Museum Artifacts: Hammond Solovox Keyboard Model J, Series A (1940s) and Hammond Organ Generator Oil Can (c. 1950s)

Made By: Hammond Organ Co., 2915 N. Western Ave. and 4200 W. Diversey Ave., Chicago, IL [Hermosa]

“Smaller than a piano, a midget in comparison with the vast pipe organs of traditional style, yet capable of 253 million different tones; this is the electric organ invented by Laurens Hammond of Chicago.” —Popular Mechanics, April 1936

It’s hard to say how a musical instrument designed to imitate hundreds of others could also simultaneously be “distinctive” in its sound, but such was the case with the classic Hammond organs of the mid 20th century; easily among Chicago’s most significant contributions to modern music technology.

It’s hard to say how a musical instrument designed to imitate hundreds of others could also simultaneously be “distinctive” in its sound, but such was the case with the classic Hammond organs of the mid 20th century; easily among Chicago’s most significant contributions to modern music technology.

Invented in the heart of the Great Depression, the electric organ arguably made a more substantial, immediate impact on the culture than the first electrified guitars introduced a few years earlier. Whether employed in churches or jazz bars, these relatively space-efficient machines represented both a simplified alternative to the acoustic keyboards of the past and a highly complex evolution of their capabilities. But you didn’t necessarily have to give up your old piano to make room for Hammond’s strange new frequencies.

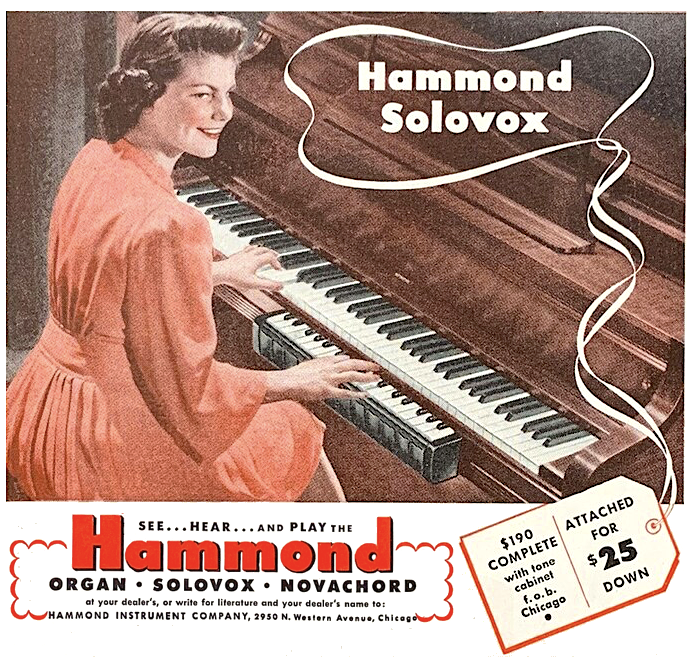

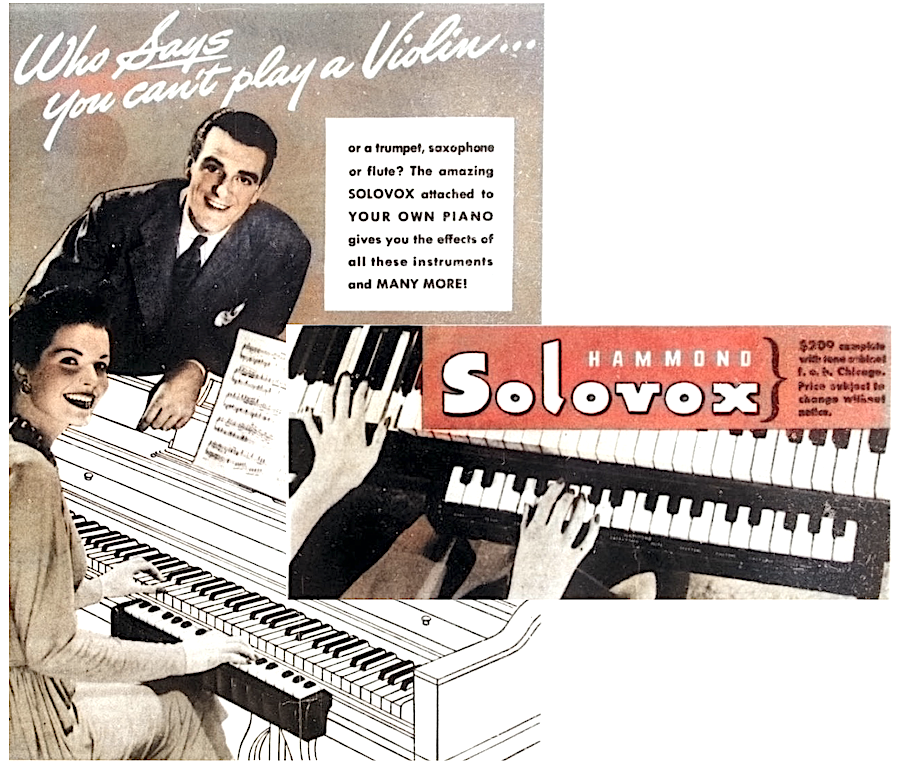

The artifact in our museum collection, known as the Solovox, was an early Hammond product that functioned sort of like a set of training wheels for people curious about electronic music, but not yet willing or able to purchase a stand-alone tonewheel organ. Instead, the 36-key Solovox (plugged into its own radio-style tone cabinet) could be attached directly under the keyboard of a standard piano, allowing the performer to create sustained electronic tones with their right hand while performing traditional piano accompaniment with the left.

“The music sensation of 1941-42,” read an ad in the Saturday Evening Post, “the Solovox brings to your fingertips the vivid, colorful effects of almost every instrument in an orchestra! And playing your piano and Solovox together is easier than playing the piano alone!”

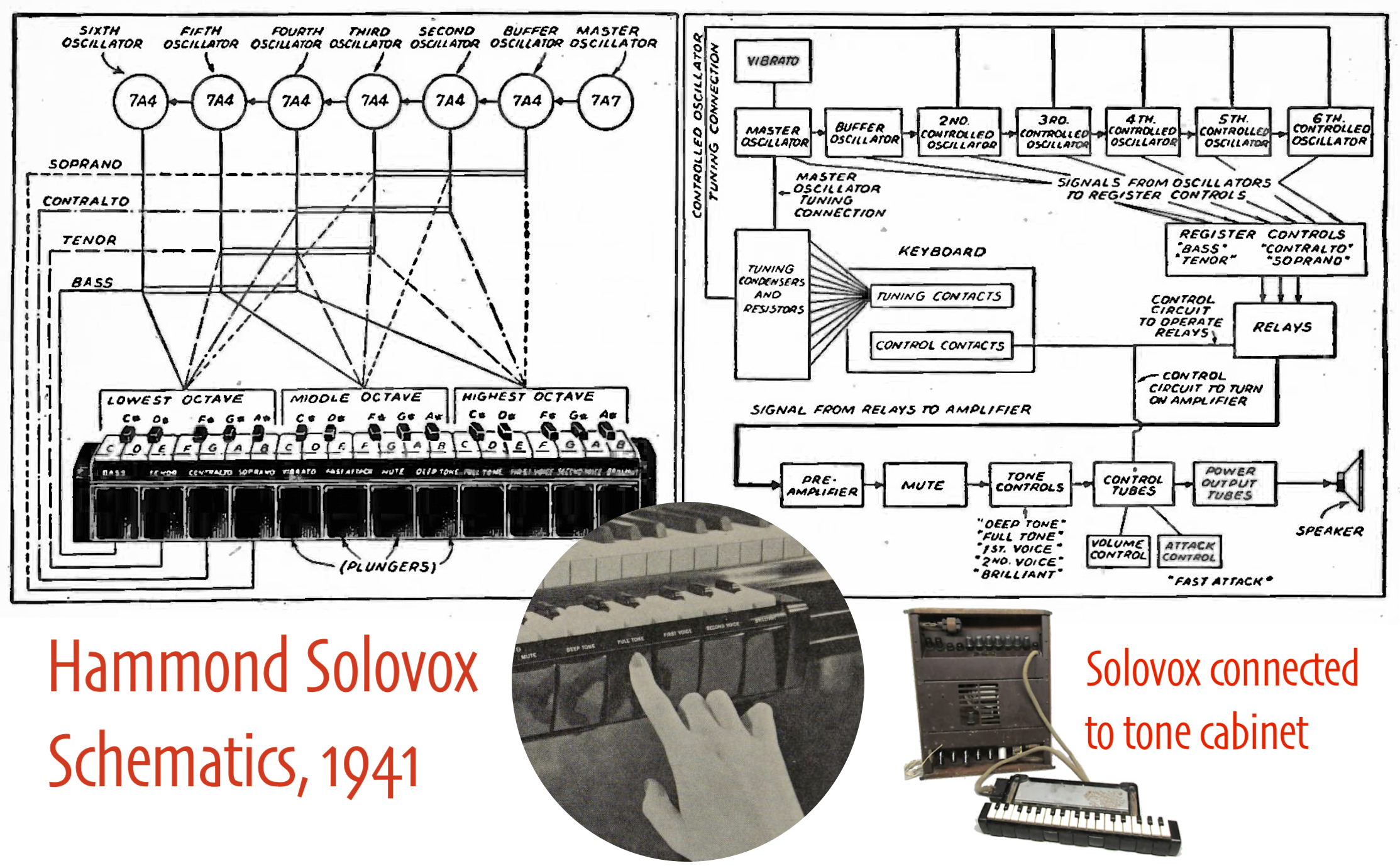

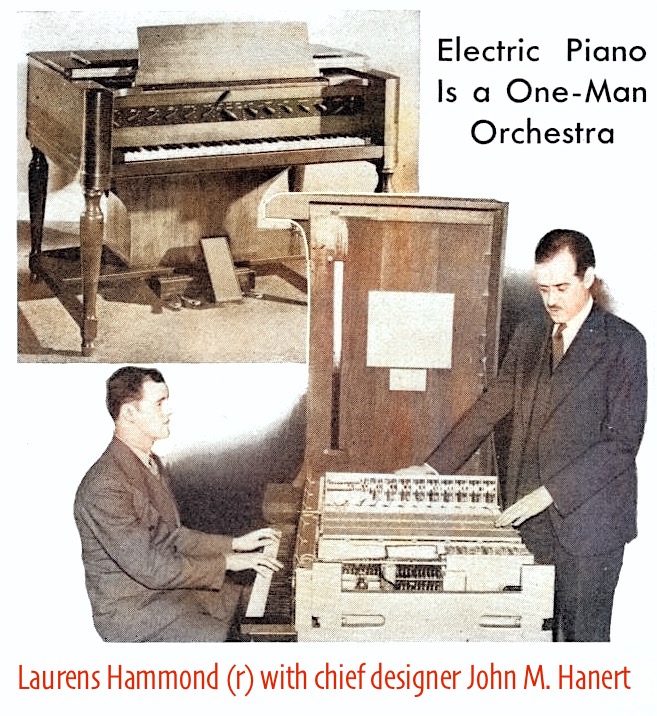

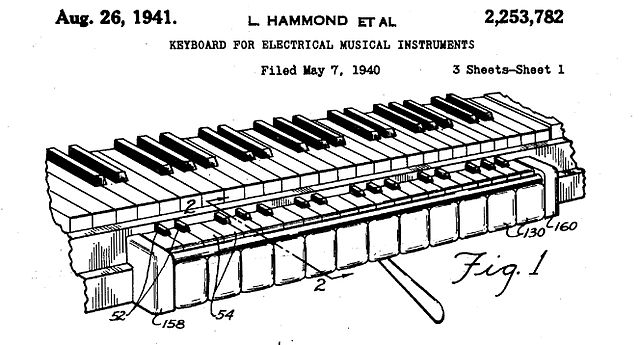

Playing the Solovox was also a hell of a lot easier than understanding how it worked. This mini monophonic organ, which could be categorized as one of the first mass-produced synthesizers (coming along shortly after Hammond’s first polyphonic synth, the Novachord), was developed by Laurens Hammond himself, assisted by his chief designer John Hanert and engineers Alan Young and George Stephens. As Mr. Hammond described it in the original 1940 patent application, the Solovox was an “exceedingly small and compact keyboard for an electrical instrument” that comprised “a plurality of octaves of keys, preferably of the same width and spacing as keys of a standard piano, but considerably shorter in length . . . Each of the keys may be utilized reliably to operate one or a plurality of tablet operated switches, which are incorporated as a structural part of the keyboard.”

Like a full-size Hammond organ, the Solovox had easy-to-read, bakelite touch tabs that allowed the player to quickly select the pitch register (bass, tenor, contralto, soprano) and tone (deep, full, first voice, second voice, brilliant) of the sound, controlled by a series of vacuum-tube based electronic oscillators. The combinations of these settings would then create different approximations of orchestra instruments when a key was pressed. Soprano tab + Deep Tone tab + Brilliant tab, for example, created Violin sound #1. Selecting Tenor + Deep Tone + Second Voice = Trumpet with vibrato.

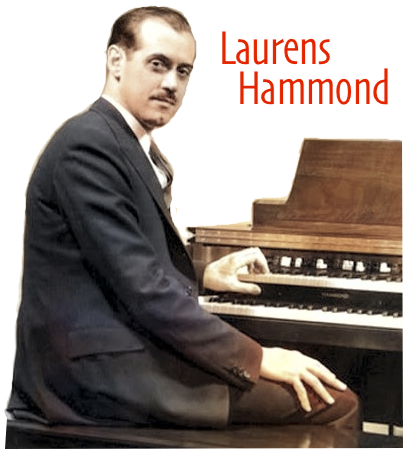

Having the tonal versatility of a giant church pipe organ in your living room was no small advancement, and accordingly, Laurens Hammond was recognized and hailed as a technological genius in his own time–a reputation he seemed fairly comfortable with from a young age.

Having the tonal versatility of a giant church pipe organ in your living room was no small advancement, and accordingly, Laurens Hammond was recognized and hailed as a technological genius in his own time–a reputation he seemed fairly comfortable with from a young age.

Like a proto Steve Jobs or Elon Musk—or perhaps more in the mold of his fellow Chicagoan Orson Welles—Hammond (1895-1973) was also sometimes viewed as a control freak with a an obsessive streak, and his ego and reputation often combined to overshadow the contributions of his equally capable co-engineers. But there was no denying his dedication to progress. Hammond spent years treating each new instrument with the care and precision of a military aircraft, and when World War II broke out, he made that metaphor literal, helping design actual military aircraft components for the U.S. government.

Long before the Hammond organ became a favorite of rock n’ roll bands in the late 1960s, Laurens Hammond was already something of a forgotten rock star in his own right; a Renaissance Man of the Art Deco era and grandfather to a whole new universe of tones that people are still toying with almost a century later.

[British pianist Billy Mayerl playing the Hammond Novachord in 1941, shortly after both the Novachord and Solovox were patented, representing two of the earliest analog synthesizers ever mass produced]

History of the Hammond Organ Company, Part I. Hammond Before the Organ

“Like most inventive geniuses,” Nation’s Business magazine reported in 1938, “Laurens Hammond is an indefatigable worker. He is extremely facile with his hands, probably a hereditary trait, for his father, a Chicago banker, was ambidextrous and could write a letter with either hand while he dictated a third.”

What that same article failed to mention is that Hammond’s father, William Andrew Hammond, was eventually investigated for loan fraud in 1897, and committed suicide after his business collapsed, drowning himself in Lake Michigan. Laurens was just two years old at the time, so any credit for his later development really ought to go more to his widowed mother Idea Louise, who boldly moved Laurens and his three older sisters across the pond in 1898 to carry on their educations at advanced schools in France and Germany.

What that same article failed to mention is that Hammond’s father, William Andrew Hammond, was eventually investigated for loan fraud in 1897, and committed suicide after his business collapsed, drowning himself in Lake Michigan. Laurens was just two years old at the time, so any credit for his later development really ought to go more to his widowed mother Idea Louise, who boldly moved Laurens and his three older sisters across the pond in 1898 to carry on their educations at advanced schools in France and Germany.

By the time the family returned to Evanston, Illinois, in 1909 (235 Greenwood Street), a now 14 year-old Laurens Hammond was multi-lingual and a budding mechanical engineering wiz. He earned his first patent by 1912 (for a low-cost barometer) and graduated with honors from Cornell University four years later. During World War I, he served with the U.S. 16th Regiment Engineers in France [pictured above in uniform], reaching the rank of captain, then took a job working for one of his war buddies at the Gray Motor Company in Detroit. The gig gave him an immediate, welcoming venue for his experimental creativity.

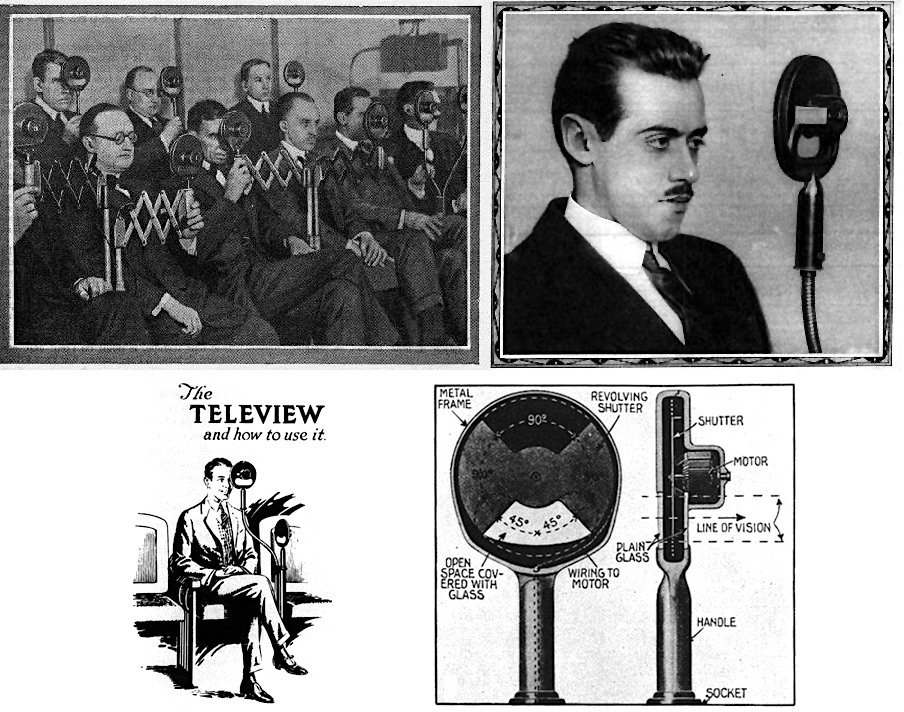

“A good field for the inventor,” Hammond remarked later in life, “is toys for adults.” Among the more than 100 patents he eventually collected across his career, many of them do indeed relate to the joys in life: driving (an early automatic transmission system he developed while still in France), movies (the Teleview steroscopic system, aka the first 3-D glasses, 1921), games (an automatic card-shuffling table, 1932), photography (camera shutter, 1942), and of course, music . . . with not only the famed electric organ, but the aforementioned first steps into synth territory with the Novachord and Solovox.

[Hammond’s Teleview 3D viewing system was well received at its debut in 1922, but proved too expensive to be a viable property during the silent film era]

The big breakthrough in Hammond’s professional career, however, came at the ripe age of 25, and actually had more to do with good punctuality than entertainment. As part of his after-hours research work for the Gray Motor Co., he developed a silent “tick-less” clock by housing its spring motor in a soundproof casing. The design captured some interest from manufacturers, and Hammond decided to set out independently, working on his clock mechanisms, radio sets, and 3-D cinema ideas from a new office in New York City.

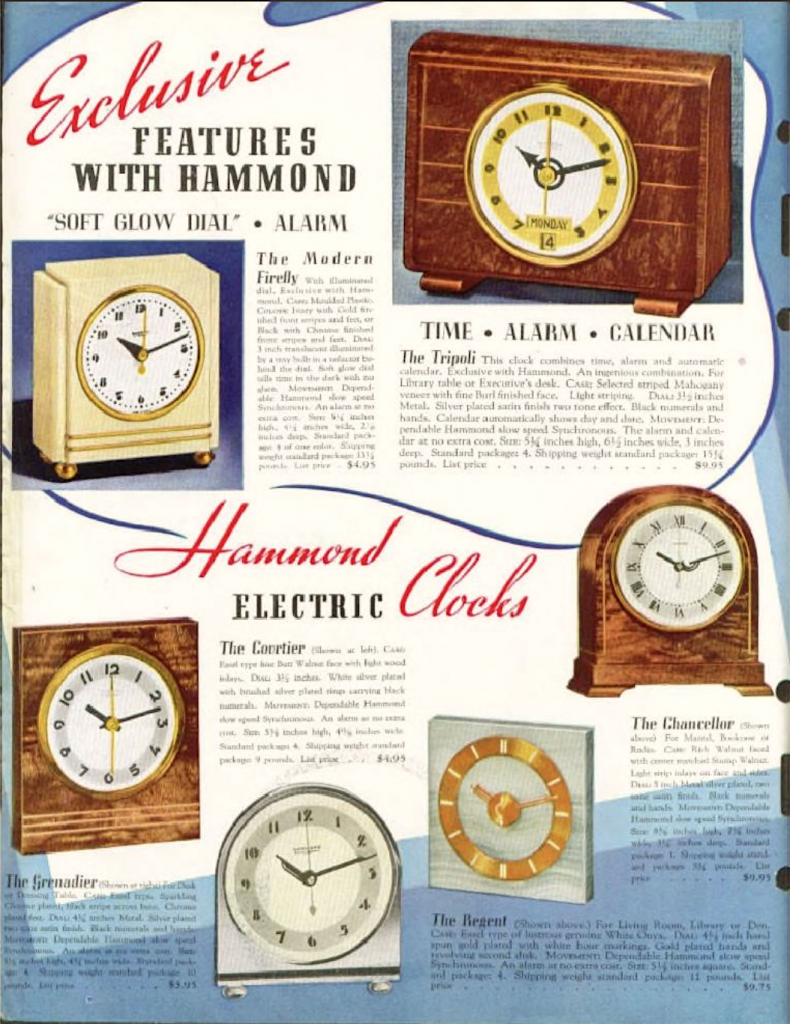

By the late 1920s, he’d patented a new “alternating-current clock” with a unique synchronous motor that quickly became an industry standard. Returning to Chicago, Laurens launched the Hammond Clock Company in 1928 to produce his new timekeepers himself. The first tiny manufacturing plant was on the second floor of a building at 4115 Ravenswood Avenue, but once the business was incorporated a couple years later, a new, bigger factory was procured at 2915 N. Western Avenue.

By the late 1920s, he’d patented a new “alternating-current clock” with a unique synchronous motor that quickly became an industry standard. Returning to Chicago, Laurens launched the Hammond Clock Company in 1928 to produce his new timekeepers himself. The first tiny manufacturing plant was on the second floor of a building at 4115 Ravenswood Avenue, but once the business was incorporated a couple years later, a new, bigger factory was procured at 2915 N. Western Avenue.

“Hammond clocks swept the country” in 1929, according to Nation’s Business. “Hammond’s simplified mechanism made mass production methods possible and other manufacturers of electric clocks still pay him royalties yearly for the privilege of using his patent devices.”

Companies that tried to copy Hammond’s designs without going through the proper royalty channels, such as Chicago’s Electric Clock Corp. of America, generally wound up in court. Hammond wasn’t shy about defending his intellectual property, and after the stock market crashed, it became an understandable matter of survival. Where once there had been over 100 electric clock manufacturers in the U.S., there were only a few dozen left by the mid 1930s.

Fortunately, Laurens Hammond was the last guy who’d ever put all his eggs in one basket. Whether through careful planning or general impatience, he was always hard at work on a dozen new things before the rest of the world had caught up with the last one.

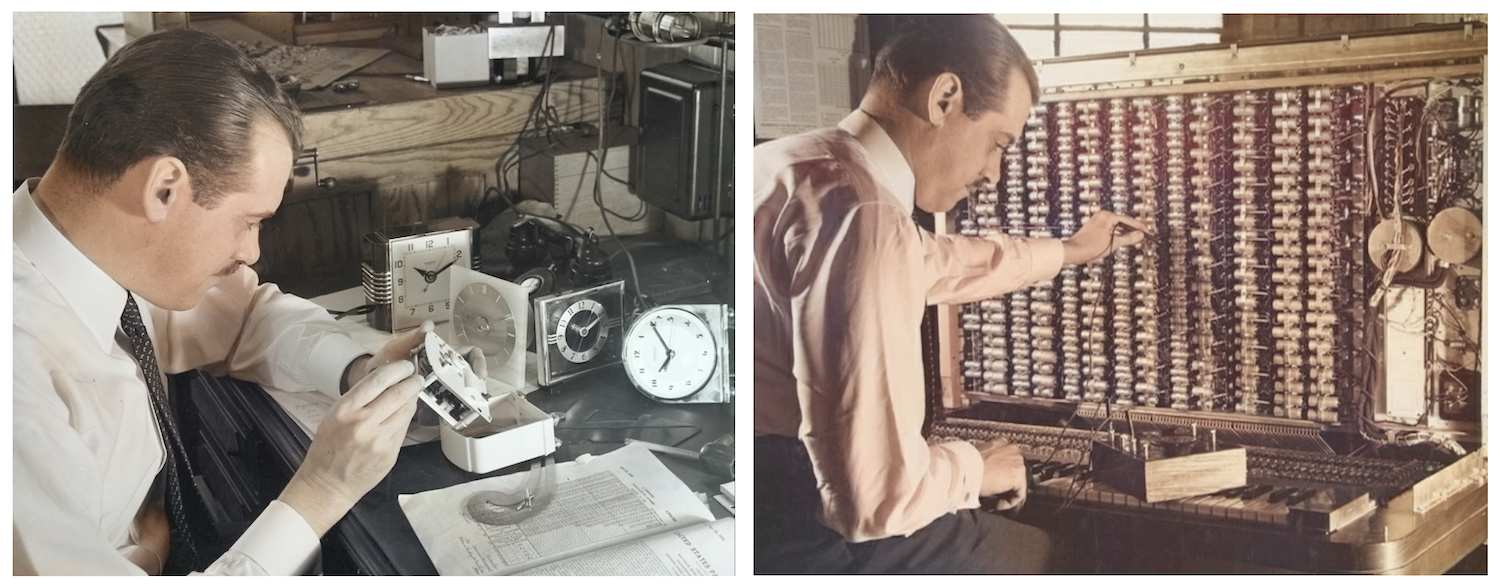

[Master tinkerer at work: Laurens Hammond, as president of the Hammond Clock Company, put painstaking effort into his line of Art Deco electric clocks, left, and by the mid 1930s, applied some of the same concepts into electronic musical instruments, including the first Hammond Organ and the first polyphonic synthesizer, the Novachord, pictured at right in 1939. From Popular Mechanics. ]

Ever since he’d first developed the synchronous motor for his clocks, Hammond had been tinkering with ways to harness the same basic principles for other types of machinery. Somewhere along the line, he recognized the potential of applying it to a musical instrument. As Nation’s Business summarized it, “Since any note in the musical scale represents a fixed number of vibrations per second—as for example, the A of international pitch, 440 vibrations—why not incite these tones with absolute fidelity of pitch, by electrical impulses?” Sure, it’s not exactly an obvious line of thinking for the majority of folks, but for one of the great minds of his era, it was just the next practical application of an existing technology.

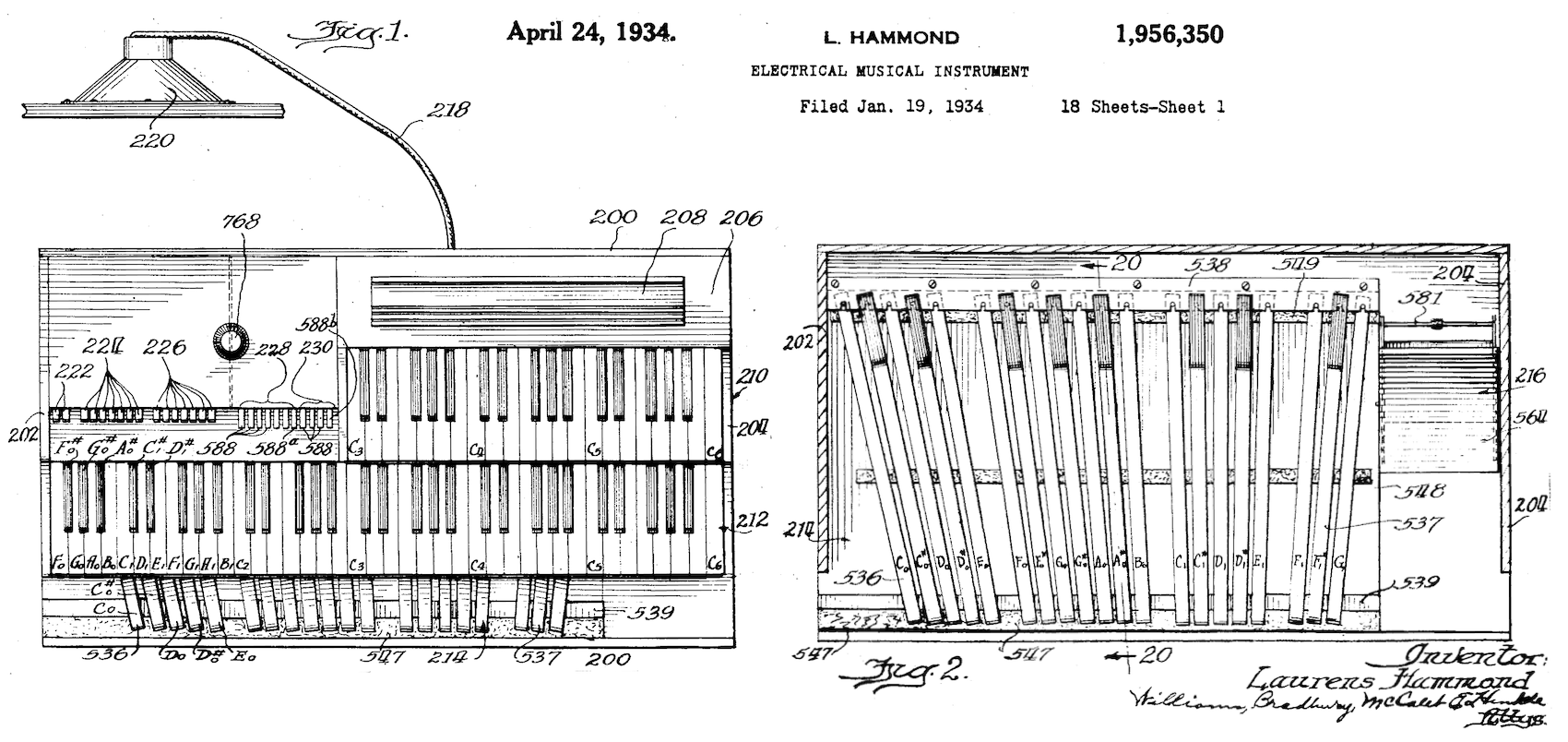

And so, in 1934, Laurens unleashed would come to be known as his engineering masterpiece—the first Hammond electric organ.

II. Tone Wheels Keep On Turnin’

The original patent identified the invention simply as an “electrical musical instrument,” but through subsequent refinements from Hammond and his longtime business partner and lead engineer John W. Hanert, the electric organ soon became synonymous with the company that manufactured it. Everybody was talking about “the Hammond.”

“Organ music heretofore enjoyed only in churches, theaters and larger auditoriums is now available in price and size for the average home,” the Christian Science Monitor reported in 1935, noting that the arrival of the electric organ had “created an upheaval within the organ-building industry.

“Unlike their older brothers with their familiar arrays of pipes, wind chests and complicated air conduits, these new organs are not only entirely electrical in operation but also in the projection of their tone. Outside of their consoles, wherein is produced the originating tones, these electrical organs employ a typical amplifier similar to that in a radio set, a talking picture or a public address system for the production of sound.”

Despite the new venture, Laurens Hammond wasn’t particularly musically inclined himself, and he relied a lot on input from his more melodious cohorts along the way. What he did understand, however, was the science of sound production and amplification, and the smell of a good business opportunity—a chance to challenge the long established keyboard hierarchy in America’s churches and stadiums. The pipe organ—an ancient, massive, and wildly expensive instrument—wasn’t practical in the electronic age, especially during an economic fallout. And while a Hammond organ couldn’t quite recreate the rich tones of a full-scale cathedral pipe organ, it came much closer than anyone would have previously thought possible, considering the price difference of roughly $1,500 vs. $70,000. Once upkeep was factored into the equation, the value gap took on canyon-like proportions.

“Its maintenance cost is that of a radio,” according to a 1936 Popular Mechanics article. “The synchronous motor which drives the tone generator consumes only ten watts from the house electric circuit; the amplifier requires about 180 watts. Beyond the keyboard, this organ bears virtually no resemblance to musical instruments of the past. Sound is produced, varied, swelled and modified electrically.

“Its maintenance cost is that of a radio,” according to a 1936 Popular Mechanics article. “The synchronous motor which drives the tone generator consumes only ten watts from the house electric circuit; the amplifier requires about 180 watts. Beyond the keyboard, this organ bears virtually no resemblance to musical instruments of the past. Sound is produced, varied, swelled and modified electrically.

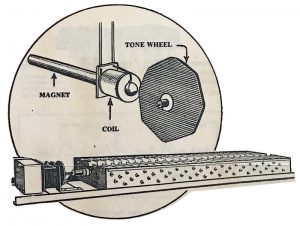

“Heart of the Hammond organ is the tone wheel. It is a metallic disk about the size of a silver dollar, rotating on a constant-speed shaft driven by the synchronous motor. Adjacent to it is a permanent magnet about one end of which a coil is wound. The tone wheel has a number of humps or high spots placed equidistant around its periphery, and as it rotates these high spots vary the field of the magnet and thus induce a tiny current in the coil. When the disk rotates at such speed that 440 high spots pass the magnet each second, a minute alternating current of a frequency of 440 is generated. . .”

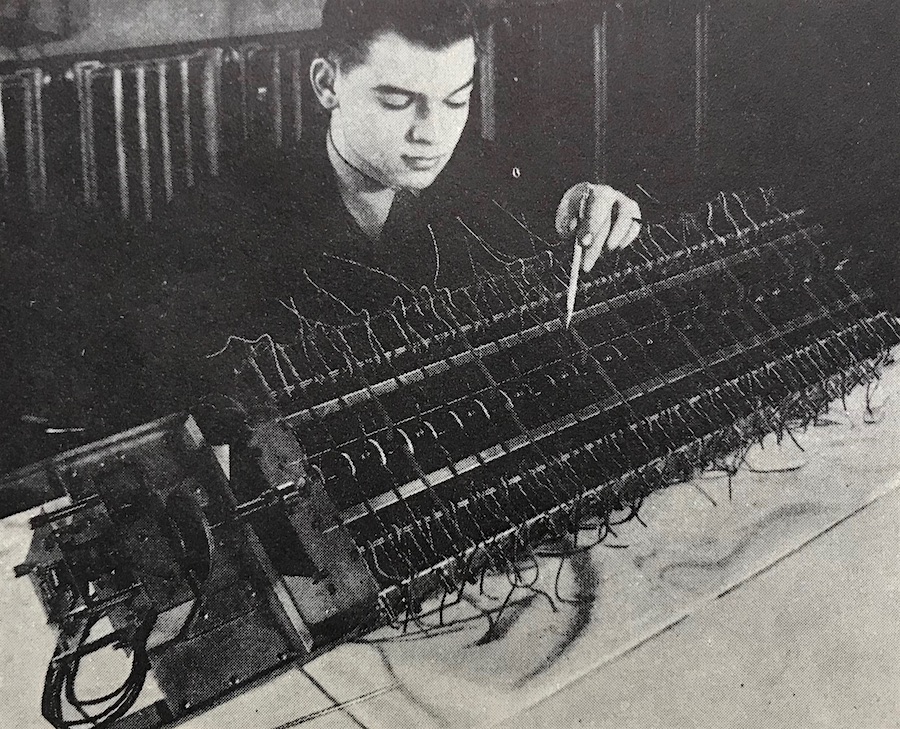

[A Hammond employee works on the tone wheel assembly of the electric organ in 1938. There were 91 tone wheels operating from a shaft driven by a synchronous motor.]

For those of us without engineering degrees, the more telling numbers are probably the tallies of electric organs shipped from the Hammond Clock Company factory each month in its first year of production, 1935 (and yes, they were still legally known as a clock business at the time):

Organs Shipped from the Western Avenue Hammond Plant in 1935:

January to April: 2

January to April: 2

May: 18

June: 47

July: 62

August: 97

September: 97

October: 134

November: 164

December: 188

Laurens Hammond and his business partners F. H. Redmond (VP) and C. E. Penny (Sales Manager) were on a corresponding nationwide victory tour throughout the year, too, starting with a big rollout during the Industrial Arts Exhibition at New York’s Radio City Music Hall. Henry Ford and George Gershwin were among the first buyers, but the instrument’s buzz and commercial appeal went far beyond industry men and professional musicians. The size, cost, consistency (it never went out of tune), and custom volume control were all revolutionary and geared toward the middle class, everyman buyer.

“We look for this type of instrument to have a market which, in normal times, would be as large as the piano market,” Hammond told the Tribune in April of 1935. “But due to the fact that this is a new market, and that there is an established demand for organs which has never been satisfied, the sales for the first several years may be very large.”

“We look for this type of instrument to have a market which, in normal times, would be as large as the piano market,” Hammond told the Tribune in April of 1935. “But due to the fact that this is a new market, and that there is an established demand for organs which has never been satisfied, the sales for the first several years may be very large.”

By September, the “Hammond Organ Co.” was running as its own subsidiary of the Hammond Clock Company. A prime showroom was purchased on the 13th floor of the Furniture Mart building at 666 Lake Shore Drive, and the Hammond factory on Western was pushed to its limits every day keeping up with orders.

“The success of the Hammond electric organ since its introduction last May has resulted in the creation of a new industry,” sales manager C. Emory Penny said at the time. “Within five months it has given employment to more than 300 men at the factories at 2915 North Western Avenue. The production schedule is behind the order total and many departments are working on three day shifts.”

III. The Pipes Strike Back

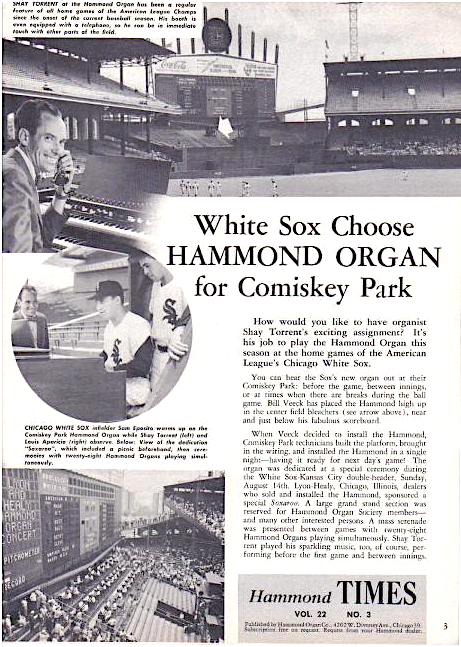

In July of 1936, a Hammond advertisement appeared in the Diapson magazine, with the headline: “Next Sunday, 390,000 people will hear the superb music of the Hammond.

“If you could drop in next Sunday at any one of 500 churches, you would understand why the Hammond Organ, within the short space of one year, has won an acceptance without parallel.”

This, in many ways, was Laurens Hammond’s first target market and proudest achievement. Having no interest in “vulgar” jazz or pop music, he saw his instrument as the evolution of—and replacement for—the church pipe organ. And many cost-conscious churches during the Depression were more than happy to concur. With the media largely embracing the trend, too, the only frustration with the Hammond revolution seemed to be coming from one particular community: the pipe organ loyalists. Those damnable traditionalists!

This, in many ways, was Laurens Hammond’s first target market and proudest achievement. Having no interest in “vulgar” jazz or pop music, he saw his instrument as the evolution of—and replacement for—the church pipe organ. And many cost-conscious churches during the Depression were more than happy to concur. With the media largely embracing the trend, too, the only frustration with the Hammond revolution seemed to be coming from one particular community: the pipe organ loyalists. Those damnable traditionalists!

Highly accomplished organist Porter Heaps, who led many of the demonstrations of the new electric organ across the country, was caught in the crossfire perhaps more than anyone.

“For a while, I was labeled a deserter by the long hair musicians and somewhat of a mongrel by the pipe organ musicians,” Heaps later told the Tribune.

Porter Heaps, aka “Mr. Hammond Organ,” plays on a 1957 company promotional record:

This dynamic really came to a head in the early months of 1937, as representatives of the Pipe Organ Manufacturers Association filed a complaint with the Federal Trade Commission, taking issue with a litany of Laurens Hammond’s claims about his product. They argued that Hammond advertisements blatantly misled the public by suggesting an electric organ could reproduce “the entire range of musical tone colors” and a “range in harmonics” equal to a pipe organ. In fact, even the very use of the word “organ” was questionable at best.

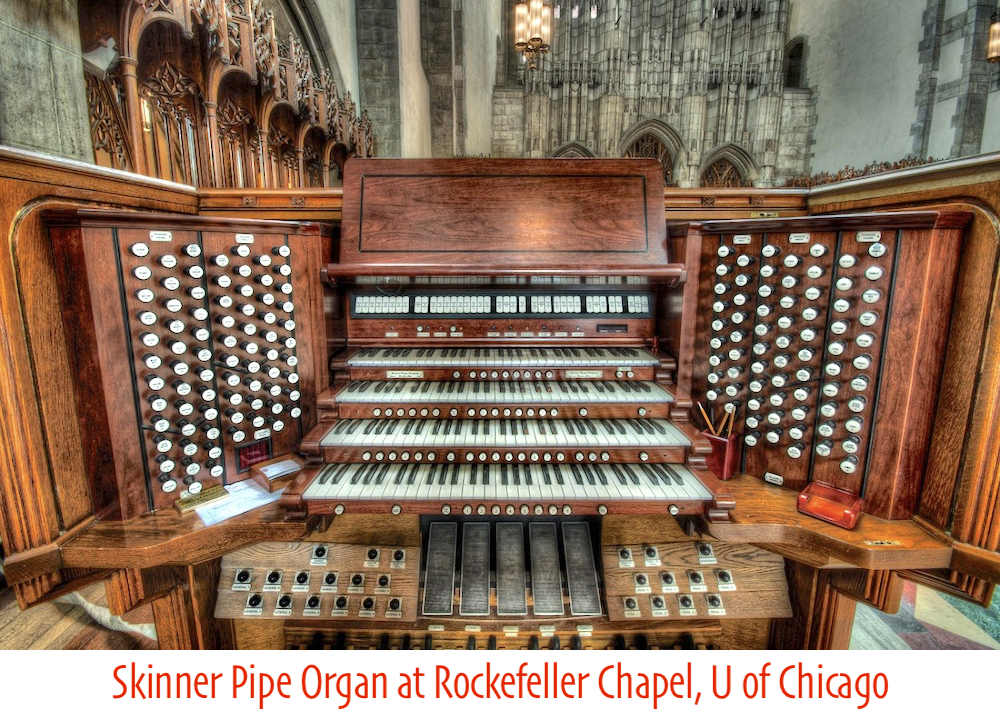

Rather than sweat the threats, Hammond predictably welcomed the challenge, a firm believer that any publicity was good publicity. He stood by his bold claims, and organized more demonstrations, culminating in a now legendary showdown of electric organ vs pipe organ, held on March 11, 1937, at the Rockefeller Chapel on the campus of the University of Chicago.

With Porter Heaps at the keyboard and two judging panels in attendance—a group of 15 university students and another of 10 professional musicians (including six pipe organists and conductors Daniel Saidenberg and Ebba Sundstrom)—a $1,200 Hammond organ and several tone cabinets went into audio combat with one of the largest pipe organs in the world; a $75,000 beauty built a decade earlier by the famed organ designer Ernest M. Skinner.

With Porter Heaps at the keyboard and two judging panels in attendance—a group of 15 university students and another of 10 professional musicians (including six pipe organists and conductors Daniel Saidenberg and Ebba Sundstrom)—a $1,200 Hammond organ and several tone cabinets went into audio combat with one of the largest pipe organs in the world; a $75,000 beauty built a decade earlier by the famed organ designer Ernest M. Skinner.

According to an account years later by John Majeski, Jr. in Music Times, Hammond’s tone cabinets “were concealed amid the pipes of the traditional instrument and screens hid the consoles of both organs so that the audience could not see which was being played.”

Both juries were given pencil and paper and asked to note whether the thirty odd compositions heard were played on the pipe or Hammond organ. The test concluded with a note of harmonic partials called ‘Jack’ and another note of tempered partials called ‘Jill.’ The students were right on an average of fifty percent. Obviously they couldn’t tell the difference. The musicians did better and worse with errors ranging from 10 to 90 per cent.”

For Laurens Hammond, this was a clear victory, even if the opposition argued that the whole test—with Porter Heaps at the keys—was rigged from the outset. In fairness, Heaps almost certainly emphasized higher reedy flute tones in the performance, since Hammond organs faired considerably better in that department (fully unleashed in its lower registers, a monster pipe organ would not be mistaken for a friendly home console). In any case, the FTC eventually settled the issue a year later, allowing Laurens to call his instrument an “organ,” but forbidding any further use of the term “infinite tones.” With victory in America’s houses of worship, focus could return back to American houses.

[Early advertisements for the Hammond Organ in the late 1930s were already aiming directly at middle class families, with women and children often highlighted. “Children develop a deeper appreciation of music with a Hammond organ in the home.”]

IV: A Life of Its Own

By 1938, the Hammond Clock Co. had officially become the Hammond Instrument Company, a thriving enterprise bucking the odds in the final years of the Depression. True to form, Laurens Hammond and his team were thoroughly disinterested in merely enjoying the success of their first few creations. They continued to relentlessly push the envelope, turning much of their attention over to vacuum tube based instruments in the late ’30s, leading to the unveiling of the Novachord in 1939 and the Solovox a year later. Had it not been for the more pressing concerns of world politics, Hammond may well have remained the preeminent name in synthesizers, as well.

Instead, as noted earlier, Laurens Hammond joined the war effort. After Pearl Harbor, when most manufacturers were forced to shift away from their own specialties to do the bidding of the U.S. Government, Hammond instead volunteered his factories for the production of various military devices of his own personal design, including automatic pilot controls and a type of “glide bomb control” that was the forerunner for modern guided missiles.

Instead, as noted earlier, Laurens Hammond joined the war effort. After Pearl Harbor, when most manufacturers were forced to shift away from their own specialties to do the bidding of the U.S. Government, Hammond instead volunteered his factories for the production of various military devices of his own personal design, including automatic pilot controls and a type of “glide bomb control” that was the forerunner for modern guided missiles.

With attention shifted to these more pressings needs, the war would ultimately spell the demise of the Novachord, which was only produced from 1939 to 1942 (a little over 1,000 were made in total). Production of our museum artifact, the Solovox, was also halted for several years, but started up again after the war, eventually sputtering out by 1950.

By contrast, sales of the company’s tone-wheel organs continued to gain ground on the traditional home piano market. The more successful and diversified the Hammond organ line became, however, the more challenging it was for Laurens Hammond to maintain his vise-like grip on his business and its preferred customer base.

While ads still preached to churches and cozy family parlor rooms, the organ’s unprecedented sonic versatility had, by no surprise, found a growing audience in that dreaded genre of “popular” music. If Laurens found the trend vulgar at first, though, he probably didn’t turn his nose up at the cash windfall. And when popular organists like Ethel Smith started showing off the Hammond’s capabilities on the silver screen in the 1940s, the free advertising only helped boost mainstream public awareness and demand even more.

[Organist Ethel Smith showed the Hammond’s popular appeal in the 1944 film “Bathing Beauty”]

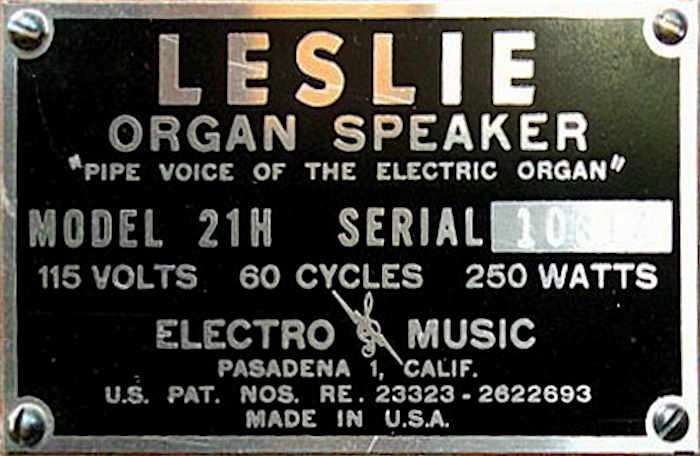

An unexpected development that Hammond was notably less willing to embrace was the emergence of the new Leslie speaker, created in the 1940s by another Illinois native, Donald Leslie.

To many musicians’ ears, the Hammond organ was at its best, bar none, when paired with a Leslie. Unfortunately, since the Hammond Instrument Company also manufactured its own speakers and had no direct affiliation with Leslie and his patents, Laurens Hammond didn’t dig this supposed symbiosis. Instead, he took aggressive action to elbow out the new kid on the block, even refusing to do business with distributors who carried Leslie speakers.

Neither Hammond nor Leslie ever backed down on their personal beef, even as most organists continued to marry their inventions. Ironically, both the Hammond and Leslie brands are now owned by the Suzuki Musical Instrument Company.

The Leslie feud showcased how Hammond—even to the potential detriment of his own product—always sought total and absolute control of the marketplace, from the centerpiece items to the accessories/components, to the sales floor itself. It’s not that he didn’t work well with others; he simply didn’t trust his brand to strangers.

On the manufacturing end, this meant drastic actions like opening an entire factory dedicated to woodworking (located at 5008 W. Bloomingdale Ave.), rather than counting on an inferior outsourced supply. And on the sales end, the company’s “selective distribution policy” held independent organ dealers up to unusually strict standards of operation, with various regulations on quotas and selling techniques. Some dealers rebelled, but most quietly counted their earnings.

[By the 1950s, there were about 80 licensed Hammond Organ showcase “studios” in operation worldwide, and all were required to adhere to corporate policies out of Chicago]

The best behaved Hammond dealers could earn themselves a designation as an official “Hammond Organ Studio,” licensed by the company itself to help educate the public on its instruments and how to play them. These were located everywhere from Miami, Florida to Spenard, Alaska; Pasadena, California to Bangor, Maine.

“Almost everyone has some degree of musical talent but doesn’t realize it until it is brought out,” read a Hammond Studios ad in the 1950s. “The Hammond Organ Studio invites anyone doubting their own musical ability to try it out by learning to play. . . . Teaching and practice facilities of the Studio assures the purchaser he can play a Hammond Organ before he buys it.”

Laurens Hammond didn’t just have a vision for how an electric organ could look and function; he also had a vision for how it would be played and its long term place in the culture. It was a heavy-handed approach, but the clever and sometimes cutthroat strategies of “the boss” did help the Hammond Instrument Company survive both the Depression and World War II with wind in its sails.

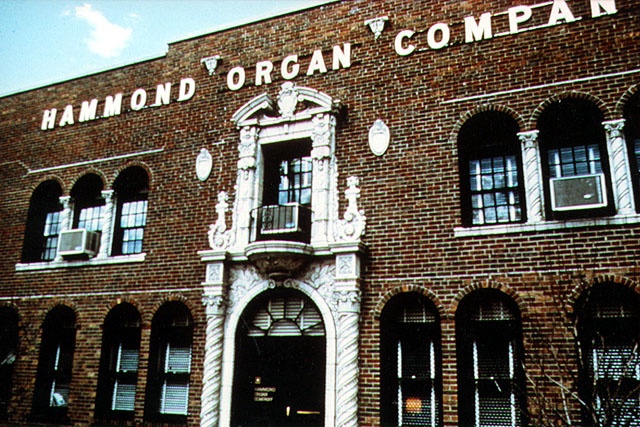

[Above: The facade of the former Hammond plant at 4200 W. Diversey Ave. c. 1970s]

[Below: The same Diversey building today, which has recently been adapted for art studio space]

V. To B3, Or Not to B3

In 1949, a new main factory space opened up at 4200 W. Diversey Avenue—a building that would remain the Hammond headquarters right up until the company’s final days.

A few years later, in 1953, the official name of the business was changed again, this time from the Hammond Instrument Co. to the Hammond Organ Company. Attempts at breaking into other instrument manufacturing had been meager at best, and Hammond clocks were less than an afterthought, so it was the logical move.

A few years later, in 1953, the official name of the business was changed again, this time from the Hammond Instrument Co. to the Hammond Organ Company. Attempts at breaking into other instrument manufacturing had been meager at best, and Hammond clocks were less than an afterthought, so it was the logical move.

After 20 years in the business, Laurens Hammond was there to oversee the completion of the new complex on Diversey, but he wouldn’t work there for long. To the surprise of many, he relinquished the presidency in 1955 to focus on research. And while he maintained the chairmanship of the business and watched it triple in net worth from about $5 million to over $17 million by the end of the 1950s, he somewhat humbly and quietly retired for good in 1960 at the age of 65, resettling in Cornwall, Connecticut.

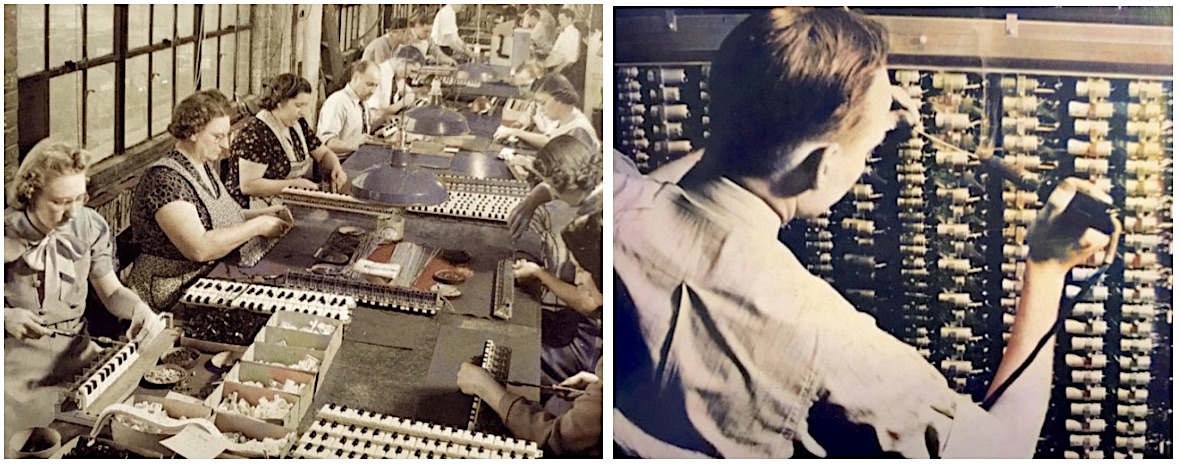

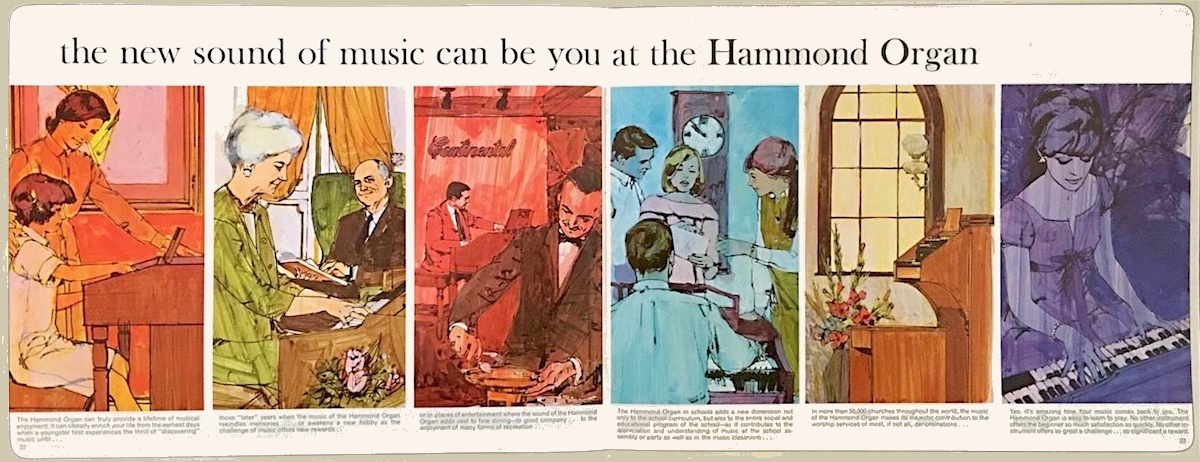

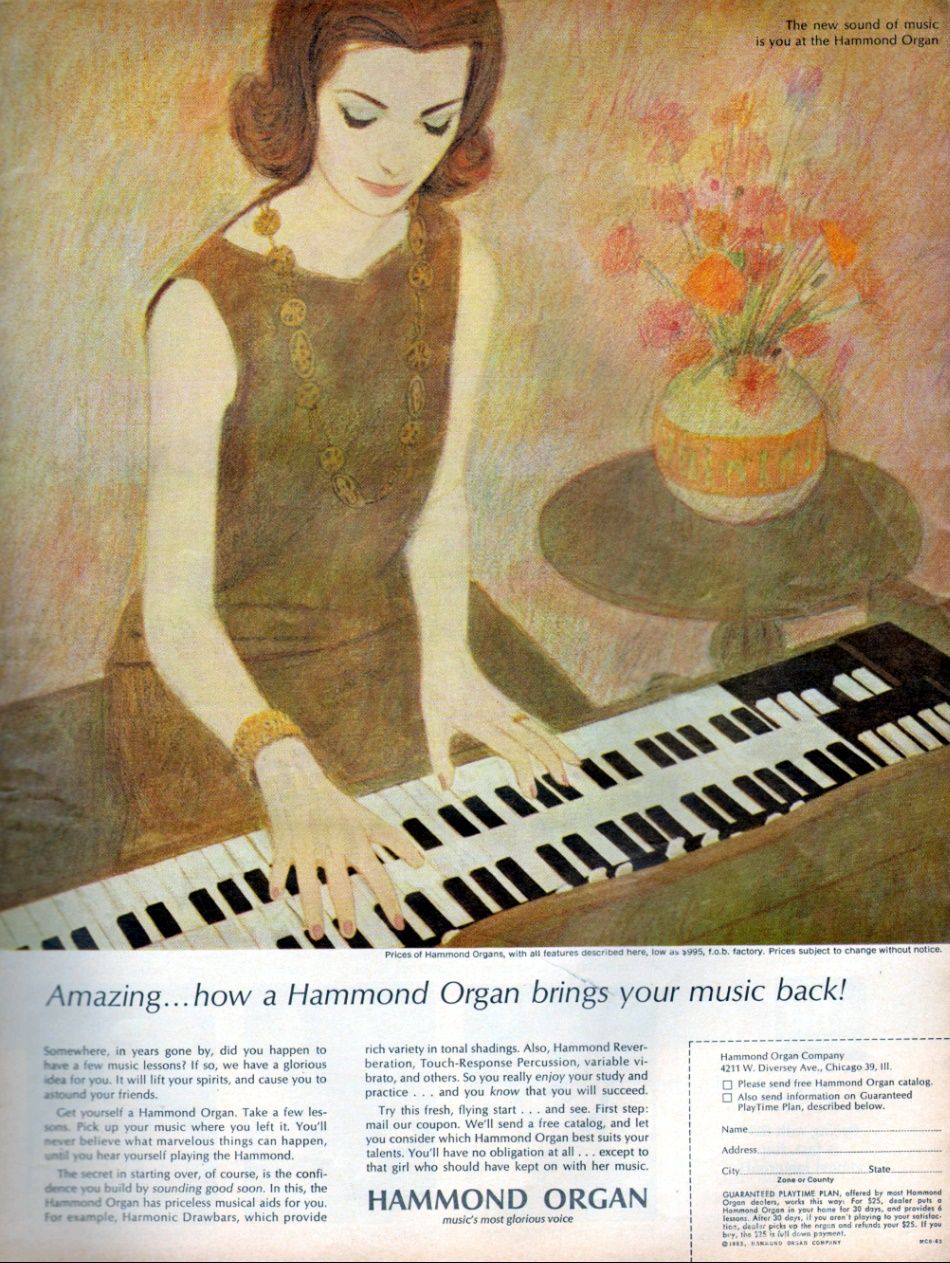

[Above: Workers in the Hammond Organ factory at 4200 W. Diversey assembling keyboards (left) and building a relay cabinet, 1950s. Below: 1964 advertisement: “The new sound of music can be you at the Hammond Organ”]

During the Hammond Organ Company’s peak post-war years, its deep connection with Chicago is hard to oversell. Besides the main Diversey facility, there were more than a half dozen other plants in operation around the city, employing more than 1,000 men and women. This included the original Western Avenue plant, the aforementioned woodworking plant at 5008 W. Bloomingdale Ave. (1937-1977), a holdover wartime plant at 4737 N. Ravenswood Ave., chord organ plants at 2335 W. St. Paul St. and 4046 N. Rockwell Ave. (1950s), sub-assemblies production at 4249 N. Knox Ave., and a tone wheel generator factory in Melrose Park at 1740 N. 25th Ave (1956-1976).

That Melrose Park building was also home to the famous B3 organ, which evolved from a cheesy Lawrence Welk prop into one of the defining sounds of ‘60s jazz and psychedelic rock n’ roll. They literally don’t make ‘em like that anymore.

That Melrose Park building was also home to the famous B3 organ, which evolved from a cheesy Lawrence Welk prop into one of the defining sounds of ‘60s jazz and psychedelic rock n’ roll. They literally don’t make ‘em like that anymore.

By the time of Laurens Hammond’s death in 1973, the Hammond Corporation was a full-on international powerhouse, with additional manufacturing campuses in Missouri, Massachusetts, Canada, and as far away as Japan. The cheaper electronic keyboards coming out of the Far East would, of course, soon spell doom for the company. But for a while—riding the wave of the organ’s prog-rock “bad ass” period—the future seemed fairly hopeful.

All along, the Hammond factories maintained many of the high standards introduced and always demanded by the company founder, albeit updated with the aid of new advanced machinery. A bold three-year product warranty was added to all sales in the ’70s, and company president Donald R. Sauvey seemed to subscribe to the theory that quality would remain of greater importance to the public than price.

“Our efforts have focused on creating organs that not only have unique features but also provide long-term service that makes for happy customers and even happier dealers,” Sauvey told the Music Trades in 1978. “Our motto is: out of the box . . . onto the floor. By that we mean in most cases the dealer doesn’t have to invest time and money in checking out the organ before making it available for sale.”

[Workers at the Hammond factory on West Diversey, 1970s]

[Workers at the Hammond factory on West Diversey, 1970s]

Living up to the old Laurens standard meant vigilantly screening every parts vendor, holding components up to military specifications, testing at every stage of the sub-assembly process using “advanced” and highly expensive 1970s computers, and passing a final quality assurance test for sound, electrical and mechanical functions. According to the company’s V.P. of Operations at the time, John Tierney, a typical organ had to pass nearly a thousand separate tests before shipping out to dealers.

“I suppose that most manufacturers claim product reliability,” Tierney said, “but the proof of the pudding is in the eating. Our dealers will tell you that today the Hammond quality is unbeatable.”

And yet, less than a decade later, one of the great musical success stories in American history was over. The Hammond company, while well equipped with engineering and sales talent from around the world, didn’t have another Laurens Hammond at its disposal. As the synthesizer age grabbed hold of the ’80s, the company was buried by the next wave of cheap keyboard technology, and the Chicago business collapsed by 1986. Throughout that spring, several auctions were held at the Diversey plant, selling off the remaining stock of organs and the various machines and computers that had been part of the finely tuned operation. It was, one can imagine, quite a depressing time.

And yet, less than a decade later, one of the great musical success stories in American history was over. The Hammond company, while well equipped with engineering and sales talent from around the world, didn’t have another Laurens Hammond at its disposal. As the synthesizer age grabbed hold of the ’80s, the company was buried by the next wave of cheap keyboard technology, and the Chicago business collapsed by 1986. Throughout that spring, several auctions were held at the Diversey plant, selling off the remaining stock of organs and the various machines and computers that had been part of the finely tuned operation. It was, one can imagine, quite a depressing time.

Technically speaking, the Hammond brand never really died, as organ production carried on under the new ownership of Japan’s Suzuki Corporation. Much like latter period Schwinn bicycles, some purists were never inclined to accept the imported iteration of Hammond, or the new “sophisticated digital technology” the company adopted in place of the old clunky tonewheel consoles. To the credit of Suzuki chairman Manji Suzuki, however, the acquisition of both Hammond and Leslie was motivated by a genuine respect for the legacies of those brands, and today, at least some manufacturing is still done at a Hammond USA plant in nearby Elmhurst, IL.

“We’ve consulted the original cabinet blueprints and specifications to insure our new organs look like they are members of the same family,” claims the current Hammond corporate site. “There’s a straight line of development from 1934 to the present day. Mr Hammond’s and Mr. Leslie’s original ‘recipes’ are the guiding lights.”

Epilogue: An Additional Artifact

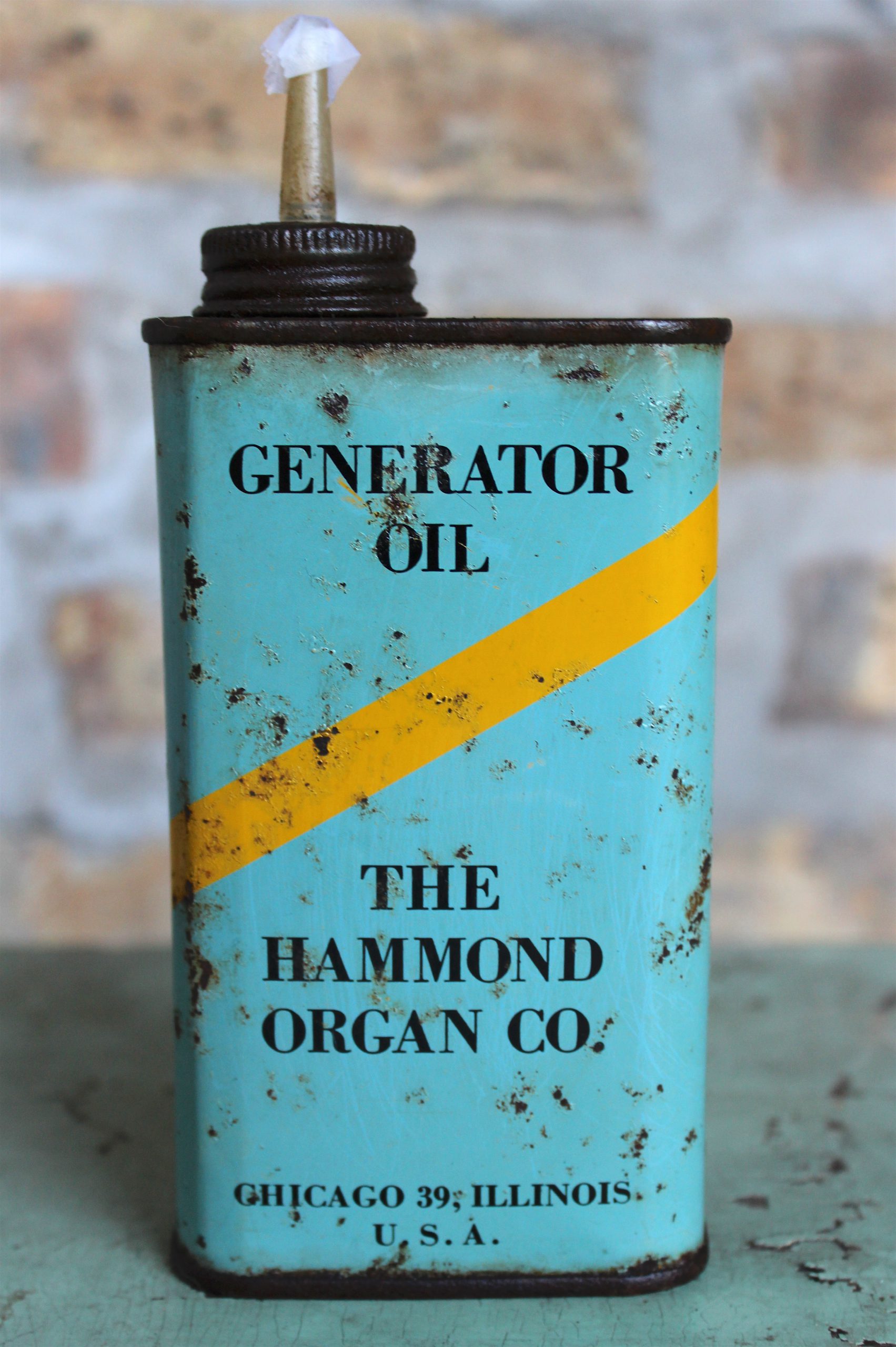

Our museum collection also includes a vintage can of Hammond Generator Oil, probably dating from the late ‘50s or early ‘60s. The 8oz can—which still has a fair amount of oil in it—was “prepared and organized” for Hammond by E.F. Houghton & Co., a Philadelphia company that’s been around since the 1860s and presently still calls itself “the largest metalworking fluids company in the world.”

Our museum collection also includes a vintage can of Hammond Generator Oil, probably dating from the late ‘50s or early ‘60s. The 8oz can—which still has a fair amount of oil in it—was “prepared and organized” for Hammond by E.F. Houghton & Co., a Philadelphia company that’s been around since the 1860s and presently still calls itself “the largest metalworking fluids company in the world.”

According to many believers in the tonewheel gospel, these little blue cans with the yellow stripe were and still are the ONLY guaranteed way to keep an old B3 purring like a kitten, no matter its vintage. The specialized lubricating formula, they say, meets the exact required viscosity for the instrument’s elaborate capillary oiling system. Going with an off-brand alternative can mean the difference between an all-night psychedelic jam session and a very un-groovy silence.

Taken from the back of the can itself, here are the Hammond Company’s very important tips for using your generator oil the right way . . . the Hammond way:

“All generator bearings are lubricated by this oil being put into cups above generator. Fill each cup ¾ full once a year. Cups act as funnels. Do not attempt to keep them full.”

A fine metaphor for life.

Since you’re still here, check out this terrific video tour of the Hammond factory from the 1950s:

[Front entryway of the refurbished ex-Hammond building at 4200 W. Diversey Ave.]

[Booker T and the MGs perform Green Onions in 1967 with Booker T on the Hammond B3]

Sources:

Chicago History Museum Archives

Hammond As In Organ: the Laurens Hammond Story, by Stuyvesant Barry

Workshop 4200 (the former Hammond factory space on W. Diversey)

“Shake Well Before Selling” – The Music Trades, October 1978

“Electric Pipeless Organ Has Millions of Tones” – Popular Mechanics Magazine, April 1936

“Electricity Makes the Family Organ Hum” – Nation’s Business, Feb 1938

“Newest Pipe Organ Ceases to Be a Pipe Organ” – The Christian Science Monitor, Oct 11, 1935

“An Analysis of the Hammond Clock Co. Common Stock” – Hartley Rogers & Co., Inc., 1936

“Pipeless Organ, Electric, Is Put on Market Here” – Chicago Tribune, April 22, 1935

“Hammond Organ Co. Gets Space in Tower of Furniture Mart” – Chicago Tribune, Sept 15, 1935

Hammond Times, Vol. 19, No. 2, 1957

“The Story of Hammond Organ: 25 Years of Leadership,” by John Majeski, Jr., Music Trades, 1960

“Porter Heaps, ‘Mr. Hammond Organ” – Chicago Tribune, May 13, 1999

Archived Reader Comments:

“So many Chicago north suburban restaurants in the 1950s, like Vosnos in Morton Grove, offered Hammond organ music during dining hours making meals so memorable.  ” —Dave, 2020

” —Dave, 2020

“I bought a Hammond L-122, in 1966 for a band. I got in Church in 1968 and have been playing it for close to 50 years with three tubes replaced. I also own a newer version at home ; the T-582c all vintage. This is truly a more than lifetime organ. ” —Barry Foust, 2018

” —Barry Foust, 2018

A bit sad, that the innovator of Hammond Organ playing, Jimmy Smith, is not mentioned.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jimmy_Smith_(musician)

My father brought home a Hammond organ one day. It had a rhythm box with knobs to select the different dance beats samba, rhumba … It also had a built-in Leslie speaker. It had foot pedals on one side and a volume pedal on the other side. My neighbour worked at the Hammond Organ store in a mall you could see from the Queen Elizabeth Way on the way to Port Credit. She gave me lessons. I was 12 years old.

Fact is that Green Onions was actually recorded on a Hammond spinet model, most likely an M-3. The M and L spinets are often referred to as ‘baby B-3s’.

Hello, I am an Italian who has always been passionate about the Hammond organ and the universe of history, myth and culture that revolves around this wonderful instrument. I read the article you published with keen interest and as a citizen of old Europe I noted the absence of references to the numerous and no less active overseas productions. As an average lover, but a true enthusiast, I am, in fact, aware of the existence of plants that over time and, starting from the 40s, have produced in England, Belgium and Italy (as well as in other continents).

Please consider this writing as a simple modest contribution and a starting point for further study.

Finally, as (enthusiastic) owner of some vintage H. models, I take this opportunity to ask if it is possible to accurately trace the date of manufacture of an instrument, in what way or by which institution.

Thank you for your attention and for the work done.

Giuseppe Chinzi

Dear Author

We have here a discussion among us Hammond-fans, the question is exactly at how many (and where, under what names) subsididiaries actually manufacured H. organs in other countries? In their hisorical story in he Hammond Museum they mention a couple of them, but their list is not complett, they give just some examples. We ‘d like to know specially if H.organs had been produced also in South Africa, if they had eventually such a subsidiary there?

-And in your story you don”t mention that between Hammond and Suzuki times there was an “interregnum”, when all Hammond rights went to an australian company, who tried to keep up with production before the Suzuki take-over..?

-yours sincerly: Victor Gottesmann

Hello from France,

I come to you because I am a reseller and technical station repairing renovation and rental of Hammond organs Leslie cabins and Rhodes pianos.

I have a problem with the reference Amphenol 86CP9 which is a connector plug found on Leslie 760 cabin cables.

The HAMMOND market is important in France.

My customers who have old cables want to change these connectors but don’t want new connectors like the Socapex, they want the original.

On a concert tour, if there is a problem, it is easier to find the original cable and not a custom cable with different connector plugs.

I am desperately looking for a supplier, a wholesaler from whom I can order Amphenol male and female plugs.

Waiting to hear from you.

With my kindest anticipated thanks

KIND REGARDS

ERIC MORATA

manager of MPO

April 2, 2021

I have a Model M-3 Spinet Model with Percussion. One day we smelled like something was burning and finally got n the living room and the closer we got to the organ, we knew it was the organ. We found the cord had burned in two places right down to the wires. We immediately unplugged it from the wall. A friend came and removed the cord and installed one he had but when we turned the organ on, there was all kind of noises so immediately turned it off. Can one purchase a new power cord for this model? Do you know a repairman in my area?

Your power supply failed. The capacitors need replacing. Your power cord is fine. Any decent electronics tech can fix it for you. Not sure where your located, but I’m sure there’s a tech nearby who can help you out.

Good morning,

In my possession I have a lap organ. Its old. My great great grand father used it in performance with a violinist. I am looking for someone to repair the belows. Can you help me maybe. THANK YOU.

I can send photos if you wish.

Sincerely

Ken Maddigan

Middleboro MA.

508 740 2874

EMAIL

KMADDIGAN @COMCAST.NET

I am looking for a good home for a Hammond spinet organ with tubes. Can you help me?

I would like to know if Hammond Organ parts are available. Please contact me if you can help me get a PRESET SWITCH for my Hammond Console 820165….the little square button that you press IN to activate. My #3 Preset switch is broken = won’t engage & the light won’t come on either. Everything else on my organ is working fine. I’m also looking for an external leslie #750.

The comment about modern Hammonds being a “shadow” is disingenuous. Our artist roster of 400 of the greatest keyboard players on the planet would tell you why. Our modern instruments are bona fide in their allegiance to the antique classics.

And we’re still based in the Chicago Area.

Thanks, Scott. I appreciate the feedback. I added some detail about the current company’s dedication to the original sound and aesthetic.

How can I identify the Model # on a Hammond Organ purchased in 1946? Where would the model number be located? Thank you.