Museum Artifact: Hallicrafters Model 5R34A Continental Radio, 1952

Made By: Hallicrafters Company, 4401 W. Fifth Ave., Chicago, IL [North Lawndale]

“For radio equipment that won’t be satisfied with the limits of the pre-war world, for radio that will go places and do things hitherto undreamed of and uncharted—look to Hallicrafters, builders of the radio man’s radio.”—Hallicrafters magazine advertisement, 1944

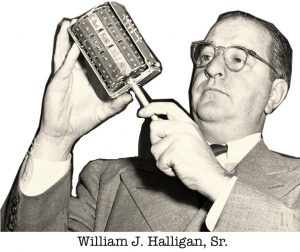

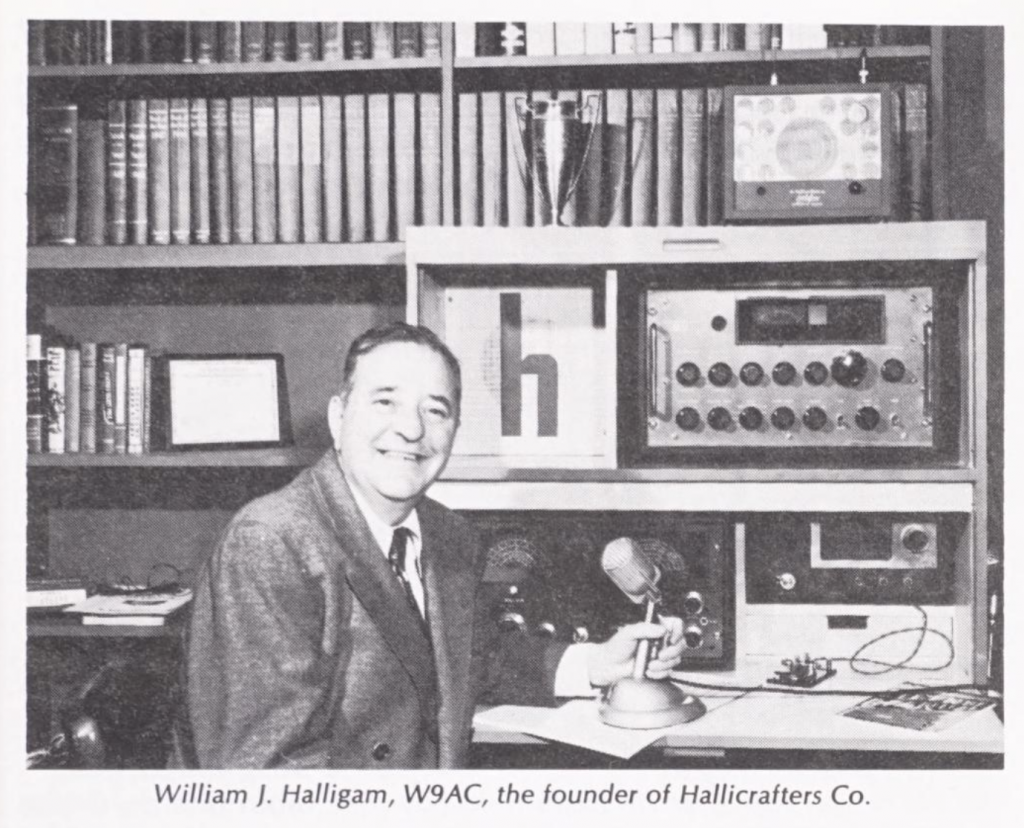

William J. Halligan (1898-1992), founder of the long-defunct Hallicrafters Company, remains something of a cult hero among today’s dwindling but dedicated community of vintage radio collectors (let’s call them “radioheads”). Even compared to some of Chicago’s more widely known contributors to the industry—Admiral, Motorola, Zenith, etc.—the Hallicrafters brand is uniquely revered; in large part for the legendary precision of its products, but also for the uncompromising principles of its president.

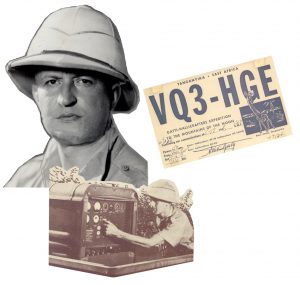

As devotees love to mention, Bill Halligan was one of the original radioheads himself—an active, lifelong “ham” (known by the call letters W9WZE and W9AC) who saw wireless communication as a powerful conduit to a wider world, and who made his mark by adapting that same technology for the benefit of American servicemen during World War II.

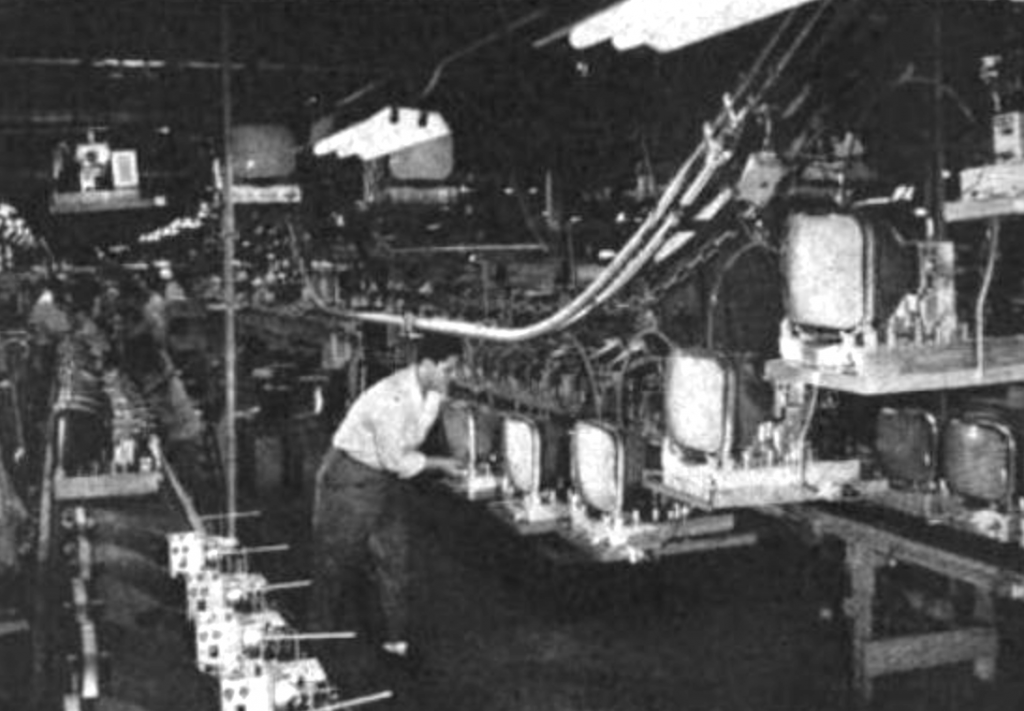

In an odd way, Hallicrafters’ unimpeachable reputation as “the Radio Man’s Radio” has probably obscured just how broadly successful and mainstream the business eventually became at its post-war peak. While it’s fun to picture a half-dozen mustachioed audio artisans furiously fashioning transmitters in a dimly lit garage, there were actually as many as 2,500 Chicagoans in the company’s employ by the 1950s, and more than 500,000 square feet of factory space in use across several different facilities.

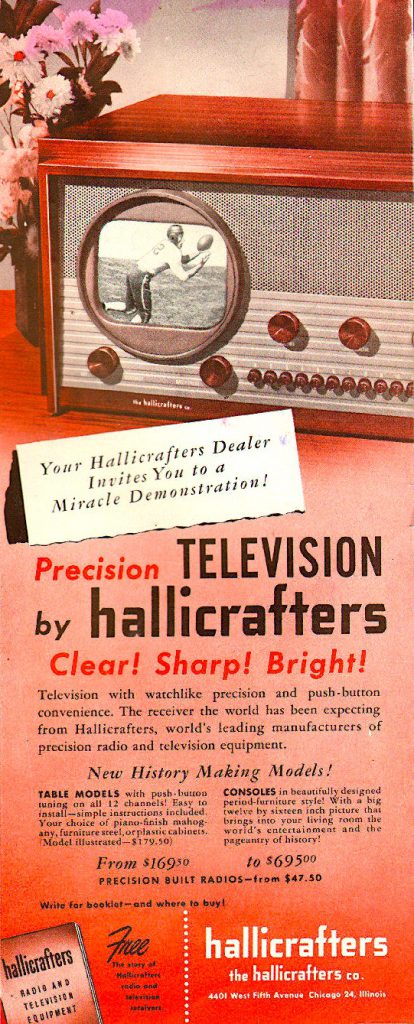

A large percentage of Hallicrafters’ output also included AM/FM radios, phonographs, and television sets—marketed to the average American family rather than discriminating hams or square-jawed naval officers. The famed godfather of streamlined design, Raymond Loewy, was even brought in to gussy up the company’s products for wider appeal.

The specific artifact in our museum collection, the lovely “Continental” radio, is a good representative of that commercial pivot, when Hallicrafters briefly competed with the biggest names in consumer electronics.

The Artifact

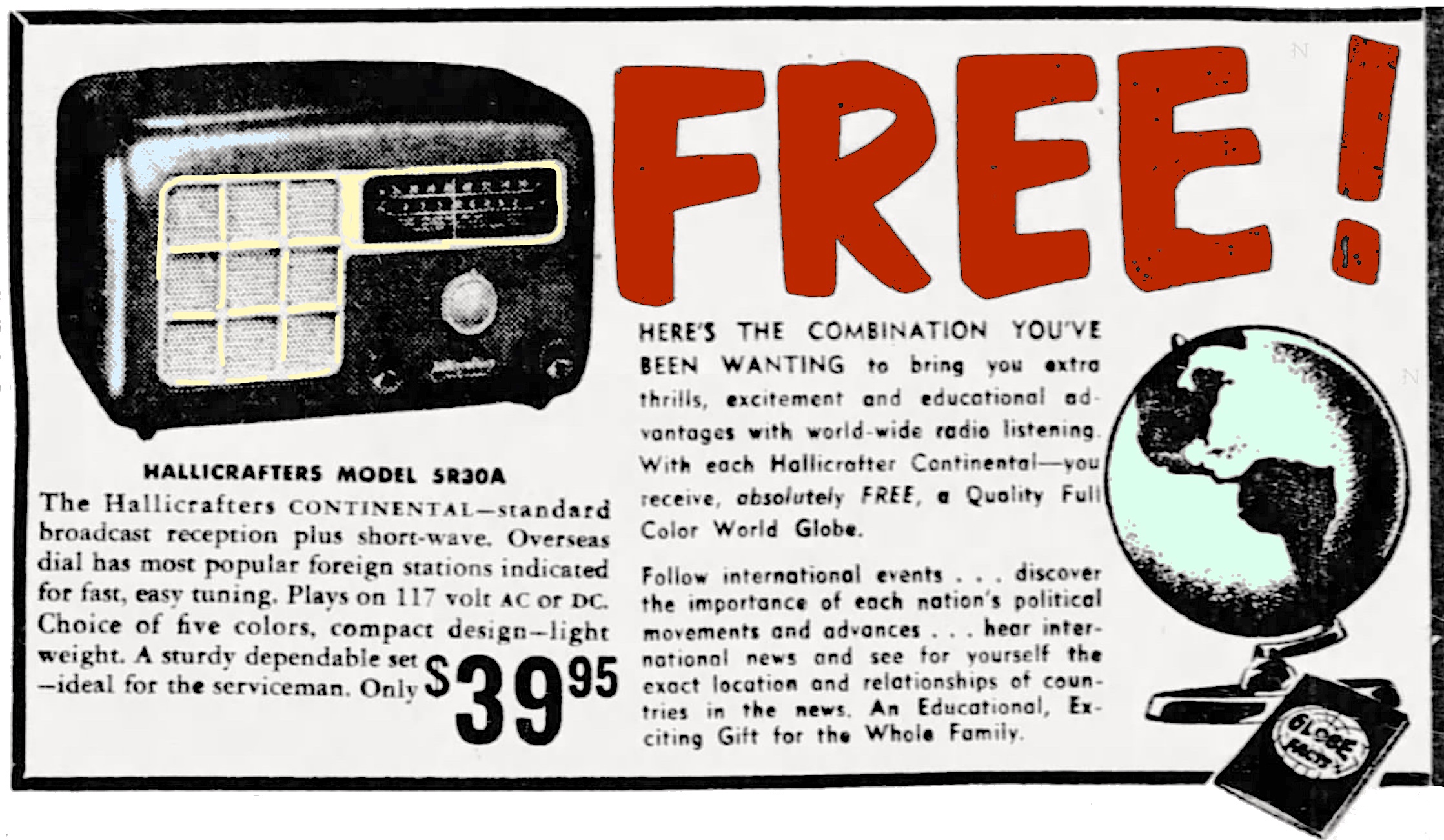

“Now Hallicrafters, unchallenged leader in the field of advanced short wave for foreign reception, brings you a remarkable instrument—the Hallicrafters 5R30A. Here is more than simply a radio—here is the key to the airwaves of the world, for with this set, small though it is, you get world-wide reception. Naturally, you get the finest in regular radio, too.” —1952 newspaper ad for the Hallicrafters Continental Model 5R30

Dating from 1952, the museum’s Continental 5R30 is a “5-tube superheterodyne” tabletop radio with a bakelite casing and a 15-foot antenna for both standard broadcast reception and “the 6 to 18 megacycle shortwave range.” It sold for about 40 bucks (a little under $400 in today’s money) and was available in five color options: forest green, sandalwood, smokey black, dove grey, and our very own “Air Force Blue.” As an added perk, many Continentals were packaged with a free world globe—likely made by Replogle—providing some tangible context to the various foreign transmissions coming through the receiver.

When this radio was in production, Hallicrafters happened to be one of the ten largest television manufacturers in the country, as well, with roughly 80% of its factory output dedicated to TV sets, and most of its R&D time focused on solving the riddle of colorization. Even so, Bill Halligan remained committed to pushing forward with new radio designs—especially ones that enabled war veterans to connect to the international stations they’d discovered overseas.

“Shortwave listening is coming back,” Halligan said in 1951, “and we have the Continental AM-shortwave receiver on the market. It takes its name from its ability to pick up most of the shortwave stations in the world.”

The instruction manual that came with the Continental notes that, “for your convenience, the principal shortwave stations of the world have been clearly marked on the dial.” Those indicated station locations, as seen on our artifact, include: Singapore, China, Egypt, Korea, Cairo, Alaska, Greenwich, London, South Africa, Havana, Stockholm, and Argentina.

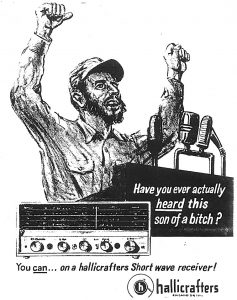

Interestingly, as the Cold War escalated later into the ’50s and ’60s, some Americans actually began to see ham radio as a threat to national security, and ham enthusiasts as potential “sympathizers” to Communist programming coming out of Cuba, China, or the USSR. Fidel Castro’s regular speeches on Radio Havana raised enough concerns that Hallicrafters seems to have addressed the issue in an early 1960s advertisement, depicting an unnamed but obvious Castro at a microphone, with the extremely blunt tagline: “Have you ever actually heard this son of a bitch? You can . . . on a Hallicrafters Short wave receiver.”

We’ve yet to confirm if this advertisement, pictured above, ever ran in any mainstream publications, or of it may have been more of an underground flyer, considering the language. Either way, the message seemed to be that Americans could rest easy knowing Hallicrafters didn’t like Commies after all.

A History of Hallicrafters, Part I: The Boston Ham

“Until Bill Halligan came along and designed a radio set for ham radio operators, the hobbyists built their own receiver and transmitter. These consisted of a ton or more of equipment piled tier-on-tier in a jungle of wiring, usually in an attic or basement. Most of them looked like Goldberg nightmares.” —Sales Management, 1947

William Halligan was undoubtedly the real deal when it came to radio geekdom, but it’s hard to say his entry into the field was any more “pure” than that of his more famous Chicago peers.

Like Zenith’s Ralph Matthews and Karl Hassel, he started out as a teenage ham radio enthusiast, building his own units and earning a job as a professional wireless operator in his native Boston by the age of 16. He then honed his skills serving in the military during World War I—much like Paul Galvin of Motorola—and ultimately made his first foray into selling radio parts in 1924, the same year Ross Siragusa of the Admiral Corporation started his original business doing the same.

There were a few potentially divergent paths Halligan had nearly taken in his youth, however. Growing up in South Boston—a third generation Irish-American—his obsession with wireless tech was partially a distraction from a hardscrabble existence that involved plenty of fist fights.

Halligan’s father—a saddlery salesman—had died in 1902 when Bill was just 3 years old. A baby sister, Mary, had also died the same month, suggesting a possible connection between the two tragedies. Bill’s mother ultimately remarried and moved to the Charlestown neighborhood, and several half-brothers and sisters resulted from it, but Bill—like many hams—seemed a bit isolated in his interests, while simultaneously desperate for a wider connection.

[A ham radio operator, early 1920s]

Halligan’s war service mostly involved handling communications on a mine layer vessel off the coast of Scotland. Upon returning, he attended West Point for a couple years—destined to follow a family tradition of military officers—but he met a girl named Kate instead, and left West Point to marry her in 1922.

In his 20s, Halligan briefly re-imagined himself a newspaper man, and got a job as a reporter with an upstart paper called the Boston Telegram, where he covered some of the rum running cases coming through the federal building around 1922/23. He also had a regular column called “Radio Waves,” where he shared his views on the latest developments in DIY wireless. When the Telegram abruptly went out of print, its publisher launched a new paper, the New York Bulletin, and Halligan reluctantly took his journalist hat down to NYC to keep the gig going. The Bulletin (not to be mistaken with the fictional newspaper from the Marvel universe) folded after six months.

It was during that brief time in New York, however, while attending a radio convention at Madison Square Garden, that Halligan met a Massachusetts radio parts dealer named Tobe Deutschmann. “You are in the newspaper business when you should be in the radio business,” Deutschmann supposedly told him, and the two were soon partners, with Halligan becoming a lead sales manager for the “TOBE” brand back in Boston.

Along with his encyclopedic knowledge on the subject, Halligan’s boyish enthusiasm for ham radio made him an excellent salesman, as well, and his love for the hobby never really wavered with age.

“The radio ham market is the most challenging and thrilling in all radio,” he later said. “Lots of people just get a kick out of listening to police calls on short waves. Or you can tune in on ship-to-shore conversations—eavesdropping is a lot of fun, you know.”

II. Crafting a Brand

In 1928, with radio sales exploding, Halligan decided to strike out on his own. He also made the astute decision to move his family to Chicago, which he’d visited several times as a salesman and had deemed the rising epicenter of his industry.

This is the part of the story, of course, where the stock market eventually crashes and all youthful optimism is severely tested. Bill found that many clients who’d been eager to buy his specialized radio parts started sealing up their wallets in the early 1930s, but rather than playing it safer, he felt more motivated to expand his clientele beyond the “enthusiast” community. To this point, as Halligan saw it, there had still never been a proper, compact shortwave ham radio receiver built for regular commercial sale—something that could be used out-of-the-box without too much expert tinkering. So, starting with one hand-built prototype, he set out to find a business model for selling on a wide scale.

“That was the start of Hallicrafters,” Halligan recalled to the Tribune in 1950. “All the money we had was in our pockets. We got orders, then got material on the basis of those orders and then got money when we sold the sets.”

Things were actually a tad more complex than that, although similarly desperate. In its early days, Hallicrafters—so named to emphasize the “hand-crafted” nature of the ham sets—couldn’t afford its own manufacturing facility, nor did it have a much coveted license from the mighty RCA to make certain patented parts. As such, Halligan was forced to get creative in order to get his early “Skyrider” receivers produced in the light of day.

In 1933, he briefly operated as the “Silver-Marshall Manufacturing Company,” borrowing the defunct business property of a licensed Chicago radiohead, McMurdo “Mac” Silver. The Howard Radio Company, over at 1731 W. Belmont Ave., also is believed to have shared its resources.

After a year or so, Hallicrafters was finally making some headway. Selling almost entirely via mail order and leasing his own manufacturing space (first at 417 N. State Street, then 3001 Southport Avenue), Halligan managed to get a full page article published about his receiver design in the August 1934 issue of Popular Mechanics—albeit, with no actual mention of his name, the Hallicrafters Company, nor the Skyrider brand. But hey, it was a start.

“Short wave listeners can now enjoy foreign and domestic programs without the use of converters, adapters or plug-in coils,” the article noted. “Combined in one compact unit, this short-wave receiver includes a built-in dynamic speaker and employs tubes of the latest type in a regenerative circuit composed of a pre-selector r.f. stage and regenerative detector using the new type 6D7 super-control screen-grid tubes.” —Popular Mechanics, August 1934

If you understand Depression-era amateur radio technology, I hope that further contextualizes things for you.

In any case, as word began to spread about these swell new Hallicrafters products, Bill Halligan was more compelled than ever to find a good manufacturing partner. He tried a marriage with the Case MFG Co. of Marion, Indiana, which promptly flopped, then shifted back to Chicago for a more fruitful arrangement with the Echophone Radio Company in 1936.

[The former Echophone Radio factory space at 2600 S. Indiana Ave. became Hallicrafters’ new dedicated HQ in 1936, and would remain so until 1945. The building is no longer standing. Above image comes from ad brochure reprinted in Chuck Dachis’ 1996 book, Radios by Hallicrafters]

Echophone was actually scuffling financially at the time (as was the fashion), but one of its managers, Ray Durst, helped organize the merger to everyone’s benefit, allowing Halligan to have the controlling interest and run of the factory, while Durst himself started a long tenure as his vice president. Echophone would remain a brandname under the Hallicrafters banner for years to come, and its old building at 2611 S. Indiana Avenue would serve as Bill Halligan’s first true dedicated Chicago radio factory . . . the top four floors of the building, at least.

With proper real estate and licenses now at his disposal, Halligan went full speed ahead turning his creative energy into an ever-expanding line-up of radio receivers. Twenty-three such models were rolled out between 1936 and 1938 alone, according to Chuck Dachis’ book Radios By Hallicrafters, and the company was swiftly regarded as the leader in such devices.

[Bill Halligan, mic in hand, leading a ham party at Hallicrafters’ Indiana Avenue offices, circa 1938. Joining him, from left to right, are engineer Fred Strowatt, salesman Royal Higgeons, purchasing agent Ed Caroran, production engineer Loren Toogood (that name is too good!), VP Ray Durst, controller Joe Frendreis, production manager Herb Hartley, chief engineer Bob Samuelson, and receiver engineer L.A. McLaughlin]

Halligan might have been a purist and a perfectionist, but he wasn’t an elitist. He wanted amateur radio to be simpler and more accessible to the general public—especially the next generation of young enthusiasts following in his footsteps.

“Produce a set that is compact,” he told his engineers [according to a 1947 issue of Sales Management]. “Get rid of weight. Make it smaller, smaller, smaller.”

“He wants something that will float,” moaned one of his harassed aids.

Halligan also wisely made a point of creating two tiers of receivers to appeal to more types of customers. Early sets like the S-19 and S-38 catered to the newbie, while the more sophisticated SX-17, SX-18, and SX-28 appeased the experienced, hardcore hams. In all cases, prices were kept low and sales numbers benefitted.

Hallicrafters had muscled its way out of the Depression and generated plenty of attention around the world. The U.S. government was taking notes, too, and started calling upon Hallicrafters for communications help even before World War II made such relationships a strategic necessity.

III. Bombproof

“Hallicrafters sets were developed in the great testing grounds of amateur radio. They have served an ‘attic apprenticeship’ and have come out of the attic to go around the world with victorious Allied armies.” —Hallicrafters advertisement, 1944

In the summer of 1941 (according to company lore), one of Bill Halligan’s tidy new 450-watt transmitters—the three-foot tall, $700 HT-4 rig—was procured from his Chicago offices by a rather insistent G-man from the FBI. That unit was eventually put into service by the Signal Corps 4,000 miles away—in the hills above Honolulu—and wound up playing a crucial role in keeping communication lines open for survivors of the Pearl Harbor attack that December, when most traditional wire and radio facilities had been lost.

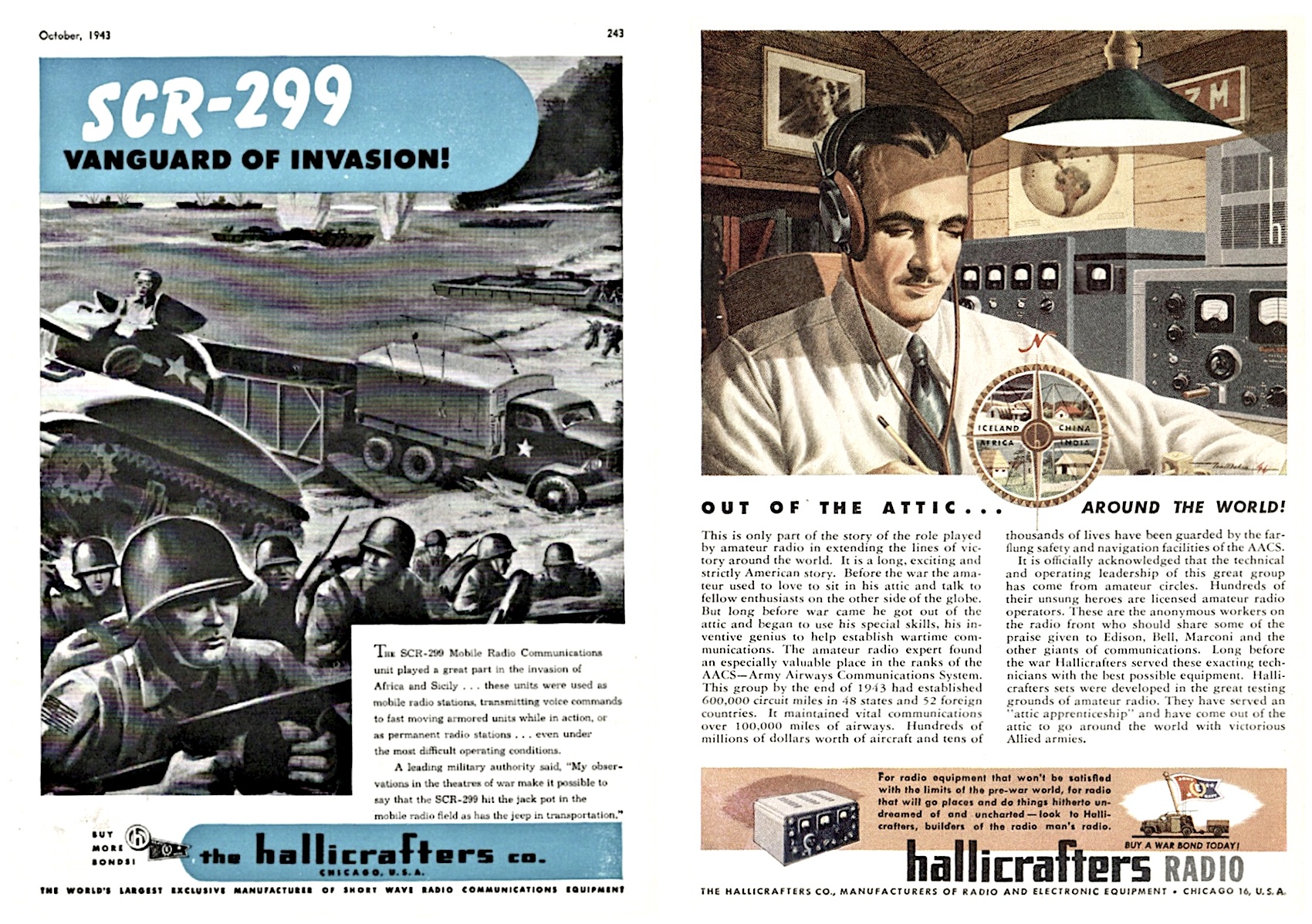

[Hallicrafters ads during World War II focused on promoting the company’s contributions to the Allied cause, as its civilian line wasn’t being produced]

After that, the HT-4 became part of the Signal Corps’ SCR-299 mobile communications unit, and “saw service on every battle front from the Aleutians to New Guinea and from El Alamein to Bastogne,” according to a 1952 story in the trade publication Signals. “The ruggedness, dependability and characteristic flexibility of good ‘ham’ design proved readily adaptable to military requirements,” and the HT-4, in particular, “provided one of World War II’s most dramatic demonstrations of the part played by America radio amateurs, and the companies which build equipment for them, in the successful outcome of the war.”

Hallicrafters was essentially saying the same thing in its own advertising, even before the war had ended. Since the company had put its civilian ham radio production on hold, it relied on its military exploits to generate interest in the brand once peace returned.

In one emblematic ad from 1943, the company reprinted part of a letter sent to their offices by an Allied soldier based in Glasgow, Scotland, who recounted what happened after a bomb tore through a military radio shack and smashed his Hallicrafters Sky Champion S-20R receiver under “half a ton of plaster ceiling.”

According to the unnamed letter writer, “When we dug it out and shook the dust out of it (and how!) we plugged it in again to the nearest undamaged A.C. line, and it worked. The net damage was one tube, a bit microphonic, one dial light bulb gone, and an almost cracked joint on the lead to the grid of the 6K8! ‘Hallicrafters Build Bomb-Proof Rigs!’ How’s that for a slogan?”

Call it capitalist propaganda if you wish, but as stories like this made the rounds among servicemen, Hallicrafters only saw more requests (and more money) coming in for additional equipment.

“More than 44 million dollars’ worth of radio equipment for the army and navy and lend-lease has been manufactured by the Hallicrafters company since Pearl Harbor,” the Tribune reported in December of 1943. “In the year preceding, sales were 2 million dollars.”

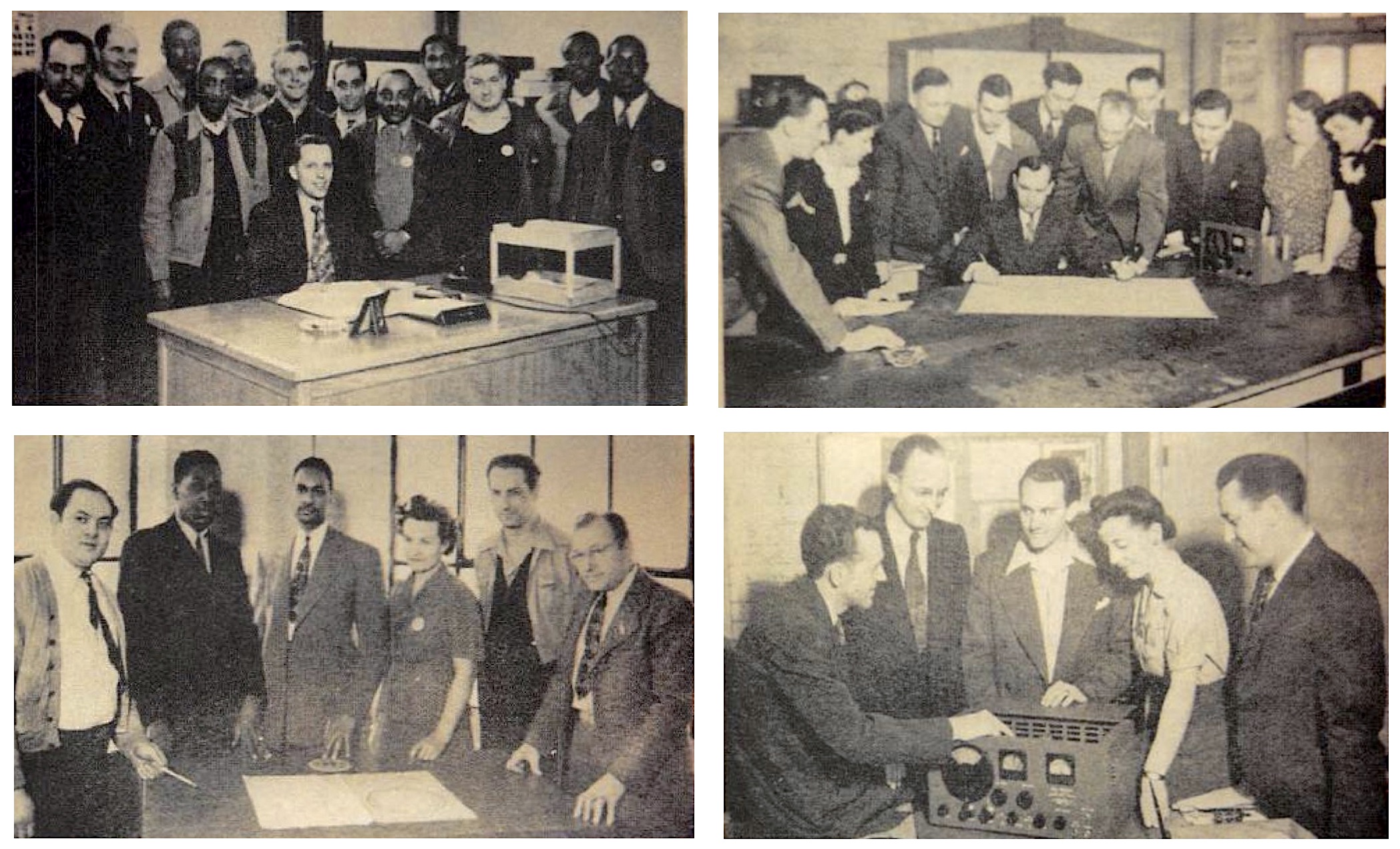

To keep up with this transformative growth, William Halligan—still a young man barely over 40—had surrounded himself not only with skilled craftsmen, but many unheralded heroes of the research, packing, shipping, and accounts departments. Together they’d created the “world’s largest manufacturer specializing in short wave communications equipment.”

Some of Hallicrafters’ wartime team in Chicago, from the 1944 booklet “The HT-4 Goes to War.”

Top Left: Production & Shipping team at the company’s #2 plant in Clearing – Shop foreman Earl Barnes (seated) with Harold De Bonis, Oliver Newman, Walter Maloni, Willis Johnson, Buck Rogers(!), George Hjelkrem, Mike Perri, James Maxey, B. Flowers, Fred Porter, William Conway, and D.C. McCann.

Top Right: Department Heads and their assistants in General Engineering – from left, Corwin Livenick, Myrtle Willner, Milton Wullenweber, Ed Keyes, Harry McCarty, Jay Dawson, Jules Leonhardi, Ed Voznak, Wally Hildebrand, Ann Fremarek, and Florence Lindahl.

Bottom Left: Spare Parts dept., in partnership with the Voltz Bros. Co. and its 29th street plant – Tom Caprio, August Fisher, Henry Baker, Lulu Dimitz, Frank Oslakovich, and Mike Jakubczak.

Bottom Right: Production Records team – Carl McConkey, W. Carlson, Ben Timms, Eleanor Foster, J. Smith

Hallicrafters collected its share of Army-Navy “E” awards for excellence in wartime production, but the real reward was in the loyalty they’d earned from returning soldiers, many of whom remembered the brand that had been there with them; always precise and occasionally “bombproof.”

[1944 Hallicrafters Promotional Film, “The Voice of Victory,” includes footage of William Halligan in his office and the Hallicrafters assembly line workers in one of the Chicago plants.]

IV. New Adventures in Hi-Fi

In the introduction to his 1945 African safari memoir South of the Sahara, explorer Attilio Gatti wrote in glowing terms about Hallicrafters, which had also (coincidentally) sponsored his expedition.

The Italian-born adventurer noted the “admiration and gratitude I owe to the Hallicrafters organization, their imaginative leadership, their precise technique and exquisite craftsmanship. For much of the success which crowned the various quests related in this book is due to the invaluable assistance and comfort which was every day given us by our Hallicrafters short-wave receiving sets—those neatly compact, wonderfully efficient ‘magic boxes’ which never once failed to keep me in contact with my expedition companions, and all of us in touch with the rest of the world.”

After the war, Hallicrafters returned to civilian production with a load of new resources and a renewed sense of adventure (safari-based and otherwise). As demand had grown, they’d already cobbled together more factory space across several far-flung buildings (mostly on the South Side), but Bill Halligan was now determined to move out of the old stuffy Indiana Avenue plant into something more befitting the bigger company and its sterling reputation.

“I walked round the area where our factory site was and found it had a hard, industrial look,” he later told the Tribune. “If I made beautiful radios—this was before the day of television—I wanted to make them in a beautiful building. I explained what I wanted to my architect, Mr. Epstein—something reminiscent of New England—and he carried out my wishes to the last brick.”

[Then & Now: The former Hallicrafters factory at 4401 W. 5th Ave., most recently home to a Nationwide Furniture showroom]

That building, located at 4401 W. 5th Avenue at the intersection of Kostner Avenue, is still standing today—across from two vacant lots and kitty-corner to the Charles Sumner Math & Science Community Academy in North Lawndale. It looks every bit as out of place now as it did 75 years ago—a one-story, Georgian-style mansion of sorts, with large columns out front a big front lawn once adorned with ornate gardens.

Fortunately, on the inside, the plant was more . . . plant-like, with modern air conditioning and sprinklers and highly efficient assembly-line conveyors helping workers churn out about 600 communications and radio sets and a whopping 1,500 television sets PER DAY by 1951. Employees also had other perks besides pretty surroundings and a sense of accomplishment.

“The company’s normal staff of approximately 2,500 employees, of whom 1,960 are factory workers, have the use of modern cafeteria, wash room and locker facilities, and benefit from company paid group insurance, paid vacations, Christmas bonuses, and a liberal profit-sharing pension trust,” Signals reported. “As a result relations with the employees have been tranquil and Hallicrafters has fared well in competition with other employers for desirable workers.”

All that being said, Bill Halligan—while an amiable chap—wasn’t necessarily concerning himself much with coddling workers. His views on work were rooted much more in his West Point experience, as he made clear in a 1951 speech given before the Armed Forces Communications Association.

“What’s wrong with Americans today,” Halligan said, “is too many are concerned about the 40-hour week. America was not built that way. Our forefathers worked hard to establish this country on a good, firm basis and it is about time we returned to those principles.”

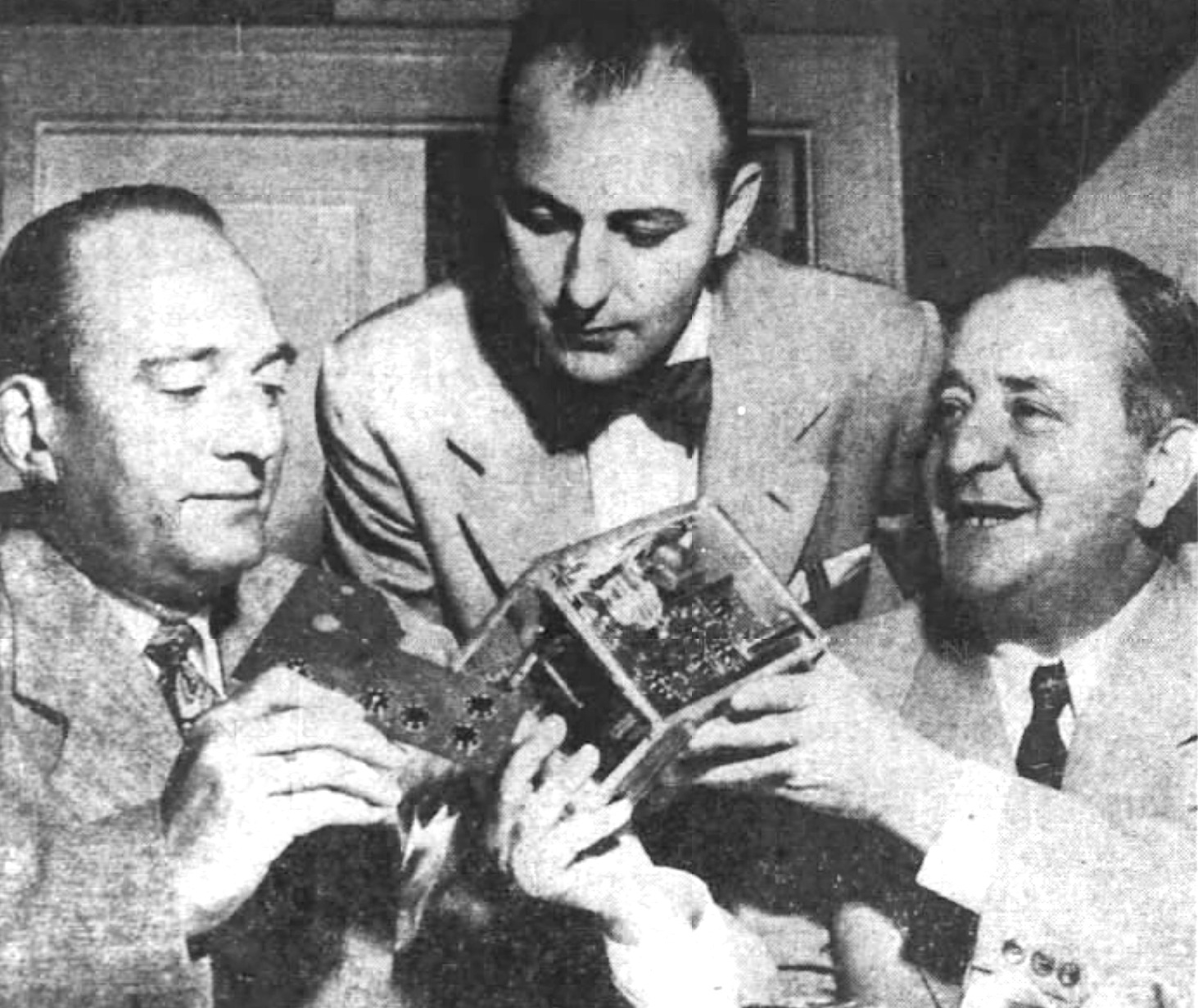

[William Halligan Sr. (right) talks TV circuits on a trip to L.A. with Ray B. Cox (left) and William Halligan Jr. (center) in 1952]

V. Video Skilled, the Radio Star

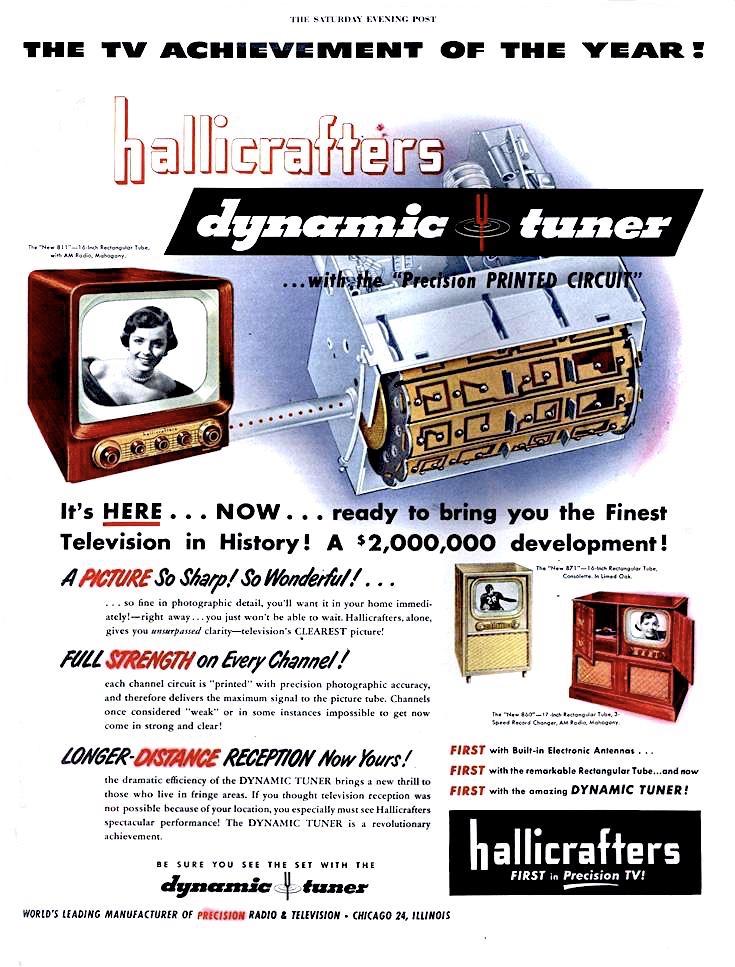

“When you turn on this beautiful console, you’ll thrill to television’s clearest picture . . . a spectacular performance! Hallicrafters sensational DYNAMIC TUNER with the ‘Precision Printed Circuit’ is the answer.” —Hallicrafters Television ad, 1950

America’s transition from radio to television wasn’t as gradual as one might presume. Since much of the technology was already there during the war years—essentially stuck in an indefinite arrested development—the anticipation was bubbling over as reunited post-war families finally set out in search of new entertainment. And while some radio makers folded their arms and refused to jump into the TV “fad,” most of the larger manufacturers felt they had no choice but to try and ride the wave.

“It was a natural for us,” Bill Halligan told the Tribune in 1950, “because we’d been building radio sets for years bracketing the frequencies now used for television channels.”

Much as radio had been back in the 1920s, TV was the Wild West in the ‘40s and early ‘50s. Changes came quickly and the boat was perpetually rocking. A company that seemed to be at the forefront of innovation one month could be left in the dust the next. For its part, considering its relatively small size, Hallicrafters fared quite well. As mentioned earlier, more than 80% of their manufacturing focus had switched to TV by 1950, and they were a viable name on the national scene; ranking in the top ten in television set sales.

Halligan—who was gradually joined in the daily operations on 5th Avenue by his sons William Jr., Robert, and John—saw no reason why his company’s reputation for precision performance couldn’t migrate to the TV era. Unfortunately, bumps in the road started popping up pretty quickly.

Before 1950 was over, Bill Halligan Sr. was already in a public war of words with the Federal Communications Commission, after the FCC chose the Columbia Broadcasting System’s mechanical color wheel as the standard for general commercial licensing. Claiming the decision would require black-and-white TV owners to buy additional equipment to continue picking up their regular channels, Halligan signed his name to an advertisement / open letter in which he claimed that “This ill-advised action of the FCC is a threat to the American way of life.”

The Chairman of the FCC responded by accusing Halligan of a “smear campaign” to “deceive and frighten the public.”

Halligan ends up looking pretty smart in hindsight, as the CBS color system ultimately flopped due to its incompatibility with black and white sets. “The mechanical system of color television is dead as a doornail,” he told the Los Angeles Times in 1952. “The only possible system that can be used is the compatible electronic system of color TV.”

In the same interview, Halligan also foresaw the “shotgun wedding” of television and Hollywood—this during a time when many film producers still saw TV largely as a threat to the movie industry.

“Hollywood will in time become the TV capital of the world,” Halligan said.

Hallicrafters put a lot of work into testing its own electronic color system for television, but as the Korean War ramped up, the factory returned increasingly to its old bread-and-butter—military communications equipment—and its influence in the television business soon eroded.

VI. End Transmission

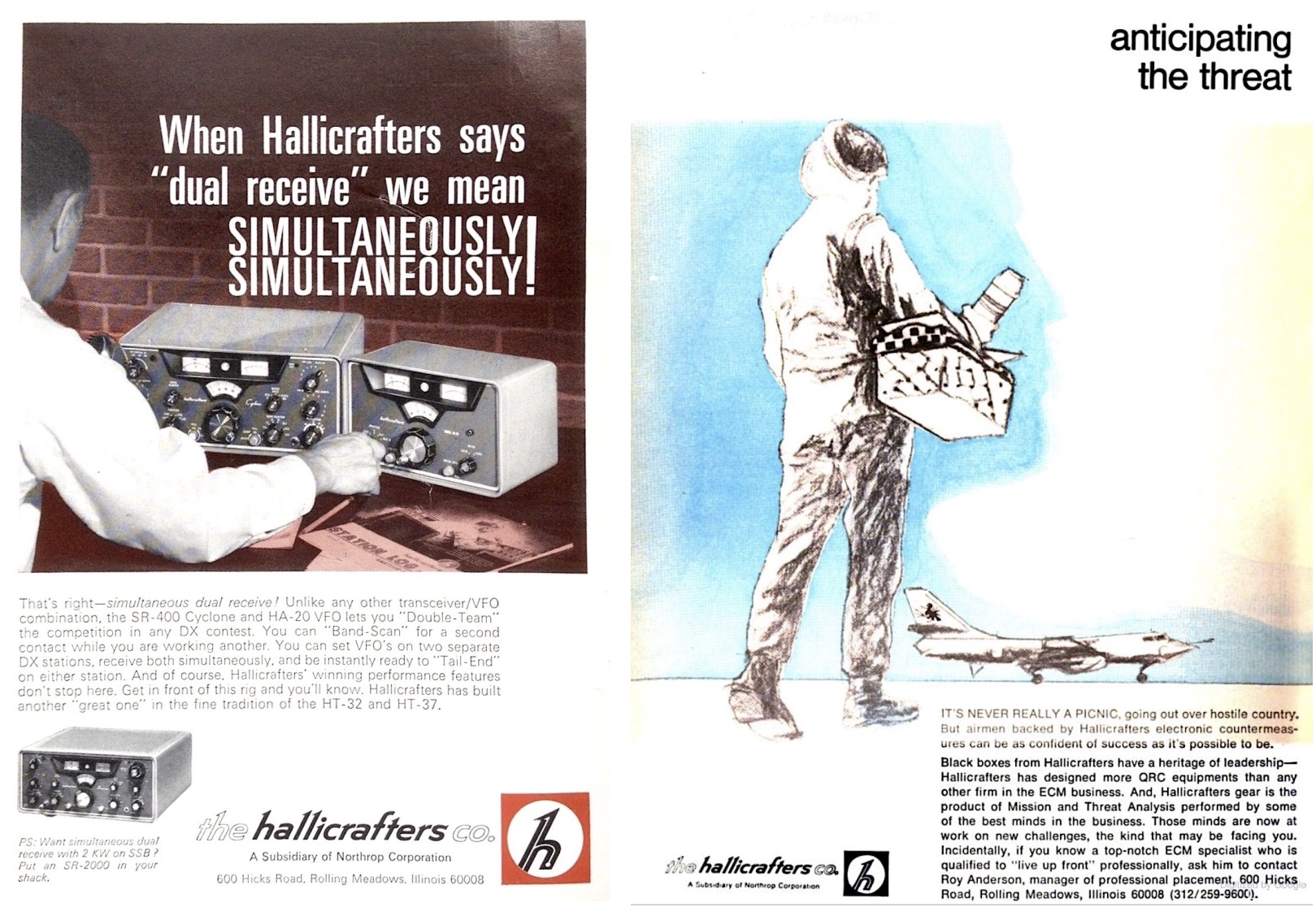

Despite fizzling out of the TV market, Hallicrafters’ final decade as a family business, from 1956 to 1966, still saw record sales figures—mostly through military contracts (including the new fields of space communications and missile defense systems), but also through steady success in the shortwave radio market, as the company’s ham kits continued to sell well through the catalogs of Sears, Montgomery Ward, and others.

Technically speaking, the Halligan family actually lost their majority ownership of Hallicrafters for a brief period from 1956 to 1958, selling out to the Penn Texas Corporation in exchange for $6 million in Penn Texas stock. In some respects, that deal “backfired”—but only for Penn Texas, as a proxy fight within that company sent them into massive debt, forcing P-T to sell Hallicrafters at a bargain price . . . right back to the Halligan family, who also cashed in their P-T stock for a double-win. It was the kind of lucky break that propels a business for years, and indeed, Hallicrafters—with Bill Sr. as chairman, Robert Halligan as president, and John Halligan as secretary—thrived through the early 1960s.

Over-dependence on unpredictable government contracts can be a tricky gambit, however, and when profits finally turned the wrong direction in 1964 and ’65, rumors swirled that the Halligans were—once again—on the lookout for a buyer. In July of 1966, they finalized a deal with the Los Angeles based Northrop Corp., which paid a little over $13 million to take over Hallicrafters’ Chicago operation and various other subsidiaries.

As is often the case in these types of deals, Northrop had its own specific reasons for acquiring Hallicrafters, and it had far more to do with para-military equipment than ham radios for the home. In the late ‘60s, the colonial-looking North Lawndale plant was shut down, and most Hallicrafters operations were relocated to the suburb of Rolling Meadows, IL, at 600 Hicks Road (which is still a Northrop-Grumman facility to this day). Amateur radio production was essentially over by 1972, and the Hallicrafters name became increasingly expendable, passed from Northrop to its partner Wilcox, then from Wilcox to the Braker Corp. of Dallas, Texas, in 1975.

[Advertisements from Hallicrafters’ brief time as a Northrop subsidiary, 1969. The company left Chicago for Rolling Meadows, IL, at this time, and would soon drift out of existence entirely]

After the Braker acquisition, all of Hallicrafters’ remaining Illinois backstock was hauled away to Grand Prairie, TX, and when Braker subsequently folded in 1980, the sad, drawn-out death of a once great company was mercifully completed.

Naturally, because of Hallicrafters’ surviving reputation for quality, there have been attempts to bring back the brand over the years. No efforts proved successful, however, and most diehard Hallicraftees have been content to seek out the original Chicago products rather than waste any more time wishing for a revival.

SOURCES:

“Hallicrafters: The Radio Man’s Radio” – Signals, January-February, 1952

Radios By Hallicrafters, by Chuck Dachis, 1996

Radio Manufacturers of the 1920s, Vol 3, by Alan Douglas

“Compact Receiver for S-W Listeners” – Popular Mechanics, August 1934

“New England Type Factory a Beauty Spot” – Chicago Tribune, Jan 17, 1954

“Smear Against FCC Is Charged” – Corpus Christi Caller Times, Nov 5, 1950

South of the Sahara, by Attilio Gatti, 1945

“The HT-4 That Went to War” – Chicago Tribune, Sept 17, 1951

“Writer for Radio Becomes Leader in Video Industry” – Sunday Times (New Brunswick, NJ), Dec 24, 1950

“Hallicrafters Company” – Business Policies and Decision Making, by Raymond J. Ziegler, 1966

“Halligan, Ex-Navy Recruit, Returns to Lecture Big Brass” – Boston Globe, Dec 20, 1951

“Happy Shotgun Union of Films and TV Seen” – Los Angeles Times, Aug 20, 1952

“The Road to Success: Sketch of William J. Halligan, Head of Hallicrafters Company” – Chicago Tribune, Oct 3, 1953

“Sell Part of Hallicrafters for More Than It All Cost” – Akron Beacon Journal, June 13, 1961

“Electronics Firm’s Profits 14% Higher, Robert Halligan Named Chief” – Chicago Tribune, Dec 19, 1962

“Northrop, Hallicrafters Directors O.K. Acquisition” – Chicago Tribune, July 21, 1966

I am very curious where was the plant located near Midway, the one mentioned in the video, in ‘Clearing’?

Thank you for this very interesting history writeup. I am restoring an old S-38D for my channel and it was great to have read this page to give context to the viewers (I added a link to it as well).

Does anyone know who the current court appointed trustee, or current owner is for the Hallicrafters brand, any intellectual property, and how to get ahold of this person? I’m a member of a historical radio society and we’re interested in obtaining some or all of this material for our museum.

Can. I. Buy. Old. Shortwave. In. Chicago ill. 1930. 1940 1950.

My father worked at Hallicrafter Radio in th late 30’s or early 40’s as an engineer. His name was Karl Walker Miles. We had an SX-25 for years. It was our prime radio. I am really sorry I got rid of it. Would love to get one back. His call sign back then was 8AQA or 8DEL, his recent call was K1KQJ and mine is K1YCD. Hope all you Hallicrafter people are enjoying your rigs. I think I may have some old sales flyers.

my dad, George Herbert (Herb) Hartley, production manager

As a teenager, I couldn’t wait to get my Ham license and get on the air, I lived in Chicago and was well aware of Hallicrafters. I bought an SX25 for about 100 dollars, in 1946 and even worked at Hallicrafters in 1951. They were building TV sets for Sears and I was on the final inspection line. In 196 or 7 I found a used S27 receiver in a south side TV shop and bought it and used it on Ten Meters. I bet it came from the University of Chicago. They were teaching radio during the war.

Does anyone know what the S27 was used for during the War?

73s, Jack

In the early 80’s I worked with a man named Albert Ponterelli at Zenith Radio Corporation. (I might have spelled Al’s last name wrong.) Al was a joy to work with, and a great mentor. He was an amateur pilot and built his own plane, (he also liked Chicago deep dish spinach pizza). He told me that he was Chief Engineer at Hallicrafters at one point in time. I wonder if anyone could verify that. Thanks

I just found this website and just like Ron Reisener I also worked at the 5th Avenue plant on the Qrc128 project 1967 to 1970. When I got out of the AirForce I went on a blizzard day and knocked on the door of a Hallicrafters building located around 59th and Harlem. A man answered the door and let me in. I had my suit on and my radio electronics diploma in hand. The man was Bill Halligan and he said anyone that would go out on a blizzard day like this deserved a job. He told me to go to 5th and Kostner on Monday morning and give security your name and this card. I was hired as an analyzer troubleshooting and aligning modules for the Qrc128. Later on working all phases of the project until I was layed off when the plant closed. I have been a big collector his radios and I am an extra class ham radio operator. k9wls

can i fine a part for 5r30 and hoe we can get it thanks’

I started working for Hallicrafters in 1964 as an Industrial Engineer at the 5th Ave. plant.

I was involved with the military QRC 128 (Quick Reaction Capability) program which consisted of an expendable radar jammer which was to be deployed from an aircraft while attached to a balloon in case of an ICBM attack.

I spent 1965 working at Hallicrafters plant close to Midway Airport making electronic organs for Lowery Organ Co. The rumored possible sale to Northrup with it’s uncertainty caused my search for a new job.

I have the original full page paper poster of ( presumably ) Mr. Castro speaking on radio.

Your rendition does not show the bottom of the page, where there are a couple horizontal lines replicating, apparently, additional Hallicrafters text such as address, without actually using any text. Neither Halli nor any other manufacturer would at that time use any even mildly offensive language. My surmise is, this “ad” page was generated somewhere along the wholeselling chain. Maybe even by a Halli employee, but it was surely not an actual Hallicrafters company product. The page i have, came out of a 1964 date booklet of Hallicrafters products, this prepared for retail sellers.

Good insight, Hue. This definitely makes sense, as that type of ad copy did seem quite extreme for the time period (or even for today).

I have come across a Hallicrafters FM-66. I’ve only found very limited information on it. It plays wonderfully, it’s a yard sale find I’m curious about its life. Any information would be appreciated.

Where can I get a schematic for the Halicrafter SX 99? My unit is well preserved yet needs maintenance.

Thank you!

Thanks for such WONDERFUL and most comprehensive history on a truly great US company and amazingly talented Founder. I have been in Amateur Radio since 1969, and restored a Hammarlund HQ129-X radio I still have 50 years later. There are great photos of them being built in NYC. I was searching for a good Hallicrafters SX-28A for years and just bought one for $600, restored great condition on ebay. It has TWO RF (Radio Frequency) tube stages, goes up to 42MHz (usually 30MHz is the limit, just including the 10 meter Ham Band), and TWO powerful 6V6 Audio Amplifier tubes AND even Bass switch and Tone Control. I wanted one as a ham and Electronics Engineer because it is historic and was the pinnacle of WW2 SW Receiver technology, and used widely for the war and intellegence operations – many in Secrets of WW2 Documertaries for example, featured on their title screen!

Hi Ray,

I just found this site. sx 99 manual, and more, can be downloaded here:http://jptronics.org/Hallicrafters/manuals/halli.sx-99.pdf

As Hallicrafters fan and user, a fantastic site !

Giovanni Mai, IK1DGZ