Museum Artifact: Scholl’s Arch Fitter, 1910

Made By: The Scholl MFG Co. / Dr. Scholl’s, 213 W. Schiller St., Chicago, IL [Old Town]

The rather intimidating metal clamping device pictured above was manufactured around 1910, and represents one of the earliest inventions of a young Chicago podiatrist turned entrepreneur named William Mathias Scholl.

Now wait a minute . . . Does this mean that the ubiquitous pharmacy icon “Dr. Scholl” was, in fact, an actual flesh-and-blood person, and not a fictional cartoon compatriot of Mr. Clean and Mrs. Butterworth? Well, yes. But you can be forgiven for presuming otherwise.

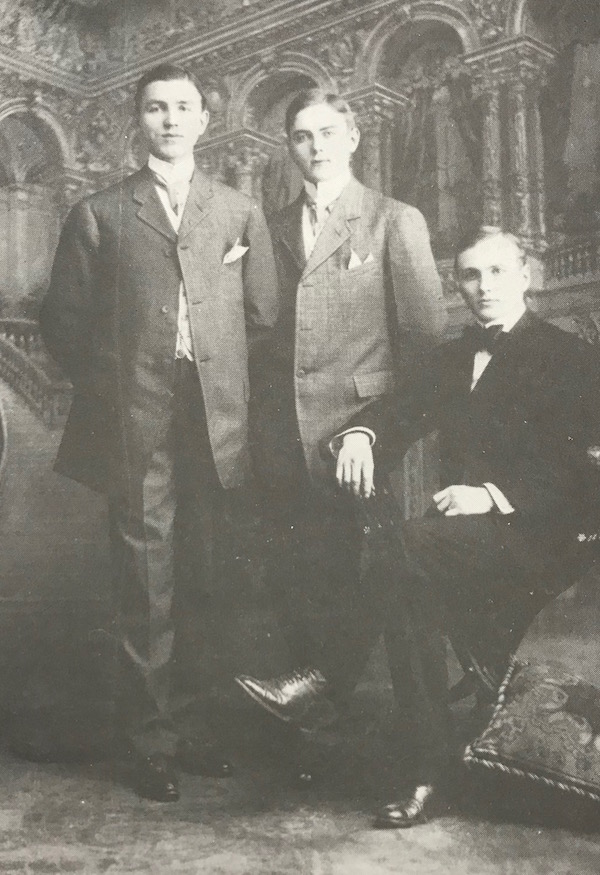

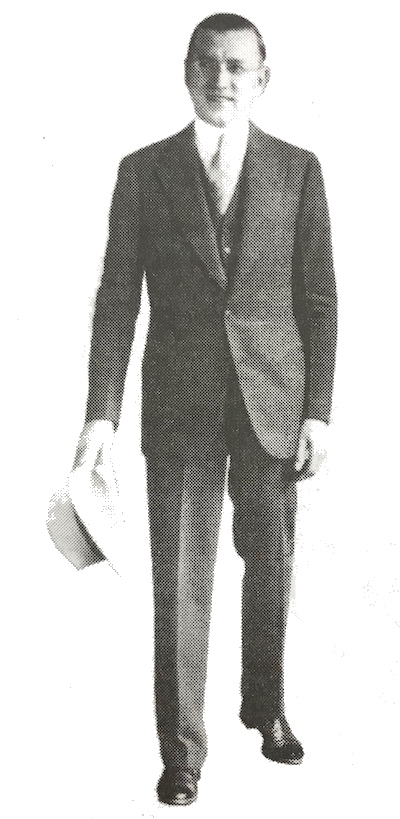

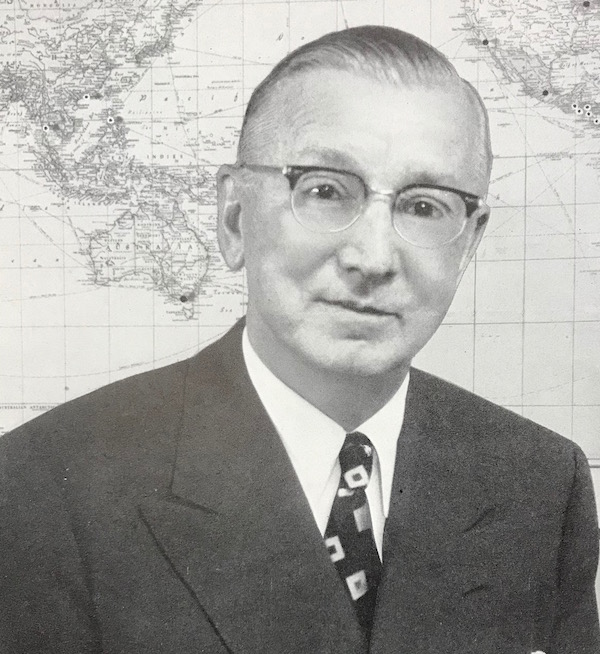

Despite essentially inventing the modern foot care industry and patenting over 300 products related to it, the real Dr. Scholl [pictured] has gradually been eclipsed by his own brand name during the 50+ years since his death (probably due in no small part to the Scholl family selling the business in 1979). In the process, we’ve forgotten just how significant of a figure William Scholl was in his own time, while also losing the ability to distinguish the facts of his accomplishments from some of the weeds of mythology that have sprouted out of them. This has left us with a simultaneously obscure and larger-than-life character (a real Paul Bunion, you might say)—a foot guru full of contradictions.

Despite essentially inventing the modern foot care industry and patenting over 300 products related to it, the real Dr. Scholl [pictured] has gradually been eclipsed by his own brand name during the 50+ years since his death (probably due in no small part to the Scholl family selling the business in 1979). In the process, we’ve forgotten just how significant of a figure William Scholl was in his own time, while also losing the ability to distinguish the facts of his accomplishments from some of the weeds of mythology that have sprouted out of them. This has left us with a simultaneously obscure and larger-than-life character (a real Paul Bunion, you might say)—a foot guru full of contradictions.

Depending on which resources you choose to pull from, William M. Scholl was either a medical revolutionary or a quack; a compassionate educator or an ambitious opportunist; a sober, god-fearing man or a cafe-society skirt-chaser. The truth, as ever, is probably a nice even mixture of all of the above. But one thing’s for sure: Dr. Scholl was a hell of a lot more than a mere brand mascot. Growing up in a puritanical country that found the bare human foot far too taboo to ever boo-hoo about, he single-handedly (or single footedly) changed that dialogue forever—encouraging people to take ownership of their foot pain and not resign themselves to constant misery as the Victorians had. Along the way, Scholl also basically drew up the blueprint for how to build and promote a new over-the-counter commodity, internationally, in the 20th century.

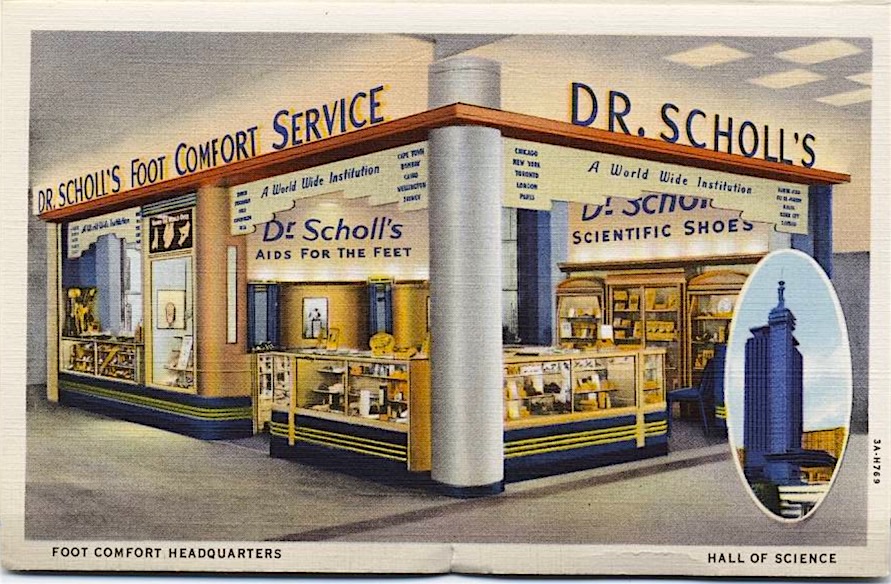

[The Dr. Scholl’s exhibit from the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago]

[The Dr. Scholl’s exhibit from the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago]

A History of Dr. Scholl’s, Part I. “Is That a Foot In Your Pocket?”

Imagine if you will that you’re the proprietor of a shoe shop, circa 1904. It’s summertime and air conditioning doesn’t exist yet, but you’re probably still dressed in a heavy wool suit complemented by a derby hat and a carefully waxed handlebar mustache. Outside, there’s the continuous cacophony of trolley cars, horse hoofs, bicycle bells, and those obnoxious new automobile horns. Maybe a newsboy shouting something about Teddy Roosevelt. You’re generally uncomfortable, but business is steady, because all your customers are uncomfortable, too. Their shoes never fit quite right.

Now, into your establishment walks a young fella, no older than 22—wearing a morning suit, a top hat, round glasses, and a big smile on his face. He saunters right up to the counter.

“Give me five minutes of your time,” William Scholl supposedly told all his prospective clients, “and I will show you how to satisfy your customers so well that they will be your customers for life.”

“Give me five minutes of your time,” William Scholl supposedly told all his prospective clients, “and I will show you how to satisfy your customers so well that they will be your customers for life.”

Okay, so perhaps your first instinct would be to tell this plucky huckster to get lost. But for the shopkeepers who were willing to humor William and let him continue his spiel, a memorable show was always in store.

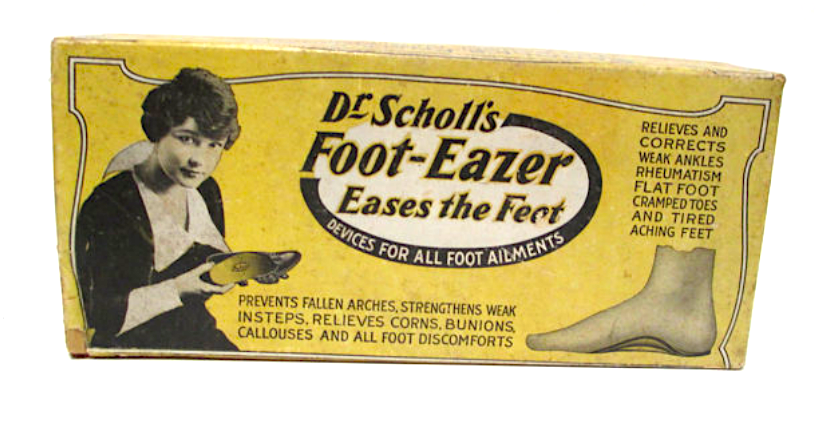

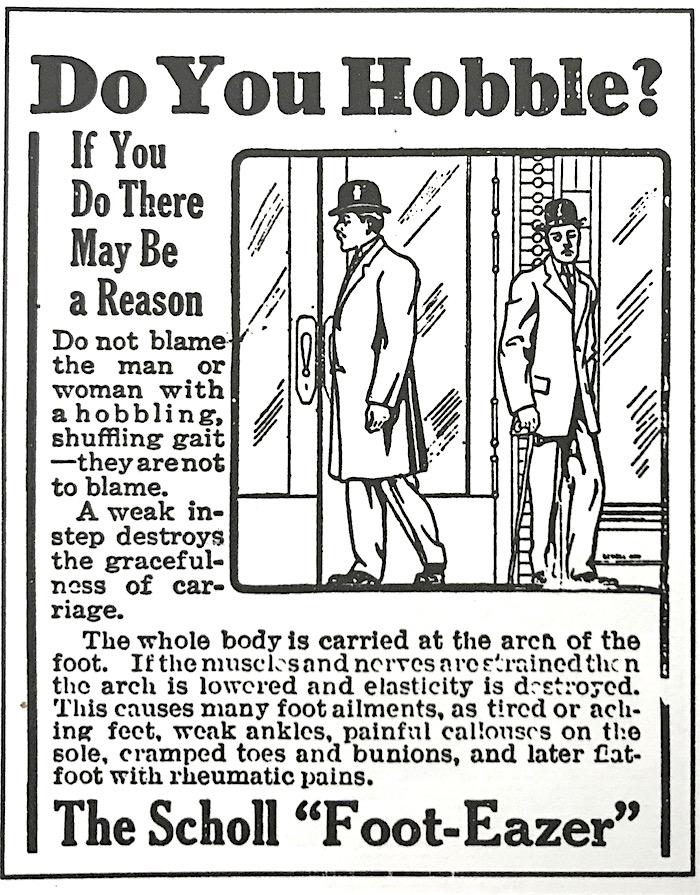

For starters, in a move that even Harry Houdini would have found perplexing, Dr. Scholl swiftly produces two objects from his suit pockets. The first is a small, flexible metal plate with a leather cover—an arch support of his own invention that he calls the “Foot-Eazer.” The second item is, unmistakably, a skeleton foot—as in, a real human foot, stripped of the bothersome muscle and skin. [“Is this guy actually walking around town with a foot in his pocket?” you think to yourself] William then brings the two props together on the countertop—ka-bam! And so the presentation begins.

Here’s an approximation of the early Scholl pitch, written in the doctor’s own words, and taken from a 1911 Foot-Eazer advertisement in the trade publication Boot and Shoe Recorder.

“Let me show you how to increase your sales and double your profits without additional expense! . . . Scholl’s Foot-eazers will fit any foot and any shoe. . . For persons with normal insteps it bridges the weight of the body, taking away the pressure and friction that causes callouses and forward sliding, the cause of corns and cramped toes. . . . Scholl’s Foot-eazers make good. We guarantee them—they were born in a retail shoe store in Chicago—they were made to fill a need—and are now the most meritorious articles of their kind on the market.” —Wm. M. Scholl, President

“Let me show you how to increase your sales and double your profits without additional expense! . . . Scholl’s Foot-eazers will fit any foot and any shoe. . . For persons with normal insteps it bridges the weight of the body, taking away the pressure and friction that causes callouses and forward sliding, the cause of corns and cramped toes. . . . Scholl’s Foot-eazers make good. We guarantee them—they were born in a retail shoe store in Chicago—they were made to fill a need—and are now the most meritorious articles of their kind on the market.” —Wm. M. Scholl, President

Despite not including a “Dr.” in front of that particular signature, Scholl was indeed a graduate of the Illinois Medical College (later a property of Loyola University), where he’d specialized in chiropody, aka podiatry. So he was more than happy to educate people on the problem of weak arches and the science behind his invention. It was perhaps more significant to his target audience, however, that Scholl had developed the Foot-Eazer not in some collegiate laboratory, but in a shoe shop—during his own time as a wunderkind teenage sales clerk for an upscale Chicago store called Ruppert’s. It was in that role, seeing customers’ various foot discomforts each day on the front lines, that he’d first decided to go to med school and attack the problem directly.

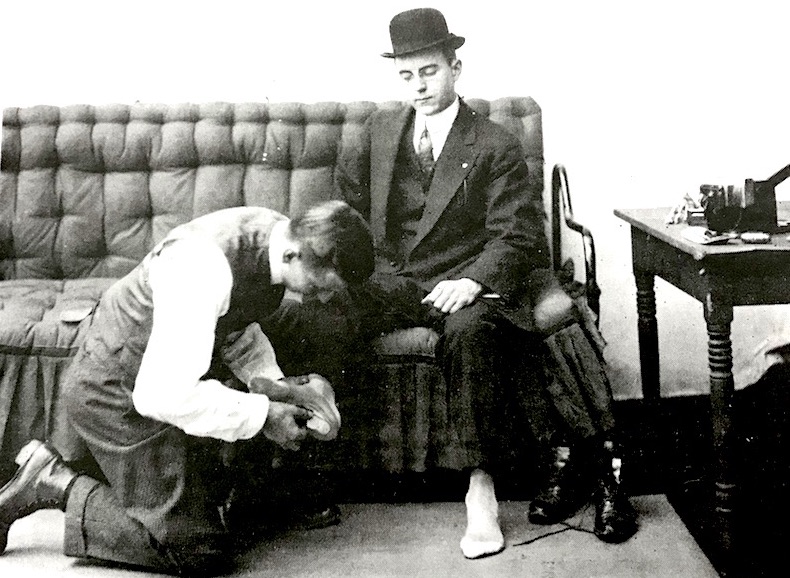

[William Scholl demonstrates the use of his arch support to his brother Frank, in the hat, c. 1909]

[William Scholl demonstrates the use of his arch support to his brother Frank, in the hat, c. 1909]

Scholl’s retail experience had also taught him how to communicate with shoe dealers in their own language, disarming them with his charm. It probably didn’t hurt that he was a straight-laced, baby-faced German Catholic kid, raised on an Indiana dairy farm—it gave him an earnestness not typical of your average big city hustler.

Eventually, even the skeptical merchants became believers in the Scholl doctrine, as customers started coming in and asking for the miraculous little Foot-Eazers by name—partially from word-of-mouth, and partially from early newspaper ads purchased by the progressive promoter. The Scholl Manufacturing Company was now officially in business—founded by William from his own savings and a small loan from his father—but its success would still hinge on one factor above all else: ensuring that Foot-Eazers could be properly custom fit for every customer. There were no Amazon product reviews back then, but if the arch supports didn’t consistently deliver relief for all types of feet, it wouldn’t take long for the public to turn on them. The good doctor needed a long-term solution.

II. The Arch Fitter

In the years before the Scholl MFG Co. officially incorporated in 1907, Willam Scholl was largely responsible for making his entire stock of Foot-Eazers by hand, aided only by a single assistant, a German-born shoemaker named Sam Berman. They worked out of a small office at 358 W. Madison Street, catching the occasional raised eyebrow from passing businessmen in the low-rent building.

As the company grew, however, and the cash flow ramped up accordingly, William was able to lease some far more ample space inside manufacturing complexes at 98 Market Street (now E. Wacker Drive) and 211-213 W. Schiller Street. He also steady built up an arsenal of modern machinery for mass production.

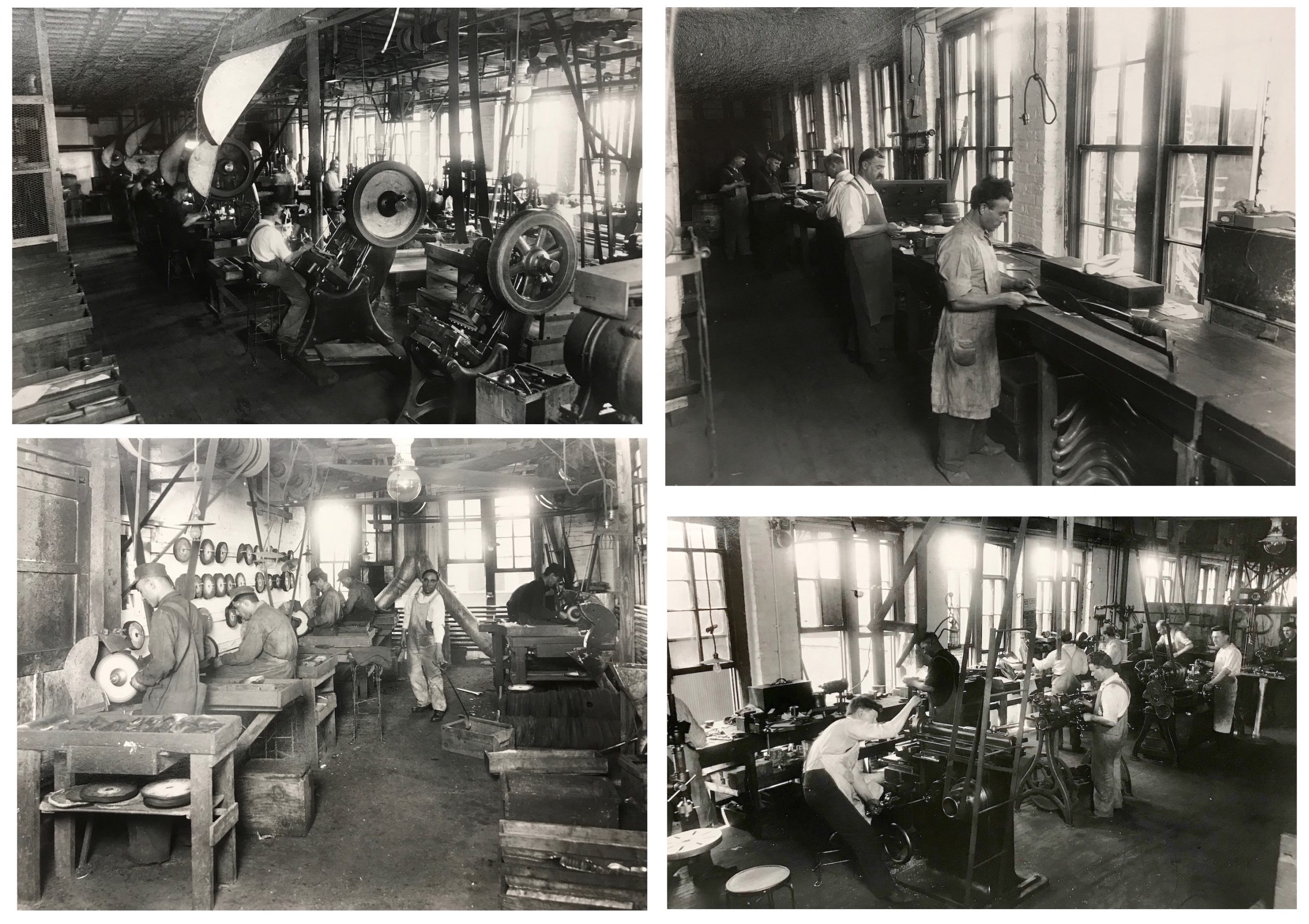

[Workers in Dr. Scholl’s Schiller Street plant, c. 1920. Notice the Arch Fitter, much like the one in our museum collection, located in the lower righthand corner of the image.]

[Workers in Dr. Scholl’s Schiller Street plant, c. 1920. Notice the Arch Fitter, much like the one in our museum collection, located in the lower righthand corner of the image.]

Even with a full team of workers in his employ, though, Scholl knew that his business model could never work if every other pair of Foot-Eazers had to be sent back to the factory for custom adjustments. Instead, there had to be a way for customers to have those adjustments made in the shoe store itself—utilizing a simple device that any shoe salesman could learn to operate.

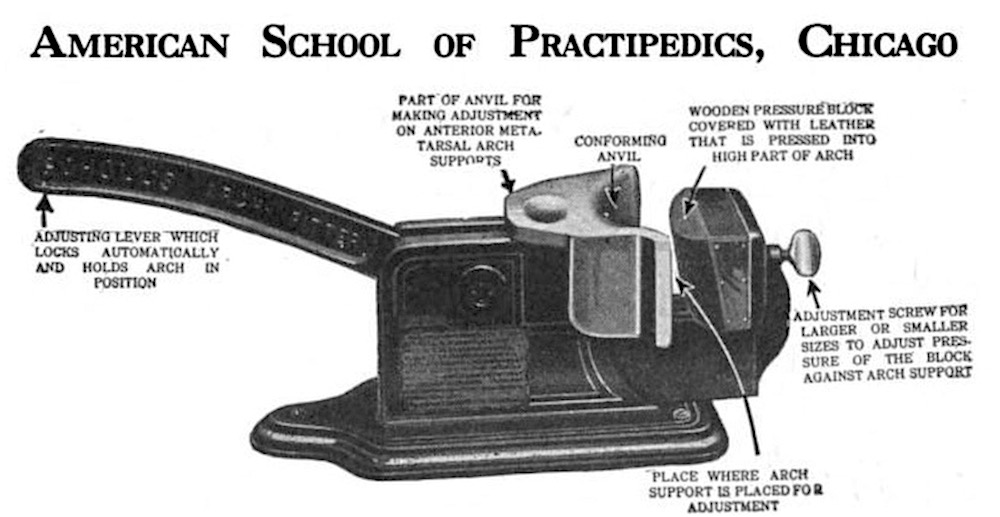

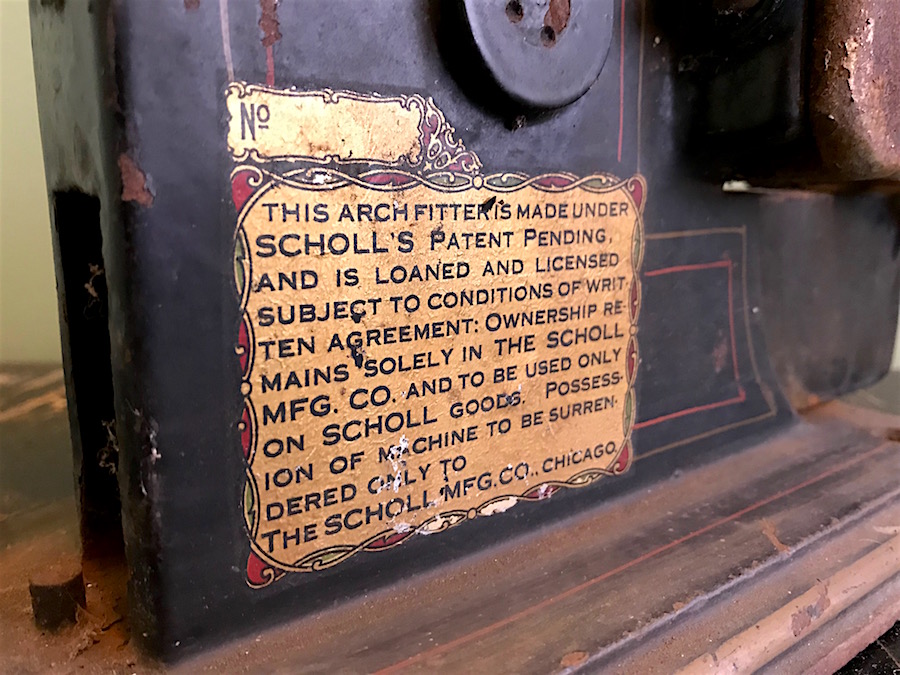

For this task, William tapped into his earliest work experience as a cobbler’s apprentice in Indiana. He understood the nuances of shoe sizing and shaping, and he knew the flexible metal construction of the Foot-Eazers would make them malleable enough to adjust with a basic vise and hammer. And so, in 1909, Scholl applied for a patent on a “metal forming appliance” which would come to be known as “Scholl’s Arch Fitter.” The patent was approved in 1911, which is why we can estimate the production date of our museum model—a “patent pending” edition—to 1909 or 1910.

“With this arch fitter,” according to a 1909 article in The Shoe Retailer, “a support can be made higher or lower and can be changed, not only once, but as many times as desired.

“The apparatus itself is very practical, as it is made of malleable castings and steel, finely enameled and finished. The construction of the apparatus is such that makes it very simple to operate, as it works on the principle of a machinist’s vise; the shaping block is of the right curvature to obtain the best results in changing the shape of the support which is to be fitted. It is operated with a lever and is self-interlocking, so that in the case of a serious deformity of the foot, the support may be locked between the adjusting blocks and hammered out in any required shape.

“Not the least interesting point about the arch fitter is that the inventor, Dr. Scholl, president of the Scholl MFG Co., Chicago, proposes to give it free to dealers.”

Scholl purchased a full-page ad in that very same issue of The Shoe Retailer, in which he refers to the Arch Fitter as “The Rent Paying Machine.”

Scholl purchased a full-page ad in that very same issue of The Shoe Retailer, in which he refers to the Arch Fitter as “The Rent Paying Machine.”

“With the Scholl Arch Fitter you can fit each foot just the same as if a cast of the foot was taken and an arch support made to order,” he claims in the ad. “Then again, the machine makes talk—people ask what it’s for, then they say, ‘Well, I’ve seen those Scholl Foot-Eazers advertised in the magazines, show me a pair,’ then you sell a pair and make a dollar. If I can double your business on Arch Supports I can well afford to give you an Arch Fitter, for naturally you will keep on selling the Scholl Foot-Eazers and Scholl Arch Supports because you will find them the best.”

Handing out hundreds (and possibly thousands) of free Arch Fitters was certainly a gamble for the 27 year-old Dr. Scholl. In theory, the devices would earn their money back by enabling a big upswing in Foot-Eazer sales. But it wasn’t a guarantee.

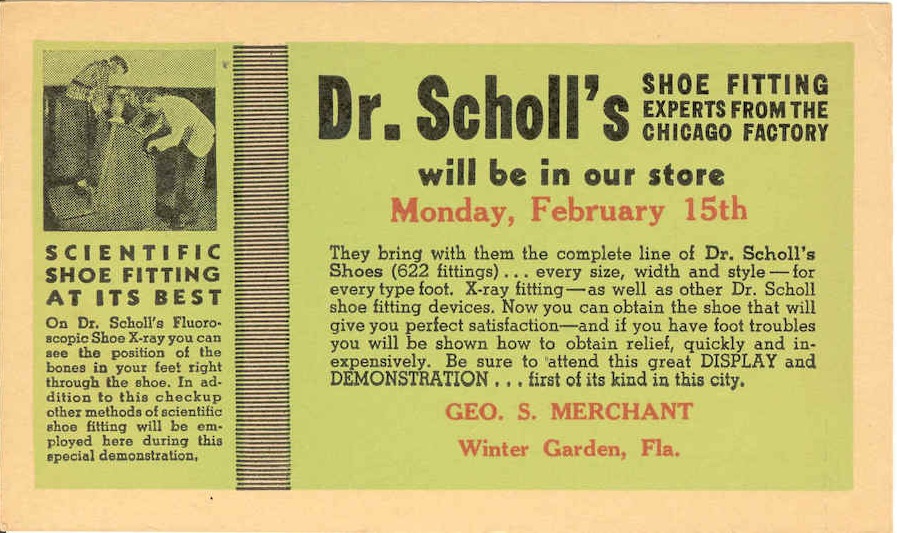

To improve the odds, William double-downed on his promotional efforts, taking every avenue available to him. While still playing the role of the carnival barker pitchman in trade magazines, he also started writing and publishing his own deadly serious journals and guidebooks on the modern science of foot care and the methodology he called “practipedics.” Naturally, this included the creation of point-by-point instructions for the proper use of Scholl tools like the Arch Fitter.

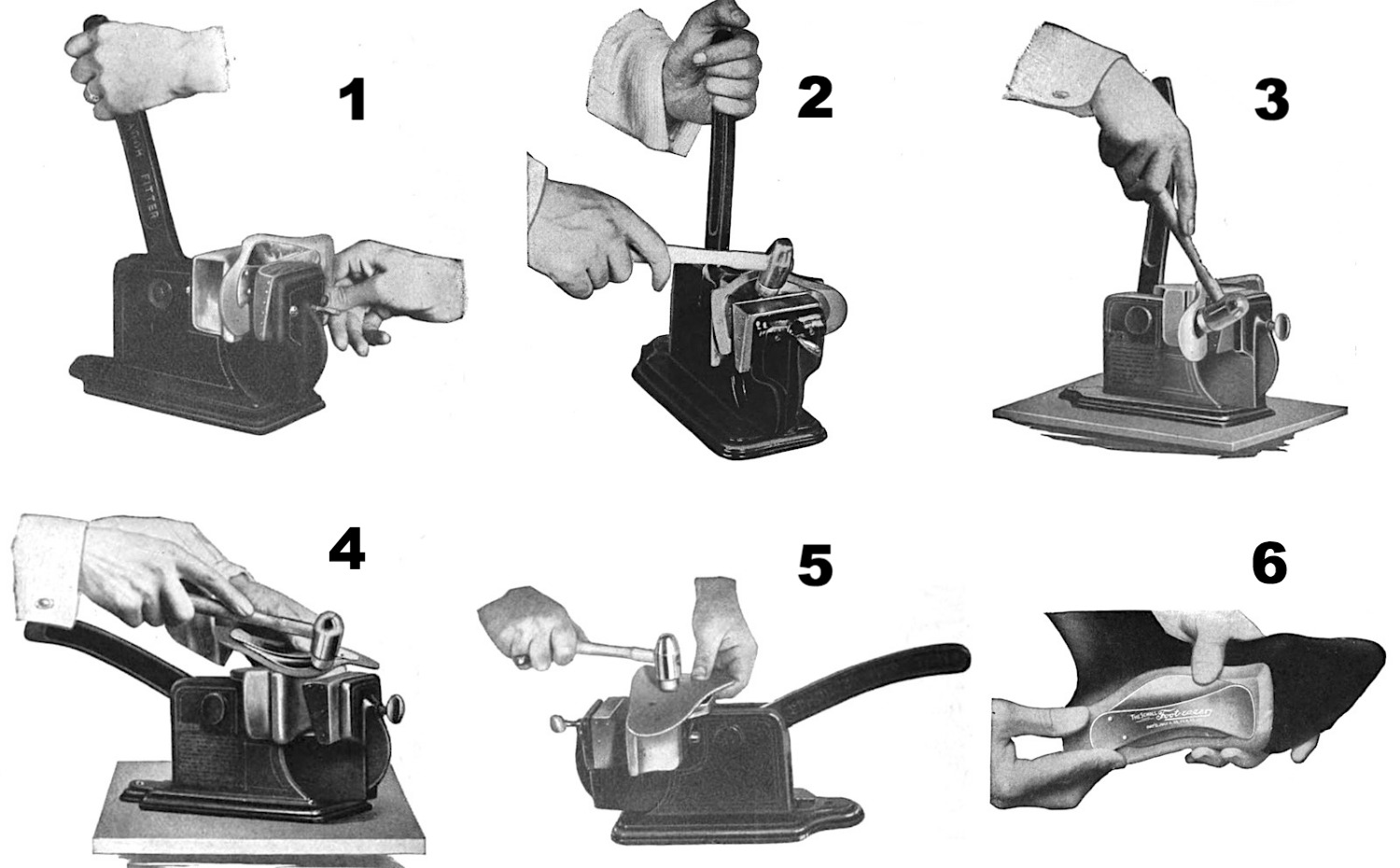

[How to Use the Arch Fitter: (1) Place Foot-Eazer in position for optimal pressure, (2) The pressure you exert on the lever holds the Foot-Eazer stable, (3) Using a rawhide mallet to elongate the heel seat of the support, shortening the elevation of the arch, (4) Smoothing out rough edges after the Foot-Eazer has been re-sized and fitted, (5) Lowering the Foot-Eazer, by gently tapping it on the leather surface with the mallet, (6) When fitted properly, the support should “fit all points of the arch flush from the heel to the metatarso-phalangeal articulation of the great toe joint.” —from William Scholl’s Practipedics, 1917.]

[How to Use the Arch Fitter: (1) Place Foot-Eazer in position for optimal pressure, (2) The pressure you exert on the lever holds the Foot-Eazer stable, (3) Using a rawhide mallet to elongate the heel seat of the support, shortening the elevation of the arch, (4) Smoothing out rough edges after the Foot-Eazer has been re-sized and fitted, (5) Lowering the Foot-Eazer, by gently tapping it on the leather surface with the mallet, (6) When fitted properly, the support should “fit all points of the arch flush from the heel to the metatarso-phalangeal articulation of the great toe joint.” —from William Scholl’s Practipedics, 1917.]

When not traveling on business, Dr. Scholl was spending virtually all of his waking hours in a factory office rather than actively practicing medicine. Nonetheless, he clearly saw himself as an important leader and educator in the foot care revolution, and a growing army of orthopedic disciples, known as his “foot soldiers,” only lent credence to that vision.

III. Scholls on Schiller

Around the same time the Arch Fitter was in the midst of its first promotional blitz, the Scholl MFG Company was becoming a true family affair.

Around the same time the Arch Fitter was in the midst of its first promotional blitz, the Scholl MFG Company was becoming a true family affair.

William’s kid brother Peter Scholl had joined him from Indiana to manage the manufacturing at the Schiller Street plant, and another younger brother, Frank, soon followed, giving up a successful Chicago clothing store to become the company vice president and head of sales. Traveling by train in the early days, Frank Scholl started by gaining new territory in Canada, then took on the welcome challenge of leading Dr. Scholl’s entry into the European market. By 1911, the Scholl MFG Co., Ltd. was established in London, and Frank “F. J.” Scholl was well on his way to a remarkable career of his own.

[pictured above, from left to right, William, Frank & Peter Scholl]

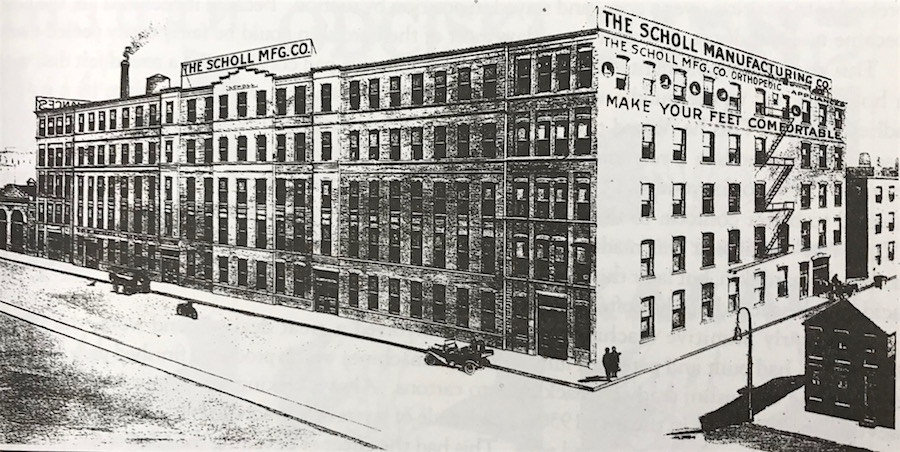

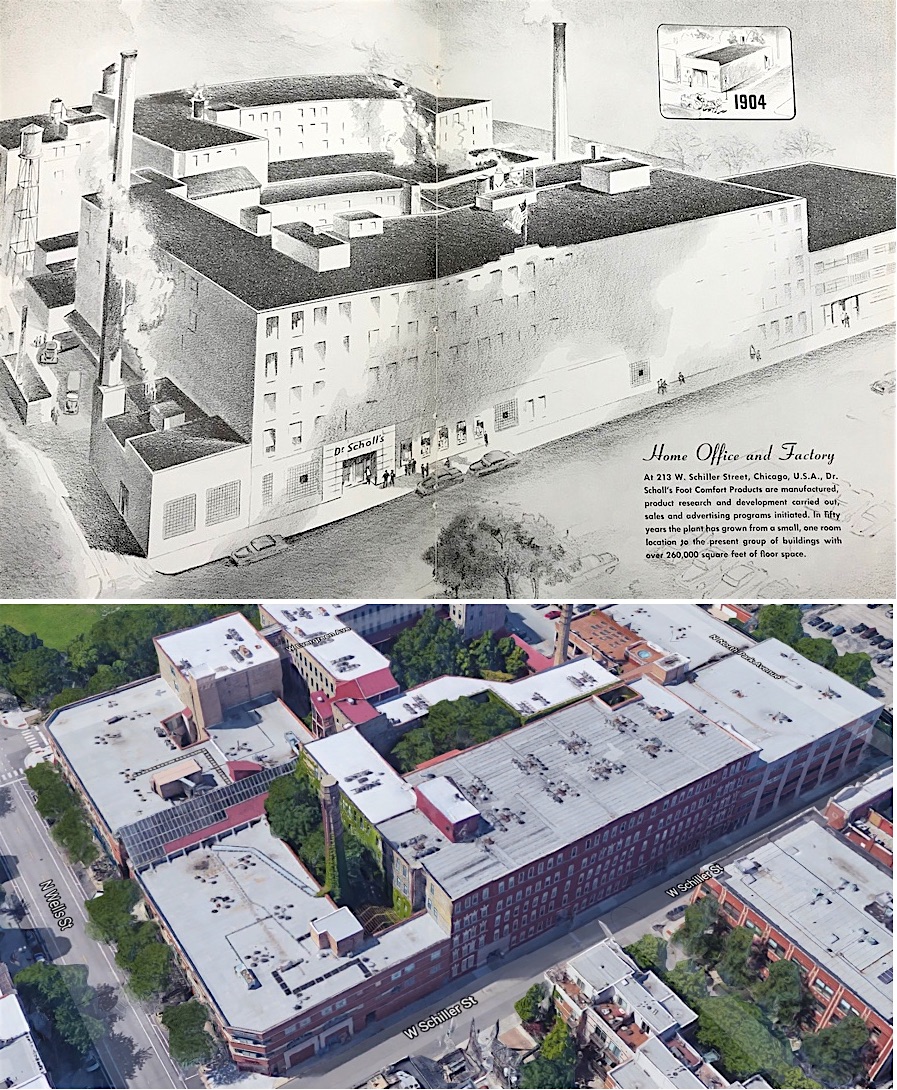

The budding Scholl Empire already had offices in New York, San Francisco, Toronto, and London before William Scholl’s 30th birthday in 1912. But the international headquarters and primary manufacturing facilities remained in Chicago, as the doctor continued to buy up more and more of the factory complex at 213 W. Schiller Street, eventually turning the whole building into a Scholl property.

[Dr. Scholl’s factory, 213 W. Schiller Street in Old Town, c. 1930s]

[Dr. Scholl’s factory, 213 W. Schiller Street in Old Town, c. 1930s]

Machinists and press operators, leather cutters and assemblers, packaging and shipping, receptionists and researchers—there were jobs aplenty to be had keeping up with exponentially growing demands, and more than 300 men and women worked at the Schiller plant by 1918.

William Scholl’s endless drive to promote his existing products and create new ones certainly kept everyone busy. Pretty soon he had developed a familiar motto that he happily shared with anyone seeking the secret to his success: “Early to bed and early to rise, work like hell and advertise.”

[Above: press operators and assemblers at work in the Scholl factory. Below, women at work in filling, packing, and reception departments]

[Above: press operators and assemblers at work in the Scholl factory. Below, women at work in filling, packing, and reception departments]

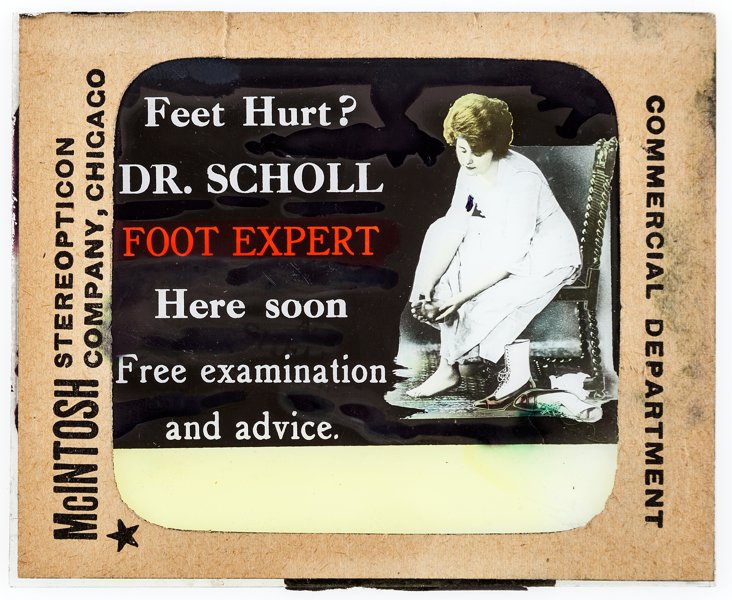

Another type of Scholl headquarters also opened in 1912. Located in the ground floor of a building at 1321 North Clark Street (just a few blocks from the factory), the College of Chiropody and Orthopaedics—which William founded and taught at for years—soon became the largest producer of professional podiatrists in the country. It was emblematic of an overall sea change in society, as the general public slowly got over its irrational foot shame (some newspapers wouldn’t even publish images of bare feet in the early 1900s) and started to see the value in new medical science on the subject.

Not everyone in the medical community was in agreement on who should be leading this new movement, however. It wasn’t just that mainstream doctors took issue with William Scholl’s methods; many questioned his very legitimacy as a supposed chiropodist.

IV. Under Fire from the “Real” Doctors

In the early 20th century, chiropodists—or what we would now call podiatrists—were already considered to be on the fringes of “respected” medicine. Our aforementioned national foot stigma was again one of the main culprits, but there were other reasons—like the relative ease with which a person could acquire a chiropody license from various fly-by-night institutions.

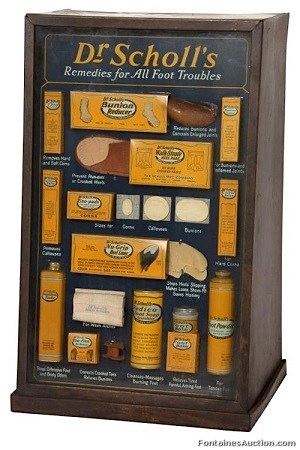

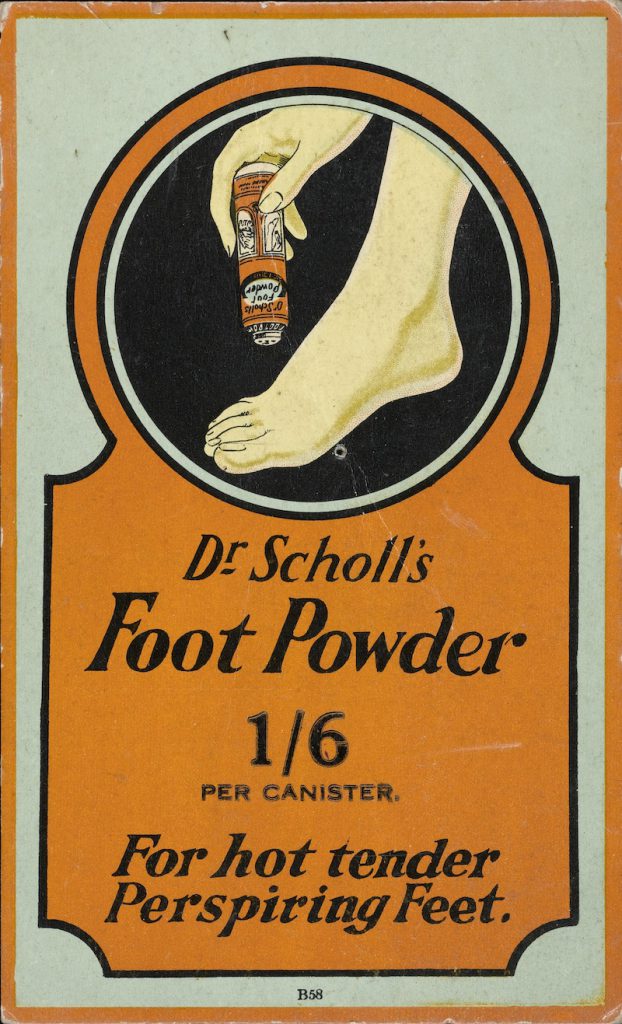

For the community of serious foot doctors trying to improve the overall reputation of this misunderstood field, the success of Dr. Scholl should have been a huge victory for their cause. He was continuing to patent dozens of new, seemingly effective products, from cushioning and tape to foot powders and more advanced supports. Unfortunately, the growing scrutiny around the man’s credentials—and his flirtations with quackery-style promotional techniques—made him something of a lightning rod among his peers. Some of them, more likely, were just flat-out jealous. In the end, the wave of dissent got Scholl railroaded right out of the National Association of Chiropodists by 1923, and the organization wouldn’t even publish Dr. Scholl’s advertisements in its journal for the next 15 years.

For the community of serious foot doctors trying to improve the overall reputation of this misunderstood field, the success of Dr. Scholl should have been a huge victory for their cause. He was continuing to patent dozens of new, seemingly effective products, from cushioning and tape to foot powders and more advanced supports. Unfortunately, the growing scrutiny around the man’s credentials—and his flirtations with quackery-style promotional techniques—made him something of a lightning rod among his peers. Some of them, more likely, were just flat-out jealous. In the end, the wave of dissent got Scholl railroaded right out of the National Association of Chiropodists by 1923, and the organization wouldn’t even publish Dr. Scholl’s advertisements in its journal for the next 15 years.

The American Medical Association was no kinder. Most AMA higher-ups didn’t respect a foot doctor with a Harvard degree, let alone a guy from the Illinois Medical College, so it was an uphill battle from the outset. As Scholl’s wealth and fame continued to grow, the blowback and bitterness from the establishment only escalated. It was a de-legitimization campaign nearly identical to that faced by another former farm boy turned medical millionaire of the same period—Wallace Abbott of Abbott Laboratories—who’d also combined quacky, colorful promotional techniques with legitimate scientific endeavors.

For years, the AMA refused to acknowledge that William Scholl was even a real physician, citing a lack of evidence regarding his supposed 1904 medical degree. When Scholl earned a second degree in 1922 from another (less than elite) institution, the Chicago Medical School, it was dismissed with chuckles. Whispers circulated that he’d merely purchased his diplomas and was not legally licensed to practice medicine in any state.

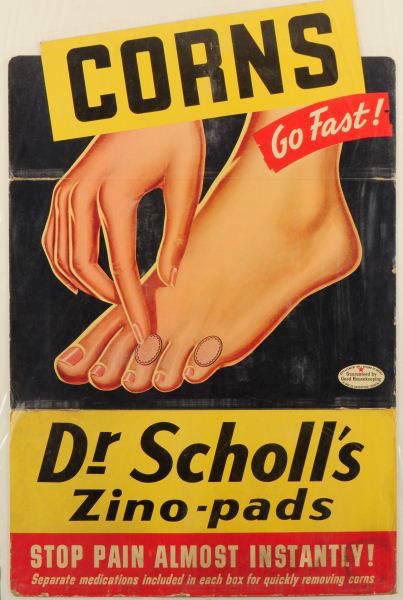

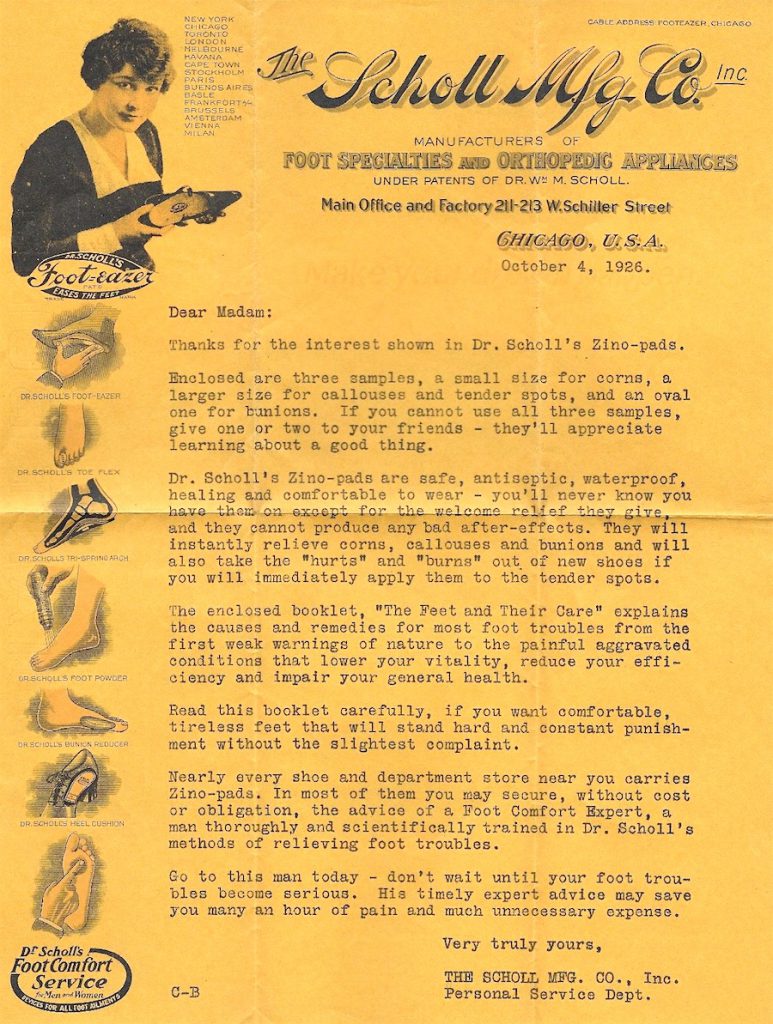

During the 1930s, the Federal Trade Commission took aim at Scholl, as well, cracking down on some of his company’s bold but harmless advertising slogans like “Put one on and the pain is gone”—used for a product called Zino Pads.

During the 1930s, the Federal Trade Commission took aim at Scholl, as well, cracking down on some of his company’s bold but harmless advertising slogans like “Put one on and the pain is gone”—used for a product called Zino Pads.

So, was it true? Was Dr. Scholl more like Mr. Clean and Mrs. Butterworth, after all? Was he a made-up marketing character who just happened to have the same name as the company president?

The short answer seems to be… no. While William Scholl and the larger Scholl Manufacturing family never took particularly aggressive action in fighting against criticisms and “birther” style conspiracy theories, they did produce paperwork on several occasions that backed Dr. Scholl’s claims as a legitimate doc. Even the U.S. State Department offered up a six-page report verifying Scholl’s merits in 1932, after officials in Germany had questioned the Scholl Company’s use of the word “Doctor” (or “Arzt”) in its overseas advertisements. Naturally, the proof provided by the Americans didn’t completely satisfy the Germans—who decided they would let the company use the phrase, “William M. Scholl, the American doctor and orthopedist,” but NOT “Dr. Scholl.”

V. “Know Your Goods”

Maybe the wildly ambitious Dr. Scholl was a bit insecure and embarrassed about his lackluster medical credentials, or maybe his farm boy roots put a Midwestern chip on his shoulder. In any case, there was no pleasing everybody. If the establishment didn’t accept him, Scholl was more than happy to forge his own path, training a new generation of shoe dealers and foot doctors and earning his own legitimacy through good old fashioned results.

Scholl was the rare breed who could put on his salesman hat or industrialist hat without needing to take off his doctor hat. His style of communicating might change from one to the other, but on closer inspection, his core principles were quite consistent. First and foremost—knowledge is power.

Addressing his salesmen: “The first principle of salesmanship is ‘KNOW YOUR GOODS.’ It is, perhaps, the greatest single asset that any salesman can have, and it is the easiest acquired. . . . There are interesting facts about the most commonplace goods. Every industry has its romance, whether it be the collecting of raw material, the story of invention, the epic of thundering factories, or the story of how the goods are built to meet certain requirements. . . . Learn, above all, to impart your knowledge in an interesting way. Facts are only as interesting as the way they are told. The most interesting fact on earth can be made dully uninteresting by poor telling. On the other hand, many uninteresting facts are made interesting by the way they are told.” —A Course of Study in Scientific Shoe Fitting and Salesmanship, 1929

Addressing his salesmen: “The first principle of salesmanship is ‘KNOW YOUR GOODS.’ It is, perhaps, the greatest single asset that any salesman can have, and it is the easiest acquired. . . . There are interesting facts about the most commonplace goods. Every industry has its romance, whether it be the collecting of raw material, the story of invention, the epic of thundering factories, or the story of how the goods are built to meet certain requirements. . . . Learn, above all, to impart your knowledge in an interesting way. Facts are only as interesting as the way they are told. The most interesting fact on earth can be made dully uninteresting by poor telling. On the other hand, many uninteresting facts are made interesting by the way they are told.” —A Course of Study in Scientific Shoe Fitting and Salesmanship, 1929

Addressing his Foot Comfort Centre students: “Practipedics as a science has come to stay because the very root of its existence lies in the fact that what it teaches is fundamentally sound and based upon scientific knowledge and experience. It deals with health, comfort and efficiency; therefore, men or women who sell shoes must know the anatomy of the foot and its normal and abnormal conditions. They should also possess a knowledge of shoe conditions, shoe construction and shoe fitting.” —The Practipedic Reference Guide, 1921

Dr. Scholl made a clear point of holding his national network of dealers to a high educational and ethical standard, regardless of what the AMA had to say. According to the Scholl biography Foot Doctor to the World (written by his nephew William H. Scholl), “No shoe shop was designated a Dr. Scholl’s Foot Comfort Centre unless at least one member of the staff had passed the Practipedics course.”

By the time of his death in 1968, Scholl had about 7,000 of these dealers in his employ in the U.S. alone, with more than 10 percent of them in the Chicago area.

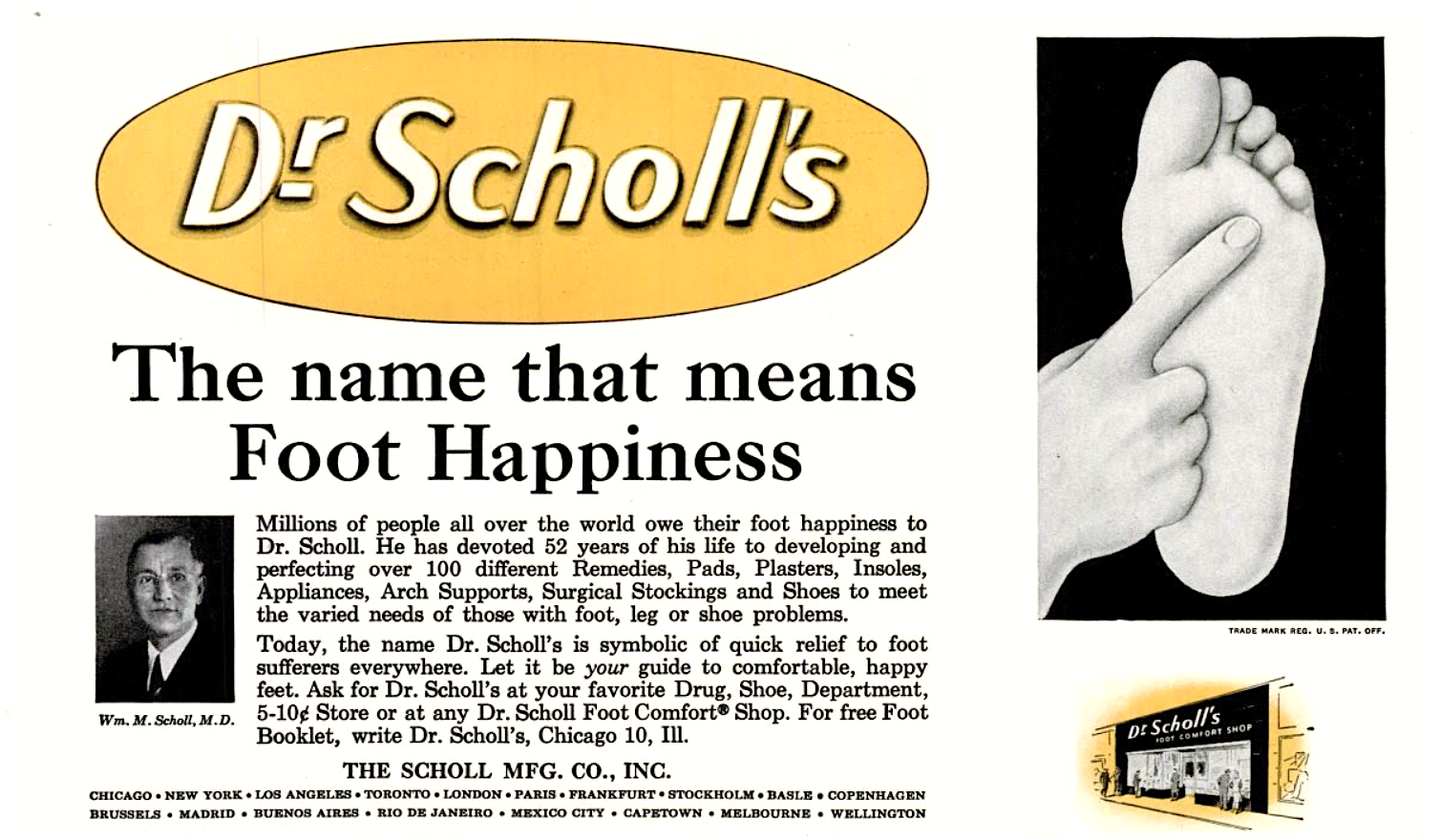

[Excerpt from a Dr. Scholl’s magazine ad, 1956]

[Excerpt from a Dr. Scholl’s magazine ad, 1956]

VI. Truth and Tragedy

In a posthumous profile of Dr. Scholl published by the Chicago Reader in 1994, writer Robert McClory tried to get a sense of the real man behind the famous trademark. After doing some digging and conducting several interviews with people who’d known the doctor, McClory concluded that “Scholl led a decidedly sober private life. He never married, and except for an interest in cooking and a love of travel displayed no passions beyond his devotion to the human foot.

“For many of his active years, he lived in a single rented room at the downtown Illinois Athletic Club and used the common bathroom down the hall. In his later days he maintained homes in both Michigan City and Palm Springs, California, but it appears he spent little time in either. They more often served as vacation sites for his many nieces and nephews.”

“For many of his active years, he lived in a single rented room at the downtown Illinois Athletic Club and used the common bathroom down the hall. In his later days he maintained homes in both Michigan City and Palm Springs, California, but it appears he spent little time in either. They more often served as vacation sites for his many nieces and nephews.”

The Doctor’s own nephew, William H. Scholl, paints a slightly more dynamic picture in Foot Doctor to the World, describing his uncle as “good looking and personable” and “never lacking in attractive girls to escort.” He acknowledges, however, that Dr. Scholl “remained a devout Catholic all his life” and was also “so absorbed with his work, with projects or business discussions,” that his priorities simply “weren’t conducive to lasting relationships.”

That being said, Scholl was actually engaged to be married on two different occasions, the second of which ended in horrific tragedy on an April night in 1927. It’s a story that’s fairly well documented, but never told quite the same way twice, nor to any curious person’s complete satisfaction. This makes it pretty emblematic of the overall Dr. Scholl conundrum.

According to his nephew’s book: “All the signs pointed to a successful conclusion in marriage. Sadly, however, while he was driving one night with his fiancee in pouring rain, the Doctor’s car skidded, ran off the road, turned over and she was killed. The shock of this calamity remained with him for years, and while he continued to enjoy the company of the opposite sex, he never again contemplated marriage.”

[The Daily Times of Davenport, Iowa, April 7, 1927, reporting the death of Dr. Scholl’s fiancee Myrtle Petrson in a car crash. Scholl was injured in the accident, but survived.]

[The Daily Times of Davenport, Iowa, April 7, 1927, reporting the death of Dr. Scholl’s fiancee Myrtle Petrson in a car crash. Scholl was injured in the accident, but survived.]

That deadly car accident, which occurred just outside of Augusta, Georgia, on a drive back to Chicago from Miami, is as mysterious as it is devastating. The deceased fiancee, who was left unnamed in Foot Doctor to the World, was Myrtle Peterson, a 27 year-old native of Moline, Illinois, and “an old friend” of the 45 year-old Dr. Scholl, according to reports from her hometown paper after the accident.

While Peterson was killed instantly, Scholl and a third passenger—Dr. W. F. Martin of Battle Creek, Michigan—survived with relatively minor injuries. The next day, the Battle Creek Enquirer actually cited Dr. Martin—rather than Dr. Scholl—as the driver of the vehicle: “Dr. Martin explained that he was driving at night and suddenly came upon an unlighted detour sign. He swerved to take the side road and the car [a Lincoln sedan owned by Scholl] went into a ditch and turned over.”

A third description of the accident comes from another Dr. Scholl biography—an unauthorized one called Uncle Doc, written by a more distant relative, a great-nephew named John Scholl III. Here, we get a wildly different, almost ridiculously detailed account of a soap operatic betrayal, a scorned woman, and a terrifying scene on an open road.

John Scholl refers to “Uncle Doc” as a “sun-worshipping playboy” who palled around with Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald and spent most of his time in Florida “becoming acquainted with women staying at the hotel.” On one of those occasions, allegedly, William’s fiancee Myrtle Peterson (whom John Scholl wrongly refers to as “Margaret ‘Peg’ Peterson”) secretly traveled down from Chicago to surprise him with a visit, only to find a blonde under the doctor’s arm.

“Peg was furious with Dr. Scholl,” John Scholl writes, “and after a quick exchange of words, became hysterical. She jumped into his limousine and started the engine. Henry [William’s chauffeur] entered into the passenger side to try and stop her, but she already started to drive away. Dr. Scholl jumped on to the running board, and was pulled inside the front seat by Henry.

“Peg was furious with Dr. Scholl,” John Scholl writes, “and after a quick exchange of words, became hysterical. She jumped into his limousine and started the engine. Henry [William’s chauffeur] entered into the passenger side to try and stop her, but she already started to drive away. Dr. Scholl jumped on to the running board, and was pulled inside the front seat by Henry.

“Peg sobbed and veered from left to right on the road at speeds up to 70 miles per hour. Dr. Scholl pleaded with her and grabbed the wheel every time the long sleek limo started to leave the road. Henry sat helplessly in between the two lovers as they cried and fought for control of the car.

“Suddenly Peg declared that if she couldn’t have Dr. Scholl, no one would. At that, she steered the car off the road and into a ditch, where it rolled over and came to a halt against a tree. Peg’s chest was crushed by the steering wheel during the impact, and she died instantly.”

John Scholl further claimed that Ms. Peterson was actually the SECOND woman to kill herself over her passion for the foot care king. Another girlfriend, some 20 years earlier, had supposedly become pregnant by Scholl back in Indiana, and committed suicide by arsenic when William refused to marry her.

It sure sounds like a load of exploitative tabloid nonsense, but John Scholl III (grandson of Dr. Scholl’s much younger brother John) claimed to have referenced actual letters in his family’s collection to substantiate some of his stories. Even if some concrete evidence exists of certain misadventures, though, we’re always left with the same problem when it comes to mythologized men. We can try our best to trust the storytellers or to filter out the dramaticized drivel from the real substance, but in the end, we’re often left with contradictions and paradoxes. Three different people can be behind the wheel of a car when it crashes.

VII. One’s Work Is Never Done

The version of Dr. Scholl that most of his fans choose to memorialize, of course, is not the tragedy-scarred lover, but the obsessively dedicated worker.

“Legends surround Scholl’s lifelong missionary approach to his work,” Robert McClory wrote in the Reader piece. “On the road, he loved to drop in unannounced at his stores to see if operations complied with his requirements. He also regularly approached strangers on the street if they appeared to be hobbling, inquired about their feet, and offered to take them under his wing.

“Legends surround Scholl’s lifelong missionary approach to his work,” Robert McClory wrote in the Reader piece. “On the road, he loved to drop in unannounced at his stores to see if operations complied with his requirements. He also regularly approached strangers on the street if they appeared to be hobbling, inquired about their feet, and offered to take them under his wing.

“According to an article in a 1961 Indiana business magazine, Scholl, then 79, still followed a Spartan routine of rising at 7 AM, grabbing a quick breakfast, and going to his office at the plant, where he would become so engrossed in a new advertising campaign or a new foot contraption that he’d forget about lunch and dinner and work on into the night. His one concession to advancing age was his agreement to take part of Sunday off.”

With his brother Frank leading the same kind of regimen in London, the Scholl Brothers truly conquered the world. In the years after World War II, the workforce at the Chicago factory had grown to roughly 800, but the company’s reach went far beyond that. There were satellite factories in Michigan City (Indiana), Jefferson (Wisconsin), Cincinnati, and globally in Frankfurt, London, Paris, and Buenos Aires, plus thousands of certified dealers selling their products in independent shops. By the company’s 50th anniversary in 1954, the Scholls owned 400 of their own “Dr. Scholl’s Foot Comfort” storefronts in 40 different countries, as well. Annual sales numbers topped $65 million by the time of William’s death in 1968, and would cross the $200 million threshold in the 1970s.

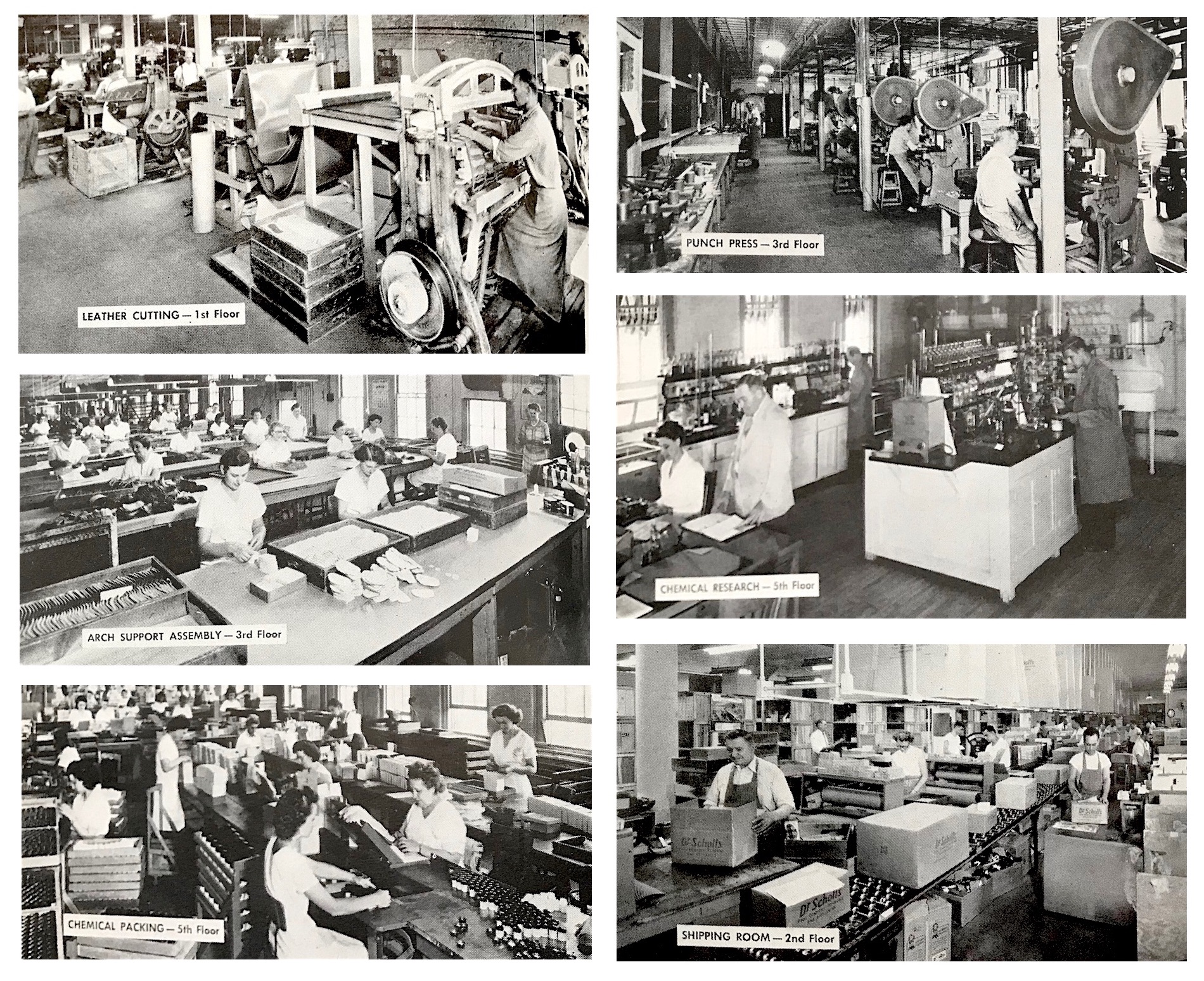

[A look at six of the departments inside Dr. Scholl’s Schiller Street factory in Chicago, 1954]

[A look at six of the departments inside Dr. Scholl’s Schiller Street factory in Chicago, 1954]

Since William had no children of his own, it was Frank’s son William H. Scholl who eventually took over the company presidency, seemingly on course to lead the family owned business—one of the largest such corporations in the world—into its next era. William H. took the company public for the first time in 1971 and watched it join the Fortune 500 list, but just eight years later, he made the surprising decision to sell the business to Schering-Plough HealthCare Products. The new owners kept William H. on as president of the international consumer products division until his retirement in 1984, but it doesn’t appear to have been a pleasant relationship.

Supposedly, many members of the Scholl family were none too pleased about how the sale of the business went down, nor how the Dr. Scholl brand was subsequently handled by Schering-Plough. Through a series of subsequent sales and acquisitions, the brand is now the property of the German drug giant Bayer, and all Dr. Scholl products—as you might guess—are produced not in Chicago, but in China.

The long-since closed Schiller Street factory, meanwhile, was one of the first Chicago industrial plants to get the “preservationist’s makeover” in the 1980s, re-opening as the “Cobbler Square Lofts” in 1985.

[Above: The Scholl MFG Co’s old Chicago headquarters in 1954, then transformed into its current form as the Cobbler Square Lofts. Below: A room inside Cobbler Square, where Foot-Eazers and Arch Fitters might once have been made]

The Philosophy Behind Dr. Scholl’s

from a 50th Anniversary company pamphlet, 1954

“Dr. Scholl’s is world-wide organization founded on a sound philosophy.

“Dr. Scholl’s is world-wide organization founded on a sound philosophy.

It is not the buildings that are the predominant part of Dr. Scholl’s—as imposing and efficient as they are.

It is not alone the harmonious, hard working men and women who comprise the organization—as efficient as they are.

It is not so much the comprehensive, beneficial training program—as effective as it is.

It is not alone the merchandise—as effective as it has been in helping millions to a happier, healthier life.

It is rather all of these things bound together by the spirit—the philosophy which the Doctor himself gives to the whole which is Dr. Scholl’s.

It is exemplified by the constant experimentation; the impatient drive to develop new products, to improve current products; the youthful, ‘never satisfied’ urge to step up methods, to increase production, widen distribution.

That is the youthful philosophy that makes Dr. Scholl’s 50 years young as it looks ahead; as it looks forward with determination to give the greatest good to the greatest number at the lowest possible cost.”

Curator Note: Many thanks to Vicki Matranga for donating the Dr. Scholl’s Arch Fitter to the Made In Chicago Museum.

[A chaotic stockroom scene at the Schiller Street plant, circa 1920]

[A chaotic stockroom scene at the Schiller Street plant, circa 1920]

[Foot Comfort Shop within the Schiller Street factory, including an Arch Fitter in the foreground]

[Foot Comfort Shop within the Schiller Street factory, including an Arch Fitter in the foreground]

SOURCES

Dr. Scholl: Foot Doctor to the World, by William H. Scholl, 2006

Around the World with Foot Comfort, by Scholl MFG Co., Inc., 1954

Uncle Doc: A Biography of Dr. William M. Scholl, Foot Doctor to the World, by John D. Scholl III, published by Kathleen K. Scholl, 2013

“Best Foot Forward,” by Robert McClory, Chicago Reader, 1994

U.S. Patent 997,707 – “Metal Forming Appliance,” 1911

Practipedic Reference Guide: A Modern Treatise on the Human Foot, by Wm. M. Scholl, 1921

Boot and Shoe Recorder, Vol. 59, May 31, 1911

Practipedics: The Science of Giving Foot Comfort and Correcting the Cause of Foot and Shoe Troubles, by American School of Practipedics and Wm. M. Scholl, 1917

“Moline Girl Killed in Auto Crash” – The Daily Times, April 7, 1927

“Moline Girl Killed in Georgia Auto Crash” – The Dispatch (Moline, IL), April 7, 1927

“Better Fitting Arch Supports” – The Shoe Retailer, Vol. 72, Sept. 18, 1909

A Course of Study in Scientific Shoe Fitting and Salesmanship, by Wm. M. Scholl, MD, 1929

“Scholl Inc.” – Encyclopedia of Chicago

The Feet and Their Care, by Dr. William M. Scholl, 1933

“Big Foot A Midwestern Doctor Found the Thrill of Victory in the Agony of De-Feet,” by Paul Lukas, CNN Money, 2003

“Dr. Scholl Leaves Gold Coast Legacy” – Chicago Tribune, April 30, 2003

“Cobbler Square: Surprising Complex May Mend the Soul of Old Town” – Chicago Tribune, August 11, 1985

“Scholl Foot Comfort Service” – Shoe and Leather Facts, Vol. 34, Oct. 1922

Archived Reader Comments:

“I just found one of the arch fitter’ s in an old clothing store I was helping clean out. It is in really nice shape. Thanks for the info!! I

I ” —MM, 2020

” —MM, 2020

“Awesome story about Dr. Scholl. They should make a movie about him . ” —Lindy, 2019

” —Lindy, 2019

“Muy completa la historia, aprendi mucho acerca del Dr.Scholl” —Jenny Giraldo, 2018

“fantastic story Andrew!!! so happy to see the history you discovered because of the donated arch fitter!! thank you!” —Vicki Matranga, 2018

Found 1 Foot Eazer

It is stamped THE SCHOLL Foot eazer (NOT Dr Scholl’s Foot Eazer)

PAT’D JULY 11 05 – FEB 25 08

“THE” is a smaller font that “SCHOLL”

Foot eazer is in Cursive

Any comments would be appreciated.

I have an antique display case which has “Scholl’s Foot Appliances” in frosted writing on the front glass. It measurers 20″ x 21″ x 11″ deep. I use it for displaying other small antiques. I bought it at a garage sale in Lincoln Park Michigan around 1973. Can you give me an appraisal of it’s value? I’ve never seen another one like it.

I have several unopened original manufactured products from the 70’s if you’d like to review for display purposes 1.e. Factory runs with errors ie label upside down. My mother, Su Schick, was hired in 1970. traveling 70% via Sales/Merchandising/Modeling to help introduce and build a team for the new exercise sandal and hosiery division of products. Have number of pictures from in store photo shoots highlighting products, presentation video,original sandals in box, business trip photo to London office etc. She loved her job, moved to Schiller and Lake Shore Dr to be close by, rose up the ranks and was with co for over 10yrs, eventually even moving to Memphis with the SP buyout.

Hello,

My grandmother had a Dr. Scholls Electric Foot Massager – Pat. D 185.322.

From a family of incredibly bad foot issues… any thoughts on what the best place for this is? 🙂

I have an old telephone table with matching chair that fits under the table. It has a metal label on it that says “Scholl’s Chicago”. I wondered if Scholl’s manufactured furniture or maybe it was just identifying that it belonged to Scholl’s?

Any information would be appreciated or maybe something the museum would be interested in. Thank you

My grandfather had a pair of the metal/leather riveted insoles. the patient number can plainly be made out. I was curious as to what they may be worth

I have a podiatry chair that needs a new home

My father and brother and myself are podiatrists Rock Island, IL

Hello my name is Hattie Whiteside-Lucas. My mother Bennie Whiteside passed January 15, 2019. Upon going through her things, I ran across an old foot massager, Cat. No. 411, Serial Number 595833. And, it still works.

This would look great in your museum of item. If you’re interested you may contact me at the information below.

Thank you for your many inventions

I am President of the La Porte County Historical Society in La Porte, Indiana. We have a large museum in La Porte with 3 floors of exhibits. I would like to have a small exhibit dedicated to Dr. William Scholl and his life and works. He was born and reared in La Porte County and was one of 13 children in the Scholl family who had a large dairy farm. We have a large display of artifacts about the Scholl Dairy business. He spent his summers on the farm in La Porte. He stayed in a modified refrigerator box car! It was his favorite place to spend his free time. It is actually still there! I would like to know where I can go for help in organizing a display. Where would I find artifacts? Where would I contact the Scholl Company today? Any help would be appreciated!