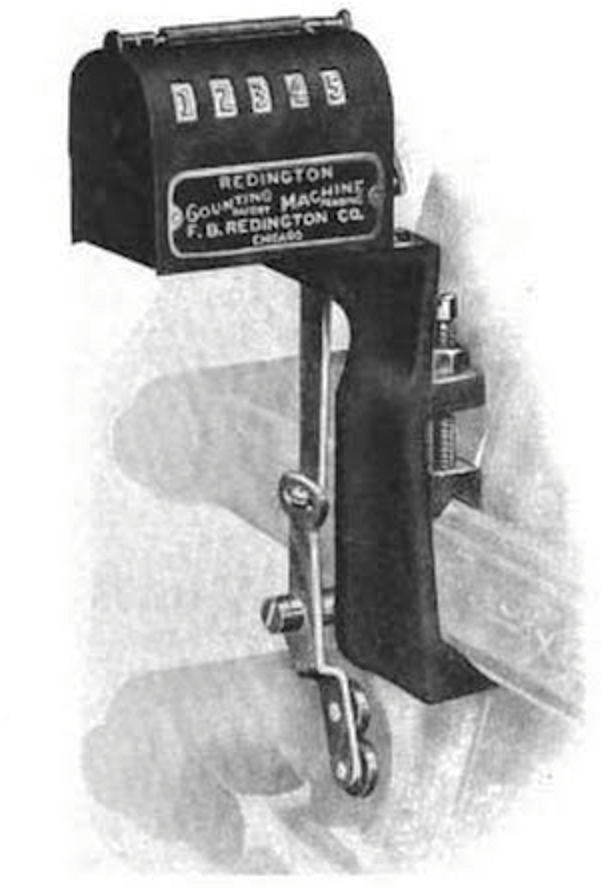

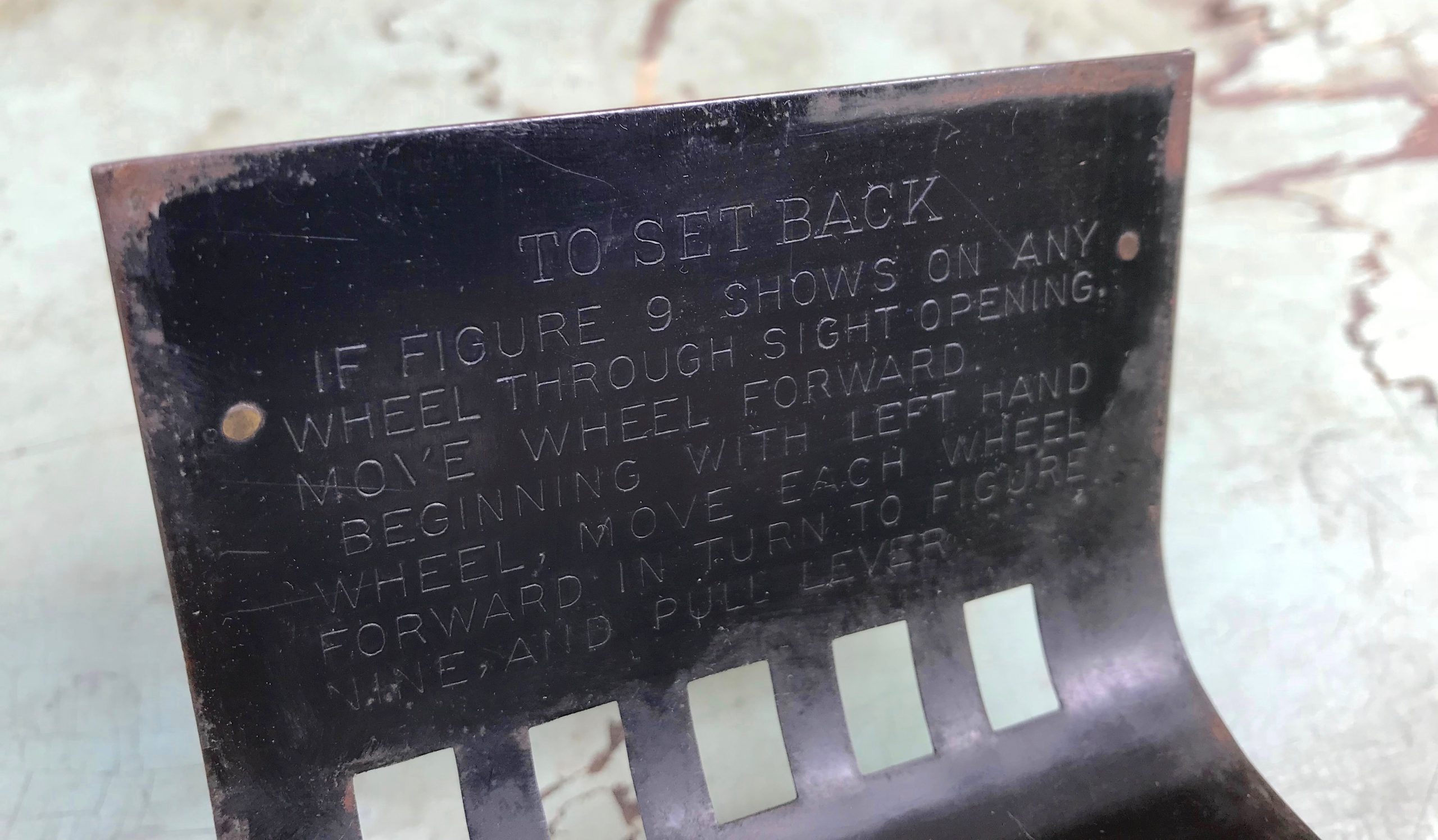

Museum Artifact: Redington Counting Machine, c. 1920s

Made By: F.B. Redington Co., 112 S. Sangamon St., Chicago, IL [West Loop]

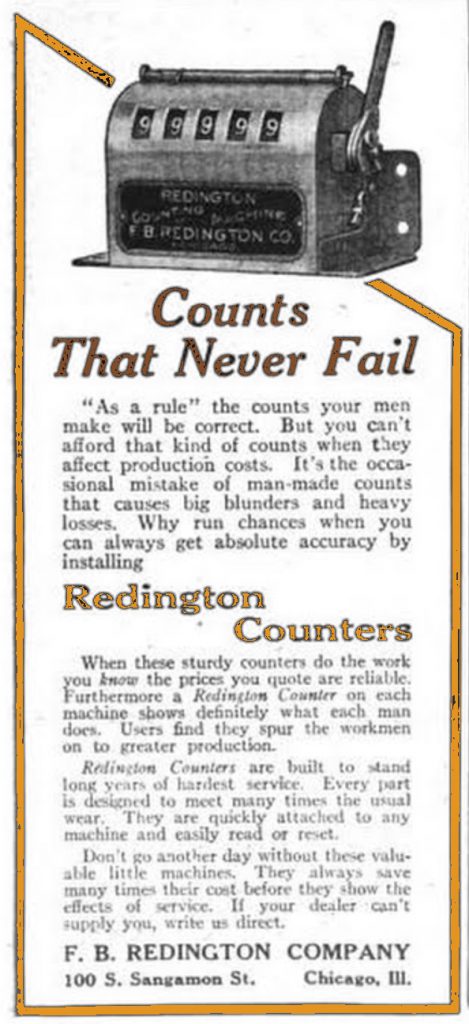

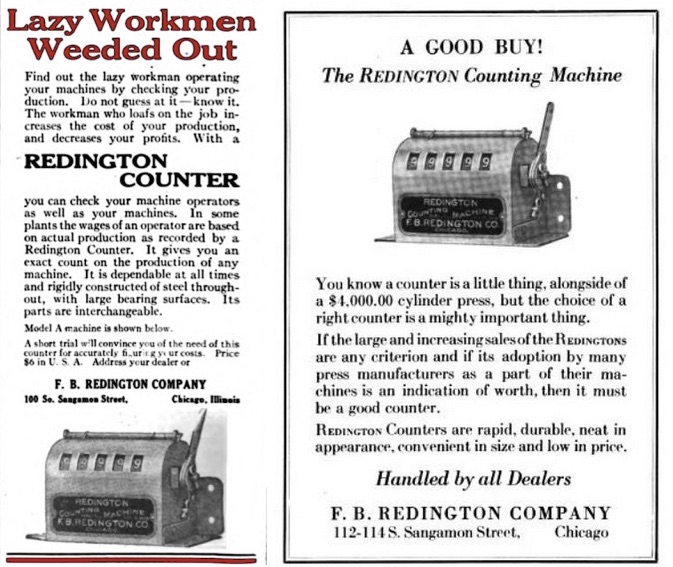

“Lazy Workmen Weeded Out,” read the tagline of a 1919 advertisement for the Redington Counting Machine—a device that’s still used in factories (in a digital format) nearly 100 years later.

“Find out the lazy workman operating your machines by checking your production. Do not guess at it—know it. The workman who loafs on the job increases the cost of your production, and decreases your profits. With a REDINGTON COUNTER, you can check your machine operators as well as your machines. In some plants the wages of an operator are based on actual production as recorded by a Redington Counter. It gives you an exact count on the production of any machine. It is dependable at all times and rigidly constructed of steel throughout, with large bearing surfaces. Its parts are interchangeable.

“Find out the lazy workman operating your machines by checking your production. Do not guess at it—know it. The workman who loafs on the job increases the cost of your production, and decreases your profits. With a REDINGTON COUNTER, you can check your machine operators as well as your machines. In some plants the wages of an operator are based on actual production as recorded by a Redington Counter. It gives you an exact count on the production of any machine. It is dependable at all times and rigidly constructed of steel throughout, with large bearing surfaces. Its parts are interchangeable.

“A short trial will convince you of the need of this counter for accurately figuring your costs. Price $6 in USA. Address your dealer or F. B. Redington Company, 100 So. Sangamon Street, Chicago, Illinois.”

While fear of the dreaded “lazy workman” was one effective way to sell this product to a frazzled factory foreman, the Redington Counter was really devised more as a way to make better use of a good worker’s time. Rather than scribbling away production totals on a note pad or guesstimating a day’s output with the eye test, the little counter machine would dutifully perform the mundane task of literally ticking off a point for every “thing” that came down the line—freeing up the human laborers for more pressing matters.

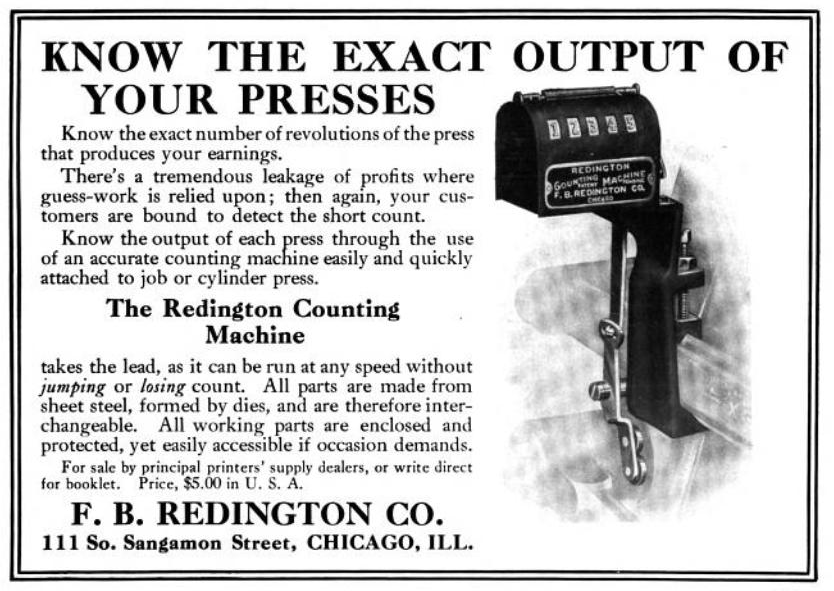

Speaking of “pressing,” the device was used most famously as a printing press accessory, enabling the automatic, accurate tallying of paper sheets. All you had to do was hook up the counter to an attachment on the press, and the little lever would click off another number with each revolution of the cylinder.

“There’s a tremendous leakage of profits where guesswork is relied upon,” warned another Redington ad from 1911. “Know the exact output of your presses!”

The Redington Counter, in its evolving forms, has remained an industrial staple long after most of its turn-of-the-century contemporaries went obsolete. Today, the Florida company Trumeter is in charge of its distribution. The counter’s namesake, however—the industrious industrialist Frank B. Redington—has largely been forgotten, despite his once ubiquitous place in Chicago’s “Who’s Who” of machining men.

[This second Redington counter from our collection was loaned to the Chicago History Museum for its exhibit: “Modern by Design: Chicago Streamlines America” in 2018 . . . As of 2024, we’re still waiting to get it back from them.]

The Baby of the Family

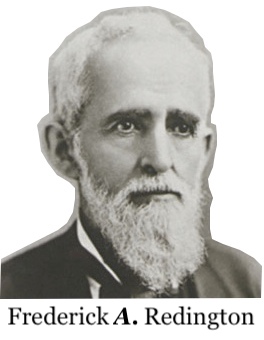

Frank Brown Redington was born in Chicago in 1866, the same year his family relocated from Massachusetts in the hopes of finding new fortunes in the great western metropolis. Frank’s dad, Frederick A. Redington* [pictured], was the co-founder and secretary of the Sanford Manufacturing Company, a successful maker of ink and writing instruments that would one day produce the celebrated Sharpie marker. It might be a stretch to say Frank was born with a silver spoon, but there were certainly some unique opportunities presented to him.

*Many sources cite the founder of Sanford Ink as Frederick W. Redington, but actual census records make it pretty clear that it was actually Frederick A. Redington (A for Augustus) who was living in Chicago in 1870, serving as secretary of the Sanford MFG Co. I’m open to debate on this one from any remaining members of the Redington clan or reps of Sanford L.P.

*Many sources cite the founder of Sanford Ink as Frederick W. Redington, but actual census records make it pretty clear that it was actually Frederick A. Redington (A for Augustus) who was living in Chicago in 1870, serving as secretary of the Sanford MFG Co. I’m open to debate on this one from any remaining members of the Redington clan or reps of Sanford L.P.

Frank’s very birth was an unlikely event—his mother Dora was 46 at the time, making Frank the infant kid sibling of an 18 year-old sister, Florence, and a 16 year-old brother, William. When Frank was still in diapers, William Redington was already working as a clerk with his dad’s company, on his path to eventually becoming the president of Sanford Ink. Unavoidably, Frank was always playing catchup, too far back even for hand-me-downs. But over time, this dynamic made him all the more motivated to create something important on his own.

[pictured below: Frank B. Redington, at an older age]

In his youth, he divided his time and energy into everything from operatic singing to mechanical engineering, always pleased to take on a challenge and solve a problem. For a while, he served as an apprentice of sorts to his big brother William, learning the ropes of the ink maker’s trade. But Frank was way too much of a Type A personality to remain anyone’s second fiddle for long.

In his youth, he divided his time and energy into everything from operatic singing to mechanical engineering, always pleased to take on a challenge and solve a problem. For a while, he served as an apprentice of sorts to his big brother William, learning the ropes of the ink maker’s trade. But Frank was way too much of a Type A personality to remain anyone’s second fiddle for long.

Like many kids of his time, he became a bicycle enthusiast in the 1880s, and developed a lot of his mechanical talents by tinkering with two-wheelers. In 1890, while a member of the Illinois Cycling Club, Frank combined two of his early passions, wowing his fellow bike nerds by singing Verdi’s “Infelice” during a cyclers’ talent show at the Madison Street Theatre. At 24, he was still the classic “baby of the family,” ever drawn to the spotlight.

[Singer Eduoard de Reszke taking a crack at “Infelice” in 1903, likely improving on Frank Redington’s 1890 rendition.]

Wrapper’s Delight

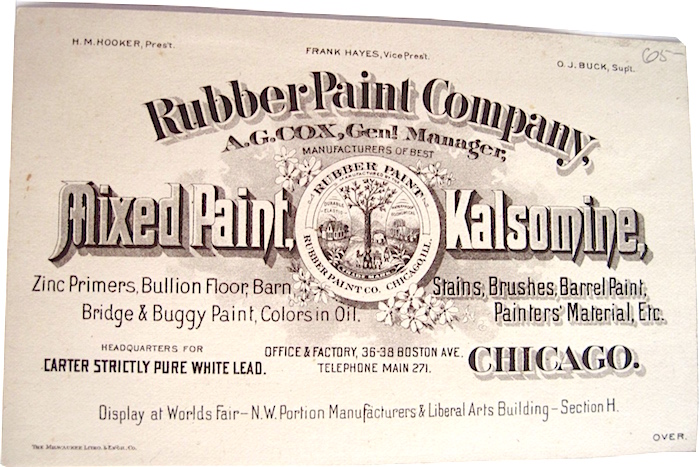

Shortly after his show-stealing performance in front of the Cycling Club, Redington left the family business and got a job with the Chicago operations of the Rubber Paint Company, where his brother-in-law Frank Hayes was the vice president (okay, so it was another family business).

[Business card for the Rubber Paint Co., with Frank Redington’s brother-in-law, Frank Hayes, noted as vice president, c. 1890s]

[Business card for the Rubber Paint Co., with Frank Redington’s brother-in-law, Frank Hayes, noted as vice president, c. 1890s]

Working in Chicago in 1893 was something of a mixed bag. On one hand you had the excitement of the Columbian Exposition and a constant push toward new innovation in the industries of the future—particularly electronics, automation, and automobiles. At the same time, the economy was in a tailspin, and no line of work felt secure. Fortunately, with his family connections at Sanford and Rubber Paint, Frank Redington had the advantage of being able to take a few more risks than the average man.

At the age of 27, for example, he joined with Rubber Paint Company co-worker William Brewer and some other investors to incorporate the Krehbiel Palace Car Company—a would-be challenger to the dominant Pullman line of passenger train cars. Redington threw himself into the project, personally presenting the fancy new railway car in the Transportation Exhibits Building at the World’s Fair. The business never gained any significant traction, though.

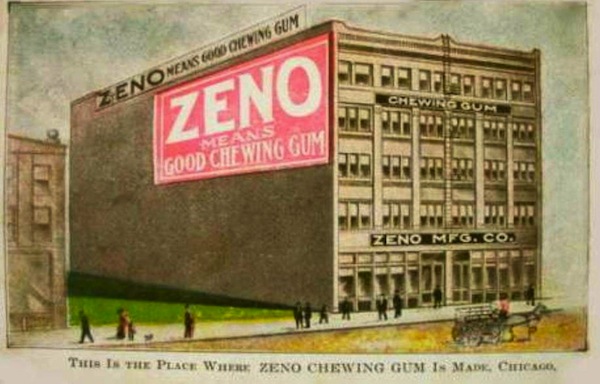

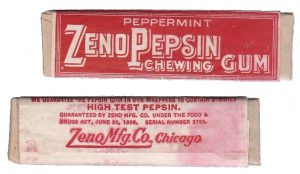

Likely sensing that young Frank needed a new distraction, Frank Hayes had him installed as the superintendent of a new Rubber Paint Company subsidiary called the Zeno Manufacturing Company—a producer of chewing gum, and the official provider to a young salesman named William Wrigley.

Likely sensing that young Frank needed a new distraction, Frank Hayes had him installed as the superintendent of a new Rubber Paint Company subsidiary called the Zeno Manufacturing Company—a producer of chewing gum, and the official provider to a young salesman named William Wrigley.

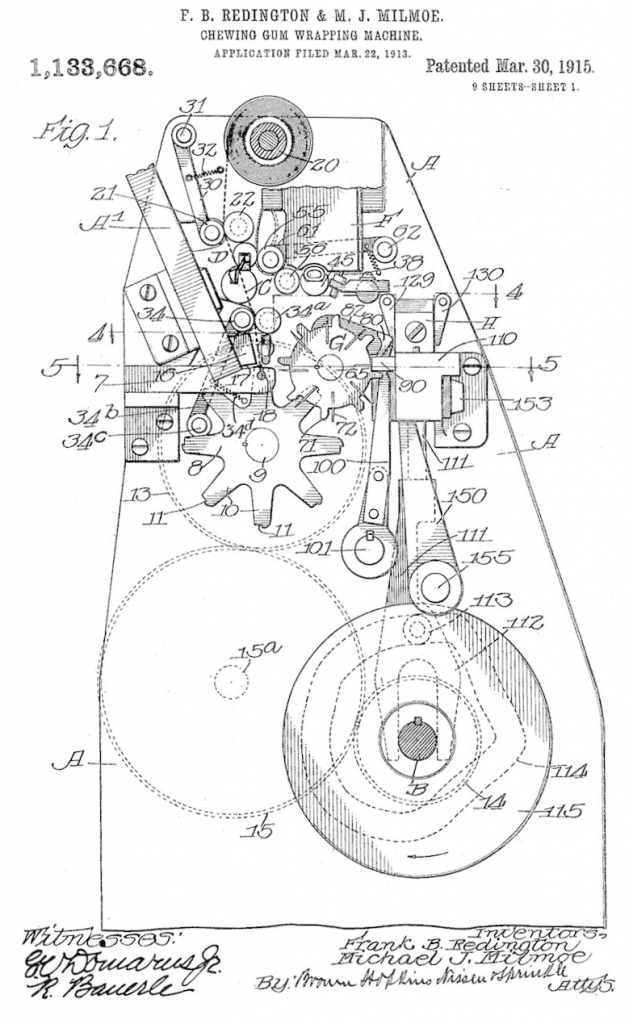

At the fledgling Zeno plant at 160 West Van Buren Street, Redington found a production system woefully unable to keep up with the exponentially growing demands of a suddenly gum-crazy country. The factory, staffed almost entirely by young, underpaid women, was still requiring those workers to individually hand-wrap and pack each and every stick of Zeno gum that came down the line. Along with being ludicrously inefficient, it was also borderline cruel and unusual. According to a 1936 article in Modern Packaging:

“F. B. Redington, superintendent of the Zeno Chewing Gum Company, found that forcing girls to work at higher speeds resulted in having to send them home from work, their fingers and thumbs sore and bleeding from wrapping sticks of gum by hand. This observation, in 1897, led to his development of the gum wrapping machine, which eliminated the hand work.”

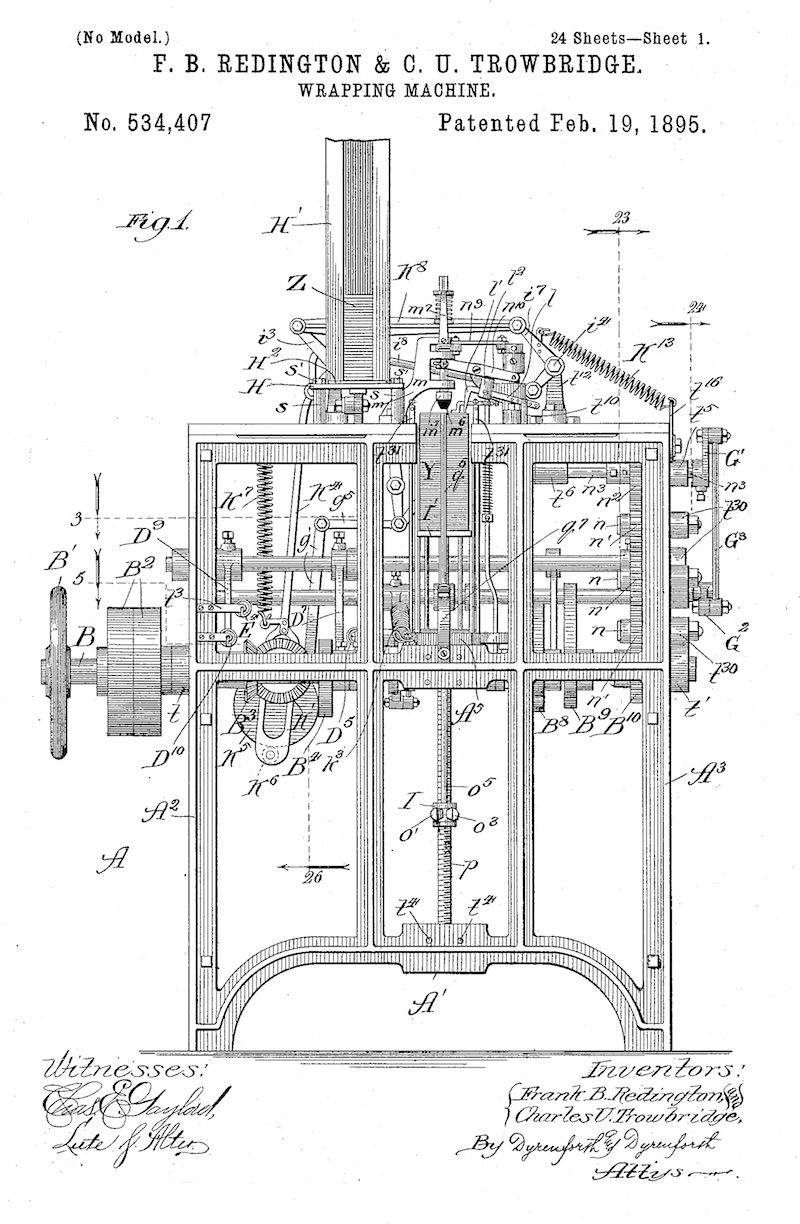

Judging by the U.S. patent records, Redington and a cohort, C. U. Trowbridge, actually developed their first wrapping machine two years earlier, in 1895. Looking more like something out of the Willy Wonka factory, the machine became the launch point for Frank Redington’s new career path as the baddest wrapper on the planet.

[One of Frank Redington’s first wrapping machines patents, 1895]

[One of Frank Redington’s first wrapping machines patents, 1895]

The gum wrapper was his first big hit, revolutionizing that budding industry and turning Zeno/Wrigley into a chewing gum juggernaut. So great was Redington’s role in that success, in fact, that some future journalists took some liberties in describing the exact nature of his contributions. Chicago Tribune financial editor Philip Hampson, for example, wrote a piece in 1953 that credited Redington not only with the wrapping machine, but with the invention of rubber-based chewing gum itself—not to mention introducing the stuff to William Wrigley.

“When a young man, [Redington] experimented with a paint having a rubber base. In so doing he found a chewing gum base. …Redington developed Zeno chewing gum, in its day widely known. He met William Wrigley, a soap salesman. Wrigley made a deal with Redington by which he have away Zeno gum with his soap. Meantime, Redington, who was mechanically inclined, developed a machine to package gum, while Wrigley went on to make something of a name for himself in the gum field.”

“When a young man, [Redington] experimented with a paint having a rubber base. In so doing he found a chewing gum base. …Redington developed Zeno chewing gum, in its day widely known. He met William Wrigley, a soap salesman. Wrigley made a deal with Redington by which he have away Zeno gum with his soap. Meantime, Redington, who was mechanically inclined, developed a machine to package gum, while Wrigley went on to make something of a name for himself in the gum field.”

That over-simplification seems to rob credit from the widely acknowledged inventor of Zeno gum, the aforementioned William N. Brewer, not to mention the efforts of higher ranking men like Frank Hayes and Zeno president A. G. Cox in likely arranging the Wrigley deal. We’ll probably never know exactly who was doing what within the shifting hierarchy, but one thing was clear—Frank Redington’s life long dream to be a top dog was finally about to be realized.

F. B. Redington Co.

Riding the heralded success of his wrapping machines, Redington—with another wee bit of help from bro-in-law Frank Hayes—launched his own Chicago operation, the F. B. Redington Company, in 1897. He was just 31 years old. “See, dad!” Frank shouted from a non-existent Illinois mountaintop. “I did it on my own! Who’s the baby now?!”

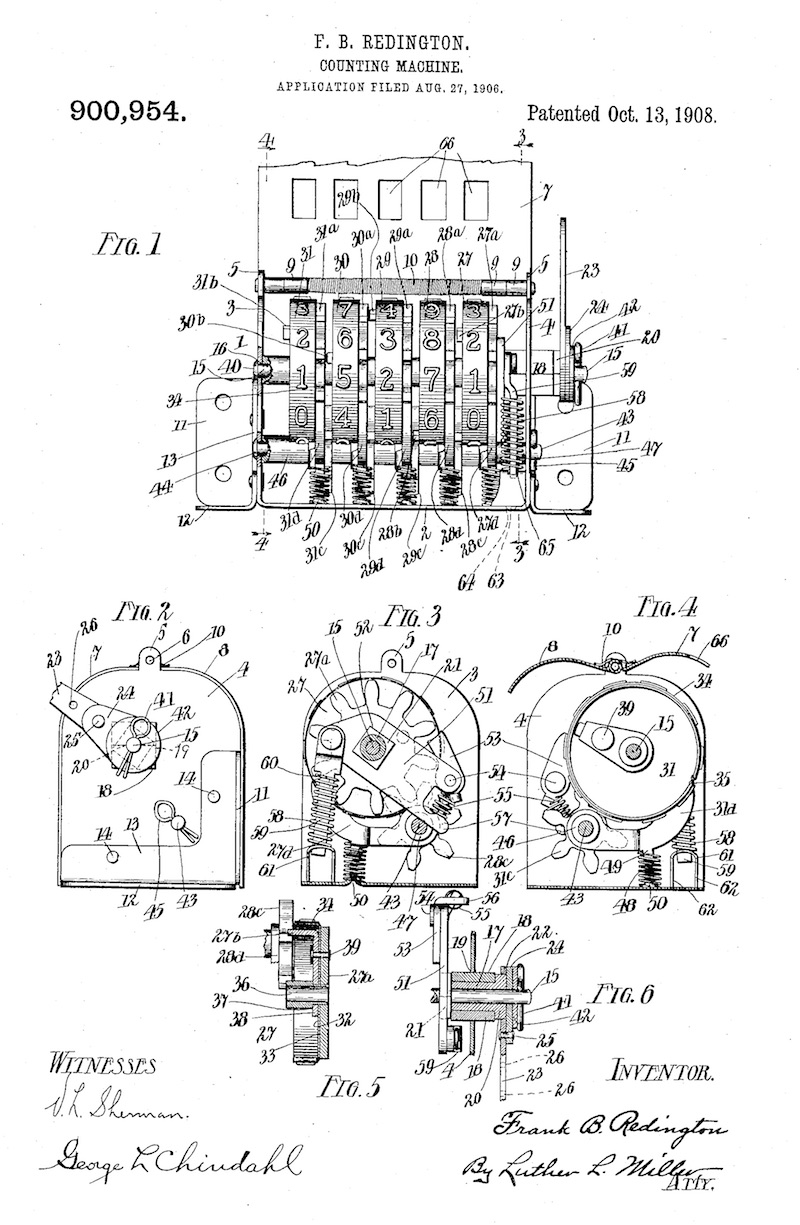

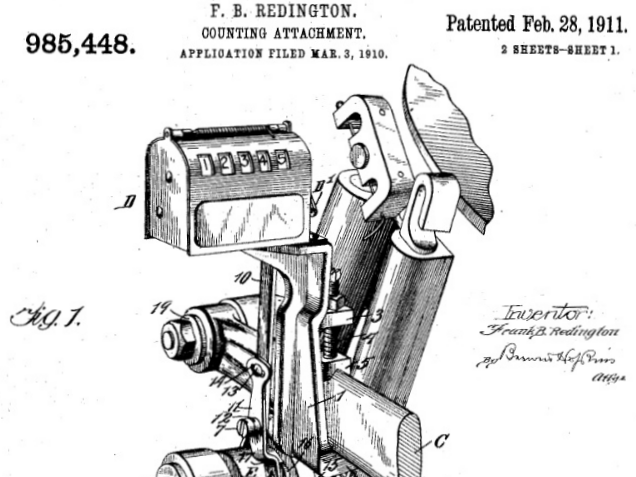

As the 20th century rolled in, Redington fine-tuned his gum wrapper while also rolling out some new inventions—most of them related to the field of factory efficiency and machining. His earliest patent for a counting machine seems to appear in 1906, and it became his second major product—soon emerging as the gold standard for printing press operators.

[Redington’s first counting machine patent, applied for in 1906, approved 1908]

[Redington’s first counting machine patent, applied for in 1906, approved 1908]

In the early years, a lot of the work at the Redington Co. also revolved around random automotive parts repair and manufacturing, a field just about everyone was dipping a toe into.

In the early years, a lot of the work at the Redington Co. also revolved around random automotive parts repair and manufacturing, a field just about everyone was dipping a toe into.

Within just a few years, the expanding focus of the business required a suitable space, and the first dedicated F. B. Redington Co. factory was established at 100-112 South Sangamon Street, on the corner of Monroe, with 25 full-time employees on staff. This building would serve as the company’s home base for the next half-century; the entirety of Frank Redington’s long career as president. Surprisingly enough, it’s still in operation as a (refurbished) office building to this day, more than 70 years after the Redington Company left it behind.

[Former Redington building at 112 S. Sangamon St. in the West Loop.]

[Former Redington building at 112 S. Sangamon St. in the West Loop.]

Package Machinery Co

In 1913, the F. B. Redington Company’s stature was elevated a bit further by the announcement of a major consolidation of a half dozen different package machine companies from across the country into a new entity—which would be known, appropriately enough, as the Package Machinery Company. Redington’s gum wrapping division was a part of this big union, and in November of the same year, Frank Redington himself was named president of the conglomerate—even though he lived in Chicago and the Package Machinery Co. headquarters was in Springfield, Massachusetts.

“Mr. Redington has been a director in the Package Machinery Co. since their incorporation,” read a press release in the December 1913 issue of Simmon’s Spice Mill, “and his promotion to the head of the company is a well deserved honor. He needs no introduction to the wrapping machine trade, as he is well known through the Redington chewing gum wrapping machines which have been the standard among gum manufacturers for many years. He assumes his new duties with a wide experience in the manufacture of automatic machinery and, especially, automatic wrapping machines. The Package Machinery Co. have met with remarkable success in the wrapping machine field, and the election of Mr. Redington insures continued advancement.”

“Mr. Redington has been a director in the Package Machinery Co. since their incorporation,” read a press release in the December 1913 issue of Simmon’s Spice Mill, “and his promotion to the head of the company is a well deserved honor. He needs no introduction to the wrapping machine trade, as he is well known through the Redington chewing gum wrapping machines which have been the standard among gum manufacturers for many years. He assumes his new duties with a wide experience in the manufacture of automatic machinery and, especially, automatic wrapping machines. The Package Machinery Co. have met with remarkable success in the wrapping machine field, and the election of Mr. Redington insures continued advancement.”

Like the Redington brand name, the Package Machinery Co. has bucked the odds and survived into the present day—still based in Springfield, Mass, and still a leader in packing machines. Who knew? (If you knew, don’t be cocky about it).

The Second Generation

Anyway, being part of the PMC conglomerate didn’t change too much at the F. B. Redington plant on Sangamon Street. The company continued to specialize in wrapping devices, counting devices, and other similar doo-dads. To stay competitive, though, an aging Frank Redington wisely recruited creative new minds into his company, looking for the same gleam in the eye that others had once seen in him.

Anyway, being part of the PMC conglomerate didn’t change too much at the F. B. Redington plant on Sangamon Street. The company continued to specialize in wrapping devices, counting devices, and other similar doo-dads. To stay competitive, though, an aging Frank Redington wisely recruited creative new minds into his company, looking for the same gleam in the eye that others had once seen in him.

At the end of World War I, in particular, Redington managed to hire two young kids who would become the left and right arm of the company for years to come. First was C. J. Malhiot, a 22 year-old ex-employee of Western Electric and a survivor of 1915’s deadly Eastland shipwreck disaster. Starting out as a promising young draftsman, Malhiot wound up as something of a “mini Redington,” patenting more than 50 improvements on packaging machines and cartoning, and working his way up to chief engineer and vice president of the company.

In Malhiot’s 1984 obituary, his son claimed that his dad’s “most important patent was the machine that allowed you to open cigarette and gum packs by pulling the little strip. I remember one of the customers was the American Tobacco Co. The machine was very complex and involved the total packaging process from tobacco or gum to the final package.”

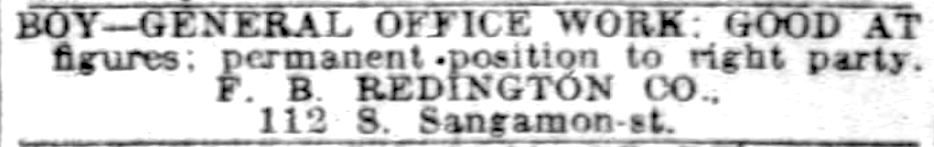

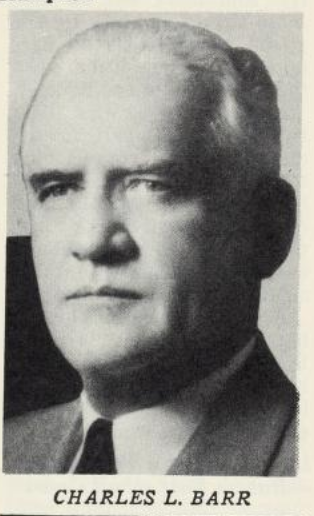

A year after Malhiot was hired, in 1919, Redington placed an wanted ad in the Tribune for a boy capable of “general office work” and who was “good at figures.” One respondent was a 26 year-old fresh out of the war (312 field artillery, 70th division, in France) named Charles L. Barr.

[The Tribune wanted ad that a young Charles Barr came across in 1919]

[The Tribune wanted ad that a young Charles Barr came across in 1919]

The son of Scottish immigrants, Barr came from a far more humble background than Redington himself, and he spent his early years at the company still living out of the nearby YMCA. To his own surprise, he was elevated from errand boy to on-the-road salesman by 1920, at the recommendation of vice president F. G. Brooks. Ten years after that, Barr was Redington’s sales manager, and by the onset of the next world war, he was the CEO, handling most of the daily duties for a now elderly Frank Redington, who was enjoying his salad days living at the Edgewater Beach Hotel with his wife.

Philip Hampson—the same Tribune writer who slightly overstated Frank Redington’s role in chewing gum history—profiled Charles Barr in 1953, and used some similar hyperbole, noting that Barr’s local fame as a Chicago high basketball star had outshined even that of baseball’s Babe Ruth. He then added:

Philip Hampson—the same Tribune writer who slightly overstated Frank Redington’s role in chewing gum history—profiled Charles Barr in 1953, and used some similar hyperbole, noting that Barr’s local fame as a Chicago high basketball star had outshined even that of baseball’s Babe Ruth. He then added:

“Charles [Barr] now heads a company that is unknown to most Chicagoans. The Redington company manufactures automatic machines which put hundreds of different things into neat packages of many types.

“Among hundreds of other items, the company’s machines package gum, macaroni, medicines, and meats. It is unlikely there is a person in the United States who has not used a product serviced by one of the company’s machines.”

The Final Countdown

Frank Redington finally retired from his business in 1953 at the age of 86, and died the following year—slightly shy of being a millionaire by some accounts of the time. One year after that, the F. B. Redington Company moved from its longtime Sangamon Street plant to a new one in suburban Bellwood, Illinois, where the Sanford Ink Co. also still maintained a facility. Family ties.

The Redington Co. merged with the packaging machinery division of the Crompton & Knowles company in 1960, and the Bellwood plant carried on with roughly 200 employees into the 1970s. The company was eventually re-named Redington Counters, with the home office in Connecticut, but the name and devices were purchased by Trumeter Technologies, Ltd, in 2011, with the plant in Windsor, Connecticut closing shortly thereafter.

The Redington Co. merged with the packaging machinery division of the Crompton & Knowles company in 1960, and the Bellwood plant carried on with roughly 200 employees into the 1970s. The company was eventually re-named Redington Counters, with the home office in Connecticut, but the name and devices were purchased by Trumeter Technologies, Ltd, in 2011, with the plant in Windsor, Connecticut closing shortly thereafter.

It may not be a legacy as glorious as Wrigley gum or Sharpie markers, but then again, those things might not have come about without the early influence of Frank Redington either. This is a man who should be rightfully counted among the great industrial innovators of his day, and as luck would have it, we have just the thing for doing some counting.

[Updated Redington gum wrapping machine patent from 1915]

[Updated Redington gum wrapping machine patent from 1915]

SOURCES

“The Road to Success: A Sketch of Charles L. Barr, Head of F. B. Redington Company,” by Philip Hampson, 1953

“Redington, 87, Executive and Inventor, Dies,” Chicago Tribune, Sept 24, 1954

“Illinois Cycling Club Athletic Entertainment,” The Wheel and Cycling Trade, Vol. V, no. 11, 1890

Annual Report of the Factory Inspector of Illinois: 1901-1902

Modern Packaging, Vol. 10, 1936

“C. J. Malhiot, invented gum pack opener,” Chicago Tribune, April 25, 1984

Iron Trade Review, Vol. 26, 1893

Simmon’s Spice Mill, December 1913

Archived Reader Comments:

“Great Article… must be in my blood… I design machines too.” —Jeff Redington, Rome, GA USA Sept. 2017

“I just rebuilt a 1908 redington counter. Found in basement under the stairs sitting water. Looks brand new now. Great piece of machinery.” —John V., 2017

“I owned and ran a press with a Redington counter for many years. Very reliable indeed. It appears Redington is now a subsidiary of Trumeter.” —Bruce Payne, 2017

What is one of these counters worth

I have one of these. What are they worth?