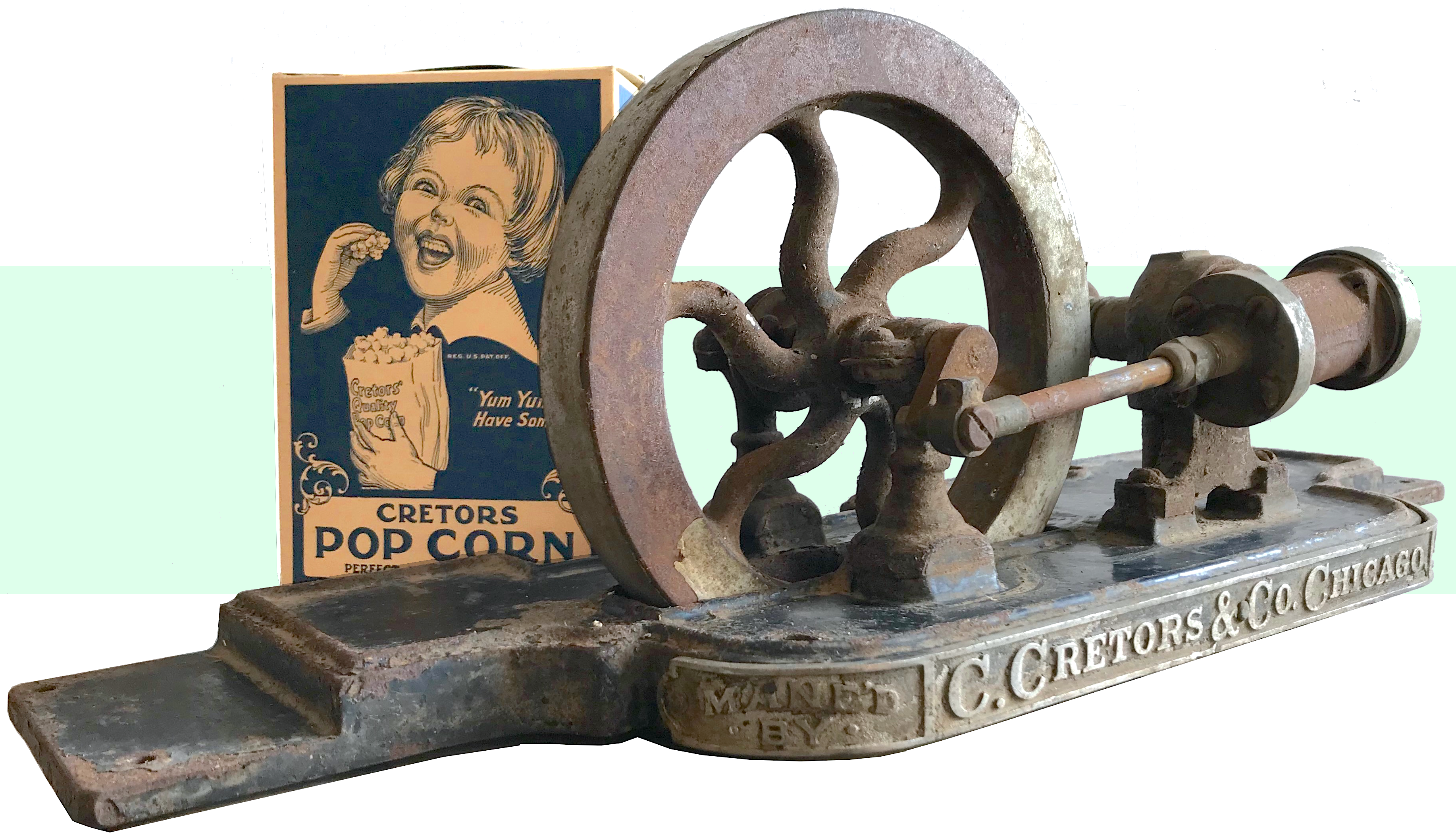

Museum Artifacts: Cretors Popcorn Wagon Steam Engine, 1908, and Pop Corn Carton, 1920s

Made By: C. Cretors & Company, 600 W. Cermak Road, Chicago, IL [East Pilsen]

“Cretors’ Pop Corn is the most pleasing of any in the world. No other novelty gives such a degree of enjoyment and satisfaction for the money. Relished by all, young or old—rich and poor alike, during all seasons of the year—it wins instant success everywhere, and practically sells itself.” —C. Cretors & Co. catalog, 1917

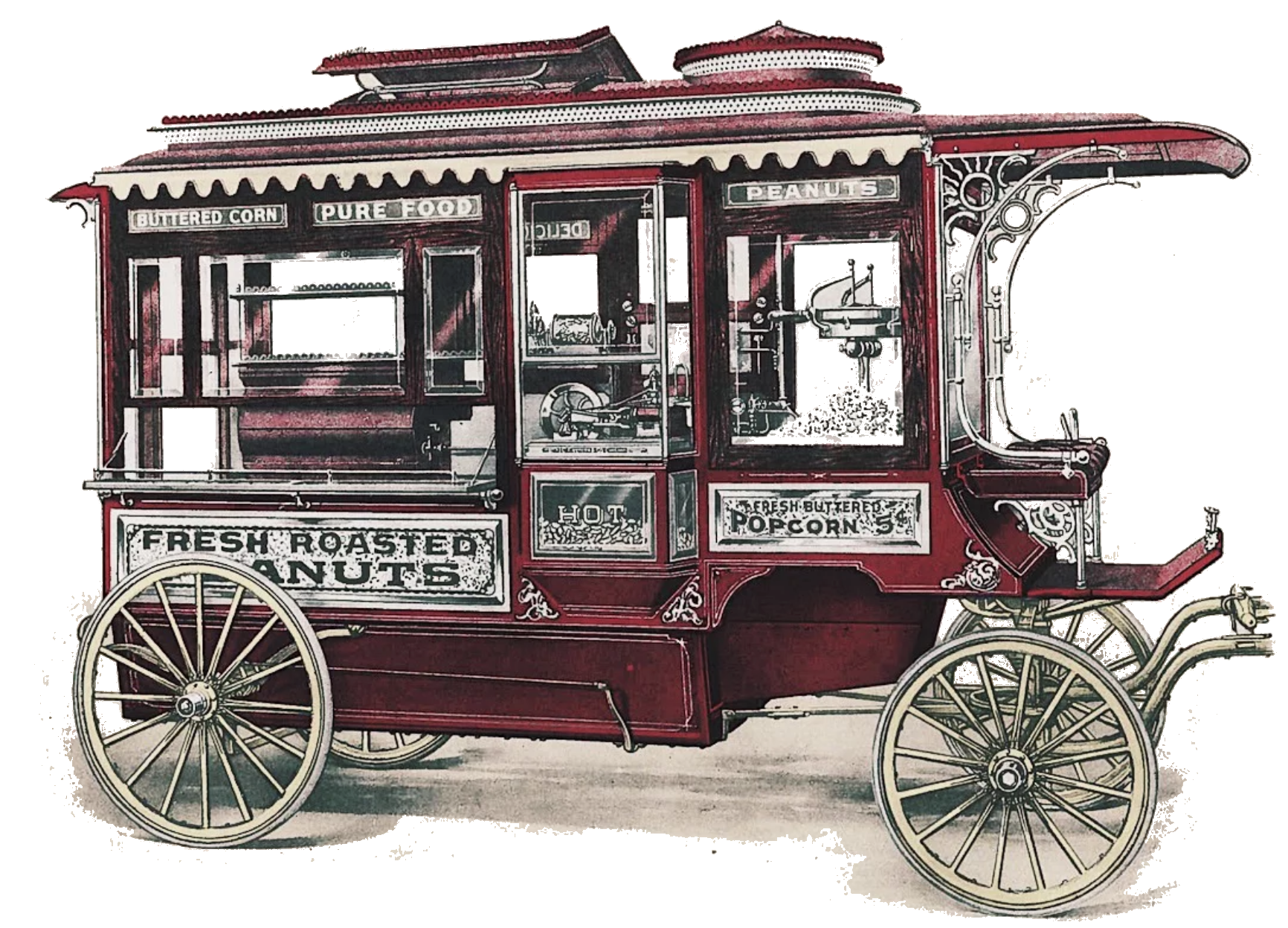

The Cretors name is as much a part of Chicago’s confectionery and concessionary history as Wrigley and Cracker Jack. Run by five generations of the same family across more than 130 years, the company is still routinely misidentified as a “maker of popcorn,” when in fact, their business has always been making the machines that make the popcorn. Cretors actually invented the modern professional popcorn popper as we know it—housing their earliest steam-powered models in ornate horse-drawn wagons that became icons in their own right; synonymous with early 20th century street-corner Americana.

The Cretors name is as much a part of Chicago’s confectionery and concessionary history as Wrigley and Cracker Jack. Run by five generations of the same family across more than 130 years, the company is still routinely misidentified as a “maker of popcorn,” when in fact, their business has always been making the machines that make the popcorn. Cretors actually invented the modern professional popcorn popper as we know it—housing their earliest steam-powered models in ornate horse-drawn wagons that became icons in their own right; synonymous with early 20th century street-corner Americana.

The rusty old Cretors steam engine in our museum collection is a tangible chunk of that history—and one with its own very specific life story. Recently discovered in a barn in Great Bend, Kansas, the engine’s origins might have remained a mystery if not for the impeccable records still kept by the Cretors family.

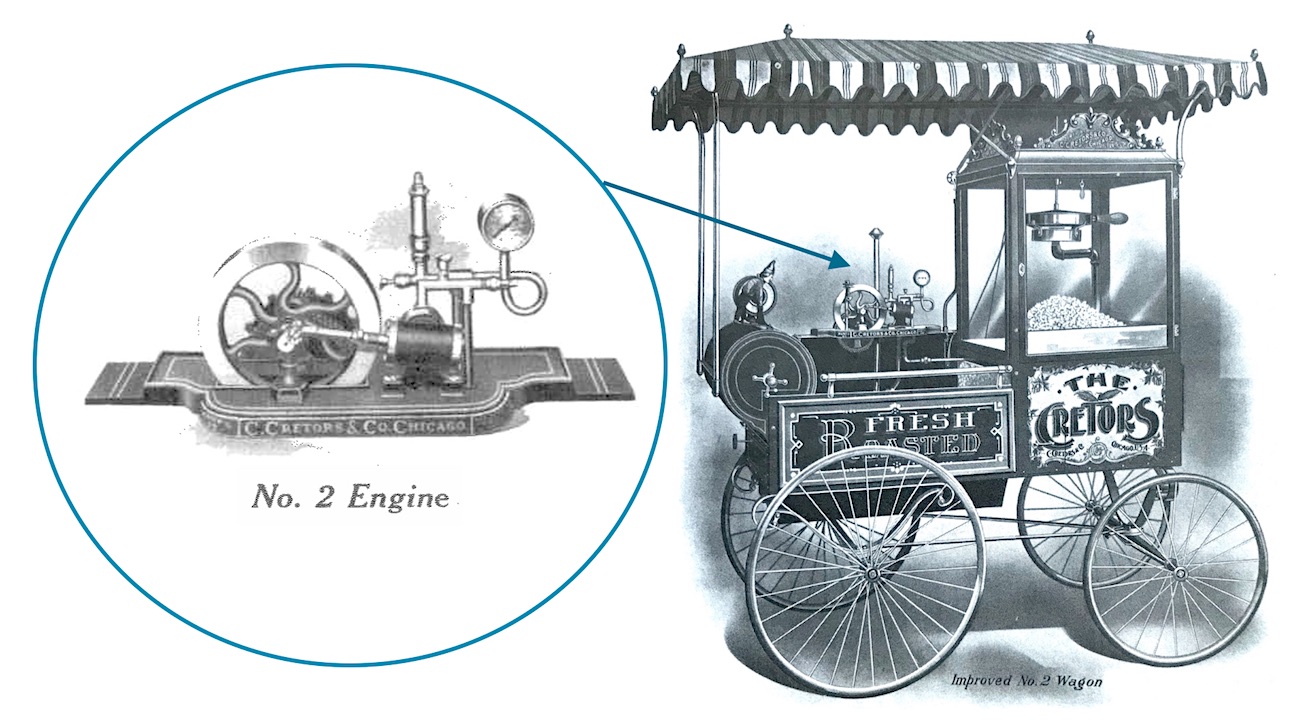

“What you have there is a No. 2 engine that was originally on an ‘Improved’ No. 2 wagon,” current company CEO Charlie Cretors (great-grandson of the founder) informed me. He then cross-checked the engine’s serial number, 5265, and pulled this amazing nugget from the company logs:

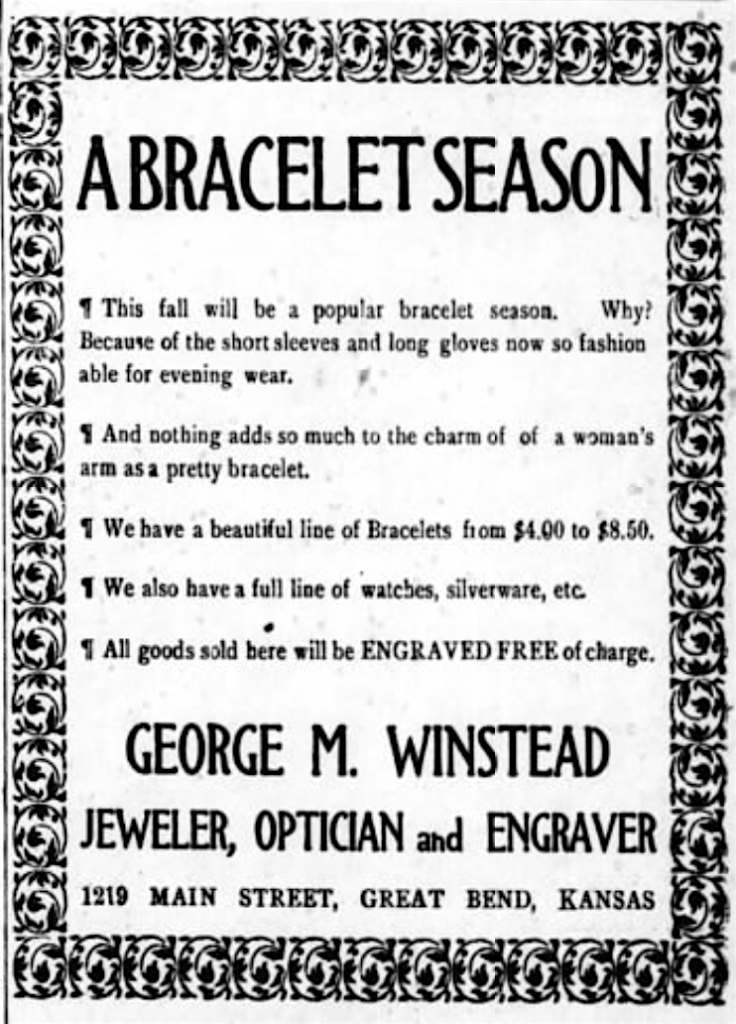

Sold To: Geo M Winstead / Place: Great Bend, KS / #2 Wagon Improved / Cost: $250.00 / Date: 3-2-1908

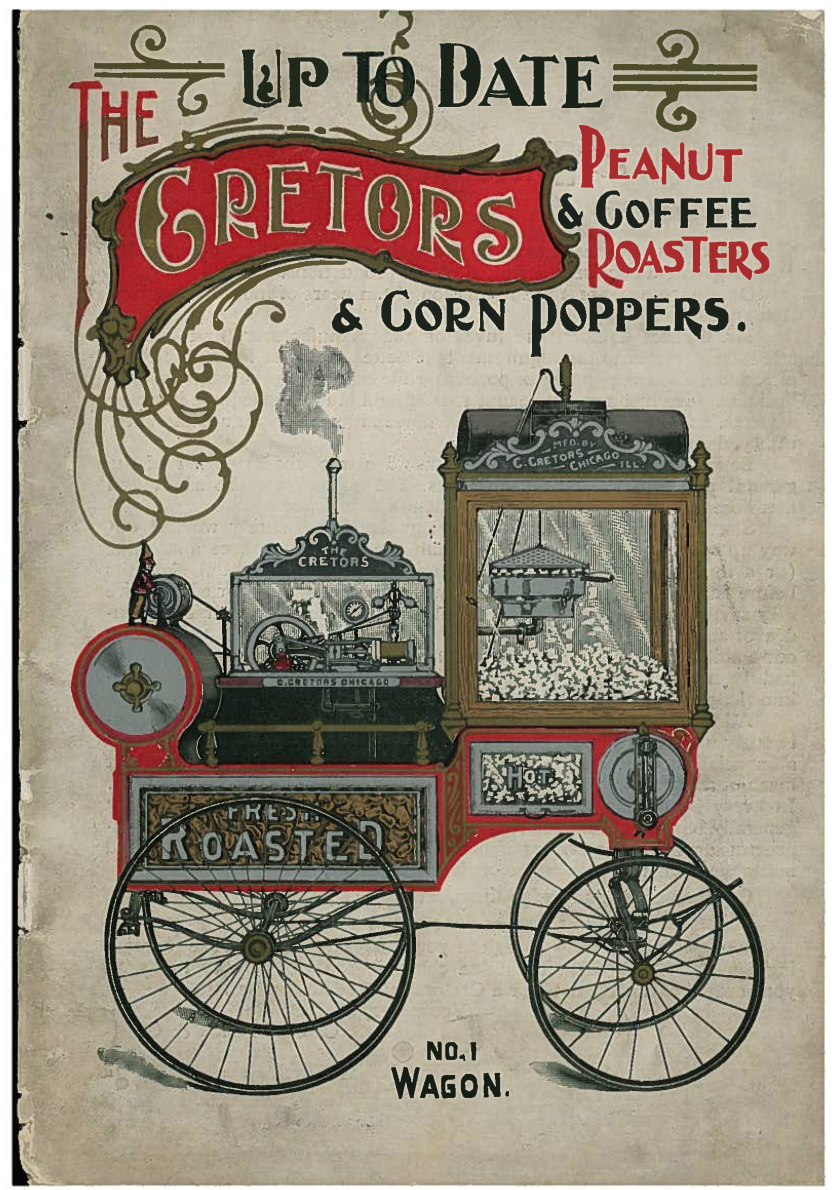

Charlie added that the images of the No. 2 Wagon and No. 2 Engine above, from the 1907 company catalog, are “probably what Mr. Winstead was looking at when he ordered his wagon 110 years ago.”

George Winstead (1885-1946), as it turns out, was a 23 year-old “jeweler and optician” in Great Bend during the time in question [note the local newspaper ad from 1906], making it highly likely that he purchased a Creators wagon to draw passersby to his shop. The No. 2 was the popular budget-priced option, but at 6-1/2 feet tall and 360 LBS, it was no small investment. Years later, carrying on an appreciation for good machinery, our old friend Mr. Winstead went on to invent a device of his own—a 1920s photo printer for Kodak—before spending his later years as the head of the Water Commission in Long Beach, California. As for how George’s steam engine ended up buried in a barn, or what became of the original wagon . . . those pointless questions will have to be left unanswered.

Winstead’s wagon was one of just over 500 built in Chicago and sold by C. Cretors & Co. in 1908, but that was a relatively hefty number for such a unique, specialty product—one still just 15 years removed from its much mythologized debut at the 1893 Columbian Exposition.

Like many of those World’s Fair Wonders, of course, the legend sometimes does the unbuttered truth a disservice.

History of C. Cretors & Co., Part I: Frontier Crackers

Charles Cretors (1852-1934) organized C. Cretors & Co. in Chicago between 1885 and 1886—long before he ever peddled his wares on the Midway at the White City. His career as a frontier confectioner, meanwhile, dates back even further and considerably farther away. An overnight success he was not.

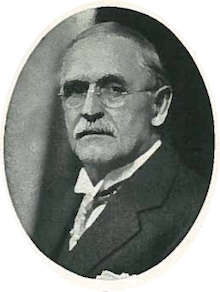

Born in Lebanon, Ohio, Cretors [pictured] was the son of a house painter and the youngest of 11 kids—all raised strictly Methodist. Opportunities for fame and fortune wouldn’t have seemed abundant, but battling with that many siblings for attention—and snacks—might have helped stir young Charles’s ambitions.

Born in Lebanon, Ohio, Cretors [pictured] was the son of a house painter and the youngest of 11 kids—all raised strictly Methodist. Opportunities for fame and fortune wouldn’t have seemed abundant, but battling with that many siblings for attention—and snacks—might have helped stir young Charles’s ambitions.

In the early 1870s, Cretors and his new bride Lucetta moved west to Fort Scott, Kansas—a rapidly growing, post-war railroad town competing with Kansas City for new settlers at the time. It hadn’t been Charles’s first choice, but when his wagon broke down outside of town, he apparently chalked it up to God’s will and settled in.

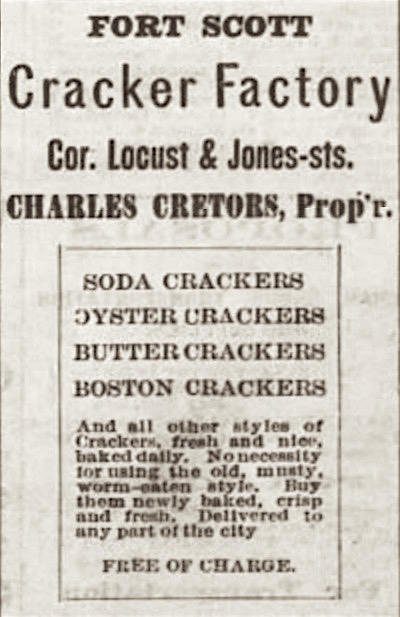

Pulling together resources from somewhere or another, Cretors opened up his first business in Ft. Scott; selling home-made crackers to hungry townsfolk. “No necessity for using the old, musty, worm-eaten style,” he announced in local newspapers ads. “Buy them newly baked, crisp and fresh, delivered to any part of the city.” From early on, the Cretors business philosophy was essentially in place—the old ways of things are musty and worm-eaten; only the new will do.

The Fort Scott cracker biz was a success, but it didn’t last long. According to some accounts, Charles—a hardcore teetotaler—shut down the factory after his business partner stumbled into work one day stinking of booze. On closer analysis, though, the tragic death of Cretors’s one-year old son Edwin in 1876 might have been a bigger motivating factor.

The Fort Scott cracker biz was a success, but it didn’t last long. According to some accounts, Charles—a hardcore teetotaler—shut down the factory after his business partner stumbled into work one day stinking of booze. On closer analysis, though, the tragic death of Cretors’s one-year old son Edwin in 1876 might have been a bigger motivating factor.

Either way, the business was abruptly sold off and Charles and Lucetta started anew, relocating to Decatur, Illinois, about 180 miles south of Chicago. There, Charles found work as a sign painter (following in his dad’s footsteps) and later as a machinist for the F. B. Tait Company. Those two gigs were crucial, not just for supporting Lucetta and their second-born son (future company president Hazael Dewitt Cretors), but for crystallizing Charles’s mechanical and artistic talents.

Soon enough, the time came to take a second crack at the snack food market.

II. “The Tosty Rosty Man”

“No doubt there are a good many people in Decatur who remember Charles Cretors,” reported the Daily Review (a local Decatur newspaper) in a 1912 article titled “Made Fortune in Corn Poppers.”

“He conducted a little confectionery store on Water street in the first room north of the old entrance to Smith’s opera house. Clint Brodess was a clerk for him there, as was his cousin, Al Cretors. . . . Charles did not get rich in the confectionery business. . . . He had no considerable amount of capital to invest in the business and for a number of years it was pretty hard to make ends meet. It is remembered that it was about 1882 that he left Decatur to go to Chicago.”

Charles Cretors was still just 30 years old when he headed north for the Second City. He was driven largely by frustration—but no so much with himself or his career choices. It was the tools of his trade—the inadequate machinery of the Victorian candy peddler—that were holding him back. And while the people in Decatur weren’t particularly interested in his solutions to the problem, he had a feeling that those progressive Chicagoans would be more amenable.

Charles Cretors was still just 30 years old when he headed north for the Second City. He was driven largely by frustration—but no so much with himself or his career choices. It was the tools of his trade—the inadequate machinery of the Victorian candy peddler—that were holding him back. And while the people in Decatur weren’t particularly interested in his solutions to the problem, he had a feeling that those progressive Chicagoans would be more amenable.

“The big idea was really a peanut roaster,” fourth-generation company CEO Charles D. Cretors explained in a recent interview. “My great-grandfather had a candy store in Decatur, Illinois. He bought a peanut roaster that he didn’t like, and thought he could do a better job. So he sold everything and moved to Chicago to build a better peanut roaster, which he proceeded to do. He had a City of Chicago peddlers license dated 1885, and that’s how we date the start of the company.”

Charles the First—if you want to address the Cretors clan as royalty—had found a new passion that inspired him even more than tasty confections. Combining his experience as a machinist, painter, and salesman, he started experimenting with designs for new steam-powered machines—applying the power source not just to peanut roasters, but coffee makers, sewing machines, lathes, and even dental equipment.

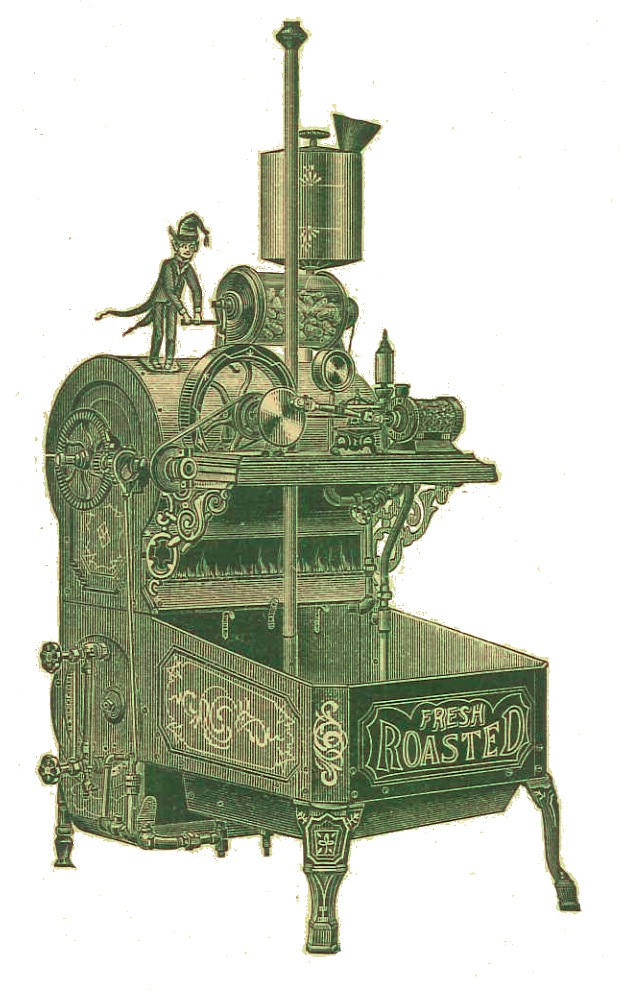

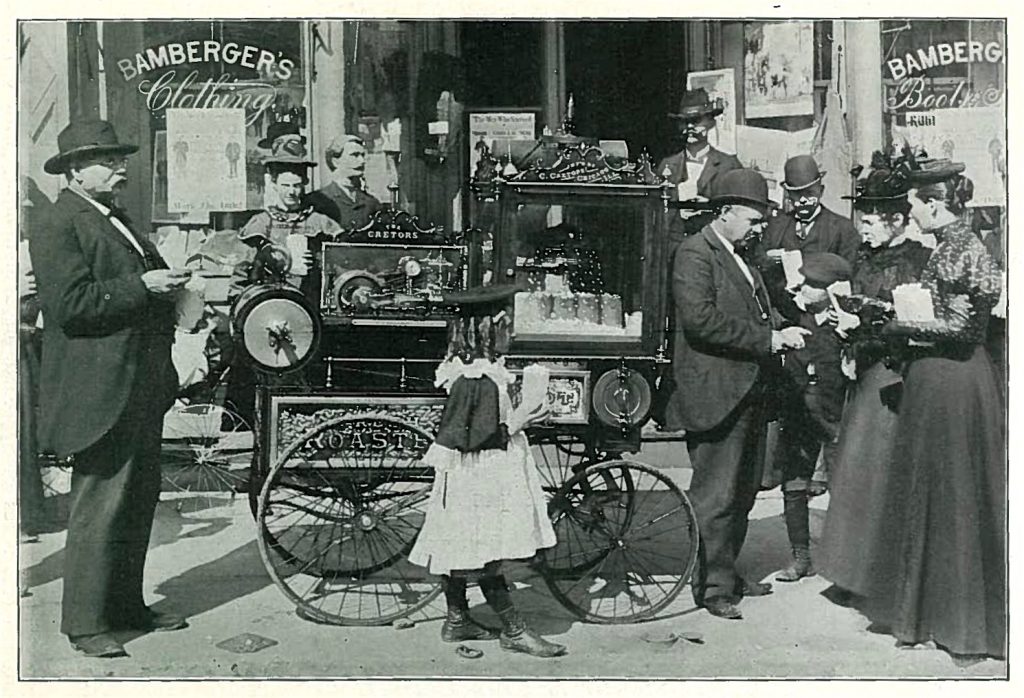

To earn money to support his mechanical endeavors, he applied for the aforementioned peddler’s license and put his first steam-powered peanut roaster to work outside his new shop at 420 State Street (insert jokes about “420” and “roasted” here). The efficiency of his machine already produced a better tasting bag of roasted peanuts than most of his competition, but in his wisdom, Charles knew he’d need more than that to attract an audience. The trick, he’d realized, was to make the machine, itself, part of the attraction—colorful artwork, puffs of steam, a glass cylinder (to see the peanuts roasting), and additional bells and whistles could all draw twice the crowd that just a decent batch of peanuts could on its own.

[The Cretors “No. 1 Wagon” in use outside a Bamberger’s Clothing store, 1890s]

[The Cretors “No. 1 Wagon” in use outside a Bamberger’s Clothing store, 1890s]

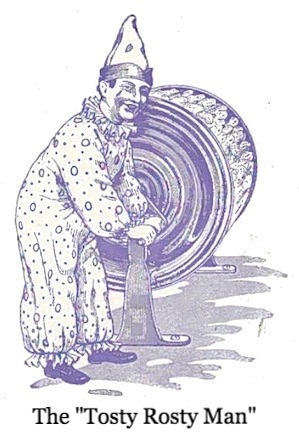

“Passersby were enthralled by the whistling pistons and whirling gears of Cretors’ contraption,” a Tribune article later recounted. “A smiling clown figurine, ‘Tosty Rosty Man,’ perched on the roaster, frantically cranking a peanut-filled squirrel cage. Cretors sold a lot of peanuts.”

By 1886, Cretors was already getting requests from other vendors to get their own steam roasters custom made. He hired his first salesman, put together his first catalog, and started applying for patents. Whether or not it had been his plan from the beginning, he was now officially in the manufacturing business.

By 1886, Cretors was already getting requests from other vendors to get their own steam roasters custom made. He hired his first salesman, put together his first catalog, and started applying for patents. Whether or not it had been his plan from the beginning, he was now officially in the manufacturing business.

“The construction of my machines I guarantee to be first-class in every particular,” he wrote in the intro to his 1887 sales book. “It will roast 12 lbs. of peanuts; 20 lbs. of coffee, or pop one quart of popcorn in less time, and with less danger of burning, than can be turned out on any other machine. . . . The entire machine is constructed with a view to safety, durability and attraction. I have had years of experience with other roasters, and for the last two years have spent time and money in experimenting, and now feel confident that I have accomplished what has long been needed—a perfect Steam Peanut and Coffee Roaster, as well as a corn popper.”

III. Top of the Pops

Charles Cretors did NOT invent popcorn, but the argument could be made that he put it on the map—presuming that popcorn was something you’d find on a map.

Before Cretors came along, popcorn was a moderately popular but consistently disappointing snack food option. Vendors who sold the stuff generally prepared it the same way people did in their own homes, by popping kernels in a wire basket over an open flame—sometimes with a hand-crank to keep things rotating. Salt and melted butter would then be poured over the popped corn—with plenty of unpopped kernels unavoidably mixed into the mess. Depending on the handful you grabbed, this proto popcorn was either going to be soggy and drippy or dry and tasteless.

Before Cretors came along, popcorn was a moderately popular but consistently disappointing snack food option. Vendors who sold the stuff generally prepared it the same way people did in their own homes, by popping kernels in a wire basket over an open flame—sometimes with a hand-crank to keep things rotating. Salt and melted butter would then be poured over the popped corn—with plenty of unpopped kernels unavoidably mixed into the mess. Depending on the handful you grabbed, this proto popcorn was either going to be soggy and drippy or dry and tasteless.

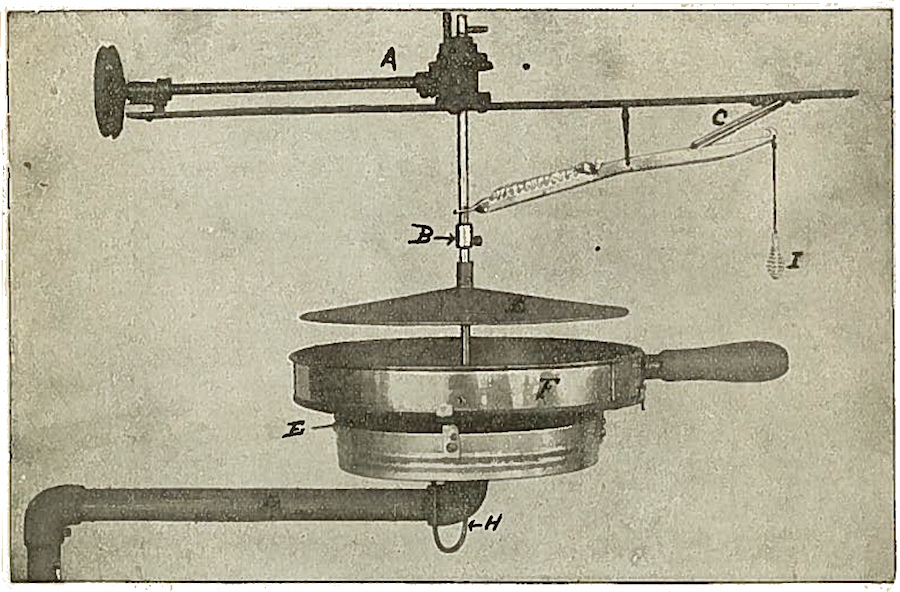

Having conquered the peanut roasting problem with flying colors, Charles Cretors increasingly put the popcorn conundrum in his sights as his business developed. He added more specialized kernel popping components to his existing peanut roasters, and by 1891, he’d hatched the “Automatic Self Buttering and Salting Corn Popper,” which became the standard on most of the machines coming out of his new factory at 11 South Union Street.

“It is the only popper which butters and salts the corn at the same time it pops it,” the 1898 Cretors catalog explained. “By our process, each grain is seasoned exactly alike, during the process of popping; thus imparting to the corn an evenness and delicacy of flavor impossible to obtain by any other method. . . . It is not greasy, and will not soil the hands or clothing of a purchaser, or sacks.”

[The Automatic Self Buttering and Salting Corn Popper, 1890s]

[The Automatic Self Buttering and Salting Corn Popper, 1890s]

Since Cretors got the patent approved on his Automatic Corn Popper in 1893, it certainly lends credence to the company lore than he chose the World’s Fair to roll out his lovely new concession wagon. Actual concrete records of any such presence are virtually impossible to come by, however (to be fair, there was a lot of competition for attention at the Fair grounds . . . like friggin’ Ferris Wheels and electricity and stuff).

Even so, it’s easy to picture Charles Cretors parking his cart somewhere along the main promenades of the Exposition’s “Great Basin,” toiling under a hot summer sun and an even hotter steam fryer, bellowing to men in top hats and ladies in bustle skirts. In the romanticized corporate version of the story, Charles—growing frustrated at stalling business—came up with a tactic he’d use liberally in the future. He started giving away bags of popcorn. “Try the new taste sensation for free!” he supposedly shouted. “Popcorn popped in butter—a revolutionary new method just patented!”

Cretors’s great-great granddaughter, Claire Cretors, told a similar story about her famous ancestor in a 2014 interview. “He put up a sign that said ‘free popcorn,’” she said, “and as soon as he saw a long line forming, he’d flip the switch and start selling it.”

Folklore or not, the good old numbers are irrefutable. In 1893, Cretors’ manufacturing shop had a team of just 10 workers. A decade later, it had swelled to more than 100, with annual wagon production increasing from a few dozen to over 500. Where once the peanut carts had come with optional popcorn components, the focus had also now shifted to building increasingly elaborate, portable popcorn carts and wagons—mostly steam powered, but soon, electrically powered, as well. Sidewalks, storefronts, parks and festivals—the Cretors popcorn cart was everywhere.

IV. Cretors of Habit

While sales were good, custom manufacturing made for tight margins. It wasn’t really until that first decade of the 20th century that Charles Cretors’s tireless efforts finally started paying off in tangible, bankable success, as his company became the largest of its kind—niche though it was—in the world. More than just being in the confectionery business or the machinery business, he’d essentially built a new business model and a whole DIY subculture to go with it—a promise of a new way to generate income, whether you were a druggist, a grocer, a pool hall owner, or just an out-of-work guy looking to make a buck.

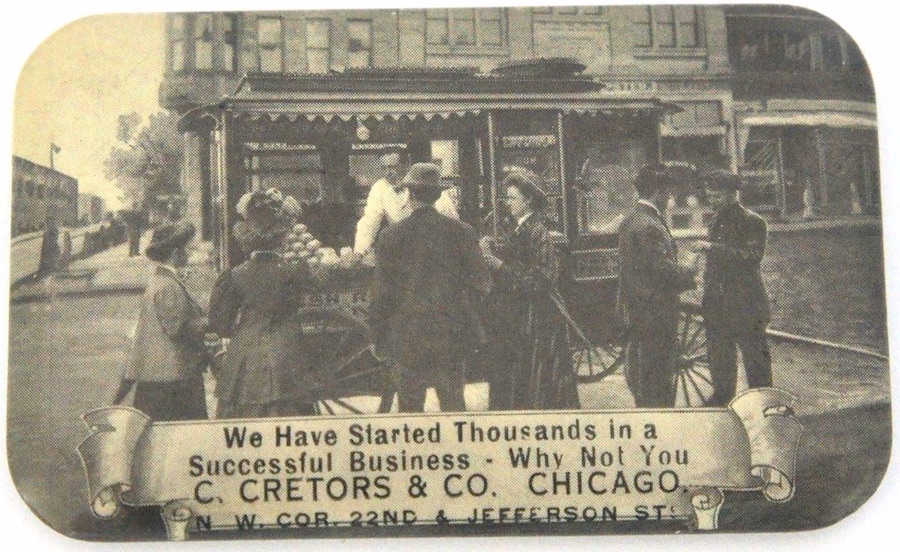

For decades, C. Cretors & Co. never paid for ads in the big trade magazines, because their increasingly prevalent carts—operated by independent agents—were free, traveling billboards. The company didn’t have to pay its own teams of salesmen, either, because their customers were—unwittingly or enthusiastically—doing that job every day.

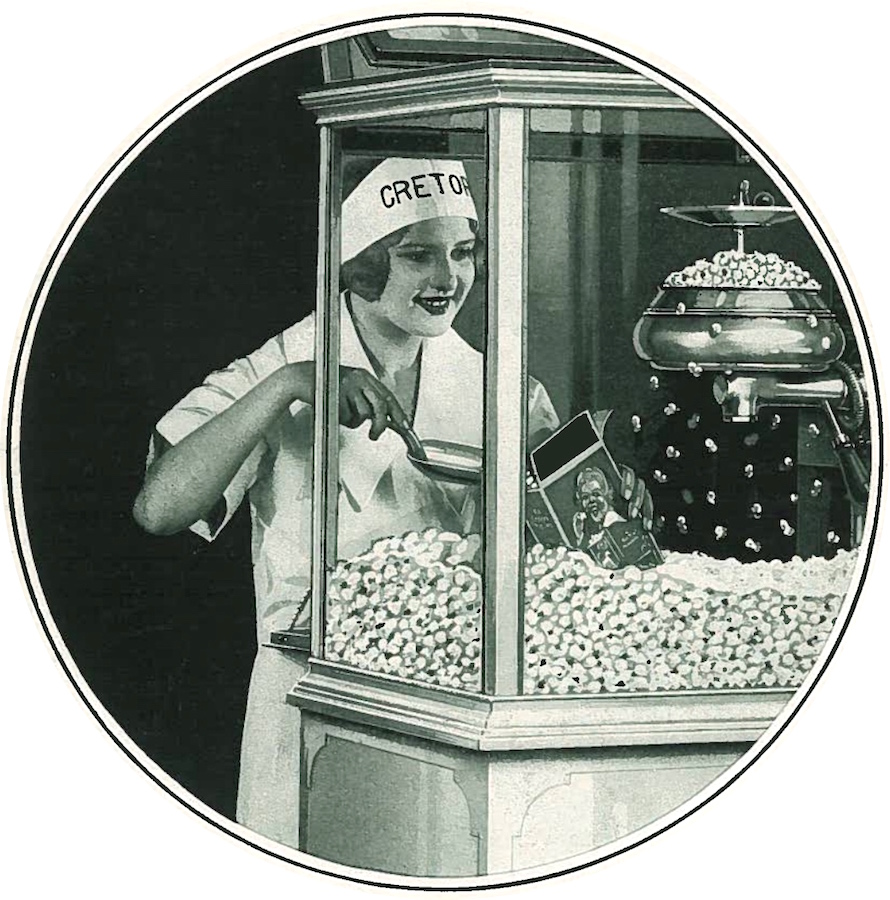

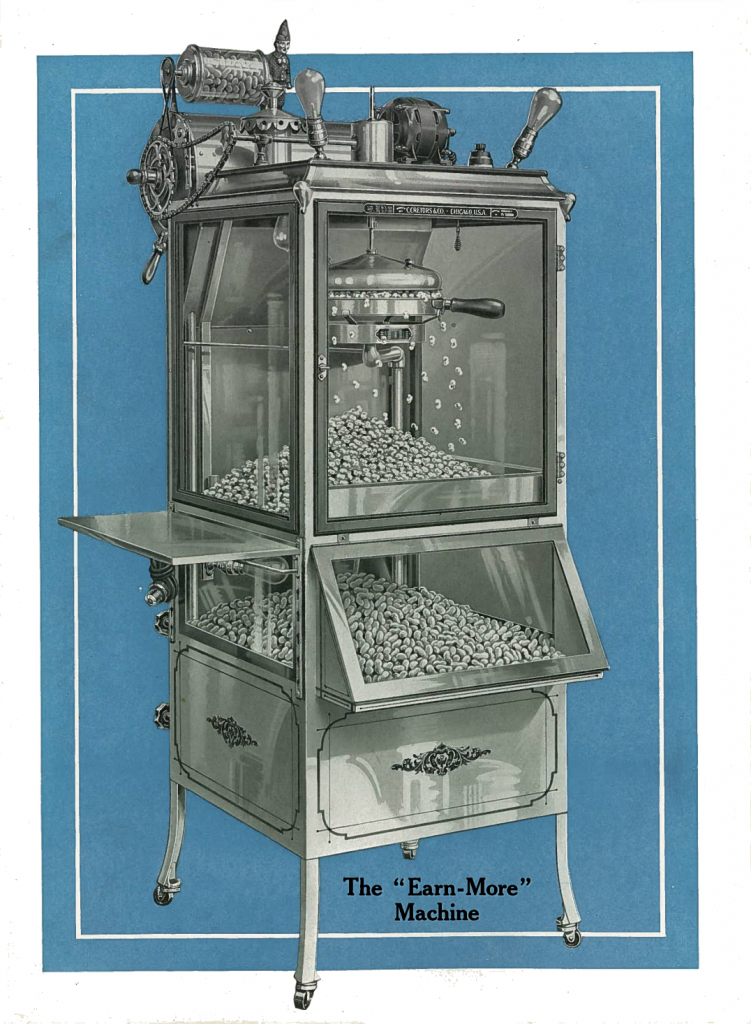

The extra overhead allowed Charles, his son H. Dewitt, and their design team to widen their ambitions when it came to new machines. Horse-drawn wagons were joined by full-scale Cretors automobiles, and as the silent film era brought foot traffic to nickelodeons and new movie palaces, big sellers like the “Earn-More Machine” gradually found a whole new clientele in cinema lobbies (some theaters initially refused to install popcorn machines, viewing them as smelly and low-class distractions, but by the 1930s, everyone needed the extra cash flow, so movie popcorn became ubiquitous).

“Pop Corn Profits For You!” cheered the 1917 Cretors catalog, which promised every vendor annual net profits from $700 to $3,500 (in today’s money, that’d be a range of $15,000 to $73,000). “The possibilities of the Pop Corn Business with ‘Cretors Equipment’ affords one of the most Attractive and Lucrative Investments in existence today. Still in its infancy, but growing with mighty strides, the industry is of such National importance that progressive merchants (or individuals) in every locality—should avail themselves of the Exceptional Profits pop corn sales produce.

“Pop Corn Profits For You!” cheered the 1917 Cretors catalog, which promised every vendor annual net profits from $700 to $3,500 (in today’s money, that’d be a range of $15,000 to $73,000). “The possibilities of the Pop Corn Business with ‘Cretors Equipment’ affords one of the most Attractive and Lucrative Investments in existence today. Still in its infancy, but growing with mighty strides, the industry is of such National importance that progressive merchants (or individuals) in every locality—should avail themselves of the Exceptional Profits pop corn sales produce.

“. . . Pop corn customers are passing your store constantly—a Cretors Machine will halt them, and the tantalizing aroma of the corn ‘popping in the butter’ will coax the nickels and dimes from their pockets in an astonishing manner.”

The profits were looking pretty astonishing for the Cretors family, too.

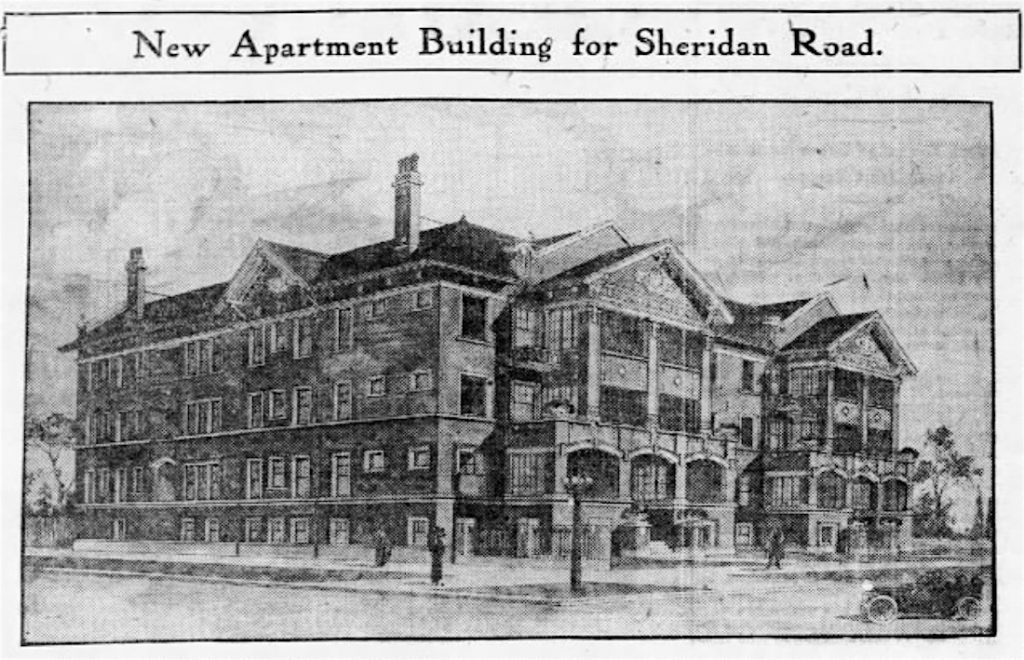

As noted, Charles’s only surviving son Hazael DeWitt Cretors (1878-1963) joined him in running the business, taking on an executive role by the 1910s. Both father and son became millionaires, and purchased matching mansions on posh Sheridan Road in Edgewater. The younger Mr. Cretors and his family lived at 5948 N. Sheridan, while Ma and Pa were conveniently nextdoor at 5956 N. Sheridan (after Charles’s death in 1934, DeWitt’s daughter Lillian and her husband Fred Fix Jr. moved into the latter address). Both homes have since been demolished.

[Along with their own homes at 5948 and 5956 N. Sheridan Rd., the Cretors family also had this apartment complex built in 1912 a little further south at the northwest corner of Sheridan and Ainslie Street. It, too, is no more.]

[Along with their own homes at 5948 and 5956 N. Sheridan Rd., the Cretors family also had this apartment complex built in 1912 a little further south at the northwest corner of Sheridan and Ainslie Street. It, too, is no more.]

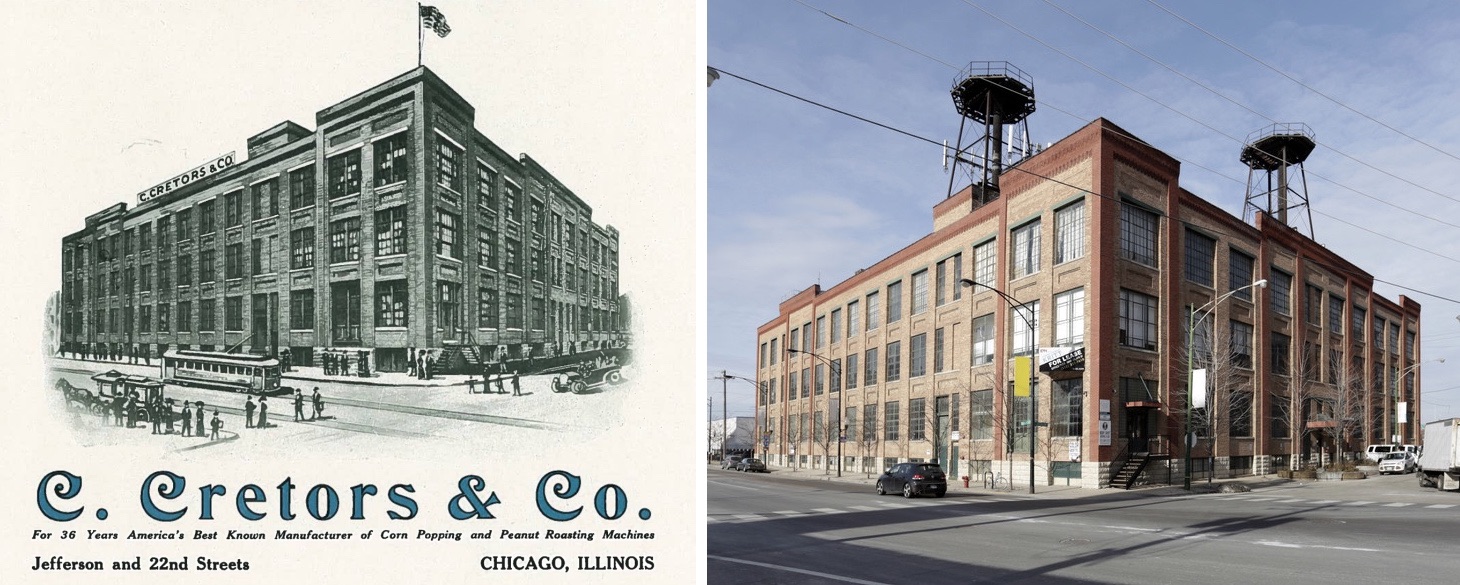

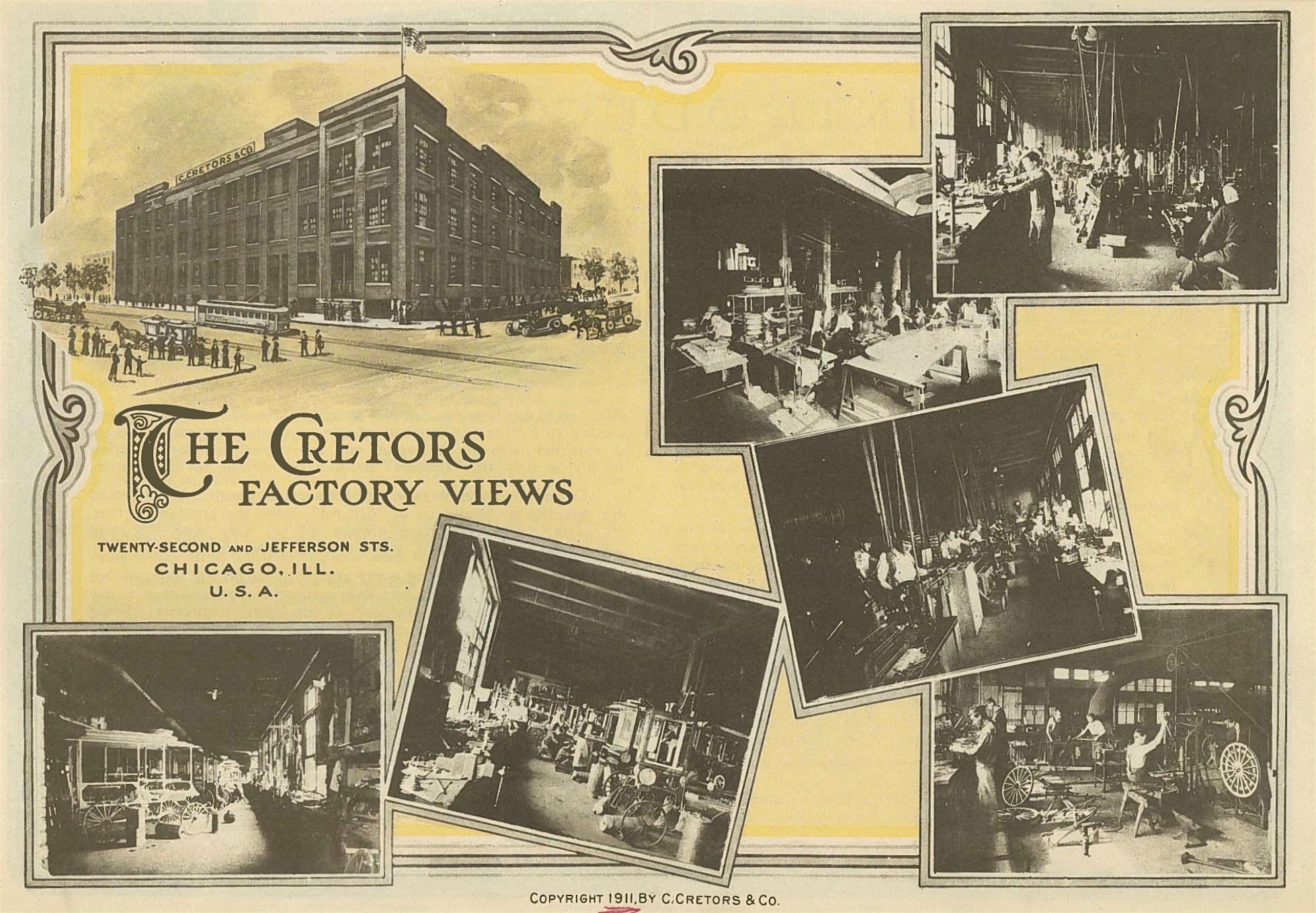

During the 1910s and 1920s, Charles and H.D. regularly made the scenic drive south down Lakeshore and west to Pilsen, to preside over their manufacturing facility at Jefferson Street and 22nd Street (now known as 600 W. Cermak Rd.). The building was shared with a major water tank manufacturer called the Wendnagel Steel Co., and it would remain Cretors’ central base of operation for roughly 70 years, with its peak workforce reaching 140 in 1917.

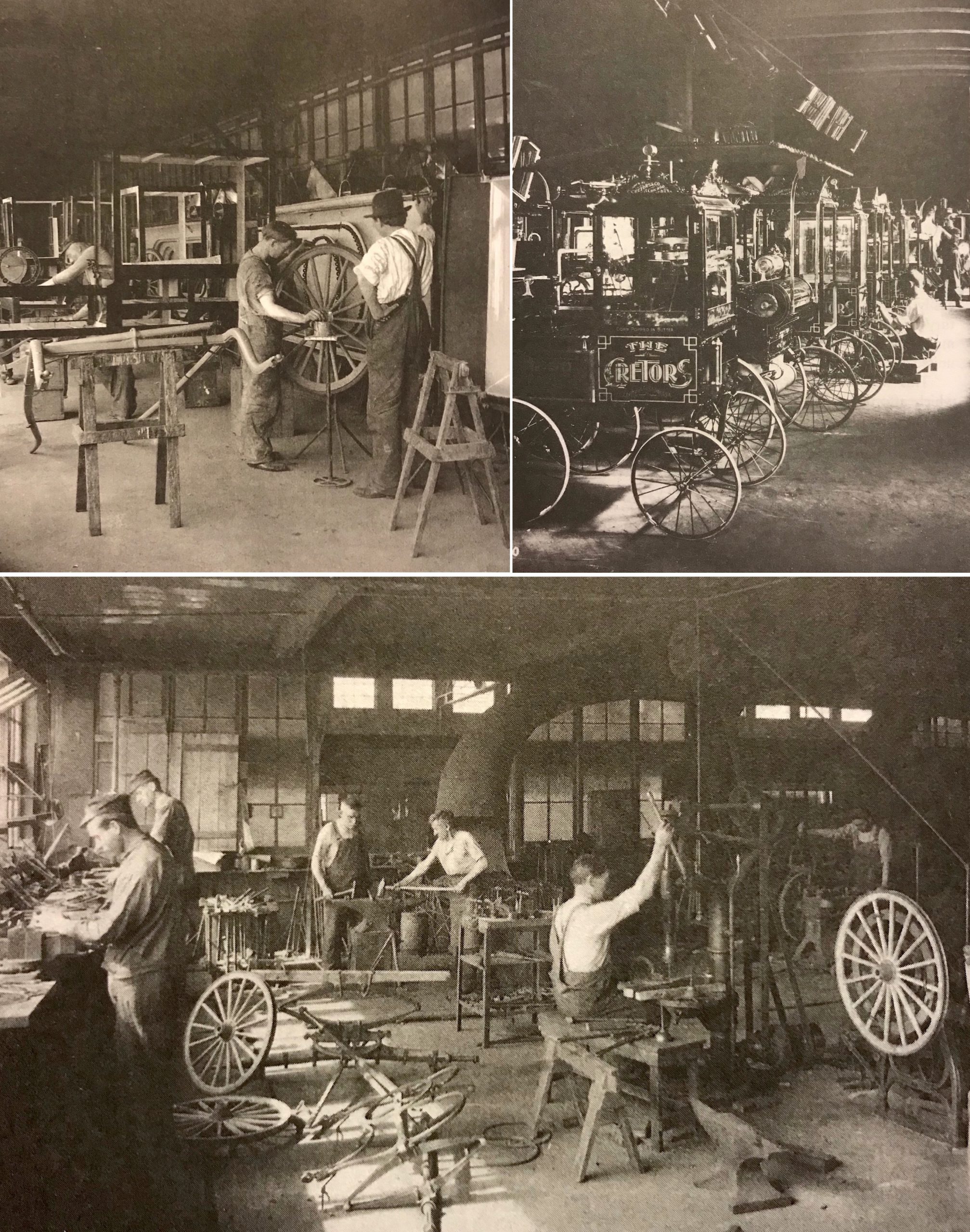

From the beginning, it was always a point of pride that virtually all manufacturing was done in-house at the Cretors plant, from the welding, framing and blacksmithing work to plating, painting, machining and assembly. This largely remained the case even as inevitable advances in technology after World War I gradually ushered out the era of the steam engines in favor of electric power—much to the chagrin of the company’s founder.

[Then and Now: The Wendnagel Building served as the Cretors factory from 1902 to 1976. Located at 22nd Street and Jefferson St., the address is now 600 W. Cermak Ave., as 22nd Street was renamed Cermak Avenue after the assassination of Mayor Anton Cermak in 1933.]

[Then and Now: The Wendnagel Building served as the Cretors factory from 1902 to 1976. Located at 22nd Street and Jefferson St., the address is now 600 W. Cermak Ave., as 22nd Street was renamed Cermak Avenue after the assassination of Mayor Anton Cermak in 1933.]

V. Inside “The Shop”

It was around the beginning of the transition from steam to electric, in the late 1910s, that Charles’s grandson Charles J. Cretors—generation No. 3—started joining his dad and “Gramp” on those drives to the family factory. Young C.J. was just a little kid at the time, but he spoke of the experience vividly more than 60 years later, in the introduction to a 1985 book about the business.

“My first recollection of C. Cretors & Co., or ‘The Shop,’ as it was referred to in the family, was of a large room filled with machinery and many, many belts,” he wrote. “There were horizontal belts and vertical belts, wide belts and thin belts, slow belts and fast belts, all going up and down from each machine and across the ceiling and all flapping and hissing away in a most purposeful manner. It was, of course, the Machine Shop, Harry’s domain, where the beautiful little steam engines were born.

[Workers at the Cretors factory, c. 1910s]

[Workers at the Cretors factory, c. 1910s]

“‘Harry’ was Harry Sexauer, a small, wiry man with intense, slate-blue eyes and hands that caressed metal as though it were alive. He took personal pride in every single engine and, so far as I know, never built a faulty one. Over against one wall was an area where engines were tested. A live steam line was brought up from the big boiler in the basement, and the little engines were hooked up to it and allowed to run until Harry was satisfied.

“I never tired of standing there watching those little engines hum along, the brightly polished fly wheels with their red spokes, the copper-covered steam cylinder, the whirling fly-ball governor, the brass crosshead flashing back and forth, all working together so smoothly. What a fascinating way to generate power!”

Like the elder Charles Cretors, Harry Sexauer wasn’t keen on leaving the steam age behind. He had replaced the company’s original engine builder, C. F. Dunbar, sometime around the turn of the century, and ended up sticking around the factory another 50 years, reluctantly adapting to change. The small but powerful oscillating steam engines he built in his early years were quite simple and efficient in design, but highly impressive in action, creating not only the functional heart of the Cretors machine, but it’s visual “show.”

Like the elder Charles Cretors, Harry Sexauer wasn’t keen on leaving the steam age behind. He had replaced the company’s original engine builder, C. F. Dunbar, sometime around the turn of the century, and ended up sticking around the factory another 50 years, reluctantly adapting to change. The small but powerful oscillating steam engines he built in his early years were quite simple and efficient in design, but highly impressive in action, creating not only the functional heart of the Cretors machine, but it’s visual “show.”

“In purchasing a machine, you should pay particular attention to the ‘Motive Power,’ a 1911 company catalog instructed, “as it is a very valuable feature. . . . A working engine is a source of constant attraction of which the public will not tire, commanding the attention and admiration of every passerby. . . . No engine or device equals our engine in this important respect.”

[Above: A restored version of the No. 2 Oscillating Steam Engine, doing its thing]

[Below: Our museum’s No. 2 engine, currently in retirement]

Cretors catalogs hardly went humble when the quieter (if less theatrical) electric engines became the norm in the 1920s. In the 1924 edition, for example, an informative feature titled “How Cretors Machines are Made” laid out the category-by-category superiority of the product line.

“How Cretors Machines Are Built” – Excerpt Below from 1924 Catalog

‘Quality first.’ That is the policy governing the manufacture of every machine we build.

Nothing but the best material is used. We are not merely ‘assemblers’ but build our machines complete from the raw materials. Our workmen are paid on a day-rate basis so that we avoid the hurried, careless work so often resulting from ‘piecework.’ Most of our men stay with us year after year.

All Steel Frame Construction

The frame or body of every Cretors machine is built of angle, plate and sheet steel throughout, thus assuring maximum strength and durability. Our experience has demonstrated the all-steel frame, among other advantages, to be fireproof, stronger, lighter, more durable, more secure in joints, etc., hence we have adopted it as standard equipment.

Mechanically Perfect

All parts are machined in our own shops, fitted and assembled by mechanics who are experts in this particular class of work. In addition, each finished machine is thoroughly tested in every possible way by trusted inspectors before it leaves our factory.

Beautifully Finished

All Cretors machines are beautifully finished. Only the very best paints and varnishes are used, and sundry metals are heavily nickel plated. Cretors machines will harmonize with the finest and most expensive store fixtures.

Easy to Operate

There is no elaborate and complicated mechanism to contend with in the operation of Cretors machines. All parts are strongly and simply constructed so that anyone of average intelligence can perform every operation incidental to operating the machine, popping corn and roasting peanuts.

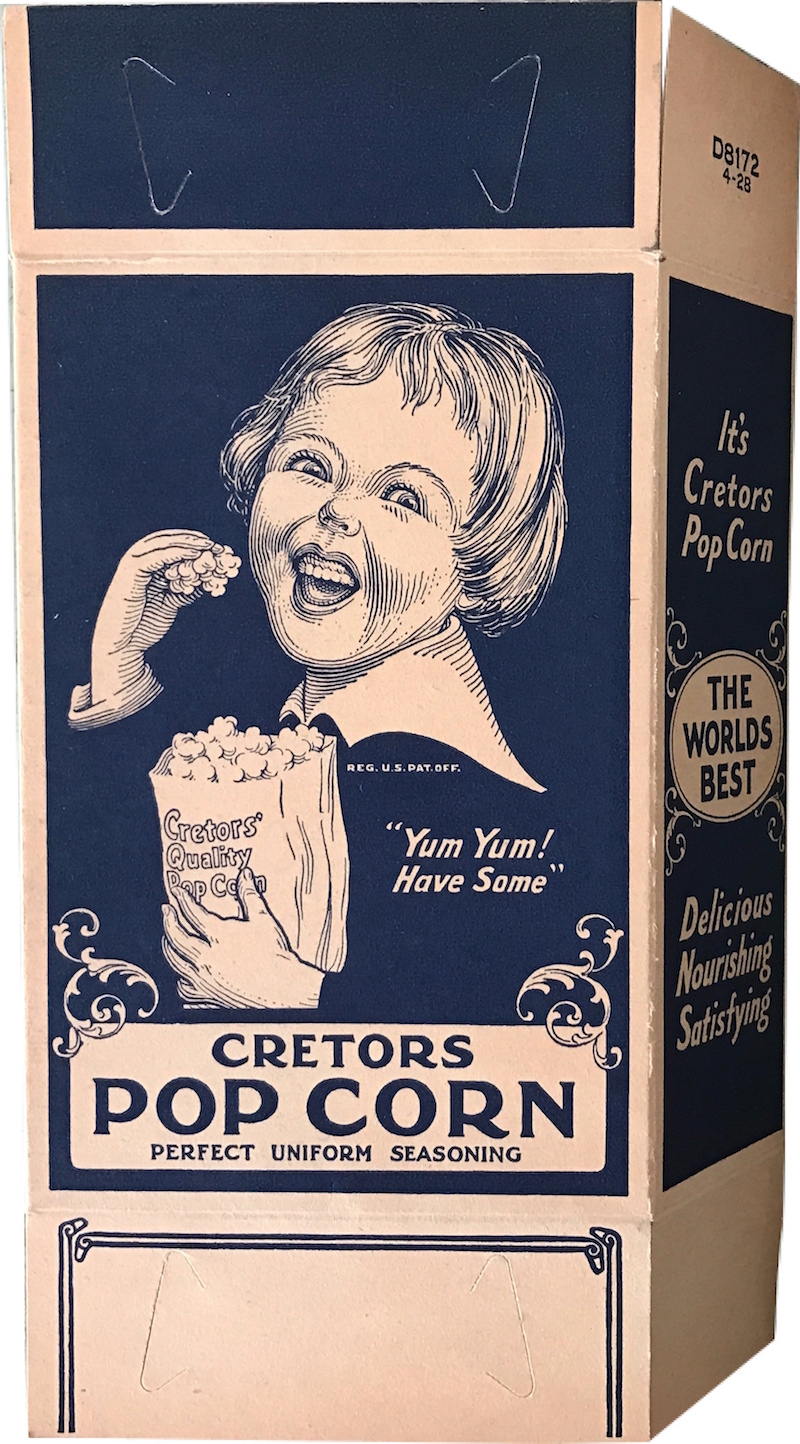

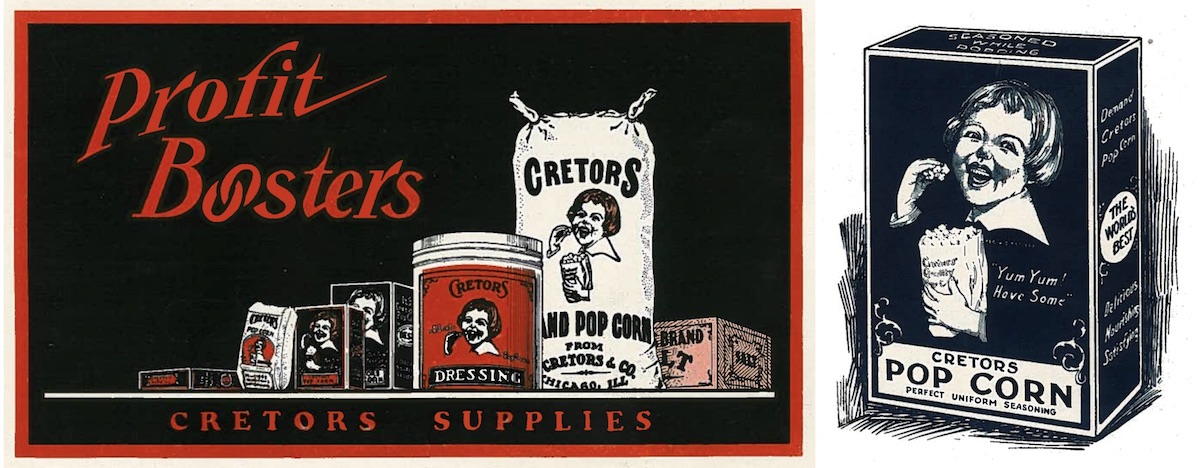

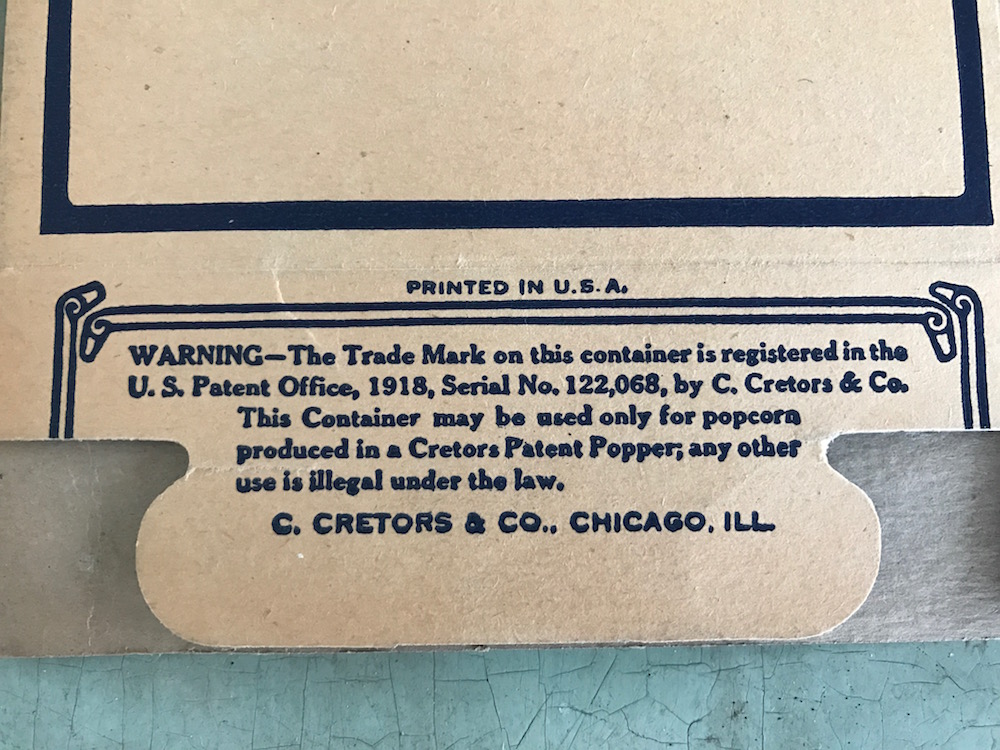

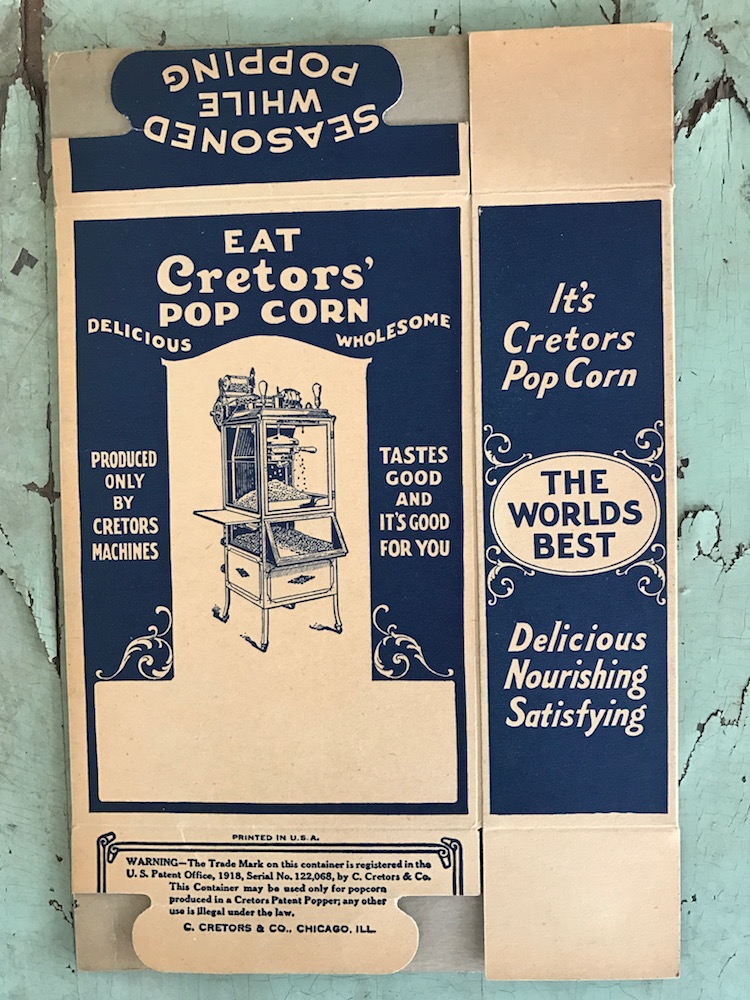

The attention to detail didn’t stop with the machines. By the 1920s, even the little bags used to serve the popcorn itself were refined and updated. New “take home” cartons were introduced, too, of which the artifact in our museum collection [pictured] is an example. Both of these container types featured Cretors’ recognizable “Booster Boy” logo—a mischievous looking kid with a pageboy haircut, gobbling on popcorn. The accompanying slogan, “Yum Yum! Have Some” was pretty succinct and to the point.

The attention to detail didn’t stop with the machines. By the 1920s, even the little bags used to serve the popcorn itself were refined and updated. New “take home” cartons were introduced, too, of which the artifact in our museum collection [pictured] is an example. Both of these container types featured Cretors’ recognizable “Booster Boy” logo—a mischievous looking kid with a pageboy haircut, gobbling on popcorn. The accompanying slogan, “Yum Yum! Have Some” was pretty succinct and to the point.

“It is surprising how quickly particular people insist upon receiving corn served in our ‘Booster Boy’ Bags and Cartons,” exclaimed a 1928 listing. “[These containers] distinguish Cretors Pop Corn from all other kinds. When you purchase a Cretors Machine, we grant you the privilege of using these popular copyrighted containers—we send you a quantity free with your machine—and supply your additional requirements at reasonable cost.”

VI. Modernizing

“Booster Boy” was never more needed than in the 1930s, as the popcorn business—and C. Cretors & Co.—faced some tectonic shifts. The Great Depression was crushing manufacturing companies all over the city, and there were no guarantees at the Cermak Avenue plant that Cretors could carry on as it once had. On one hand, many shop owners were far less willing to invest in a popcorn machine when every last cent had to be gripped tight. At the same time, though, men who were recently cast out of work were increasingly desperate for a new means of income. Add into this mix the explosion of “talkie” cinema and the increased willingness of theater owners to install Cretors machines by their concession stands . . . it was hard to predict which trends would win out.

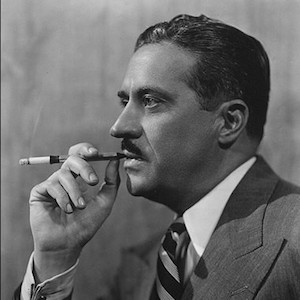

Charles Cretors I wouldn’t live to see the full drama play out. The company founder and Chairman died in 1934 at the age of 82. That same year, his aforementioned and now fully grownup grandson, Charles J. Cretors (1911-2006), joined the business, learning the ropes from H. DeWitt, who had stayed on as president. [pictured: Charles J. Cretors, generation No. 3]

Charles Cretors I wouldn’t live to see the full drama play out. The company founder and Chairman died in 1934 at the age of 82. That same year, his aforementioned and now fully grownup grandson, Charles J. Cretors (1911-2006), joined the business, learning the ropes from H. DeWitt, who had stayed on as president. [pictured: Charles J. Cretors, generation No. 3]

Together, H.D. and C.J. watched as the cinema market opened up and essentially saved the business during the darkest hours of the Depression. It wasn’t dumb luck either. A concerted effort was made to target this growing clientele by producing more stand-alone, monolithic machines well equipped for the venues. New models included the Majestic, the Hollywood, the Opportunity, and the Giant 41. A pile of new patents were collected, too, as the company’s research wing never stopped following Charles I’s original philosophy: old stuff is worm-eaten, new stuff wins the day.

[The “Opportunity” model Cretors machine, 1934]

[The “Opportunity” model Cretors machine, 1934]

Progress ground to a halt during World War II, of course, and as one of his early tests as the man in charge, Charles J. Cretors shifted the factory over to government work, building aircraft oil line fittings and mechanical radio components for the U.S. military.

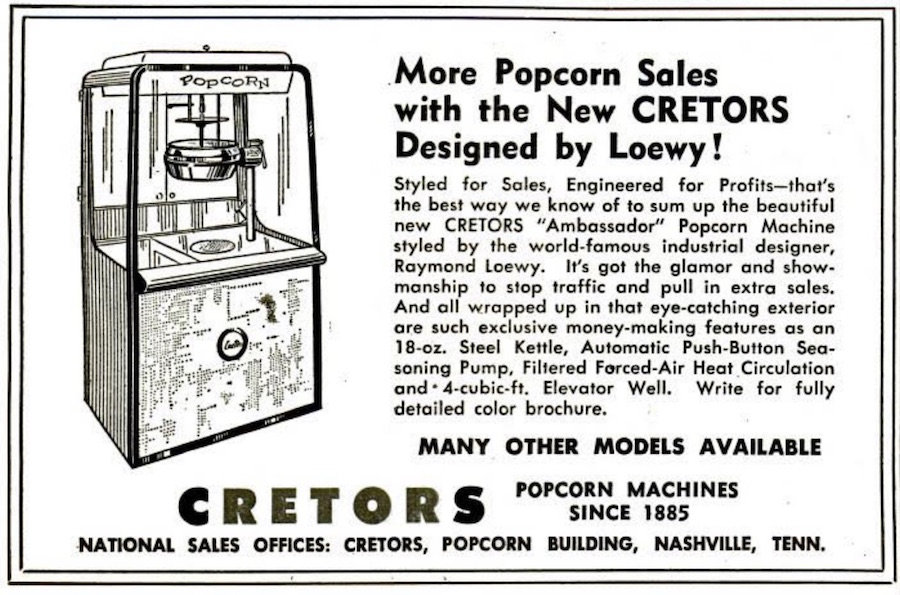

The peacetime 1950s posed another unpredictable line-up of challenges. Not only was there more competition in the popcorn machine market, but the rise of television was threatening the old movie houses and turning popcorn into an antiquated snack choice. Cretors needed a modern facelift, and C. J. turned to industrial designer Raymond Loewy to lead the effort.

The French-born Loewy [pictured] was already something of a legend in what came to be known as Art Deco design. He had designed refrigerators for Sears-Roebuck, razors for Gillette, toasters for Sunbeam, passenger locomotives for the Pennsylvania Railroad, iconic automobiles for Lincoln and Studebaker, and fountain machines for Coca Cola. He had a bunch of famous logos and packages to his credit, too—Shell, TWA, Lucky Strike, Nabisco, International Harvester. By hiring Loewy to work his magic on Cretors’ machines, C. J. Cretors hoped to carefully separate the company from its ties to 19th century sidewalk vendors, and bring it warp-speeding into the modern ‘50s.

The French-born Loewy [pictured] was already something of a legend in what came to be known as Art Deco design. He had designed refrigerators for Sears-Roebuck, razors for Gillette, toasters for Sunbeam, passenger locomotives for the Pennsylvania Railroad, iconic automobiles for Lincoln and Studebaker, and fountain machines for Coca Cola. He had a bunch of famous logos and packages to his credit, too—Shell, TWA, Lucky Strike, Nabisco, International Harvester. By hiring Loewy to work his magic on Cretors’ machines, C. J. Cretors hoped to carefully separate the company from its ties to 19th century sidewalk vendors, and bring it warp-speeding into the modern ‘50s.

Loewy’s work on the new Hollywood and Ambassador models seemed to achieve the desired goal, taking on a streamlined, space-age look not unlike the jukeboxes of the same period. Unlike those jukeboxes, however, the professional popcorn machine wouldn’t be made obsolete by advancing technology. Sure, the microwave popcorn revolution was coming, and Orville Redenbacher was ready to pounce. But the explosion of the home popcorn market didn’t actually doom the popcorn machine industry any more than TV had killed the movies. Theaters, sporting events, shopping centers . . . these things were still essential to public life, and they all had popcorn machines now built right into their foundations.

[1955 advertisement in Billboard magazine for the Loewy designed Ambassador popcorn machine. By the 1950s, the company had established a new primary sales office in Nashville, but manufacturing remained at the Chicago plant]

[1955 advertisement in Billboard magazine for the Loewy designed Ambassador popcorn machine. By the 1950s, the company had established a new primary sales office in Nashville, but manufacturing remained at the Chicago plant]

VII. All In the Family

By the late 1960s, Charles J.’s young sons Charles D. (Charlie) Cretors and George H. (Henry) Cretors—generation No. 4—joined the business. Charlie, who had a degree in mechanical engineering (great-grandpa would have been proud) helped simplify the machine designs for the tastes and materials of the 1970s and ‘80s, and also led the way in creating the first continuous hot air popcorn machine. Meanwhile, Henry Cretors took over leadership of the company’s wholesale distribution wing, known as the Iroquois Popcorn Co.

C. Cretors & Co. was, by now, a giant international corporation with major clients around the world and a dominant hold on the American movie theater market. And yet, by its 100th anniversary in 1985, it was also that rarest of creatures—the pioneering family business that (a) stayed relevant, and (b) stayed in the family. The only big change was the factory, which had relocated by the mid ‘80s to 3243 N. California Avenue in Avondale.

[From left: Rufus Harris (Head of Sales), G. Henry Cretors, Charles J. Cretors, and Charlie D. Cretors at a trade show with the “Flo-Thru” machine in 1969. From Cretors & Co. Facebook page]

[From left: Rufus Harris (Head of Sales), G. Henry Cretors, Charles J. Cretors, and Charlie D. Cretors at a trade show with the “Flo-Thru” machine in 1969. From Cretors & Co. Facebook page]

Things did finally reach a bit of the fork in the road in 1991, when G. Henry Cretors elected to sell his stock to his brother and create his own company, Cornfields, Inc. That business, which focuses on selling pre-made popcorn and other upscale snacks (including Skinny Sticks), found plenty of success of its own, employing upwards of 300 workers in suburban Waukegan. Even after George Henry’s death in 2004, his wife Phyllis Cretors and daughter Claire Cretors took the company to new heights, bringing new organic snacks to the commercial market, including ready-to-eat popcorn under the “G.H. Cretors” brand name. So, if you did think Cretors sold popcorn in bags at the grocery store, you’re right—it’s just not C. Cretors & Co.(incidentally, Cornfields Inc. was sold to Eagle Family Food Groups in 2016).

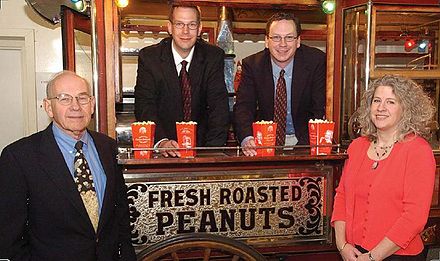

The original Cretors manufacturing business carries on today at a new facility in suburban Wood Dale, Illinois, about 30 miles northwest of Chicago (the California Avenue factory was demolished in 2016). Fifth generation company president Andrew Cretors joined the fold in the late 1990s, and took over the company presidency in 2004, when his father, Charles D., moved into the CEO role. Incredibly, C. Cretors & Co. is still owned and operated by people named Cretors, 130 years after a painter in Decatur had an idea and ran with it.

[Five generations in. From left: Charlie D. Cretors, Bud Cretors, Andrew Cretors and Beth Cretors at the current company HQ in Wood Dale, IL]

[Five generations in. From left: Charlie D. Cretors, Bud Cretors, Andrew Cretors and Beth Cretors at the current company HQ in Wood Dale, IL]

[Above and Below: Exterior and Interior of the former Cretors plant at 600-620 W. Cermak Ave,]

Sources:

Cretors.com – Company History & Archives

CornfieldsInc.com – Company History

C. Cretors & Co. -125 YEARS, by the Cretors Family with Richard Hagle, 2013

“Made Fortune in Corn Poppers” – The Daily Review (Decatur, IL), May 26, 1912

“The Lure of Fresh, Hot Popcorn” – by Jennifer Singleton, The Carriage Journal: Vol 48, No 5, October 2010

“A Great Idea Pops Up in Chicago” – Chicago Tribune, October 6, 1992

Popped Culture: A Social History of Popcorn in America, by Andrew F. Smith

Billboard, Feb 19, 1955

“C. Cretors and Company” – The Peanut King

“Charles D. Cretors” – Michigan Tech University

“Waukegan Snack Company Relies on an Organic Touch” – Chicago Tribune, August 14, 2014

“Cornfields Has Been Acquired by Eagle Family Food Groups” – William Blair, October 20, 2016

[Cretor’s popcorn machine currently in the lobby of the Chicago Theatre]

[Cretor’s popcorn machine currently in the lobby of the Chicago Theatre]

Archived Reader Comments:

“Mr. Clayman This is a wonderful article. My first question is do you have a copy of our history book? You have some facts that I was not aware of. I have never seen the advertisement for the Fort Scott Cracker factory. My father said the problem in Fort Scott was that the water was and and only the baker knew how to make the crackers bake properly. He was a drinker and Charles fired him which put him out of business. Dad did not say he was his partner but that may well have been the case.

Dad (C. J.) said that when Charles was heading back East they were “robbed by Highwaymen” near Decatur. The Peanut Roaster that was not very good; came from Oskaloosa, Iowa. I have Bartholomew catalogs and I will check to see if any are from Iowa. Most of the catalogs have a Peoria IL address. . . . I did not know that Charles worked in a Machine shop in Decatur.

You have a lot of interesting newspaper articles. Have you ever seen the Sept 27th Tribune article titled ‘Fortune Works in Popcorn?’ It is worth a read. . . . Today the Flo Thru (Industrial Machinery) is about equal in annual sales to the commercial(Movie Theater and concession) business). 50% of our sales are export and we can say we have machinery on all continents and more than 50 countries.

If you would like to see our museum (Really just a collection) of vintage machines you are welcome. Our oldest dates from 1895.

I am sorry I did not see this sooner. My daughter, Beth, just sent it to me last night.”

–Charles D. Cretors, 2018

“Thank you, Mr. Cretors, for the kind words and additional information. I will add in some of the extra details you mentioned. I don’t have a copy of the official company history book, so most of the research came from old archived newspaper articles, ancestry.com, and your own website (all the sources are listed at the end of the article). Early profiles about Charles Cretors in 1912 and 1914 issues of the local Dectaur newspaper provided some of the unique details, including Charles’ brief time working in a machine shop. If you have additional things to add or corrections, let me know. Always happy to update and refine the history! If you have a few more photos of the old factory and workers that you’d be willing to share, that’d be great, too. Images of workers are hard to come by, and they’re very important to the stories I am trying to tell. Cheers!” —Made in Chicago Museum

I have the Tost Rosty Man. My father’s granddaddy gave it to him. A gentleman in Belton, SC that owned a store gave it to my Dad’s granddad. I’m 57 and have admired it my whole life. I just now have found out it’s History!

I would like to upgrade the two cart ,s that I have. They are from the c-1917 and 1900s One of them is a EARN MORE.

The Museum of Collinsville History has received a donation of C.Cretor’s & Co. Chicago,Ill., Peanut Machine, model S.P.R.S T. R., No. 40410. “Hot Peanuts” is on front. It was used in Collinsville, AL, in 1950s and maybe 1960s. Would appreciate any information you can provide. Thank you.

We purchased an electric Cretors countertop size popper with hopper for popcorn on top. I cannot find any information on this model, any information would be appreciated.

Hello Charles. I know you don’t remember me, but my father was SolT. Jacobson, of Krispy Kist Korn Machine Co., Likely last saw you or your dad was at one of the Popcorn Association meetings in the late 40’s, early 50’s!

I just want to thank you again for taking over our company after my father passed as did his successor, my BIL, Bob Mann.

I would also like to congratulate you for the remarkable innovations you have given to the popcorn manufacturing and snack food industries.

Best of luck with succeeding generations.

Sincerely,

Richard Jacobson

Granada Hills CA.

We are all curious to know why some popcorn carts are called “Paducah Poppers”?

we have wondered this for years.

thank you.

Lisa

Where would the ID plàte be located

A friend of mine has a very nice Cretors cart. He and I were talking and he believes that there is a creators museum in Chicago. I’ll be up there within the next few weeks and would like to visit if it does in fact exist. Any information would be helpful and appreciated.

Thank you

Steve

Have a popcorn box (1918) framed on the wall. Look at it daily and think to myself, this is now part of history.