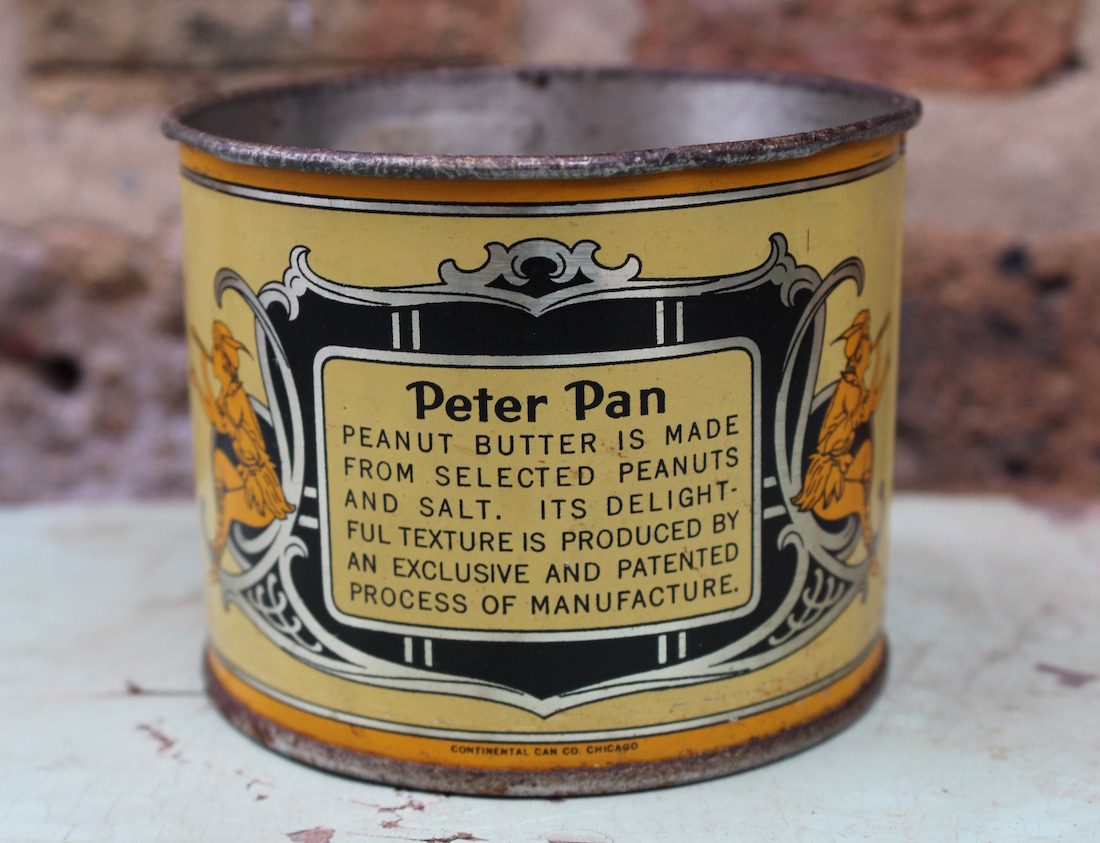

Museum Artifact: Peter Pan Peanut Butter Tin, 1920s

Made By: E.K. Pond Company / Derby Foods, Inc., 517 W. 24th Street, Chicago, IL [Chinatown]

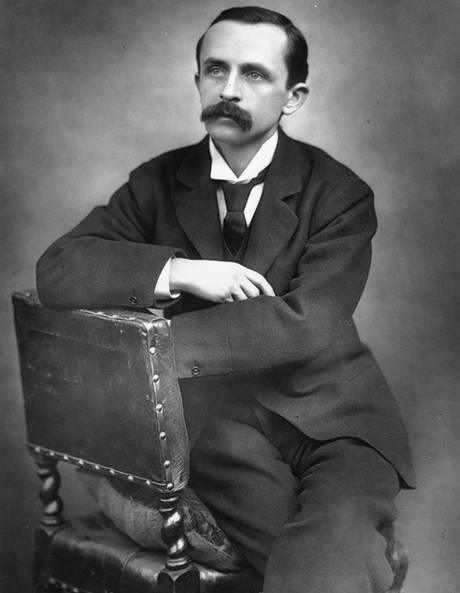

In 1929, the Scottish novelist and playwright J.M. Barrie made a charitable contribution the likes of which we may never see again in the modern age of intellectual property. And it didn’t have anything to do with peanut butter.

Having already enjoyed international acclaim for his various tales of Peter Pan, “the boy who wouldn’t grow up,” an aging Barrie decided to donate the copyright of his entire Pan franchise—including all royalties from any future uses of the character—to the Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital in London. A sincere and selfless act, indeed.

What Barrie almost certainly didn’t realize, however, is that the Peter Pan brand had already quietly slipped from his grasp on the other side of the Atlantic. One year earlier, in 1928, Chicago’s E.K. Pond Packing Company had unashamedly slapped the character’s name on its new line of hydrogenated peanut butter, apparently without making the slightest attempt at properly licensing it from its creator.

E.K. Pond’s parent company, Derby Foods, had been trying to gain a foothold in the fast-growing peanut butter industry for years, but their “Yankee” and “Toyland” brands had mostly fallen flat. Finally, with a Peter Pan theatrical production running concurrently on Broadway and causing a sensation, Pond president George Cantine Case (A+ name) basically threw caution to the wind and made the leader of the Lost Boys into his new corporate mascot.

An equivalent act in today’s marketplace couldn’t leave a boardroom before a team of lawyers would show up to muzzle the guy who even suggested it. In the 1920s, however, news traveled a wee bit slower, and by most accounts, there is no evidence that J.M. Barrie himself ever knew that Peter Pan Peanut Butter even existed. He died in 1937, before the brand reached wider recognition through radio and TV advertising. I suppose it’s also possible that the protectors of the Pan copyright saw the Chicago product as a harmless form of promotion for Barrie’s works. Whatever the dynamic, Peter Pan—the American canned food—somehow managed to successfully live rent-free in the slipstream of Peter Pan—one of the world’s most valuable creative properties.

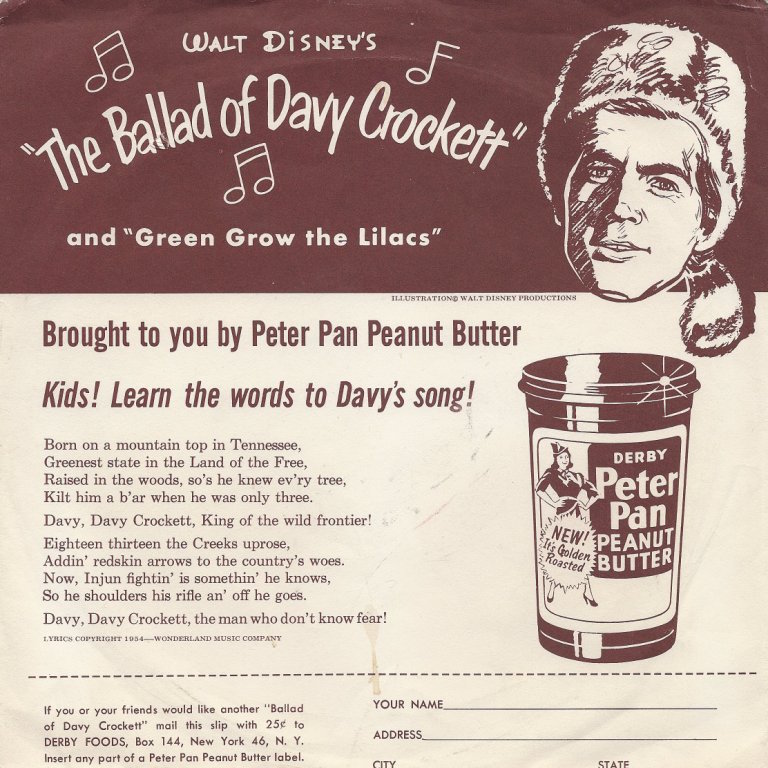

Stranger still, it’s basically carried on like that for 90 years. There is no record of E.K. Pond Company or its better known parent company Derby Foods ever being taken to court or paying overdue royalties to the Great Ormond Street Hospital—an institution that was fruitfully funded by Barrie’s copyrights well into the 21st century. Today, a lot of the Pan works have shifted into the public domain, opening the door to a free-for-all (Peter & Wendy & Zombies is surely on its way). But back in the day, even Disney had to pay licensing fees on this stuff!

[Disney paid licensing fees to make an animated Peter Pan film, but they also had promotional ties to Peter Pan Peanut Butter, which didn’t pay said fees for the same theoretical trademark. . . ???]

[Disney paid licensing fees to make an animated Peter Pan film, but they also had promotional ties to Peter Pan Peanut Butter, which didn’t pay said fees for the same theoretical trademark. . . ???]

With all this in mind, the sustained, successful existence of Peter Pan Peanut Butter might be one of the truly great (or awful) marketing swindles of all time. Just don’t blame or credit the original E.K. Pond himself for any of it.

*****

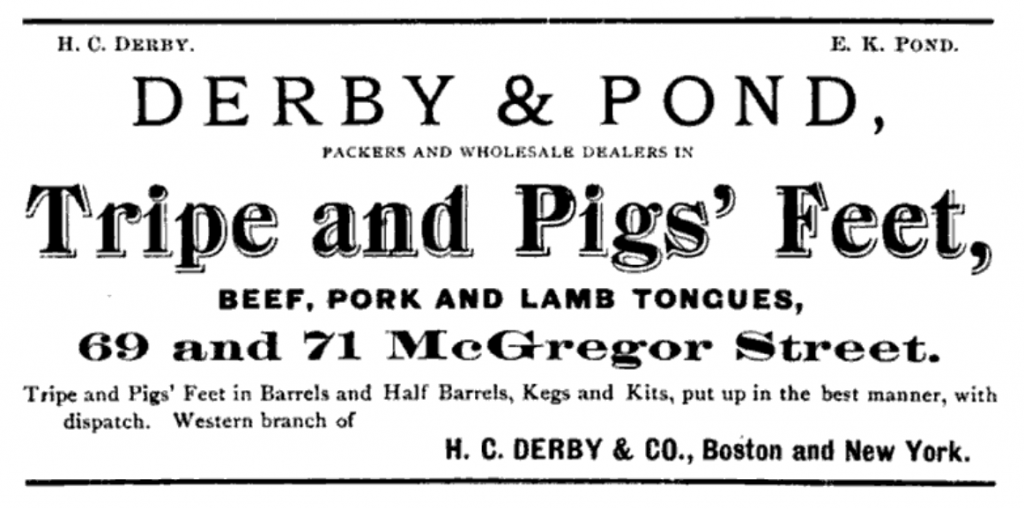

The company namesake was born Edmund Kirke Pond in Massachusetts in 1841. He died in 1900, well before Peter Pan—or modern spreadable peanut butter—had entered the public consciousness. Mr. Pond had headed west to Chicago around 1870, just before the Great Fire. He was hired by his cousin Henry Clay Derby to run the western interests of Derby’s east coast meat packing company. An 1870 directory identifies this fledgling Chicago business as “Derby & Pond: Packers of Tripe.” And yes, that might be the single best business description I’ve come across during three years of research.

[Derby & Pond ad from the 1876 Lakeside Annual Directory of Chicago]

[Derby & Pond ad from the 1876 Lakeside Annual Directory of Chicago]

In any case, this venture morphed into the E.K. Pond Company in 1888, still under the Derby banner. After Edmund Pond’s death, H.C. Derby then decided to sell out to one of the supergiants of the Union Stockyards, Swift & Company. Swift was arguably the number one meat producer on the planet, with $200 million in profits in 1903. They employed about 23,000 people across the country, including over 5,000 workers at their Chicago slaughtering plant. You might know the company better from the gruesome workplace horrors described in Upton Sinclair’s 1906 novel/expose, The Jungle.

Anyway, Swift & Co. would continue to operate both the Derby and Pond companies for decades, but they tended to keep a low profile about it. Teddy Roosevelt had started a movement cracking down on monopolies in the food industry, and some of the big players began keeping their subsidiary connections a little more in the shadows from that point forward.

[“Toyland” Peanut Butter was one of Derby/Pond’s early failed brands before Peter Pan]

[“Toyland” Peanut Butter was one of Derby/Pond’s early failed brands before Peter Pan]

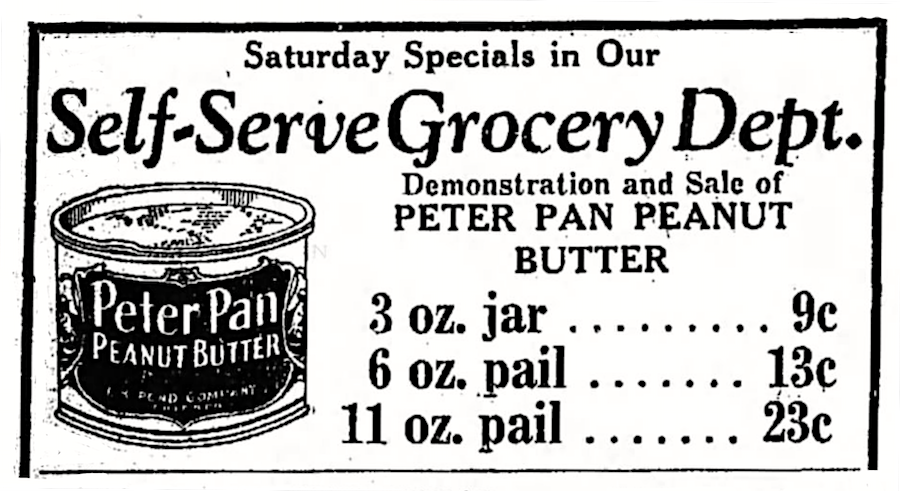

Derby Foods first started making peanut butter under the E.K. Pond Co. name around 1915, when a weak cotton crop in the South was creating a big boom in peanut farming. In 1923, they scored a major win by getting the inventor Joseph Rosefield to license them his new formula for hydrogenated peanut butter.

Before that point, peanut butter had a far shorter shelf life, as the peanut oil would separate out from the solid peanuts and pool at the top of a container, quickly going rancid. Refrigeration could keep it fresh longer, but basically nobody owned a refrigerator during the Harding administration. With new developments from experimenters like Rosefield, Frank Stockton and others, peanut butter suddenly emerged as a non-perishable item, fit for shipping across the country and sitting freely on grocery shelves for weeks. It also had a new creamy consistency, perfectly aligned in history with the arrival of sliced bread.

George Cantine Case, who’d come up working in the stockyards for the company that would become Wilson Sporting Goods, recognized the game-change that hydrogenation represented. Increasing production at Derby/Pond’s 24th Street factory, he worked with Rosefield on getting the formula perfected and establishing west coast distribution. He also hired Chicago’s Continental Can Company to create the original Peter Pan tin can, with its unique turn key / re-closable lid. Our artifact doesn’t have its lid, or any peanut butter left in it (thankfully for all you peanut allergy patrons out there), but it certainly still shows off some pretty stunning design work.

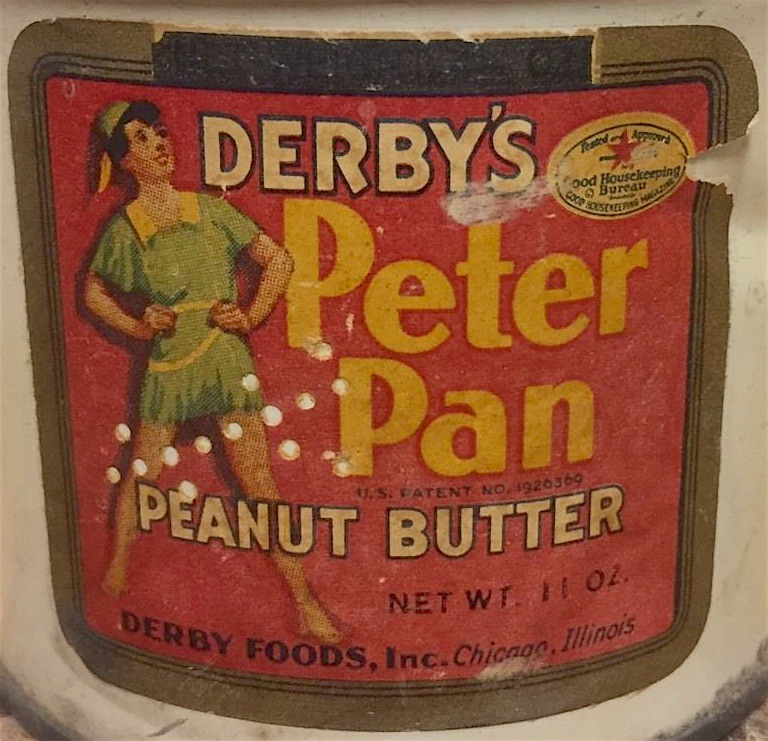

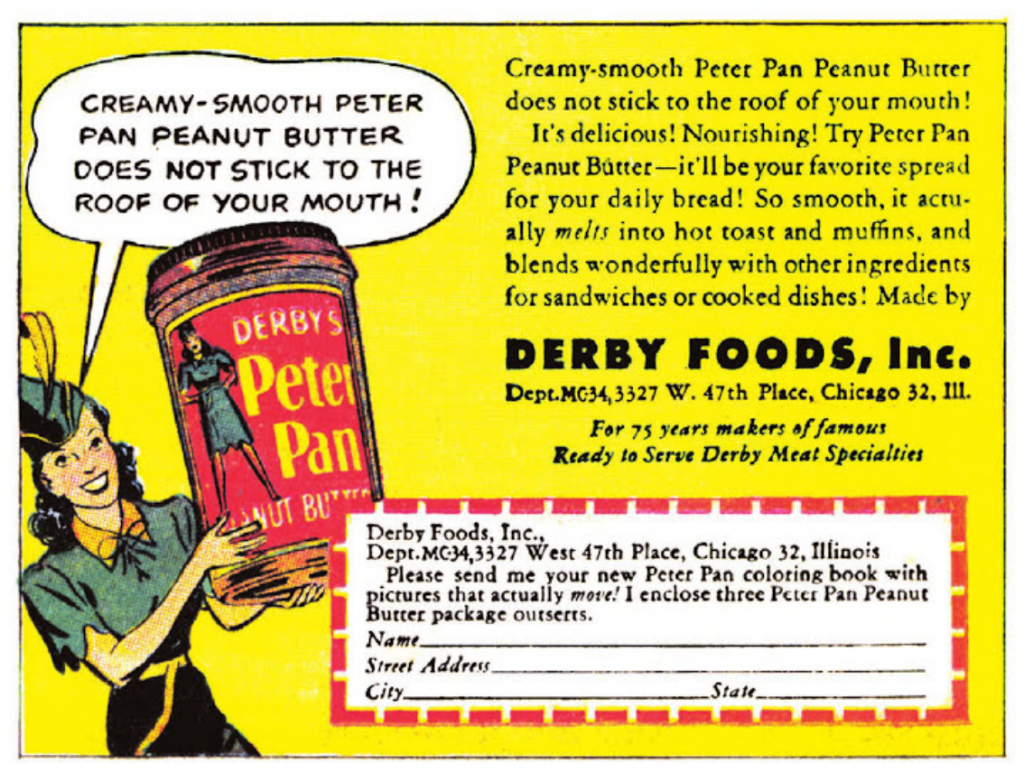

In later years, after the E.K. Pond Co. was scrapped and the product flew under the Derby Foods name, the label and advertising imagery were based more on the popular theatrical version of the Peter Pan character—routinely and kind of weirdly portrayed by a grown woman (Mary Martin, Sandy Duncan, Cathy Rigby, etc.). Containers shifted from tin to glass to plastic, and a deal was eventually worked out with Disney to start using their slightly less creepy Peter Pan depiction (an actual boy) after the 1953 film. From there, heavy TV advertising and show sponsorships made Peter Pan one of those classic, ubiquitous American food brands.

[1950s Peter Pan TV ad with an assist from Tinkerbell]

Much like a poorly made PB&J, though, the history of Peter Pan Peanut Butter tends to get a bit sloppy around the edges. Along with that whole questionable trademark business, the company has also had to survive salmonella-related recalls, lawsuits, numerous ownership changes, and a bit of an increasingly second-tier reputation. Even way back in 1932, following George Cantine Case’s unexpected death, the company responded by trying to shortchange Joseph Rosefield on his hydrogenation licensing fees. Rosefield, understandably miffed, jumped ship to create his own national brand. He called it Skippy, and it eventually moved past Peter Pan as the nation’s top-selling peanut butter in the 1940s, only to be surpassed by the new kid on the block, Jif, in the 1960s.

[Former Derby Foods factory at 3327 W. 47th Place in Brighton Park]

[Former Derby Foods factory at 3327 W. 47th Place in Brighton Park]

From at least the early 1940s onward into the 1980s, Derby Foods, Inc. operated a large factory in Brighton Park at 3327 W. 47th Place, which produced Peter Pan along with Derby Tamales and some other goods. The building is still standing and looks like it could be yours for the right price!

As of 2016, the Peter Pan brand is back home in Chicago, sort of, as its latest parent company, ConAgra, relocated to the city from Nebraska. It’s hard to say that J.M. Barrie would be proud, but I suppose in a roundabout way, Peter Pan Peanut Butter is helping its titular character achieve his dream in the real world—living forever without growing up.

Sources:

Creamy and Crunchy: An Informal History of Peanut Butter, the All-American Food, by Jon Krampner

Peanuts: The Illustrious History of the Goober Pea, by Andrew F. Smith

New Yorker: “A Chunky History of Peanut Butter” by Jon Michaud

Archived Reader Comments:

“My Aunt Mary, Mary Serritella and Dorthy La Guardia worked at Derby foods from 1935 to 1973.. They used to bring the canned tamales and peter pan peanut butter to us kids. I was watching an old show- George Burns and Gracie Allen , when I saw the old ad for Peter Pan. I never really knew where they worked at in Chicago. We grew up near Harlem and Irving.” —David Palmer / Serritella, 2019

“Eat peanut butter anytime you can, but only if it’s Peter Pan.” —Debby, 2018

“Picky people pick Peter Pan peanut butter, it’s the peanut butter picky people pick ” –-Colleen Fendt, 2017

” –-Colleen Fendt, 2017

How has Peter Pan Peanut Butter been helping its namesake character live forever in the real world without growing up?

I worked at the plant from 1950 to 1953 in Brighton Park. Derby food Pritchard was plant manager.they were trying to produce cake frosting at that time.

I have an old tin of Derby Peter Pan Peanut Butter and I am trying to figure out how old it is. I am assuming since it is a tin that is from before WWII, but not positive. The front label is silver with all writing in white except Peter Pan, which is in yellow. And the lady Peter Pan to the left of the label is kind of tipped towards the label, as if presenting it. I haven’t been able to find any photos of one like it. Any help on dating it would be appreciated.

I have a one gallon square glass jar with a large metal lid that says Peter Pan pnuttiest! and smooth. I have not been able to find out when it was made and have not seen another like it online. Can someone please respond?

I was just checking to see the value of the Toyland Peanut Butter tin from E K Pond Co in Chicago vs the same one from Derby Co. This was very interesting. I have the tin with top and handle.