Museum Artifact: “Blind Dates” Arcade Collector Cards, 1941

Made By: Exhibit Supply Company, 4222-4230 W. Lake Street, Chicago, IL [West Garfield Park]

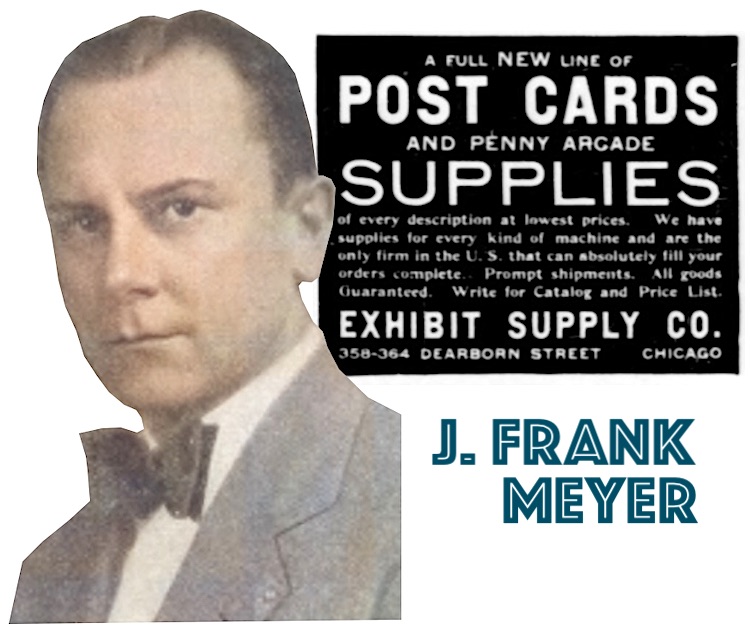

“One cannot mention the words ‘penny arcade’ without thinking of the Exhibit Supply Company of Chicago. For over twenty-seven years its president, Mr. J. Frank Meyer, has been engaged in his tireless task of advancing the arcade business. Today, the acorn of more than a score of years ago has developed into a giant oak tree and the Exhibit Supply Company has become the symbol of all that is fine in the line of penny arcade machines.” —Bernard Madorsky (Eastern Distributor for Exhibit Supply Co.), 1928

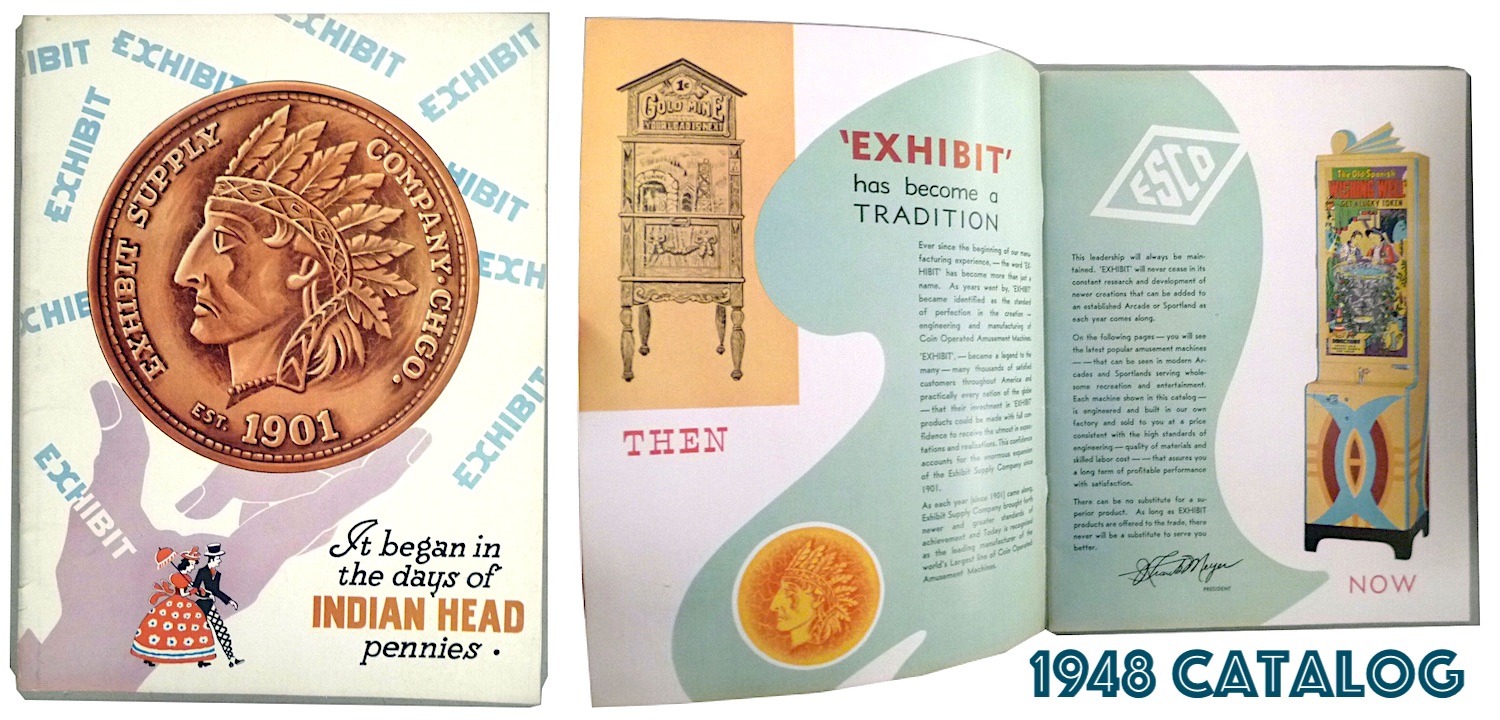

Founded in 1901, the Exhibit Supply Company (aka, ESCO) was one of the many arcade machine manufacturers that made Chicago the central hub of all things coin-operated in the 20th century. The firm produced a well-rounded mix of “amusements” well into the 1950s, including candy venders, diggers (aka claw machines), shooters, strength testers, and fortune tellers. What really distinguished the business from some of its rivals, though, was its dual role as a publishing house—millions of novelty picture cards were printed and shipped out of its Chicago plant on a regular schedule, designed exclusively for re-stocking ESCO’s own dispensing machines.

Founded in 1901, the Exhibit Supply Company (aka, ESCO) was one of the many arcade machine manufacturers that made Chicago the central hub of all things coin-operated in the 20th century. The firm produced a well-rounded mix of “amusements” well into the 1950s, including candy venders, diggers (aka claw machines), shooters, strength testers, and fortune tellers. What really distinguished the business from some of its rivals, though, was its dual role as a publishing house—millions of novelty picture cards were printed and shipped out of its Chicago plant on a regular schedule, designed exclusively for re-stocking ESCO’s own dispensing machines.

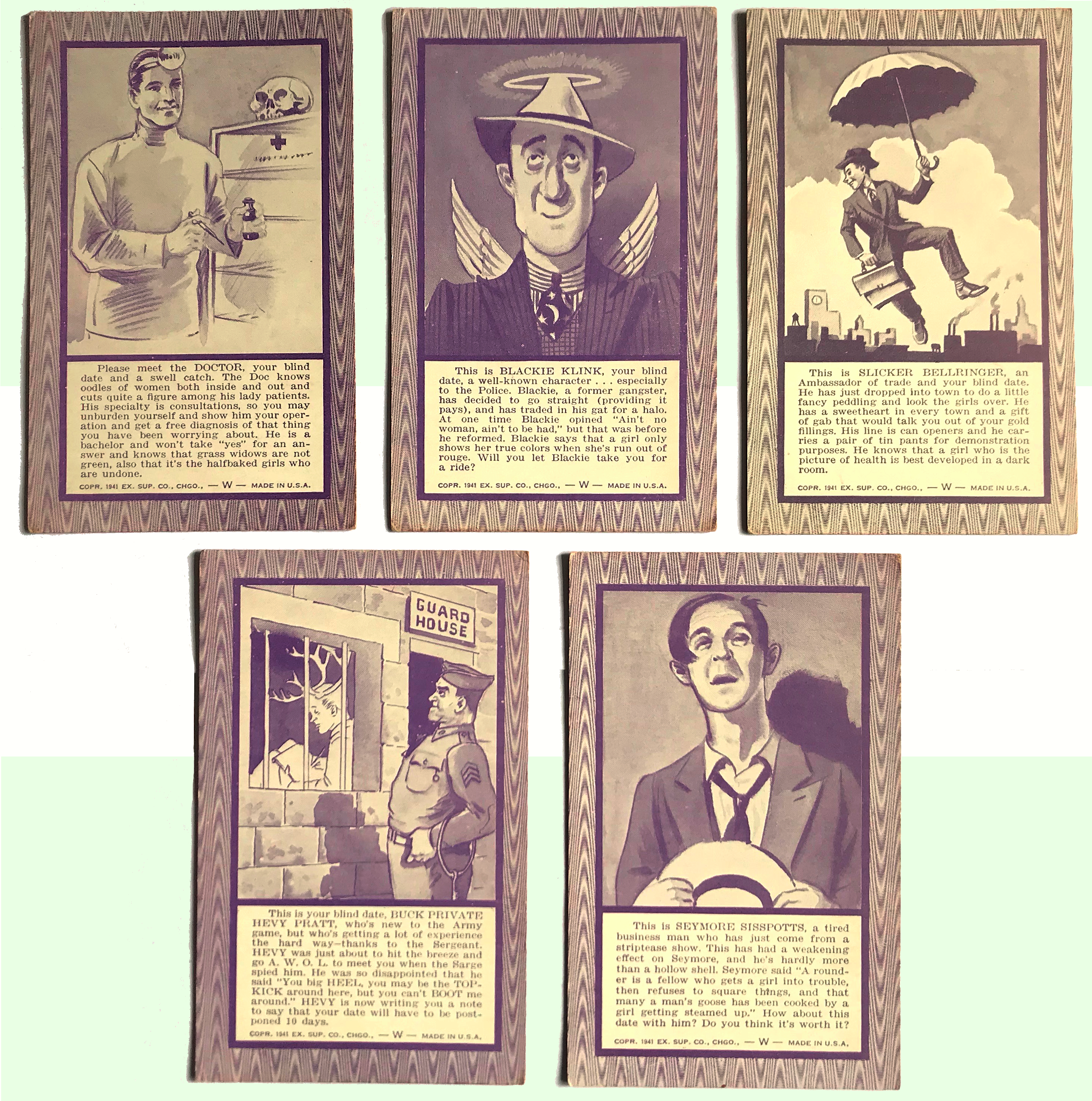

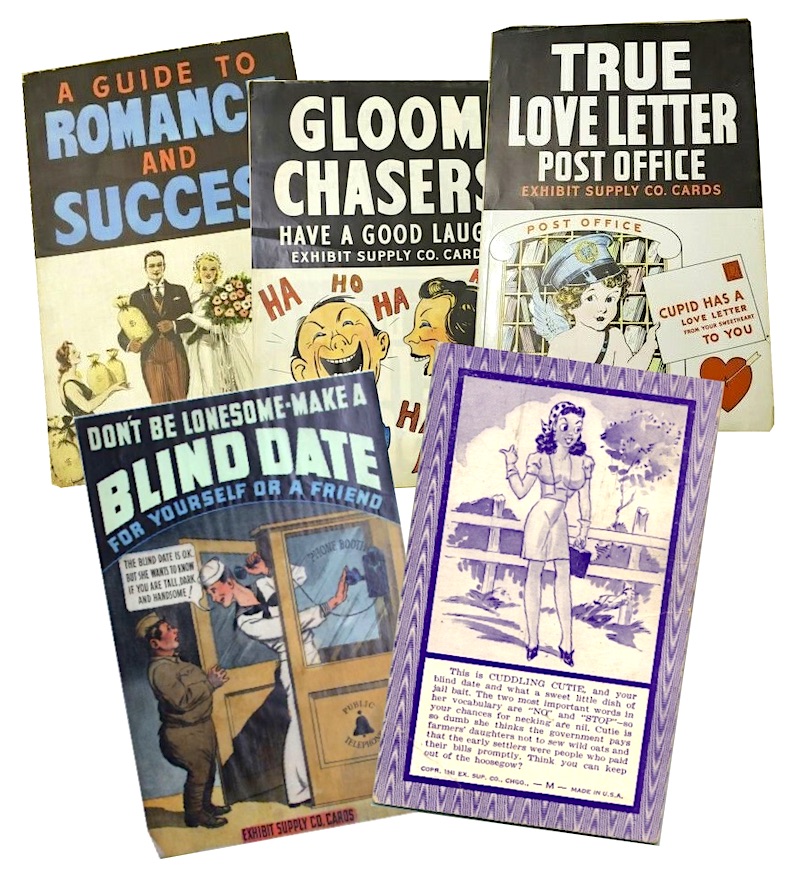

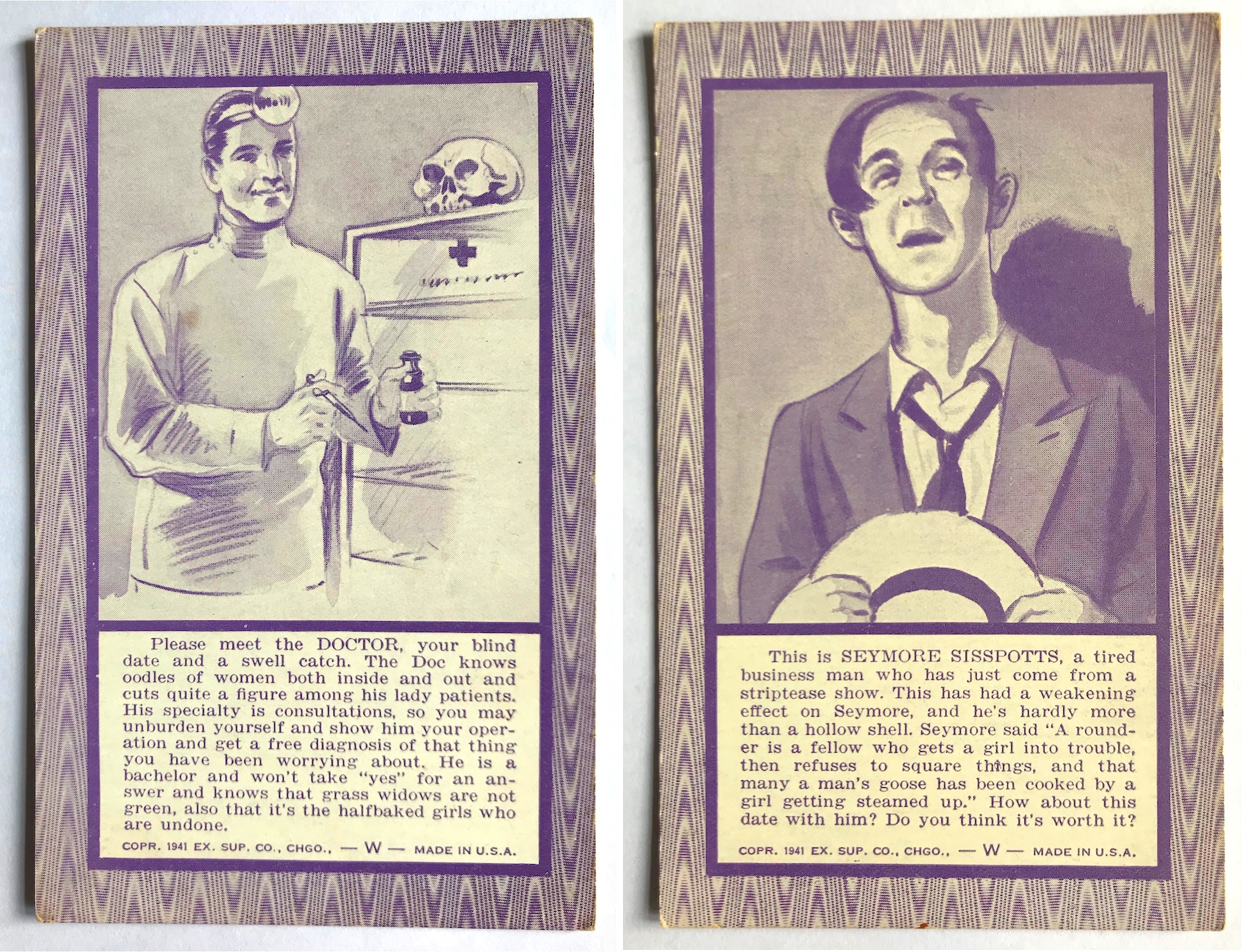

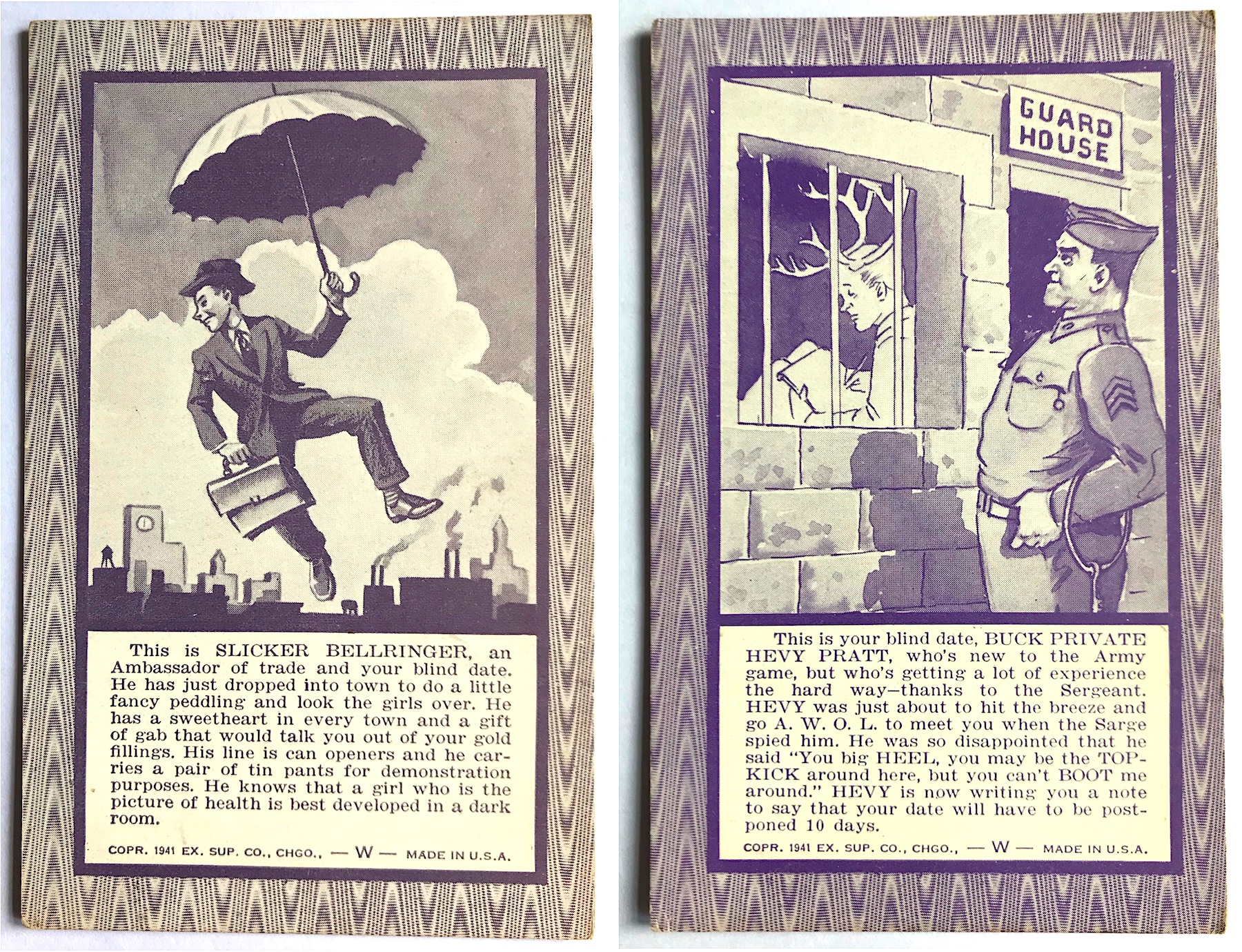

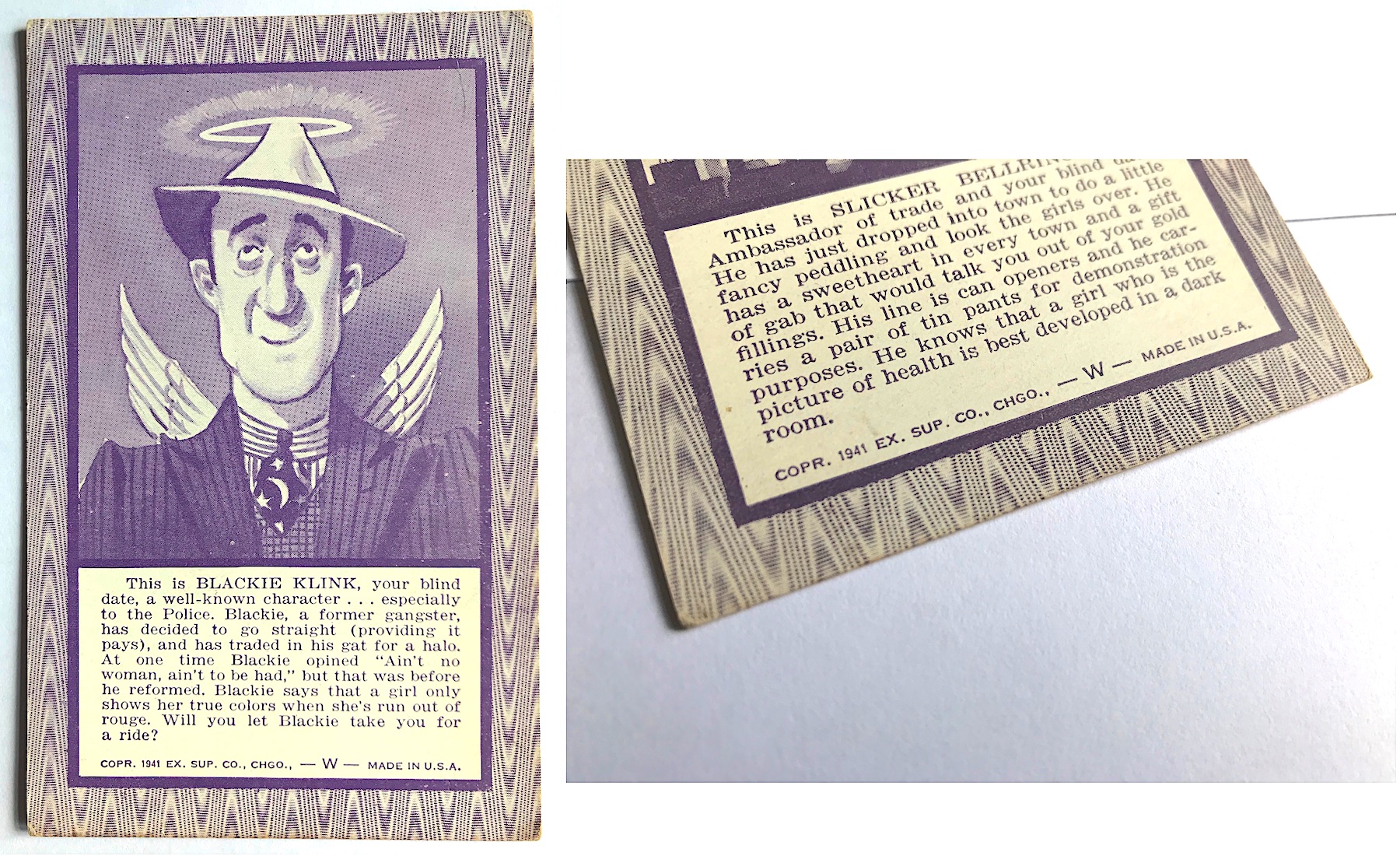

Printed on thick-stock postcard paper, this style of card (which is still referred to by collectors as “exhibit cards”) featured everything from boxers and baseball players to film and radio stars. There were also unique comedy-themed collector sets that could be used to give any old vending machine a new gimmick, such as the “Blind Date” character cards in our museum collection (published in 1941), which offered up goofy profiles of various undesirable bachelors and bachelorettes—sort of like a satirical prophecy of what would eventually become our online dating reality.

“This is Blackie Klink, your blind date,” reads one of the cards in our collection, featuring a Capone-esque fellow in a pinstripe suit and a fedora, “he’s a well known character . . . especially to the police. Blackie, a former gangster, has decided to go straight (providing it pays), and has traded in his gat for a halo. At one time Blackie opined ‘Ain’t no woman, ain’t to be had,’ but that was before he reformed. Blackie says that a girl only shows her true colors when she’s run out of rouge. Will you let Blackie take you for a ride?”

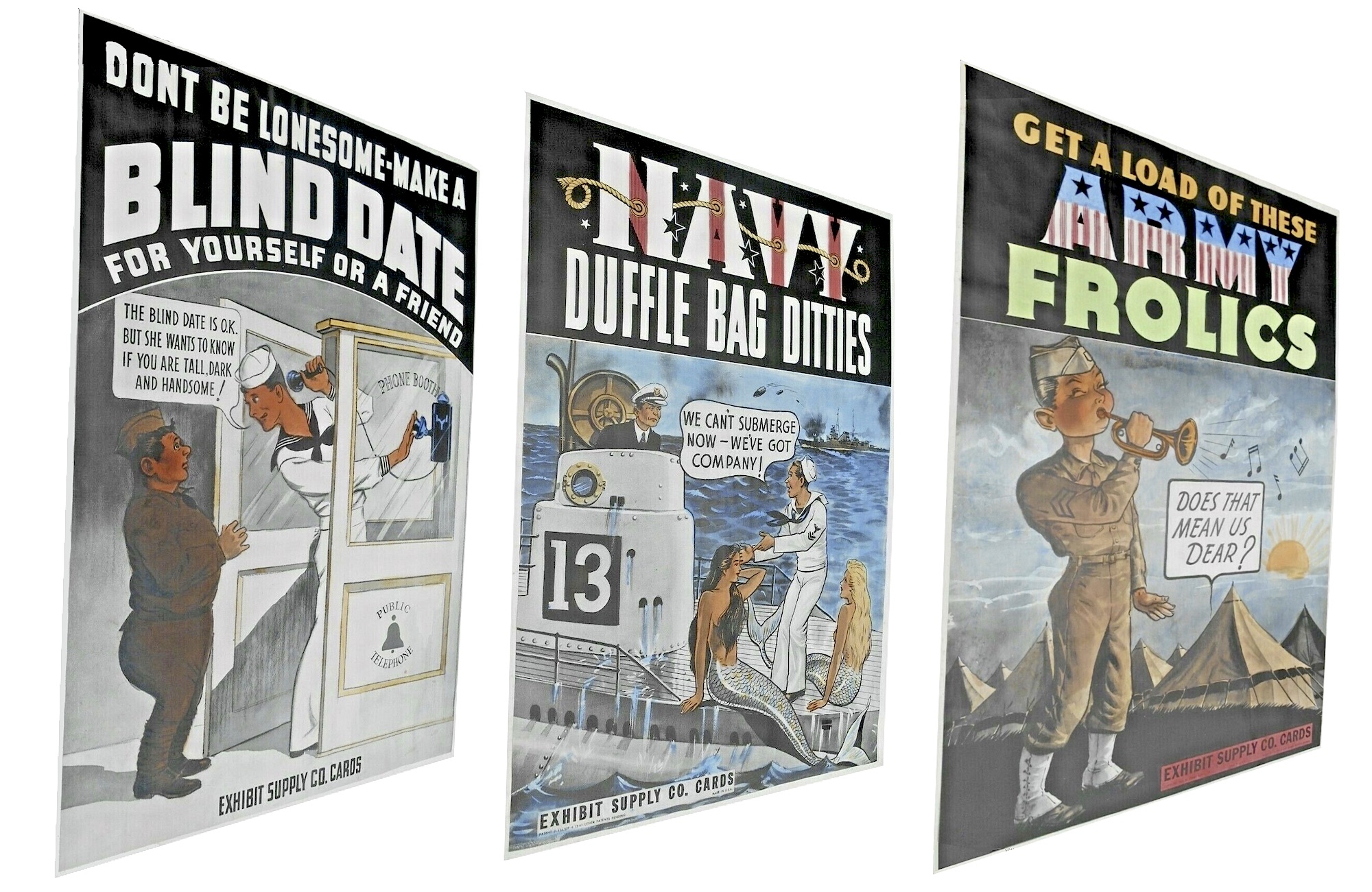

[Promotional posters for three of Exhibit Supply’s 1940s comedy card sets: “Blind Date,” “Navy Duffle Bag Ditties,” and “Army Frolics”]

Exhibit Supply’s founder and president J. Frank Meyer wisely recognized that the best way to keep his brand profitable in perpetuity was to manufacture not just merchandising machines, but most of the merch that went into them. The hard part was getting his distributors, operators, and the gaming public to respect that sound business model.

To stay ahead, ESCO tip-toed into risque subject matter in the 1920s; adjusted to crackdowns on “gambling games” in the 1930s; and jockeyed for defense contracts in the 1940s. For a while, they were almost certainly the biggest amusement supplier on Earth, but over time, much like trying to snag a stuffed animal in a claw machine, frustration proved more dependable than rewards. Surpassed after the war by local rivals like Bally, Gottlieb, Rock-Ola, and Seeburg, the Exhibit Supply Company became a bit of a forgotten name in American gaming history. But if not for ESCO’s contributions in the pre-pinball age, many of those other companies might not have a marketplace in which to thrive.

[Exhibit Supply display from an industry trade show, c. 1941]

History of the Exhibit Supply Co., Part I: A Pioneer Industry

While the company always listed its establishment date as 1901, we’ve yet to find firm evidence of a business advertising itself under the Exhibit Supply name until 1907. Prior to this, John Frank Meyer (born 1881 in Peoria, IL) ran a small printing firm in the Pontiac Building on Printer’s Row, staffed by five employees. From the looks of things, Meyer—who was still just in his early 20s— discovered an intriguing niche demand for arcade merchandising, and swiftly re-established the Meyer Printing Company as the Exhibit Supply Company with the goal of cornering that market.

“A full new line of post cards and penny arcade supplies of every description at lowest prices,” read a 1907 ad in Billboard. “We have supplies for every kind of machine and are the only firm in the U.S. that can absolutely fill your orders complete.”

“A full new line of post cards and penny arcade supplies of every description at lowest prices,” read a 1907 ad in Billboard. “We have supplies for every kind of machine and are the only firm in the U.S. that can absolutely fill your orders complete.”

Operating out of that small printing office on Dearborn Street, Exhibit “started on a shoestring as a pioneer industry,” as J. Frank Meyer described it in a 1941 advertisement marking the company’s 40th anniversary. “It was an IDEA in the head and heart of a skinny boy of twenty whose only resources were unbounded ambition, the will to get ahead, and the urge to create a new field of endeavor. I humbly admit that that boy never got beyond the fifth grade in school, but he did have initiative and determination and that same opportunity to succeed which is still the heritage of every American boy.”

When Meyer refers to a “pioneer industry,” he’s talking about the penny arcade, which had evolved out of traditional carnival entertainment with a new emphasis on mechanical games and consoles that visitors could pay to play via a coin slot—no human operators required. Not necessarily family friendly, many arcades of the early 1900s enticed a mix of gamblers, rebellious youngsters, and thrill-seekers, with many flocking to brand new inventions like the the slot machine and the Mutoscope—the latter of which was many folks’ introduction to “moving pictures.” Unsurprisingly, when men found a way to sell the first movies, they just as quickly made scantily clad women a common subject.

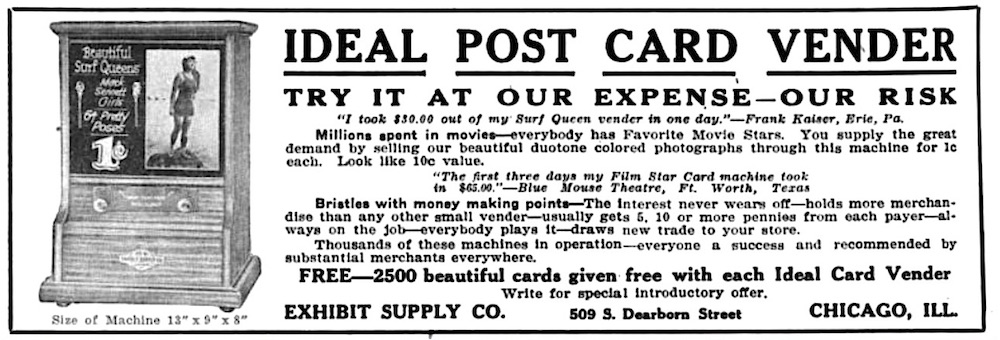

Exhibit Supply existed in this same universe, but their specific specialty was card vending machines, the kind which would ask for a penny and then dispense your fortune or a picture of a lovely lady. J. Frank Meyer started out as a supplier of amusement cards only, but by 1917, he was rapidly developing his own line of machines, as well—promoting them with bold promises of a 300% profit for any arcade operator who purchased one.

[A 1921 ad for Exhibit’s “Ideal Post Card Vender,” which “bristles with money making points”]

“Here is your opportunity to make a small investment and get the Big Money Machine with 3,500 cards,” a 1917 ad read. Meyer priced his 6-foot tall, oak cabinet machine at $25, so—with 3,500 pre-stocked cards selling at 1-cent a piece—the operator was guaranteed a $10 profit right out of the gate. Exhibit Supply made its money by ensuring its machines could only be restocked with official Exhibit cards, which had very precise dimensions (operators were routinely warned that using unauthorized cards could result in jammed, broken mechanisms).

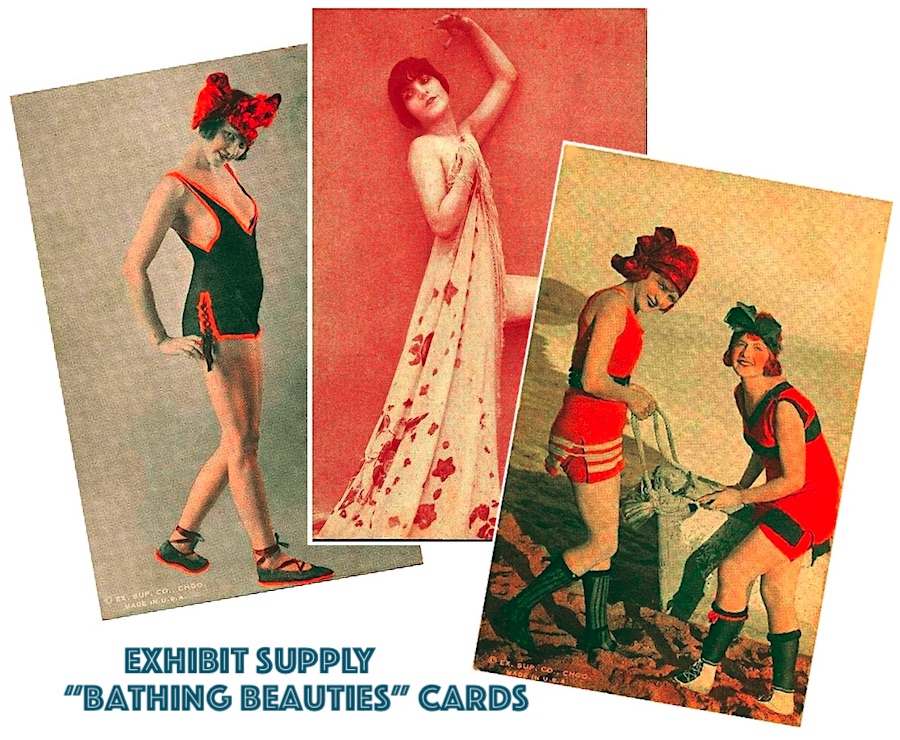

Of course, in order for this business model to work for everybody involved, you had to count on the general public consistently spending their precious loose change. This is where content was paramount, and when it came to arcade cards—much like the flickering Mutoscope films—sex appeal was the best bet. Not only did Exhibit promote countless semi-risque images of “art models” and “bathing beauties,” they also could get away with charging a nickel for some of them, rather than the usual penny.

Early to the idea of collectable cards, ESCO didn’t use flimsy throwaway paper or inks, either. Their cards were “almost equal to photographs in appearance” and were “printed in beautiful duotone ink on heavy white cardboard,” which explains why so many are still in circulation today.

Early to the idea of collectable cards, ESCO didn’t use flimsy throwaway paper or inks, either. Their cards were “almost equal to photographs in appearance” and were “printed in beautiful duotone ink on heavy white cardboard,” which explains why so many are still in circulation today.

In 1921, Exhibit Supply reported having “upwards of 5,000” card vending machines in use across the country, selling about 40 million cards annually. Up to that point, most of their clients had been operators of arcades or amusement parks, such as Chicago’s famed Riverview Park. The popularity of arcades was actually waning by this point, however—with strong competition from new movie palaces. The restrictions of Prohibition also cut off some of the coin-op industry’s booze-fueled clientele. To adapt, Exhibit Supply started producing smaller novelty machines for use in drug stores and soda fountains, under names like the “Ideal” Post Card Vender, “Lucky” Photo Vender, and “Gem” Post Card Vender.

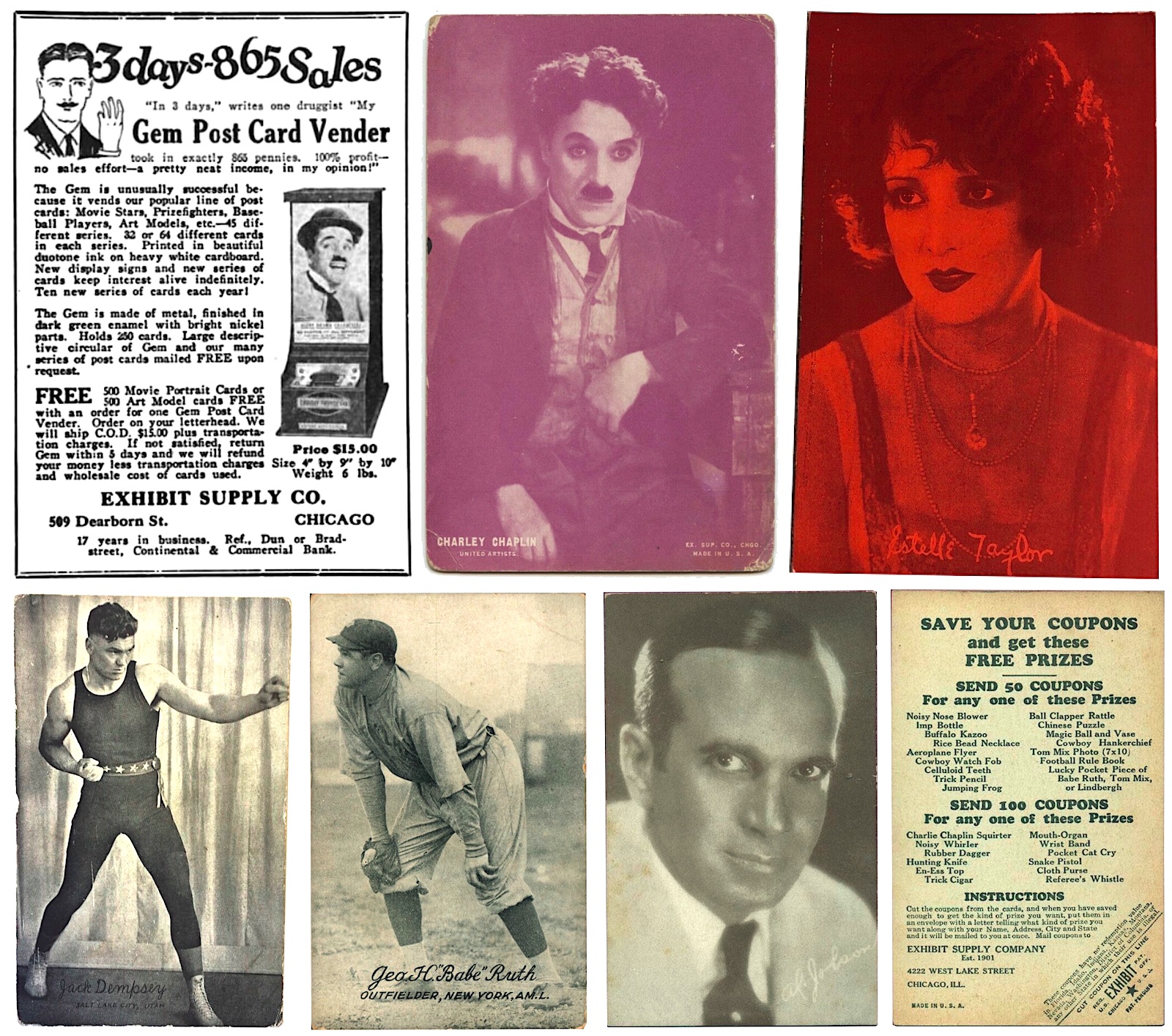

There was also a new campaign in the early ‘20s to start printing the likenesses of celebrities and athletes. Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb were quickly immortalized, as were prizefighters like Jack Dempsey, silent film stars Charlie Chaplin and Gloria Swanson, and various other cowboys, swashbucklers, flapper girls, and strongmen. While Exhibit cards aren’t as sought after as some other bubble gum and cigarette cards of the era, some of the bigger names will easily go for thousands of dollars in today’s collector market.

[Top Row: 1924 ad for Gem Post Card Vender, Exhibit cards for actors “Charley” Chaplin and Estelle Taylor. Bottom Row: Cards for 1920s icons Jack Dempsey, Babe Ruth, and Al Jolson, plus the back of Jolson’s card, promoting additional prizes available from Exhibit Supply.]

II. Legitimate Legal Procedure

“Exhibit machines are so well known that it is hardly necessary for us to dwell on their superior merits. We prefer that our customers do this—their name is legion. Thousands of them are enjoying large incomes derived from the operation of Exhibit machines, either in public locations where machines are placed on shares or in penny arcades at amusement parks, carnivals, beaches, etc.” —J. Frank Meyer, Exhibit Supply Co. catalogue, 1929

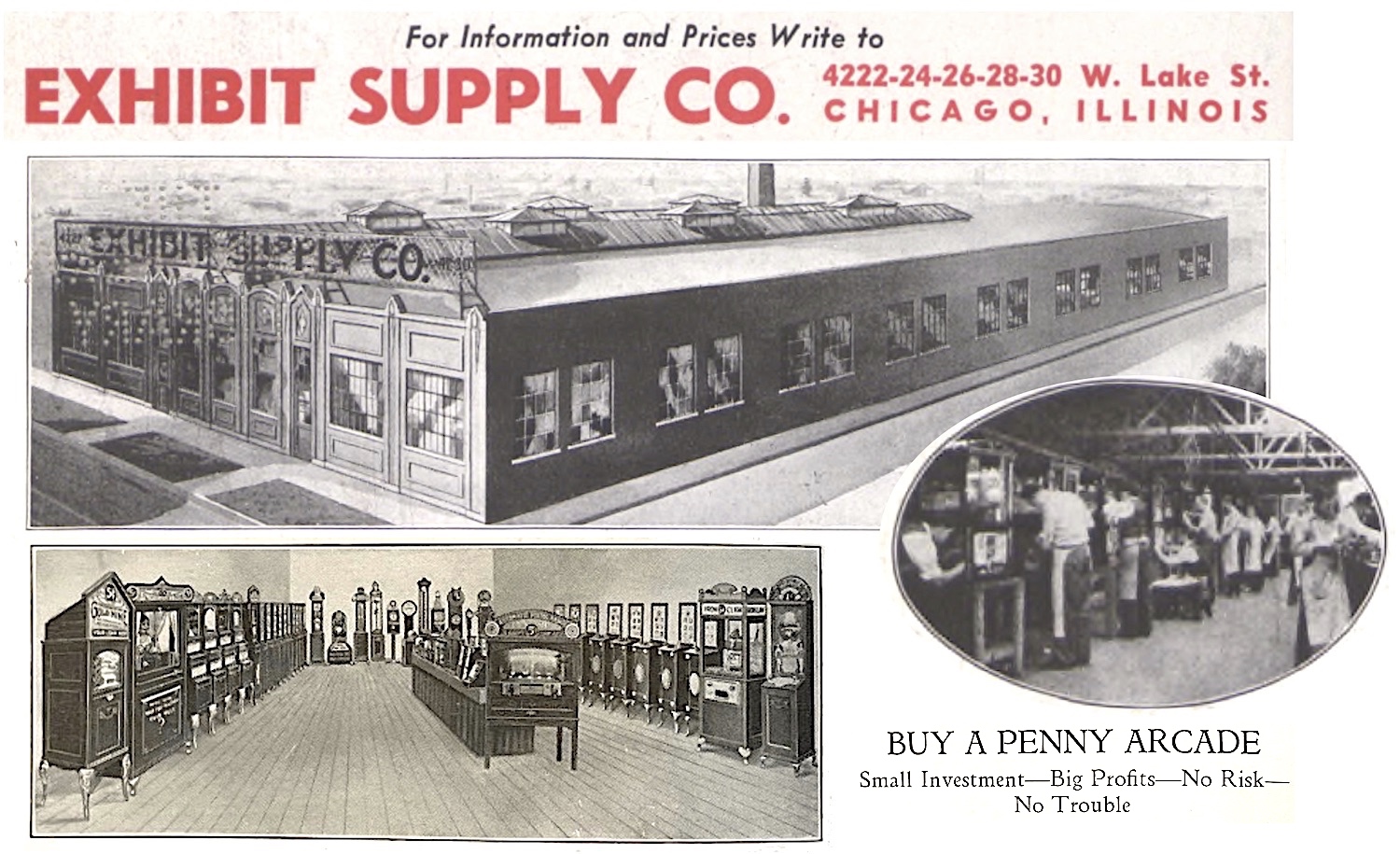

By the time of its 25th anniversary in 1926, the Exhibit Supply Company had relocated from South Dearborn Street to a new factory at 4222-30 West Lake Street in West Garfield Park; a facility that would eventually employ more than 250 workers. The company was, by now, at the top of its industry, producing dozens of different types of machines—so many that they claimed to be “the only concern in the world who have sufficient variety to equip a complete penny arcade”—a full-scale service they happily offered in their catalogs.

[The Exhibit Supply factory at 4222 West Lake Street, pictured above, was the company headquarters from the early 1920s through the 1950s. The building has long since been demolished.]

Where once J. Frank Meyer had been an ambitious youngster taking a risk on his own, he was now a middle-aged family man with a large staff of employees and an experienced management team. No member of that team was more valuable than sales manager Perc Smith, whom Meyer had recruited away from the Mills Novelty Company in 1918. Smith would spend the next 30 years with ESCO, putting together its catalogs and leading its arcade division.

Both Meyer and Perc Smith traveled the country throughout the 1920s, glad-handing with big arcade operators as well as the regional distributors that were now essential to their trade. The more they traveled, however, the more it became clear just how pervasive the problem of copycat competition and undercutting had become.

As early as 1925, J. Frank Meyer filed an injunction against a Philadelphia business, the United Post Card Supply Company, which had been blatantly reproducing ESCO picture cards and offering them to operators at cheaper prices. Meyer won that case, but it was merely the beginning of a long line of similar battles that would only get increasingly under Meyer’s skin during the more challenging economic period of the 1930s.

As early as 1925, J. Frank Meyer filed an injunction against a Philadelphia business, the United Post Card Supply Company, which had been blatantly reproducing ESCO picture cards and offering them to operators at cheaper prices. Meyer won that case, but it was merely the beginning of a long line of similar battles that would only get increasingly under Meyer’s skin during the more challenging economic period of the 1930s.

“My company, like other legitimate manufacturers in our field, has been forced to spend thousands of dollars annually to protect our patent rights against the patent racketeers and pirates that have come to infest our industry in the past few years,” Meyer told Billboard in 1933. “ . . . The federal courts are so slow in bringing patent thieves to justice that sometimes the only method open to a patentee and the only legal thing he can do is to notify operators, jobbers, and locations that the machine they have is an infringement and to warn them that they are liable for damages under the law for possession or operation of the machine. This is not to be construed as a threat, but it is a legitimate legal procedure.”

While card venders were still a big part of the business in this period, ESCO’s machines now also included amusing tests of strength (such as the “Braying Jackass Lifter,” “Tiger Tail Puller,” and “Knockout Punch Tester”), target shooting games (“Automatic Pistol Range”), and some baseball themed trade stimulators (“Playball” and “Batter-Up”), which involved hitting a deposited penny with a miniature bat—get a hit and you could earn your penny back, or a gumball. The promotional emphasis was always on the “skill” element of the game, as the feds were already threatening to shut down any devices they deemed to have an illegal gambling element. But for the operators of the machines, the benefits basically worked the same as a casino—profits relied on the players losing a bit more often than they won.

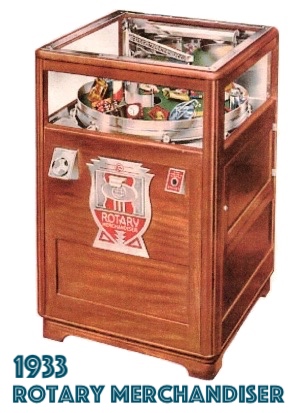

This certainly applied to another brand new sensation in the arcade world of the early ‘30s: the “digger” machine. Also known as a crane or claw machine, this familiar type of “merchandiser” arcade game challenges the player to use a miniature moving crane to scoop up prizes inside the console. ESCO didn’t invent the digger (that credit often goes to the Erie Manufacturing Company and its “Erie Digger,” circa 1924), but it quickly made improvements on the idea and patented key design features that would be used in its “Iron Claw,” “Goldmine,” “Novelty Merchantman,” and “Rotary Merchandiser” machines.

Because of the public’s obsession with the claw game (which continues to this day), J. Frank Meyer was particularly poised to conquer the digger marketplace, and to do so, he aimed his lawsuit laser at several more competitors. By 1937, ESCO was no longer being shy or downplaying its threat of legal action. The company bought a large advertisement in Billboard that year with the headline, “A Warning to End All Warnings,” in which it listed its claw machine patents and raised its fists to anyone who dared do business with other piggybacking suppliers.

Because of the public’s obsession with the claw game (which continues to this day), J. Frank Meyer was particularly poised to conquer the digger marketplace, and to do so, he aimed his lawsuit laser at several more competitors. By 1937, ESCO was no longer being shy or downplaying its threat of legal action. The company bought a large advertisement in Billboard that year with the headline, “A Warning to End All Warnings,” in which it listed its claw machine patents and raised its fists to anyone who dared do business with other piggybacking suppliers.

“The Exhibit Supply Company, the ORIGINAL successful builder of Novelty Merchandise equipment, owns and controls ALL the above patents exclusively and will not hesitate to prosecute vigorously all infringers. . . . Don’t be misled. Don’t misplace your confidence. Don’t buy a cheap copy.”

For a while, Exhibit Supply and the Mutoscope Company produced the only legally patented diggers in America. But technology changed too quickly to hold off new challengers, especially in the coin-op world, where shadiness was always baked into the business, and operators were always happy to shed some ethics to make a buck.

III. Switching Things Up

Thanks in no small part to Meyer’s persistent defense of his company’s intellectual property, ESCO maintained and even increased its production during the Great Depression. The company had a prominent display at the 1933 “Century of Progress” World’s Fair in Chicago, and a feature article in Automatic Age the following year reported that “things are humming at the Exhibit Supply Company factory these days. Almost every visit we make discloses new machinery and equipment being installed. The fact is, during the past ten months, the factory has been rearranged and extended to accommodate new manufacturing equipment. At the Exhibit plant everything is done under one roof, from the making of tools and dies to the printing of beautiful colored circulars, advertising the machine.”

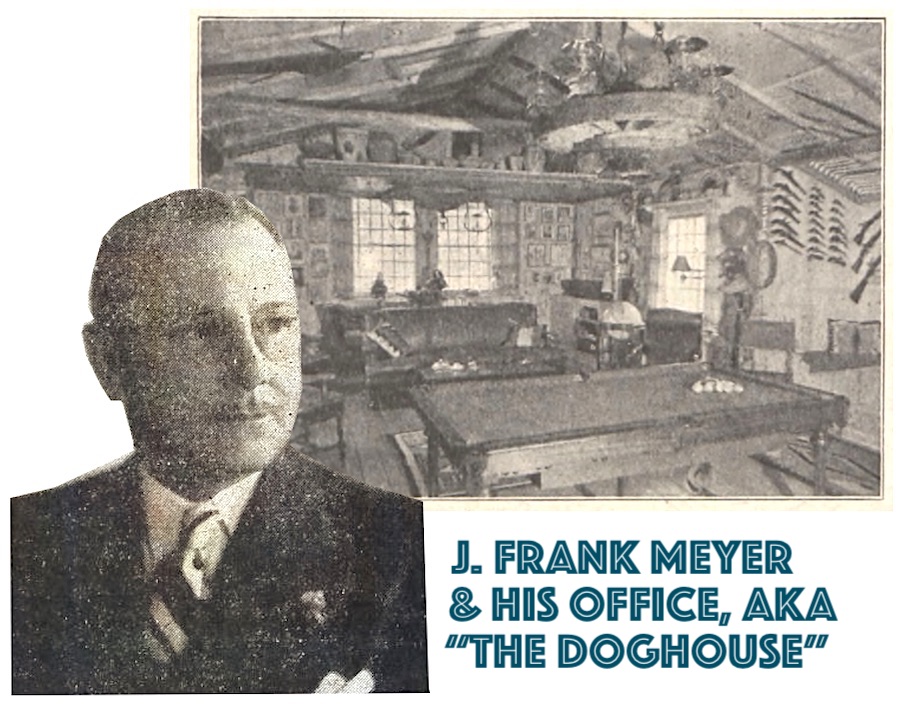

The same article notes the completion of J. Frank Meyer’s newly renovated office, which was famously known as the Den Room or The Doghouse. “This new departure in the way of private offices boasts natural wood panels all around, trophies of different kinds of game and fish upon the walls, Indian rugs upon the floor, large fireplace, and everything to make you think that you are in a hunting lodge up in the north woods.”

The same article notes the completion of J. Frank Meyer’s newly renovated office, which was famously known as the Den Room or The Doghouse. “This new departure in the way of private offices boasts natural wood panels all around, trophies of different kinds of game and fish upon the walls, Indian rugs upon the floor, large fireplace, and everything to make you think that you are in a hunting lodge up in the north woods.”

A prominently placed framed slogan on the office wall read: “The priceless ingredient of every product is the honor and integrity of its maker.”

In 1935, after more than three decades as a sole shareholder, Meyer finally decided to incorporate the Exhibit Supply Company, seemingly with an eye to its future. Close relations, including his brother Clare G. Meyer and son-in-law Stewart W. Knabe, were soon brought into the firm, and Perc Smith’s team was upgraded with the likes of VP Leo J. Kelly, sales manager John Chrest, plant manager Chet Gore, and former Bally engineers Lyndon Durant and Harry E. Williams. Meanwhile, J. Frank started spending more of his time either in California or traveling abroad.

“Just received a postcard from J. Frank Meyer of the Exhibit Supply Company,” Automatic Age editor John Goodbody wrote in 1934. “Frank is in England enjoying the sights, and his next stop is Germany. Incidentally, Frank is not afraid of Germany because his name is Meyer. It’s a German name and Hitler will not bother him (I hope).”

[Inside the Exhibit Supply Co. showroom, c.1934]

By the end of the decade, of course, light-hearted comedy about Nazi Germany was a bit harder to come by, and when the United States entered World War II in 1941, Meyer and his team had already begun preparing for the consequences.

Surely, in a time of metal rationing, there would be no exceptions made for the already frowned-upon coin-op industry—and indeed, all amusement machine production was halted indefinitely. For general morale, ESCO was allowed to keep printing new card sets for its existing vending machines, many of them designed for levity and distraction, with titles like “A Guide to Romance and Success” and “True Love Letter Post Office (which dispensed fake love letters from imaginary girlfriends). The “Blind Date” cards from our museum collection, published in 1941, would have been among the common wartime sets in wide circulation. Split into different series for the ladies and the gents, many of these cards wound up in soldiers’ pockets before they shipped back out to the front, providing a much-needed chuckle.

With some of its own workforce now serving in the military, and many more facing layoffs with machine production shut down, Exhibit Supply joined five other Chicago coin-op companies in a joint presentation before Congress in 1942, pleading for defense contracts and explaining the role their midsize factories could play in the war effort. The newly formed War Production Board eventually cottoned to the idea, and ESCO was re-formed overnight into a producer of radio and radar parts.

With some of its own workforce now serving in the military, and many more facing layoffs with machine production shut down, Exhibit Supply joined five other Chicago coin-op companies in a joint presentation before Congress in 1942, pleading for defense contracts and explaining the role their midsize factories could play in the war effort. The newly formed War Production Board eventually cottoned to the idea, and ESCO was re-formed overnight into a producer of radio and radar parts.

The transition was significant in terms of personnel, too—engineers Durant and Williams departed in 1942 to form their own company, and with so many men in service, the company began hiring many more women to work at the Lake Street factory. The goal was always to switch right back to amusements once the war was over, but the necessity of defense work had also led to significant, unexpected innovations—most notably a new type of switch, known as the “Electro-Snap,” which was used on bomb bay doors. J. Frank Meyer himself took an active role in refining the switches ESCO started producing during the later years of the war, and they met with such strong approval from the government that it soon became clear that the Electro-Snap would need to remain part of the business plan even after peace was declared in 1945.

Before the end of that year, the company had already announced another major expansion of the Lake Street factory in anticipation of both continuing military supply work and a full return to the amusements business. Part of the plan included retaining more female workers, who’d shown their worth over the past few years.

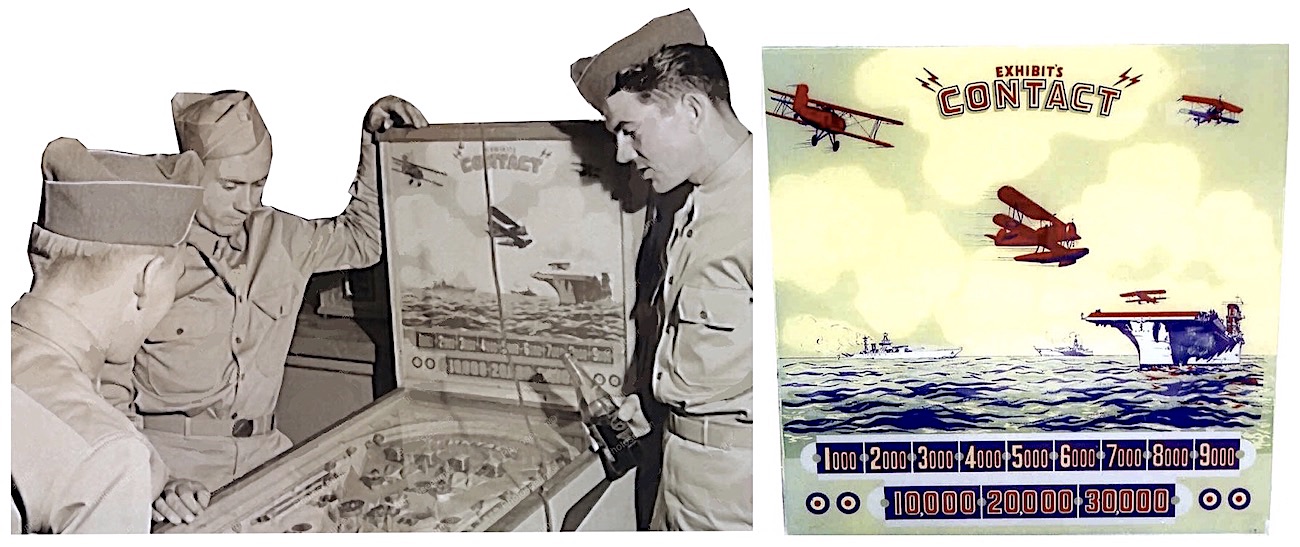

[Soldiers taking a break to play Exhibit’s “Contact” pinball game at an arcade in the early 1940s. Exhibit was starting to develop more pinball machines before the war shut down production in 1942]

“This does not mean we are not going to hire as many men,” sales manager John Chrest told Billboard, “but it does mean that our production is going to be much greater than before the war, and with expansion of our line of coin machines we’ll need all the skilled help we can get.”

Chrest added that, “when the job of renovation is complete we will have one of the most modern coin machine manufacturing plants in the Midwest.”

Exhibit Supply seemed perfectly positioned for continued success in post-war America, particularly with the unmatched experience of Chrest, Perc Smith, and J. Frank Meyer in the boardroom. Unfortunately, all three men would be gone in the span of a few months, sending the business permanently spinning off its axis.

IV. House of Cards

The year 1948 was supposed to find the Exhibit Supply Company back to its pre-war form as a leader in amusement machine manufacturing. Instead, it was a year of tragedies and setbacks. Early that summer, the company’s respected sales managers, Perc Smith and John Chrest, both died of prolonged illnesses just four days apart. J. Frank Meyer, who was recovering from a heart ailment himself in Pasadena, California, was kept in the dark about his friends’ deaths for days, just to spare him the double-dose of grief. Meyer eventually got the bad news, and in the weeks ahead, his own condition worsened. He died in November, aged 67.

When the news broke, Billboard reported on a “flood of stories by veteran arcade men showing how Meyer had helped them get started in the field.

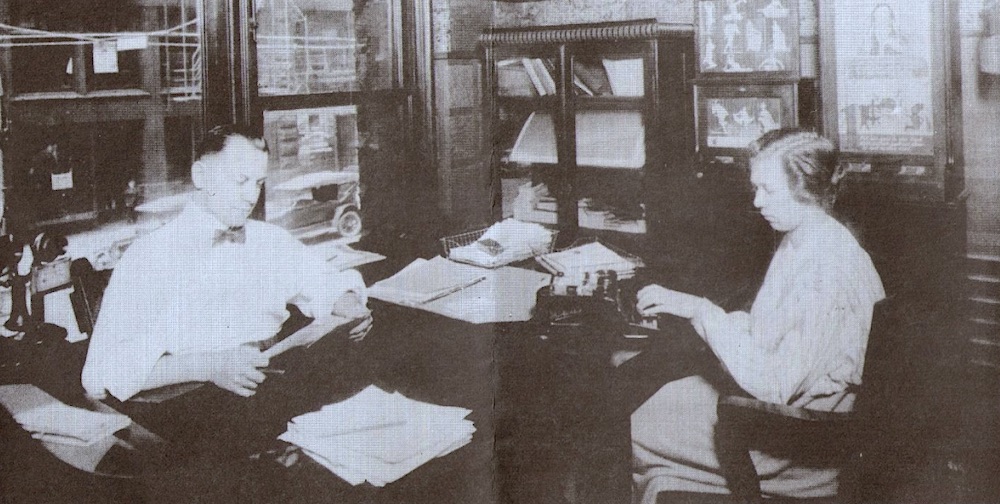

[J. Frank Meyer and his secretary in his original office on Dearborn Street, circa 1914. After his death, the trade publication Cash Box hailed him as the “Daddy of the Arcade Business”]

“Many of them, now successful, admitted that Meyer would let them have merchandise with little or no down payment with the simple statement: ‘Pay when you can.’ He was a shrewd judge of character and business acumen and, apparently, could size up people immediately. . . . Although he asked a lot of his staff, no man working for him ever worked as hard as he did.”

Meyer’s shoes would have been hard enough to fill as ESCO’s founder and figurehead, but with Chrest and Smith’s passings added into the mix, the company entered the 1950s in search of an identity.

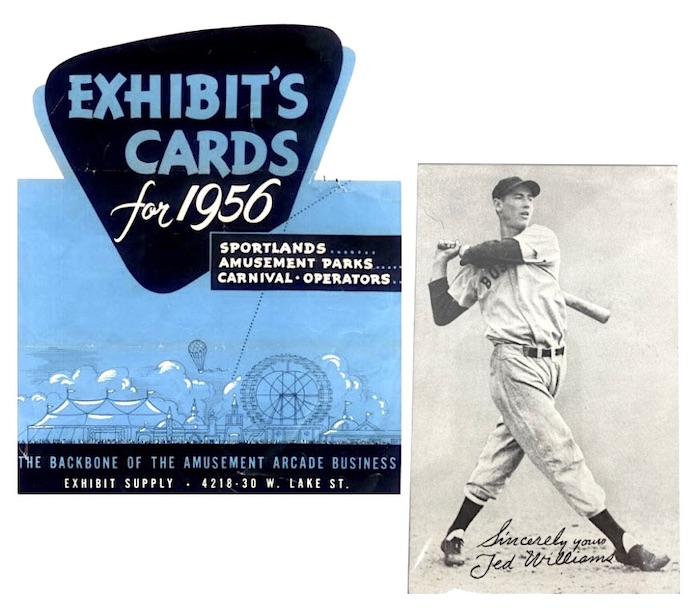

The Chicago plant was still producing new arcade machines on a regular basis—including an assortment of shooters, diggers, and a new line of kiddies rides—and its trading cards had come to include a larger assortment of baseball and football stars. On all fronts, though, competition was getting fiercer.

The Chicago plant was still producing new arcade machines on a regular basis—including an assortment of shooters, diggers, and a new line of kiddies rides—and its trading cards had come to include a larger assortment of baseball and football stars. On all fronts, though, competition was getting fiercer.

Even in the sports card market, ESCO didn’t have the wherewithal / budget to produce brand new cards of players every year—instead, the same images of stars like Ted Williams and Hank Aaron would be printed throughout the 1950s, with only mild tweaks along the way, and usually without extra info or statistics on the back of the card. As companies like Topps established the idea of annual card sets and exclusive deals with athletes, Exhibit was gradually elbowed out of the market.

Exhibit also failed to make the successful transition into the booming jukebox industry, which had proven a saving grace for Chicago coin-op businesses like Seeburg and Rock-Ola. The problem wasn’t necessarily a lack of good leadership, but a muddle of too many voices.

[These three ads, all from 1956, feature new table-top skill games that Exhibit was banking on to help it regain a foothold in the industry. A year earlier, ESCO president Sam Lewis predicted that games like Spanish Pool could represent “the possible birth of an entire new trend in coin-operated games,” but it wasn’t to be.]

After Meyer’s death, his brother Clare Meyer remained an active part of the sales team, but didn’t seem interested in a higher position. Executives Harold T. Ames, Ford Sebastian, and Joseph A. Batten were largely in charge, with Charles Pieri as sales manager. Pieri quit two years later, and Frank J. Mecuri was installed as the new head of sales. Art Weinand was plucked from Rock-Ola in 1953 to become a vice president, but also bailed after two years. Sam Lewis was then hired over from the Chicago Coin Machine Company to become ESCO’s new president in 1955—but both he and Mecuri would resign by 1957. With those final departures, all production of amusement machines at the Exhibit Supply Company was abruptly brought to a halt.

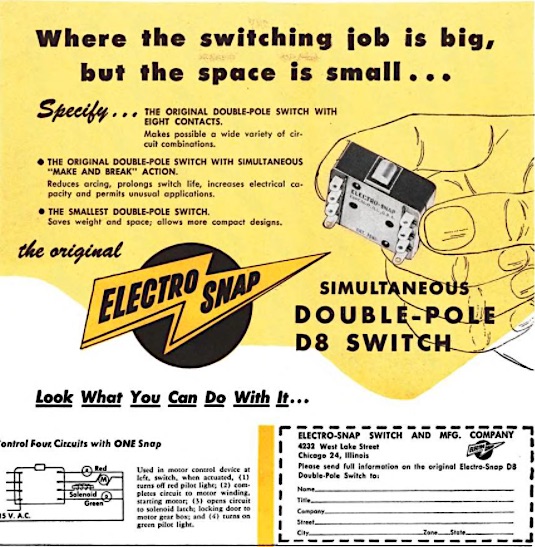

So what happened? Well, besides slumping sales with its new games, the focus of the company had also been gradually turning more and more to its more profitable military supply production. In fact, those switches that ESCO had developed during the war had evolved into a separate division of the business and ultimately a new, growing company unto itself, the Electro-Snap and Switch MFG Co.

Presided over by Harold T. Ames, Electro-Snap was based in the same Lake Street building as ESCO and shared many of the same team members. One of them, a young engineer named John Otto Roeser, collected a lot of the early switch patents for the firm in the ’40s and ’50s, and would go on to launch his own successful industrial switch business, Otto Engineering Inc., in the 1960s. Much later in his life, the very same Jack Roeser would become a leader of the Tea Party movement in Illinois in the 2000s, leading campaigns against gay rights and trying to torpedo Barack Obama’s early senate runs. He died in 2014.

Presided over by Harold T. Ames, Electro-Snap was based in the same Lake Street building as ESCO and shared many of the same team members. One of them, a young engineer named John Otto Roeser, collected a lot of the early switch patents for the firm in the ’40s and ’50s, and would go on to launch his own successful industrial switch business, Otto Engineering Inc., in the 1960s. Much later in his life, the very same Jack Roeser would become a leader of the Tea Party movement in Illinois in the 2000s, leading campaigns against gay rights and trying to torpedo Barack Obama’s early senate runs. He died in 2014.

Behind the designs of Roeser and others, Electro-Snap & Switch did well enough in the 1950s that it soon evolved from a division of Exhibit Supply into its actual parent company. In terms of sales, the old amusements market had become something of a frustrating afterthought compared to the big money to be had in the aircraft and weapons industries.

And so, in 1957, the last person left standing in the old ESCO wing of the Lake Street plant was longtime arcade man Chet Gore, who took over as company president and eventually sole owner of a newly independent Exhibit Supply Company (detached from Electro-Snap). In 1960, Gore moved the ESCO plant five blocks down the street to a smaller building at 4719 West Lake, with the goal of relaunching its arcade machine works. This goal was only partially achieved. While ESCO got back into the card vender business and continued to produce various sets of models, celebrities, and athletes, the staff was down to 15 people in 1965 compared to the nearly 300 workers a decade earlier.

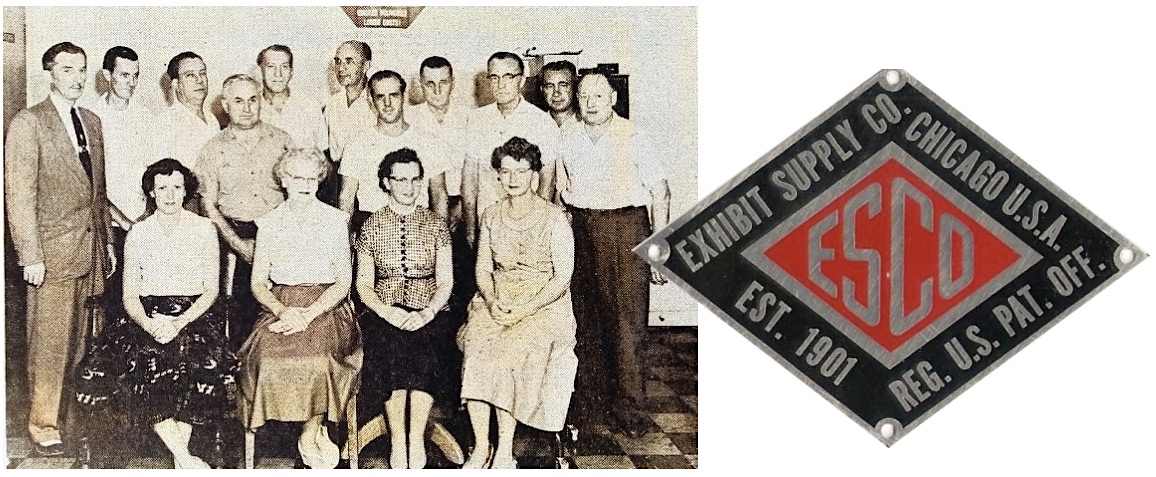

[15 of Exhibit Supply’s longest serving employees posed for the photo above in 1955. They are: Frank Mencuri (top row, far left), Patrick Moran, Chester “Chet” Gore (top row, third from left), Hugo Stube, Max Hofstetter, Lee Moss, Tony Covelli, Louis Johnson, Shorty Houser, Frank Cosenzo, Louis Russ, Margaret Romano, Margaret O’Brien, Marian Souhrada, and Florence Mullaney. Only a few of these people were still on board when Chet Gore moved the company to the building below in 1960]

[4719 W. Lake Street as it looks today. This was ESCO’s plant from 1960 until its sale in 1979]

In 1979, Gore and two minority shareholders sold the Exhibit Supply Company to a 33 year-old sports card dealer named Paul Marchant. In a 2017 interview with Sports Collectors Digest, Marchant recalled that Gore was still actively printing many of the same fortune-telling and horoscope cards ESCO had been supplying since the 1920s, sourced from the same plates.

According to Sports Collectors Digest, “Marchant agreed to buy everything” at the ESCO plant, “including arcade machines, plant equipment, presses, cutters, parts, photos and records.” Some of the arcade machines were converted to accept quarters rather than nickels, and were then sold off, along with most of the miscellaneous pieces and parts from the ESCO archives. What Marchant kept were the more than 7,000 surviving photos that had been used to create the company’s giant library of arcade cards. He used these to print a few more runs of Exhibit Supply cards before officially dissolving the company’s corporate entity in 1985.

Sources:

“Meyer vs. Herwitz” – District Court, E.D. Pennsylvania, May 15, 1925 – The Federal Reporter

“Exhibit Supply – Amusement Machines Exclusively” – Automatic Age, Sept 1926

Exhibit Supply Co. Catalogue, 1929

“Holds Patents, Says Pioneer” – Billboard, May 20, 1933

“Law Holds User Liable in Patent Infringements” – Coin Machine Journal, May-June 1933

“Feverish Production Underway at Exhibit Plant” – Automatic Age, May 1934

“Exhibit Again Largest Exhibitor with Seven Booths” – Automatic Age, Jan 1937

“6 Chicago Firms Plead for Share of War Orders” – Chicago Tribune, Feb 24, 1942

“Chicago Firm Plans Extensive Plant Remodeling Program” – Billboard, Dec 1, 1945

Exhibit Supply Co. Catalogue, 1948

“Perc Smith Dies, Ending Career of Pioneer Coin Man” – Billboard, June 12, 1948

“John Chrest Dies; Second Top Exhibit Exec Loss in 4 Days” – Billboard, June 19, 1948

“J. Frank Meyer, Founder of Exhibit Supply, Passes” – Billboard, Nov 20, 1948

“Exhibit Wins NAAPPB Award 2nd Consecutive Year” – Cash Box, Dec 9, 1950

“Mencuri Covers the Country” – Cash Box, Dec 23, 1950

“Sam Lewis Elected President of Exhibit Supply Co.” – Cash Box, Sept 17, 1955

“Mencuri Resigns from Exhibit” – Cash Box, Feb 23, 1957

“Williams Signs Lewis to Exec Sales Force” – Billboard, Nov 25, 1957

“Exhibit Supply Resuming Arcade Machine Output” – Billboard, Nov 30, 1959

“Exhibit Supply Company” – Arcade-Museum.com

“A Look Back Helps Understand Exhibit Supply Cards” – Sports Collectors Digest, Sept 25, 2017

They Create Worlds: The Story of the People and Companies that Shaped the Video Game Industry, by Alexander Smith, 2019

I have old post cards never been used car you tell me about them and value please

Larry Semon , Richard Holt, Buster Keaton ( the general ) , Baby “Peggy “ Montgomery and more .

And small 2inch cards Golden Grain the BURLEY blend Granulated Tabasco

I have an antique automaton, coin op machine here called “Watch Rufus Play 5 cents”. It is tabletop. I’m trying to tie it to a specific location. I believe it is an (ESCO) Exhibit Supply Co., Chicago mfg. Any pictures or information about the machine and its origins would be greatly appreciated!

Hello; I have a rotary Claw machine made by ESCO that needs restoration. I’m in Boonville, MO and I need help finding someone who works on these machines. I would also like to find any owners / repair manuals. The machine appears complete but 1 motor has been disconnected and might need to be rebuilt or replaced.. Any help would be greatly appreciated. My number is 1 (626) 999-7746 Thank you. Regards, JB

Hi, I grew up with many classic slot machine, old school machines that my father bought and restored. He’s passed and I have a fortune teller machine that takes pennies and now when you squeeze the handles it does not work. I am wondering what I can do to unjam the machine. I have a key that fits the front lock but will not turn all the way. I can take a pic if it will help. Thank you

This is Christina Mosteller again on the 1928 Ex. Sup. Co. Chgo. Made USA card of a long hair blonde w/ wavy hair. Nude under a sheer pokie dot sheet covering herself with her right breast showing. It’s like she’s trying to cover up w/ her right hand holding it up to cover up. My email is skiewalker77@gmail.com my number is 704-936-6631. Please feel free to call me or email me. Give me a day or so to respond to your email. If you call I can speak to you directly. Thank you so much

By my grandmother passing I found a 1928 EX. Sup. Co., Chgo. Made in USA card of a blonde naked woman w a shear polka dot over her body sitting on a stool. It shows her breast and nipples. I’m not sure if she is famous or not. She does look familiar. Pls feel free to reach out to me

I have an Exhibits 2 cent “license to do anything” card machine in working condition.

It is a vacuumatic machine.

Can anyone help me with info?

I want to sell it.

Can you send me pictures please

I have a set of baseball and assorted categories of cards including gorgeous George, nature boy rogers,football some actors wrestling and boxing cards also nasa is there anyone interested in the whole collection they are in great shape phone # 445-226-8853 Jerry

Esp. interested in Billboard biography back exhibit/arcade cards. Although the ESCO information refers to Billboard, no specific connection is established. Did ESCO publish these? Was there ever a list? If there was an ESCO-Billboard connection, did Billboard ever mention and/or promote these cards in its publication? Specific information would be appreciated.

Robert my name is Christina mosteller and I have found a photo from 1928. She looks like someone famous from the older movies. I want to sell it. She’s nude with a sheer polka dot sheet. You can see her breast. I know that was a big deal back then. Can u contact me.

Another fascinating story with common themes shared with others, like effects and big changes due to WW II for example. Well done. Thank you.

I found a medal that says Exhibit Supply Co, Chicago USA w an incised 20 on the front and Marksman Skill Medal on the back. Serial no is blank. Does anyone have info on it? (It won’t let me post a pic)