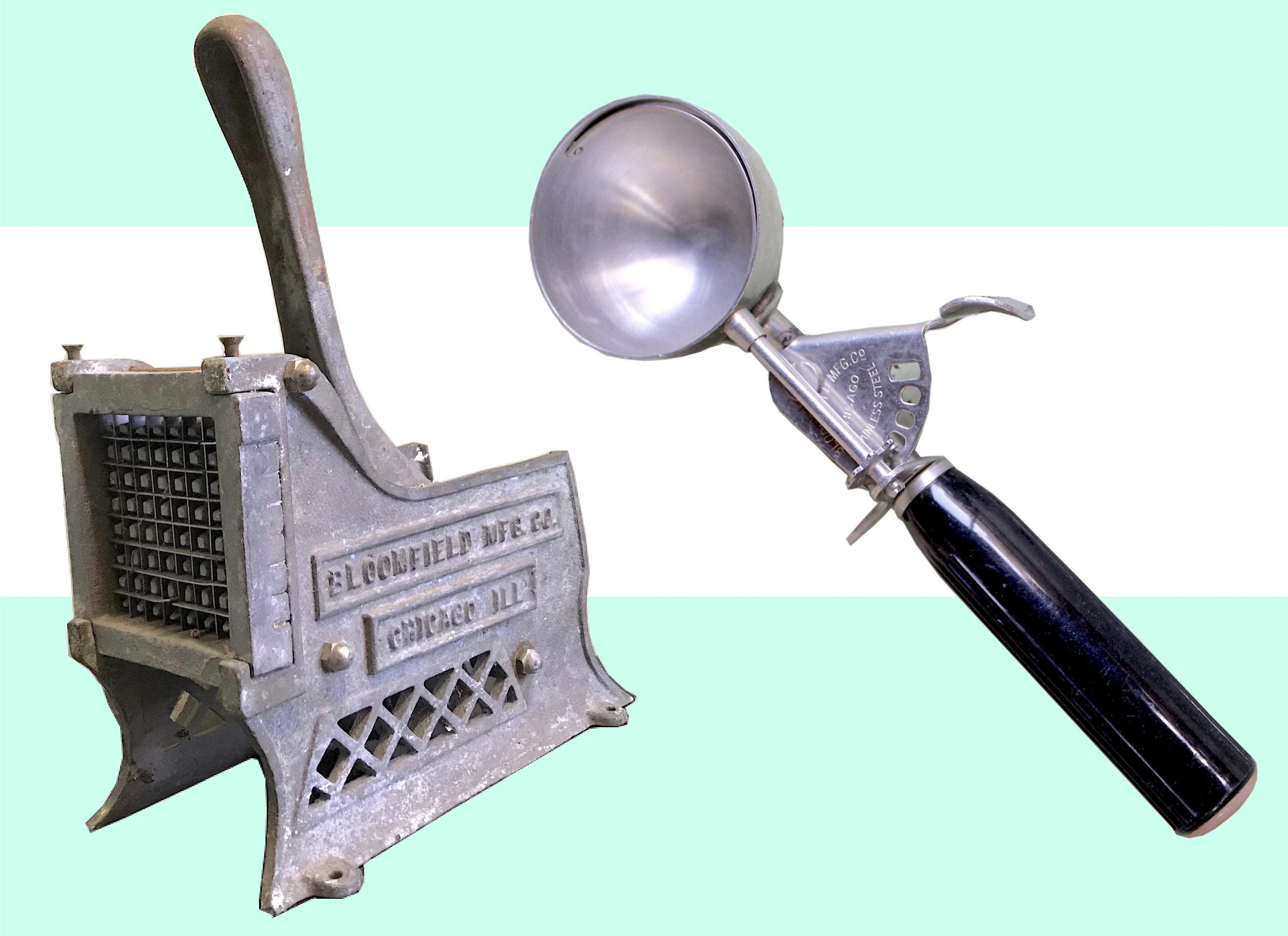

Museum Artifacts: Cast Iron Fry Cutter (1930s) & Stainless Steel Ice Cream Scoop, (1960s)

Made By: Bloomfield MFG Co. / Bloomfield Industries, 3333 S. Wells St. [Armour Square] and 4546 W. 47th St. [Archer Heights]

Some men have lived and learned through living

Some men have learned by seein’ true

You cannot judge from what they’re sayin’

It’s real clear from what they do

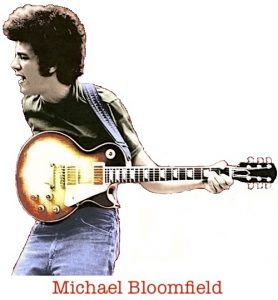

—lyrics by Michael Bloomfield from the song “Good Old Guy,” 1968

The Bloomfields, one could argue, were the quintessential 20th century Chicago family. Patriarch Samuel Bloomfield (1887-1954), a Jewish immigrant from Russia, started a successful kitchen tool manufacturing business in the city during the roughest years of the Great Depression. His sons, Harold and Daniel, nurtured that small-time operation into a giant of the food-services industry. Harold’s wife Dottie, for good measure, was a stage actress and graduate of the Goodman Theatre, and their son Michael—while not much interested in the family business—is remembered today as one of the greatest blues-rock guitarists of all time.

Short of playing for the Bears or inventing deep dish pizza, these people just about did it all.

Short of playing for the Bears or inventing deep dish pizza, these people just about did it all.

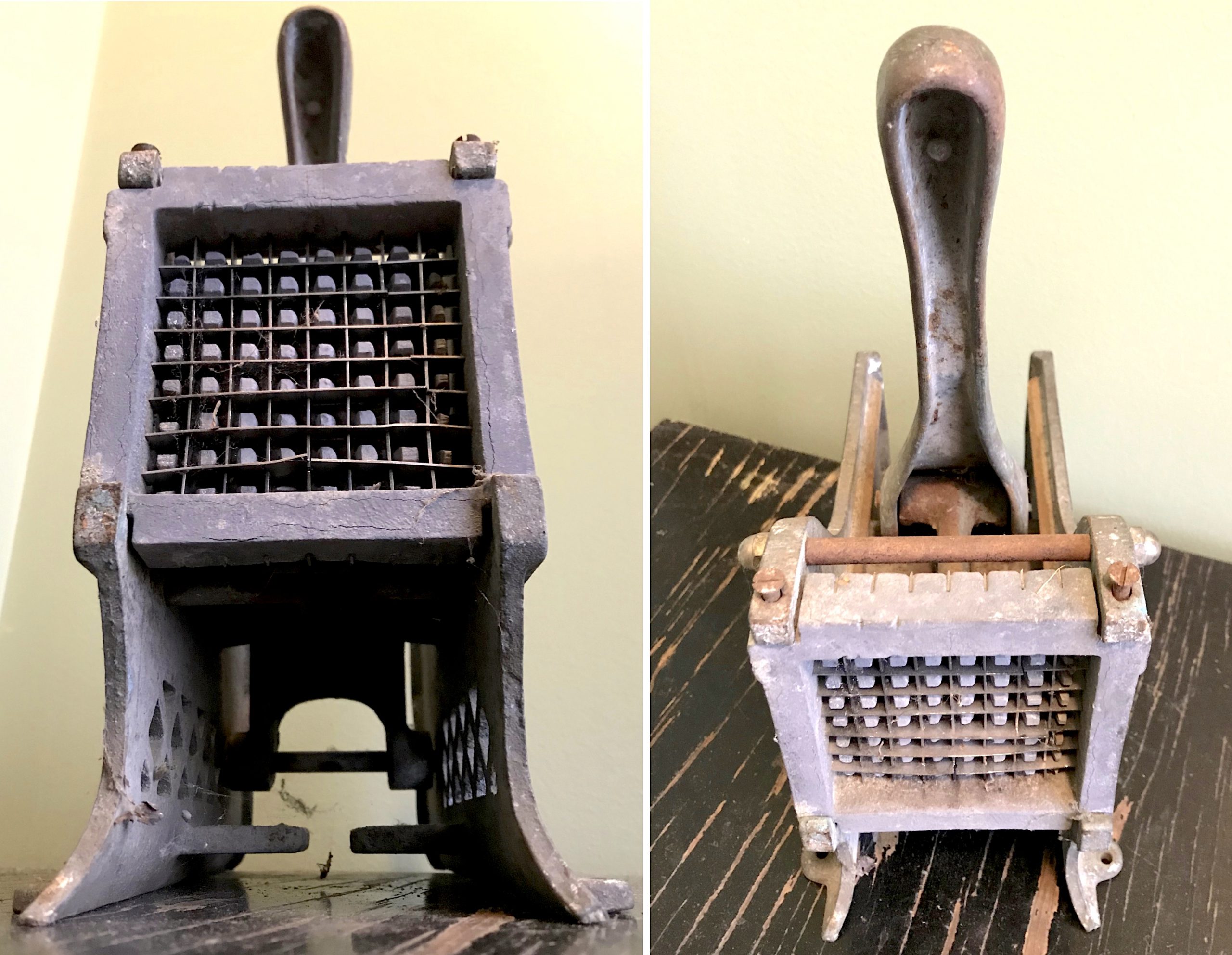

The two Bloomfield artifacts in our museum collection (pictured at the top of the page) won’t be migrating to the Rock n’ Roll Hall of Fame anytime soon, but they do provide a nice “Before & After” study in how the products of Bloomfield Industries evolved from one generation to the next. The lever-operated potato fry cutter on the left was a hand-forged, cast-iron beast of the 1930s, measuring about 10″ x 10″ and weighing close to 15 pounds. The featherweight, stainless steel ice cream scoop on the right, by contrast, screams streamlined post-war modernization and mass production.

By the early 1960s, when our particular ice cream scoop likely rolled off the assembly line, Bloomfield had become a juggernaut at the forefront of American food-service accoutrement—combining the old business model of the Albert Pick Company with the more colorful and cost-efficient methods of the Ekco Products Co.

From a massive six-acre headquarters in Archer Heights, Bloomfield Industries made the fundamental hardware that every self-respecting, professional eating establishment relied upon—be it pancake house or steakhouse; hotel bar or hospital cafeteria. There were Bloomfield salt shakers, sugar bowls, can openers, coffee pots . . . various utensils of every shape and size—most of which now utilized that illustrious new king of the kitchen alloys, stainless steel. By some counts, Bloomfield had more than 1,000 different products to offer at its peak; quite a leap for a business that started out selling nothing but display cases . . . for pies.

[Still from a 1965 Bloomfield Industries promotional film, with a view of the 47th Street plant]

[Still from a 1965 Bloomfield Industries promotional film, with a view of the 47th Street plant]

Bloomfield Industries History, Part 1: Difficult as Pie

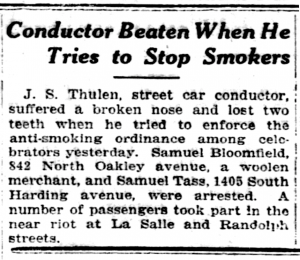

The first mention of Samuel Bloomfield in the pages of the Chicago Tribune comes on November 12, 1918, the day after Armistice Day. While sharing in end-of-the-war revelry with celebrators near LaSalle and Randolph, Sam had apparently gotten into a squabble with a street car operator who was trying to enforce an anti-smoking ordinance. Allegedly, Bloomfield punched the fella, and the cops arrested him and another overzealous smoker for the offense. It sounds like a fairly forgivable crime for a teenager in the midst of a joyous riot. Bloomfield, unfortunately, was 31 years old and a father of two.

Such quick turns from fun to failure kind of epitomized much of Sam’s early life, as his undeniable talents as an entrepreneur brought him several cash windfalls, which were then repeatedly squandered by unfortunate twists of fate.

“He was the vulcanized-tire king at one time,” says his grandson Allen Bloomfield, who discusses Samuel in the recent oral history Michael Bloomfield: If You Love These Blues. “After that, he put all his money into real estate in Florida, but the stock market crashed, and he lost it all. Then he got it back together, got some money, and opened his own sporting-goods shops in Los Angeles. He owned 40 sporting-goods shops [claim unsubstantiated] before the earthquake came [in 1933] and wiped him out completely.”

Having now crashed out of the automotive and retail sports markets, Bloomfield returned to Chicago in ’33 with no known prospects outside of a seemingly unflappable will to succeed. Within weeks, he’d already found his brand new inspiration.

“He saw a pie case in a diner,” Allen said. “It had zinc-cast uprights that attached to the bottom of the counter. The case’s rear-hinged door would open so that you could slide in the pies, and they were clearly visible so anyone drinking their coffee could see it and buy one. [Sam] saw the money in that, so he got the guy who made the case to sell him the patent. He then got one of his sons [Harold] to manufacture it and the other [Daniel] to sell it.”

“He saw a pie case in a diner,” Allen said. “It had zinc-cast uprights that attached to the bottom of the counter. The case’s rear-hinged door would open so that you could slide in the pies, and they were clearly visible so anyone drinking their coffee could see it and buy one. [Sam] saw the money in that, so he got the guy who made the case to sell him the patent. He then got one of his sons [Harold] to manufacture it and the other [Daniel] to sell it.”

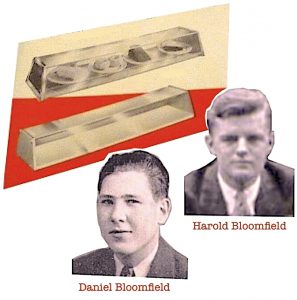

Daniel Bloomfield (1912-1990) and Harold Bloomfield (1914-1992) were only 21 and 19 respectively when Samuel organized the Bloomfield Manufacturing Company in 1933, backed by just $900 in capital and one solitary product: the legendary pie case. But the sons had been raised in their father’s mold—business oriented, focused—and after earning their degrees from the University of Illinois, they quickly set to work helping Sam expand the inventory.

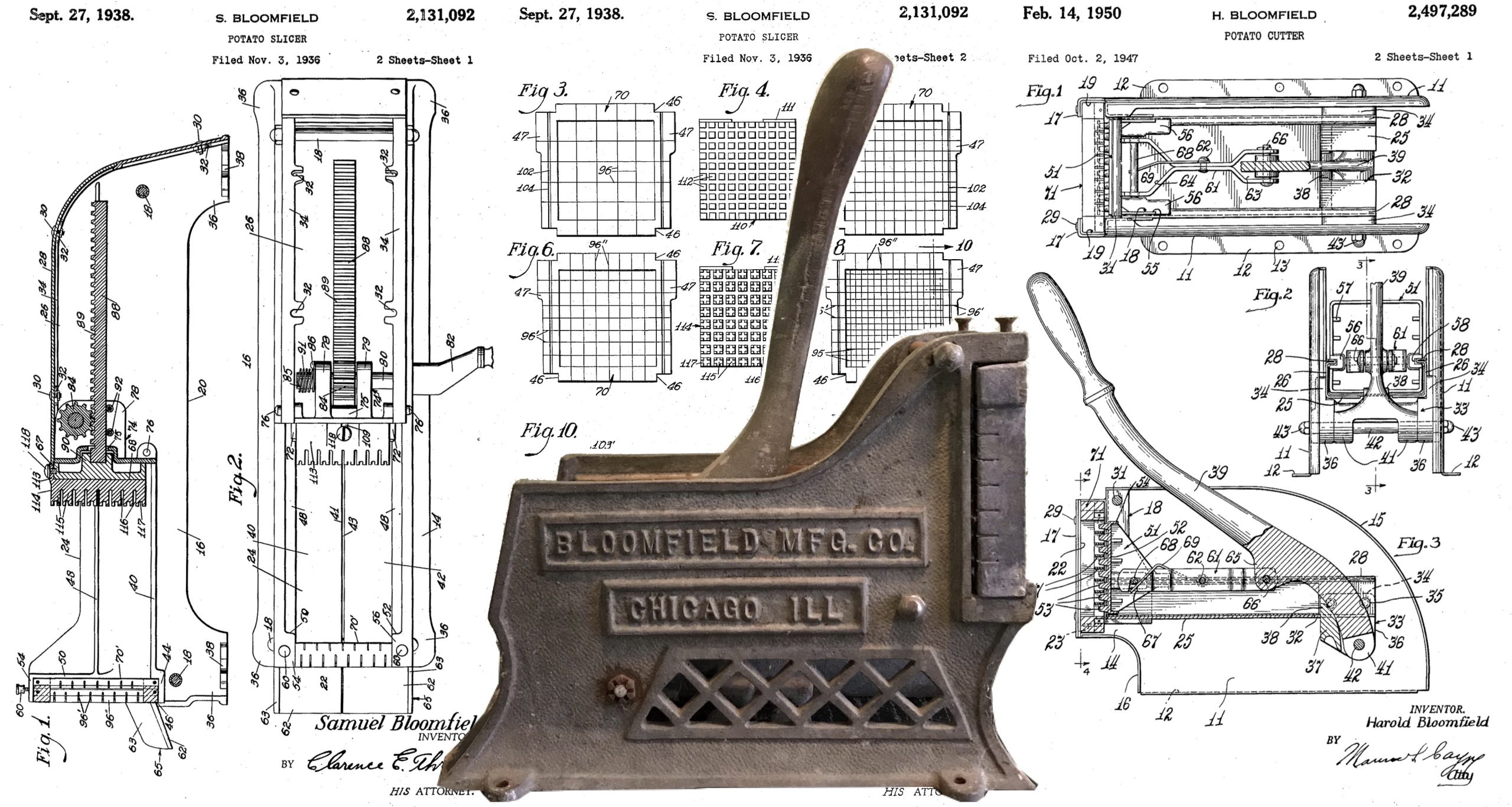

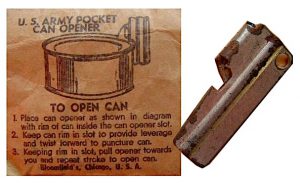

Within a few years, the company was producing napkin dispensers, straw holders, sugar dispensers, egg slicers, spoons and ladles, and service trays, while Sam Bloomfield also collected his own original patents on several more items, including a bottle cap, butter cutter, can opener, fruit press, and of course, the iconic Bloomfield “potato slicer,” U.S. patent 2,131,092. Years later, in 1950, son Harold would patent his own update of the tater chopper, patent number 2,497,289.

[Left and Center: Samuel Bloomfield’s 1938 patent for a “Potato Slicer.” Right: Harold Bloomfield’s 1950 update]

[Left and Center: Samuel Bloomfield’s 1938 patent for a “Potato Slicer.” Right: Harold Bloomfield’s 1950 update]

II. In Bloom

Moving into a 25,000 sq. ft. plant at 3333 S. Wells Street, a short stroll from Comiskey Park, the Bloomfield Manufacturing Company was able to employ a team of about 40 workers by the time they received their corporate charter in 1939.

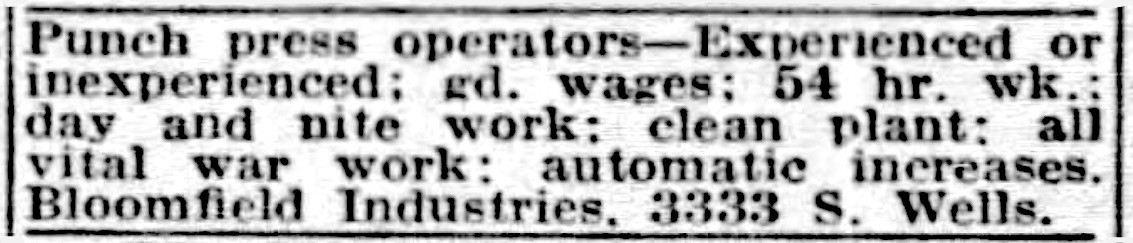

Two years later, of course, many of those employees were off to war, and the Bloomfield plant was thoroughly repurposed to help equip them. As newly minted military contractors, Sam, Harold and Daniel did their best to restaff the factory and shift production from pie cases to slightly more serious accessories like oxygen masks and bomb hoists. As an easier adaptation, Bloomfield also produced many of the critical K-ration can openers used by American servicemen overseas.

While government contracts were a boost to the newly renamed Bloomfield Industries, an eagerness to get back into the diner supply market also got the company into some trouble with Uncle Sam in the summer of 1944. That’s when the War Production Board accused the Bloomfields of “violating preference rating regulations,” and imposed a 90-day suspension forbidding the company from using any of its surplus sheet metal for non-war production (namely, kitchen utensils).

There were hiccups when it came to the workforce, too. Back in 1940, the National Labor Relations Board had ruled that Sam, Harold and Daniel engaged in unfair labor practices by “refusing to bargain collectively” with union workers in the Wells Street plant. One of those union men testified that Harold Bloomfield told him directly, “I won’t agree to bargain with any committee, and I will not recognize no union . . . If you want to leave your union cards outside of the shop, I will put you back to work.”

[Above: Inside the Bloomfield plant, 1940s. Below: Advertisement seeking punch press operators for “vital war work” at the Well Street plant, 1944]

Five years later, just months after the end of WWII, many of Bloomfield’s returning workers (about 80 out of a 100-person workforce) went on a prolonged strike of their own after the company “failed to negotiate a new contract.”

It’s hard to say if the Bloomfields softened to union workers in the years that followed. What they did do was purchase a new 100,000 sq. ft. factory, with plenty of real estate for expansion, at 4546 W. 47th Street. When it opened in 1951, the building had all the modern amenities to drastically ramp up production while also giving employees a pleasant, efficient, temperature controlled working environment.

[Former Bloomfield plant at 4546 W. 47th Street, 1965 vs. 2019]

[Former Bloomfield plant at 4546 W. 47th Street, 1965 vs. 2019]

Daniel Bloomfield’s daughter, Nancy Pemberton, recently told the Made In Chicago Museum about her memories of visiting the factory as a child. “To me, as a little girl, it was a very big place,” she says. “I saw the way the machines created huge stockpots. I sat in the office section with the secretaries and did a little filing and sorting. I remember the old plug board (switchboard) and its operator. I could not figure out how she used those wires to connect people.

“There were so many employees both on the factory side and in the office. I’m proud that they created enduring products and that the company provided so many jobs.”

After Samuel Bloomfield’s death in 1954, the company increasingly reflected the talents of his two sons, as Harold ran all elements of the rapidly growing plant, and Daniel masterminded sales.

“My memories are of a father who worked very hard for 45 years, getting up early and coming home late,” Nancy Pemberton says of Daniel Bloomfield. “My dad was a consummate salesman who had a charismatic personality, great sense of humor and a good heart.”

As company president, Daniel Bloomfield also recognized the value of good design and style, even when it came to seemingly utilitarian goods. “People don’t eat with their stomach—they eat with their eyes,” he told the Tribune in 1962. “Any piece of equipment the customer sees in a restaurant should please the eye, particularly the feminine eye.”

Taking this philosophy a step further, Bloomfield Industries gradually started making moves into the consumer market, as the familiar plastic ketchup dispensers and stainless steel salt shakers it made for restaurants became available in department stores, targeted toward everyday housewives.

By 1962, the company had achieved record sales numbers for five years running, and was now a publicly traded entity with four divisions of production: Bloomfield (food service equipment), Hosp-I-Ware (hospital supplies), Bi-Cor (housewares), and the recently acquired Silex (coffee making equipment).

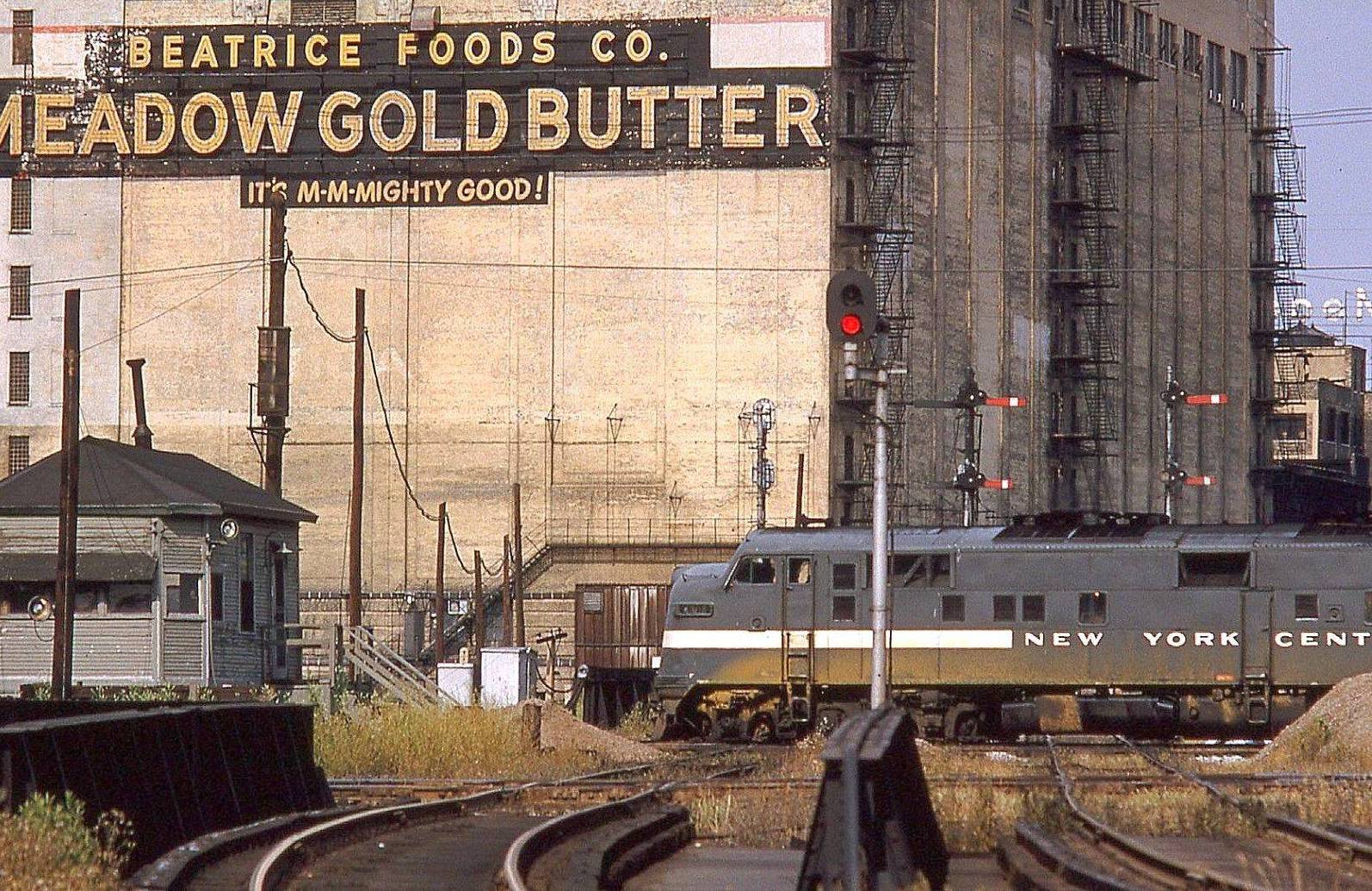

While bulking up on all those smaller fish, however, Bloomfield had caught the eye of an even bigger fish than itself, and in 1964, at the height of its success, the company was sold to Chicago’s Beatrice Foods. Best known as a dairy company (Meadow Gold Butter), Beatrice was slowly turning into a super-conglomerate, and Bloomfield would help them expand outside of foods into food equipment.

[New York Central Line passing through Chicago in 1965, with a massive Beatrice Foods – Meadow Gold Butter sign in the background]

[New York Central Line passing through Chicago in 1965, with a massive Beatrice Foods – Meadow Gold Butter sign in the background]

III. Keys to the Kitchen

Shortly after acquiring Bloomfield Industries, the promotional team at Beatrice Foods put together a wee industrial film to show off its shiny new toys. Titled “Bloomfield Industries: Keys to the Kitchen,” the 5-minute film—captured in its entirety below—provides a pretty good snapshot of a company reaching behemoth status in the Mad Men age.

“Since 1935, Bloomfield has been in the business of manufacturing keys to the kitchen—equipment for storing, preparing, mixing, and the carriage of food,” the narrator says, adding that Bloomfield’s popular Swedish Regent line offered “superb table service—every item fit for a king and queen.”

Bloomfield Industries: Keys to the Kitchen (1965 Promotional Film)

The film also touts Bloomfield’s equipment “for the modern soda fountain—perfect service for Meadow Gold ice cream, of course.” Meadow Gold, as you might have guessed, was one of the kajillion other brands owned by Beatrice.

Towards the end of the clip, we can actually see an assembly line with stainless steel ice cream scoops rolling down the conveyor. Who knows, this might be exclusive footage of the actual birth of the very same “ice cream disher” from our museum collection.

“Bloomfield produces only essentials, no novelties. But each is distinguished by dignified styling and quality. . . . Only the finest non-magnetic stainless steel with the highest corrosion resistance is used.”

“Bloomfield produces only essentials, no novelties. But each is distinguished by dignified styling and quality. . . . Only the finest non-magnetic stainless steel with the highest corrosion resistance is used.”

“The Bloomfield trademark stands for the highest quality.”

Bloomfield had 90 men and 40 women on the regular staff in 1963, according to the Chicago, Cook County and Illinois Industrial Directory of that year—but with all of its related subsidiaries added to the equation, that total was likely much higher. As “Keys to the Kitchen” shows, the workforce was also quite diverse in terms of both gender and race.

Still, come the mid 1960s, the company’s most famous “employee” was probably the guy who quit before he ever started . . .

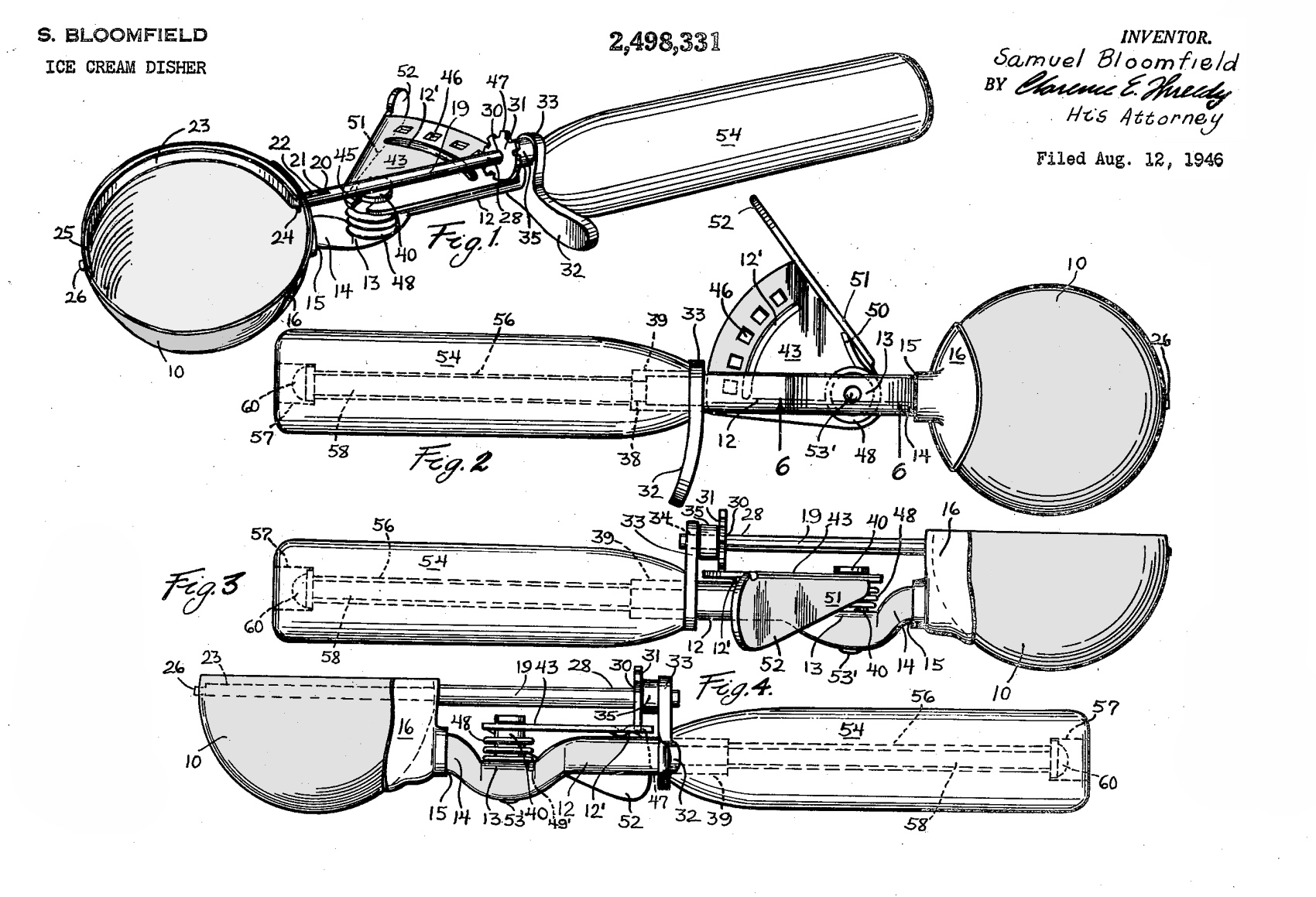

[Samuel Bloomfield’s original Ice Cream Disher patent from 1946, which was refined, with few functional changes, through the ’60s]

[Samuel Bloomfield’s original Ice Cream Disher patent from 1946, which was refined, with few functional changes, through the ’60s]

IV. Fathers & Sons

Michael Bloomfield (1943-1981), grandson of Samuel and eldest son of Harold, never followed in their footsteps. Born with a silver spoon in the golden age of American kitchenwares, he certainly could have elected to carry on that lucrative mantle, literally selling silver spoons en masse to the food-service industry. But the awkward Jewish kid from Lakeview had very different ideas. Mike Bloomfield was going to be a guitar god—even before he or anyone else knew what that meant.

After his family moved from a lakefront apartment in the city to quaint suburban Glencoe in the late ‘50s, teenage Mike turned to the ax in rebellion—first joining a troublemaking high school rock band at 14, then leaving his cushy upper-class house each night to go jam at rough-and-tumble blues clubs on the South Side. A natural lefty, Bloomfield even learned to play guitar right-handed to more accurately emulate his idols—a fairly ridiculous accomplishment that makes you wonder how good a southpaw version of the man might have been.

By 18, he was using the last of his allowance money to take more of a managerial role in the blues scene, booking gigs for a club called the Fickle Pickle. Mike might have been channeling his father’s business acumen without realizing it.

“I was managing this club,” he recalled in a 1968 Rolling Stone interview, “and every Tuesday night I’d try seriously to have concerts with Muddy Waters and Sleepy John Estes—all the blues singers in Chicago that I could get hold of, that I’d ever met, I tried to get—especially the rare cats.”

Michael’s dad, the strait-laced factory superintendent in a three-piece suit, was decidedly not one of those “cats.” On some level, he knew his son was talented, but—in a dynamic familiar to many 1960s homes—he was almost perpetually and unavoidably at odds with the boy. It didn’t help that Mike eventually dropped out (or possibly was kicked out) of the hoity-toity New Trier High School.

[Meet the Bloomfields: Dorothy, Allen (standing), Michael, and Harold, circa 1955. Notice Harold’s judgy expression when observing his older son.]

[Meet the Bloomfields: Dorothy, Allen (standing), Michael, and Harold, circa 1955. Notice Harold’s judgy expression when observing his older son.]

“[My father] wanted me to be everything that I wasn’t,” Mike later said. “He wanted me to be a jock, he wanted me to be a good student, he wanted me to be this and that. He just couldn’t understand.”

No kid ever thinks their parents “understand,” of course, but Harold Bloomfield had actually gone through a few of his own blues-worthy struggles in life—which may have contributed to the high expectations he placed on his own children, and possibly even his employees.

At the age of 23, shortly after the Bloomfield MFG Co. was formed, Harold was driving in a rainstorm at Lakeshore and Fullerton, near his family’s home at 426 W. Surf Street. Suddenly, he skidded and hit a man who’d stepped out of his own car to pick-up a fallen wiper blade. The man was killed, and Harold—though not legally held responsible—was likely changed by the experience.

Two years later, in 1940, Harold married his wife Dorothy in a lavish ceremony at the Edgewater Beach Hotel. Dorothy, aka “Dottie,” had trained at Chicago’s famous Goodman Theatre alongside future Hollywood stars Karl Malden, Geraldine Page, and Sam Wannemaker, and while she gave up her thespian aspirations to start a family, she remained a voice of encouragement for the artistic pursuits of her sons.

By contrast, when Michael Bloomfield was born in 1943, his dad Harold—still just 29 years old at the time—was already managing a wartime factory, and his interests were entirely business oriented. He would never develop any patience for a son with a different work ethic to his own.

“[Our father] was a quiet guy in his demeanor,” Mike’s younger brother Allen said years later. “He was not a loud guy. If he said something, he meant what he said, and you could be sure that if there was any sense of threat to it, he would fulfill it. . . . Dad could be very physical with Michael when he provoked him. Michael had an acid wit and a highly acerbic tongue. And he could really provoke! . . . Of course, he was always trying to get Dad’s approval, and he never really did. I don’t think Mike ever made it through one family meal without being sent away from the table.

“They had good moments, though. I remember my father sitting in my parents’ big bedroom, and Michael was sitting across the way playing guitar. He’d brought his amp in and was playing all these show tunes, like from the ‘Hit Parade’ – just a kid playing for his pop. Dad knew that Michael had real talent, and later even went to see him perform a few times.”

There would be no happy ending for the Bloomfield family, however. By the early ’60s, Harold and Dottie were separated, and Harold had started a new life with a company secretary. Afterward, his younger son Allen still joined the family business, but Michael’s rebellion was irreversible.

[Mike Bloomfield jamming with B.B. King, late 1960s]

[Mike Bloomfield jamming with B.B. King, late 1960s]

V. “A Chicago Thing”

Along with Paul Butterfield and a few others, Michael Bloomfield was part of a new wave of young white musicians in Chicago trying to turn their admiration for black music into an artistic partnership—but he knew a mutual respect had to be earned.

“You had to be as good as Otis Rush,” Bloomfield said. “You had to be as good as Buddy Guy, as good as Freddie King. Whatever instrument you played at that time, you had to be as good as they were. And who wanted to be bad on the South Side? Man, you were exposed all over. I mean right in that city where you lived, in one night, you could hear Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Buddy Guy, Otis Rush, Big Walter, Little Walter, Junior Wells, Lloyd Jones, just dozens of different blues singers—some famous, some not so famous. They were all part of the blues, and you could work with them if you were good enough. If you wanted to gig, that’s where you went and that’s where you worked.

“All these cats, man, these white kids in Boston—like Geoff Muldaur was playing the blues, and in New York Bob Dylan and his cats were playing their thing of the blues. But in Chicago they were playing the real blues, because that’s where they were working—they were working with the cats.”

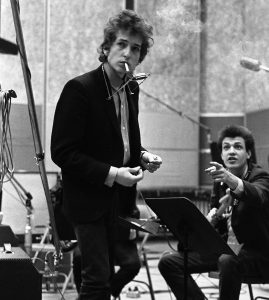

In the summer of 1965—around the same time Beatrice Foods was showing off the Bloomfield factory in “Keys to the Kitchen”—Michael was in a Columbia recording studio in New York City with the aforementioned “cat” Bob Dylan, playing lead guitar on a major career-pivot of a record called “Like a Rolling Stone.” Dylan, a scruffy Jewish boy himself, had met Mike at a Chicago blues club called the Bear, and quickly recruited him to be his new axman. [Photo Below: Bloomfield pointing the finger at Dylan in 1965]

“Suddenly Dylan exploded through the doorway with this bizarre-looking guy carrying a Fender Telecaster guitar without a case,” writes Al Kooper in his memoir Backstage Passes and Backstabbing Bastards [Kooper played the Hammond organ on “Like a Rolling Stone” and eventually became a longtime friend of Bloomfield]. “It was weird, because it was storming outside and the guitar was all wet from the rain. But the guy just shuffled over into the corner, wiped it off with a rag, plugged in, and commenced to play some of the most incredible guitar I’d ever heard. And he was just warming up! . . . I wanted to know the identity of the dragonslayer, so I asked Tom [Wilson] who the guitar player was. ‘Oh, some friend of Dylan’s from Chicago, named Mike Bloomfield. I never heard of him but Bloomfield says he can play the tunes, and Dylan says he’s the best.’ That’s how I was introduced to the man.”

According to Kooper, Michael didn’t see anything unusual about a Jewish guy playing blues guitar, explaining it like this: “It’s natural. Black people suffer externally in this country. Jewish people suffer internally. The suffering’s the mutual fulcrum for the blues.”

“Michael never saw black and white in contexts like that,” Kooper added. “People were people. It was a Chicago thing. It was a good thing.”

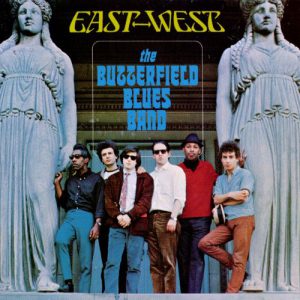

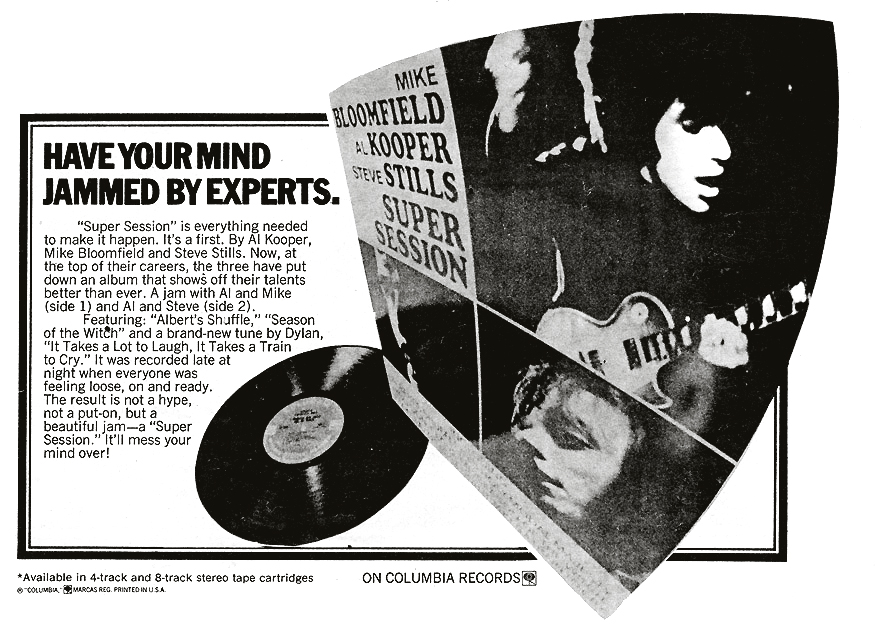

Besides playing with Dylan, Bloomfield was a member of the seminal Chicago outfit known as the Butterfield Blues Band (one of the 1960s first real multi-racial rock bands), as well as his own experimental supergroup, the Electric Flag. He also joined with Kooper and Stephen Stills in 1968 for a classic LP called Super Session. These projects were well regarded by the critics but somewhat under the radar commercially, and Mike spent much of the ‘60s living the tortured artist’s life in borderline squalor rather than asking for a chunk of the family fortune.

VI. End of the Line

Back in Chicago, the Bloomfield plant on 47th Street remained in operation throughout the 1970s, and Mike’s kid brother Allen continued to represent the firm as a salesman, working largely in New York. Manufacturing was gradually moving to Taiwan, however, and in the early ’80s, Bloomfield Industries and several other Beatrice affiliates were split off into a new entity—Specialty Equipment Companies, Inc. By 1993 (shortly after the deaths of Harold and Daniel Bloomfield), all Chicago production was discontinued.

The Bloomfield brand name has survived, however, under the banner of Wells-Bloomfield, LLC, a St. Louis based food service supply company. You can still find the name on some industrial strength kitchen products, including coffeemakers and decanters. If you want the potato slicers and ice cream scoops, though, you’ll have to check eBay.

As for the prodigal son Michael Bloomfield, he never returned, and never logged a day with the family business. In 1981, after years struggling with drug addiction, he was discovered in his car by San Francisco police, dead from an overdose. He was just 37, survived by his brother and both of his parents.

In the report of his death, the Tribune included this Bloomfield quote from a past interview: “Maybe there’s a few moments of ecstasy, but the price you pay for that is pure daily hell. And it’s true the moments of my greatest creativity came out of intense agony—when I’d been on the road for months, strung out, junk sick. . . . I know it’s not worth it. I have to find a balance in comfort and deal with art on a daily, human basis.”

Mike Bloomfield was not constructed from corrosion-resistant stainless steel. But his music, fortunately, has endured. And while he may have started out as a novelty act to some—a white boy playing the blues—in the end, like his dad’s company, he “produced only essentials.”

“There is no person on earth that I’d rather hang with than Michael,” his brother Allen added in a 2010 interview. “If you took J.D. Salinger and added a pinch of Bukowski, a dash of Terry Southern, and a sprinkle of Oscar Levant – you would have an approximation of what he was like. A wit like Lenny Bruce and the persona of a gangster with a rose tattoo. . . . The best gift for the future? That would be to preserve the memory of Michael as he truly was. Clearly, to know him was to love him.”

Postscript: There is currently a New York based, medical marijuana provider called Bloomfield Industries. And while Michael may have been more inclined to work for them than his dad, there is no affiliation between the two companies.

[The Electric Flag performs “Wine” at the Monterey Pop Festival, 1967]

SOURCES:

“Adaptability Asset to Bloomfield Firm” – Chicago Tribune, April 23, 1962

Michael Bloomfield – If You Love These Blues: An Oral History

Michael Bloomfield: The Rise and Fall of an American Guitar Hero, by Ed Ward

Guitar King: Michael Bloomfield’s Life in the Blues, by David Dann

Stars of David: Rock ‘n’ Roll’s Jewish Stories, by Scott R. Benarde

“Bloomfield’s Doomed Field” – Gadfly – March/April 2001

Decisions and Orders of the National Labor Relations Board, Volume 22, 1940

Jann Wenner interview with Mike Bloomfield, Rolling Stone, 1968

“Conductor Beaten When He Tries to Stop Smoker” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 12, 1918

“Steps From Car in Rain; Is Hit By Another; Killed” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 6, 1938

Backstage Passes and Backstabbing Bastards, by Al Kooper

I have a ladle marked US Bloomfield 1951 that I recently found. Is it something you might be interested in?

I have a French Fry cutter that’s missing the 3 “side-to-side” bolts (shoulder bolts???). Are these available anywhere?

The modern Vollrath fry cutter appears to be identical to the cast iron model of the Bloomfield cutter. You can get parts for the Vollrath cutter here: https://www.webstaurantstore.com/14243/french-fry-cutter-replacement-parts-and-accessories.html?vendor=Vollrath

While employed at Bloomfield Industries on 47th Street in the early 1970s I had purchased an ‘Ice Cream Disher’ through the front office with an employee discount as a gift for my wife. We still have it in 2021 and it’s in mint perfect condition just like brand new. So user friendly and scoops up ice cream so smoothly almost effortlessly – the highest quality for certain.

I am seconding Mark Lloyd’s comment, meaning, Mark Lloyd is accurate. The mention in the main article about valium is inaccurate.

Michael Bloomfield was killed by wrong-headed treatment for a heroin overdose. His dealer shot him up, first with cocaine, then methamphetamine. When nothing revived Mike, the dealer drove him, in Mike’s car, & parked space in an unpopulated area. Mike’s autopsy called it an overdose of stimulants. Mike NEVER took stimulants.

I recently purchased a Bloomfield Industries ice cream scoop like the one featured in this article at an antique store. It’s 2021 and it is in pristine shape and the mechanism is perfect. The quality of the item made me delve into just who made it. What a fascinating story! Thank you for this research. I’ll appreciate it even more after hearing the story behind it. Side note: my scoop has a black handle with a jade green cap on the end. I haven’t been able to find another like it.

I am looking for an item that we have used in our school kitchens for over 40 years. I am not sure what to call it? It is stainless steal. It is a handle that is used to pull steam table pans out of the hot/cold wells. The numbers on it are 18-8 S. S. U.S.A.

I can provide pictures if wanted.

Hello…I recently purchased a Bloomfield mtg. Co. cast iron Potato slicer..it has the heavy cast iron handle which when pushed forward slides to feed a potato thru the cutting blade grid on the front.

Trouble is…there was no pusher plate on this particular one. I bought it in an antique store near my home. I would like to inquire if the pusher plate that locks into the attached arm can be purchased anywhere? I know this slicer has been out of manufacture for many decades.. But…if you could steer me toward someplace I could obtain a matching push plate? I would greatly appreciate your feedback. I am loving this potato slicer French Fry maker! I want to use it in my kitchen. Please help me find the missing cast iron push plate. I checked many antique sites..but nobody had one for the slicer.

I will be awaiting your reply..

Thank You..

Coleen Compton

If you’re still looking for the fry cutter part, these look identical: https://www.webstaurantstore.com/14243/french-fry-cutter-replacement-parts-and-accessories.html?vendor=Vollrath