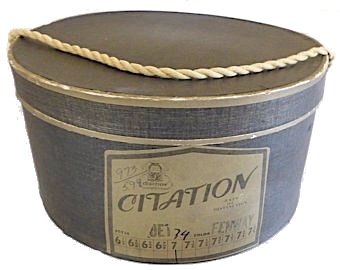

Museum Artifacts: Citation Beaver Quality Fedora, c. 1950s, and Mid City Khaki Garrison Cap, 1948

Made By: Citation Hat Corp. / Mid City Uniform Cap Company, 2330 W. Cermak Rd., Chicago, IL [Lower West Side]

“I hate like hell to praise myself, but at the same time I cannot go away from the truth.” —Harry Lev

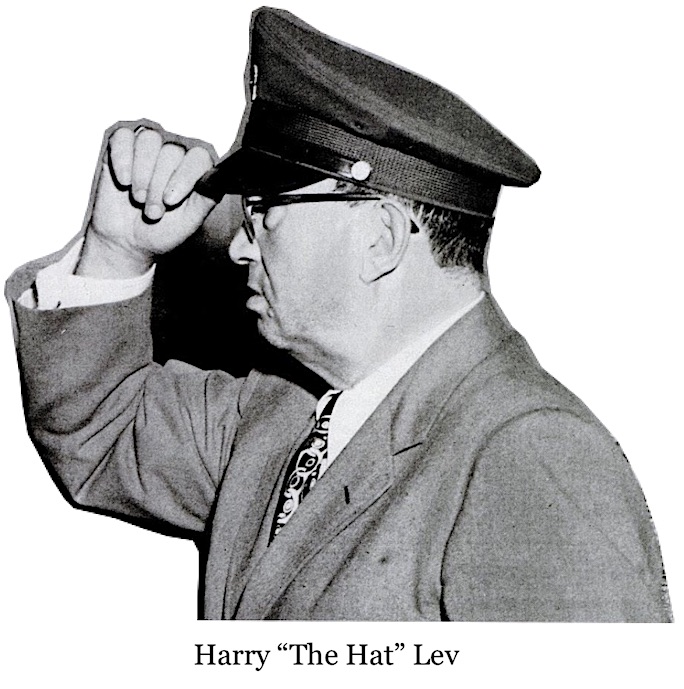

In the summer of 1955, Harry “The Hat” Lev—53 year-old owner of the Citation Hat Company, Mid City Uniform Cap Co., and about a dozen other headwear businesses—was called to testify before the U. S. Senate’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. This was just a year after the Army-McCarthy Hearings had been held before the same committee; when a hot seat was still a hot seat. And yet, Harry the Hat had a certain way of keeping his cool.

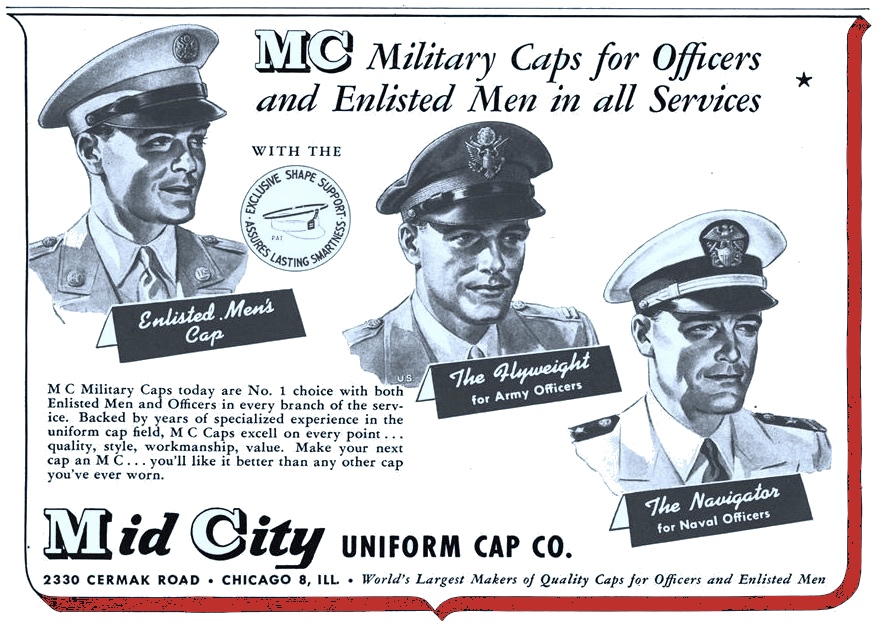

Though he was based out of Chicago and supposedly couldn’t write more than his own name in English, the Polish-born Lev was no stranger to interactions with government officials in Washington. He’d been supplying caps and other apparel to the U.S. Military under the Mid City / “MC” name since before World War II—negotiating contracts year after year to design and produce everything from officers’ visor hats to the “envelope” style of cotton khaki garrison hat seen in our museum collection (a model in prime use during the Korean War). Along the way, Lev’s charismatic sales pitches and fresh-off-the-boat faux-naivety had made him something of a minor comedic celebrity at the cocktail parties and gambling halls where such deals were made.

Though he was based out of Chicago and supposedly couldn’t write more than his own name in English, the Polish-born Lev was no stranger to interactions with government officials in Washington. He’d been supplying caps and other apparel to the U.S. Military under the Mid City / “MC” name since before World War II—negotiating contracts year after year to design and produce everything from officers’ visor hats to the “envelope” style of cotton khaki garrison hat seen in our museum collection (a model in prime use during the Korean War). Along the way, Lev’s charismatic sales pitches and fresh-off-the-boat faux-naivety had made him something of a minor comedic celebrity at the cocktail parties and gambling halls where such deals were made.

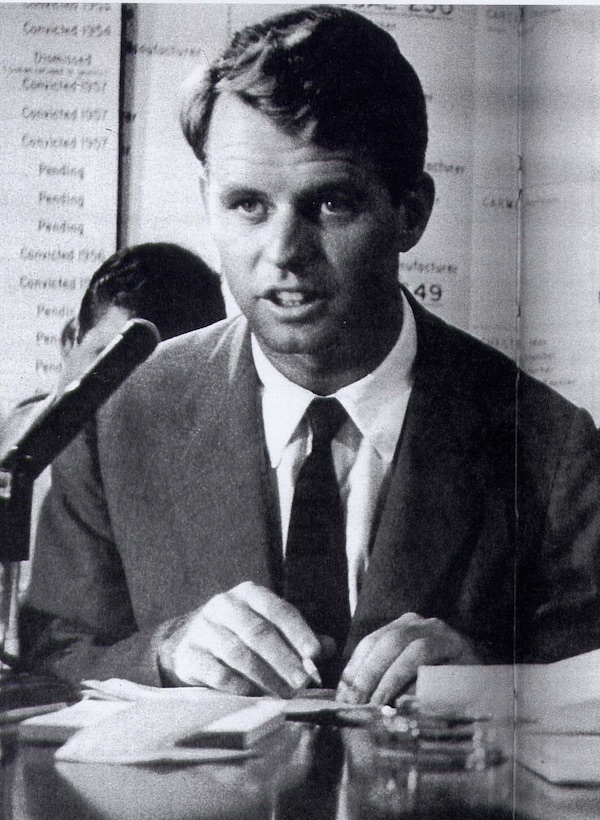

So why then, after years of seemingly admirable service to the country, was Harry Lev now defending himself against a barrage of questions and accusations from the likes of Robert F. Kennedy? Well, to put it simply, the government was more than happy to save a buck outfitting its brave soldiers with shoddy hats, but when that shoddy hat supplier started exploiting the government in a similar fashion, the buck—as they say—had to stop there.

[1945 Ad for Mid City’s MC Military Caps. “World’s Largest Makers of Quality Caps for Officers and Enlisted Men”]

[1945 Ad for Mid City’s MC Military Caps. “World’s Largest Makers of Quality Caps for Officers and Enlisted Men”]

The Meaning of a “Millionaire”

According to reports from the 1955 hearings, Harry Lev and the Mid City Uniform Cap Company had routinely fallen woefully short of meeting their contractual obligations, with one oft-cited example finding them about 500,000 shy of a promised number of khaki garrison caps. You might presume that colossal level of failure would be mighty difficult to miss, but the oversight was blamed on a wider criminal conspiracy, with Lev supposedly paying off Defense Department officials to look the other way while he pocketed the difference. Similar patterns emerged with cap orders that had been contracted out to Lev’s satellite factory in Puerto Rico—a shady operation if there ever was one.

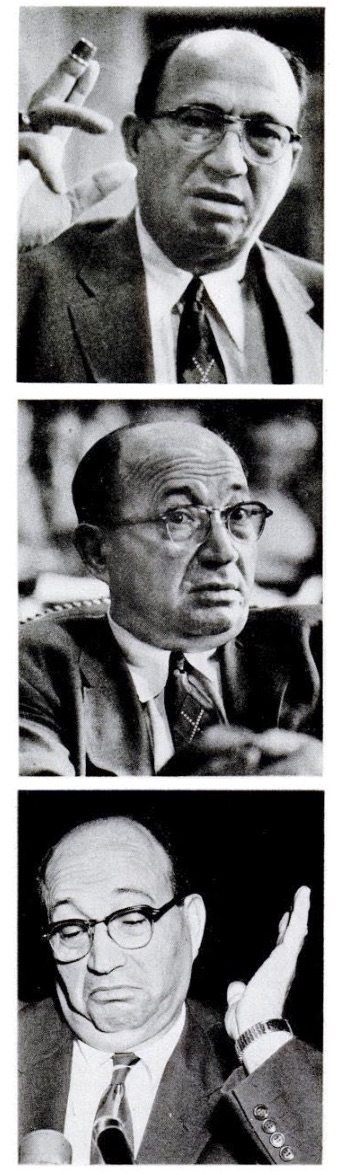

Ultimately, the hammer came down on Harry, as a 1957 criminal trial landed him a nine-month prison sentence for defrauding the government. It was Lev’s unique “performance” before the sub-committee in ‘55, however, that generated more headlines. His hours-long testimony was widely viewed as a circus of embarrassment for all involved, as Senator Kennedy and other questioners tried to get the eccentric Chicago businessman to cop to an alleged history of bribery, blackmail, and hush payments.

[Harry Lev testifies before the Senate Subcommittee on Investigations, 1955. While his hat factory was located in Chicago Lowest West Wide, Lev and his wife lived on the North Side, at 6107 N. Kenmore Ave. in Edgewater.]

[Harry Lev testifies before the Senate Subcommittee on Investigations, 1955. While his hat factory was located in Chicago Lowest West Wide, Lev and his wife lived on the North Side, at 6107 N. Kenmore Ave. in Edgewater.]

Lev’s strategy as a witness, it seems, was to lean on the folksy salesman charm that had always worked for him in the past. Upon entering the hearing room, for example, he proudly donned one of his own military caps and scurried about “handing out business cards to senators, reporters, and spectators,” according to Life magazine. He was a “broad-shouldered man with a red face, a breast pocket full of cigars and a wardrobe that includes 1,000 neckties.” He was also, by any measure, a millionaire. Although—in a ludicrous exchange quite representative of the entire three days of questioning—he wasn’t willing to directly acknowledge that fact, or much else, under oath.

Senator George Bender: Mr. Lev, I understand you are a millionaire. You have many other interests in addition to manufacturing caps?

Lev: I don’t know anything about being a millionaire.

Bender: You are a very rich man.

Bender: You are a very rich man.

Lev: I wouldn’t say. It all depends.

Bender: What do you mean, it all depends? How does it depend?

Lev: It all depends on what you think a millionaire is.

Bender: What do you think a millionaire is?

Lev: I don’t know what it is. The only thing I know is that I have been spending all my life since I was a kid of fourteen and a half years, I started up with my father—

Bender: We know about your life.

Lev: Oh, you do?

Bender: Yes. You are a successful self-made man.

Lev: Thank you.

Bender: And you are a big-business man.

Lev: Alright, thank you. Thanks for the compliment.

Bender: You are a millionaire?

Lev: It all depends on what you mean by a millionaire, Senator.

Bender: A millionaire is a man who is very rich.

Lev: Well, I wouldn’t say that. Maybe there are some other outside sources may think I am a millionaire, but as far as I am concerned, I am a man, just as good as the average.

Bender: I am not questioning your manhood. I do not question your veracity or anything else. I say you are a very rich man.

Lev: Alright, but I am not a millionaire as far as character is concerned.

Bender: We will take that for granted. That is your comment. We are not making that comment. I mean, as far as money is concerned, you ARE a millionaire?

Lev: Money is not everything to me. Accomplishment, Senator, is more than money.

In contrast to—or maybe as evidence of—the business savvy that had earned him all that money, Lev relied heavily on his struggles with the English language to get him out of a pinch. After 30 years running a business in Chicago, it’s likely he both spoke and wrote the language better than he let on. But it wasn’t in his interests to make that obvious.

This technique proved remarkably effective in spinning the heads of well seasoned senators, including young RFK, who found himself in the incredibly bizarre position of questioning Lev about one of the hatman’s preferred methods of bribery: smoked sturgeon.

Kennedy: Can you name any other gifts besides caps that you gave to anybody working for the Government?

Kennedy: Can you name any other gifts besides caps that you gave to anybody working for the Government?

Lev: Maybe a hat once in a while.

Kennedy: Beyond hats, what did you give them?

Lev: Fish.

Kennedy: Fish? What kind of fish?

Lev: Sturgeon.

Kennedy: Smoked sturgeon?

Lev: Yes, Sir.

Kennedy: In smoked sturgeon alone, you spent $2,609.10 between January 1952 and April 1955, as gifts?

Lev: I wouldn’t call it a gift.

Chairman: What do you call it?

Lev: Believe me, they have never asked for it.

Chairman: They have not asked for it; you just gratuitously gave it, but what do you call it if it is not a gift?

Lev: A gift is something—I think that is something that a person wears.

Chairman: Something that a person wears?

Lev: Anything else except what he wears is not a gift. In my mind. I might be wrong.

It may be unsurprising to learn that Harry Lev was not among Bobby Kennedy’s favorite witnesses. According to the 1967 book, RFK: The Man Who Would Be President, after a day of trying to pin down Lev, Kennedy supposedly “dissolved in despair . . . moaning, ‘For crying out loud!’”

Senator George Bender of Ohio, who took the brunt of Lev’s nonsense, was less able to keep his own anguish behind closed doors.

“You evade!” he eventually shouted at Lev during the hearing. “You hesitate! You delay! You procrastinate! You can equivocate! You can repeat questions! You can fix! You can do everything except give a direct answer! You’re a very clever man!”

“You think so?” Lev responded, deftly walking the line between oblivious appreciation and super villainy.

[The Mid City Uniform garrison gap from our museum collection, discovered in Leeds, UK, dates from 1948]

[The Mid City Uniform garrison gap from our museum collection, discovered in Leeds, UK, dates from 1948]

Re-Sizing the Cap

Harry Lev’s bizarre antics and eventual conviction have largely proven to be the lasting historical footnotes for the Citation Hat Company and Mid City Uniform Cap Co. But it’s quite likely that, in the process, we’ve unfairly dismissed what was once a pretty legitimate and long-running Chicago hatmaking empire.

For nearly 20 years (deservedly or not), Mid City did play an important role in outfitting American servicemen and women during some of the pivotal engagements in U.S. Military history. And on the homefront, Citation had a good reputation in its heyday as a reliable budget fedora brand in the Midwest. Both companies also carried on for another two decades even after Lev’s conviction (albeit mostly under the capable leadership of new president George H. Simon).

Few American hat factories were more prolific in the mid-century, and yet, whether among militaria enthusiasts or hat collectors clubs, virtually nothing has been written about these companies from a modern perspective; excluding the occasional residual mythology left over from Harry Lev’s infamous song-and-dance.

Few American hat factories were more prolific in the mid-century, and yet, whether among militaria enthusiasts or hat collectors clubs, virtually nothing has been written about these companies from a modern perspective; excluding the occasional residual mythology left over from Harry Lev’s infamous song-and-dance.

In 2008, for example, Forbes columnist James Brady summarized the Harry the Hat tale with plenty of gusto, but minimal fact checking:

“In the 1950s, one of everyone’s favorite procurement crooks was Harry “The Hat” Lev,” he wrote. “[Lev] supplied headgear that didn’t work to men fighting in somewhat chilly North Korea. Harry had no hats, no office and no plant, and did business with the Pentagon from the garment district in New York, using sidewalk pay phones to bid on contracts, underbidding genuine hat makers, then subcontracting the job to someone else and pocketing the dough. Harry’s hats leaked, fell apart and didn’t fit. But having bribed Defense Department procurement officers and put their kids through college, Harry the Hat made a fortune.”

It’s nothing new to erroneously transport Chicago history to New York, but the bigger error here is to say that Harry Lev “had no hats.” Harry had A LOT of hats, and a genuine skill set for making and designing them. By the mid ‘50s, he had close to 30 hat-related patents to his credit, and his experience in the field tracked all the way back to his childhood. It’s an origin story with plenty of missing details, but at the very least, it helps paint Harry Lev as a slightly more sympathetic character than his later antics would suggest.

[Left: A Harry Lev hat patent from 1952. Right: A 1950s Citation hat from our museum collection.]

[Left: A Harry Lev hat patent from 1952. Right: A 1950s Citation hat from our museum collection.]

“Hats of Distinction”

Born in the city of Pinsk in Russian-controlled Poland in 1902, Harry Lev left school by 12, and began learning the hatmaking trade from his father. Being Jewish, his family was forced to flee after the Bolshevik Revolution, eventually landing in Palestine, where Harry established himself as a proper hatmaker in his own right. Finally, in 1923, at age 21, he left for America, landing a job in a Chicago factory.

While the chronology is unclear, Lev eventually went into business with his brother-in-law and fellow Jewish immigrant Max Spector (1892-1980), opening a small plant with just $500 in capital (if you believe Lev’s re-telling) and making uniform caps for policeman, firemen, postmen, etc. In Lev’s 1955 testimony, he claims to have “taken in” Spector as a partner despite Spector having “no experience.” But, in truth, census records show that Spector had worked as a tailor for the clothing giant Hart, Schaffner & Marx, and as such, probably brought as much to the table as Harry did.

While the chronology is unclear, Lev eventually went into business with his brother-in-law and fellow Jewish immigrant Max Spector (1892-1980), opening a small plant with just $500 in capital (if you believe Lev’s re-telling) and making uniform caps for policeman, firemen, postmen, etc. In Lev’s 1955 testimony, he claims to have “taken in” Spector as a partner despite Spector having “no experience.” But, in truth, census records show that Spector had worked as a tailor for the clothing giant Hart, Schaffner & Marx, and as such, probably brought as much to the table as Harry did.

In Spector’s own 1980 obituary, the Tribune identifies him as the “founder and president” of the General Shirt Co. and the Mid City Uniform & Cap Co., dating both companies’ roots back to 1922. Other sources seem to suggest it was 1925. Either way, it’s safe to say that Lev was there nearly from the beginning, and that he and Spector remained leading partners in the enterprise up until 1944, when Lev temporarily broke off to focus on the General Shirt Company.

By that point, Mid City had already established itself as a major cap supplier to the Armed Forces, starting with its first contract back in 1937 (when Depression era shortages likely had the military looking for bargains). The expansive, four-story Mid City factory at 2330 W. Cermak Rd. also appears to have opened shortly beforehand, giving Lev and Spector some legit proof of their ability to produce hats en masse.

[The Citation / Mid City Uniform Cap Co. factory at 2330 W. Cermak Rd., 1950s. This building was torn down in either the ’90s or 2000s.]

After Pearl Harbor and on through the Korean War, Mid City continued to supply thousands of caps to America’s enlisted men and women, as well as soldiers from other allied nations. It was likely the runaway profits from these contracts that enabled Lev to launch the Citation Hat Company after WWII as a new wing for the civilian market.

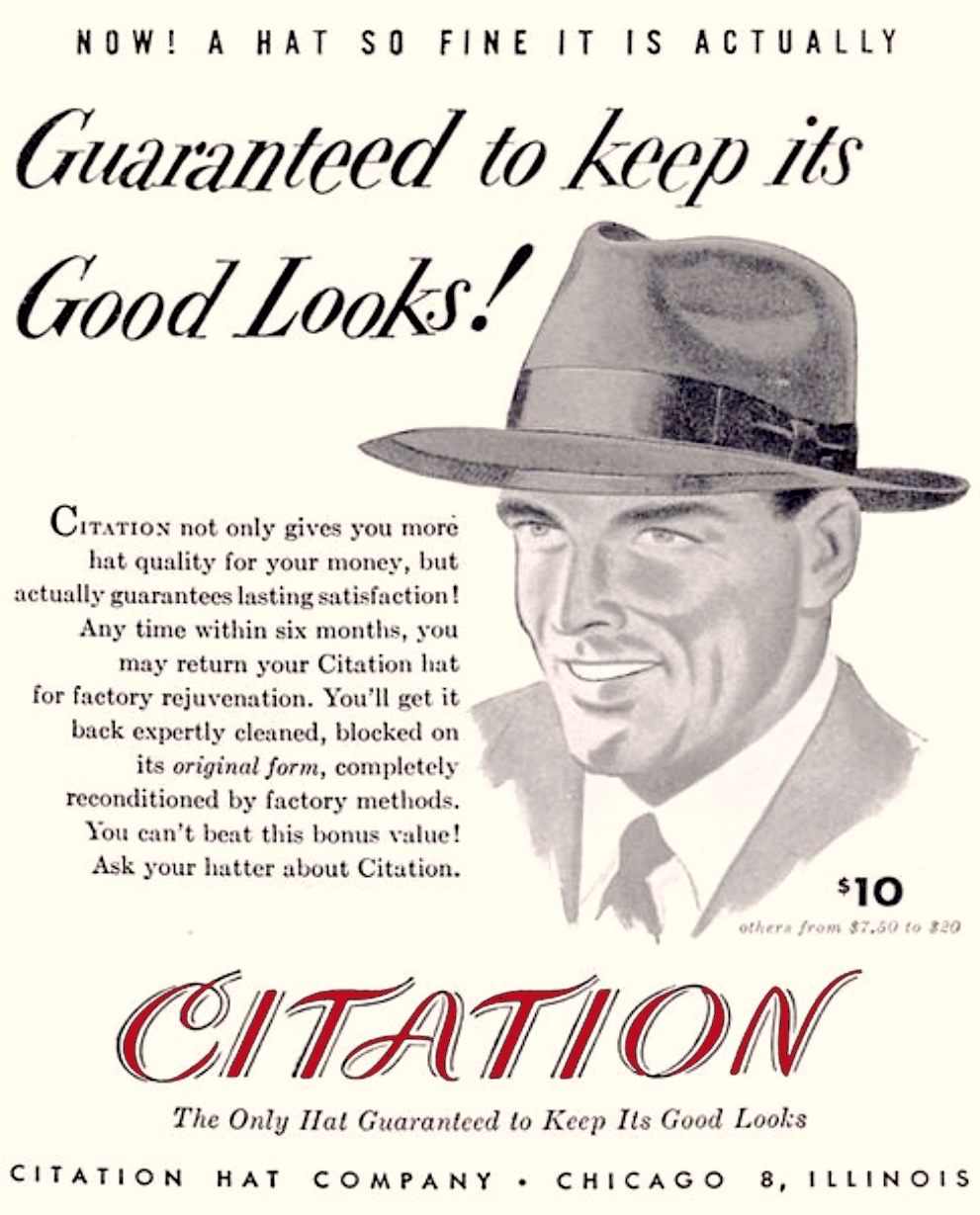

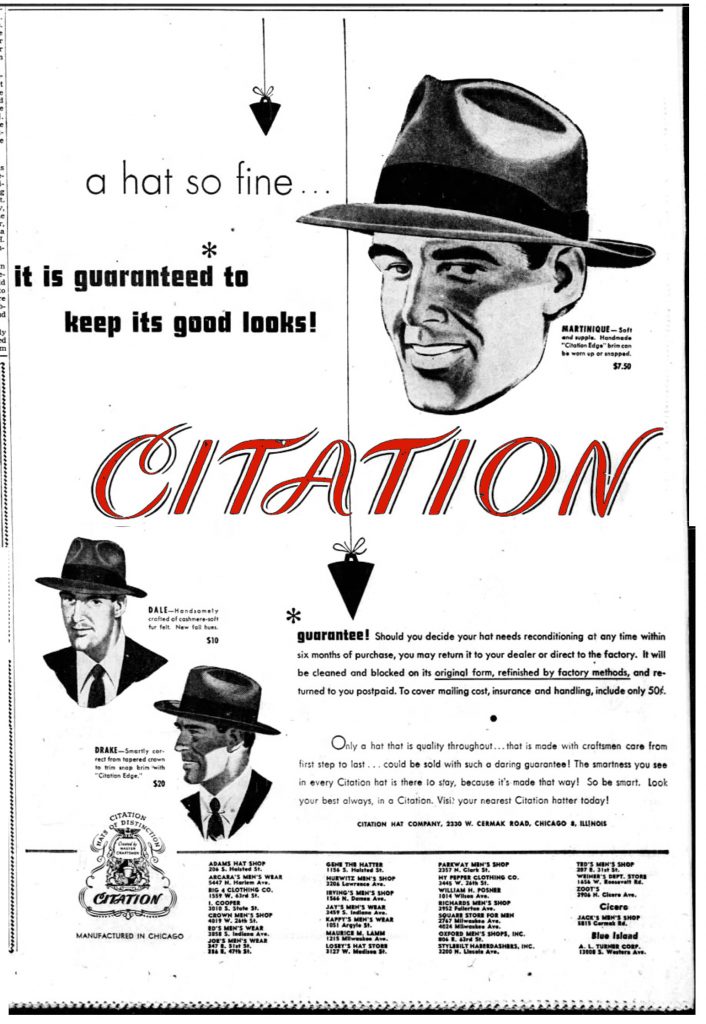

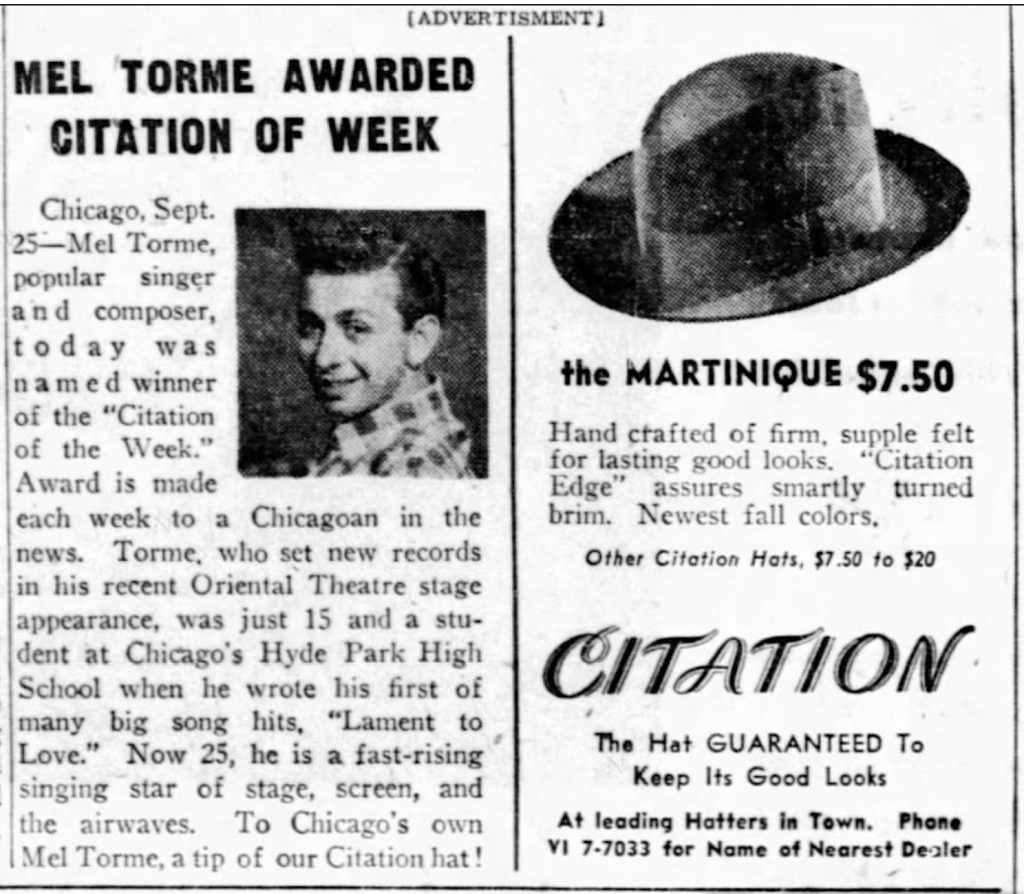

Citation and its “Hats of Distinction” catered mostly to 1950s businessmen, and specialized in the types of felt fedoras that were basically a requirement of the time period (the beaver fur hat in our museum collection is a typical example). These hats were distributed through dozens of local clothing and hat shops, eventually expanding into more of the Midwest. At the company’s early ’50s peak, it also had a showroom inside Room 840 of the Merchandise Mart.

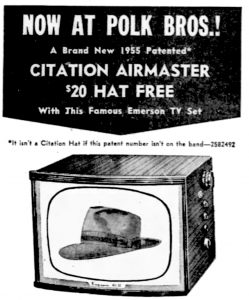

“A hat so fine . . . it is guaranteed to keep its good looks,” read a 1950 ad for Citation fedoras, which included the “Dale,” “Drake,” “Chief,” “Eagle,” and “Martinique” styles. If for some reason a hat did need reconditioning within the first six months of purchase, the company welcomed customers to return it direct to the Chicago factory, where it would be “cleaned and blocked on its original form, refinished by factory methods, and returned to you postpaid.

“A hat so fine . . . it is guaranteed to keep its good looks,” read a 1950 ad for Citation fedoras, which included the “Dale,” “Drake,” “Chief,” “Eagle,” and “Martinique” styles. If for some reason a hat did need reconditioning within the first six months of purchase, the company welcomed customers to return it direct to the Chicago factory, where it would be “cleaned and blocked on its original form, refinished by factory methods, and returned to you postpaid.

“Only a hat that is quality throughout . . . that is made with craftsmen care from first step to last . . . could be sold with such a daring guarantee! The smartness you see in every Citation hat is there to stay, because it’s made that way! So be smart. Look your best always, in a Citation. Visit your nearest Citation hatter today!”

Citation Hats were produced in the same four-story West Side factory as the military, industrial, and marching band models made by the Mid City Uniform Cap Co. The plant employed dozens of skilled men and women, and for a moment in time, looked like a perfect exhibition of what an immigrant with a dream could achieve.

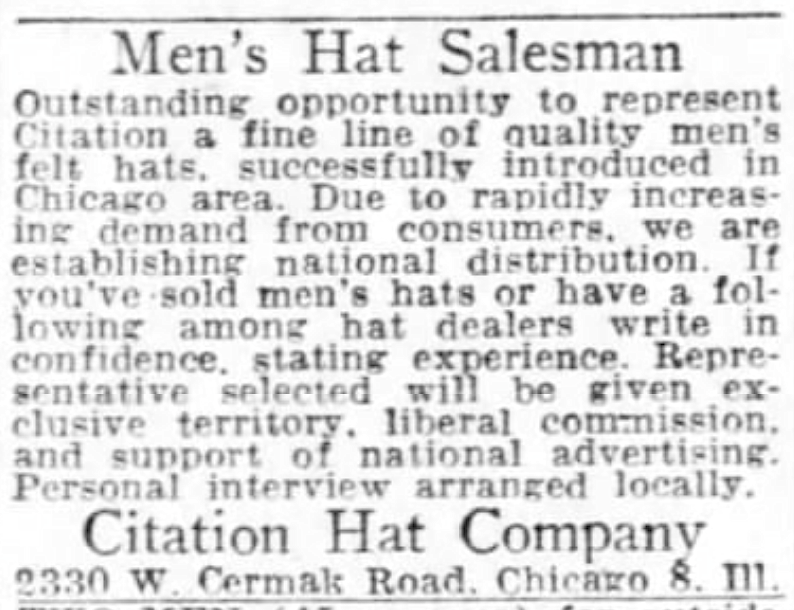

[At the time of the 1950 Citation advertisement above, the company was selling its hats almost entirely through local Chicagoland shops, including Adam’s Hat Shop and Gene the Hatter (both on S. Halsted), Kappy’s Men’s Wear in Uptown, Losby’s Hat Store on West Madison, and Zoot’s on North Cicero. Within a few years, they started expanding to more of the Midwest, placing ads for salesman like the one here from the Detroit Free Press in 1951.]

[At the time of the 1950 Citation advertisement above, the company was selling its hats almost entirely through local Chicagoland shops, including Adam’s Hat Shop and Gene the Hatter (both on S. Halsted), Kappy’s Men’s Wear in Uptown, Losby’s Hat Store on West Madison, and Zoot’s on North Cicero. Within a few years, they started expanding to more of the Midwest, placing ads for salesman like the one here from the Detroit Free Press in 1951.]

A Hat-Free Society

There is little information as to what became of Harry Lev between his 1957 conviction and his death in 1964. He had actually sold the majority stock ownership of Mid City to his wife Betty back in 1953 (likely in anticipation of his own potential downfall), and at some point, brother-in-law Max Spector re-entered the scene, serving a managing role up until his own retirement in 1965. Harry Lev’s obituary mentions his wife, four children, and six grandkids, but nothing about his career. It’s unclear how much of his wealth was retained or whether any of his children dabbled in the cap trade.

Meanwhile, as a pretty effective way of repairing the Citation Hat Company’s reputation, a World War II veteran named George R. Simon was brought on as the new company president. A former Navy man, Simon had likely worn one of Harry Lev’s questionable caps during his service. Now, he sat in Lev’s old office.

Unfortunately, the early 1960s was not a great time to be getting into the civilian hat business. For the first time in generations, businessmen were starting to go hatless—a trend ironically often attributed to the Kennedy brothers (revenge at last!).

Unfortunately, the early 1960s was not a great time to be getting into the civilian hat business. For the first time in generations, businessmen were starting to go hatless—a trend ironically often attributed to the Kennedy brothers (revenge at last!).

George Simon had considerable political aspirations of his own. He was associated with the U.S. State Department on Foreign Relations, and was the National Treasurer for Danny Thomas’s St. Jude Research Hospital. In 1962—while serving as Citation’s president—he ran for a state senate seat, hoping to represent Du Page and Will counties as a Democrat (he was soundly defeated).

A decade later, Simon was still the headman at Citation, reporting daily to his office in the aging Cermak Road factory. With America’s demand for hats thoroughly bottoming out in the 1970s, however, it was an increasingly bleak outlook.

“He held on as long as he could with the factory,” recalls Simon’s grandson, Nikolas Simon. “I remember in the early seventies going there as a kid and running around the factory, but at that point, it was somewhat of a graveyard. He just had his office there. . . . I recall the factory shutting down for good around 1977.”

On a more pleasant front, Nikolas notes that his grandfather “was very involved with Danny Thomas and the grand opening of St Jude’s Research Hospital. He was quite a philanthropist, as were his two brothers.”

Citation’s quiet demise hardly generated any attention in the late ‘70s, when closing Chicago factories were too common to be noteworthy. The old Cermark plant was adapted into a market for a while in the ‘80s and ‘90s, but has since been leveled.

Citation’s quiet demise hardly generated any attention in the late ‘70s, when closing Chicago factories were too common to be noteworthy. The old Cermark plant was adapted into a market for a while in the ‘80s and ‘90s, but has since been leveled.

Meanwhile, the old hat inventory lives on—from vintage clothing shops in Chicago, where old Citation “Hats of Distinction” boxes are still routine finds, to places as far away as Leeds, England, where the garrison cap in our collection was found. The thousands of military caps made in the Cermak factory, bearing the Mid City name, were naturally carried to the four corners of the Earth. And while they might be a bit notorious to those who know the history, they’re also artifacts from a pretty remarkable story. Harry “The Hat” Lev—whether he was an inspirational refugee, a brilliant businessman, or just a ridiculous huckster—helped define the look of America’s “Greatest Generation” in the ‘40s and ‘50s. And his demise, in a roundabout way, marked the end of the last golden age for men’s hats in general.

Sources:

Hearings Before the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Government Operations, United States Senate, 84th Congress, 1955

“Meet the Man Just Out of Average” – Life Magazine, July 25, 1955

“Mel Torme Awarded Citation of Week” – Chicago Tribune, Sept 25, 1950

Max Spector Obit – Chicago Tribune, June 5, 1980

“Scandal Time” – Forbes, April 10, 2008

An American in Washington, by Russell Baker, 1961

R.F.K.: The Man Who Would Be President, by Ralph Toledano, 1967

“George R. Simon for State Senator” – Political Flyer, 1962

I have an enlisted man’s cap. The brim has come apart from the cap. Do you know of anyone who does repairs to these caps? It belonged to my Dad and my purpose is to preserve it for future generations. Thank you for any help you can provide.

Hello. I have what looks to be a US Army hat that has a patent of Dec 1950 from Mid City Uniform Cap Co. It has the name “Voss” and two identification codes – US 55543785 as well as V3785. The first is written on the tag, and the second professionally stained inside the brim.

Question is in your research do you know of these codes and how to identify owner or next of kin?

All the best, Kevin Dineen

I remember my uncle Harry he was a great guy

He would always take my brother and I to buy fried shrimp and stergeon. He was a very generous man. My uncle Ben worked for

Uncle Harry as his mechanic And he invented many things and got them patients

The best pattern was called the metal stay

That clipped inside of the hat kept the cap erect

Thank You so much for writing this article and including my Grandfater. I had forgotten about our communication some years ago. My family is grateful that you acknowledged our Grandfather. Very nice writing of the entire article.