Museum Artifact: Kist Beverages Soda Bottle, c. 1940s

Made By: Citrus Products Co., 11 E. Hubbard St., Chicago, IL [Downtown / The Loop]

Most Notable Factoid: In 1933, the vice president of Citrus Products fired a gun at his own wife (and missed) after he saw her kissing the president of the company at a party.

Best known for its “Kist” brand of carbonated beverages, Chicago’s Citrus Products Company was in operation from 1919 to 1965, concocting the fruit flavorings for a vast network of independent distributors to mix in, bottle up, and ship out. The business—which also produced the obscure chocolate-milkish drinks “Brownie” and “Chocolate Soldier”—was ultimately purchased and absorbed by Atlanta’s Monarch Food Packers Inc., which then sold all its rights over to the Texas-based Leading Edge Brands in 1997. By 2009, the greatly diminished line of Kist Beverages had come under the ownership of Detroit’s Intrastate Distributors, Inc., and as far as we can tell, the brand is now (unofficially) extinct after a century in circulation.

Best known for its “Kist” brand of carbonated beverages, Chicago’s Citrus Products Company was in operation from 1919 to 1965, concocting the fruit flavorings for a vast network of independent distributors to mix in, bottle up, and ship out. The business—which also produced the obscure chocolate-milkish drinks “Brownie” and “Chocolate Soldier”—was ultimately purchased and absorbed by Atlanta’s Monarch Food Packers Inc., which then sold all its rights over to the Texas-based Leading Edge Brands in 1997. By 2009, the greatly diminished line of Kist Beverages had come under the ownership of Detroit’s Intrastate Distributors, Inc., and as far as we can tell, the brand is now (unofficially) extinct after a century in circulation.

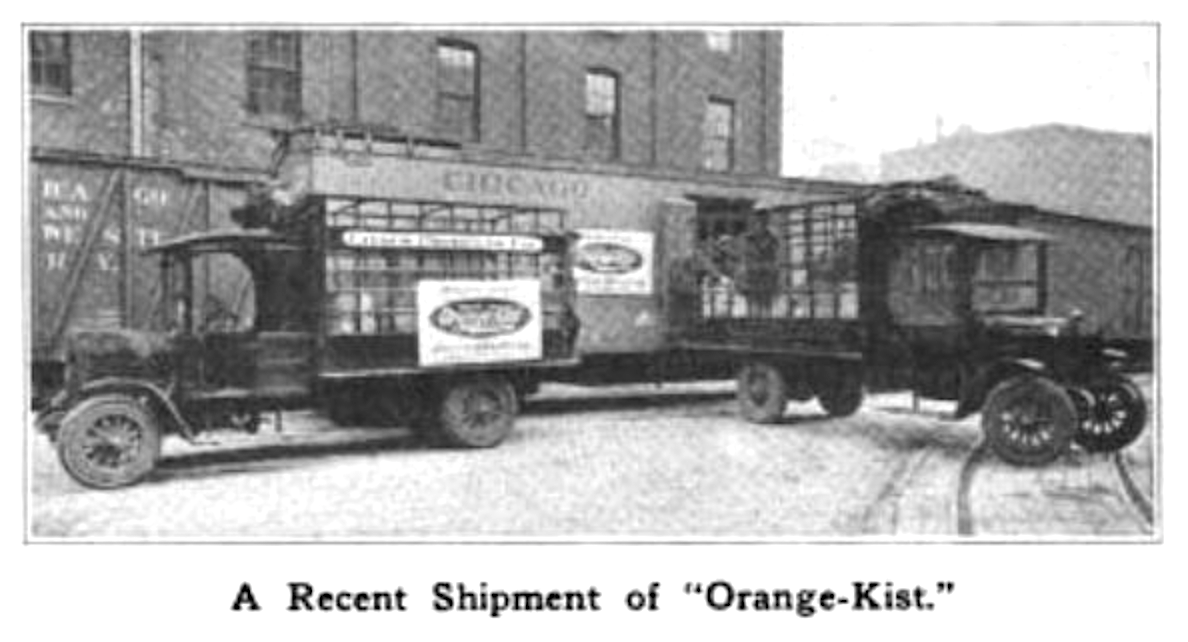

In terms of its place in the illustrious history of American fruit sodas, the original “Orange Kist” followed hot on the heels of another famous Chicago contribution, “Orange Crush,” which was developed in 1916 and sold by the aptly named Orange-Crush Company (314 W. Superior Street). In fact, Kist basically aped everything Crush was doing, even stealing away their head of advertising in 1922 as the Prohibition cola wars heated up.

Meanwhile, despite appearances, Kist never had any direct affiliation with today’s #1 selling orange pop brand—Sunkist—which didn’t arrive on shelves until 1979. There is certainly a loose thread connecting the two, however, as California’s Fruit Growers Supply Co-Operative was using the “Sunkist” trademark to promote its produce as early as 1909, thus likely inspiring our friends at the Citrus Products Company to co-opt and abbreviate the concept a decade later for their new fruit-flavored soft drinks.

The vintage Kist bottle in our museum collection likely dates from the 1940s (the stamp on the bottom suggests ’42), and has a classic Art Deco style to match. Even during the war years, crates of Kist were moving through franchised bottling plants in every state, as well as (pre-statehood) Hawaii, where sailors at Pearl Harbor could get their supply re-stocked by the Honolulu Sodawater Co., Ltd. One bottle would set you back a nickel.

Back in Chicago, the Citrus Products Company of the 1940s was putting a lot of its resources into laboratory research. The plant at 11 E. Hubbard Street had a team of chemists working on new “flavoring extracts and concentrates for carbonated beverages and ice cream; the testing of various gums used in emulsions; the development of new combinations of flavors, and the testing of inhibitors” (Industrial Research Laboratories of the United States, 7th ed., 1940). The company president at the time, Albert C. King, wasn’t involved in any of that work; he had already half-retired to Pasadena, California. The story of how King ascended to his position, however, is the stuff of scandalous tabloid legend. And it all started, ironically enough, with a Kist. Or, rather, a kiss.

History of Citrus Products Co., Part 1: Prelude to a Kist

Trying to sum up the manufacturing history of any single soft drink or food stuff is always a unique challenge, since the story is usually that of dozens or even hundreds of small regional distributors all doing their own small part in helping the product succeed. With Kist, the Citrus Products Company wasn’t so much the “maker” of a soda as they were the owners of its formula, and perhaps more importantly, the masters of its marketing.

The business was organized in 1919 with $100,000 in capital stock, and its first office was located at 350 N. Clark Street. It’s not entirely clear who was the true founder or driving force at the beginning, but the supposed inventor and licensor of the “Orange Kist” concentrate—the company’s first key product—was Arthur E. Fest, a salesman who would go on to a long career as a candy industry executive with numerous firms. The Orange Kist trademark, meanwhile, was officially licensed to the Citrus Products Co. by a wholly different person, Margaret B. McCarthy, in 1922.

The business was organized in 1919 with $100,000 in capital stock, and its first office was located at 350 N. Clark Street. It’s not entirely clear who was the true founder or driving force at the beginning, but the supposed inventor and licensor of the “Orange Kist” concentrate—the company’s first key product—was Arthur E. Fest, a salesman who would go on to a long career as a candy industry executive with numerous firms. The Orange Kist trademark, meanwhile, was officially licensed to the Citrus Products Co. by a wholly different person, Margaret B. McCarthy, in 1922.

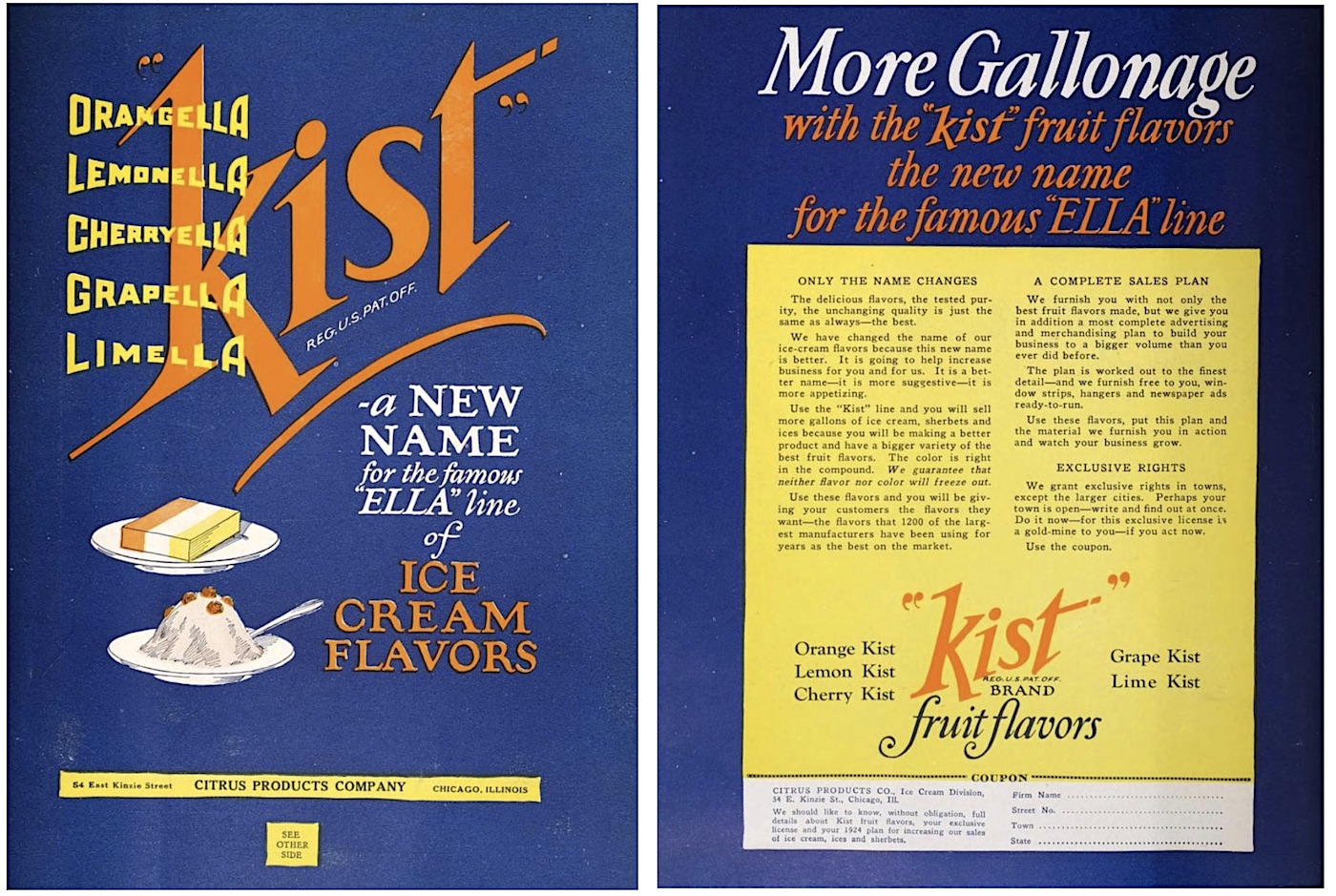

That same year, with the business now based at 54 E. Kinzie Street, the two most important ambassadors of the Kist brand joined the fold, with sales specialist C. H. Davies signing on as secretary and Eric G. Scudder—a 35 year-old advertising man poached from the Orange Crush team—taking over the presidency (replacing Daniel G. Moore). Boosted by additional financial backing from local cheese producer James L. Kraft (yes, that Kraft), Scudder quickly consolidated the brand identity of Citrus Products’ two divisions—soda and ice cream—under the single banner of KIST. This spelled the end for the company’s short lived “Ella” line of ice creams, as Lemonella, Orangella, Cherryella, Grapella, and Limella all just became the frozen flavors of KIST.

With all their eggs now in the Kist basket, Scudder and Davies aggressively toured the country throughout the early-to-mid 1920s, encouraging new franchisees to hop aboard the flavor train and embrace a new drink for dry times. Unlike some competitors, however, they never emphasized the prohibition of booze as an automatic victory for the soda industry. Instead, using the tactics that had already worked with Orange Crush, they pointed to the increasingly crowded field of non-alcoholic thirst quenchers, and the vital importance of building name recognition through aggressive marketing at all stages of distribution. Whatever it took to stand out.

“Many bottlers are inclined to be pessimistic and doubtful about the future,” C. H. Davies told the Beverage Journal in 1922. “We, however, are confident that the bottling business is on the upgrade, and business with Orange Kist this spring has most substantially emphasized it. . . . Those business men who stake their bank roll on the old sales methods that always made good before are due for a long ‘nightmare,’ and when they wake up, it will be another ‘Rip Van Winkle Story.’ The coming season is going to be one of good management and good salesmanship. The motto is going to be work, plug, and fight for it.”

At the 1924 bottlers’ convention in Pennsylvania, Eric Scudder outlined his “A, B, C’s” of the new industry: “Attractiveness, Business-Like Methods, and Courtesy.” According to the RE-LY-ON Bottler publication, he also added a “Q” for “Quality” and an “X” for the “Unknown Quantity.” Hmmm, not the best use of inspirational alphabetizing we’ve ever heard. But Scudder also pushed the idea of crafting a narrative and using all available resources at hand to help sell, including the fellas driving the trucks.

“Get a sales story about your product,” he told the bottlemen. “This sales story may be in the high quality of products handled in the manufacture of a beverage; it may be in the modern, sanitary plant; there’s a real sales story in your business—and you’ve got to tell that story to sell your goods. . . . Then see to it that your truck drivers learn that story and tell it—let them be truck salesmen instead of truckmen. Let them tell it until all the dealers know about it, for the prospect of today is the dealer of tomorrow.”

Scudder and Davies’ own specific sales pitch for Kist can be found in a 1923 magazine ad aimed at potential franchisee dealers within the trade: “We furnish you with not only the best fruit flavors made, but we give you in addition a most complete advertising and merchandising plan to build your business to a bigger volume than you ever did before. The plan is worked out to the finest detail—and we furnish free to you, window strips, hangers, and newspaper ads ready-to-run.”

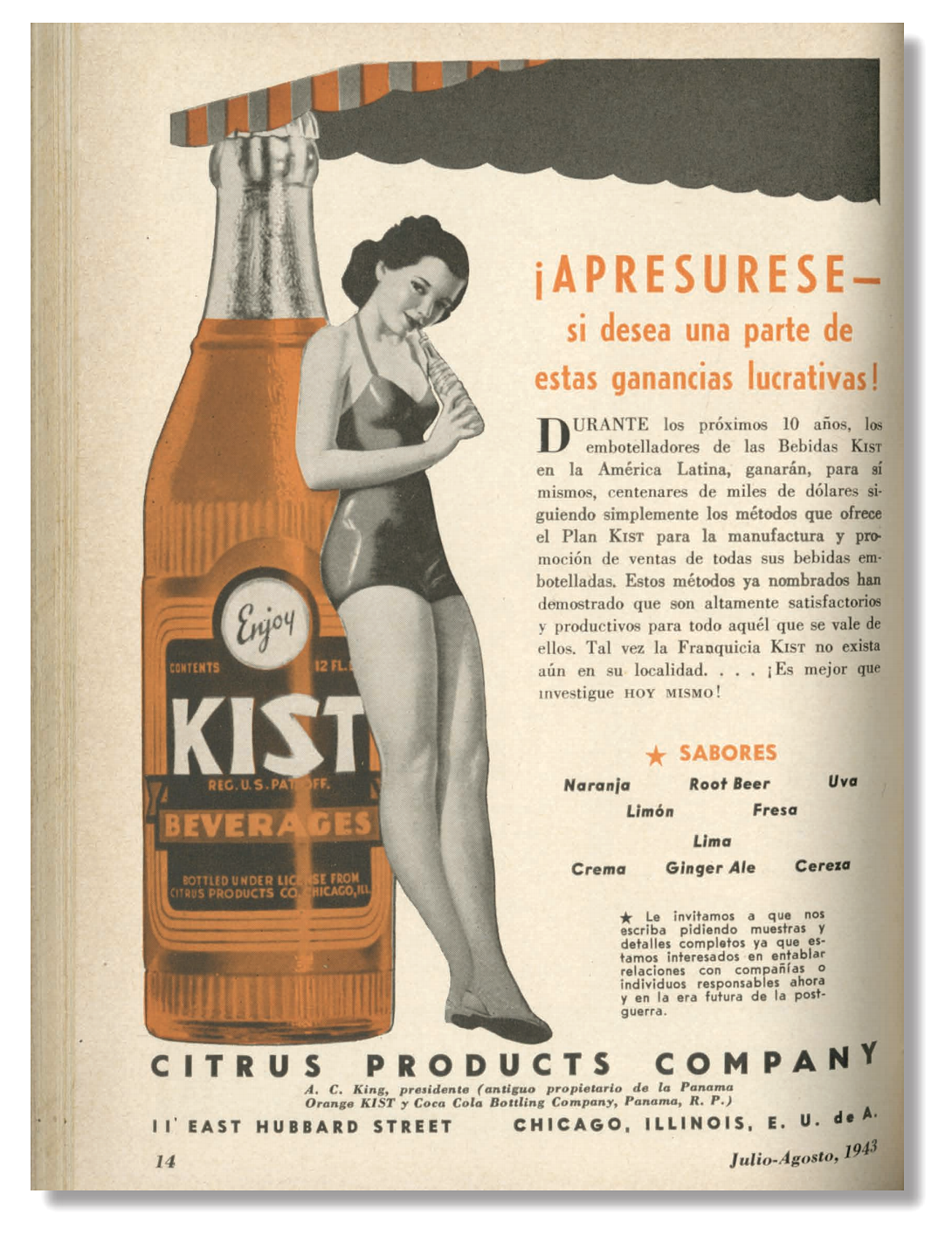

[Pin-up girls were a big part of Kist’s early marketing push in the ’20s and ’30s]

[Pin-up girls were a big part of Kist’s early marketing push in the ’20s and ’30s]

In smaller towns, the Citrus Products Company was granting exclusive Kist-selling rights to whichever distributor grabbed the dangling carrot first. “Perhaps your town is open—write and find out at once. Do it now—for this exclusive license is a gold-mine to you—if you act now.”

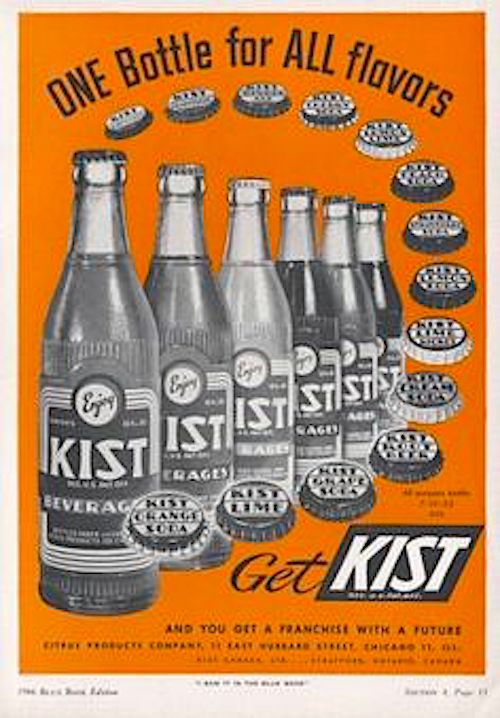

The more concise tagline soon became: “Get Kist and you get a franchise with a future!”

All of this colorful coaxing did its job, as the company and its network of distributors expanded rapidly through the 1920s. Some interesting new products were introduced—including a grape juice substitute drink called “Blue Bird,” the Yoo-hoo style “Chocolate Soldier,” and a “Frozen Sucker” that inspired patent lawsuits from the Popsicle Corporation.

In 1928, the executive board also had a new star recruit in the form of vice president Albert C. King, the Coca Cola Company’s former pointman in Central America. As young business partners, Scudder and King seemed to be perfectly in lock-step, and the future looked downright peachy for the Citrus Products Co. Unfortunately, peach was not one of the available Kist flavors, and the relationship would soon turn bitter in the most public of ways.

Part II. Shots Taken, Shots Fired

As the 1930s began, not even the doom and gloom of the Great Depression could thwart Eric Scudder and A. C. King’s goals for world domination. Now headquartered at 11 E. Austin Avenue (renamed Hubbard Street in 1936), the dynamic duo was doing all they could to make Kist an international name.

King—a native of Georgia—had experience in this kind of work, having personally orchestrated Coca Cola’s successful growth in Panama in the ‘20s. Now, he was putting his nephew Howard Francis King in charge of plotting a similar course with Kist throughout Latin America.

Meanwhile, Scudder had adopted another one of his innovations from his Orange Crush days, the unique “crinkle” bottle design (intended to look like sliced oranges). He demanded that all franchised bottlers use them exclusively for Kist drinks, and sent them loads of advertising concepts and promotional “event” ideas to put the bottle in more hands.

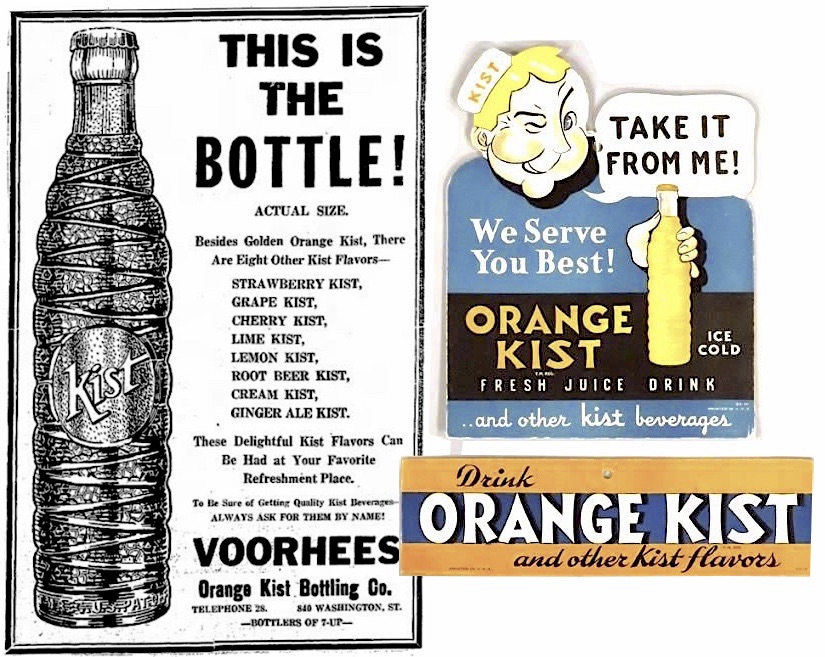

“This is the Bottle!” exclaimed a 1932 newspaper ad for the Voorhees Orange Kist Bottling Co. in Burlington, Iowa, complete with a life-size image of the crinkle bottle. “Besides Golden Orange Kist, there are eight other Kist Flavors—Strawberry Kist, Grape Kist, Cherry Kist, Lime Kist, Lemon Kist, Root Beer Kist, Cream Kist, and Ginger Ale Kist. These delightful Kist flavors can be had at your favorite refreshment place. Ask for them by name!”

That was the type of publicity the Citrus Products Company was more than happy to pay for. The type of publicity they got in the summer of 1933, however, generated quite a bit more attention, free of charge.

“Husband Seized for Shooting at Wife After ‘Stolen’ Party Kiss”

That was a front page headline in the August 21, 1933 edition of the Chicago Tribune. Printed alongside stories about Hitler’s rising extremism and the ongoing fasting protest of Mahatma Gandhi, this curious little nugget of local news reads more like the synopsis of a radio melodrama.

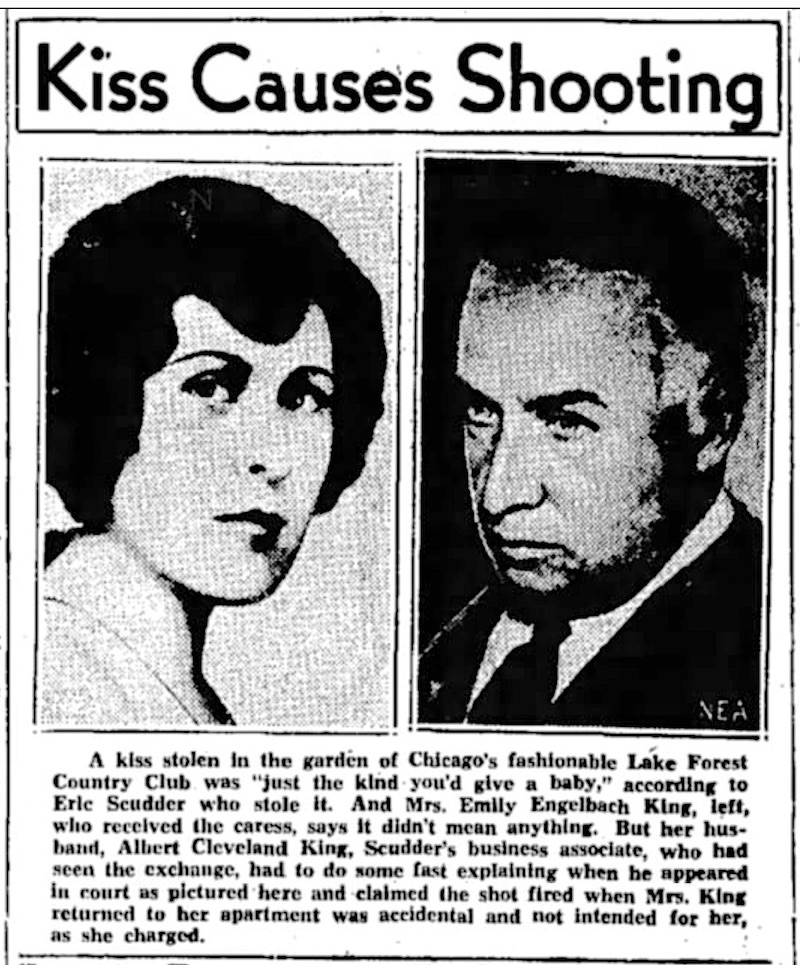

An AP report from the same day, published in papers nationwide, proclaimed that “Albert Cleveland King, 49 years old, executive vice president of the Citrus Products Company, was jailed early today on a charge of assault to kill after his wife Emily, 29, former Denver socialite, said he became enraged over a stolen kiss at a dance and shot at her.

{The victim, Mrs. King, and the accused, Mr. King.]

“Named in Mrs. King’s signed statement to police as the man who kissed her and aroused her husband’s wrath was Eric Scudder, 49, head of the company, who with his wife Marie had been host to the Kings and others socially prominent at a country club dance.”

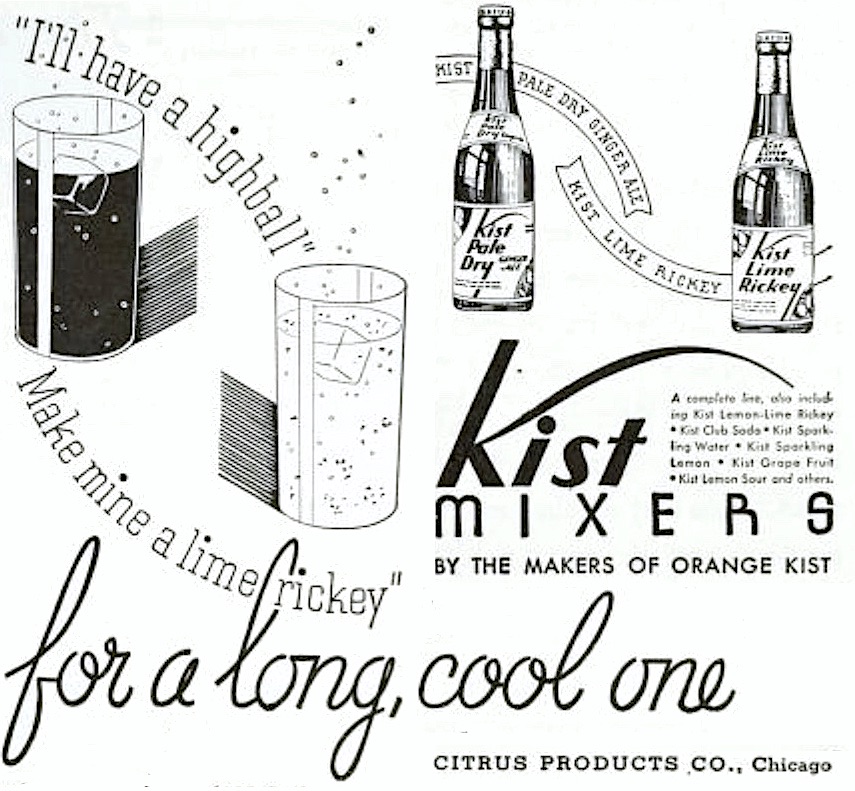

Yes, that’s right. After allegedly downing a few too many highballs (made with Kist mixers, no doubt) during a friendly gathering at the Knollwood country club in suburban Lake Forest, the vice president of the Citrus Products Company fired a gun at his own wife simply because she’d received a smooch from the president of the same company.

“The Scudders had long been friends of the Kings,” the report continued. “Scudder, Mrs. Scudder and Mrs. King all said they regarded the kiss as a trivial incident.”

Well, to be more specific, Eric Scudder told the press it “was just one of those things. No more to it than kissing a baby.” His wife of 20 years, Marie, backed him up, saying the idea of an affair “was just too silly,” while the victim herself, Emilie King, described something that would only be trivial only by the standards of the day, noting that Scudder “put his arm around me and hugged me; as I was pushing him away and telling him to stop, he kissed me. . . I had seen my husband meantime, and I called to him. He came up, knocked me down and at the same time called Mr. Scudder and me vile names.”

[Mrs. Marie Scudder, left, never doubted her own husband’s fidelity, even after he admitted kissing Mrs. King at the country club pool on the right]

[Mrs. Marie Scudder, left, never doubted her own husband’s fidelity, even after he admitted kissing Mrs. King at the country club pool on the right]

As the party came to an abrupt conclusion, Mr. and Mrs. Scudder consoled Emilie King and drove her back to the King family home, where Mrs. Scudder accompanied her up to the high-rise apartment. Unfortunately, the still fuming A. C. King was waiting for them, brandishing a gun.

“‘I’m going to send you to hell,’” he shouted, according to Mrs. King. “Then he fired the gun. Mrs. Scudder ran away, and I tried to follow her, but he grabbed me and said: ‘I’m going to settle you right now, and Scudder, too.’

“He held the gun against my head for ten minutes and kept threatening to kill me. I told him to remember our children, Albert, 3 years old, and Emily, 1, who were sleeping on the second floor. Then he let me go, explaining he wanted to get Mr. Scudder first.”

Instead, after Emilie retreated back downstairs to the Scudders, the cops were called, and A. C. King was dragged off.

“We’ve always been the best of friends,” Eric Scudder lamented to the press. “Of course, it’s a most unfortunate occurrence and is extremely embarrassing to everyone concerned.”

In court, Albert King claimed innocence, of a sort. “I didn’t mean any harm to her,” he muttered, according to the Tribune. “If I had wanted to, I could have harmed her. But I didn’t.”

King’s lawyer further claimed that the infamous “stolen kiss” had been a reciprocal embrace between Scudder and Emilie King, and that “Mr. King found his wife in another man’s arms; you can imagine what his feelings were at the moment. Later when he was at home he got a gun—his gun—without knowing quite what he was doing. He never intended to injure his wife. In fact, he didn’t fire the gun. It went off accidentally when he slipped on the tile floor.”

For over a week, Emilie King refused to appear in court herself to press charges, ignoring a subpoena. When she finally did decide to come in, she simply told the judge that she no longer wished to prosecute her husband. This was presumably a sacrifice made with her kids in mind. But it’s hard to overstate just how little justice was ultimately served in this case.

Not only did Albert King retain his freedom, his job, and his marriage, but within just a few months, he managed to oust Eric Scudder from the Citrus Products Co. “Yes, Scudder is out of the business,” King told reporters on December 18. “I bought him out. I’m president of the company now.”

The same reports mention that King was also reconciling with Emilie after she’d taken the kids with her to Arizona following the gun incident. “I’ve been out to see Mrs. King several times,” Albert said. “I’m getting ready to visit her again, too. I’m hoping that the difficulties we have had will be straightened out. I love her, you see.”

The reunited Kings would leave Chicago for Pasadena in 1937, but Albert remained president of Citrus Products’ Chicago operation until his death in 1947, when control of the business fell to Emilie herself.

III. Last Sips

“When you’re working your hardest, give your pop an extra push with Orange KIST and other delicious flavors! A moment of relaxation—a bottle of swell, full-flavored Orange KIST—and you’re all set to lick the world again! It’s mighty satisfying to have KIST Beverages in your refrigerator.” —newspaper ad, 1943

Scandals aside, the day to day business of the Citrus Products Company had remained on a convincing upswing right up to the outset of World War II. In 1938, A. C. King reported a net profit rise of 70%, and rewarded his employees in Chicago with a Christmas bonus worth more than one month’s salary. Meanwhile, expansion into Central and South America was continuing, as advertisements in trade magazines wooed Spanish-speaking bottlers, or “embotelladores,” just as they had done with regional distributors in the States.

One 1943 advertisement, translated from Spanish, read: “Hurry up if you want a share of these lucrative profits! Over the next 10 years, Kist beverage bottlers in Latin America will earn themselves hundreds of thousands of dollars by simply following the methods offered by the Kist Plan for the manufacture and sales promotion of all their bottled beverages. These aforementioned methods have shown that they are highly satisfactory and productive for anyone who uses them. The Kist Franchise may not yet exist in your area. . . You better do your research today!”

One 1943 advertisement, translated from Spanish, read: “Hurry up if you want a share of these lucrative profits! Over the next 10 years, Kist beverage bottlers in Latin America will earn themselves hundreds of thousands of dollars by simply following the methods offered by the Kist Plan for the manufacture and sales promotion of all their bottled beverages. These aforementioned methods have shown that they are highly satisfactory and productive for anyone who uses them. The Kist Franchise may not yet exist in your area. . . You better do your research today!”

Some production was slowed by wartime restrictions, including the milk-based Chocolate Soldier, which was discontinued until 1948. But bottled soda was still very much an “essential” of wartime life, both for shipment to soldiers overseas and their loved ones on the homefront. As such, Citrus Products continued making and promoting its KIST flavors, while also tweaking its regional ads to encourage patrons to buy War Bonds and do their part. By now, the familiar deco-style Kist label was also in wide use, with the slogan “Enjoy KIST Beverages” surrounded by red and white stripes.

After the war and Albert King’s death in ’47, much of the focus shifted to competing in the exploding vending machine market. There was a considerable disconnect between the Chicago offices of Citrus Products and new company president Emilie King, however, who remained in southern California. In 1951, she elected to sell her controlling interest to 43 year-old Henry S. Embree—a Dartmouth graduate, WWII Navy Commander, and son of a Chicago lumber executive.

With Embree as chairman and Don E. Woode as president, Kist rode the wave of America’s post-war boom. Kist drinks continued to sell for just a nickel throughout the 1950s, and while the brand never escaped its medium marketshare niche, Citrus Products Company was doing well enough that a move up from its longtime plant at 11 E. Hubbard Street seemed necessary.

“Citrus Products Company is expressing its confidence in the expanding soft drinks business and its own products with the construction of a completely modern new plant in Schiller Park, a mile and a half east of Chicago’s O’Hare Field,” the Daily Herald reported on October 27, 1960. “It will make possible a greatly increased production of flavors for Kist and Chocolate Soldier.”

The plant, which opened the following year at 9420 W. River Street, was a “one-story, fire proof brick edifice set up for high-speed operations. Modern in every way, its layout provides for a more efficient automatic processing line, modern materials handling, ample warehouse facilities, and faster shipping arrangements.

“New type chocolate powder mixers are among the many items of new equipment which will be installed in the handsome new building, Henry S. Embree, chairman of the company announced.”

[Above: The former Citrus Products plant at 9420 W. River Street, Schiller Park, as it looks today. Center Photos: The “basket type retort” (top) and “pallet loading retort” provided “highly efficient” methods for bottling the company’s chocolate drinks in the early 1960s. Also pictured: the Kist and Chocolate Soldier bottles as they looked in 1963.]

[Above: The former Citrus Products plant at 9420 W. River Street, Schiller Park, as it looks today. Center Photos: The “basket type retort” (top) and “pallet loading retort” provided “highly efficient” methods for bottling the company’s chocolate drinks in the early 1960s. Also pictured: the Kist and Chocolate Soldier bottles as they looked in 1963.]

That Schiller Park plant is still standing today, and while it doesn’t exactly look like a modern marvel, it once represented prosperity and security for the employees of the Citrus Products Company at the dawning of the Space Age. The dream didn’t last long, though.

Like A. C. King before him, Henry Embree died young, at just 55, in 1963. It may not have been clear at the time, but that event was the beginning of the end for the venerable Citrus Products Co.

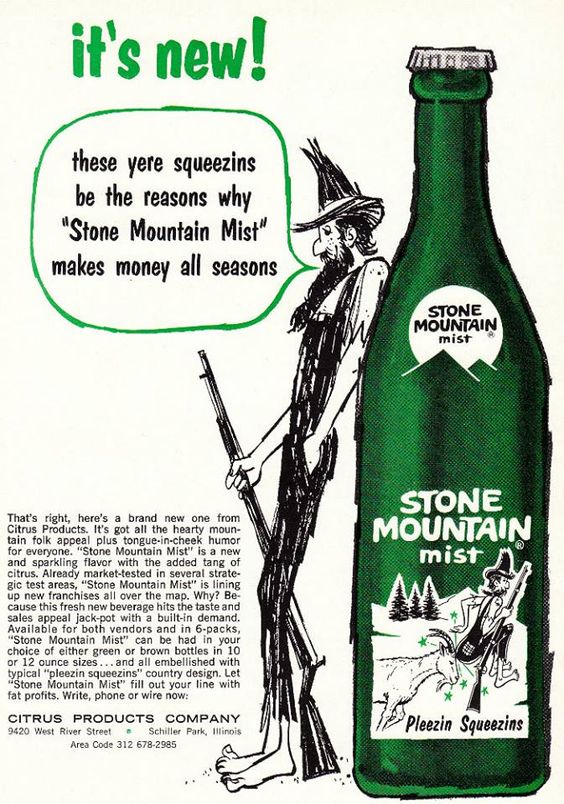

While the business was still keeping its head above water with the arrival of new products like Brownie (another chocolate drink) and Stone Mountain Mist (a Sprite / Mountain Dew type), the potential of teaming up with another mid-level flavor-maker was—much like becoming a Kist dealer—just too dang good to pass up.

While the business was still keeping its head above water with the arrival of new products like Brownie (another chocolate drink) and Stone Mountain Mist (a Sprite / Mountain Dew type), the potential of teaming up with another mid-level flavor-maker was—much like becoming a Kist dealer—just too dang good to pass up.

In April of 1965, Monarch Food Packers, Inc. of Atlanta paid a paltry $2 million (about $16 million after inflation) to take over Citrus Products and all its brands. The Schiller Park plant appears to have been abandoned shortly thereafter, as production was moved to Georgia.

As noted in the intro, the KIST brand survived for another 50 years after leaving Chicago, but it was increasingly relegated to the aisle of bargain bin, plastic jug soda pops, looking more like a Sunkist knockoff than a drink with a substantial history of its own.

Sources:

“Orange Crush Is Nationally Known” – The Hotel World, Vol. 88, No. 27, July 5, 1919

“Prohibition Makes Soft Drink Selling Harder” – Business Digest and Investment Weekly, August 20, 1920

Beyond the Eagle’s Shadow: New Histories of Latin America’s Cold War, edited by Virginia Garrard-Burnett, Mark Atwood Lawrence, Julio E. Moreno, 2013

“The Problem of Beverage Sales” – The Beverage Journal, May 1922

“Citrus Products’ Announcement” – The Beverage Journal, June 1922

“They Appreciate a Good Thing” – The Re-Ly-On Bottler, January 1925

“Citrus Products Co. (purchased by Scudder)” – Ice Cream Trade Journal, December 1923

“The Frozen Sucker War” – Prologue: Journal of the National Archives, Vol. 37, No. 1, Spring 2005

“Kiss Shooting to Aired in Court Today” – Chicago Tribune, Aug 21, 1933

“Kiss Shooting Told to Judge; Mrs. King Ill” – Chicago Tribune, Aug 22, 1933

“Orders Woman to Appear in Kiss Shooting” – Chicago Tribune, August 26, 1933

“Charge Against A.C. King Is Dismissed; Echo of Recent Kissing Episode” – Freeport Journal-Standard, Sept 1, 1933

“Rich Man Who Shot at Wife Seeking Reconciliation Now” – Oakland Tribune, Dec 19, 1933

“More Companies Grant Bonuses; Wage Increases” – Chicago Tribune, Dec 24, 1938

“Citrus Products Conducts Bottle Vender Survey” – Billboard, March 5, 1949

“Mr Henry S. Embree (buys Citrus Products)” – American Exporter, vol. 148, 1951

“New Plant to Open April 1” – Daily Herald (Arlington Heights, IL), October 27, 1960

“Henry Embree of Winnetka Dies at Age 55” – Chicago Tribune, June 18, 1963

“Citrus Firm Bought By Atlantans” – Atlanta Constitution, April 22, 1965

We’ve just celebrated our 50th anniversary of being the proprietors of Andy’s Jazz Club at

11 E Hubbard st Chicago, il. It’s been fascinating learning all about the beginning of our wonderful building. This past week we have been updating some of the woodwork that is our signature and has been since we first bought it. Upon replacing the wood ledge under the front windows, we discovered cutout well boxes centered between each window. Was wondering if anyone knows what they were for? Thank you so much.

My dad ran the Kist store in Hastings Michigan – I’ve got a large collection of bottles and a glass that was used at the restaurant which sold Kist beverages, ice cream and food. They closed the restaurant during the war.

My Dad owned a Kist beverages in Thorndike MA. His soda was just incredible. People would come all the way from New York and other far a way places to buy his product. Kist was a big name in our area. I miss it to this day.

While checking cattle in a field in western KY river bottoms I noticed a bottle in a cow path. Much to my surprise it doesn’t have any chips or Nick’s on it . It does have dirt stuck in the bottle neck. This is located close to a farm home that had slaves. I am curious to who drank this soda. ??! it is dated Jan 1924

I have a king kist beverage bottle that is still capped and bottled in 1965 which is filled with old, colored gumballs. Was this a promotional gimmick done by Kist Soda and how scarce are these? Is there demand and value for this type of promo soda item? Thanks! Charlie

I have a vintage matchbook lipstick folder that is a KIST advertising product with the address 11 E Hubbard St., Chicago, IL. Is there any value to you as a momentto?

My mother’s maiden name is KIST. Her Father’s name was Frederick Kist. They lived in Southern Indiana. Our family has always wondered if we are connected some way to the Kist Beverages company. Any ideas or connections that anyone knows of

Hi,

I am Eric Kist from CT and wondered the same. Are we related??

Thank you very much for the time taken to put together this story. I live on a small mountain in Northern California with a small drainage ditch that runs through it. After every heavy rainfall it never fails that I find the glint of some buried bottles and yes I came across a Kist bottle, unfortunately the neck was broken but since I had never heard of it I kept it. After reading the Kist history I think I’ll turn the bottle into a drinking glass so that when asked I can pass on this interesting history.

Thank you, Scott Ambrunn

We were dredging out one of our ponds here in the remote mountains of Central Idaho this summer and my wife spotted a bit of a glint off what turned out to be a mud-filled and covered bottle. She hopped into the mire, dug it out, and it was indeed a 7 oz. “Kist” bottle. The product had been bottled under a license granted to the “Old Faithful Beverage Company” in Idaho Falls, that city being about 180 miles southeast of here.

The number on the bottom reads “4586”, so was the bottle made in 1945 or 1986? Got any ideas?

good morning

Regarding the KIST, my grandfather Teobaldo Castañeda bottled that soft drink on the island of Margarita in Venezuela and I have very fond memories of it thanks for the incredible story.

Atte

Luis Jose Avila Castañeda

Thanks for this interesting post. I have never known this complete history and am glad you put this together. Very Appreciated. I have several old KIST patches, signs, bottles, and other memorabilia. Brian Embree – grandson to Henry S. Embree