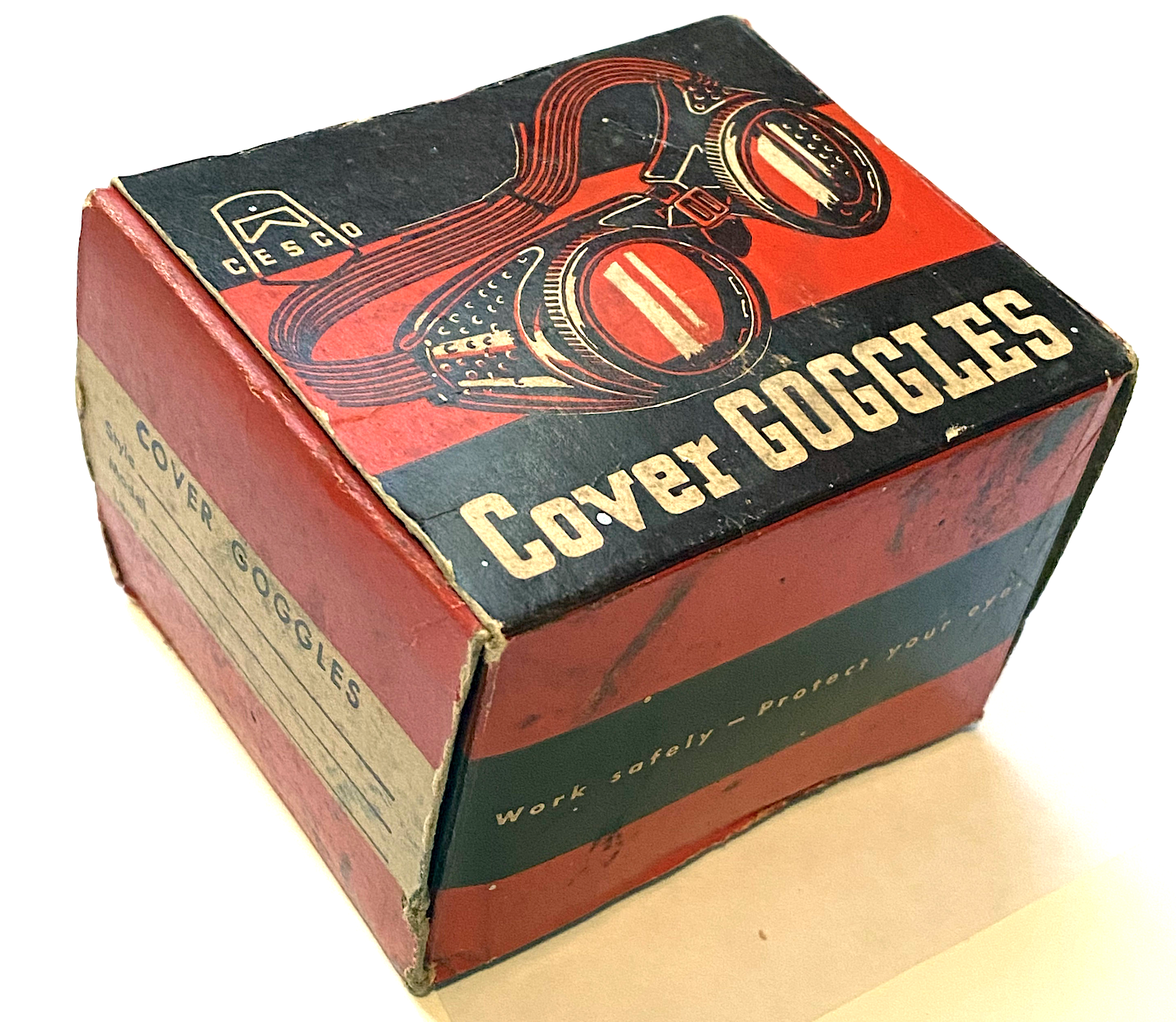

Museum Artifact: Industrial Cover Goggles, c. 1950s

Made By: Chicago Eye Shield Company, aka CESCO, 2300 W. Warren Blvd., Chicago, IL [Near West Side]

“CESCO’s complete line of head and eye safety equipment always benefits users—prevents injuries, saves lives, saves dollars and earns profits.” —Chicago Eye Shield Company advertisement, 1945

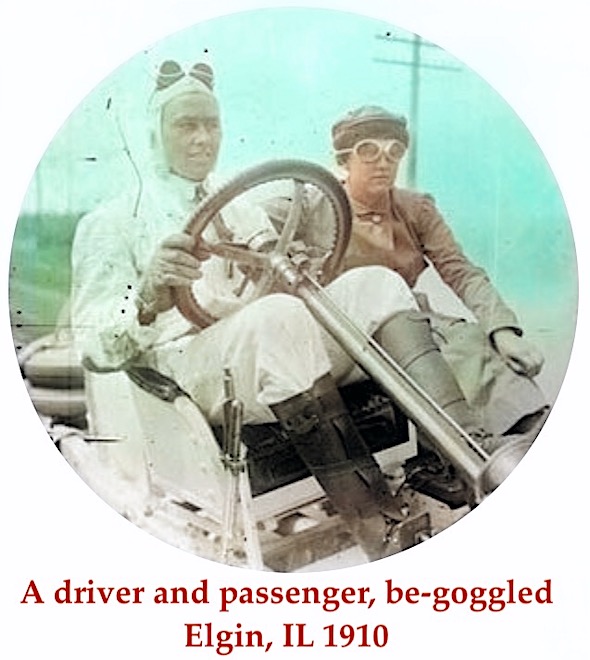

The Chicago Eye Shield Company, aka CESCO, was founded in 1903—the same year the Wright Brothers ushered in the aeronautics age, Ford introduced the Model A automobile, and Harley-Davidson built its first motorcycle. The timing wasn’t exactly a coincidence, either. With a new generation of bikers, drivers, and aviators on the horizon, a whole new set of safety risks was sure to follow; many of them related to protecting one’s bloodshot eyeballs from the flying debris associated with these open-air, high-speed hobbies. Add in the thousands of men and women still putting their retinas in daily peril doing factory, farming, or mining work, and the profit potential for a turn-of-the-century “eye shield” business suddenly looks limitless.

The Chicago Eye Shield Company, aka CESCO, was founded in 1903—the same year the Wright Brothers ushered in the aeronautics age, Ford introduced the Model A automobile, and Harley-Davidson built its first motorcycle. The timing wasn’t exactly a coincidence, either. With a new generation of bikers, drivers, and aviators on the horizon, a whole new set of safety risks was sure to follow; many of them related to protecting one’s bloodshot eyeballs from the flying debris associated with these open-air, high-speed hobbies. Add in the thousands of men and women still putting their retinas in daily peril doing factory, farming, or mining work, and the profit potential for a turn-of-the-century “eye shield” business suddenly looks limitless.

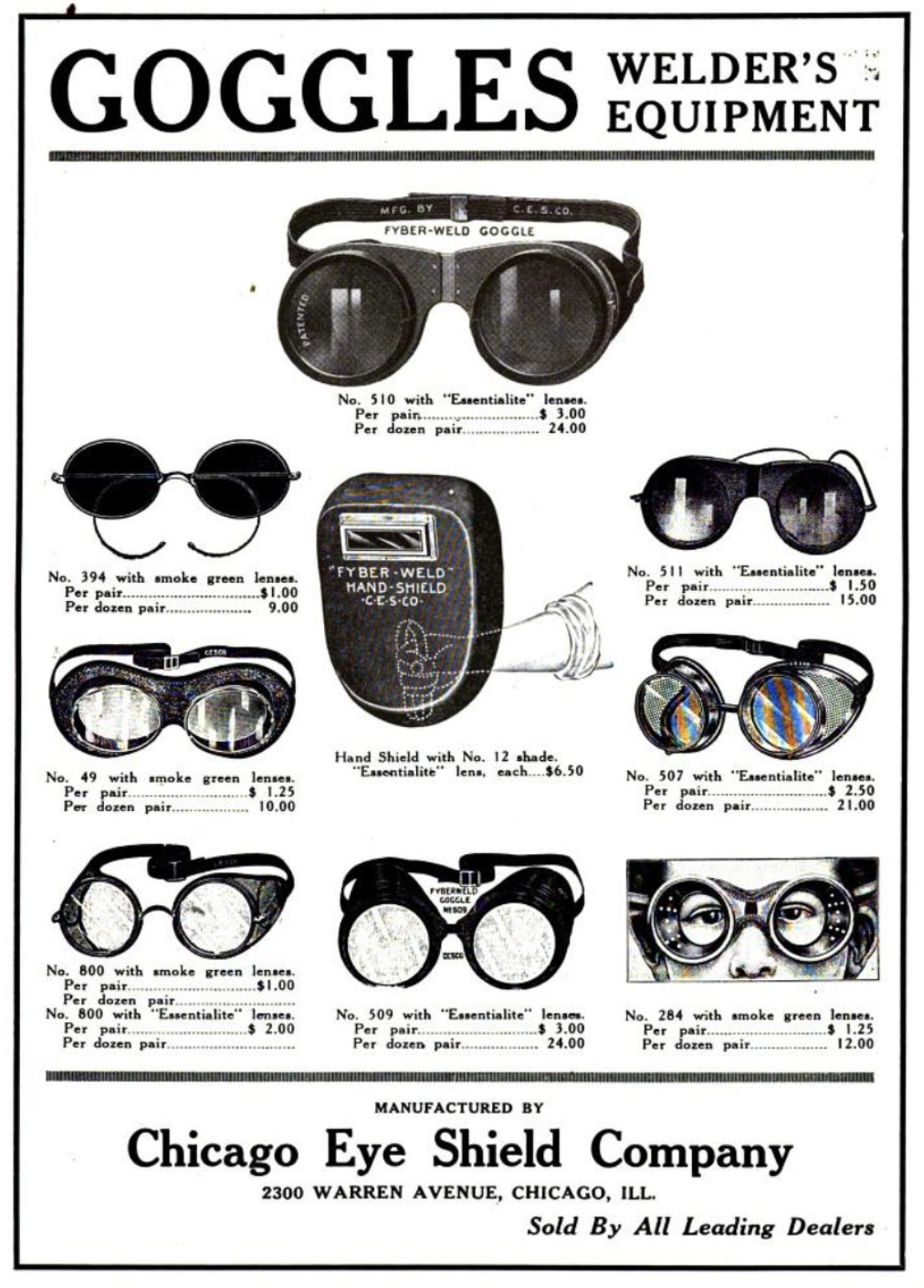

Combining that opportunism with innovation, CESCO soon emerged as one of the country’s largest and most significant manufacturers of above-the-neck safety gear. Over the decades, the company’s product line included everything from face shields and respirators to welder’s helmets and catcher’s masks, but they were known best for their wide range of goggles—the airtight eyewear that became the official facial fashion accessory of American progress and ingenuity . . . worn by the folks building the new vehicles and by those driving them.

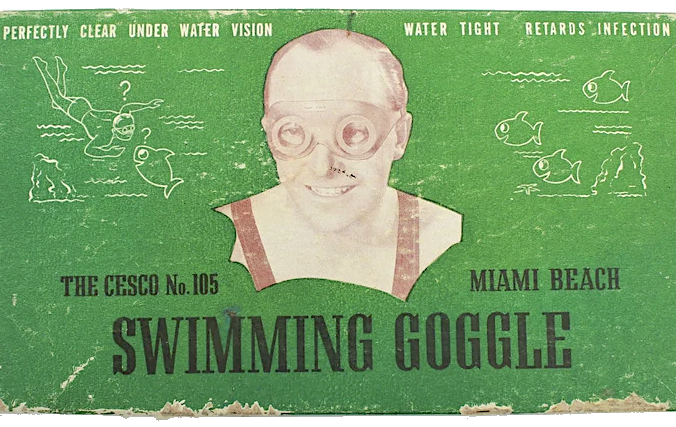

The industrial and transportation markets were so strong for CESCO, in fact, that it took a long while before the company, or any of its rivals, recognized the other most inherently obvious clientele for eye goggles . . . swimmers. It wasn’t until 1911, when Thomas “Bill” Burgess swam across the English Channel wearing a pair of motorcycle goggles, that the lightbulb went off on that one.

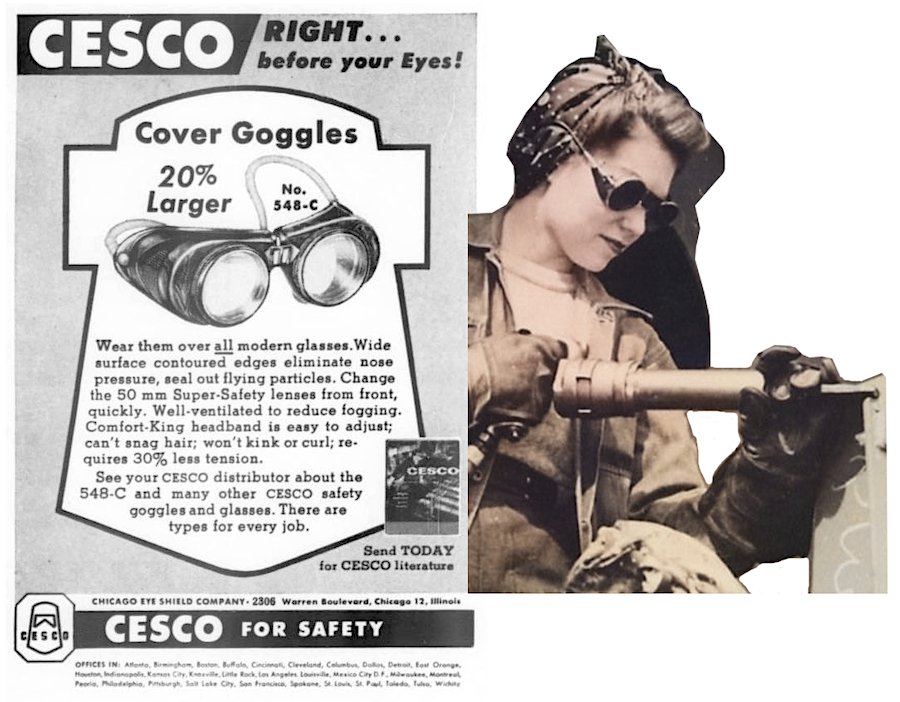

The specific pair of CESCO goggles in our museum collection were intended less for swimming or sport and more for daily industrial use, offering workers an extra layer of eye protection without sacrificing their prescription lenses. Introduced in 1953, the “new series 548 and 549 Cover Goggles by CESCO will fit comfortably over all popular styles of men’s or women’s glasses,” according to an advertisement from that year. “A 20% increase in size over similar goggles permits clearance of even the modern extreme styles.

“There is nothing better than the CESCO Cover Goggle,” the ad concludes, punctuated by a pretty solid tagline: “It is Right . . . before your eyes!”

History of the Chicago Eye Shield Co., Part I: The Necessity of Protection

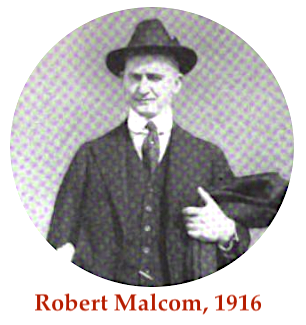

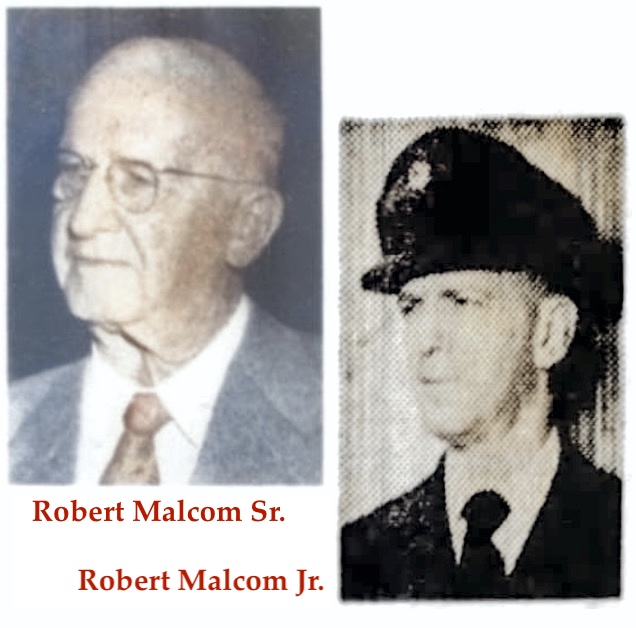

The astute gentleman who recognized the imminent rise of goggle-mania was Robert Malcom (1871-1953), CESCO’s founder and longtime president. A Chicago native and graduate of Lake View High School, he was—in many ways—a typical streetwise city boy growing up during Chicago’s post-fire renaissance. Between the ages of 9 and 14, however, he’d also experienced a very different lifestyle, as his family temporarily relocated to a farm in Stockton, California.

“Robert Malcolm [sic], president of the Chicago Eye Shield Company, had the advantages enjoyed by the major portion of men at the head of big enterprises—he was born and raised on a farm,” Office Appliances reported in a profile on Malcom in 1916. The magazine misspelled Robert’s surname and mischaracterized his childhood timeline a bit, but they might have been half-right about the benefits of that formative farm experience.

“Robert Malcolm [sic], president of the Chicago Eye Shield Company, had the advantages enjoyed by the major portion of men at the head of big enterprises—he was born and raised on a farm,” Office Appliances reported in a profile on Malcom in 1916. The magazine misspelled Robert’s surname and mischaracterized his childhood timeline a bit, but they might have been half-right about the benefits of that formative farm experience.

“The farm boy is cut off from those aids which enervate more than they help the city boy. He must do things himself or leave them undone. When some part of the machinery breaks it must be fixed on the spot, or without leaving the farm, hence farm boys acquire self-reliance and that mental training which goes with the training of the hand for service.”

If Robert Malcom got his self-reliance from his rural days and his business smarts from the city, his cross-country travels between the two probably gave him a unique understanding of his clientele and their evolving needs.

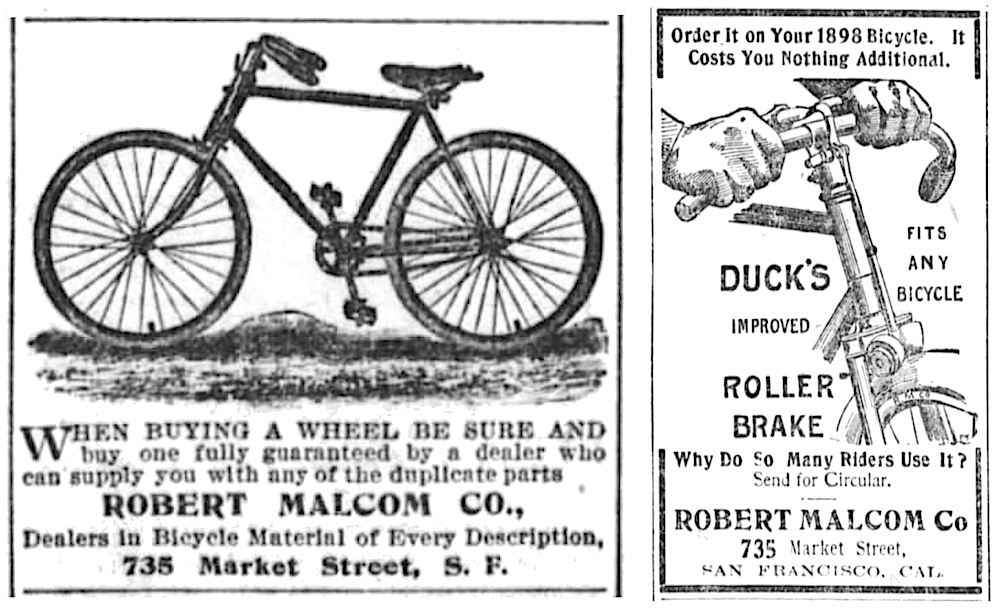

By the age of 25, Malcom had left Chicago and returned to the West Coast—this time for San Francisco—where he opened up a shop selling bicycle parts and other small accessories, including protective eye gear. The Robert Malcom Company remained in business on Market Street until around 1900, when the magnetic pull of his hometown brought Robert back to Chicago once again. The timing was good, too, because had he stayed in San Fran much longer, his business almost certainly would have been a casualty of that city’s horrific 1906 earthquake.

[Newspaper ads for the Robert Malcom Company, dated 1897 (left) and 1898. Robert Malcom ran this bike accessory shop on Market Street in San Francisco for several years before returning to Chicago to start the Chicago Eye Shield Company in 1903]

Malcom was 32 years old when he organized the Chicago Eye Shield Company in May of 1903. It was a humble affair inside a small office at 112 E. Randolph St., with Robert, a business partner, and a team of six female assemblers. The company’s earliest products included celluloid automobile goggles and a line of visors or “eye shades” that were popular with accountants and bookkeepers. “Protect your eyes, they are breadwinners!” read a 1904 ad for the company’s Featherweight Eye Shade.

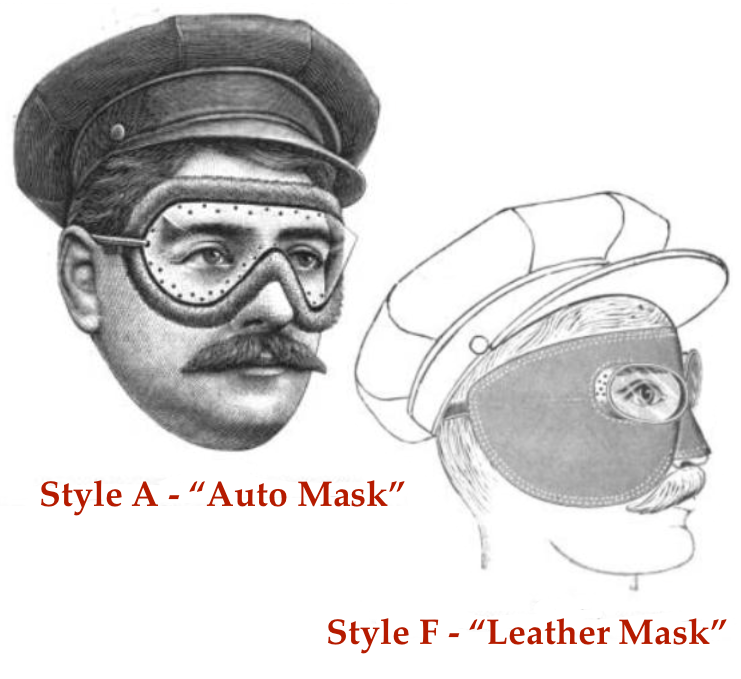

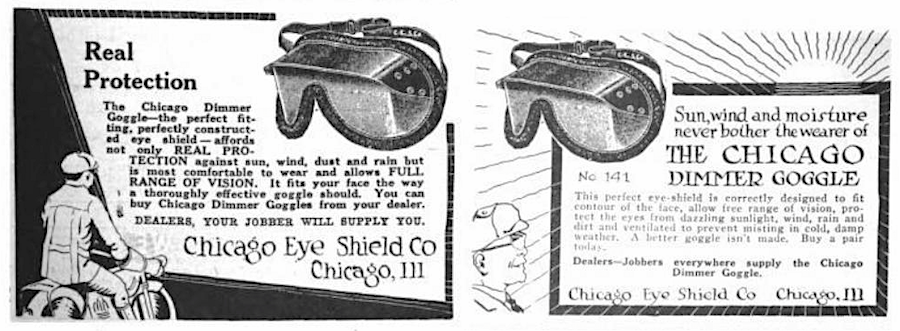

In December of 1904, Automobile Review published some illustrations of new CESCO products, noting that, “Automobile goggles have become a prime essential to pleasure in out-of-town touring. American roads are well noted for the dust cloud in the summer months, and many of our city streets cannot boast of immunity. The Chicago Eye Shield Co., Chicago, Ill., have several styles on the market.”

The style A “auto mask” was the budget model, made with an “extra large mica front, allowing an unlimited range of vision. . . . It is bound in chenille, and sells at $4.50 per dozen.”

The style A “auto mask” was the budget model, made with an “extra large mica front, allowing an unlimited range of vision. . . . It is bound in chenille, and sells at $4.50 per dozen.”

The fancier style F “leather mask” had mica goggles inserted into a Phantom of the Opera type of design, complete with a nose protector and side protectors for the cheeks and ears. It went for $36 per dozen.

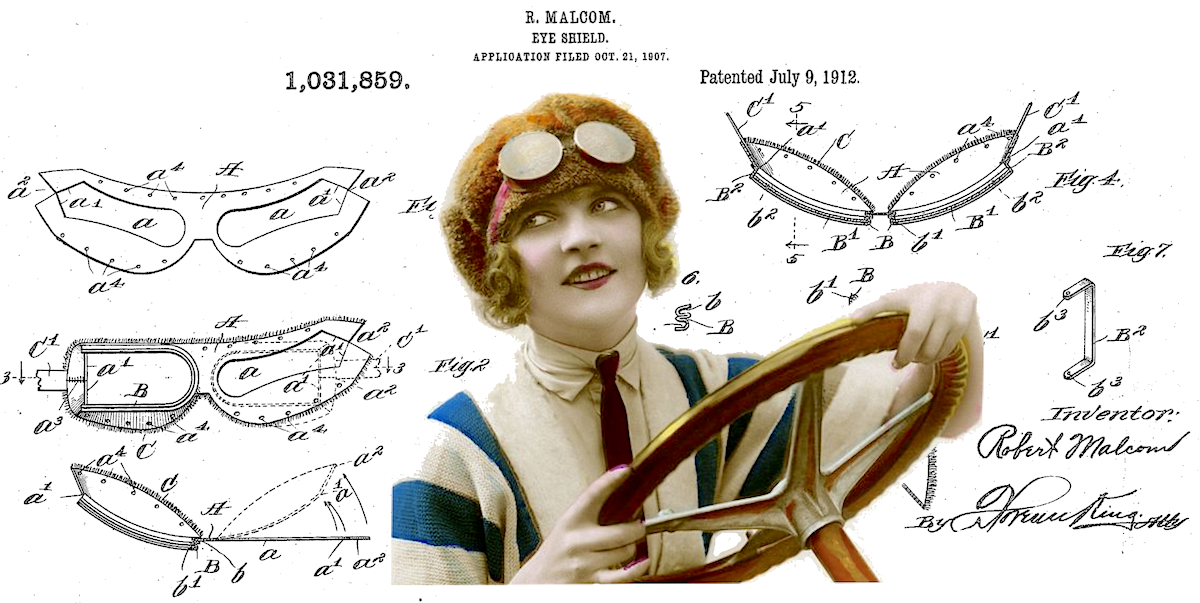

From early on, Robert Malcom wasn’t just a lead salesman for CESCO, but its primary product developer, as well. And as more goggle manufacturing competitors started pouring into the market, he raced to defend his intellectual property from copycats; particularly the wrap-around “Chicago Auto Goggle” that had become his biggest seller.

“The successful merchant is almost constantly beset by some kind of piracy upon the products that have contributed to his success, and the Chicago Eye Shield Co. is not an exception to the rule,” the National Druggist reported in 1907, in what was likely more of a thinly veiled advertisement. “Of course imitation is the sincerest kind of flattery, but it is not the kind that the manufacturer wants. Bumps of this kind, however, usually inspire the strong man with greater persistency and determination. . . . Like the victorious rooster whose plumage has been rendered slightly distrait, the Chicago Eye Shield Co. shook the dust of battle from itself after a victorious suit against infringers a few months since, and continued on its even way in the enjoyment of its rights and the confidence of the trade.

“The automobile has come to stay, and the public, more and more each day, recognizes the necessity of protection for the eyes. Judging from the constant growth of the trade of the Chicago Eye Shield Co., they have the best product . . .”

[One of Robert Malcom’s first auto goggle patents, applied for in 1907 and granted in 1912, became a top seller in his company’s early years, but declined as new enclosed automobile designs with windshields made protective eyewear more than a bit unnecessary for drivers.]

As mentioned in the same article, CESCO relocated to a new factory space in 1907, at 143 S. Clinton Street (later 128-134 S. Clinton St. after the street number changes of 1909). The new plant was described as a “monument to meritorious goods.” Here, Malcom was able to start growing his workforce and expanding his product line, but competition remained fierce—especially from foreign manufacturers who were able to make and sell their goggles at a fraction of the cost.

In 1908, Malcom penned a letter to the U.S. House Ways and Means Committee, requesting new tariffs against imported goods within his industry. “As a manufacturer of eye protectors, better known in the market as ‘goggles,’ such as used today in nearly every field, from the farmer in thrashing season to the driver of the auto, we wish to ask you for more protection from the inroads of the foreigner,” he wrote.

“Foreign goggles are being brought into this country today at 45 percent duty and sold for what they cost us to manufacture. . . . Take the aluminum goggle. We are the originators of this goggle. The dies for making cost us about $500. The goods made up, purchasing the raw material at the best figure possible in this country, stand us $2 per dozen. We can purchase these same goggles, duty and freight paid, laid down in New York City at $2.40 per dozen. We have no show for overhead expenses, advertising, etc.

“Foreign goggles are being brought into this country today at 45 percent duty and sold for what they cost us to manufacture. . . . Take the aluminum goggle. We are the originators of this goggle. The dies for making cost us about $500. The goods made up, purchasing the raw material at the best figure possible in this country, stand us $2 per dozen. We can purchase these same goggles, duty and freight paid, laid down in New York City at $2.40 per dozen. We have no show for overhead expenses, advertising, etc.

“We are only small people; we might give you pages of facts like this, but if the same continues we will have to quit the business. . . . We thank you for anything you can do to help us in our fight.”

The Payne–Aldrich Tariff Act, passed a year later, may have answered some of Malcom’s wishes, but when World War I broke out in the following decade, more extreme embargoes on imports saw much of CESCO’s foreign competition erased entirely. Seizing on the moment, Malcom produced many of his most important innovations during this same period—collecting at least 10 more patents (mostly related to eye protection equipment) between 1914 and 1920.

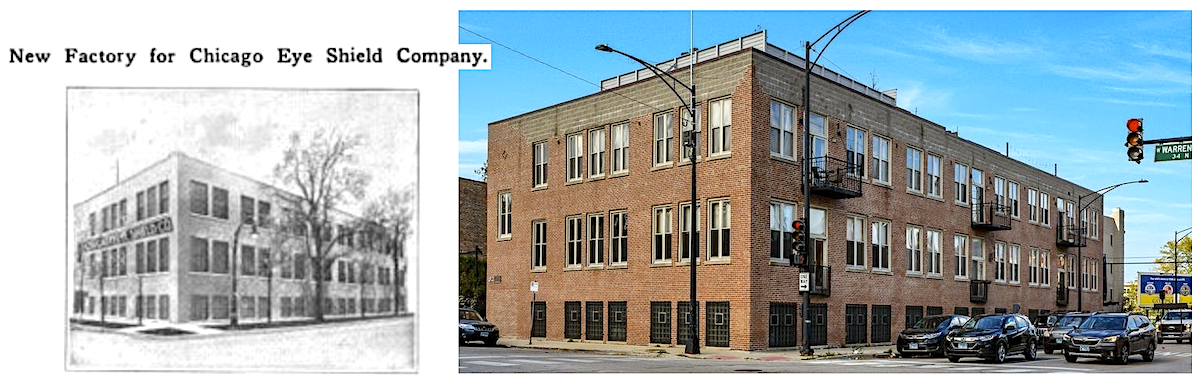

In 1916, the Chicago Eye Shield Co. was widely recognized as the largest firm of its kind in America, employing close to 400 workers inside its new factory building at 2300 W. Warren Blvd. “The building is a three-story, of brick exterior and slow-burning interior construction,” Office Appliances reported. “Light is admitted on all four sides, making the use of artificial lighting necessary only on the darkest of days. The new factory provides at least four times the capacity of the old quarters, and working conditions are ideal under the new arrangement.”

[Above – Then and Now: The former CESCO factory at 2300 W. Warren Blvd., 1916 and 2022. Below – Two ads for the Chicago Dimmer Goggle, 1916.]

II. Goggles Would Have Saved Him!

As goggles became less of a necessity for drivers after World War I, Chicago Eye Shield continued doing a strong business, focusing more on industrial goggles for welders, machinists, quarry workers, and the like. They promoted their products not only for the obvious reasons of protecting workers, but—perhaps more importantly to their employers—as a defense against the new Worker’s Compensation Act.

“Goggles would have saved him!” shouted a CESCO magazine ad in a 1917 issue of Rock Products and Building Materials, printed next to an illustration of a worker who appears to have just blinded himself on the job. “And they would have saved his employer a neat sum under the Workmen’s Compensation Act. In many states, whether the workman wears goggles or not, his employer, after having given him a pair, is not liable for eye injuries.”

“Goggles would have saved him!” shouted a CESCO magazine ad in a 1917 issue of Rock Products and Building Materials, printed next to an illustration of a worker who appears to have just blinded himself on the job. “And they would have saved his employer a neat sum under the Workmen’s Compensation Act. In many states, whether the workman wears goggles or not, his employer, after having given him a pair, is not liable for eye injuries.”

By his 50th birthday in 1921, Robert Malcom had saved plenty of money in his own right. Making his home in suburban La Grange with his wife Florence, he was now president of several other businesses, as well, including a glass making company he called the Oriental Art Glass Co., which opened its own dedicated factory in Cicero that year, employing a team of experts poached from the Tiffany Co.

Like many well-to-do tycoons of the Jazz Age, however, Malcom’s home life appears to have been far less lustrous than the glassware he produced.

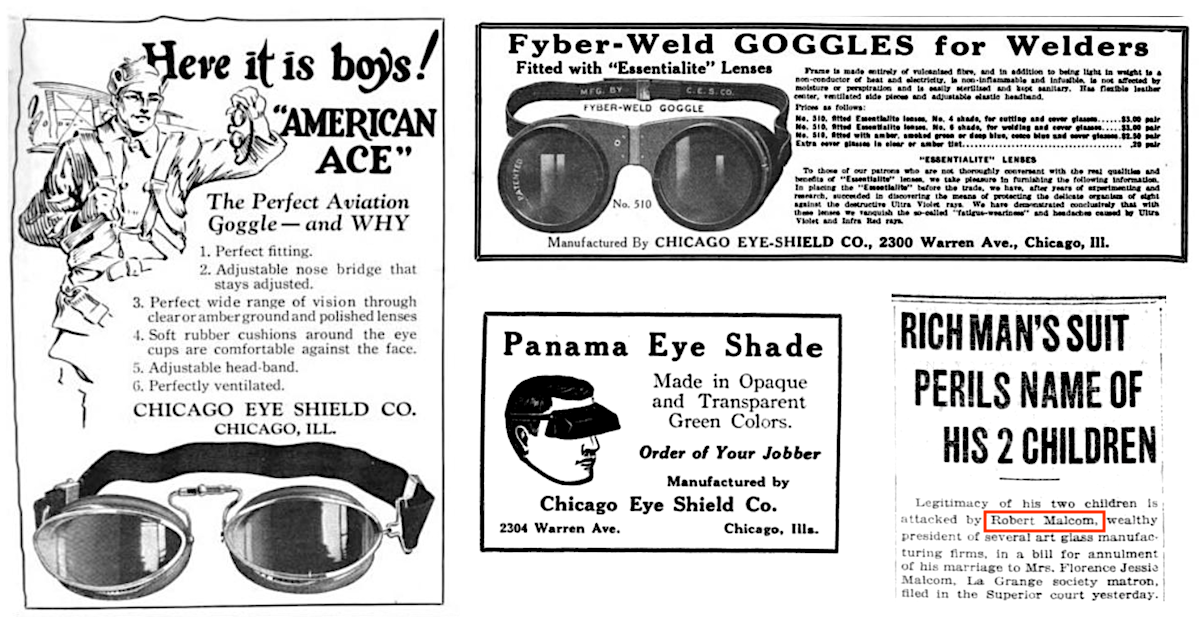

[Several CESCO ads from 1919-1920 featuring the “American Ace” aviation goggle, Fyber-Weld goggles for welders, and “Panama” eye shades for office workers. A 1923 newspaper clipping, bottom right, also shows how ugly Robert Malcom’s divorce with his first wife Florence became.]

In 1922, during a very public divorce proceeding with his wife of 16 years, Malcom accused Florence of having several affairs, and even questioned the legitimacy of the two children they’d been raising together. Florence fired back, defending her honor and describing Malcom as “a grasping, money-mad miser, making the vilest and most despicable charges a man can make against the mother of his children.”

Robert filed for custody of the kids, but they ultimately stayed with their mother. Within a few years, Robert remarried (a woman named Mary Blessing), and after she died in 1934, he tried again with a woman (Mildred) who was 27 years his junior. Whatever the dynamic might have been with the kids from his first marriage, one of them—Robert Malcom, Jr.—did eventually join the executive board of the Chicago Eye Shield Co. . . . though that doesn’t necessarily suggest a close relationship.

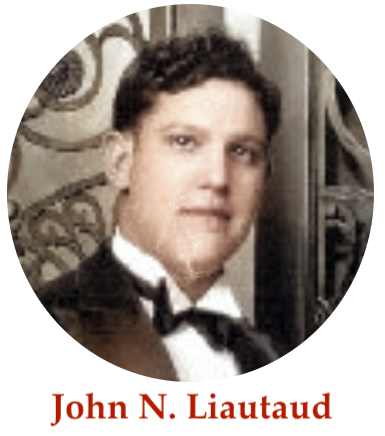

During the 1920s, another member of the Malcom family—Robert Sr.’s older brother Guy A. Malcom—joined the CESCO board, as well. But he was based in Oregon and likely not active in the day-to-day of the business. Those responsibilities were left more in the hands of a young wiz kid named John N. Liautaud, who was already Chicago Eye Shield’s general manager before the age of 30.

During the 1920s, another member of the Malcom family—Robert Sr.’s older brother Guy A. Malcom—joined the CESCO board, as well. But he was based in Oregon and likely not active in the day-to-day of the business. Those responsibilities were left more in the hands of a young wiz kid named John N. Liautaud, who was already Chicago Eye Shield’s general manager before the age of 30.

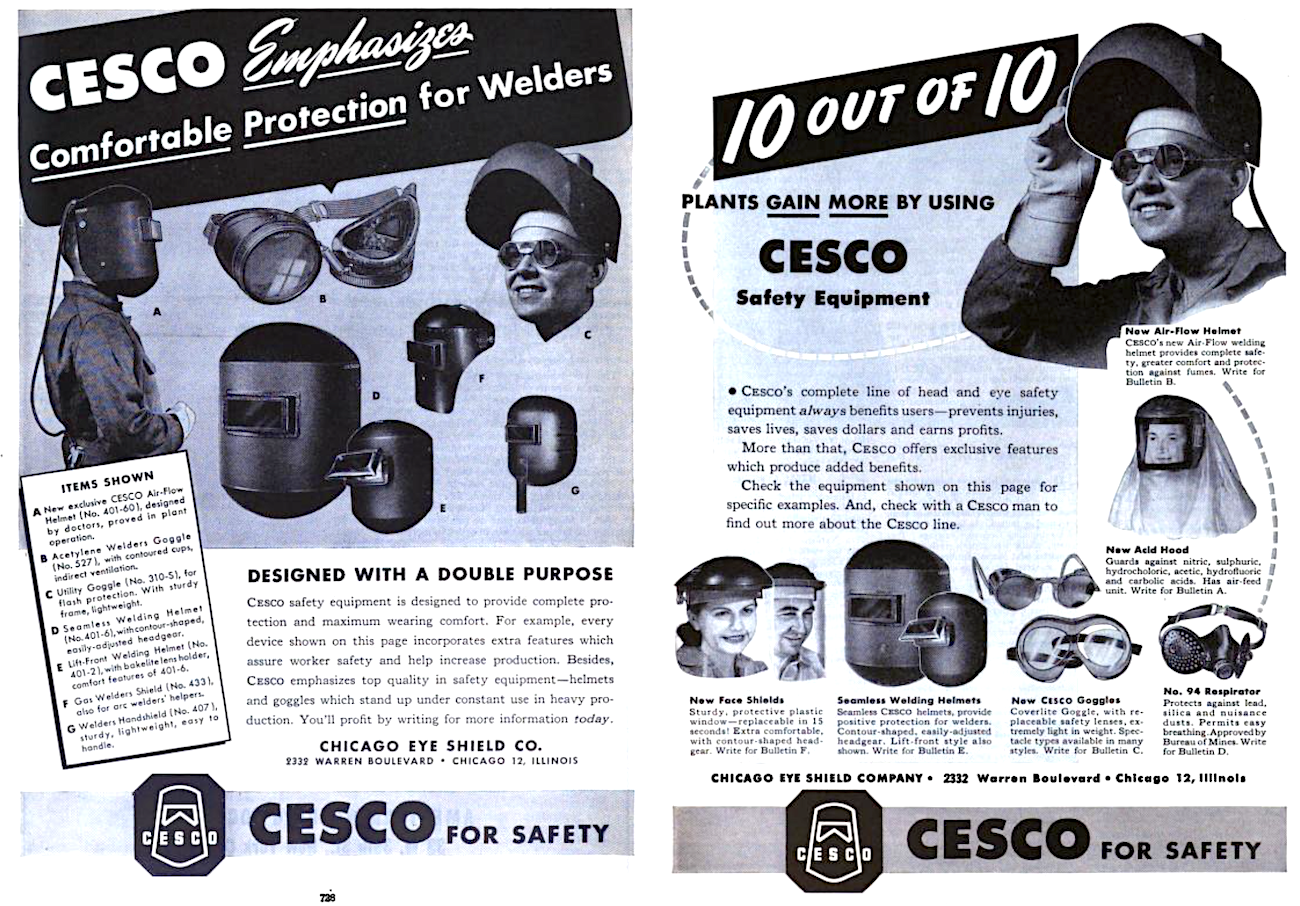

Together, Robert Malcom and John Liautaud made sure CESCO remained on the cutting edge, employing a team of researchers, optical experts, engineers, and designers to keep improving their product line. Malcom usually got the credit for these innovations, which included the first bakelite goggles for welding (1924), a one-piece positive pressure sandblast mask (1930), the comfort bridge goggle (1937), and a deluge of advanced “air-flow” welding helmets and face shields that were patented for the benefit of workers in defense plants during World War II.

[Promo flyer from 1945, featuring CESCO products for welders, including the Air-Flow Helmet, Acetylene Goggles, the No. 94 Respirator, and face shields]

III. CESCO Safety Products

“As you’re looking through these new CESCO Cover-Lite Safety Goggles you’re practically experiencing their comfort—because when you actually have them on, you scarcely know they’re there.” —Chicago Eye Shield Co. ad, 1944

Another wartime innovation from Robert Malcom’s team was the Cover-Lite Goggle, which weighed less than an ounce and included plastic, replaceable lenses. The design was the launchpoint for the later 1950s model seen in our museum collection.

Another wartime innovation from Robert Malcom’s team was the Cover-Lite Goggle, which weighed less than an ounce and included plastic, replaceable lenses. The design was the launchpoint for the later 1950s model seen in our museum collection.

“This new Cover-Lite model was developed after exhaustive research to aid safety directors in strengthening their safety programs,” explained CESCO sales manager Fred Guilbert in a 1944 promo. “We sincerely believe it will help solve eye injury problems because it provides good protection and is so comfortable to wear. . . . The Cover-Lite is suited for women or men workers, is designed to fit varying facial widths and may be worn directly over prescription glasses. Air space eliminates fogging, while the strong plastic frame not only protects the entire eye area, but also shields against distracting reflections and eye strain.”

During the war, the U.S. government mandated safety goggles for defense workers in most factories, which proved plenty lucrative for CESCO. But when peacetime returned, the business had to re-set to ensure its place in the free market.

“It was a very small company,” Leonard Bruce, a former CESCO distributor, recalled in a 1980 interview. “Management was trying to determine how to better market their products, because most of their products were being sold through government contracts.”

The solution that Malcom and his advisors came to was to create a program for training a network of distributors under the franchised name of the Guardian Safety Equipment Co., which would sell CESCO products as well as other non-competitive safety gear by other manufacturers. The idea was ahead of its time, but some of Guardian’s distributors soon grew stronger than CESCO itself, and started going independent—Leonard Bruce, for example, formed the multi-million dollar Vallen Corporation as a spin-off of his Guardian distributorship in Houston, Texas. Even for a company in the safety business, there was no guaranteed means of protecting your own neck.

In 1948, Malcom—now approaching his 80th birthday—appointed his son Robert Malcom, Jr. to the role of president and chief development engineer. It wasn’t necessarily a case of pure nepotism; Malcom Jr. was an aeronautical engineer and a smart cookie in his own right.

After 20 years with the business, though, VP John Liautaud might not have appreciated the selection, considering that Malcom Jr. was 10 years younger than himself. As such, by 1950, Liautaud left CESCO to start his own rival business, the Fendall Company, which operated in Chicago and Arlington Heights for the next several decades (Liautaud’s son, John R. Liautaud, would later develop a portable eye-wash station that’s still in use today, sold by Honeywell).

After 20 years with the business, though, VP John Liautaud might not have appreciated the selection, considering that Malcom Jr. was 10 years younger than himself. As such, by 1950, Liautaud left CESCO to start his own rival business, the Fendall Company, which operated in Chicago and Arlington Heights for the next several decades (Liautaud’s son, John R. Liautaud, would later develop a portable eye-wash station that’s still in use today, sold by Honeywell).

When Robert Malcom, Sr. died in 1953, aged 83, trade magazines reported that he had still been “actively engaged in the business up until two days before his death.”

“The safety industry has lost one of its staunchest supporters,” reported Industry and Welding Monthly.

As the new president of Chicago Eye Shield, Robert Malcom, Jr., tried to follow the business model that had helped the firm succeed for a half century. He contributed to the development and patenting of new designs on the ground floor, and in 1957, he moved the business to a larger factory space at 2711 West Roscoe Street. This was during a time when many large manufacturers were fleeing for cheaper rents in the suburbs, so keeping the company within the Chicago city limits was somewhat novel.

“Our new plant will give us at least 50% more productive area,” Malcom Jr. said at the time.

As the 1960s unfolded, though, the familiar threat of foreign competition began to rear its head again, this time in the form of cheap safety gear from east Asia.

[CESCO’s final Chicago headquarters, seen above at 2711-2727 West Roscoe Street, is still standing as of 2022, ironically home to an animal eye care clinic.]

In 1964, sales manager and vice president John W. Eder, Jr., announced the re-branding of the firm from Chicago Eye Shield Company to CESCO Safety Products, Inc. The company continued operating out of its Roscoe Street HQ through the end of the 1960s, with Eder now in the president’s seat, but by 1973, it had relocated to Kansas City, ending seven decades as a Chicago original. The last mention we could find of the business was in 1981, as it appears to have been gradually washed away by cheaper imports.

Robert Malcom, Jr., who retired from CESCO in the early 1960s, went on to become a city councilman in the town of Belleair, Florida, where he also taught aerospace engineering at a local college. He died in 2003, aged 90.

Sources:

“The Robert Malcom Company was Incorporated . . . ” – San Francisco Chronicle, Oct 17, 1896

“Eye Goggles” – Automobile Review, Dec 17, 1904

“Auto Goggles” – National Druggist, June 1907

“Goggles” – Tariff Hearings Before the Committee on Ways and Means of the House of Representatives, Sixtieth Congress, 1908

“Makes Big Business From Small Beginning” – Office Appliances, December 1916

“New Factory for Chicago Eye Shield Company” – Office Appliances, July 1916

“Rich Man’s Suit Perils Name of His 2 Children” – Chicago Tribune, June 14, 1923

“New Plastic Safety Goggle Weighs Less Than 1 Ounce” – The Log, Vol. 39, 1944

“Robert Malcom Sr” (obit) – Chicago Tribune, Nov 30, 1953

“Robert Malcom, Sr.: 1871-1953” – Safety Maintenance and Production, Jan 1954

“CESCO Moves to Larger Quarters” – Industry and Welding, October 1957

“Safety First, Dream Later” – Financial Trend, Feb 11-17, 1980

“John Liautaud” (obit) – Chicago Tribune, Sept 16, 1986

I have put a pair of CESCO round, green safety glasses on eBay. The wearer was born in 1899 and used them when welding at home in Michigan. The logo etched into the glass is an equilateral triangle with point facing down within a circle. You have my permission to use any of the photos on eBay.

Did you use to be The Chicago Goggle for Automobilists, Engineers and Drivers?

If so, i have an old pair of your goggles, in their original box, that are for sale.

I have found a pair of these in what seems to be good condition. Box as well. Any information and or value would be great to know.