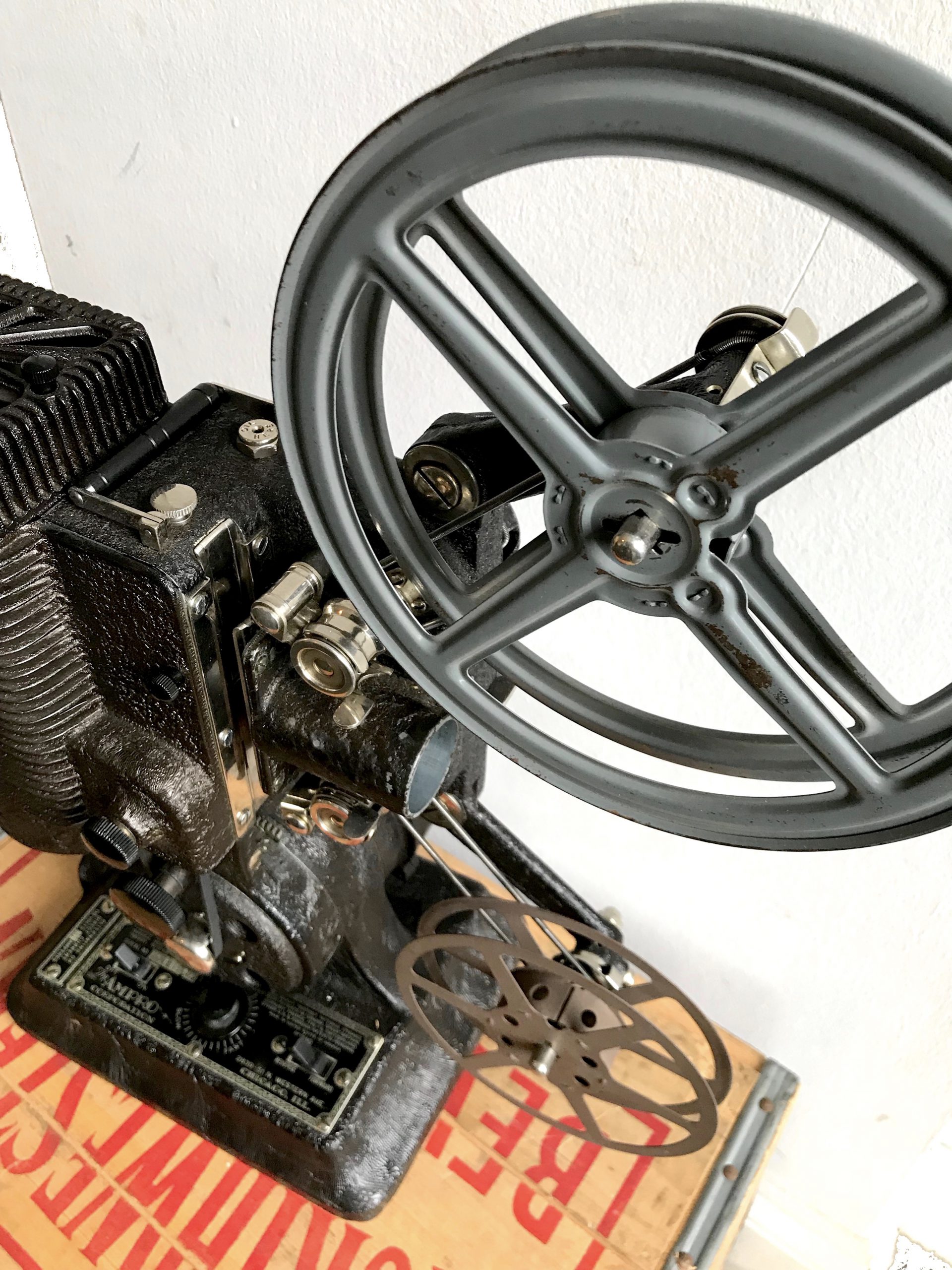

Museum Artifact: AMPRO Precision Projector, KS model, c. 1936

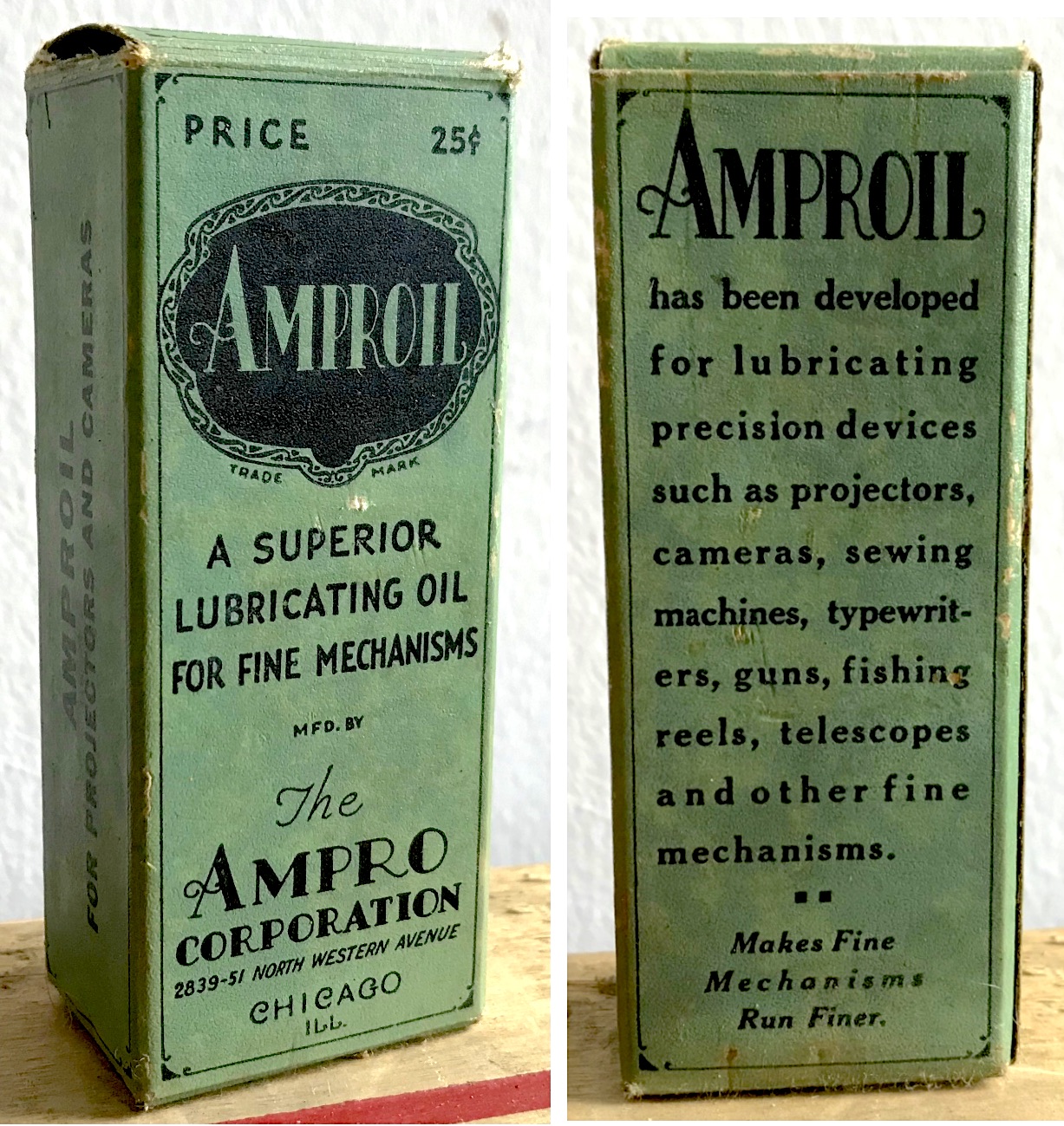

Made By: The Ampro Corporation., 2839-51 N. Western Ave., Chicago, IL [Bucktown]

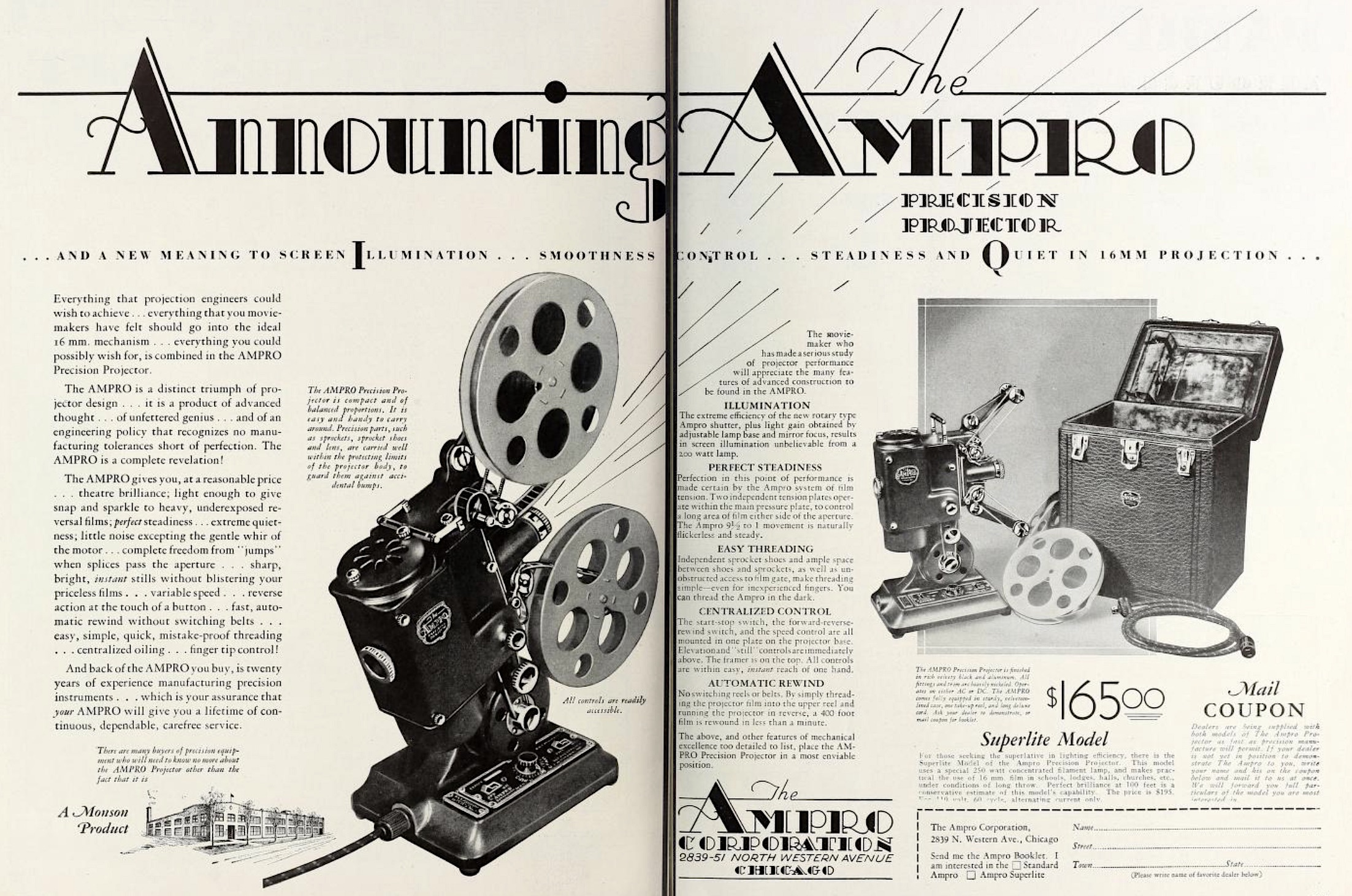

“Everything that projection engineers could wish to achieve . . . everything that you movie-makers have felt should go into the ideal 16mm mechanism . . . everything you could possibly wish for, is combined in the AMPRO Precision Projector.” —advertisement in Movie Makers magazine, April 1930

On a first read, the ad copy above comes across like a typical American tech company touting its latest premier product—seductive language full of pride and hyperbole. Re-read it in historical context, however, and the salesman’s voice starts to sound more desperate than confident.

This was the very beginning of the Great Depression, after all, and Chicago’s Ampro Corporation was trying to sell the general public on a $165 piece of equipment (about $2,500 in today’s money) that offered the fading novelty of silent movies just as the advent of talkies was all the rage. “It’s everything you could POSSIBLY wish for!!!” Please buy this thing!!!

This was the very beginning of the Great Depression, after all, and Chicago’s Ampro Corporation was trying to sell the general public on a $165 piece of equipment (about $2,500 in today’s money) that offered the fading novelty of silent movies just as the advent of talkies was all the rage. “It’s everything you could POSSIBLY wish for!!!” Please buy this thing!!!

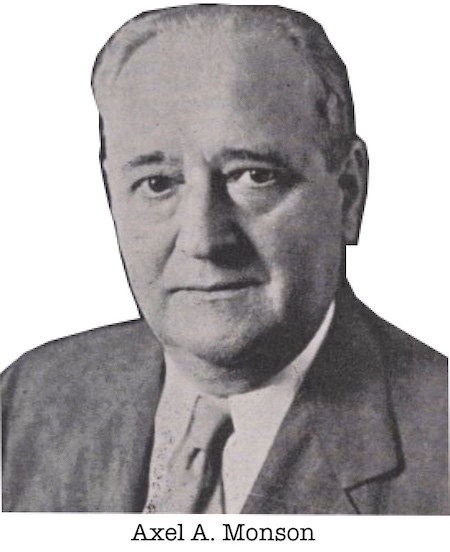

In a 1968 interview, Ampro’s 85 year-old founder Axel A. Monson (the name was an adaptation of “Axel Monson Products”) recalled the exact circumstances his company faced when the Precision Projector hit the market.

“In 1929 Ampro had 150 employees,” Monson told writer Dorothy Dent. “Before we were able to get on top of the Depression, we reduced our staff to 26 people, including the switchboard operator, myself, and the entire factory personnel. When machinery in our factory wore out, we could not afford to replace it. . . . At the end of each week, we spread out the bookkeeping sheets and considered them carefully. We paid suppliers what we could, and divided anything left among the employees. Many weeks our employees didn’t get paid at all!”

Monson didn’t set himself apart from his dwindling workforce, either. “I fed my family of four on a dollar a day,” he said, “sometimes as little as seventy-five cents.”

With all this in mind, it becomes particularly impressive to learn that Ampro not only survived these early years, but flourished in a highly competitive market over the subsequent quarter-century. They could never match local giants Bell & Howell in innovations or film projector sales, nor arch rival DeVry when it came to dominance in the field of educational film products. But with over 400 workers in its employ by the early 1950s, Ampro was an undeniable force—yet another representative of Chicago’s unmatched cine-quipment industry.

History of Ampro, Part I: The Universal Stamping & MFG Co.

Compared to Albert Howell, Axel A. Monson was something of a late-comer to the world of film. Born in Karlskoga, Sweden in 1883, he studied engineering as a youth and cut his teeth working under the guidance of his father at the local factory of Bofors; a famous arms manufacturer. While still a teenager, Axel was already leading complex fortification projects on the east coast near Stockholm, but his ambitions soon outgrew his homeland.

Monson emigrated to the U.S. in 1902, at just 19, briefly settling in Boston before joining the tool department of International Harvester’s mighty McCormick works in Chicago. By 30, he had risen to the level of superintendent there, but walked away in 1914 to launch his own business: the Universal Stamping and Manufacturing Company.

Monson emigrated to the U.S. in 1902, at just 19, briefly settling in Boston before joining the tool department of International Harvester’s mighty McCormick works in Chicago. By 30, he had risen to the level of superintendent there, but walked away in 1914 to launch his own business: the Universal Stamping and Manufacturing Company.

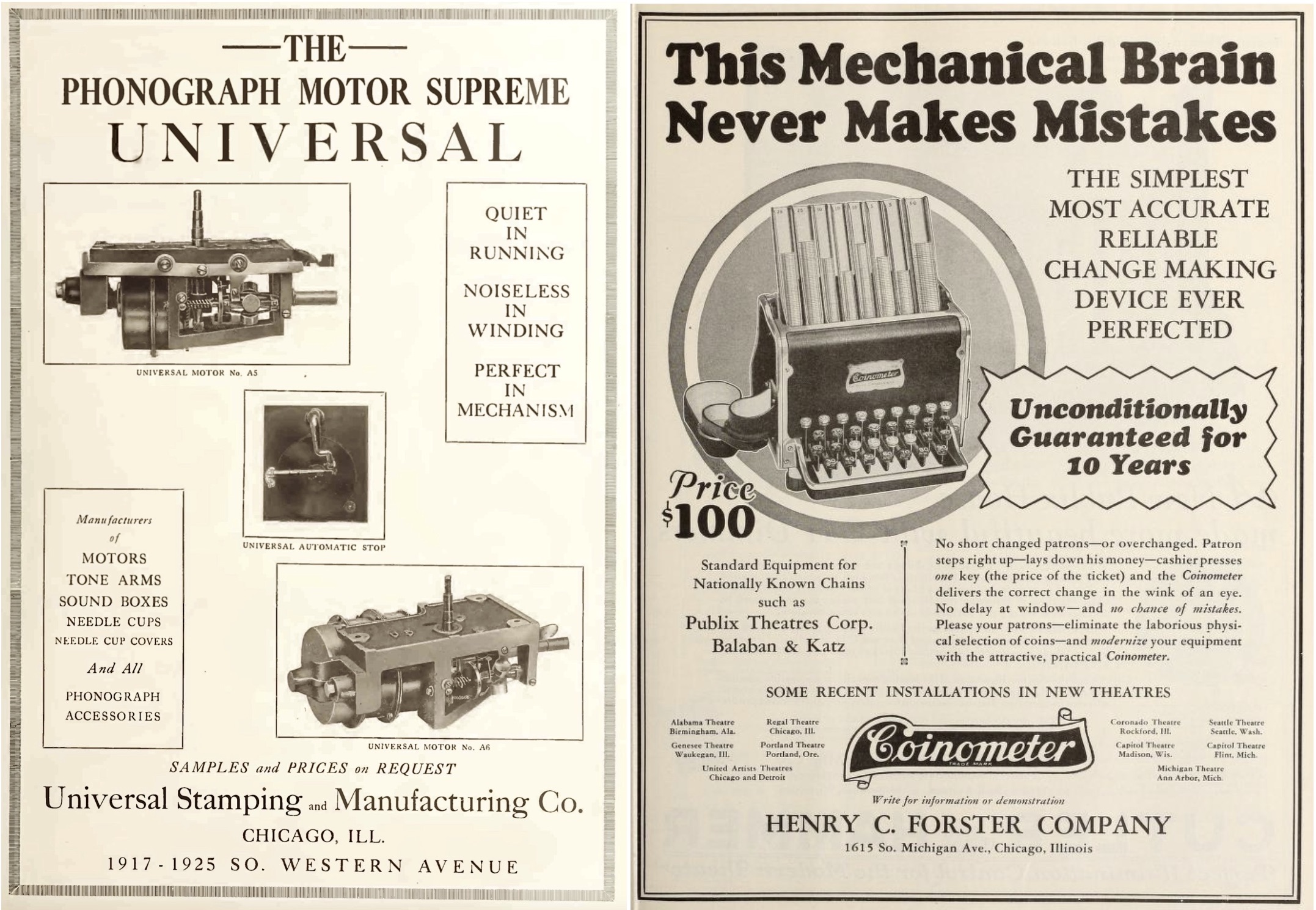

Universal was fairly successful right out of the gate, making high grade tools, stampings, and hardware for the likes of the Edison Electrical Appliance Co. and Stewart Manufacturing Corp., but it was really World War I that put the business on the map. Putting his old Bofors experience to work, Monson got Universal some important government contracts making components for the war effort, including specialized gun mounts for the 37mm M1916; a vital sharpshooting weapon.

With his wallet padded by the war’s end, Monson leased a new 36,000 sq. ft., two-story plant in 1919, located at 1925 S. Western Avenue—a building which is still standing a century later. From these new digs, Universal started making literal noise as a phonograph manufacturer—Monson’s first foray into the world of audio-visual equipment.

[Former Universal Stamping & MFG Co. plant at 1925 S. Western Avenue, as it looks today. Universal occupied the building from 1919 to 1926.]

[Former Universal Stamping & MFG Co. plant at 1925 S. Western Avenue, as it looks today. Universal occupied the building from 1919 to 1926.]

By 1920, the Universal Stamping & MFG Co. had supposedly become the “largest independent manufacturer of phonograph motors and parts in the world,” and they were now offering stock to the public at $10 per share.

“Make something and sell it! That’s the 20th century idea of making money,” the company exclaimed to its would-be stockholders. As part of that same pitch, it was noted that Universal’s earnings during its first five years had been “49% of invested capital,” and that their factory was “equipped to manufacture any ‘quality’ product—whether it be the most intricate technical device or a complete sewing machine or cash register.”

[Along with its own line of phonograph motors, tone arms, and other components, the Universal Stamping & MFG Co. also made a wide variety of products for other distributors, including the “Coinometer” change making machine sold by several businesses; in the ad above, the Henry C. Forster Co. of Chicago]

[Along with its own line of phonograph motors, tone arms, and other components, the Universal Stamping & MFG Co. also made a wide variety of products for other distributors, including the “Coinometer” change making machine sold by several businesses; in the ad above, the Henry C. Forster Co. of Chicago]

II. Ampro-pomorphizing

Just before turning 40, Axel Monson was elected president of Chicago’s Swedish Engineers Society (serving in the role in 1923 and 1924); a strong statement on the level of respect he’d earned less than a decade after going into business for himself. Shortly thereafter, in 1926, the Universal Stamping & MFG Co. relocated to a spacious new plant at 2851 N. Western Ave.; the same street as their prior factory, but a considerable five and a half miles to the north.

The larger plant soon reflected Axel Monson’s shift in focus from phonograph parts to film projection—specifically the budding field of equipment for “non-theatrical” use.

The larger plant soon reflected Axel Monson’s shift in focus from phonograph parts to film projection—specifically the budding field of equipment for “non-theatrical” use.

Joined by his lead engineer Abram Shapiro, Axel established a working relationship with Chicago’s Society for Visual Education (SVE), one of the first organizations dedicated to producing and promoting film for educational uses in schools. SVE was led by Marie Witham, who was about five years younger than Monson but similarly ambitious and savvy. An obvious oddity as a young woman in a tech field dominated by men, Witham had pulled SVE out of an economic tailspin caused by its first president Harley Clarke, and soon had deals worked out to make official SVE film and slide projectors with local Chicago manufacturers, including the Acme Motion Picture Projection Company and, of course, the Universal Stamping & MFG Co.

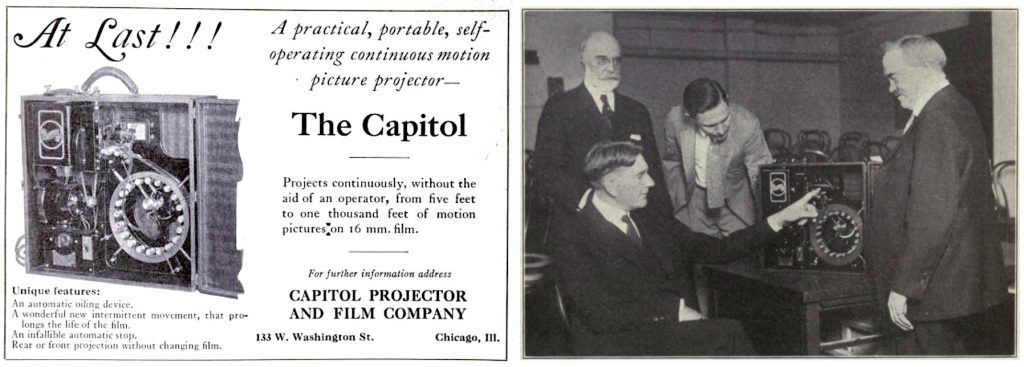

From 1924 to 1927, Universal was also the exclusive manufacturer of the “Capitol Continuous Projector,” distributed by the Capitol Projector & Film Co. (133 W. Washington St.). Invented by William C. Raedeker, the Capitol was something of a novelty. One of the earliest 16mm “self-operating” electric projectors, it could repeat a 7-minute film unattended for six hours, making it a favorite for retail window displays. It also was small enough to be sold with its own easy-carry briefcase for convenient portability.

[Left: 1925 ad for the Capitol Continuous Projector, made by the Universal Stamping & MFG Co. Right: A Capitol projector is admired by the U.S. Secretary of the Navy Curtis D. Wilbur (seated) and Charles Francis Jenkins (right), a noted movie projector pioneer and inventor.]

[Left: 1925 ad for the Capitol Continuous Projector, made by the Universal Stamping & MFG Co. Right: A Capitol projector is admired by the U.S. Secretary of the Navy Curtis D. Wilbur (seated) and Charles Francis Jenkins (right), a noted movie projector pioneer and inventor.]

“The distinguishing feature of the new projector,” according to a 1925 edition of Educational Screen magazine, “is an ingenious mechanism by which the film, as it unwinds to be projected, rewinds into the original reel, which is thus constantly of the same size. . . . This is the form of projector that it is believed solves the problem of the use of motion pictures in schools—visual education—because it eliminates the necessity of an expert operator, and because at a range of 15 feet, or within the confines of the smallest classroom, the picture on the screen or wall is as large as that secured at a distance of 70 feet by an ordinary projector.”

The Capitol Projector seemed destined for historical significance, but wound up entirely forgotten instead, as some mismanagement and hesitation from investors sent the Capitol Projector & Film Co. plunging into liquidation by 1927. In the aftermath—as the machine’s sole manufacturer—Axel Monson found himself uniquely qualified to pick up the torch and run with it.

“[Monson] had his own ideas about non-theatrical opportunities,” Educational Screen recounted in a 1943 issue, “and with this latest setback to the Capitol, he decided not to lose the benefits of experience already gained. So in 1927 he, together with his chief engineer A. Shapiro, began working on a machine which was to become known as the Ampro.”

[An Ampro Precision Projector in use, taken from Youtube video by rozwo r]

[An Ampro Precision Projector in use, taken from Youtube video by rozwo r]

III. Monson Precision

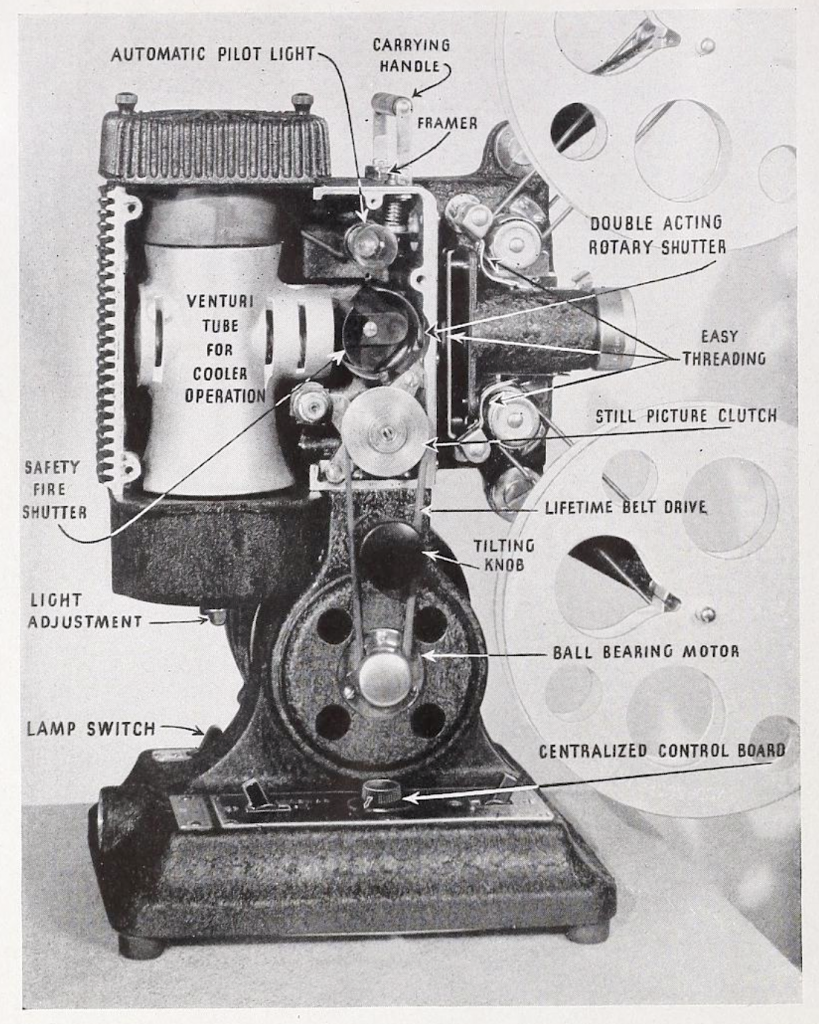

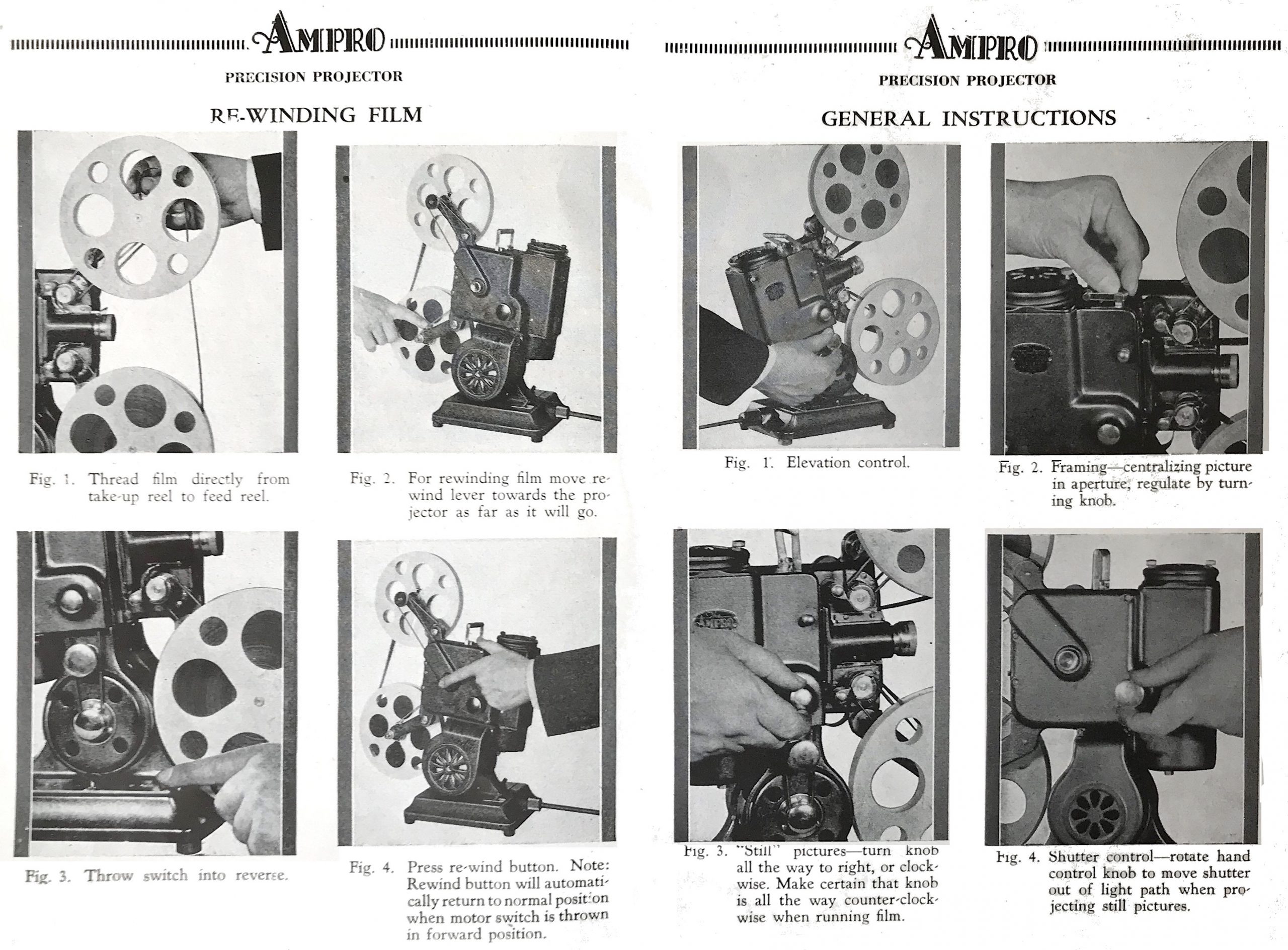

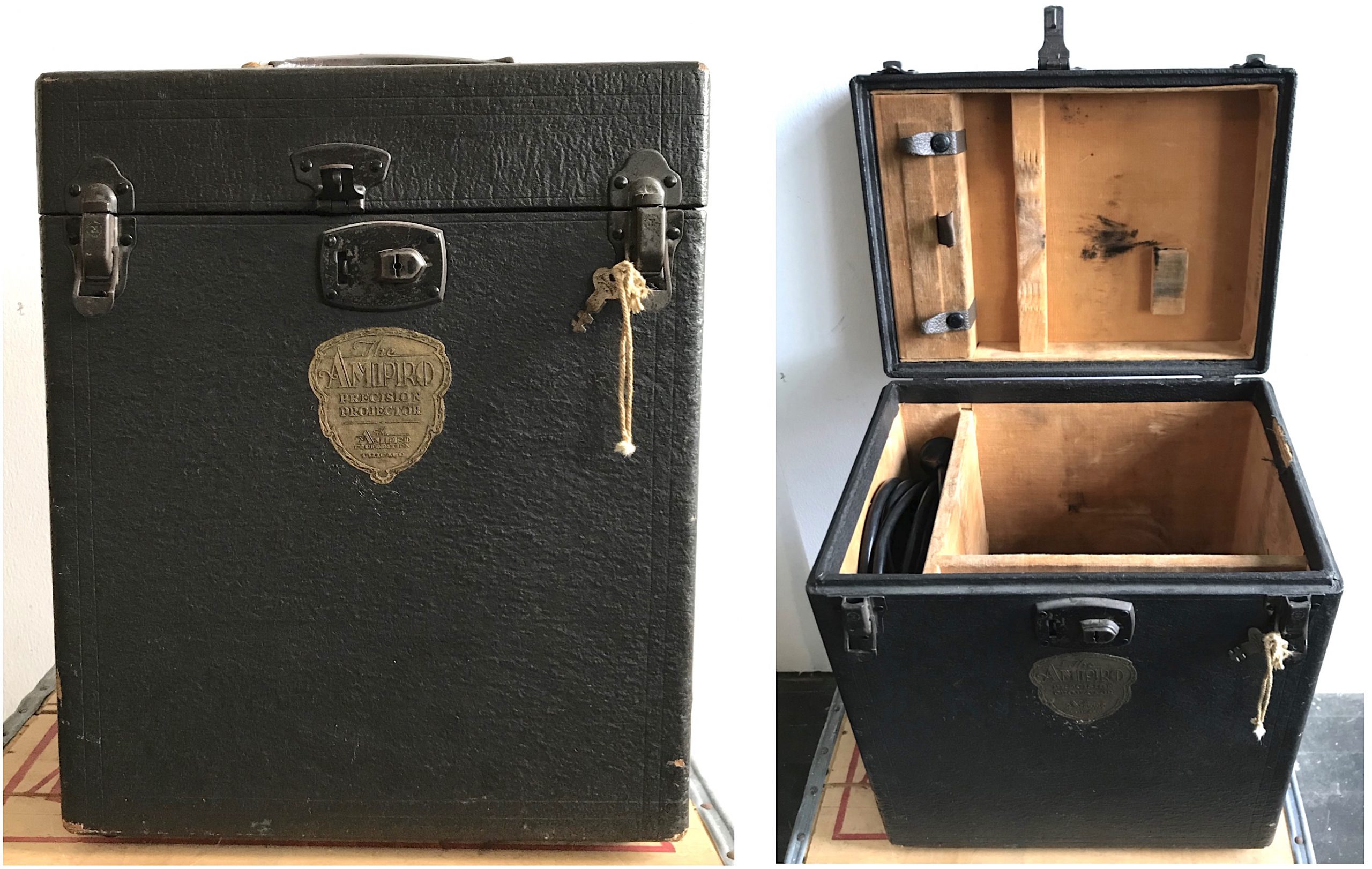

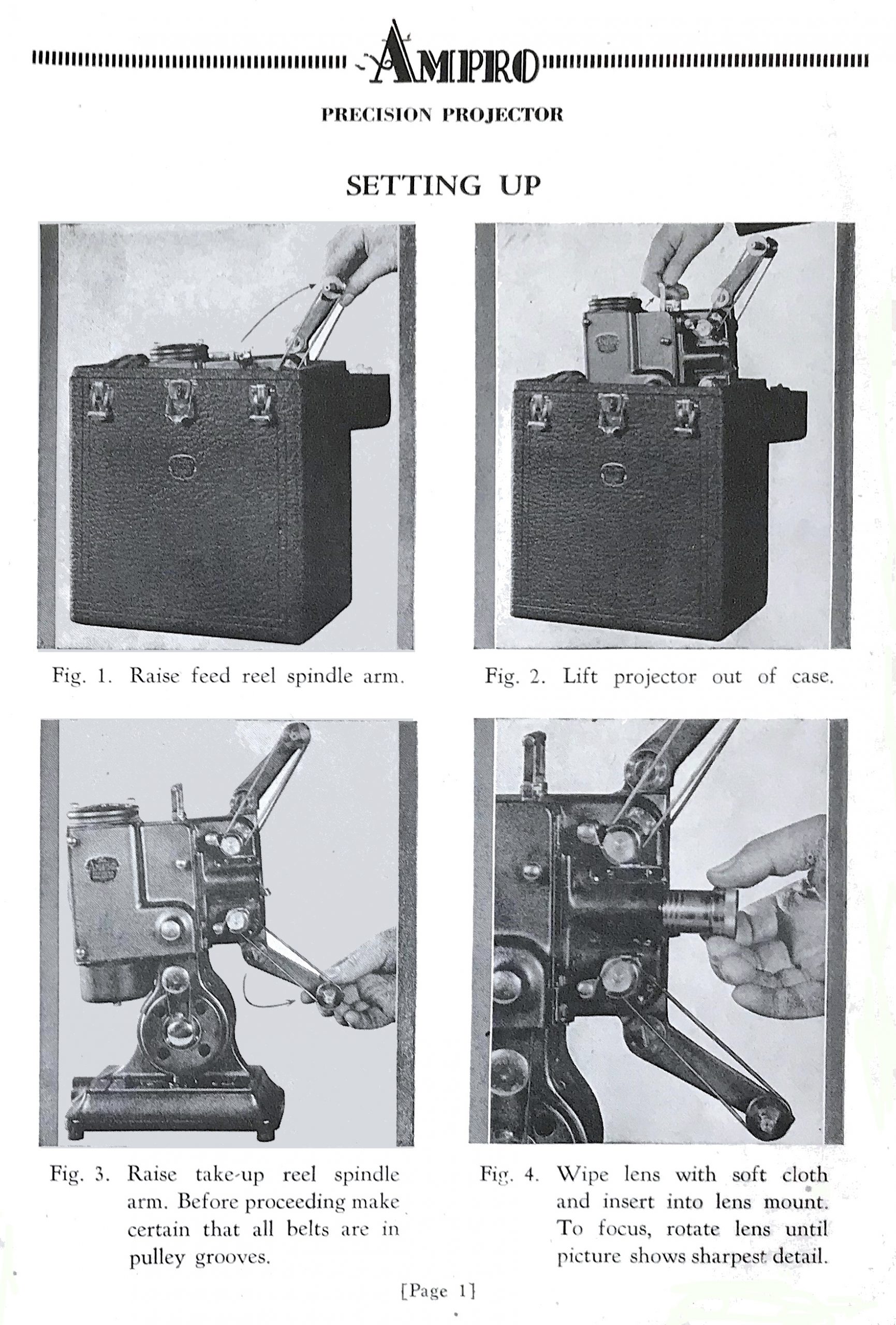

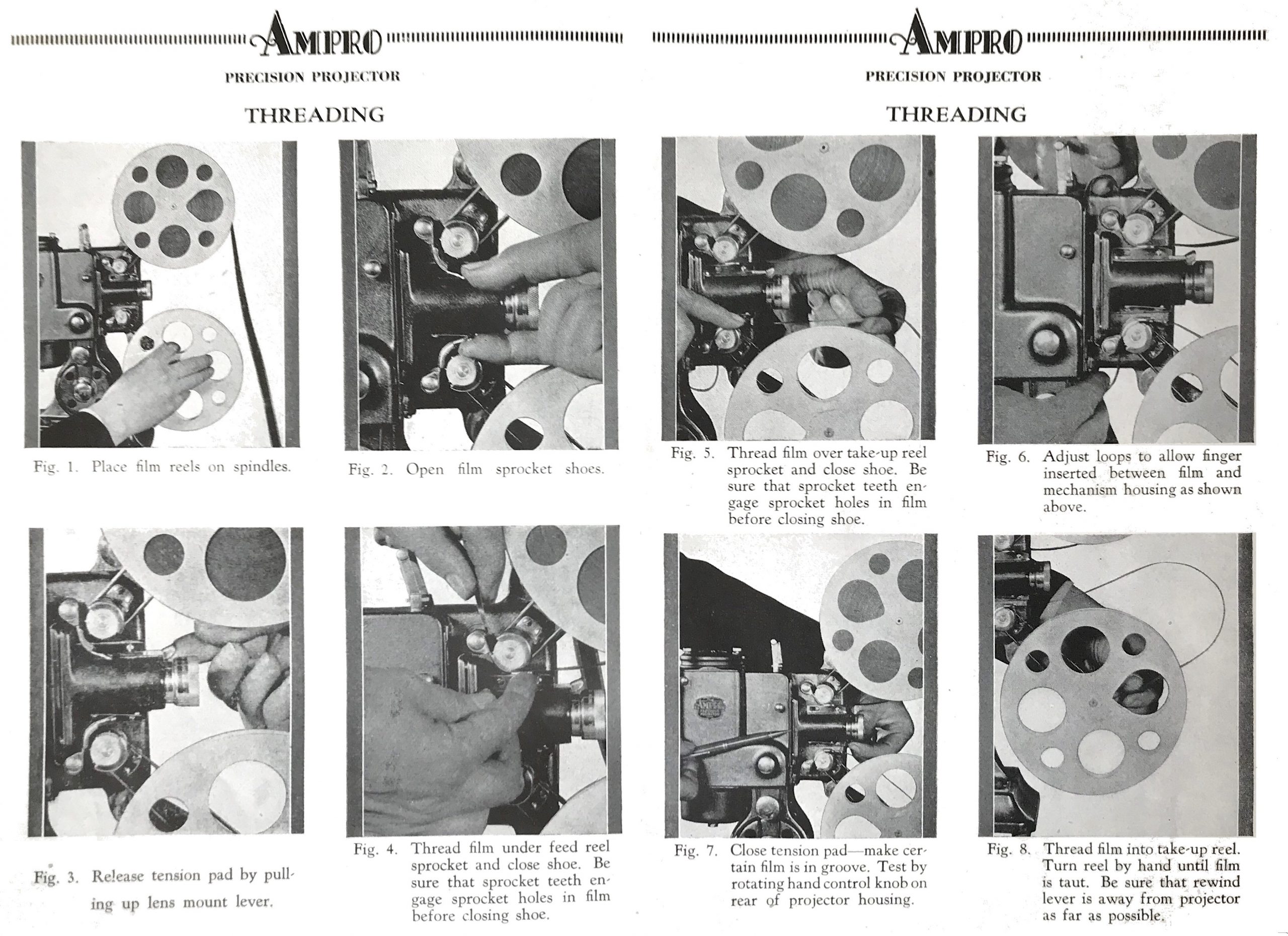

“AMPRO, the modern Precision Projector, is the product of progressive thought, experiment and research.” So sayeth the opening lines of the operation manual discovered inside the carrying case of the Precision Projector from our museum collection.

“AMPRO engineers held that there was a wide open opportunity for improved motion picture precision—that superior results could be obtained along with freedom from complication in design as well as operation.”

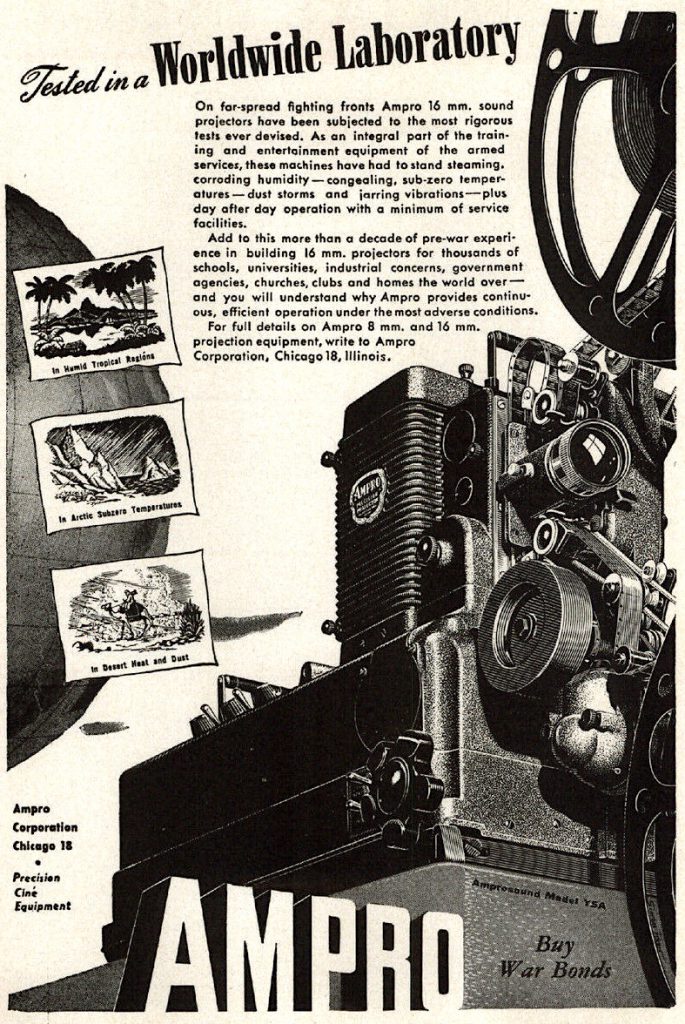

Backing up these claims, Monson and Abe Shapiro did file a handful of patent applications ahead of the Precision’s debut, and many of them were later granted by the U.S. Patent Office, including new developments in “rewinding mechanisms for cinematographs, “safety shutter for cinematographs,” “film tensioning means for cinematographs,” and “casing for cinematograph.” Shapiro also made inroads on a “cinematograph for sound films,” which ultimately led to the “Amprosound” projectors of the late ‘30s and 1940s.

Backing up these claims, Monson and Abe Shapiro did file a handful of patent applications ahead of the Precision’s debut, and many of them were later granted by the U.S. Patent Office, including new developments in “rewinding mechanisms for cinematographs, “safety shutter for cinematographs,” “film tensioning means for cinematographs,” and “casing for cinematograph.” Shapiro also made inroads on a “cinematograph for sound films,” which ultimately led to the “Amprosound” projectors of the late ‘30s and 1940s.

The particular KS model projector in our collection likely dates from around 1936, and while it was a “silent model,” many of Ampro’s 1930s machines were made to be convertible into Amprosound devices, enabling customers to jump into the talkie revolution without having to drop another 200 bucks ($3,000 after inflation).

According to a 1935 ad, the Ampro’s “K Series” projector “contains every improvement required for the finest projection of your 16mm films without professional skill. Theatrical illumination by the use of 750 watt lamp, superior optics, finned lamp house for cool operation under all conditions, automatic rewind to quickly and easily remove the tedium of rewinding films, reverse action for comic effects, still pictures which do not harm your films, quick operation, centralized control, flickerless pictures, framer for out of frame prints, the patented kick-back claw movement which spares the film from sprocket hole wear, interchangeable lenses to meet all conditions, deluxe carrying cases with complete accessories.”

The KS subset of the K Series also came with a “35mm super aspheric condensing system and large-barreled super objective lens of speed f/11.65,” if you’re a stickler for detail. The machine cost $160, and included a couple compatible reels and a bottle of a lubricating oil branded as Amproil.

Through the entirety of the 1930s, the Ampro Corporation operated as a subsidiary of the Universal Stamping and MFG Company, but with Axel’s son Harry Monson leading a successful nationwide sales mission on the projector front, the company soon found itself overcoming those initial Depression-induced pitfalls and gaining a loyal following among traveling salesmen, teachers, and industrial film makers. No longer a side venture, the projectors were now keeping Universal in business on their own, and in recognition of this, the entire company adopted the Ampro Corp. name in 1940.

[From Left: Ampro chief engineer Abram Shapiro, president Axel Monson, shipping room foreman C. Schroeder, and vice president Harry Monson, at a company dinner in 1947]

[From Left: Ampro chief engineer Abram Shapiro, president Axel Monson, shipping room foreman C. Schroeder, and vice president Harry Monson, at a company dinner in 1947]

IV. War Movies

“Ask the man who has seen it in action! Men who have operated Ampro 16mm sound projectors the world over will tell you almost unanimously that Ampro projectors have come through the grueling tests of war with the highest record of performance. This fact is important to know when you are selecting the 8mm and 16mm equipment for bringing into your home the vast libraries of educational and entertainment films.”—Ampro advertisement, 1944

“Ask the man who has seen it in action! Men who have operated Ampro 16mm sound projectors the world over will tell you almost unanimously that Ampro projectors have come through the grueling tests of war with the highest record of performance. This fact is important to know when you are selecting the 8mm and 16mm equipment for bringing into your home the vast libraries of educational and entertainment films.”—Ampro advertisement, 1944

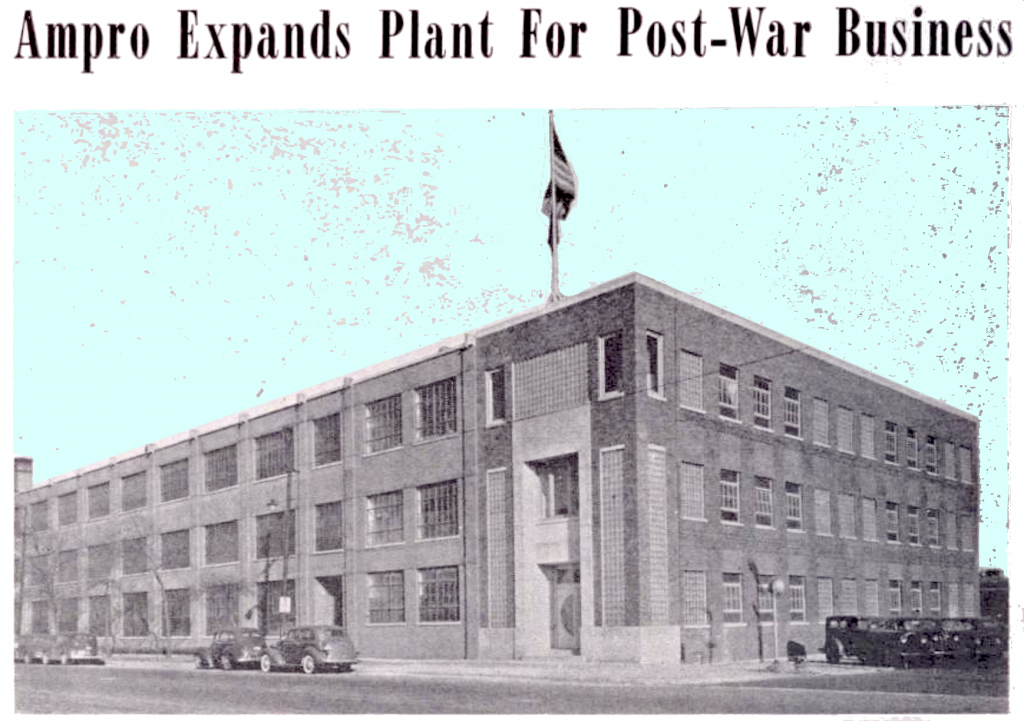

While Ampro still had an advertising budget during the war, it was more to keep their name in the minds of the civilian consumer. Production at the Western Avenue plant had shifted entirely over to government work since Pearl Harbor, ultimately leading to an expansion of the factory to keep up. Aside from making projectors specifically for military use, the plant also produced bombsight parts as a subcontractor to the AC Spark Plug division of General Motors.

At a luncheon at the Palmer House in 1944, AC Spark Plug’s general manager George Mann Jr. specifically praised the efforts of Ampro—along with fellow Chicago bombsight makers the A.B. Dick Co., Chicago Coin Machine Co., and Woodstock Typewriter Company—for their invaluable contributions in putting hundreds of sights into Allied bombers.

[In 1944, the Ampro factory at 2839 N. Western Ave. expanded both for military work and in anticipation of post-war civilian demand. This building is no longer standing.]

[In 1944, the Ampro factory at 2839 N. Western Ave. expanded both for military work and in anticipation of post-war civilian demand. This building is no longer standing.]

That same year, with Axel Monson now marking his 30th year in business and the conclusion of the war at least still somewhat in doubt, word broke that Ampro had a number of companies interested in acquiring the business and its patents. Sure enough, by the fall of ’44, Monson had agreed to a deal with the General Precision Equipment Corporation (GPE), a New York company that specialized in producing 35mm motion picture equipment for traditional theatrical use. For obvious reasons, they wanted to gain ground in the home movie field and Ampro was their ticket into the thick of that industry.

At first, news of the sale didn’t suggest any threat to Ampro’s Chicago employees. Though back to being a subsidiary, the Ampro name would carry on, its Western Avenue factory would remain in operation, and Axel Monson, Harry Monson, and Abram Shapiro (President, VP, and Secretary, respectively) would all be retained in their same management positions.

At first, news of the sale didn’t suggest any threat to Ampro’s Chicago employees. Though back to being a subsidiary, the Ampro name would carry on, its Western Avenue factory would remain in operation, and Axel Monson, Harry Monson, and Abram Shapiro (President, VP, and Secretary, respectively) would all be retained in their same management positions.

Once the war was over, however, the delicate balance between the Monson family business and its east coast overlords became apparent. While the Ampro men believed the connection to GPE would give them an avenue to a wider array of cinema products, GPE saw Ampro as a relatively small cog in its much larger machine.

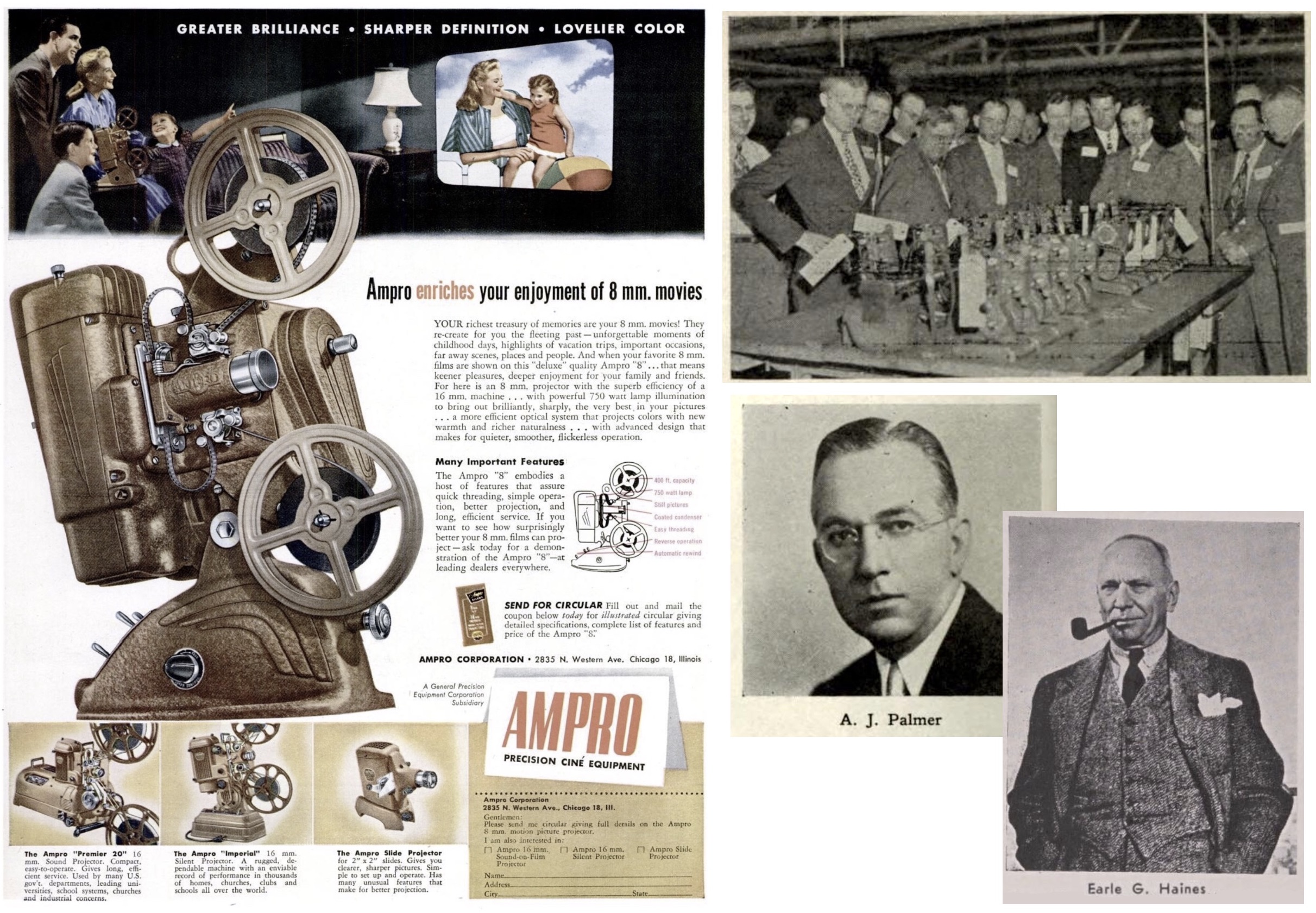

In 1947, 64 year-old Axel Monson retired from the president’s post with Ampro, staying on briefly as chairman and consultant. Rather than his son Harry taking over the presidency, though, that role fell to a General Precision executive, A. J. Palmer. This was a pretty clear statement on where the business was headed.

Less than a year later, Harry Monson announced his own resignation from the company he’d spent 23 years with, and instead joined his un-retired dad in a new tape recording venture called Senior Sounds, Inc. When that business tanked, Harry and his younger brother Edgar Monson launched the Monson Manufacturing Corporation at 6059 W. Belmont Avenue, with papa Axel serving as a consultant. This firm made resistors, capacitors, and “other electronic components,” but appears to have fizzled out by the 1960s, as well.

[Left: 1947 Ampro advertisement. Top Right: Dealers touring the Ampro factory in 1947, watching a bank of projector heads getting a test run. Bottom Right: General Precision Equipment executives A. J. Palmer (VP) and Earle G. Haines (President). Palmer replaced Axel Monson as Ampro’s president in 1947]

[1955 newspaper ad seeking a man for electronic assembly work at the Monson MFG Corp., 6059 W. Belmont Ave. The short-lived company was founded by Axel Monson’s sons Harry and Edgar.]

V. Preserved on Tape

The Ampro Corporation didn’t survive to see the 1960s, either, but the departure of the Monson family didn’t immediately crush the business. In fact, the late ‘40s and early ‘50s were something of a second golden age for the brand.

New president A. J. Palmer and GPE topman Earle G. Hines had specifically acquired Ampro out of appreciation for the way the U.S. military had successfully utilized film projectors in their training programs. “The successful use by the armed forces on a great and varied scale has shown educators and industrial concerns as never before, the rapidity with which information can be imparted to groups of students by this method,” Hines said shortly after the acquisition. “Undoubtedly use of visual aids to educational programs will, when peace comes, be greatly stimulated by this experience.”

[An Ampro Precision Projector in use, taken from Youtube video by rozwo r]

When peace did come, that prediction certainly came to pass. Unfortunately, Ampro was no longer quite so unique in the products or services it offered. In Chicago alone—the epicenter of all motion picture technology—there was the aforementioned Bell & Howell, SVE, and DeVry, as well as movie projectors by the Revere Camera Co. and Excel Movie Products, slide projectors by GoldE MFG Co. and O. J. McClure Talking Pictures, screens by Da-Lite Screen Co. and Radiant MFG Co., filmstrips by Encyclopedia Britannica Films, reels and cans by Compco Corp., and on and on.

“If Hollywood ever gives a movie Oscar for the best performance in producing motion picture equipment,” Tribune scribe Anthony Wirry wrote in 1953, “Chicago should easily win the award.”

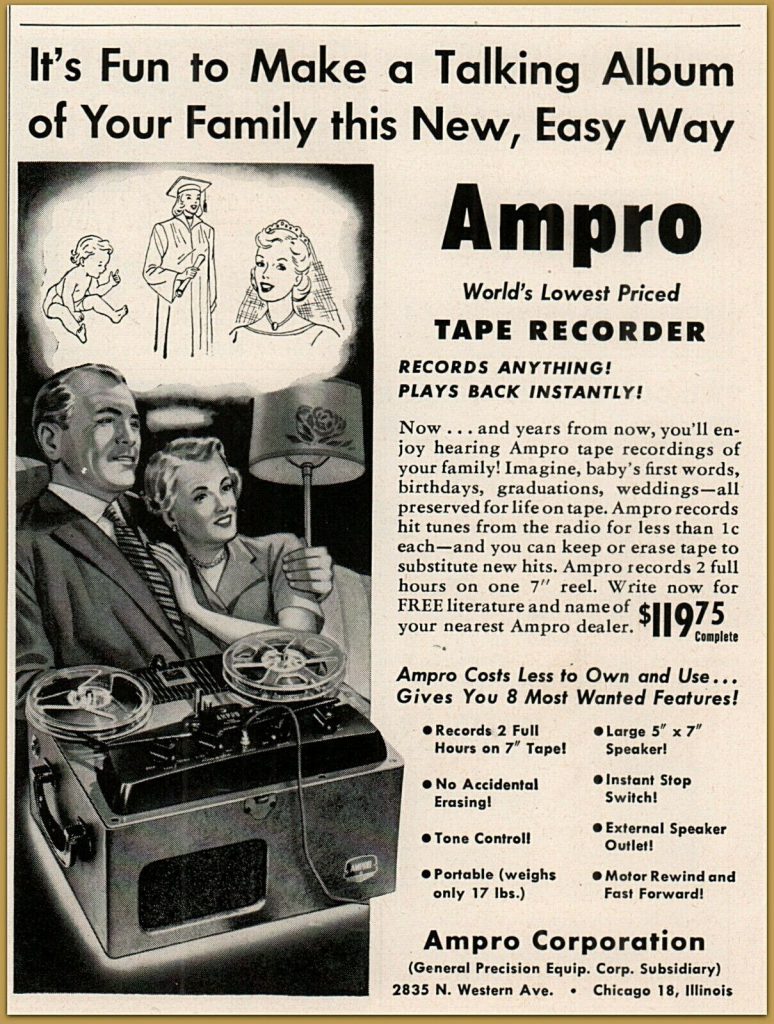

Around this same time, dare it be overlooked, was the explosive arrival of television; which instantly put a sort of invisible “sell by” date on every post-war film projector entering the market. If you were in this industry and weren’t called Eastman-Kodak, you needed to diversify. Towards this end, many of the Chicago companies, including Ampro, placed their bets on new tape recording technology.

In 1951, Ampro advertised what it called the “World’s Lowest Priced Tape Recorder,” a reel-to-reel machine that adapted much of the functionality from the company’s old Amprosound projectors—motor rewind and fast forward, instant stop switch, carry-case portability, etc.

In 1951, Ampro advertised what it called the “World’s Lowest Priced Tape Recorder,” a reel-to-reel machine that adapted much of the functionality from the company’s old Amprosound projectors—motor rewind and fast forward, instant stop switch, carry-case portability, etc.

“Now . . . and years from now, you’ll enjoy hearing Ampro tape recordings of your family!” one ad read. “Imagine, baby’s first words, birthdays, graduations, weddings—all preserved for life on tape. . . . 2 full hours on one 7” reel.”

As always, Ampro made a quality product, but the competition was brutal. Again, Chicago produced many of the leaders in the genre—not only camera pros like Bell & Howell and Revere jumping into the taping game, but dedicated recording specialists like WebCor, Magnecord Inc., and the Pentron Corp. (which had taken over the former plant of Axel Monson’s short lived Senior Sounds Corp. at 221 E. Cullerton Ave).

Ampro still had 400 Chicago workers on staff by 1953, but after its parent company General Precision acquired the camera manufacturer Graflex in 1956, the decision was made to move all of Ampro’s production to the Graflex factory in Rochester, New York. Despite a 30-year track record making quality, long-lasting A-V products, the Ampro name didn’t survive its move east, unceremoniously scrapped by 1958.

[Left: An Ampro authorized tape recorder dealer sticker. Right: Liberace endorsing the Ampro Hi-Fi Two-Speed Tape Recorder in 1954. By that point, manufacturing had moved to Rochester, NY, and Ampro’s remaining Chicago address was an office at 1345 Diversey Parkway]

[Left: An Ampro authorized tape recorder dealer sticker. Right: Liberace endorsing the Ampro Hi-Fi Two-Speed Tape Recorder in 1954. By that point, manufacturing had moved to Rochester, NY, and Ampro’s remaining Chicago address was an office at 1345 Diversey Parkway]

The General Precision Equipment Corp. was purchased in its own right by Singer (the sewing machine folks) in 1968, further burying any hope of an Ampro revival.

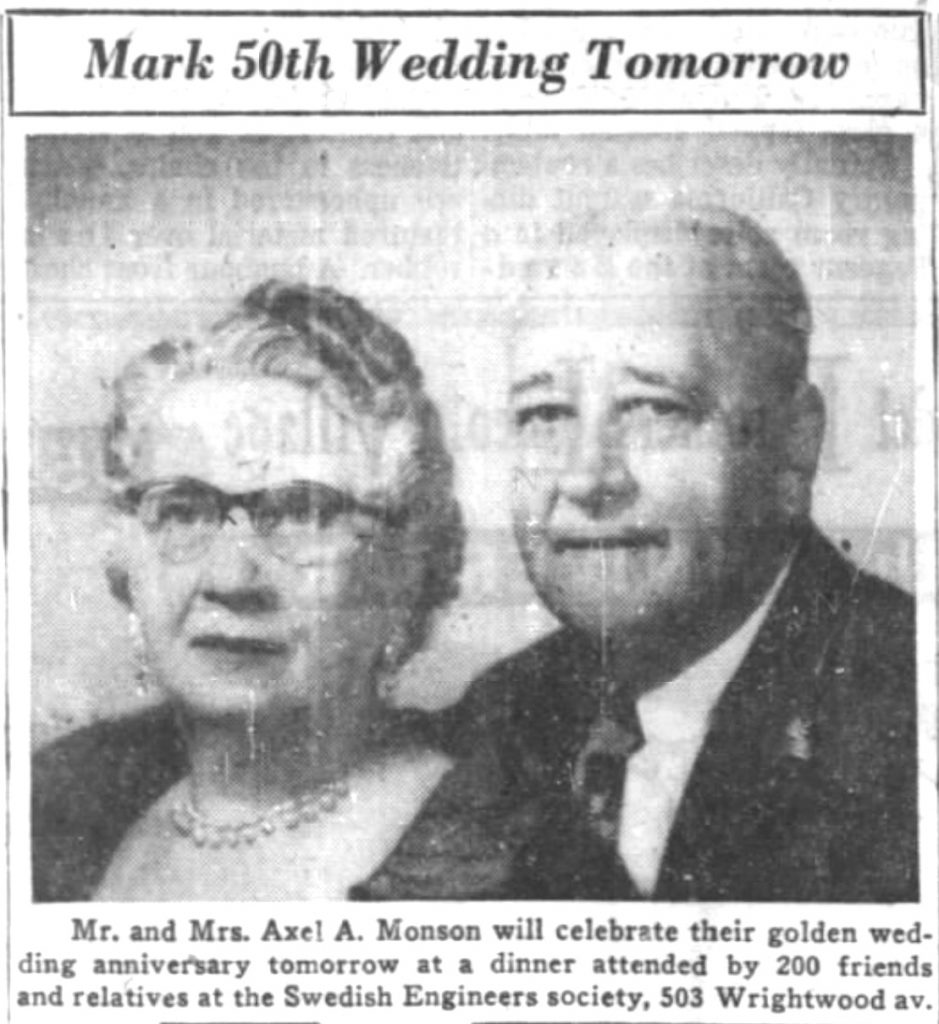

Axel Monson died in 1971 at age 87, leaving behind his wife of 65 years, Anna, who’d followed him from Sweden at the turn of the century. Years earlier, Axel had been awarded the Order of Vasa by the King of Sweden—a special recognition given to Swedes who’d provided particularly outstanding service in a range of fields, including technological.

Harry Monson became a stockbroker after the Monson MFG Corp. folded, and died in 1981 at 74.

[Tribune photo noting Axel and Anna Monson’s 50th wedding anniversary, 1955]

SOURCES

“Birth of the Ampro” – Educational Screen, April 1943

“The New Ampro Precision Projector” – American Cinematographer, March 1930

Landmarks in Learning: The Story of SVE, by Dorothy Dent, 1969

“General Precision Acquires Control of Ampro Corporation” – American Cinematographer, October 1944

Bombsight manufacturing for AC Spark Plug – Chicago Tribune, Nov 11, 1944

Factory expansion – Popular Photography, May 1944

“Accepts High Post” (Palmer replaces Monson) – Evening Telegraph (Dixon, IL), July 3, 1947

“Chicago Rates Oscar in Movie Camera Field” – Chicago Tribune, March 6, 1953

“Mark 50th Wedding Tomorrow” – Chicago Tribune, April 28, 1955

The Evolution of American Educational Technology, by Paul Saettler

“Universal Stamping & Manufacturing Company has leased . . . ” – Chicago Tribune, Jan 29, 1919

Universal Phonograph ad – Talking Machine World, May 15, 1919

“Where There’s Manufacturing There’s Money” – Universal stock pitch, 1920

“The Swedish Engineering Society’s New President” – Svenska Tribunen-Nyheter, Jan 31, 1923

“Self Operating Motion Pictures” – The Educational Screen, October 1925

Archived Reader Comments:

“In 1990 I was lucky enough to meet one of the chief Ampro product engineers Frank B. Dibble who was then living in Glastonbury CT but driving through Chicago with his wife on their way to a Christian scientist convention. He explained he originally worked for General Precision in Rochester NY in the late ’40s but transferred to ampro’s Chicago plant to engineer their version of the military JAN projector (my particular topic of interest). How I originally tracked down Mr. Dibble though is another story in and of itself” —Gregory Feret, 2020

“What a splendid and detailed presentation on the silent Ampro. I shall link to it from my website – no way I could match this! ” —Martyn Stevens, 2019

” —Martyn Stevens, 2019

“A splendid presentation of an outstanding product line come from the Creative Spirit, as partnered with the finer of Commercial Impulse.” —James Miller, 2019

Hola herede un ampro imperial y lo estaba limpiando y abrí la tapa lateral donde esta la bombilla grande y moví los lentes qué están al lado de esa bombilla y ahora no se en que posición van los dos lentes qué tienen un resorte en el medio sujetandolos si alguien puede decirme en que posición van se lo voy agradecer. Muchas gracias

Hello, inherited an Ampro 16mm projector Model K-GP, Serial 43535 with case and other original accessories from early 50’s I believe. (Ampro oil, projector lamp, lenses)

Good condition. Runs well other than some excessive noise. As a kid my grandparents would play Mickey Mouse, Jack Frost cartoons for us grandkids. Unfortunately the film had Vinegar syndrome and could not be saved. Other family film I was able to convert to digital just in time. Anyone know anything about this model projector? Not sure what to do with it other than keep storing it until I’m gone – then someone else can decide what to do with it. I’m guessing my grandfather bought it from Sears back then. He was a true Sears customer. Thanks for any comments! David

I am going to restore to Magnetic Sound Ampo 16mm projectors. Magnetic Ampros are rare but equally as scarce is the Ampro recording amplifier that I am looking for. If anyone knows where I might find one, that would be a nice addition to the display. This is for The History of Recorded Sound Foundation in Arcadia, CA. I also service RCA 16mm equipment. This is also the home of the phonograph record division of Western Electric (Westrex) Corp.

I found an Ampro 16mm precision projector model No. KD-19912. It runs and the bulb still works. It needs cleaned and the motor sparks a bit. I’d love to watch some silent films on it but I don’t feel safe using antique films until I know for sure how to use it. I can’t find a users manual anywhere online. Could you help me?

I am looking for an operating manual for an Ampro Precision 8mm projector, Model # 11221.

Can you please direct me to a source?

Thanks, Randy Weisser

Hello, I have an Ampro salesman repeating projector, serial #779 ,model# At-2(dl-25) . It also came with a Craig senior editor . They both look brand new although there cases have some wear. Could you please be of assistance in helping me determine their worth? Yours truly Bernie

Hi I have just inherited a set of ampro projector electrical machines and have managed to work out what some of the pieces are for but can’t work out what one piece is for it is a metal box with a long plug wire coming out of one side and like a four pin adaptor with long wire on the other side. I would be grateful if any of you know what it is and what it’s used for

I have a Ampro precision projector with case, like new. Ser # 21681 do you know the age and if its worth much money.

High my name to Steve. I own an a pro projector serial # A8 22825. I have never turned it on because there was no cord when I bought it. I would like to find an original cord. Anybody help me ? Thanks, steve

Hello all, I am looking for Blueprints of this machine, any and all help would be appreciated. Thank you.

I am Abram Shapiro’s daughter. My father held many of the patents for the equipment he developed and designed. He, also, was president of the Swedish Club at one time, even though he was Jewish. My father loved the Munsons. When General Precision took over, they wanted my father to stay on as President. But my father refused their offer. He so loved the Munsons…he could not stay on without them. I think he felt it would be disloyal in some way. Ampro had a little studio at the plant, and they made movies there. We always say my father was another father besides ours. We say he was the father of simulators and video games. He got an award from the Navy for the on-the-ground training modules for training belly gunners. Later, when I was in high school, driver’s training included simulators that worked with film. My father invented one of the earliest automatic slide projectors after leaving Ampro. He, also, invented some juke boxes and vending machines, but he burned the blueprints after people from the Chicago mob made an offer to manufacture them. Just before we entered the war, my father went through Europe, helping different allies learn to use film equipment. Resistance fighters hustled him off a train platform and whisked him away to foil a kidnapping plot by the Germans. Even though he kept working for many years, he was never as happy as he had been at Ampro with the Munsons. They were such good people.

This is wonderful information, Paula. Your father sounds like an incredible person.

Where can I find replacement parts for my Ampro precision projector. I need a new main belt and a lens mount lever to release the tension pad.???

Hello

I just inherited and AmPro Precision projector and am interested in finding out about it.

There is a good chance that I will sell it so I will also like to know it’s approximate value.

It runs forward and reverse and the bulb works.

There is an extra one that looks perfect as well as two reels.

The case is original but has quite a bit of wear.

It has been sitting unused for at least 30 years.

Thank You

It is labeled “Model and serial number J-19058”

I have an Ampro optical/Magnetic projector. I would like to find the recording electronics for the magnetic track. for it. I have only seen them in the Ampro Catalog. it is for our History of recorded Sound Museum in Arcadia, California.

I have a 1930s Ampro Precision Projector. The tube will not illuminate. I have an extra tube so I know I’m dealing with a “double tab mount” yet I cannot get the old one out. Suggestions?

imemories.com will digitize 16mm. I don’t know yet if I recommend them but I am sending in my 8mm film. If it goes smoothly, I will send in my 16mm films. I just love answering years old questions.

I inherited my 16mm Ampro Stylist projector from my father in 1970 with a number of 12′ reels of homemade movies. Recently I wanted to have them digitized to share with our whole family, but the services said they don’t handle that large of reels to convert.

So I thought the easiest way to convert these reels would be to setup the projector and view what was on them. I am at a loss without a instruction book on “how to thread and setup the projector”.

I know the projector worked the last time my father used it.. . . . but being stored for 50 years there’s a good chance it needs a tuneup or serious lubricating to function correctly.

If I could get someone to email me photos of the Manual ( Set-up pages and where I might get the correct part # for repairing the parts of this projector) — It would be much appreciated. Here’s my cell number to contact me 702 289-8282, Would appreciate any help. Thx

Im proud to own an Ampro Y model 16mm projector. More after to read this beautifull story. Even I have the service manual where is stated all the topics, measures, etc in order to put it back in service after a failure. The model Y I think was used at battle fronts. The main was adquired at Argentina(where I live), serial number 25169 and I got from 1993. From the beginning work perfectly, I just rebuilt the condensers from the amplifier. Even I runed a movie on it few hours ago, impact me the precision on screen, the silent running, the sound. My best wishes to the inventors and workers who made it.

My last asking is I like to get the operator manual of the Y projector because the main is missing from the box.

best regards,

Oscar

I found an Ampro Century 5 projector. The machine runs fine but no sound. I have determined the exciter lamp is working but nothing when the light beam is broken . The cord that connects to the amplifier has a 3 pin female end which goes to the sound tube , but the tube which the exciter lamp shines is empty. Does anyone have a parts list and or manual ? Any advice would be appreciated. This machine is beautifully designed and built, I would love to get it working.

Best regards,

James

Dear, I have an Ampro Y model proyector. Almost same than your. I removed the connector you mention and taked a photo from the phototube inside. is an RCA 927 vacuum photo tube. If I can attach O can show you. Even I have the repair manual for the Y model. My recommend is to remove the amplifier and recap it, both, paper capacitores and electrolytic ones .

I tested my photocell by connecting it, IIRC, to an turntable/cartridge amplifier input, it worked.

Harry Monson was my Great Uncle. Growing up I would hear tidbits about the Ampro company but this short read was by far one of the most detailed accounts of the company history I have seen. Reading about how Harry lead a national sales effort to promote the Ampro products reminded me of a family story I’ve heard more than once . . . On one of their first dates, “Uncle Harry” picked up my Great Aunt and future wife Olive Knutson. To Olive’s dismay, she had to sit in the back seat as Uncle Harry had removed the front passenger seat to accommodate equipment and literature he was using as a salesman for Ampro. Eventually they married and went on to live a long and happy life together in Lincolwood, Il.

That’s a great story, Wayne. It really helps paints a picture of how dedicated Harry was to his work. Even romance had to take a backseat for a while. 🙂

I have 3 16mm AMPRO projectors in my collections. Any idea of where to find spare parts thank you

I have recently been tasked by a friend to get a Ampro Precision 16 mm projector running so they can watch film taken by her father. It has been in it’s case and stored for many years. The unit looks like new and although the motor runs the belt is loose and slipping. I have no manual or paperwork to tell me what the belt # is to order one. Can you be of any help? I would love to get a manual possibly with part numbers. Belts are available on Ebay.

I have one that is 8 and 16 mm my name is Tricia