Museum Artifacts: Bell & Howell 8mm Magazine Movie Camera 172 (c. 1950), Filmo Auto Load 16mm Movie Camera (1940s), Filmosound 179 16mm Film Projector (1940s), Filmo Projector 57 Model GG (c. 1930s)

Made By: Bell & Howell Co., 1801 W. Larchmont Ave., Chicago, IL [North Center]

“When you buy a roll of film, it is worth just what you pay for it, and no more. But, once it has gone through your camera, it has become a priceless living record of the hours, days, and years you want most to remember. When you give that film to your camera, it should be with confidence that the best possible job will be done with those days, hours, and years. We believe that if a picture is worth the film, it is worth a B&H camera.”

—Bell & Howell brochure, 1940s

Considering that the Bell & Howell name lives on today as little more than a zombified trademark slapped onto various infomercial gadgets, it’s easy to forget just how significant the original Chicago-based company was not only in the development of quality home movie equipment (like the handheld cameras and Filmosound projector in our collection), but in the foundation of the motion picture industry itself.

Considering that the Bell & Howell name lives on today as little more than a zombified trademark slapped onto various infomercial gadgets, it’s easy to forget just how significant the original Chicago-based company was not only in the development of quality home movie equipment (like the handheld cameras and Filmosound projector in our collection), but in the foundation of the motion picture industry itself.

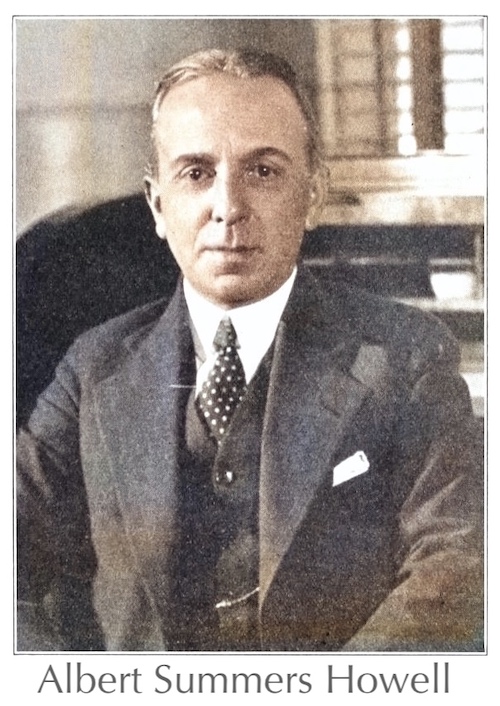

“We talk of the birth of the airplane at Kittyhawk, the birth of the steamboat up the Hudson, of the telephone and the radio down in New Jersey,” a 1932 article in Filmo Topics recounts. “But the movies were born in little villages and big villages in every corner of America, where the rapt fascination of the populace inspired a mechanical genius in Chicago to help give the people more of what they wanted, and to improve the movies immeasurably in the process. This genius was Albert S. Howell.”

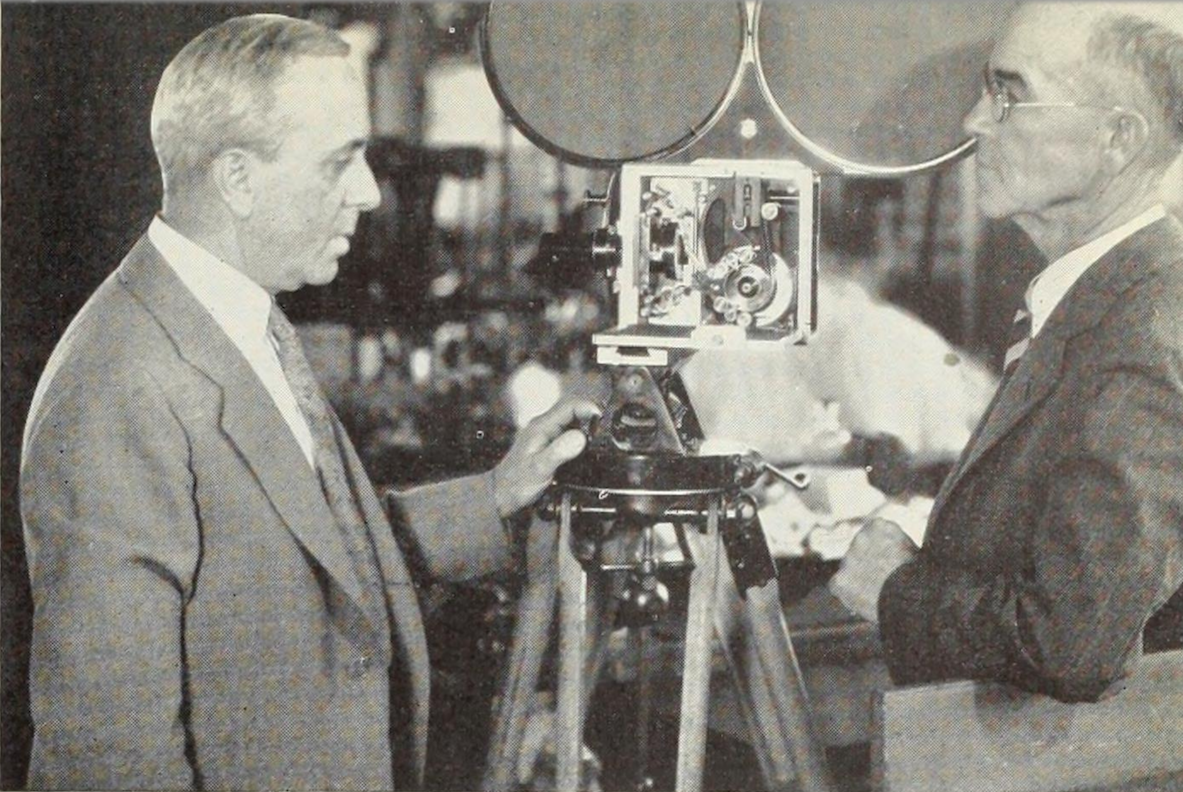

Yup, it’s probably worth establishing right out of the gate that—despite the order of their names on the company banner—the wunderkind Albert Summers “Bert” Howell plays a much larger role in this story than Donald J. Bell, who left the firm under somewhat acrimonious circumstances just 10 years into its existence. It is no exaggeration, however, to say that there’d have been no Howell without Bell. It was the latter who directed the former on his proverbial path to glory.

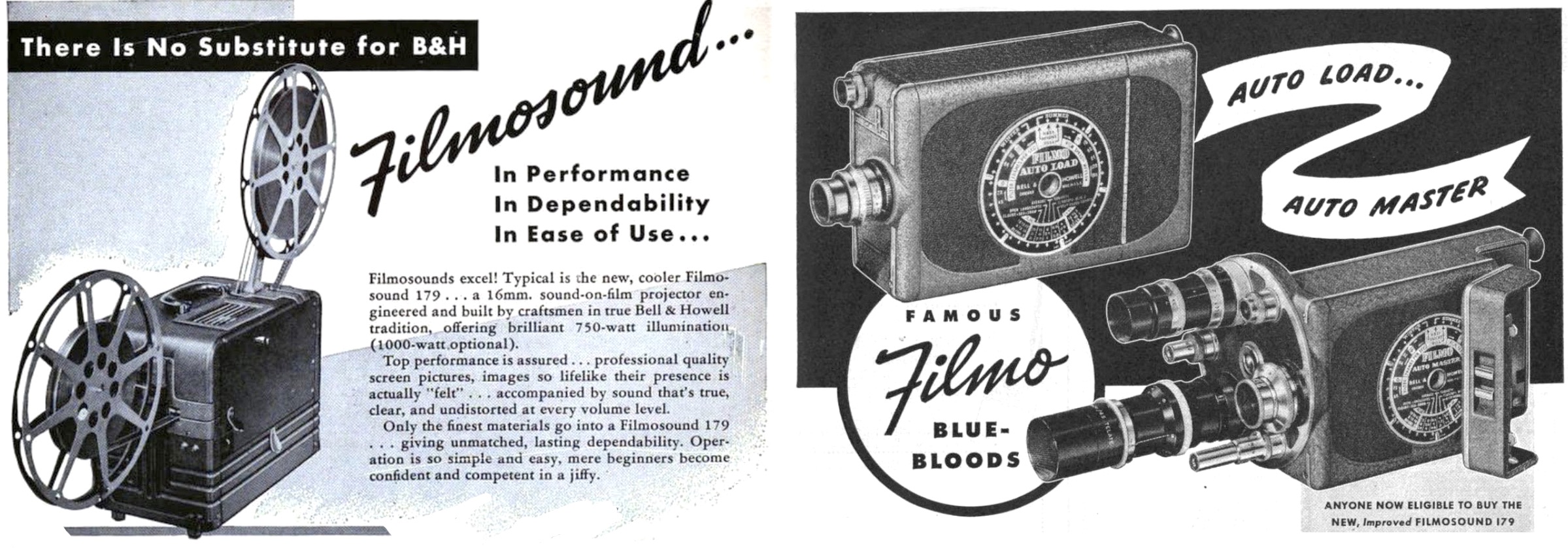

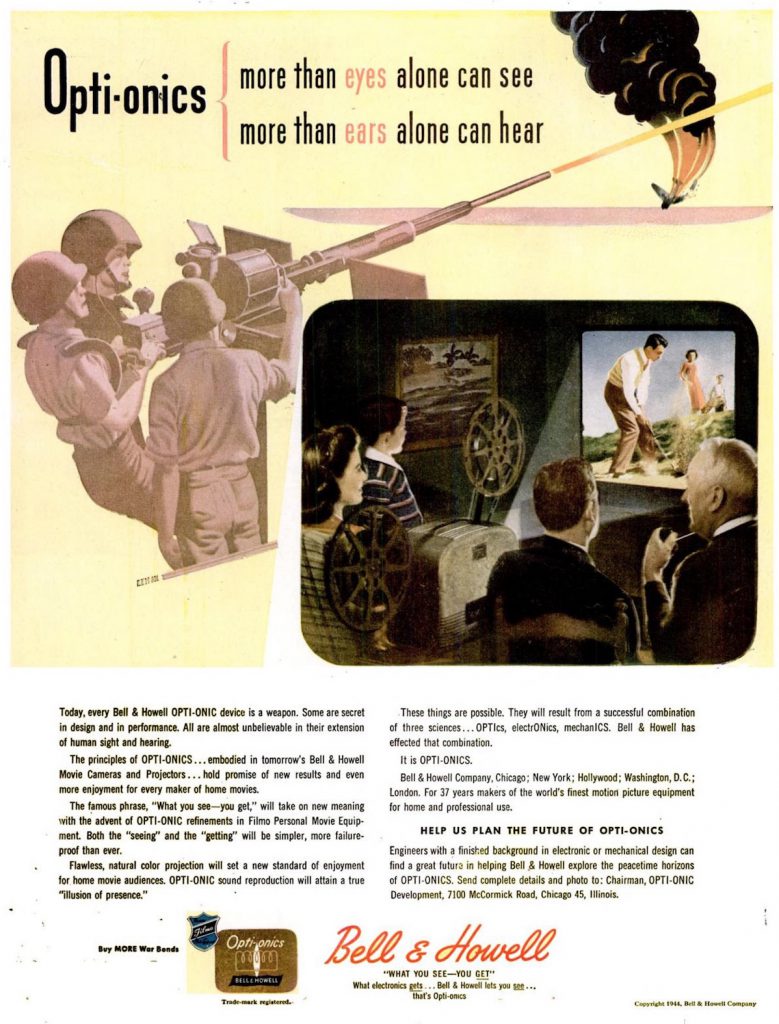

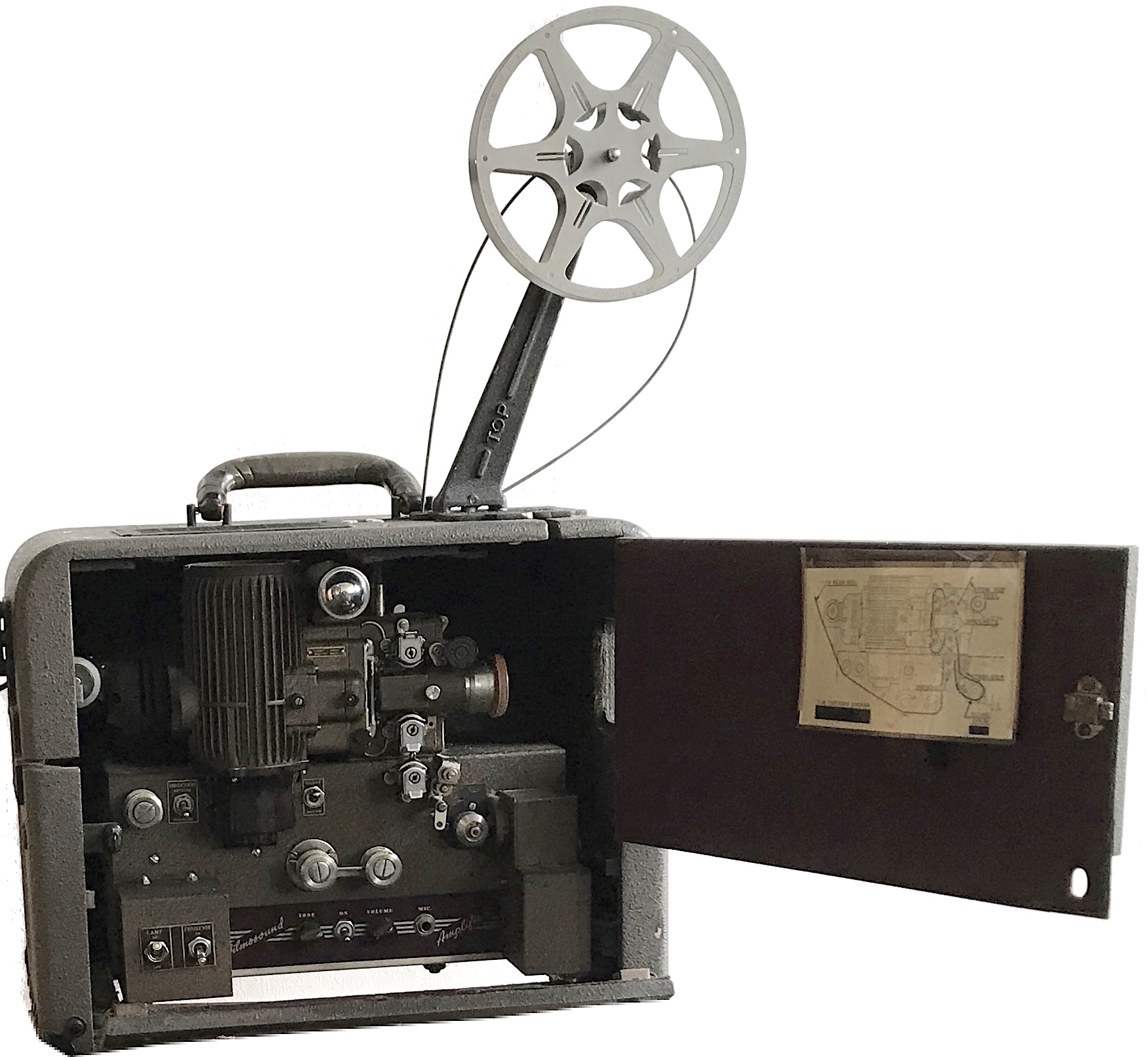

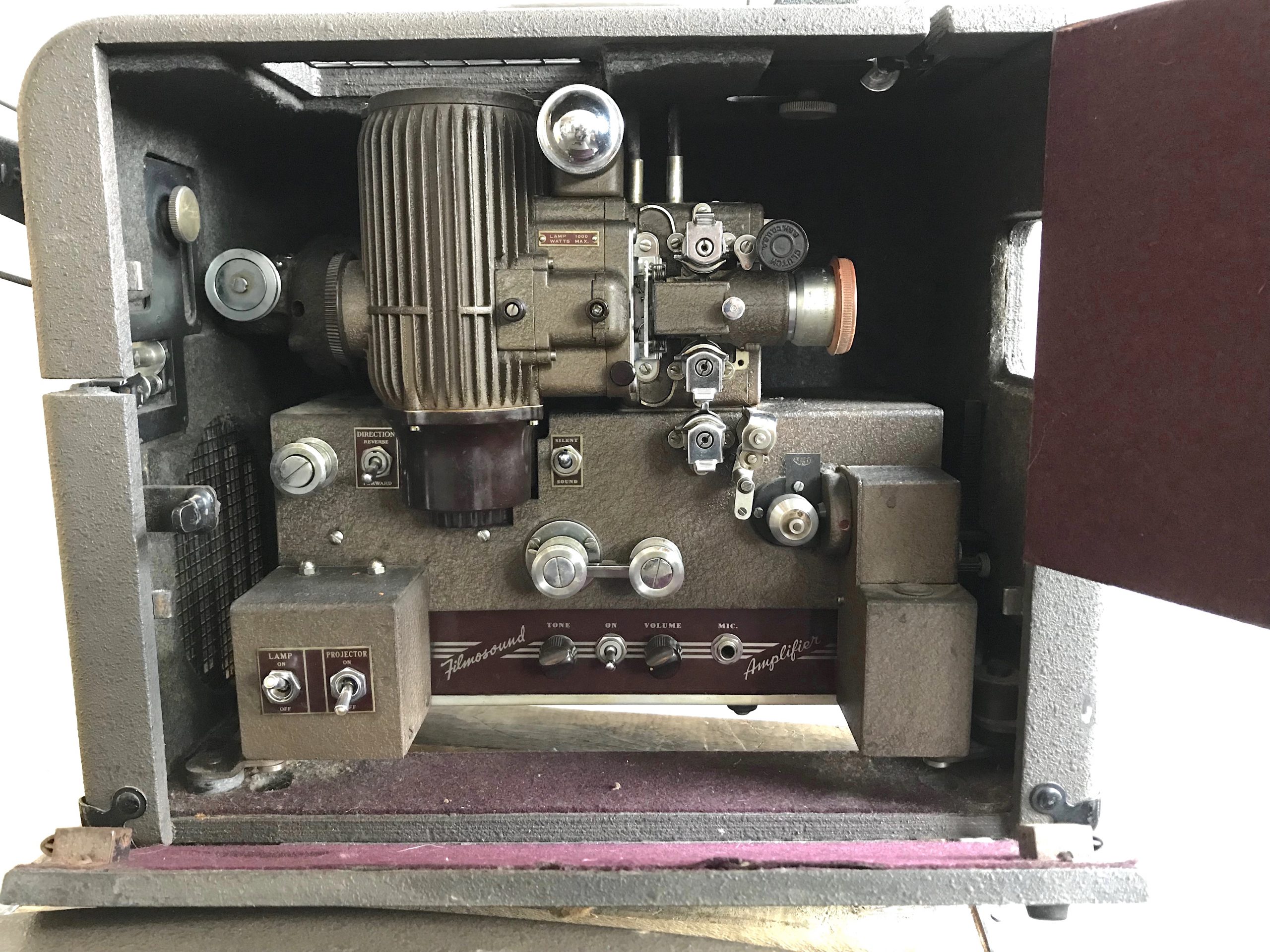

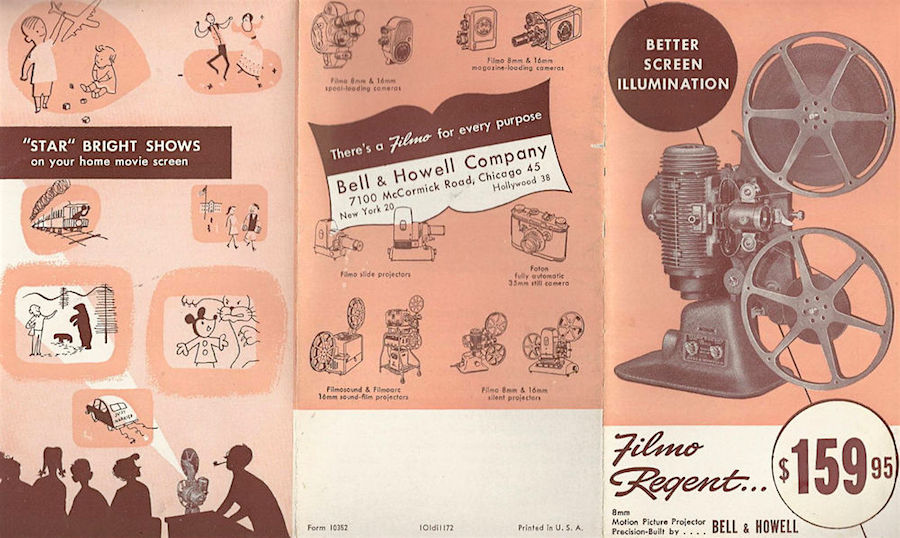

[Above: The Filmosound 179 Film Projector and Speaker, left, and the Filmo Auto Load 16mm movie camera, right, are also part of our museum collection; donated by Donald Gault, whose father purchased them in the late ’40s or early ’50s. Below: Ads for both products from the late 1940s.]

[Above: The Filmosound 179 Film Projector and Speaker, left, and the Filmo Auto Load 16mm movie camera, right, are also part of our museum collection; donated by Donald Gault, whose father purchased them in the late ’40s or early ’50s. Below: Ads for both products from the late 1940s.]

History of Bell & Howell, Part I: When Donnie Met Bert

As the folklore goes, the namesakes of B&H first crossed paths in a Chicago machine shop, although accounts of the exact when-and-how vary significantly. The Crary Machine Works on Illinois Street is a popular choice for the “where.”

Albert Howell (b. 1879) grew up in the lumber region of northern Michigan, moving to Chicago with his family at the age of 16. While working toward a degree in mechanical engineering from the Armour Institute of Technology, he zoomed through an apprenticeship and started bouncing around local mechanic shops, eventually landing at the firm of Mr. Hamilton Crary in the old Streeter Building on the river. Despite his youth and rural upbringing, Albert emerged as the standout brains of the operation—a technical savant.

Albert Howell (b. 1879) grew up in the lumber region of northern Michigan, moving to Chicago with his family at the age of 16. While working toward a degree in mechanical engineering from the Armour Institute of Technology, he zoomed through an apprenticeship and started bouncing around local mechanic shops, eventually landing at the firm of Mr. Hamilton Crary in the old Streeter Building on the river. Despite his youth and rural upbringing, Albert emerged as the standout brains of the operation—a technical savant.

Don Bell (b. 1869)—ten years Howell’s senior—was no slouch himself when it came to mechanical matters. An experienced film projectionist and designer, he was presently in the employ of the budding Chicago movie mogul George K. Spoor—future president of Essanay Studios. Bell had helped Spoor develop a new breed of projector they called a ‘Kinodrome,’ and the demanding work often entailed outsourcing repair jobs to other mechanics, which led Bell through the doors of Crary’s shop on the fateful day in question.

“At the suggestion of Mr. Crary,” Bell later recalled in a 1933 interview with The International Photographer, “I employed Mr. Howell to ‘refine’ my machine and put the design in manufacturing shape. His work disclosed extraordinary talent.”

According to that same article, published one year before Don Bell’s death, these formative events in the Bell+Howell timeline took place from the spring of 1905 into the summer of 1906. To confuse matters, though, a far more recent bit of research—done by Chicago film historians Adam Selzer and Michael Glover Smith for their 2015 book Flickering Empire—suggests that the alliance had been forged far earlier:

“In the fall of 1897, [George K.] Spoor had enlisted Don J. Bell and Albert Howell, founders of the future motion-picture equipment giant Bell and Howell, to make a new projector that he christened the ‘Kinodrome.’ The projector was ready in 1899 and became an immediate hit, far outpacing the sales of the Magniscope.”

“In the fall of 1897, [George K.] Spoor had enlisted Don J. Bell and Albert Howell, founders of the future motion-picture equipment giant Bell and Howell, to make a new projector that he christened the ‘Kinodrome.’ The projector was ready in 1899 and became an immediate hit, far outpacing the sales of the Magniscope.”

Since Howell was only an 18 year-old greenhorn in 1897, that version of events seems far less likely than the 1933 account direct from the horse’s mouth. But, not having been there myself, I must digress.

In whichever origin story you prefer, the key point is the same: Don Bell was impressed “by the young machinist’s inventive ingenuity”—as the Encyclopedia of American Biography later put it. From there, it seems logical to presume that Bell became something of a mentor to young Bert Howell in the years that followed, showing him the ropes of the projectionist’s trade and eventually offering to go into business with him.

When the duo officially launched their new company in 1907—organized with a mere $5,000 in capital stock—it was Bell who served as chairman. Howell, at age 28, was the secretary and chief engineer. With little more than a dozen employees on staff and half their workload mired in freelance repair gigs, Bell also became the de facto salesman for the new business, spreading the word about Bert Howell’s growing list of exciting celluloid innovations. The combination of the genius and the hype-man paid off, as the Bell & Howell Company’s success and long term legacy would both be sealed within its first two years.

[Albert S. Howell, left, and Donald J. Bell, assessing their contributions to history]

II. Howell at the Moon

“If you already own a B&H camera,” another ’40s era Bell & Howell promotional pamphlet would later claim, “you will be interested in learning how your camera had its genesis back in the days when your father was going to ‘nickel shows.’ You own a thoroughbred, and here we give you its pedigree.”

That pedigree—a proud selling point of B&H products for the better part of 60 years—was rooted in Albert Howell’s singular efforts to standardize the mathematics of movie making.

[Charlie Chaplin, like most filmmakers of his time, embraced Bell & Howell tech on set]

In those aforementioned nickelodeon days of yore, moving pictures—in all their silent, awkward flickerdom—were the most in-demand new form of entertainment in the world. But the popularity of the medium was moving much faster than the technology to properly harness it.

For a good decade or so, filmmakers, camera manufacturers, distributors, and projectionists all enthusiastically jumped into their stables without ever properly writing down the rules of their shared game. Most critically, the functional lifeblood of their industry—the physical film itself—was an undefined resource, produced in dozens of different sizes and perforation patterns. The resulting chaos created ridiculous situations where a popular film in one Chicago movie house wouldn’t fit the projector in another one down the street—or a film that did well in Milwaukee wouldn’t play properly in Chicago at all. After a while—as tends to happen when people are quickly spoiled by new wonders—complaints increased. Inconsistency in film and the unsteady hands of some projectionists (remember, you needed the arm strength of a Major League pitcher to play a film in the handcrank era) created staggered, sometimes flip-flopped images and frustrated patrons.

“Into this technical turmoil came a young engineer with ideas,” proclaims the B&H brochure, “and it was only when the Bell & Howell Company entered the picture, in 1907, that the early movies stopped jumping around and settled down to stay on screen. Albert S. Howell, who still lives to guide with his genius our every engineering move, selected 35mm as the one most practical width, and straightaway proceeded to build motion picture equipment of surpassing accuracy and precision, for that size only. When the producers and exhibitors of the day found that movies made and processed with Bell & Howell equipment neither flickered nor jumped, nor showed the lower half of the picture on the upper half of the screen and vice versa, they gradually changed to Bell & Howell.”

“Into this technical turmoil came a young engineer with ideas,” proclaims the B&H brochure, “and it was only when the Bell & Howell Company entered the picture, in 1907, that the early movies stopped jumping around and settled down to stay on screen. Albert S. Howell, who still lives to guide with his genius our every engineering move, selected 35mm as the one most practical width, and straightaway proceeded to build motion picture equipment of surpassing accuracy and precision, for that size only. When the producers and exhibitors of the day found that movies made and processed with Bell & Howell equipment neither flickered nor jumped, nor showed the lower half of the picture on the upper half of the screen and vice versa, they gradually changed to Bell & Howell.”

A 1929 issue of American Cinematographer later credited Howell for having “attacked the problem with the thoroughness and patience of a man of science coupled with the enthusiasm of a pioneer.

“The work conducted by Mr. Howell in the field of standardization not only demanded a broad vision and great confidence in the future of the then nascent industry, but also a courage of convictions, which was most admirable, especially considering the opposition which usually characterizes any revolutionary enterprise.”

[Women work the standardized film perforation stations at the Bell & Howell plant, c. 1910]

[Women work the standardized film perforation stations at the Bell & Howell plant, c. 1910]

Of course, it wasn’t really that Bell & Howell convinced people to start using standardized 35mm film through some sort of courage, charm, or peer pressure. They moved the industry because they also produced the best new camera equipment of the period, and by making this equipment compatible only with the 35mm film, they essentially controlled the movement of the tides in their industry.

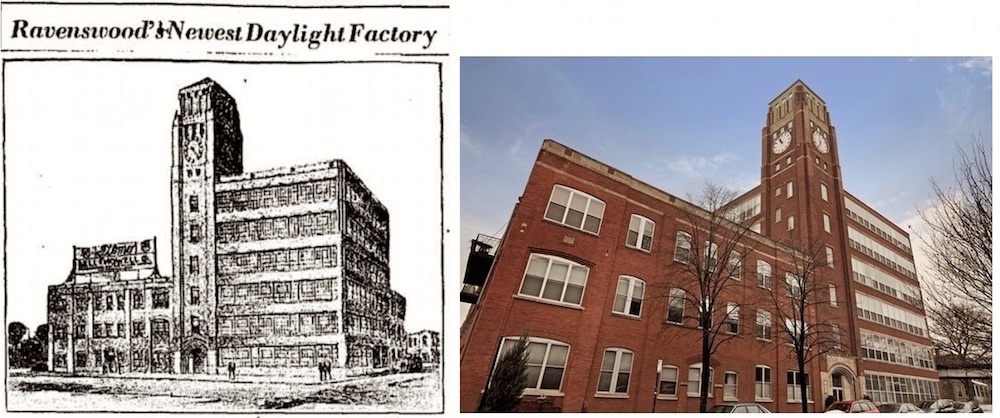

Howell’s precision Cinematograph camera, along with updated versions of the Kinodrome projector and a new film perforator machine, turned the Bell & Howell Co. from a glorified repair shop into the unchallenged manufacturing leader in the movie biz, equipping just about every film set from New York to Chicago to an up-and-coming village called Hollywood. By 1914, the company had expanded to more than 80 employees, with a new large-scale Chicago factory space at 1801 W. Larchmont Avenue, featuring a distinctive clock tower. The building is still standing today, having been converted into luxury apartments in the 1990s.

[The former Bell & Howell headquarters at 1801 W. Larchmont Ave. in North Center]

[The former Bell & Howell headquarters at 1801 W. Larchmont Ave. in North Center]

III. For Whom the Bell Tolls

As mentioned, Don Bell didn’t necessarily take this massive new success in stride. While he was out selling the Bell & Howell name across the country, he started developing a growing paranoia about how the business was being run back in Chicago. One of Bell’s own hires, general manager Joseph McNabb, became a particular thorn in his side.

Things reached a head in 1917, as Bell—supposedly feeling McNabb and Howell were conspiring to undermine his control of the company—made the bold (or massively dumb) move of firing both men. Rather than accepting their walking papers, though, Howell and McNabb returned the next day with some paperwork of their own, and a rational alternative. They would buy out Bell’s interest in the company for a little under $200,000, sending the 52 year-old to an early retirement. This was probably a rough, bittersweet pill for Don Bell, the man who’d ostensibly introduced Bert Howell to the magic of movies in the first place (Bert had even named his first son “Don”). But, like a mutinied ship captain, Bell took the offer and bowed out.

Things reached a head in 1917, as Bell—supposedly feeling McNabb and Howell were conspiring to undermine his control of the company—made the bold (or massively dumb) move of firing both men. Rather than accepting their walking papers, though, Howell and McNabb returned the next day with some paperwork of their own, and a rational alternative. They would buy out Bell’s interest in the company for a little under $200,000, sending the 52 year-old to an early retirement. This was probably a rough, bittersweet pill for Don Bell, the man who’d ostensibly introduced Bert Howell to the magic of movies in the first place (Bert had even named his first son “Don”). But, like a mutinied ship captain, Bell took the offer and bowed out.

The company thus entered the roaring ‘20s with a breath of new life, as McNabb soon took over the role of president, with Howell staying on as VP and Charles Ziebarth serving as secretary. All three men would remain in leadership roles with the firm for the next several decades, as the Bell & Howell Co. gradually turned its attention increasingly to the amateur market.

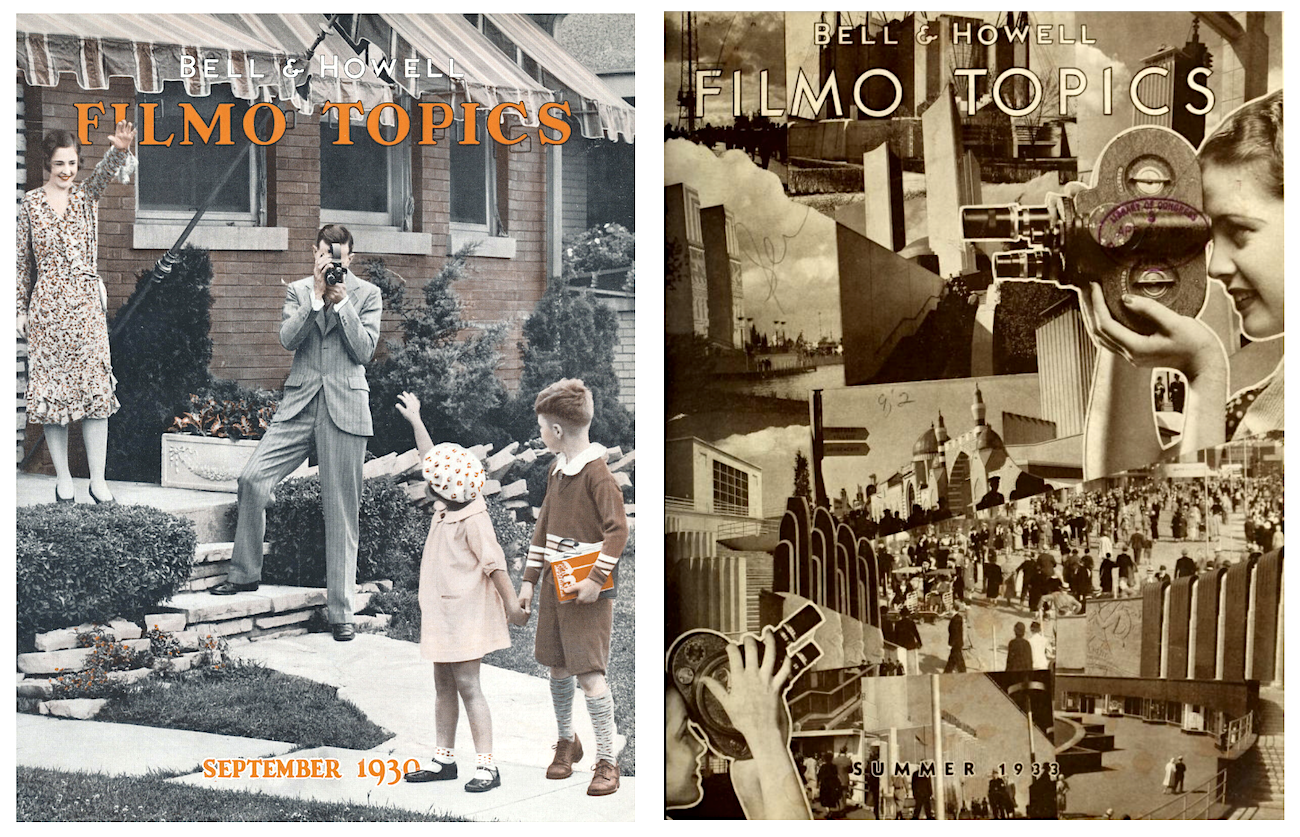

[Covers of the September 1930 and Summer 1932 issues of Bell & Howell’s company magazine, Filmo Topics]

[Covers of the September 1930 and Summer 1932 issues of Bell & Howell’s company magazine, Filmo Topics]

IV. Make Your Own CinePictures

“Unsatisfied to stop with giving 15 million people a day a movie show to go to, Bell & Howell has turned the back yard, the golf club, the athletic field, or the deck of a liner into a Hollywood ‘lot’—has made it not only possible but easy and inexpensive for the individual to take and show his own movies.”

—Filmo Topics, 1932

Along with opening offices in New York and L.A., Bell & Howell doubled the size of its Larchmont Avenue plant by 1925 and increased its Chicago workforce to 500, as McNabb’s foresight on the potential of the home market—combined with Howell’s undying idea machine—led the business into its next golden age.

In that 20-30 year span between the birth of radio and the arrival of television, home entertainment experienced another comparatively overlooked leap forward, as new safety film in 16mm brought the excitement of the picture-house into the living room for the first time. This included professional Hollywood films sold for viewing on home projectors, as well as “personal motion pictures” or “cinepictures”—made by the customer’s own hand on increasingly manageable and intuitive home movie cameras.

In that 20-30 year span between the birth of radio and the arrival of television, home entertainment experienced another comparatively overlooked leap forward, as new safety film in 16mm brought the excitement of the picture-house into the living room for the first time. This included professional Hollywood films sold for viewing on home projectors, as well as “personal motion pictures” or “cinepictures”—made by the customer’s own hand on increasingly manageable and intuitive home movie cameras.

“They had to be so simple that anyone could use them,” Filmo Topics noted. “And they had to be so perfect that the amateur could obtain professional results. For was not a high standard of motion picture quality already established in the individual’s mind, directly by the feature plays seen in theaters, and indirectly by the Bell & Howell Company itself?”

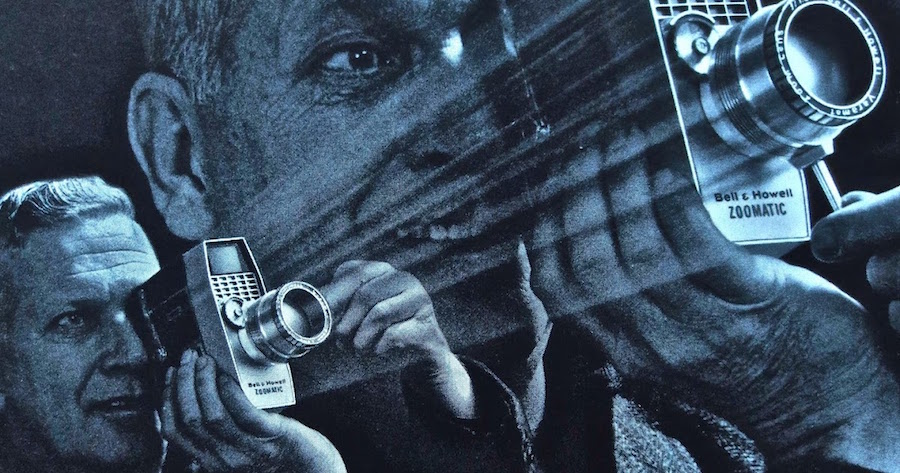

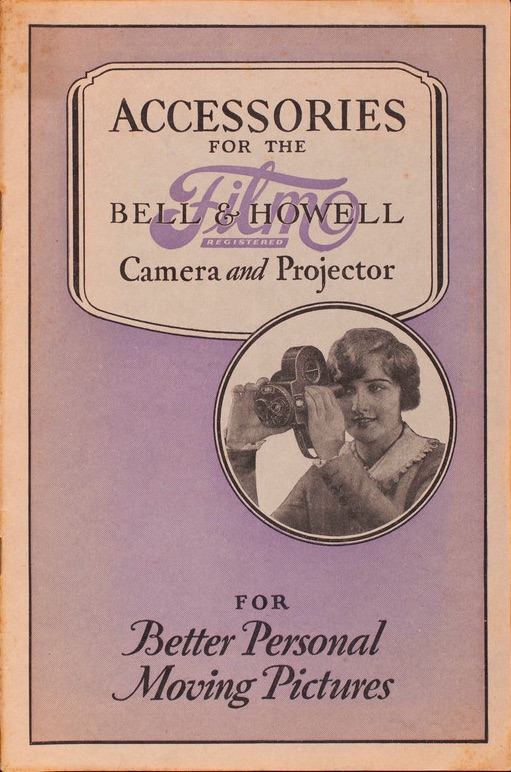

Starting with its early “Filmo” brand, Bell & Howell managed a pretty flawless transition into becoming the most innovative and respected name in home movie equipment, consistently making products that were more efficient and dependable than the competition, if also a tad more expensive (a price tag of $150-200 for early cameras basically made it a rich man’s hobby).

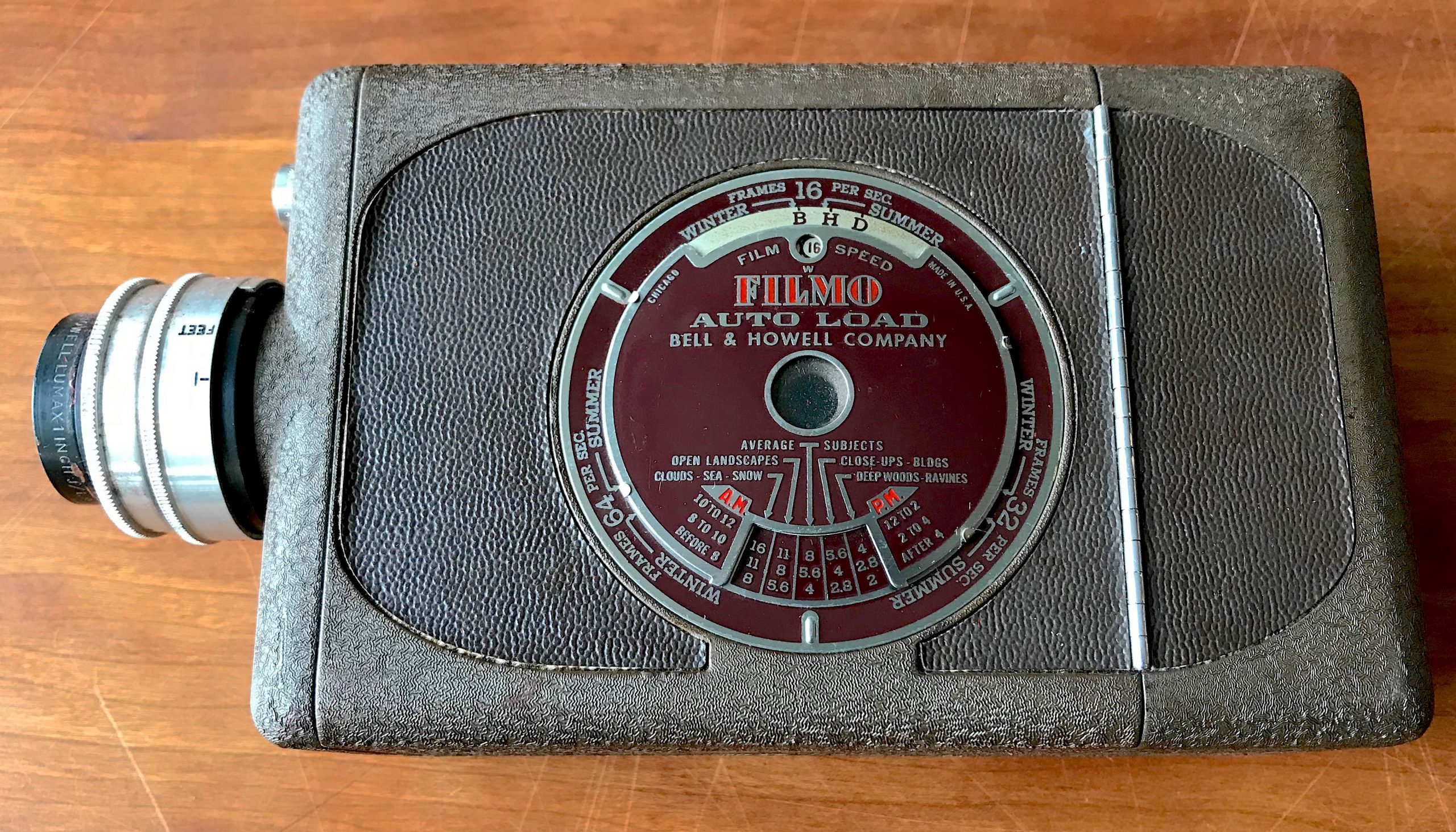

Albert Howell remained the company’s chief engineer through the 1930s, and helped B&H rebound from the first few years of the Depression to again jump ahead of the class with innovations like the Filmosound 16mm sound-on-film projector and a new line of pocket-sized, “Auto Load” home movie cameras.

“For three decades, Mr. Howell has devoted all his time to the perfection of motion picture equipment,” hailed the 1938 Encyclopedia of American Biography, “and without his labors the current high technical standards of the industry would be impossible. He has obtained patents on over one-hundred and fifty inventions, which have been incorporated in the products of the Bell and Howell Company. . . In addition to his technical achievements, Mr. Howell also bears important executive responsibilities as vice-president of the Bell and Howell Company, directing the activities of a staff of engineers and technicians, the large laboratories, as well as the general production plant of the company, which employs 1,000 workers.”

“For three decades, Mr. Howell has devoted all his time to the perfection of motion picture equipment,” hailed the 1938 Encyclopedia of American Biography, “and without his labors the current high technical standards of the industry would be impossible. He has obtained patents on over one-hundred and fifty inventions, which have been incorporated in the products of the Bell and Howell Company. . . In addition to his technical achievements, Mr. Howell also bears important executive responsibilities as vice-president of the Bell and Howell Company, directing the activities of a staff of engineers and technicians, the large laboratories, as well as the general production plant of the company, which employs 1,000 workers.”

In a development that would have seemed impossible even in the fruitful days of the 1920s, the Larchmont plant was beginning to look too small for Bell & Howell’s massive operation. This problem was only amplified when World War II set the company into its biggest years to date, as McNabb and Howell raced to keep up with an upswing in juicy government contracts.

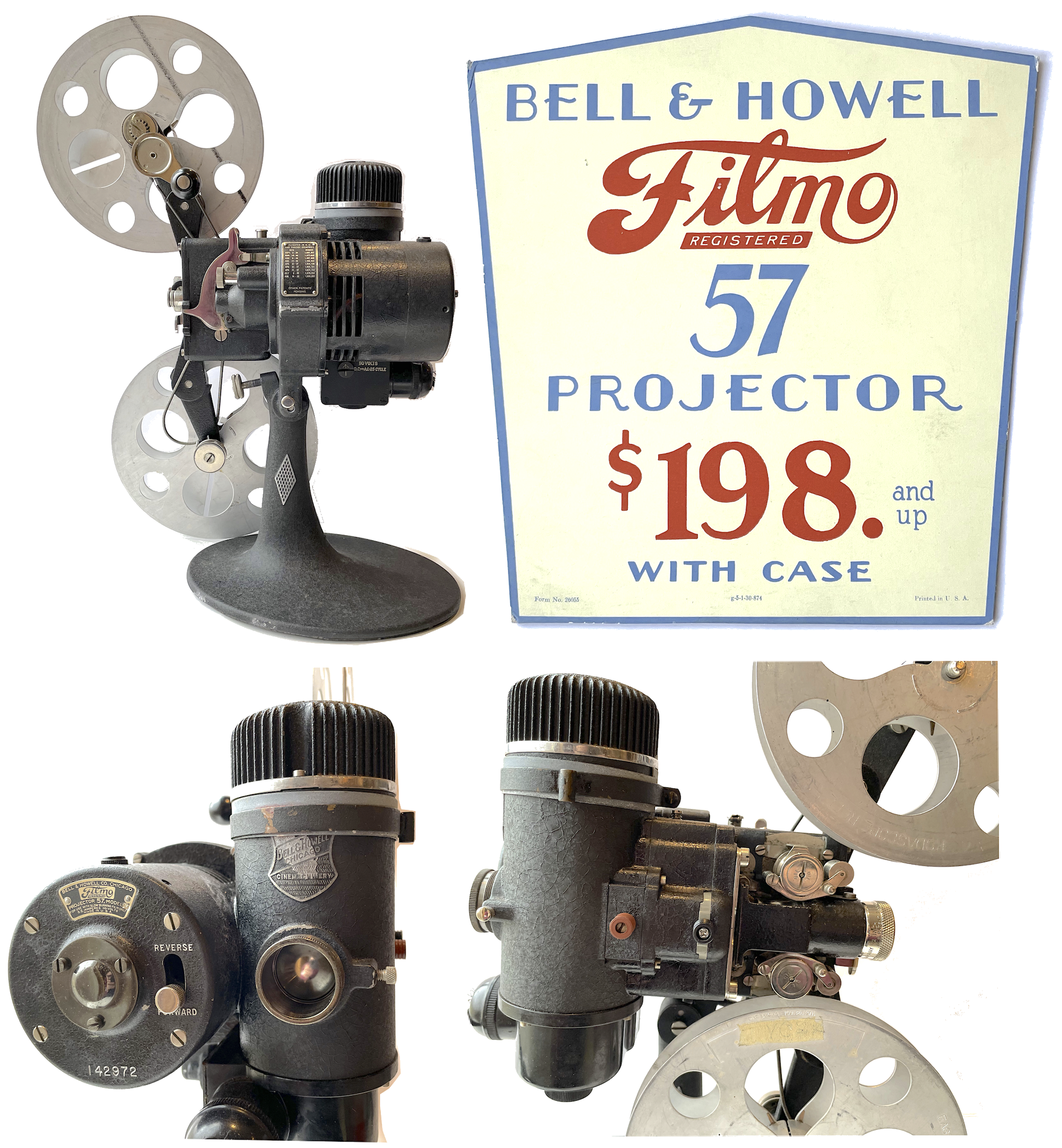

[This Filmo 57 16mm Projector, Model GG, is also part of our museum collection, along with the advertising display sign promoting it. The machine was donated by Bill Thomas, whose grandfather originally purchased it in the 1930s. “The wonderful picture clarity and brilliance seen at a modern theater are yours with this new Filmo,” read a 1931 ad. “Its scientific design gives movies of professional quality; its utter simplicity lets a child operate it.”]

V. The War Boom

“Skylights once brought sunshine to Bell & Howell employees in the Larchmont Building,” Chicago Reader scribe Wende Zomnir wrote in 1994, looking back at the history of the old factory shortly before its conversion into lofts. “But in the early 1940s, the skylights were covered with black tar to conceal wartime tasks performed for the U.S. government. Bell & Howell adapted motion picture cameras like the Eyemo for military use, even painting them regulation army green. The company made tiny cameras to record the accuracy of guns and other artillery. When blockades prevented getting critical supplies from overseas, Bell & Howell started crafting sophisticated lenses, its most important contribution to the war effort. The Bell & Howell retriflector sight was called the ‘eye’ of the B-29 bomber.

“Skylights once brought sunshine to Bell & Howell employees in the Larchmont Building,” Chicago Reader scribe Wende Zomnir wrote in 1994, looking back at the history of the old factory shortly before its conversion into lofts. “But in the early 1940s, the skylights were covered with black tar to conceal wartime tasks performed for the U.S. government. Bell & Howell adapted motion picture cameras like the Eyemo for military use, even painting them regulation army green. The company made tiny cameras to record the accuracy of guns and other artillery. When blockades prevented getting critical supplies from overseas, Bell & Howell started crafting sophisticated lenses, its most important contribution to the war effort. The Bell & Howell retriflector sight was called the ‘eye’ of the B-29 bomber.

“It’s hard to believe,” Zomnir added, “that the space around me once housed automatic screw machines and punch presses that ran not from electricity fed directly into each machine, but from energy generated and passed along by huge spinning belts and wheels that hung from the ceiling like a web, each strand powering a machine. Some of the guys who operated this equipment liked working at Bell & Howell. It was considered a good job. The company boasted that one employee on its industrial league baseball team chose his job at Bell & Howell over a spot on the Cubs roster. Workers who bowled were never kept late on Monday night, even during inventory.”

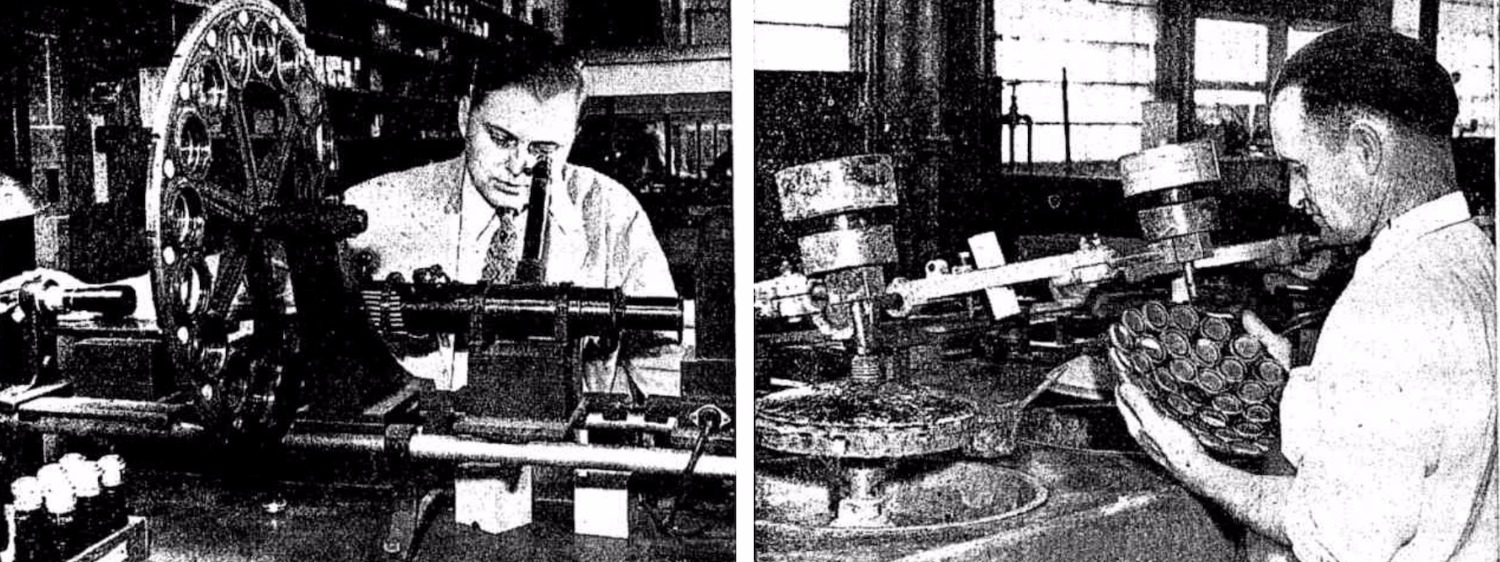

[Bell & Howell employees Paul Rettberg, left, and William Little at work in the company’s photographic and projection lens department, the largest such operation in the Midwest, 1948]

[Bell & Howell employees Paul Rettberg, left, and William Little at work in the company’s photographic and projection lens department, the largest such operation in the Midwest, 1948]

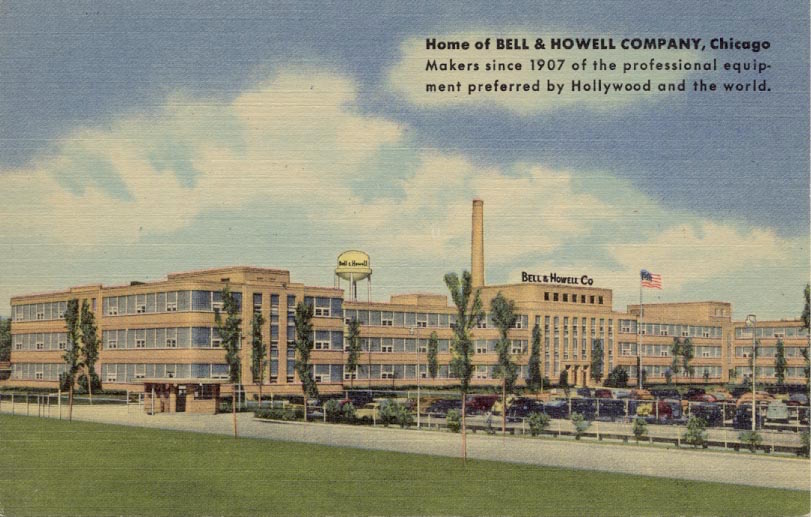

By the time B&H started migrating from the Larchmont plant to a ginormous new modern facility in Lincolnwood in 1943 (at 7001 McCormick Rd), there were upwards of 3,00 Chicagoans on its payroll, many cut in the same mold as Albert Howell himself: precise, dedicated, and highly skilled. During the war, when a large number of employees were called to military service, a new influx of workers (many of them women and minorities) helped the B&H operation transform seamlessly into a defense plant. New recruits were inspired to stay, while servicemen overseas looked forward to returning to their civilian jobs. There seemed to be room for everybody.

[Bell & Howell moved into this complex near Skokie in 1943]

[Bell & Howell moved into this complex near Skokie in 1943]

When the war finally did end, however, the good feeling didn’t carry over to Bell & Howell’s stock, which had just gone public in 1945. Losing those valuable government contracts took a massive bite out of the company’s profits, and growing competition from camera-makers both domestic and foreign posed plenty of new challenges.

By now, Albert Howell had removed himself from the chief engineer gig, staying on as a board member. When longtime company president Joseph McNabb died in 1949, Howell stepped into the role of Chairman, hoping to lend a guiding hand to McNabb’s 29 year-old successor, Charles Percy. Unfortunately, Howell met his own end two years later at the age of 72, leaving the baby-faced Chuck Percy facing an uncertain future in an increasingly competitive market.

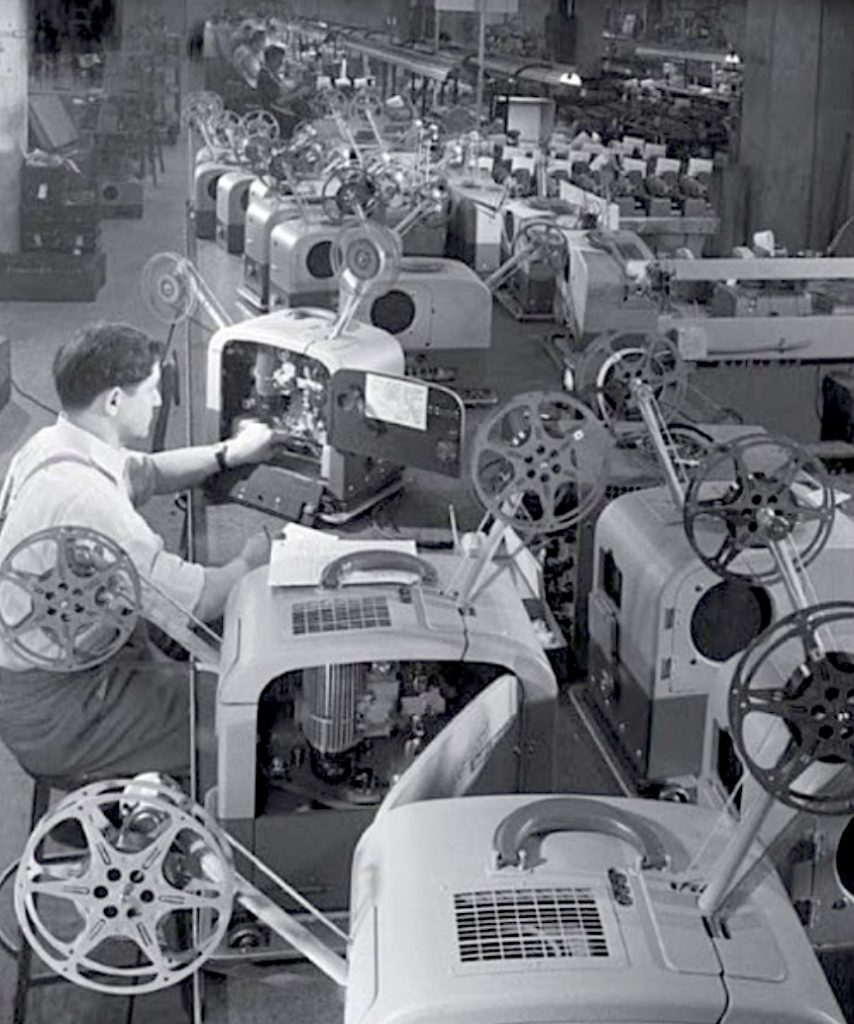

[Assembly and inspection of B&H Filmosound projectors, circa 1950s]

[Assembly and inspection of B&H Filmosound projectors, circa 1950s]

VI. Our Post-War Museum Pieces in Context

It was during these same years of transition, surrounding the deaths of McNabb and Howell and the rise of Percy, that the items in our museum collection were all at the apex of their popularity.

The Filmo Auto Load 16mm Movie Camera and Filmosound 179 Projector had both debuted during the war years, while the 8mm 172 camera came along a few years after. Offering unprecedented ease-of-use and middle class affordability, this equipment was almost standard issue for the modern, suburban American family, with its 2.5 baby-boom kids in tow. Soon, every attic had stacks of home movie canisters with taped-on labels: “Trip to Grand Canyon, 1952,” “Bobby’s Birthday, 1949.”

Here’s how our museum artifacts were promoted in their time:

The Filmosound 179 Projector

The Filmosound 179 Projector

“The new, cooler Filmosound 179 . . . a 16mm sound-on-film projector engineered and built by craftsmen in true Bell & Howell tradition, offering brilliant 750-watt illumination (1000-watt optional).

“Top performance is assured: professional quality screen pictures, images so lifelike their presence is actually ‘felt,’ accompanied by sound that’s true, clear, and undistorted at every volume level.

“Only the finest materials go into a Filmosound 179, giving unmatched, lasting dependability. Operation is so simple and easy, mere beginners become confident and competent in a jiffy.”

Years later, people came to realize that the Filmsound speaker box could be reconfigured into a hell of a guitar amp, as well, but that’s another story.

The Filmo Auto Load Camera 153

The Filmo Auto Load Camera 153

“For those who delight in the possession of finer things, this new Filmo Auto Load Motion Picture Camera exemplifies the superb craftsmanship for which Bell & Howell is famous, and presents a host of exclusive new features that simplify the making of better motion pictures.

“Effortless loading; vastly increased brilliance in a positive-type viewfinder; unmistakable exposure chart reading; four speeds including slow motion; single-frame exposure; no operating obstacles in the path of the beginner; no limitations upon the most advanced skill. Precision-built by the makers of Hollywood’s professional motion picture equipment, Filmo Auto Load provides easy mastery of every picture opportunity.”

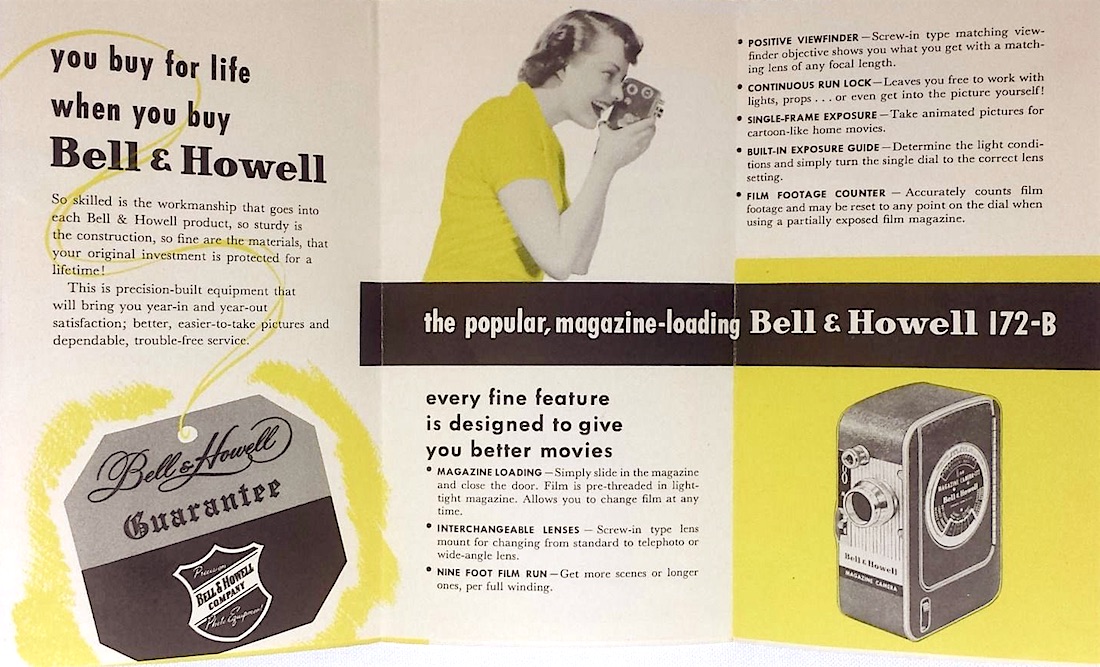

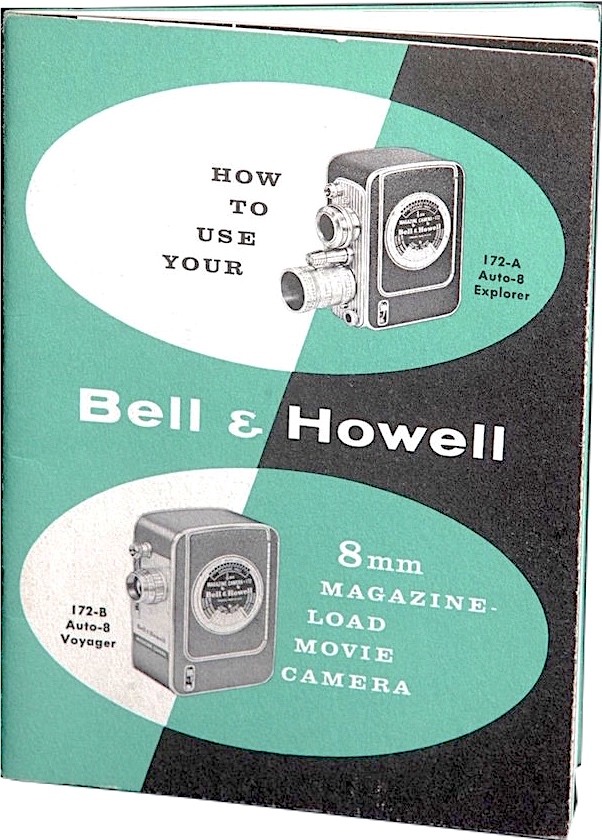

The 8mm 172 Movie Camera

The 8mm 172 Movie Camera

“NOW— a new Bell & Howell easy-loading movie camera for only $129.50. . . Never before has there been a real Bell & Howell at this low price with all these features:

>Easy magazine-loading. Load and unload in full daylight

>No threading, no bother

>Low-cost operation. Uses inexpensive 8mm film

>Single lens quickly interchangeable

>Five speeds, including true slow motion

>Single frame release and Selfoto lock

>Positive type viewfinder

>Accurate film footage indicator & Built-in exposure guide

>Beautiful, lightweight and modern design”

Now, a price tag of $130 in 1950 equates to about $1,300 in today’s money after inflation, so while the model 172 was set at a relatively “low price” compared to the old industry standard, it was hardly an “impulse” sort of purchase. But, much in the way we pony up for a new laptop or smart phone, the hi-tech novelty and excitement created by a pocket-sized movie camera was more than enough to move units in the ’50s. A guaranteed warranty also suggested that the investment would be worth its weight in captured memories. Half a century before Youtube, the era of documenting one’s life in moving pictures had begun.

[Top Left: Actress Betty Hutton promoted Bell & Howell’s Auto Load cameras in 1944, shortly before marrying Ted Briskin, president of B&H’s Chicago rivals, the Revere Camera Co. Top Right: 1950 ad for the 8mm Model 172 Magazine Camera. Below: 1950 sales pamphlet for the 172-B]

VII. The Golden Child

There were plenty of raised eyebrows, both in Chicago and around the world, when the Bell & Howell board named Charles H. Percy the successor to the late J.H. McNabb in 1949. The choice was far less of a surprise in the B&H offices, though, where Percy—despite not having yet turned 30—had already spent 12 years as the boss’s handpicked heir.

Much like the first meeting of Don Bell and Albert Howell three decades prior, the tale of Joe McNabb’s initial encounter with Chuck Percy became the stuff of legend. In one version of events, McNabb was actually Percy’s Sunday school teacher, and came to appreciate the smarts and ambition of New Trier High School’s standout student. Accordingly, he decided to sponsor Percy as he worked his way through the University of Chicago and a stint in the navy during WWII.

Much like the first meeting of Don Bell and Albert Howell three decades prior, the tale of Joe McNabb’s initial encounter with Chuck Percy became the stuff of legend. In one version of events, McNabb was actually Percy’s Sunday school teacher, and came to appreciate the smarts and ambition of New Trier High School’s standout student. Accordingly, he decided to sponsor Percy as he worked his way through the University of Chicago and a stint in the navy during WWII.

In an alternate account, reported by the Chicago Tribune on the occasion of Percy’s rise to the presidency, “Percy’s advancement in the company is the product of his own efforts… Without sponsorship, he started to work for the company in 1936 at $12 a week when he walked into McNabb’s office and asked for a job under the company’s co-operative training program. This program had been established by McNabb to develop young executives from promising high school and college men.”

Again, the exact route Percy took is probably less important than the fact he aced every test—with no shortage of obstacles in his path. Along with escaping poverty during the Depression and serving his country during the war, Percy also lost his first wife Jeanne at a very young age, leaving him a widower with two twin daughters and a son all yet to start kindergarten. Even the unique opportunity of moving up the corporate ladder was made more difficult by uncontrollable circumstances, as the deterioration of McNabb’s health in the late ‘40s had actually pushed Percy into a high-stress role with Bell & Howell long before his promotion was official. When he finally did assume the presidency, there would be yet more hurdles to leap.

“Percy is believed to be the youngest president of a major industrial enterprise in the country,” the Tribune reported at the time, with a very subtle skepticism baked in.

At 29, he was younger than most of Albert Howell’s patents, but his shoulders now carried the responsibility of 2,000 employees at a company in the midst of a 40-percent drop in sales since the end of the war. Within another two years, Albert Howell would be dead and competition in the home movie market would be increasingly fierce. And yet . . . the kid rolled with the punches.

Charles Percy’s 14 year run as B&H president was so successful, in fact, that he managed to reach heights even Joseph McNabb had never envisioned for him.

Armed with the good looks and commanding voice of a politician, Percy eased the minds of worried investors and aggressively pursued new profit avenues for Bell & Howell. He purchased and absorbed a number of smaller companies in the 1950s, breaking into microfilm, slide projectors, stereo systems, tape recorders, and even aviation equipment. B&H grew from $13 million in sales in 1949 to $160 million by 1963, with an employee base nearly quadrupling to 7,500.

Eventually, Percy’s reputation was so sterling that he actually became the politician he’d always looked like. The moderate Republican left Bell & Howell to run for governor of Illinois in 1964, narrowly losing. Two years later, he ran for a U.S. Senate seat and won it. The campaign, however, was a somber one.

Eventually, Percy’s reputation was so sterling that he actually became the politician he’d always looked like. The moderate Republican left Bell & Howell to run for governor of Illinois in 1964, narrowly losing. Two years later, he ran for a U.S. Senate seat and won it. The campaign, however, was a somber one.

In the darkest chapter of Percy’s life to date, one of his 21 year-old daughters, Valerie, was violently murdered in the family home that September by an unknown assailant. Charles halted his campaign for weeks, but eventually returned to the trail and earned a surprising victory. His daughter’s murder case, however, carried on unsolved for another 20 years, and was eventually abandoned as such. Robbery was ruled out, and to this day, no firm suspect has ever emerged.

It’s worth noting that Charles Percy never had any suspicion thrown his way either. Instead, he became one of the more revered Republicans of the 1970s, taking a stand against Richard Nixon during Watergate and gaining a lot of buzz for a possible presidential run of his own, which never came. In the end, Percy’s old school, bipartisan ethics made him unwelcome in the modern Republican party, and he finally lost his seat to Democrat Paul Simon in 1984. Percy died in 2011 at age 91, remembered far more for his political career than his Bell & Howell exploits.

VIII. The Iris Closes

After Percy left, the humorously named Peter Peterson took over as Bell & Howell president, and he mostly followed in his predecessor’s footsteps, investing in new opportunities and expanding B&H’s marketplace into radio equipment, copy machines, and communications tech for the space-age. In 1970, five years after Kodak shook up the industry with its “Super 8” film, Bell & Howell established its own new industry standard with the “Auto 8” Movie Cassette System, which allowed a movie to be snapped on to a projector without having to load it on to a reel—a direct precursor to the age of video tape.

When many of the big European manufacturers adopted the Auto 8 cassette standard over the one Kodak had introduced, it seemed like a potentially game-changing win. “It certainly reinforces our stature as the foremost projector manufacturer in the world,” said Gordon Bradt, B&H’s vice president of Engineering and Product Management at the time. On the heels of this success, overall sales nearly eclipsed $300 million by the end of 1970, but the company’s profit margin was still decidedly less impressive. The considerable expense of innovation was getting harder to make up for in an increasingly competitive audio-visual ecosystem.

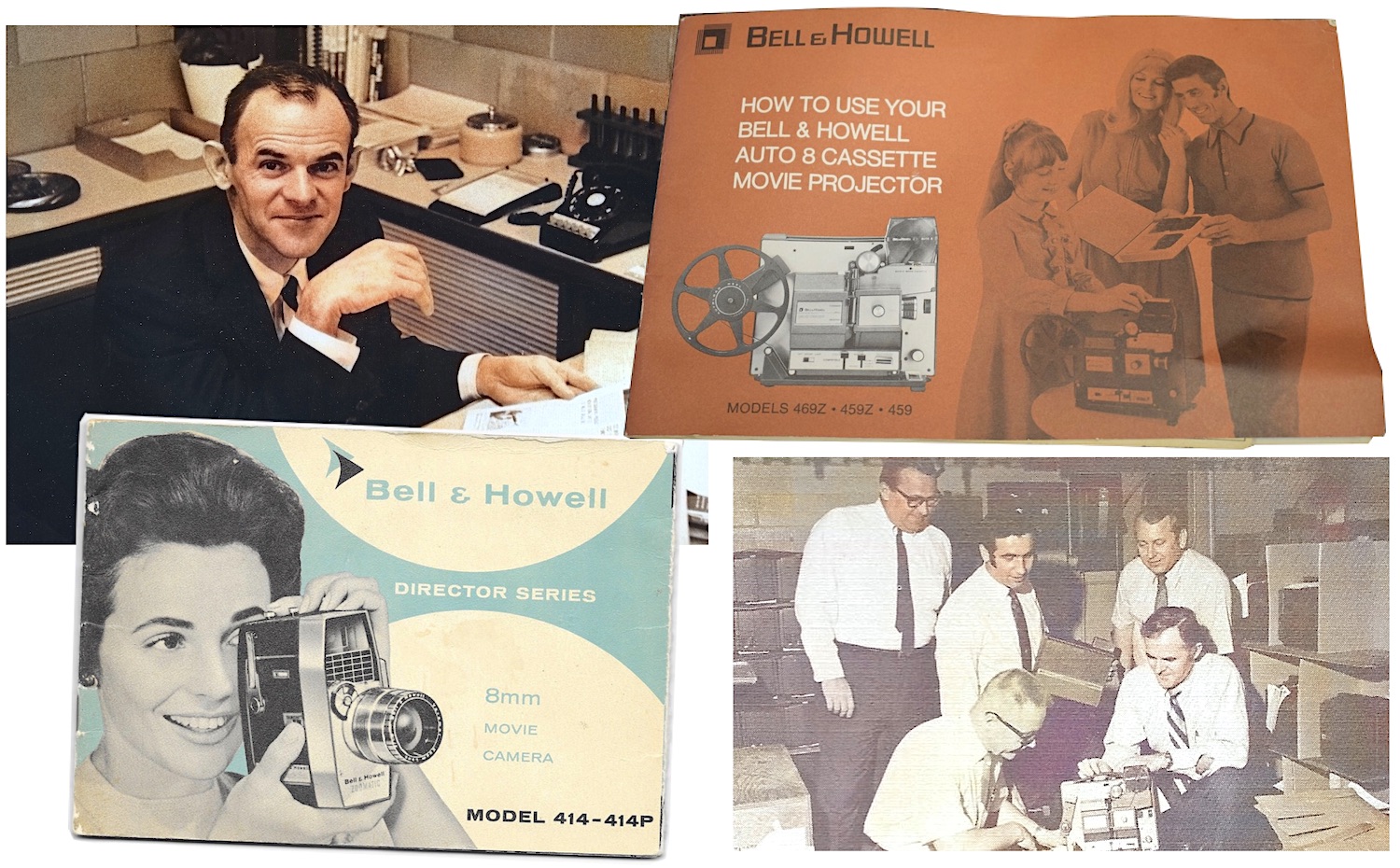

[Gordon Bradt (top left) was an engineer with B&H from 1950-1973, and helped lead the development of the Auto 8 Movie Cassette System (top right) in 1969-70. Bottom Right: Bradt is pictured with other members of his team in 1970 – from left, standing: Frank Windsor (Projection Systems Manager), Tom Rappel (Product Manager), and Ed Urban (Asst VP, MFG) – kneeling: Jerry Cherniavskyj (Chief Engineer) and Bradt. After leaving B&H, Bradt launched Kinetico Studios in 1973. Photos courtesy of his daughter Terri Bradt.]

One year later, when Peterson followed Percy into a role in Republican politics, his successor—Donald Frey—looked at the analytics and decided Bell & Howell’s future owed no allegiance to its past. By the mid 1970s, the company had ceased all manufacturing of its legendary movie cameras and projectors, essentially ending the story of the Bell & Howell I’ve been talking about for the past gazillion paragraphs.

To be fair, the company actually pulled in some of its most profitable years ever in the early 1980s, running vocational schools like the DeVry Institute and a successful micro-imagery division. By the end of that decade, though, all remaining support beams of the classic B&H infrastructure had been removed—including the 72-acre McCormick Blvd. headquarters, which was sold off in 1986 after the last vestiges of the B&H audio-visual department were dissolved.

You can still find the Bell+Howell name, passed through a series of owners in recent years, on random electronics like tac lights and desktop humidifiers. But the products share no legacy with the work of Don Bell and Albert Howell. Even the archives of the original company, supposedly merged 30 years ago into the storage cabinets at DeVry University, remain largely unaccounted for.

One day you’re the architect of the modern movie business, the next—your work is rotting away somewhere in the warehouse from Raiders of the Lost Ark. Such is life.

SOURCES

“Charles Percy, Former Ill. Senator, Is Dead at 91,” New York Times, Sept 17, 2011

“C.H. Percy, 29, Succeeds J.H. McNabb,” Chicago Tribune, Jan 13, 1949

“Joseph H. McNabb, Bell & Howell President, Dies,” Movie Makers, Feb 1949

“Albert Summers Howell Elected to Honorary Membership in A.S.C.,” American Cinematographer, August 1929

“The Story of Bell & Howell” by Earl Theisen, The International Photographer, October 1933

Bell & Howell Company: A 75 Year History, by Jack Fay Robinson, 1982

“Bell & Howell Company History,” FundingUniverse.com

“A Quarter Century of Leadership: 1907-1932,” Filmo Topics, April-May 1932

“Living in the Past,” by Wende Zomnir, Chicago Reader, Sept 29, 1994

Encyclopedia of American Biography, 1938

“Human Touch Still Valuable in Making 5,000 Lenses Monthly at Plant,” Chicago Tribune, Feb 29, 1948

Archived Reader Comments:

“Tell more on how the US Military photography and film divisions relied heavily  on and used B&H camera gear to document and help finance the war using the films produced to support the war bond efforts.” —Ross Rowlinson, 2019

on and used B&H camera gear to document and help finance the war using the films produced to support the war bond efforts.” —Ross Rowlinson, 2019

“I have a theory, it certainly will seem strange to say the least, namely that someone else was the inventor of the Bell & Howell Standard Cinematograph Camera, of the Bell & Howell film perforator, and other things. Albert Howell was more or less urged into partnership and from then on pressed or shall I say blackmailed to give his name for things to come. The threat was to dissolve the company, should he not obey, which would have ruined him forever. Of the registered $5,000 only $4,500 were payed, $500 must have been held by an unknown party. Check with the Cooke County commercial record.

The party or person I presume to be in the game is Louis Augustin Le Prince, born August 28, 1841. He had an intermittently working twin-lens camera already in 1888, made by English craftsmen for him. A U. S. citizen since 1882 he lived in New York City and Leeds, England, and Paris, France. In 1896 a stranger had parts of a Lumière cinématograph duplicated at a machine shop of Chicago, a man of about 55 years of age as was reported. That would perfectly fit. He was also reported as speaking English with a thick accent, French most probably.

Le Prince vanished September, 1890 in France. I imagine he had travelled to America, lived incognito somewhere around or in Chicago, and fed his life work into the young company. Howell simply cannot have conceived so many brilliantly designed things in the pace the world was made to believe, not alone. The Black Box twin-lens camera in 1909, the perforator in 1910, the Standard camera in 1911, the continuous printer in 1911, and more. The camera was not sold before 1912 because its shuttle forwarding cam would have infringed with the Lumière patent of 1895. U. S. patents run for 17 years at that time. Same goes with the perforator which by principle was a copy of the English Williamson perforator, patented in 1899. There are no patents to the Bell & Howell Co. on a perforator before 1917.

Bell & Howell was a true patent exploit. A lot of things that were invented by employees of the company served for license agreements with other manufacturers worldwide. Most amateur movie cameras made by American and European entrepreneurs actually came to life at the engineering laboratory of B. & H. on North Rockwell Street, opened September 1929. To name some, we have the Ciné-Ansco (1929), the Irwin and the Moveo (1930), the Vitascope Movie Maker (1931), the Zeiss-Ikon Movikon 16 (1932), the Paillard-Bolex H-16 (1935), the Facine (1935). I believe that even the ARRIFLEX (1937) and the WWII CINEFLEX stem from Bell & Howell engineers.

The story we were told that Martin and Osa Johnson lost a wooden Bell & Howell camera to termites and mildew in Africa is not true. The background of the first all-metal ciné camera implies so much more than just furnishing a new apparatus. The casting alone, sand casting of a special aluminum alloy, must have taken months and months of trial and error at a foundry. The Johnsons, by the way, have not come near Africa before 1920.” —Simons Wyss, 2017

“I suggest that the above ‘facts’ about LePrince should be substantiated by citations where evidence may be found to support these allegations/theories, i.e., public documents, records, publications, ex-partestatements, oaths, etc. Otherwise, it is all B.S.  ” —Graham Reece, 2017

” —Graham Reece, 2017

Attempting to find the manufacturing date on a Bell & Howell Filmo Automatic Cine Projector with what I believe is the Serial #28639.

Any assistance would be appreciated.

Thanks

I’d like to add that Bell and Howell is alive and well and living in North Carolina. As the film segment faded our mail processing business grew. As recently as the 2000s-2010s we maintained manufacturing plants in Wheeling, IL., Allentown, PA and Durham, NC.

The company was subsequently divided into two parts. One of those two parts became ProQuest and took the licensing rights to the BH name with them. I believe the rights have passed through several other owners since then which is why you see so many BH-branded consumer products.

But Bell and Howell is still here and still making machines!

Hello,

I would like to know the launching year of my father’s camera Bell & Howell 8mm Optronic 418 auto load

Thank you,

Best regards

B. Houel

We was gifts a wood box with an older Bell&Howell commercial projector 16 mm 1000 watt… We have no idea it’s history and or worth. Can anyone help?!

In the mid-1960s I repaired high speed feeders-collators for Phillipsburgh a division of Bell & Howell. Our office was located at 160 East Ohio Street in Chicago. Harry Blesy

My Unique Bell Howell 12″ speaker. I2F873 and IC337 on the magnet tag. . 1,957,562 newest patent date. On the frame or “basket” is print stamped number : k278c and SPEC.I D 1290. It has a pair of flat head screw terminals for +/- and the magnet is a gigantic round silver can line shape. Heaviest speaker in my 40 years of audio experience. Just massive. The come is extremely smooth with no real ribs for any surround. It works well and has bass like I’ve never heard before out of a old speaker. Hits harder than a modern speaker. Very impressed. But in 4 years seen only 1 other like it on Reverb website. For sale for 250.00. I’m guessing was being sold for guitar amplifier adaption. But what do I really have? Why so few out there? Is it unique? Special order? Help

It is great to have found your site,

I use the FILMO 1000 Watt 115v 25 hour base down projector lamps for my Bell and Howell FILMO 130 projectors.

Can you tell me what the Kelvin temperature of this lamp is?

Also if the lamp is dimmed, say by 50%, what does the Kelvin temperature shift to?

Thank you,

Marc

Manufactured year for Bell & Howell autoload movie projector for Super 8 & Regular 8 Model 456?

Hello, I am hoping I may be able to get information on an item my family gave me years ago. It is a wooden screen (silver) inside you spin to watch movies. It has the Bell and Howell plate but also the “Bub” North movie screen plate. It has legs to set upon a table. The only information in regards to age was an advertisement for The Bub north movie screen dating 1930. Thank you

I have a Bell & Howell film camera BJ 2804 and I can’t find it anywhere in your archives. Is this camera really old or is it newer. I could not find it anywhere, could you please tell me where I could find information and how much it is worth.

I have a 1928 bell and howell projector that I was able to identify fairly easy but also have another piece that I can’t find anywhere the center of this looks very similar to A microscope with rods on both sides about 3″ long give or take and looks like film holders on the end with hand crank nobs if you understand any of this can you let me know anything about it

Tengo un proyector igualito que deseo vender Bell&Howell Co filmó sound

Hi there my name Martha croy I live in Dalton ga. I have old Belle Howell movie ejector look like all of its there don’t no how use it. It was my brother died recently but I was wondering do people buys these any more ? If so I like try sale it done got rid lot stuff but I haven’t seen one like this ok. I look but it’s one the old one it’s heavy two ok. Serial number is 4488 model 245 Ac 50/60 Chicago ill45 auto load 300 w max it’s got light switch on it heavy Grey the lens goes out ward on it. If you got any information let me no 7062182182 Martha croy Dalton ga marthacroy103@gmail.com let me no I’m curious I haven’t seen nothing yet but I guess it’s old . But looks good shape to me got reel to . So if one concern call or something thanks martha croy Dalton Ga

My father, Robert Klein, was a former Bell and Howell engineer in 60’s-80’s and he has some artifacts to donate. How would he go about doing so? He has a framed photo of Mr. Bell, a cassette and stereo turntable, as well as some engineering drawing from his early days. If there is any interest, please feel free to contact me.

Thank you.

Hi, Kathryn, thanks for your message. You or your father are welcome to e-mail us at contact@madeinchicagomuseum.com. There, you can include photos of the some of the items and we can discuss options. We hope to be launching a new physical exhibit soon, so that could affect how donations work.

Is there a schematic or other information displaying the internal design of the winding key for a B&H 16 mm magazine camera 200. I am trying to make a minor repair where four small pins have been displaced and I am trying to understand where they are placed within the winding key mechanism.

I came across a Bell & Howell late 1950s HI-FI console series 866-J .It is a AM FM Phonograph reel to reel console Seems to be rare.Do you have any information on this?

I live in NJ and have a Filmosound and i don`t want to discard it. What or where do I do with it.

If you want to sell it, reply to this post!!

Also which model number is it?

Thanks

Caan

Is there a list of projectors and cameras made over the years. Did find at list for the 16mm but nothing for the 8mm.

I have a Bell & Howell Autoload film projector, Design 467A, Serial #1067109 and need the instruction manual. Does anyone have a copy they can share or know of where I can get one on line without charge.

I have a B&H 1744z Filmosonic projector. It used to work great, but now the sound is out! does anyone know who can fix it?

Great write-up! I’m amazed at the quality of the B&H projectors I have owned, the superb engineering and materials quality is as good, or better, than the best Swiss and German equipment I’ve seen, though B&H peaked earlier.

I’m confused about your timeline for when B&H appeared to cease manufacturing projectors. The copy implies that Donald Frey took over B&H and stopped manufacturing projectors and cameras in 1971 – but I think that’s much earlier than actually occurred. I think B&H was still dominating 16mm institutional movie projectors until the 1980’s – I have a Model 1580 16mm projector which is dated 1979. My guess is that they continued making 16mm projectors until film was ground into the earth in the early or mid-1980s.

I found a Bell and Howell Telesonic 947 at an auction. I’m trying to get more information about it, but finding it difficult. Any information is appreciated.

Enjoyed the article very much. I was a camera collector for years focusing mostly on cameras made in Chicago and own 40-50 B&H cameras and accessories, including about 12 models of Filmo 16 mm. cameras including all 3 models of their 128 fpm only models. I’m no longer collecting very actively but have most of the collection. I remember once seeing Charlie Percy when he was on the Board of Directors of the University of Chicago.

I have a bell and Howell 8 mmm projector in the original box it is about 60 years old still working are you interested

Bell & Howell have a range of excellent product that give value of many years of use. I have invested my money in many of their products like still cameras, 8 mm and 16 mm movie cameras. I have also one 16 mm filmosound projection set. The quality of their products is unmatched.