Museum Artifact: California Club Seltzer Water Bottle, c. 1930s

Made By: California Ale & Beverage Company, 3006-3030 West Fillmore Street, Chicago, IL [North Lawndale]

The vintage seltzer bottle above was personally donated to the collection by Marc Schulman, a man known to many Chicagoans as the president of Eli’s Cheesecake and the son of one of the city’s great restaurateurs, the late Eli Schulman. The artifact in question, however, comes from the other side of Marc’s family line. His mother Esther—who herself was a leading force behind the Schulmans’ downtown steakhouse (Eli’s, The Place for Steak)—got her first taste of the food and beverage industry in the 1930s, working at her family’s bottling plant on Chicago’s West Side. Since the business and family home were both originally located on California Avenue in the North Lawndale neighborhood, the company went by a potentially misleading name: the California Beverage Co.

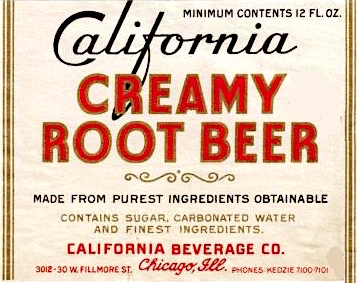

The name stuck even after the plant moved about two blocks west to 3006-30 W. Fillmore Street, where it spent the vast majority of its 30 odd years in operation. Across that time period, from the dawning of the Depression up to the 1960s, California Beverage (sometimes elongated to the California Ale & Beverage Co. when the law permitted it) bottled and delivered a vast array of original beers, soda, sparkling water, root beer, and fruit-flavored novelty drinks. The “All American” brand, which they cleverly managed to trademark in 1941, became a signature of the business during and after the war years, and other experiments—like “Joe Louis Punch”—were cultural touchstones if not financial successes.

The name stuck even after the plant moved about two blocks west to 3006-30 W. Fillmore Street, where it spent the vast majority of its 30 odd years in operation. Across that time period, from the dawning of the Depression up to the 1960s, California Beverage (sometimes elongated to the California Ale & Beverage Co. when the law permitted it) bottled and delivered a vast array of original beers, soda, sparkling water, root beer, and fruit-flavored novelty drinks. The “All American” brand, which they cleverly managed to trademark in 1941, became a signature of the business during and after the war years, and other experiments—like “Joe Louis Punch”—were cultural touchstones if not financial successes.

You can still find the occasional antique bottle of All American Orange Soda or California Creamy Root Beer floating around. But a big 26-ounce siphon-style soda water bottle like the “California Club” in our collection is a rarer find. Likely dating from the late 1930s, this heavy glass model was used by a soda jerk to keep a beverage sealed and carbonated (or “cabonated,” based on the unfortunate misspelling on the California Club’s label). Pressing the lever on the metal bottle top would then dispense the bubbly refreshment—or spray someone in the face if you were in a Three Stooges movie.

From Kiev to “California”

The aforementioned Esther Schulman (1918-2009) was the daughter of Isadore and Sadie Nettis—Jewish immigrants who fled Ukraine for the U.S. when they were both just teenagers themselves. Isadore Nettis (1885-1959) arrived in 1903, and Sadie Goodman (1888-1978) in 1906. The young couple married in Chicago in 1908 and soon started a family in an apartment at 2139 W. 12th Street. Initially, Isadore worked as a press operator in a factory to make ends meet, but by the beginning of the first World War, the Nettises were running a grocery out of the same building they lived in.

During this same period, Sadie’s extended family, including her brother Solomon “Sol” Goodman, joined her in Chicago, creating an expanded, tight-knit family unit in their largely Jewish neighborhood.

Sol Goodman—or as I like to call him, the original “Better Call Sol”—was just 16 when he came to Chicago in 1913, but he quickly embraced his new homeland. By 1918, despite speaking far more Yiddish than English, he became a private in the U.S. Army—Company E, 132nd Infantry—and headed to France aboard the USS Mt. Vernon to join the war effort. It was a return trip across the Atlantic that Sol hadn’t bargained for, but fortunately he lived to tell about it, arriving safely back in Chicago in the spring of 1919. From there, he started working as a delivery truck driver for a bottling company, and—one can presume—learned enough to determine he could run a comparable business himself.

At some point in the late 1920s, Goodman organized the California Beverage Company, relying on the experience of the older/wiser Isadore and Sadie to help him operate the enterprise. To either simplify or complicate matters, he also moved in with the couple and their four kids. Some early ads and newspaper clips set the business’s address at 1142 S. California Avenue, which was, in fact, the Nettis family home. It’s unclear if the house was just doubling as an office, or if Uncle Sol was literally capping bottles downstairs while young Esther and her siblings were doing their homework upstairs. Either way, it was a humble beginning.

[Left: A Knight Club Lager Beer label noting the “California Ale & Beverage Co.” at 1137-41 S. California Ave. Right: Same label, but now shortening the bottler name to the “California Beverage Co.,” with a new address on W. Fillmore Street. The Ale was likely briefly added to the name after the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, then removed again later in the ’30s]

[Left: A Knight Club Lager Beer label noting the “California Ale & Beverage Co.” at 1137-41 S. California Ave. Right: Same label, but now shortening the bottler name to the “California Beverage Co.,” with a new address on W. Fillmore Street. The Ale was likely briefly added to the name after the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, then removed again later in the ’30s]

Crime Times

Even 80 years ago, North Lawndale wasn’t always the safest place to live or run a business. And since a bottling company wasn’t going to grab newspaper headlines for merely making on-time deliveries, a lot of surviving press about the California Beverage Company involves its repeated, unfortunate run-ins with the city’s criminal element.

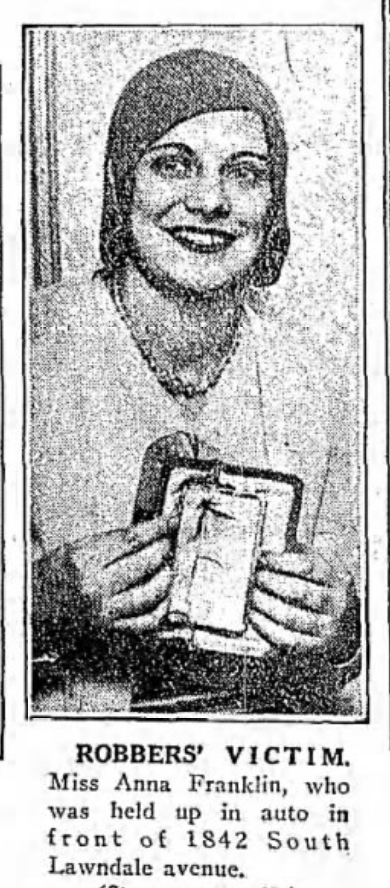

July 30, 1929 – Even as a war veteran, Uncle Sol probably got more than a small fright on July 29 of 1929, when he and a female companion were robbed and carjacked at gunpoint about two miles from the California Beverage headquarters.

July 30, 1929 – Even as a war veteran, Uncle Sol probably got more than a small fright on July 29 of 1929, when he and a female companion were robbed and carjacked at gunpoint about two miles from the California Beverage headquarters.

“Solomon Goodman, 31 years old, head of the California Beverage Company, 1142 South California avenue, and Miss Anna Franklin, 27 years old, 3953 West Van Buren Street, were held up by two robbers as they sat in Goodman’s car in front of a friend’s home at 1842 South Lawndale avenue,” the Tribune reported. “The robbers forced Goodman to drive into an alley around the corner where they took $251 from him and a $250 ring from his companion before ejecting the pair from the car and driving away in it.”

“Solomon Goodman, 31 years old, head of the California Beverage Company, 1142 South California avenue, and Miss Anna Franklin, 27 years old, 3953 West Van Buren Street, were held up by two robbers as they sat in Goodman’s car in front of a friend’s home at 1842 South Lawndale avenue,” the Tribune reported. “The robbers forced Goodman to drive into an alley around the corner where they took $251 from him and a $250 ring from his companion before ejecting the pair from the car and driving away in it.”

Weird that Sol knew he had exactly 251 bucks on him. Also weird that his gal pal Anna smiled for the camera when displaying her newly emptied pocketbook.

Anyway, this wouldn’t be the last time Goodman would be victimized by thieves. Even the big brick California Beverage factory on Fillmore Street was far from impervious to prowlers—though they didn’t always get what they were after.

![]() December 5, 1941 – “Two bandits who bound and gagged Stanley Pawlowski, 58 years old, night watchman at the California Beverage Company, 3030 Fillmore Street, ransacked the plant but apparently took only 50 cents and a 35 caliber revolver, plant officials reported yesterday.”

December 5, 1941 – “Two bandits who bound and gagged Stanley Pawlowski, 58 years old, night watchman at the California Beverage Company, 3030 Fillmore Street, ransacked the plant but apparently took only 50 cents and a 35 caliber revolver, plant officials reported yesterday.”

That one put Goodman and the Nettises on edge, but the bombing of Pearl Harbor two days later likely redirected their concerns.

[The former California Beverage plant at 3030 W. Fillmore Street, still standing today and still taunting would-be crooks]

[The former California Beverage plant at 3030 W. Fillmore Street, still standing today and still taunting would-be crooks]

August 26, 1949 – “Returning from a false burglar alarm at 1019 S. Sacramento Ave. early yesterday, a Marquette police squad discovered another burglary at the California Beverage company, 3030 Fillmore street. Someone had broken in and stolen two office safes, which the owner, Sol Goodman, said contained about $5,000. One of the safes was found broken open in another part of the building.”

August 26, 1949 – “Returning from a false burglar alarm at 1019 S. Sacramento Ave. early yesterday, a Marquette police squad discovered another burglary at the California Beverage company, 3030 Fillmore street. Someone had broken in and stolen two office safes, which the owner, Sol Goodman, said contained about $5,000. One of the safes was found broken open in another part of the building.”

October 24, 1951 – Of all the various factory break-ins, this one wins the prize for being the most intense and nearly tragic.

October 24, 1951 – Of all the various factory break-ins, this one wins the prize for being the most intense and nearly tragic.

“One of three men who attempted to hold up the California Beverage company, 3030 Fillmore st., last night, pointed a revolver at Walter Wilson, 46, of 415 S. Homan ave., traffic manager, and pulled the trigger twice. The weapon failed to discharge.

“Wilson came upon the robbers as they were scuffling with Harry Goodman, a watchman [unclear if this man was related to Sol Goodman]. The bandits fled in a 1941 automobile which was curbed by police at Troy st. and Douglas blvd., after a chase in which six shots were fired.”

October 29, 1940 – Technically speaking, the California Beverage Company was also once accused of breaking the law in its own right—although it hardly involved theft or gunfire. Apparently, in 1940, it was illegal to transport drinks across state lines into Indiana if they contained the sugar substitute saccharin.

October 29, 1940 – Technically speaking, the California Beverage Company was also once accused of breaking the law in its own right—although it hardly involved theft or gunfire. Apparently, in 1940, it was illegal to transport drinks across state lines into Indiana if they contained the sugar substitute saccharin.

As reported in The Times of Munster, Indiana: “City Judge Joseph V. Stodola, Jr. of Hammond yesterday denied a motion to quash a state food and drug law violation charge against the California Beverage company, 3012 West Fillmore street, Chicago.

“A criminal summons was procured against the firm by Robert Prior, health inspector, who contends that tests by City Chemist A. W. Ecklund show that a sample of the company’s pop, purchased on Sept. 30, contained saccharine. Use of the artificial sweetening is prohibited by law.

“A criminal summons was procured against the firm by Robert Prior, health inspector, who contends that tests by City Chemist A. W. Ecklund show that a sample of the company’s pop, purchased on Sept. 30, contained saccharine. Use of the artificial sweetening is prohibited by law.

“Attorney Benjamin Saks of Gary, representing the firm, contended that the firm’s operations are inter-state and not intra-state. Judge Stodola maintained that the firm is charged with selling the product locally.”

Saccharin was one of those boogeyman substances that was eventually proved pretty harmless to human consumption. Nonetheless, Sol Goodman had another headache on his hands.

Drink All American!

Robberies and saccharin violations aside, the 1940s were, in some respects, the golden years of the California Beverage Co. As the second generation of the Goodman / Nettis family began to contribute to the business, the story became a case study in the American dream realized. By now, the full-scale plant was up and running on Fillmore Street, and a fleet of drivers carried the California Beverage Co. name across the Midwest.

Robberies and saccharin violations aside, the 1940s were, in some respects, the golden years of the California Beverage Co. As the second generation of the Goodman / Nettis family began to contribute to the business, the story became a case study in the American dream realized. By now, the full-scale plant was up and running on Fillmore Street, and a fleet of drivers carried the California Beverage Co. name across the Midwest.

Being Jewish certainly posed its challenges in Chicago as it did in most other American cities, but as events in Europe erupted into World War II, many Jewish communities in the U.S. took the lead in celebrating the comparative freedom and opportunity that America represented. Sol Goodman and Isadore Nettis were no exception, successfully applying for a trademark in 1941 for their new brand of original sodas: the “All American” beverages.

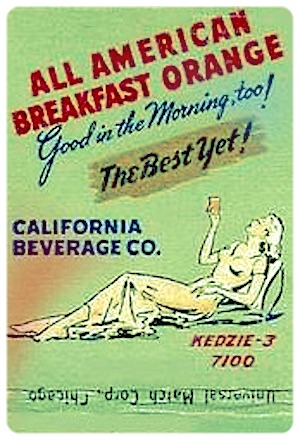

[This advertisement in 1940, shortly before Sol Goodman somehow trademarked the brand “All American” for his new line of California Club Sodas]

[This advertisement in 1940, shortly before Sol Goodman somehow trademarked the brand “All American” for his new line of California Club Sodas]

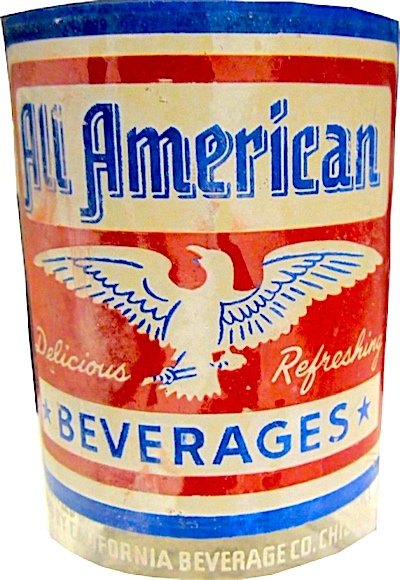

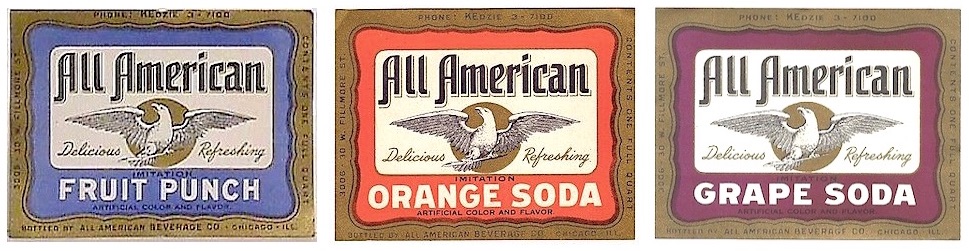

All American drinks featured a couple of different logo motifs, each dripping with patriotic pride. There was the obligatory eagle, perched on the labels of the company’s fruit flavored sodas in between the words “delicious” and “refreshing.”

Then there was the saluting soldier, centered on a red, white, and blue shield. The associated slogan, “Drink All American!”, was an authoritative command right off an Uncle Sam poster. It might be hard to say how drinking All American Fruit Punch would directly help the boys overseas, but the sentiment, nonetheless, was appreciated. The brands sold well.

Then there was the saluting soldier, centered on a red, white, and blue shield. The associated slogan, “Drink All American!”, was an authoritative command right off an Uncle Sam poster. It might be hard to say how drinking All American Fruit Punch would directly help the boys overseas, but the sentiment, nonetheless, was appreciated. The brands sold well.

The California Beverage Co. became so associated with its All American drinks, in fact, that the company developed a second working identity in the late ‘40s and early ‘50s, listed on certain labels and advertisements as the “All American Beverage Co.” This name is used on the colorful labels below, with the 3006-3030 Fillmore Street address providing evidence that this was, indeed, the same business.

[Soft drinks produced by the California Beverage Co. under its occasional pseudonym, the All American Beverage Co., 1940s]

[Soft drinks produced by the California Beverage Co. under its occasional pseudonym, the All American Beverage Co., 1940s]

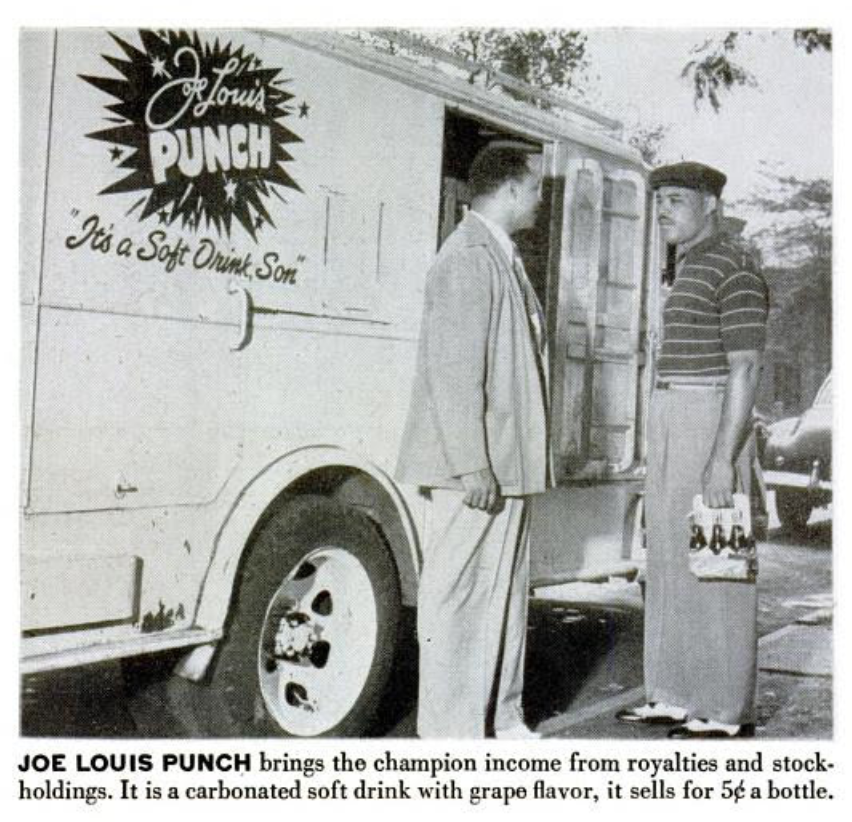

Unfortunately, trying to pin down the dividing line between the California Beverage Co. and its All American alter ego gets a little more complicated when you consider the saga of a little soda pop called Joe Louis Punch.

“Greatest Bottle of All Time”

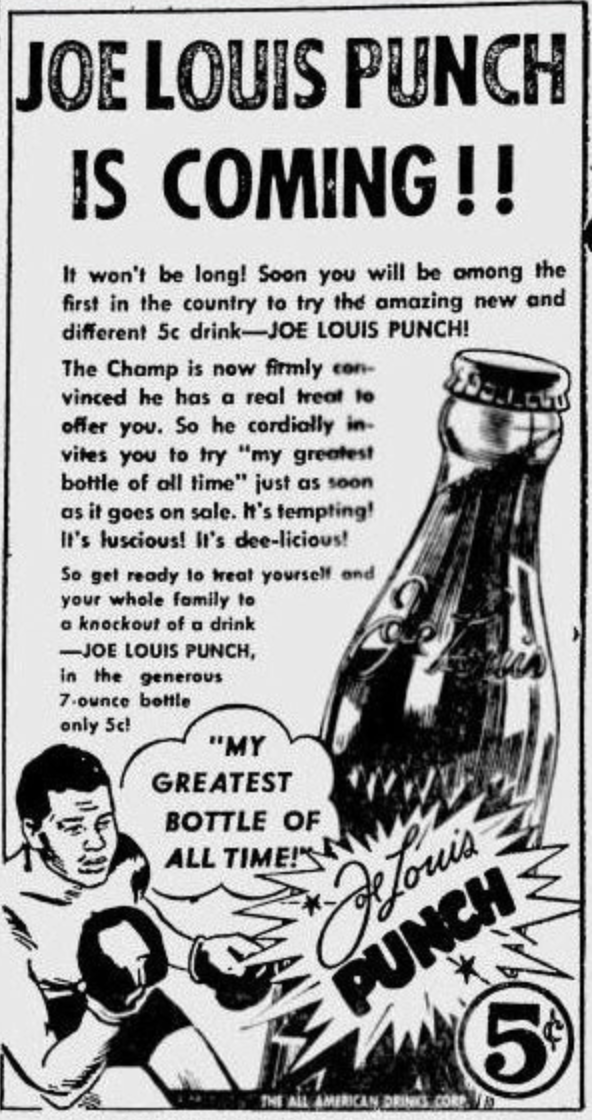

In 1946, a New York City ad agency executive named William B. Graham organized a new company called the All American Drinks Corporation, solely for the purpose of selling the first soft drink officially licensed by the world’s most famous boxer.

In 1946, a New York City ad agency executive named William B. Graham organized a new company called the All American Drinks Corporation, solely for the purpose of selling the first soft drink officially licensed by the world’s most famous boxer.

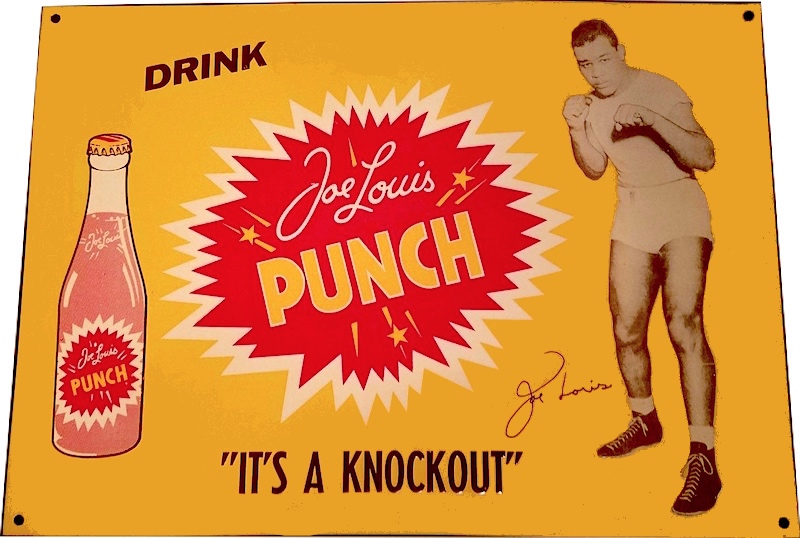

Graham was an underground legend himself—one of the great marketing men of the 1940s. As an African American, he was also a pioneer in his industry, helping to introduce a new wave of promotional strategies directed at the modern interests of the black community. This reputation helped him to convince the great Joe Louis to lend his name and likeness—and a financial investment—to the new grape soda that would become “Joe Louis Punch.” Legendary musicians Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway invested in the product, as well, and even performed a theme song that ran as part of the radio campaign.

It’s unclear if William Graham chose the name “All American Drinks Corp” for his business as a conscious connection to Sol Goodman’s existing All American brand in Chicago. But one thing is clear—the California Beverage Co. plant on Fillmore Street started producing and distributing Joe Louis Punch to the local market shortly thereafter. There may have been a deeper business connection between the two entities, as well.

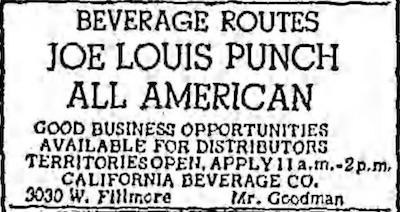

[A California Beverage Co. ad in the Tribune classifieds, calling for drivers to deliver Joe Louis Punch and All American drinks, 1948]

[A California Beverage Co. ad in the Tribune classifieds, calling for drivers to deliver Joe Louis Punch and All American drinks, 1948]

In 1949, Sol Goodman is listed by Illinois’s Certified List of Domestic and Foreign Corporations as not only the president of the California Beverage Co., but also a separate firm called All American Beverages, Inc.—based out of a a downtown office at 33 N. Lasalle Street. His co-officers are listed as Irving Gertler and Arthur S. Freeman. We can presume this was simply a sales and marketing division of the California bottling business, but it’s also possible this it was a direct Chicago affiliate of Graham’s All American Drinks Corp. in New York.

If anyone can help connect or un-connect these various All American dots, we certainly welcome you to do so via the comments or contact page.

In any case, Joe Louis Punch got off to a great start in Chicago and everywhere else, as the face of the “Brown Bomber” alongside his pink soda was hard to miss. In a 1948 interview with Life magazine, Louis discussed the drink among his sources of income in the event that he decided to give up the fight game (his last fight would come three years later).

“I’ve got Joe Louis Enterprises, Inc. going good and I’ve got an interest in the Joe Louis Punch,” he said. “That’s a soft drink that’s selling good in 31 cities and in South America. I’ve got $25,000 stock in it and I get 5% in royalties. I may build myself a bottling and distribution plant and sell Joe Louis Punch myself. . . . When people say Joe Louis is broke, that’s just talk. If I don’t have ready cash I have other things to see me through.”

But in fact, the rumors of the champ’s financial struggles were true, and his interest in trying to bottle Joe Louis Punch himself was likely motivated by seeing just how much of his money ended up going to third-party distributors like the California Beverage Company.

But in fact, the rumors of the champ’s financial struggles were true, and his interest in trying to bottle Joe Louis Punch himself was likely motivated by seeing just how much of his money ended up going to third-party distributors like the California Beverage Company.

As Louis started to lose money on the investment, it also meant he couldn’t afford to fund any improvements to the drink itself—which was starting to get the wrong kind of reputation. According to Jason Chambers’ book, Madison Avenue and the Color Line: African Americans in the Advertising Industry, “over time, [Joe Louis Punch] developed quality issues that no amount of advertising or promotion could overcome. A former salesman recalled that when exposed to sunlight the soda pop lost its color, and when combined with ice it lost most of its aroma.”

Joe Louis Punch was discontinued by the early 1950s, and in Chicago, Sol Goodman and Isadore Nettis went back to focusing on their All American brands.

Have Your Cake, Too

During those Joe Louis Punch days, there was another, more lasting addition to the Goodman / Nettis clan. Esther Nettis started dating a charming mess sergeant named Eli Schulman after the war ended, and by 1948, they were married. From there, using some of her own know-how from the bottling business and her training as an accountant, Esther helped Eli run a neighborhood grill up north in Uptown at the corner of Argyle and Sheridan, called Eli’s Ogden Huddle.

The restaurant gained a loyal following in the 1950s, but things were not as rosy back in North Lawndale. Esther’s older brother Morris died in 1955 at just 45, and the family patriarch, Isadore Nettis, passed in 1959 at 74. The following year, newspaper classified ads show the California Beverage Co. still in operation on Fillmore Street, but the business appears to have been dissolved shortly thereafter, predating the death of founder Sol Goodman in 1967. The last original connection to the founding of the business, Sadie Nettis, died in 1978.

[Eli and Esther Schulman’s first restaurant, Eli’s Ogden Huddle, at Sheridan and Argyle St. in Uptown, 1940s]

[Eli and Esther Schulman’s first restaurant, Eli’s Ogden Huddle, at Sheridan and Argyle St. in Uptown, 1940s]

As the bottling business came to an end, though, the Schulmans’ restaurant endeavor reached new heights. In 1962, Eli and Esther decided to take a risky leap and open a new place in a more competitive part of town. Eli’s Stage Delicatessen joined the Rush Street restaurant hub, soon drawing rave reviews and some all-star clientele (Barbra Streisand and Woody Allen among them). Along with serving up good grub, Eli Schulman could schmooze with the best of ‘em, and it made his place a desirable hangout.

Four years later, looking to fulfill Eli’s dream of running a more upscale establishment, a new restaurant—Eli’s the Place for Steak—opened inside the Carriage House hotel on Chicago Avenue in Streeterville. It became yet another beloved institution, standing for nearly 40 years and famously birthing the cheesecake that wound up becoming a business unto itself. Much of the credit for the success goes to Esther Schulman, who took a lead role running both operations after the death of Eli Schulman in 1988.

Four years later, looking to fulfill Eli’s dream of running a more upscale establishment, a new restaurant—Eli’s the Place for Steak—opened inside the Carriage House hotel on Chicago Avenue in Streeterville. It became yet another beloved institution, standing for nearly 40 years and famously birthing the cheesecake that wound up becoming a business unto itself. Much of the credit for the success goes to Esther Schulman, who took a lead role running both operations after the death of Eli Schulman in 1988.

Today, Marc Schulman runs Eli’s Cheesecake Chicago in the Dunning neighborhood, distributing his delicious goods to the people, just as his grandparents once did with their All American bottled beverages. It’s a lesser known legacy, but one represented in this old California Club seltzer bottle—a relic with plenty of bottled up stories to tell.

[Esther, Marc, and Eli Schulman at the Taste of Chicago, 1985]

[Esther, Marc, and Eli Schulman at the Taste of Chicago, 1985]

Sources

“Joe Louis’ Story” – Life Magazine, November 15, 1948

“Army of 40 Marketing Men Make Negro Buyers More Brand Conscious” – Ebony, May 1948

Madison Avenue and the Color Line: African Americans in the Advertising Industry, by Jason Chambers

“Court Rules in Beverage Case” – The Times (Munster, Indiana), Oct. 29, 1940

“Soda and Mineral Water Bottles” – Society for Historical Archeology

“Esther N. Schulman, 1918-2009: Dynamic Businesswoman Played Key Role in Husband Eli’s Restaurant, Cheesecake Business” – Chicago Tribune, Sept 2, 2009

Hello

I am a Chicago guy with a long time love of anything made in Chicago. Loved this article, especially since I have one of the earliest etched glass seltzer bottles made by California Beverage having their original California Ave address. If interested, I can send you photo’s of this beautiful original 1920’s bottle and original nozzle top.

Dave Apostal (dwapostal@gmail.com)

Thank you for this great background story. We actually just bought today this exact vintage seltzer bottle today at a swap meet in California! I found your story because I was curious about the Jewish star on the back of the bottle. Did they put this on the back of all their bottles? Do you know the significance of the writing around the Jewish star? I look forward to hearing from you.