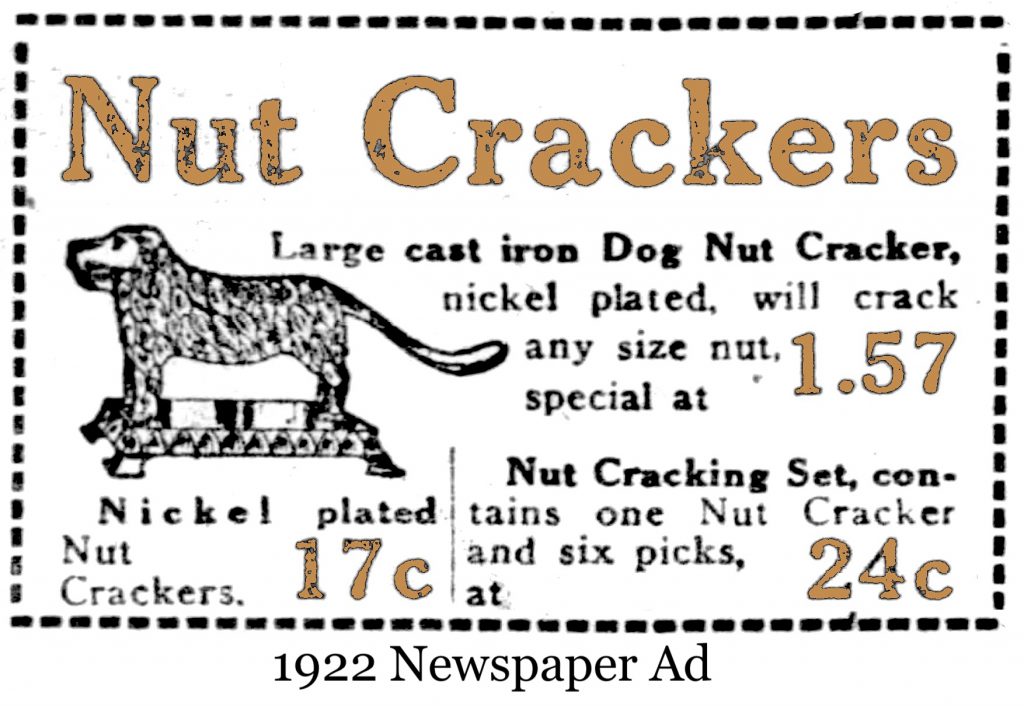

Museum Artifact: Cast-Iron Dog Tray Nut Cracker, 1899

Made By: Harper Supply Co. (40 Dearborn St, Chicago) / Chicago Hardware Foundry Co. (2500 Commonwealth Ave., North Chicago, IL)

“It is a fact that the successful sale of any product is dependent upon the genuineness of the need for which it is manufactured.” —Earl P. Sedgwick, co-founder and president of the Chicago Hardware Foundry Company

While Mr. Sedgwick wasn’t referring specifically to dog-shaped nutcrackers in the quote above (it actually comes from a 1926 newspaper ad for the “Sani-Dri”—his company’s early attempt at an electric hand dryer), he was indeed the man responsible for the sad-eyed metal mutt in our museum collection (U.S. patent No. 660033A – “Nut-cracker”). As such, Sedgwick’s stated philosophy on successful merchandising begs the question: just which “genuine need” of society was the Dog Tray Nut Cracker meant to address when it debuted in 1899?

Were people clamoring for a heavy cast-iron doorstop that could also de-shell uncooperative snack foods? Or was it the canine manifestation of such an implement—with a humorous tail-operated mechanism—that actually appeased the demands of the masses?

Were people clamoring for a heavy cast-iron doorstop that could also de-shell uncooperative snack foods? Or was it the canine manifestation of such an implement—with a humorous tail-operated mechanism—that actually appeased the demands of the masses?

Either way, our nicely patinaed pooch offers a pretty useful case study in how the so-called “genuineness of need” can evolve over time. By the 1940s, many of America’s once beloved bronze nutcrackers were suddenly deemed expendable contributions to the war effort, as scrap drives led to the demise of thousands of slack-jawed iron dogs, squirrels, birds, and alligators—not to mention many similar figural coin banks and bookends.

In a newsletter published by the Still Bank Collectors Club of America in 1985, researcher Bruce Abell spoke with a former Chicago Hardware Foundry employee—by then in his 80s—who also recalled breaking up all the original brass pattern molds from the company vaults in 1942, “when our country needed brass so badly.”

Now, in the grand scheme, losing the original industrial mold of a dog nutcracker hardly ranks among the more significant consequences of World War II. But it does at least explain the pathetic expression on our artifact’s face. He is, sadly, among the last of his kind.

I. The Artifact

Our particular Dog Tray Nut Cracker was produced as a joint venture between the Chicago Hardware Foundry Co.—which made the product in its sprawling works in North Chicago (a small town about 40 miles north of regular Chicago)—and the Harper Supply Company, a Chicago-based business focused on the design and distribution of various small iron castings, including coin banks, caster wheels, clothes irons, etc. Both companies were established in 1897, and there seemed to be a symbiotic relationship in effect almost from the beginning.

Over the years, anything animal-shaped coming out of the North Chicago foundry was usually attributed to Harper Supply and its president, James M. Harper—who is best remembered for his highly collectable figural coin bank designs.

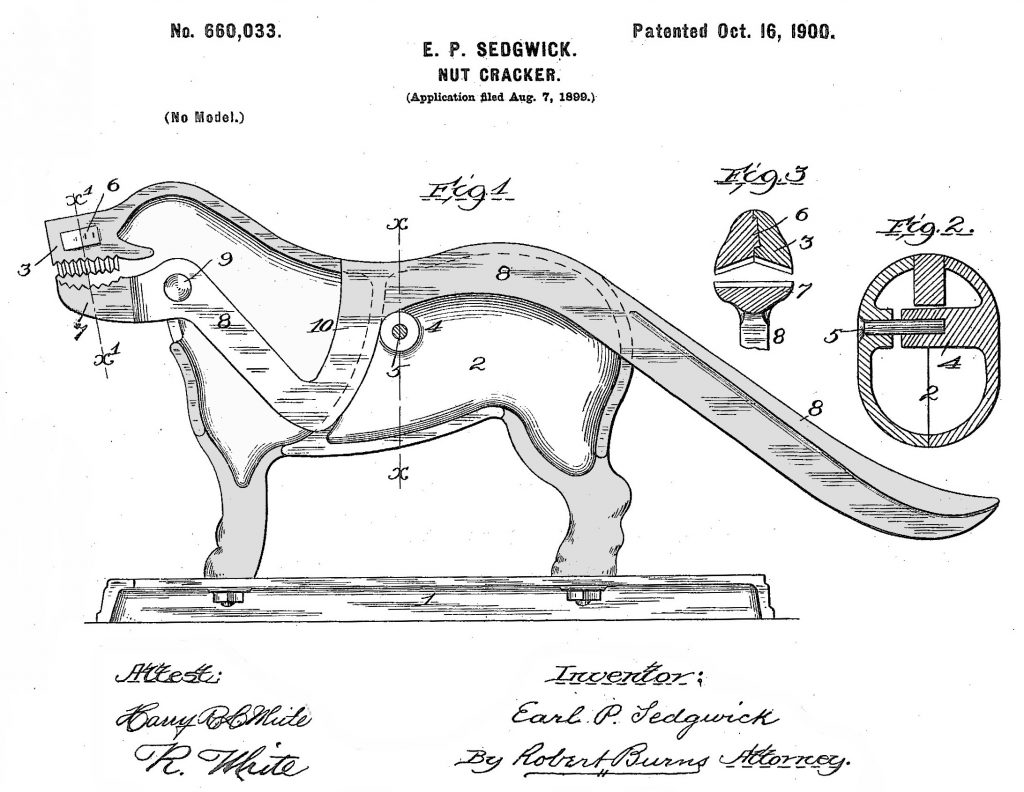

Not surprisingly, the dog nutcracker—which has the “Harper Supply Co.” name plastered on its base—often gets grouped in with J. M. Harper’s other cast-iron critters of the same era. As noted, though, this dog was actually created and patented by one of the foundry heads, Earl Sedgwick, who probably based the design on similar models already widely available in Europe. It’s also possible he might have been inspired by a real-life pooch named “Lemons”—the beloved companion of the foundry’s co-founder and first president, John Sherwin. That possibility is, of course, thoroughly unconfirmable. But Sedgwick’s 1899 patent application does reveal the technical intent of the device.

Not surprisingly, the dog nutcracker—which has the “Harper Supply Co.” name plastered on its base—often gets grouped in with J. M. Harper’s other cast-iron critters of the same era. As noted, though, this dog was actually created and patented by one of the foundry heads, Earl Sedgwick, who probably based the design on similar models already widely available in Europe. It’s also possible he might have been inspired by a real-life pooch named “Lemons”—the beloved companion of the foundry’s co-founder and first president, John Sherwin. That possibility is, of course, thoroughly unconfirmable. But Sedgwick’s 1899 patent application does reveal the technical intent of the device.

“The present invention,” he wrote, “more especially relates to that type of semiportable nut-crackers that are formed to present the outward appearance of an animal or other like figure standing upon a supporting base-plate, and in which the jaws of such figure constitute the jaws of the nut-cracker, the movable jaws being provided with a lever connection by which it is operated.

“The object of the present improvement is to provide a simple, cheap, and efficient construction and arrangement of parts in which the upper jaw of the animal constitutes the stationary jaw of the nutcracker, while the lower jaw is pivoted within the body to constitute the movable jaw of the nut-cracker . . . A lever extension constitutes the operating means of the appliance, and with this construction the natural outward appearance of the animal is preserved.”

[While Sedgwick’s nutcracker design was unique enough to earn a U.S. patent, he did not invent the dog nut cracker itself. Similar products had been around in England dating at least back to the early 1800s. Several other American companies also started producing their own versions not long after Sedgwick, including a popular competitor made by the L. A. Althoff Co., also of Chicago]

[While Sedgwick’s nutcracker design was unique enough to earn a U.S. patent, he did not invent the dog nut cracker itself. Similar products had been around in England dating at least back to the early 1800s. Several other American companies also started producing their own versions not long after Sedgwick, including a popular competitor made by the L. A. Althoff Co., also of Chicago]

The Dog Tray Nut Cracker earned its patent approval in 1900, the first such recognition in Sedgwick’s career, but hardly his crowning achievement.

II. History of the Chicago Hardware Foundry Co.

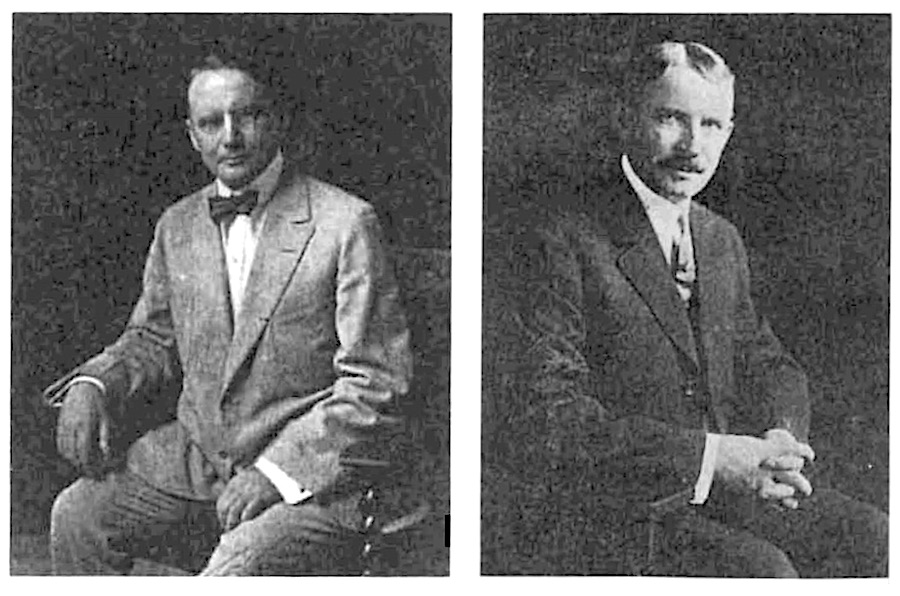

When E. P. Sedgwick (1867-1935) and John Sherwin (1859-1921) organized the Chicago Hardware Foundry Co. in the spring of 1897, it was under somewhat rebellious circumstances. Up until the previous year, both men were in the employ of an already flourishing North Chicago factory: the Chicago Hardware Manufacturing Co. Sedgwick, at age 30, had worked his way up to plant superintendent, while Sherwin, at 38, was the foreman.

After experiencing some creative differences with the ownership of that firm, however, Sedgwick and Sherwin asked if they could lease some factory space of their own to concentrate on small grey iron castings. Their bosses said “sure”—so like I said, it was merely a somewhat rebellious beginning. Nonetheless, it didn’t take long for this small side venture to turn into a fully realized, independent business, as Sedgwick (as secretary/treasurer) and Sherwin (as president) soon built their own plant directly across the street from the existing one, and gave their new company a nearly indistinguishable name from their neighbors: dubbing it the Chicago Hardware Foundry Co.

[Chicago Hardware Foundry founders Earl P. Sedgwick (left) and John Sherwin]

[Chicago Hardware Foundry founders Earl P. Sedgwick (left) and John Sherwin]

Understandably, this choice continues to create some major league headaches for historical researchers. Because while the original/older Chicago Hardware MFG Co. (aka simply the Chicago Hardware Company) remained in North Chicago as a lock and doorknob specialist up through 1950, Sherwin and Sedgwick’s Chicago Hardware Foundry Co. wrote its own completely separate history on virtually the same plot of land, over the same period.

To make matters more complex, Sedgwick and Sherman’s operation almost immediately matched and surpassed their old company in scope, with a specialty in high-grade castings and porcelain enamel fixtures. Their national sales team, led by William Lott, may or may not have been ethically compromised, pushing various machines of questionable effectiveness on unsuspecting townsfolk, including Lott’s Rapid Steam Washer, Kero-Air Burners, and the Acme Aerating Butter Extractor. But the results, in terms of the company’s growth, were hard to question.

To make matters more complex, Sedgwick and Sherman’s operation almost immediately matched and surpassed their old company in scope, with a specialty in high-grade castings and porcelain enamel fixtures. Their national sales team, led by William Lott, may or may not have been ethically compromised, pushing various machines of questionable effectiveness on unsuspecting townsfolk, including Lott’s Rapid Steam Washer, Kero-Air Burners, and the Acme Aerating Butter Extractor. But the results, in terms of the company’s growth, were hard to question.

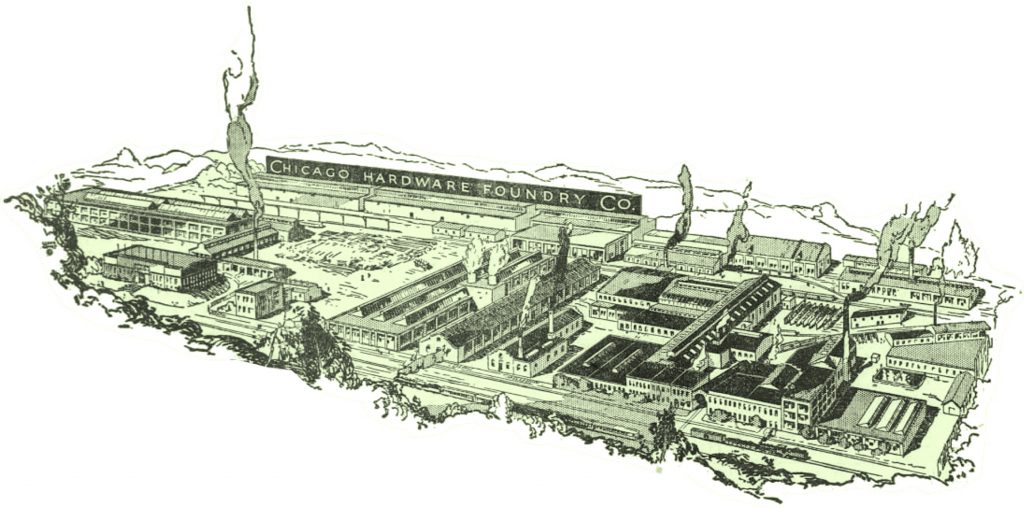

In the Factory Inspectors’ Report of 1898, the Chicago Hardware Foundry Co. had already hired 65 employees, while the Chicago Hardware MFG Co. had 60. Just five years later, the gap had grown to 300 to 85 in favor of the Foundry boys, and by 1908, it was 450 workers to 119 (all but a small handful of the employees at both firms, incidentally, were men).

[Overhead rendering of the Chicago Hardware Foundry Co. works in North Chicago, 1926]

[Overhead rendering of the Chicago Hardware Foundry Co. works in North Chicago, 1926]

As noted, the Foundry’s relationship with the Harper Supply Company was formed very early on, and may have been another helpful factor in their rapid development, as Earl Sedgwick seemed to have found a like-minded cast iron designer in the form of James M. Harper, whose patented caster wheels, fly traps, sad irons, nutcrackers, and stylized coin banks found a wide audience. Some of these smaller products might have been made at the foundry’s satellite location at 50 W. Washington Street in Chicago, although that facility only had a few workers on staff.

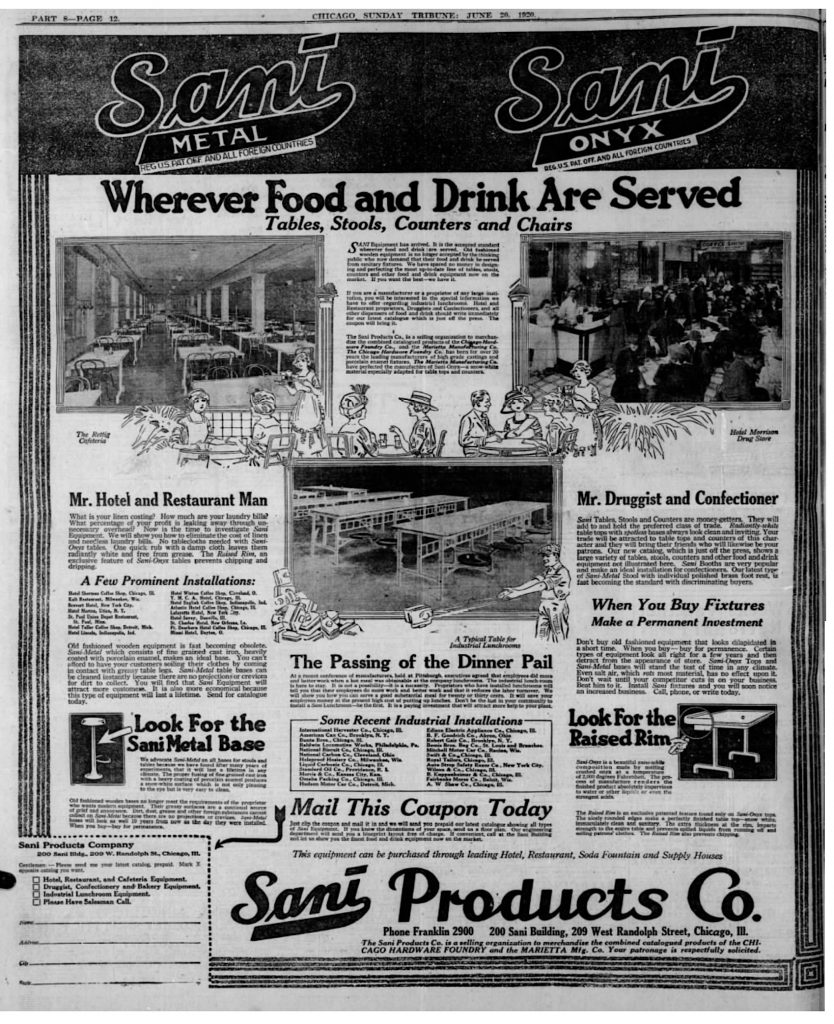

As their business boomed, E. P. Sedgwick and John Sherwin became luminaries of North Chicago, with each taking a turn as mayor of the small town while still running operations over at the foundry. After World War I, the aging tycoons also rediscovered some of their youthful gutsiness, launching a new business called the Sani Products Company—initially as a joint venture with the Marietta MFG Co. of Pennsylvania. The headquarters for Sani was located at 209 W. Randolph St. in regular Chicago, and an additional plant was eventually opened in Elkhart, Indiana.

“SANI Equipment has arrived,” read a full page 1920 ad in the Tribune. “It is the accepted standard wherever food and drink are served. Old fashioned wooden equipment is no longer accepted by the thinking public who now demand that their food and drink be served from sanitary fixtures. We have spared no money in designing and perfecting the most up-to-date line of tables, stools, counters and other food and drink equipment now on the market. If you want the best—we have it.”

“SANI Equipment has arrived,” read a full page 1920 ad in the Tribune. “It is the accepted standard wherever food and drink are served. Old fashioned wooden equipment is no longer accepted by the thinking public who now demand that their food and drink be served from sanitary fixtures. We have spared no money in designing and perfecting the most up-to-date line of tables, stools, counters and other food and drink equipment now on the market. If you want the best—we have it.”

That same year, in a private news bulletin sent to Sani Products staff, Sedgwick had a very optimistic outlook. “Our plants producing at record pace,” he wrote. “Finished stocks double those of a year ago. Unfilled orders greatly reduced, but still one to two months slow. . . . Strikes fewer. No decrease purchasing power evidenced. Bank officers almost unanimous money soon more plentiful. European war clouds dissolving.”

After Sherwin’s death in 1921, Sedgwick carried on developing the Sani brand, including a big push for the aforementioned Sani-Dri electric hand driers in the mid ‘20s, and—following a buyout of the Favorite Stove & Range Co. in 1934—a ramped up output of cast iron skillets and dutch ovens under the Sani-Ware name.

[1936 newspaper ad for Sani-Ware skillets and dutch ovens]

[1936 newspaper ad for Sani-Ware skillets and dutch ovens]

The Chicago Hardware Foundry Co. got through the Great Depression, but not without its fair share of challenges, and a whole lot of bad press.

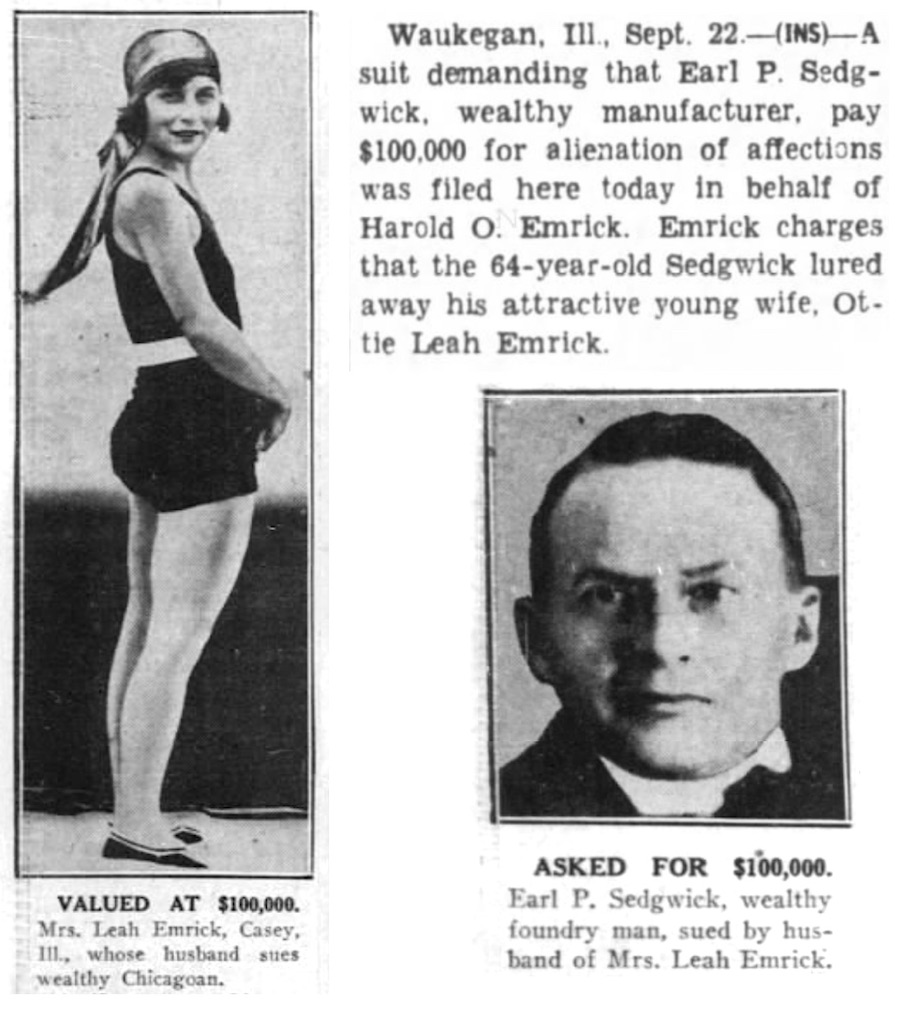

In 1931, a 64 year-old Earl Sedgwick’s good name was sullied by a bizarre tabloid scandal in which he was sued for $100,000 by an Illinois baker named Harold Emrick, who essentially accused the foundryman of stealing his wife. Apparently, Sedgwick had met Harold and Ottie Leah Emrick while the couple was vacationing in Palm Beach, FL, where Earl had a winter home. According to the official “alienation suit,” Sedgwick was so enthralled with the dancing skills of 28 year-old Ottie that “he suggested her coming to Chicago to take advanced lessons.” Ottie Leah took him up on the deal, and a short time later, went off to Reno to get a divorce from her husband—paid for by Sedgwick.

Considering Earl was married with three grown kids of his own, this was not a good look. But it’s not actually clear if a standard “affair” took place. Confiscated correspondence between Sedgwick and Mrs. Emrick was maybe more sad than scandalous: “Those four dances with you have amply repaid for the money I paid for your dancing lessons and put on deposit for you,” Sedgwick wrote. “I am delighted with your dancing.”

Just four years later, E. P. Sedgwick was dead at the age of 68, and with his passing, things got increasingly unstable at the plants of the Chicago Hardware Foundry Co., particularly in terms of labor relations.

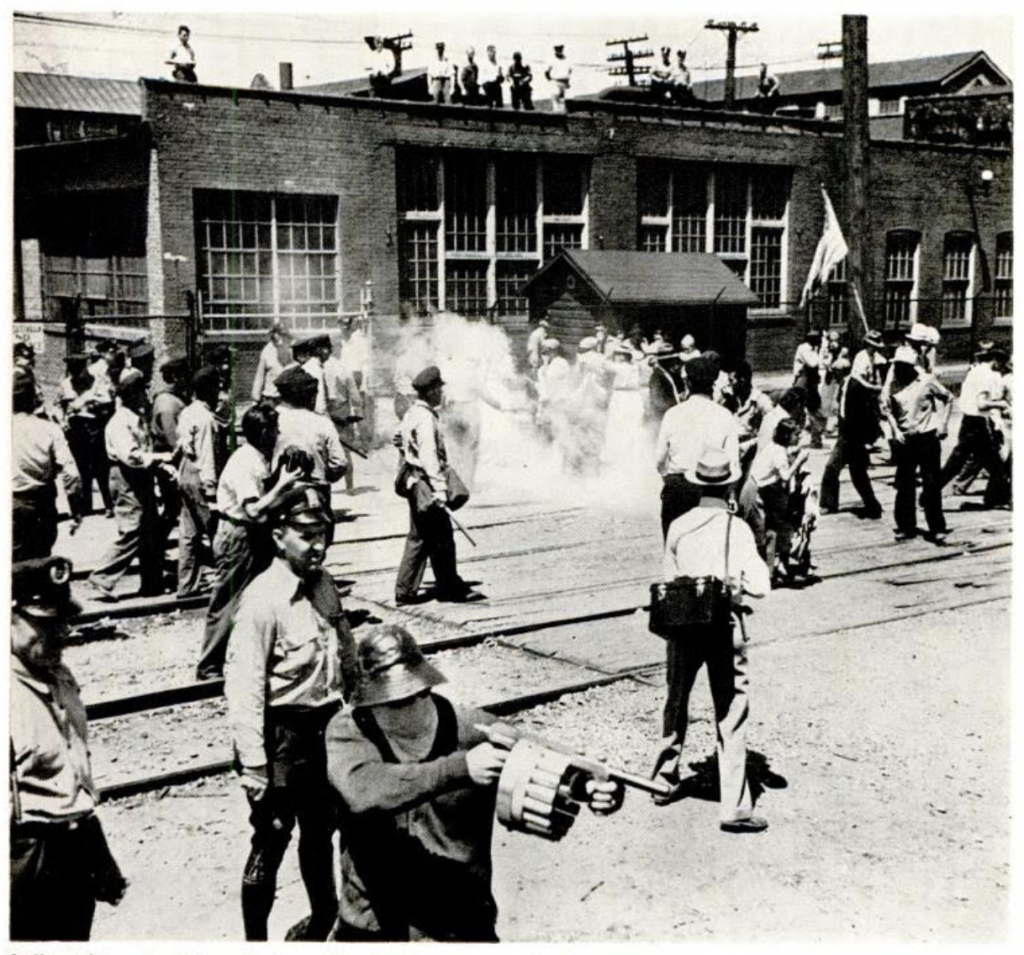

In 1938, with John Sherwin’s son Edward B. Sherwin now serving as president, the foundry made national headlines when an ongoing strike organized by the Amalgamated Iron, Steel & Tin Workers turned into a violent clash with police.

In 1938, with John Sherwin’s son Edward B. Sherwin now serving as president, the foundry made national headlines when an ongoing strike organized by the Amalgamated Iron, Steel & Tin Workers turned into a violent clash with police.

“Trouble started June 6 when a 10% wage reduction was decreed for all employes,” Life magazine reported. “The union, sole bargaining agent for the plant’s 450 workers, rejected the cut, began picketing when negotiations collapsed. On July 19 Sheriff Lawrence A. Doolittle, backed by a court order and 60 policemen, warned 300 pickets outside the plant they had just five minutes to ‘break it up.’ When the time limit expired the officers closed in. Tear-gas bombs and stones passed in flight. No one was seriously injured. Seven pickets were arrested.”

[Press photos from the 1938 riot at the Chicago Hardware Foundry in North Chicago include brutal images of tear gas being fired into a crowd, with some picketers wearing homemade gas masks in anticipation of it. Police were often rough on the workers who were arrested, as seen above, and the foundry’s growing number of women employees weren’t spared the misery, as you can see from the flag bearing woman wiping the effects of the tear gas from her eyes as she is led away]

[Press photos from the 1938 riot at the Chicago Hardware Foundry in North Chicago include brutal images of tear gas being fired into a crowd, with some picketers wearing homemade gas masks in anticipation of it. Police were often rough on the workers who were arrested, as seen above, and the foundry’s growing number of women employees weren’t spared the misery, as you can see from the flag bearing woman wiping the effects of the tear gas from her eyes as she is led away]

Worker uprisings became something of a regular occurrence after that, and the Foundry was singled out again in the years just after World War II for its potentially abusive exploitation of Puerto Rican workers, whom Edward Sherwin had flown in to take on jobs for menial wages.

“Fifty [Puerto Ricans] are working for the Chicago Hardware Foundry at 88 cents an hour,” according to a 1947 report, “but after deductions, their pay checks seldom run higher than $5 for a full week. . . . The foundry workers are housed in company-owned wooden railroad cars and are forced to buy their food and work clothes at a company store.”

Among the few positive stories the company received during this era was also related to railroad cars, as part of the Foundry’s campus at 2500 Commonwealth Ave. became the original site of the Illinois Electric Railway Museum in 1953. Frank J. Sherwin, who had replaced his brother Edward as company president by this point, was enthusiastic about railcar preservation. He also encouraged the museum’s subsequent move to more spacious grounds in 1964. The renamed Illinois Railway Museum ultimately settled in Union, IL, where it remains today, hosting one of the world’s largest collections of vintage railway equipment.

[Company president Frank Sherwin welcomed the first iteration of the Illinois Railway Museum on to his foundry grounds in the 1950s, including the railway car on the left, which was repurposed as the “C H F Co. storage car.” The car on the right, Indiana Railroad 65, was the very first to join the collection in 1953, and is seen here on CHF’s property in North Chicago. Courtesy of Illinois Railway Museum.]

[Company president Frank Sherwin welcomed the first iteration of the Illinois Railway Museum on to his foundry grounds in the 1950s, including the railway car on the left, which was repurposed as the “C H F Co. storage car.” The car on the right, Indiana Railroad 65, was the very first to join the collection in 1953, and is seen here on CHF’s property in North Chicago. Courtesy of Illinois Railway Museum.]

In 1963, Frank Sherwin moved up to chairman, and longtime employee Arthur W. Baker became company president, focusing most of the foundry’s work on one of its old standbys: industrial furniture. Sales were dwindling, however, and the next chapter looked like an 11.

In 1969, the company was put under the control of Illinco Corp., a New York holding company, and the diminishing North Chicago plant was shut down and liquidated, with surviving equipment transported up to another foundry in Racine, Wisconsin. A 1969 ad promoting a public auction of leftover tools and machines from the North Chicago foundry can be seen below.

The Sullivan Company, am Illinois furniture manufacturer, took ownership of the Racine plant and the remaining Chicago Hardware Foundry Company shares in 1971, but Sullivan itself was then subsequently sold in 1980.

The Sullivan Company, am Illinois furniture manufacturer, took ownership of the Racine plant and the remaining Chicago Hardware Foundry Company shares in 1971, but Sullivan itself was then subsequently sold in 1980.

As best we can tell, some bastardized version of the Chicago Hardware Foundry Co. continued to exist as late as 1988, with production in that same Racine foundry. When the company relocated to Grayslake, IL, that same year, they were promptly sued and defeated by the state of Wisconsin for having sent “excessive discharges of nickel and other toxic metals into Racine’s wastewater treatment system.” Coincidentally, 1988 was also the year that a major chemical fire at the foundry’s former North Chicago works essentially leveled the complex and any remaining treasure trove of cast iron relics that might have been hidden in the walls.

For what had once been a business characterized by ambition, innovation and novelty charm, the legacy wound up being a pretty mixed bag—an embarrassing misstep for every terrifically well made skillet.

III. History of the Harper Supply Co.

Of course, since our museum artifact was also a product of the Harper Supply Company, we’ll see fit to say a few words about that little enterprise, as well.

As noted, James Monroe Harper (1842-1928)—the mysterious wunderkind designer and inventor—was never actually an employee of the Chicago Hardware Foundry Co. himself, despite the close working relationship. In fact, as a point of distinction from most of his contemporaries, Harper appears to have wisely patented and retained the rights to his own metalware designs, rather than selling them off to larger assignees. This is really the main reason anyone knows his name at all, as “J. M. Harper” was etched into many of the mass produced cast-iron piggy banks that the Chicago Hardware Foundry Co. made in the early 1900s—leading modern collectors on the fruitless goose chase of finding all of Harper’s rare / mythical designs, including the “I Made Chicago Famous” pigs, the Teddy Roosevelt Portrait Bank, and the “Board of Trade” bank; featuring a bull and bear hugging a bag of money [pictured above].

As noted, James Monroe Harper (1842-1928)—the mysterious wunderkind designer and inventor—was never actually an employee of the Chicago Hardware Foundry Co. himself, despite the close working relationship. In fact, as a point of distinction from most of his contemporaries, Harper appears to have wisely patented and retained the rights to his own metalware designs, rather than selling them off to larger assignees. This is really the main reason anyone knows his name at all, as “J. M. Harper” was etched into many of the mass produced cast-iron piggy banks that the Chicago Hardware Foundry Co. made in the early 1900s—leading modern collectors on the fruitless goose chase of finding all of Harper’s rare / mythical designs, including the “I Made Chicago Famous” pigs, the Teddy Roosevelt Portrait Bank, and the “Board of Trade” bank; featuring a bull and bear hugging a bag of money [pictured above].

James Harper was born in Indiana; the son of a Virginia farmer, William Harper, who’d abandoned the South out of his hatred for slavery. James and his brother John—the oldest siblings among nine kids—were raised in the same spirit, and eventually registered for service with the Union Army during the Civil War. By then, the Harpers were living near the small town of El Paso in Woodford County, Illinois—about 120 miles southwest of Chicago.

We don’t know much of anything about James Harper’s military service (besides his survival), but by 1870, he pops up again in census records, now settled in El Paso, IL, with his wife Nellie. By this point, he’d also started to develop a trade designing and building farm equipment; plows and such. Harper was a fulltime hardware dealer by his mid 30s, partnering a while with his brother-in-law Samuel Mitchell as Mitchell, Harper & Company.

One of James’s first big breakthrough products was his patented caster wheel design, which was heavily promoted in the 1880s and remained part of his oeuvre into the 20th century. A set of cast iron Harper Stove Casters were strong enough to let people move their enormous Victorian stoves, as well as pianos, sewing machines, etc.

One of James’s first big breakthrough products was his patented caster wheel design, which was heavily promoted in the 1880s and remained part of his oeuvre into the 20th century. A set of cast iron Harper Stove Casters were strong enough to let people move their enormous Victorian stoves, as well as pianos, sewing machines, etc.

“A Great Want Filled!” read a newspaper ad from 1881, suggesting that Harper’s casters had a Sedgwick-approved genuineness of need. “It is a difficult matter to set up a stove right, and still more difficult to adjust it when up, but with a set of these Casters a stove can be moved by one person as easily as any article of household furniture.

“A Few of the Reasons Why They Are Better Than Others:

1st. They can be used under any stove—as well under one with only three legs as one with four.

2nd. One person can adjust them.

3rd. They can be used for moving any heavy article.

4th. They are cheaper than any other.

5th. They will last a lifetime with proper care.”

It’s not clear whether Harper was directly involved in the manufacture of the casters, but it’s likely he outsourced the work. It’s also hard to say how profitable the business was. By the rough economic times of the 1890s, Harper had focused a lot of his attention on the grain business instead, and only seemed to come back around to hardware again when the agricultural well dried up.

In 1897, at the age of 55, Harper finally made his way to Chicago, settling with his wife Nellie and daughter Jessie in a home on the South Side, and establishing the Harper Supply Company with a capital stock of $2,500. John F. Spalm and George C. Peeronet were Harper’s co-incorporators, and daughter Jessie D. Harper soon took on the role of company secretary (Jessie lived with her parents until their deaths, then lived on her own and worked in the millinery trade for the rest of her days). The first office was located at 59 Dearborn Street, with later moves to 40 Dearborn and 132 Lake Street.

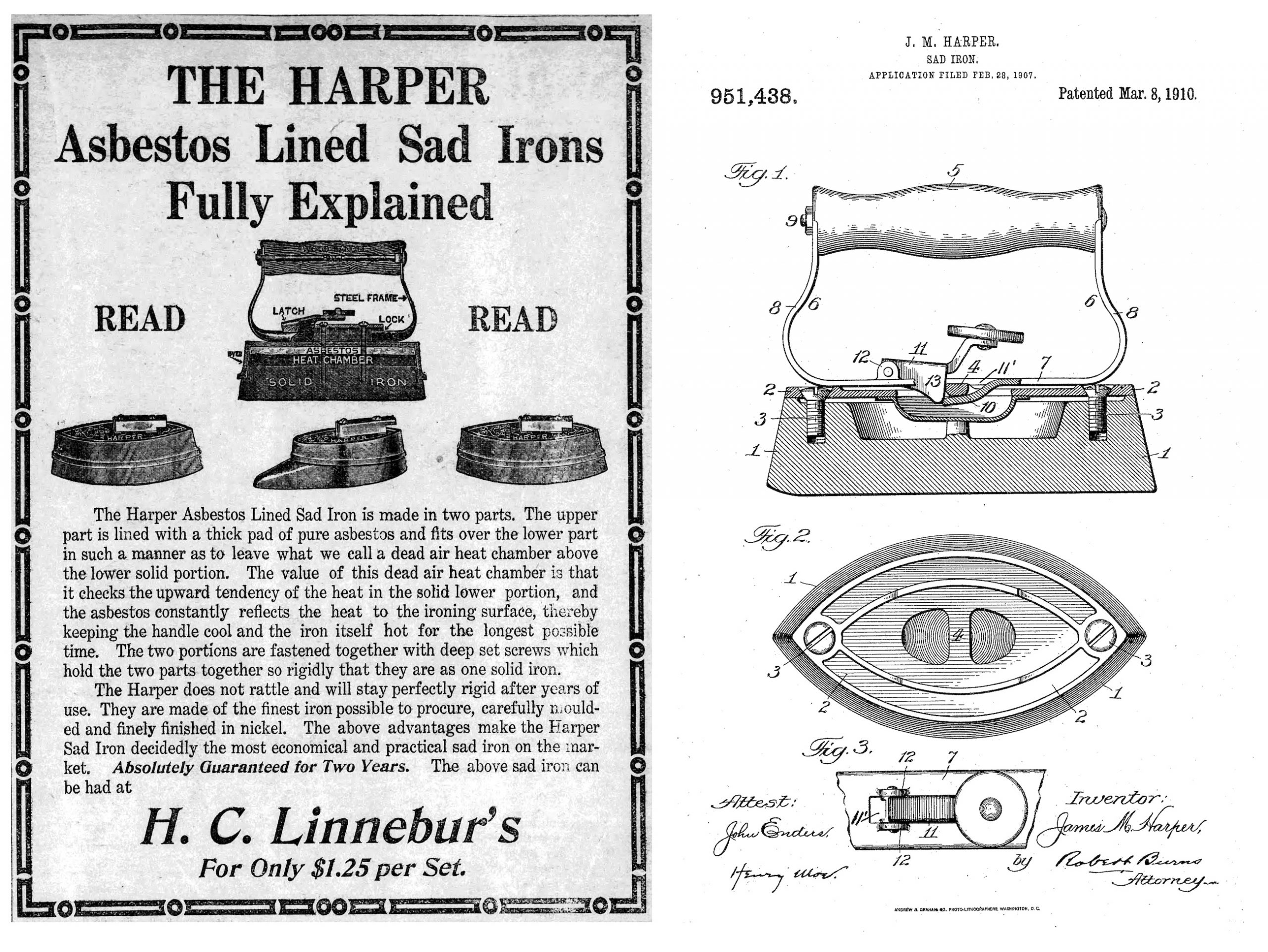

[J. M. Harper’s patented sad irons, seen here in a 1911 advertisement and a 1910 patent drawing, were successful sellers for years]

[J. M. Harper’s patented sad irons, seen here in a 1911 advertisement and a 1910 patent drawing, were successful sellers for years]

The Harper Supply Co. was already advertising for salesmen in 1897, before it had even been officially incorporated, and while we don’t know the full catalog of what they were selling, the casters were probably still a central focus. Harper’s original “sad irons” (heavy, flat cast-iron clothes irons) may have also been available, as several variations were patented shortly thereafter. It’s a safe assumption that the bulk of these goods were already being contracted out to a certain upstart foundry up the road in North Chicago.

It wasn’t until the turn of the century, though, that J. M. Harper started crafting his distinctive line of animal banks and safes, taking his brass molds in a more fanciful direction. He also developed and patented a nutcracker design, albeit not a dog-shaped one.

It wasn’t until the turn of the century, though, that J. M. Harper started crafting his distinctive line of animal banks and safes, taking his brass molds in a more fanciful direction. He also developed and patented a nutcracker design, albeit not a dog-shaped one.

Harper appears to have settled into retirement by the 1910s, and after his death in 1928, there’s no indication any element of his old business was retained.

SOURCES:

James M. Harper & The Chicago Hardware Foundry – Still Bank Collectors Club of America, 1985

“Residents Help Navy Chief Fight Nearby Saloons” – Chicago Tribune, April 25, 1915

“Executive Sued for Alienation of Wife’s Love” – Chicago Tribune, June 12, 1931

“Sullivan Company Manufactured Equipment For Diverse Businesses” – Patch.com, June 6, 2012

“Strike Pattern of 1938: Gas and Guns in Chicago” – Life magazine, Aug 1, 1938

“Suit Against Racine Plant is Settled” – The Journal Times (Racine, WI), Sept. 28, 1989

U.S. Patent 660033A – “Nut-Cracker,” Oct 10, 1900

“From Niles to Sager: The Story of the Chicago Hardware Company” – by Raymond J. Nemec, The

Doorknob Collector newsletter, No. 70, March-April 1995

“Harper Supply Company” – SafeBankCollector.com

“Puerto Ricans Flown to Chicago Work for 37c Weekly Take-Home Pay” – The Gazette and Daily (York, PA), Jan 2, 1947

“1 Dead as Fire and Blast Raze Industrial Park” – Chicago Tribune, June 2, 1988

“The Illinois Railway Museum at 50” by Frank Hicks, RYPN.org, 2003

I have a crucifix mad by them 19″ tall on pedistal

collect pigs would love to have one of those pigs

I have a hand dryer model 5f serial 44143 is this rare

Is one of the patterns that used to be on the bottom of the Chicago frying pan a diamond with a number in the middle of the diamond? Is there any other identifying markings on the Chicago cookware line?

I just acquired the ten sided spiderweb beehive lid chicken fryer. This supposed to be designed by Charles Tuteur in 1919 while he was chief designer at Chicago Hardware and Foundry Co. This is supposed to be an art deco design . I’ve read there was a matching dutch oven.

Looking for BOOK copy to verify this find.

Also reproduction cast iron sale catalog for Chicago Hardware and Foundry Co ,dates 1920’s

BTW I found the ten sided spiderweb beehive lid and bottom in the wild. Bought a tote full of cast and this pan and lid we’re in the bottom.

something another blind tree rat…..o well¡¡¡

Just acquired a chicago hardware &foundry Co. #5 Sana-Ware skillet.

Looking to find year of mfg.

Also value.

Also where might I find reproduction sales catalogs for ch&f co cast iron cookware.

Charles Tuteur worked as a sales manager for Chicago Hardware Foundry starting around 1919 and eventually became a partner in the Sani Product line. While working for CHF he also sold cast iron items under the Nuydea name. Is there any information that would show if CHF made the Nuydea products?

Sooner or later you and the others will have to visit a Library or two. I’ve seen a late 1930’s CHF Catalogue showing Favorite Ware. An earlier Catalogue based on Furniture will show NUYDEA.

Hi we just acquired a 4 inch tall 2 1/2 inch wide casted in bronze plaque/medallion of Abraham Lincoln my wife and I are wondering when this was produced and back of the plaque that is also looped for hanging says 1809 on top on the bottom it says CHI. HDW foundry, we would like to know when this was made meaning year? And what the value of this could possibly be? Thank you Wayne and Denise Kulesza Freeport Illinois

My uncle worked in north Chicago foundry. I have two German shepherd bookends, one all black, one brown with green base. Any idea worth of these two treasures,?

I have a mirror is got from a “free church day” and it appears to be very old. Only hint of where it is from is the three brackets, one had imprinted “bull dog lock com chicago pat pend” trying to date my mirror and believe the brackets pat pending date in the back will help me.

I have an iron three legged table with “Chicago HDW Foundry CO. – North Chicago, ILL. PATD June 20 1918” on the inside ring. I would like to see original image in catalog so that I can restore the top and know value. Its approximately 34” tall and 22” diameter.

I am wondering if either companies produced bust profile sculptures. I have a pair of bronze/brass Pres. Lincoln and VP. Hannibal Hamlin that came from an estate in chicago , il. Would love to know the history on these pieces.

Thank you.

We have a black dog nut cracker with a red tray and the words Pat Apld For on the bottom of the tray. This has been in our family for decades. In what year was this particular piece made?

I have a waffle iron base that is marked only with a C H. I think it is a Chicago Hardware foundry piece. I can’t find very much information on this company and it’s markings. Does that sound right to you?

I found a # 5 Chicago Hardware Foundry No. Chicago pan in Fle Market. It was total rust and caked on carbon. I’ve restored and seasoned it. Now back to life and ready for another 100 years. I’m just getting educated in this company. Do you have any suggestion as to worth? The pan is not marked as to size, but measures the same as a Griswold # 5. Markings are. CHICAGO HDWE. FDRY CO.

FAVORITE

COOK

WARE

NO. CHICAGO L’LL

Mr. Finlayson,

Congratulations on your discovery. Depending on its condition and your restoration process, your No. 5 CHF Favorite Cookware could be worth between $30 and $50 at auction. That size is one of the more common found outside of collector hoards and they appear from time to time on ebay and other virtual flea markets.

I have a Chicago Hardware Foundry #87F frying pan, would you know when this was made?

Also, what size is it?