Museum Artifact: Crane 1/2″ No 1204 Brass Globe Valve (c. 1930s) and 75th Anniversary Medallion (1930)

Made By: Crane Company, 4100 S. Kedzie Ave., Chicago, IL [Brighton Park]

“I am resolved to conduct my business in the strictest Honesty and Fairness; to avoid all deception and trickery; to deal Fairly with both Customers and Competitors; to be Liberal and Just toward Employees; and to put my Whole Mind upon the Business.” —Resolution supposedly made by R. T. Crane, July 4, 1855

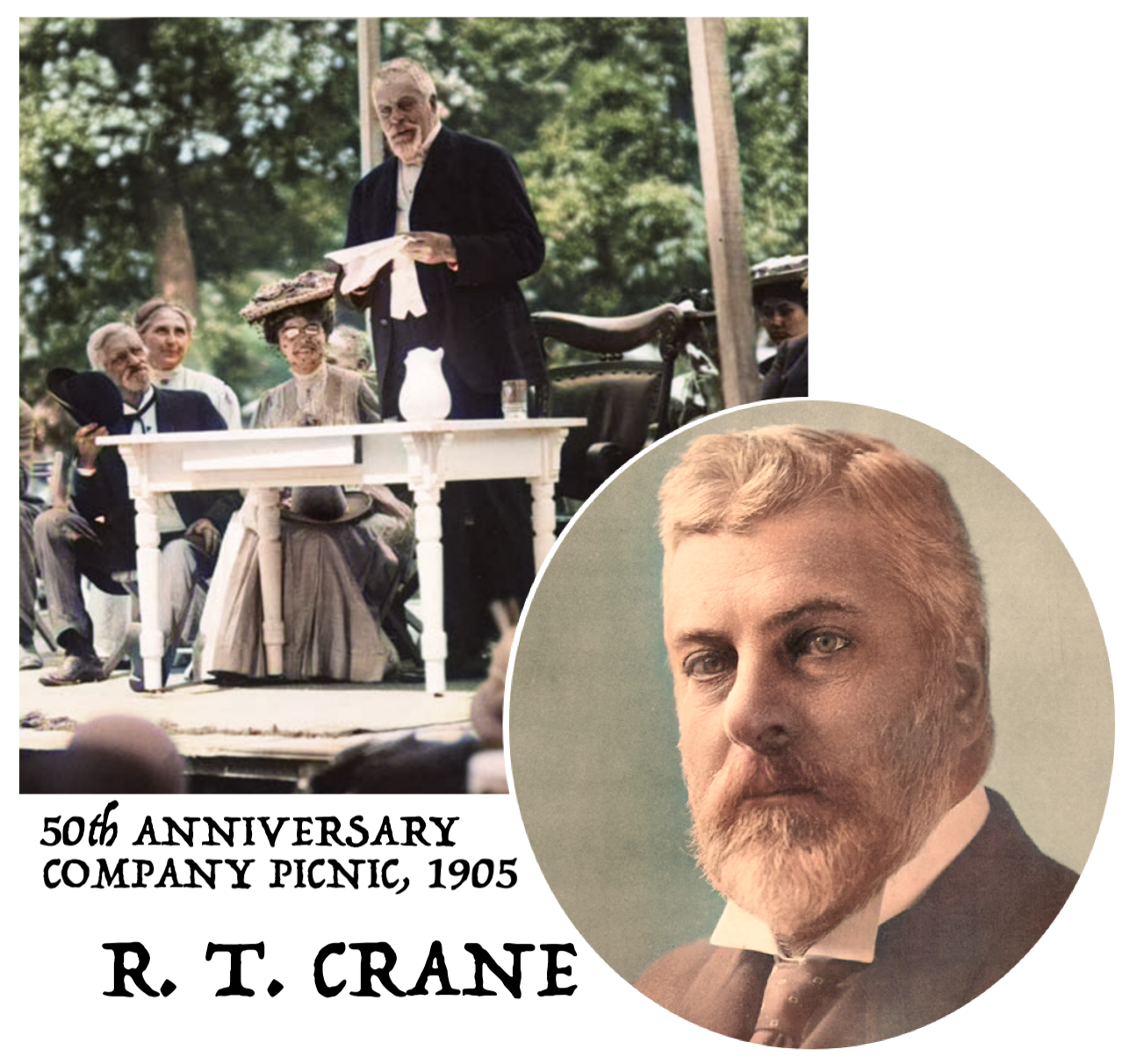

On the occasion of the 75th anniversary of the Crane Company—July 3rd, 1930—thousands of employees and their families were invited to Chicago’s Riverview Park for an industrial sized “company picnic,” complete with carnival rides, ballroom dancing, baseball games, track events, fireworks displays, a “Grand Circus Parade,” and performances by a murderer’s row of Depression-era novelty acts: the “Highland Band & Highland Fling Dancers,” “Organ Grinders with Monkeys,” the “German Hungry Band,” and the “Four Royal Hawaiian Strollers.”

On the occasion of the 75th anniversary of the Crane Company—July 3rd, 1930—thousands of employees and their families were invited to Chicago’s Riverview Park for an industrial sized “company picnic,” complete with carnival rides, ballroom dancing, baseball games, track events, fireworks displays, a “Grand Circus Parade,” and performances by a murderer’s row of Depression-era novelty acts: the “Highland Band & Highland Fling Dancers,” “Organ Grinders with Monkeys,” the “German Hungry Band,” and the “Four Royal Hawaiian Strollers.”

There was also a tug-of-war competition between the North End and South End employees of the mighty Crane Chicago Works—the 160-acre complex (eventually encompassing 72 buildings) in Brighton Park that was producing a substantial portion of America’s valves, pipes, and fittings.

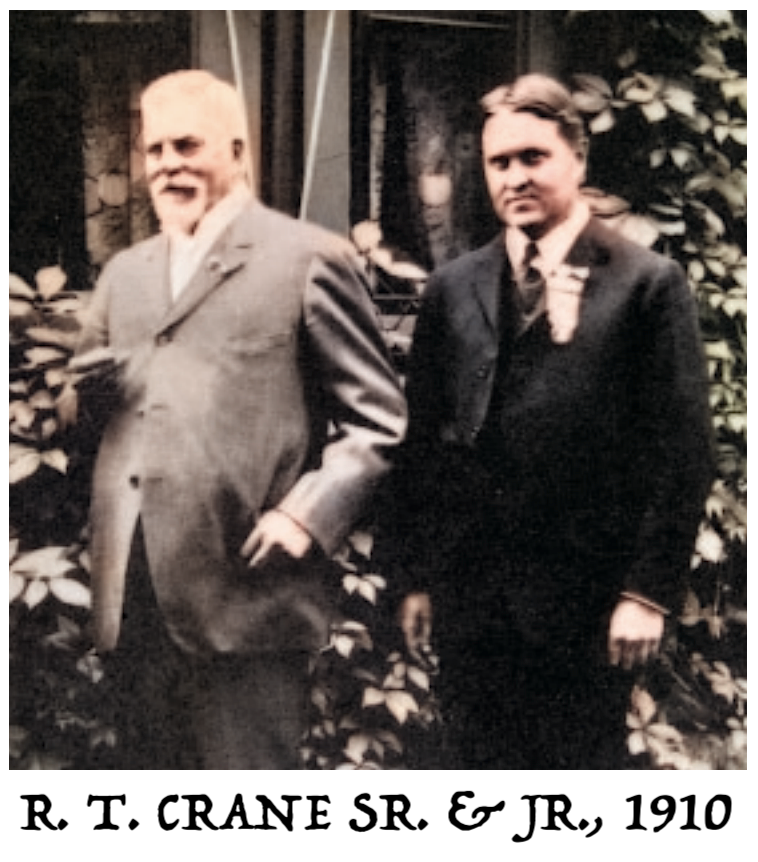

A commemorative 75th anniversary bronze medallion, as seen in our museum collection, was produced for the celebration, featuring a crow’s view of the modern Chicago Works on one side and the proud visage of the late company founder Richard T. Crane, aka “The Ironmaster,” embossed on the other. Somewhat coincidentally, ground had been broken on the Brighton Park complex in 1913, just months after R. T. Crane’s death at the age of 79. Under the control of his son, however, the Crane Company carried on in its founder’s image, utilizing a strong PR department to further mythologize the Ironmaster as the quintessential “self-made man” of American industry. One could quibble with that assessment, but no one could deny the massive international success of the Crane business, which remained a family owned, Chicago-based enterprise for roughly a century, before gradually morphing into the global, vaguely techy conglomerate it is today.

History of the Crane Company, Part I: The Brass Shop

For a company that achieved much of its success by pushing forward innovation, it was also consistently obsessed with its own humble origins and the lionization of its aforementioned founder. The “creation” story of the Crane Company was re-told so often, in fact, that it often took on the tone and rhythm of scripture.

“Young Crane was well pleased with the products he had made,” went one passage in Richard Teller Crane: His Life and Times (1955), describing the namesake’s first day in business. “. . . He realized that this was a day of great importance to our young country—and to the world.”

“Young Crane was well pleased with the products he had made,” went one passage in Richard Teller Crane: His Life and Times (1955), describing the namesake’s first day in business. “. . . He realized that this was a day of great importance to our young country—and to the world.”

“Richard was big—over six feet tall,” read another passage in The Crane Co.: Centennial Story. “He had a broad, sturdy frame and strong, masculine features. This hardy American pioneer of a century ago was known for his brain more than for his brawn—but he was known for his brawn, nonetheless.”

“On July 4, 1855, R. T. Crane poured molten brass from a small ladle into a molding flask,” began a company profile in a 1918 edition of the Manufacturing and Wholesale Industries of Chicago. “The scene of this operation was a small frame building in one corner of Martin Ryerson’s lumber yard, Canal and Fulton streets, Chicago. . . . The entire first operation in the original plant of Crane Company was performed by one man, the founder—and for fifty-seven years the head—of the company. Mr. Crane made the mold with sand found on the premises; he melted the metal, poured it, took out and cleaned the casting, and delivered it to a customer himself. . . . As Mr. Crane stood contemplating his first product lying on the earthen floor of that little brass shop, he made a resolution: ‘To conduct my business in the strictest honesty and fairness, to avoid all deception and trickery, to deal fairly with both customers and competitors, to be liberal and just toward employees, and to put my whole mind upon the business.’”

[For many years, the Crane Company maintained a replica of its first brass foundry for employees to visit. The same reproduction was used as a set for the company’s 100th anniversary film, The Second Hundred Years, starring Glenn Langan (left) as R. T. Crane, Sr.]

And thus, the church of Crane was born; forged in the sands of an unrecognizable frontierland Chicago, and soon to be global in scope; expanding metaphorically through the very valves and pipes that would form the inner workings of a modern, connected, 20th century world.

Gosh, it’s hard not to get dramatic and hyperbolic after reading about R. T. Crane for a few minutes. The tricky part is sorting out the legend from the facts.

For example, while Richard Crane would very much embrace his casting as the rags-to-riches American pioneer with Paul Bunyan looks and Thomas Edison cunning, it seems more than a small point that his original Chicago foundry—established in 1855 (probably NOT on July 4th)—was essentially gifted to him by his wealthy uncle and lumber magnate Martin L. Ryerson. You can still visit Uncle Ryerson’s tomb—a massive Egyptian-style mausoleum designed by Louis Sullivan himself—at Chicago’s Graceland Cemetery. So, suffice it to say, calling Richard Crane a “self-made man” requires some immediate interpretive tap-dancing around the definition of that phrase.

In all fairness, though, not everybody turns a good opportunity into a goldmine. And, indeed, Crane’s road to Chicago hadn’t been a complete cake walk, either.

In all fairness, though, not everybody turns a good opportunity into a goldmine. And, indeed, Crane’s road to Chicago hadn’t been a complete cake walk, either.

Born in Paterson, New Jersey, in 1832, Crane was forced to join the workforce by the age of 9, selling tobacco from a cart to make up for financial losses his family had suffered after the Panic of 1837. At the age of 15, following the death of his father, he was off to Brooklyn to start a highly formative “hard knocks” apprenticeship at the brass foundry of John Benson—another deal arranged for him by an uncle; this time Uncle Henry (Gasparo).

Young Richard trained for seven years as a brass man, and after the death of his mother in 1854, he was ready to “Go West” with the rest of the country’s ambitious youths, hoping to put his training toward a venture of his own. Arriving in Chicago, he set up shop in a 14’x24’ shack at the corner of Canal and Fulton Street, likely gifted with a shoulder shrug by Uncle Ryerson, his late mother’s brother. The image of the shack would later become the Crane Company equivalent of Abe Lincoln’s log cabin; an iconic symbol of its frontier roots.

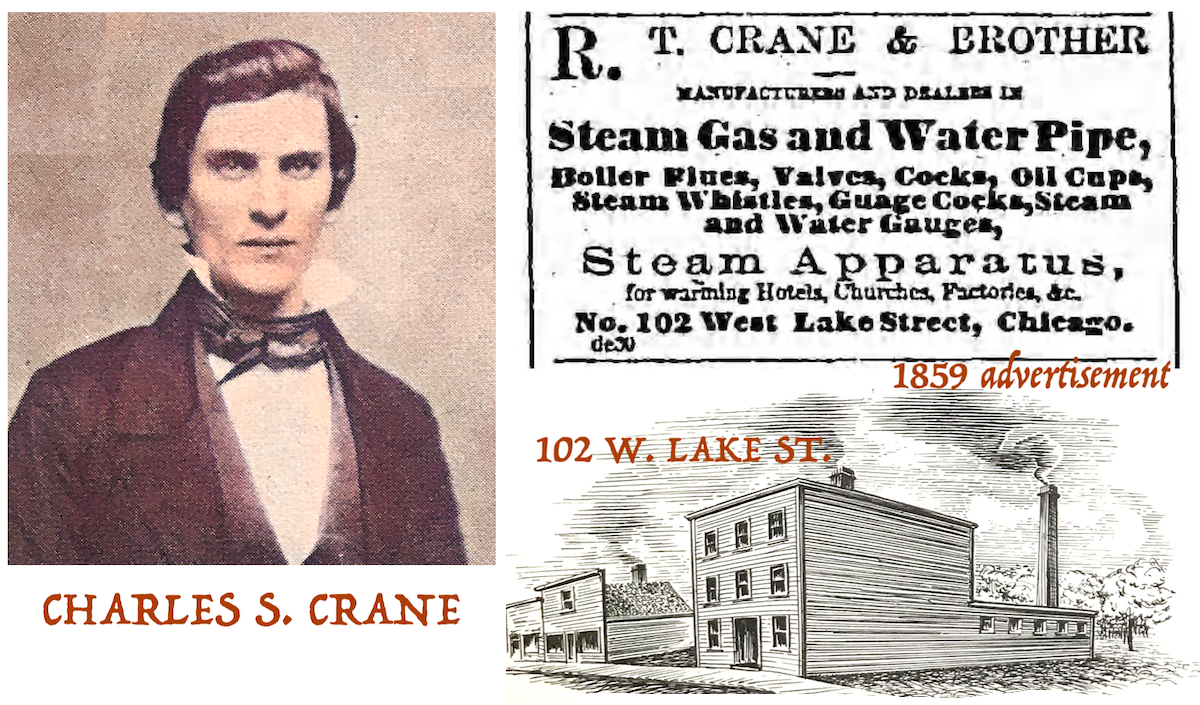

Of course, for practical purposes, the original shack wouldn’t last long. According to an 1856 edition of the Annual Review of the Trade and Commerce of Chicago, R. T. had already been joined in the business by his brother Charles S. Crane, as well as five other employees, making for a very cramped working space and, soon enough, a move to a larger facility at 102 West Lake Street. The firm, now known as R. T. Crane & Brother, was described in the same publication as a “brass founders and faucet factory . . . principally engaged in the manufacture of journal boxes from patent white metal and all kinds of brass and composition castings. The value of their manufactures from August 1st, 1855 to January 1st, 1856, amounts to about $10,000.”

It’s hard to say whether R. T. Crane’s personal drive was guided more by an obsession with mechanical efficiency or a profit-driven “manifest destiny” typical of his generation, but the two instincts were effectively complementary anyway.

Despite having no significant experience in the technology, the upstart firm of R. T. Crane & Brother applied for a contract in 1858 to install a “steam warming” system in the Cook County Courthouse. As the lowest bidder, they won the lucrative deal, but the celebration was brief. In order to affordably acquire all the hardware required for the job, they’d have to start manufacturing them in-house. And so, Crane became an overnight maker of pipe fittings, steam cocks, hook plates, branch tees, check valves, and globe valves (the latter of which were designed not all that differently from the 1930s model in our museum collection).

Contracts for new products begat the rapid development of dozens of new machines to produce them, and the Cranes were off to the races.

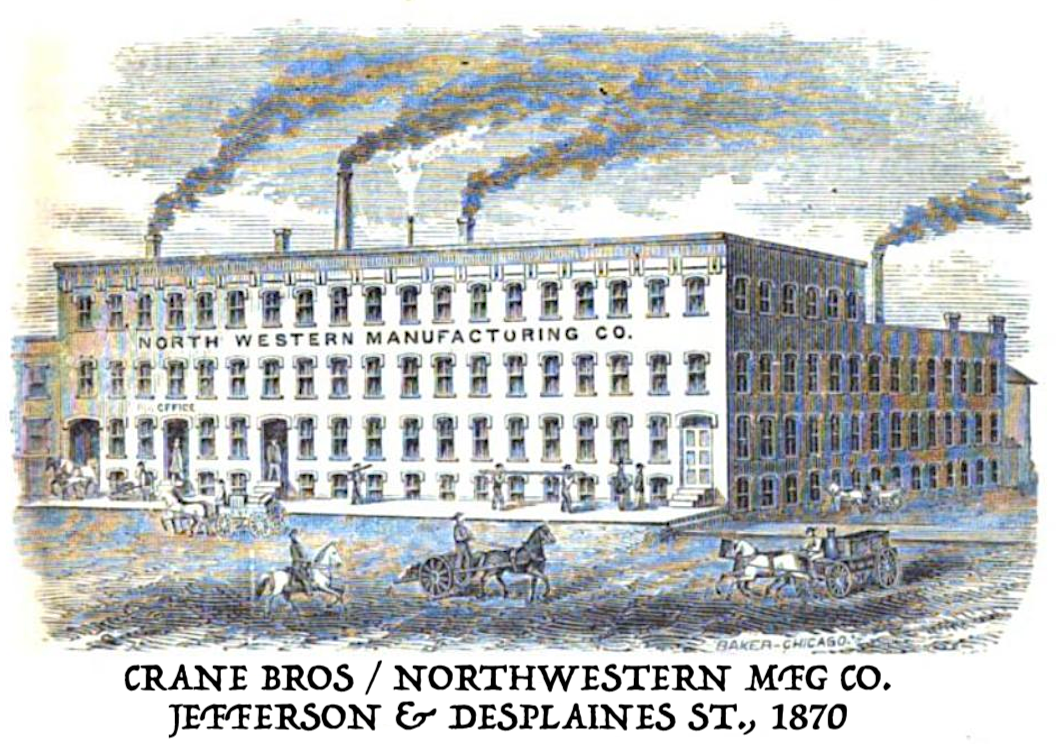

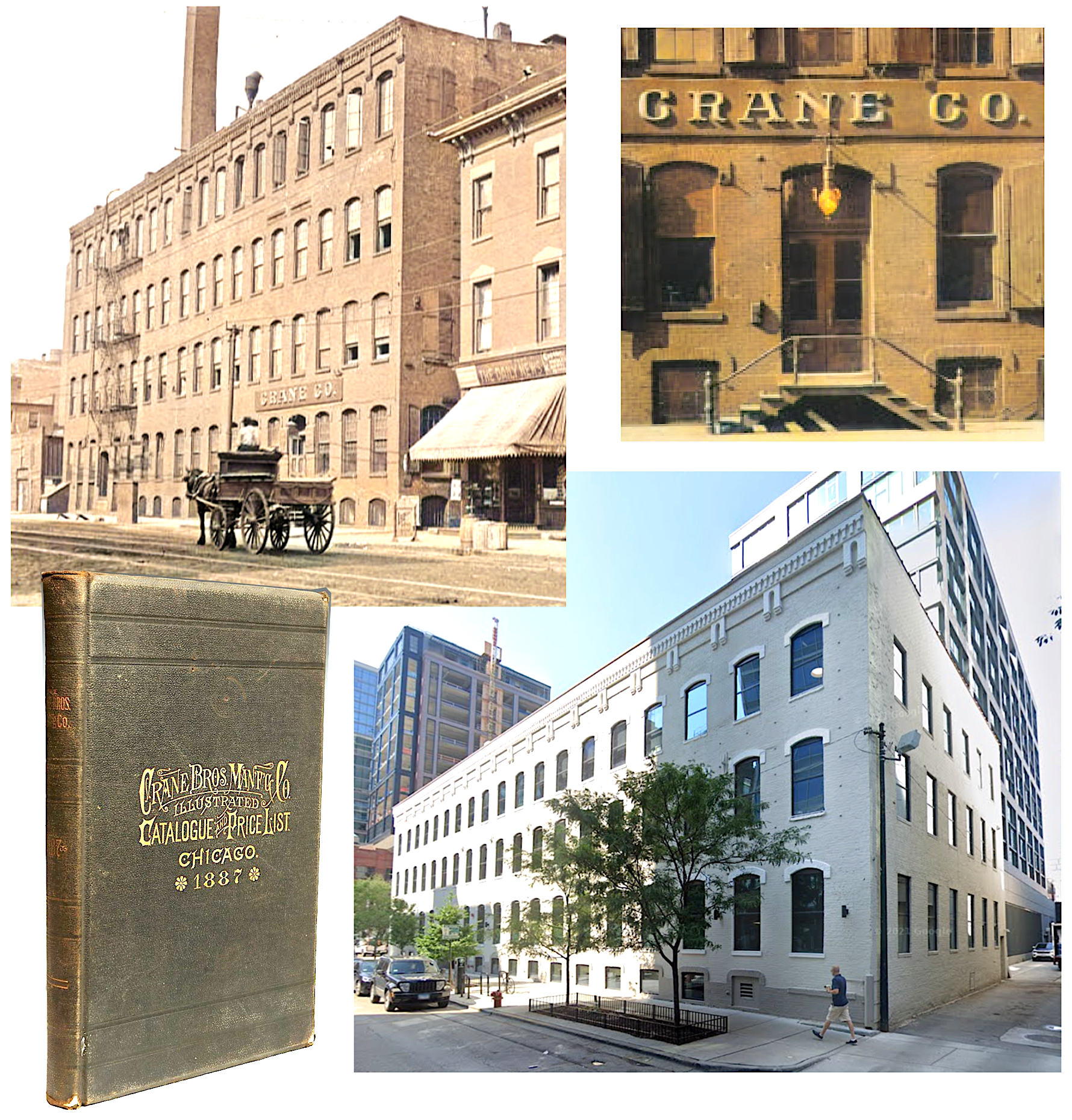

The Lake Street plant was enlarged in 1862, as new contracts for brass fittings during the Civil War (particularly for use in saddlery) gave another boost to the business. A wrought iron pipe mill and a malleable iron foundry (both the first of their kind west of Pittsburgh) were also established during the war, followed by a massive new headquarters at No. 10 Jefferson Street (today’s 156 N. Jefferson St.) in 1865. By now, the business—known briefly as the North Western Manufacturing Company—had increased its employee count to more than 200.

“We then decided,” R. T. Crane later recalled, “that the great success which we had met in our business warranted us making a radical change and branching out on a very much larger scale. . . . [We would] anticipate the wants of the trade. That is, instead of lagging behind, to bring out in advance articles that I could see would be needed.”

“We then decided,” R. T. Crane later recalled, “that the great success which we had met in our business warranted us making a radical change and branching out on a very much larger scale. . . . [We would] anticipate the wants of the trade. That is, instead of lagging behind, to bring out in advance articles that I could see would be needed.”

From steam pumps to early passenger elevators, the Crane Co. put its resources to increasingly innovative use. Even the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 couldn’t slow down their progress; a friendly wind had mercifully carried the flames away from Crane’s factories, and in the city’s subsequent re-build, Crane valves and pipes were instrumental to the birth of the skyscraper age.

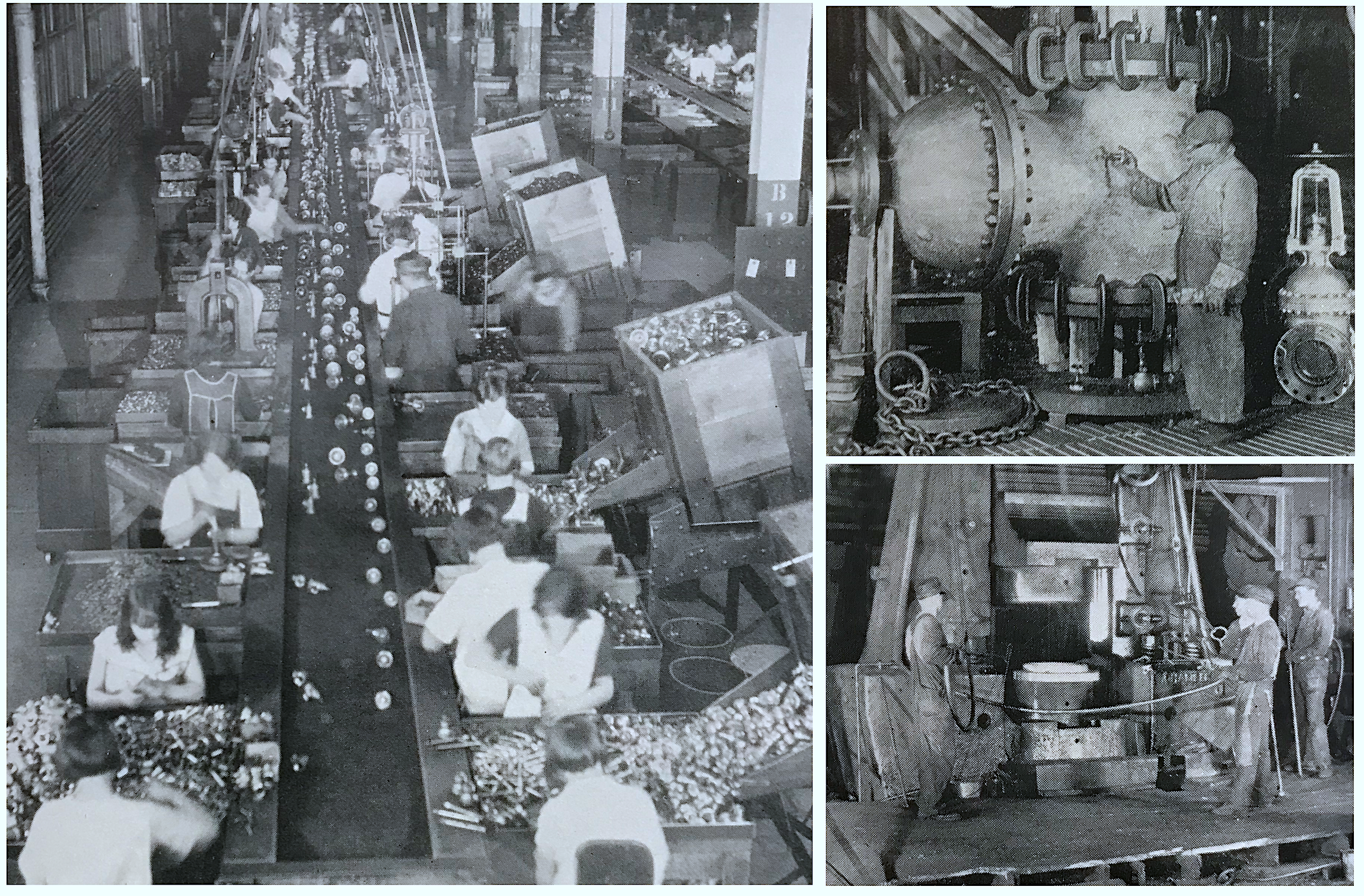

Not only was the company helping to guide the form and function of modern indoor plumbing; they were also re-inventing many aspects of metal manufacturing in the process. Using steam power, a clever conveyor system was developed to automatically move molds and pour hot molten metals. A merry-go-round casting machine devised by the Crane engineers was also arguably “the first significant improvement in the molding process in centuries” and the “first line production system in the metal-working field,” according to a 2014 retrospective edition of Valve World magazine.

During the 1880s, the Jefferson Street complex continued to expand, and the Crane Bros. Company (the “Bros” was dropped in 1890 following Charles Crane’s exit from the business) was one of the city’s recognized industrial behemoths, employing 2,000 people, with branch offices now open in Kansas City, Omaha, and Los Angeles.

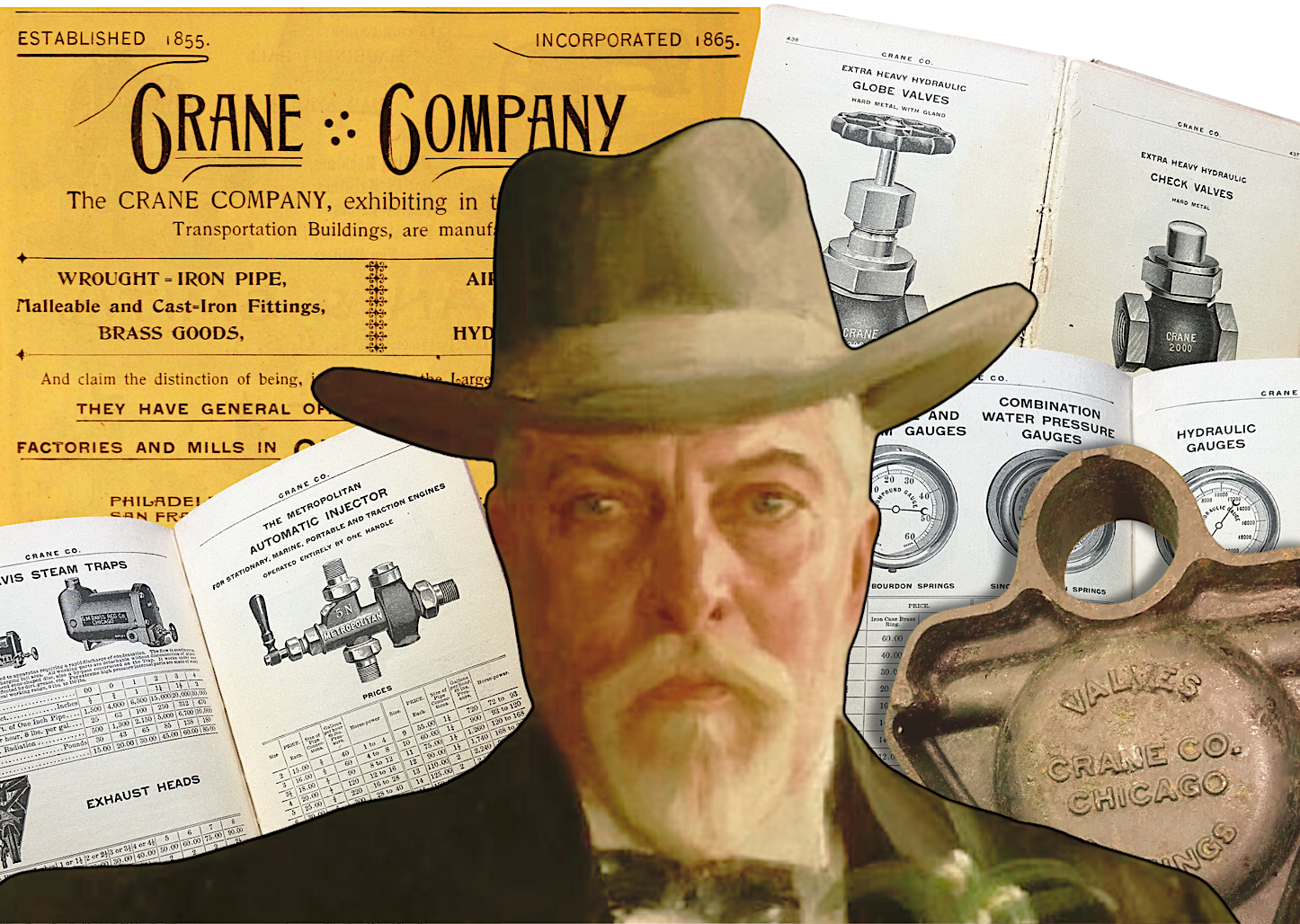

Still overseeing it all from the Chicago headquarters was R. T. Crane, a nearly 60 year-old tycoon now known respectfully as the “Ironmaster” or, by most folks in the office, “The Old Man.”

[Foreground: Richard Teller Crane, as depicted by Swedish artist Anders Zorn in 1904. Background: Various pages from Crane catalogs and promotions, turn of the century.]

II: A Dollar & Ten Cents

“A manufacturing experience covering a great number of years, close attention to detail, and complete facilities have made the name of the Crane Company a guarantee more valuable than any testimonial.” —Street Railway Review, 1895

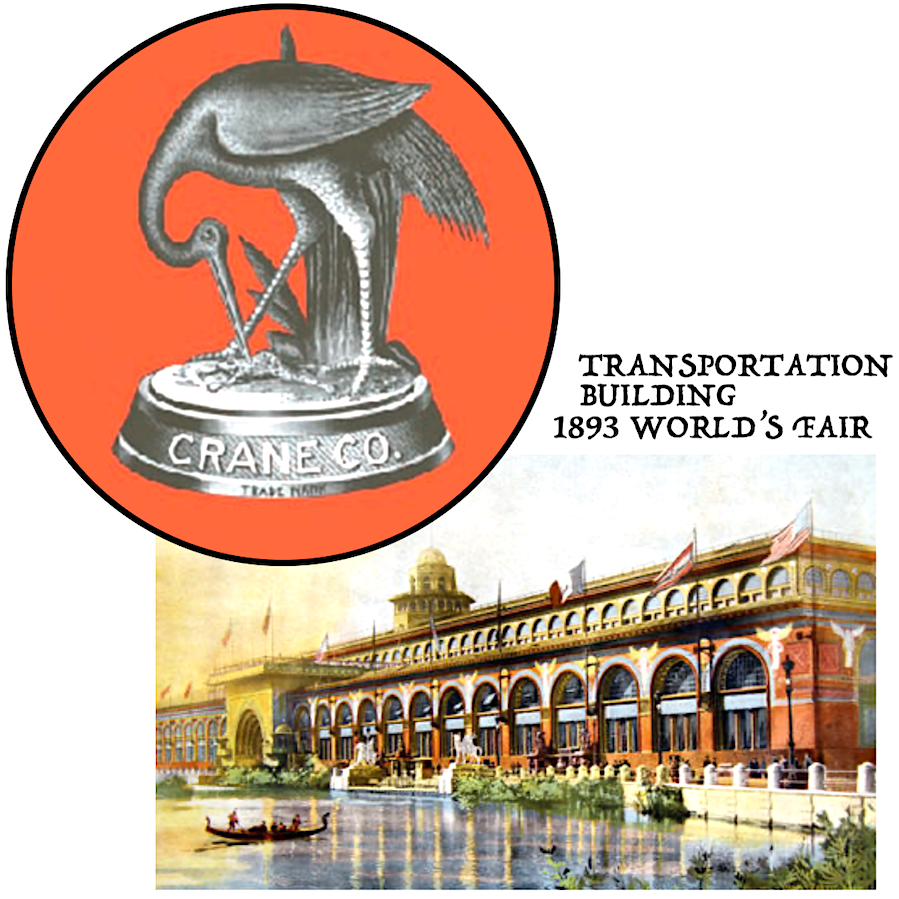

Naturally, the Crane Company had a strong presence at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, where it displayed its locomotive air brakes, elevators, and newfangled valve tech alongside the exhibits of Westinghouse and Edison in the Machinery and Transportation Buildings. Compared to some of the relative upstarts showcasing their wares in the White City, Crane had already weathered nearly 40 years worth of economic challenges and technological upheaval. The financial crisis of 1893 and the emergence of electrical power were just the latest hurdles that the company powered through (sometimes at the expense of its employees), as it continued to build up its national reach—opening a mill in Pittsburgh and more branch houses in Philadelphia, San Francisco, Duluth, and St. Paul.

Naturally, the Crane Company had a strong presence at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, where it displayed its locomotive air brakes, elevators, and newfangled valve tech alongside the exhibits of Westinghouse and Edison in the Machinery and Transportation Buildings. Compared to some of the relative upstarts showcasing their wares in the White City, Crane had already weathered nearly 40 years worth of economic challenges and technological upheaval. The financial crisis of 1893 and the emergence of electrical power were just the latest hurdles that the company powered through (sometimes at the expense of its employees), as it continued to build up its national reach—opening a mill in Pittsburgh and more branch houses in Philadelphia, San Francisco, Duluth, and St. Paul.

From that St. Paul branch, a young man was called to Chicago in 1895, tasked with overseeing Crane’s new high-pressure piping and valves department. Decades later, John B. Berryman would rise all the way to the role of Chairman of the Board, but at this point in his Crane career—as documented in his own 1942 memoir, An Old Man Looks Back—he was just the new guy at No. 10 Jefferson, caught up in the bustle of an organization with one foot in the 19th century and the other in the 20th.

[Crane Company headquarters at 10 Jefferson Street, now known as 156 N. Jefferson Street, as seen in the 1890s (above) and after a recent building renovation in 2023. The top floor of the building was removed many years earlier.]

“I had no feeling of being a stranger,” Berryman wrote, recalling his first day at work, “but rather that I was coming home to what I hoped would be my last job. . . . I was assigned a room on the first floor to the right of the main entrance. The city sales office was opposite, with the sales counter a little further down. Beyond the counter were stock bins. These offices had glass partitions so that you could see and be seen.

“It is possible to imagine a better office than the engineering department then had. We were directly under the brass finishing shop and at frequent intervals somebody would dump a barrel full of castings on the floor above and bring down a cloud of dust which had been accumulating since 1865. There was constant traffic through the entrance hall and a lot of noise. We became accustomed to dirt and noise after a while and paid no attention to it.”

Berryman, who was 30 years younger than his boss, R. T. Crane, still vividly remembered his various encounters with the “Old Man” long after becoming one himself.

“[Crane] was a large, handsome man of dominating personality,” Berryman wrote. “He dressed well, the only incongruous feature being high boots tucked inside his trousers, a relic of early days in Chicago. What struck you most was his piercing eyes, the terror of evil doers . . . which could bore through you.

“[Crane] was a large, handsome man of dominating personality,” Berryman wrote. “He dressed well, the only incongruous feature being high boots tucked inside his trousers, a relic of early days in Chicago. What struck you most was his piercing eyes, the terror of evil doers . . . which could bore through you.

“. . . In his own home, what little I saw of him there, he was a genial host; in the office, an autocrat whose word was law. Once given instructions to do anything, you did it, or got out. . . . He had a faculty for immediately detecting any stalling, or equivocation, and he came down on the delinquent like a ton of bricks. But straightforward frankness and clear thinking he understood, and those who met him that way got along well. . . . It might be inferred that such a stiff disciplinarian would be unpopular; the reverse was true. The men had extraordinary regard for him, and institutional morale was high.”

It’s hard to quibble with Berryman, considering he was on the scene, but his life-long managerial role with the Crane Co. might also make him a flawed witness when it comes to the true feelings the workers down on the factory floor.

Throughout R. T. Crane’s reign, labor relations in the Chicago plants were far from cuddly, as the Ironmaster held to a very strict philosophy: “Never spend a dollar unless you see a dollar and ten cents coming back.”

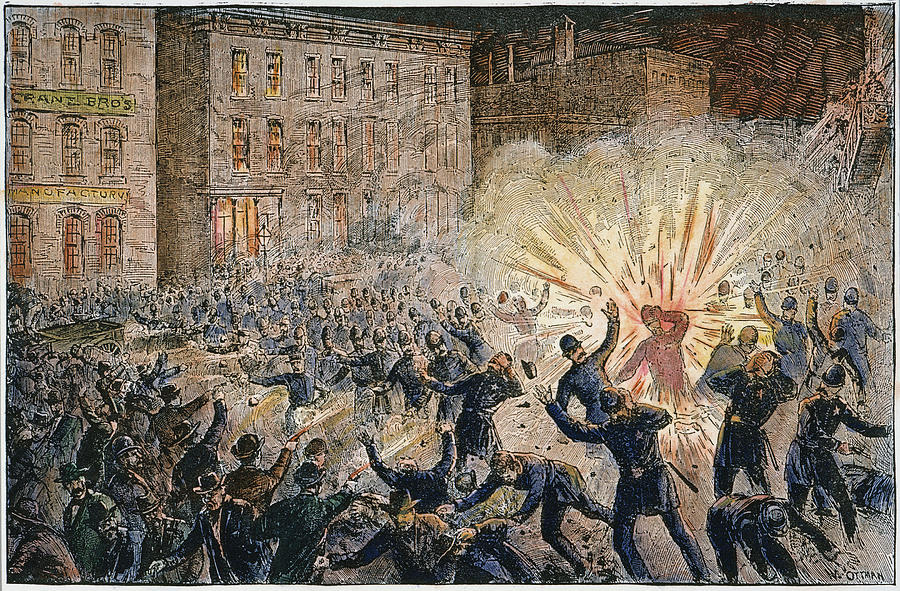

Back in 1886, during a widespread worker movement for an 8-hour workday, Crane threatened to close his shop entirely rather than bow to the trend. That May, a rally in support of workers outside the Crane building turned into one of the most infamous events in the city’s history, as a bomb thrown into the crowd by a protestor killed four men and led to the execution of four anarchists held responsible. The Haymarket Square Riot, as it came to be known, also undercut the efforts of Crane’s progressive workers; two weeks after the riot, they reluctantly accepted R. T.’s terms to continue with a 10-hour work day.

[Artist’s depiction of the Haymarket Riot, which occurred directly outside the Crane factory (present day 156 N. Jefferson Street) on May 4, 1886]

Later, in response to the drop in market prices after the Panic of 1893, Crane slashed workers’ wages by a massive 15 percent, which led thousands of employees to call a strike and take to the streets in the spring of 1894. Rather than meet them halfway, Crane instituted a lockout and ultimately “won” the conflict once again.

Not purely villainous, Richard Crane did direct increasing portions of his massive profits back into employee bonuses and other philanthropic causes later in his life. Not a dime of this money, however, was ever sent in the direction of America’s colleges and universities; institutions he disdained and increasingly railed against in the early 1900s . . . despite the fact that his own youngest son, Richard Crane, Jr., had attended Yale in the 1890s.

Crane, Sr.—the self-made man—was convinced that higher learning was a sham, and that college campuses were merely “nurseries of drunkenness and immorality.” Technical or vocational training, he felt, were all that any man should need after 8th grade.

“A young man who goes to college,” Crane wrote in 1909, “comes out so conceited that he is at a great disadvantage in getting into business, and it takes years, and sometimes a lifetime, to get his head back to a normal size. . . . The whole industry of . . . ‘higher education’ is to puff the young man up with vanity, causing him to look with contempt upon labor, and even to despise his parents.”

It’s hard not to read that passage without considering, again, that Crane’s own son, Richard Crane, Jr., was an Ivy League man at this point. And indeed, after the Ironmaster’s death in 1912, aged 79, it would soon be up to that “puffed up college boy” to take the reins of the Crane Company.

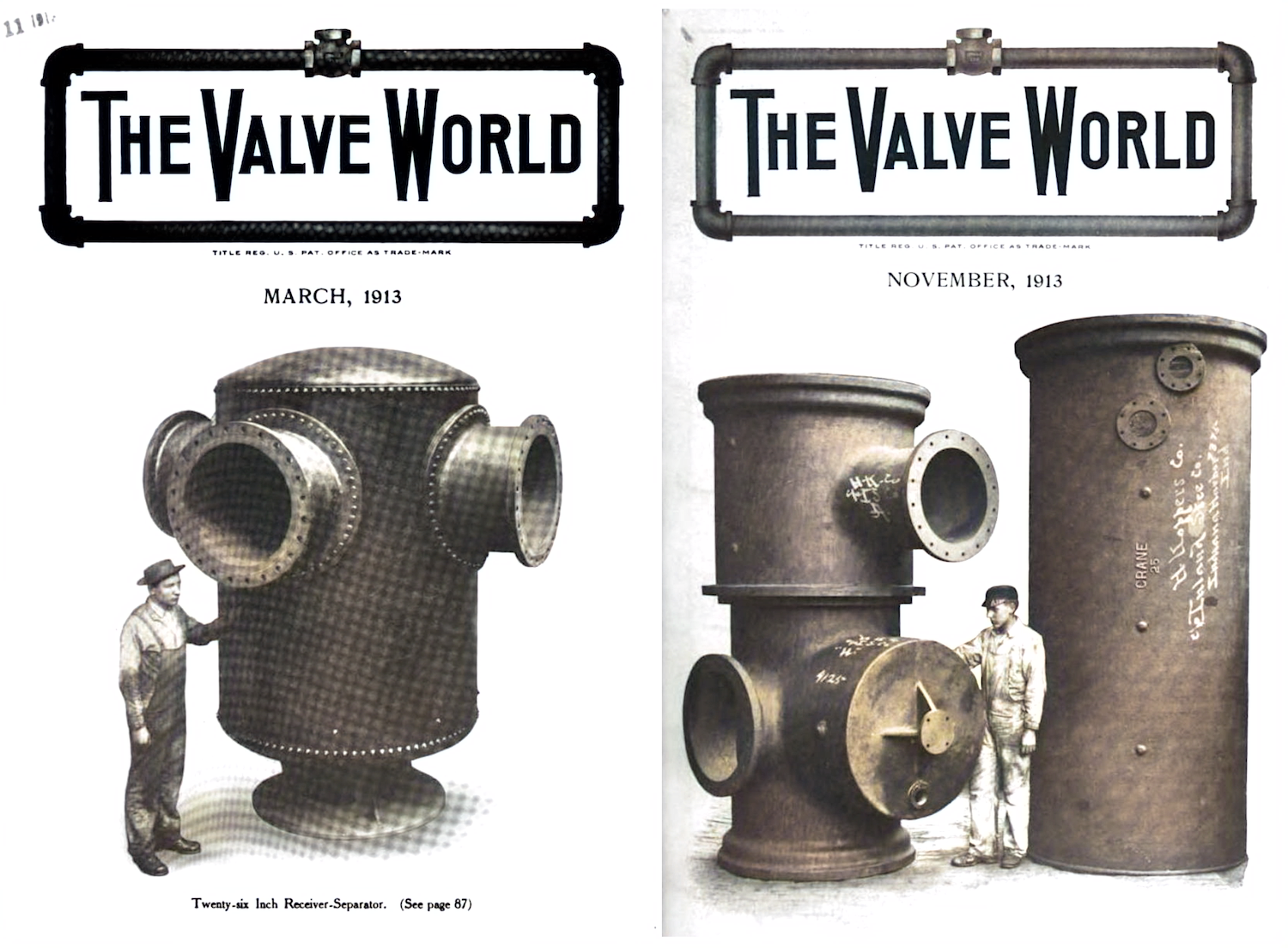

[Two 1913 issues of The Valve World, an industry magazine published in-house by the Crane Company]

III. The Crane Kids

R. T. Crane, Jr., was actually the youngest of the seven surviving Crane children. He had three older sisters—none of whom, of course, would have been considered for a role in the company based on their father’s less than progressive worldview—and also two older brothers. Herbert Prentice Crane was more interested in cattle farming than plumbing hardware, however, and eldest brother Charles R. Crane, while initially elected president of the company after his father’s death, had far bigger global ambitions.

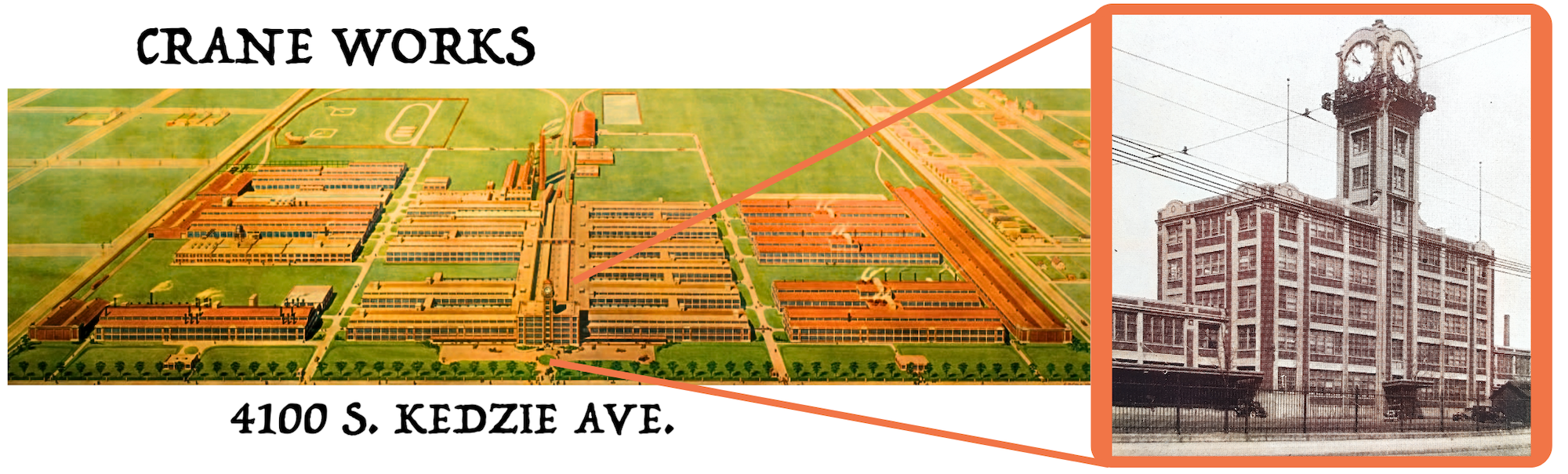

During a brief reign as company chief between 1912 and 1914, Charles Crane did write a couple very significant checks; one for Crane’s new, future-landmark office building at 836 S. Michigan Avenue, and another for the 160-acre tract of land along Kedzie Avenue that would become the Crane Chicago Works, envisioned as the modern, consolidated replacement for the company’s far-flung and deteriorating fleet of inner-city plants.

During a brief reign as company chief between 1912 and 1914, Charles Crane did write a couple very significant checks; one for Crane’s new, future-landmark office building at 836 S. Michigan Avenue, and another for the 160-acre tract of land along Kedzie Avenue that would become the Crane Chicago Works, envisioned as the modern, consolidated replacement for the company’s far-flung and deteriorating fleet of inner-city plants.

By 1914, though, Charles was the one receiving a check—a $15 million stock buyout from his younger brother, no less—as he permanently left the family business to put his fortune toward a new life as a power broking diplomat.

Described by one journalist as a “an eccentric American plutocrat obsessed with the idea of freeing the oppressed people of the world,” Charles was an ally of Woodrow Wilson, and later bought his way into the meeting rooms of major political figures and revolutionary movements from Russia and China to the Middle East. He was a major champion of the Arab world, and—it must be noted—was also an aggressive anti-Semite and a fan of Adolf Hitler, though he wouldn’t live to see the final results of that affiliation.

Charles R. Crane died on February 15, 1939, about six months prior to the outbreak of World War II. His effect on the Crane Company was minimal, but the company’s indirect financing of his dangerous political adventures was another issue altogether.

[The Crane Co. Building at 836-888 S. Michigan Avenue was built in 1912 and still retains most of its original exterior (including the Crane name over the entrance) more than 100 years later. Crane left the building in 1960, after which it was adapted for residential use.]

One could hope that perhaps Richard Crane, Jr., the younger brother and unapologetic college-goer, might be the apple that fell a bit further from the family tree. But at least according to John Berryman’s recollections, the mood in the Crane offices were not much improved by the arrival of “The Junior” in 1914.

“At this time Crane Co. was an out and out family affair under totalitarian rule,” Berryman wrote. “The board was made up of employees who had nothing to say until they found out what the president wanted. No free speech, practically no discussion, except when Junior was absent and I was in the Chair.”

What Crane, Jr., did have going for him, though, was blind optimism.

What Crane, Jr., did have going for him, though, was blind optimism.

With more than 9,000 workers already in his employ at the beginning of his presidency, The Junior remained steadfast in wanting to continue the Crane Company’s expansion goals. He wasn’t fazed by the skyrocketing costs tied to the ongoing construction of the Kedzie complex, nor did he seem concerned about America’s imminent entry into World War I. Instead, during the last half of the 1910s, a dozen new branches were established or acquired, including production facilities in Canada, England, and France. And they were paid for, in large part, by the war itself, as Crane had taken on significant government contracts, producing mortars as well as heating and sanitation gear for most of the new barracks built for the U.S. Army.

By 1919, with the war over and soldiers returning to their jobs at the fully modern, electrically powered Crane Works in Chicago, The Junior and his fellow executives anticipated a time of relative peace and contentment. Like his father before him, however, Crane, Jr., had a bit of a blind spot for the dissatisfaction of his workers.

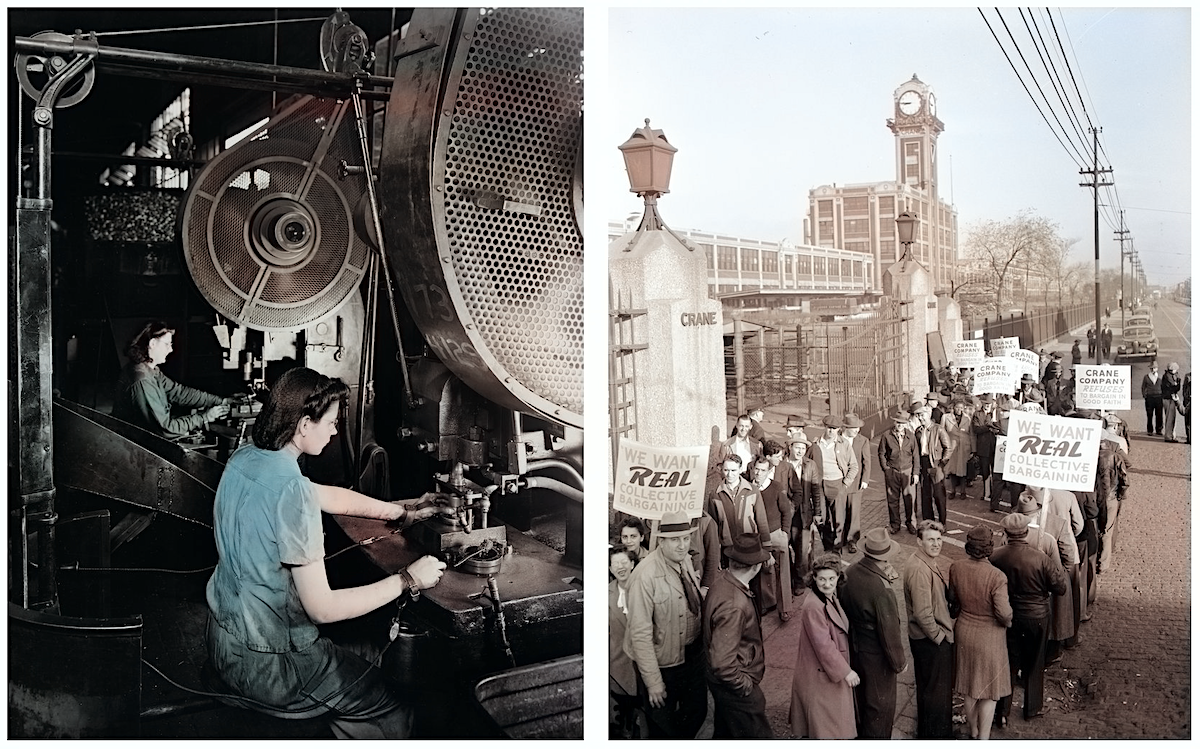

[Employees inside Crane’s Chicago Works, 1920s. The workforce increasingly included women after World War I]

IV. Sister Frances Sides with the Strikers

When 6,500 Crane workers walked out in the summer of 1919, the reaction from many of the powers-that-be was bemusement. John Berryman—who was now vice president of the firm—would later acknowledge in his memoirs that the board had been slow to raise wages during a cost-of-living crisis, but he also blamed the 1919 strike, rather callously, on mentally “unstable” military veterans now working in the factories.

“Our strike had its inception in the reckless desire of some ex-servicemen to start something,” Berryman wrote. “. . . About 50 ex-soldiers scattered through the plant, threw down their tools and yelled, ‘Strike! Strike!’ while stampeding the men like a herd of cattle. The foremen were caught flat footed and could not restore order. So we were in for it.”

“Our strike had its inception in the reckless desire of some ex-servicemen to start something,” Berryman wrote. “. . . About 50 ex-soldiers scattered through the plant, threw down their tools and yelled, ‘Strike! Strike!’ while stampeding the men like a herd of cattle. The foremen were caught flat footed and could not restore order. So we were in for it.”

Despite the sometimes violent protests that carried on over several weeks, Berryman claimed that Crane employees were paid more and treated better than those at competing firms. The Chicago Tribune seemed to agree with that assessment, with one article at the time claiming that there was “no reason at all” for the strike, and that the open shop policy of the Crane Company had been more than fair to both union and non-union workers, distributing regular Christmas bonuses and offering a pension system, sick benefit association, and free life insurance to all employees.

Unlike Crane labor conflicts of previous generations, however, a large portion the striking workers in 1919 were women, many of whom had come in for factory work during the war, and were now seeking fairer standards. This cause might have been largely dismissed by both their employers and the media, but they did get at least one significant vote of support from an unlikely source.

[Many of the Crane workers who walked out in July of 1919 were young women. Union organizers tried to create a more festive atmosphere on the picket line, with food and music provided during the gathering shown above from July 11, 1919]

Frances Crane Lillie—one of the older sisters of R. T. Crane, Jr.—was known as the “black sheep” of the family, but from another perspective, she was the admirable rebel, often standing in direct philosophical opposition to her father. Not only was she an active Socialist politically, but she’d also married a college professor (gasp)—Frank R. Lillie, a zoologist at the University of Chicago—and poured much of her own fortune into his place of work, something that unsurprisingly infuriated the Ironmaster in his later years.

The feelings were mutual. Frances, who was also a born-again Catholic of a sort, had developed a contempt for much of what her family represented; i.e., capitalism run amok. So, during the strike of 1919, she decided to write a letter to the union organizer behind the walkout, John Kikulski, in which she shared her opinions about the strike, the wider labor movement, and her famous family.

“It may not be of any importance to the striking Crane company people what one member of the family believes about the present industrial condition,” Lillie wrote, “but I feel sure that I must at least give my testimony.

“I am sure that my brother believes, and he is encouraged to believe it by his business associates, that he is a good and generous employer, but that cannot hide the fact that the Crane family is getting every year enormous sums of money from the labors of others without anything like commensurate returns to society for it.

“I am sure that my brother believes, and he is encouraged to believe it by his business associates, that he is a good and generous employer, but that cannot hide the fact that the Crane family is getting every year enormous sums of money from the labors of others without anything like commensurate returns to society for it.

“That is a sufficient evil in itself, but beside that we have throughout our organization a power over the lives of the employees that is intolerable in a modern society. For that reason I believe that the strike for the unionization of Crane company is absolutely wise and right, and the gradual assuming of control of their lives by the workers in Crane company is and must be only a question of time.

“There is no good act nor generous deed of any member of the Crane family that at all will or should invalidate this conviction. As for those of the family who have done little but injure themselves and others by the use of this unearned money, the sooner, for the good of society, their money is taken away from them, the better.”

It’s highly unlikely that Richard Crane, Jr., would have been moved by his sister’s strong words. Though he was by most measures one of the wealthiest men in Chicago, he preferred to think of himself, like his father, as a man of the people. In comparison to some of his contemporaries, he could probably even make a convincing case. The Junior was said to have personally gifted $13.5 million worth of his own company stock to employees, giving them more of a chance to personally benefit from Crane Co.’s success. Nonetheless, labor strife would continue during and after his tenure, as increasingly strong union solidarity finally scored some victories over the once immovable Crane economic ethos.

[Left: Women at work in the Crane Chicago Works, 1942. Right: Crane workers striking outside the plant on Kedzie Avenue, 1945. Chicago History Museum – Hedrich-Blessing and Sun-Times Collections]

V. Bathrooms & Blast Furnaces

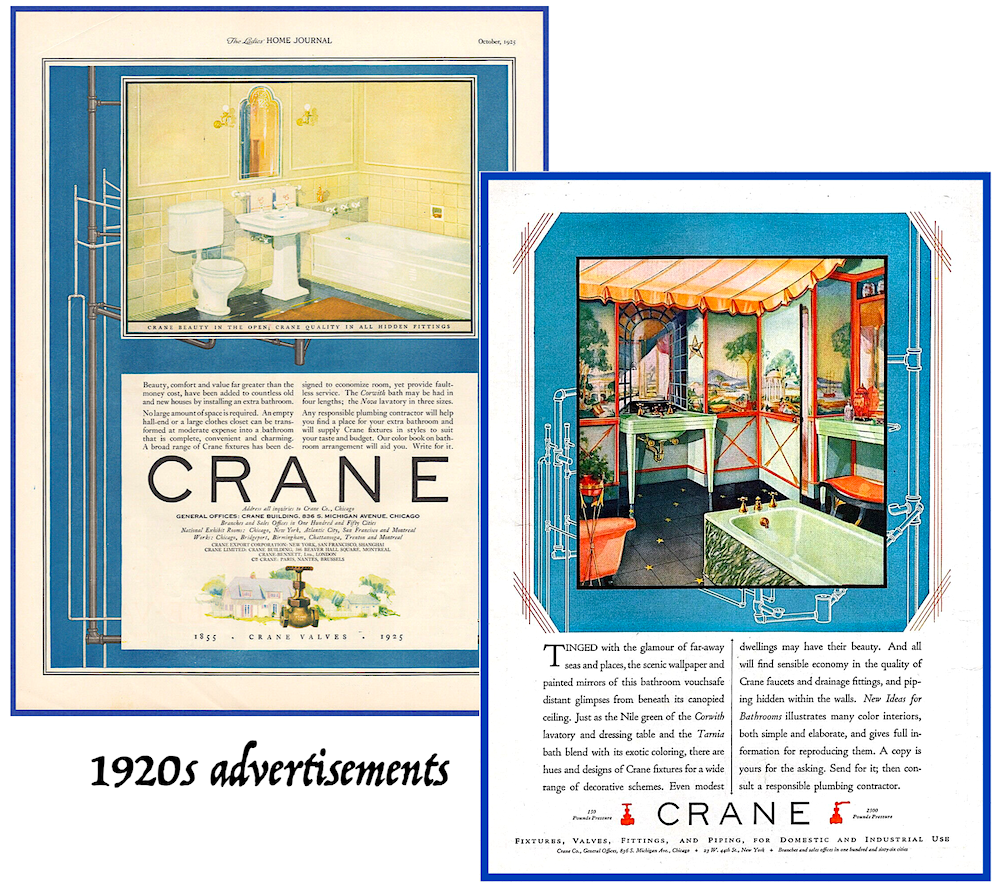

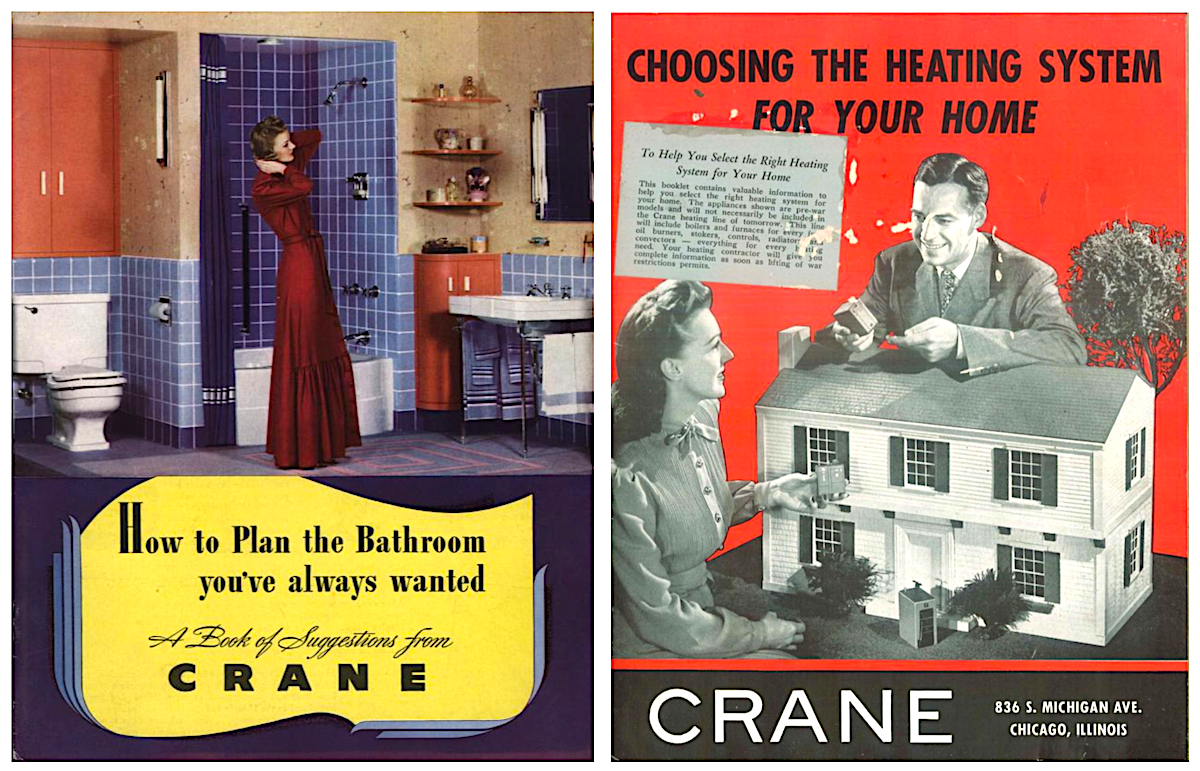

In the 1920s, the catalogs of the Crane Company began to more directly reflect the increasingly luxurious lives of its owners. During this period, R. T. Crane, Jr., and his wife—a woman with the cartoonishly aristocratic maiden name of Florence Higinbotham—commissioned an enormous new “summer home” on an estate known as Castle Hill in Ipswich, Massachusetts. And while it was built in the Tudor Revival style, it was very much a modern residence, equipped with the best in Crane plumbing and decorative bathroom fixtures.

“The bathroom, in many ways, is the most important room in the house,” read one passage in a 1926 Crane catalog titled Homes of Comfort. “When your guests go into it they gain an intimate glimpse of your personality. It need not be a ready made room, in a cold monotony of white, reminiscent of the hospital. With only the devotion of the careful planning which goes into the other rooms of your house, it may be made, like the Iiving-room, library or bedroom, to express your personal taste, your individuality. Through the use of such simple aids as color and hue, remarkable distinctive effects are being obtained. . . . To whatever plan your imagination may dictate or your architect devise, Crane fixtures and fittings will lend beauty and long, unfailing service.”

“The bathroom, in many ways, is the most important room in the house,” read one passage in a 1926 Crane catalog titled Homes of Comfort. “When your guests go into it they gain an intimate glimpse of your personality. It need not be a ready made room, in a cold monotony of white, reminiscent of the hospital. With only the devotion of the careful planning which goes into the other rooms of your house, it may be made, like the Iiving-room, library or bedroom, to express your personal taste, your individuality. Through the use of such simple aids as color and hue, remarkable distinctive effects are being obtained. . . . To whatever plan your imagination may dictate or your architect devise, Crane fixtures and fittings will lend beauty and long, unfailing service.”

Crane had clearly adopted an aspirational marketing campaign in line with the extravagances of the Jazz Age, and its brand—once associated more with big industries outside the public eye—was now on display in colorful showrooms across the country, including a prominent location on the famous Atlantic City Boardwalk.

Meanwhile, with the Chicago Works now in full operation, the company had more than twice the factory floor space it had had a decade earlier. According to Manufacturing and Wholesale Industries of Chicago, the majority of the new red brick buildings that comprised the Works were two-story designs, 50-feet long and eighty feet wide, with 40-foot courts between them and second-floor bridges uniting them (the one major exception in size was the main 8-story clock tower building at the front of the complex). “The general scheme on which the Works is laid out is to give an uninterrupted movement from the time the raw material is received until the finished product is shipped out,” with “five railroads” and a “comprehensive system of switch tracks” keeping the hive efficiently buzzing.

[Overview of the massive Crane Works along Kedzie Avenue, which would encompass more than 70 buildings at its apex. In lower photo, members of Crane’s Veterans League (employees with 25+ years experience) pose outside the Kedzie Works in 1925, next to a reproduction of R. T. Crane’s original brass foundry. The entirety of this industrial complex has since been demolished.]

Even with this massive new hub of specialized plants at its disposal (with heating and plumbing handled by Crane’s own clever engineers), Crane still was outgrowing Chicago with each passing year, as it continued to acquire many of its suppliers, from a bath enamel business in Chattanooga and a new boiler operation in Bridgeport, Connecticut, to a radiator production plant in North Tonawanda, New York. According to John Berryman, though, the company’s long run of profits and good fortune had clouded Richard Crane Jr.’s judgment a tad, and the seams of the business were starting to stretch just in time for the unfriendly new economic climate of the 1930s.

“Sales were slipping and competition was becoming sharper,” Berryman wrote in his memoir. “We wanted to take some canvas off the ship, but the Junior said it was a diamond jubilee year (1930), 75 years since the Founder had run the first mould, and he wanted it marked by good feeling. We had the good feeling right enough, but very little profit.”

Crane, Jr., spared no expense throwing the company’s massive 75th anniversary bash, taking over Riverview Park and producing no shortage of jubilee keepsakes and materials for the occasion, including the aforementioned medallion and a special edition of the company-run magazine, Valve World, which was sent out to all 20,000 worldwide employees of the company. Its pages included an interesting virtual tour of “Crane Town”—a sort of fanciful descriptive rendering of every corner of the company’s global enterprise.

Crane, Jr., spared no expense throwing the company’s massive 75th anniversary bash, taking over Riverview Park and producing no shortage of jubilee keepsakes and materials for the occasion, including the aforementioned medallion and a special edition of the company-run magazine, Valve World, which was sent out to all 20,000 worldwide employees of the company. Its pages included an interesting virtual tour of “Crane Town”—a sort of fanciful descriptive rendering of every corner of the company’s global enterprise.

“As we enter the vast floor of the cast steel foundry,” began one particularly long passage, “imagination recalls classical descriptions of Vulcan’s grotto under Mount Etna. The impressive electric furnaces, the play of colored flames ranging through every tint of the spectrum, the steady roar from melting metal and the deafening clatter of machinery, the film of haze over everything, the almost grotesque shapes of the workmen as they pass between us and a flash of varicolored flame, yet the precision and orderliness of his mechanical servants, all suggest to fancy that the ancient god of fire and metal-working is sitting somewhere in the smoky atmosphere and directing his cyclopean craftsmen.”

[Inside Crane’s Chicago Works at Kedzie. Top Left: Foundry Floor, 1930. Bottom Left: Machine Shop for valves and fittings, 1930. Center: Artist’s depiction of the blast furnace, 1930. Top Right: Worker using grinding tool, 1945. Bottom Right: Foundry workers, 1943]

Unlike Vulcan, Richard Crane, Jr., was merely mortal. And in the year following the 75th anniversary, he began to lose the faith of his fellow executives.

“The operating men knew that we were in for serious trouble,” Berryman recalled, “but [Crane] would not, or could not see that the conditions in the country were very bad. He thought the selling division was laying down on the job. This was an illusion. The selling division was doing all it could, but no one can sell anything unless there are buyers.”

Before he could realize his error in judgment, R. T. Crane, Jr., died suddenly from a stroke in November of 1931. He was only 58.

“No finer man ever headed a company,” Berryman wrote, but with the caveat that his boss was also “too optimistic. He had not come up the hard way like his father. He would spend freely, sure that tomorrow would fill up the chest again.”

[Crane Steel Valves in a storage room at the Chicago Works, 1930]

VI: A Valve for Every Purpose

“A trip through the Chicago Works in those bleak days was a depressing experience. The flow of material through the shops had fallen from a river to a trickle and in the acres of idle space, the black machines stood silent and waiting.” —John Berryman, Crane Co. president, describing the Depression years

In contrast to the 1920s, the ‘30s were a time of holding the line at Crane Co., rather than unbridled expansion. It wasn’t until the outbreak of World War II—and a new rush of government contracts—that the business fully kicked back into gear and regained its focus.

In contrast to the 1920s, the ‘30s were a time of holding the line at Crane Co., rather than unbridled expansion. It wasn’t until the outbreak of World War II—and a new rush of government contracts—that the business fully kicked back into gear and regained its focus.

As they had during the First World War, Crane’s plants produced a huge portion of the valves, fittings, and piping needed for the Allied war effort. And while these contributions were less glaring in their visibility than those delivered by munitions plants, they were no less critical. As such, the Crane Chicago Works was presented with an Army-Navy “E” Award in 1943, with 15,000 “E” pins handed out to the company’s workers.

[Top Left: Program from the 1943 ceremony in which Crane was presented with the Army Navy E Award. Bottom Left: E Award ceremony with “Valves for Victory” banner. Center: Inside the Crane Chicago Works during WWII (Chicago Historical Society). Right: Wartime advertisement for Crane Valves]

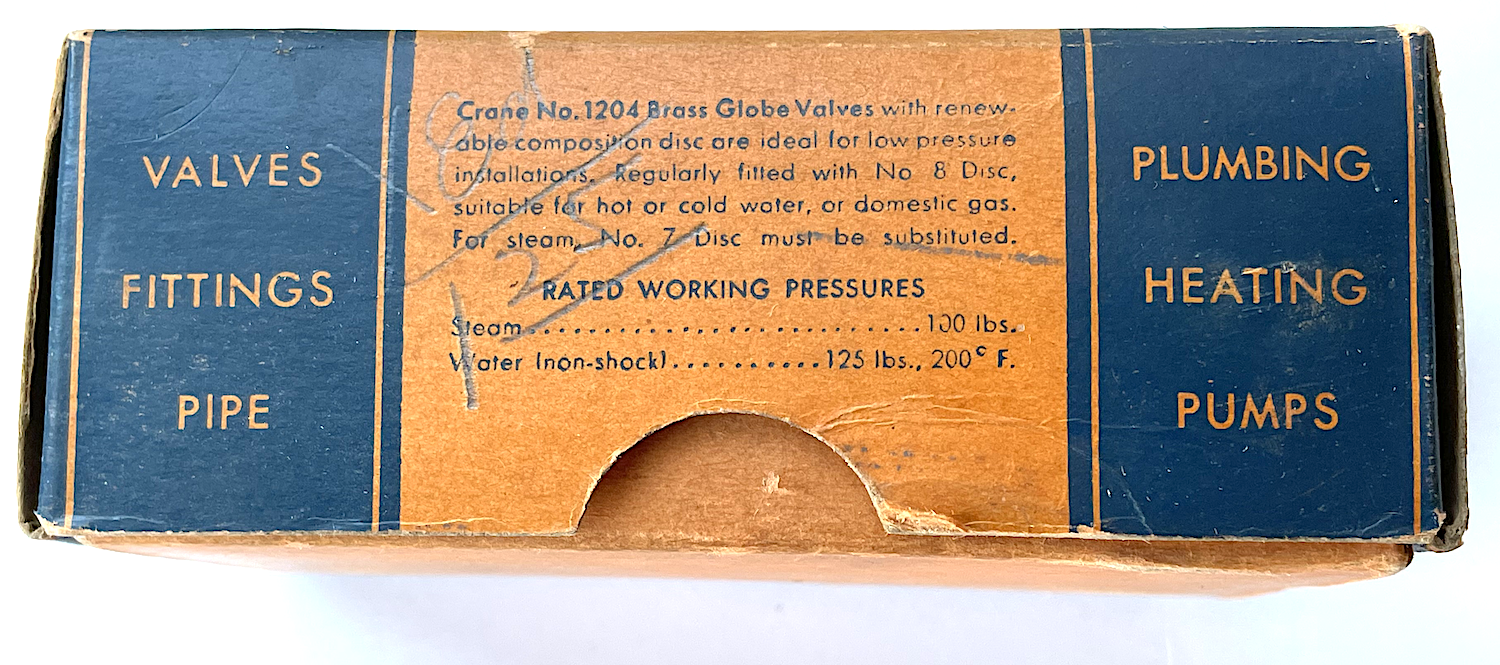

Because the company was still producing many of its usual products during the war, they had a smoother transition than most back into peacetime. This would include the manufacturing of everyday, ho-hum valves like the No. 1204 Brass Globe Valve in our museum collection. The half-inch No. 1204, was “ideal for low pressure installations,” with a rated working pressure of 100 LBS (steam) or 125 LBS at 200 degrees F (water).

“There’s a Crane valve for every purpose,” read a 1944 advertisement, “thousands of different sizes and types to control the flow of water, steam, air or gas—each built for unfailing dependability in the use for which it is intended.”

Beyond manufacturing all these valves, Crane had also become a leader in the research and science behind the entire industry. The company’s self-published 1942 technical handbook, Flow of Fluids Through Valves, Fittings and Pipe, became a pocket bible for plant and safety engineers, operators, and technicians over the ensuing decades. The company’s engineers weren’t always visionaries, however, as during this same period, most Crane valves were packaged with gaskets and asbestos packing, setting up a long legacy of litigation in the subsequent era of mesothelioma lawsuits.

VII: The Evans Era

VII: The Evans Era

While Crane was still best known as a plumbing and fixtures company in the 1950s, it was reaching the end of its first incarnation as a family-run, Chicago-based business.

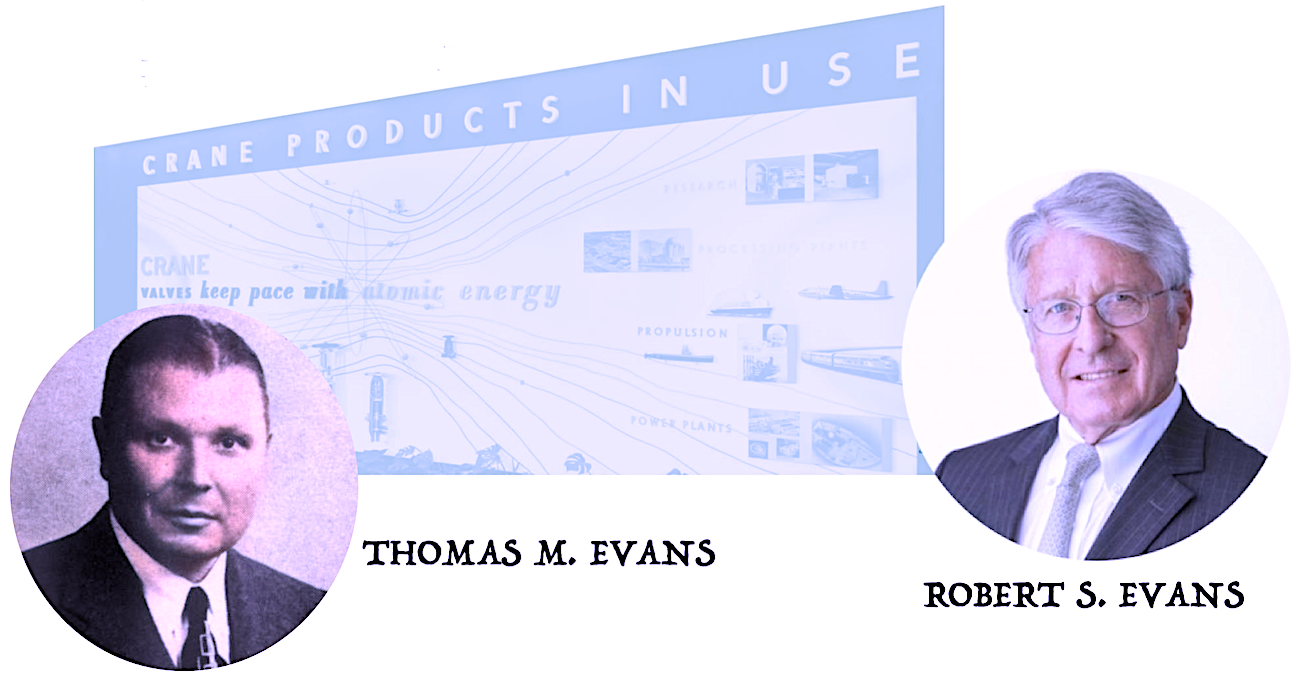

In 1959, after several years of slumping sales, the last Crane family stakes were sold, and a new chairman, Thomas M. Evans, took aggressive hold of the 104 year-old company.

In 1959, after several years of slumping sales, the last Crane family stakes were sold, and a new chairman, Thomas M. Evans, took aggressive hold of the 104 year-old company.

It’s hard to say whether R. T. Crane, Sr., would have approved of Evans, who was both a self-made man (check) and a Yale grad (uncheck), but if anything, the new company boss was ahead of his time; described decades later by the New York Times as “arguably the first corporate raider” and “the man who invented downsizing. . . . His life story is almost a summing up of all the ways that business can bruise society, the shareholder-first philosophy elbowing aside other important interests.”

Or, as Donald Trump once put it, “Thomas Mellon Evans was a renegade and a trailblazer, and left a legacy that few men would match in the decades to follow.”

Within months of taking over the company, Evans “slashed the number of Crane employees [including the brash firing of R. T. Crane’s great-grandson Robert B. Crane]; sold 43 branch outlets, and reduced the number of common shares outstanding by one-third.” Under his uncompromising leadership, and later that of his son Robert S. Evans, the Crane Company veered off in some exciting new directions, albeit most of them aimed at the global marketplace rather than its original U.S. clientele. At least 50 different factories, worldwide, flew the Craneco banner by 1961, with many of them now focused on modern pursuits like aerospace and broader industrial manufacturing.

Soon enough, the Chicago Works on Kedzie Avenue—once the pride of modern industrial efficiency—had become expendable. Like many of their counterparts from the 1910s and ’20s, the facilities were too enormous and outdated to affordably rehabilitate, and so they continued on a slow decline through the 1960s and 1970s, as more and more of Crane’s profitable departments were housed out of state. In 1978, the remaining machinery of the Chicago Works were auctioned off, and the plant ceased operations. By then, Crane’s national headquarters had already moved to Bridgeport, Connecticut (it’s now based in Stamford, CT).

As of 2023, nearly 180 years after R. T. Crane, Sr. poured that first mould in his little shack on Canal street, the Crane brand carries on in varied forms around the world, though probably beyond the average person’s recognition or easy understanding. The main focuses of the present conglomerate are “Aerospace & Electronics, Engineered Materials, and Process Flow Technologies”—the latter of which still concerns specialized valves and piping. While the company counts over 10,000 employees from Mexico to the Middle East to the Far East, that’s still only about the half the headcount it claimed 100 years ago, when Chicago was still home.

Sources:

“The Strike Grows Big” – Topeka State Journal, March 27, 1894

“A New Improvement Upon Old Valves” – Street Railway Journal, March 1896

“R. T. Crane, Opponent of Colleges, Is Dead” – Omaha Daily News, Jan 9, 1912

“Crane Company” – Manufacturing and Wholesale Industries of Chicago, Vol. 2, 1918

“7,000 Strike at Crane Company Without Notice” – Chicago Tribune, July 12, 1919

“Two Strikes Puzzle Even to Strikers” – Chicago Tribune, July 18, 1919

“Supports Strike Keeping Factory of Brother Idle” – Buffalo Enquirer, Aug 14, 1919

Crane Company 75th Anniversary Picnic [pamphlet], 1930

Crane Company 75th Anniversary Picnic [program], 1930

“A Trip Through Crane Town” – Valve World, July 1930

An Old Man Looks Back; Reminiscences of Forty-Seven Years, 1895-1942, in the General Offices of Crane Co., by John B. Berryman, 1943

The Crane Co. Centennial Story, 1955

Richard Teller Crane: His Life and Times, by Robert J. Casey, 1955

“Crane Head’s Career: He’s a Self Made Man” – Chicago Tribune, Aug 9, 1959

“Richard Teller Crane’s War with the Colleges” – Chicago History, Fall/Winter 1982

The White Sharks of Wall Street: Thomas Mellon Evans and the Original Corporate Raiders, by Diana B. Henriques, 2000

Chicago Made: Factory Networks in the Industrial Metropolis, by Robert Lewis, 2008

“160 Years of Crane Values” – Valve World, December 2014

I have one of the tokens in mint state that I will sell for $35 if anyone is interested. I will pay the shipping anywhere in the USA.

Best to contact me “Bosko George “ via Facebook messenger as I don’t check email very much these days.

I have one of these aged medallions and would like to donate it to someone who can relate to tis company heritage.

Contact me at my email address.

Robert Griner

Thank you so much sir for the response for my message sorry for the inconvince

How can I get back this medallion to Chicago museum ma’am/ Sir? Or into your museum?

The Crane medallions are quite common and we already have one in our museum collection. We received your many other messages and are just letting you know that it’s not a rare or valuable item. Thank you for your interest. –Made in Chicago Museum

Trying to connect William M Crane with my great grandfather. He was in the enameling trade

My greatx4 grandfather is on that coin. His daughter, Dr. Frances Crane Lillie, is who I descended from, and one of her homes in Massachusetts is still in our family’s possession. I need to purchase one of these coins. <3

I have that exact coin the Seventy Fifth Anniversary coin.

My grandfather, Ralph F. Stephen. Sr., was a manager there. He worked in Chicago at their facility in the 1930’s 40’s and into the 1950’s. I believe my father also worked there for a short time in the late 30’s.

I know of a Pasquale Bellino that worked there as an oiler in 1917 at 41st and Kedzie.

Crane Co. history on web site mentions new factory was built on 160 acres in 1912.. I know address is 4300 S. Kedzie. Where can I find the boundaries of this large site? I believe my Grandma’s house was adjacent.