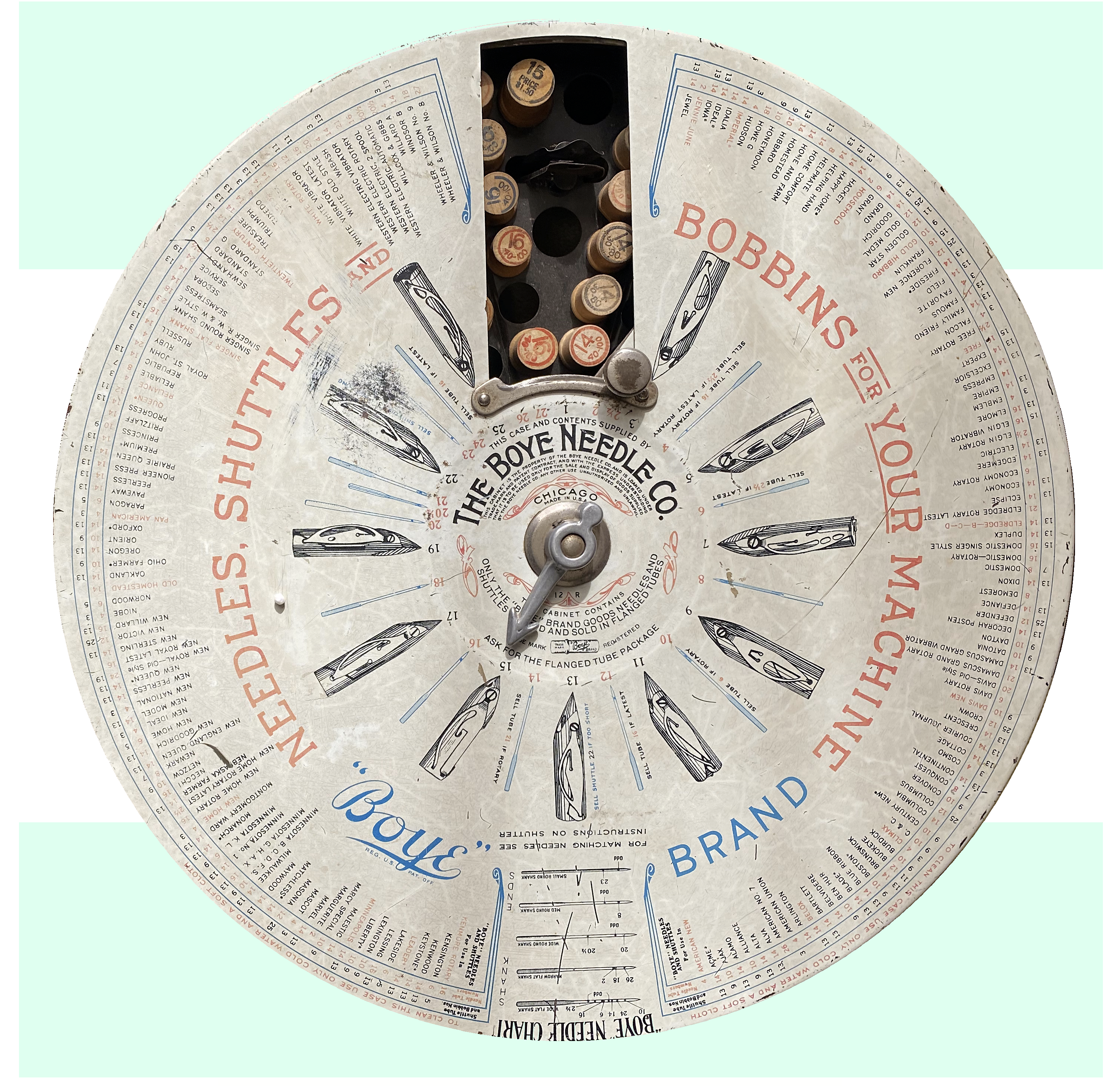

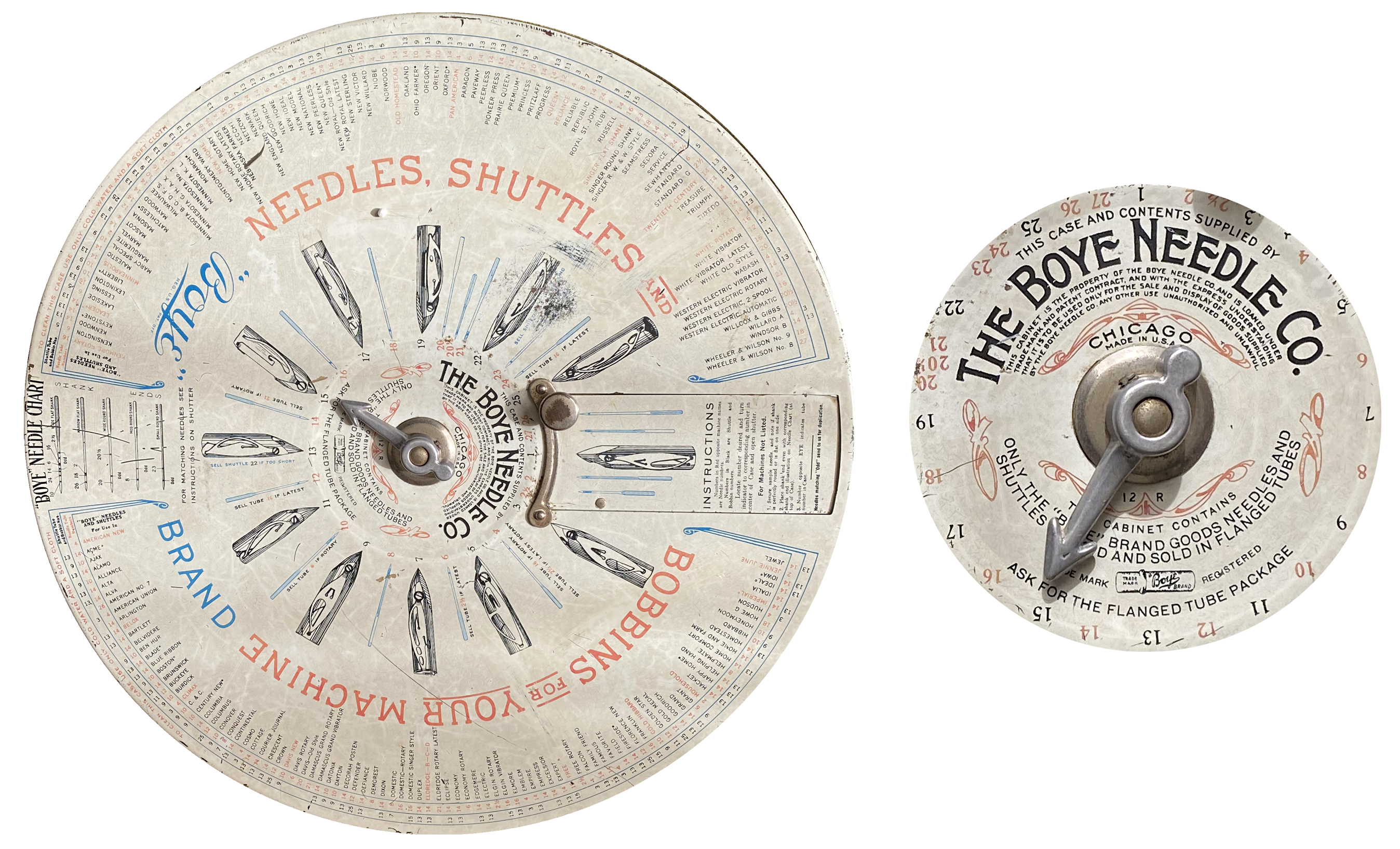

Museum Artifact: Boye Rotary Case for Sewing Machine Supplies, c. 1920s

Made By: Boye Needle Company, 4339-4343 N. Ravenswood Ave., Chicago, IL [Ravenswood]

“The public knows that where this Case is found, the well-known High Grade ‘Boye’ Needles, Shuttles and Bobbins can be secured.” –Boye Needle Co. advertisement, 1909

One might presume that selling sewing supplies in the early 1900s was a cinch. After all, treadle-style sewing machines were very common household appliances by this point in time, and the big clunky devices regularly required replacement parts and accessory re-stocking. The only trouble was, finding the exact needle, bobbin or shuttle that a customer needed could sometimes be like, well, trying to find a specific needle in a literal stack of needles.

One might presume that selling sewing supplies in the early 1900s was a cinch. After all, treadle-style sewing machines were very common household appliances by this point in time, and the big clunky devices regularly required replacement parts and accessory re-stocking. The only trouble was, finding the exact needle, bobbin or shuttle that a customer needed could sometimes be like, well, trying to find a specific needle in a literal stack of needles.

Despite our modern misconceptions, not every old sewing machine was manufactured by the Singer company—in fact, there were once over 100 manufacturers making a thousand different models, all with varying settings and size standards. As a result, anxious dealers and jobbers had to maintain a war chest full of tiny accoutrement and memorize all the respective compatibilities between machine and part. Fail to find or identify the right needle for your customer, and they’d be liable to abandon you and start ordering direct from those big mail order catalog houses instead.

Clearly, a new solution was needed. And a guy named Boye was just the man for the job.

History of the Boye Needle Co., Part I: “Something New and Dependable”

James H. Boye (born Jens Fraans Hartung Boye in 1873) grew up in Martin County, Minnesota; one of the many first-generation children of Scandinavian immigrants in the region. His Danish-born father, George A. Boye, came to America in 1861 and swiftly found himself serving in the Union Army as a private during the Civil War, albeit mostly as a marching band musician in the Wisconsin 15th Infantry, Company A. Fortunately, George came back to Minnesota unscathed, and he and his wife Emma raised four sons; James being the third.

By the age of 20, young James was already married (to Gertrude Isberg), and by 30, he had a couple kids of his own. To support them, he found work as a salesman in Minneapolis, mostly focusing on the sewing machine trade.

By the age of 20, young James was already married (to Gertrude Isberg), and by 30, he had a couple kids of his own. To support them, he found work as a salesman in Minneapolis, mostly focusing on the sewing machine trade.

Through this firsthand experience, James became acutely aware of the extremely inefficient realities of identifying and supplying customers with the right needle for their machine. There weren’t actually that many species of sewing needle in circulation—maybe a dozen or so—but with about 150 types of machine on the market, the guesswork involved in helping customers was consistently aggravating. Clearly, a better system was needed, and there was no point in waiting for someone else to come up with it.

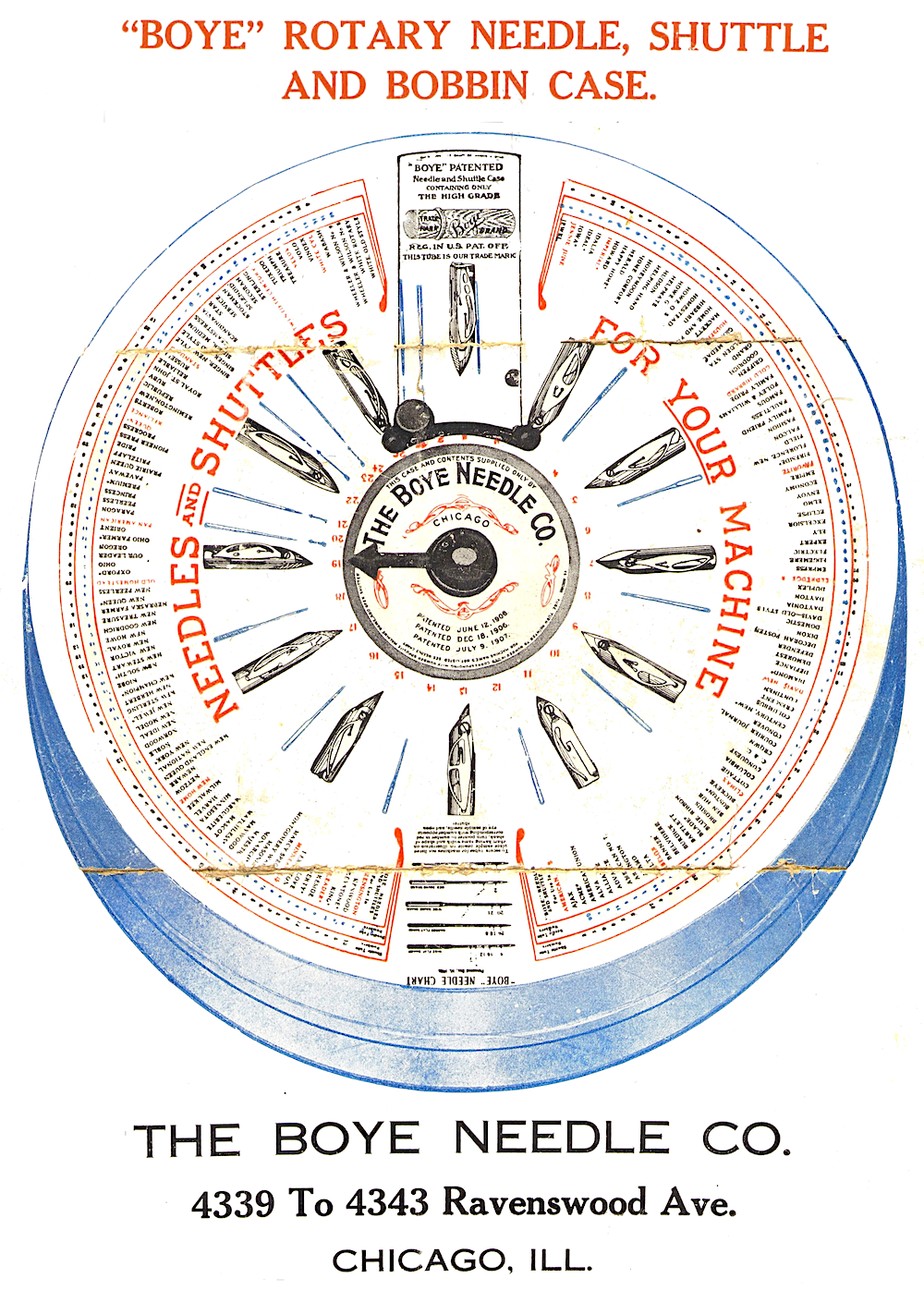

In 1903, a thirty year-old James Boye—still residing in Minneapolis— collected his first patent for a “Needle Case,” the purpose of which was to provide (a) “an index by means of which the make of needle used by any sewing-machine on the list may be quickly determined,” and (b) “a case for holding needle-containing tubes or boxes, in which such tubes are so arranged and marked that the required make of needle may be quickly found.”

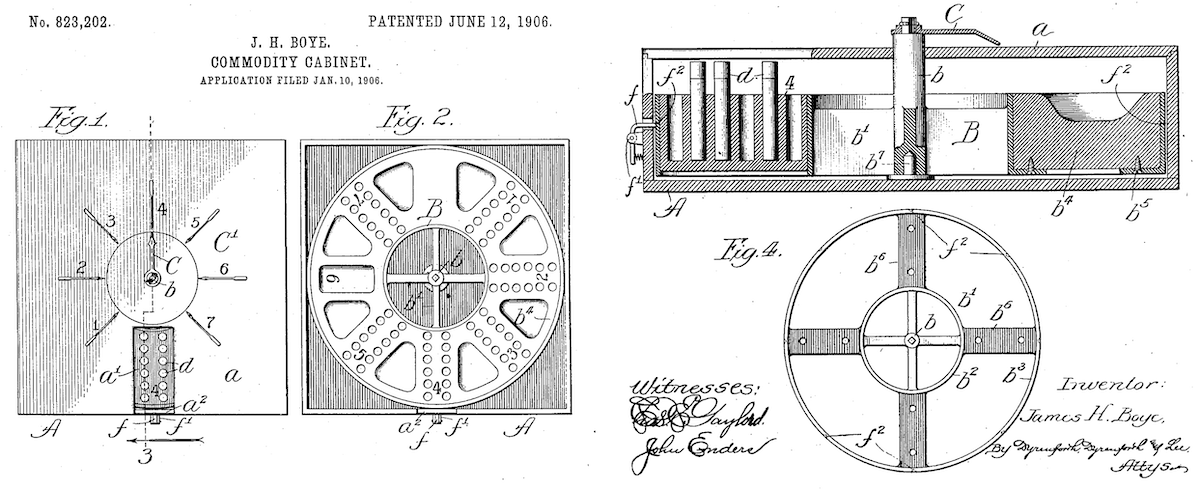

[Patent drawing from one of James Boye’s early “commodity cabinets,” 1906]

Boye’s original needle case was a rectangular wooden box, but design refinements would come regularly over the ensuring few years. The appeal of the box—sort of a card catalog for sewing needles—was an easy sell to frustrated dealers, and Boye soon realized he had a full fledged new business on his hands. Not only could he manufacture the commodity cabinets en masse, but he could also essentially rent them out to shopkeepers in order to ensure an ongoing relationship, equating to repeat needle orders and expanding distribution.

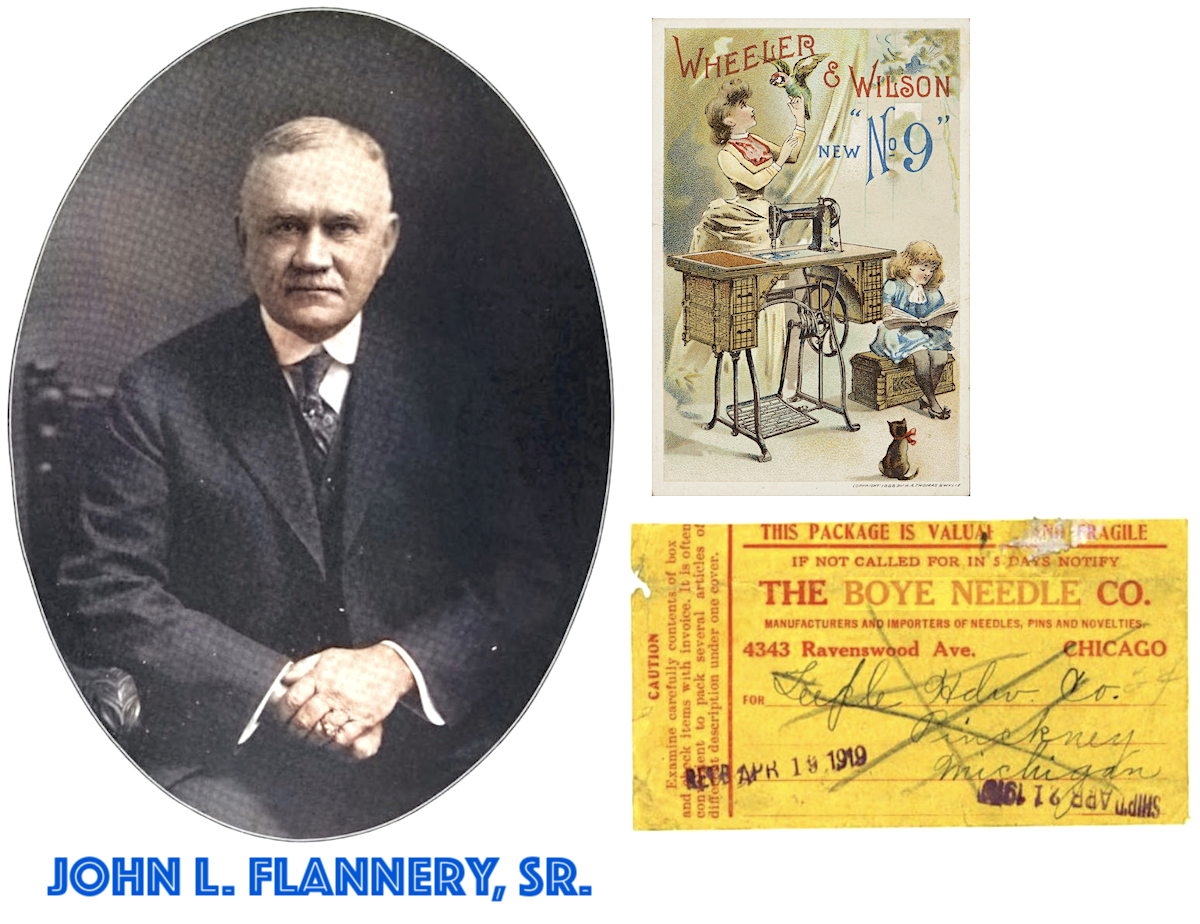

Of course, any time the word “distribution” was paramount to a business, a move to Chicago would be the next logical step, and in 1905, James Boye relocated here and launched the Boye Needle Company with two investors, John L. Flannery and May Phelan. The first company headquarters was located in a small, 500 sq. ft. space at 72 Wabash Avenue, where a workforce of about 30 people helped put a full line-up of “sewing machine necessities” into production.

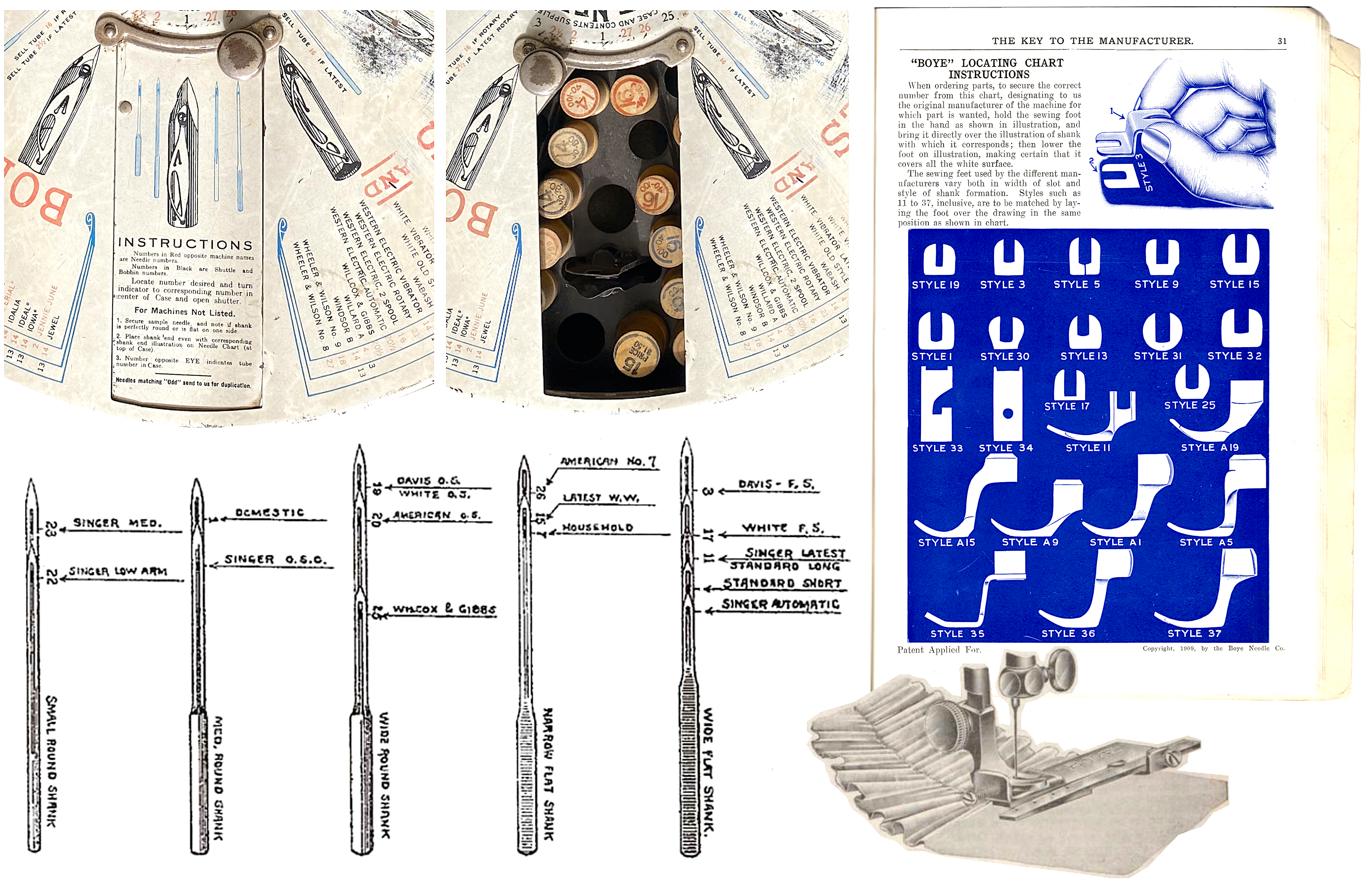

Between 1906 and 1910, James Boye collected at least 15 additional patents related to indexed needle cases and commodity cabinets, as well as needle threaders and needle holder tubes. During these years, the more familiar shape and style of the Boye case emerged, as improved rotary designs were now made from sheet metal and equipped for storing shuttles and bobbins as well as the full gamut of needles. An alphabetical list of sewing machine models was lithographed on top of the case, allowing the sales person to quickly cross-reference the compatible article in question. A Boye instruction manual detailed the process as such:

Between 1906 and 1910, James Boye collected at least 15 additional patents related to indexed needle cases and commodity cabinets, as well as needle threaders and needle holder tubes. During these years, the more familiar shape and style of the Boye case emerged, as improved rotary designs were now made from sheet metal and equipped for storing shuttles and bobbins as well as the full gamut of needles. An alphabetical list of sewing machine models was lithographed on top of the case, allowing the sales person to quickly cross-reference the compatible article in question. A Boye instruction manual detailed the process as such:

“To illustrate: If your customer wants a needle for the Climax machine, opposite the machine name, in the column headed ‘Needles,’ is a No. 4 printed in blue. Find this number in red on the inner dial, turn the indicator until it points to that number, open the shutter, and tubes of needles of that number will appear at the hand opening. Tubes with red numbers hold the finer sizes of needles, and those with black numbers, the coarser sizes.”

Maybe this system doesn’t sound intuitive and “simple” by our 21st century standard, in which any and all questions can be instantly answered (sometimes accurately) by a miniature robot on our bedside table. But in a time when most sewing machine owners didn’t even have electricity yet, it was a big step forward.

By 1909, stores from coast to coast were using their countertop Boye cases as a way to entice repeat customers.

“Something new and dependable,” read an ad for The Emporium, a department store in San Francisco. “Realizing that many of our customers have found it impossible to secure a perfect or correct needle for their machine, we have installed, in our Notion Department, the ‘BOYE’ Rotary Needle Case, which is a guarantee that we supply our customers with the well-known ‘Boye’ Brand Needles, Shuttles and Bobbins.”

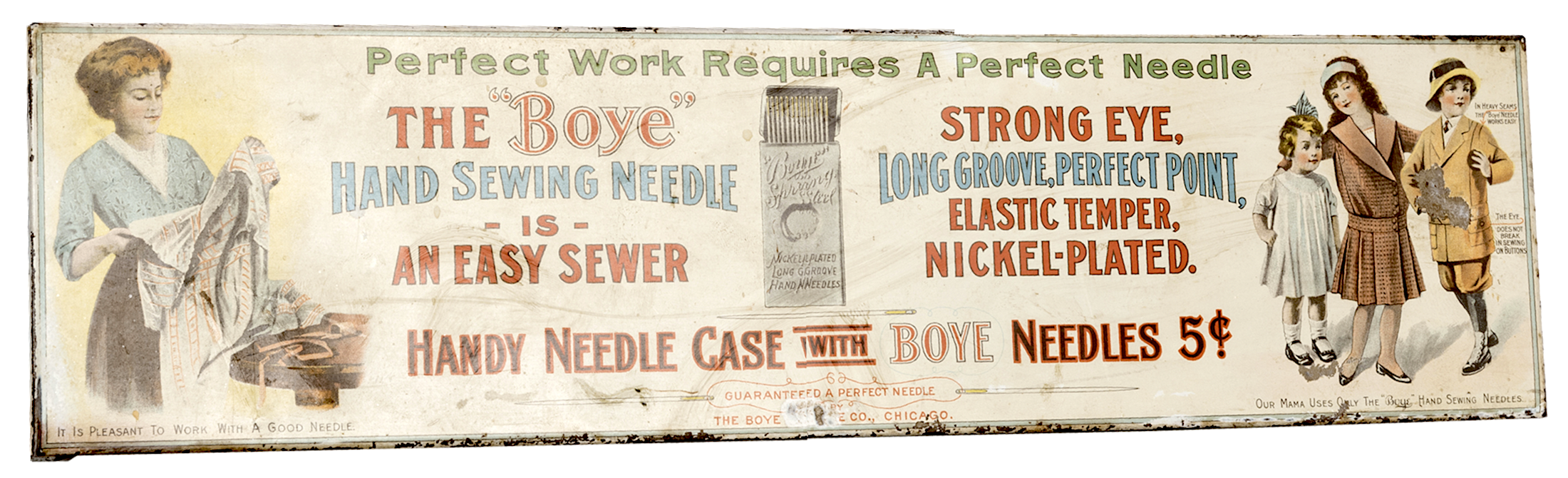

Boye’s own brand of needle, as described in that same 1909 Emporium ad, “has a deep groove and burnished eye. It is polished as smooth as glass and does not break the thread, as often experienced when using cheap needles.”

Boye’s own brand of needle, as described in that same 1909 Emporium ad, “has a deep groove and burnished eye. It is polished as smooth as glass and does not break the thread, as often experienced when using cheap needles.”

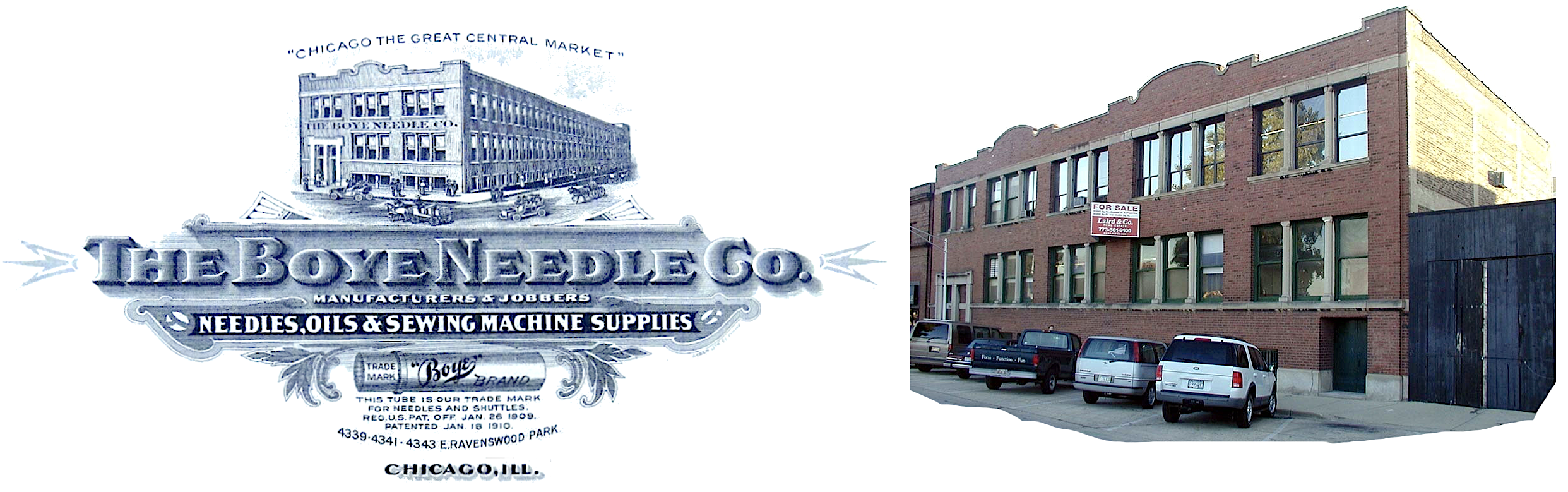

According to some sources, the original Boye offices were destroyed in 1908 when a fire gutted the building at 72 Wabash. Oddly, we haven’t been able to substantiate such an event, but we do know that the company already had a foot out the door beforehand, as a new dedicated factory building was under construction on the North Side in the rapidly emerging industrial corridor of Ravenswood. Boye Needle moved into the three-story factory at 4339-43 N. Ravenswood Avenue in 1909, and that location would remain their HQ for the next 90 years.

“The building shown above is the new home of the ‘Boye’ system,” company president John L. Flannery wrote in a letter to clients in 1910. “This enlargement of our facilities was made necessary by the success which our customers have met . . . being in position to satisfy the immediate requisites of their patrons for needles, shuttles and accessories of the finest quality. . . . In our new establishment—the largest supply house of its kind in the United States—we are in a position to serve you with accuracy and dispatch. We thank you for the courtesies of your past orders, and trust you appreciate fully the advantage and necessity of keeping all compartments of your Boye Needle Case filled and ready for business.”

[The Boye Needle factory at 4343 Ravenswood, as it looked in 1910 and in 2020. The building was expanded several times during its 90+ years as Boye’s HQ]

II. Boyes 2 Men

The “Boye” trademark has remained familiar to thimble-wielding folks to this day, which makes it a tad surprising that its namesake, James H. Boye, actually left the Boye Needle Company after a little over five years. While he removed himself from the board room, however, James continued funneling new patented inventions to the company through much of the 1910s, branching out from needles and cases into pencil sharpeners, shears, graters, key rings, and curtain rods. Confusingly, he also launched his own wholly separate business—known as the James H. Boye Manufacturing Company—which seemed to adapt his original indexing ideas more specifically for the curtain rod industry [see picture below].

Meanwhile, the running of the original, better-known Boye Company was left to its co-founder John L. Flannery Sr., his son John Jr., and a third key executive, Edward P. Byrnes.

Meanwhile, the running of the original, better-known Boye Company was left to its co-founder John L. Flannery Sr., his son John Jr., and a third key executive, Edward P. Byrnes.

Flannery Sr. was already 62 years old when he took over the reins from James Boye in 1910, and he was, by any measure, the far more experienced man when it came to the nuances of the sewing machine trade. He also had a bit of a rougher road to success.

Born in Middletown, New York, in 1847, Flannery was already a teenager when his Irish-born father went to fight for the Union in the Civil War. And unlike James Boye’s dad, the elder Flannery never came home, having perished in a Confederate prison camp (arguably the worst way to go). John was nearly old enough to get conscripted into the army himself, but the war ended when he was 18. Instead, his widowed mother moved the family to Ohio, where John helped support the household by working as a grocery clerk in Cleveland, learning the basics of good salesmanship.

In 1869, Flannery came to Chicago and joined the successful Wheeler & Wilson Sewing Machine Co., and he continued on with that firm for the next three decades, moving steadily up the ladder to the role of Western Sales Manager.

In a rather bold move for an old company man nearing retirement age, Flannery Sr. cut ties with Wheeler & Wilson in 1905 and hitched his wagon to the upstart Boye Needle Company instead, giving Boye immediate legitimacy on the national stage.

His son, John Flannery, Jr. (b. 1875), a Cornell graduate, joined the business in 1912, serving first as head of the New York office, then stepping into the role of vice president in Chicago.

A fellow Irishman, Edward P. Byrnes (b. 1873), started out in the role of secretary in 1910 and would remain a key figure at Boye Needle for decades.

This crew guided the company wisely after James Boye’s departure, and by 1919, the factory on Ravenswood Avenue was already undergoing significant expansion to keep up with the rapid diversification of the product line.

This crew guided the company wisely after James Boye’s departure, and by 1919, the factory on Ravenswood Avenue was already undergoing significant expansion to keep up with the rapid diversification of the product line.

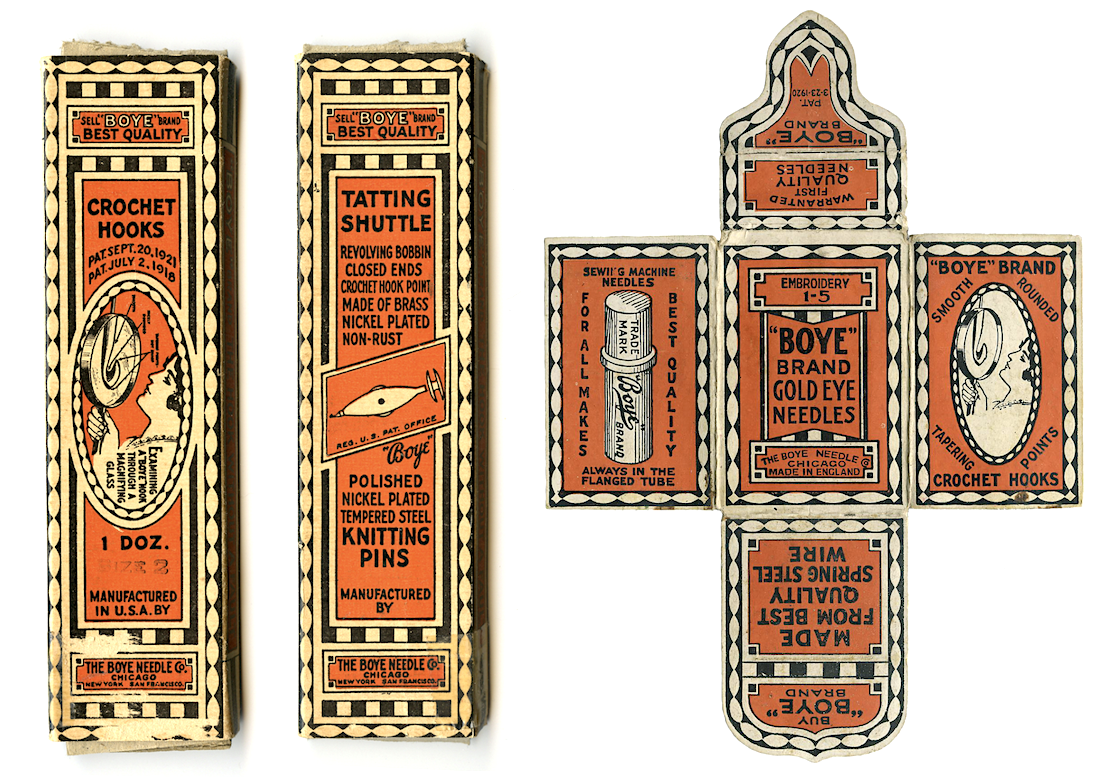

“The output of the large and modern factory,” according to the 1919 book Manufacturing and Wholesale Industries of Chicago, “includes hand and sewing machine needles of the highest grade, crochet hooks, crochet and yarn-ball holders, tatting shuttles, safety pins, hair pins, hair curlers, hat pins, ribbon leaders, beauty pins, skirt and belt pins, emergency buttons, stilettos, needle sharpeners, sewing machine shuttles . . . screw drivers, needle threaders, can openers, apple corers, curtain rods, jar wrenches, magic mirrors, nutmeg graters, pencil clips, nut crackers, etc.”

Some of these gadgets were leftover James Boye creations, while others were developed by new contributors like Gustav Carlson, John L. Needham, and John Flannery, Jr.

The factory now had about 150 employees on staff and a regular national sales team of 30. A big factor in the growth of the business had been World War I, when Boye stopped importing many of its materials and started manufacturing crochet hooks and other products that Americans had previously only ever sourced from England and Germany. Once foreign competition returned after the war, however, Boye Needle found itself struggling to maintain its newfound dominance. Company secretary Edward Byrnes spelled out the situation quite bluntly when he testified during a U.S. Congressional hearing on tariffs in 1921.

“The manufacture of crochet needles is a delicate, intricate, and expensive procedure,” Byrnes explained to the House Ways and Means Committee, while requesting major tariff hikes on imports within the industry. “. . . We feel that where we have gone to such expense in establishing an American crochet needle, equal if not superior to any foreign make, that we should be protected.”

Byrnes noted that Boye’s crochet needles cost about $22 per thousand, while imports were entering the market as low as $15 per thousand. “The cause of this difference,” he said, “lies entirely in the cost of labor.”

Byrnes noted that Boye’s crochet needles cost about $22 per thousand, while imports were entering the market as low as $15 per thousand. “The cause of this difference,” he said, “lies entirely in the cost of labor.”

Eventually, Byrnes and Boye were buoyed by the passage of the Fordney–McCumber Tariff in 1922, which placed new tariffs between 40-50% on imported crochet and sewing needles, helping to keep the factory chugging along through the 1920s.

During this period, even with the dozens of additional bits, bobs, and novelties being produced under the Boye name, its original product—the rotary case—remained an essential link between company salesmen and their associated dealers around the country.

The case from our museum collection likely dates from this fruitful period, post-WWI, pre-Depression.

III. The Knitting Boom

In December of 1920, John Flannery, Sr., aged 74, died suddenly of a heart attack while dining with chums inside the grill room of the Chicago Athletic Association.

While seemingly the heir apparent, John Flannery, Jr. found himself in an ongoing dispute with his sister, Florence Woolverton, over their father’s estate, leading to an ugly drawn-out court battle. This might have contributed to John Jr.’s somewhat early retirement from the Boye Company in 1927. To add an extra dash of drama to this side plot, Florence and her husband—an Indiana manufacturer named Howard Woolverton—were later carjacked in 1932 and held for ransom by a pair of thugs in South Bend, one of whom was the gangster George Kelly Barnes, better known as Machine Gun Kelly. The Woolvertons were lucky— both were eventually freed, and no ransom was ever paid.

[Left: South Bend Tribune front page reporting on the kidnapping of businessman Howard Woolverton in 1932. Woolverton had business ties to the Boye Needle Company, and his wife Florence was the daughter of Boye founder John L. Flannery, Sr. Right: Machine Gun Kelly, the kidnapper who failed to get his $50,000 ransom demand from the Woolverton / Flannery family. When Kelly tried the same routine a year later with the tycoon Charles F. Urschel, he got his $200,000 payout, but this time, the authorities tracked him down shortly thereafter. Machine Gun spent the rest of his life in prison, where he earned the new disparaging nickname, “Pop Gun,” implying his tough-guy image wasn’t earned.]

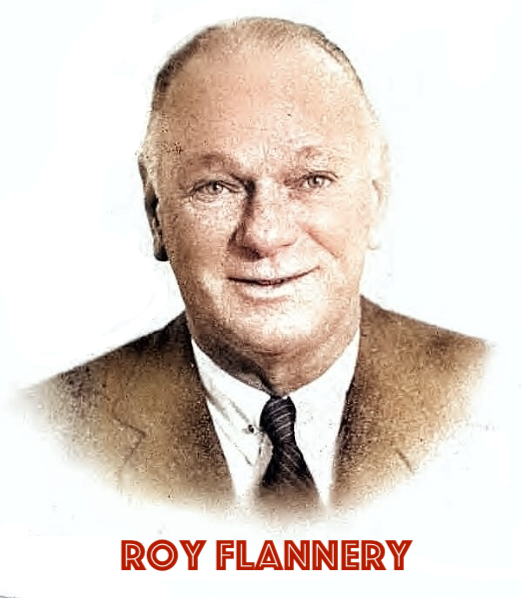

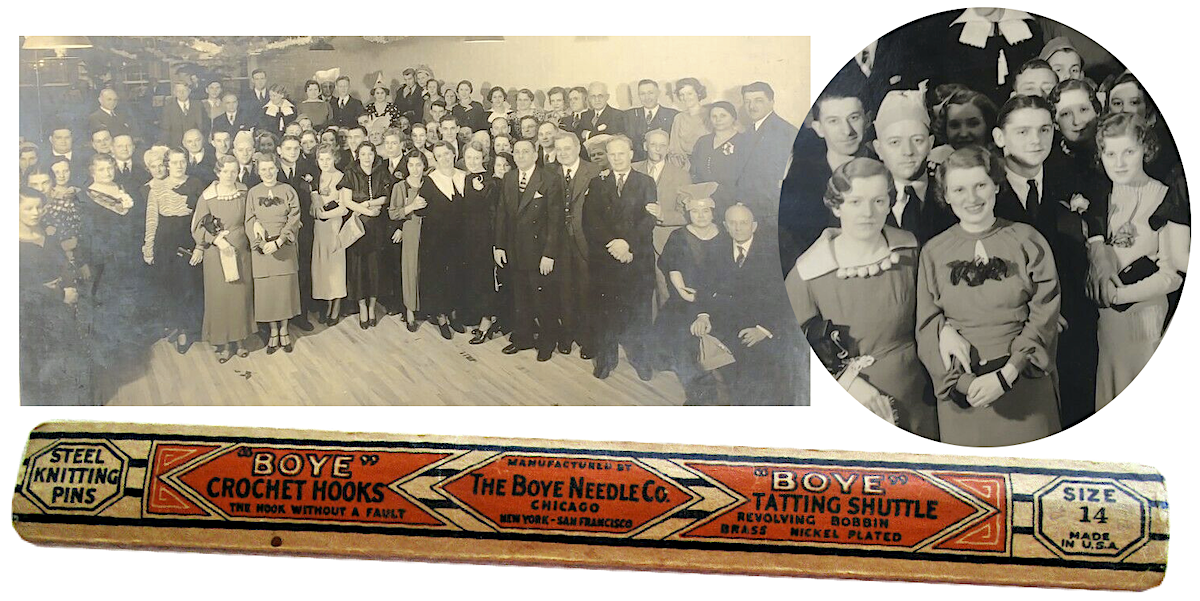

Meanwhile, back in Chicago, a third generation of the Flannery family was keeping the legacy going at the Boye factory. Roy L. Flannery, (b. 1902) had become the company sales manager by 1933, serving under Edward Byrnes, and it was his task to try and keep orders coming in during the depths of the Depression.

One unexpected boost to this effort was the revived popularity of knitting across America, as the Depression had inspired both men and women to embrace this cost-efficient DIY skill. To make sure his sales team was hip to this new trend, Roy Flannery encouraged them to learn how to knit in their own free time, and by the mid ‘30s, all 60 salesmen on the Boye payroll had supposedly mastered the fundamentals, although company president Byrnes still “couldn’t knit a stitch.”

One unexpected boost to this effort was the revived popularity of knitting across America, as the Depression had inspired both men and women to embrace this cost-efficient DIY skill. To make sure his sales team was hip to this new trend, Roy Flannery encouraged them to learn how to knit in their own free time, and by the mid ‘30s, all 60 salesmen on the Boye payroll had supposedly mastered the fundamentals, although company president Byrnes still “couldn’t knit a stitch.”

Around this same time, in 1935, Fortune magazine came to the Boye plant on Ravenswood to shine a light on the now 30 year-old business and its recent success.

“The knitting boom has done wonders for the Boye Needle Co. of Chicago, the works in American knitting needles,” the article read. “According to Boye’s own estimate, it made 75 percent of the 10 million knitting needles sold in the U.S. last year and about 90 percent of the 5 million crochet needles.”

Fortune notes that Boye’s biggest sales increase came in circular needles, which have a point on both ends, allowing for “round and round” seamless knitting. The company also patented what it called “the first knitting needle improvement made since A.D. 79—this date having been chosen because the ruins of Pompeii have yielded up bone needles that are exactly like contemporary ones. The improvement is in the point of the needle: instead of being sharp, it is round and tapers concavely back to the needle’s stem. It is particularly useful with inelastic yarns. This breathtaking invention was the brainchild of President Byrnes, vice president Edward Davis, and superintendent August Carlson.”

[Workers gather to mark another addition to the Boye factory building on Ravenswood Avenue in 1935; silly hats included.]

Knitting needles still only represented about half of Boye’s business in the 1930s, as they continued to experiment with more novelties and kitchen utensils. “Boye has to diversify to level out the peaks and valleys of the business,” Fortune reported. “So it listens seriously to all inventors of new gadgets.”

In 1941, Roy Flannery was elevated to the role of company president, as Ed Byrnes moved to the chairman seat. Byrnes died three years later, but again, Boye Needle managed both a peaceful transfer of power and the challenges of another world war.

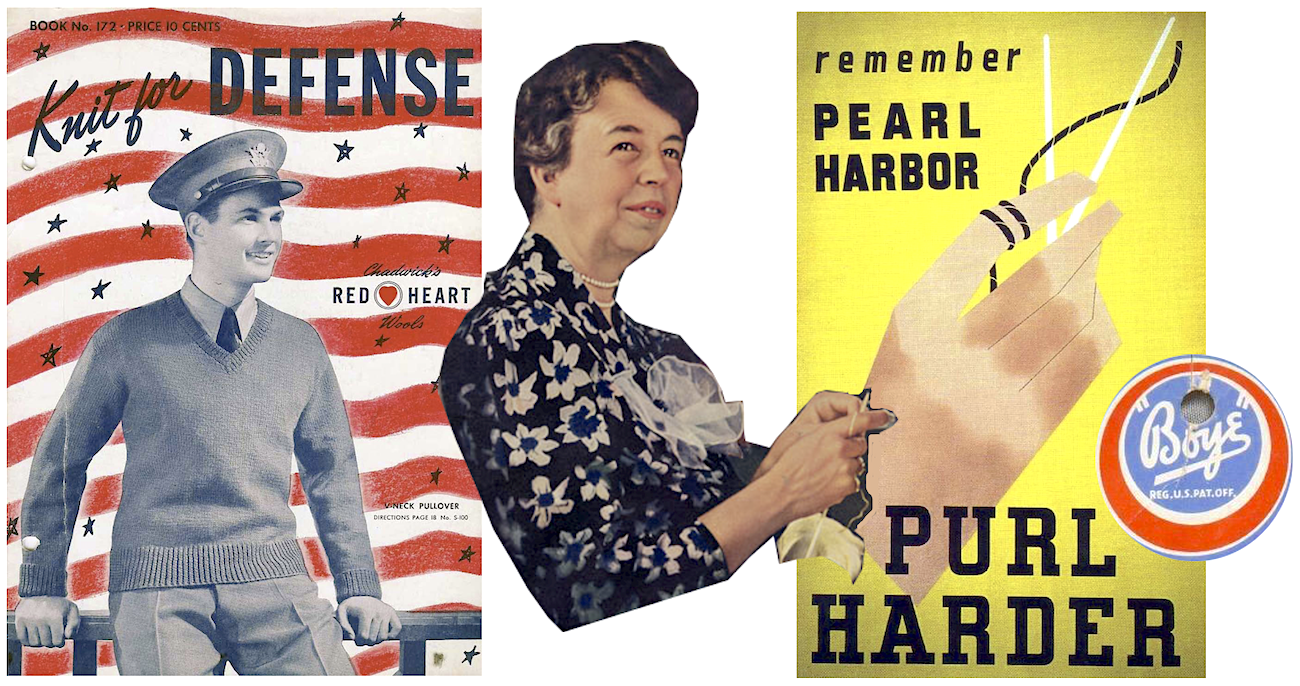

Unlike a lot of metal manufacturers, Boye’s product was still deemed necessary to the war effort, as a soldier’s socks, sweaters, and hats couldn’t knit themselves. Knitting had also gone from a cost-saving measure of the Depression to a patriotic act in wartime, as Eleanor Roosevelt helped usher in the “Knit for Defense” movement, encouraging Americans on the homefront to get their needles out and help supply needed knitwear for the troops overseas.

IV. Mergers and Departures

Roy Flannery remained the president of Boye Needle until 1961, when David Wilson Hendry (b. 1914) assumed the role. Hendry was a California boy, Stanford educated, but he found himself ushered into the needle business when he married Mary Woolverton, granddaughter of John Flannery, Sr., and cousin to Roy Flannery.

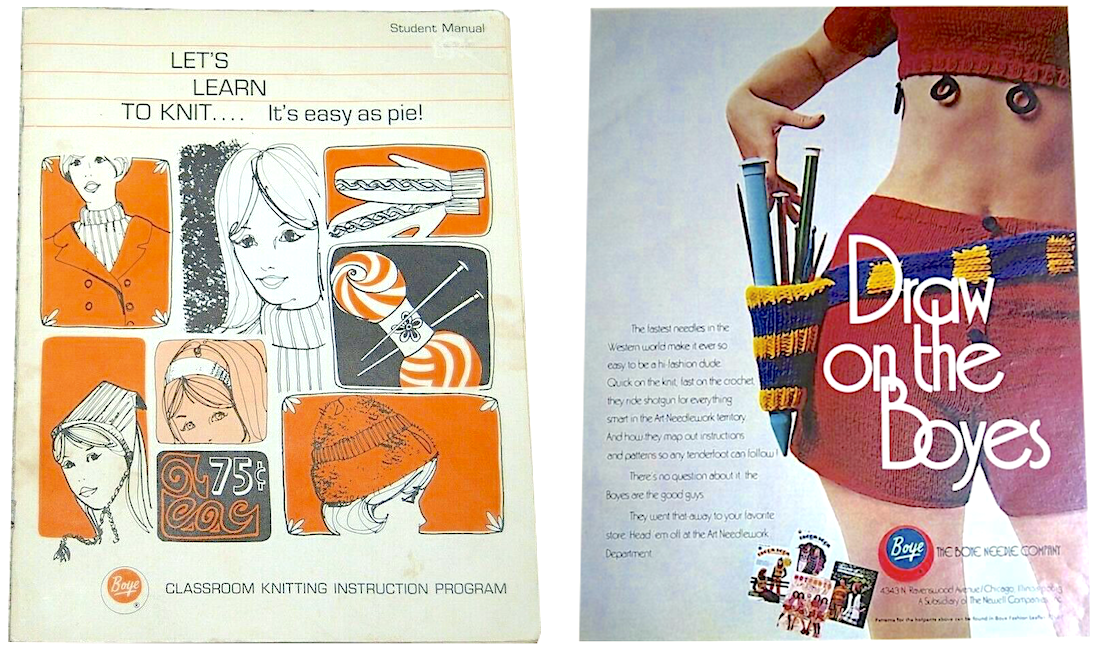

In the ’60s, Boye Needle—like every other company—seemed to recognize the sudden emergence of the youth market, and they began running ads in magazines like Seventeen, hoping to “hook” younger girls on the Boye brand for all their groovy knitting projects. Once again, the company also benefited from a wholly unexpected fad, as crocheting made a big comeback in the late ‘60s.

In the ’60s, Boye Needle—like every other company—seemed to recognize the sudden emergence of the youth market, and they began running ads in magazines like Seventeen, hoping to “hook” younger girls on the Boye brand for all their groovy knitting projects. Once again, the company also benefited from a wholly unexpected fad, as crocheting made a big comeback in the late ‘60s.

“This crocheting craze has caught the industry unaware,” president Hendry admitted in a 1970 interview. “The orders are still piling up and we often run as much as 10 days late.”

Boye’s Ravenswood factory—once the picture of modern efficiency—was now decidedly outdated and unfit for the needs of the world’s largest needle manufacturer. Despite more than $8 million in sales over the 1970-71 fiscal year, the company didn’t have any dedicated factories outside of its Chicago headquarters (aside from a small fabric plant in Burlington, Wisconsin, that had been acquired from another business). It seemed inevitable that a change was on the horizon.

Sure enough, in 1971, Roy Flannery retired as a board member after 40 years connected to the business, and months later, D. W. Hendry announced that the Boye Needle Co. was merging with the rising Newell Corporation, out of Freeport, IL. Boye was the fourth company Newell had scooped up in 1971 alone, and it was quickly reorganized as a division of Newell, with various changes in leadership over the next few years.

Surprisingly, over the next 20 years, Newell never shut down the Ravenswood plant, although in-house production slowed as a greater reliance on imports returned. By 1989, despite steady sales, Newell opted to move on from the sewing industry, and two of its top properties, Boye Needle and William E. Wright Co (a long-running textile business), wound up landing together, under the independent ownership of Wrights. To this day, Wrights continues to produce sewing accessories under the Boye brand, although both firms are now subsidiaries of CSS Industries.

Surprisingly, over the next 20 years, Newell never shut down the Ravenswood plant, although in-house production slowed as a greater reliance on imports returned. By 1989, despite steady sales, Newell opted to move on from the sewing industry, and two of its top properties, Boye Needle and William E. Wright Co (a long-running textile business), wound up landing together, under the independent ownership of Wrights. To this day, Wrights continues to produce sewing accessories under the Boye brand, although both firms are now subsidiaries of CSS Industries.

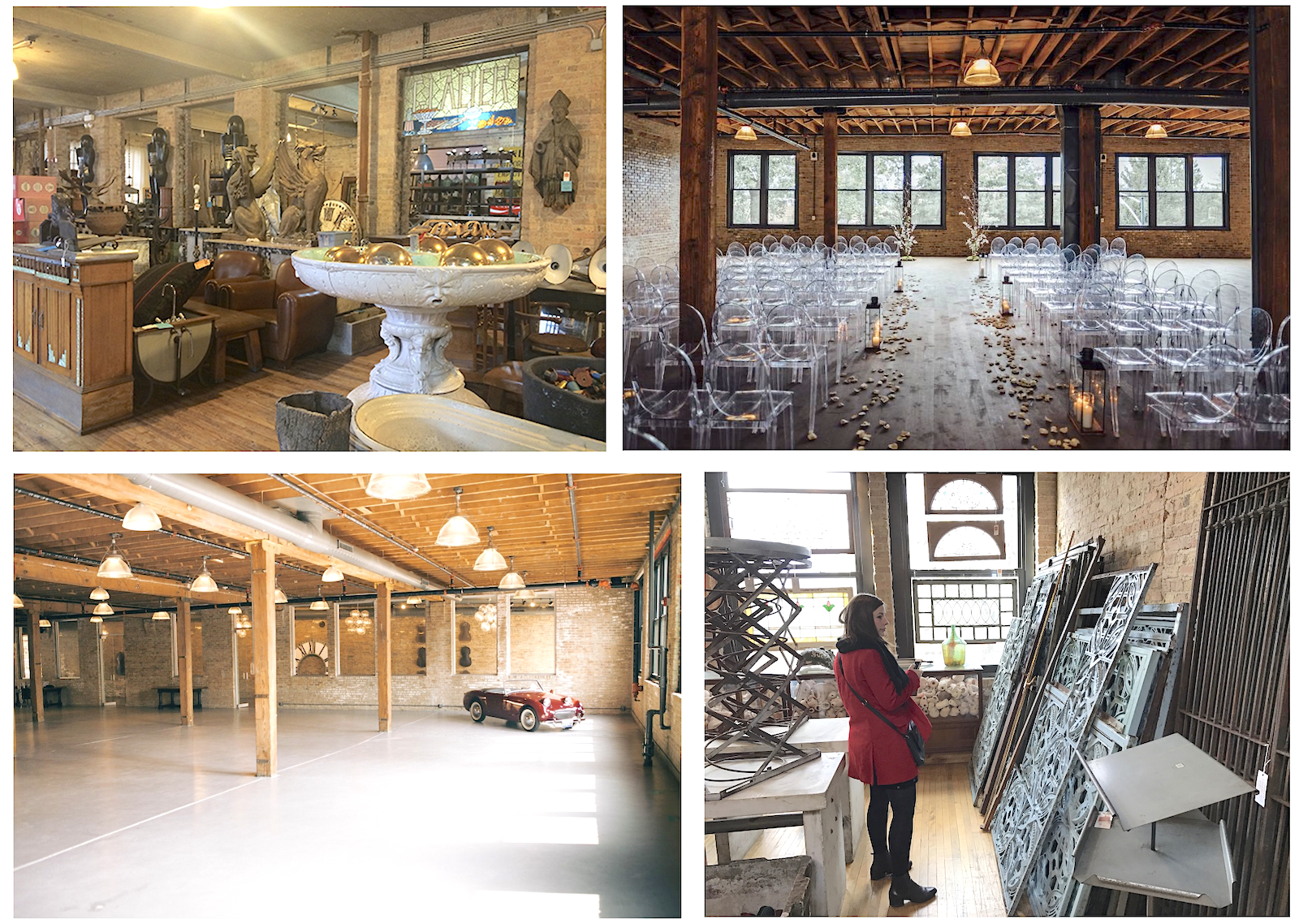

After Boye’s Chicago plant in Ravenswood finally closed in the early 2000s, it was brilliantly repurposed as part of one of the country’s largest high-end antique showrooms, Architectural Artifacts. Unfortunately, that business closed in 2018.

[The former Boye building at 4343 N Ravenswood and its neighboring building have been used as antique showrooms and event spaces since the early 2000s]

Sources:

“The Boye Needle Company” – Manufacturing and Wholesale Industries of Chicago, Vol. 3, by Josiah Seymour Currey, 1919

“John L. Flannery Dies Suddenly in Chicago A.A.” – Chicago Tribune, Dec 9, 1920

Edward P. Byrnes testimony – Hearings on General Tariff Revisions Before the Committee on Ways and Means, U.S. Congress, 1921

“South Bend Man Kidnapped for $50,000 Ransom” – Garrett Clipper, Jan 28, 1932

“Off the Record” – Fortune, July 1935

“John Flannery, Director of Needle Concern, Is Dead” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 25, 1937

“Today’s Women are Hooked on Crocheting” – Evansville Press, Feb 27, 1970

“Flannery Retires from Firm’s Board” – Chicago Tribune, March 11, 1971

“Top Sewing Products Firm Joins Newell” – Freeport Journal-Standard, Dec 16, 1971

“A History of the James Boye Commodity Cabinet,” by Claire Sherwell and Bill Grewe

We have a Boye Parlor Golf game. How rare is this?

My family has found a photo album from 1916 and 1919 of my great aunt Barbara Miller who has many photos of the Boyd Needle Co. events etc. where she was an employee. Is anyone interested in obtaining these pictures from us for a museum or archive?

I just bought secondhand, a wooden quilt & rug frame with stand and amazingly all pieces are in the box. There is no yr. It says it’s model 7607. Would you have any info on it ? The yellowed direction of says boye at the bottom and the person wrote her name on the outer box. TIA, Donna

My mother was Mary Elizabeth Woolverton, Hendry, Howard Wolverton‘s daughter. We have a ransom note for $7500 which was paid for the release of my grandfather. My mother said it was delivered by John Jr and he soiled himself in the process. I learned a lot from this article.

I have a Needles and Shuttles (round) 1906 &7 with many items inside – would you be interested in it.

Quilters Workshop

Oak Harbor, WA

360 675-7216

I have a Boye needle Master kit. But I have lost the two keys, two couplers and two needles to cable adapters. Is there any for me to order them

I have the circular needle collection snc I noticed one of the cable tips broke into a needle. Is there any way to get it out and replace the defective cable?

I am bidding on an advertising piece and cannot find any history, picture or reference on line. It is a brass(I think) needle about 26 inches long and has “Boye” Brand stamped in relief next to the thread hole. The “Boye” is in script font and Brand is in block letters. Weight is about 15-18 lbs.! Any information would be helpful

To whom it may concern:

Someone”’’ anyone please help me get in contact with the owners or family of them because I have a old wooden needle holder with the boys needle company from I think 1900’s. It’s in pristine condition and has the trade marked logo on it. I figured it may be something they would like to have

They are indeed very nice to have, but there are a LOT oit there sold on ebay and Etsy, a fair number pristine. You keep it as it is a piece of history. Just a piece there’s a lot of. You could get from $5 to $10 if it has the original unused needles.

I treasure my hand a needle assortment $.29 who knows how long ago I got these I’ve had them for at least 45 years! Highest quality! That’s why they last so long. Even my old safety pins are better than all the ones they’re making now! Thanks for being there and having such an interesting history. Barbara from Brunswick, Ohio

I have a tool marked Boye that includes a silver 3/4″ disc with a 1/4″ slit in the middle and a 3″ silver wand or rod that had a triangle shape and a rectangle shape punched out of the square end. I can send a picture when I get your email address. What are these for?

Nina Fitzpatrick, Sherrills Ford NC

Anyone is welcome to visit my shop with photos for information. I’ve studied vintage crochet hooks for many years and I love sharing what I know. No purchase necessary, LOL.

HookedonNeedlework

I’ve got a Boyle needle cartridge marked ‘6’ and ‘40-100’ on the end. I don’t know if it’s something you want for the museum. Not sure whose it was, but I found it while cleaning-out my mom’s stuff after her death in 2022. My grandmother was born in 1888 and my mom in 1931. Do you want it?

I saw a hook that looks kind a little a crochet hook but it make a piece of cloth that won’t unravel when you do cut it. Did Boye make it and if they did what is it called. Where can I get one. All I know about it is that it was made in the 1970.

thanks so muck

James a.

I have a pice that comes from your company and I would love to know what it is

I have an old The Boye Needle Company rotary case including many needles in wooden containers. The case has some rust issues. Can you tell me how rare the cases are, and any value they might have. Thank you.

I’m very familiar with these. I’m not trying nor do I want to buy it. I have 2 packed rooms of vintage needlework items! I just love sharing what I know. After intensely study abd continued research over the past 6 years, sharing makes it all the more worthwhile! I’m on Etsy. HookedonNeedlework

I really enjoyed reading this article. Perhaps you can help me too. I work at Parker Avenue Knits in Detroit . Last week a customer gifted me with a Boye Needlemaster Set from the 1960s. I just love it. It is missing the adapters to join the needle to the cable. The kit otherwise is in pristine condition. Is it possible to purchase the adapters today? Thank you.

I worked at your company in around 1967 and was wondering if your company is still there?

I worked at the Boye Needle Company in the summer of 1965, making plastic knitting needles. I am delighted to discover a wealth of historic information about the company, its building, and its uses since being a factory.

I have an item in my treadle sewing machine drawer that says Boye Needle company and wanted to identify what it is but can’t attach. Looks like its made of copper. Looks to be 3” long with 3 points of different lengths opposite end is circular with hole in it.

Hi

I just found a in the box automatic door check manufactured by your company. Can’t find any info on it. It even has the instructions for installation. Any info would be appreciated.

Thanks

Rosie

I have an unopened packet of a No. S Bracket. Boye Patent No. 1,804,669. Found it in grandma’s stuff.

Can you enlighten me on what it is, when it was made, and its value, if any?

Thank you in advance.

John

You can search that on the USTPO site. United States Trademark & Patent Office. It is a pain to use, but fun if you like a wild goose chase first . Even googling a patent “company x patent ####” can get a hit!

I gave some takking tools the are my mothers and the belonged to her mother. My mom is 94.

I would love to donate these for your museum if you would like them.

They say “Boye” improved

Made on USA

The boye needle company Chicago

On back it says

Boye improved

More thread less knots