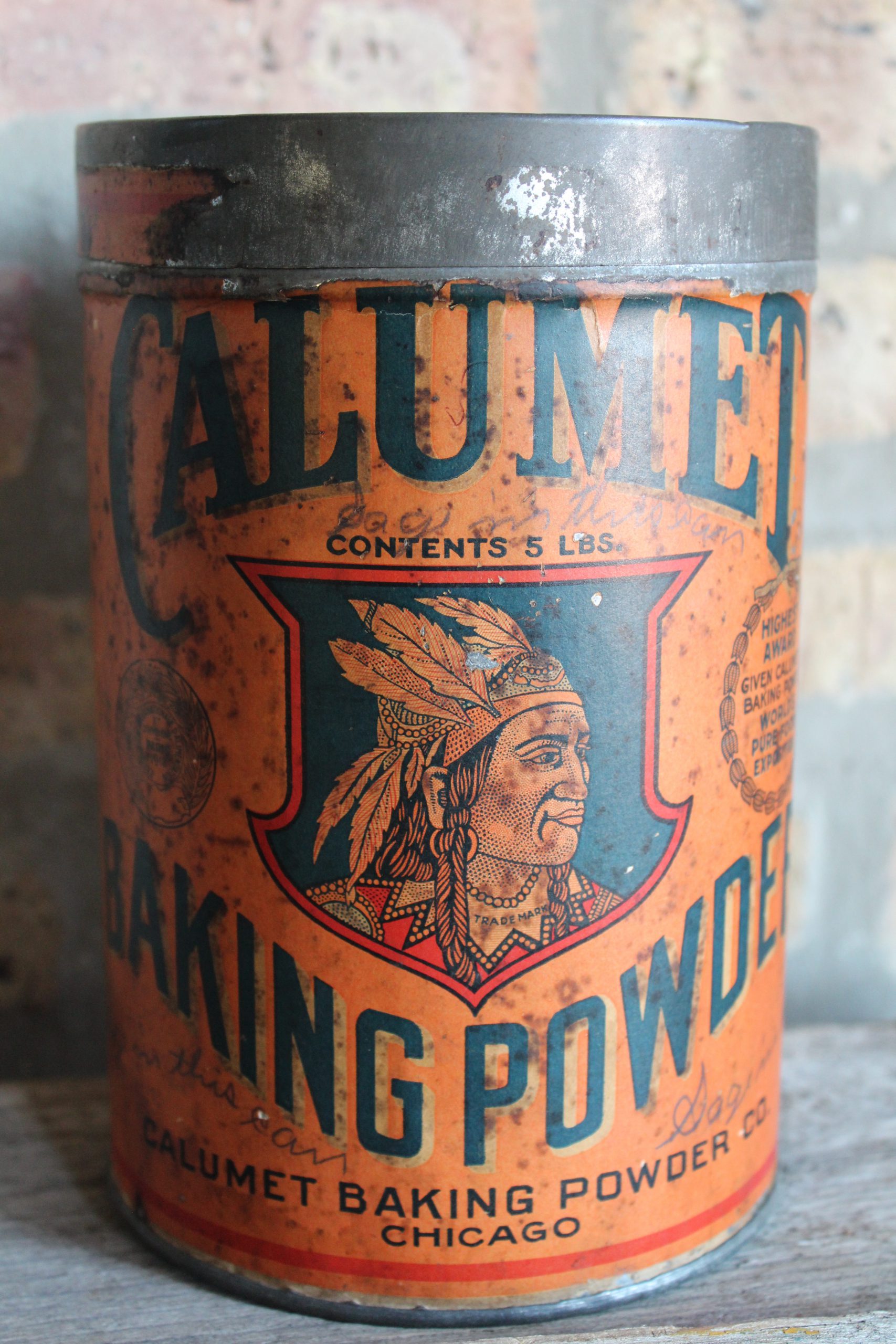

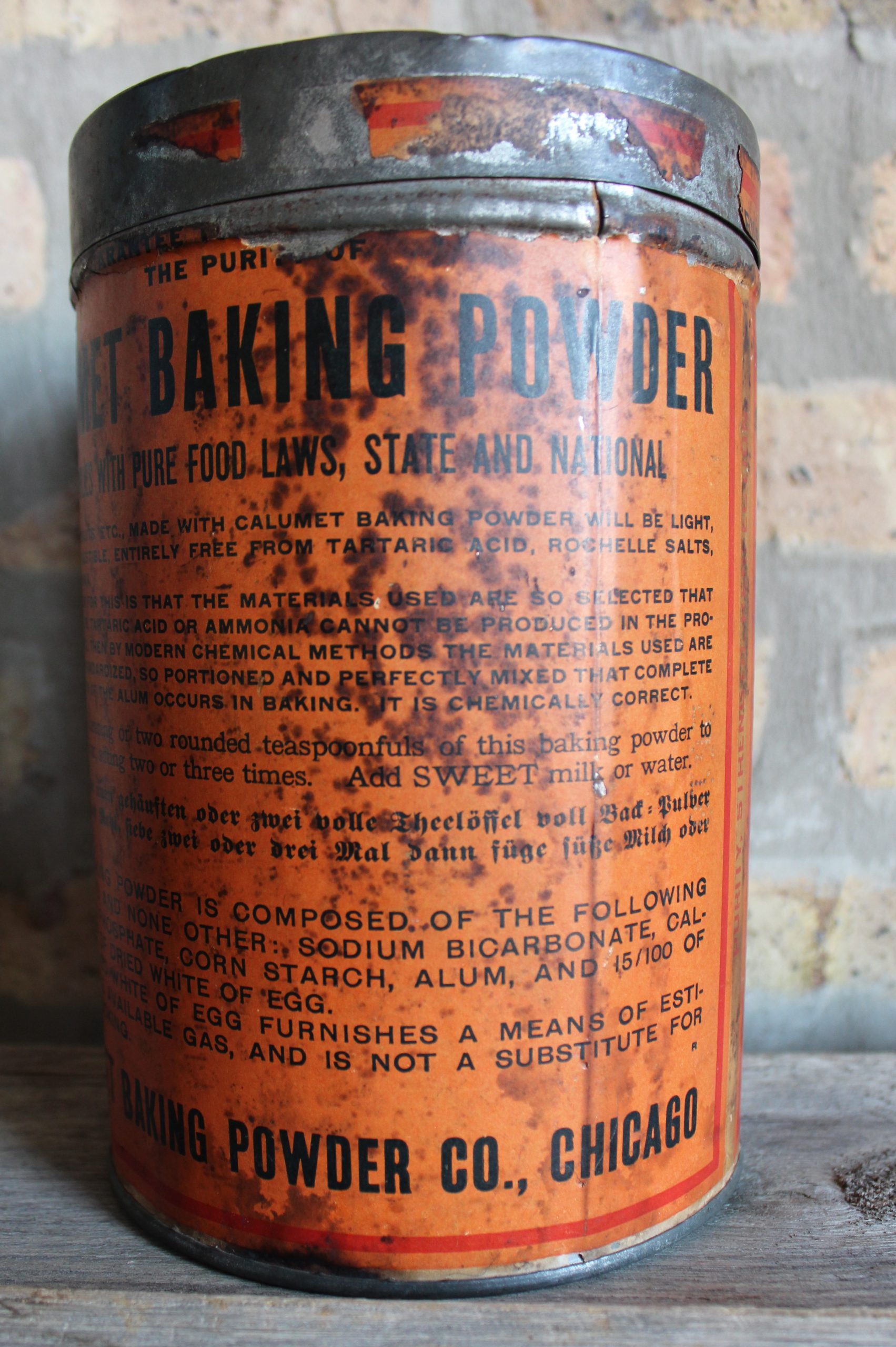

Museum Artifact: Calumet Baking Powder Tin, c. 1913

Made By: Calumet Baking Powder Co., 4100 W Fillmore St., Chicago, IL [North Lawndale]

This five-pound canister of Calumet Baking Powder might seem like a cute artifact from a old-timey diner or a small town general store, but make no mistake, you’re looking at a relic from a war . . . the Baking Powder War.

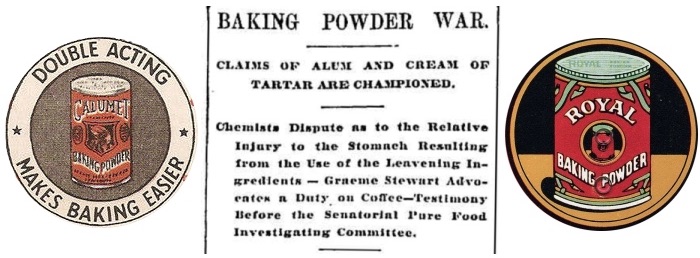

Today, a “baking powder war” might happen when a group of unruly kids is left unattended in a cafeteria kitchen. But for a 40-year period from the 1880s through the 1920s, the phrase was used liberally to describe the very real, very vicious feud between the two presiding schools of thought in the commercial baking powder business: Cream-of-Tartar Formula (aka, the establishment) vs. Alum-Phosphate Formula (the rebels). Whether you were a chemist, a baker, a merchant, a restaurateur, or a marginalized turn-of-the-century housewife, everyone had to pick a side.

Today, a “baking powder war” might happen when a group of unruly kids is left unattended in a cafeteria kitchen. But for a 40-year period from the 1880s through the 1920s, the phrase was used liberally to describe the very real, very vicious feud between the two presiding schools of thought in the commercial baking powder business: Cream-of-Tartar Formula (aka, the establishment) vs. Alum-Phosphate Formula (the rebels). Whether you were a chemist, a baker, a merchant, a restaurateur, or a marginalized turn-of-the-century housewife, everyone had to pick a side.

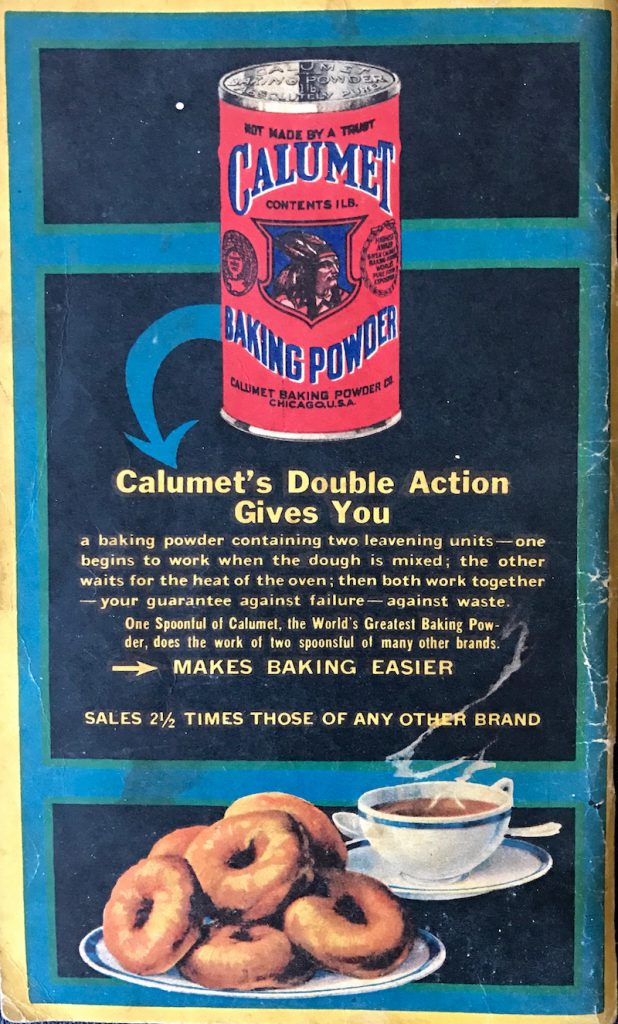

Chicago’s Calumet Baking Powder Company, to the benefit of our story, aligned with the underdogs of the new school, being among the first American manufacturers to embrace the aluminum-phosphate trend in the late 1880s. Few denied that Calumet’s ingredients—which also included the unique addition of dried egg whites—created superior results in the kitchen. Their trademark “double-action leavening” effect started in the mixing bowl and concluded in the oven for a “perfectly baked cake.” Unfortunately, the industry’s old guard—led by the Royal Baking Powder Company of New York—weren’t interested in simply conceding to progress.

As purveyors of the more expensive and less effective cream-of-tartar powder, Royal was doomed if alum-and-eggs became the new standard. So—as any good upstanding company would do—they began a merciless, unyielding propaganda campaign against Calumet and all other alum brands (including Chicago’s Crown Baking Powder). This included going as far as to bribe state congressmen to introduce anti-alum legislation, citing bogus health risks. Many congressmen obliged, of course, because politicians are consistent across history.

Media outlets picked up the story, as well, and soon much of the public was convinced that so-called alum powders could put them in the hospital, even though the very nature of baking powder (i.e., the baking process) eliminated virtually any trace of alum from the consumable food itself.

[The phrase “Baking Powder War” can be found as far back as 1884, while the excerpt above comes from a Chicago Tribune article in 1899]

[The phrase “Baking Powder War” can be found as far back as 1884, while the excerpt above comes from a Chicago Tribune article in 1899]

“There is no question about the poisonous effect of alum upon the system,” read one of Royal’s advertisement, subtly titled Is It Malaria or Is It Alum? The product was “so highly injurious to the health of the community” the ad continued, that its sale “should be prohibited by law.”

If Calumet was going to survive this onslaught, it would have to find a way to navigate a minefield of misinformation while also creating a positive public image. Fortunately, the company had the right combination of minds up to the task.

I: The Wright Stuff

Calumet’s founder, William Monroe Wright, was born in Dayton, Ohio, in 1851. He was the son of a miller and presumably destined for a humble working class life, but somewhere along the line, he picked up a persistent ambitious streak. It’s a trait that might have even rubbed off on his much younger cousins, fellow Dayton boys Orville and Wilbur. William Wright’s destiny wasn’t in the skies, however. His great future awaited him on the battlefields of baking powder.

The wheels were set in motion during a whirlwind period in his mid 20s, when Wright got married, had a son, and lost both of his parents. With his life turned upside down, he decided to move the family from their rural Springfield, Ohio home and head for the city—starting with Indianapolis. Through some bit of randomness, he got a gig selling Dr. Price’s Baking Powder, a popular brand at the time (invented—amusingly enough—by the grandfather of the actor Vincent Price). Wright became the star of the regional sales team in Indy—perhaps even to his own surprise—and he used his new reputation to lock down a better paying gig in Chicago. His new employer? None other than his future nemesis, the Royal Baking Powder Co.

The wheels were set in motion during a whirlwind period in his mid 20s, when Wright got married, had a son, and lost both of his parents. With his life turned upside down, he decided to move the family from their rural Springfield, Ohio home and head for the city—starting with Indianapolis. Through some bit of randomness, he got a gig selling Dr. Price’s Baking Powder, a popular brand at the time (invented—amusingly enough—by the grandfather of the actor Vincent Price). Wright became the star of the regional sales team in Indy—perhaps even to his own surprise—and he used his new reputation to lock down a better paying gig in Chicago. His new employer? None other than his future nemesis, the Royal Baking Powder Co.

Wright continued to excel as one of Royal’s best jobbers in the Midwest, but he likely sensed that the future wasn’t going to be bright sticking with the company. In 1888, there was a major rift at Royal, as co-founder William Ziegler first sold off all his shares, then sued his former business partner Joseph C. Hoagland for withholding funds. For William Wright, this might have offered an impetus to take a shot at going solo in his own right.

Scrambling together his life savings, a mere $3,500, Wright decided to take everything he’d learned as a baking powder salesman and put it toward creating his own winning formula—the next step in the product’s evolution, he hoped. Working with a chemist named George Rew, the duo concocted a powder that utilized alum-phosphate over tartar, and adapted the egg white ingredient from an old Dr. Price playbook. About 15 years before the Wright Brothers mastered flight with a triple axis control system, William Wright conquered baking powder with a “double leavening” system.

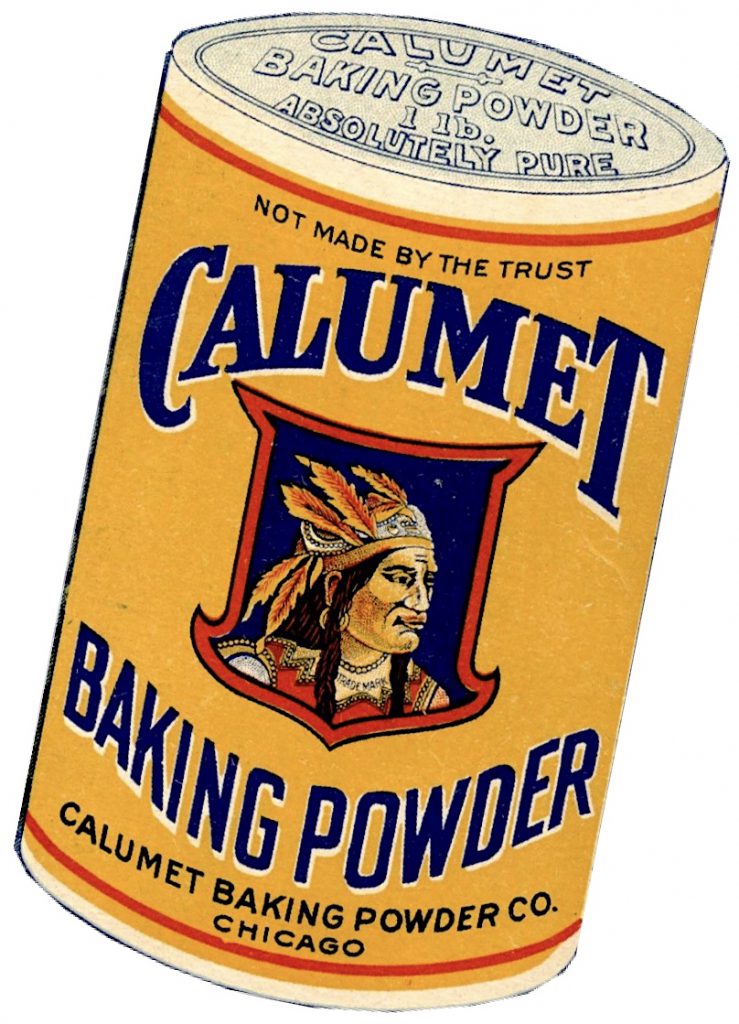

Pleased with their work, Wright and Rew launched the Calumet Baking Powder Company in 1889, named for William’s deceased younger brother, Calumet Wright. The word “Calumet” also had some geographical connotations in the Chicago area, of course, not to mention its original historic meaning as the French word for a Native American peace pipe. And thus, the iconic Indian head logo was introduced. That logo has evolved a bit over the past 130 years, but it has remained one of the instantly recognized images in American grocery aisles, maybe just in that second tier behind the Morton Salt Girl and Mr. Peanut.

Pleased with their work, Wright and Rew launched the Calumet Baking Powder Company in 1889, named for William’s deceased younger brother, Calumet Wright. The word “Calumet” also had some geographical connotations in the Chicago area, of course, not to mention its original historic meaning as the French word for a Native American peace pipe. And thus, the iconic Indian head logo was introduced. That logo has evolved a bit over the past 130 years, but it has remained one of the instantly recognized images in American grocery aisles, maybe just in that second tier behind the Morton Salt Girl and Mr. Peanut.

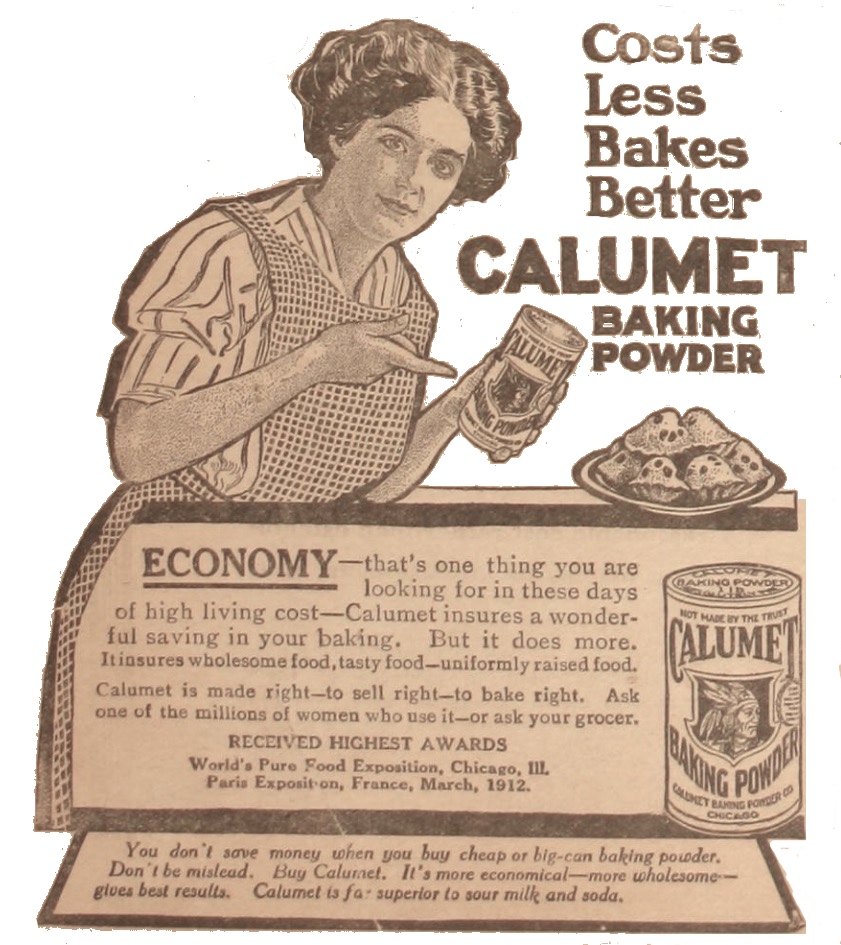

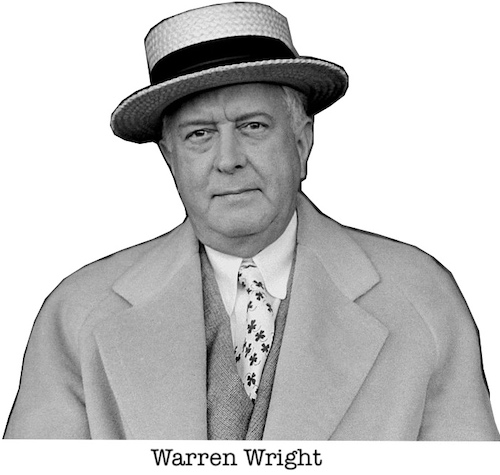

By the turn of the century, the Calumet product was starting to take off, despite the consistent attacks and conspiracy theories coming from those tartar bastards. Turns out, the public liked a good value and better tasting cakes even more than they feared malaria. George Rew, as Calumet’s lead science guy and vice president, did the heavy lifting of defending the company against unfair legal action, while William’s son Warren Wright—now in his mid 20s—was taking on a bigger role on the business end, pushing Calumet with a fervor even his father lacked.

II: Winning the War

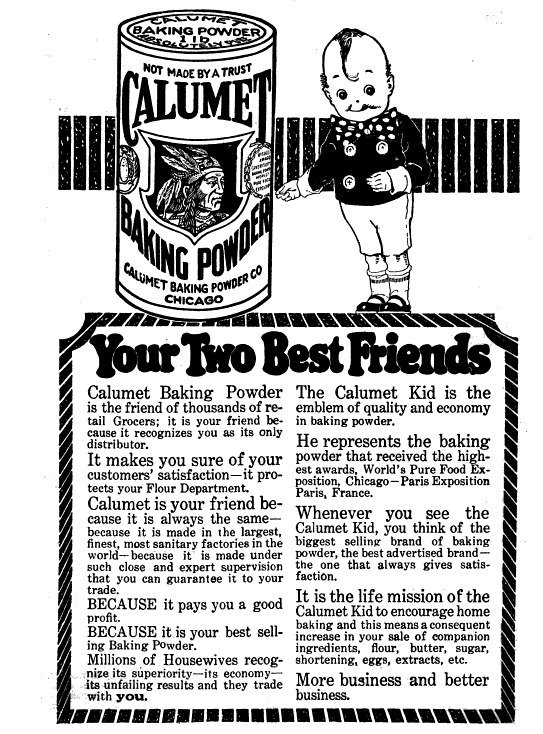

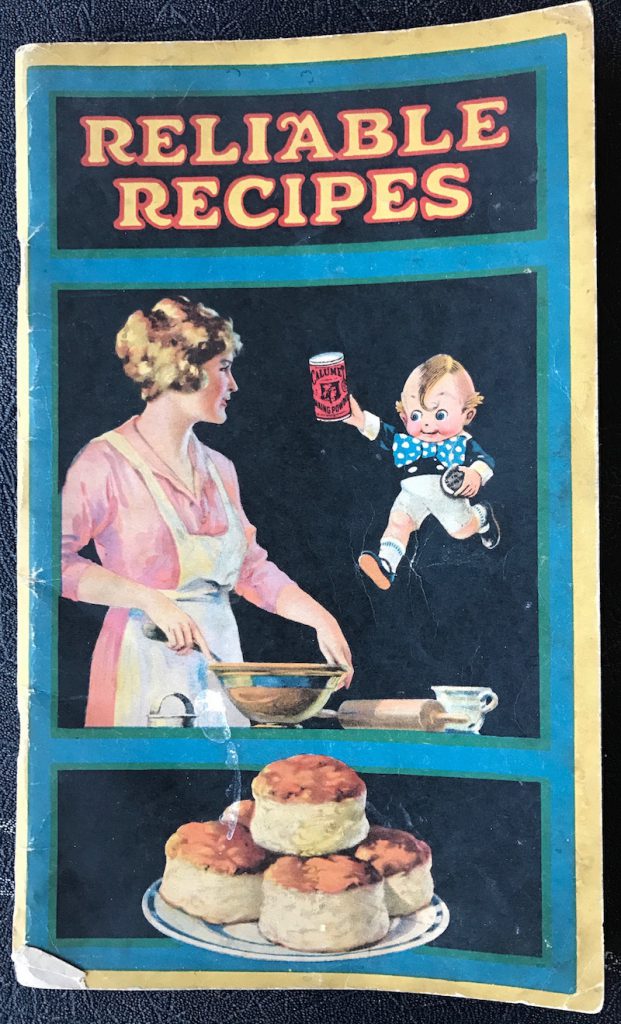

Under Warren Wright’s watch, Calumet seemed to figure out the perfect strategy for ingratiating itself to the public while simultaneously blasting back at its opponents. It essentially became a company with two faces . . . literally and figuratively. On the one hand, there was the “aww shucks” Calumet, represented by its incorrigible new mascot, the Calumet Kid—a bow-tie-wearing baby who just loved baking muffins! On the flip side, there was the stern, capable, and resilient Calumet—the Indian Chief—ceaselessly defending the company against a barrage of BS.

Balancing toughness with fluff was critical, since too much of a dependence on either could have meant disaster in the middle of a legitimate marketing war. The goal was to get proactive, even if meant turning the backside of a Calumet can into a boastful open challenge.

“One thousand dollars will be given away for any substance injurious to health found in Calumet Baking Powder,” the label read. “No baking powder on the market will produce as light, sweet, healthful food, entirely free from alum, Rochelle salts, lime or ammonia, as Calumet Baking Powder. The baking powder contains alum manufactured with the greatest care especially for us from pure criolites. This is not the alum of the drug stores, and in the process of baking is completely changed, so as to leave in the food no substance injurious to health.”

[Calumet, we’d be more inclined to believe you if you said “Our Government”]

[Calumet, we’d be more inclined to believe you if you said “Our Government”]

Our old friend George Rew had to explain the meaning of that exact language before a U.S. Senate committee hearing on alum during the height of the “Baking Powder Controversies” in 1899, and his testimony took a delightful, Bill Clinton-esque turn.

CHAIRMAN: “Mr. Rew, is this label intended to show the consumer that this product does contain alum?”

GEORGE REW: “It is to assure the customer that the substances left in food prepared with our baking powder are not injurious; rather, to show what is not there more than anything else.”

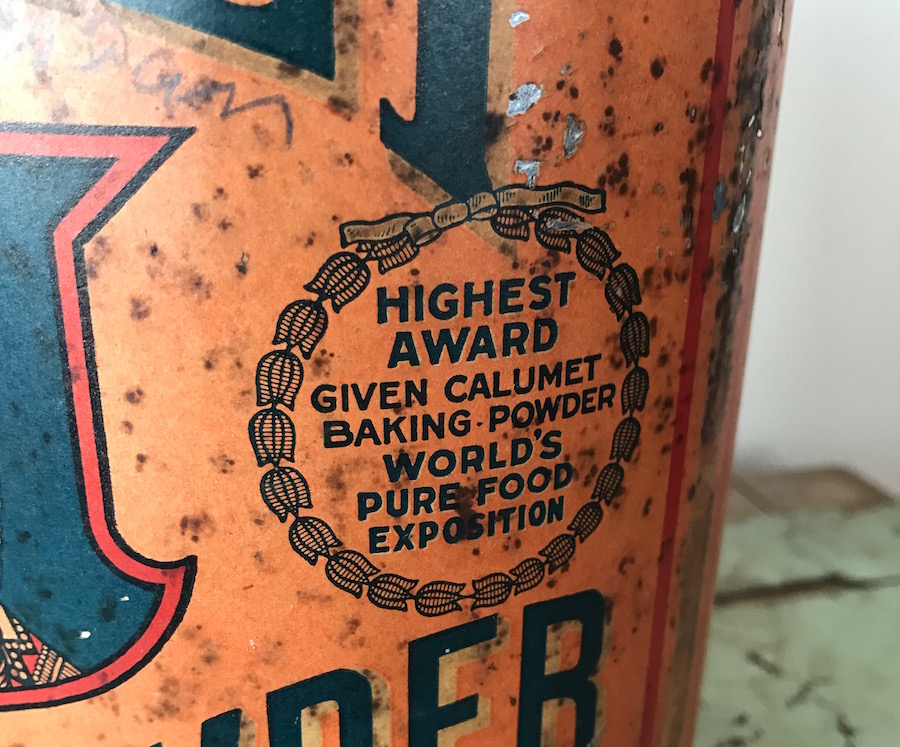

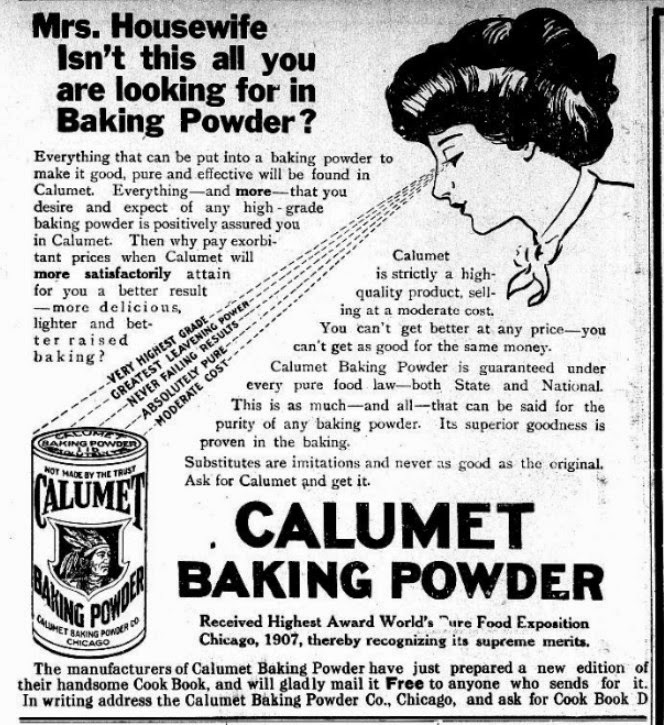

The fine print wasn’t the only thing being challenged on Calumet’s tins. If you look at our museum piece, you’ll notice two badges of merit on either side of the logo. The one on the left is some sort of gold medal from the 1912 Exposition Internationale D’Alimentation et D’Hygiene in Paris, and the other is a “Highest Award” from the World’s Pure Food Exposition, which was held in Chicago back in 1907. Calumet proudly used its success at the Pure Food Expo in its ad campaigns for years afterwards, but as with everything else they did, this was soon undermined.

In 1909, a publication called What to Eat (soon renamed The National Food Magazine) essentially accused Calumet of rigging the Pure Food Exhibition from the start, noting that George Rew was a member of the Food Expo’s “Committee on Awards.” Fishier still, one of the key members of the test committee that gave Calumet its “Highest Award,” Dr. Harvey Wiley, claimed he had actually refused to partake as a judge and that his name was being used falsely to support Calumet’s braggadocious promotions. In an interesting plot twist, however, Dr. Wiley was also the new editor of What To Eat magazine, so . . . there seemed to be an additional conflict of interest at work there.

In any case, William Wright responded to the nasty accusations swiftly and aggressively, suing What to Eat for $100,000 in libel, which is about $2.5 million after inflation. From what I can gather, the case was eventually settled out of court.

By now, William was tiring of the endless fight. Though still overseeing his company’s affairs, he relinquished day-to-day control to his son Warren in 1910, and turned his own attention to operating the Calumet Farm—a horse training center in Libertyville, IL.

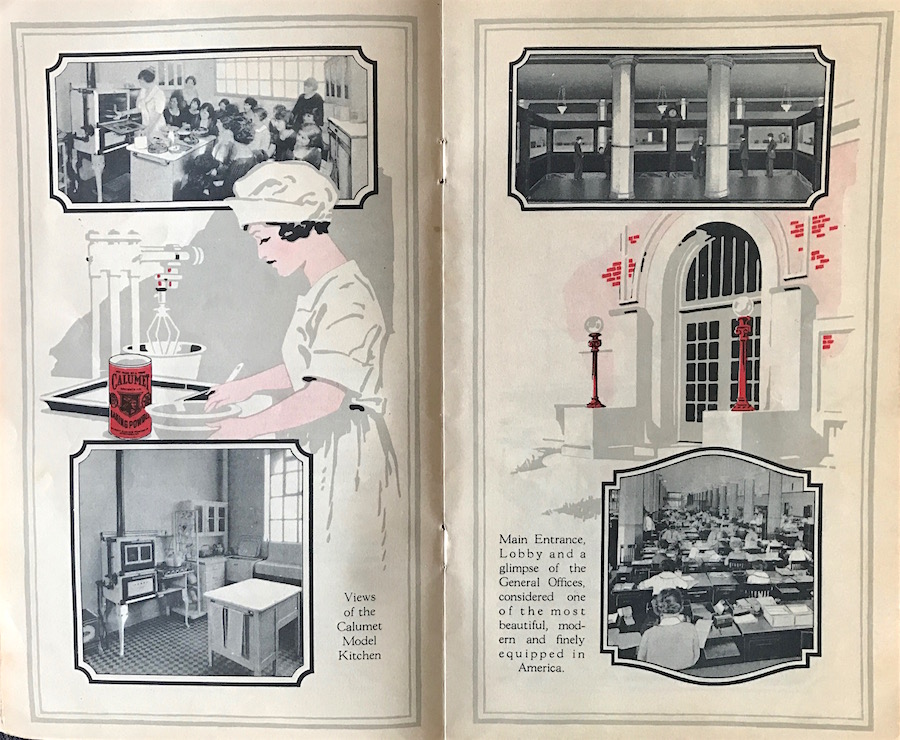

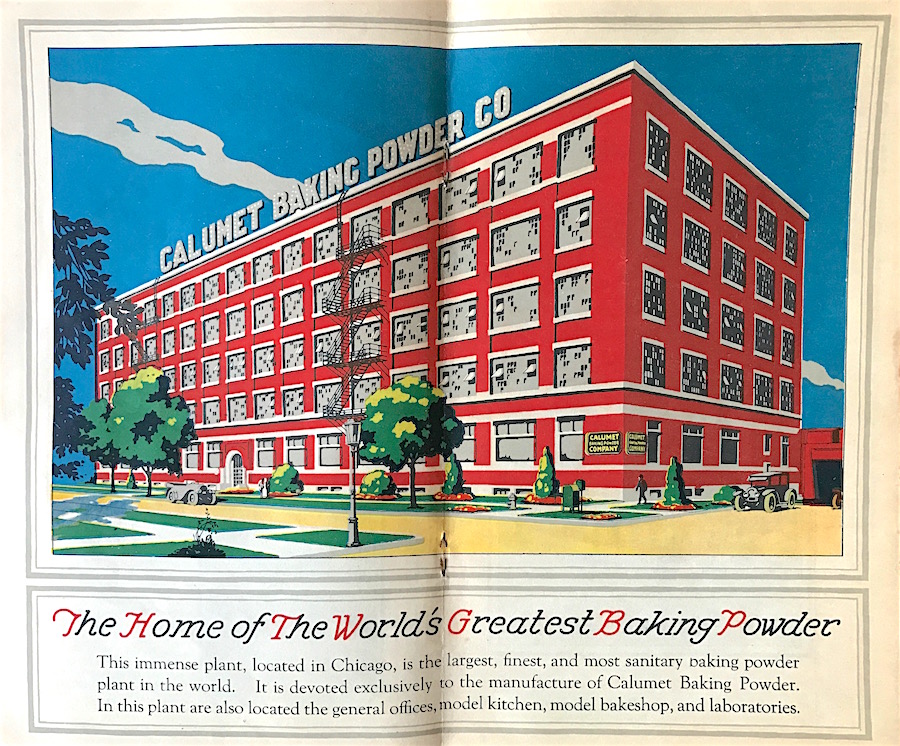

A few years later, in 1913, Warren had his coming out party, opening a new, sprawling 160,000 square foot Calumet factory at 4100 W. Fillmore Street. Such a monument of industry would seem to stand as a statement of ultimate victory in the Baking Powder War. And yet . . . the combat persisted.

[Above: Calumet workers, mostly women, outside the Fillmore Street warehouse in the 1920s; Below: the same building today]

[Above: Calumet workers, mostly women, outside the Fillmore Street warehouse in the 1920s; Below: the same building today]

Within months of the new plant opening, another one of Calumet’s rivals, the Jaques MFG Co. of Chicago (makers of K.C. Baking Powder) joined the fray, teaming with Royal to claim that Calumet’s use of egg whites was just as bad, if not worse, than the whole alum thing.

Incredibly, Calumet responded with an entire 200 page BOOK on the subject, titled—and I can’t make this stuff up—Why White of Eggs: A Truthful Sketch of the Inception and Efficiency of the Use of White of Eggs in Baking Powder; of the Recent Attempts to Restrict Its Use By False Interpretation of the Food Laws; and a Word as to the Future.

What lurks in those pages, suffice it to say, ain’t coming from the mouth of the Calumet Kid. In fact, a more serious tone couldn’t be found in a recorded history of an actual war.

What lurks in those pages, suffice it to say, ain’t coming from the mouth of the Calumet Kid. In fact, a more serious tone couldn’t be found in a recorded history of an actual war.

“Vicious intent often masquerades under the cloak of righteous indignation,” the book’s opening passage begins. “So subtle is the nature of some men that they are able to boldly pursue their selfish ends and yet hide their purpose by the loud cry of ‘Stop Thief!’ The requirements upon modern business life decree that only the fittest shall survive, while Nature’s first law commanding self-preservation remains as obdurate as before the dawn of civilization.

“Pity it is that the time is not yet passed when business corporations seek to promote their growth, not by extolling the virtues of their own products, but by vilification and slander of the wares and methods of competitors.”

With the spiteful poetry out of the way, the unidentified Calumet representative skips to the important part: “In spite of tremendous efforts by [the Royal Baking Powder Co.] and its Understudy, the Jaques MFG Co., white of eggs is acknowledged as a proper ingredient of baking powder.” Microphone drop.

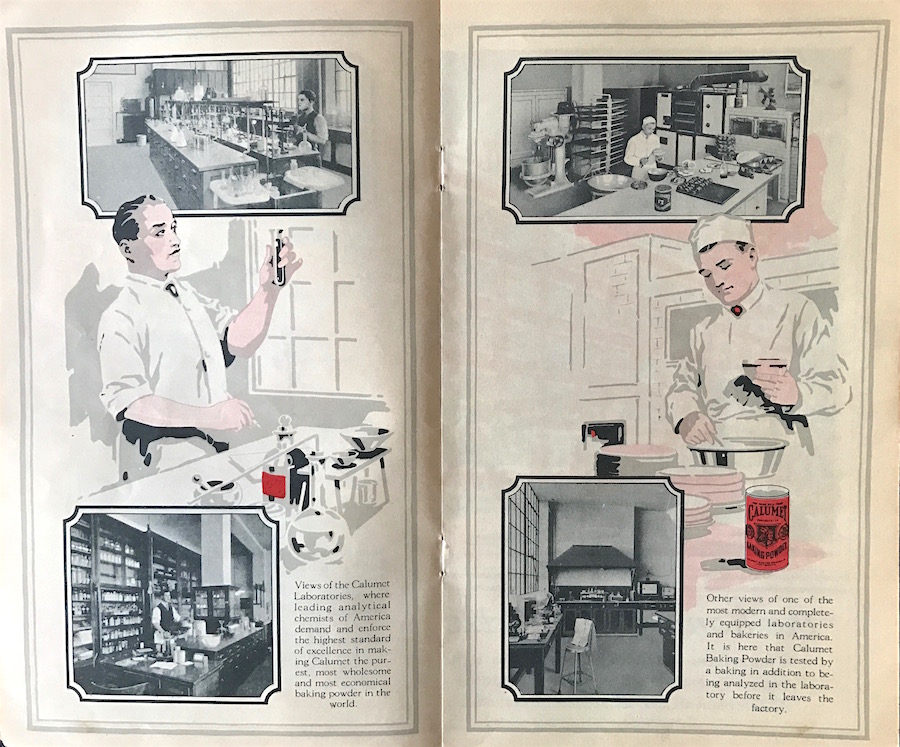

[Pages from the 1922 Calumet “Reliable Recipes” baking book]

[Pages from the 1922 Calumet “Reliable Recipes” baking book]

III: A Dash of Hypocrisy

Unsurprisingly, tensions did not improve after the egg-white debacle. And as the Baking Powder War moved into its fourth decade, Warren Wright grew increasingly impatient playing by the “defend-and-explain” strategy his dad had established. If this war was to be won, he figured, Calumet would have to start fighting fire with fire. The Calumet Kid was going rogue.

From around 1915 into the 1920s, the company began adopting the very same deceitful practices that had been used against them for years—planting false stories, hiring “experts” to write damning articles, and training its army of door-to-door salesmen with shady tactics. Calumet representatives even made a point of demonizing the use of self-rising flour, essentially adapting the anti-alum fear-mongering of years past.

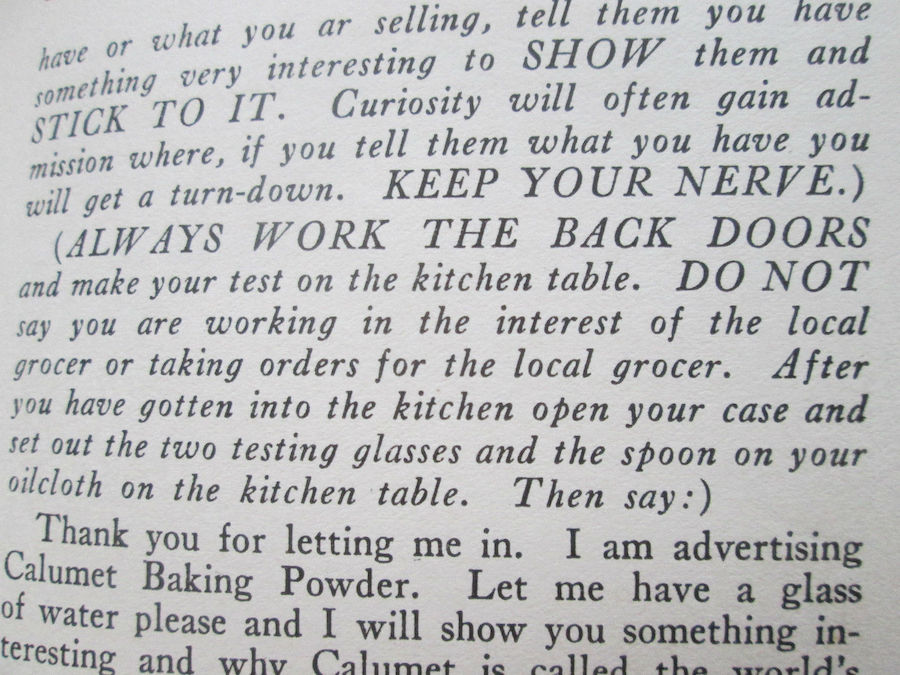

[Excerpt from a 1923 Calumet Demonstrators Text Book, a guide for its salesmen]

[Excerpt from a 1923 Calumet Demonstrators Text Book, a guide for its salesmen]

Crazier still, much of these practices only came to light because the Royal Baking Powder Company hired undercover operatives—I ain’t kidding—to infiltrate the Calumet offices in the early 1920s. What’s a war without spies?!

Once Calumet’s heel-turn was revealed, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission officially charged the company with unfair sales practices in 1924. The rebels had surrendered their innocence. . . . But, of course, they fought on.

IV: Endgame

As late as 1929, Calumet and Royal were still at each others’ throats, debating which of their products would kill Americans faster. Unmoved by decades of government hearings and scientific studies, Royal published a pamphlet in 1928 called “Alum in Baking Powder,” repeating many of its same tired arguments. Calumet, predictably, responded with another blusterous hard-cover book: The Truth About Baking Powder. Something needed to end this. For the sake of the children.

As it turned out, that “something” came along in the form of simple captialist economics.

As it turned out, that “something” came along in the form of simple captialist economics.

For years, national food conglomerates were growing larger and scooping up independent companies left and right. Calumet had received offers before, but didn’t flinch. By 1929, however, Warren Wright, now 52 years old, decided it was time to turn the page and go pursue the horse racing life with his pops. He sold the Calumet Baking Powder Co.—once valued at $3,500—for $32 million. It was now the property of America’s biggest food conglomerate, General Foods.

That same year, Royal Baking Powder Co. was sold to what would become the second biggest food conglomerate, the equally boring-sounding Standard Brands. Both Calumet and Royal would carry on as rival brands, but the inferno of hatred between their former ownership groups was extinguished.

Not to be overlooked, Warren Wright had sold Calumet—either through luck or cunning— at the best imaginable time. Just months after the deal was complete, the market crash sent many fortunes into ruin, while the Wright family was left sitting pretty. After William’s death in 1931, Warren took in a second wave of cash, and used it to preside over a new Calumet Farm in Kentucky—one of the most successful breeding grounds for champion race horses in the 20th century, including eight Kentucky Derby winners.

Since General Foods was purchased in the 1980s, Calumet Baking Powder has carried on under the banner of another former Chicago business, Kraft Foods.

Epilogue: The Story of Two “Calumet Girls” from the 1920s

Two guests of the museum have recently shared stories with us about their grandmothers, each of whom worked for Calumet (in different capacities) during the 1920s.

Colleen Gracey told us about her grandma Luella Conway (later Manley) who worked at the Fillmore Street plant in her youth. As you can see from these unique photos Colleen provided of her gran at work, it seems that Luella made plenty of friends in her department.

[Luella Conway, the third woman down from the top in the top left picture, worked for Calumet at its Chicago plant in the 1920s. The shots above show Luella’s co-workers outside the Fillmore Street building, while the photo below is an interior look of the ladies posing at their workstation]

Another visitor, Kathleen Winchester, shared a story passed down from her grandmother, Signa Westman Winchester, who had a unique job working as a Calumet Baking Powder sales representative, aka a “Calumet Girl,” in 1920. The gig wound up changing the course of the young woman’s life, and the generations that followed. I suppose you could call Signa a proud “veteran” of the Baking Powder War.

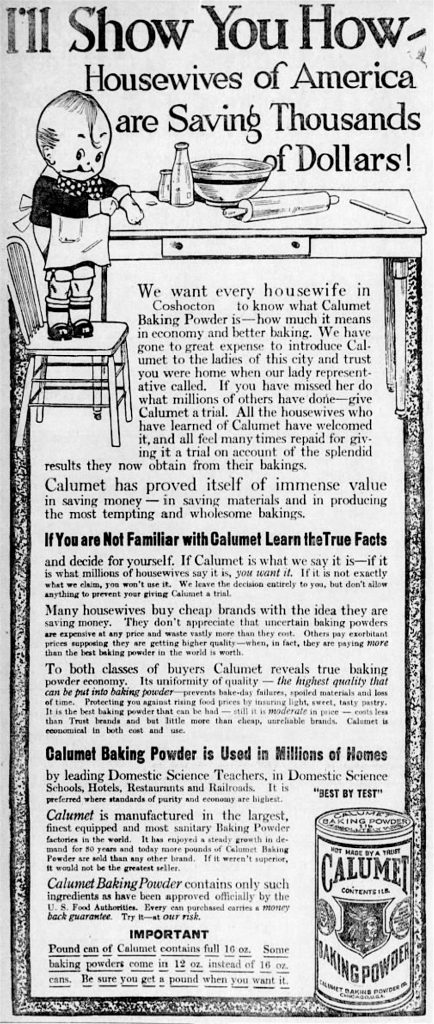

Signa [pictured] was just 20 years old in 1920, but she’d been through plenty. During World War I, she’d taken an office job in the Seattle shipyards; a position she lost when the boys returned from Europe. The flu epidemic of 1918 had taken its toll on family and friends, as well. And so, when she heard about the Calumet company hiring young women to join its promotional tour as “lady representatives”—doing personal home demonstrations of Calumet’s superior baking quality—she jumped at the opportunity.

Signa [pictured] was just 20 years old in 1920, but she’d been through plenty. During World War I, she’d taken an office job in the Seattle shipyards; a position she lost when the boys returned from Europe. The flu epidemic of 1918 had taken its toll on family and friends, as well. And so, when she heard about the Calumet company hiring young women to join its promotional tour as “lady representatives”—doing personal home demonstrations of Calumet’s superior baking quality—she jumped at the opportunity.

“Grandmother was Swedish – they were the best cooks!” her granddaughter Kathleen says. “By the spring of 1920, she was out on a ‘Calumet Tour,’ joining some other girls from the Seattle area. The homes they visited were already scouted out and confirmed appointments were made. The girls were then taken to the homes, where they would bake for the woman of the house and show them how to bake with Calumet—the wondrous product they could now have in their possession. Each Calumet Girl had to have written consent from their parents to do this, and they were chaperoned wherever they went!”

Indeed, Calumet was running similar programs in regions all over the country. A 1921 newspaper ad in Akron, Ohio, was printed as an open letter “To the Ladies of Akron”: “Our lady representative will call at your home to show you what Calumet Baking Powder will do for you and why it is called the cook’s best friend.” The identical ad ran in Leavenworth, Washington (a bit closer to Signa Westman’s neck of the woods), with only the name of the town changed in the copy.

While the business model was similar to the Avon approach of hiring women for door-to-door sales, it was hardly a mainstream concept for the time.

“No respectable young woman would ever be caught going around by themselves doing this type of work,” Kathleen says. “Remember, the flu epidemic had just past. But these brave young girls were going into strange cities and strangers’ homes to teach them how to cook. They were really out of their comfort zones — considering their upbringings and where they were in the time frame of history. Women were fighting for the right to vote at this time, as well. So you can see, it was a new step for womankind.”

“No respectable young woman would ever be caught going around by themselves doing this type of work,” Kathleen says. “Remember, the flu epidemic had just past. But these brave young girls were going into strange cities and strangers’ homes to teach them how to cook. They were really out of their comfort zones — considering their upbringings and where they were in the time frame of history. Women were fighting for the right to vote at this time, as well. So you can see, it was a new step for womankind.”

According to her granddaughter, Signa was “a quiet and unassuming young woman.” But she loved music and she loved to dance. She was saving up her Calumet earnings, in fact, to buy a piano, but wound up getting a lot more than she bargained for.

“One night, Signa and the other girls on the tour snuck out after ‘lights out’ and went dancing near Fort Lewis, where they knew there’d be young servicemen to dance with. They danced and had a great time, and my grandmother met the man who would become my grandfather that night (he was stationed at Fort Lewis). Later that year on July 5, 1920, they were married!

“That’s not the end of the story, though. When the girls came home after their night of dancing, they were caught by the chaperones! They asked who was the instigator? Since the girls knew they would all be punished if someone didn’t fess up, my grandmother stepped forward to admit to planning the outing. The woman in charge said, ‘You could not have done this, Signa. I know you. You would never do such a thing!’ Another girl was then singled out instead, and despite the protests from Signa and the other girls, that innocent girl was punished anyway.

“My grandma always taught me to tell the truth. And though I was older when she told me this story, I will always remember her being regretful that her friend was blamed for what she had done.

“The good thing is, she met grandpa, and they had 5 children, 16 grandchildren, 25 great grandchildren, and keep counting more than 30 second great grandchildren. Thank you, Calumet, for being there to make it possible for my grandparents to meet and marry!” –Kathleen Winchester

[This Calumet recipe book from 1922 is also part of our museum collection]

[This Calumet recipe book from 1922 is also part of our museum collection]

Sources:

“Mr. Calumet: Remembering the Man who Founded Racing’s Greatest Classic Dynasty” by Mary Simon, Daily Racing Form

Why White of Eggs, by Calumet Baking Powder Co., 1914

Wild Ride: The Rise and Tragic Fall of Calumet Farm, Inc., by Ann Hagedorn Auerbach

The Baking Powder Controversy, Vol. 1, by Abraham Cressy Morrison, 1904

“Baking Powder War,” Chicago Tribune, May 9, 1899

The Politics of Purity: Harvey Washington Wiley and the Origins of Federal Food Policy, by Clayton A. Coppin and Jack C. High, 1999

Report of the Industrial Commission on Trusts and Industrial Combinations, 1901

I have the 1929 book and treasure it.

Is there a way to determine the aproximate year tins were made?

I have my grandmothers calumet 10# bakers powder can. I am 71 and I have been using this can continuously, for sugar or flour, since the 1970’s. I have been trying to learn more about it. I find other examples of the can except none I have found say made in the U.S.A. on the lid. Does anyone know the age of mine? Also where do they procure the powder these days?

I have an original copy of .”Modern Mixes for Bakers” copywrite 1914 by the Calumet Baking Company. It is in good shape. Alot of info in it even if it is put dated. Would be willing to sell

.

I have several books called Sales-Sense which were written for salesmen going out in the field. My father was a cartoonest for the company and many of the cartoons in these books are by him. Does anyone know anything about these books.? They seem to be collections of monthly publications.

Looking for the pecan recipe

I have a reliable recipes cookbook from 1918 and I would say it is in fair shape for it’s age.If you are interested in it email me.

hello, i would be interested in the recipes cookbook from 1918. Thank you.

My grandmother was part of a group of “10 young ladies” who advertised and demonstrated for the Calumet Baking Powder Company and was based in Leavenworth Kansas in 1904. Looking for additional information

I purchased a vintage tin can of Calumet. There is still a little bit of the label on the outside of the lid, but part of it is missing. Can you tell me what is says in full? “We Hereby Guarantee To Consumers and Grocers…

Thank you,

My Grandmother used to make a meatloaf type mixture that she used Calumet Baking Powder tins to cook it in. The top of the can was cut off she filled the cans with her mixture then placed them standing upright in a cake pan that had between 2 and 3 inches of water into the oven. She baked them until the mixture was cooked completely set them out to cool. Once cool she would run a knife around the mixture and it would slide out in roll. This mixture was kept wrapped up tight in our refrigerator and sliced for use. We sliced it and added it to fried potatoes and onions, sliced fried and served with scrambled eggs, made sandwiches with it both heated or cold. She never showed any of us how to make this “meatloaf” mixture and we did not find a recipe for the it among my Grandmother’s belongings.

I have been searching the internet hoping maybe someone else’s family may have made this mixture and cooked it the same way. No luck finding it so far. If this sounds familiar to anyone I would love to have the recipe. Thank you!

My wife’s mother was a sales demo woman who traveled eastern US selling door to door. We are looking for info about the group of women, especially photos of the group. Any other info would also be very helpful.

I was handed down a Calumet “Regulator” (like a clock) which I was told was a award for selling X amount of Calumet. I was wondering if anyone has any idea how old this might be such as when the contest ran.

When were Calumet pie tins marketed?

I have quite the collection of calumet tins from 6oz to a 75lb tin and from the beginning to the 80s. I live in the midwest and love the history of calumet. Hopefully someday someone will enjoy my collection of calumet tins as I do.

Why is it so difficult to find Calumet baking powder. Every source I try, it has been discontinued or is “out of stock.” It is by far the best I’ve tried, and this makes me very sad!

I have found a copy of the 1922 Calumet Reliable Recipes and wondered if you were interested in adding it to your collection. It is in good condition and I would be glad to send it to you.

I have a 24th Edition Reliable Recipes cookbook published by Calumet Baking Powder Co.

and was curious what year this was published. The cover is a little bit worn but the pages are in good shape. It is really an amazing book.

Hi, I have an old calumet, 6 oz tin that was my mother’s. It has a paper label printed with world’s pure food and expositique Paris awards. On the back, between directions in English & above the ingredients are directions in, I believe, German. I don’t find patent pending on it. Do you know where & where this was sold? My grandmother came from Iowa & only spoke German until she started school, I wonder if it was hers.