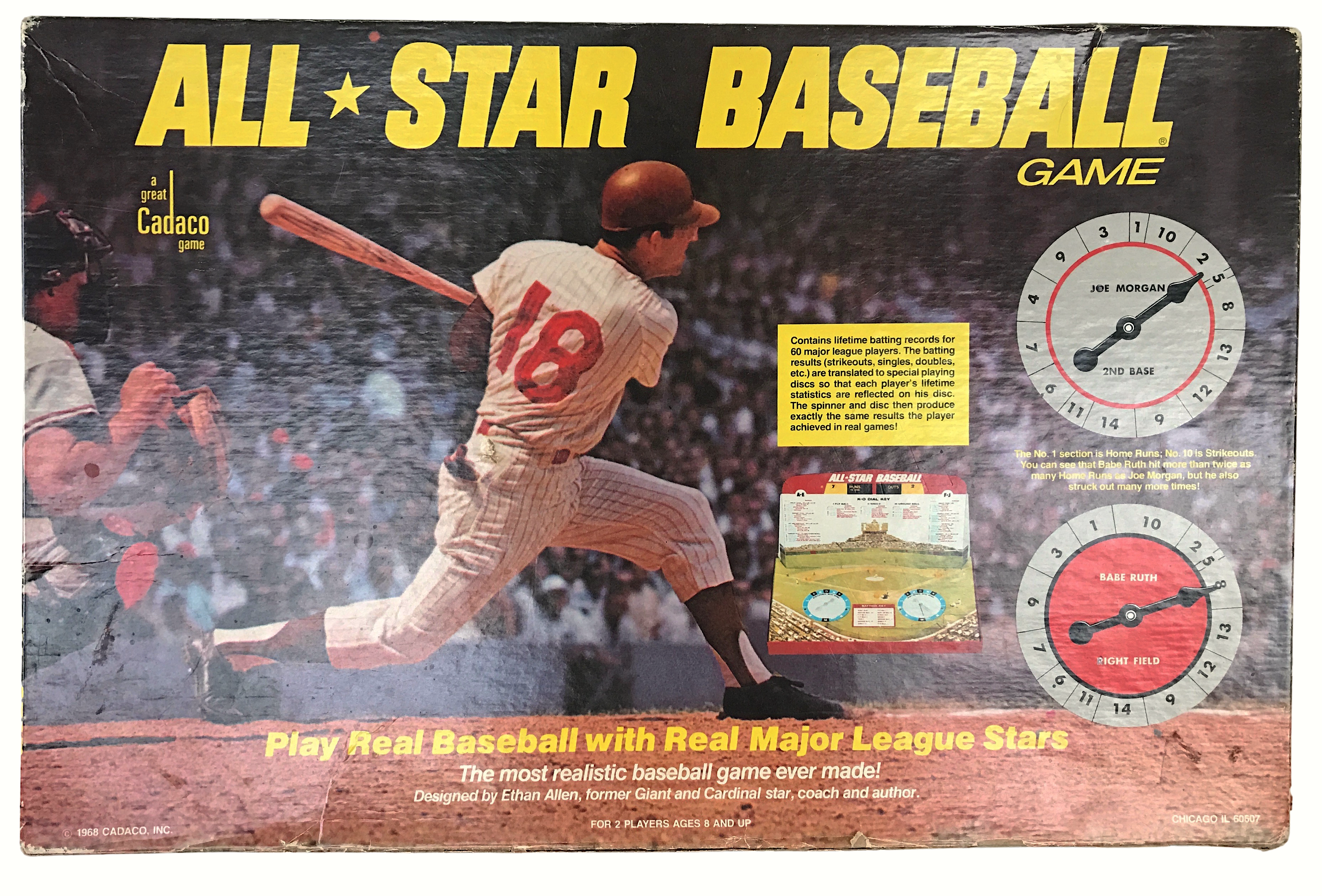

Museum Artifact: All-Star Baseball Board Game, 1968

Made By: Cadaco Inc., 310 W. Polk St., Chicago, IL [Downtown / The Loop]

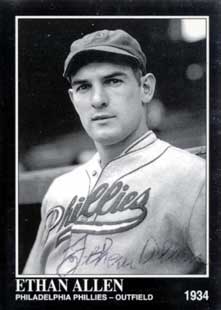

Half a century before “fantasy baseball” gave every Joe Sixpack the illusion of running his own Major League ballclub, the seeds of that multi-million dollar industry were planted inside colorful cardboard boxes like this one. “All-Star Baseball,” which first appeared in 1941, actually predated similar stats-based games like “American Professional Baseball Association” (1951) and the famous “Strat-O-Matic” (1961). It took two forward-thinking brainiacs to get the ball rolling—a former Major Leaguer named Ethan Allen and a savvy young business owner named Donald J. Mazer, president of Chicago’s Cadaco-Ellis Company.

Mazer was an Oklahoma native, born to a Russian father and English mother at the turn of the century. A former student at Columbia Law School, he eventually followed scores of other Americans out to the left coast during the Great Depression, presumably in search of. . . something. While living in San Leandro, California, in 1935, the 33 year-old Mazer went into business with an old friend, Charles Berisheimer, and the pair rented out a small garage with the goal of designing tabletop games. With so many people out of work, they figured, creating affordable, time-killing entertainment might be one of the few smart industries to break into. They called their new company “Cadaco,” short for “Charles and Don and Company.” Cadaco’s California era, however, would not last long.

Mazer was an Oklahoma native, born to a Russian father and English mother at the turn of the century. A former student at Columbia Law School, he eventually followed scores of other Americans out to the left coast during the Great Depression, presumably in search of. . . something. While living in San Leandro, California, in 1935, the 33 year-old Mazer went into business with an old friend, Charles Berisheimer, and the pair rented out a small garage with the goal of designing tabletop games. With so many people out of work, they figured, creating affordable, time-killing entertainment might be one of the few smart industries to break into. They called their new company “Cadaco,” short for “Charles and Don and Company.” Cadaco’s California era, however, would not last long.

According to legend, within the company’s first year of existence, Cadaco was among the many game distributors approached by designer Charles Darrow about publishing his new game “Monopoly.” Mazer and Berisheimer shrugged and passed on it. It was the first of several unfortunate decisions that would keep Cadaco a second fiddle to the likes of Parker Brothers and Milton Bradley through the decades to come.

Mazer’s greater focus during the company’s early years was the development of a new style of sports themed board game. One of his earliest titles, “Touchdown,” was promoted right on the box as “A Scientific Football Game,” introducing Mazer’s brainier take on America’s more jockular pastimes. This same game was alternately packaged during the 1930s and early ‘40s as “Varsity” and—with a celebrity endorsement from the athletic director at Notre Dame—“Elmer Layden’s Scientific Football Game.” In each version, players rolled dice to reveal the outcome of each play on the gridiron, with 30 plays constituting one quarter of football. Scientific though it may have been, the game was still geared mainly toward pre-teen boys.

[Cadaco-Ellis found a new home at Chicago’s Merchandise Mart in 1937]

[Cadaco-Ellis found a new home at Chicago’s Merchandise Mart in 1937]

Gaining some traction with a niche fan base, Cadaco moved to a new office in Oakland for a short time, then—just two years after its founding—made the bold leap to Chicago in 1937, hoping to benefit from a more centralized distribution hub. A key component of this decision was Donald Mazer’s new bride, Eleanor Ellis, who not only became his partner in life, but also bought out his old business partner Berisheimer. In turn, the company was re-christened “Cadaco-Ellis” and set up shop in a small nook (office #1458) of Chicago’s mighty Merchandise Mart—at the time the largest building in the world (four million square feet, to be precise).

These became the golden years of creativity for the Cadaco crew, as Donald and Eleanor wisely surrounded themselves with experts in a wide range of fields—from marketing, packaging, art, and design to sports management. They brought a man named Stanley Hopkins into the fold as a partner, and took over the publishing of his already popular hybrid card game Tripoley (“The Game of Kings and Queens”), which became one of the company’s top-selling titles.

A San Francisco based artist named C. Leslie Crandall [pictured] also joined the team, helping to design games ranging from chip-based gambling entertainment (“Kitty Keeno” 1938) to patriotic “name that quote” trivia (“Yankee Doodle” 1940).

A San Francisco based artist named C. Leslie Crandall [pictured] also joined the team, helping to design games ranging from chip-based gambling entertainment (“Kitty Keeno” 1938) to patriotic “name that quote” trivia (“Yankee Doodle” 1940).

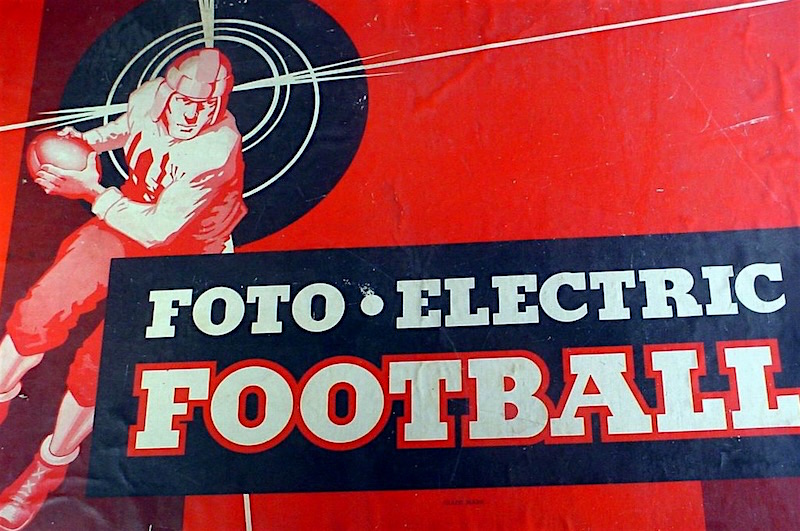

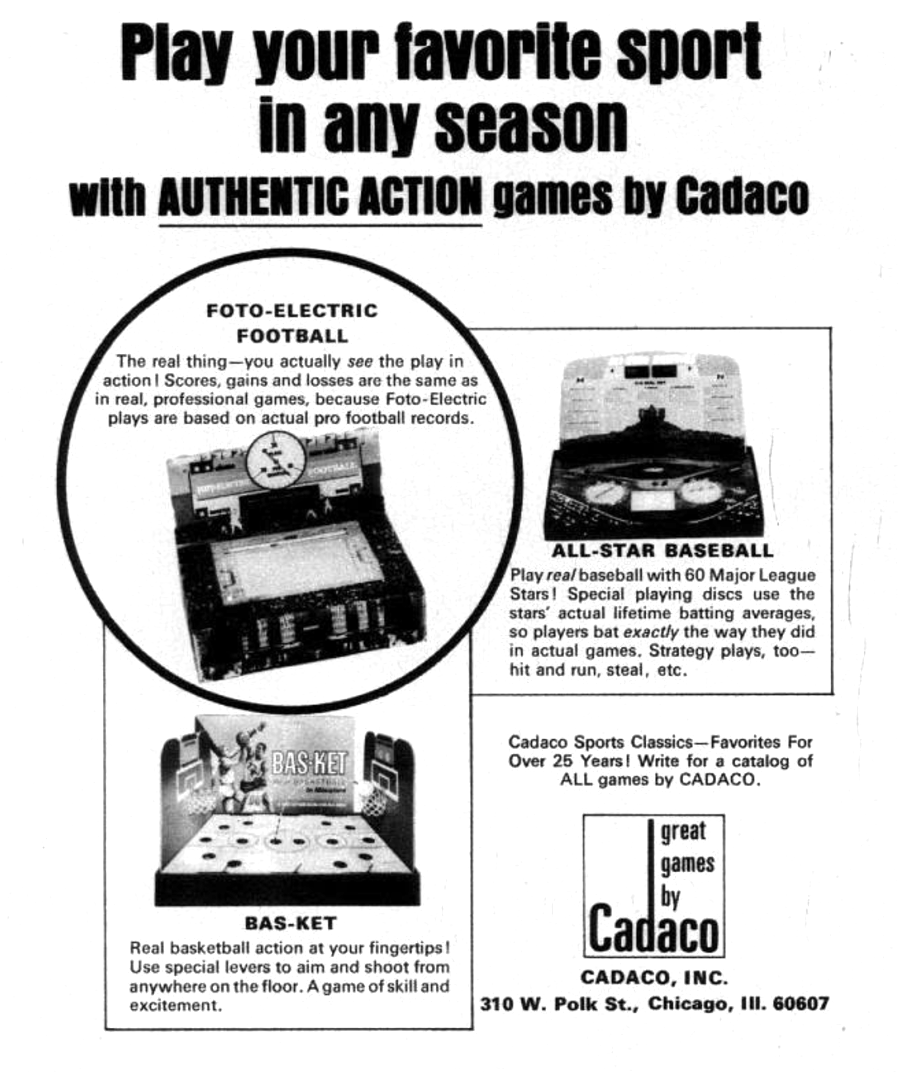

Speaking of trivia, it’s a fun factoid to note that the inventor of Cadaco’s popular “Foto-Electric Football” games—Alan LeMay—would later go on to much greater fame as a novelist, penning Western classics like The Searchers and The Unforgiven. LeMay first licensed his patented board game design to Cadaco-Ellis in 1940, impressing the Mazers with his innovative use of a “successive revelation of light” (a light bulb inside a box beneath moving placements of translucent paper) to somehow create a realistic football simulator. He also started developing a baseball version of Foto-Electric, and presented the specs to Donald and Eleanor in 1942—as LeMay recounted in a letter to his parents that January.

“Last night we had to dinner the Mazers of Cadaco-Ellis,” LeMay wrote. “Don Mazer is the dynamo type, very jolly. I should say about 36 years-old [actually 40]. . . . I spent the afternoon rigging up a partial model of my baseball game to show him and he was very enthusiastic, wishing to get a hold of a complete model right away to begin production plans. This surprised even the very optimistic Jack Schurch [salesman for Cadaco-Ellis], who sees so many hundreds of games constantly rejected, including great numbers of ideas of his own.”

[Cadaco’s Foto-Electric Football, created by Alan LeMay in 1940]

[Cadaco’s Foto-Electric Football, created by Alan LeMay in 1940]

Despite the rosy outlook that night, LeMay’s Foto-Electric Baseball never really got off the ground. Rationing during World War II limited Cadaco’s resources considerably, and perhaps just as importantly, the Mazers had already found their flagship baseball simulator a year prior, with the aforementioned and presently featured “All-Star Baseball.”

While less razzle-dazzle and techy than Foto-Electric, All-Star Baseball had developed a following for its thoroughly unique use of past-and-present Major League baseball players—and their real-life statistics—as the essential factors in the game’s development. The architect of this clever concept was another new Cadaco business partner, the former pro ballplayer and future manager of the Yale University baseball team, Ethan Allen.

Allen had played parts of 13 seasons in the big leagues. He was a journeyman outfielder, bouncing between six different clubs, but he was also supremely consistent on the field, finishing with a lifetime .300 batting average. Once a standout student-athlete at the University of Cincinnati, Allen always felt that baseball was supremely lacking in proper resources for instructing young players. Old-timers of the game, as he saw it, were often rigidly unwilling to impart wisdom. So, when Ethan’s playing career ended, he immediately set out into a new role as a teacher and ambassador for baseball. He wrote books on proper fundamentals, directed instructional films for the National League, and shopped around his own original idea for a realistic baseball simulator game for kids.

Allen had played parts of 13 seasons in the big leagues. He was a journeyman outfielder, bouncing between six different clubs, but he was also supremely consistent on the field, finishing with a lifetime .300 batting average. Once a standout student-athlete at the University of Cincinnati, Allen always felt that baseball was supremely lacking in proper resources for instructing young players. Old-timers of the game, as he saw it, were often rigidly unwilling to impart wisdom. So, when Ethan’s playing career ended, he immediately set out into a new role as a teacher and ambassador for baseball. He wrote books on proper fundamentals, directed instructional films for the National League, and shopped around his own original idea for a realistic baseball simulator game for kids.

According to research by SABR, Allen had been developing his board game concept as early as 1936, when he was still an active player. “I had this idea that you could put a man’s playing record on a disc,” he once recalled. “While I was with the Cubs, I went to various manufacturers with the hope of selling the idea to them as a game, only to have most of them practically kick me out of their offices.”

Unfortunately, Cadaco didn’t arrive in Chicago until the year after Ethan Allen’s first pitch meetings. But eventually, the happy marriage of game-designer and game-distributor was realized, as Allen recounted to the Sporting News in 1983.

“[Donald Mazer] was a very direct and straight talking guy,” Allen said. “He listened to me and then blurted out, ‘That’s a good idea, we’ll do it!’ They don’t make people like that anymore. No questions. We just did it.”

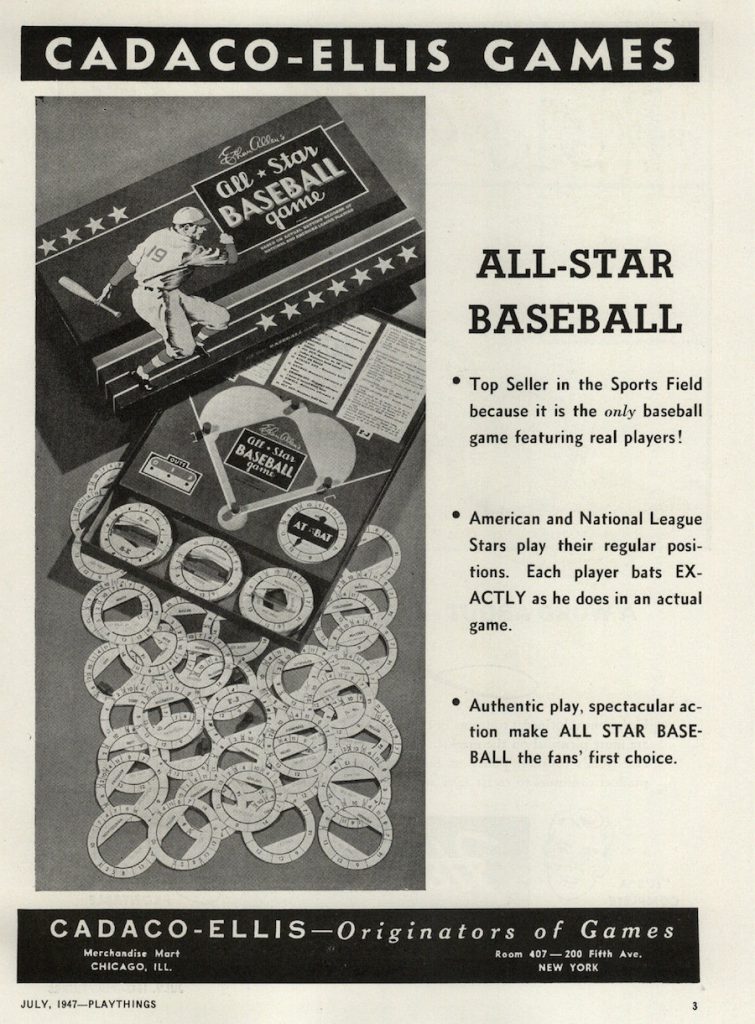

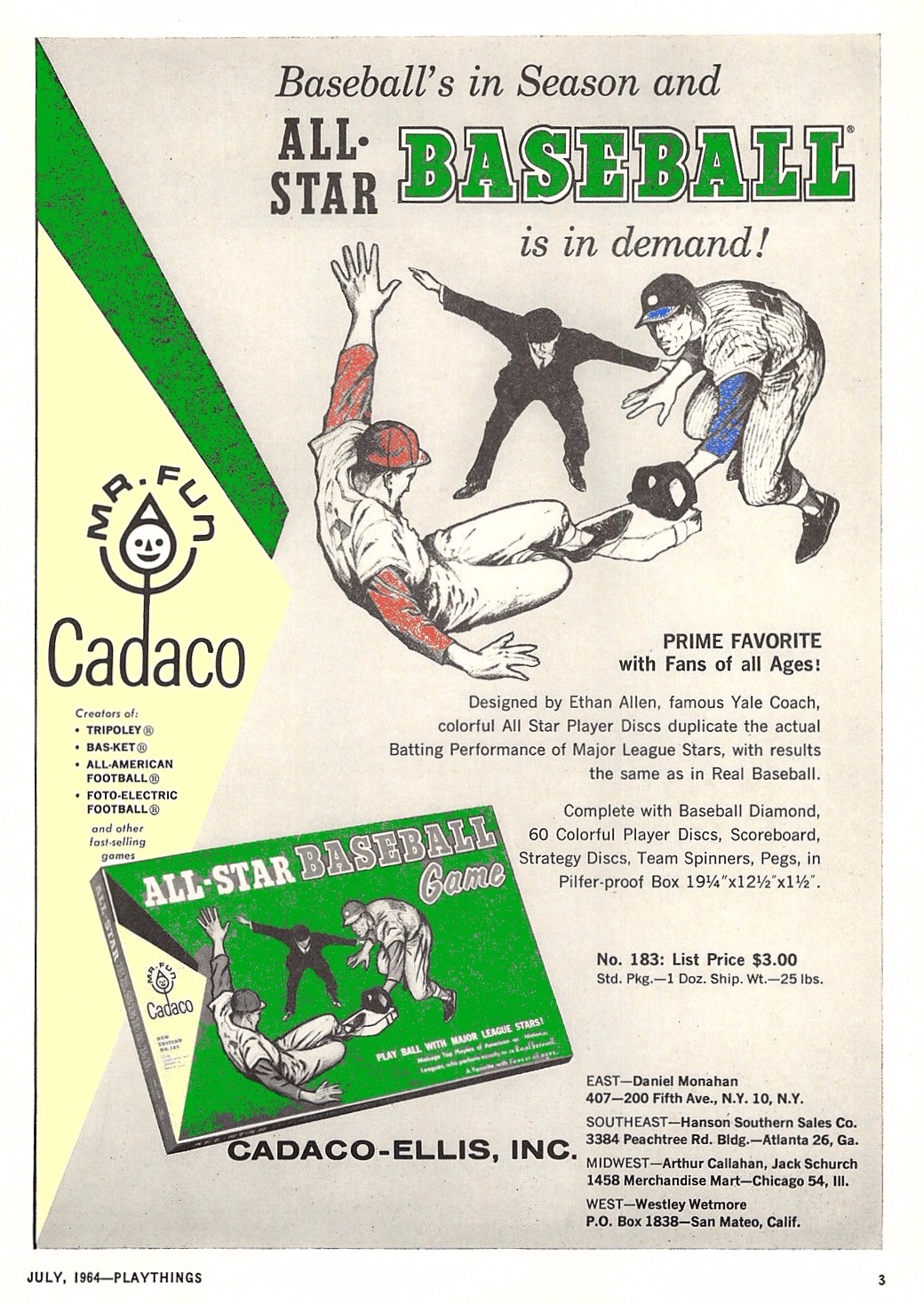

[1964 magazine ad for All-Star Baseball]

[1964 magazine ad for All-Star Baseball]

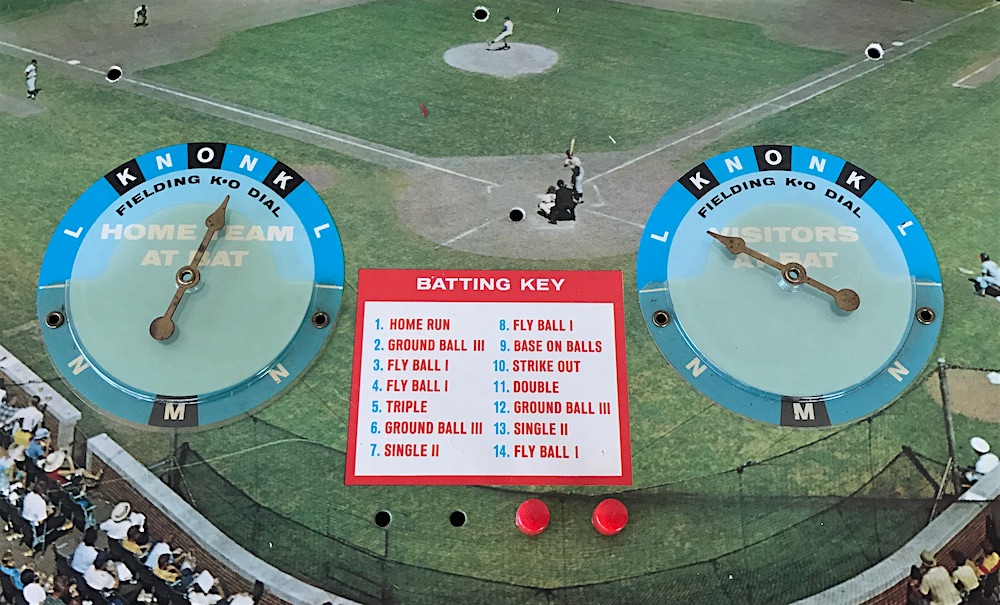

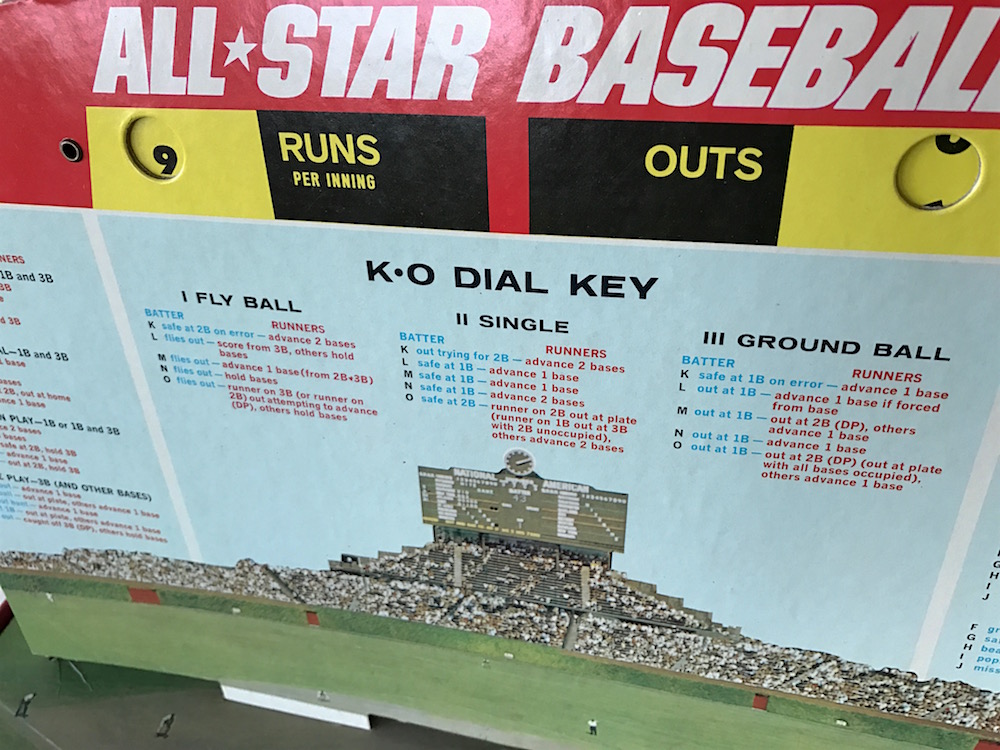

Alternately packaged as “Ethan Allen’s All-Star Baseball Game,” the first box went on sale in 1941 for $1.25. Much like the sports video games of today, it was reproduced just about every year with updated player information. The original box featured 40 MLB stars, each of whom Allen had approached individually to sign a waiver of permission for their name usage. The famous names were then placed on round paper discs, which were marked along the circumference with 14 potential batting outcomes, sort of like a pie chart of probabilities. These discs would then be placed under a spinner, and the landing place of the spun arrow would determine each man’s at-bat.

For a great hitter like Joe DiMaggio, the size of the Single, Double, and Home Run boxes were particularly large, while the strikeout section was a sliver—all reflecting his real-life percentages. For a lesser player, the size of certain pie sections would grow or shrink accordingly, depending on their stats. The system wasn’t perfect—most glaringly, there was no consideration of pitching statistics (Bob Feller may as well have been just some fella)—but nonetheless, the game produced quite realistic results, and its popularity soared. It was on its way to becoming the top selling baseball board game of all time.

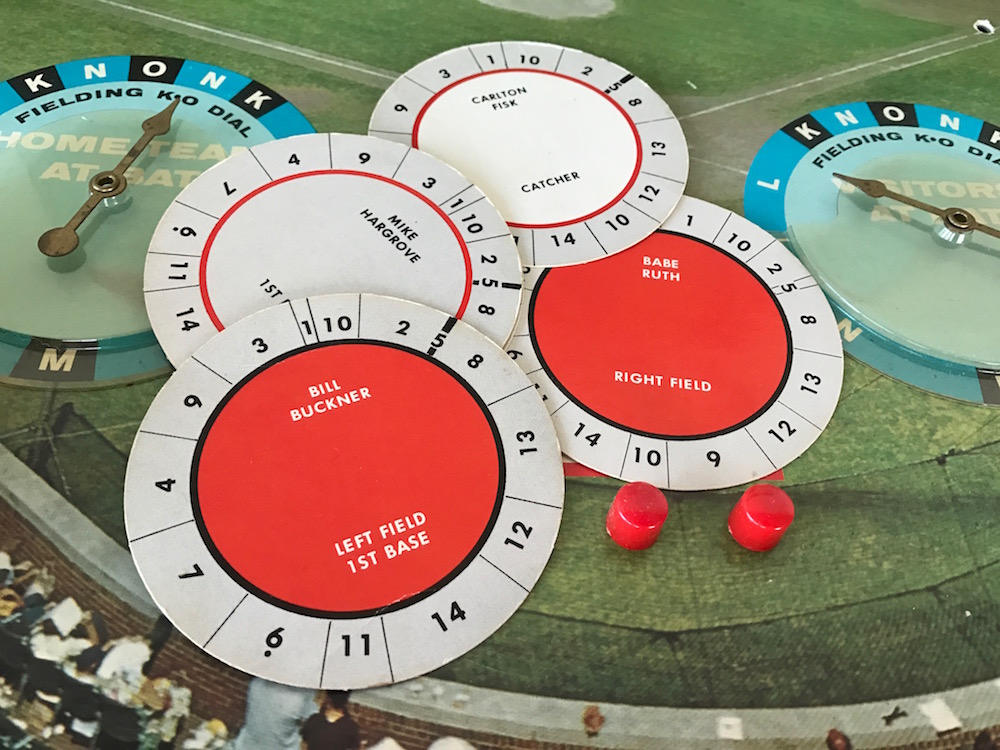

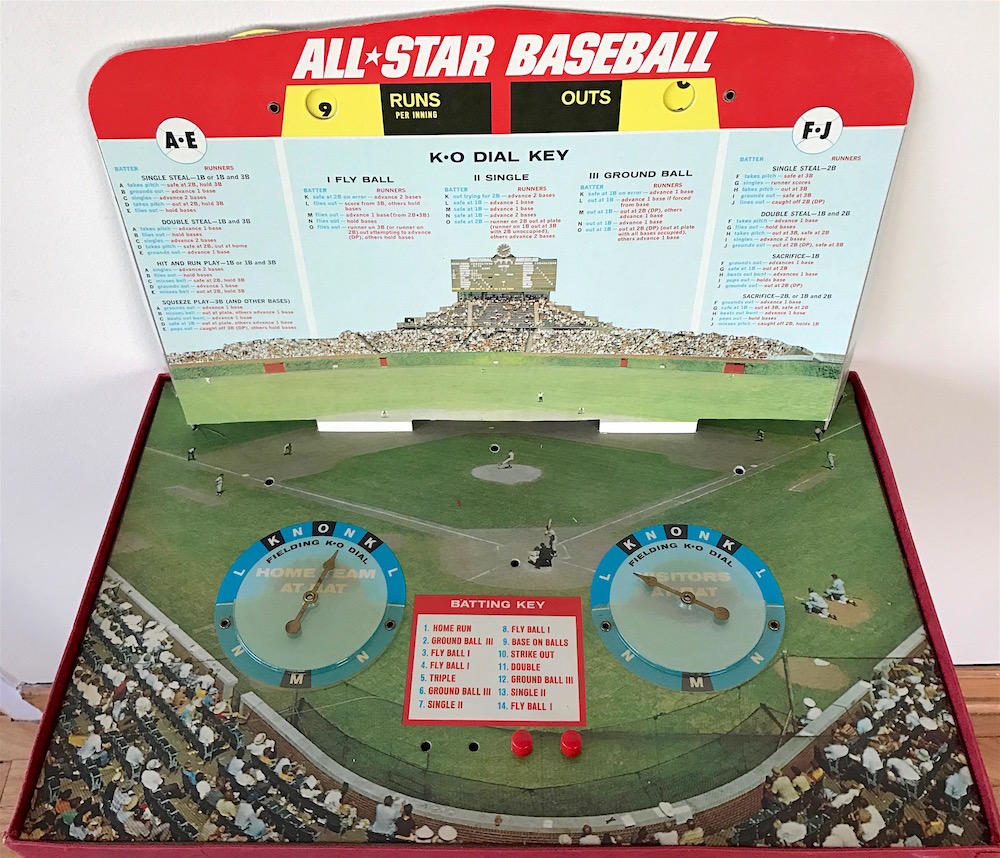

[The ASB game in our collection features a 1968 game board patent, but its player discs feature the updated design, and player names, from later into the 1970s]

[The ASB game in our collection features a 1968 game board patent, but its player discs feature the updated design, and player names, from later into the 1970s]

Even if kids didn’t buy the new All-Star Baseball game board each year, they might seek out the newest player discs, adding the names of new stars or just updating the pie charts for their established favorites.

Over time, the name Ethan Allen became far more associated with the board game than the player himself. . . . Well, actually, the name Ethan Allen was probably more associated with the Revolutionary War figure AND the furniture store than even the board game, but I digress.

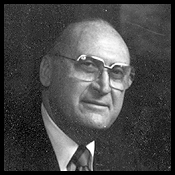

Ten years after All-Star Baseball’s debut, Donald Mazer died suddenly at just 49, leaving his wife as sole owner of Cadaco-Ellis. She elevated Mazer’s former assistant Doug Bolton [pictured] to the role of general manager, and the company powered forward.

In post-war America, Cadaco’s sports games reached all-time highs in popularity, and the company was continuing to find success in other avenues, as well. Though they’d passed on the original Scrabble in another regrettable move, Bolton was able to get the rights to a cardboard version in 1953, which—as part of the agreement—he had to call by a different name, “Skip-Across.” It sold over a million copies in its first year.

During this same era, Cadaco was developing an increasingly tight relationship with its main supplier of cardboard and materials, Chicago’s Rapid Mounting and Finishing Company. In 1959, Doug Bolton actually jumped ship to a better paying gig with Rapid Mounting, but the separation from Cadaco was short lived, as Rapid Mounting actually purchased the game company outright in 1964, installing Bolton as the GM once more, and shortening the brand name back to the original CADACO. The move also soon ended Cadaco’s long residency in the Merchandise Mart, as operations moved to another Marshall Field river warehouse at 310 W. Polk Street during the late ’60s into the ’70s.

[From one giant building to another: Cadaco’s second Chicago headquarters, at the former Marshal Field warehouse at 310 W. Polk St.]

[From one giant building to another: Cadaco’s second Chicago headquarters, at the former Marshal Field warehouse at 310 W. Polk St.]

The late ‘60s also saw the release of our particular museum version of All-Star Baseball, by now having shed Ethan Allen’s name from the title (though he is still name-checked in the footer). Allen was still involved with the game over the years, but he often butted heads with Cadaco about various tweaks he wanted to make to the gameplay. Cadaco had welcomed and integrated some of Allen’s changes in the past, only to have longtime game players riot in disapproval. Mr. Allen—despite his own enthusiasm for fine-tuning his creation well into the his golden years—never quite understood why so many full-grown adults continued to cling to a board game he had always intended for children. Those older obsessos in the growing All-Star Baseball community were simply “odd” to him.

The 1968 All-Star Baseball board design, as you may recognize, introduced an overhead shot of Chicago’s own Wrigley Field as the backdrop. The outside cover of the box, which had usually featured an illustration of a generic cartoon ballplayer in mid-swing, now showed an actual photograph of an unidentified Major Leaguer—seemingly a doctored image of Philadelphia Phillies second baseman Cookie Rojas. The same image would be used on versions of the game for the next several decades, so hopefully Cookie cashed in on that.

Since its inception, All-Star Baseball had always gotten its permission for name usage directly from the players themselves, with no licensing from Major League Baseball. By no surprise, this started posing increasing challenges as time went on. Cadaco largely abandoned the use of famous “old-time” stars after 1968, helping to launch a collector’s market for defunct player cards of Ty Cobb, Rogers Hornsby, and the like. Some die-hards eventually went as far as to design and print their own cards for unrepresented players, something the ultra ASB fanatics still do today.

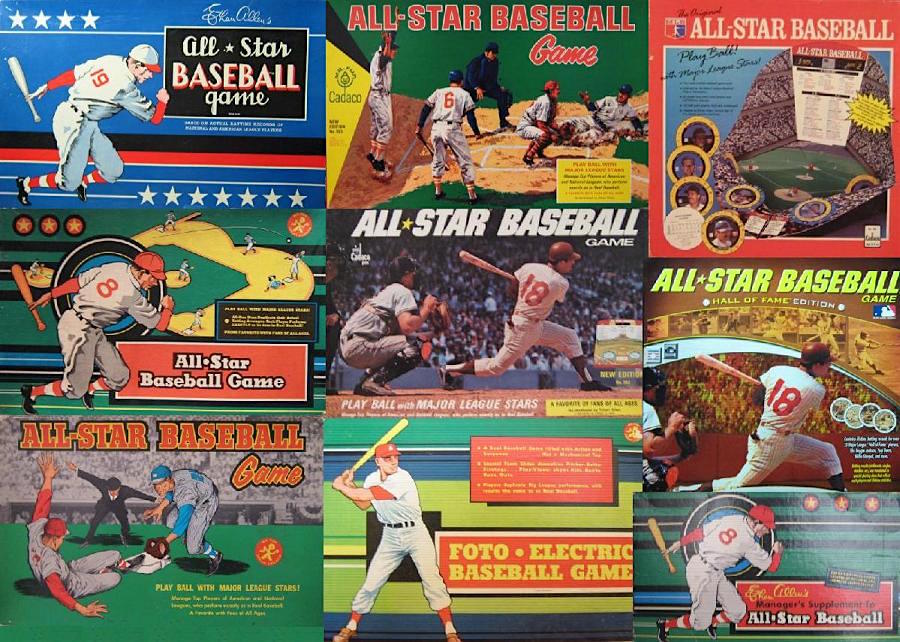

[All-Star Baseball through the ages, a collage courtesy of Spooky’s Hobby Shop]

[All-Star Baseball through the ages, a collage courtesy of Spooky’s Hobby Shop]

The game in our collection is a clear example of how Cadaco updated its player discs each year without necessarily changing the game board itself. This is why a 1968 ASB box can include discs for 1970s players like Mike Hargrove and Bill Buckner. The value was more in the discs than the spinners or playing surface (although you better hope those spinners aren’t defective, or you might have a weird game on your hands).

By the 1970s and ‘80s, board games were under assault not just from this new thing called “video games,” but from a changing culture in general. Cadaco, a company that had once published a “Little Black Sambo” game in its early years, released the well-intended but ill-advised “Martin Luther King, Jr. Game” in 1986. It was a disastrous commercial flop. Better sales came with Cadaco family games like the “Ten Commandments Bible Game,” “Bible Trivia,” and “The Bible Stories Game,” which were all, weirdly enough, about the Bible.

Cadaco was casting a pretty wide net, but the sports games were still its bread and butter in many respects, highlighted by other fine “indoor-recess” favorites like Bas-Ket (a non-strategic basketball game more like cardboard foosball) and All-Star Hockey. Fans of the Cadaco family of games simply kept their eyes peeled for the company’s twisted stick figure mascot, “Mr. Fun”—a character’s whose body literally “spells Cadaco.”

Cadaco was casting a pretty wide net, but the sports games were still its bread and butter in many respects, highlighted by other fine “indoor-recess” favorites like Bas-Ket (a non-strategic basketball game more like cardboard foosball) and All-Star Hockey. Fans of the Cadaco family of games simply kept their eyes peeled for the company’s twisted stick figure mascot, “Mr. Fun”—a character’s whose body literally “spells Cadaco.”

By this point in time, the Rapid Mounting & Finishing Co. offices and its Cadaco division had also settled into a new home at 4300 W. 47th Street in Archer Heights. The building dated back to the 1950s; a late-era addition to the Central Manufacturing District and former home of the National Video Corporation.

[Cadaco’s final home was here at the offices of Rapid Mounting & Finishing, 4300 W. 47th Street. The parent company, now known as Rapid Displays, still owns the building]

[Cadaco’s final home was here at the offices of Rapid Mounting & Finishing, 4300 W. 47th Street. The parent company, now known as Rapid Displays, still owns the building]

At the dawning of the ‘90s, a new boss—a veteran Arkansas businessman named Waymon Wittman—had replaced Doug Bolton at the Cadaco helm, fending off the second wave of video game hysteria from the NES revolution.

“I’ll be honest about it,” Wittman told the Tribune in 1990, “Nintendo has been cleanin’ our plow.”

Wittman’s big solution was to finally pay a bit less attention to the traditional game demographic (kids) and focus on the former kid market—the middle-aged and elderly Americans who’d grown up playing Cadaco games and still had warmth in their hearts for them.

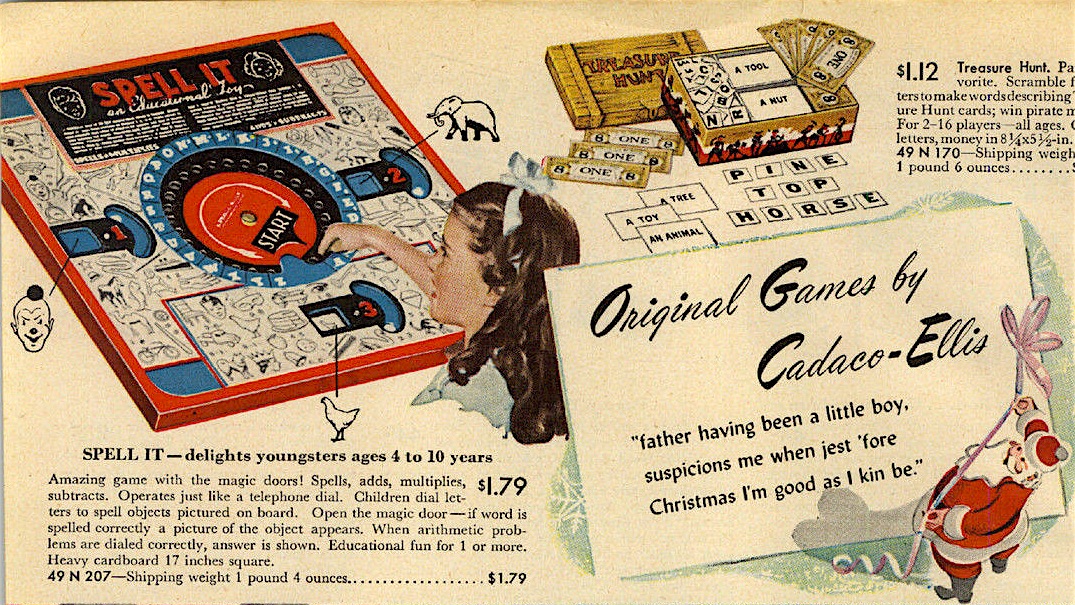

[People who grew up playing Cadaco-Ellis games seen in 1940s ads like this were suddenly the company’s target demographic all over again by the 1990s]

[People who grew up playing Cadaco-Ellis games seen in 1940s ads like this were suddenly the company’s target demographic all over again by the 1990s]

“We were looking for a new niche to get into,” Wittman explained at the time. “We’re a small company and we don’t have a new-product group or a research-and-development staff. But we could see how the mature American population is increasing— 33 million people over the age of 65. And we could compare that with the size of the main toy-buying market, the 18 million kids between the ages of 6 and 11. . . . There’s a huge niche of people out there who grew up in the 1920s or ’30s or ’40s, when they had no TV. They grew up playing games.”

Wittman’s analysis paid off for a while when Cadaco re-released Tripoley and some of its other classic games in new formats, often with bigger print for the cataracts generation. Unfortunately, Wittman’s second prediction—that “video-game hysteria has begun to plateau at last”—proved less prophetic.

[Tripoley was among the classic Cadaco-Ellis that the company relaunched in the early 1990s]

[Tripoley was among the classic Cadaco-Ellis that the company relaunched in the early 1990s]

With the company struggling, a further blow was dealt in 1993, when a tightening down of the Major League Baseball Players Association (ahead of the imminent 1994 players’ strike) led to some new rules about the use of player names in games like All-Star Baseball, which had just celebrated its 50th anniversary. Unable to pay the hefty licensing fees to keep printing discs for the likes of Ken Griffey Jr. and Barry Bonds, Cadaco elected to shut down production of the iconic game. Coincidentally, Ethan Allen died the same year at the age of 89.

Thanks largely to All-Star Baseball’s rapid underground community of collectors and devotees, the game’s legacy survived a 10-year hiatus to briefly resurface in the early 2000s, with a final “Hall of Fame” edition published in 2004.

In 2010, the Cadaco brand—having been pounded into near irrelevance by the internet age—was purchased by the toy company Poof-Slinky. Imagine the indignity of having to hand your life’s work and legacy over to something called “Poof-Slinky.” Not ideal.

And indeed, Poof-Slinky was not kind to the Cadaco name, as the old corporate website soon shutdown and the brand identity was gradually taken almost completely out of circulation on current releases. All-Star Baseball has yet to resurface, as well.

It would appear, after more than 80 years, that the Cadaco tale is officially at an end. But rest assured, wherever stats-loving baseball nerds may dwell, the contributions of this operation shan’t soon be forgotten.

For more on the history of board games, past and present, check out the resources at GameCows.com.

Sources:

Cadaco All-Star Baseball Fan Site

“Cadaco” Company Page at BoardGameGeek.com

Cadaco Patent Registration – 1949

“Ethan Allen” bio at SABR.org by Bernard Crowley

“This Ethan Allen Made Memories, Not Furniture,” at Mastersball.com by Don Drooker

Alan LeMay: A Biography of the Author of The Searchers, by Dan LeMay

“Baseball’s Ethan Allen: The Original Spin Doctor,” by Jack Major

“Cadaco-Ellis and Cadaco” – TheBigGameHunter.com

“Types of Board Games” – GameCows.com

Would love to see Cadaco ‘Tripoley’ playing cards marketed for us ‘purist’ who think Tripoley should be played with Tripoley cards!!! Thanks. p.s. we have worn out every deck everyone at the old folks home had:) .

Just thought I would comment because it’s seriously just too ironic not to. I’m Waymon Wittman’s granddaughter. I’m an avid gamer (and by that I mean video gamer- I’ve been playing video games since I was about 3) and I currently make all of my income with Nintendo.

What years did the box covers have a player sliding?

I purchased a 1949 Foto-electric baseball game at an auction and am looking for the rules to the game. I have had to change out the lightbulb, but need the rules to try it out.

I am 71 now, but as a kid played the game with neighborhood kids. I always won because I had the old heavy Guage cards with great player. Have my own 5 team league.

Bas- Ket and All-Star baseball are the greatest games ever. Wish somebody would start making them again!

What or where is best place to buy some of these games. I still have mine and are in good condition, but i would like to buy some more