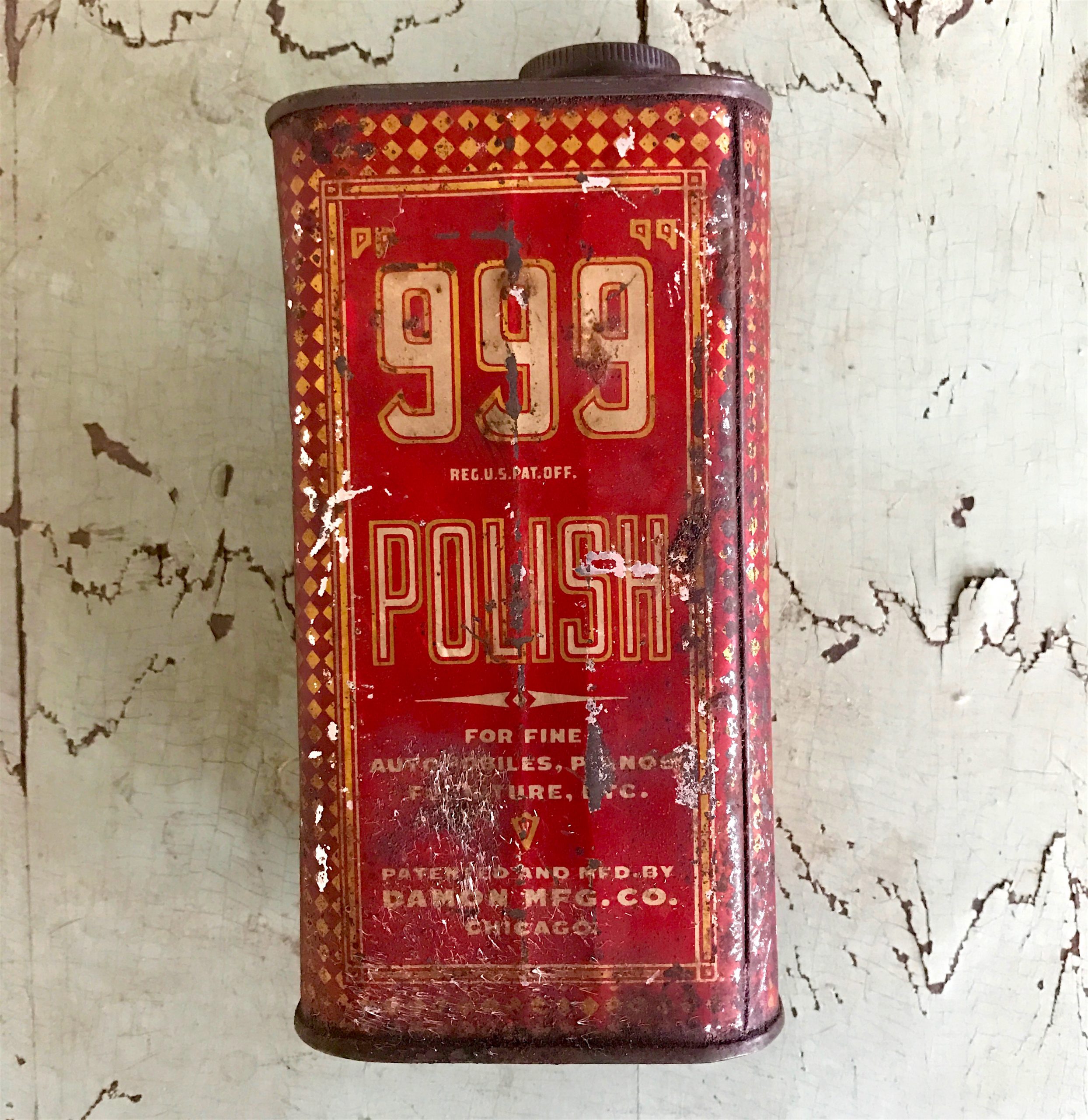

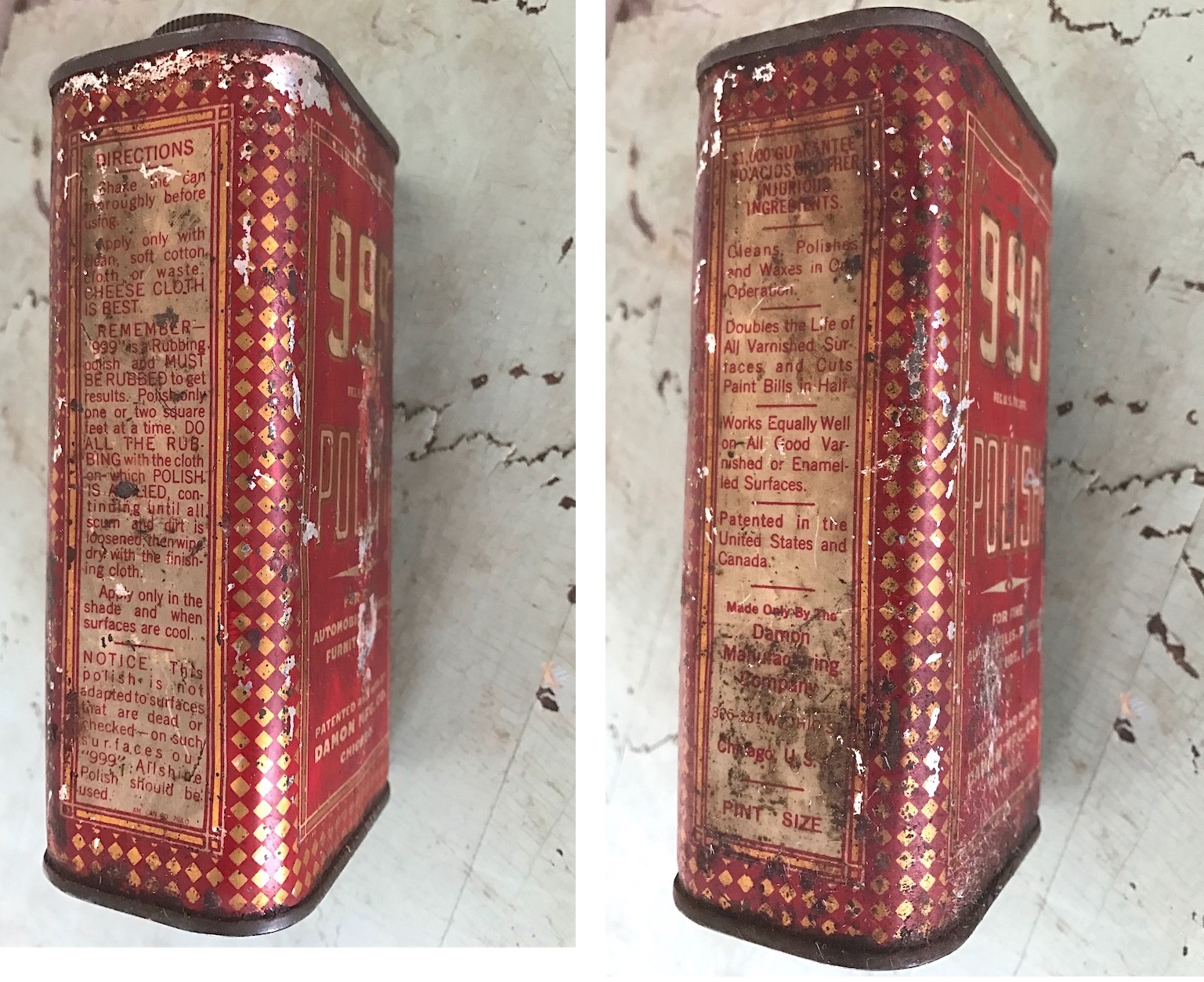

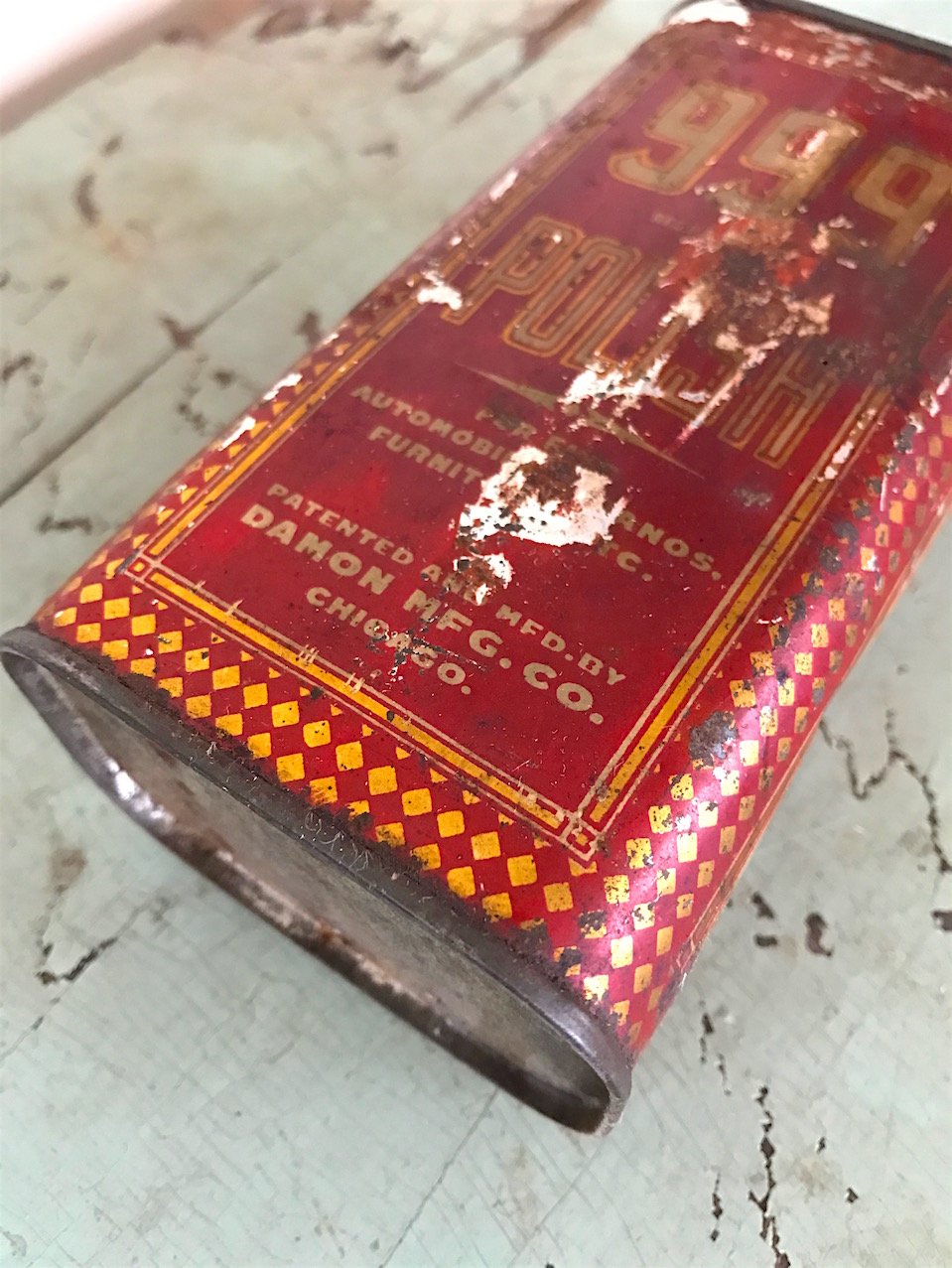

Museum Artifact: 999 Polish for Automobiles, Pianos & Furniture, 1920s

Made By: Damon MFG Co., 325 W. Ohio Street, Chicago, IL [River North]

“Oxidation, it is pointed out by the manufacturer of Damon’s 999 automobile and furniture polish, is the reason for loss of luster and deadened appearance in any varnish finish. It is claimed 999 polish keeps the surface waterproof and airtight with pure wax, preventing oxygen from affecting it. There is no chance for checks, cracks and pores to develop.” —Motor West magazine, Vol. 38, 1922

I suppose it is with some small degree of irony, then, that we present this checked, cracked, pore-ridden and slightly rusty can of Damon’s 999 Polish—a container that could have used a treatment of its own magical contents.

I suppose it is with some small degree of irony, then, that we present this checked, cracked, pore-ridden and slightly rusty can of Damon’s 999 Polish—a container that could have used a treatment of its own magical contents.

Produced in Chicago by the Damon Manufacturing Company., 999 Polish seems to have debuted around 1920 and was sold up until the mid 1930s, when the combination of the Great Depression and the death of the product’s inventor, William H. Damon, spelled the end.

Mr. Damon—or Dr. Damon, as his degree from Chicago’s Dearborn Medical College would suggest—was actually a California boy for most of his life. Whereas most entrepreneurs of his era saw their stories told geographically east-to-west—from Europe and the Atlantic coast to the industrial frontier of the Second City—Damon saw Chicago more as his gateway to the population centers of the “old marketplace.”

Born in Napa, California, in 1873, William Huntington Damon studied science at Napa College before breaking into the piano repair business in San Francisco. That pursuit eventually took him east to the piano manufacturing hub of Chicago, where he caught on first with the Shoninger Piano Company, then for several years with the Bush & Gerts Piano Co., and finally a five-year gig with the John Church Company.

[W.H. Damon cut his teeth as a piano repairmen and builder for companies like Chicago’s Bush & Gerts Piano Co.]

[W.H. Damon cut his teeth as a piano repairmen and builder for companies like Chicago’s Bush & Gerts Piano Co.]

Around the turn of the century, while still building pianos with Church, Damon started studying medicine at the aforementioned Dearborn College, a new school that wasn’t exactly on its way to high esteem (it closed by 1907). That still gave W. H. Damon a small window to graduate with the class of 1904, leading him on a rather dramatic transition into life as a practicing Chicago physician. His most important achievement from this era, however, actually occurred while he was still a lowly piano mechanic.

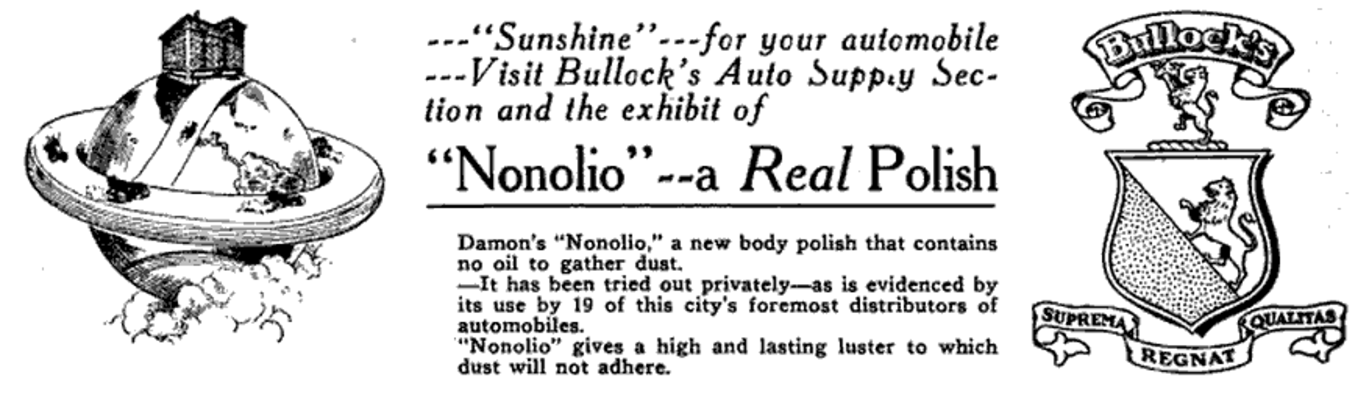

In the late 1890s, having seen his share of rusted and greasy piano parts damaged beyond repair, Damon put some of his old chemistry knowledge to use and devised a new type of furniture polish for keeping the instruments clean and oil-free. He called it “Non-Olio,” and it became something of a local sensation among piano-men and—as a happy accident some years later—automotive workers, as well.

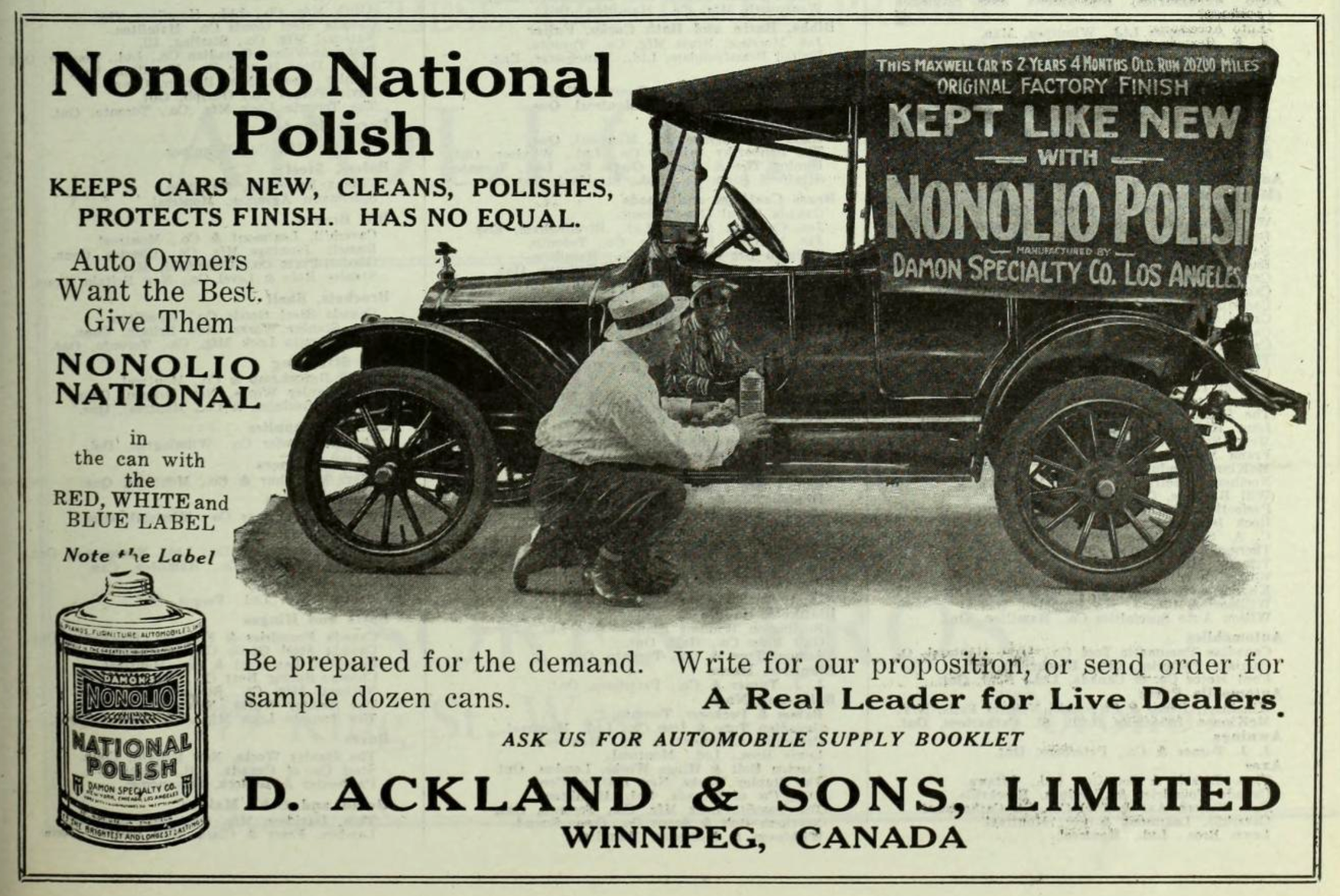

[An early advertisement for Damon’s Nonolio polish, 1914]

[An early advertisement for Damon’s Nonolio polish, 1914]

By 1908, four years into his career practicing medicine, Dr. Damon came to the realization that his patented Nonolio polish actually offered him a much easier meal ticket than the daily physician grind. So, in another major pivot point in his life, he decided to essentially push the rewind button at age 35, moving back to California with his wife Grace and returning to his first love, the piano business.

Damon settled in a pre-glitz Los Angeles this time, and launched what would become one of the larger piano repair companies on the West Coast. By 1914, he also started bottling and mass-producing Nonolio on a wider scale under the banner of the “Damon Specialty Company.” The business was headquartered at 516 East Ninth Street in L.A., and could produce up to 5,000 quarts of polish per day. By now, “Dr. Damon” the piano-man had become far better known as an expert on automobile care—still a fairly new field at the time.

The Los Angeles Herald, for example, described Damon as a “local expert” in a 1917 story on the dangers of cleaning cars with water.

“If the car is muddy,” Damon told the paper, “then it should be hosed, but otherwise water should not be used on it above the chassis. The heavy percentage of oxygen in water brings about oxidation of the varnish, which opens the pores and results in the dingy appearance that so many uncared for cars have. The water in this section carries a certain percentage of alkali and this acid soon eats away the varnish.

“If the car is muddy,” Damon told the paper, “then it should be hosed, but otherwise water should not be used on it above the chassis. The heavy percentage of oxygen in water brings about oxidation of the varnish, which opens the pores and results in the dingy appearance that so many uncared for cars have. The water in this section carries a certain percentage of alkali and this acid soon eats away the varnish.

“There should be no acid of any kind in automobile body polish. To be true the acids get away with the dirt—and also the varnish. Then you have a dingy looking automobile or revarnishing bills. Polish that leaves a wax surface preserves the varnish by closing the pores. A little first aid treatment of the right sort at the right time means money in the pocket.”

Call it expertise or self-serving salesmanship. Either way, the Damon Specialty Company was profiting off car owners’ increasing interest in preserving their vehicles’ finishes.

“The Damon Specialty Company has been operating in Los Angeles for several years,” the magazine Touring Topics reported in 1917, “and has acquired a reputation for its product all over the country. Nonolio is now not only shipped to all the automobile centers of the United States but it also has a considerable foreign sale. According to Dr. Damon, Nonolio has acquired its present high volume of sales through sheer merit and word-of-mouth advertising. As an example of this most effective kind of advertising, Dr. Damon has received during the present week three letters, from Canada, Montana, and New York, respectively. Each of these letters is from a Southern California visitor during the present summer who made the acquaintance of Nonolio here and each one on returning home wrote to express his high regards for it and to inquire how he could secure Nonolio locally.”

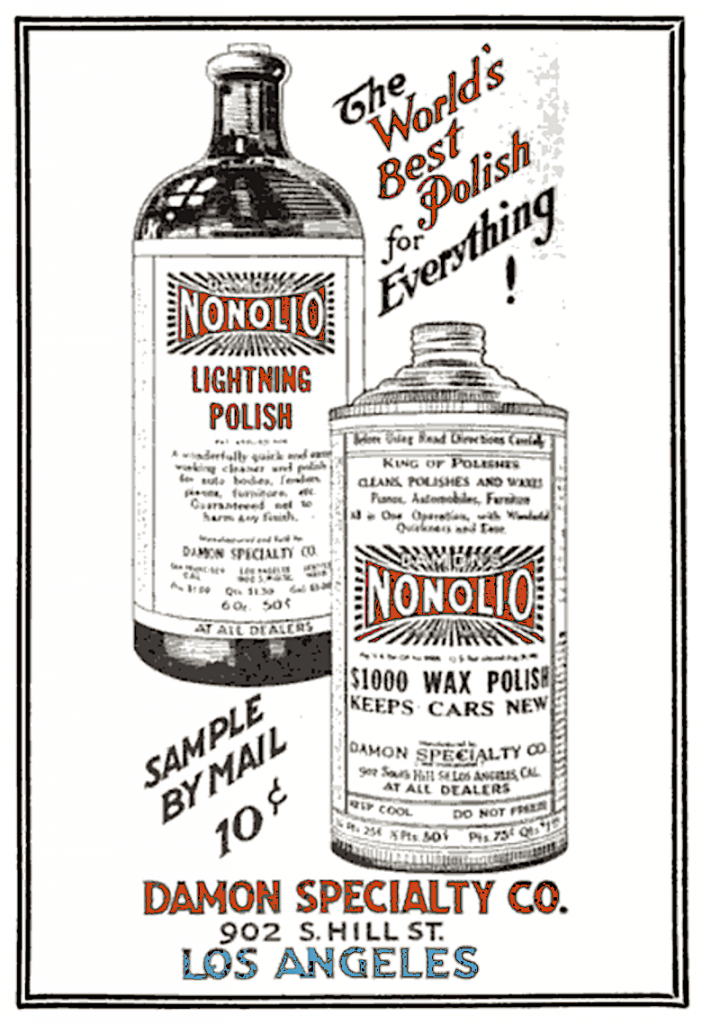

[Nonolio ad from 1919, right around the same time 999 Polish was introduced out of Chicago]

[Nonolio ad from 1919, right around the same time 999 Polish was introduced out of Chicago]

As demand grew, Damon knew that shipping all of his product out of the far-flung desert town of Los Angeles wasn’t the wisest course of action. He quickly expanded the Damon Specialty Co. business, first up north to San Francisco and Seattle, then back east to his old stomping grounds.

“The Middle West will soon be invaded, with Chicago as the center of distribution for that section,” Damon told the Los Angeles Herald in 1917, using some questionable battlefield lingo right before mentioning the actual war in Europe. “In spite of the war situation we are of the opinion that business will continue in the same volume that it is now. The fact that we are going to expand along general lines and go into new territory is evidence enough how we view the future.”

Sure enough, within a year or two, the “Damon Manufacturing Company” had been established in Chicago—functioning as a sort of sister operation to the Los Angeles firm. It’s not entirely clear why the business didn’t simply share the same “Damon Specialty Co.” name, and it’s also unclear why 999 Polish, rather than Nonolio, became the Chicago firm’s flagship product. Regardless of the regional differences, though, William H. Damon was still the president of both Damon Specialty and Damon MFG—running his cross-country empire from his home in Los Angeles. He hired Charles H. Brownson as the VP of the Damon MFG Co., with Charles Rathner serving as sales manager. The first Chicago headquarters was located at 901 Rush Street.

I don’t rightly know what the “999” name was in reference to (possibly the early Henry Ford 999 race car), but in any case, the product seemed to carry all the same basic characteristics of the old Nonolio formula, but with a focus more toward the auto industry.

I don’t rightly know what the “999” name was in reference to (possibly the early Henry Ford 999 race car), but in any case, the product seemed to carry all the same basic characteristics of the old Nonolio formula, but with a focus more toward the auto industry.

“The Damon ‘999’ Patent Polish and Wax is said to be satisfactory for Simonizing work on cars, and for renewing the polish on jobs where the varnish is dull,” Motor Age reported in 1921. “It is especially desirable for used cars, as it cleans and polishes these cars with very good results, according to the claims of users.”

“This polish is said to clean and polish in one operation,” added Motor World Wholesale. “Dirt and grease come off with a little rubbing, and a protective, waterproof film remains. It contains no ingredients which might damage the finish. It is put up in half-pint, pint and quart cans. Prices: 50 cents, 75 cents and $1.25 respectively.”

As with Nonolio, William H. Damon seemed content to rely mostly on word-of-mouth and trade publication blurbs to sell 999, as actual advertisements were few and far between

By the late 1920s, the Damon MFG Co. had relocated to offices in River North at 325 W. Ohio Street, which is where the 999 tin from our collection originated. That building is still standing today, home of the Trunk Club among other businesses.

[Former location of the Damon MFG Co. offices, 325 W. Ohio St.]

[Former location of the Damon MFG Co. offices, 325 W. Ohio St.]

It’s hard to say that the market crash of 1929 was specifically responsible for upending the Damon Company, but there are certainly signs that the downward spiral came around the same time period. For one thing, whereas William Damon had listed his occupation as “Manufacturer of Furniture Polish” in the 1920 census, he’d made a surprise return to medicine by 1930, listing his profession as “General Practice Physician.” Damon was 57 by then, living in Los Angeles’s San Carlos Hotel with his wife and presumably doing just fine despite slowing sales for his magic polishes.

Within another four years, though, Damon’s death at 61 seemed to mark the end of his old business for good. While the Damon MFG Co. is still referenced in some publications into the 1930s, the company and its products seem to disappear before the outset of World War II. No amount of rust-prevention was going to bring it back.

And now . . .

DIRECTIONS for using your 90 year-old can of Damon’s 999 Polish:

Shake the can thoroughly before using.

Apply only with clean, soft cotton cloth or waste CHEESE CLOTH IS BEST.

REMEMBER—“999” is a Rubbing polish and MUST BE RUBBED to get results. Polish only one or two square feet at a time. DO ALL THE RUBBING with the cloth on which POLISH IS APPLIED, continuing until all scum and dirt is loosened, then wipe dry with the finishing cloth.

Apply only in the shade and when surfaces are cool.

NOTICE. This polish is not adapted to surfaces that are dead or checked—on such surfaces our “999” Allshine Polish should be used.

SOURCES

“Damon Polish” – Motor Age, Jan 1921

“Damon’s 999 Polish” – Motor West, Vol. 38, 1922

Los Angeles from the Mountains to the Sea, With Selected Biography of Actors and Witnesses to the Period of Growth and Achievement, by John Steven McGroarty

“Non-cumulative wax polish” – U.S. patent 1,240,545, William H. Damon

“999 Patent Polish” – Motor World Wholesale, Vol. 66, 1921

“Damon Co. Opens Service Station” – Touring Topics, Sept. 1917

“New Territory for Nonolio Products Goal of Damon Co.” – Los Angeles Herald, April 28, 1917

I have a small 999 wax tin it is like a shoe polish tin. Looking for info on it. I can send you photo’s of my example.. thank you for you’re time.

Excellent research! Will Damon was my great uncle. His older sister was my grandmother, who was an accomplished singer and who bequeathed to me her love of great music. Will seems to have been The Entrepeneur. I have no photo of him, but a scribbled 1918 note to his mother on a Damon Co. notepad. His father had been a pastor and professor at Napa College. I think he died in Feb 1930, and his wife also died that year. They had no children. Neither of his 2 brothers reached 70.