Museum Artifact: Dormeyer Orbital Electric Sander, c. 1950s

Made By: The Dormeyer Corporation, 700 North Kingsbury St., Chicago, IL [River North]

“Your Dormeyer Sander is so well balanced in design and so light in weight that you can use it for hours without fatigue. Just let the sander do the work!” —Dormeyer Power Tools Instruction Manual, c. 1956

The A. F. Dormeyer Manufacturing Company is best remembered as a key player in the early days of electrical home appliances. As one of the first firms to perfect the motorized kitchen mixer, they both inspired and competed against their local rivals at the Chicago Flexible Shaft Company (aka Sunbeam) for dominance in that arena. While the Sunbeam MixMaster became iconic, though, the fortunes of the family-owned Dormeyer business were complicated by strategic missteps and bad backroom deals, culminating in the bizarre post-war exile of the company’s own namesake, Albert F. Dormeyer, and the eventual simultaneous existence of two separate, contentious entities: the Dormeyer Corporation (the original business, founded in 1912) and Dormeyer Industries (Albert Dormeyer’s second electronics firm, founded in 1946).

The A. F. Dormeyer Manufacturing Company is best remembered as a key player in the early days of electrical home appliances. As one of the first firms to perfect the motorized kitchen mixer, they both inspired and competed against their local rivals at the Chicago Flexible Shaft Company (aka Sunbeam) for dominance in that arena. While the Sunbeam MixMaster became iconic, though, the fortunes of the family-owned Dormeyer business were complicated by strategic missteps and bad backroom deals, culminating in the bizarre post-war exile of the company’s own namesake, Albert F. Dormeyer, and the eventual simultaneous existence of two separate, contentious entities: the Dormeyer Corporation (the original business, founded in 1912) and Dormeyer Industries (Albert Dormeyer’s second electronics firm, founded in 1946).

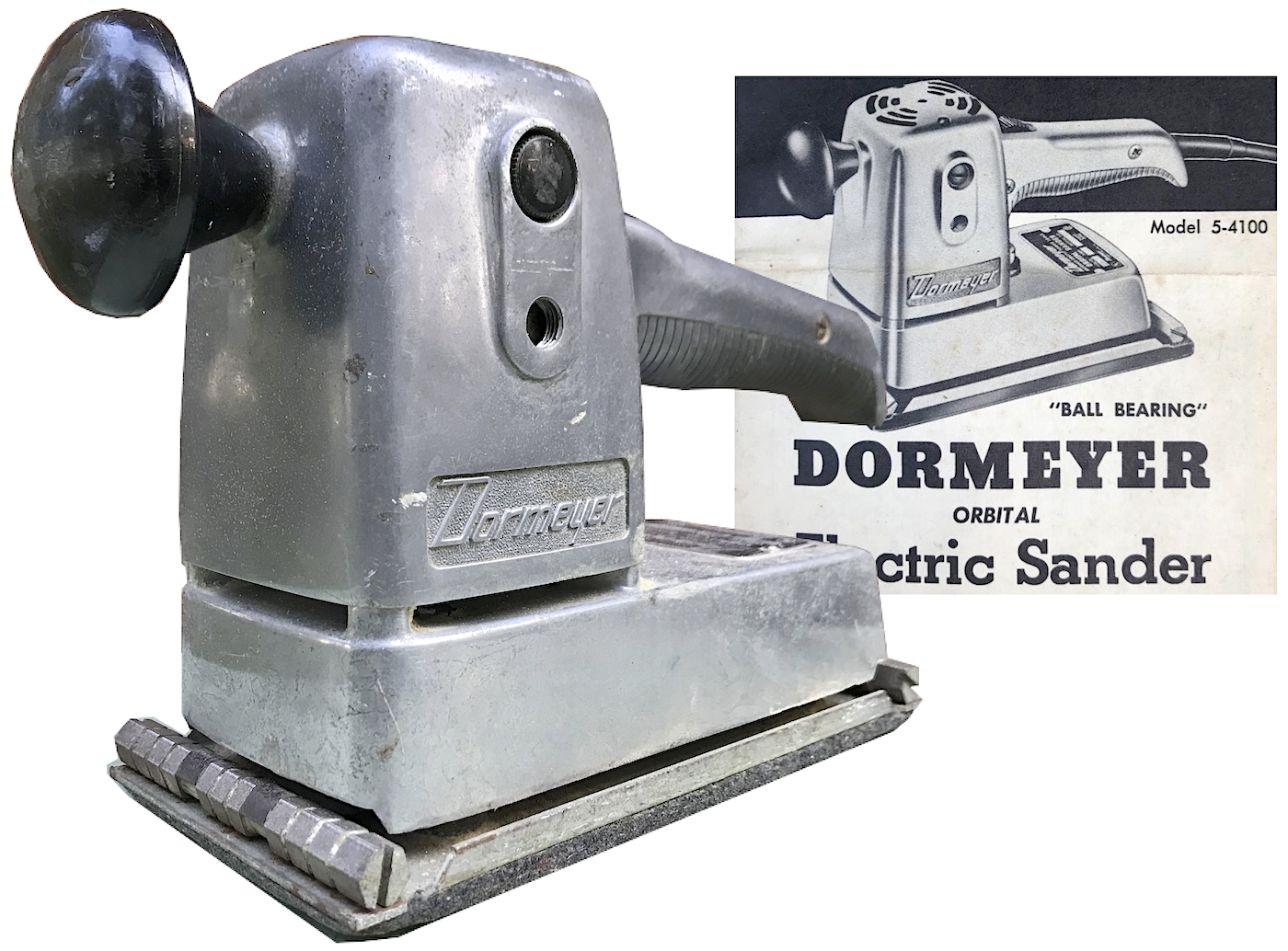

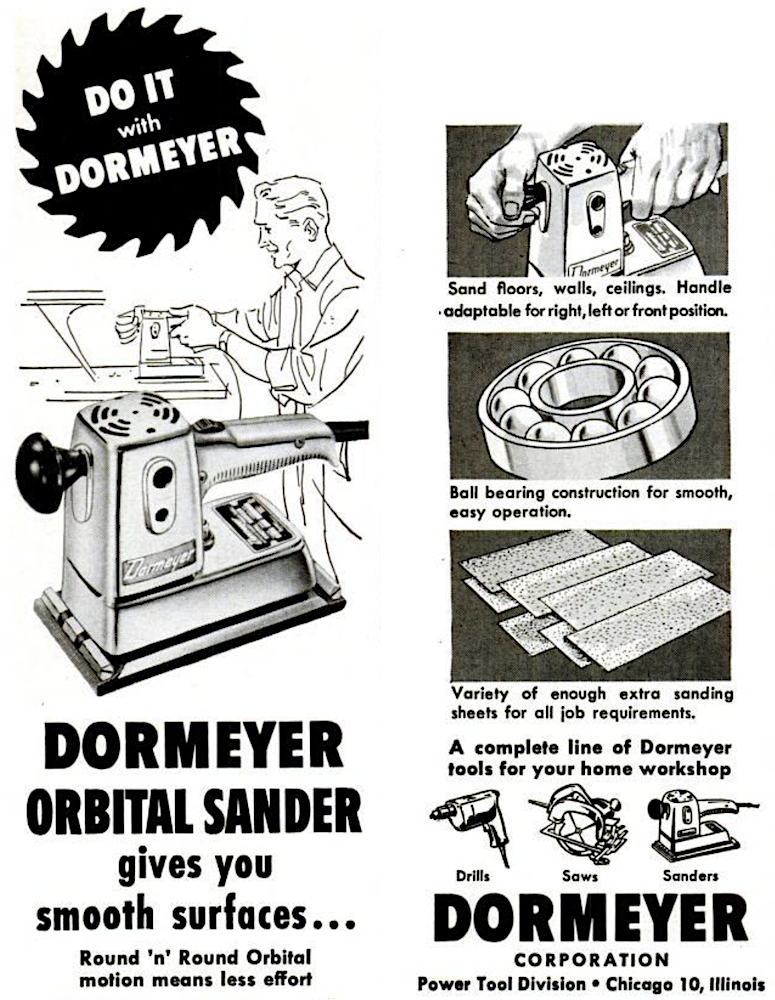

The artifact in our museum collection—a space-age Orbital Sander with a “cog belt drive, ball-bearing construction, die-cast polished aluminum housing, and slide button switch”— was a product of the Dormeyer Corporation, and represents that company’s ambitious expansion into the power tool market during the 1950s. At this stage, despite the name on the sign, the business had become a glossy reflection of its new owner and executive vice president Titus Haffa—a jet-setting, millionaire industrialist who’d come to power after (arguably) swindling the Dormeyer family out of their nest egg back in 1944.

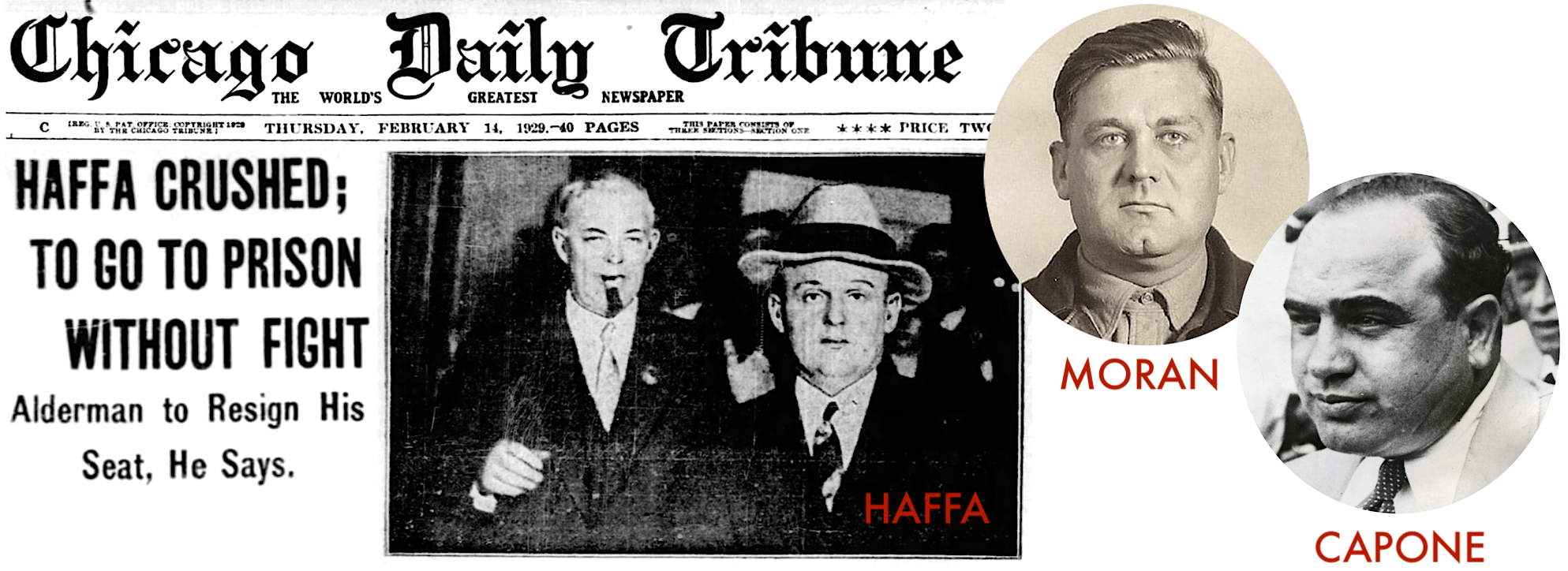

Chicagoans knew Haffa well. Back during Prohibition, while serving as the Republican alderman of the 43rd Ward, he’d used his power to operate his own criminal bootlegging syndicate; rubbing shoulders with gangsters like Bugs Moran. Finally busted by the Feds, Haffa stood in a courtroom on February 13, 1929, where he was handed down a two-year sentence in Leavenworth Penitentiary. The very next day, when the infamous St. Valentine’s Massacre left seven of Moran’s men brutally slain in a Lincoln Park garage, some theorized that Al Capone had ordered the attack as a direct power play following Haffa’s downfall.

[On Valentine’s Day, 1929, the conviction of bootlegging alderman and future Dormeyer Corp. president Titus Haffa was front page news in the Chicago Tribune. Perhaps as no coincidence, the infamous St. Valentine’s Day Massacre occurred just hours after the paper hit the presses, with Al Capone allegedly hitting back at Haffa associate Bugs Moran. The Tribune photo above shows Haffa being taken out of court by U.S. Dept. Marshall Roy Holcomb. Before sentencing him to 2 years in federal prison, Judge Walter C. Lindley called Haffa’s actions “grievous and horrible” and a betrayal of his elected duties as a “trustee of the people.”]

Ever redeemable in the local political tradition, of course, Titus Haffa re-emerged after 17 months behind bars, and soon became a celebrated figure of post-war capitalist opulence, with the Dormeyer Corporation as one of several jewels in his crown.

Unsurprisingly, the tiger hadn’t truly changed his stripes, and Haffa’s further flirtations with corruption led to more dire consequences—if not for himself, then certainly for his employees.

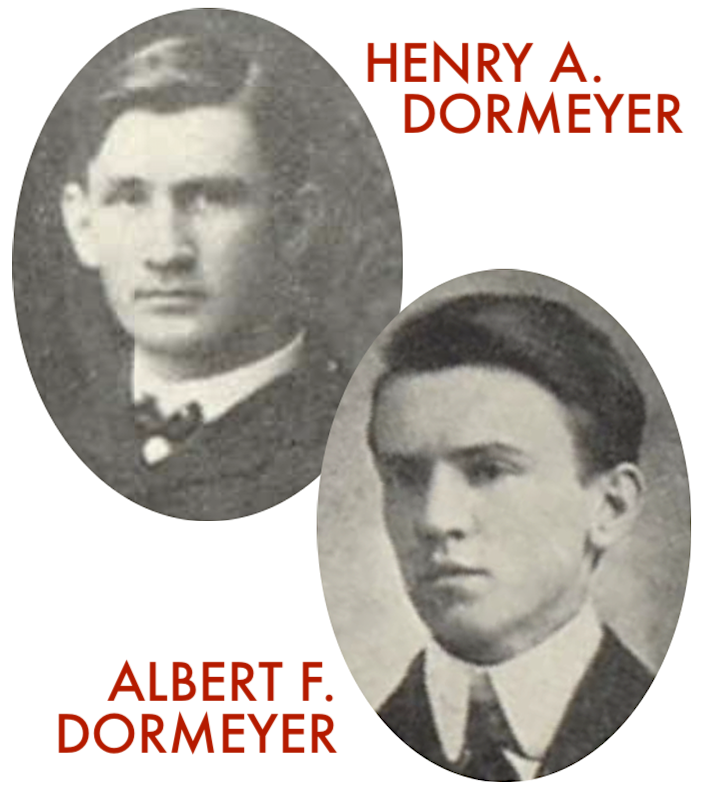

In something akin to “vengeance,” I suppose, the ousted Albert F. Dormeyer eventually lived long enough to see his second business outlive the one he’d lost. But looking at all the facts, it’s hard to say that he is really the hero of this story either. If anything, it was a different Dormeyer—Albert’s older brother Henry—who deserves some overdue credit; not to mention the hundreds of employees who brought Dormeyer appliances to the world.

[Photo of workers outside the Dormeyer factory at 4300 N. Kilpatrick Ave., c. 1946. Donated by Fritz and Fay Michaelis. Fritz’s uncle Otto Michaelis immigrated to Chicago from Germany in 1927 and became a longtime product developer with Dormeyer]

History of the Dormeyer Corp., Part I: Get Off of My MacLeod

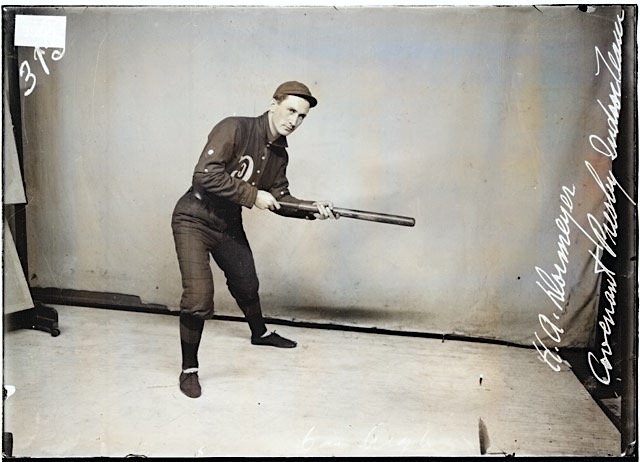

Henry A. Dormeyer was born in Athens, Wisconsin, in 1886, and was followed shortly thereafter by his brother Albert in 1888. They were the first of six children born to fresh-off-the-boat German immigrants Herman Dormeyer, a farmer, and Emilie Dormeyer. In an extreme rarity for both the time and place, though, Herman and Emilie divorced at some point in the 1890s, leaving Henry and Albert as the obligatory “men” of the house at a very young age.

Against the odds, the Dormeyers pulled off the whole “American Dream” thing in relatively short order. Both Henry and Albert excelled as students at Merrill High School, and as ambitious young lads, they soon sought their fortunes in the wider world. Henry, as the eldest son, moved to Chicago and brought along his mother and several younger siblings, supporting them by working his way up to an office manager position with the Bottlers Machinery Company. By contrast, Albert took a more independent route, trying his luck as a lumber merchant in Iowa.

Against the odds, the Dormeyers pulled off the whole “American Dream” thing in relatively short order. Both Henry and Albert excelled as students at Merrill High School, and as ambitious young lads, they soon sought their fortunes in the wider world. Henry, as the eldest son, moved to Chicago and brought along his mother and several younger siblings, supporting them by working his way up to an office manager position with the Bottlers Machinery Company. By contrast, Albert took a more independent route, trying his luck as a lumber merchant in Iowa.

In fact, counterintuitively, it was Henry Dormeyer who actually organized the business that would later become the Albert F. Dormeyer Company. Around 1912, at the age of 26, Henry split off from the Bottlers Machinery Co. to establish his own small factory, known as the Boscal Company. Two years later, he joined forces with the upstart MacLeod Manufacturing Company, a small-scale producer of “janitor’s supplies, tools, dies, and special machinery. As MacLeod’s go-getter general manager, Henry helped the business flourish.

“The MacLeod MFG Co., manufacturers of Superior Window Cleaners, Floor Rubbers and Mop Wringers, has moved into their new factory at 412 and 420 Orleans Street, Chicago, where they are getting twice the floor space they formerly had,” the House Furnishing Review reported in 1916. “The demand, especially for Window Cleaners, has been so great this year that it was impossible for them to produce sufficient goods, even by working overtime and to full capacity, to supply their trade. Under the new conditions they fully expect to be able to take care of all orders promptly and be prepared for a growing demand.”

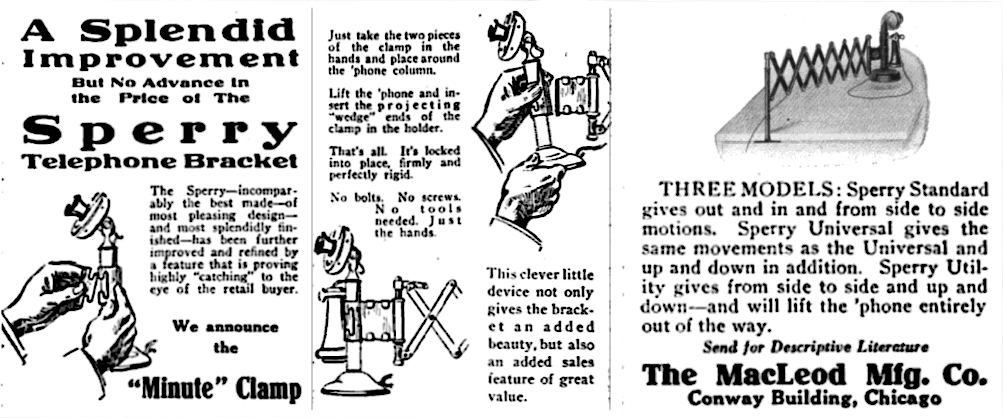

[1918 advertisement for the Sperry Telephone Bracket, a new product that MacLeod MFG acquired and began producing around this time]

By 1918, while kid brother Albert was still out pushing lumber in the Great Plains, Henry Dormeyer had helped MacLeod Manufacturing transition from cleaning supplies to telephone accessories, as the company’s “Sperry Telephone Bracket” earned them an affiliation with the Kellogg Switchboard & Supply Company and a couple more moves into larger factory spaces—starting with the Conway Building downtown, then a dedicated space at 2640 N. Greenview Avenue in Lincoln Park. Here, throughout the early 1920s, Henry Dormeyer remained the president and general manager of the MacLeod enterprise, and with the MacLeod family no longer connected to the business, an eventual name change seemed in store.

The question is, how did MacLeod MFG wind up becoming the A. F. Dormeyer MFG Co. rather than the H. A. Dormeyer MFG Co.?

Well, the details remain a tad hazy there. At the outset of the 1920s, 32 year-old Albert Dormeyer was settling into his life in Iowa. He was still employed in the lumber trade and had started a family with his wife Daisy. There was no indication that he had any involvement in his brother’s business back in Chicago. What Albert was doing, however, was pursuing a budding talent for mechanical engineering.

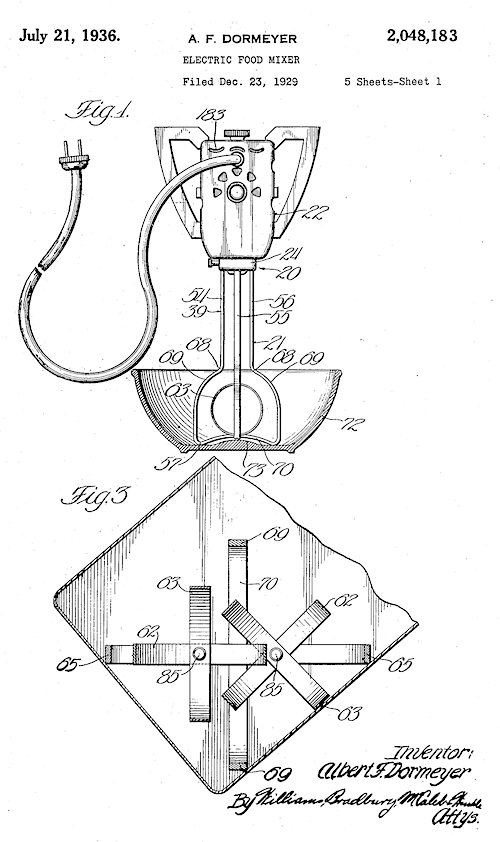

In 1926, he collected his first patent for a new type of automobile muffler, and shortly thereafter, he invented another intriguing device he called an “electric food mixer”—one that could be “conveniently controlled and handled without physical effort, yet include a power source of sufficient strength to perform all types of physical household labor.”

In 1926, he collected his first patent for a new type of automobile muffler, and shortly thereafter, he invented another intriguing device he called an “electric food mixer”—one that could be “conveniently controlled and handled without physical effort, yet include a power source of sufficient strength to perform all types of physical household labor.”

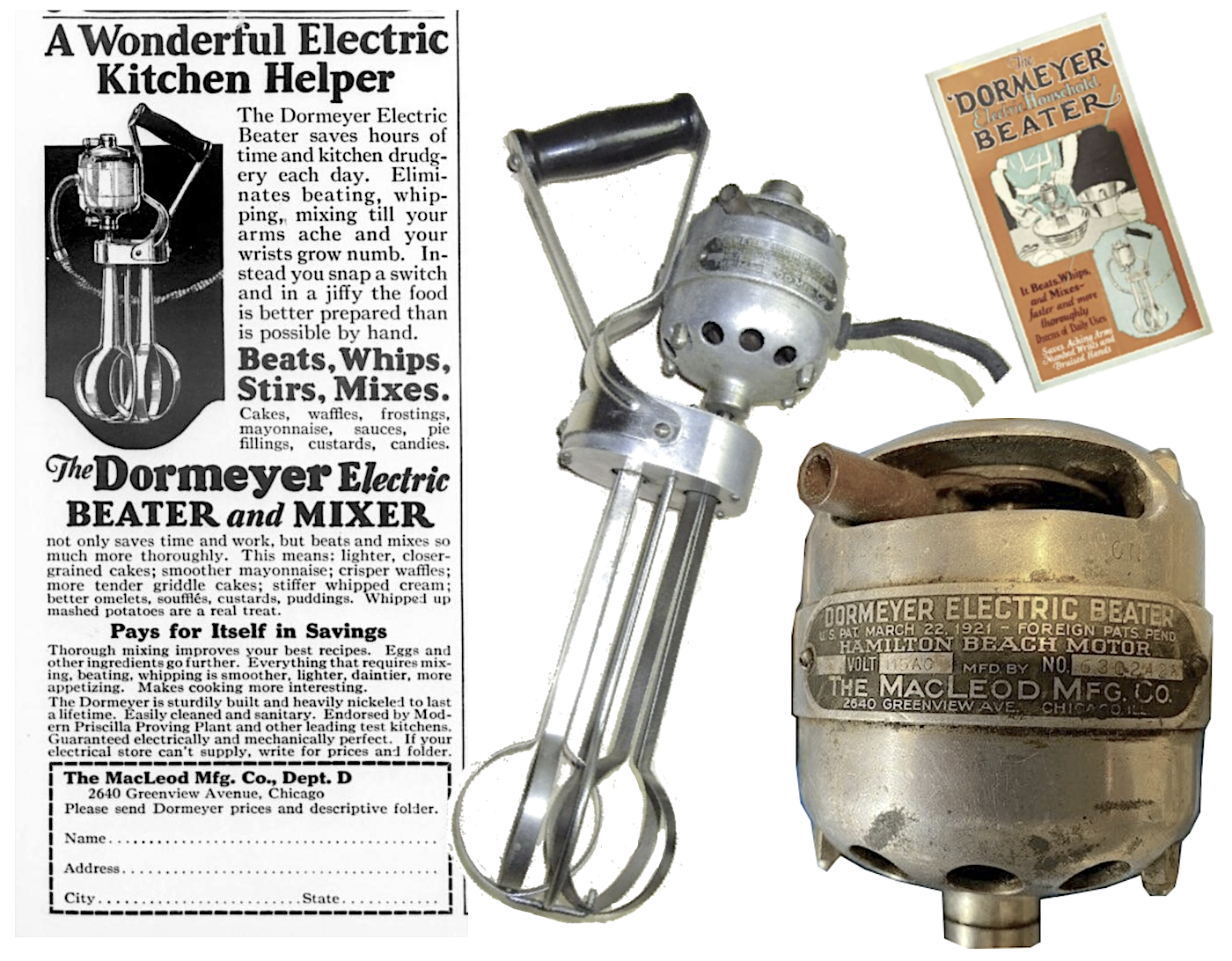

While Albert’s mixer proved very effective, it utilized a motor-type that already existed—patented by the Hamilton Beach MFG Company in 1921—and as a result, his first mixer patent was ultimately assigned to that firm. In response, Albert quickly went to work developing his own motor unit, which would allow him to manufacture his mixer independently. This, we believe, is when he opted to come to Chicago and call on his big brother for help. . . . And Henry Dormeyer, it seems, was more than happy to do so. By 1927, the MacLeod Manufacturing Company started production on its first Dormeyer mixers.

“A Wonderful Electric Kitchen Helper,” read a 1929 ad for the Dormeyer Electric Beater and Mixer. “Saves hours of time and kitchen drudgery each day. Eliminates beating, whipping, mixing till your arms ache and your wrists grow numb. Instead you snap a switch and in a jiffy the food is better prepared than is possible by hand.”

As Henry Dormeyer used his established connections to promote the new appliance nationwide, it became an overnight success. In the July 1929 issue of Hardware Age, it was reported that “sales of the Dormeyer electric food mixer for the first six months of 1929 ran more than 500 percent ahead of the same period of a year ago.” As no coincidence, the MacLeod MFG Company announced that same summer that it would be changing its name to correspond with its new flagship product.

Considering that Henry Dormeyer had been running the business for more than a decade at this point, one has to wonder whether there was any discussion about re-naming the company “Dormeyer & Bro.” or something equivalent. Instead, through some negotiation or magnanimous gesture we’ll never understand, it was decided that all credit would go to the man behind the mixer. And thus, MacLeod Manufacturing became the A. F. Dormeyer Manufacturing Co.

[Eldest brother and company founder Henry A. Dormeyer, seen here as part of church baseball club in 1910, age 24. He would start his business 2 years later and would operate MacLeod MFG / A. F. Dormeyer MFG for the rest of his life, despite not getting the name recognition to go with it.]

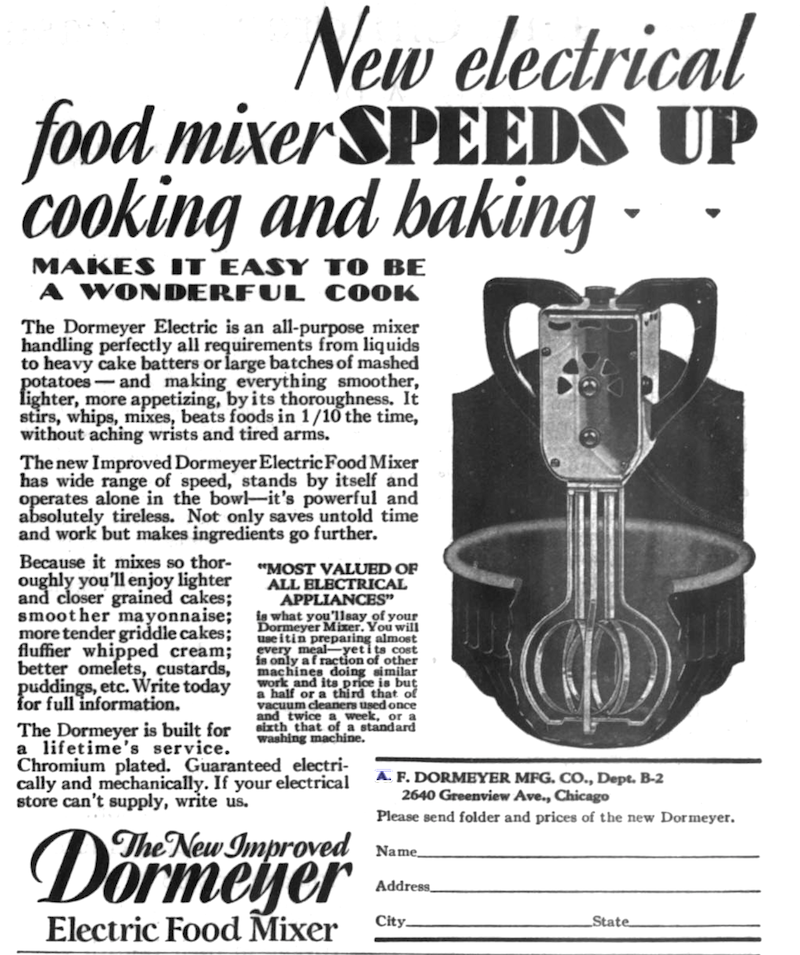

II. “Beating” the Depression

The new A. F. Dormeyer MFG Co. was incorporated in 1929 with 10,000 shares of no par stock, with Henry, Albert, and Albert’s wife Daisy all on the executive board. As part of the rebrand, the company rolled out a new “all-purpose” Dormeyer mixer with “various speeds to take care of all types of batters, from liquids to cake batter and mashed potatoes. . . . It has a single case in which the motor, gearing and rheostat are all placed, and it can stand alone in the bowl without being held.”

Just weeks after the Dormeyers launched this new campaign, the stock market crashed. For plenty of businessmen in similar positions, this spelled doom and retreat. But Albert and Henry, now in their mid 40s, had pushed all their chips in on the kitchen mixer, and as a new modern household necessity, they still believed in its promise. As such, they hired Chicago’s Earl Ludgin, Inc., as their ad agency and continued to promote their goods in major national commercial magazines like McCall’s and Ladies Home Journal.

Just weeks after the Dormeyers launched this new campaign, the stock market crashed. For plenty of businessmen in similar positions, this spelled doom and retreat. But Albert and Henry, now in their mid 40s, had pushed all their chips in on the kitchen mixer, and as a new modern household necessity, they still believed in its promise. As such, they hired Chicago’s Earl Ludgin, Inc., as their ad agency and continued to promote their goods in major national commercial magazines like McCall’s and Ladies Home Journal.

In 1931, the company unveiled the “Royal Dormeyer Electric Food Mixer,” which included a countertop stand from which the motorized beaters could be quickly detached or reattached—essentially making it the prototype for the Sunbeam Mixmaster and modern KitchenAid mixers that followed. Dormeyer initially included specialized glass mixing bowls with its sets, but when those proved a tad too fragile for practical mixing and juice extraction, they innovated again, starting the trend toward stainless steel in the mid ‘30s.

“Business is coming back,” Henry Dormeyer told a reporter during a business trip to Davenport, Iowa, in 1935. And indeed, within a couple years, the A. F. Dormeyer MFG Co. was doing well enough to relocate to a larger factory space at 4316 N. Kilpatrick Avenue in Irving Park. The Great Depression was more about surviving than thriving, however, and with serious competition from Hamilton Beach and Sunbeam, among others, Dormeyer remained something of a small fish, never topping $1 million in annual sales during the 1930s.

[The former Dormeyer factory at 4300 N. Kilpatrick Ave., c. 1940 vs. 2022. It has remained in use as a warehouse and plant.]

There were unforeseen challenges beyond the ledgers, as well. In 1937, vice president and general sales manager Harry Decker died suddenly of a heart attack during a company picnic, and two years later, Henry Dormeyer—the company president and the man who’d inarguably built the foundation of the business—suffered the same fate, aged just 53.

These personal losses, combined with shortages of aluminum and other metals brought on by the U.S. Military’s growing involvement in World War II, put surviving brother Albert Dormeyer in a difficult position. While his name was on the door, it’s not clear just how much of an active role Albert had played in the business since patenting his mixer a decade prior. Tellingly, after his brother’s death, the company presidency went to Henry Dormeyer’s father-in-law, Melville Hunt, rather than Albert. More intriguing still, the 1940 census lists Albert Dormeyer as an “automobile salesman” rather than an employee or executive of his own namesake company.

These personal losses, combined with shortages of aluminum and other metals brought on by the U.S. Military’s growing involvement in World War II, put surviving brother Albert Dormeyer in a difficult position. While his name was on the door, it’s not clear just how much of an active role Albert had played in the business since patenting his mixer a decade prior. Tellingly, after his brother’s death, the company presidency went to Henry Dormeyer’s father-in-law, Melville Hunt, rather than Albert. More intriguing still, the 1940 census lists Albert Dormeyer as an “automobile salesman” rather than an employee or executive of his own namesake company.

As best we can tell, Albert and Daisy Dormeyer probably didn’t like the economic outlook for the A. F. Dormeyer MFG Company heading into the 1940s. So, after Henry’s death, they began looking for an opportunity to unload their shares in the business and hopefully make a decent payday in the process. They just needed to find someone willing to invest in a manufacturing company during the extreme uncertainty of a world war.

Enter Titus Haffa.

III. Dormeyer vs. Haffa

In June of 1944, Albert and Daisy Dormeyer struck a rather unusual deal with a man who seemed perfectly suited to solve their problems. Titus A. Haffa was a walking personification of Windy City moxie, representing both the best and worst of the town.

Born to German immigrant parents during the World’s Fair summer of 1893, Haffa was forced to become resourceful at a young age after his father, a teamster, died in 1904. As his own personal folklore goes, teenage Titus—living in the South Side’s rough-and-tumble 23rd ward— supported his widowed mother and three sisters by starting his own newspaper selling business. “In a few years he built his single bundle of papers into a 10,000 daily sale and found himself with 50 boys and young men in his employ,” according to one highly flattering article, years later, in the Miami News.

Born to German immigrant parents during the World’s Fair summer of 1893, Haffa was forced to become resourceful at a young age after his father, a teamster, died in 1904. As his own personal folklore goes, teenage Titus—living in the South Side’s rough-and-tumble 23rd ward— supported his widowed mother and three sisters by starting his own newspaper selling business. “In a few years he built his single bundle of papers into a 10,000 daily sale and found himself with 50 boys and young men in his employ,” according to one highly flattering article, years later, in the Miami News.

Haffa used his newspaper earnings to put himself through college, then sold the business to fund the expansion of a tool and die factory he’d purchased. “By that time, the neighbors who knew the story of his struggle up from the sidewalks made him an alderman. He served for 10 years.”

Amusingly, the Miami News piece on Haffa, published in 1942, makes no mention of the fact that his political career had ended in scandal, tried and convicted of running the sort of booze ring he was ostensibly supposed to be cracking down on. Instead, over the ensuing decade after his release from prison, Haffa had masterfully constructed a new image, and a new fortune, using the same skills that had served him as a newsie in the 1900s.

[Titus Haffa, center, with employees of one of his major manufacturing businesses, the Haber Corporation, in 1944. This was the same year Haffa acquired control of the A. F. Dormeyer MFG Co.]

In the late 1930s, Haffa anticipated a war on the horizon, well before many of his fellow industrialists seemed to realize it. With a screw machine business, a scrap metal business, and a tool and die business already under his wing, he began actively seeking out government contracts for defense work years before Pearl Harbor and the formation of the War Production Board. “When no one else would handle defense orders,” according to the Miami News, “Haffa began to adapt his plant to the difficult and precise jobs—jobs that mean whether a bomber will fly or fall. Now he is on top.”

In that same 1942 article, Haffa—who was supposedly in Miami for the first vacation of his entire life—explained why he’d never taken time off before. “I’ve always been too busy taking advantage of the fact that in America I could do so many things that my father was unable to do in the old country,” he said.

By 1943, according to the Chicago Tribune, Titus Haffa owned 18 different companies engaged in war work, which had already netted him $8 million in personal earnings several years into World War II. In terms of potential buyers for the floundering A. F. Dormeyer Manufacturing Company, there might not have been a more obvious suitor. The only thing causing Haffa to hesitate in his negotiations with the Dormeyers was the inevitable tax headache that would come with acquiring another major business. He had already been in the crosshairs of tax collectors throughout much of the early ‘40s and was none too pleased about it. To make the Dormeyer deal worth his while, the ever “resourceful” Haffa would need a clever plan.

And so, rather than simply buying the Dormeyer MFG Co. outright in 1944, he came to an agreement with Albert and Daisy Dormeyer—one that the courts would later describe more accurately as a “conspiracy to cheat and defraud the United States government of income tax.”

The quick summation of the backroom deal was this: Albert Dormeyer would request and obtain a permit from the War Production Board to produce at least 5,000 food mixers. Titus Haffa would then do the actual work of making the mixers, under the banner of his Screw Manufacturing Company, and would take on Albert and Daisy as employed “advisors,” paying them $10,000 a year through the duration of the war. In reality, the Dormeyers weren’t expected to do any work whatsoever—quite the contrary, as they were essentially asked to make themselves scarce. According to Albert’s own sworn testimony in “Dormeyer vs. Haffa” two years later, the contract of employment “was a mere sham and device or method of paying, in part, for the shares of stock” of the Dormeyer MFG Co.

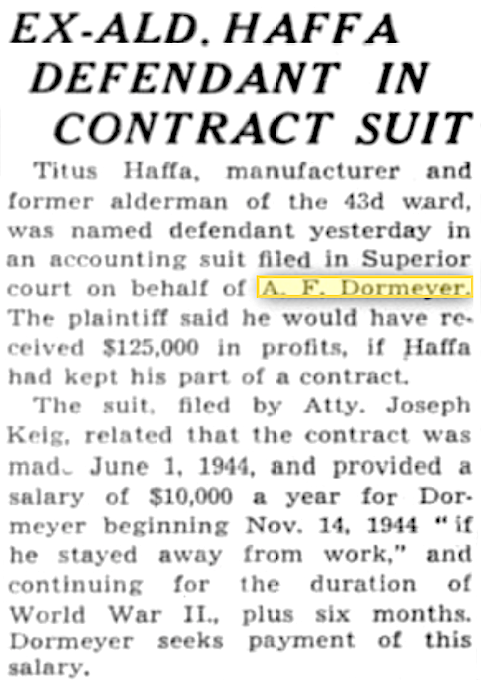

This might never have come to light if not for the fact that Haffa apparently didn’t keep up his payments to the Dormeyers, leading Albert to file an ill-advised lawsuit.

This might never have come to light if not for the fact that Haffa apparently didn’t keep up his payments to the Dormeyers, leading Albert to file an ill-advised lawsuit.

“Titus Haffa, manufacturer and former alderman of the 43rd ward, was named defendant yesterday in an accounting suit filed in Superior court on behalf of A. F. Dormeyer,” the Tribune reported on July 27, 1946. “As part of the same suit, Albert asked that his name be removed from the title of the firm now controlled by Haffa.”

One could certainly debate whether the Dormeyers had been “screwed over” by a notably corrupt business partner, or whether they’d made their own bed by trying to clip out Uncle Sam during a world war. Either way, once the details of the deal came to light, Albert had no real chance of getting his money back, nor his name off the banner. The courts weren’t interested in bailing him out.

Meanwhile, the longtime employees at the Dormeyer factory found their futures in the hands of a man who’d made a fortune off the war, but whose ability to succeed in peacetime still remained to be seen.

[Employees posing with brand new mixers inside the Dormeyer factory on Kilpatrick Ave., circa 1946. The photo was donated by Fritz and Fay Michaelis. Fritz’s uncle Otto Michaelis immigrated to Chicago from Germany in 1927 and became a longtime product developer with Dormeyer. Otto is the short man in the front row, standing next to the man holding the mixer.]

IV. Out of the Ashes

“I’d rather make $1 profit each on the sale of 2 million machines than make a $5 profit each on the sale of 100,000 machines.” —Titus Haffa

In 1950, Titus Haffa was again the subject of a Miami News feature, which hailed him as a “production genius,” particularly for how he’d turned around the fortunes of the business now known as the Dormeyer Corporation.

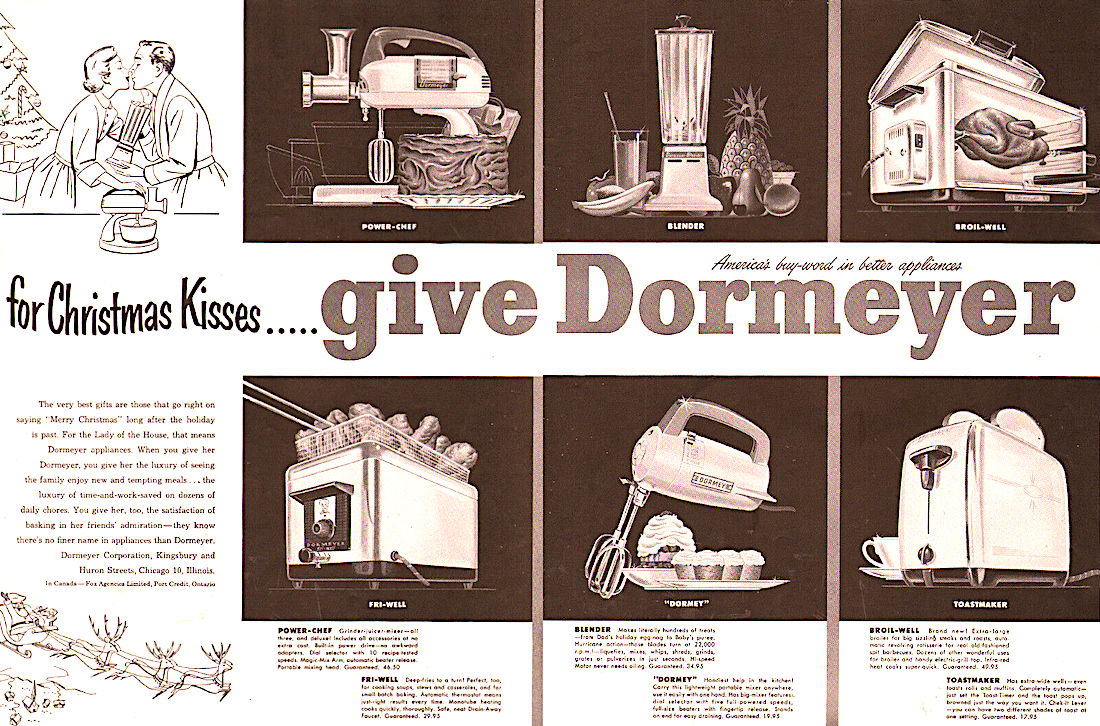

According to the article, Haffa had improved the classic countertop mixer and the portable “Dormey” model by “installing high speed precision manufacturing methods” and “instituting production economies born of big scale purchasing.” The company now built over a million mixers per year, compared to 60,000 a few years earlier, and its annual sales topped $20 million . . . putting them #1 above Sunbeam for a brief moment; quite a leap for a business that never even reached $1 million in sales under the old regime.

“Eventually,” Haffa told the newspaper, “and I believe it will be in the not too distant future, the entire world, except Communist-controlled countries, will be forced to adopt our free enterprise system. Therein lies the great, golden future for American business.”

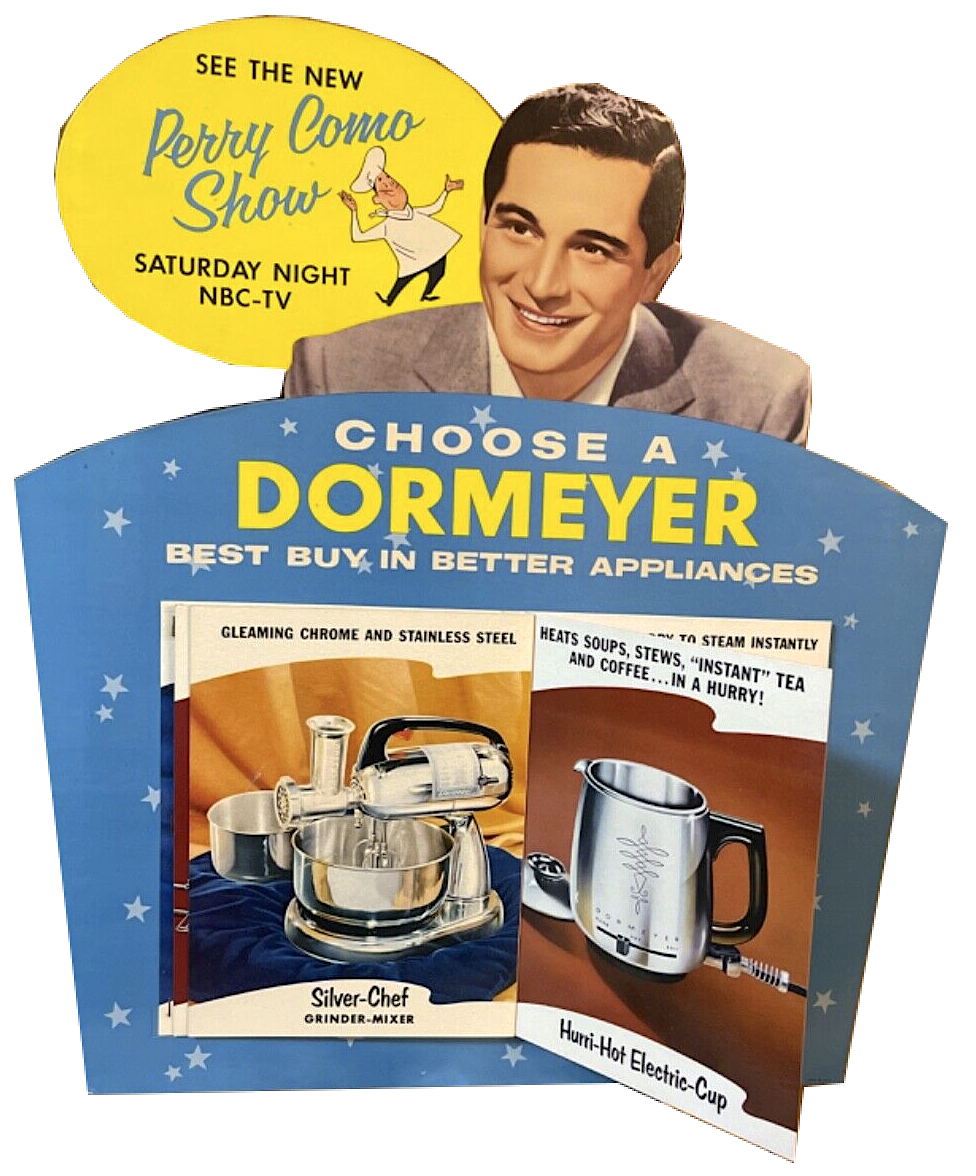

[Advertisements from the early 1950s]

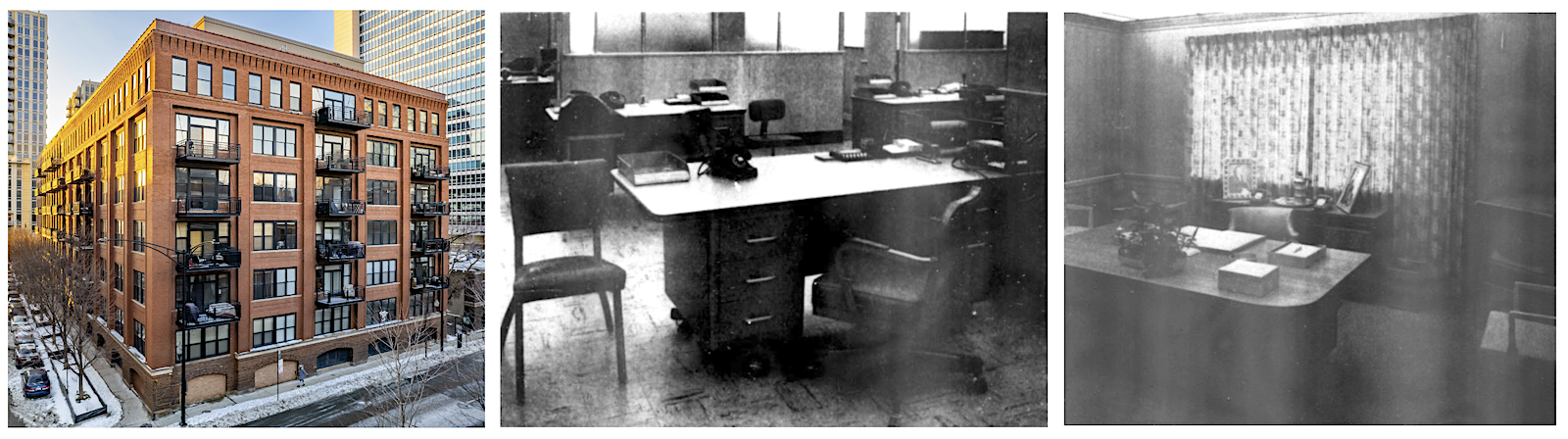

To keep pace with its own growth and an expansion into more appliances, the Dormeyer Corp. spent much of 1952 relocating to a six-story building at 700 N. Kingsbury Street in River North. The new HQ was quickly modernized in an open-floor fashion emphasizing steel and plastic—save for the wood-paneled executive offices of company president James E. Archambault (a longtime cohort of Haffa) and VPs Nick Malz and Marvin E. Allesee. Titus Haffa’s own cameo role at the new plant was that of “executive vice president,” and if you asked him who actually “owned” the business, he would have told you that his wife Ethel Haffa held the most shares (likely for tax reasons). Of course, none of these other folks’ contributions stopped Titus from taking full credit for Dormeyer’s success.

He was similarly braggadocious about his other businesses, including the Haber Corp and Vail MFG Co., which maintained ongoing government contracts during the Korean War period. As he approached the age of 60, though, Haffa was now “re-investing” much of his own time and money into more personal interests, such as Miami Beach condos and prized race horses (his wife once supposedly bid $850,000 for a single champion stud horse).

[Left: The former Dormeyer building at 700 N. Kingsbury. It later became home to the Stiffel Lamp Co., and since 1998 has been a condo complex called River North Commons. Center: A view of the general office in 1953, with chairs supplied by Chicago’s Royal Metal MFG Co.; photo from Office Appliances magazine. Right: The office of company president James Archambault, 1953, from Office Appliances magazine.]

Living a cliched life of luxury was no crime in itself, but as the Haffas paid less attention to the needs of their Chicago properties, consequences did arise. In one case, in particular, their actions—or lack thereof—might have contributed directly to one of the city’s worst industrial tragedies.

On April 16, 1953, a horrific factory fire destroyed the headquarters of Titus Haffa’s flagship company, the Haber Corporation, an airplane part manufacturer located at 908 W. North Avenue. The blaze left 35 employees dead and many more injured.

Haffa, who owned and operated the plant with his three sisters, claimed in later court testimony that “it was just a big mystery” to him how the fire could have spread so fast and caused such damage. By contrast, Assistant Fire Commissioner Anthony J. Mullaney testified that, “If existing ordinances had been followed, no one would have died in the fire. The ordinances are adequate to have covered the situation. If the [owners] had followed the code in obtaining the necessary permits for remodeling, this wouldn’t have happened. There were no direct means out of the building from the upper floors.”

Haffa, who owned and operated the plant with his three sisters, claimed in later court testimony that “it was just a big mystery” to him how the fire could have spread so fast and caused such damage. By contrast, Assistant Fire Commissioner Anthony J. Mullaney testified that, “If existing ordinances had been followed, no one would have died in the fire. The ordinances are adequate to have covered the situation. If the [owners] had followed the code in obtaining the necessary permits for remodeling, this wouldn’t have happened. There were no direct means out of the building from the upper floors.”

In the wake of the tragedy, a jury agreed that negligence had contributed to the disaster, but they couldn’t pinpoint a direct cause-and-effect that could lead to criminal charges against Haffa—who instead offered to tear down the rest of the factory and replace it with a children’s playground.

Less than a month after the Haber fire, a small homemade bomb was thrown through the roof of a Dormeyer Corporation warehouse at 2119 N. Damen Avenue; a likely attempt at retaliation against the Haffa family. No one was hurt.

Yet again, Titus Haffa improbably skated through this period and came out unscathed—he was a successful businessman first, a corrupt politician and criminally negligent landlord second.

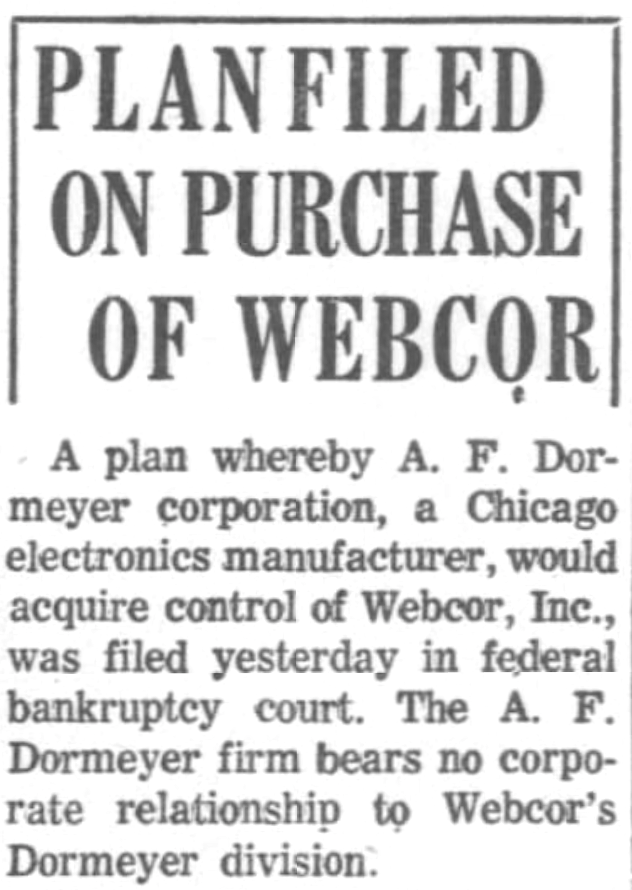

By 1955, as the Dormeyer Corp. aggressively entered the power tool market, Haffa made another major power play of his own, leading a semi-hostile takeover of the Webster-Chicago Company, a leading producer of electrical recording equipment. Also known as Webcor, the firm had long been owned by Rudolph Blash, an old childhood friend of Haffa from back in the newsboy days. Over time, though, Haffa’s role as an outside “advisor” to his pal evolved more into a Rasputin-and-Czar sort of relationship, as he convinced Blash to back out of a merger with the Emerson Radio Corp., then gradually started buying up more and more shares of Webcor stock to help Blash “recoup his losses.” All of the sudden, Haffa had a majority stake in the firm, and he decided to wield his new power by firing four Webcor executives without even bothering to consult with company president Norman C. Owen. In response, Owen resigned, and Haffa slid right into the presidency. “I thought I could work on the sidelines,” he told Business Week. “I wasn’t after any scalps.”

For the next few years, with technology rapidly evolving in both home appliances and tape recording, Webcor and Dormeyer each made their last big runs at relevance heading into the 1960s.

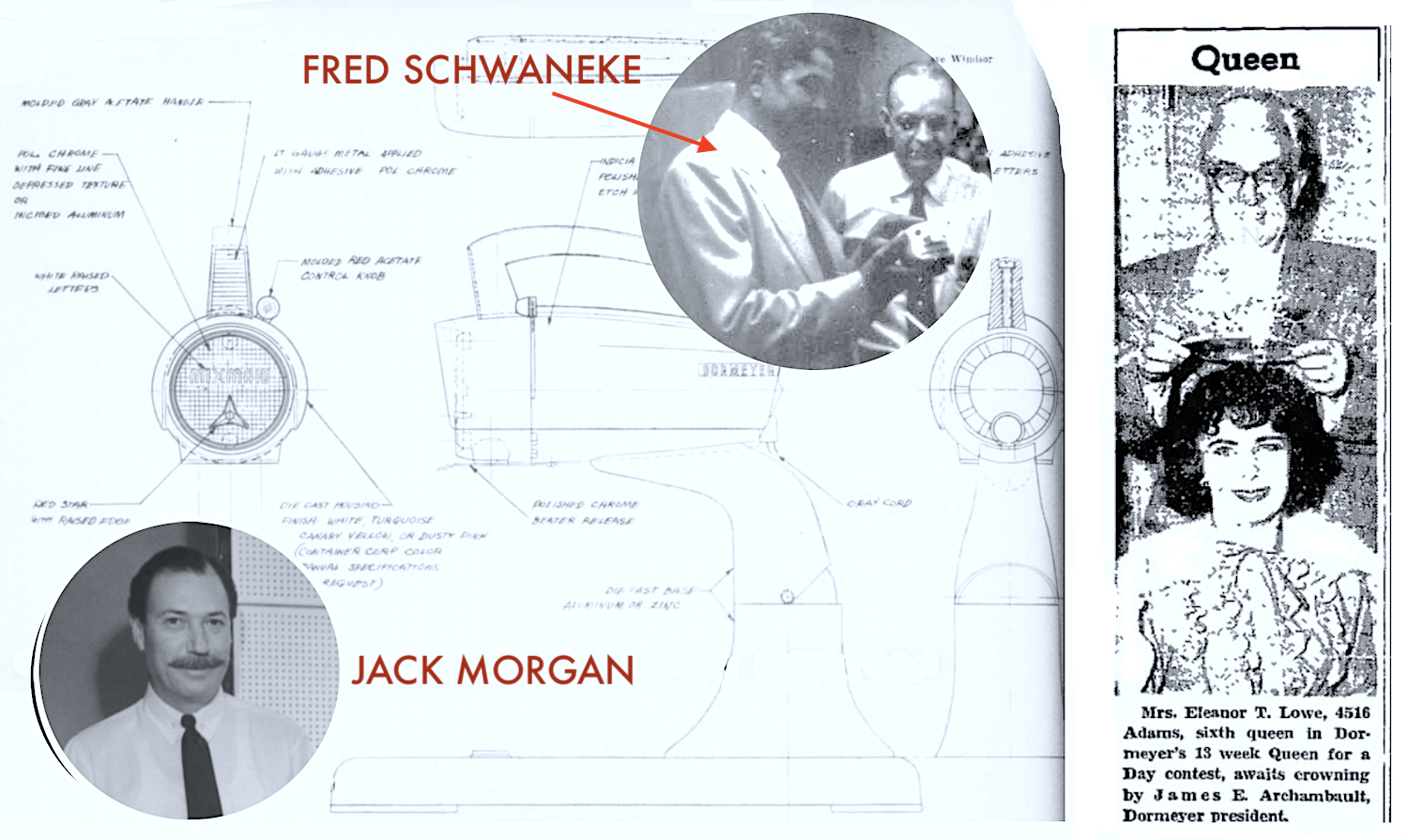

[Left: Designer Jack Morgan and chief engineer Fred C. Schwaneke were key product developers for Dormeyer in the ’40s and ’50s. Right: In 1960, President J. E. Archambault started a weekly drawing in which a different female Dormeyer employee would be crowned “Queen for a Day.” In the newspaper image, he is crowning the sixth winner, Mrs. Eleanor T. Lowe, a line tester on the mixer line.]

At the Dormeyer offices, James Archambault had assembled a crack team of product developers, led by chief engineer Fred C. Schwaneke and design consultant Jack Morgan, who combined to create many iterations of the “Dormey” mixer in the ‘50s, along with an assortment of fryers, broilers, coffee makers, irons, and hair dryers. The power tools, judging by the patent info available, may have been more the domain of another engineer, Otto Doerner, who developed key aspects of Dormeyer’s power saw and power drill in the mid ‘50s.

We’re not sure who gets the credit for the look of the Orbital Sander in our museum collection, but it remains a good representative of both late ‘50s design and the Dormeyer Corporation at its peak. This exact model, the 5-4100, was advertised in major magazines like Life, Look, and the Saturday Evening Post in 1957, indicating the national mainstream target audience of Dormeyer’s new Power Tool Division.

We’re not sure who gets the credit for the look of the Orbital Sander in our museum collection, but it remains a good representative of both late ‘50s design and the Dormeyer Corporation at its peak. This exact model, the 5-4100, was advertised in major magazines like Life, Look, and the Saturday Evening Post in 1957, indicating the national mainstream target audience of Dormeyer’s new Power Tool Division.

“Without question, you now own the finest sander on the market,” read the instruction manual that came with the 5-4100. “The easiest to use, and the most dependable for many more hours of faster, smoother sanding on all materials. With the simplest care, and correct use, it will last indefinitely.”

The same could not be said, sadly, about the Dormeyer Corporation.

V. When One Dormeyer Closes, Another Opens

In 1958, Titus Haffa filed a defamation suit against the producers of the TV show Playhouse 90, which had aired an episode about the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre in which his name had been briefly mentioned. For all his focus on editing his past, though, Haffa’s reputation in the present was already starting to fade among his fellow industrialists, some of whom now saw him as overreaching, dishonest, and reckless following the Webcor buyout and the subsequent struggles of that business.

In 1960, looking to consolidate his weakening empire, Haffa merged the Dormeyer Corp. under the banner of Webcor. James Archambault was named president of Webcor as part of the same move, but after his death two years later, the foundation of both businesses continued to crack.

In 1960, looking to consolidate his weakening empire, Haffa merged the Dormeyer Corp. under the banner of Webcor. James Archambault was named president of Webcor as part of the same move, but after his death two years later, the foundation of both businesses continued to crack.

Meanwhile, another wholly unrelated business, known as Dormeyer Industries, was quietly on an upswing. This was the company that our old friend Albert F. Dormeyer had launched in 1946, shortly after realizing he wouldn’t be getting his big payday from Titus Haffa.

Dormeyer Industries actually started out as Dean W. Davis & Company, but after Davis himself died in a car accident, Albert Dormeyer purchased the entire business, as well as its factory in Kentland, Indiana. An additional home office and plant was established at 3418 N. Milwaukee Avenue in Chicago, and another later opened in Rockville, IL. After the death of Albert’s wife Daisy in 1952, their children Karl Dormeyer and Bliss Sorensen joined the company on the executive board.

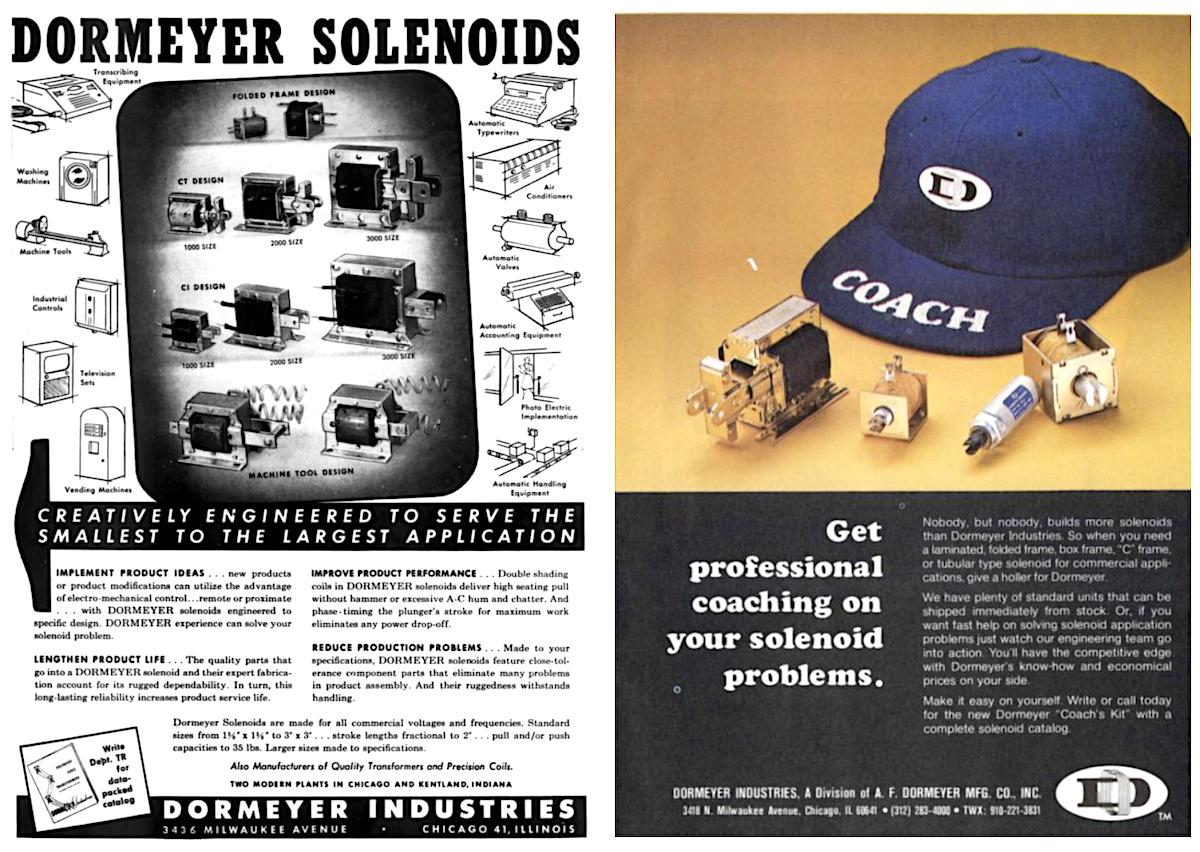

This business wasn’t intended to challenge the original Dormeyer firm—they probably couldn’t have legally tried to anyway—so there were no kitchen mixers or power tools coming out of the Kentland plant. Instead, Albert’s new venture focused on the “guts” of modern appliances—namely, the magnetic-type electric controls (aka solenoids), coils, transformers, and relays that helped them operate. This included the necessary components of everything from washing machines and slide projectors to the automatic pin-setting machines at the local bowling alley.

[Two advertisements for Dormeyer Industries, from 1958 (left) and 1978 (right). This business, purchased by Albert F. Dormeyer in 1946, had no connection to his original Dormeyer Corp., nor did it compete directly with it, as the new business focused on producing small electronic accessories such as solenoids, rather than the appliances themselves.]

By 1964, Dormeyer Industries was “one of the world’s largest producers of auto washer solenoids,” according to the Journal and Courier in Lafayette, IN. Backed by this success, the company was officially re-incorporated that year as the A. F. Dormeyer Corporation—a bold move that certainly thumbed its nose at the other Dormeyer Corp., which was now merely a slumping arm of Webcor.

Understandably, as an electronics firm with “Dormeyer” in its name, the solenoid business was routinely presumed to be one-and-the-same with the kitchen mixer business, and this mistake has carried on into the internet age, as distinctions are still rarely made between the two.

To make matters more confusing, there was a brief moment when the two Dormeyer companies very nearly DID merge back into one.

In 1967, with Webcor in bankruptcy and looking to sell off its Dormeyer division, a surprising bid came from none other than Albert F. Dormeyer himself. At the age of 79, Albert was now in the justly poetic position of being able to bail out Titus Haffa and reclaim his original business. The terms of a new sale were reported in the Tribune and seemed like an inevitability, but perhaps, at the last moment, the two bitter old men couldn’t quite come to a handshake. Instead, Webcor was sold to the International Fastener Research Corp. (Los Angeles) for liquidation. And by January of 1968, the Dormeyer division of Webcor was auctioned off to Waring Products, including all of its “patents, molds, fixtures, dies, and accounts.” The Dormeyer factory at 700 N. Kingsbury had already closed two years prior.

In 1967, with Webcor in bankruptcy and looking to sell off its Dormeyer division, a surprising bid came from none other than Albert F. Dormeyer himself. At the age of 79, Albert was now in the justly poetic position of being able to bail out Titus Haffa and reclaim his original business. The terms of a new sale were reported in the Tribune and seemed like an inevitability, but perhaps, at the last moment, the two bitter old men couldn’t quite come to a handshake. Instead, Webcor was sold to the International Fastener Research Corp. (Los Angeles) for liquidation. And by January of 1968, the Dormeyer division of Webcor was auctioned off to Waring Products, including all of its “patents, molds, fixtures, dies, and accounts.” The Dormeyer factory at 700 N. Kingsbury had already closed two years prior.

Waring Products eventually phased out the Dormeyer brand altogether, which was probably quite alright in the view of the “other” Dormeyer Corporation, which continued producing solenoids in Indiana into the 1980s. Albert F. Dormeyer died in 1973.

As best we can tell, Dormeyer solenoids are still on the market, though the brand has continued to pass through various owners over the past 40 years, and it has become unclear who, if anyone, has exclusivity on the name.

Titus Haffa died in 1982 to little fanfare, aged 89. His talents as a businessman, ultimately, could be debated, but there is no denying that he was a fascinating character and a Chicago original, for better or worse.

Sources:

“MacLeod Window Cleaners” – House Furnishing Review, July 1916

“Dormeyer Offers New Electric Food Mixer” – Electric Refrigeration News, Sept 25, 1929

“Ex Newsboy, Now Defense Figure, On First Vacation” – Miami News, Feb 25, 1942

“Millionaire Tries to Raise Cash for Taxes” – El Paso Times, July 15, 1943

“Ex Ald. Haffa Defendant in Contract Suit” – Chicago Tribune, July 27, 1946

“Miami Eyed for Appliance Plant” – Miami News, March 19, 1950

“A.F. Dormeyer, Appellant, v. Titus Haffa, Appellee” – Appellate Court of Illinois, April 9, 1951

“The Haber Corporation Fire in Chicago” – Digital Research Library of Illinois History Journal

“Bomb Exploded in Warehouse of Titus Haffa” – Chicago Tribune, May 8, 1953

“Plus Service Sells Large Installation” – Office Appliances, May 1953

“Square D Company vs. Dormeyer Industries” – U.S. Court of Appeals, 7th Circuit, Dec 7, 1954

“Webcor Aid Wants Report on 4 Firings” – Chicago Tribune, July 14, 1955

“Lid Blows Off Webcor’s Rough and Tumble Row” – Business Week, July 23, 1955

“Supply and Design: They Strike a Balance in the Chicago Area” – Industrial Design, October 1956

“Chicago Couple Reports $156,000 Penthouse Theft” – Miami News, March 3, 1958

“Chances are That New Automatic Appliance has Kinship to Kentland” – Journal and Courier (Lafayette, IN), Sept 21, 1963

“Scoto, Inc. vs. Dormeyer Industries” – U.S. Court of Appeals, 7th Circuit, Feb 1, 1966

“Plan Filed on Purchase of Webcor” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 4, 1967

“Winsted Waring Division to Absorb Chicago Firm” – Hartford Courant, Jan 19, 1968

Interesting article! Just inherited my mom’s Dormeyer 4200 mixer we believe was a wedding present in 1950. Though it’s not been used probably for 20 years, it still works. I cleaned it up. We’ll see if I can whip up another cake.

I’am thrilled about this wonderful article about my DORMEYER Blender from 1929.

I’ am always seeking written testimony about my objects. I’am proud of the art deco Design.

Thankyou for offering this text.

https://mybasel.space/tour/bakelit-museum

Greetings from the bakelitmuseum.ch

I still own my mother’s amazing Dormeyer stand mixer model 4300. But only have one beater remaining!

Is it possible to locate a replacement beater , this workhorse is amazing g and sturdy and I hate to get rid of it!!

help!!

I have a mixer/stand my husband bought me an I’ve never used it because If there is such a product to be had, I’d like to get what is called ‘a dough hook’ an try it out. Thank you

You have no mention of Albert Dormeyer’s son Carl or grandson Albert F. “Ricky” Dormeyer. A.F. and Carl did not get along. There was no plan for succession. They were, in fact, estranged for many, many years. Sad family. Carl’s own electric motor company Bobbin Coil Specialists is still in business. Carl died in the early 1970s. He was in his early 50s. Ricky served with valor in the Vietnam conflict and worked for his sister Darlene at Bobbin Coil Specialists when he was able.

Dormeyer Industries was my first job out of school in 1975. This was at the building on Milwaukee Ave. At that time we were only producing industrial transformers and solenoids. My first business trip was to our factory in Kentland, IN. We also had another factory in Rockville, IN. At the time I left the company we had a contract to produce plug in power packs for a kitchen product, a ‘cookie shooter’ that pumped out cookie dough. Dormeyer transformers and solenoids are still online possibly made by Johnson Electric.

I remember the Dormeyer name on the front office building of the old Ford plant 7200 S Cicero

in the mid 1950s, does any one else remember this?

I needed to drill holes in my planter bricks to let water drain during heavy rains. I tried two had drills that I own. Skil and craftsman with chargeable batteries but neither worked I used the same drill bit with both drills. Dormeyer model SD 3bb plug in drill that was my Pops from the 50s. That drill worked in a matter of minutes and drilled through the bricks. Wish I knew exactly how old it was and if there is a manual. In my humble opinion, I think now a days products are made to be disposable and are junk.

I just found a dormeyer broil-well in the original box with packing and paperwork all intact that has never been used. Is it worth anything?

I have a dormeyer automatic cordless toothbrush circa 1940’s. How much is it worth today. It’s unused and still in box

How old is my drill model number 5-2102

Serial number 0022945

when did Dormeyer put blender model 12-212 on the market

I have Dormeyer power chef modelSM12