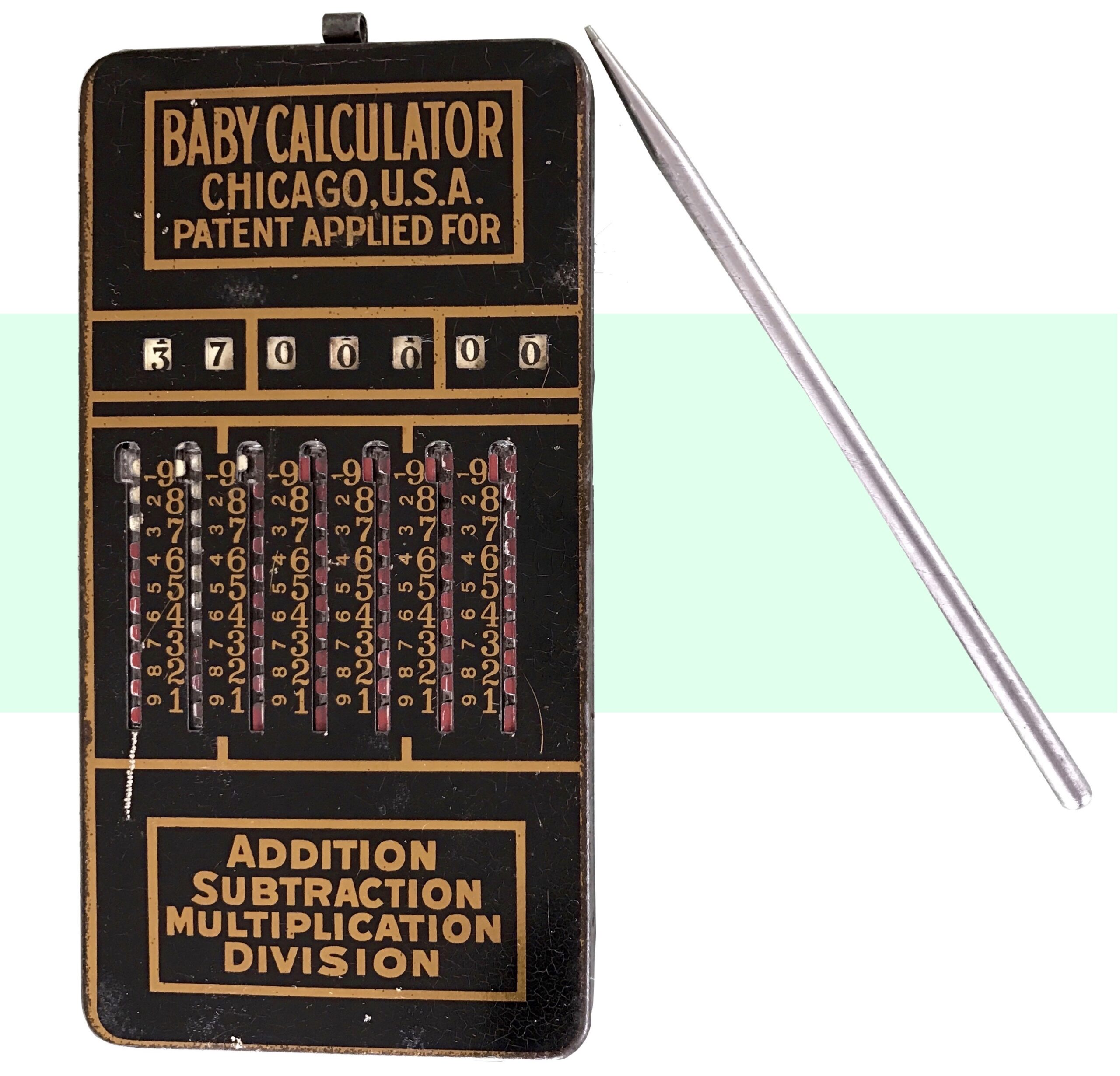

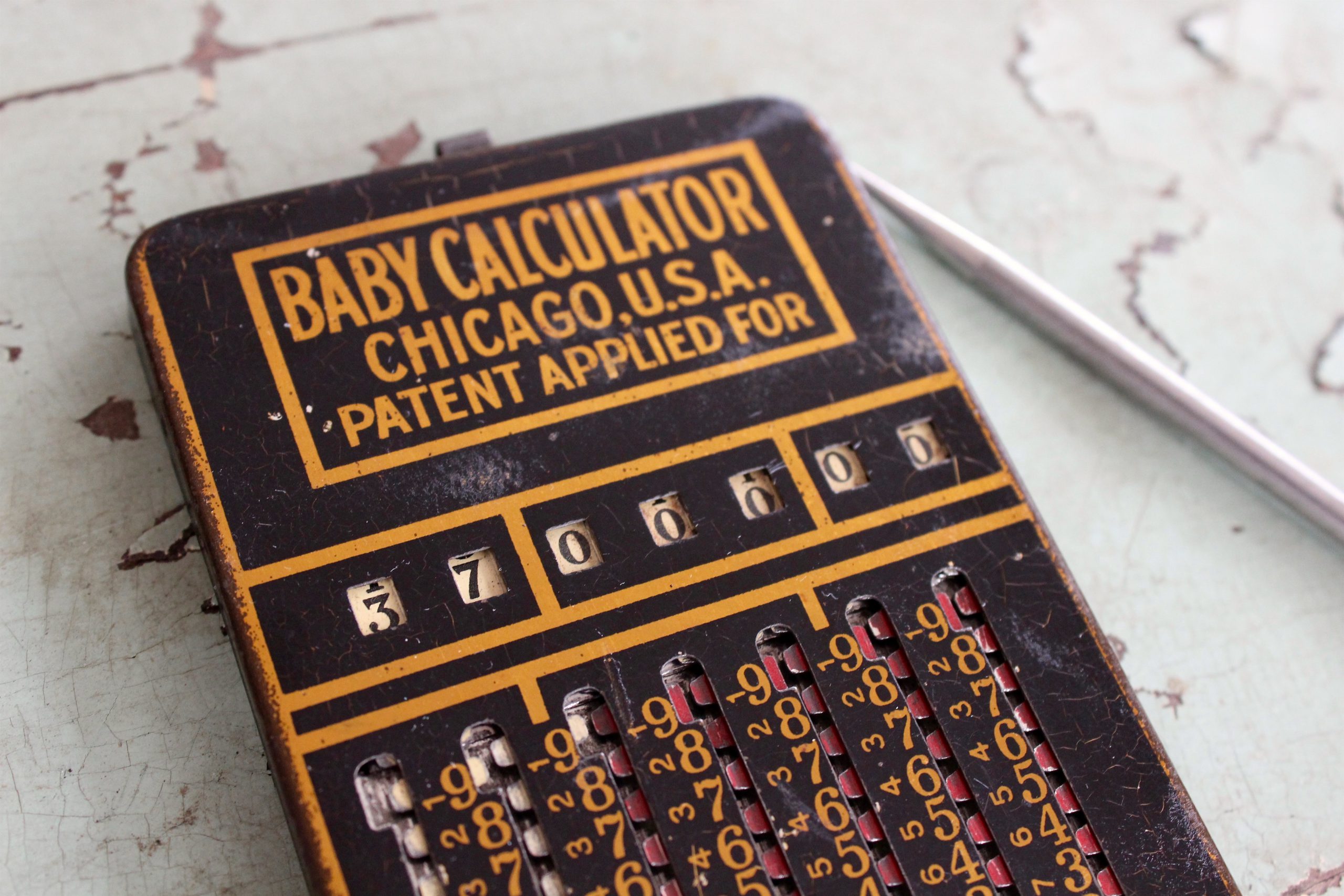

Museum Artifact: Baby Calculator, c. 1928

Made By: Baby Calculator Sales Co. / Calculator Machine Company, 123 W. Madison St., Chicago, IL [Downtown / The Loop]

“So simple in operation a child can use it. Every man and woman will find it a boon in business, at home, or anywhere that figures are used for any purpose. You need not be an expert accountant or scholar—let the Baby Calculator do the work—speedily and accurately.” –Baby Calculator advertisement, 1926

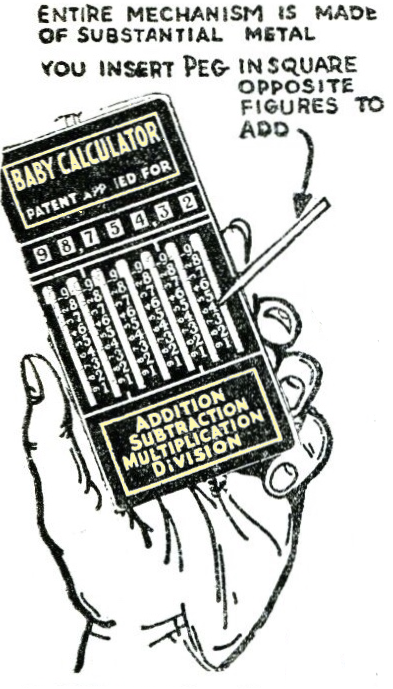

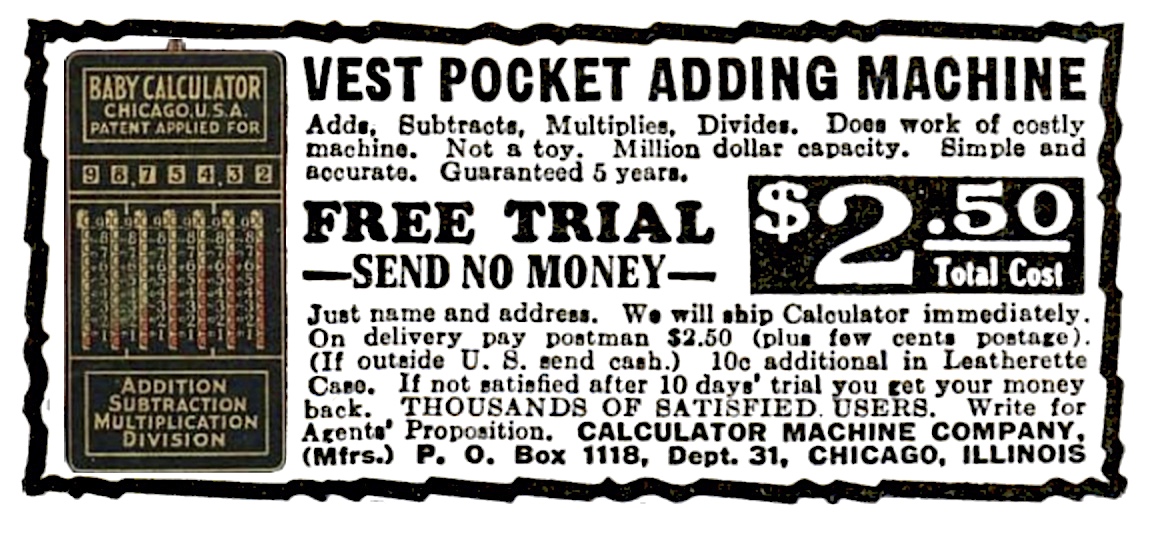

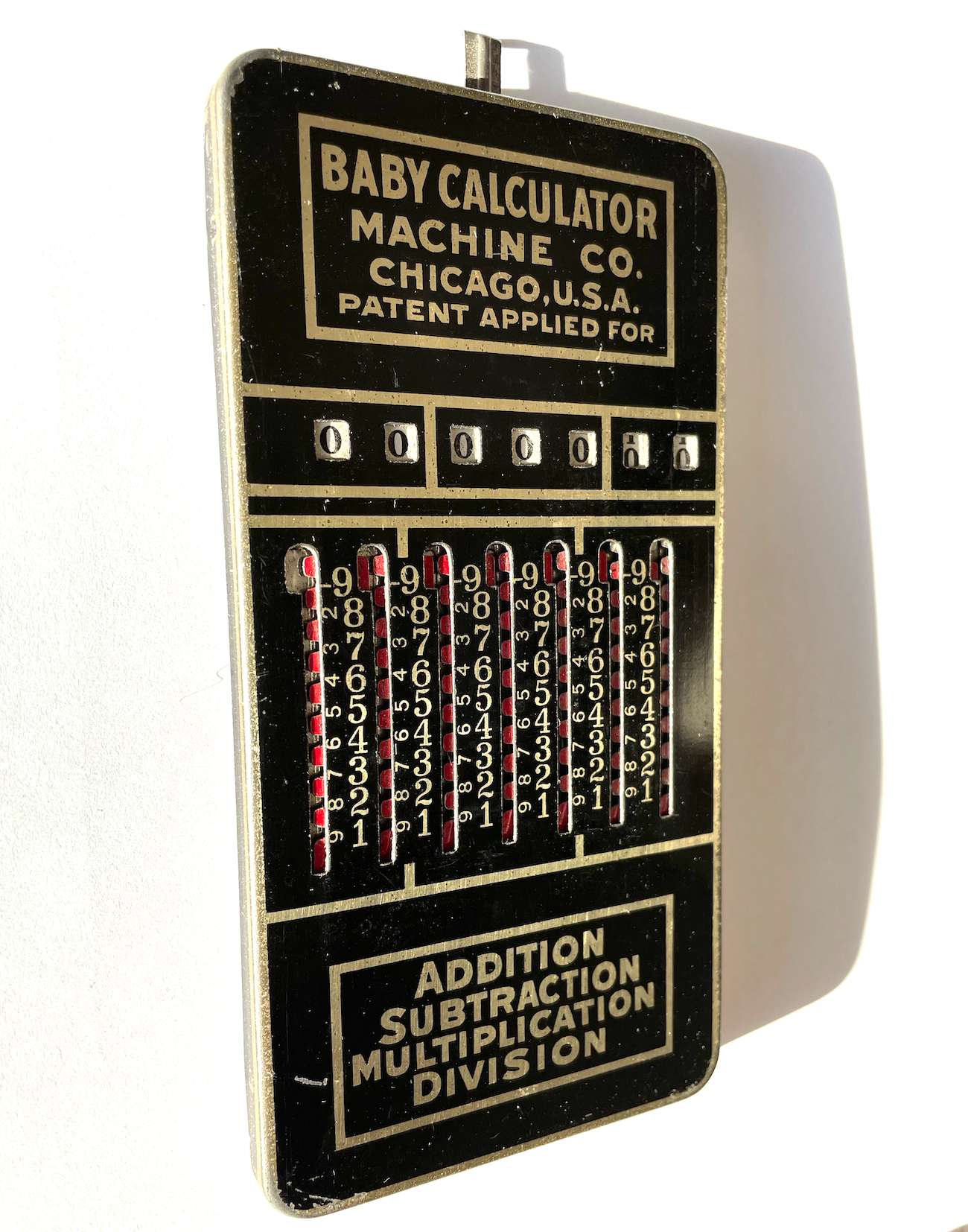

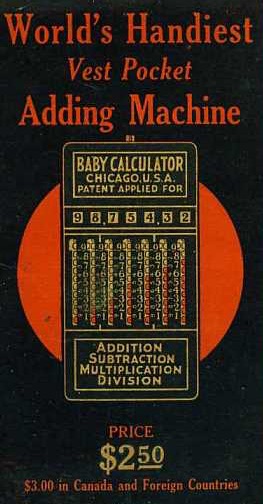

It has the same shape, size, and reflective black surface as a smartphone, but the “Baby Calculator” [named for its diminutive dimensions, mind you, rather than its ability to count infants] was invented 80 years earlier, and was thus quaintly disconnected from the outside world. Here was a pocket computer that didn’t need to be charged, backed up, or upgraded; nor did a single one ever get hacked. Instead, for the meager price of $2.50, it put all the wonders of basic mathematics in the palm of your hand. All you had to do was delicately and repeatedly jab a slippery stylus between a series of stubborn metal tabs situated inside seven, centimeter-wide columns, and. . . . BAM! Arithmetic for the Jazz Age!

It has the same shape, size, and reflective black surface as a smartphone, but the “Baby Calculator” [named for its diminutive dimensions, mind you, rather than its ability to count infants] was invented 80 years earlier, and was thus quaintly disconnected from the outside world. Here was a pocket computer that didn’t need to be charged, backed up, or upgraded; nor did a single one ever get hacked. Instead, for the meager price of $2.50, it put all the wonders of basic mathematics in the palm of your hand. All you had to do was delicately and repeatedly jab a slippery stylus between a series of stubborn metal tabs situated inside seven, centimeter-wide columns, and. . . . BAM! Arithmetic for the Jazz Age!

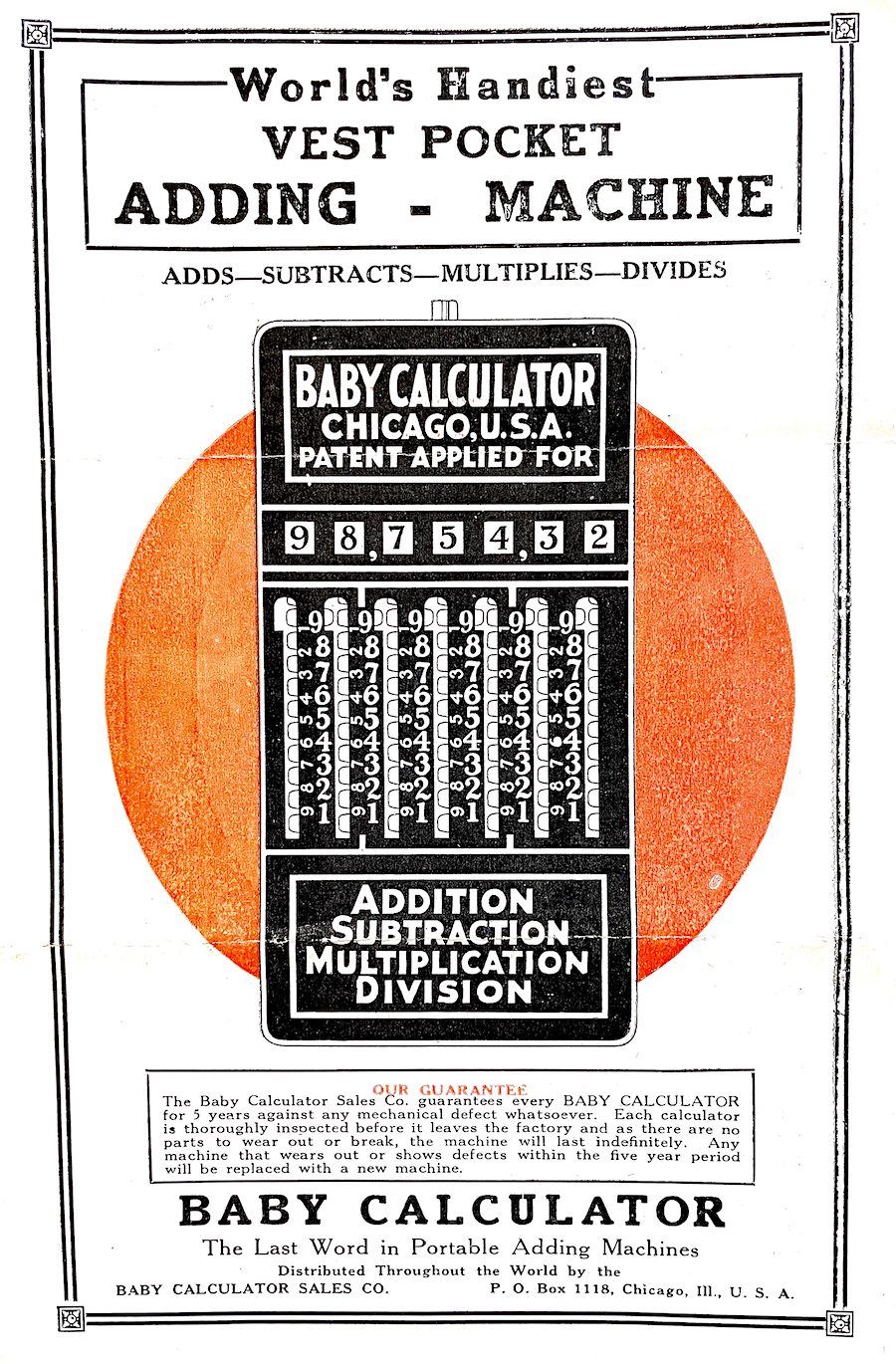

“A Speed Marvel!” claimed the advertisements. “The World’s Handiest Calculator!”

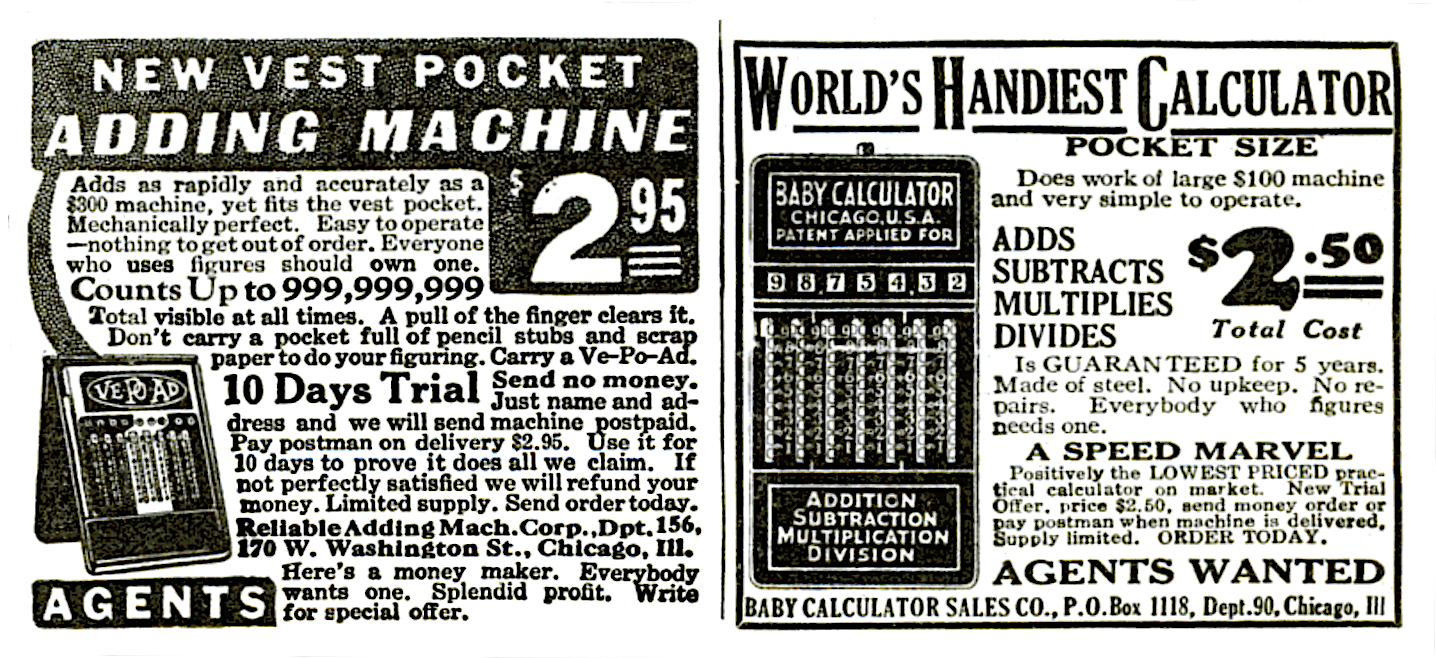

Keep in mind, when this Baby was born in the mid 1920s, the average person’s conception of a “calculator” was one of two things—either a flimsy classroom slide-rule or an enormous and decidedly non-portable office “adding machine” (such as the type built by the Victor Company or Felt & Tarrant). Shiny hand-held devices like the Baby Calculator and the similar Vest Pocket Adder (aka the “Ve-Po-Ad,” made by Chicago’s Reliable Typewriter & Adding Machine Corp.) were novelties that opened up a new frontier: Addition, Subtraction, Multiplication, AND Division—with no scratch paper required.

The novelty didn’t wear off as fast as you might have guessed, either. The Baby Calculator itself was still in production as late as the 1950s, before electronic upgrades finally killed it off for good. Despite that longevity and proliferation, though, the actual origins of this wee piece of tech remain a complete mystery. We have no inventor connected with it, no patent number (despite the “Patent Applied For” claim on the label) . . . not even a clearly identified factory location. Just about all we do have are the names of three very different Chicagoans who each took their turn selling the Baby Calculator to the world. One had been a leading theater critic with the city’s top African-American newspaper; another was a future Illinois state senator; and the third ultimately lost his life in a infamous plane crash on February 3, 1959 . . . “the day the music died.”

History of the Baby Calculator, Part I: Tony Langston’s Calculation

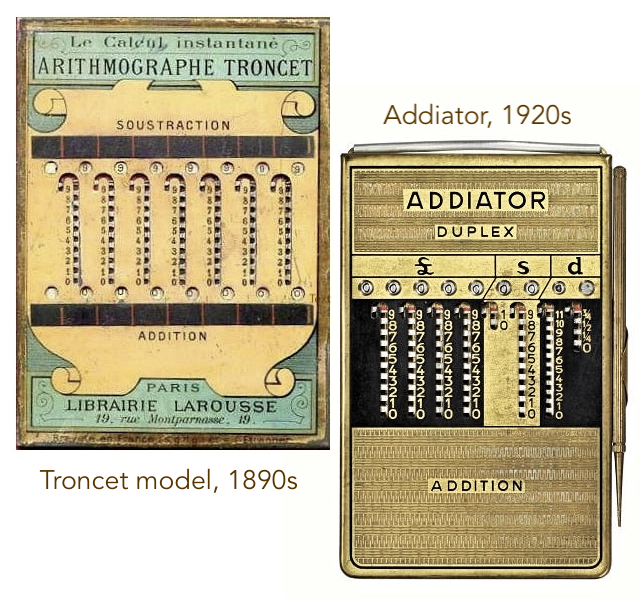

There’s probably a good reason why the Baby Calculator seemingly had no inventor, and why no patents were ever bestowed upon it. In truth, most of these new American slide adders of the ’20s and ’30s were little more than knockoffs of European models that had already been on the market for years. The French inventor Louis Troncet had developed a successful handheld slide adder as far back as the 1880s, and by 1920, a German device called the Addiator (invented by Carl Kubler) had improved upon it, even earning a US patent. Inevitably, similar machines were going to start popping up to meet growing demand, and the Baby Calculator was merely one of them, appearing around 1923.

The first mention we could find was from an advertisement in the July 23, 1923 edition of the Chicago Tribune. “Seeking salesmen in every state of the union for selling a popular adding machine,” it reads. “Can do the four operations; small price; big profit; the machine is for all the people; something new. Write to the BABY CALCULATOR CO., 600 Blue Island Av., Room 306. Chicago.”

The first mention we could find was from an advertisement in the July 23, 1923 edition of the Chicago Tribune. “Seeking salesmen in every state of the union for selling a popular adding machine,” it reads. “Can do the four operations; small price; big profit; the machine is for all the people; something new. Write to the BABY CALCULATOR CO., 600 Blue Island Av., Room 306. Chicago.”

By the following year, ads now placed the office at 123 W. Madison Street, and potential sales agents were promised they could earn $200 per week selling the new adder for $2 a pop (which is equivalent to about $33 in 2022). Come 1925, the office had migrated again to 130 S. Oak Park Avenue in Oak Park, and the company was re-named the Baby Calculator MACHINE Co., with the device’s price now raised to $2.50. That would be the last time for a long while that the business would be affiliated with an actual street address. For years to come, customers were usually provided only with a Chicago P.O. box. Any sort of professional office, let alone a production plant, was left to the imagination. It’s a safe assumption that the manufacturing of the early Babies was outsourced to other businesses rather than handled in house; but we can’t be sure who they were or whether they were located in Chicago.

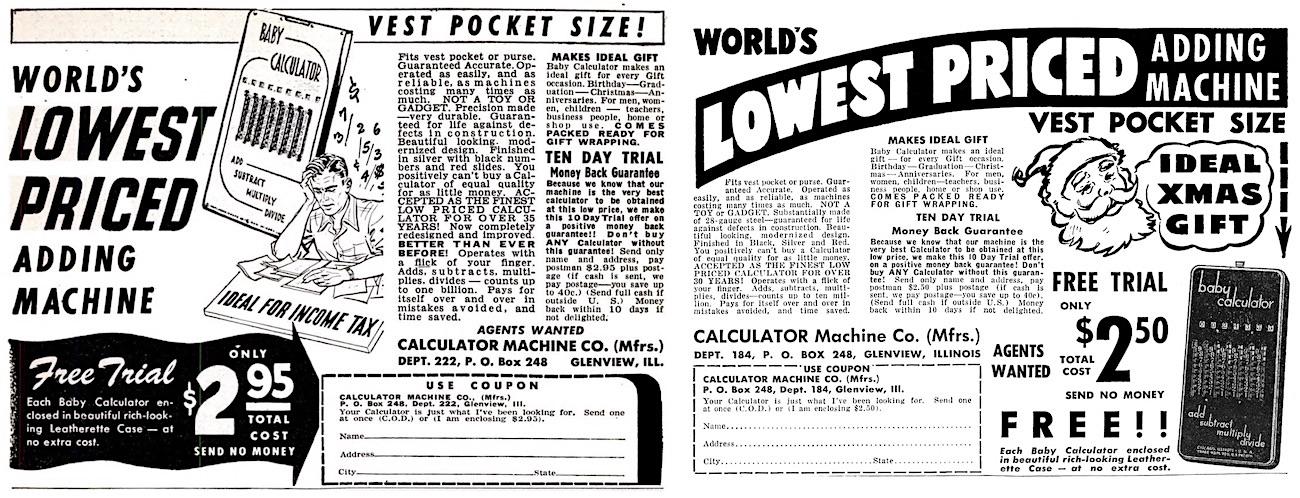

[Baby Calculator advertisement (right) appearing right beside an ad for its slightly pricier rival, the Vest Pocket Adder, aka Ve-Po-Ad, in a 1928 magazine]

By 1926, though, there is no doubt that Chicago was still the hub of the Baby Calculator sales effort, and the new National Distributor on the project was a local fellow by the name of Tony Langston. This is quite significant for the time period, because Langston wasn’t your run-of-the-mill gadget peddler, nor did he have the usual skin color of a national sales executive. Instead, the 50 year-old Detroit native was already well known as one of the leading African-American theater critics in the country; serving as the entertainment editor for the Chicago Defender and later the Chicago Bee. He also had ownership shares in several theaters and ran his own agency, the Langston Slide and Advertising Co., in Chicago’s thriving black neighborhood of Bronzeville.

“Tony Langston is without question the most popular Colored theatrical writer not only in America but throughout the world . . . [and the] highest paid writer in the history of Colored journalism,” the black culture writer William Henry Harrison, Jr., wrote in 1921. “Never very far from nor out of sight of ‘Dear Old State Street,’ he writes the widest variety of subjects of any present-day penman in that line and is read by more than one million each and every week.”

Covering the early days of Chicago jazz and blues, as well as movies, Langston was a tastemaker who criticized tired racist stereotypes and tipped his readers off to a new wave of emerging black talent.

Covering the early days of Chicago jazz and blues, as well as movies, Langston was a tastemaker who criticized tired racist stereotypes and tipped his readers off to a new wave of emerging black talent.

“Bessie Smith, Empress of Blues Singers,’ opened her first Chicago engagement at the Avenue on Monday night to a capacity audience,” he wrote in the Defender in 1924. “So much has been said of Bessie that Chicagoans were looking for something far above the average in her line, and that’s just what the famous artist handed them. Her routine of songs are new and well selected and she put each and every one of them over with the well-known ‘Bang.'”

So how did Tony Langston go from rubbing shoulders with legends to selling Baby Calculators?

Well, in 1925, Langston and several other Defender scribes had a rather nasty falling out with the newspaper’s founder and publisher Robert S. Abbott, who accused them all of embezzlement. Tony was dismissed, and responded by bitterly filing his own lawsuit against Abbott for unpaid commissions. In the end, Langston took a much lower profile gig with an upstart paper called the Chicago Bee, and by 1926, he announced he was leaving that role to focus on his new job as the sales head for the Baby Calculator. Who hired him? That we may never know. But at least for a while, the new gig seemed to be going okay.

“Tony Langston, the general distributor of the Baby Calculator Machine, states in a letter that over 70,000 have been sold within the past year,” the Pittsburgh Courier reported in May of 1926, “not only to business people, but to students, housewives and all who form the great class who come in contact with situations through which accurate figuring must be done. In fact, Langston declares that one of these calculators should be owned by every individual who is ever required to use a lead pencil.”

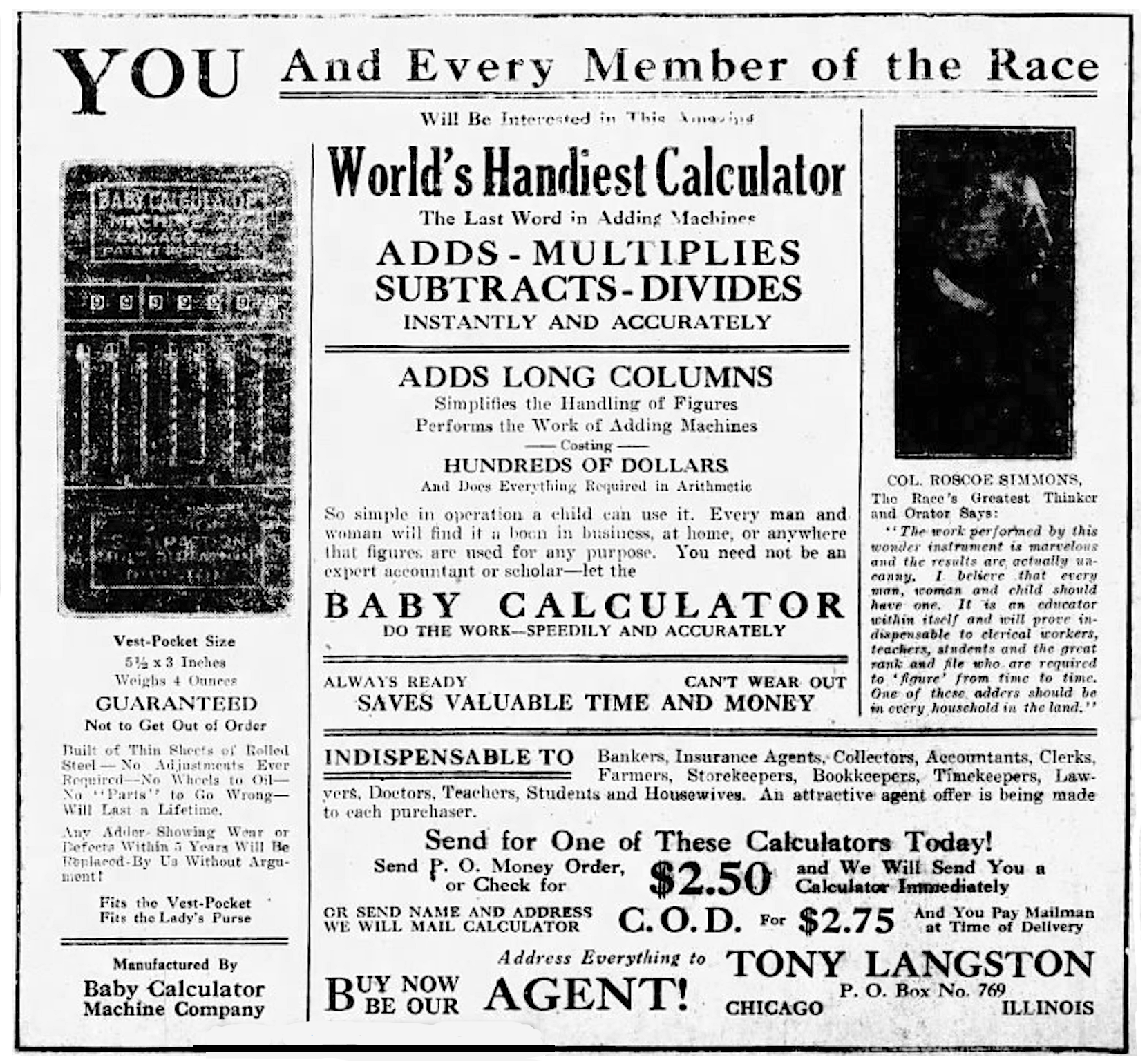

[Advertisement in the Pittsburgh Courier, a black newspaper, from 1926. “Address everything to Tony Langston”]

Langston put his best foot forward as a calculator salesman. He even recruited the respected black orator and activist Roscoe Simmons (nephew of Booker T. Washington) to promote the machine in various ads printed in black newspapers. “The work performed by this wonder instrument is marvelous and the results actually uncanny,” Simmons proclaims in one of them. The targeted campaign soon stumbled, though, as mainstream white newspapers either weren’t approached or, more likely, refused to do business with Langston. By 1928, Langston’s connection with the product seems to end entirely, and his career doesn’t appear to have picked up afterward. Upon his death from heart disease in 1936, aged 61, his death certificate listed his occupation as “laborer.” A nice obituary was printed in the Detroit Tribune, a black newspaper in Langston’s hometown, but as ever, his life and death were largely ignored by the white media.

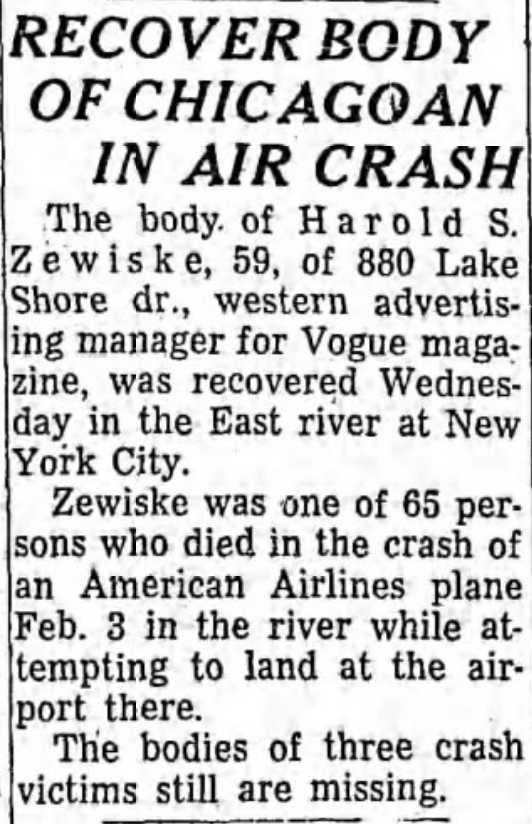

Part II. Harold Zewiske’s Tragic Synchronicity

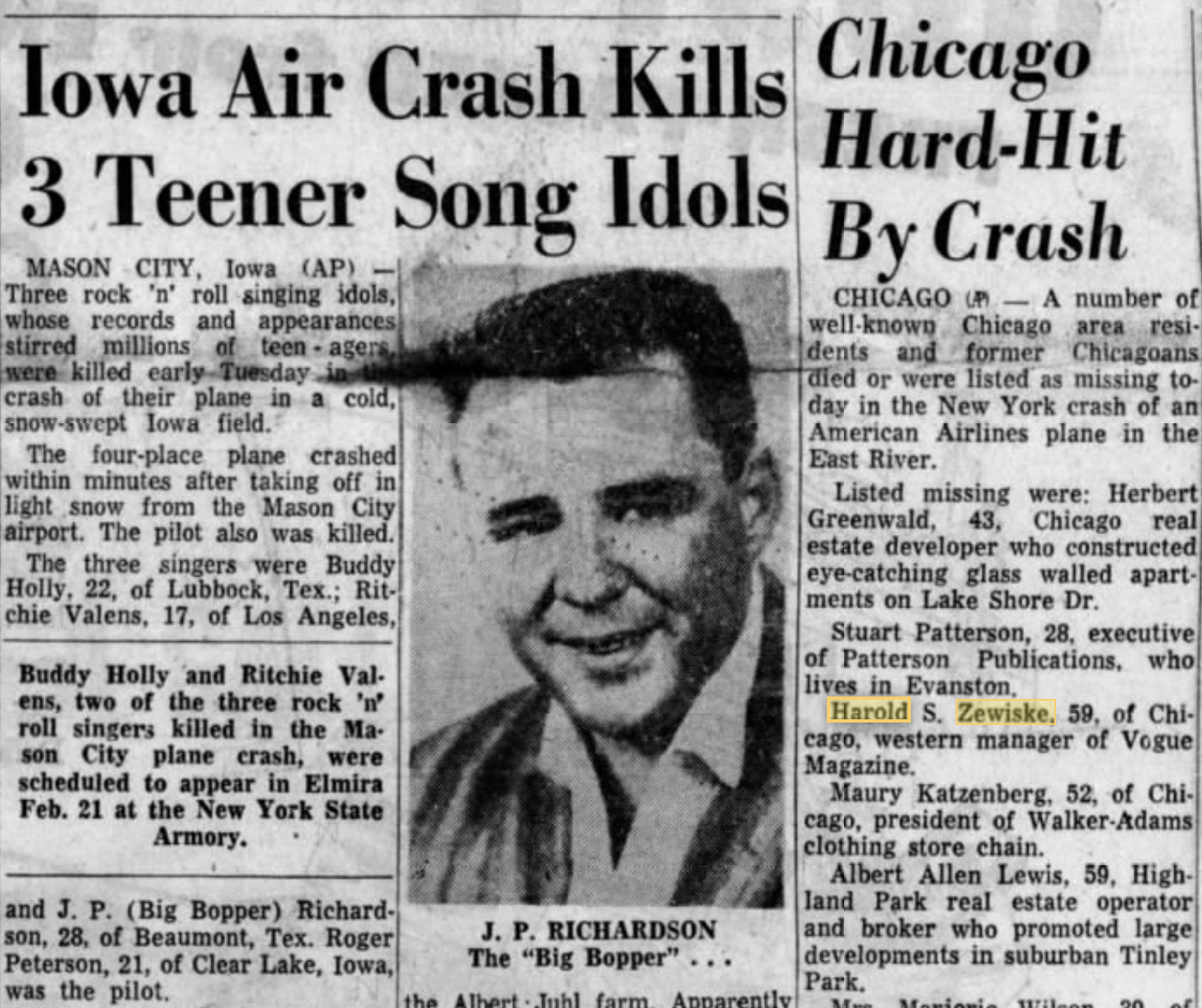

Just about everybody knows about “The Day the Music Died”—the Iowa plane crash on February 3, 1959, that killed rock n’ roll legends Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and the Big Bopper. But did you know there was a much deadlier airline crash in the U.S. on the exact same night?

If your response is: “No, I didn’t know that, but I thought we were talking about Baby Calculators?” Worry not. I promise the story comes together. . .

After Tony Langston moved on from the Baby Calculator Machine Co. around 1927, the product’s promotional campaign came to a grinding halt. Then, after some series of forgotten conversations and negotiations, a second push commenced. The Baby Calculator was reborn.

After Tony Langston moved on from the Baby Calculator Machine Co. around 1927, the product’s promotional campaign came to a grinding halt. Then, after some series of forgotten conversations and negotiations, a second push commenced. The Baby Calculator was reborn.

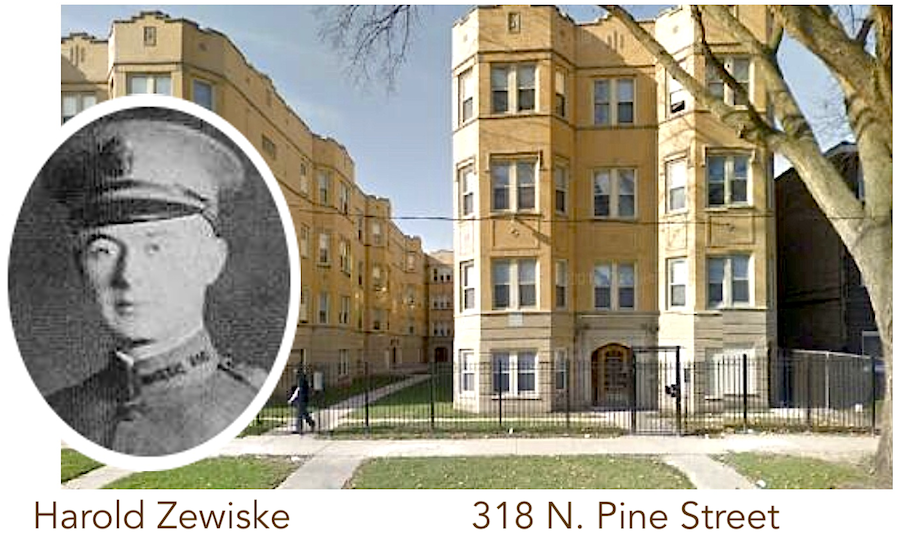

On May 8, 1928, a 29 year-old Chicago salesman named Harold S. Zewiske applied to register the “Baby Calculator” brand name as a trademark with the U.S. Patent Office, one of the few official records that still exists related to the business.

“Harold S. Zewiske,” it states, “a citizen of the United States of America, residing in Chicago, Illinois, and doing business as the Baby Calculator Sales Company, at 318 North Pine Street, Chicago, Illinois, has adopted and used the trade-mark shown in the accompanying drawing, for CALCULATORS, in Class 26, measuring and scientific appliances, and presents herewith five specimens showing the trade-mark as actually used by applicant upon the goods, and requests that the same be registered in the United States Patent Office. . . The trade-mark has been continuously used and applied to said goods in applicant’s business since June 1st, 1924. The trade-mark is applied by stamping or printing the same upon the goods.”

Zewiske, who was white, was born in Morrison, Illinois, in 1899. He served in the military toward the end of World War I, then attended Dubuque College and the Aurora Business College before entering the advertising racket, selling space for publications like the Dry Goods Reporter and American Magazine in the 1920s. Based on the trademark submission above, it sounds as if Zewiske might have been involved with the Baby Calculator as early as 1924—perhaps discovering the device when someone pitched an early advertisement to him. But it’s also possible that he just took on the account later on, much as Langston had—as a lark, or a shot in the dark.

The company address mentioned in the trademark document, 318 N. Pine Street, isn’t a factory or an office building—it was actually Zewiske’s apartment in the South Austin neighborhood of Chicago, where he lived with his widowed mother and his sister.

From 1928 into the 1930s, presumably under Zewiske’s guidance, Baby Calculator promotions suddenly returned to mainstream publications, including monthly issues of Popular Mechanics, in particular.

“Does the work of a $300 machine,” a 1929 ad claimed, juxtaposed with the $2.50 price tag. “Guaranteed 5 years. NOT A TOY. Made of steel and indestructible. Will not make mistakes. So simple a child can operate it. Everybody should carry one for figuring.”

How successful was this latest campaign? Well, successful enough that the Baby Calculator managed to survive the stock market crash and the onset of the Great Depression. Perhaps not successful enough, however, to become Harold Zewiske’s meal ticket.

In 1934, Zewiske took a job with the Chicago office of the major publishing company Conde Nast. That same year, the business behind the Baby Calculator changed its name to the Calculator Machine Company, perhaps suggesting some attempt to diversify its product line. A 1934 ad in Popular Mechanics also lists the Calculator Machine Co. as “manufacturers” of the Baby Calculator, though its address is still listed only as P.O. Box 1118, Dept 31, Chicago, Illinois.

Ten years into the tale, and we still have no real sense of the scope of this business or just how many other people were involved. Since the design and appearance of the Baby Calculator never changes over this period, it’s quite possible that Langston, Zewiske, and others salesmen were still trying to unload overstock from one big production run back in the early 1920s.

Ten years into the tale, and we still have no real sense of the scope of this business or just how many other people were involved. Since the design and appearance of the Baby Calculator never changes over this period, it’s quite possible that Langston, Zewiske, and others salesmen were still trying to unload overstock from one big production run back in the early 1920s.

In any case, by 1940, Harold Zewiske was 40 years old, working as an advertising solicitor, and still living in an apartment with his mom and sister, this time on Mayfield Road. Zewiske never married, but he was hardly a sad sack despite how the circumstances sound.

In fact, his career experienced a considerable upswing after World War II. Through his role with Conde Nast, he’d become the western advertising manager for Vogue magazine, and soon upgraded to a fancy new high-rise apartment at 880 N. Lake Shore Drive. Then, on February 3, 1959, Harold Zewiske said farewell to his 88 year-old mother and boarded a flight at Midway Airport bound for New York’s Laguardia—likely for the purpose of attending a meeting at the Vogue offices.

He never got there.

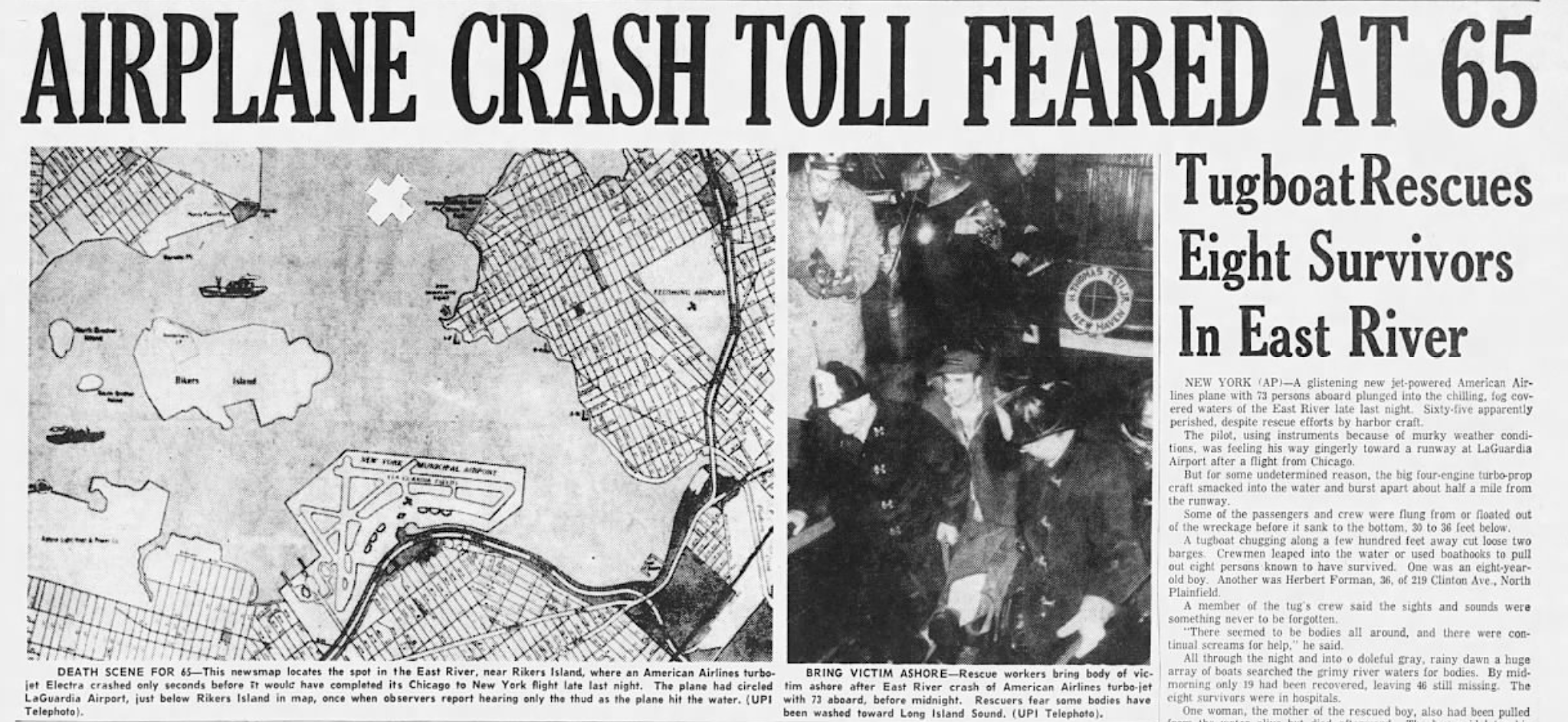

“A glistening new jet-powered American Airlines plane with 73 persons aboard plunged into the chilling, fog covered waters of the East River with a shattering crash late last night,” the Associated Press reported the next morning. “Sixty-five apparently perished, despite feverish rescue efforts by harbor craft.

“The plane’s pilot, using instruments because of the murky weather conditions, was feeling his way gingerly toward a runway at LaGuardia Airport after a flight from Chicago.

“But for some undetermined reason, the big four-engine turbo-prop craft smacked into the water and burst apart about half a mile from the shore end of the runway. Some of the passengers and crew were flung from or floated out of the wreckage before it sank to the river bottom 30 to 36 feet below.”

The crash of American Airlines Flight 320 happened at virtually the same moment that Buddy Holly and his friends had met their doom over Clear Lake, Iowa. As far as we know, though, no popular songs were ever written to commemorate this event.

To heap tragedy upon tragedy, Harold Zewiske’s body was not quickly recovered from the wreckage in New York, leaving his elderly mother and other friends and relatives to wait for final word of his fate. His remains weren’t found until four months later, on June 10, 1959.

No mention was made in Harold’s subsequent obituaries as to his contributions to a humble little calculator business.

[Newsreel footage from the aftermath of the American Airlines 320 crash in 1959]

Part III. Lighter Than Arrington

The final character in the Baby Calculator’s strange, Red Violin-esque journey through time is William Russell Arrington. Best known as a Republican state senator in the Illinois General Assembly, where he served from 1945 to 1973, Arrington was also a self-made man and an entrepreneur. Born in Gillespie, Illinois, in 1909, he spent time as a junior clerk in the Union Stockyards before working his way through law school at the University of Illinois. By 1940, aged 31, he was a partner in his own Chicago law firm and an executive with a couple small manufacturing businesses. Arrington’s office on the ninth floor of the Field Building at 135 S. LaSalle would soon become the next unlikely headquarters of the Baby Calculator Co.

Arrington had been looking for a small enterprise to acquire as a sort of gift to his working class father, and when he spotted one of those familiar ads for the Baby Calculator in a magazine, he made the rather bold decision to try and track down the owner of the business and make him an offer. It might have been Zewiske at this point, or someone else. But Arrington was in luck; the owner was willing to sell the entire business for just $4,000 (which translates to about $80,000 in 2022).

Arrington had been looking for a small enterprise to acquire as a sort of gift to his working class father, and when he spotted one of those familiar ads for the Baby Calculator in a magazine, he made the rather bold decision to try and track down the owner of the business and make him an offer. It might have been Zewiske at this point, or someone else. But Arrington was in luck; the owner was willing to sell the entire business for just $4,000 (which translates to about $80,000 in 2022).

Sadly, Arrington’s father died shortly after the deal was completed in 1940, but William stuck with it anyway, for “emotional” reasons, according to his biography.

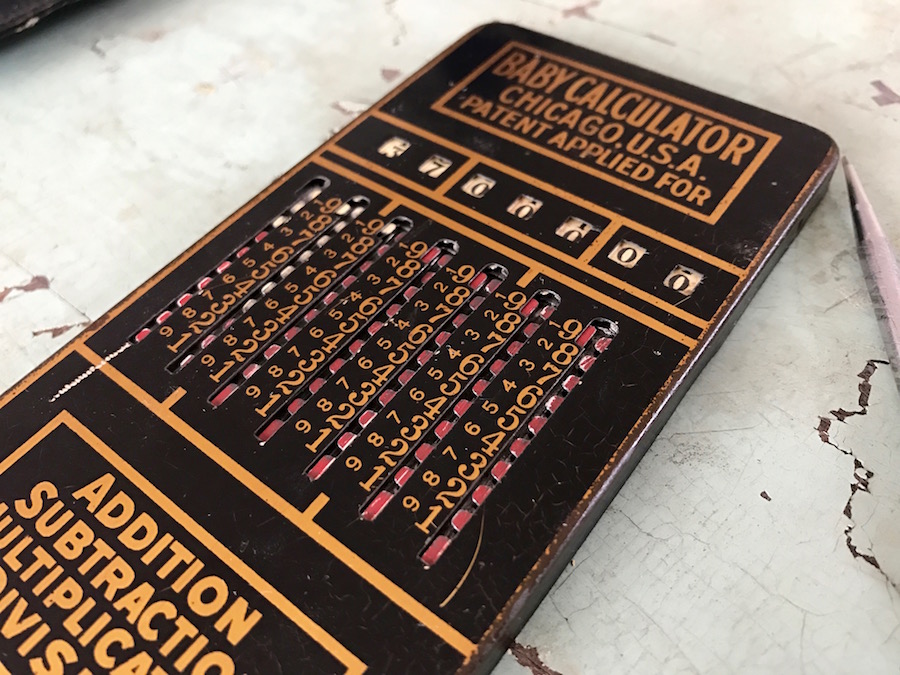

By Arrington’s recollection, the Baby Calculator “very simply consisted of a dish, a stylus, and a tin condenser. I had a manufacturer who would give me the tin and shape the machine. I had another manufacturer make the stylus, and another who would put on some device that used the stylus to figure. Then, I also had a manufacturer who made a leatherette case. And that was it.”

All these various components were assembled at a machine shop and then sent to W. R. Arrington’s law office, where Arrington himself, along with his assistant Marion Belland, spent evenings packing the calculators in their cases and mailing out orders.

“Arrington did not conceal his astonishment at the success of the venture,” author Taylor Pensoneau writes in his 2006 book, Powerhouse: Arrington from Illinois. “All in all, an annual average net of $6,000 was realized during the four years he operated the business; not bad for one of his sidelines to his law practice. When he sold the business in 1944 for $10,000, he allowed himself to sit back for a moment and reflect that he’d netted $34,000 overall from Baby Calculator. His many irons in the fire–including increased political involvement–had necessitated the sale of Baby Calculator. Still, he could not help but lament the giving up, in his words, of a ‘gold mine.'”

[Evolution of the Baby Calculator design from the 1920s to the 1950s. Despite the claim on each of these manuals, we’ve yet to find a registered patent for the Baby Calculator]

W. R. Arrington traded in his calculator business to run for state office, where he’d stay for 30 years. Though never a household name or a figure on the national stage, he had a very big impact behind the scenes of Illinois politics, and was described by the Illinois Times, long after his death, as “one of history’s most dominant legislators, with ideas that influenced state government, especially the Senate, for decades.” He died in 1979.

After it was sold in 1944, the Calculator Machine Company relocated to suburban Glenview, Illinois, under new (unknown) ownership. A few more style changes came about during these years, including the addition of plastic into the construction. Competition from electronic calculators was on the horizon, too, but through it all, the Baby Calculator was still routinely advertised in Popular Mechanics as late as 1956, now priced at $2.95. For a brief period after this, the sales office appears to have finally left Illinois altogether, with some of the last Baby Calculators distributed out of Huntingdon Valley, Pennsylvania. The trail runs cold by 1960.

[Post-war ads for the Baby Calculator after its sale and move to Glenview, IL]

Part IV. How to Use the Baby Calculator

For over 30 years, one of the Baby Calculator’s big selling points was always its supposed ease of use. As late as 1950, when the stylus had been replaced with a “flick of the finger,” a magazine ad touted that the calculator was “operated as easily, and as reliably, as machines costing many times as much.”

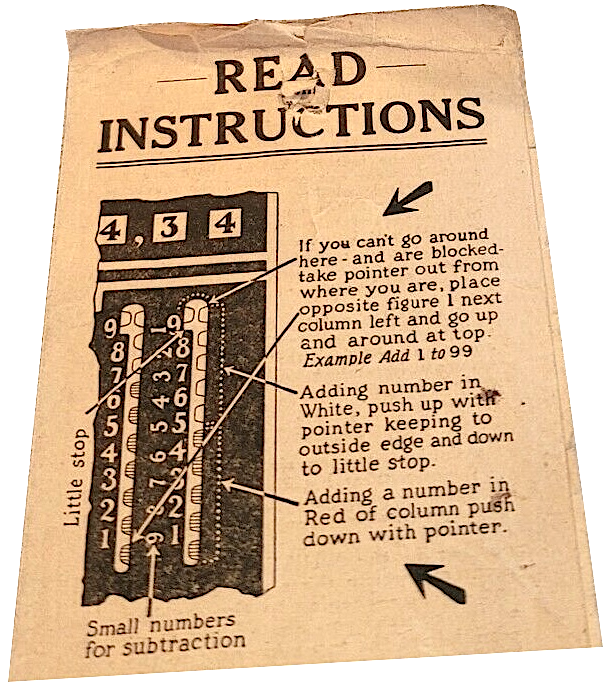

Was that ever actually true? Well, looking at the original Baby Calculator with a pair of 21st century eyes, simplicity isn’t the first word that comes to mind. In fact, I’d wager that I could split a dinner bill six ways—using inebriated mental math—in less time than it would take me to figure how to work the slides on this 90 year-old machine. But let’s not be too hasty . . . I’m sure that a close examination of the Baby Calculator’s step-by-step instruction manual will set us all straight as to how simple it really was to use a state-of-the-art piece of tech during the Hoover administration.

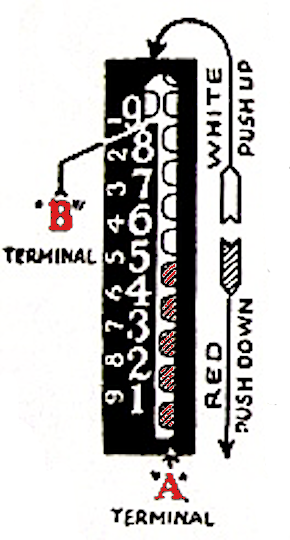

“Addition is very simple. . . . When you ADD a number, place pointer in hole to the right of number to be added and if pointer is in ‘RED’ of column move towards the bottom terminal ‘A’ as shown per illustration at left. When you place pointer in hole to right of figure to be added and column is ‘WHITE’– move pointer upwards and direct it around the bend, keeping to outside edge at the head of figure column to a stop at terminal ‘B’ as indicated in illustration at left.

“Addition is very simple. . . . When you ADD a number, place pointer in hole to the right of number to be added and if pointer is in ‘RED’ of column move towards the bottom terminal ‘A’ as shown per illustration at left. When you place pointer in hole to right of figure to be added and column is ‘WHITE’– move pointer upwards and direct it around the bend, keeping to outside edge at the head of figure column to a stop at terminal ‘B’ as indicated in illustration at left.

“IMPORTANT– Remember that in each operation ADDING, the pointer must go all the way down to terminal ‘A’ when numbers to be added is opposite RED of column and all the way up and over to the left and down to a stop at terminal ‘B’ when adding figure opposite WHITE of column.”

There now, was any of that confusing? I certainly hope not, because that was merely a brief guide to using the Baby Calculator for addition only, which the designers admit up front is the primary intended function of the device. If you’ve got a minus sign on the brain, or, god forbid, some serious long division, you may soon get carpal tunnel trying to manipulate that stylus into the necessary notches.

Maybe I’m just being unfair. It’s easy to be dismissive or condescending toward obsolete tools when we’re sitting in our silicon towers. But apparently, even way back in 1949, people had their criticisms.

Maybe I’m just being unfair. It’s easy to be dismissive or condescending toward obsolete tools when we’re sitting in our silicon towers. But apparently, even way back in 1949, people had their criticisms.

The October issue of the Consumer Research Bulletin deemed that year’s model of the Baby Calculator “NOT RECOMMENDED,” and noted that because “the slide are not geared together; the operator must in some cases ‘carry one’ by a special mental and manual operation. . . . The machine has 7 columns, but the columns are not directly below the openings in which the totals appear, an inconvenient feature. It is difficult to see how this device would make addition or subtraction easier than (or as easy as) performing the same operations by hand.”

Perhaps some machines are obsolete for a reason. But then again, maybe the real legacy of the Baby Calculator is more evident in its looks than its usefulness. A thin, black, rectangular metal computer, stored in the pocket and held in the hand, gave mankind a glimpse of its future. The Baby grew up to become a monster.

[A young Harold Zewiske with his mother and sister, circa 1910]

Archived Reader Comments:

“Thank you for this very informative article. I just purchased the Baby Calculator (instructions, stylus, case and all) at a rummage sale thinking maybe it was from the 40’s. I wanted a little more information on it. I had no idea it was as old as it is with such an interesting history! ” —Nikkie, 2019

“When I was a child I bought a cheap version of this in a toy shop for pocket money prices. It worked perfectly, easy to use and was surprisingly robust. Genuinely useful before electronic calculators were the norm. For adding and subtracting it was almost as fast as an electronic one.” – Andrew Scales, 2018

Sources:

Colored Girls and Boys Inspiring United States History, by William Henry Harrison, Jr., 1921

“Salesmen” (advertisement) – Chicago Tribune, July 23, 1923

“Adding Machine is a Real Wonder” – Pittsburgh Courier, May 1, 1926

“Writer Resigns” – Pittsburgh Courier, May 8, 1926

“Airplane Crash Toll Feared at 65” – Central New Jersey Home News, Feb 4, 1959

“Ad. Publishing World Hit Hard in N.Y. Plane Crash” – Advertising Age, Feb 9, 1959

Bessie, by Chris Albertson, 1972

Powerhouse: Arrington from Illinois, by Taylor Pensoneau, 2006

“The Giant Who Changed Illinois Politics” – Illinois Times, March 28, 2007

Slide Rule Museum: Adders

John Wolff’s Web Museum: Slide Adders

“Baby Calculator” – American Stationer

HELLO. I have a version #2 Baby Calculator made 1945-1947 apparently. It’s looks almost unused, no marks. It’s all here, calculator, pointer, case, and instructions. I’m wanting to sell it. Need to if anybody reading this is interested in it or knows any locations that purchase Baby Calculators. Also need to know what a fair market value would be. THANKS, Woody

I have a Baby Calculator-made in Huntingdo, PA. It had original case, instructions and original outer box. Any idea as to it’s worth today?

I’m a slide adder collector and I have purchased several Huntingdon Babys over the years. Most have been in the $10 to $20 range plus shipping. However, what really can drive the price up is not the calculator but the ephemerals (such as your box). Especially, if shows some unique information, like price or date info. But bear in mind, that the only real determiner of price is strictly what someone else is willing to pay.

http://www.rechnerlexikon.de/en/artikel/Baby_Calculator_(Chicago)

The instructions can be found at the link above. There are two jpegs, front and back.

The site is an incredible database of info on all kinds of mechanical calculators/ adding machines.

I am looking for instructions also. Where can I find it?

I spent hours and hours in my grandfather’s basement In the late 1950s early 60s while he assembled The Tom Thumb and another style calculator. Is this the same company as the Baby Calculator? My grandfather was Frank E. Day and he was from Chicago and then moved to the suburbs of Philadelphia.

Hi,

The ads for the Baby Calculator indicate that they were made in Glenview starting in December 1948 until mid 1956. The transition from all metal to plastic and metal occurred in late 1947. In May of 1957 the Baby indicates it was made in Huntington Valley, PA. The first ad for the Tom Thumb version appears in Feb 1959. The Tom Thumb is mechanically identical to the Baby. The Tom Thumb calculators do not have any indication about where it was made but the ads reference a P.O. Box in Bethayres,

PA. , which is right next to Huntington Valley.

So, given all of that, I think the answer to your question is Yes- It is the same company. Ok would love to learn more about what happened back then. I’m intrigued about your Grandfather working out of his basement. Did he have the equipment for making the plastic or did he just assemble the final product? Did he work alone or was he part of a larger group? The last ad for the Tom Thumb occurred in early 1963, what brought production to an end?

Oops. That should be ‘Huntingdon’ not ‘Huntington’.

I have a baby calculator machine. Am looking for operating instructions. If anyone has these please notify me and if possible email a copy of them.

Thank you