Museum Artifact: DeVry 16mm Movie Camera, 1929

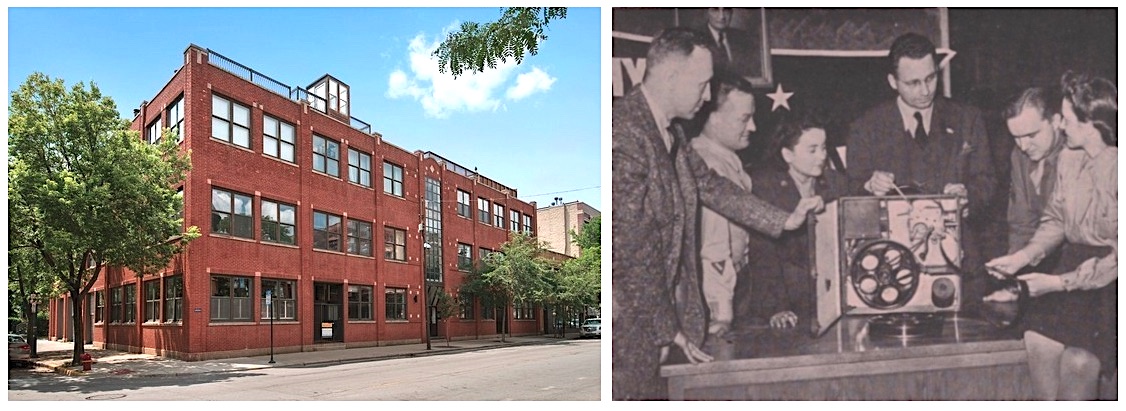

Made By: DeVry Corp. / QRS-DeVry Corp., 1111 W. Armitage Ave., Chicago, IL [Lincoln Park]

“For three decades, Dr. Herman A. DeVry—the man who conceived the idea of projector portability—made a succession of engineering contributions to the progress of visual education that won him a place with Thomas A. Edison and George Eastman on the Honor Roll of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers.” —DeVry Corp. advertisement, 1943

It’s no insult to Herman DeVry that his name is rarely uttered alongside that of Edison or Eastman these days, but it probably is an insult that, as of 2021, the Wikipedia entries on “Movie Projectors,” “Movie Cameras,” and “Educational Film” make no mention whatsoever of the man or his company.

Instead, DeVry’s feats of engineering have been largely overshadowed by the subsequent growth of the Chicago technical school he co-founded in 1931, now known as DeVry University. Still headquartered in nearby Naperville, the college (previously the DeVry Institute of Technology) operates several dozen small campuses across the country, including two in Chicago, with upwards of 20,000 enrolled students in total. As a for-profit institution, however, it’s actually been shrinking in recent years, closing half its locations and facing harsh criticisms and even federal investigations for allegedly deceptive recruitment tactics.

It’s not exactly MIT we’re talking about here, and as perhaps no coincidence, DeVry—both the name and the man—have been deprived of some of the gravitas they once carried.

This is a real shame, because the story of the remarkable Mr. DeVry (he wasn’t actually a “Dr.” as that opening advertisement suggested) and his original Chicago manufacturing business are more than worthy of a revisit. For anyone who appreciates the magic of early motion pictures, or who fondly remembers the cheezy educational films that made the time pass faster in a fifth grade classroom, Herman DeVry ought to be your guy.

[A montage of opening title cards from the educational film library of DeVry Schools Films, Inc., most dating from 1928]

History of the DeVry Corporation, Part I: Carnivals & Magic Tricks

Born in the Mecklenburg-Schwerin region of Germany in 1876, Herman DeVry came to America with his family as a 10 year-old, arriving in New York Harbor in the summer of 1886, when he would have seen the Statue of Liberty being assembled ahead of its dedication later that year. Who knows, maybe a sight like that inspired the kid’s eventual obsession with both mechanical engineering and visual communication. More than likely, though, Herman simply was the right age to get caught up in the wonder of a new, emerging motion picture technology—starting with Louis Le Prince’s first films in 1888 and on through the Edison kinetescopes on display at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, where the working-class DeVry family had made their home.

Eager to make his own mark as a proud new American, Herman flew the coop at a young age. His subsequent adventures are described with little consistency in future retellings, but in all versions, DeVry comes across more like a character from a folktale than the future president of a film equipment business.

Eager to make his own mark as a proud new American, Herman flew the coop at a young age. His subsequent adventures are described with little consistency in future retellings, but in all versions, DeVry comes across more like a character from a folktale than the future president of a film equipment business.

“When Herman was Huckleberry Finn age, he ran away from home and joined a carnival,” wrote Watterson R. Rothacker, a fellow Chicago film manufacturer and former business partner of DeVry. In an amusing article in a 1923 edition of Manufacturers News, Rothacker claimed that one of DeVry’s early tasks as a carny included setting up and taking down the enormous machine used to project films, or “jumping photographs,” inside the big tent, which always “crowded ’em in” at the county fairs.

“One rainy and muddy night Herman took a vow that when he grew up he would invent a projector that could be carried in the vest pocket. He didn’t achieve one quite that small, but years later when he came out with a projector weighing 20 pounds, the next lightest on the market weighed something like over 1,000 pounds. The motion picture industry and sales managers owe much to Mr. DeVry.”

A separate, posthumous account of DeVry’s life in a 1941 issue of Educational Screen magazine runs through Herman’s many adopted hometowns during his days as a young, roving mechanical savant.

[Following President William McKinley’s assassination in 1901, a 25 year-old Herman DeVry regularly screened this film of the funeral procession in his pop-up motion picture theatres, leaving many audiences in awe]

“At the age of 18 he began his ‘business career’ selling barber’s supplies in Texas,” the article claimed. “Shortly, further north, he was retailing skates and baseball gloves across a counter. He ran ‘motion picture theatres,’ such as they were in that day, in Galveston, Texas; in Bisbee, Arizona. But inborn genius for things mechanical soon gained ascendancy. He was now running a bicycle-repair shop in Denver, Colorado; then, an electrical fixture shop in Tulsa, Oklahoma.”

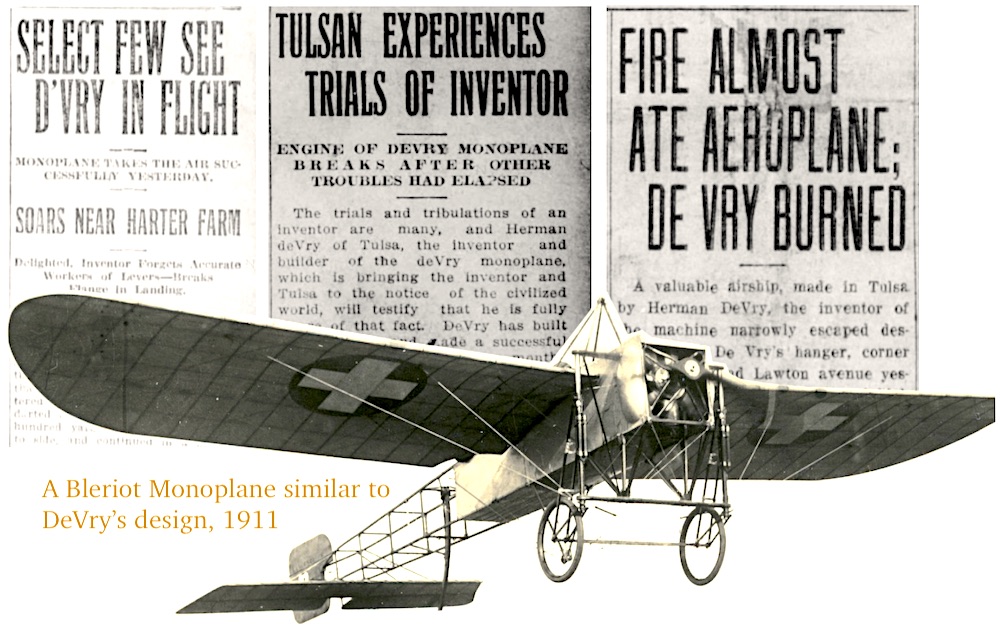

Herman became something of a local celebrity in Tulsa, where he worked his way up to become the city electrician, then made headlines in 1911 by building the first manned airplane successfully flown in the state of Oklahoma (a British aviator named Alexander C. Beech piloted DeVry’s craft). Unfortunately, subsequent attempts to keep the plane airborne proved either disappointing or disastrous, with a final attempt resulting in an explosion that put DeVry in the hospital with serious burns.

[Several local Tulsa newspaper headlines from 1911 show the decreasing returns of DeVry’s experiments in flight. His aircraft, which was based on the well known Bleriot monoplane of the era, had only one, briefly successful journey, but it was the first such manned flight in the state of Oklahoma]

Losing his enthusiasm for flight, Herman soon fled the Sooner State and found himself back in Chicago, making a living building calliopes for his old carnival cohorts. He was also identified by this point, in at least one paper, as “America’s greatest inventor of electrical and mechanical stage apparatus and illusions.”

Motion picture technology was still so new to audiences at this point that many saw it as equivalent to magic—which perhaps makes it unsurprising that DeVry found his way into that line of entertainment, too, working with major headlines magicians like Howard Thurston. It was in 1912, though, at the age of 36, that Herman really found a clear focus for his cinematic passions.

Motion picture technology was still so new to audiences at this point that many saw it as equivalent to magic—which perhaps makes it unsurprising that DeVry found his way into that line of entertainment, too, working with major headlines magicians like Howard Thurston. It was in 1912, though, at the age of 36, that Herman really found a clear focus for his cinematic passions.

Hired as a cameraman by the aforementioned Watterson Rothacker of Chicago’s Industrial Motion Picture Co. (later known as the Rothacker Corp.), Herman was regularly on the road making professional films of a promotional or educational bent—there was one, for example, that was simply about the use of concrete for building America’s new highways. As a road weary camera and projector operator, DeVry’s lifelong dissatisfaction with the enormity and heft of the equipment finally reached a breaking point.

By the end of the year, he had invented the Model E portable film projector, aka “The Theater in a Suitcase” model, and its success would carry him much higher than any dodgy propeller plane ever could.

II. The Theater in a Suitcase

“It’s here at last—a compact, lightweight, easily portable projector of professional quality. Not an experiment—but a machine of tried and proved efficiency.” —advertisement for the DeVry Portable Projector, 1916

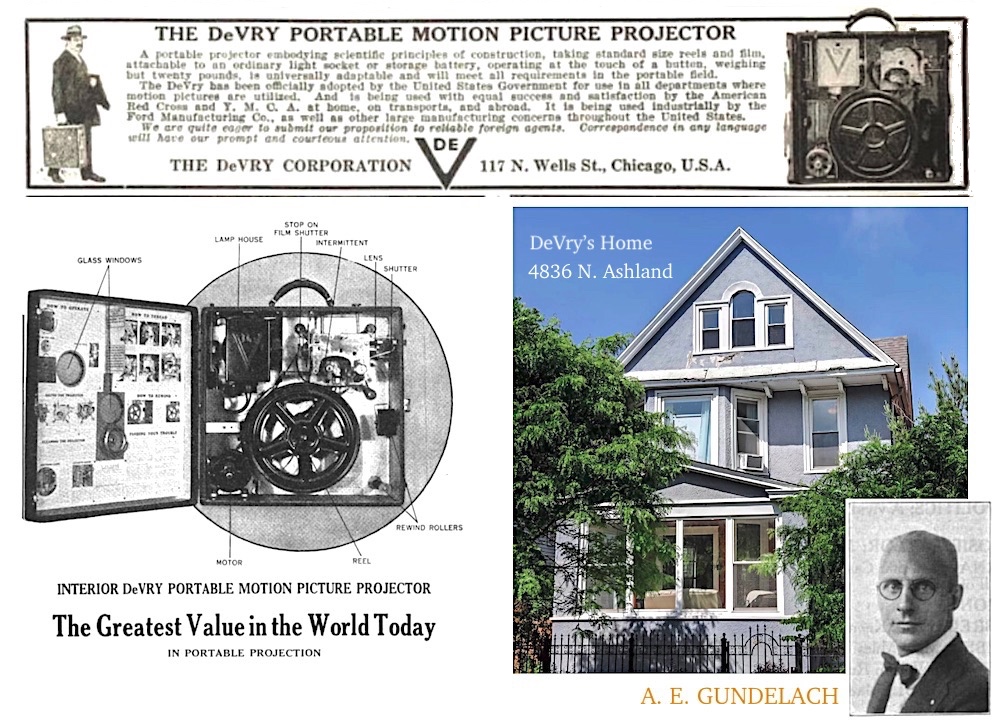

As with most technological breakthroughs, the 20-pound Portable Projector wasn’t created out of the ether, or without assistance. Several like-minded projectionists had been working on similar suitcase prototypes, including Swedish-born inventor Alexander F. Victor of Davenport, Iowa—founder of Chicago’s Victor Animatograph Corp. To beat him and all other challengers to the finish line, Herman DeVry recruited an experienced partner in the form of A. E. Gundelach, who was heading up the motion picture department over at the Chicago camera firm of Burke & James.

As with most technological breakthroughs, the 20-pound Portable Projector wasn’t created out of the ether, or without assistance. Several like-minded projectionists had been working on similar suitcase prototypes, including Swedish-born inventor Alexander F. Victor of Davenport, Iowa—founder of Chicago’s Victor Animatograph Corp. To beat him and all other challengers to the finish line, Herman DeVry recruited an experienced partner in the form of A. E. Gundelach, who was heading up the motion picture department over at the Chicago camera firm of Burke & James.

Working out of the basement of Herman’s home in Uptown (4836 N. Ashland Ave.), the duo hammered out the design of the Model E, a 17” x 17” x 7.5” box that could run standard reels and films—powered initially by a hand crank, but soon after by electric motor. In the years that followed, it was Gundelach who handled much of the sales strategy for the machine, eventually inking lucrative deals with the Ford Motor Company and the U.S. Government to adopt the projector for its own traveling film needs.

Suffice it to say, DeVry’s basement wasn’t going to work as a long term manufacturing hub, and after the fledgling DeVry Corp. was officially incorporated in 1915, there were several upgrades in headquarters, from 117 N. Wells Street to a couple Lincoln Park locations: 1248 Marianna Street (now known as 1248 W. Schubert Avenue) and finally 1111 Center Street (now 1111 W. Armitage Ave.). The latter factory and offices would remain in use from the early 1920s through World War II.

Meanwhile, coming out of the First World War, DeVry’s impact was already being felt on a global scale. According to a 1921 issue of The County Agent, “films can now be shown any place a Ford can travel,” thanks to an innovation that enabled the suitcase projector to hook up directly to the engine of a typical Model T Ford. “County agents use these roving theaters to display agricultural films to farmers. . . . The Red Cross delivers health messages to isolated localities. Rural salesmen employ the traveling theaters to demonstrate modern farm equipment. Welfare work is carried on in lonely mining and lumber centers. These roaming theaters are also speeding up the rehabilitation of destitute Europe.”

The Model E sold somewhere in the neighborhood of 50,000 units over the decade between 1915 and 1925, and its popularity not only made Herman DeVry a rich man; it established the DeVry Corporation—whether by chance or design—as the leading force in the as-yet unnamed industry of “distance learning.” The company’s advertising department wasn’t shy about embracing its newfound cultural significance either.

The Model E sold somewhere in the neighborhood of 50,000 units over the decade between 1915 and 1925, and its popularity not only made Herman DeVry a rich man; it established the DeVry Corporation—whether by chance or design—as the leading force in the as-yet unnamed industry of “distance learning.” The company’s advertising department wasn’t shy about embracing its newfound cultural significance either.

“For years men have labored and experimented,” read one 1921 ad. “Test after test, brains, brawn and money have been focused on the hope of realizing what is to their mind the greatest contribution to their fellowmen—to make practical the universal use of motion pictures, mankind’s greatest aid to thought dissemination.

“Visualize in your own mind a whole factory with one aim, one object—every man imbued with the spirit of the work, each contributing his best to materialize their hopes. The result—the DeVry Portable Motion Picture Projector, the invention of the ingenious brain of Mr. H. A. Devry, produced by his inspired organization. . . . When the first DeVrys appeared, they at once became the nucleus for the intensive application of motion pictures in the school curricula, as the educational utility of motion pictures depended wholly upon the practicability of their mechanical application. Today, over 90% of the Portable Projectors in use are DeVrys.”

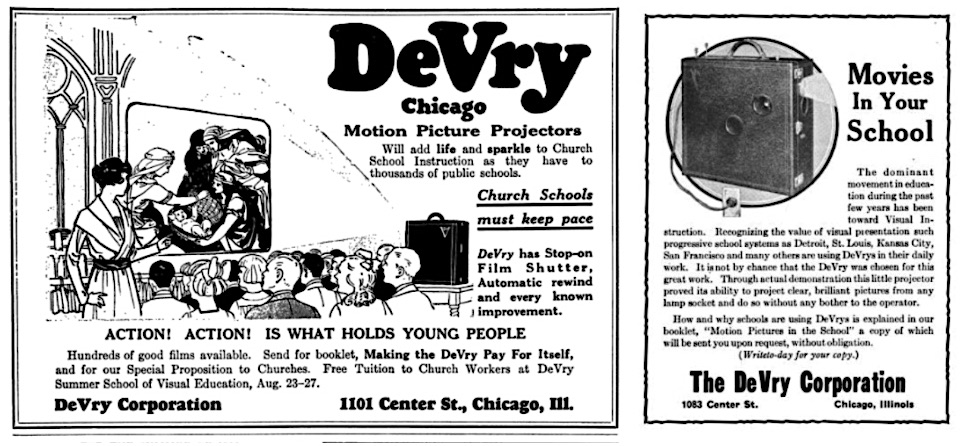

Of course, that sort of market domination wouldn’t last for long. Other manufacturers, including Chicago’s own Bell & Howell, had comparable if not superior lightweight projectors in production by the mid ‘20s. Herman DeVry and his team weren’t caught off guard by this, though. Along with developing new products—such as the Model A film camera and improved Model G projector (both released in 1925)—the DeVry Corp. put a lot of its focus on building up a library of its own educational films, under the name of DeVry School Films, Inc. On a broader scale, there was also a mission to promote the use of film equipment as a new skill and trade worthy of scholarship—an impressive vision coming from a man, Herman DeVry, who’d never even completed high school himself.

While most projector manufacturers included basic instructions in their catalogues for the proper handling and use of film, DeVry created a whole discipline . . . a methodology for how to think about motion pictures as a tool for education rather than theatrical entertainment.

“Hundreds of school systems throughout America are enthusiastically employing the power of motion pictures to add new life and interest to the classroom,” read one DeVry ad. “Courses of study, heretofore dull and uninteresting, are now dramatically taught in this fascinating new way.”

In July of 1925, Herman and his staff (including factory manager G. K. Weis and film editor Andrew P. Hollis) held a sort of week-long “summer school” at the Chicago factory, attended by 25 leading men in the burgeoning industry. It included regular screenings of new DeVry films, roundtable talks, a factory tour, and various technical demonstrations. The class doubled in size the following year, and by 1927, Hollis’s guidebook “Motion Pictures for Instruction” became a bible for the industry.

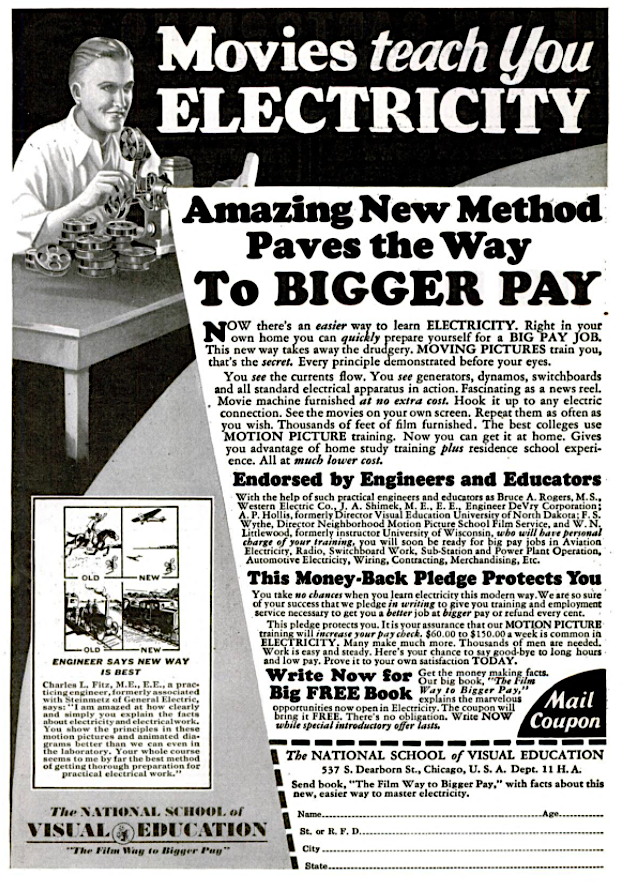

Finally, in 1928, the idea was proposed to start targeting young professionals of smaller financial means; selling them cheap DeVry projectors and instructional films and booklets under the guise of a new career training venture: The National School of Visual Education.

Finally, in 1928, the idea was proposed to start targeting young professionals of smaller financial means; selling them cheap DeVry projectors and instructional films and booklets under the guise of a new career training venture: The National School of Visual Education.

“An amazing new method has been perfected that trains you quickly for a big pay job in ELECTRICITY,” claimed one of the school’s early ads in 1929. “Easier, quicker, better than anything you have ever heard of. We train you through MOTION PICTURES right in your own home.”

To help give the school more legitimacy, Herman called on a friend, the famous inventor Lee de Forest (a pioneer of sound-on-film recording), to lend his blessing and name to the program, and as such, it was re-launched in 1931 as the DeForest Training School . . . the precursor to what we now know as DeVry University.

Of course, Herman DeVry being the adventurous man he was, there was no thought of sacrificing his manufacturing work to focus on this new form of postbox academia. He wanted to remain at the top of both industries, and to do so, he locked himself into another, far less fruitful business partnership.

III. The Brief Tangent of QRS-DeVry

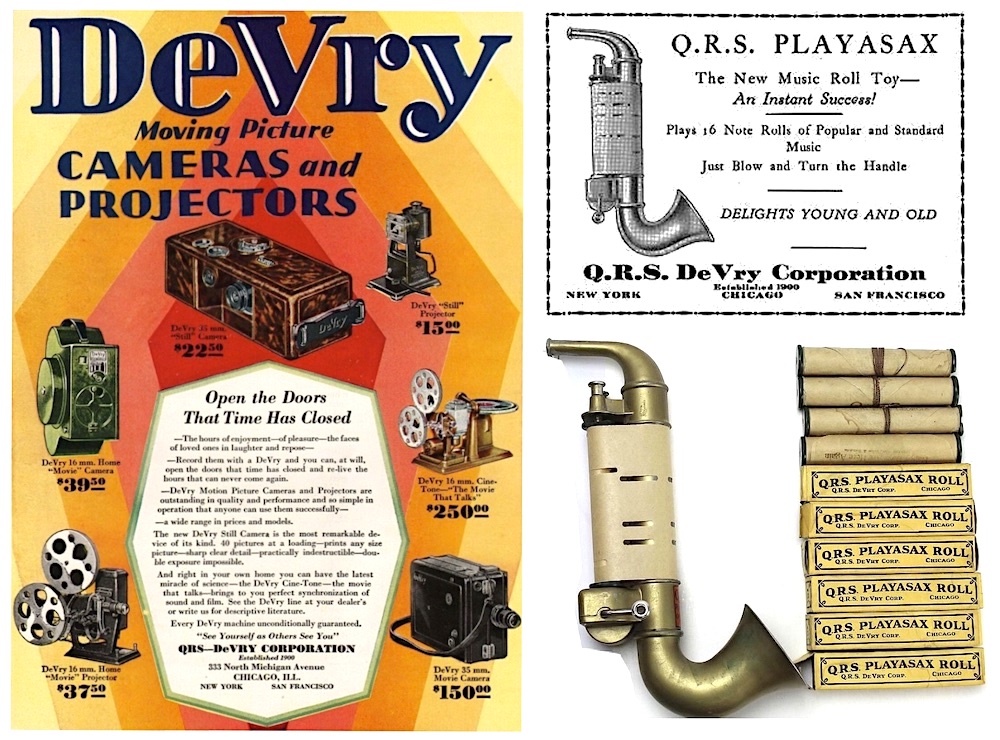

“The hours of enjoyment—of pleasure—the faces of loved ones in laughter and repose. Record them with a DeVry and you can, at will, open the doors that time has closed and re-live the hours that can never come again. DeVry Motion Picture Cameras and Projectors are outstanding in quality and performance and so simple in operation that anyone can use them successfully” —ad for the QRS-DeVry Corp., 1929

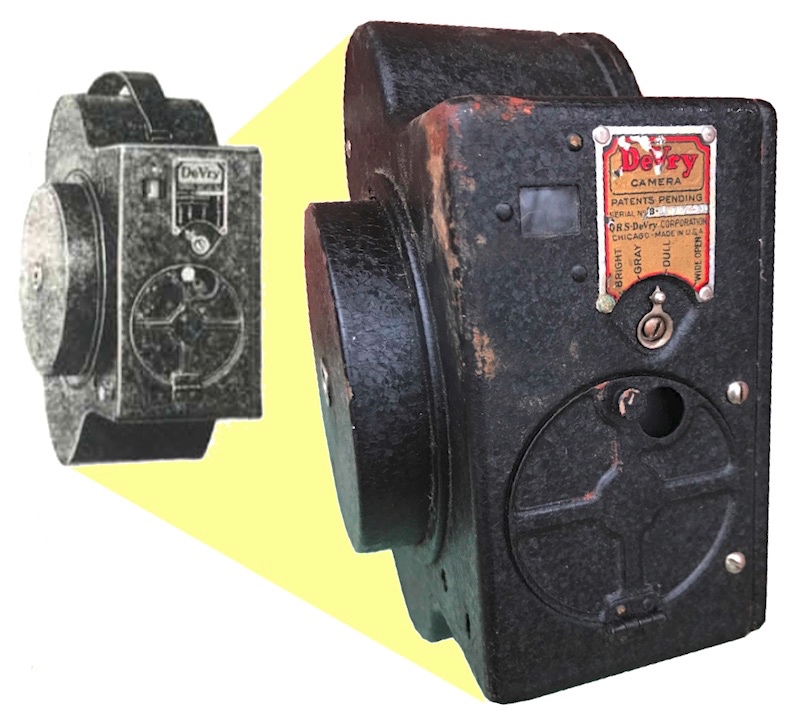

The 16mm movie camera that represents DeVry in our museum collection comes from a specific, fleeting era in the company history— one that Herman DeVry himself might have preferred to forget.

In the early months of 1929, the DeVry Corp. was scuffling a bit, as the company’s big new product, the Cine-Tone “talkie” film projector, wasn’t earning back the money poured into its development. Herman had also attracted some unwanted attention of his own—and a lawsuit—for the alleged misuse of company funds; some of which went into some failed tech experiments, and some of which, it seems, might have paid for his family’s new yacht.

In any case, as he did with A. E. Gundelach and Lee de Forest, DeVry looked for a buddy to help right the ship, and he found one in Thomas Pletcher (b. 1871), head of Chicago’s Q-R-S Music Company—one of the world’s leading manufacturers of perforated music rolls (a type of media still popular enough to move 10 million units for QRS in 1927). Pletcher was nearly 60 years old, but like DeVry, was never satisfied merely celebrating past achievements. With QRS on an upswing and DeVry in need of help, the two men reached a surprising deal: QRS would acquire the business, plants, materials, and patents of the DeVry Corp., with the goal of making big gains in the new field of talking films for the home. The new combined entity, QRS-DeVry, included Pletcher as president and Herman DeVry as VP.

Within weeks, this dream team of Chicago A/V began promoting not only the Cine-Tone projector, but an assortment of new products, including some significantly further afield from past DeVry offerings. There was, for example, the QRS “Playasax”—a toy saxophone partially operated by an inserted music roll. “Just blow and turn the handle. Delights young and old!”

[In its hopeful beginnings, the QRS-DeVry merger sought to combine QRS’s music industry sway with the motion picture powers of the DeVry brand . . . but the marriage never sounded quite right]

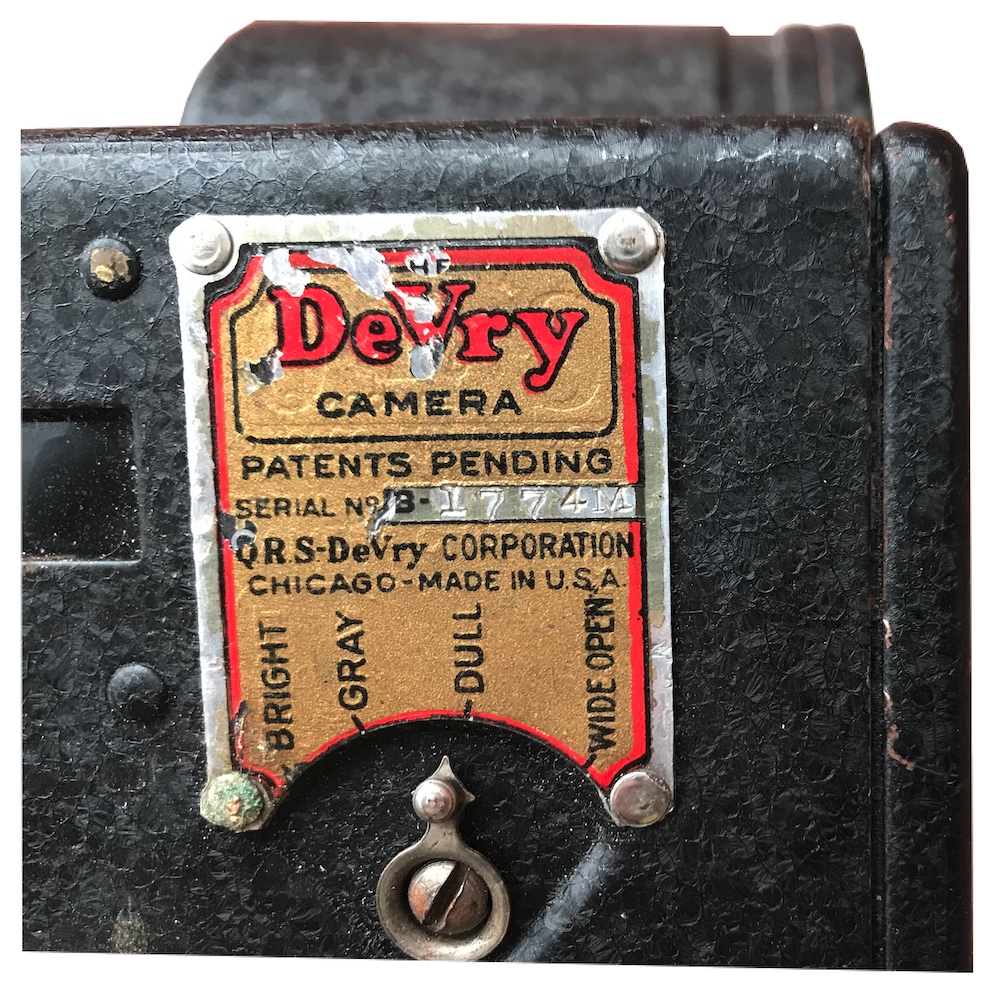

Another new entry was our museum artifact, the DeVry 16mm Model B Camera: “A movie camera amazingly simple to operate,” one ad claimed. “Spring motor driven or hand cranked. Only three lens diaphragm adjustments—for bright, grey and dull days. Two view finders—one for waist and one for eye level sighting, and a footage dial showing the exact amount of films taken.”

A 1929 article in The Music Trade Review further noted that “perhaps of all the line of cameras that the Q-R-S DeVry Corp. has, their Model B 16mm home movie camera is the most popular. Certainly it sells in the largest quantity because it fills the largest measure of personal demand and enables the amateur to make his own movies and then to project and repeat them on the screen to the edification of himself and his friends.”

A 1929 article in The Music Trade Review further noted that “perhaps of all the line of cameras that the Q-R-S DeVry Corp. has, their Model B 16mm home movie camera is the most popular. Certainly it sells in the largest quantity because it fills the largest measure of personal demand and enables the amateur to make his own movies and then to project and repeat them on the screen to the edification of himself and his friends.”

In the summer of 1929, you might have saved up to buy the Model B Camera for $39.50 (a little over $600 in today’s money). But you probably would have regretted it a few months later, when the stock market collapse sent the economy into a free fall. Herman DeVry was likely feeling some regrets of his own. As Pletcher’s QRS-DeVry ship began to sink under its own weight, Herman wondered if his life’s work was going to go right down with it.

IV. Back in Business

Looking back on the QRS-DeVry experiment a decade later (in the May 1941 issue of the Educational Screen magazine), writer Arthur Edwin Krows explained that “with resources invested more in product than in sales organization, [Thomas] Pletcher could not hope to show his customary agility in the face of the storm. The Great Depression and a combination of lesser adverse circumstances suddenly ran the shares of stock down in value before the marketing stage [for an expensive new line of products] could be reached. QRS-DeVry went under, and very little was recovered.”

Both Pletcher and DeVry were “nearly wiped out,” according to Krows, but when Pletcher finally opted to auction off the business (in 1933), Herman DeVry “canvassed his friends and raised enough to buy in the factory and the equipment. . . . Putting it all to work, as he very well knew how to do, he soon cleared his indebtedness and the old DeVry Corporation resumed from where it had been interrupted.”

Both Pletcher and DeVry were “nearly wiped out,” according to Krows, but when Pletcher finally opted to auction off the business (in 1933), Herman DeVry “canvassed his friends and raised enough to buy in the factory and the equipment. . . . Putting it all to work, as he very well knew how to do, he soon cleared his indebtedness and the old DeVry Corporation resumed from where it had been interrupted.”

Back from the brink, the second iteration of the DeVry Corp. (known temporarily as Herman A. DeVry, Inc.) quickly started regaining its old momentum in the realm of visual education. Led by the efforts of Herman’s former bookkeeper Theodore Lefebre, program organizer F. S. Wythe, and educational director A. P. Hollis, the DeVry summer schools remained a beacon for the industry during the Depression. And for young professionals hoping to find new skills and new career opportunities during a dry job market, the DeForest Training Institute offered a way to learn at home; not just about film, but the emerging technologies of radio and sound recording, as well.

During this same period in the 1930s, Herman’s sons Edward B. DeVry (b. 1902) and William C. DeVry (b. 1908), both graduates of the University of Illinois, joined the business and took on leading roles. New products continued to roll out of the factory, including 35mm and 16mm sound cameras and another innovative projector—equipped for sound and film—with a uniquely silent chain drive. These developments helped pull the company out of the depths and into a period of its greatest financial success, as the factory at 1111. W. Armitage grew to a workforce of more than 500.

[Left: The former DeVry Corp. plant at 1111 W. Armitage, which has recently been renovated into apartments. Right: Edward DeVry (far left) and William DeVry (4th from left) explain their father’s classic suitcase film projector to students of the DeForest Training Institute, 1943]

Herman DeVry, while now a figurehead in some respects, never stopped seeking to improve his company’s equipment. As late as 1940, he filed for a patent on a “sound recording and reproducing apparatus” he co-invented with Otto R. Nemeth. The patent was approved in 1942, but Herman wasn’t there to see it.

In March of 1941, while enjoying an evening at a Chicago bowling alley, Herman A. DeVry suffered a fatal heart attack. He was 65.

A tribute to DeVry in the following edition of Educational Screen mentioned his “boundless enthusiasm, innate pioneering instinct, fertility in invention, genius for mechanics, and varied and notable contributions to progress in the field he loved. . . . But great as were his technical and commercial achievements, our warmest regard was for that unforgettable personality, compounded of deep humanness, utter sincerity, genial humor, staunch devotion to the field he believed in so completely, and generous sympathy and unwavering loyalty to his friends and fellow-workers down through the years.”

A tribute to DeVry in the following edition of Educational Screen mentioned his “boundless enthusiasm, innate pioneering instinct, fertility in invention, genius for mechanics, and varied and notable contributions to progress in the field he loved. . . . But great as were his technical and commercial achievements, our warmest regard was for that unforgettable personality, compounded of deep humanness, utter sincerity, genial humor, staunch devotion to the field he believed in so completely, and generous sympathy and unwavering loyalty to his friends and fellow-workers down through the years.”

In November of ‘41, DeVry was posthumously added to the Honor Roll of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers. “No other midwesterner has been so honored by the society,” the Tribune reported. A few weeks later, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, and the role of the motion picture industry in the United States was instantly transformed.

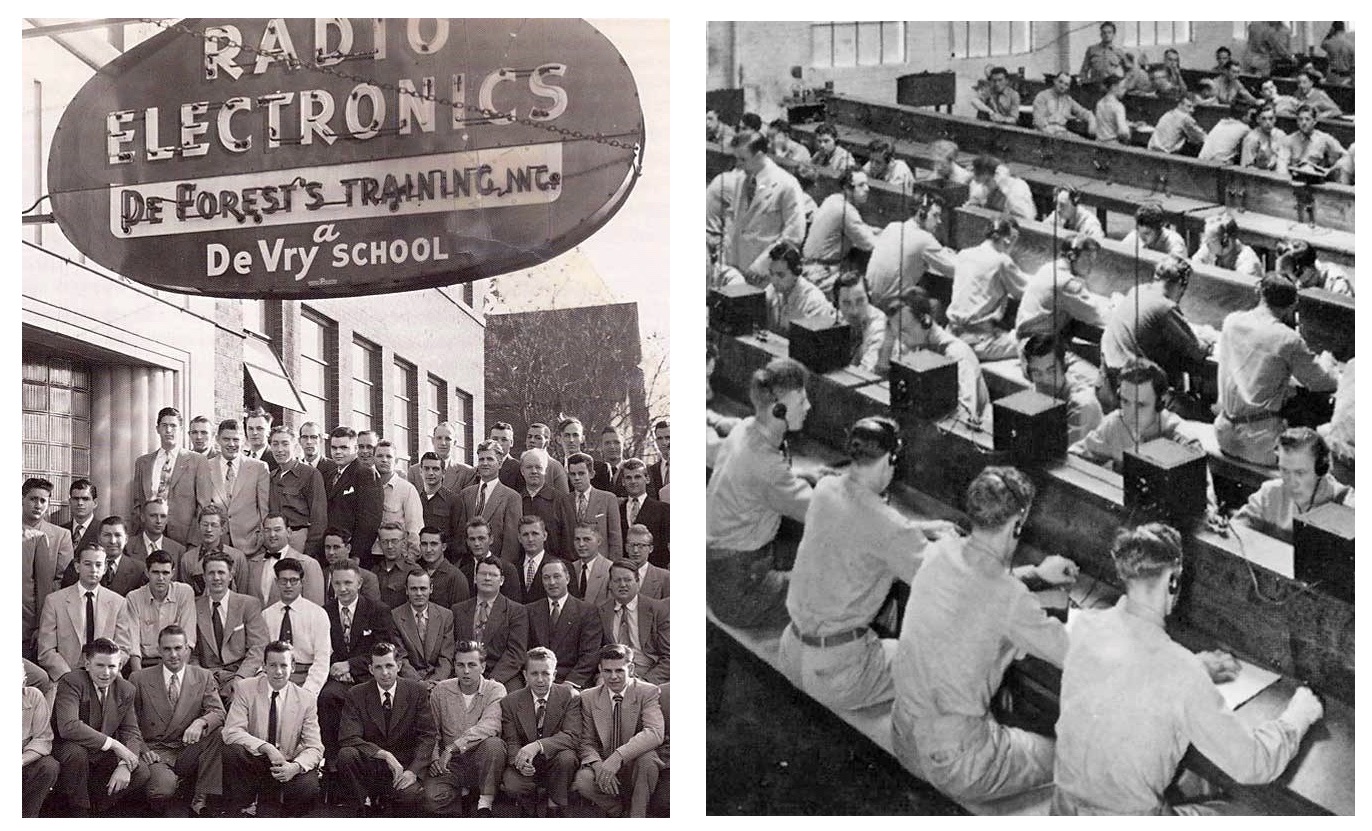

[Students of DeVry’s DeForest Training School, 1940s]

V. Rising Sons

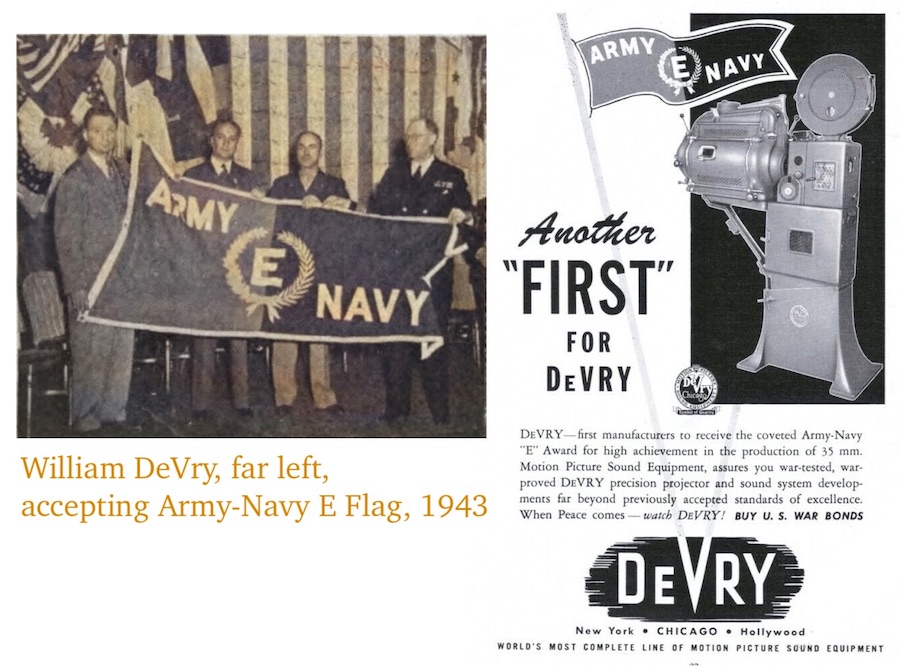

During the war, the DeVry Corp’s reputation earned the company some important government contracts, which not only kept the factory running, but required the use of several facilities and the employment of more than 1,000 workers to produce movie cameras, projectors, and “special training devices” for the Armed Forces.

In 1943, the company was presented with an Army-Navy “E” Award for recognition of its contributions. At the award ceremony, held at the Medinah Club of Chicago, William DeVry—now the company president—addressed a large gathering that included hundreds of employees, industry men, Chicago mayor Edward Kelly, and Illinois governor Dwight Green.

“Although there is no competition in times like these in the sense that we consider competition in peace time,” William said, “we feel a competitive thrill out of this signal honor that our company has won, strictly and solely for the production of motion picture sound equipment.

“Although there is no competition in times like these in the sense that we consider competition in peace time,” William said, “we feel a competitive thrill out of this signal honor that our company has won, strictly and solely for the production of motion picture sound equipment.

“. . . Nor should we overlook the forbearance of our civilian customers whose sympathetic understanding of our primary objective of serving our country has been both a moral lift and physical contribution. Time will come when these civilian customers’ needs will be vital to the progress and profit of the DeVry Corporation. Right now, about all I can do is tell them that they, too, have a share in our ‘E’ Award, and that later we shall find opportunity to repay their patience with new and finer war-born DeVry motion picture sound equipment.”

Like his father, William DeVry was always thinking ahead. And indeed, as with so many tech manufacturers that shut off their civilian sales during the war, the DeVry Corp. carefully considered the future viability of all of its military innovations for general public use. Equally, the company’s relationship with the military didn’t end with VJ Day, as new equipment like the rugged DeVry JAN (Joint Army-Navy) Projector—introduced in 1948—would remain in service through the Korean War.

While William DeVry was running the DeVry Corp., his older brother Edward DeVry was president of DeForest’s Training, Inc., which was playing its own significant role both during and after the war, helping specialist troops learn the use and proper repair of equipment that was now being used not only by American servicemen and women, but by the British Admiralty and the United Nations all over the world.

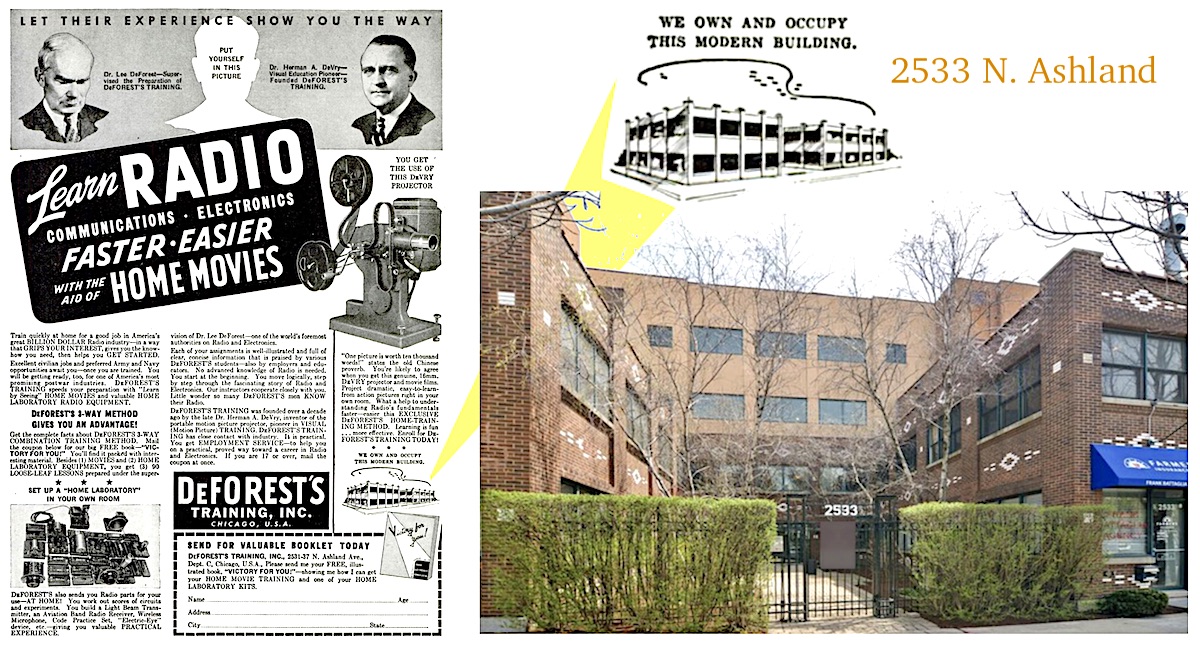

[Left: 1943 ad for DeForest’s Training, Inc. Right: The former DeForest Training School offices at 2533 N. Ashland Avenue, which is now an apartment complex]

With its own headquarters at 2531-37 N. Ashland Ave. (just down the road from the old DeVry family home), DeForest’s Training, Inc., was still doing business with civilians during WWII, as well, ostensibly giving people on the homefront an alternative path for contributing to the greater good.

“Excellent civilian jobs and preferred Army and Navy opportunities await you—once you are trained,” read a 1943 ad, which mentions a training kit (called “Victory For You”) that included a DeVry projector, a selection of movies, and 90 loose leaf lessons supposedly prepared under the supervision of Dr. Lee DeForest himself. “You will be getting ready, too, for one of America’s most promising post-war industries. DeForest’s training speeds your preparation with ‘Learn By Seeing’ Home Movies and valuable Home Laboratory Radio Equipment.”

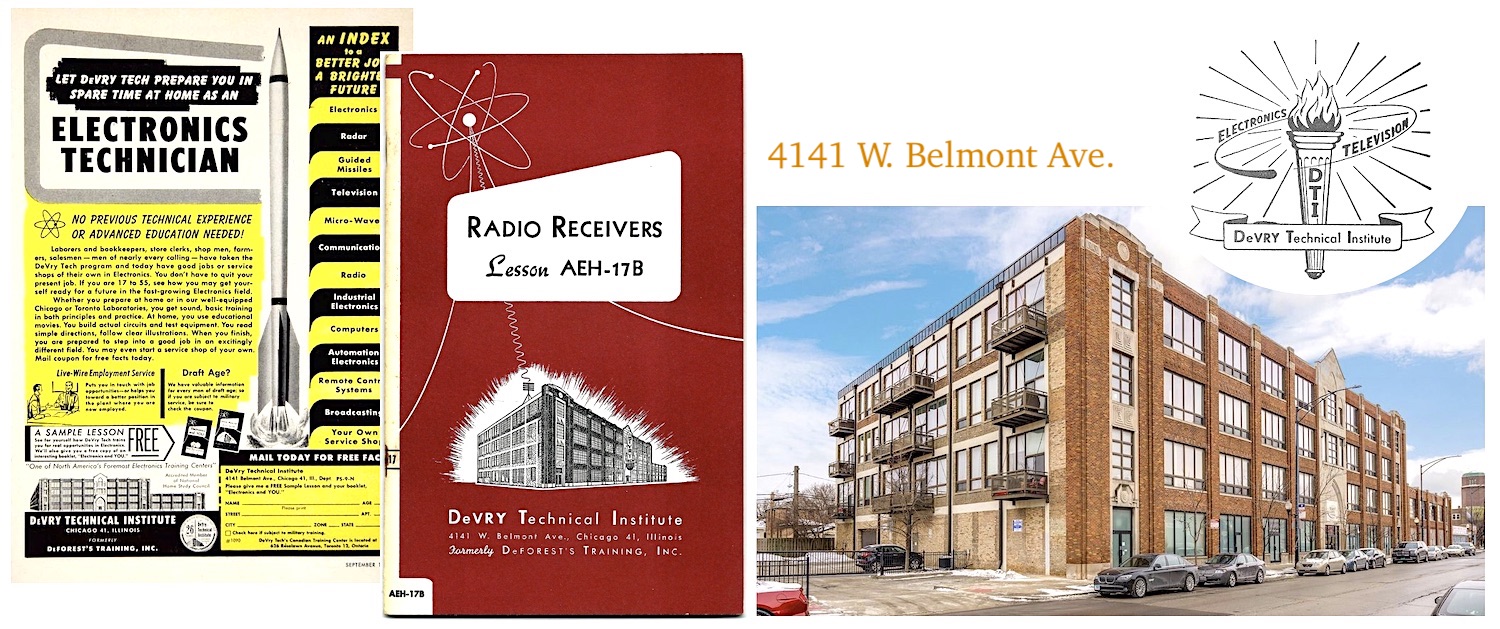

As the radio age gradually moved into the television age and the space race, interest in this type of training only increased, and by 1953, Edward and William DeVry re-organized the DeForest Training School as the DeVry Technical Institute, with a new headquarters at 4141 W. Belmont Avenue.

[The former DeVry Technical Institute HQ at 4141 W. Belmont Avenue has also been converted into apartments]

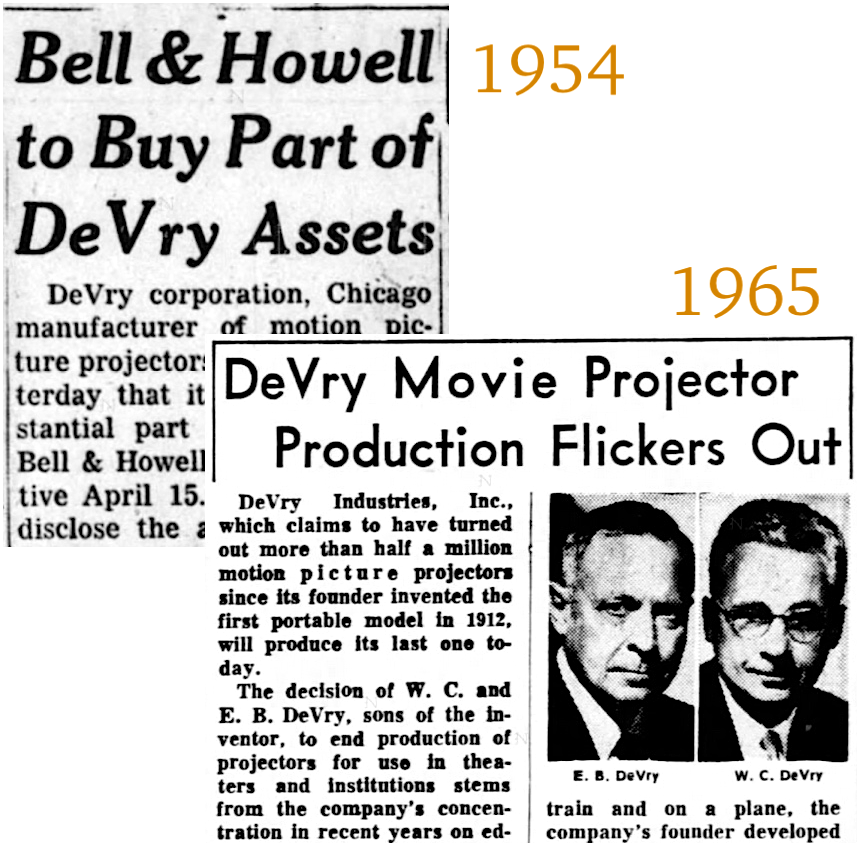

This time around, though, the DeVry sons didn’t repeat their father’s effort of essentially running a college and a factory simultaneously. In 1954, they began outsourcing production of all 35mm movie equipment to another Chicago firm, the Paromel Electronics Corp., which ran production out of the Belmont complex. That same year, DeVry Corp. sold off much of its remaining manufacturing assets to Bell & Howell, including existing patents and government contracts. With the deal, all production of DeVry’s familiar 16mm equipment would come under B&H’s control, migrating to their factory in Skokie.

This marked the end of DeVry’s 30 year run at 1111 W. Armitage Avenue, and it forced 300 employees to seek work elsewhere. Edward and William DeVry didn’t hide the motivations behind the move. Their goal was to focus more on the growth of the institute. And that they did.

By 1957, DeVry became an accredited school for associate degrees in electronics, and in 1968—when Bell & Howell acquired a controlling interest in the school, as well—it merged with the Ohio Institute of Technology to become the DeVry Institute of Technology, offering bachelor’s degrees in electronics.

In Chicago, the manufacturing of DeVry 35mm movie projectors actually continued up until 1965, when Edward and William DeVry—now operating under the name of DeVry Industries, Inc., officially announced the end of all remaining equipment production, about 50 years after their father had made a splash with the suitcase projector.

In Chicago, the manufacturing of DeVry 35mm movie projectors actually continued up until 1965, when Edward and William DeVry—now operating under the name of DeVry Industries, Inc., officially announced the end of all remaining equipment production, about 50 years after their father had made a splash with the suitcase projector.

It had been a company with a “conspicuous list of ‘firsts’ in the motion picture field,” as journalist Don Fabun wrote in a 1953 issue of Alumination magazine. “DeVry equipment had been used by glacial Priest Father Hubbard at 40 below in the Arctic. William Beebe had taken DeVry cameras down to the ocean depths in his bathysphere. The first Graf Zeppelin carried DeVrys, as did Piccard in this balloon flight into the stratosphere. Later, it was a DeVry camera that rode a German V-2 rocket 65 miles above the earth and recorded a 4-1/2 minute movie of the earth falling away below it. . . . Dropped from 25,000 feet, the DeVry camera was recovered with surprisingly little damage and with its precious film intact.”

May the same be said of the legacy of Herman A. DeVry. Though the name’s been forgotten by some and dragged around by others, the contributions of this unique immigrant / magician / aviator / inventor / filmmaker / industrialist / educator are still traceable, still relevant, and still intact.

SOURCES:

“Herman Adolf DeVry” – ImmigrantEntrepreneurship.org

“Tulsa Man’s Aeroplane Flies” – Red River Farmer (Madill, OK), July 21, 1911

“A. E. Gundelach” – Moving Picture Age, October 1921

“Films Can Now Be Shown Anywhere . . . ” – The County Agent and Farm Bureau, November 1921

“Silent Salesman, the Industrial Film, Moves Merchandise When Managers Can’t” – Manufacturers News, Aug 18, 1923

“QRS Co. Buys Out DeVry Corp., Manufacturers of Movie Cameras” – Music Trade Review, March 23, 1929

“Leader in Movies for Educational Use Dies” – The Dispatch (Moline, IL), March 24, 1941

“Herman A. DeVry: 1876-1941” – The Educational Screen, April 1941

“Motion Pictures: Not For Theatres, Part 27” – The Educational Screen, May 1941

“DeVry Awarded Army-Navy E” – The Educational Screen, May 1943

“DeVry, Herman Adolf” – National Cyclopaedia of American Biography, Vol. XXXI, 1944

“Suitcase Theater” – Alumination, March 1953

“Bell & Howell to Buy Part of DeVry Assets” – Chicago Tribune, Feb 18, 1954

“DeVry Movie Projector Production Flickers Out” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 4, 1965

0 I’m an owner of one of the old camera motion picture equipment and I can’t find anything on it I have pictures of it I have it in my handits a type g model number 13273has devey motion picture equipment on it I need some help finding out more about this model it’s all original as well

I went to the DeVry Institute of Technology, graduating in 1979 with an Electronic Technician’s Diploma. I also have a BS in Physics and a BA in Psychology. Only the Diploma from DeVry successfully got me a job whch I have had for over 40 years. I am sorry to hear about all the students who had bad experiences at DeVry but I also knew 2 people from my company that received BSEET Degrees from DeVry University and have very successful careers. The other fellow in my lab got a degree from DeVry and he has been with the company over 30 years.

All I can say is that without DeVry I do not know if I would have had a good life. Thank you Herman, where ever you are

I have a 16MM sound motion devry chicago manufactured by debry chicago model 14000-cc serial 14763 how much i can sell for and where

I have a old devry film camera mi wanted to sell..

I would like to see when you are finished with your research. I was checking on the corporation because of my E flag which was presented for the company’s work during WWII.