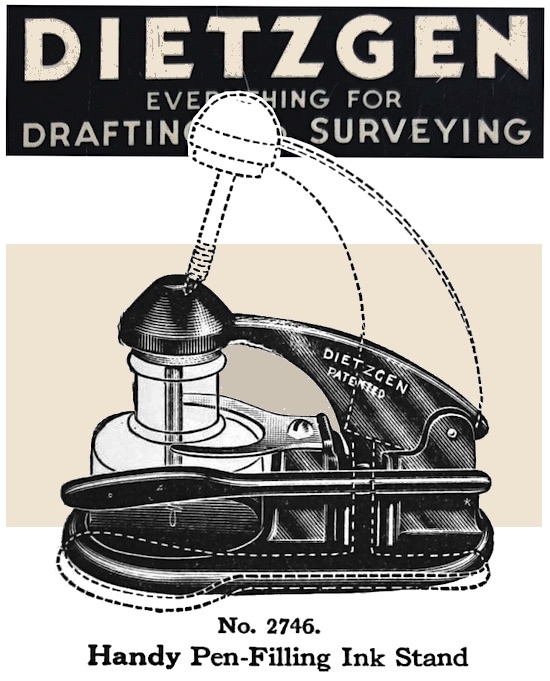

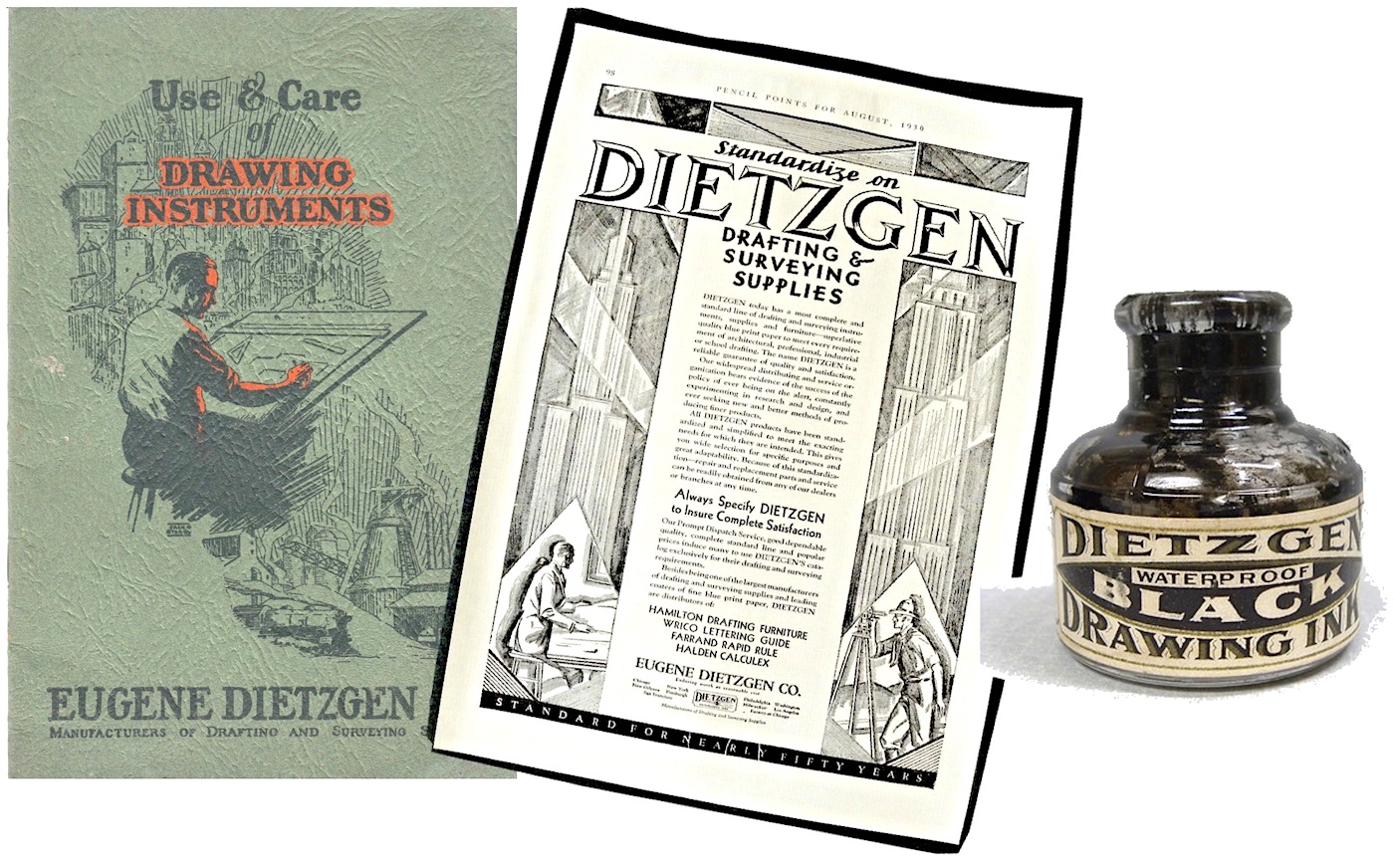

Museum Artifact: No. 2745 Handy Pen-Filling Ink Stand, c. 1930

Made By: Eugene Dietzgen Co., 990 W. Fullerton Ave., Chicago, IL [Lincoln Park]

“Wherever Dietzgen products go, something important is always brewing. It may be in a little office in some huge factory where a new high-altitude plane is being born on the drawing board. It may be in far-off Africa where new flying fields or military highways are to take shape amid burning sands for a new turn in war strategy. It may be any of a hundred projects that will affect the lives, the safety, the welfare of millions of people. For Dietzgen products are the tools of engineers, the men who plan, design and build the structures, machines and equipment that make history.” —Eugene Dietzgen Company advertisement, 1942

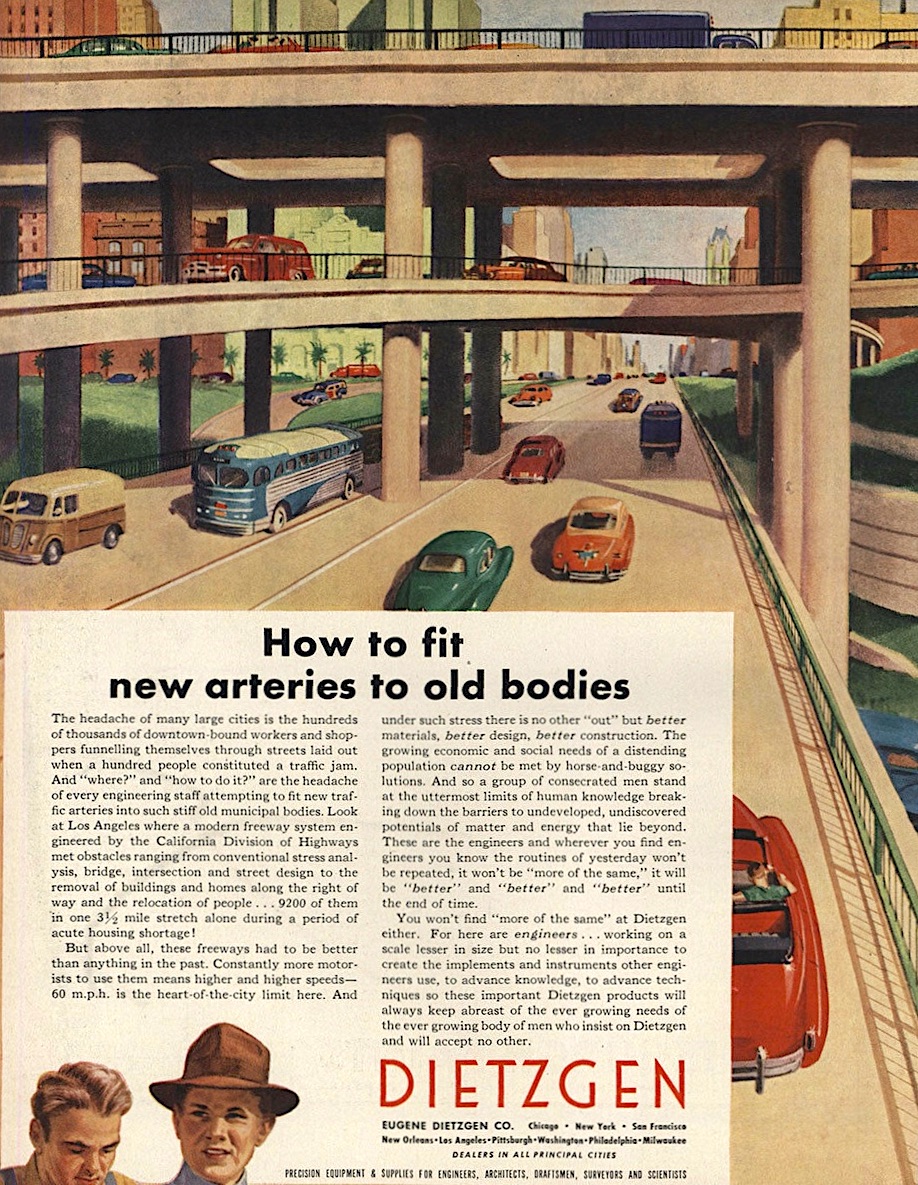

While the products of the Eugene Dietzgen Company had a significant global reach for much of the 20th century, you can just as easily measure their impact by keeping the view local. As the Chicago Tribune once noted on the occasion of the company’s 75th anniversary in 1960, Dietzgen equipment “played a role in varied aspects of Chicago’s development. Its surveying materials were used in readying the site for the Columbian Exposition of 1893; its special orders have included 10 yard chain markers for officials at University of Chicago football contests; and a good part of the equipment used in laying out the area expressway system bore the Dietzgen name.”

While the products of the Eugene Dietzgen Company had a significant global reach for much of the 20th century, you can just as easily measure their impact by keeping the view local. As the Chicago Tribune once noted on the occasion of the company’s 75th anniversary in 1960, Dietzgen equipment “played a role in varied aspects of Chicago’s development. Its surveying materials were used in readying the site for the Columbian Exposition of 1893; its special orders have included 10 yard chain markers for officials at University of Chicago football contests; and a good part of the equipment used in laying out the area expressway system bore the Dietzgen name.”

Anyone who has spent any significant time around the DePaul University campus in Lincoln Park will also likely recognize the impressive four-story red brick building at the corner of Fullerton and Sheffield Avenue. Its key feature, most would agree, is the unusual vintage sign above the side entrance door—a sort-of Art Nouveau, bas-relief design displaying the name of the Eugene Dietzgen Company along with a stylized logo of a draftsman’s compass, t-square, and triangles. The number 1906 is also prominently featured, marking the year that this former factory first opened, destined to become a leading producer of “precision equipment and supplies for engineers, draftsmen, surveyors, and scientists.”

The Dietzgen Company relocated in the 1970s, and DePaul eventually purchased the building around the year 2000, converting it into classrooms. But that surviving sign serves as a daily reminder of Dietzgen’s long tenure as one of the North Side’s most prominent manufacturers. It’s also a monument to one of the more unique Chicago businessmen of the early 20th century—an intellectual German-born socialist who somehow wound up at the forefront of America’s new big-catalog brand of capitalism.

History of Eugene Dietzgen Co., Part I: The Philosopher’s Son

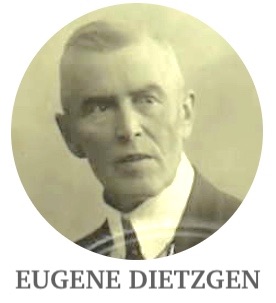

Eugene Dietzgen (1862-1929) spent the first 18 years of his life in Germany and his final 18 years primarily in Switzerland. And yet, he managed to leave his most significant footprint in Chicago, where he became one of the many German immigrants to find success in the city’s booming manufacturing industry. Unlike a lot of those men, though, Dietzgen wasn’t an engineer or an inventor himself; nor was he driven by economic ambition in the typical fashion of a Gilded Age industrialist. The biggest influence in his life, by contrast, was his father Joseph Dietzgen (1828-1888)—one of the leading voices of the Socialist movement in Europe.

Despite coming from a well-to-do family, which operated its own artisan tannery near Cologne, the studious Joseph Dietzgen became awakened to the plight of the working class during his teen years. “The Communist Manifesto of Marx and Engels made a class-conscious socialist out of him in 1848,” his son Eugene later wrote.

Despite coming from a well-to-do family, which operated its own artisan tannery near Cologne, the studious Joseph Dietzgen became awakened to the plight of the working class during his teen years. “The Communist Manifesto of Marx and Engels made a class-conscious socialist out of him in 1848,” his son Eugene later wrote.

Before Eugene was even born, his father had already emigrated to America on two different occasions himself—including a stint running a tannery in Montgomery, Alabama, just before the start of the Civil War. Joseph returned to Germany each time, only further motivated by the horrific human injustices he’d witnessed. By 1870, his dense essays on social democracy gained the attention of Karl Marx—who later befriended Joseph and supposedly dubbed him the “philosopher of the proletariat.”

For Eugene Dietzgen, being the teenage son of a socialist revolutionary—and a traditional, devout Catholic mother—prepared him for a life of instability and contradictions.

In 1880, the Dietzgen family tannery was suffering financially, and patriarch Joseph was increasingly under threat from the authorities (he had already served a three-month prison sentence in Cologne simply for giving a lecture on his views). To make matters worse, Eugene, at 18, was now eligible for Kaiser Wilhem I’s military draft. And so, as Eugene would later remember it, “[my father] suggested to me, his eldest son, after completing my studies at the Siegburg ‘gymnasium,’ to emigrate to the United States and to become the pathfinder for the existence of our family.”

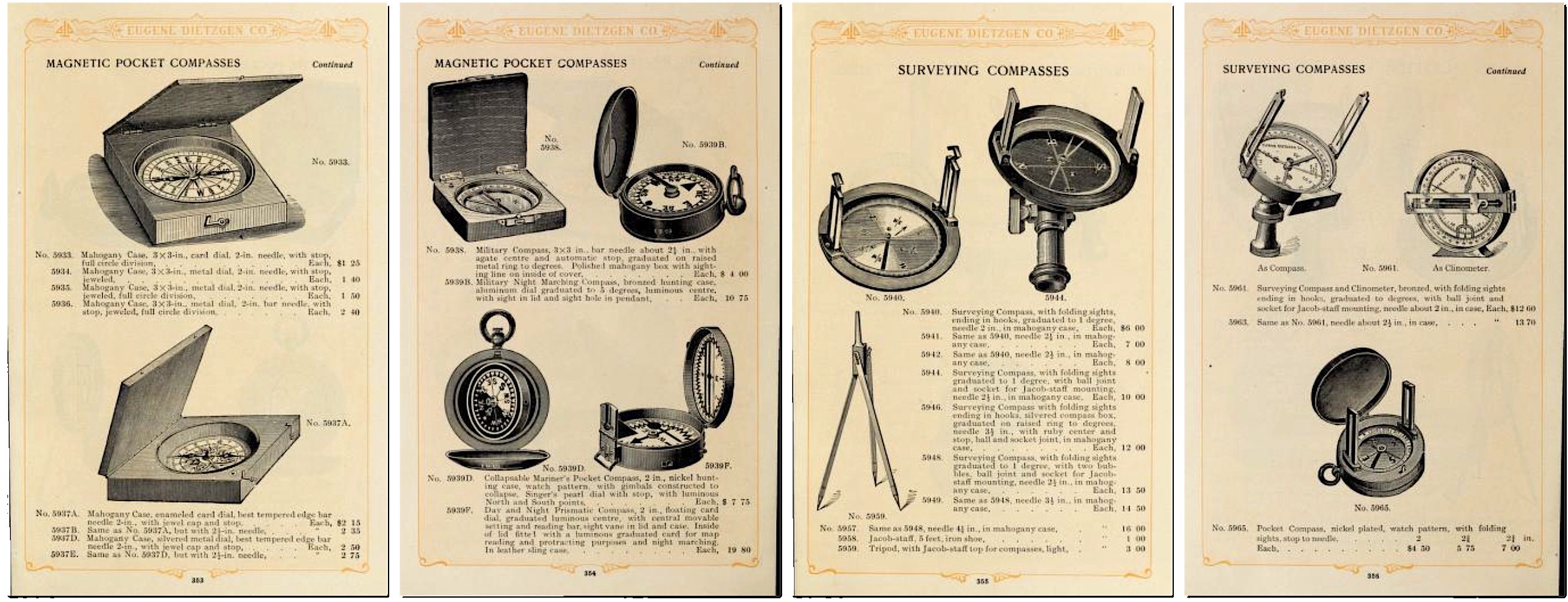

[An assortment of compasses from the 1907 Dietzgen catalog. They have a metaphorical meaning here, as young Eugene Dietzgen set sail for America as the “pathfinder” of his family in 1880]

Accepting this responsibility, Eugene Dietzgen made the long journey from Rotterdam to New York in the spring of 1880. Through regular correspondence, however, his father continued to advise him on how to approach his new life in the New World.

“Above all,” Joseph wrote to his son, “do not forget, while in America, that one should do business for the sake of life, not live for the sake of business. Never be harsh in your judgment of others, but make allowance for their environment. In order to be able to act courteously, you must think courteously. Virtue and faults are always combined. Even the rascal is a good fellow, and ‘the just sins seven times per day.’ Now enjoy life and work bravely.”

II. Business for the Sake of Life

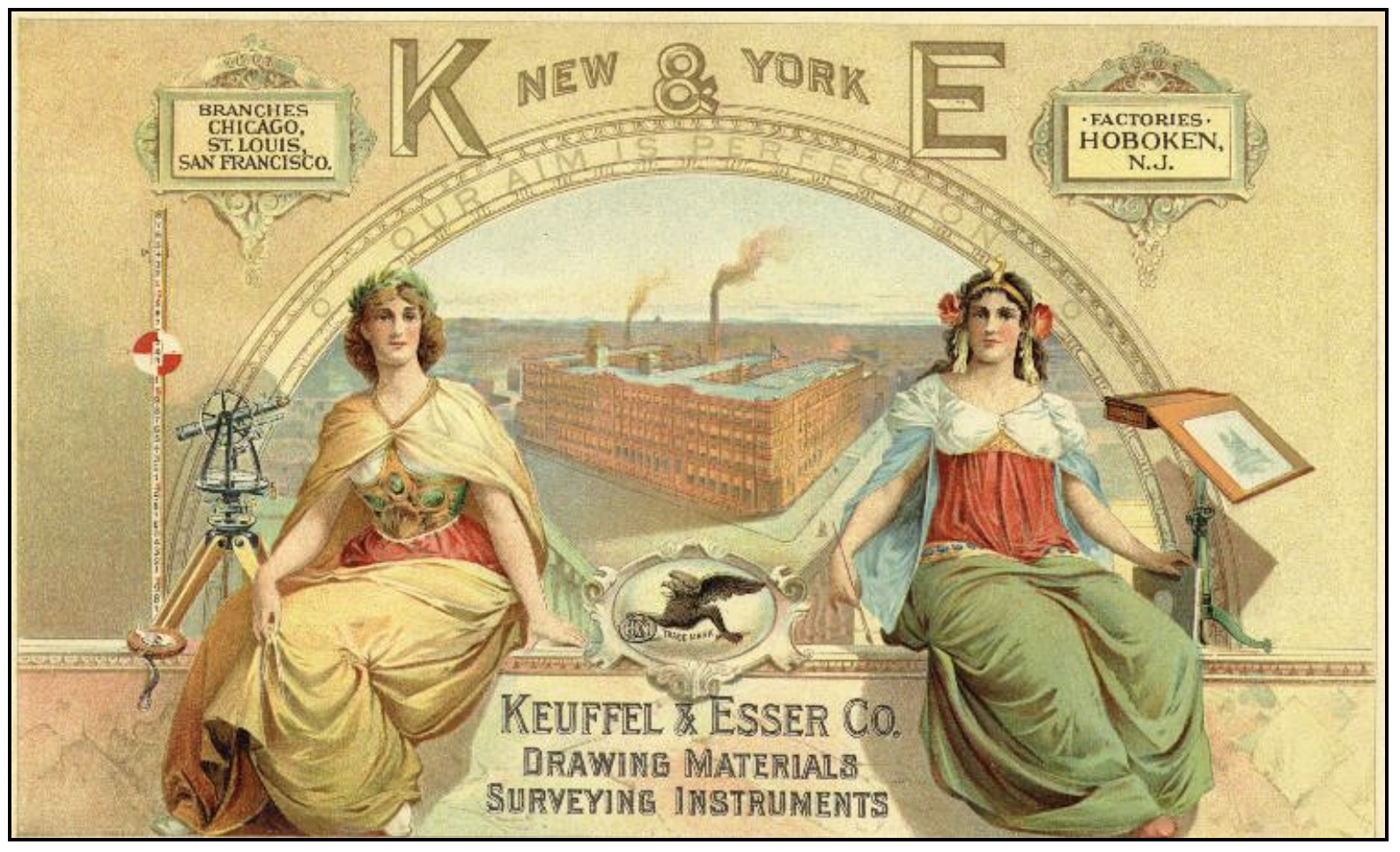

It’s not clear if Eugene Dietzgen landed in New York with some prospects already in mind, or if he truly had to start from square one. In relatively short order, though, it appears that the 18 year-old lad landed a job with the Keuffel and Esser Company—a New York based, German-owned supplier of “drawing materials and surveying instruments.”

Keuffel and Esser had just opened a large factory in Hoboken, New Jersey, and they were expanding their national sales team. Dietzgen, while perhaps not particularly fluent in English at this stage, was clearly sharp of mind and eager for the opportunity, and thus began his career in the engineering supply trade.

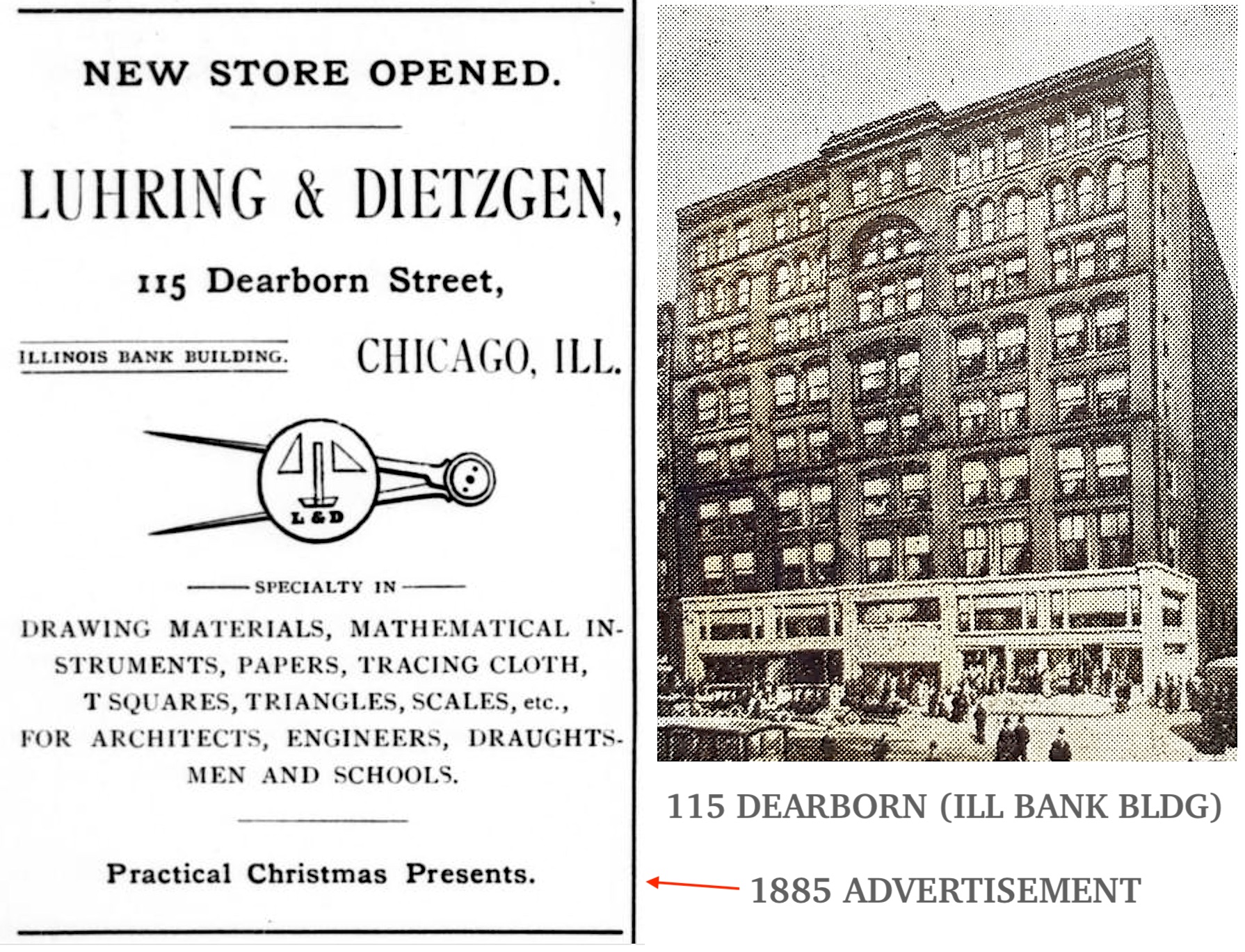

Representing Keuffel & Esser as a western sales agent, young Dietzgen did regular business with K&E’s big Chicago-based distributor, A. H. Abbott & Company, and soon became friends with a fellow German transplant in charge of Abbott’s Mathematical Instrument and Drawing Material Department. His name was Otto Luhring, and by 1885, the two pals had abandoned their old companies to form a new draftsman supply firm of their own, Luhring & Dietzgen, with a main office at 115 Dearborn Street; the brand new Illinois Bank Building.

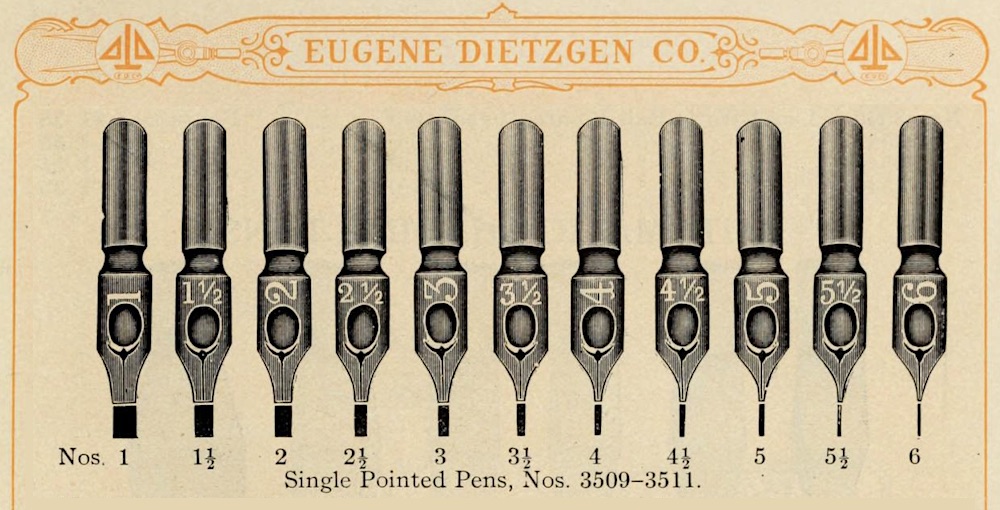

From the outset, the firm already had the compass/triangle/T-square logo that would later adorn the Lincoln Park factory sign, and their catalog was pretty well established, too, albeit largely sourced from outside manufacturers: “drawing materials, mathematical instruments, papers, tracing cloth, T squares, triangles, scales, etc., for architects, engineers, draughtsman and schools.”

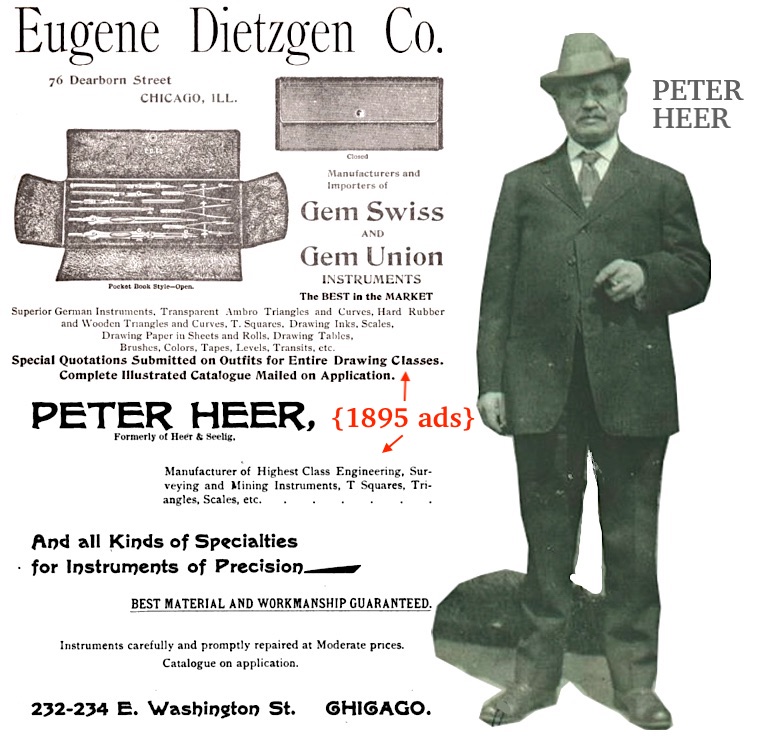

For Eugene Dietzgen, the partnership with Luhring was formative, but altogether brief. Otto opted to return to Germany after a few years, and Dietzgen subsequently bought out his stock and went in search of new comrades. He found a worthy one in Peter Heer (1857-1938), another German immigrant who’d become arguably Chicago’s leading name in “engineering, surveying, and mining instruments.”

In 1893, just ahead of the Columbian Exposition that summer, Heer joined Dietzgen as an incorporator in the new Eugene Dietzgen Company, 76 Dearborn Street, established with $100,000 in capital. The primary goal was to become a major manufacturing and repair business, rather than solely an importer/dealer. But even as a partner, Peter Heer was apparently hesitant to give up his independence entirely. Instead, he agreed to operate his own manufacturing business, the Peter Heer Company, as a wing of the Dietzgen Co.

Heer had his own HQ at 232 E. Washington Street, while Dietzgen soon moved to a larger home at 181 Monroe Street. Based on the reports of the Factory Inspector of Illinois, the combined workforce of the business was still relatively small by 1900—25 workers under the Dietzgen roof, 16 under Heer’s. But sales were strong enough to open a second office on Fifth Avenue in New York, followed by distribution centers in San Francisco (1902) and New Orleans (1903).

Heer had his own HQ at 232 E. Washington Street, while Dietzgen soon moved to a larger home at 181 Monroe Street. Based on the reports of the Factory Inspector of Illinois, the combined workforce of the business was still relatively small by 1900—25 workers under the Dietzgen roof, 16 under Heer’s. But sales were strong enough to open a second office on Fifth Avenue in New York, followed by distribution centers in San Francisco (1902) and New Orleans (1903).

Finally, in 1906, Peter Heer agreed to consolidate his manufacturing efforts under the Dietzgen umbrella; a decision made much easier by Dietzgen’s purchase of a new factory at Sheffield and Fullerton in Lincoln Park.

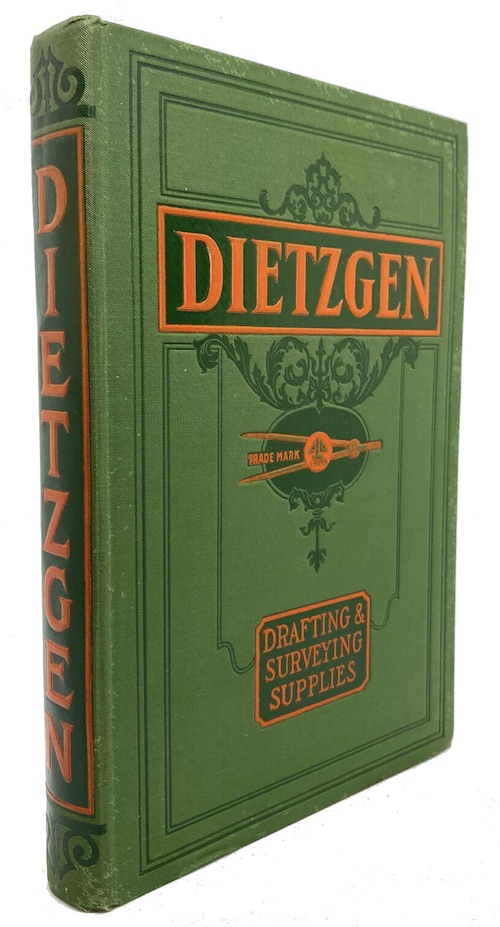

“To meet the constantly growing demand for our products, our manufacturing facilities have been more than doubled by the erection of a new model manufacturing plant at Chicago,” read the intro to Dietzgen’s 1907 catalogue. “This we have equipped with the most modern appliances, in order to secure the highest degree of perfection in the goods produced by us.

“. . . We can assure our patrons that our prices will continue to be the lowest, consistent with first-class material and workmanship. It has been our constant aim to improve the standard of the goods manufactured or controlled by us, and this policy we shall continue to follow.”

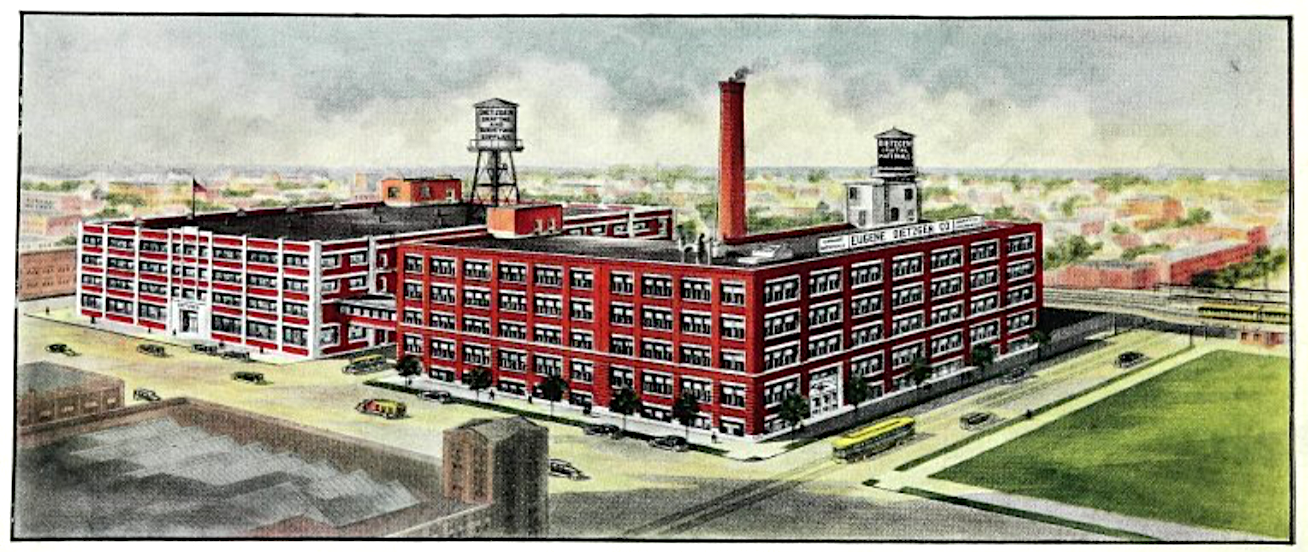

[The Dietzgen factory at 990 W. Fullerton Ave., as it appeared when it opened in 1906 (left) and in 2021, as an expanded building owned by DePaul University]

That same catalog, packed with nearly 500 pages, reveals Dietzgen’s rather unique array of products, ranging from blueprint paper, drawing instruments, and slide rules to high-tech, high-priced gear like architects’ levels and transits—many of which still impress as marvels of mechanical engineering. “The materials employed are of the best,” the catalog bragged, “the graduations the most accurate, the lenses for telescope are of the finest quality, and the workmanship and finish of the highest order.”

In these years before World War I, Eugene Dietzgen’s unmistakably German-sounding name probably worked to his benefit. German engineering already had a reputation in some circles, and Dietzgen’s connection to the motherland was more significant than most German-Americans could claim.

In these years before World War I, Eugene Dietzgen’s unmistakably German-sounding name probably worked to his benefit. German engineering already had a reputation in some circles, and Dietzgen’s connection to the motherland was more significant than most German-Americans could claim.

Rather than merely working out distribution deals with German suppliers, he purchased a German instrument factory of his own in 1908. This was highly unusual for the time period, and immediately gave Dietzgen a leg up on most of his U.S. competition. Now, rather than depending on a third party in Europe to provide certain replacement parts, Dietzgen could control inventory on both sides of the Atlantic, enabling him to offer his customers a “Lifetime Service Policy” for older instruments. It was a huge factor in the company’s continued success.

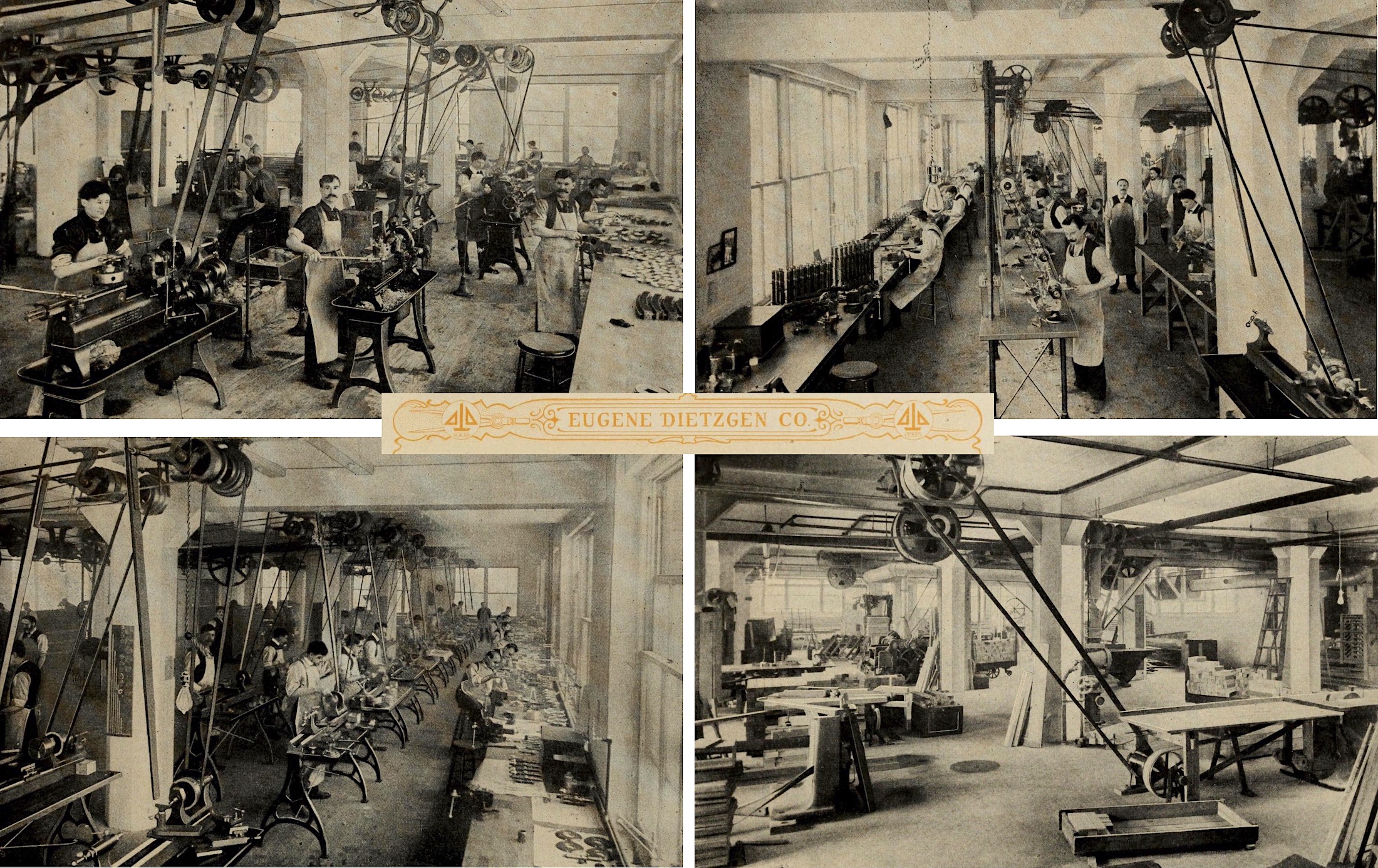

By 1910, with the employee count in Chicago now at 110, the Lincoln Park plant was expanded, and new offices were opened in a half dozen other cities. In a time of regular labor uprisings in the city, Dietzgen also tried to create a working environment more in line with his Socialist ideology—with progressive profit-sharing programs and incentive plans and fairly transparent systems for determining fair wages. There were ample creature comforts, too, like open windows, fresh flowers, and—gasp—separate bathrooms for men and women. Generally, there was also an open door policy to worker feedback.

Inside the Dietzgen Factory, 1907

[Top Left: Machine Shop, Top Right: Telescope Department, Bottom Left: Surveying Instruments Department, Bottom Right: Wood Working Department]

Eugene Dietzgen was rarely the one doing the listening, however. During the early 1900s, he was making regular extended trips back to Germany, and may have spent more time in the company’s Nuremberg factory than the Chicago one. As further evidence of his absentee status, he filed for divorce from his American-born wife Anna in 1912—after 24 years of marriage—supposedly frustrated that she had never borne him a child. Within a year, Dietzgen was married overseas to a much younger German woman named Magdalena.

Based on a passport application he filed in 1915, it seemed that Eugene might have planned to bring his new bride back to Chicago, but it never happened. For one thing, the U.S. Passport office wasn’t too keen on welcoming him back: “Mr. Dietzgen is understood to be a man of large means, erratic and ugly-tempered,” a clerk wrote in a memorandum attached to Dietzgen’s application, noting that Eugene had shown “irritation” when asked to describe his business engagements in Germany, and that his case for returning had “little merit.”

Based on a passport application he filed in 1915, it seemed that Eugene might have planned to bring his new bride back to Chicago, but it never happened. For one thing, the U.S. Passport office wasn’t too keen on welcoming him back: “Mr. Dietzgen is understood to be a man of large means, erratic and ugly-tempered,” a clerk wrote in a memorandum attached to Dietzgen’s application, noting that Eugene had shown “irritation” when asked to describe his business engagements in Germany, and that his case for returning had “little merit.”

This may have all been a moot point anyway. The war was on in Europe, and it would prove far more of a blockade to Eugene’s return than anything the passport office could manage.

III. The German Conflict in the Chicago Factory

World War I stifled the Dietzgen Company’s 30-year run of forward momentum and put it through some of its most difficult trials. Eugene Dietzgen wasn’t there to lead the company, either—the threat of U-boat attacks made Atlantic travel too dangerous, so he had fled (or perhaps just comfortably relocated) to the countryside of neutral Switzerland, where his new wife Magdalena ultimately gave birth to three children during the war and three more in the years after.

Back in the States, Eugene’s younger brother Joseph Dietzgen, Jr.—who’d also spent most of his time back in Germany—managed to put in some hours in the Chicago offices, keeping up appearances. But it was probably vice president R. Fred Allen and treasurer / factory manager William H. Lerch who were left with the big day-to-day challenges.

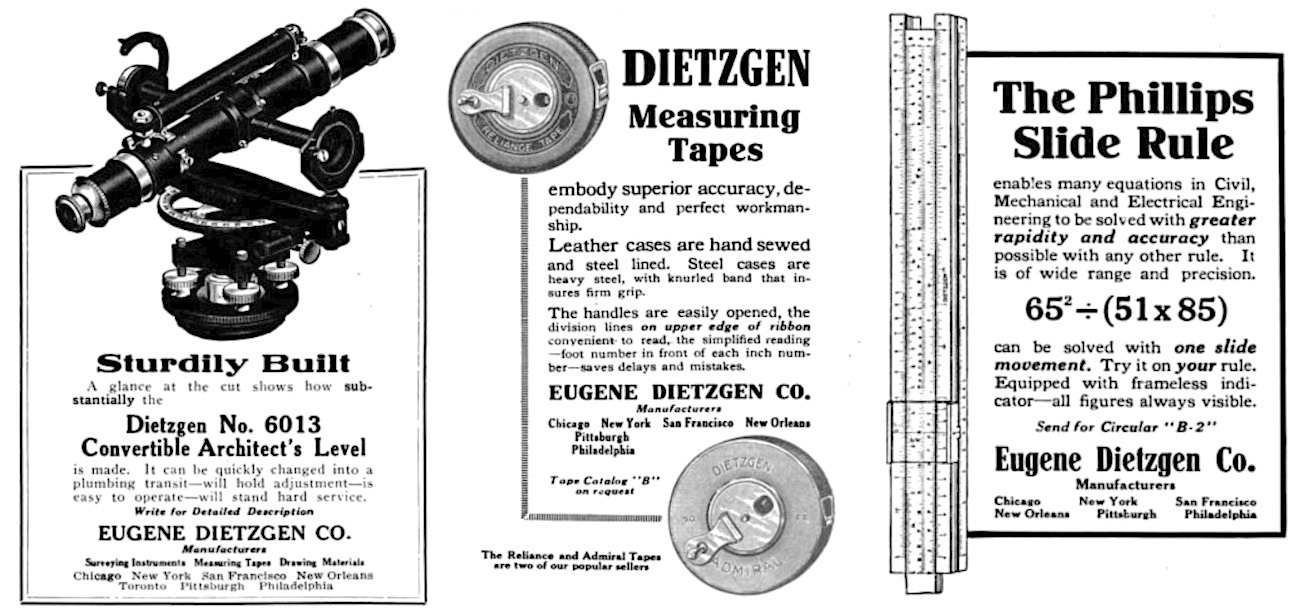

[Three Dietzgen advertisements, each from 1917, covering Architect’s Levels, Measuring Tapes, and Slide Rules]

First and foremost, the company could no longer legally utilize its German factory nor import any instrument parts as it had done for years. Second, in order to prove its patriotic loyalty to the United States, more than 80 percent of production at the Chicago plant had to switch over to military contract work. Between 1917 and 1918, the government ordered more than 35,000 protractors and straightedges from Dietzgen alone, and the company was also a critical producer of mini telescopic alidades and drawing instrument sets—items that had rarely even been made in America previously. “Each instrument set included a pair of proportional dividers,” according to a U.S. War Department report at the time. “The divider, which nearly everyone has seen, appears to be a simple device, yet it must be made with the utmost precision, or else it is valueless. In manufacture it goes through more than 100 distinct factory operations.”

Despite seemingly going above and beyond to “do its part” for the American cause, the Dietzgen Co. couldn’t avoid the anti-German wave moving through the country. Rumors persisted that the company was being “operated from Berlin,” forcing vice president R. Fred Allen to publicly vouch for the absent Eugene Dietzgen, noting that he was naturalized as a U.S. citizen back in the 1890s; that all of the Dietzgen stockholders were American; and that the company’s German factory was no longer under their control.

Despite seemingly going above and beyond to “do its part” for the American cause, the Dietzgen Co. couldn’t avoid the anti-German wave moving through the country. Rumors persisted that the company was being “operated from Berlin,” forcing vice president R. Fred Allen to publicly vouch for the absent Eugene Dietzgen, noting that he was naturalized as a U.S. citizen back in the 1890s; that all of the Dietzgen stockholders were American; and that the company’s German factory was no longer under their control.

There were big problems with the Chicago workforce, as well, as a large number of the plant’s immigrant employees—many of German heritage themselves—complained to the National War Labor Board that Dietzgen was exploiting them, forcing the unnaturalized workers to accept “exceptionally low wages and poor working conditions” or else be accused of obstructing important government work. A letter was even produced in court, supposedly written by Eugene Dietzgen himself, in which he claimed that “the trade unions of America are not up to the pedestal of insight of the German ‘free unions,’ neither in industrial nor political insight. Sad enough we have to reckon with this fact. As far as the threats of the trade union leaders to denounce us, and particularly me individually as an unfair manufacturer, are concerned, if we will not subject ourselves to their experimental whims, we have only as answer the Berliching gesture [i.e., cutting off one’s own hand].”

The war ended just as this bad press was gaining more traction, and by the following spring of 1919, things seemed to have settled down. Then, in the wee hours of the morning on April 29, two safecrackers broke into the Dietzgen offices on Monroe Street and set off an explosive that caused a four-alarm fire and $75,000 in damages. By the following year, the company moved its offices into the Lincoln Park factory and hoped for a full reset as the 1920s began.

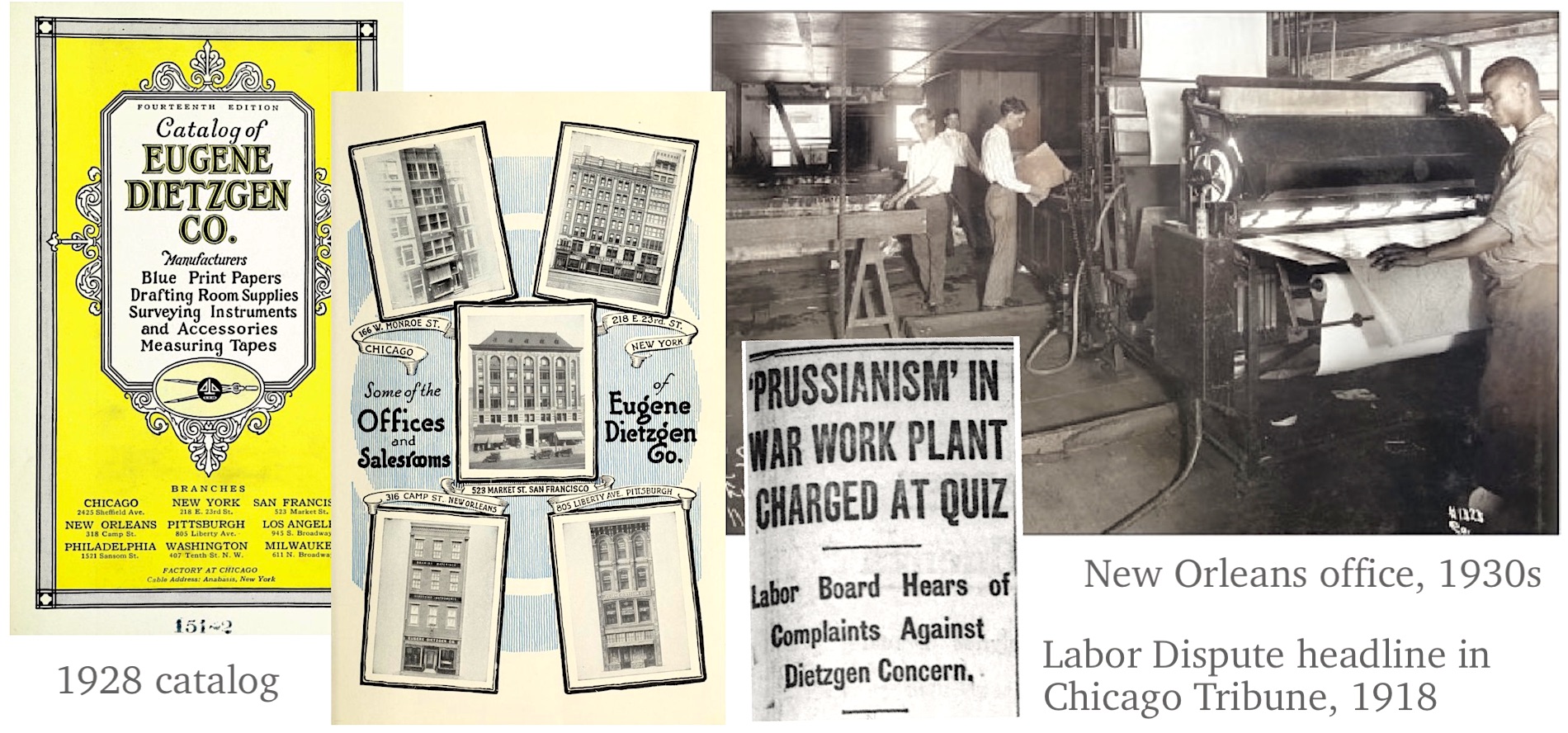

[Left: 1918 Tribune headline during worker uprising at the Dietzgen plant. Middle and Right: Pages from the 1928 company catalog.]

IV. “Handsomely Enameled, Strongly Constructed”

“Dietzgen is a name which has been, is, and will continue to be recognized as representing the highest quality.” —advertisement, 1921

Having dodged potential doom in the 1910s, Dietzgen was back on more level footing in the ‘20s, with its well recognized catalogues serving as the draftsman’s bible. Leadership was stabilizing, too, as William Lerch took over the company presidency, and a Romanian-American inventor named Adolph Langsner (1880-1967) began a long and prolific tenure as chief engineer.

Later in life—along with serving as a Major in the army—Langsner became an esteemed academic and a professor of industrial management at Northwestern University, specializing in the subject of worker pay. His most influential essay, Wage and Salary Administration (1961, co-written with Herbert G. Zollitsch) was personally dedicated to the memory of Eugene Dietzgen, whom Langsner refers to as a “leader in business organization and a pioneer in the field of adequate and equitable compensation.”

Later in life—along with serving as a Major in the army—Langsner became an esteemed academic and a professor of industrial management at Northwestern University, specializing in the subject of worker pay. His most influential essay, Wage and Salary Administration (1961, co-written with Herbert G. Zollitsch) was personally dedicated to the memory of Eugene Dietzgen, whom Langsner refers to as a “leader in business organization and a pioneer in the field of adequate and equitable compensation.”

When Dietzgen hired him to run the Chicago factory in the 1920s, Langsner was a bit more interested in machines than the humans who ran them. He saw standardization as the new frontier in running profitable manufacturing businesses. “The present unusual condition of high labor cost and low price of manufactured article can be met only by interchangeability of parts,” Langsner wrote in a 1925 edition of the The Society of Industrial Engineers Bulletin. That mindset helped the Dietzgen Company move further away from its somewhat elitist roots into more of a 20th century style of mass production.

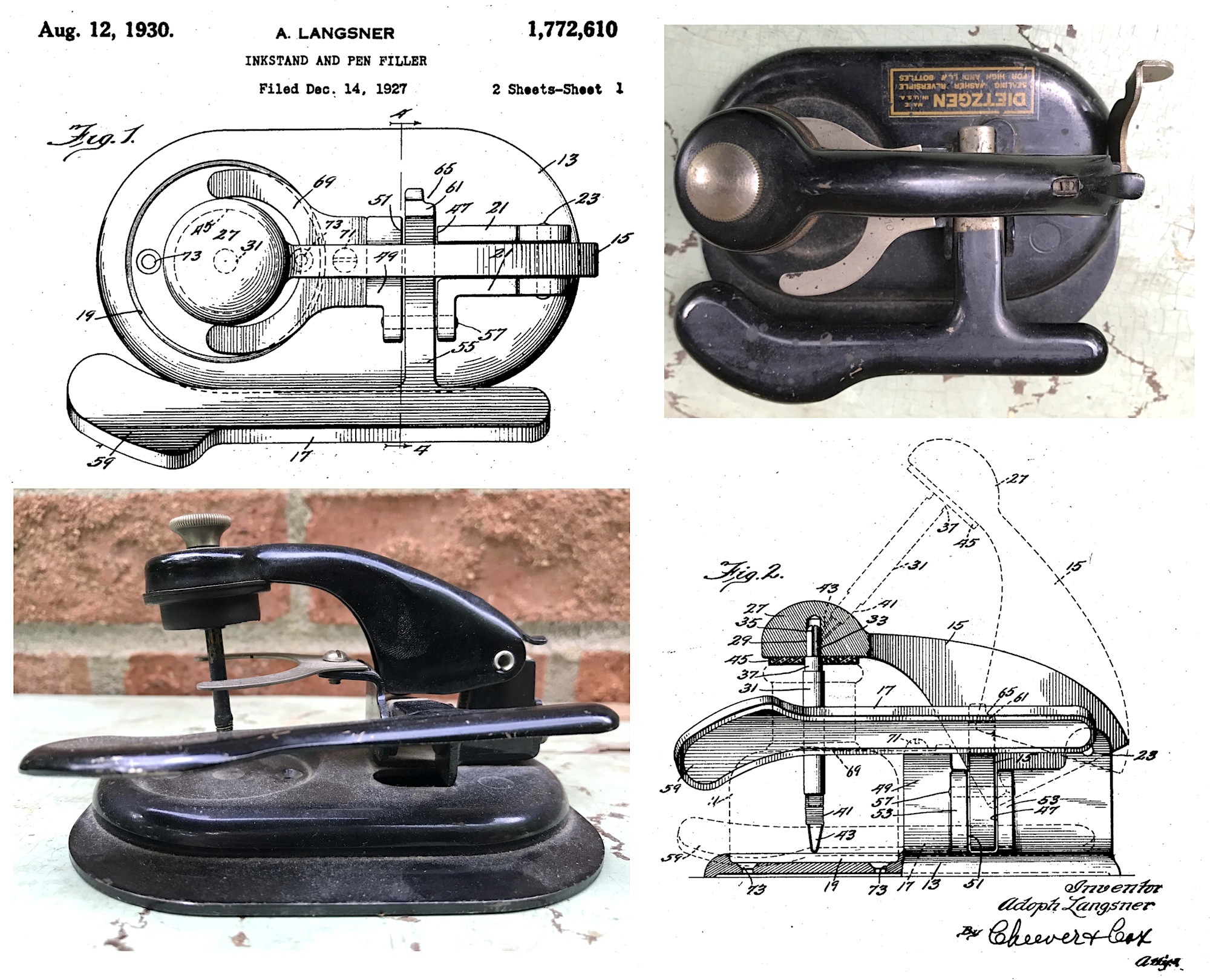

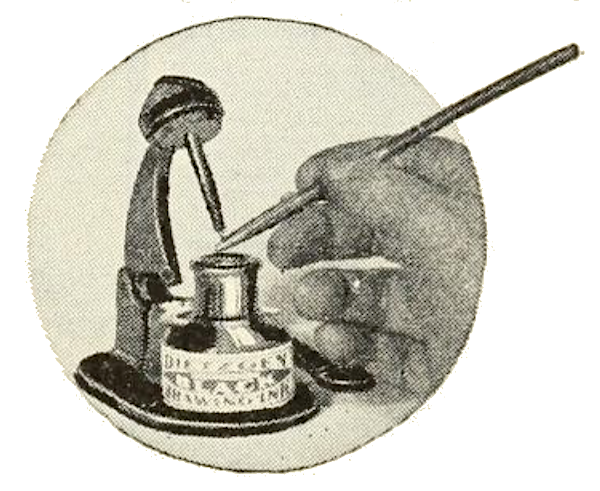

Langsner knew machines because he was, first and foremost, a mechanical engineer—and across a 20-year career with Dietzgen, he collected no less than 90 separate patents for his own inventions, ranging from an eponymous brand of slide rule to various advances in levels, telescopes, measuring tape reels, and even a rather snazzy “inkstand and pen filler” device—as seen in our museum collection.

[Adolph Langsner’s original 1927 patent drawing for the Handy Pen-Filling Ink Stand, and the example from our museum collection]

“This Handy Pen-Filling Ink Stand is made to hold a 3/4 oz. bottle of drawing ink,” a Dietzgen catalog described the little device, which Langsner filed a patent on in 1927. “The arm which holds the dipper can be opened from any angle by a slight pressure of the finger upon the tipper bar. With the pen held as when ruling a line, the bar is depressed and the pen is brought directly under the dipper.

“The whole operation is easily performed with one hand. The automatic stopper fits closely over the mouth of the bottle and prevents evaporation. Handsomely enameled, strongly constructed and of sufficient weight to prevent tipping.”

“The whole operation is easily performed with one hand. The automatic stopper fits closely over the mouth of the bottle and prevents evaporation. Handsomely enameled, strongly constructed and of sufficient weight to prevent tipping.”

Advances in ink pen technology would make the whole dipping function obsolete in due time, but such was the nature of the business. Nothing lasted forever.

The rule applied even to the mighty Eugene Dietzgen himself, who died in Switzerland in 1929, aged 67. His widow, Magdalena, responded by sending her young sons—Joseph, Eugene Jr., and Walter—to America, with the idea that the family business would soon pass into their hands.

V. Constant Companions of America’s Heroes

“Quality is heritage at Dietzen. Since our inception over a half century ago, we have adhered faithfully to the policy of the founders. ‘Enduring Worth at Reasonable Cost.’ This policy has earned a wealth of friends in every part of the world. It has made the name Dietzgen synonymous with quality and honest value everywhere.” —Dietzgen catalogue, 1938

While William Lerch, Adolph Langsner, and the rest of the Dietzgen factory team did their best to keep the business chugging along during the Depression, the next generation of the Dietzgen family was preparing to enter the picture.

Eldest son Joseph, born in 1917, arrived from Switzerland at the age of 20, and promptly enrolled at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, graduating in 1941 as a fully formed engineer. Youngest brother Walter went to Harvard himself. It’s not clear if Eugene Jr. earned a degree, but all three brothers served their new country in some capacity during World War II (Joseph in the Navy, Eugene and Walter in the Army), looking very much like the flag-waving sons of a Chicago industrialist rather than life-long Swiss socialists.

Eldest son Joseph, born in 1917, arrived from Switzerland at the age of 20, and promptly enrolled at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, graduating in 1941 as a fully formed engineer. Youngest brother Walter went to Harvard himself. It’s not clear if Eugene Jr. earned a degree, but all three brothers served their new country in some capacity during World War II (Joseph in the Navy, Eugene and Walter in the Army), looking very much like the flag-waving sons of a Chicago industrialist rather than life-long Swiss socialists.

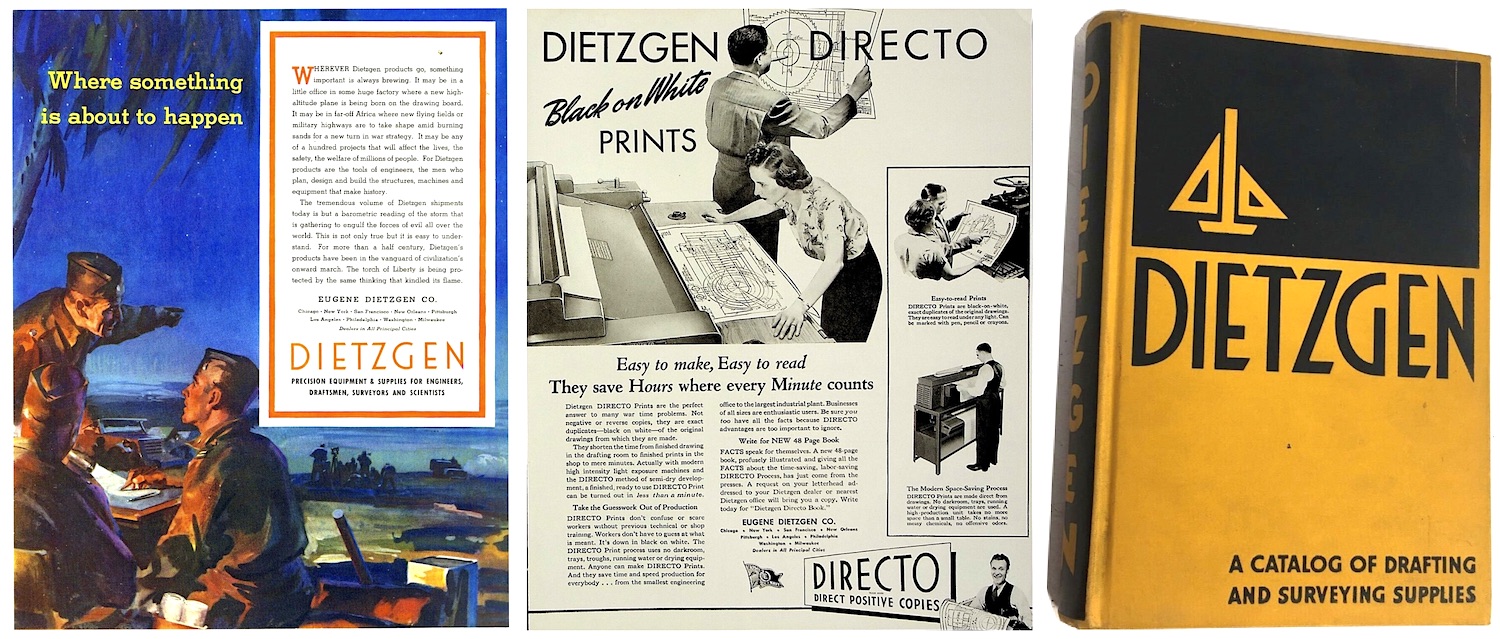

The Dietzen Company, similarly, avoided much of the blowback it had experienced during the first war with Germany, as its government contracts during WWII earned the factory a load of cash and goodwill, as well as an Army-Navy “E” Award in 1943 for outstanding contributions to the Allied cause.

“In this day of highly mechanized warfare,” read a full-page Dietzgen ad that year in Fortune magazine, “it is the proud privilege of Dietzgen instruments to be the constant companions of many of America’s heroes. . . . Quite naturally, we of Dietzgen find great inspiration in this knowledge of important service.”

[Left: 1942 wartime ad, Center: 1943 ad for Dietzgen’s DIRECTO “Direct Positive Copy” prints, Right: 1949 Dietzgen catalog]

Joseph Dietzgen started working at the Chicago plant shortly after leaving MIT, and soon replaced Adolph Langsner as the main brain in research and development, along with chief engineer Edward Lockett. In 1952, Joseph was elected the new company president, with William Lerch moving up to the role of chairman.

By 1960, the company employed about 1,500 people and had annual sales over $25 million, or about $230 million after inflation. When the Tribune ran a feature that year on Dietzgen’s 75th anniversary, the article noted that, “in the eyes of Joseph Dietzgen, president and son of the founder, the company’s aims relate to this country’s progress and buildings, tools, products, and transportation systems surrounding it—all from the point of view of the engineering and design behind it.”

For an old business rooted in the 1800s, the messaging was more in line with the forward-thinking spirit of the Space Age. “The growing economic and social needs of a distending population cannot be met by horse-and-buggy solutions,” read a 1956 advertisement. “Wherever you find engineers you know the routines of yesterday won’t be repeated, it won’t be ‘more of the same,’ it will be ‘better’ and ‘better’ and ‘better’ until the end of time. You won’t find ‘more of the same’ at Dietzgen either.”

For an old business rooted in the 1800s, the messaging was more in line with the forward-thinking spirit of the Space Age. “The growing economic and social needs of a distending population cannot be met by horse-and-buggy solutions,” read a 1956 advertisement. “Wherever you find engineers you know the routines of yesterday won’t be repeated, it won’t be ‘more of the same,’ it will be ‘better’ and ‘better’ and ‘better’ until the end of time. You won’t find ‘more of the same’ at Dietzgen either.”

Dietzgen had racked up no shortage of innovations across the decades, from introducing Van Dyke, Perma-Scale and Micro-Fax products to helping to bring the dry-diazo process and polyester drafting films to the U.S. Some of these developments were dreamed up in-house, others came from keeping an ear to the ground. “Research costs come high,” Joseph Dietzgen said in a 1963 lecture at the Illinois Institute of Technology, “yet there are many successful products today that were picked up as bargains because the original researcher was premature and ran out of money.”

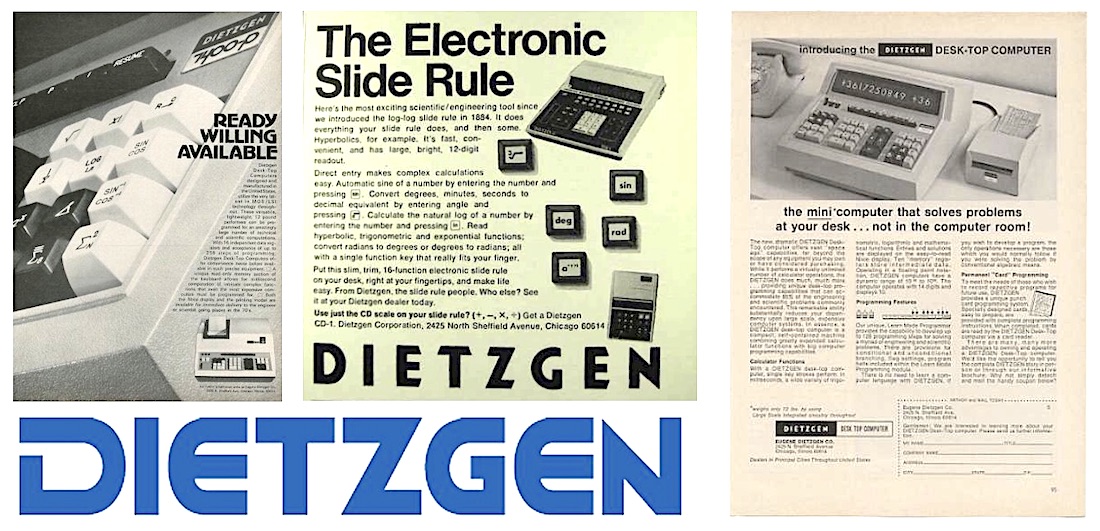

Joseph Dietzgen’s talent for looking forward might have also led to his decision to sell his father’s business when the situation looked optimal. In 1971, he and his brother Walter Dietzgen, vice president, sold their stock to the Rock Island Corporation of St. Paul, Minnesota, which then took over the Chicago factory and Dietzgen’s 40 national sales offices. During this same period, Dietzgen was trying to make inroads in the electronics market, promoting its own electronic slide rule and even an early desktop computer. But they never became a strong player in that field.

Renamed the Dietzgen Corp., the company ultimately left the Lincoln Park plant in 1976 (the building became an A&P store for a few years after), moving to a modern facility at 250 Wille Road in suburban Des Plaines. Paper and film coating were its biggest concerns during the ‘70s and ‘80s. The Nashua Corporation of New Hampshire bought out the business in 2002, and Precision Paper, Inc. did the same in 2012, re-establishing Dietzgen as a Florida-based logistics and supply chain management brand . . . with barely any connection to its origins.

[Ads from the early 1970s, showcasing Dietzgen’s efforts to break into the early desktop computer market]

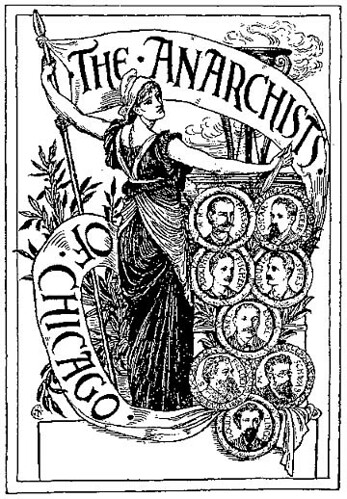

Postscript: The Socialist’s Capitalist Conundrum

Way back at the dawning of the Dietzgen Company, in 1888, founder Eugene Dietzgen and several of his siblings—all living in Chicago—encouraged their father Joseph, the socialist scribe, to do the same. The old revolutionary complied, but he wasn’t ready for a quiet retirement in America, either. Instead, Joseph took an active role as an editor for several Socialist publications, and—stirring controversy even within his own party—he used that position to offer support and sympathy to August Spies and the other anarchist labor activists behind Chicago’s Haymarket Square bombing in 1886 . . . perhaps not the kind of publicity that was going to help Eugene sell his slide rules and protractors.

And yet, over time, Eugene Dietzgen only came to hold his father—and his teachings—in higher esteem, recognizing the “just pride of his true convictions,” as he later described it. Of particular importance to Eugene’s own circumstance, as an employer, was the notion that workers within the free American democracy were really no different than the oppressed proletariat back home in Europe.

And yet, over time, Eugene Dietzgen only came to hold his father—and his teachings—in higher esteem, recognizing the “just pride of his true convictions,” as he later described it. Of particular importance to Eugene’s own circumstance, as an employer, was the notion that workers within the free American democracy were really no different than the oppressed proletariat back home in Europe.

“If this is not yet well recognized in the United States,” Joseph wrote to his son, “it is due more to the fortunate natural resources of that country than to the scientific insight of its democracy. The spreading primeval forests and prairies offered innumerable homesteads to the poor and glossed the antagonism between capitalists and laborers, between capitalist and proletarian democracy. But you still lack the knowledge of proletarian economics which would enable you to recognize without a doubt that precisely on the republican ground of America, capitalism is making giant strides and revealing ever more clearly its twofold task of first enslaving the people for the purpose of freeing them in due time.”

On a spring day in 1888, Eugene accompanied his father on a pleasant walk in Lincoln Park, followed by some wine, a meal, cigars, and an animated political conversation with a young, slightly antagonistic friend. Eugene later recalled that he’d never seen his father behave with more vivacity. “With a seriousness and emphasis which I shall never forget,” Eugene wrote, “[my father] related that he had foreseen the modern labor-movement forty years before this date, and proceeded to explain his views on the imminent collapse of capitalist production, when suddenly he stopped in the middle of a sentence, with his hand uplifted, and fell into my arms, breathing his last. He was not quite sixty years old.

“Simply and without any show, in harmony with the character of my father, we buried him by the side of the murdered anarchists in Forest Home Cemetery near Chicago, on April 17, 1888.”

[Eugene Dietzgen helped edit many of his father’s published works, including the Positive Outcome of Philosophy. Joseph Dietzgen was memorialized with a stamp in East Germany in 1978, as seen above.]

For many years after, Eugene Dietzgen—when not building his business—spent much of his time and money securing Joseph Dietzgen’s legacy. This included translating, publishing, and promoting Joseph’s works and letters, and helping to affirm his father’s status as one of the architects of the key Socialist concept of dialectical materialism. Eugene was active in Chicago’s Socialist circles himself, but perhaps unsurprisingly, that part of the company lore was well concealed, especially as anti-Communist and anti-German sentiments grew in the 20th century.

This may also explain why the current official website of the Dietzgen Corporation has one of the silliest corporate timelines you’ll ever see: jumping from bullet point No. 1, the founding of the company in 1885, straight to bullet point No. 2: the establishment of its current parent company Precision Paper, Inc., in 1990 . . . 105 years later. I guess nothing that happened to Eugene Dietzgen and his pals in that century-long interim was worthy of a bullet point, but we decided to tell the tale anyway.

[The expanded Dietzgen factory complex at Fullerton and Sheffield, as it looked in the 1940s]

Sources:

Eugene Dietzgen Co. catalogs – 1907, 1910, 1921, 1928, 1938

“Sudden Death of Joseph Dietzgen” – Arkansas Democrat, April 21, 1888

“Joseph Dietzgen: A Sketch of His Life, by Eugene Dietzgen” – Some of the Philosophical Essays on Socialism and Science, Religion, Ethics, Critique-of-Reason, and the World-at-Large, by Joseph Dietzgen, 1906

“Joseph Dietzgen and Henry George” – International Socialist Review, Vol. 9, 1908-09

“Prussianism in War Work Plant Charged at Quiz” – Chicago Tribune, Oct 8, 1918

“Show Record of Men’s Advocate in Strike Case” – Chicago Tribune, Oct 23, 1918

America’s Munitions: 1917-1918, U.S. War Department, 1919

“Safe Blowers Start Loop Fire; $75,000 Loss” – Chicago Tribune, April 29, 1919

“Modern Gaging Practice (Review by Adolph Langsner)” – Society of Industrial Engineers Bulletin, Vol. 7, No. 7, 1925

“3 Illinois Firms to Get Army-Navy E Awards” – Chicago Tribune, June 29, 1943

“Dietzgen Combines Past, Future” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 27, 1960

“Diversification Ace Lists Successful Rules” – Chicago Tribune, April 2, 1963

“Engineers Will Hear Dietzgen” – Orlando Sentinel, May 8, 1964

“The Dietzgen Company” – Journal of the Oughtred Society, Vol. 5, No. 2, October 1996

“Vera Dietzgen Feldmann on Josef Dietzgen and the Dietzgen Family” – project by Josh Morris, UC Santa Barbara, 2008

Thanks for this very interesting article. I cherish my father’s Dietzgen horsehair drafting brush that he used while drafting for the Martin Marietta CO in 1939.

I have a solid brass Eugene Dietzgen – Chicago surveyors level w/ original wooden box. I believe the level works and I have done my best to polish it. It is numbered “111”. I am trying to determine about what year this device was made, and curious to know if the museum might be interested in this piece. Thank you in advance, Alan (San Diego)

I have a vintage Pocket Transit Compass that bears the Makers mark of Dietzgen and also includes the city names of Chicago and New York. In my research I can find no other Pocket Transit Compass made by Dietzgen. They are all made by Brunton (original inventor) or William Ainsworth who started manufacturing and selling these transit compasses by Brunton. It is vintage and I am guessing made 75 – 100 years ago. Would you have knowledge of this item or where I can turn to find more information. I am guessing that it is rare as I can find no other examples of this compass.

Any help or insight will be appreciated.

Thank you

Mr. Clayman,

Excellent article on the Eugene Dietzgen Co.’

I am looking for information on a Dietzgen wooden drafting table, and have sent off a letter to them thanks to your article.

Great job !

Respectfully,

Ron Scott

I was given as a gift a 12×4 leather case w green felt with12 drawing instruments and paper insert with Eugene Dietzgen co. Printed on it along with the printed alphabet and numbers 1-10 on it. Is this rare?

I have found old thumbtacks in the box still. Model number 2443-2.

Made by Dietzgen.

Can’t find anything on them. Can someone give me more info?

I was given a large Beck file with the Hene Dietzgen label on it. It’s about 4.5 feel wide about 4 feet tall and 7 inches deep. I have all the hanging folders for it. I’m hoping to get some more information on value

I have a beautiful adjustable drafting table with the Eugene Dietzgen Co Metal tag on it and I’d love to find out when it was made. It is almost entirely made of wood except for the tag and the tips of the legs and arms and the hardware nails etc. Does anyone know ho to date it or even better have any catalog pages of the drafting tables they made? Did they sell tables or was this from the factory? My table is also stamped with the name of a well known civil engineer who worked on many famous buildings in San Francisco so he obviously had the table for some time.

Hi, I recently acquired an interesting but curious Dietzgen item and do not know what it is. I presume something for engineering, surveying, or drafting but I am at a loss. A nicely crafted and hinged wooden box 49″ long x 6 1/2″ wide x 3 1/2″ deep, contains 4 odd ingots, weights, or measures (?) that leave me clueless. They are lead, or at least are nonmagnetic, painted black, with green felt on the bottom. They are for lack of a better thought, sort of “whale”-shaped from a side view or “fish-shaped” from a top-down or bottom-up view. They are 6 1/2″ long and 2 7/8″ at their top height, down to about 5/8″ at the “tail” end and of the “whale” and 1 5/8″ wide at their widest down to 1 1/2″ at the “tail”.(Sorry for the very odd description but I can email pictures which are worth much more than a thousand words.) Last there is an odd ”hook” at the “nose” of the item – a 1 3/8” long x 1/8” wide metal appendage coming out and bending down with a machined flattened tip that would be like a flat head screwdriver about 3/16” long and wide. They weigh a hefty 3 ½ lbs. each! The 4 lead items sit in a removable wooden insert in the base, flush to the inside of the case, with 4 cutouts that are shaped like the items. This storage piece was obviously built to hold these but was also made with grooves in the wood except where the cutouts exist. The lid of the case has 4 wooden stretchers that are covered with green felt that when the lid is closed would further secure atop the items, and the case has two gate latch hooks on the facing of the case that secure into a round wood screw top to keep the case closed. Last, there is a small brass stamped nameplate with the name Dietzgen and below that the compass logo and the words Trade Mark. Below that is a line of city names Chicago New York San Francisco New Orleans and on the last line Pittsburg Philadelphia Washington. Again, my apology for the perhaps overly vague and oddly detailed description, but I do have pictures I could email. I would be very grateful if anyone knows what purpose this mystery tool served and possibly the era in which it was used? My very sincere thanks in advance for any information.

Bill Sherriff

Have you since learned anything about this apparatus? I have a similar case/frame, larger, with metal springs that compress the back closure of the case to its glass front. No ingots. My guess is these two items are/were used for blueprint reading/handling. The ingots simply as paperweights when blueprints would be fully spread; the press box to flatten out prints that had heretofore been rolled or creased.

My grandfather was Jerome John dietzen of CHICAGO HE WAS A STEEL WORKER HIS DAD MY GREAT GRANDFATHER WAS TONY DIETZEN! ITS A LONGSHOT BUT STILL CURIOUS IF I’m any relation to EUGENE .CAUSE I REMEMBER MY DAD IN PASSING TELLING ME THE DIETZEN NAME WAS NOT THE ORIGINAL SPELLING

Dietzgen Inkstand 8-12-1930 US1772610

https://patents.google.com/patent/US1772610A/en?oq=US1772610

As the son of Virgil Dorstewitz the developer and manufacturer of tjhe Tru Point Pencil Lead Pointer which Dietzgen called the Shar-Point I am writing a hisory of the company. Dietzgen Co. was the first to take on the Tru Point (Shar-Point) in the early 1950’s.If you could supply me with any information such as the buyer at the time, etc. it woiuld be most appreciated. I remember that Dietzgen had a warehouse in Elkhart, IN and you would send your truck to our factory in Coloma, Mi to pick up your shipment. Deitzgen was the first buyer of the Pointer and played a significant part in its success.

Hi Robert, this website is an online museum about Chicago industrial history. We aren’t affiliated with the original Dietzgen company in any way, so unfortunately we don’t have access to internal company information related to their buyers or connection with Tru-Point / Shar-Point.

Hello. I have recently come i to possession of this very beautiful piece of work. I am looking for some info on this ink stand. With this item came a huge box of related items. I would like to gain perspective by hearing the creator’s insights if at all possible along with the value of this piece. Its in perfct condition along with its original manufacturer’s box. Thank you so much for your correspondence.

PAT.1.772.610

No.2745

Eugene Dietzgen Co.

Patent