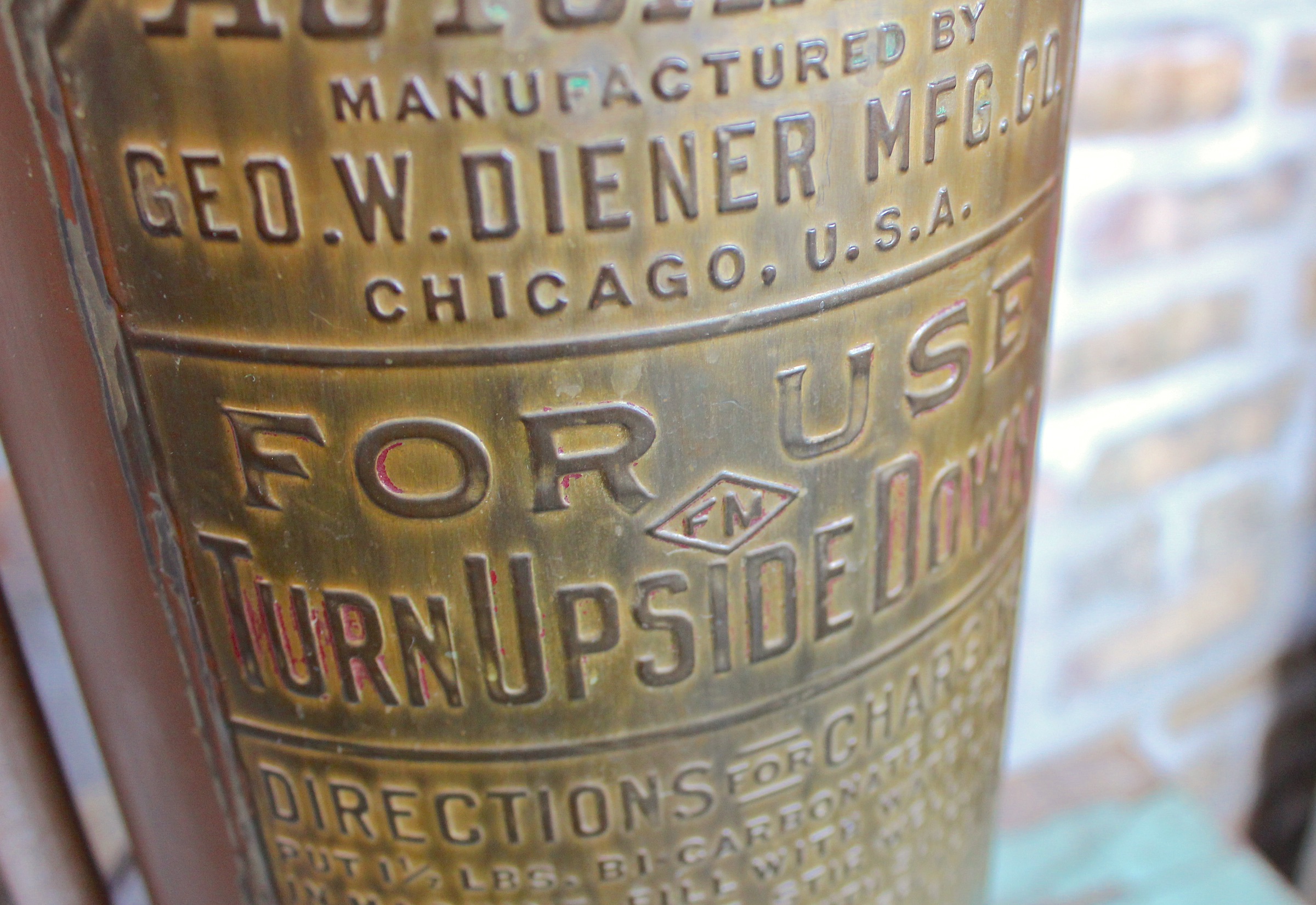

Museum Artifact: Automatic Fire Extinguisher, c. 1920s

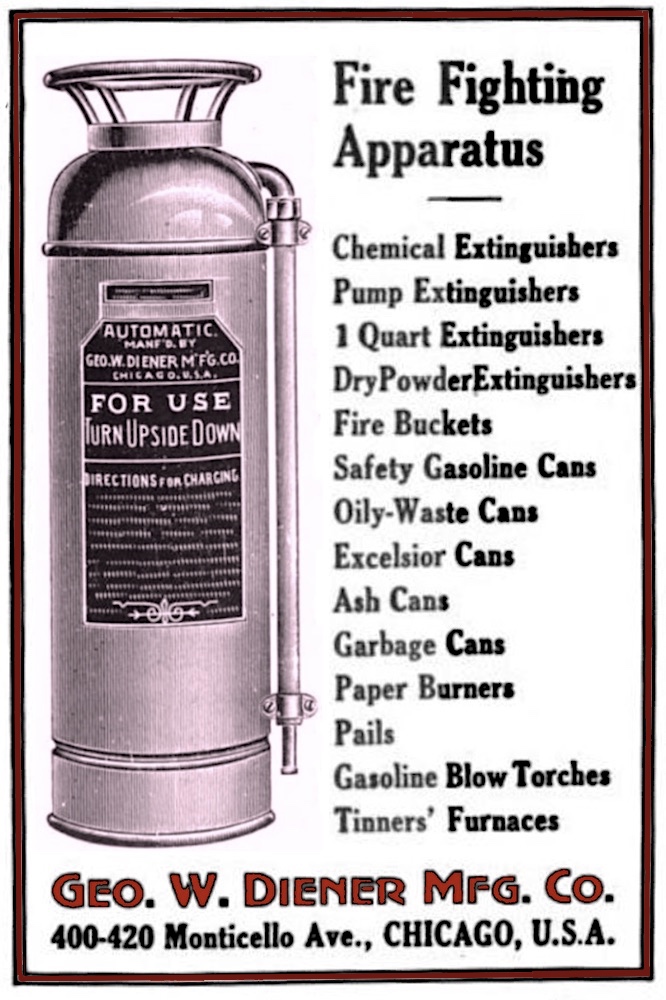

Made By: Geo. W. Diener MFG Co., 400-420 N. Monticello Ave., Chicago, IL [East Garfield Park]

“Fire Insurance is always an unsatisfactory recompense for fire loss. Fire prevention is better. We manufacture everything for fire prevention and fire fighting.” –Geo. W. Diener MFG Co. advertisement, 1921

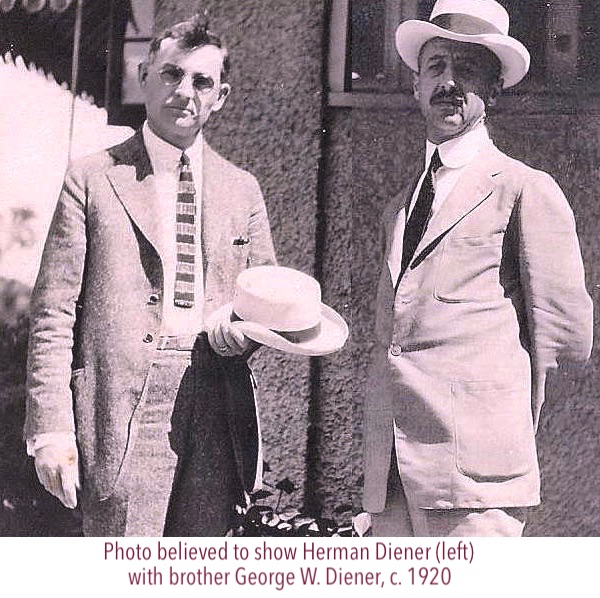

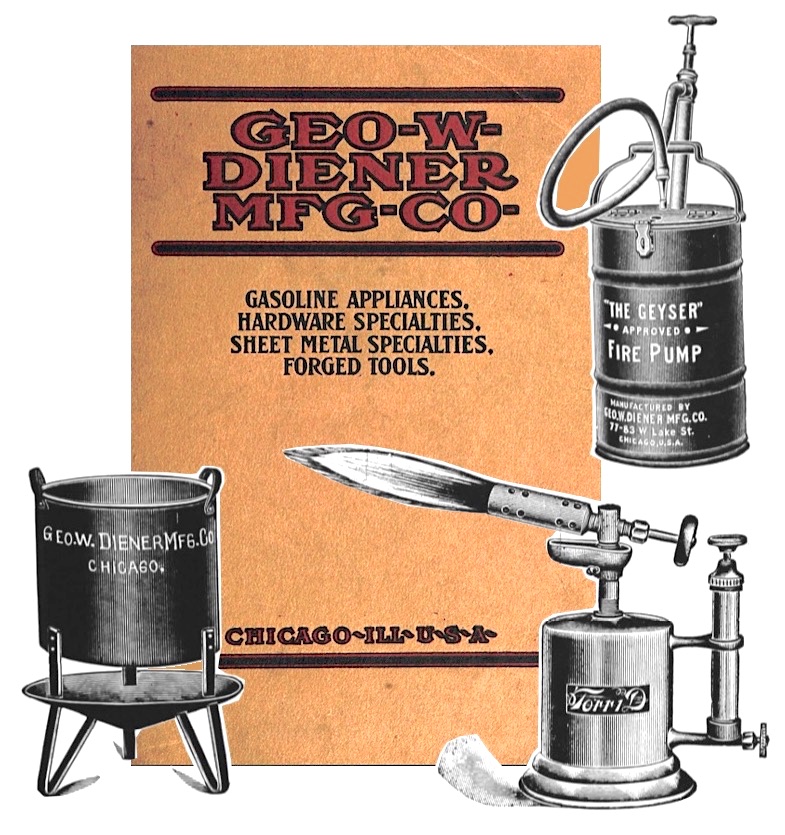

While only one of their names went on the banner, the Geo. W. Diener Manufacturing Company was really a sibling partnership, guided for decades by the titular George (president) and his kid brother Herman W. Diener (vice president). The duo initially specialized in blow torches, brazers, forged tools, and industrial containers, but the Diener name reached its widest recognition in the objectively rad field of fire-fighting appliances, which they produced from the 1910s all the way into the 1960s.

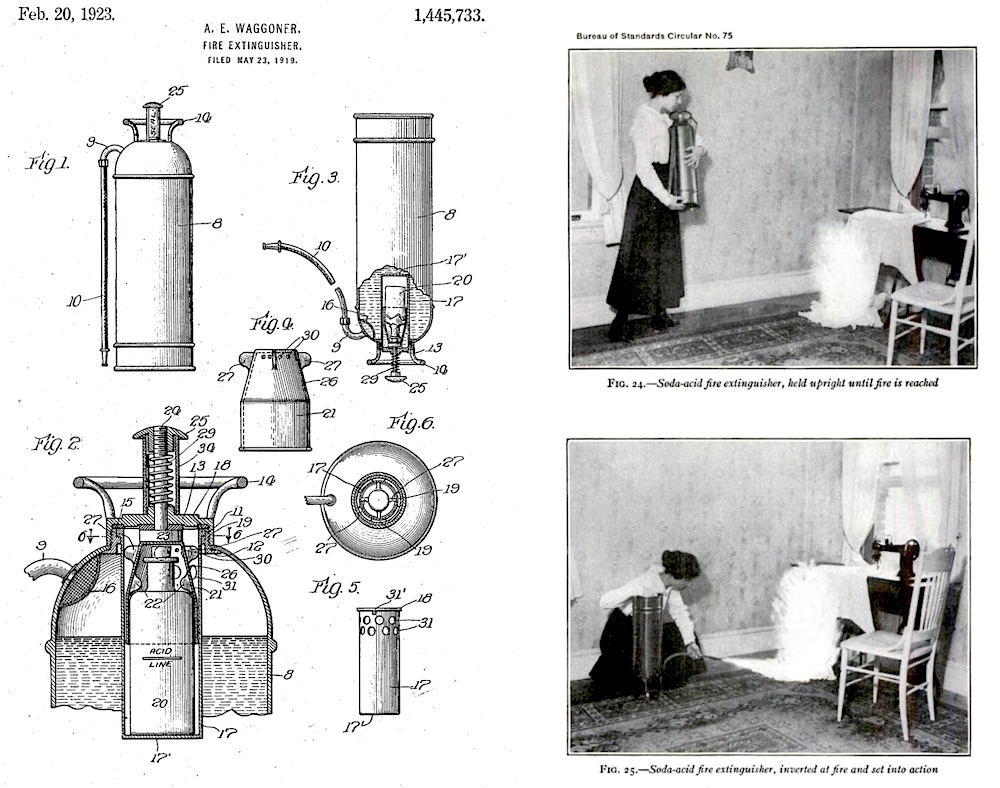

The artifact in our museum collection is one of the more familiar examples of Diener’s inferno combating technology; a 2.5 gallon “Automatic” soda-acid extinguisher, likely dating from the 1920s. Made from heavy copper and measuring 22” in height by 7” in diameter, this potentially life-saving steampunk apparatus wasn’t necessarily a breeze to wield, but it functioned on some pretty reliable scientific principles.

Soda-acid fire extinguishers like this one were a mainstay in office buildings, schools, and factories for much of the 20th century, and Diener was just one of dozens of manufacturers producing them. The “Automatic” extinguisher would have been referred to in its day as a “tip-over” model, meaning that the user would need to literally turn the cylinder upside down to activate the chemical reaction (bi-carbonate soda + water + sulfuric acid) needed to weaponize the device against a blaze. Once “charged,” carbon dioxide gas pressurizes the water through the canister’s nozzle with a potential spray radius of 20 to 30 feet. The water cools the fire, and the accompanying carbonic acid gas helps squelch it. Without turning this into too much of a 7th grade chemistry lesson, the equation supposedly looks like this:

2NaHCO3 + H2SO4——–> Na2SO4 + 2H2O + 2CO2

[Left: A 1923 soda acid extinguisher patent granted to Albert E. Waggoner and assigned to the Diener MFG Co. Right: A woman showing how to correctly invert a soda acid extinguisher before use, 1919. Here are the specific “Directions for Charging” embossed on our Diener extinguisher: Put 1-1/2 LBS bi-carbonate of soda in machine, fill with water to mark on inside, stir well, fill bottle to acid line with sulphuric acid (4 fluid ounces), replace in cage with lead stopple in bottle. Screw cap down tight. Discharge and recharge once a year. Record date on card attached. Clean thorough whenever used. Protect from frost.]

There were some potential pitfalls with these extinguishers, of course. They weren’t great at combating oil, chemical, or electrical fires (a relatively new type of catastrophe at the time), and the convenience of the tip-over activation could also prove quite the annoyance if you turned the canister inadvertently, considering there was no shut-off function once the chemical reaction started. Extinguishers that were used for small fires were often hung right back on the wall, too, making them useless duds for the next emergency.

A Diener engineer named Albert E. Waggoner came up with a solution to this in the early 1920s, patenting an indicator that would alert users as to whether the extinguisher was still activated. That indicator could be added on to existing extinguishers, extending their usefulness. While it doesn’t look like our artifact had an indicator, we do know that it was in use and tested regularly all the way into the early 1970s! A sticker on the side of the unit reveals it was last tested by a company in Elmwood, Indiana, during that period. That’s about 50 years of service as a fire extinguisher, earning it a well earned retirement as an “upcycled” lamp. Don’t worry, we’re pretty sure all the chemicals were removed before it was wired into a light fixture. After all, if we started a fire with a converted fire extinguisher lamp, that would be far too much irony to combat with any modern equipment.

History of Geo. W. Diener MFG Co., Part I: Starting Fires

George (b. 1876) and Herman Diener (b. 1879) were Chicago natives, born during the city’s rebirth from the Great Fire of 1871, which inspired no shortage of fire safety innovations in its own right. They were the children of German immigrants—Gustav and Margaretha Diener—who’d been part of the city’s renaissance in their own humble way.

Settling in the Pilsen neighborhood, Gustav worked for many years as a stone cutter (alongside his brother Traugott Diener), while Margaretha cared for their seven children. Tragically, the two eldest kids, Margaretha Anna (named after her mom) and Gustav (named after his dad), both died in their teenage years—each of them killed by speeding trains in bizarre, separate accidents in 1889 and 1890. George and Herman were coming of age during this same period, so the loss of their older siblings would have been particularly devastating.

Settling in the Pilsen neighborhood, Gustav worked for many years as a stone cutter (alongside his brother Traugott Diener), while Margaretha cared for their seven children. Tragically, the two eldest kids, Margaretha Anna (named after her mom) and Gustav (named after his dad), both died in their teenage years—each of them killed by speeding trains in bizarre, separate accidents in 1889 and 1890. George and Herman were coming of age during this same period, so the loss of their older siblings would have been particularly devastating.

It’s possible that these childhood tragedies could have inspired the Diener brothers to eventually make products for preventing disasters, but that might be a stretch. While George and Herman both took safety seriously enough to live into their 90s, their early forays into manufacturing actually focused more on tools for creating blazes, rather than putting them out.

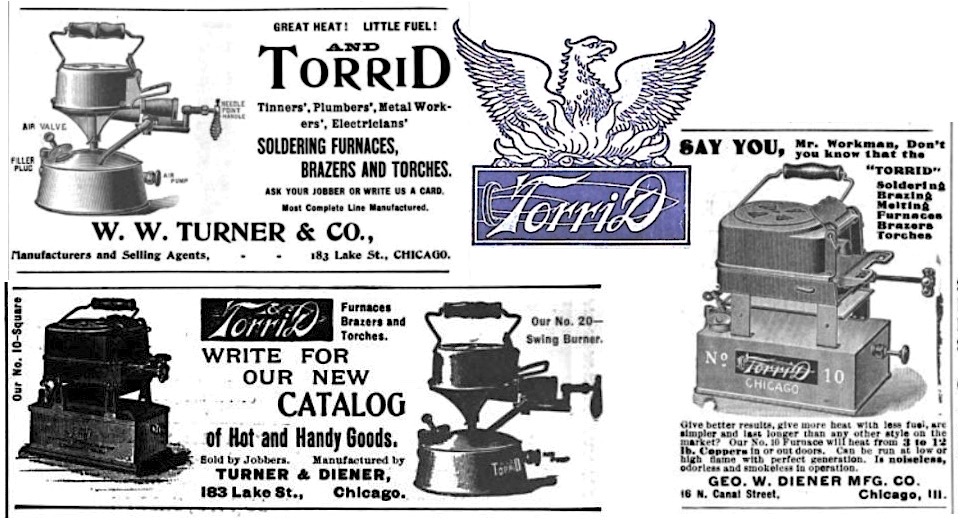

The foundations of the Diener business trace back to a Chicago hardware maker known as W. W. Turner & Co., 183 Lake Street, with whom George Diener formed some sort of partnership around 1899, at just 23 years of age. Turner & Co. was a smalltime operation; they made a lot of the same sort of gas appliances as the well-known Turner Brass Works, but as best we can tell, there was no connection between the two. In fact, this particular Mr. Turner seemed eager to become a footnote in the field, as he sold his entire interest in the upstart firm to George Diener by 1901. In the span of two years, W. W. Turner & Co. had become “Turner & Diener,” and finally the “George W. Diener Manufacturing Company.”

[The rapid evolution of a company name . . . Top Left: 1899 ad for W. W. Turner & Co. Bottom Left: 1900 ad for Turner & Diener. Right: 1902 ad for Geo. W. Diener MFG Co. Each ad features the company’s “Torrid” line of soldering furnaces, brazers and torches.]

At the time of the ownership change, a trade journal called The Metal Worker reported that the newly re-named Diener firm was also moving to a new address at 74-76 Lake Street, “where they have secured double their former space.

“The company manufacture metal and hardware specialties, among which are the Torrid Furnaces for sheet metal workers, pattern makers, tinners, plumbers, etc., Blast Brazers for bicycle and automobile brazing, forging, etc., and Blast Torches for melting, brazing and burning.”

The “Torrid” line of torches and furnaces would remain Diener’s best known brand for its first two decades in business.

In May of 1907, with 28 year-old Herman Diener now onboard as V.P., the Geo. W. Diener MFG Co. was officially incorporated with a capital stock of $50,000. Interestingly, this occurred just a week after the death of steel magnate Orrin W. Potter—the husband of George’s mother-in-law Elizabeth C. Potter—so it’s possible there was an influx of financial aid from the deceased’s estate. In any case, the company catalog that year included loads of tradesman’s tools: bricklayers’ hammers, pipe benders, tinners’ chisels, etc., as well as various iron cans, pots, tanks, and “salamanders” for holding potentially hazardous materials. Among the few items related to fire fighting was a “Geyser” Hand Fire Pump; “same style pump as is used by the Chicago Fire Department,” the catalog claimed.

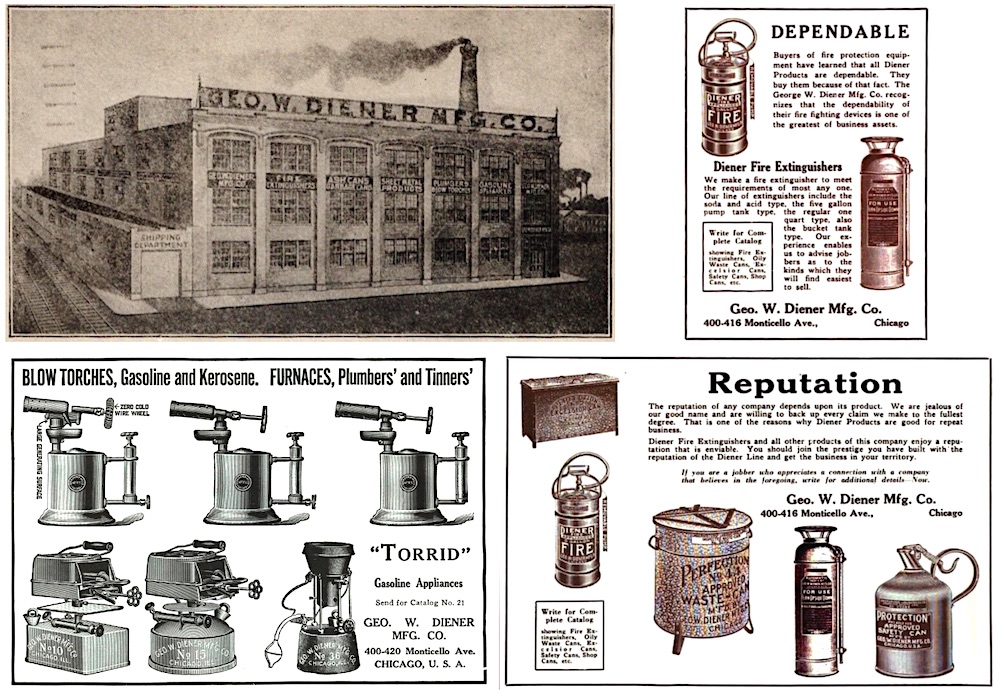

It wasn’t until around 1914 or 1915, after the company had settled into its brand new three-story brick factory at 400-416 Monticello Avenue, that the first Diener hand extinguishers start to show up, with a gradual increase in product diversity after World War I.

“We make a fire extinguisher to meet the requirements of most any one,” read an ad in 1921. “Our line of extinguishers include the soda and acid type, the five gallon pump tank type, the regular one quart type, also the bucket tank type. . . . Buyers of fire protection equipment have learned that all Diener Products are dependable. They buy them because of that fact.”

By the late 1920s, the Diener brothers’ little sheet metal business had given them a pretty good approximation of the American Dream, as each of them owned fine homes in Oak Park with their respective families. They weren’t spring chickens anymore, however, and the next chapter of their business would largely be defined by two unforeseen, outside forces. One was the Great Depression; the other was a memorable young Cajun raconteur named Lodias J. Dugas.

Part II. The Diener-Dugas Fire Extinguisher Corp.

In 1927, a major new development in fire fighting technology was introduced from an unlikely source—a 28 year-old dry cleaning attendant with a third-grade education. Lodias J. Dugas (pronounced in the French “du-gah”) was a resident of the small town of St. Martinville, Louisiana, but he was no humble Southern gent. Known for wearing colorful clothes, smoking cigars, and telling tall tales, he was also the sort of fun-loving fellow who would conduct random barnyard chemistry experiments as a form of entertainment, likely in hopes of watching something blow up. On one such occasion, though, he and two friends got more than they bargained for, as their combination of bicarbonate soda with a unique chemical cocktail accidentally led to the creation of a new “dry chemical extinguisher”—a type far better equipped to fight gas and electrical fires.

“Not having any real scientific background, the men weren’t quite sure what they’d found,” the Daily Advertiser—a newspaper in Lafayette, Louisiana—reported in a feature on Dugas, published decades later in 1980. “But [Dugas] knew he’d found something. He’d observed a unique chemical reaction and felt at least partially certain that if put under pressure, the mixture could be worth something. . . . With the confidence that never seemed to desert him, Dugas packed his bags and headed alone to Chicago’s Underwriters Laboratories.”

“Not having any real scientific background, the men weren’t quite sure what they’d found,” the Daily Advertiser—a newspaper in Lafayette, Louisiana—reported in a feature on Dugas, published decades later in 1980. “But [Dugas] knew he’d found something. He’d observed a unique chemical reaction and felt at least partially certain that if put under pressure, the mixture could be worth something. . . . With the confidence that never seemed to desert him, Dugas packed his bags and headed alone to Chicago’s Underwriters Laboratories.”

In the Daily Advertiser story, an 80 year-old Dugas recalled that his two friends —the co-discoverers of the extinguisher—had opted to stay in St. Martinville, and that “their whereabouts to this day, he wasn’t quite clear on.” The weird part is that Dugas remembered their names as Leo Tendourban and George Deaner. . . . Maybe, by coincidence, there really was another fellow named George Deaner (albeit spelled a tad differently) that Dugas knew just before coming to work with George Diener in Chicago. Or maybe, in his old age, Dugas’s memories had gotten a tad mixed up.

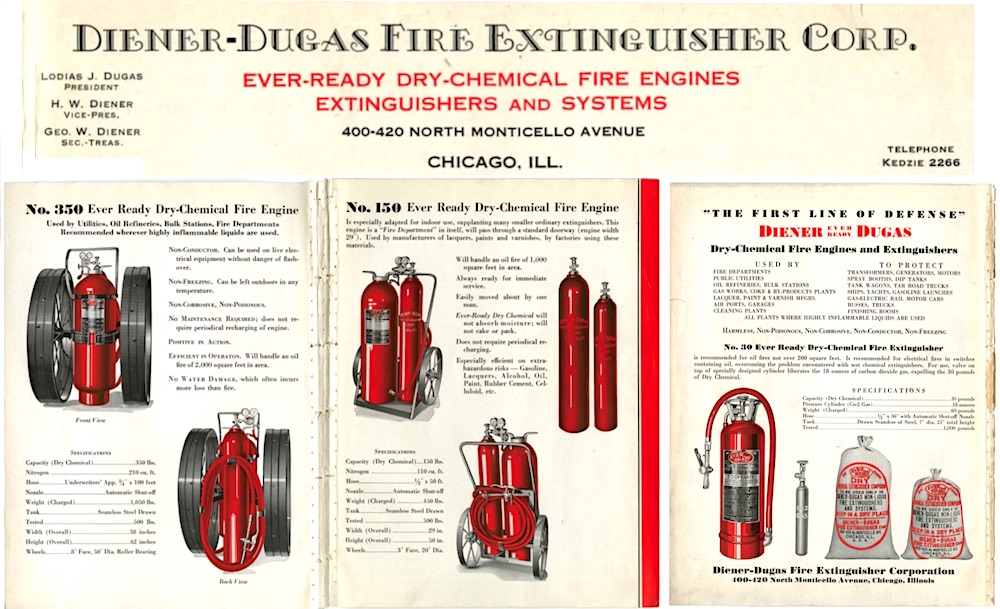

Either way, within a few years of his arrival in Chicago, the Cajun entrepreneur known back home as “Big Shot” had officially patented his Dry Chemical DuGas—spelled and pronounced to look more like the French term “du gas,” as in, “two gasses.” As demand increased for the intriguing new device, though, Dugas soon realized he needed a more experienced manufacturing partner to help him out. Enter George Diener.

During this same period, the Diener MFG Co. was suffering under the same financial downturn as most other businesses in the early years of the Depression. The chance to hatch an exclusive partnership with the inventor of the Du-Gas extinguisher seemed like a massive opportunity, and before the ink was even dry, a new name was displayed above the factory on Monticello Avenue: the Diener-Dugas Fire Extinguisher Corp. was born.

[Small catalog put out by the new Diener-Dugas Fire Extinguisher Corp. in 1933/34, likely handed out at the company’s exhibit at World’s Fair “Hall of Science”]

From about 1933 to 1938, Diener-Dugas became the dedicated extinguisher wing of the Diener business, while other hardware still fell under the Geo W. Diener name. Lodias Dugas was listed as the president of the extinguisher division, and he helped coax the Diener brothers into one of their most active commercial periods, starting with a dedicated exhibit space inside the “Hall of Science” at the 1933-34 Chicago World’s Fair.

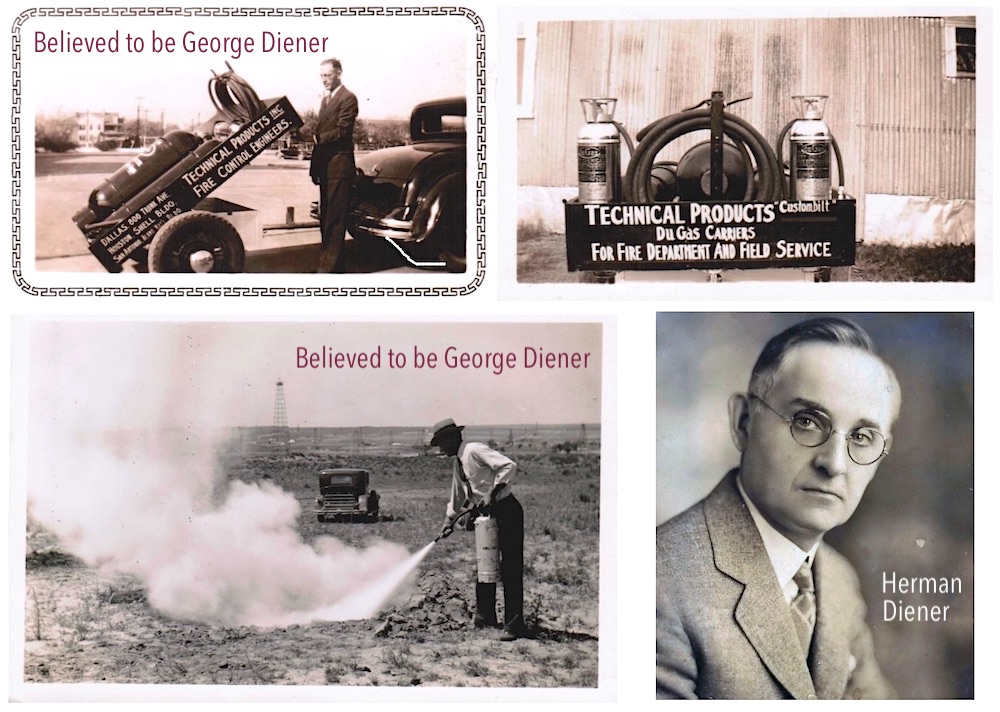

Dugas also took the Dieners out on the road with him, putting on over-the-top sales demonstrations in which they would set simulated blazes and put them out with the DuGas machines.

“It was my best advertising,” Dugas later recalled. “I had to prove how good they were.”

Not every showcase went as well as the next. One article in Business Week noted that, “All too often, after Dugas had got a roaring demonstration blaze going, the dry chemical extinguisher wouldn’t work. Somebody had to call the fire department to put Dugas’s fire out.”

If costly embarrassments didn’t sour George and Herman Diener on the Dugas partnership, the economy might have. It wasn’t cheap to run these high-profile demonstrations, and during the mid ‘30s, the company had become increasingly dependent on aid from Franklin Roosevelt’s National Recovery Administration to stay in business.

In 1935, Herman Diener even wrote a letter to U.S. Senator J. Hamilton Lewis, expressing his wish that the N.R.A. not be discontinued.

“Our industry, the Fire Extinguishing Appliance Manufacturing, before the adoption of its code of fair competition on November 4, 1933, was in a most deplorable condition,” Diener wrote, “a condition that spelled ruin for at least the smaller manufacturing plants such as ours. We have been able to rebuild our business somewhat, only through the help of the National Recovery Administration. In other words, it has been a blessing for our company at least and we believe we are expressing the opinion of many other such factories in our industry.”

Herman essentially pleaded with the senator to keep the N.R.A. in its present form. “We urgently solicit your support in this, a matter of vital importance to us all.”

[The above photos of a fire extinguisher demonstration, provided by Herman Diener’s granddaughter Susan Eifert, are likely from the late 1930s. Susan thinks the man pictured is George W. Diener. Vice President Herman Diener, pictured on the right, was elected as a director of the national Fire Extinguisher Manufacturers Association in the 1940s before retiring from the industry in 1951.]

Unfortunately, the National Recovery Administration was shut down that year, and by 1938, the Diener-Dugas merger was unceremoniously un-merged. Dugas found a new manufacturing partner in the form of the Ansul Corporation of Wisconsin, but Dugas himself bowed out of the game, returning home to collect royalties on his invention and hobnob with the biggest fish of New Iberia, Louisiana. He estimated that he earned $100 million from that single famed patent, and he spent most of it with predictable flamboyance.

Part III. Where a School Once Was is Where a Factory Once Was

Emerging out of this whole whirlwind, the re-focused Geo. W. Diener MFG Co. now had two executives in their 60s and World War II metal rationing to contend with.

We’re not entirely sure how the Diener factory operated during the war, though one would presume that torches and extinguishers would have been deemed defense essentials, keeping the gears turning.

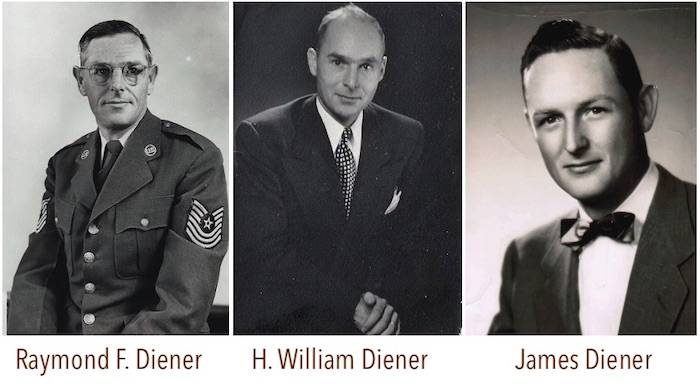

Military records from these years also suggest that Herman’s sons Raymond and H. William Diener were both working for the family business when they went to serve in the war. Both men returned from the conflict (as did younger brother James Diener), but they don’t appear to have taken on roles in the company afterwards. On the other hand, George’s son George W. Diener, Jr. is listed as an executive throughout the 1950s, taking over the vice presidency from his uncle Herman, who retired in 1951. George Sr., meanwhile, continued to preside over the business until his retirement in 1962, at the age of 86.

Military records from these years also suggest that Herman’s sons Raymond and H. William Diener were both working for the family business when they went to serve in the war. Both men returned from the conflict (as did younger brother James Diener), but they don’t appear to have taken on roles in the company afterwards. On the other hand, George’s son George W. Diener, Jr. is listed as an executive throughout the 1950s, taking over the vice presidency from his uncle Herman, who retired in 1951. George Sr., meanwhile, continued to preside over the business until his retirement in 1962, at the age of 86.

According to Cook County title records, the three-story plant at 400-420 N. Monticello Ave. had been sold a year earlier, in 1961, to a developer named Edmund A. Juzwik, ending 50 years of Diener family ownership. Up until 1965, though, listings can still be found for a “Diener Industries, Inc.” operating out of the plant.

The property was ordered sold for “delinquent taxes” in 1967, and after sitting abandoned for several years, was largely gutted by a fire; always a strange fate for a former fire extinguisher factory. Rather than leveling the building, though, the city turned it over to the Chicago Board of Education, which renovated it into the Laura S. Ward Elementary School in 1973.

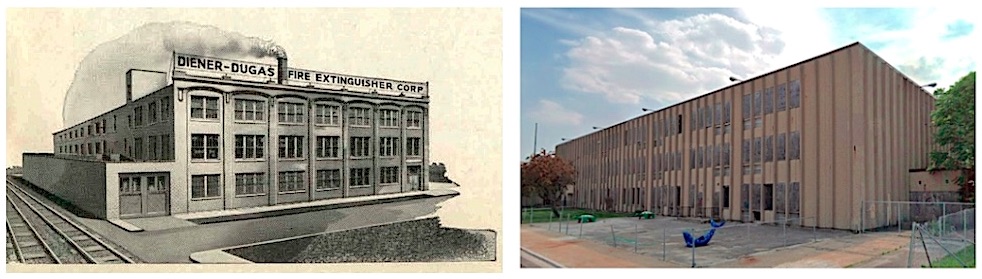

[Then and Now. The Diener factory at 410 N. Monticello Ave. in East Garfield Park, home of the company from 1909-1961. Seen on the left during the Diener-Dugas era in the mid 1930s, and on the right in 2020, seven years after the Ward Elementary School was moved from the location, leaving it boarded up and abandoned.]

During the 1980s, there were rising concerns about cancer cases among teachers at the school, and studies were conducted to determine if leftover hazardous materials from the old Diener factory might be a cause. No such evidence was found, and the school remained in use until budget cuts led to its closure in 2013.

George W. Diener Sr. died in 1968, age 92, and Herman followed in 1971, age 91.

Worth Noting: One of Chicago’s chief fire marshals during the ‘40s and ’50s was also coincidentally named George Diener; no relation.

[Advertising art for Diener’s short-lived Marvel Vacuum Cleaner, circa 1915. The girl in the image is George and Herman’s niece, Margaret Fischer Rast (1905-2000). Photo courtesy of photo courtesy of Margaret’s daughter Gretchen Rast Greiner]

Sources:

“Trade Notes” – The Metal Worker, June 15, 1901

Geo. W. Diener MFG Co. Catalog #7, 1907-08

“Hand Fire Extinguishers” – 5th Annual Report of the State Fire Marshal of the State of Illinois, 1915

“Safety for the Household” – Circular of the Bureau of Standards, 1918

The Science of Everyday Life, by Edgar F. Van Buskirk and Edith Lillian Smith, 1919

Mill Supplies, Vol. XII, No. 5, May 1922

George W. Diener obit – Chicago Tribune, July 10, 1968

Herman W. Diener obit – Chicago Tribune, Feb 25, 1971

“Fire Extinguisher is Dugas’ Claim to Fame” – Daily Advertiser (Lafayette, LA), Oct 12, 1980

“City School Investigated for Cancer Link” – Chicago Tribune, Nov 9, 1986

“School Found Safe, Report Says” – Chicago Tribune, Dec 19, 1986

Archived Reader Comments:

“My Grandfather H.W. Diener was George’s brother & Secretary/Bookkeeper at the business.” —Susan Diener Eifert (Wisconsin), 2020

“I knew George Diener Jr. He would have laughed and enjoyed his fire extinguisher being used as a lamp. He was a joyful friendly person.” —Nick B., 2019

“George Jr was my 2nd cousin, does he have any children? Would love to get in touch! I would love to hear from you!” —Susan Diener Eifert

“I have the number zero 34 torch kerosene oil can made by geo.w diener manufacturing company Chicaco. All brass.” —G. Jemison, 2017

All brass.” —G. Jemison, 2017

Found a 1925 tinner furnace and am struggling to find out more information about what it may be worth. I found several similar but specifically not this one…it’s a torrid # 10 square Pat. Geo.w.diener mfg.co is the only markings on it.. how can I find out more about it..?

Thank you

I have an Geo W Diener Mfg. industrial steel Quick Service Waste Can I am looking to sell. Not sure of value.

Could you tell me the value of this extinguisher is?

We found a torch from the company and made a novelty lamp with it. The workmanship is beautiful. We left the patina.

I have a edge trowel that is cast with G. W. Denier MFG. CO.

Then 10 and

then CHICAGO. I am guessing that 10 is the size. I may have one of their fire extinguishers also.

I found one of these extinguishers in the basement of my great-grandfather’s farmhouse. What would be the approximate value of this fire extinguisher. It is in great shape, no dents, just needs to be cleaned. Still has water in the tank. Thank you.

You do not give soda and acid extinguishers quite enough credit. Invented in 1868 they were the first extinguisher that when activated, by simply turning upside down, would produce a fire fighting stream that traveled some 30 feet. They were simple, reliable and could be operated by the normal person. Certainly they has some drawbacks but there was nothing else that performed so well and they were used until about 1969 when they began to be taken out of service on their recharge date. Todays extinguishers require service every year but many do not get it. And, as you might imagine, when needed do not work.

Thanks for the Geo. W. Diener info.

I am in procession of a Geo W. Diener copper extinguisher still in its original state. I’ve had it since 1981′ as an

ex-florida firefighter. I’m inquiring to have it acquisitioned, preferably by a Diener family member.

Best way to reach me is by text @

407- 484- 1763.