 626 W. Jackson Blvd, where American Reflector’s office was located during the 1940s and ’50s. Right: 1942 advertisement for the company’s “Sensational Advancement in Fluorescent Lights Using Direct Current.”]

Around 1960, the Jackson Blvd. location was abandoned in favor of a new office and factory space at 620 W. Adams Street, which Paul Martin fondly remembers visiting as a youngster.

“In the early 1960s,” Martin recalls, “when I was about eight years old, my father would drive me, my brother, and my grandmother [Irene Lawson] into Chicago on a Saturday, to the company building at 620 W. Adams Street. At the front of the building was the office, with its two large roll top desks and other office equipment, where my father would help my grandmother with paperwork. My brother and I would then walk through the double doors into the manufacturing area, and I always remembered the smell of mustiness, metal, and some kind of oily lubricant. My brother and I would sweep the floors, wipe down some of the machines, and empty unwanted pieces of metal and rejected fixture parts into the proper receptacles. Our biggest excitement came when Irene would let us operate the punch press. Sliding the appropriate piece of metal under the press, pressing the button, and watching the machine punch out a quarter size slug was exciting! We would throw the metal part into the parts bin and then start all over again. My brother and I always left with slugs in our pockets.” [Sadly, 620 W. Adams Street, like the majority of former American Reflector factory locations, is no longer standing]

Following Irene Lawson’s death in 1971, her sons John and Allan Lawson continued to operate the business, but its niche remained mostly limited to clients in the art gallery world. The employee count at the Adams Street office, according to an industrial register from 1967, was just six people.

A final office was established in 1981 in Manhattan, Illinois, but after the deaths of John Lawson in 1986 and Allan Lawson two years later, the American Reflector & Lighting Company reached its end, roughly on the 100th anniversary of its founding.

A final office was established in 1981 in Manhattan, Illinois, but after the deaths of John Lawson in 1986 and Allan Lawson two years later, the American Reflector & Lighting Company reached its end, roughly on the 100th anniversary of its founding.

“The operation ceased upon the death of my grandfather [Allan Lawson] in 1988,” explains Doug Lawson, “although my father [Michael Lawson] occasionally filled ‘special orders’ upon request for Wally Findlay Gallery, which was the company’s largest customer at the end.”

Fortunately, there are still Art-O-Lite fixtures out there bringing pictures to life, and with the help of the descendants of the company’s operators, the American Reflector & Lighting Company is beginning to have its story emerge from the shadows, too. If you have any personal history with the company or its products, let us know in the comments below.

Sources:

“Sosman & Landis: Shaping the Landscape of American Theatre,” by Wendy Rae Waszut-Barrett, PhD, DryPigment.net

Timeline, Shareholder Meetings, and other Documents provided by Paul Martin

“New Incorporations” – Chicago Tribune, March 24, 1893

“Treasurer Charles Landis . . . ” – Western Electrician, Nov. 27, 1897

“American Reflectors” – Western Electrician, Dec. 4, 1897

“The American Reflector & Lighting Company reports . . . ” – Western Electrician, June 3, 1899

“Show Cases” – Dayton Herald, March 20, 1912

“Arthur J. Lawson” [obit] – Chicago Tribune, May 26, 1940

“The Sosman & Landis Studio: A Study of Scene Painting in Chicago, 1900-1925,” by Randi G. Frank, BA, 1979

“Staging the Scottish Rite” – Die Verte Wand, Initiative Theater Museum, Berlin, May 2017

I worked construction & was the demo foreman on the Lake of the Ozarks Bagnall created the lake I have a bridge navigation light from the little Niangua bridge on county rt 5 The light has ADLAKE cast on the bottom swing open bottom to replace the bulb Did your company make this light

Is there a relationship between this company and Chicago’s Curtis Light Company, more known in the history of stage lighting. Their reflectors became the standard in the border lights of the type you feature here in one of the American Reflector patents. Curtis’ reflector for border lights was named the “X-Ray Reflector” leading to generations of stage lighting designers calling border light’s “X-Rays”. I was surprised that the curtis light company is not listed in your index of Chicago companies profiled. Its reflect ors were central to the whole “indirect lighting movement” that your text here touches on. While teaching theatre in Cincinnati I was surprised to see that our Theatre house lights used the X-Ray brand reflectors that were quite beautiful. I have one of the reflectors in storage somewhere. Unlike many of the other theatre reflectors the curtis x-ray reflectors were made exactly like glass mirrors with a coating on the back of curved glass.

I don’t believe there is any relationship between the two companies, but you’re quite right about Curtis deserving inclusion. The museum has been trying to acquire a good X-ray reflector for quite a while. It’s one of the many worthy companies that’s yet to be added to the roster. But soon! –Andrew Clayman, Curator

Hello. Doug Lawson here again. I believe I have some pictures and other memorabilia from one of the old shops in Chicago. I’m pretty sure they weren’t from the Adams St. location because my great grandfather (Arthur) was in one of them and he died around 1940. Your article says the shop wasn’t located on Adams St. until 1960. Incidentally, I learned a lot of things I didn’t know from your article. Anyway, if you are interested in the pictures, as well as some interesting facts, please reach out to me. Thanks

Lovely write up, Andrew! I am so glad that my research was helpful. One correction – the Sosman & Landis studio image is actually from my own theatre collection. It was taken from a sales catalogue, c. 1910. I also have a photograph that shows the exterior of the building at that time too, if you would like to include it in your article. In regard to the master electricians and electrical engineers at Sosman & Landis…I have just completed writing 93 biographies for Sosman & Landis employees, including some of their electricians. As in the past, much of my research is posted to my blog at http://www.drypigment.net

Sosman & Landis diversified their interests from the beginning of their partnership in 1876. In addition to the Sosman & Landis Great Scene Painting Studio and the American Reflector & Lighting Co., Sosman & Landis founded the Grant Panorama Co., the Tennessee Pottery Co., and the theatrical management firm of Sosman, Landis & Hunt. Both Sosman and Landis also invested in a variety of other business endeavors independently, such as health spas in the southwest.

How much is the reflector light at the top

Of the page worth? I have two of them

My name is Doug Lawson. I am the grandson of the last operator (Allan F. Lawson) of American Reflector and Lighting Co. The operation ceased upon my grandfather’s death in 1988, although my father (Michael) occasionally filled “special orders” upon request for Wally Findlay gallery, which was the company’s largest customer at the end. The fixtures were manufactured exactly the same way as the example shown until the very end. It has been many years, but I still think I remember how to build them from scratch. I really do appreciate that some people have taken interest in the company and it’s history in recent years.

Looks great Andrew.

Looking forward to your full write up.