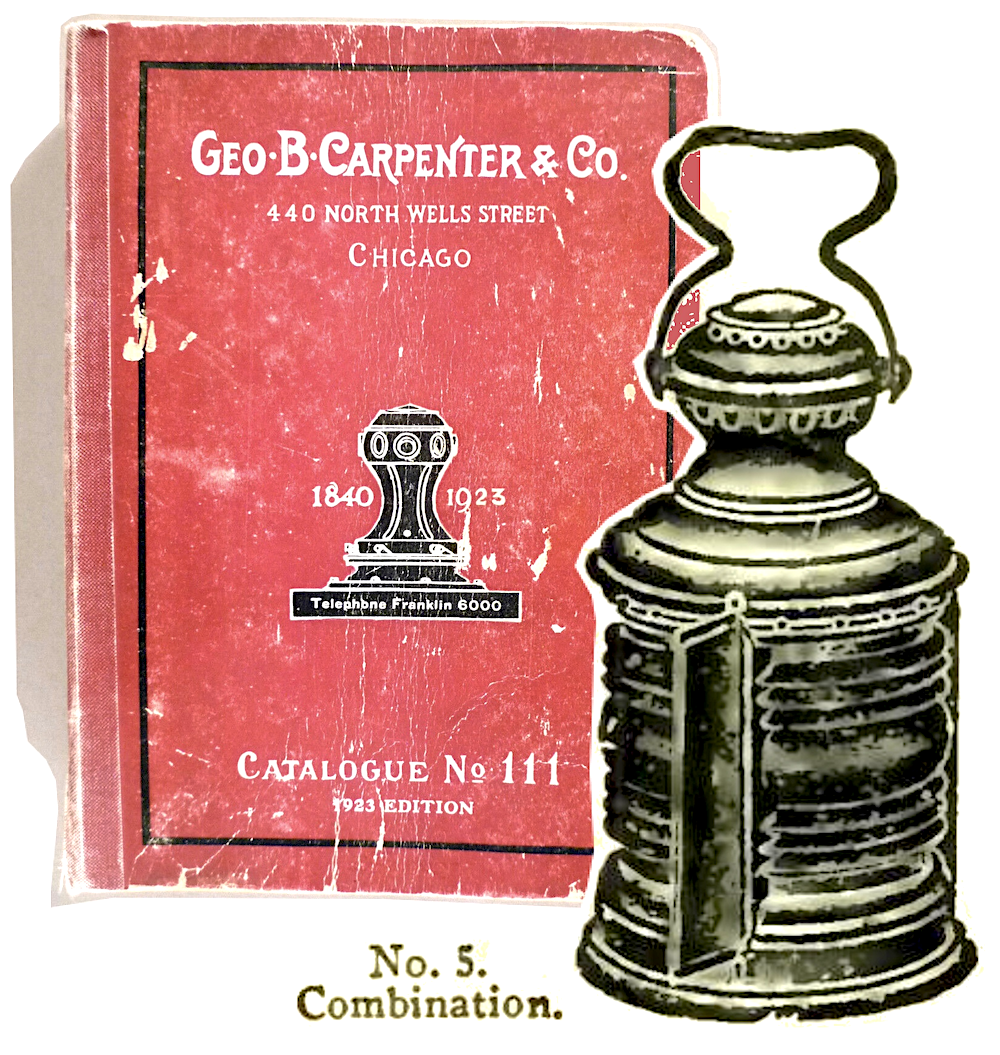

Museum Artifact: Nautical Lantern, 1910s

Made By: Geo. B. Carpenter & Company, 440 N. Wells St. [River North]

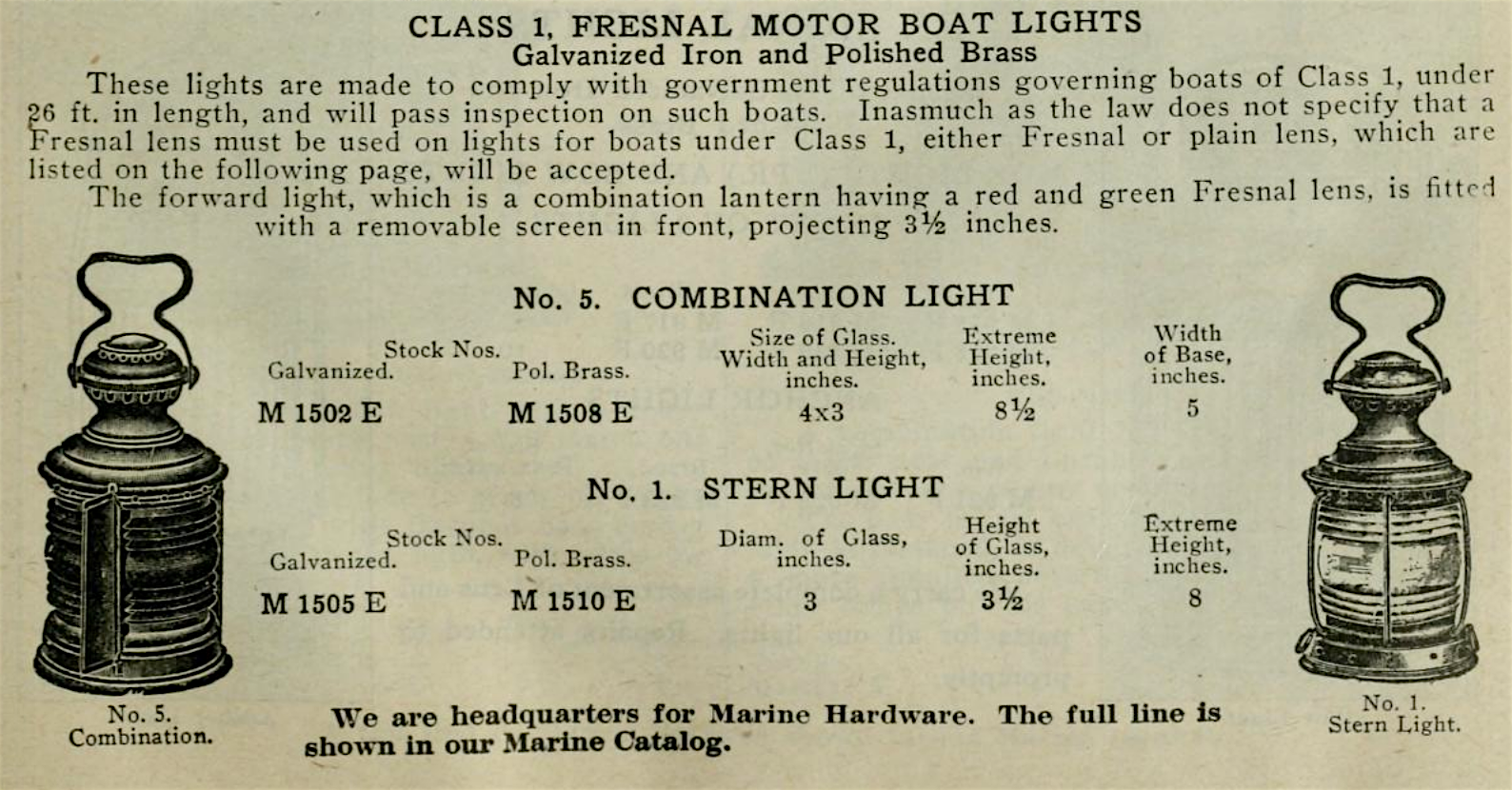

“Navigation lamp” or “nautical lantern” would be the more distinguished terms, but according to the official 1917 catalogue of George B. Carpenter & Co., the beat-up brass relic pictured above was actually categorized as a “motor boat light,” with a more specific designation as the “No. 5 Combination Light.” It originally would have included two separate Fresnel lenses (like the kind in a lighthouse), one green and one red, separated by a removable front screen—all of which, unfortunately, are AWOL in our artifact. The interior has a single-wick kerosene configuration, and the “combination” aspect refers to illuminating both the port and starboard side of a boat.

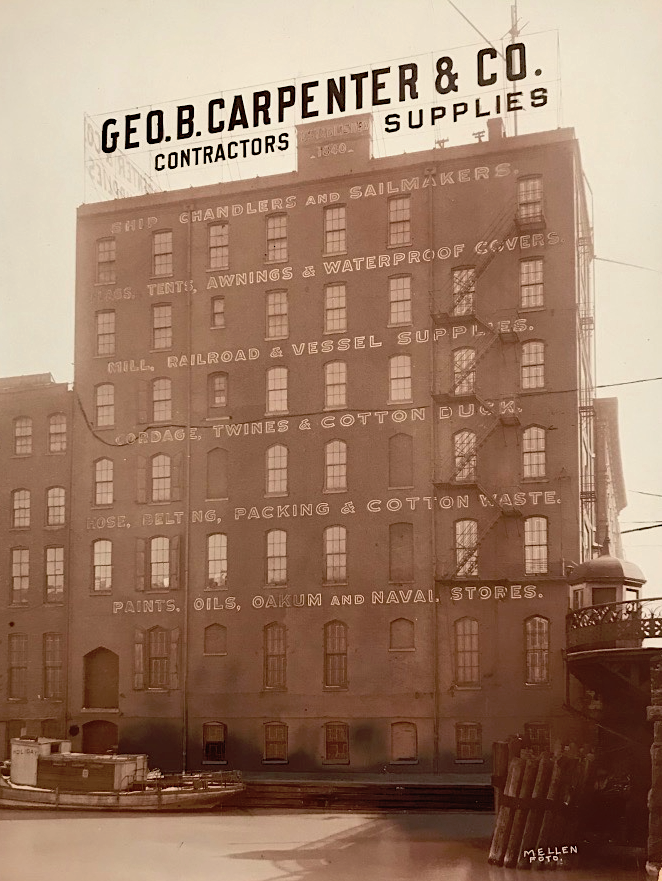

These early 20th century motor boat lights were part of a massive inventory of wholesale marine supplies that represented “the cornerstone of the Carpenter business,” according to the 1918 edition of Manufacturing and Wholesale Industries of Chicago. “There has always been a very definite link binding [Carpenter & Co.] to the maritime interests and to ‘the men who go down to the sea in ships.’ There is a good, old tarry smell which seems to permeate the various stockrooms, which suggests all sorts of romantic associations.”

These early 20th century motor boat lights were part of a massive inventory of wholesale marine supplies that represented “the cornerstone of the Carpenter business,” according to the 1918 edition of Manufacturing and Wholesale Industries of Chicago. “There has always been a very definite link binding [Carpenter & Co.] to the maritime interests and to ‘the men who go down to the sea in ships.’ There is a good, old tarry smell which seems to permeate the various stockrooms, which suggests all sorts of romantic associations.”

Feeding into that romance was the sheer age of the business, which could be tracked almost as far back as the establishment of Chicago itself. Long before George Carpenter had his name on the banner, journalists of the Victorian age were already gushing over this mighty beacon of American industrial ingenuity, built upon a great river, serving the needs of the ambitious, bold and seaworthy.

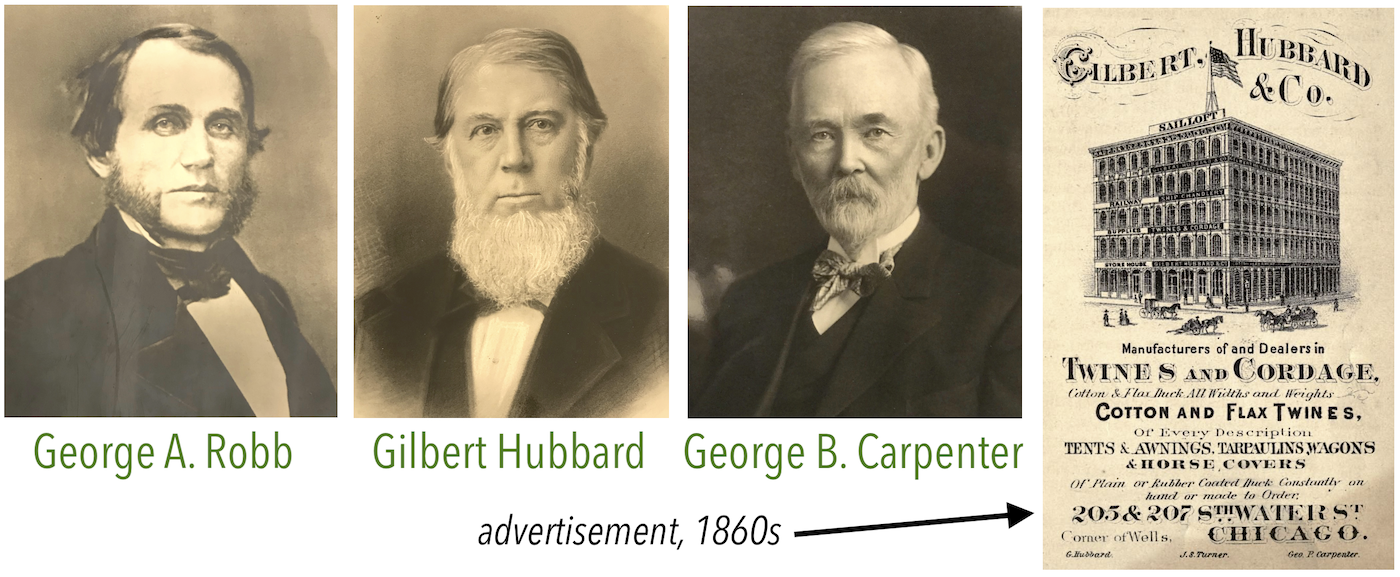

In 1862, right in the middle of the Civil War, History of Chicago author Isaac Guyer described the firm, which was then known as Gilbert Hubbard & Co., as if he worked for its sales department.

“Few great cities present such commercial attractions as Chicago, and few commercial houses represent so great and important an interest as the one of which this article will illustrate,” Guyer wrote, noting how the city’s 1,500 marine vessels and growing shipbuilding industry all depended on local tackling suppliers.

“The principal and leading one is that of Messrs. Gilbert Hubbard & Co.,” he continued, “who occupy that massive iron structure of architectural grandeur, which will defy the desolation of time and the spoil of ages, located on the corner of South Water and Wells Streets. If the reputation they have already attained, for sagacious, careful and honorable merchants, shall continue as unsullied by the hand of time as the iron building they occupy, long will they be proudly numbered with merchant princes. . . . Their long experience makes them masters of the business in all its minute details, as most of the sailing masters of the upper lakes can attest; their large capital enables them to produce the best articles at the lowest price.”

Notably, that “massive iron structure which will defy the desolation of time” actually burned to the ground in the Great Chicago Fire less than a decade later. But nonetheless, Guyer was at least partially correct in his assessment. This company was primed for longevity and influence.

History of Geo. B. Carpenter & Co., Part I: Sea Dogs and Prairie Schooners

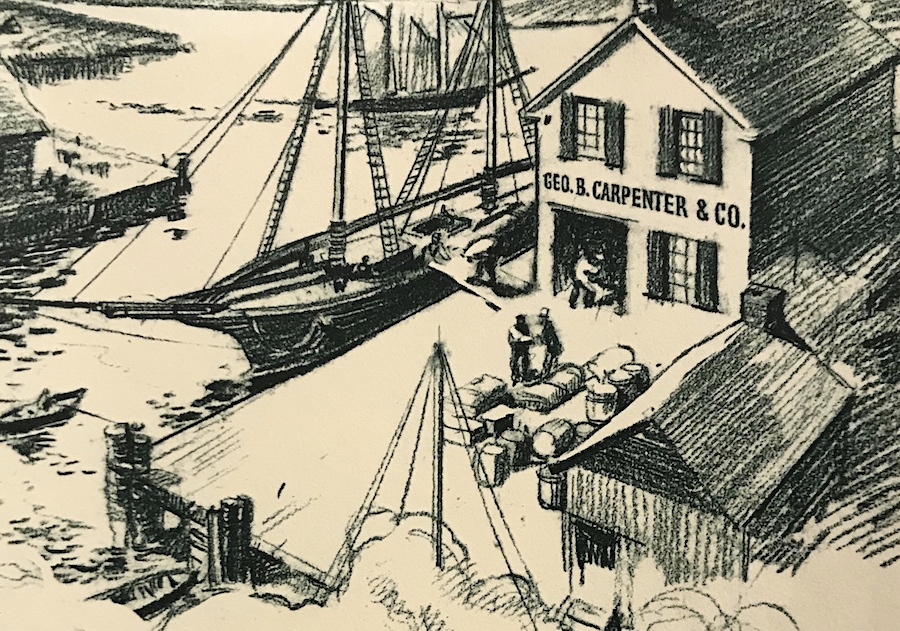

As noted, the seeds of the George B. Carpenter business can be found along the muddy banks of the Chicago River, when Fort Dearborn was still a stone’s throw away and the peppy town of Chicago had a population of less than 5,000. According to Carpenter’s own self-published company history, The First Hundred Years (1940), the business began in 1839, “under the name of Huginin and Pierce. Little is known of the original partners, except that they were sail makers and sold ship chandlery [supplies like sail cloth, nets, twine, lanterns, etc.] and groceries.”

A 1976 retrospective in the Chicago Daily News ventured a more playful depiction of the business, calling the original frame shop “one of Chicago’s most popular nautical hangouts in the 1840s. . . . Old salts from the schooners that clogged the river met there to swap sea tales, browse through the sail loft and buy ship supplies and groceries. It was there, too, that mud-caked pioneers came to buy canvas tops for the prairie schooners that would carry them on the voyage west.”

A 1976 retrospective in the Chicago Daily News ventured a more playful depiction of the business, calling the original frame shop “one of Chicago’s most popular nautical hangouts in the 1840s. . . . Old salts from the schooners that clogged the river met there to swap sea tales, browse through the sail loft and buy ship supplies and groceries. It was there, too, that mud-caked pioneers came to buy canvas tops for the prairie schooners that would carry them on the voyage west.”

As one would expect in a frontier town, ownership of the firm changed often, as Huginin and Pierce eventually gave way to George A. Robb and Gilbert Hubbard, forming Hubbard & Robb in 1850, which then became just Gilbert Hubbard & Company after Robb’s death in 1857. That same year, a youngster named George Benjamin Carpenter, age 23, left the successful Chicago meatpacking plant run by his father (Benjamin Carpenter) to buy a one-third share in Hubbard’s less bloody enterprise.

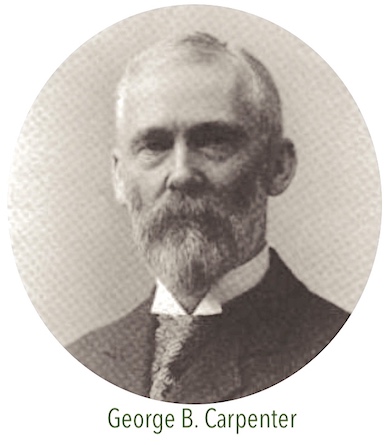

Carpenter (b. 1834) came from old colonial New England money, just like Gilbert Hubbard (b. 1819), so the latter proudly mentored the former in all things relating to industrial-scale ship equipping.

Despite Chicago’s rapid growth during this period, there were still numerous obstacles on the horizon. During the Civil War, the firm had to switch over to filling orders for the Union Army, including making tents for military camps. Then came the double-whammy of the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 and the Great Panic of 1873, which turned the old Hubbard warehouse to ash, then, once rebuilt (directly across the street at 202 South Water St.), saddled it with an economic depression.

The company survived largely by broadening its horizons, as Carpenter and Hubbard used their fortunes and connections to entice a clientele beyond the shipyards, selling bulk hardware and supplies to mining companies, mills, and the predominant new form of industrial mass transport: the railroads.

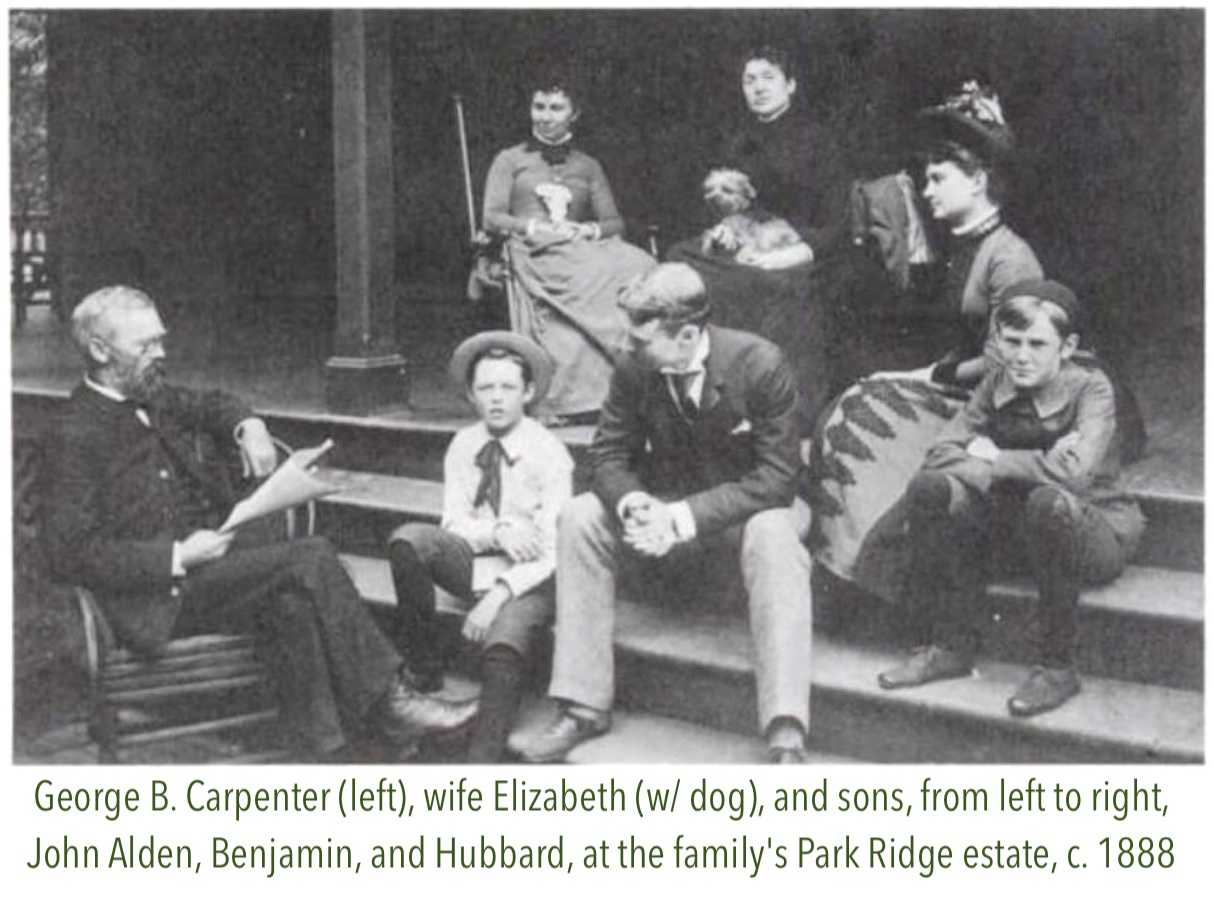

Then, in 1881, George B. suddenly lost both of the central mentors in his life; his father Benjamin and Mr. Hubbard, each of whom he’d named a son after. Following Hubbard’s death, the business was officially re-organized—presumably with the blessing of the Hubbard family—as George B. Carpenter & Co.

“The vast business of the old concern passed into the hands of Geo. B. Carpenter & Co.,” recounted the 1886 ed. of Marquis’ Handbook of Chicago, “and they have since managed it with the same far-reaching enterprise and unswerving integrity that characterized the old establishment through so many years of eventful history. Today, Geo. B. Carpenter & Co., constitute the oldest and most favorably known ship chandlery house in the west. . . . And they have been prominently identified with every step of the commercial development of Chicago for more than a quarter century.”

“The vast business of the old concern passed into the hands of Geo. B. Carpenter & Co.,” recounted the 1886 ed. of Marquis’ Handbook of Chicago, “and they have since managed it with the same far-reaching enterprise and unswerving integrity that characterized the old establishment through so many years of eventful history. Today, Geo. B. Carpenter & Co., constitute the oldest and most favorably known ship chandlery house in the west. . . . And they have been prominently identified with every step of the commercial development of Chicago for more than a quarter century.”

Praise always seemed in ample supply from the journos and guidebook writers of this period, so either Carpenter & Co. was as esteemed as these authors would suggest, or the company excelled in public relations as much as it did in making burlap sacks and sailcloth. Either way, business was booming.

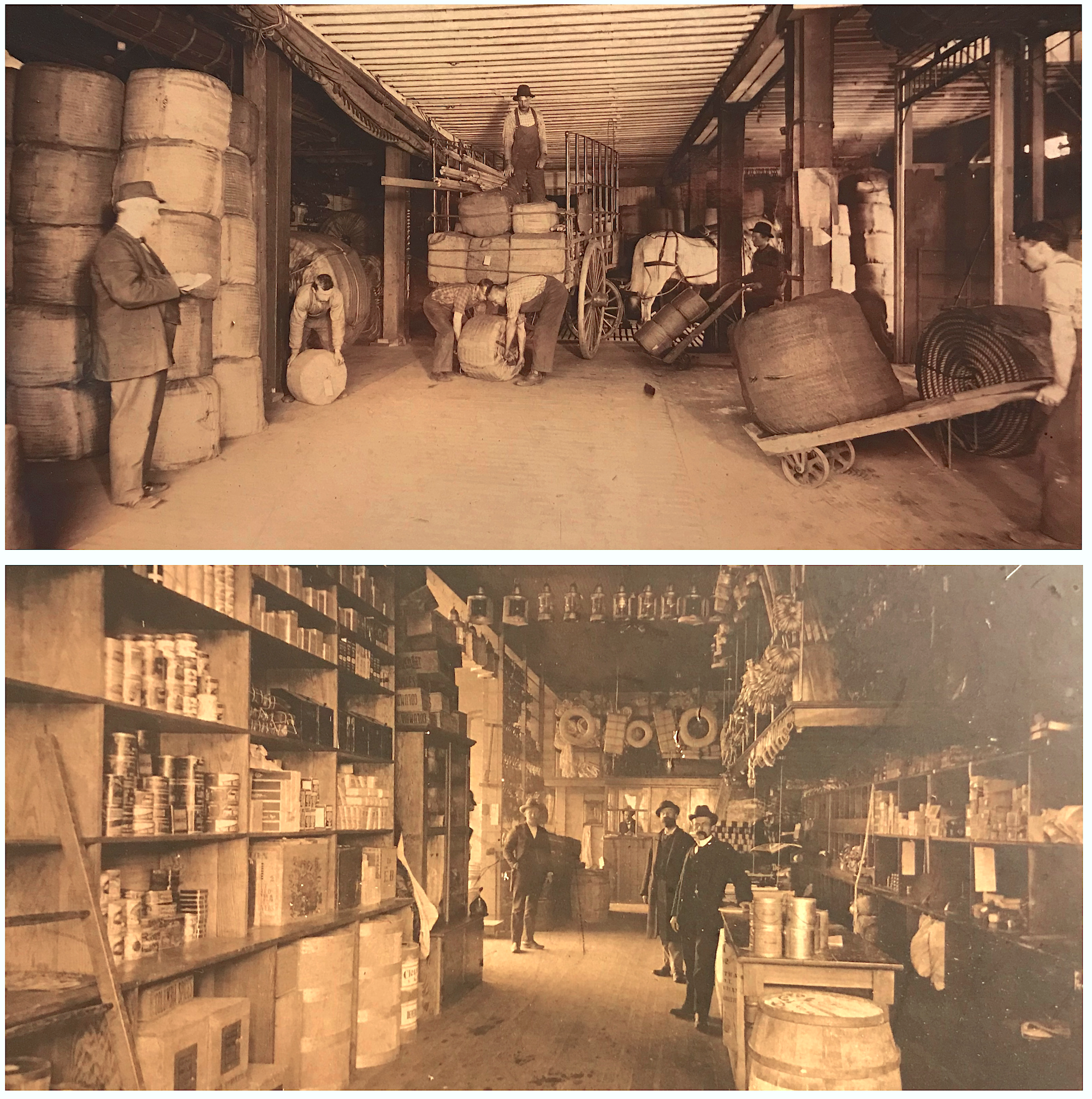

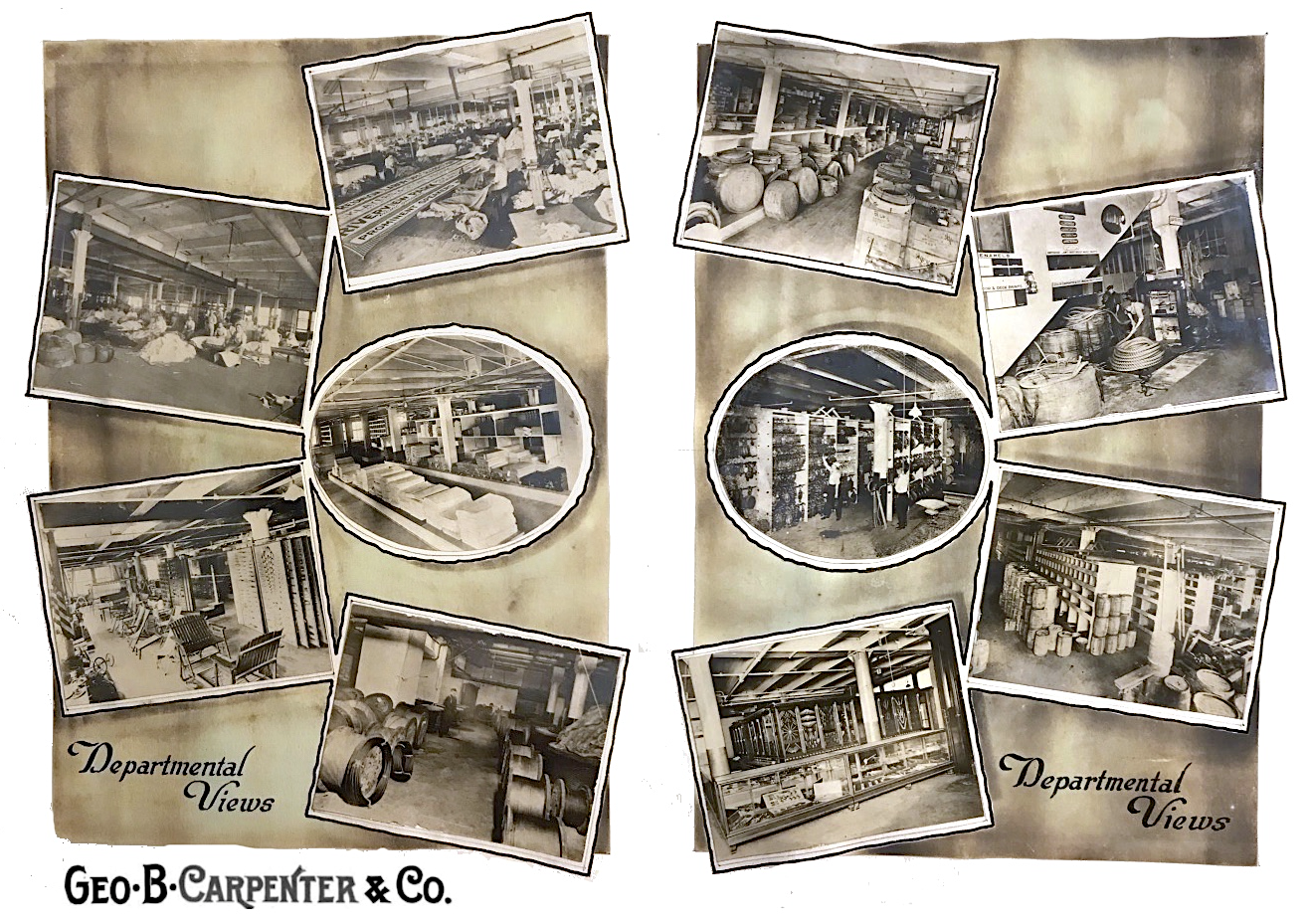

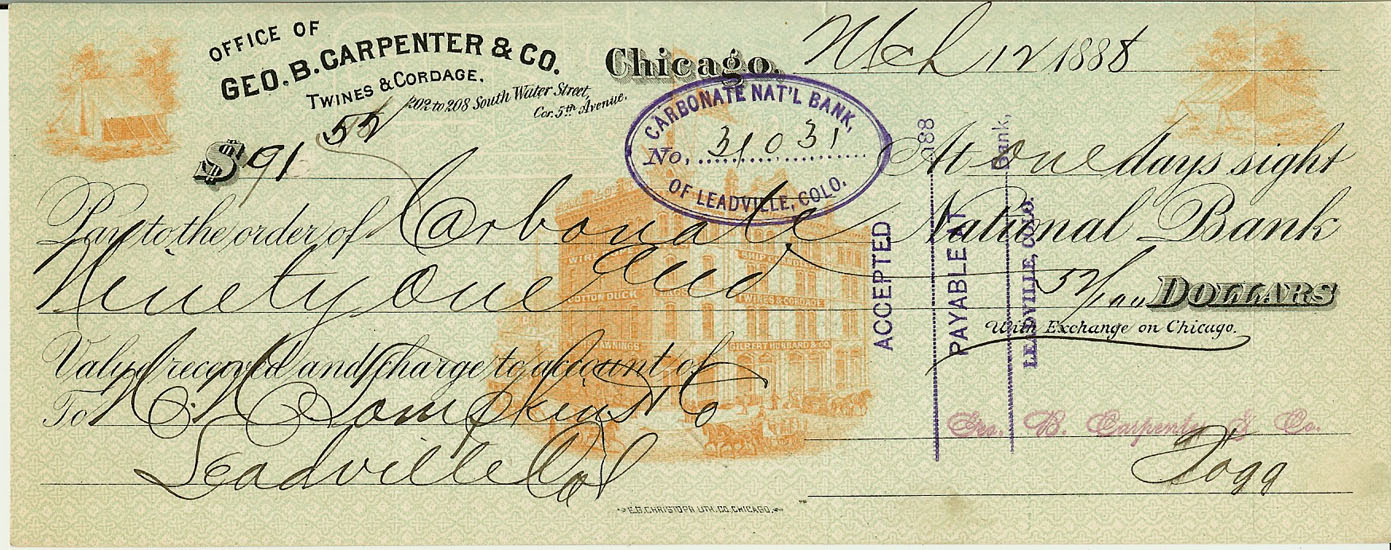

By 1890, Carpenter’s main four-story headquarters at 202-208 South Water Street was one of the more familiar buildings in the Chicago “skyline,” such as it was. There were 100 employees in the company’s employ, and while the manufacturing of “vessel supplies” was still an ample part of the business, the catalog was mainly filled out with goods distributed on behalf of other suppliers from back East—cordage from the Sewall & Day Cordage Co., twine from the Ludlow MFG Co., cotton duck from Brinckerhof, Turner & Co., rubber goods from the Peerless Rubber MFG Co., and on and on.

“Almost everything can be bought in Chicago,” the 1891 catalogue noted, “and being large buyers of all kinds of merchandise, we can sell anything desired at prices as low as the lowest.”

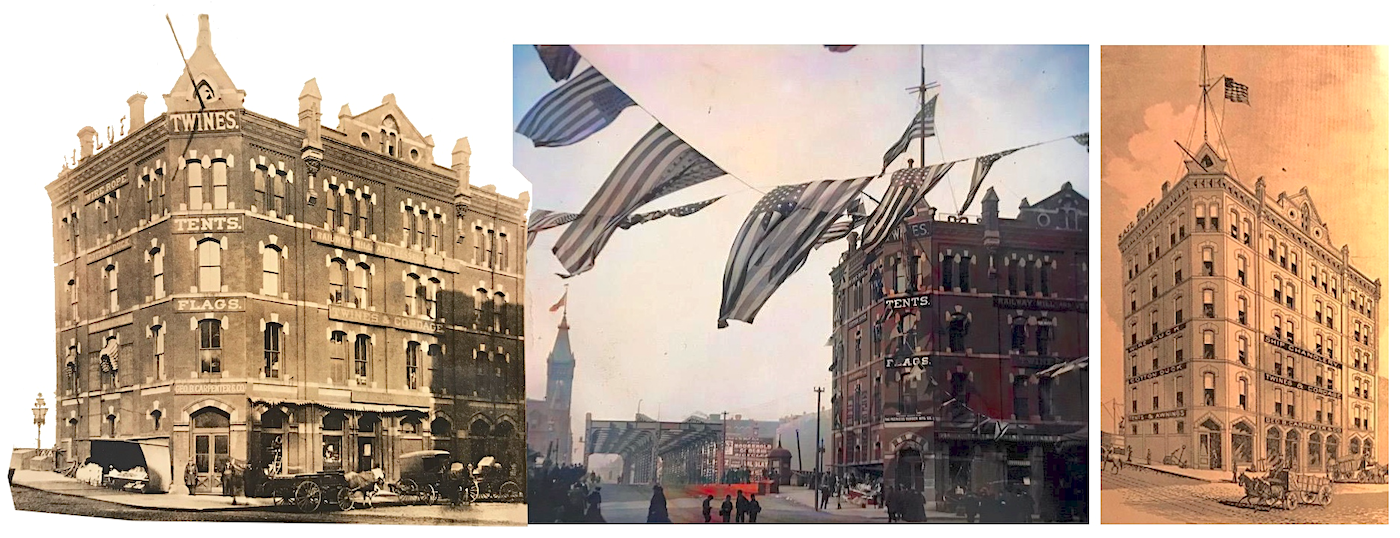

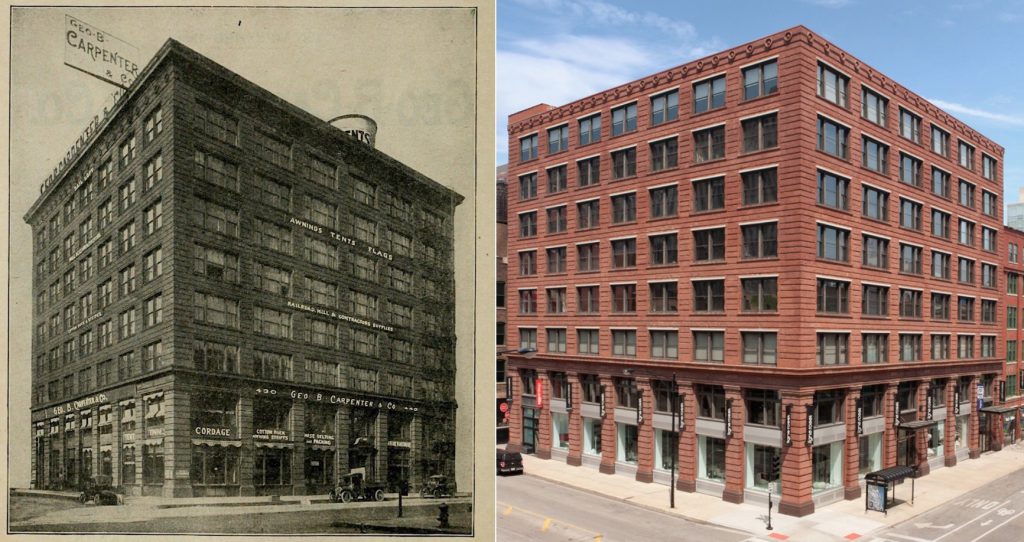

[Above: Three views of the Geo. B. Carpenter building at 202-208 South Water Street, from left to right: Photo (c.1890s), colorized photo (c. 1890s), sketch of renovated building with two added floors (c. 1905). Below: Interior views of part of the Carpenter warehouse and store, c.1900]

After a fire in 1900, the South Water Street building was renovated with two additional stories. That same year, a 66 year-old George B. Carpenter was asked to explain his success as part of a company profile in the book, A History of the City of Chicago: Its Men and Institutions. The interviewer was, presumably, a young man.

“Young man,” Carpenter told him, “I attribute the success of our house very largely to our old fashioned method of doing business on the square, insisting that agreements must be kept and bargains lived up to, no matter what the cost. Of course, it is well to have around you men who will not make agreements which they cannot fulfill, or bargains which are not bargains, and who are not always watching the clock.”

The interviewer made a point of noting that Carpenter delivered that last line with a “twinkle in his eye.” And that does seem weirdly relevant. From most accounts, George B. Carpenter wasn’t just the nose-to-the-grindstone taskmaster type. He was a thoughtful gent and a humanitarian, giving a lot of his substantial wealth to local charities. After his death in 1912, more than 1,000 books from his personal collection were donated to help jumpstart a public library near his home in Park Ridge, Illinois.

The interviewer made a point of noting that Carpenter delivered that last line with a “twinkle in his eye.” And that does seem weirdly relevant. From most accounts, George B. Carpenter wasn’t just the nose-to-the-grindstone taskmaster type. He was a thoughtful gent and a humanitarian, giving a lot of his substantial wealth to local charities. After his death in 1912, more than 1,000 books from his personal collection were donated to help jumpstart a public library near his home in Park Ridge, Illinois.

An associate once said of George, “In all of the years of my work with Mr. Carpenter, I have never yet seen him lose his temper, although on many occasions provocation was great! No matter how busy, he was always easy to approach and listened to the story with patience; his decision was always prompt and to the point, and these characteristics he has imparted to all those who now divide the burden of steering his ship along its progressive course.”

[Colorized photo of workers outside the Geo. B. Carpenter building on South Water Street, c. 1900]

II. The Next Generation

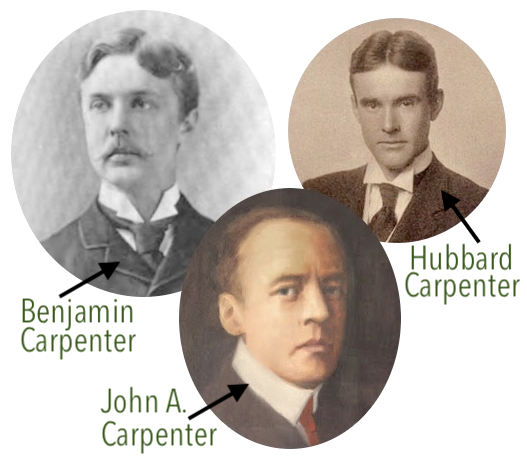

As much as the Carpenter family had become associated with Chicago and integral to its 19th century emergence, George B. remained an upper-crust New Englander at heart. As such, all four of his sons went back east to earn their degrees at Harvard. One of them, George A. Carpenter, went into law and became a federal judge, but the other three—Benjamin, Hubbard, and John Alden—all wound up in the family business.

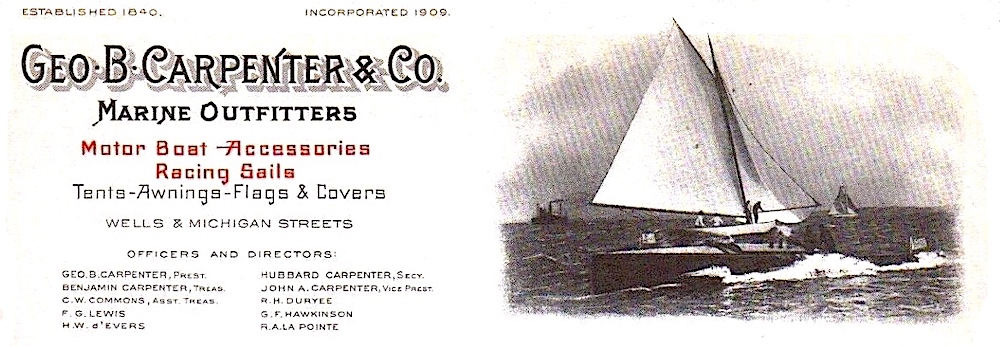

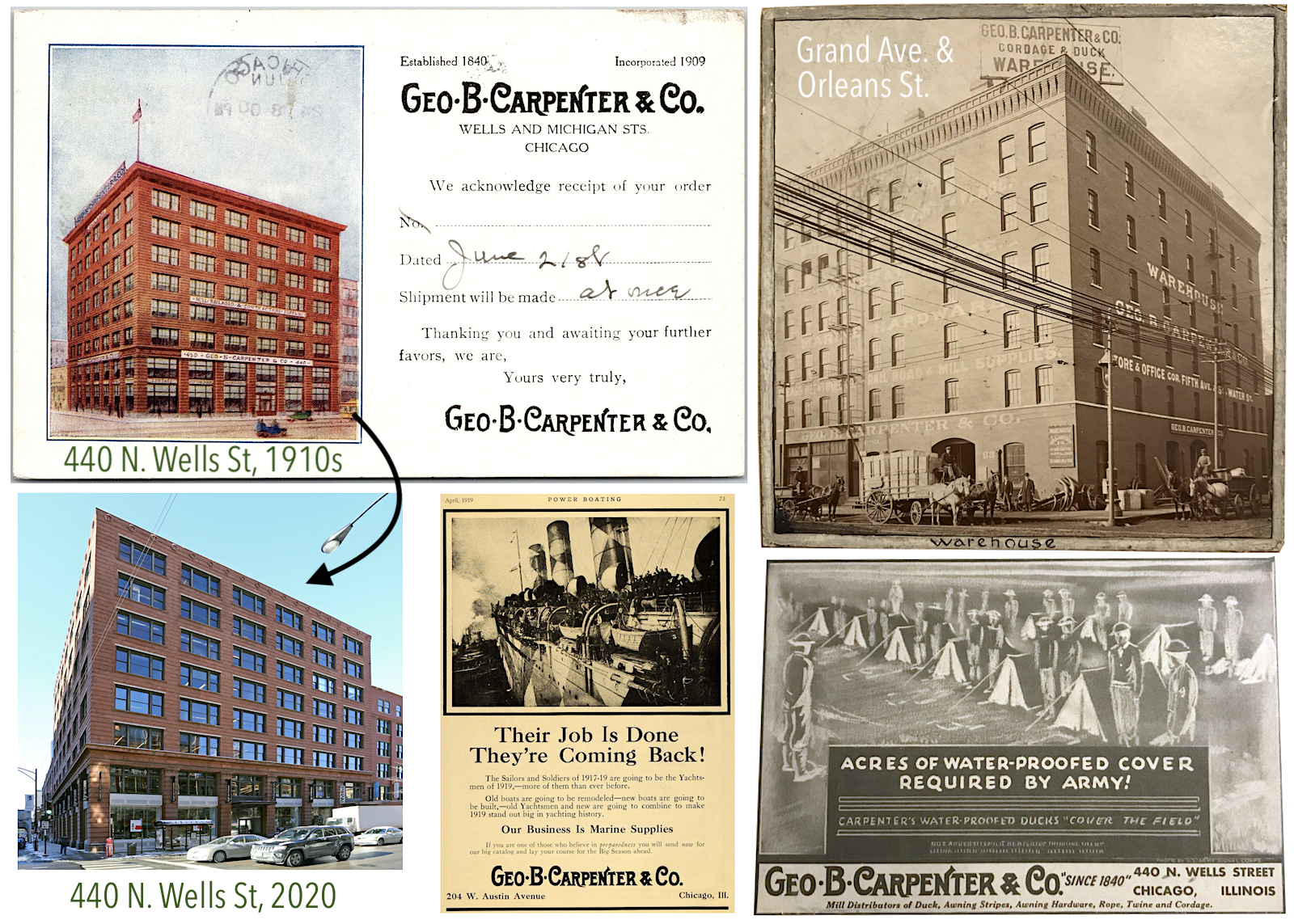

In 1912, following the death of George B. at the age of 78, the new generation was officially in charge, with Benjamin Carpenter (b. 1865) as president, Hubbard Carpenter (b. 1874) as secretary, and John Alden Carpenter (b. 1876) as vice president. That same year, a new main office was established at 440 N. Wells St., to go along with a large warehouse at Grand Avenue and Orleans Street and a subsidiary store, known as the Great Lakes Supply Company, on the South Side (3207-17 E. 92nd Street).

In 1912, following the death of George B. at the age of 78, the new generation was officially in charge, with Benjamin Carpenter (b. 1865) as president, Hubbard Carpenter (b. 1874) as secretary, and John Alden Carpenter (b. 1876) as vice president. That same year, a new main office was established at 440 N. Wells St., to go along with a large warehouse at Grand Avenue and Orleans Street and a subsidiary store, known as the Great Lakes Supply Company, on the South Side (3207-17 E. 92nd Street).

Part of the Wells Street complex, sometimes listed at 201 W. Illinois Street, was Carpenter’s tent and awning manufacturing department, which employed 71 people (40 women and 31 men) in 1912. That number would rise significantly during the years of World War I, as the company again became a major supplier of canvas goods for the military. Much of this effort was led by Ben Carpenter himself, who joined the Quartermaster’s Corps in 1917 (at the age of 52) and reached the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel by the end of the conflict.

[A Then-and-Now look at the former Geo. B. Carpenter offices at 440 N. Wells Street, left, which was the company home from 1912 to 1952. The long-running warehouse at Grand Ave. and Orleans St. is picture top right, and a pair of World War I era ads are included bottom right.]

Benjamin, who was known as “B.C.” by his cohorts, was described as a “handsome, dynamic, Teddy Roosevelt type of man” in the company’s 100th anniversary book. “He seemed to have boundless stores of energy, and no detail of the business was ever too small to receive his personal attention. . . . He could crack the whip of discipline when necessary,” but also had a “great sense of humor—his buoyant laugh would often ring throughout the office. He was more concerned with the spirit in which a thing was done than he was with minor blemishes on the cold face of dignity, and he always had time for kindly little acts which mean so much to employees, big or little.”

B.C. led the business through its last glamorous, fat-catalog era in the 1920s, presiding over six departments: Marine Supplies, Hardware, Cordage, Cotton Duck & Awning Stripes, Mechanical Rubber, and Manufactured Canvas Goods. By most accounts, Carpenter & Co. was still the country’s No. 1 supplier of rope and twine. Benjamin’s sons, Ben Jr. and Fairbank, were also now executives in the business and seemingly the heirs apparent. After Ben Sr. fell ill in 1925, however, things began to shift in a less promising direction.

Benjamin Carpenter, Sr., died in 1927, aged 61, and while his brothers and sons took up the mantle, they couldn’t have anticipated the economic cataclysm awaiting them.

Hubbard Carpenter, for one, decided the challenges of the Depression weren’t worth the misery, and he retired from the company presidency in 1931. Younger brother John stayed on a little while longer, but his life’s passion had long since drifted away from the warehouse and into the arts.

Inspired by his mother Elizabeth, who was a fine singer, John Alden Carpenter began dabbling in songwriting as a youngster, and ultimately studied music at Harvard under famed composer John Knowles Paine. Rather than choosing between the family business and this more creative pursuit, however, Carpenter found a way to thread the needle and do both.

Inspired by his mother Elizabeth, who was a fine singer, John Alden Carpenter began dabbling in songwriting as a youngster, and ultimately studied music at Harvard under famed composer John Knowles Paine. Rather than choosing between the family business and this more creative pursuit, however, Carpenter found a way to thread the needle and do both.

From 1909 to 1936, John spent his days in the executive offices of Geo. B. Carpenter & Co., but by night, he was becoming an increasingly relevant modernist composer, writing a wide range of piano pieces, song cycles, and orchestral suites, some of which were met with wide acclaim. Carpenter’s jazz-inspired ballet Skyscrapers (which the New York Times later called “raucous, sassy and outrageous”) was produced at New York’s Metropolitan Opera in 1926, influencing the likes of George Gershwin. But back in Chicago—the city that had largely inspired the music—many of John’s employees and clients in the old marine supply biz remained completely unaware they were in the presence of a great artist.

John Alden Carpenter certainly could have left his desk job at any point to focus on his music, but he remained at his post right up until the sale of the company in 1936. Was it a sense of devotion? The dependable paycheck? An enjoyment of the distractions or inspirations from the daily grind? I guess you might have to listen to the music to figure it out.

[“Skyscrapers” (1924) by John Alden Carpenter (pictured top center), performed by the London Symphony Orchestra. While this jazz ballet is widely associated with New York City, Carpenter was a born and bred Chicagoan.]

III. Carpenter After the Carpenters

While Carpenter & Co. wasn’t done in by the Great Depression, it was certainly transformed by it. In 1931, the same year Hubbard Carpenter opted to retire from the business, John Alden Carpenter’s future plans were put into question when his wife Rue Winterbothom Carpenter—a successful designer and interior decorator (and president of the Arts Club of Chicago)—died unexpectedly from high blood pressure complications.

With John in mourning and his nephew Benjamin Jr. not interested in leading the business (he later became a physics teacher), the company was gradually consolidated and put on the market. Four of the six departments—Marine Supplies, Heavy Hardware, Mechanical Rubber Goods, and Manufactured Canvas Goods—were discontinued outright, and Carpenter & Co. essentially repositioned itself as a distributor for eastern suppliers, rather than a maker of its own products.

With John in mourning and his nephew Benjamin Jr. not interested in leading the business (he later became a physics teacher), the company was gradually consolidated and put on the market. Four of the six departments—Marine Supplies, Heavy Hardware, Mechanical Rubber Goods, and Manufactured Canvas Goods—were discontinued outright, and Carpenter & Co. essentially repositioned itself as a distributor for eastern suppliers, rather than a maker of its own products.

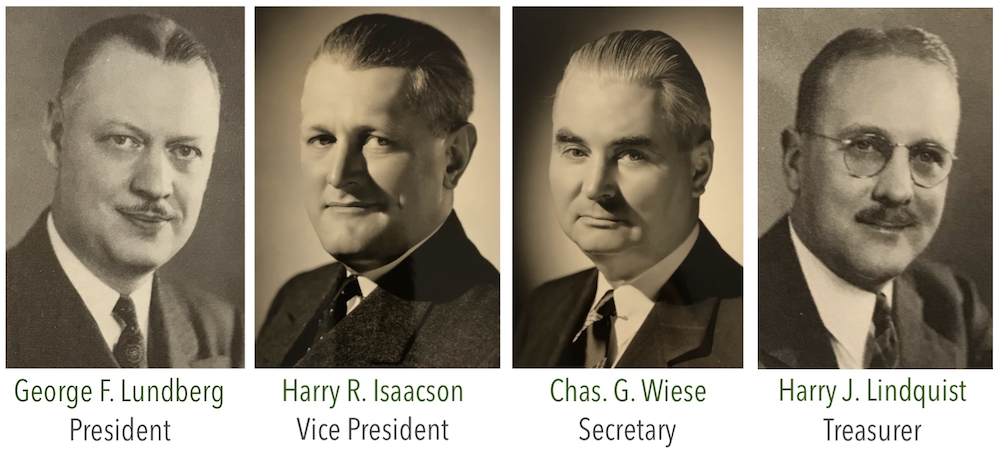

In 1936, the company was consolidated with another Chicago awning hardware and supply firm, Lundberg, Inc., and that company’s president, George F. Lundberg, took the reins of the business going forward. The Carpenter family was no longer connected to Geo. B. Carpenter & Co., but Lundberg and V.P. Harry R. Isaacson were at least joined by a couple veterans of the old Carpenter firm, including Harry J. Lindquist (treasurer), who’d joined the business out of high school back in 1919; and Charles G. Wiese, secretary, the first office boy Benjamin Carpenter ever hired back in 1898.

[Geo. B. Carpenter’s new Carpenter-free executive board in 1936, following its merger with Lundberg, Inc.]

The new ownership showed an encouraging respect for the century-long legacy of the Carpenter name. It didn’t hurt that they were still based out of the same building on Wells Street, with 34 employees already more than a decade into their time with the firm.

Employee parties, dances, and events were held even during the rougher patches of the Depression, and in 1940, much effort was put into promoting the company’s 100th anniversary.

[Carpenter employees at a cheerful hat-themed party of some sort in 1936]

After WWII, Carpenter & Co. simply carried on as a much smaller, more specialized business than the one that once put out 700-page catalogs as the norm. Harry Lindquist became company president and remained so well into his 70s—a link to the old days and a true “lifer” who lived and breathed the business. In 1952, after 40 years in the Wells Street building, he relocated the warehouse and offices to 401 N. Ogden Avenue, where it would remain for the next few decades, concentrating on cotton duck and cordage.

As best we can tell, Carpenter & Co. became a division of the Astrup Company—a longtime awning rival based in Cleveland—sometimes in the 1960s, but continued to operate out of the Ogden Avenue plant into the 1980s.

“This isn’t a spectacular business,” Lindquist told the Chicago Daily News in 1976, “but we’ll be around at least another 100 years if we keep our noses clean, are ready to change, and hold on to our reputation.”

“This isn’t a spectacular business,” Lindquist told the Chicago Daily News in 1976, “but we’ll be around at least another 100 years if we keep our noses clean, are ready to change, and hold on to our reputation.”

Linquist did his best. After his death in 1990, the Astrup Company eventually fell under the umbrella of another awning business called TRI Vantage, which still exists and, according to a few sources, still counted Geo. B. Carpenter & Co. as a loose sub-division of its operations into the 21st century. As of 2021, however, the website of the Professional Awnings Manufacturers Association now suggests that the legal claim to the Carpenter legacy belongs to a local business called the Evanston Awning Company, which may have purchased the rights at some point, though no current Carpenter-branded products appear to be in circulation any longer.

It’s not the grand fate that wide-eyed journalists were envisioning for the mighty Carpenter firm 150 years ago, perhaps, but sometimes even the brightest lantern can only shine so far into the mists of a Great Lakes night.

A special thank you to Cameron Weldon for finding and donating many of the old photos and catalogues utilized in this research. Cameron worked for the Astrup Company at the Ogden Avenue building, and his father worked for both Astrup and Geo. B. Carpenter & Co.

[Geo. B. Carpenter 100th Anniversary Dinner at the Park Ridge Country Club, June 6, 1940.]

[The former Geo. B. Carpenter headquarters at 440 N. Wells St., 1917 and 2016]

[The former Geo. B. Carpenter headquarters at 440 N. Wells St., 1917 and 2016]

[Inside the warehouse and offices, c. 1950s]

Sources:

History Of Chicago: Its Commercial And Manufacturing Interests And Industry, by Isaac D. Guyer, 1862

Marquis’ Handbook of Chicago: A Complete History, Reference Book and Guide to the City, 1886

A History of the City of Chicago: Its Men and Institutions, 1900

Geo. B. Carpenter Catalogue No. 110, 1917

Manufacturing and Wholesale Industries of Chicago, by Josiah Seymour Currey, 1918

Geo. B. Carpenter Catalogue No. 222, 1928

1840-1940: The First Hundred Years, by Geo. B. Carpenter & Co., 1940

“Carpenter Co., from Sailcloth to Macrame in Its 136 Years” – Chicago Daily News, Feb 2, 1976

“Retired Executive F. Carpenter” – Chicago Tribune, April 5, 1983

“Moving” – Chicago Tribune, July 20, 1952

Archived Reader Comments:

“Apparently they also made cloth and canvas items for the War Effort- I have a very good photos of a Class-B Standardized Military ‘Liberty’ Truck built at Diamond T in Chicago where the canvas cover of the cargo bed clearly shows ‘Geo B Carpenter & Co.’ which is fascinating to me since they appear to have focused more on nautical supplies…” —Ian, 2018

“I have a Chelsea ship clock and on the face of the clock it says GEO B. CARPENTER & CO. CHICAGO My Grandfather gave me the clock in 1960. I don’t know where he got it from.” —Gregory Stasch, 2018

Hi. I have a very old yard stick from Geo.B. Carpenter. Listed as “since 1840- Geo.-B. Carpenter – Chicago 22 , IL. Phone SEeley 8-3670. Wondering if you have one like it. Condition is 9/10..

How many employees did they have at 401 Ogden Avenue chicago around 1950s.

The Astrup Awning Company headquarters on West 25th Street in Cleveland, Ohio, was absorbed by Trivantage of North Carolina which supplied Astrup with canvas. In 2017, Trivantage moved the Astrup operation, by then reduced to a distribution facility, from the city setting out toward a more efficient location near the turnpike and airport. The 73,000 sf complex on W 25th, contiguous to the Ariel Castro site, was transferred to a company headed by me to be renovated and converted into the Pivot Center for Art, Dance & Expression.

Today a dozen organizations, largely non-profits like the Cleveland Museum of Art, Inlet Dance Theatre, ICA Conservation Art, and Future Ink Graphics, have reinvigorated the complex now listed on the National Register of Historic Places following a $14-million complete rehab and upgrade.

We have a galvanized lantern with blue freznel glass if anyone is interested in making an offer, I can be contacted at beverly0223@netzero.net

Thanks! Thought this was a good place to offer it up!

Be Blessed Everyone!

Beverly G

George Benjamin Carpenter is my third-great grandfather on my mother’s side. It is so amazing to be a part of this amazing person’s lineage.

Would you be interested in pictures of one that is in good shape?

My father, Arthur E. Stollfuss, was Secretary/Treasure of Geo. B. Carpenter & Co.

My rather died in 1981,

The company sold Rope, Twine, and Cordage products.

My father enjoyed working for George F. Lundberg.

Les Stracken, and Jim Anderson also worked there at the time of my father.

Any information you can sen me would be appreciated.

To: Andrew Clayman

My grandfather, George F. Lundberg, was the president of George B. Carpenter in 1940. At that time he had commissioned an author to produce a 30 page document that describes the history of George B Carpenter from 1840 to 1940. The publication is entitled “1840 to 1940 The First Hundred Years”. This book was then mailed to all of George B. Carpenter’s clients and company members. Attached was a letter from my grandfather explaining the project. I do have an extra copy in pristine condition, never opened or used, including my grandfather’s letter. I would be willing to donate it to your collection for furthering the study of made in Chicago. Please send pertinent info to my email. I can send a photo to your email of the publication and letter before hand.