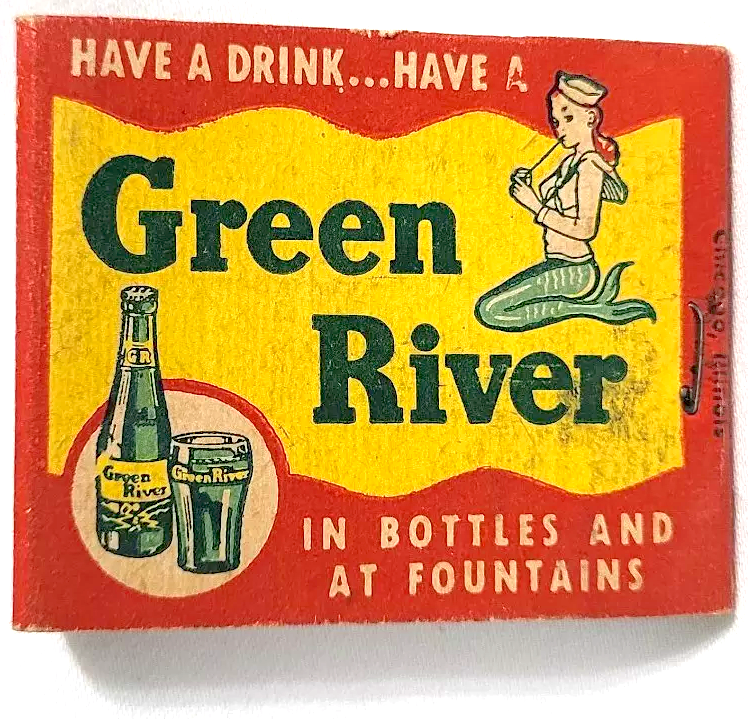

Museum Artifact: Green River Soda Pop Carton with 6 Bottles, c. 1950s

Made By: Green River Corporation / Sethness-Greenleaf, Inc., 4554 N. Broadway, Chicago, IL [Uptown]

“Have a drink, have a drink, have a drink, have a GREEN RIVER / Delicious, different, goodness knows! / Green River, where refreshment flows / Have a drink, have a drink, have a drink, have a GREEN RIVER!” —advertising jingle, 1940s

Green River is many things—a soft drink, a syrup, a hit song (two of them, in fact), a brand, a business, and arguably America’s first lime-flavored soda pop of consequence; pre-dating 7-Up (1929), Mountain Dew (1948), and Sprite (1961) by no small margin. One thing Green River is not, however—contrary to popular belief—is an homage to the emerald hue of the Chicago River on St. Paddy’s Day. . . . Or at least, it wasn’t originally intended as such.

First developed in 1916 by Iowa confectioner Richard C. Jones, this rather distinctive carbonated beverage actually got its name more than four decades before Chicago’s river dyeing tradition had even begun. The branding choice was likely pilfered from a popular liquor of the same era, Green River Whiskey, which was distilled along the banks of the Ohio River in Owensboro, Kentucky. In the official corporate story, though, a wide-eyed school boy came up with the name after marveling at how the new lime drink looked pouring out of a soda fountain: a bright green river of “the most refreshing thirst quencher you’ve ever tasted,” as one early ad put it.

Without good old Prohibition, Green River pop might never have been produced in Chicago at all. Fortunately, once it did arrive on the scene in the 1920s, it was swiftly adopted by the locals, well on its way to joining the shortlist of definitive Chicago consumables—a perfect pairing with your Lou Malnati’s deep dish, Vienna Beef, or Garrett’s Popcorn.

Green River is, admittedly, not quite so readily available these days as it was in the 1950s, when it supposedly outsold ever soda besides Coke in some parts of the Midwest. But its local legend is still substantial, retroactively amplified by the fact that one of its many parent companies of the past—Sethness-Greenleaf, Inc.—also supplied the vegetable dye that helped turn the aforementioned greening of the Chicago River into a sustainable, beloved event. Green River, whether by direct or indirect consequence, has since become the de facto pop of a proper Chicago St. Paddy’s.

History of Green River Soda, Part I: “Green River Jones”

The origin story of Green River soda is conveniently preserved in several newspaper articles from the late 1910s. I say “conveniently,” because a closer inspection of these stories suggests that most of them were part of a calculated promotional campaign during Green River’s initial launch into a wider market in 1919. The division between actual news and paid advertisements wasn’t always exceedingly obvious at the time—nor is it today, for that matter—so we’re left to take this “official” tale of Green River with perhaps a few grains of additive salt.

“Once upon a time in a small town somewhere in Iowa,” began one such ad/article in a 1919 issue of the Daily Illini, “there was a store—just a plain candy store with a soda fountain. This store was owned by a kindly man named Jones, R. C. Jones. True there is nothing remarkable about the fact, and his name might have been Brown or Smith, but: Jones was different. He had a kindly interest in the people who came in to buy his wares.

“Once upon a time in a small town somewhere in Iowa,” began one such ad/article in a 1919 issue of the Daily Illini, “there was a store—just a plain candy store with a soda fountain. This store was owned by a kindly man named Jones, R. C. Jones. True there is nothing remarkable about the fact, and his name might have been Brown or Smith, but: Jones was different. He had a kindly interest in the people who came in to buy his wares.

“For years he had heard—’Mr. Jones, I want a nice cool drink, I don’t know what—something with the same bubbling snappyness of Champagne.’ Mr. Jones made many suggestions but it was always useless—’too sweet,’ ‘too sour,’ ‘too flat,’ ‘too something or other.’ Mr. Jones knew from these remarks by his friends that the right drink was not yet on sale. He knew what they wanted, but how to get it was the question.”

Of course, the story then walks us through Richard Jones’s many late nights toiling away in the backroom of his candy shop, performing chemical experiments like a mad scientist, desperately seeking the ideal thirst quencher, until at long last “he hit it!”

“Jones found THE DRINK. He had filled the void—found a drink that had the snap of champagne, the tartness of the lime; a delicious cooling, bubbling beverage that made an instantaneous hit with all who tried it.

“Snub-nosed kids, bewhiskered old granddads, giggling girls, and sedate businessmen of financial force and position—every age, size, and shape of person from the rag-picker to the president; no matter what their other notions; no matter what they thought about the peace treaty or the League of Nations; freeing Ireland or the disposition of Shantung—regardless of all other differences they agreed on the merit of GREEN RIVER . . . the soft drink triumph of the age.”

You’re not likely to find a better hyperbolic rant about soda pop at any other point in the Woodrow Wilson administration. For those also interested in historic accuracy, though, there are at least a few less ridiculous news clippings from this period that offer a bit more grounded evidence for the story of Richard C. Jones and his little sweet shop in Davenport, Iowa.

Davenport’s own newspaper, for example, the Daily Times, published an article in May of 1919, in which Jones is reported to have met “with representatives of a Chicago soft drink firm” about sharing the formula for his popular new pop. The same story suggests that Jones would be re-branding his beverage as Green Rivver, with two “V’s, in order to distinguish it from the already well-known Green River Whiskey; a drink destined for the gallows with Prohibition set to go into effect the following year.

Davenport’s own newspaper, for example, the Daily Times, published an article in May of 1919, in which Jones is reported to have met “with representatives of a Chicago soft drink firm” about sharing the formula for his popular new pop. The same story suggests that Jones would be re-branding his beverage as Green Rivver, with two “V’s, in order to distinguish it from the already well-known Green River Whiskey; a drink destined for the gallows with Prohibition set to go into effect the following year.

Clearly, the double-V plan was subsequently scrapped, as the new soft drink would be launched under the Green River name, one V, a few months later in the summer of 1919, now under license to Chicago’s Schoenhofen Brewing Company. The Davenport newspaper reported that Schoenhofen had offered R. C. Jones “5,000 cash and a royalty on every drink of Green River that is sold in the next 99 years,” but Jones would claim years later that he’d been given a one-time payment of $100,000 for the recipe; a fortune he would ultimately squander entirely after bad investments went belly-up in the stock market crash of 1929. By 1938, Jones had filed for bankruptcy. He died in 1959 in Clinton, Iowa, at the age of 75.

As recently as 1989, it’s worth noting, Jones’s daughter Betty Jones Ridgely was still substantiating her father’s claim to the Green River formula, writing to the Chicago Tribune that year to confirm the story, and noting that Richard had been known for most of his later life as “Green River Jones.”

II. The Schoenhofen Must Go On

“The Schoenhofen Company introduced Green River in Chicago. In less than eight weeks practically every soda fountain in the Windy City was selling Green River. At first druggists ordered a gallon or two. Then the demand grew, till they couldn’t get it fast enough.” —promotional article in the Moline Daily Dispatch, October 1919

The Schoenhofen Brewing Company was one of Chicago’s most esteemed and financially successful pre-Prohibition breweries, best known for its nationally popular Edelweiss beer. The company has its own dedicated page in the Made In Chicago Museum for a reason, as its late 19th century rise to prominence—and the development of its massive facilities in Pilsen—represent the pinnacle of Chicago’s role in the German-American beer boom. Schoenhofen’s entrance into the Green River story, meanwhile, is more of a complicated side tangent.

The Schoenhofen Brewing Company was one of Chicago’s most esteemed and financially successful pre-Prohibition breweries, best known for its nationally popular Edelweiss beer. The company has its own dedicated page in the Made In Chicago Museum for a reason, as its late 19th century rise to prominence—and the development of its massive facilities in Pilsen—represent the pinnacle of Chicago’s role in the German-American beer boom. Schoenhofen’s entrance into the Green River story, meanwhile, is more of a complicated side tangent.

After 50 years of steady profitability, Schoenhofen was dealt the ultimate double-blow between 1917 and 1919. First, as part of the “Trading with the Enemy Act” during World War I, the U.S. government had temporarily seized most of the brewery’s assets, citing the Schoenhofen family’s supposedly friendly ties to Germany. Then, in January of 1919, the 18th amendment was ratified, ushering in the age of Prohibition—a death warrant for America’s entire brewing industry.

Schoenhofen’s president, Peter S. Theurer, was left with little choice but to follow the same desperate game plan as many other brewery owners: to stay afloat by replacing his beer with non-alcoholic alternatives. Some tried to re-create the actual taste of the illegal product in a legal formula—aka “near beer”—but getting into the soda business was an equally viable option . . . which is what led Theurer’s soda scouts to the Davenport doorstep of Richard C. Jones.

Once a deal was struck, little time was wasted getting the bottled version of Jones’s Green River drink rolling out of Schoenhofen’s Chicago plant before Prohibition went into effect in January of 1920.

[Forced to stop selling its popular Edelweiss beer during Prohibition, Chicago’s Schoenhofen Brewery purchased the Green River soda formula and began producing it from their plant at 18th Street and Canalport Avenue in the Pilsen neighborhood]

“It’s here, in bottles, with the same delicious tart, snappy flavor that made it popular at soda fountains,” proclaimed one of Schoenhofen’s earliest Green River newspaper ads. “And that cool, refreshing trickle all the way down the dusty throat—on a hot afternoon; after tennis or other sports; on motor trips; between dances; on warm summer evenings. Any time–all the time–as a delightful home beverage.”

With its Edelweiss ad campaigns abruptly concluded, Schoenhofen put all its advertising budget behind Green River and established distribution deals with various bottlers across the country, leading to immediate happy returns even as the dark cloud of Prohibition became a reality. A 1920 issue of Sales Management magazine singled out Schoenhofen as one of the big breweries that was handling the new law with cleverness and class. “In Chicago, Schoenhofen is putting ‘Green River’ over in a big way, and it is quite probable that in time the sales on this beverage will outdistance the sales on its once famous ‘Edelweiss’ beer.”

Arguably the most impactful form of marketing that Schoenhafen got in that first year was a melodic stamp of approval from one of the most popular singers in the country, Eddie Cantor, who collaborated with another successful songwriting duo, Van and Schenck, on an ode to the new soft drink. “Green River” was a jaunty vaudevillian tune, with Cantor unfortunately singing in the minstrel show style. It is very much of its time, which is maybe the best that can be said about it.

Since the country’s turned prohibition,

Since the country’s turned prohibition,

I’ve been in a bad condition

Ev’ry soft drink that I try

Just makes we want to cry

Take it back from whence it came

all your drinks are much the same,

I tried one here today and believe me when I say;

[chorus]

For a drink that’s fine without a “kick”

Oh! “Green River,”

It’s the only drink that does the trick,

just “Green River.”

Has others beat a mile,

makes drinking worth while

And if you want to wear a little smile

try “Green River,”

If your girl gives you the sack

try “Green River”

You will surely win her back,

it’s grand, now understand

That rich man, poor man, beggar man,

That rich man, poor man, beggar man,

thief, doctor, lawyer, Indian chief,

Once they drink it they all think it

the best drink in the land.

When the cannons stopp’d their thund’ring

ev’rybody started wondring

How the treaty would be signed

that was on our mind

Wilson soon forgot his “wil son,”

Haig forgot his “Haig and Haig,”

Foch said “No more Rhine-wine,”

listen boys, before we sign.

[repeat chorus]

Of course, not every aspect of Green River’s Roaring ’20s rollout went smoothly. As more experienced veterans of the soft drink business were already well aware, it was hard enough to come up with a unique and popular soda flavoring, but even harder to prevent others from copying it and selling “imposters” at their soda fountains. Peter Theurer was getting increasingly vexed by this situation by 1925, and wrote about the subject that year in Printer’s Ink magazine.

“We sell Green River in concentrate or syrup form to bottlers, to soda fountains, and similar places where refreshing drinks are served,” Theurer wrote. “In the last few years, we have spent more than $1,000,000 advertising the name and quality of our product and cultivating a consumer demand for it. This has resulted in a profitable business for us. Unfortunately, it has also resulted in the appearance of a number of other beverages colored like Green River and imitating its flavor.

“. . . A year ago we knew that several substitutes for Green River were being sold by manufacturers and jobbers to dealers and by dealers to the consuming public. However, we had no accurate information as to the extent of this. We investigated 1,500 cases. And we found 850 infringers! That seems hardly credible, but it is the truth. In Chicago alone there were between 300 and 400 infringers. Further investigation in a dozen different states convinced us that from 30 to 40 per cent of the beverage served when Green River was ordered was not genuine. And that, any business executive will agree, was an intolerable situation. We had to fight it and master it or it would master us.”

Interestingly, Theurer’s displeasure didn’t lead him into a vengeful deluge of lawsuits. His advice to other business owners was, instead, to kill them with kindness.

“What course do we follow once we have obtained evidence against someone who is infringing us? I can answer that question by saying simply that we are not in business to make enemies but to sell merchandise. Many times it would give us some satisfaction to prosecute an infringer, but in the end we would be no better off. If, by being lenient, we can convert a guilty manufacturer or dealer and, in showing him the folly of his ways, make a customer out of him, both of us profit.”

III. Damming the River

The Schoenhofen Brewery had adopted Green River and cared for it like a child of its own during Prohibition. Unfortunately, by the time Green River reached its adolescence, Prohibition was officially repealed, and Schoenhofen—now under the big tent ownership of the National Brewing Company—poured all of its energies toward a reunion with its own blood kin, Edelweiss Beer.

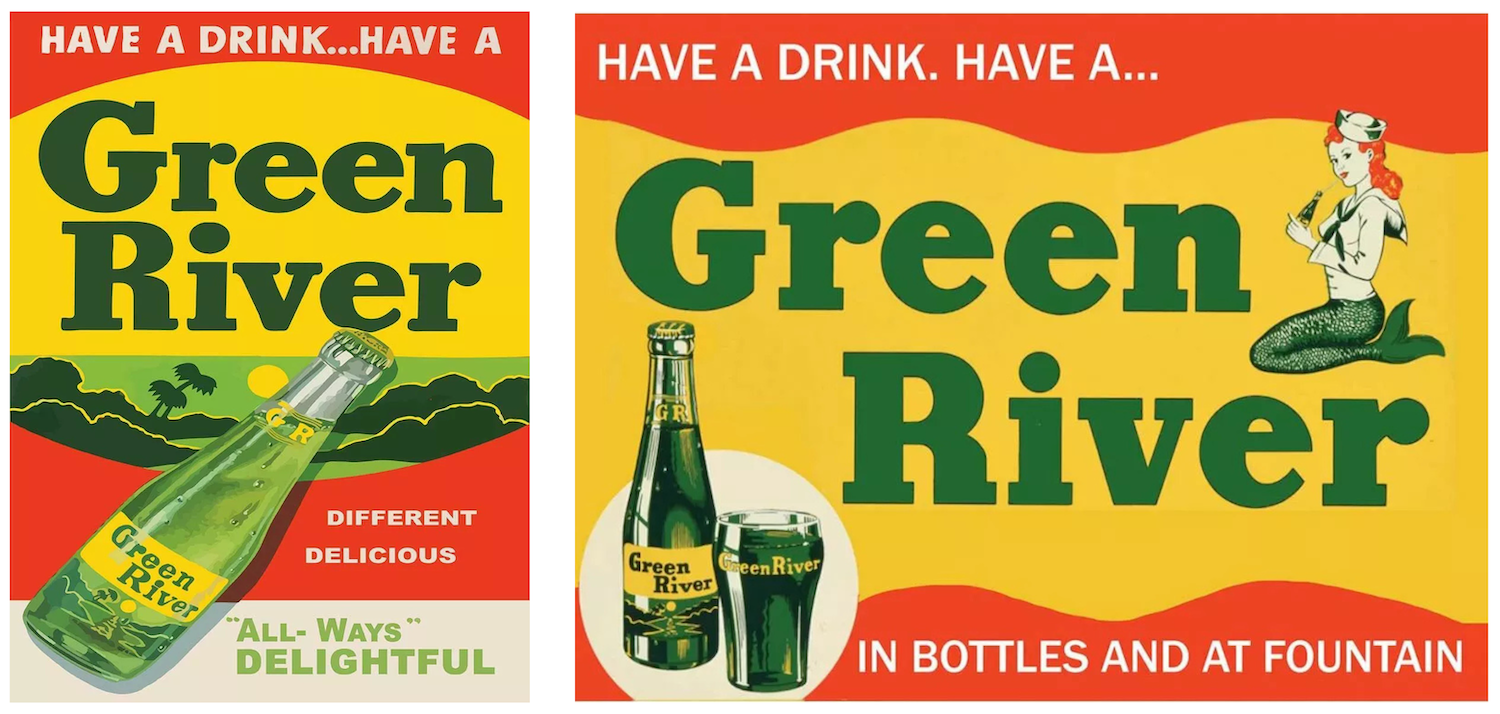

Green River was still popular during the years of the Depression and World War II, and it was promoted with a few iconic “pin-up” style ads and a long-running radio jingle penned by Chicago jinglesmith Wag Wagner: “Have a drink, have a drink, have a drink, have a Green River!” The overall marketing budget for the soft drink was increasingly slashed, however, as Schoenhofen’s management (which no longer included Peter Theurer, who had died suddenly, aged 48, in 1931) was content to let its reputation do the work. There was certainly no concern of competing in any serious way with the likes of Coca Cola, nor about holding off the threat of new citrus-flavored pops entering the marketplace.

Green River was still popular during the years of the Depression and World War II, and it was promoted with a few iconic “pin-up” style ads and a long-running radio jingle penned by Chicago jinglesmith Wag Wagner: “Have a drink, have a drink, have a drink, have a Green River!” The overall marketing budget for the soft drink was increasingly slashed, however, as Schoenhofen’s management (which no longer included Peter Theurer, who had died suddenly, aged 48, in 1931) was content to let its reputation do the work. There was certainly no concern of competing in any serious way with the likes of Coca Cola, nor about holding off the threat of new citrus-flavored pops entering the marketplace.

Things didn’t really change until the early 1950s, when Schoenhafen merged with the Atlas Brewing Co., leading to the closure of the Schoenhofen factory and eventual demise of the Edelweiss brand. Left in the lurch was the Green River formula, which was acquired in 1953 by two veterans of the Chicago beverage industry: Ed Pinkert (of the National Orange Products Co., maker of syrups and concentrates) and Olin Sethness (of the C. O. and W. D. Sethness Co., makers of flavors and extracts). The cost, according to one report, was a mere $7,500.

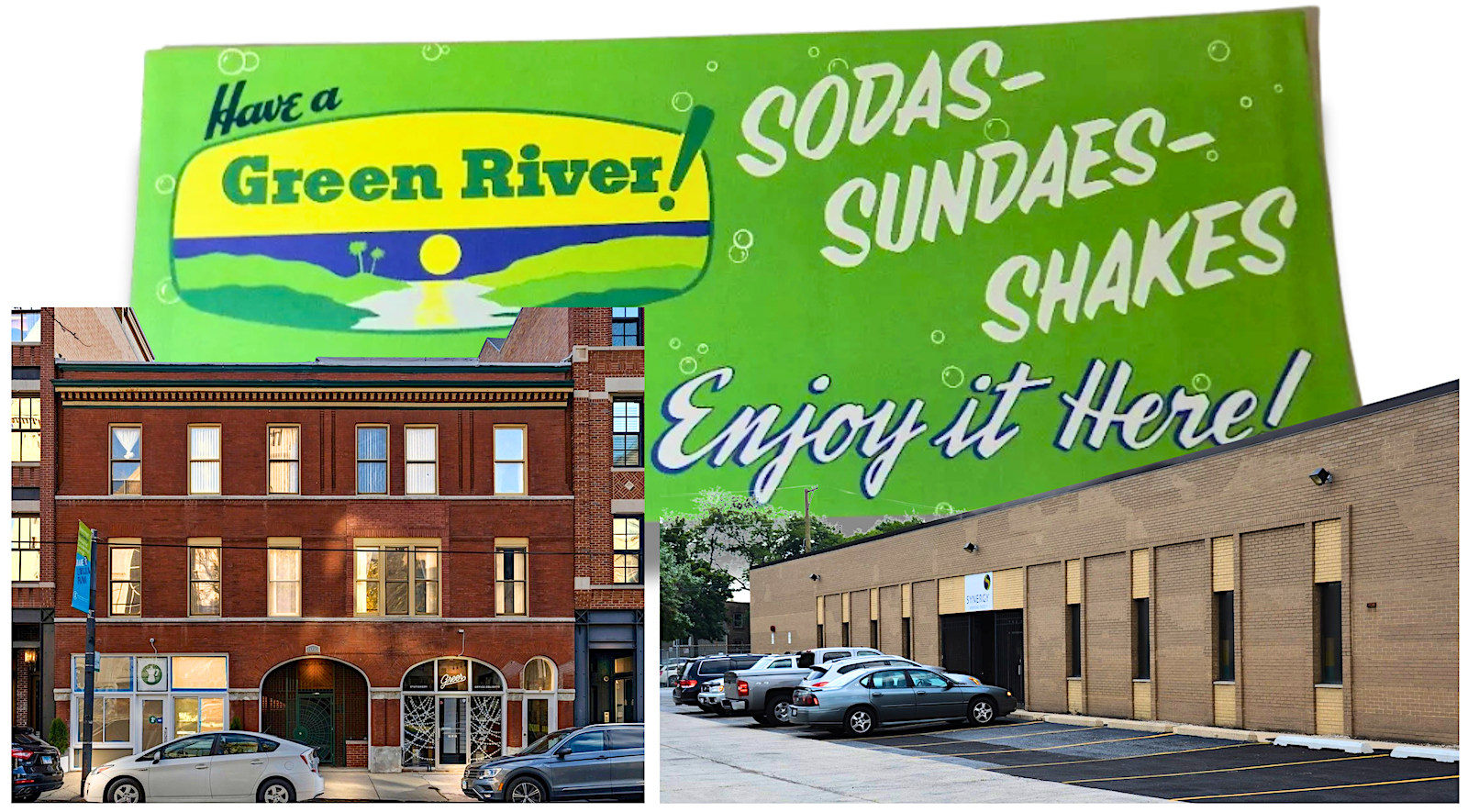

With Pinkert as president, Sethness as vice president, and Charles McQuade as production manager, a new entity known as the Green River Corporation was born, with a factory headquarters at 1926 W. 18th Street, about two miles west of the old Schoenhofen plant. The company’s home offices would later be established in the McJunkin Building at 4554 North Broadway in Uptown.

[New ownership takes over Green River in 1953. Top center photo includes, from left, production manager Charles McQuade, president Ed Pinkert (cast in shadow), and VP/GM Olin Sethness. Below Right is the McJunkin Building at 4554 N. Broadway in Uptown; Green River Corp’s headquarters during the 1950s and ’60s]

“For the first time in almost 15 years,” the National Bottlers’ Gazette reported in October of ‘53,

“Green River is again being given active and aggressive promotion in the bottling field.”

With additional syrup manufacturing set up in Seattle and Los Angeles, and a major recruitment campaign for new bottling partners across the country, the new era of Green River got off to a flying start.

“Green River is rolling,” read a 1953 ad in a bottling trade magazine. “A Delicious Drink when Mom was a girl—Green River has been rolling up consumer demand ever since. Green River carried its own consistent growth on flavor and consumer liking through more than 15 years without a supporting merchandising effort. This unprecedented accomplishment set the stage for NOW! More than 50 bottlers signed up and put Green River to work for them in less than five months of 1953. Now Green River is really rolling. Under new, experienced beverage management, with sound merchandising tools, Green River is rolling in new volume and new profits for more than 50 new Green River bottlers. More bottlers are getting into the Green River profit stream every week.”

“Green River is rolling,” read a 1953 ad in a bottling trade magazine. “A Delicious Drink when Mom was a girl—Green River has been rolling up consumer demand ever since. Green River carried its own consistent growth on flavor and consumer liking through more than 15 years without a supporting merchandising effort. This unprecedented accomplishment set the stage for NOW! More than 50 bottlers signed up and put Green River to work for them in less than five months of 1953. Now Green River is really rolling. Under new, experienced beverage management, with sound merchandising tools, Green River is rolling in new volume and new profits for more than 50 new Green River bottlers. More bottlers are getting into the Green River profit stream every week.”

By this point, 7-Up and Mountain Dew (the latter of which was also named after an old term for whiskey) were now strong competitors in the market. And while soda fountains remained a familiar part of American society in the ’50s and ’60s (Green River was often promoted as a base ingredient for floats, sundaes, and popsicles), people were also increasingly buying their soft drinks in vending machines or in six-pack cases to bring home and store in the fridge.

By the latter half of the 1960s, with the Coca-Cola-owned Sprite now grabbing its own substantial piece of that pie, Green River once again slumped in sales, unable to keep up with the distribution power of its much larger rivals. At the end of the decade, Olin Sethness—who still owned the Green River syrup formula through his company Sethness-Greenleaf—agreed to sell his flavoring business to one of his own salesman, 29 year-old J. Barry McRaith, along with McRaith’s investment partner Pat Kearney. The young duo took over operations of the Sethness-Greenleaf Co. at Webster and Sheffield in Lincoln Park and quickly went to work trying to restore, yet again, the glory days of Green River.

[The six-bottle case of Green River from our museum collection features the soft drink’s iconic 1950s branding, including the short-lived mermaid sailor girl logo on the box]

IV. Live Free or Dye

In 1969, the same year that McRaith and Kearney took over the soft drink brand, Green River randomly inspired its second popular song, as Creedence Clearwater Revival scored a No. 2 hit with “Green River,” from the album of the same name. CCR frontman John Fogerty later explained that the track was based on memories of growing up on the banks of Putah Creek in northern California, but that the title had a very specific backstory. “Right up the street from where I lived was a pharmacy that had a soda fountain. And one of the drinks they would make for you was a Green River. And I stared at the label on that bottle of syrup when I was around eight years old and I said, ‘I’m gonna save that. That’s important.'”

Unfortunately, this latest collaboration between the Chicago pop and the pop charts didn’t lead to the same sort of upsurge in the drink’s popularity as Eddie Cantor’s 1920 ditty had. To their credit, though, Barry McRaith and the Sethness-Greenleaf Co. remained proud stewards of the Green River brand through the ‘70s and ‘80s, ensuring that its legacy was maintained and that it was on the menu at most of McRaith’s favorite Chicago restaurants; if few other places. Sethness-Greenleaf didn’t have the industry might to battle Sprite, Mountain Dew, or the other new lemon-lime sodas on the rise, but their recognition of Green River’s growing nostalgia value was vitally important—as was the company’s corresponding role in a new Chicago tradition.

Unfortunately, this latest collaboration between the Chicago pop and the pop charts didn’t lead to the same sort of upsurge in the drink’s popularity as Eddie Cantor’s 1920 ditty had. To their credit, though, Barry McRaith and the Sethness-Greenleaf Co. remained proud stewards of the Green River brand through the ‘70s and ‘80s, ensuring that its legacy was maintained and that it was on the menu at most of McRaith’s favorite Chicago restaurants; if few other places. Sethness-Greenleaf didn’t have the industry might to battle Sprite, Mountain Dew, or the other new lemon-lime sodas on the rise, but their recognition of Green River’s growing nostalgia value was vitally important—as was the company’s corresponding role in a new Chicago tradition.

Famously, adding green dye to the Chicago River began in the early 1960s as part of a practical effort by the Chicago Plumbers Union to identify the sources of pollutants in the river. The same oil-based dye was used when leaders of the same union got the idea to greenify the river for more celebratory purposes on St. Patrick’s Day. Later, at least according to Barry McRaith’s own 2007 obituary in the Chicago Tribune, Sethness-Greenleaf developed and produced a vegetable-based dye that became the new standard for the annual greening of the river; a brilliant marketing move (if true).

Green River’s journey to becoming the official soft drink of St. Paddy’s still had a long and winding way to go, however. While Sethness-Greenleaf owned the patent to the Green River syrup for several decades, the actual ownership of the Green River trademark, and the business sometimes known as the Green River Corporation, is much harder to follow.

[Sethness-Greenleaf, Inc., makers of the Green River syrup for over 50 years, operated out of the building at the left, 1013 W. Webster Ave. in Lincoln Park, before moving in the early 1980s to the facility on the right, at 1826 N. Lorel Ave. in North Austin]

By the early 1980s, actual bottles and cans of Green River had again become almost impossible to find out in the wild, and when a nostalgic fan wrote to the Tribune in 1982 inquiring about the subject, Barry McRaith saw it and wrote a response of his own to the paper. “We [Sethness-Greenleaf, Inc.] are the manufacturers of the Green River flavor as well as the syrups,” McRaith said, “and Green River Corp. is a customer of ours. We have forwarded a case of our Green River Fountain Syrup for [the reader’s] use at no charge. All he has to do is mix it with club soda.”

It’s not clear who Green River Corp. even was at this point, or why no commercial bottling was taking place, but by 1985, Sethness-Greenleaf had opted to sell Green River’s trademark rights to Sun Drop Bottling in North Carolina, under an agreement that Sethness would still produce and provide the concentrate for the drink, and that the “secret formula” itself would remain in escrow until the buyers paid off the full cost of the sale: a still surprisingly meager $75,000. The arrangement wound up a total disaster, as this new version of the Green River Corp., run by Daniel J. Meyers and Cornell Wing, quickly fell behind on its payments and resorted to producing a knockoff version of the Green River formula to keep the product moving.

It’s not clear who Green River Corp. even was at this point, or why no commercial bottling was taking place, but by 1985, Sethness-Greenleaf had opted to sell Green River’s trademark rights to Sun Drop Bottling in North Carolina, under an agreement that Sethness would still produce and provide the concentrate for the drink, and that the “secret formula” itself would remain in escrow until the buyers paid off the full cost of the sale: a still surprisingly meager $75,000. The arrangement wound up a total disaster, as this new version of the Green River Corp., run by Daniel J. Meyers and Cornell Wing, quickly fell behind on its payments and resorted to producing a knockoff version of the Green River formula to keep the product moving.

In the legal fallout, McRaith and Sethness-Greenleaf reacquired the Green River trademarks and went into business with a new small-scale bottling partner in Chicago, Clover Club Bottling at 356 N. Kilbourn Ave. During the ’90s, Clover Club would play a large role in re-establishing Green River’s cultural tie-ins with Chicago institutions and St. Patrick’s Day in particular.

In 2010, a few years after Barry McRaith’s death, Sethness-Greenleaf finally agreed to sell the secret formula and rights to Green River soda to WIT Beverages of Wisconsin, and it quickly became WIT’s best seller over the next decade.

[A Green River display in a supermarket ahead of St. Patrick’s Day, 2020 (an ill-fated holiday due to Covid-19). Posted to the WIT Beverages Facebook page that March]

“We’ve been giving away 20-ounce Green River in downtown by the Chicago River on St. Patrick’s Day since 2010,” WIT president Jim Akers said in 2013. “We’re looking for the connection and people just love it. . . . There are a lot of emotions and loyalty attached to specialty beverages. People who love a certain brand will buy it any way.”

In 2021, Milwaukee’s Sprecher Brewing Co., a leading craft soda producer, acquired WIT Beverages and its full line-up, thus moving Green River under yet another roof. As of 2025, you can buy Sprecher’s version of Green River—supposedly just as it tasted in 1925—in not just the traditional bottles, but also tallboy cans in six-packs and 12-packs. The Sprecher website also sells Green River extract in a jug; Green River t-shirts; and, for some reason, Green River lip balm.

If someone would like to write another song about Green River suited to the 21st century, it would almost certainly be a smash hit. Just contact Sprecher Brewing in advance to avoid any legal issues.

Sources:

“Now It’s New Green Rivver” – Daily Times (Davenport, IA), May 23, 1919

“Romance of Green River, $120,000 Triumph in Realm of Soft Drinks” – The Dispatch (Moline, IL), Oct 4, 1919

“The Source of Green River” – The Daily Illini, Oct 14, 1919

“You Don’t Know What You Can Do Until You Try” – Sales Management, Jan 1920

“We Investigated 1,500 Cases and Found 850 Infringers” – Printer’s Ink, Oct 15, 1925

“Green River Man Bankrupt” – Des Moines Register, May 18, 1938

“Letter from a Jinglesmith” – Sponsor Magazine, Dec 19, 1949

“Irvin J. Wagner, Singing Commercial Pioneer, Dies at 51” – Advertising Age, Dec 11, 1950

“Green River Spurts Under New Management” – National Bottlers’ Gazette, October 1953

“Green River Soft Drink Returns” – The Salisbury Post (NC), July 3, 1988

“Green River Jones” – Chicago Tribune, June 4, 1989

“Sethness-greenleaf, Inc., Plaintiff-appellee, v. Green River Corporation and Daniel J. Meyers, Defendants-appellants, 65 F.3d 64 (7th Cir. 1995)”

The History of Beer and Brewing in Chicago: 1833-1978, by Bob Skilnik, 1999

“Executive Took Pride in Local Flavors” – Chicago Tribune, Dec 25, 2007

“Prime Time for Lemon-Lime” – Chicago Tribune, March 12, 2009

“Green River Success Runs Deep for Beverage Company Owners” – press release, 2013

Another great article, thanks. And something I learned recently follows.

Taking a Newberry Library class in the Spring of 2025 on Industrial Chicago, I learned that the proper way to pronounce Schoenhofen is “Shane Hofen”. Author of a book on Chicago Brewery buildings interviewed a member of the Schoenhofen family to set the record straight.

Still drink Green River when found, usually around St. Pat’s Day in Chicagoland.

I have a brown 4/5 qt bottle that says green river on it. It also says federal law prohibits sale of this bottle can you identify it for me?