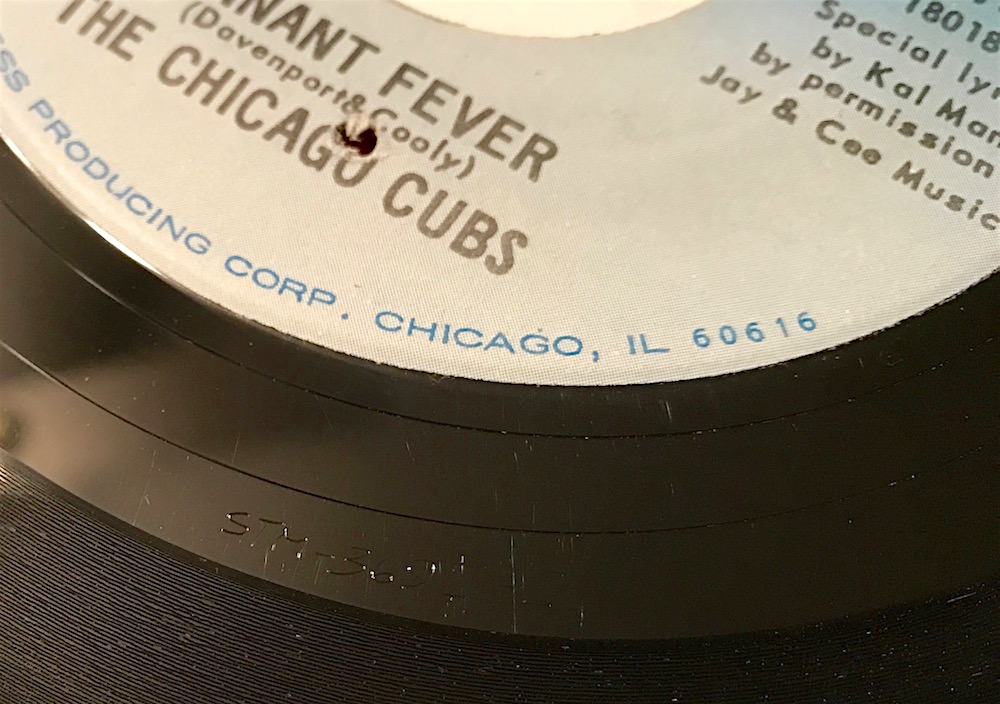

Museum Artifact: Chicago Cubs “Pennant Fever” 7-inch Record, 1969

Made By: Chess Producing Corp., 320 E. 21st Street, Chicago, IL [Near South Side]

Long before the Chicago Bears awkwardly rapped their way to a certified gold record with “The Super Bowl Shuffle,” the precedent for a singing sports team had already been set—albeit with substantially less commercial and cultural impact—by the baby bears over at Clark and Addison.

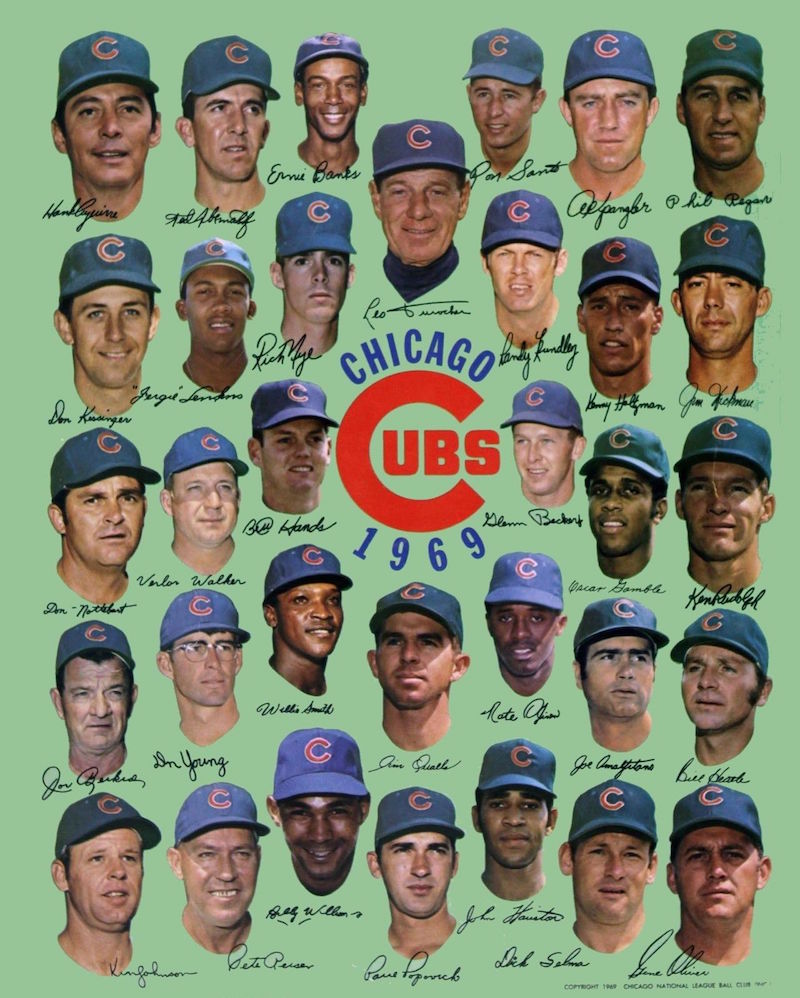

“Pennant Fever,” a funky pop ditty performed by seven members of the 1969 Chicago Cubs, has been largely forgotten by even the most devout Wrigleyvillians over the past 50 years. For those who did remember it, the tune offered little more than a sad reminder that the Cubbies did not, in fact, win the pennant that season—or any season since. . . . Until 2016, that is! Yes, with the “Curse of the Billy Goat” now officially vanquished, perhaps we can finally look back on this dusty 45 with a new appreciation—not just for its overlooked role in the Cubs’ most legendary collapse, but for the way it brought together two of Chicago’s most beloved institutions: the North Side’s baseball club and the South Side’s greatest hit factory, Chess Records (with all apologies to the Sox).

“Pennant Fever,” a funky pop ditty performed by seven members of the 1969 Chicago Cubs, has been largely forgotten by even the most devout Wrigleyvillians over the past 50 years. For those who did remember it, the tune offered little more than a sad reminder that the Cubbies did not, in fact, win the pennant that season—or any season since. . . . Until 2016, that is! Yes, with the “Curse of the Billy Goat” now officially vanquished, perhaps we can finally look back on this dusty 45 with a new appreciation—not just for its overlooked role in the Cubs’ most legendary collapse, but for the way it brought together two of Chicago’s most beloved institutions: the North Side’s baseball club and the South Side’s greatest hit factory, Chess Records (with all apologies to the Sox).

Part I: The Summer of ‘69

They might have been the “best days” of Bryan Adams’s life, but the summer of 1969 was quite the tumultuous time at the Chess Producing Corp., a 20 year-old record company entering a new era of uncertainty.

Earlier that year, the label’s founders, owners, and namesakes—brothers Leonard and Phil Chess—finalized a deal to sell the revered blues/jazz/soul imprint to a California-based reel-to-reel manufacturer, General Recorded Tape, Inc., or GRT. As part of the $6.5 million agreement, Chess Records would carry on with its Chicago production, and Leonard Chess’ 27 year-old son Marshall would serve as the label’s new president.

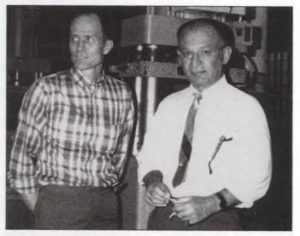

[Team Chess, just before selling their company to GRT in 1969]

[Team Chess, just before selling their company to GRT in 1969]

Unfortunately, the transition to life under West Coast corporate overlords was proving shaky out of the gate for the old family business—as funding shortages and creative differences quickly started testing young Marshall Chess’s patience. He’d been groomed for this role since boyhood—helping his dad cut records for everybody from Chuck Berry and Etta James to the Rolling Stones—so he wasn’t accustomed to red tape (or whatever other kind of tape GRT specialized in). As 1969 progressed, he let the music become his escape from the bureaucracy.

After producing two polarizing “psychedelic blues rock” albums with Chess veterans Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, Marshall decided to hit the rewind button and return to more of the traditional “pure blues” sound that had helped put Chess Records on the map. He recorded the Fathers & Sons LP with Muddy and other Chicago stalwarts (including Mike Bloomfield, Paul Butterfield, and Otis Spann) and released it in August to an excellent reception.

At almost the exact same time, early August of ’69, Chess also put out “Pennant Fever” (Recording No. 2075) to slightly less enthusiastic reviews. But hey, it was a feel-good novelty record! And it was tapping into a genuine, growing excitement that this Cubs team, after 61 years of heartache, might just be the real deal.

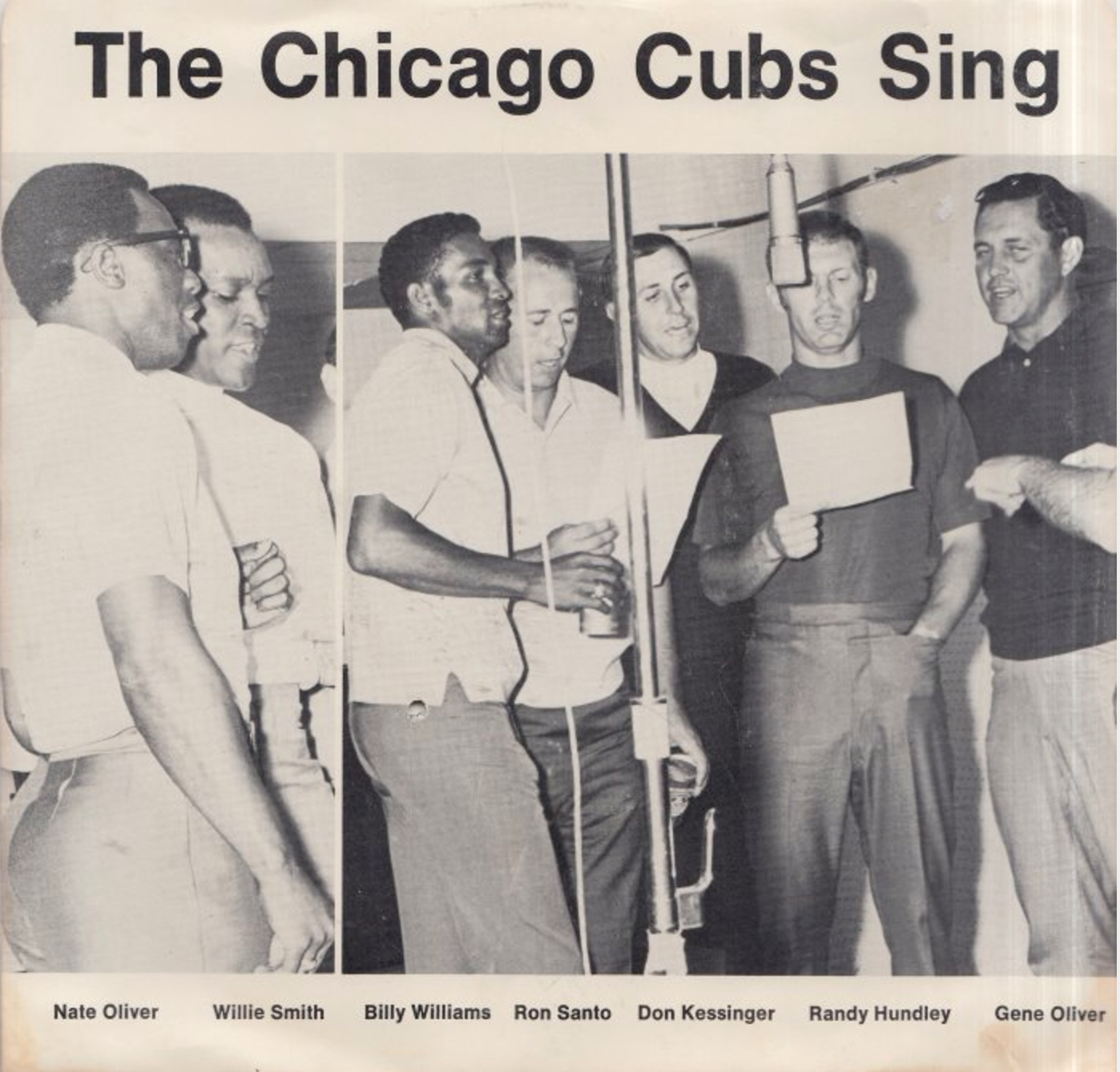

Some say it was the Cubs’ 64 year-old manager, that always colorful character Leo Durocher, who actually encouraged the idea of his boys warbling on a record. Others give the credit to backup catcher Gene Oliver. Either way, with the baseball season already halfway over and the Cubs still in the rarefied air of first place, the musical novelty project was thrown together hastily and sloppily to try and ride the wave.

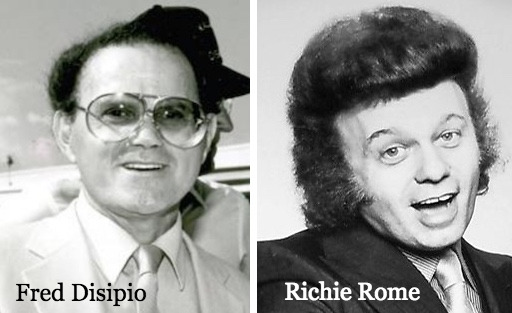

The actual recording session, oddly enough, didn’t take place at Chess Studios in Chicago. “We did it over in Philadelphia,” Cubs great Billy Williams recalled, adding that “they gave me a couple beers” to get in the spirit. Chess was increasingly outsourcing its recordings at the time, and for whatever reason, they called upon a pair of dyed-in-the-wool Philly guys—producer/promoter Fred DiSipio (incorrectly spelled “DeSipio” in the liner notes) and arranger Richard Rome—to handle a Chicago-themed project.

DiSipio—whose first claim to fame was supposedly surviving five days adrift at sea after the Battle of Leyte Gulf in WWII—would later become better known for his ties to the mob and crime boss John Gotti during a 1980s radio “payola” scandal. Survivor’s guilt, I guess.

DiSipio—whose first claim to fame was supposedly surviving five days adrift at sea after the Battle of Leyte Gulf in WWII—would later become better known for his ties to the mob and crime boss John Gotti during a 1980s radio “payola” scandal. Survivor’s guilt, I guess.

Richie Rome, meanwhile—in less spectacular fashion—became a fairly successful disco producer.

The Philly session in question went down on July 19, 1969, the night before Apollo 11 landed on the moon. Earlier in the day, on Earth, the visiting Cubbies had lost to a bad Phillies team in front of just 4,800 spectators. Chicago was still in first place, however, holding a 4-game lead over the Mets and taking their own small steps toward the goal of a giant leap.

And so—with a double header on the docket for the next day—the somewhat frazzled septet of Gene Oliver, second baseman Nate Oliver (no relation), outfielder Willie Smith, shortstop Don Kessinger, catcher Randy Hundley, and future Hall of Famers Billy Williams (left field) and Ron Santo (third base) put their vocal stylings on wax for the first and presumably last time.

[The rarely seen commercial cover art of “Pennant Fever,” proving that the Cubs really did sing, or at least stand in front of microphones. The generic Chess factory sleeve, like the one in our collection, is easier to find these days.]

[The rarely seen commercial cover art of “Pennant Fever,” proving that the Cubs really did sing, or at least stand in front of microphones. The generic Chess factory sleeve, like the one in our collection, is easier to find these days.]

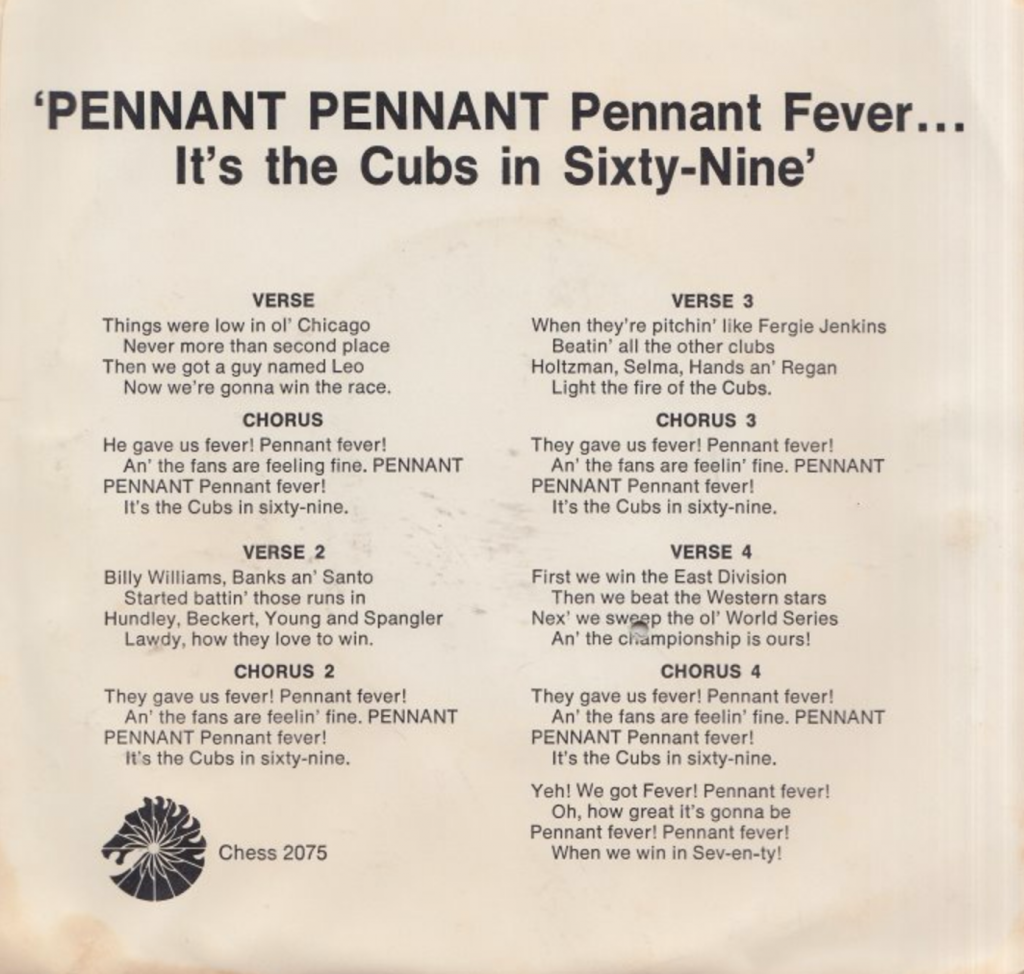

“Pennant Fever” was really more of a parody than an original tune, yoinking its melody from Little Willie John’s 1956 song “Fever,” which had also been a big hit for Peggy Lee. Chess managed to get the publishing rights from Jay & Cee Music Corp. They also hired a pretty accomplished Philadelphia lyricist, Kal Mann (Elvis Presley’s “Teddy Bear,” Chubby Checker’s “Let’s Twist Again”), to rewrite the words, turning “Fever” into a dangerously presumptuous Cubby fight song.

First we win the East Division

Then we beat the Western stars

Nex’ we sweep the ol’ World Series

An’ the championship is ours!

They gave us fever! Pennant fever!

Or not.

Unlike “The Super Bowl Shuffle,” there wasn’t a lot of thought into letting any of the individual Cubs have a moment in the spotlight. Instead, the recording opens with some highly distorted crowd noises, then blends the seven singing voices in such a manner that makes them mostly indistinguishable from one another. Nate Oliver and Willie Smith were supposedly doing the heavy lifting, but it may as well have been some anonymous session singers doing a Milli Vanilli thing. If you can’t tell who is singing, it kinda ruins the novelty a bit.

Meanwhile, the B-side of the record—an instrumental jam session that was probably just plucked from the Philly studio’s archive—was repackaged as the song “Slide” by the fictional Chicago Cubs Clark Street Band. I guess maybe they called it “Slide” because it’s a thing you do in baseball when running the bases. But then again, it’s also a term used to describe a slumping team falling out of first place and precipitously down the standings. This is why you don’t record Chicago sports anthems with Philadelphia musicians! Curses!

Part II: The Team Wasn’t the Only Thing Pressing

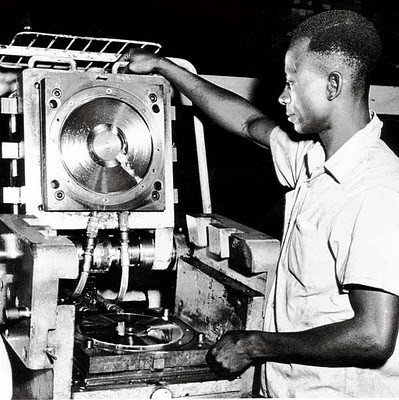

With the mixing and mastering of the recording done (presumably in about five minutes), the tapes of “Pennant Fever” and “Slide” were zapped back to Chicago, where they were turned into 7” vinyl discs at Chess’s new on-site “Ter-Mar” pressing plant (a play on the names of Phil Chess’s son Terry and Leonard’s son Marshall).

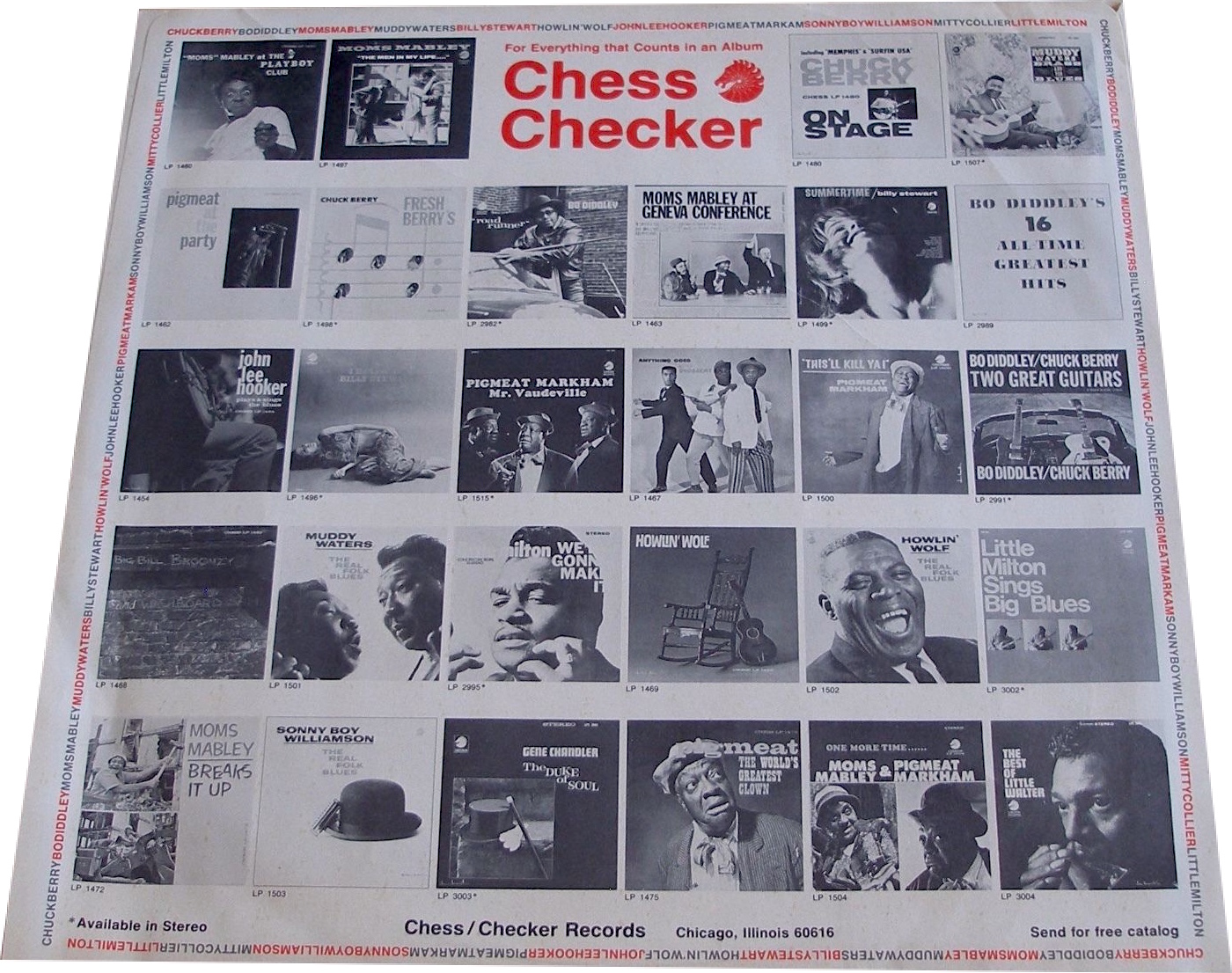

Part of the reason the Chess Producing Corp belongs in the Made In Chicago Museum is that their operation extended far beyond their famous recording studio. By the late ‘60s, after the company relocated to its final headquarters at 320 E. 21st Street, virtually every aspect of record making was handled in that one facility—producing, editing, pressing, photography, liner notes, printing, packaging, shrink wrapping, shipping, etc. It was very much a factory atmosphere.

During the height of vinyl record sales in America (and still to a lesser extent today), there were countless independent pressing plants that worked as hired guns for record companies, getting their products on wax and out to the public in a hurry. In its early years, Chess had outsourced its pressing to factories in Memphis, Nashville, and Indianapolis. Finally, in the late 1950s, when the company moved into its soon-to-be-famous studio space at 2120 S. Michigan Ave, Leonard Chess hired an old pro from Memphis named James Gann [pictured above with Leonard] to turn the former Chess headquarters at 4750 S. Cottage Grove Avenue into a state-of-the-art pressing plant. This operation became “Midwest Record Pressing, Inc.,” which made records for Chess and many other companies through the 1960s. Jimmy Gann eventually migrated over to help run the Ter-Mar pressing operation at 320 E. 21st Street, as well.

During the height of vinyl record sales in America (and still to a lesser extent today), there were countless independent pressing plants that worked as hired guns for record companies, getting their products on wax and out to the public in a hurry. In its early years, Chess had outsourced its pressing to factories in Memphis, Nashville, and Indianapolis. Finally, in the late 1950s, when the company moved into its soon-to-be-famous studio space at 2120 S. Michigan Ave, Leonard Chess hired an old pro from Memphis named James Gann [pictured above with Leonard] to turn the former Chess headquarters at 4750 S. Cottage Grove Avenue into a state-of-the-art pressing plant. This operation became “Midwest Record Pressing, Inc.,” which made records for Chess and many other companies through the 1960s. Jimmy Gann eventually migrated over to help run the Ter-Mar pressing operation at 320 E. 21st Street, as well.

Chicago had quite a few other pressing plants churning out tunes in tangible form—including independents such as Sheldon and Stereo Sound, and satellite plants run by the big boys like RCA Victor and Columbia. Just about every vinyl record made during this era included a code or etching in the inner groove or “deadwax” that revealed which pressing plant it came from, regardless of which record company may have produced or released it. It was an industry within the industry; the production line behind the hit parade.

By the late ‘60s, with Chess pressing most of its records in-house, the turn-around times were lightning fast. “Literally, I could record on a Wednesday and put a record on the radio on Thursday,” Marshall Chess recalled.

This meant that you could actually write and record a “timely” single about a baseball team in a pennant chase and have it packaged and in a DJ’s hand before the team played its next game.

[The STM in the etched in the deadwax of “Pennant Fever” suggests it was pressed at Chess’s own “Ter-Mar” plant]

[The STM in the etched in the deadwax of “Pennant Fever” suggests it was pressed at Chess’s own “Ter-Mar” plant]

Part III: No Joy in Wrigleyville

By the middle of August, when “Pennant Fever” started popping up on the radio, the Cubs held a season-high 9-game lead atop their division. Two weeks later, that advantage had shrunk to 4.5 games, but the Chicago Tribune reported that 21,000 copies of a “Pennant Fever” had already been sold to eager fans. They were still feeling it!

Then it began . . . a disastrous 8-game losing streak that would go down in baseball lore. It was during this slide, while playing the Mets in a critical game at New York’s Shea Stadium on September 9, that the infamous black cat appeared by the Cubs dugout, circling vocalist Ron Santo as he warmed up in the on-deck circle. The next night, the Cubs were back in Philadelphia, where it all began, and promptly dropped two straight games to the last-place Phillies, officially knocking Chicago out of first place for the first time all season. Fred Disipio, Richie Rome, and Kal Mann were probably in attendance, rubbing their hands like flies.

Then it began . . . a disastrous 8-game losing streak that would go down in baseball lore. It was during this slide, while playing the Mets in a critical game at New York’s Shea Stadium on September 9, that the infamous black cat appeared by the Cubs dugout, circling vocalist Ron Santo as he warmed up in the on-deck circle. The next night, the Cubs were back in Philadelphia, where it all began, and promptly dropped two straight games to the last-place Phillies, officially knocking Chicago out of first place for the first time all season. Fred Disipio, Richie Rome, and Kal Mann were probably in attendance, rubbing their hands like flies.

As any Cubs fan knows, of course, there would be no recovery. The team staggered down the stretch and finished a whopping 8 games behind the “Miracle” Mets.

Exactly two weeks later, on the same day the Mets won the World Series, Chess Records suffered a devastating blow of its own. Leonard Chess, the man who’d built the company into a cultural treasure, died at just 52 years of age. The supposed cause of death, bizarrely enough, was “broken heart syndrome,” aka stress cardiomyopathy. He’d never quite adjusted to life after the record biz.

[Leonard Chess]

Part IV: The Ultimate Indie Label

The death of Leonard Chess marked the end of an era. Starting out as young club owners on the South Side in the 1940s, Leonard and his younger brother Phil—Jewish immigrants from Poland—had spent the better part of 30 years opening their doors not just to a predominantly black audience, but to an exciting new wave of black music.

In 1947, Leonard decided that if the artists playing at his club wanted to start recording, he might as well record them himself. The Chess Brothers took over a tiny local record company, Aristocrat Records, with an office space at 2300 E. 71st Street.

[The very first Chess Brothers / Aristocrat Records office was here at 2300 E. 71st St. in 1947]

[The very first Chess Brothers / Aristocrat Records office was here at 2300 E. 71st St. in 1947]

From there, Leonard went to work—not just finding ways of recruiting, recording, and producing new talent—but distributing their records to buyers small and large; mostly in the black community. He even traveled the Midwest with a wire recorder in his car, just in case he needed to give a new prospect an on-the-spot audition.

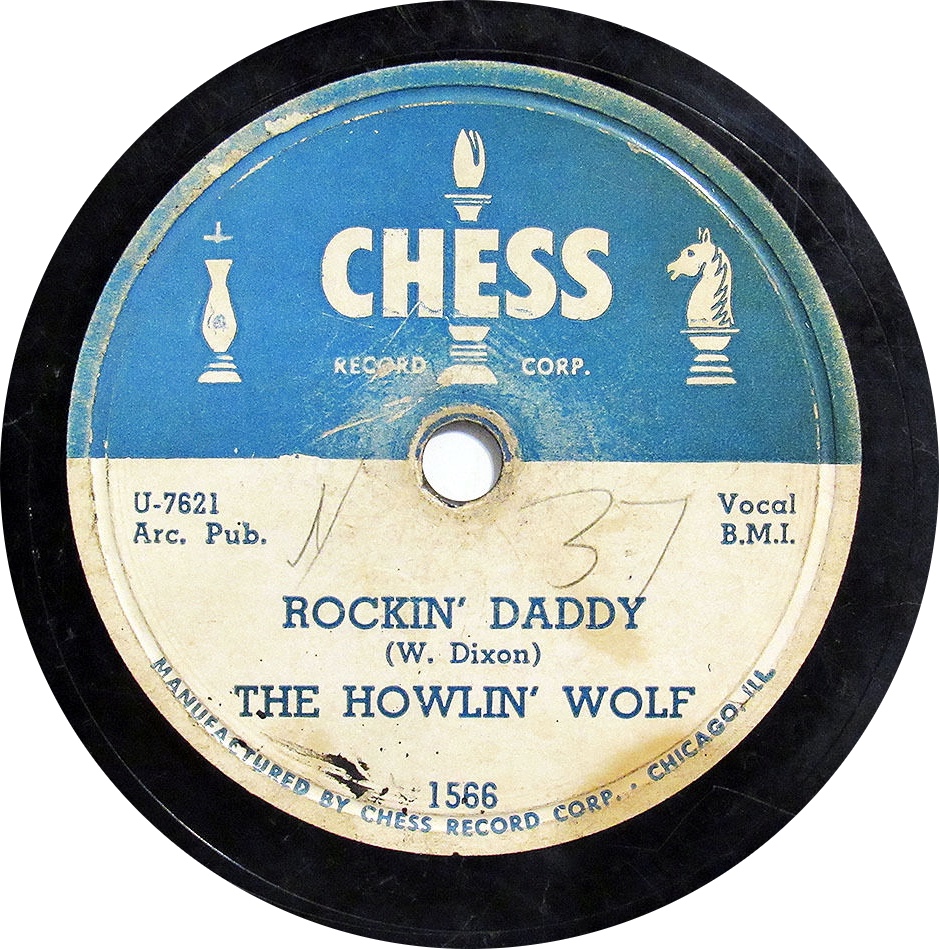

Aristocrat Records officially became Chess Records in the summer of 1950, and the glory days had begun. A steady stream of great jazz artists, doo-wop groups, and groundbreaking bluesmen—many having moved to Chicago from the Mississippi Delta during the Great Migration—wound up passing through the doors of Chess Studios, first at its humble South Cottage Grove locations, and then on to 2120 S. Michigan. These musicians would not only establish the “Chicago Sound,” they’d lay the groundwork for rock n’ roll in America and overseas. We’re talking about Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Little Walter, Sonny Boy Williamson, Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry, Etta James, Buddy Guy, Koko Taylor, the list goes on and on.

Even as Chess Records crossed into the mainstream, it remained a surprisingly small, DIY business through much of the ‘50s and ‘60s. The full staff counted just 15 people when the Michigan Avenue studio opened in 1957, and Leonard and Phil Chess remained right there through it all—not just running the business—but still recording the talent, as well. They also expanded their attention into the broadcasting end of the equation, buying and operating several prominent black radio stations.

[Phil Chess “conducting” Muddy Waters, Little Walter & Co. Michael Ochs Archives.]

[Phil Chess “conducting” Muddy Waters, Little Walter & Co. Michael Ochs Archives.]

The Chess Record Group, which included the subsidiaries Checker and Cadet, was bursting its seams with success by the mid 1960s, as the spotlight shined it on it by famous admirers like the Rolling Stones led to sky-high sales figures and overdue recognition for Muddy Waters and other Chicago blues masters. The Stones had even swung by the studio themselves in 1964 and recorded their second EP, complete with an instrumental tribute song titled “2120 South Michigan Avenue.”

Though the love and promotion from the British Invasion bands helped introduce Chess to an even wider audience, it also may have forced the company out of its comfort zone and closer to its eventual doom.

[The Chess studio and office at 2120 S. Michigan was used from 1957-1966]

[The Chess studio and office at 2120 S. Michigan was used from 1957-1966]

Part V: Outro

Desperately in need of a larger facility, the Chess Brothers moved Chess/Checker/Cadet into a big brick high-rise at 320 E. 21st Street in 1966, the former headquarters of the Revere Camera Company. For the first time, they had their entire business in one location, but there were unexpected consequences.

[The largest and ultimately last Chess building at 320 E. 21st St., as seen in 2006 (left) and after getting converted into lofts in 2010]

[The largest and ultimately last Chess building at 320 E. 21st St., as seen in 2006 (left) and after getting converted into lofts in 2010]

The aforementioned on-site pressing plant, for example, wreaked havoc on the recording studio. A rumbling hum from the plant’s hydraulic system somehow moved through the building’s elevator shaft and through the studio’s soundproofing, frustratingly making its way onto tape. The solution was to schedule pressing and recording times around each other, largely defeating the whole purpose of the all-in-one building. It also forced a lot of outsourcing of both processes—leading to scenarios like recording a Chicago Cubs record in Philadelphia.

“We made a big mistake,” Jimmy Gann told Leonard Chess. “We never should have moved in there.”

By 1968, the Chess Brothers were getting a bit overwhelmed with the faster pace and wider scale of things, and decided to focus more on radio. They began looking into potential buyers for the label they’d spent two decades shepherding through a changing world.

By 1968, the Chess Brothers were getting a bit overwhelmed with the faster pace and wider scale of things, and decided to focus more on radio. They began looking into potential buyers for the label they’d spent two decades shepherding through a changing world.

And that takes us back to where we began.

In the aftermath of Leonard Chess’s death, his son Marshall—who’d been promised a million dollars as part of the GRT buyout of the company months earlier—found that circumstances had changed.

“The bottom fell out of that dream,” Marshall claimed in the book According to the Rolling Stones. “My father died in October 1969, and he died without a signed will. Some vast percentage of his estate went to the government in taxes. There was no million bucks.”

The execs at General Recorded Tape, the new owners of the Chess Empire, weren’t delivering on their promises either.

“[They] seemed only interested in budgets and forecasts,” Marshall Chess said, “whereas the company had always been focused on creativity. I was very depressed, so I quit.”

With no more Chess men working at Chess, and GRT cutting staff and moving offices to New York and Los Angeles, many saw the writing on the wall in 1970. The label’s new executive vice president, Richard Salvador, tried to calm these concerns in an interview with Billboard that summer.

“There’s great talent here in Chicago,” he said, “but if we want to expand we have to have access to talent on both coasts. But we’re here to stay in Chicago! I’m never going to move out of Chicago as far as I’m concerned—Chicago’s too valuable.”

“There’s great talent here in Chicago,” he said, “but if we want to expand we have to have access to talent on both coasts. But we’re here to stay in Chicago! I’m never going to move out of Chicago as far as I’m concerned—Chicago’s too valuable.”

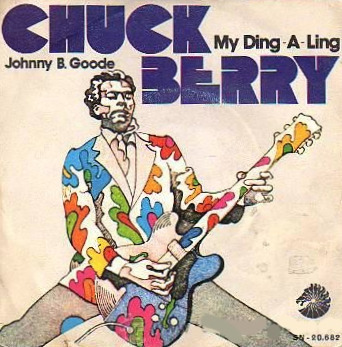

As is usually the case when an executive repeats the name of a city four times and guarantees he will never leave, Chess did leave Chicago. It did so rather quietly, too, folding into GRT’s Janus label in 1972 and essentially disintegrating out of existence by 1975. The final Chicago hurrah had been Chuck Berry’s 1972 cover of “My Ding-a-Ling,” which became the first No. 1 hit for both Berry and Chess, sadly enough.

Through a series of acquisitions over the ensuing 30 years or so, Universal Music Group now owns the original Chess recordings.

“Phil and Leonard Chess were cuttin’ the type of music nobody else was paying attention to,” blues great Buddy Guy told the Sun Times in 2016. “Muddy, Howlin’ Wolf, Little Walter, Sonny Boy, Jimmy Rogers, I could go on and on – and now you can take a walk down State Street today and see a portrait of Muddy that’s 10 stories tall. The Chess Brothers had a lot to do with that. They started Chess Records and made Chicago what it is today, the Blues capital of the world. I’ll always be grateful for that.”

On October 18, 2016, Phil Chess—age 95—died in his home in Arizona. Days later, the Chicago Cubs finally won the pennant.

[Chess artist Bo Diddley on the Ed Sullivan Show, 1955, inventing rock n’ roll]

[Howlin’ Wolf, “Meet Me at the Bottom”]

[Phil Chess with Etta James]

[Phil Chess with Etta James]

Sources:

Spinning Blues Into Gold: The Chess Brothers and the Legendary Chess Records, by Nadine Cohodas

City of Chicago: “Chess Records Office and Studio”

Brown Eyed Handsome Man: The Life and Hard Times of Chuck Berry, by Bruce Pegg

Billboard, August 22, 1970

Anoraks Corner: “Pressing Plant Info”

Hit Men, by Fredric Dannen

According to the Rolling Stones, edited by Mick Jagger, Dora Loewenstein, Philip Dodd, Charlie Watts