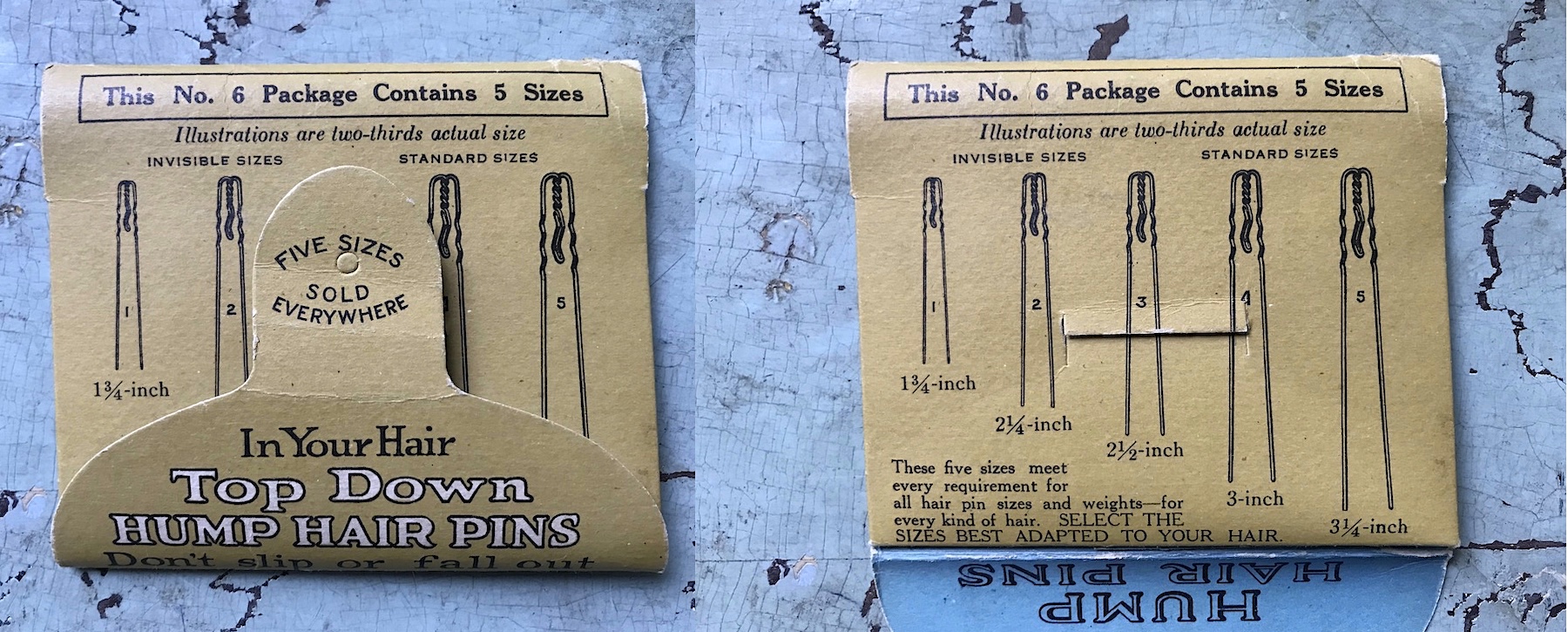

Museum Artifact: Hump Hair Pins Set No. 6, 1920s

Made By: Hump Hair Pin MFG Co. / Gaylord Products Co., 1936 S. Prairie Ave., Chicago, IL [Near South Side]

“Ingenuity is not always confined to skyscrapers and bridges. The inventor often achieves fame through smaller means. The Hump hairpin is a new invention ingenious enough to secure a niche in the woman’s hall of fame for the man who devised it.” —Hump Hair Pin advertisement, 1916

The man behind the Hump hairpin, as he would have been the first to tell you, was Solomon H. Goldberg—a fascinating, fast-talking character whose talent for selling and self-mythologizing almost certainly eclipsed any legitimate engineering chops he brought to the table.

The man behind the Hump hairpin, as he would have been the first to tell you, was Solomon H. Goldberg—a fascinating, fast-talking character whose talent for selling and self-mythologizing almost certainly eclipsed any legitimate engineering chops he brought to the table.

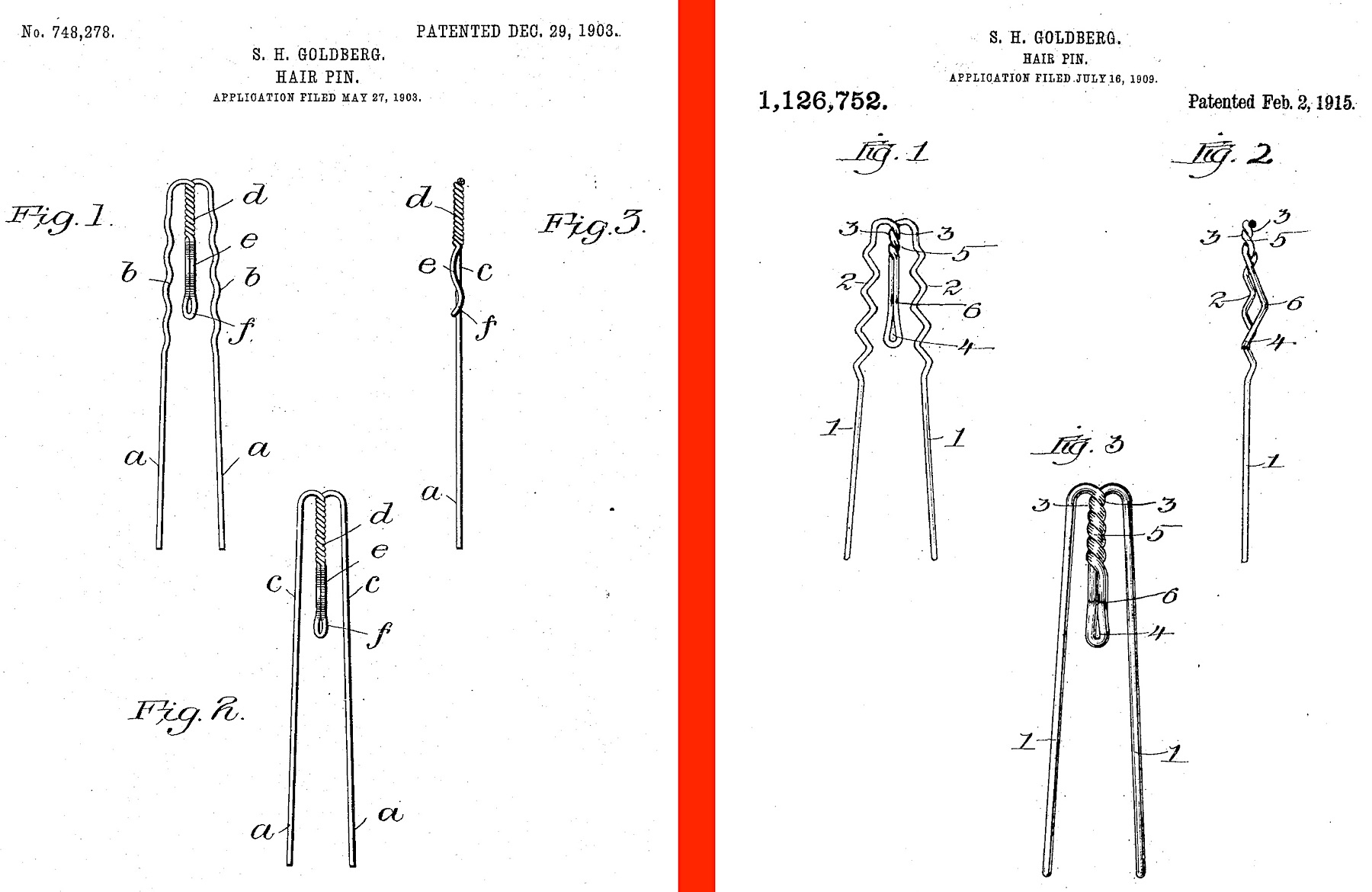

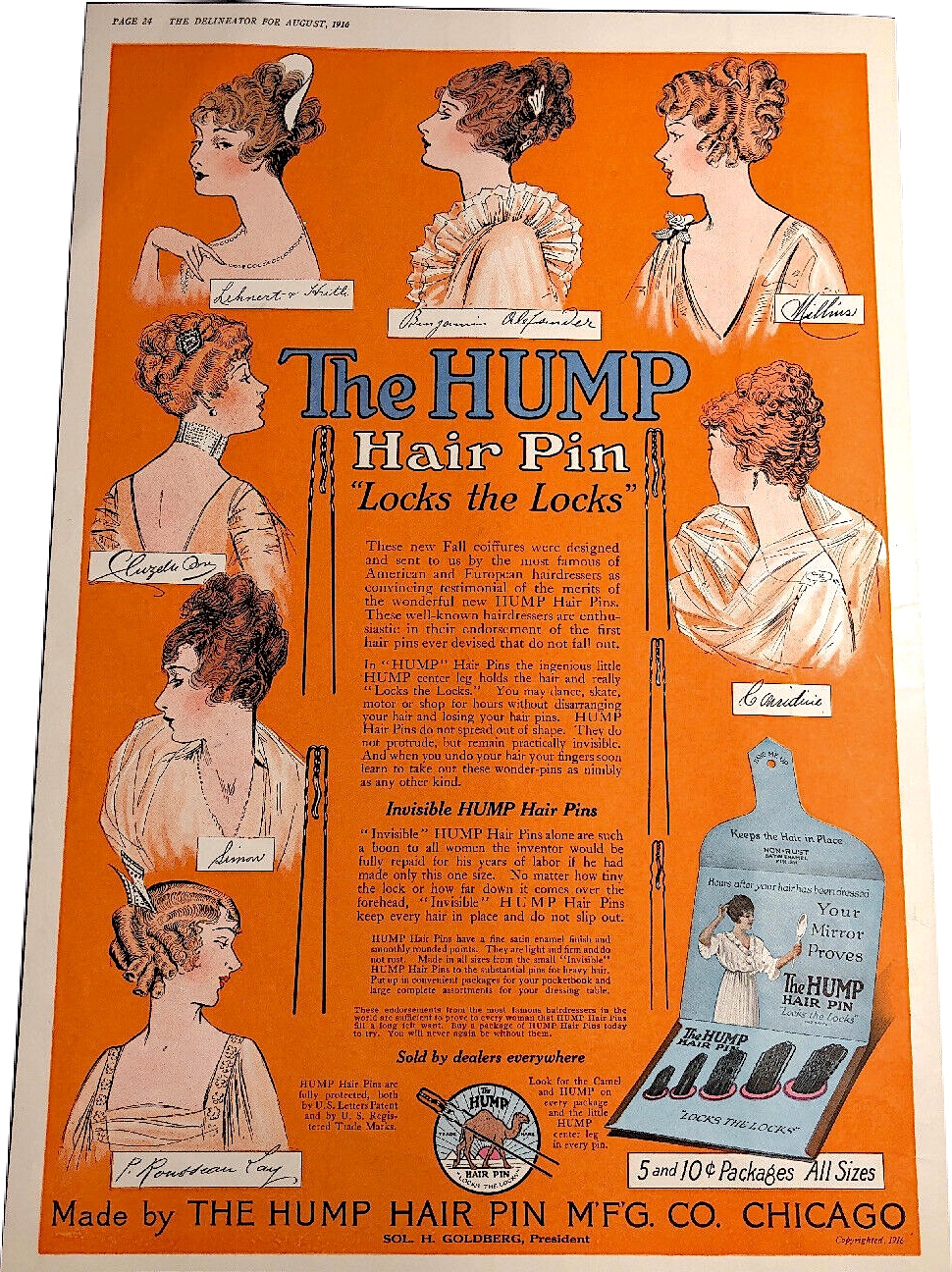

In 1903, shortly after procuring a patent for a three-pronged hair pin with a crooked or “humped” center leg (a tiny but significant innovation), Goldberg organized the Hump Hair Pin Company to deliver his creation to the women of the world. The product was, he claimed, “the first hair pin ever devised that does not fall out,” as the titular hump could more effectively grip and hold the hair in place, or “Lock the Locks,” as the slogan went.

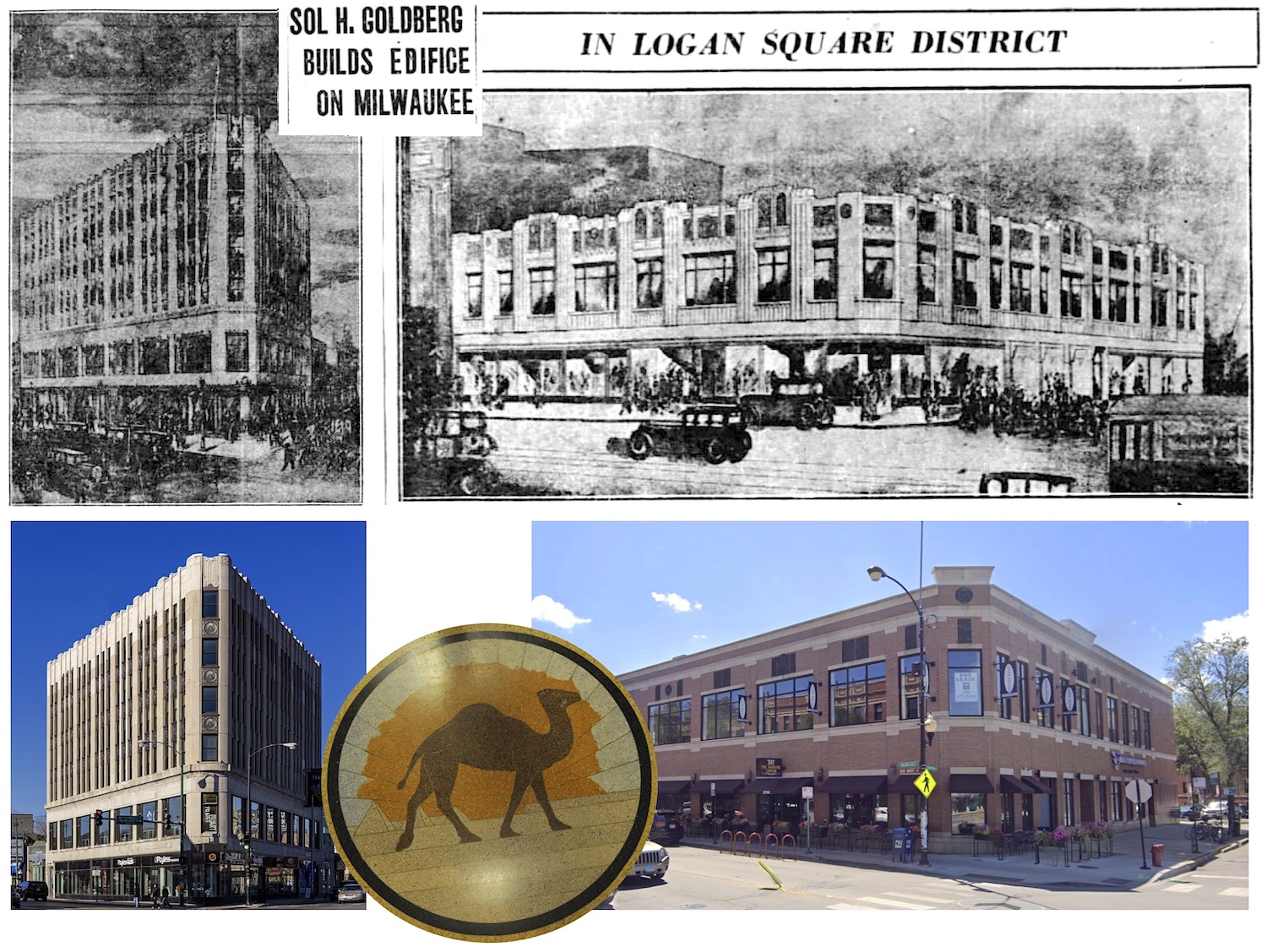

It might not have been the Model T, but in the heyday of the up-do, the Hump Hair Pin—recognized for its familiar “good luck camel” logo—helped make Sol Goldberg a multi-millionaire. From the 1910s through the 1930s, he became a fairly prominent public figure in Chicago high society, twirling his manufacturing success into high-profile real estate ventures and political influence. He even briefly ran for mayor in 1935, and had the acid tongue and ethical shortcomings to suitably fit the role. Unfortunately, his campaign slogan— “I Don’t Know Anything But I Know What I Don’t Know and I’ve Got Ideas”—wasn’t quite as effective as his old advertising taglines.

[The current “Hairpin Lofts” at Milwaukee Ave. and Diversey retain the decorative camel motif from its days as an Hump Hairpin office building in the 1930s]

History of the Hump Hair Pin Co., Part I: Meet the Goldbergs

During that 1935 mayoral race, Sol Goldberg told the press that he was 48 years old—meaning he was born in 1887. A few years earlier, though, on a government passport, he lists his birthdate as 1880, and on his gravestone at Chicago’s Rosehill Cemetery, it says 1875-1940. I suppose he could have been backpedaling through life in the Benjamin Button fashion, but it’s probably more likely that Sol was willing to manipulate his own timeline to help perpetuate the myth of the “Hair Pin King”—which makes uncovering the real, arguably more interesting truth of his life all the more challenging.

Setting aside the birthdate confusion, we do know with some confidence that Solomon Harry Goldberg was a first-generation American, one of seven kids born to Jewish immigrants Benjamin W. Goldberg and Ellen Goldberg (née Applebaum). And judging by the family’s surprisingly numerous mentions in local newspapers, this version of “The Goldbergs” was more of a Steppenwolf stage drama than a network sitcom.

Sol’s father Benjamin was a traveling salesman, and this led to a regular uprooting of the family, from New Orleans to New York, Philly to Omaha. Sol was supposedly born in Cincinnati, but the Goldbergs also spent much of the 1880s in Chicago, where papa Benjamin became something of an obsessed “stage dad,” putting all his focus into promoting the budding acting career of his eldest daughter, Amelia Nadage Goldberg (1862-1950), better known by her stage name Nadage Doree.

Nadage set a high bar for her siblings in terms of achievement and notoriety. When Sol was still a kid, his big sis was already performing in the stage company of arguably the world’s most famous actress and socialite, Lillie Langtry (aka the “Jersey Lily”)—often taking on the saucier roles in major productions in New York and abroad. In 1888, after being released from said company, Nadage grabbed national headlines when she filed a lawsuit over the dismissal, claiming the older Ms. Langtry was just “jealous” of her youthful beauty and superior talent. Later in life, the increasingly outspoken Nadage Doree became a leading activist for Jewish and feminist causes, writing several books on those subjects and getting herself famously arrested for interrupting a Teddy Roosevelt speech in 1905—pleading with him to defend Russia’s persecuted Jews.

If Nadage’s theatrics didn’t influence Sol Goldberg, his father’s certainly must have—for better or worse.

Benjamin Goldberg appears to have been a troubled soul, and his relationships with his wife and children look tumultuous at best. In 1886, after 30 years of marriage, he even took the highly unusual step of publicly filing for divorce (unsuccessfully) from Ellen Goldberg, claiming she treated him with “cruelty” and that she had “poisoned the minds of their children and turned their affection for him into hate and bitterness.”

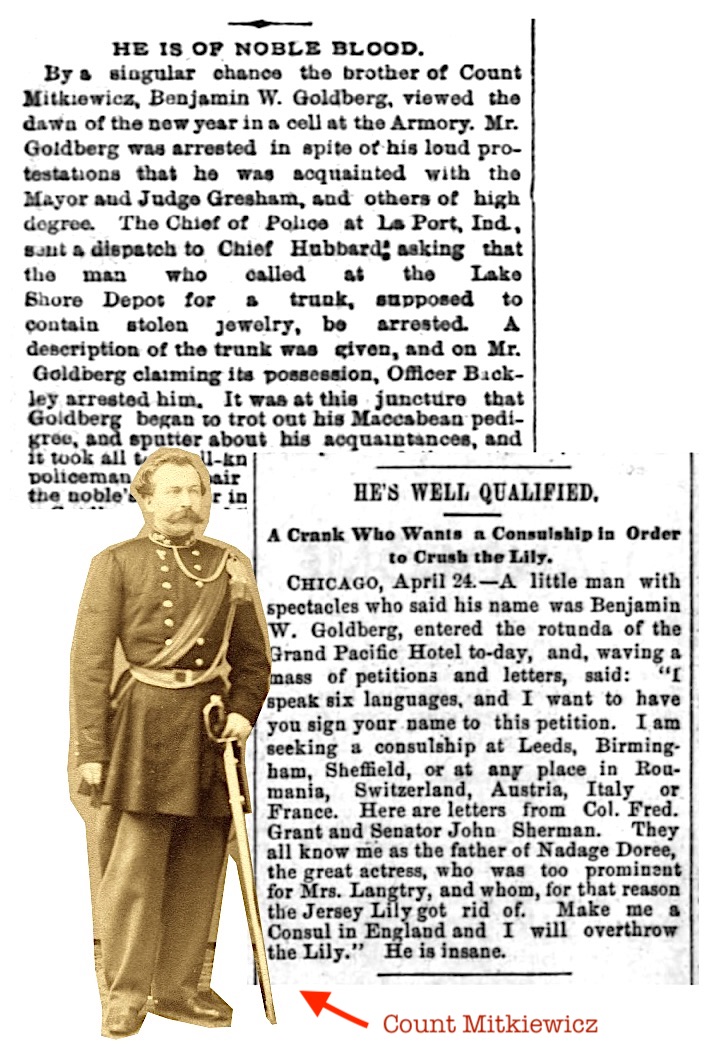

Things got worse on New Year’s Eve of 1888, when Benjamin was arrested by Chicago police on suspicion of moving stolen jewelry. In a hysterical frenzy, he denied the charge, and shouted that he was personal friends with the mayor and should be freed. He also repeated an ongoing bizarre claim that he was the long lost brother of the Polish dignitary Count Mitkiewicz, who’d recently gained international fame for negotiating trade deals with China. Chicago’s Inter Ocean newspaper openly mocked Goldberg for this, sarcastically referring to the prisoner’s supposed “noble blood.”

“Goldberg is a peddler by trade,” the paper said. “That is to say he deals in spectacles, second-hand and tawdry jewelry, and other goods of a like character. . . . The police do not for one moment imagine that Poland’s richest blood swashes about in his arteries.” As the world would later learn, the celebrated Count Mitkiewicz of Poland was actually a fraud and a con man himself, so perhaps Benjamin Goldberg’s claim of a relation to him wasn’t total hogwash, after all.

In any case, the Inter Ocean further ridiculed Goldberg, assessing his time in Chicago as “one long understudy of his daughter’s talent. This young woman is an actress, and her dear papa buttonholes every man within his reach and toots her praises.”

That abrasive reputation seemed to be cemented a few months later, when Benjamin (described as a “a little man with spectacles”) reportedly stormed into Chicago’s Grand Pacific Hotel, waving around a stack of petitions and letters all supposedly recommending him for a consulate position in Europe. “They all know me as the father of Nadage Doree,” Goldberg proclaimed—“the great actress who was too prominent for Mrs. Langtry, and whom for that reason the Jersey Lily got rid of. Make me a Consul in England and I will overthrow the Lily!” The strange incident was picked up by newspapers nationwide—like an embarrassing viral video of its day—each re-printing concluding with the same damning three-word assessment of Mr. Goldberg: “He is insane.”

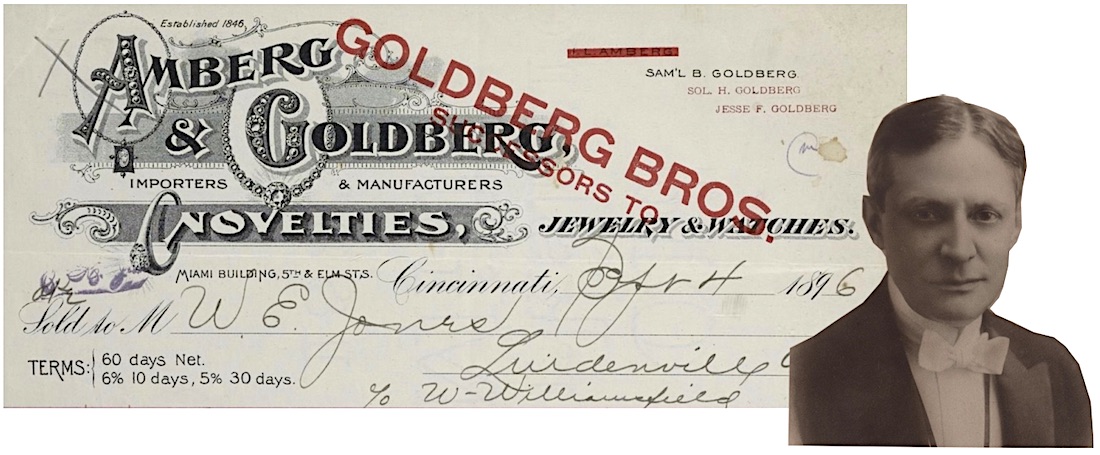

By the early 1890s, the dysfunctional Goldberg family was back in Cincinnati, and young Sol had his first job working with his older brothers Samuel and Jesse in a jewelry business of their own. The boys’ mother Ellen died in 1894, and with their father offering questionable stability, the kids were probably their own best support system.

[1896 Letterhead for the Goldberg Bros. of Cincinnati, successors to the jewelry firm of Amberg & Goldberg. Eldest brother Samuel Goldberg, right, is listed as a head of the business, along with his brothers Jesse F. Goldberg and the future Hairpin King, Sol H. Goldberg]

To make his own mark, Sol wound up essentially combining his brothers’ business acumen with his sister’s flair for the performing arts. Unlike his father, he had no interest in living vicariously through others.

Our first real glimpse at the future “Hairpin King” comes in 1896, when a newspaper in Logansport, Indiana mentions that “Sol H. Goldberg, of the firm Goldberg Bros., Cincinnati, O., one of the most popular as well as handsome traveling salesmen who visits Logansport, came to town today.” Another weirdly fawning account in the same paper describes young Sol (who was either 21, 16, or 9 depending on your preferred birthdate) entertaining a local ladies organization with “a meritorious performance on the piano. He also proved himself an adept juggler and amused all present juggling silver spoons.”

This entertainment portion of Goldberg’s life wasn’t just a brief teenage flirtation either. In 1902, when Samuel and Jesse Goldberg closed up the Cincinnati jewelry business, Sol moved west to the town of Danville, Illinois (about 126 miles due south of Chicago), where he continued performing—likely often in blackface—at minstrel shows put on by the Elks and other lodges. After one particular event that year at the famed Plumb Opera House in Streator, Illinois, special guest Sol H. Goldberg was singled out in the local paper as “one of Cincinnati’s best entertainers. . . The specialties which he introduced contained a number of novel features and these added much to the pleasure of the evening’s entertainment. He gave imitations of various things with his mouth and with a set of rattling bones; told a hard-luck story with the aid of piano; played a tune by rattling silver spoons together; and indulged in a monologue. Mr. Goldberg was both clever and graceful in his work.”

None of those silver spoons, mind you, had been present in his mouth at birth. But as a seasoned jewel peddler, showman, and schmoozer, Sol Goldberg was at least getting by financially long before he put a wrinkle in a hair pin.

II. Eureka! A Hump!

When it comes to famous inventions and discoveries, the public always prefers a simple explanation—an apple on the head; a bolt of lightning and a kite—to the more nuanced, multiple-step process of the scientific method. As a salesman, Sol H. Goldberg understood that romance of brevity better than anyone (including the Made In Chicago Museum, obviously), which is why his overnight “discovery” of the Hump Hairpin lived on for decades as a favorite inspirational anecdote for ambitious businessmen and would-be entrepreneurs. The tale was never told exactly the same way twice, but it always celebrated the idea of an ordinary guy having an extraordinary solution to an age-old problem.

In 1941, America’s original self-help guru Dale Carnegie—best known for his book How To Win Friends and Influence People (and less known for changing the spelling of his name from “Carnagey” in order to improve his own perceived social status)—recycled the story in his syndicated newspaper column.

“Thirty-six years ago, there was living in Chicago a slight, wiry, energetic boy by the name of Sol H. Goldberg,” Carnegie wrote. “He picked up a copy of the Saturday Evening Post and read an article on inventions. He came across this sentence: ‘A fortune is beckoning to the man who will invent a satisfactory hairpin.’** When he finished reading the article, he got up and examined his mother’s hairpins. Right then and there he started out to invent a ‘satisfactory hairpin.’ No monkeying around for that boy!”

**We couldn’t find any such article in the Saturday Evening Post archives, but the passage in question does appear in a book called Hints To Inventors, written by Dr. Robert Grimshaw and first published in 1892. The exact wording, reprinted in the book’s 1907 edition (well after Sol had already patented the hump), reads: “A fortune awaits the man who will invent a satisfactory hairpin—a pin, that is to say, which will really hold the hair in place and not ‘come loose.’ Hundreds of patents have been granted for as many different patterns of hairpins, but not one of them meets this requirement. The weekly consumption of hairpins reaches far into the millions. The new invention must go in easily, only come out when the wearer desires, and must not split or tear the hair.”

Other versions of the Sol Goldberg story, such as one recounted in a 1935 Chicago Tribune piece and later in The Complete Home Book of Money-Making Ideas (1954), place him as a hapless, self-educated bell boy working in a Cincinnati hotel at the time of his magazine-inspired Eureka moment—although the Tribune does at least note that this is merely how Goldberg told the story publicly. “To his intimates,” the paper noted, “the Hair Pin King tells a more pungent anecdote of the lowly origin of the hump hair pin.”

We’ll never know the actual pungent truth, unfortunately, but we DO know that the concept of a fastener with a “hump” had actually existed for quite a few years before Sol Goldberg—bell boy, singer, salesman, or otherwise—came up with his in 1903.

Since as early as 1890, in fact, the DeLong Hook and Eye Company of Philadelphia had been manufacturing and widely advertising its “Hump” hook-and-eye fastener. That product was designed and patented for fastening women’s garments, rather than their hair, but the leap from one to the other wasn’t exactly the Snake River Canyon. Not surprisingly, Frank DeLong would eventually recognize the similarities, as well, but because he had never ascribed the “hump” name directly to his company’s own line of hair pins, he was never able to win any of his later trademark disputes with Goldberg (oh which there were many).

As for the immediate cash windfall of the Hump Hair Pin . . . well, that was actually part of the myth, too.

By 1904, Goldberg had lined up some big-time investors in his new Hump Hairpin Company, including its first vice president, Thomas Taggart, a former Mayor of Indianapolis and standing Chair of the Democratic National Committee. Factories were initially planned for Danville and Joliet, and some additional manufacturing was contracted out to a plant in Providence, Rhode Island. For quite a few years, though, the whole project basically moved at a snail’s pace. An invention alone does not a business make.

[Left: Sol Goldberg’s first “humped” hair pin patent, 1903. Right: His tweaked design, developed in 1909 and patented in 1915, just before mass production finally began. The original design was described as “a simple, cheap, and easily-made hair-pin made of ordinary wire; one that will be concealed when placed in the hair, and one that will be firmly held in the hair by its peculiar construction.”]

Between 1907 and 1912, with hairpins mostly moved to the back burner, Goldberg actually took an inexplicable and extensive foray into the roofing business, collecting about a dozen patents related to the industry, including an ornamental, pre-constructed material that could “simulate tile and shingles in appearance.” By 1910, he had also purchased a Chicago roofing business called (for some reason) the West Coast MFG Co. The venture helped legitimize him as a business owner for the first time, and in all likelihood, it was the roofing that really built the foundation—if we’re mixing architectural metaphors—for what came next.

In 1915, Sol became an early partner in the Lubliner & Trinz chain of movie houses, which would go on to operate beloved Chicago venues like the Biograph Theater, Congress Theater, and Davis Theater, among many others. That same year, ground was broken on another important new building—a modern factory that would finally be able to produce Hump hairpins on the scale required for national distribution. The choice of location for that factory, however, was groundbreaking in and of itself.

III. Prairie Avenue

“Hump Hair Pins are beautifully made. Lightweight and extra strong. Flexible and dainty enough for the most fastidious woman. Smooth as satin from end to end. Never pull or break the hair. Never feel heavy or tight. They hold securely the heaviest or lightest hair with the fewest hair pins. And they’re the most economical you can buy because you don’t lose them.” —advertisement, 1917

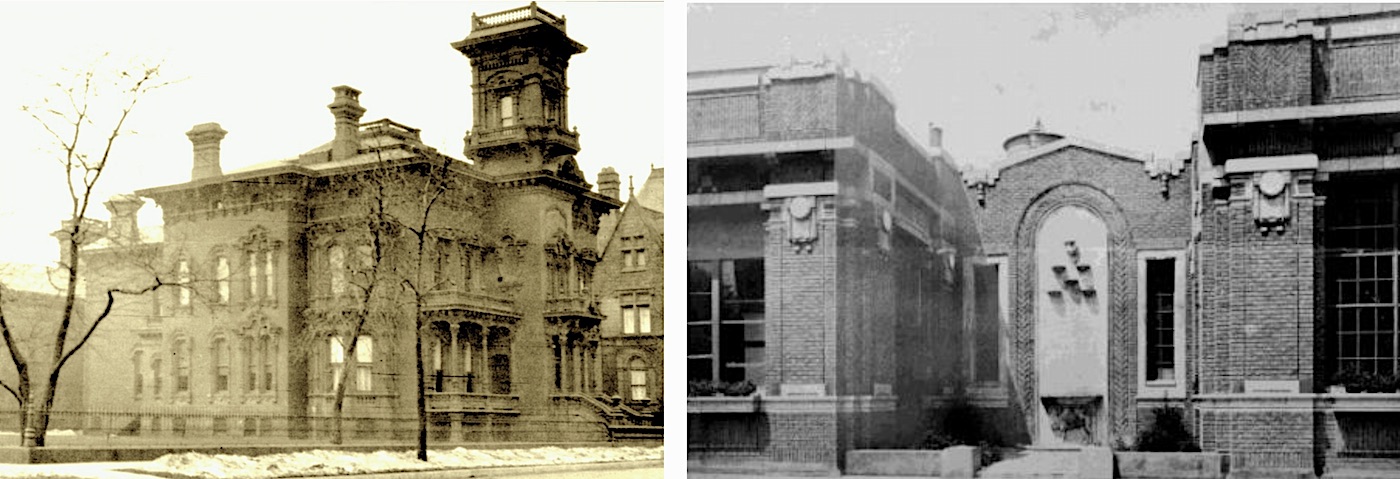

The Prairie Avenue District of Chicago, on the Near South Side, was the richest residential area in the city during the late 1800s, known for a “Millionaire’s Row” of mansions that included the homes of Marshall Field, George Pullman, John B. Sherman, and John J. Glessner. By 1915, though, the commercial and industrial reach of downtown was starting to push into the neighborhood, and the Hump Hairpin Manufacturing Company basically kicked the gates down.

[Left: The mansion of Samuel W. Allerton, which was torn down in 1915 to make room for the Hump Hairpin factory, right, at 1918 S. Prairie Ave., opened in 1916]

That year, Sol Goldberg purchased the land at the northwest corner of Prairie Avenue and 20th Street, leveled the old estate of businessman Samuel W. Allerton, and hired the great industrial designer Albert Alschuler to build a one-story concrete factory in its place, at the cost of $250,000. According to the journal of the Glessner House Museum (located just down the street), the Hump Hairpin plant was the “first large-scale commercial intrusion on Prairie Avenue,” and it inspired many more businesses to follow suit.

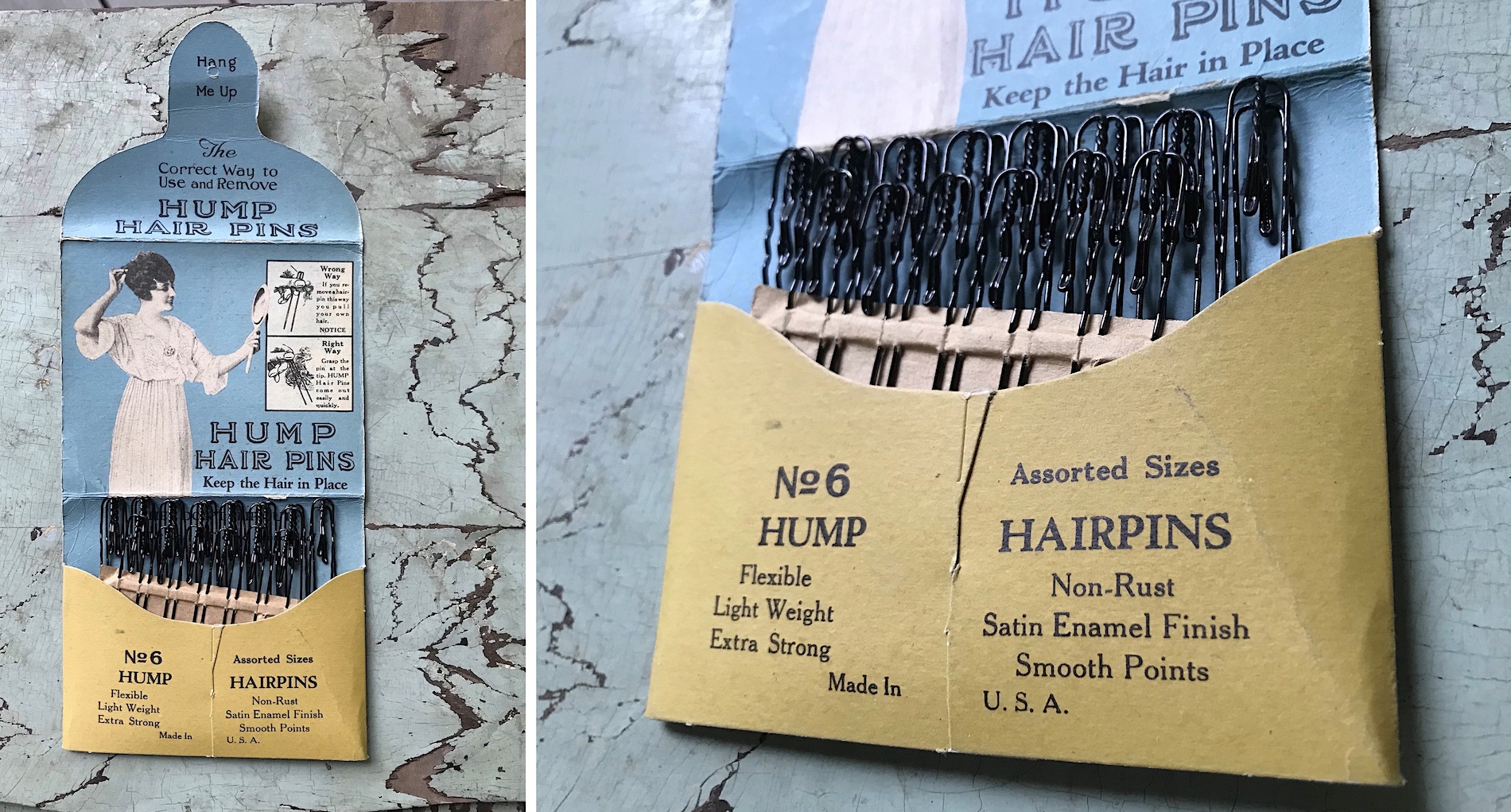

For whatever reason, after 13 years of slow progress, Goldberg was finally ready to get over the proverbial hump and invest in the hairpin business—no expense spared. Not only was the new factory operating 24 hours a day by 1916, but it also housed a brand new pin-making machine—eventually patented by Goldberg— that could churn out 125 hairpins per minute, or 180,000 in a day. Another machine, also patented by Goldberg, was made solely for “counting, arranging, and packaging hairpins or like articles” into display boxes like the one in our museum collection—featuring the company’s trademarked camel logo. Perhaps the greatest new investment of all, however, was in marketing, as the “Hump” brand went from obscurity to ubiquity in a matter of months, seen in ads from Washington state to Washington, D.C.

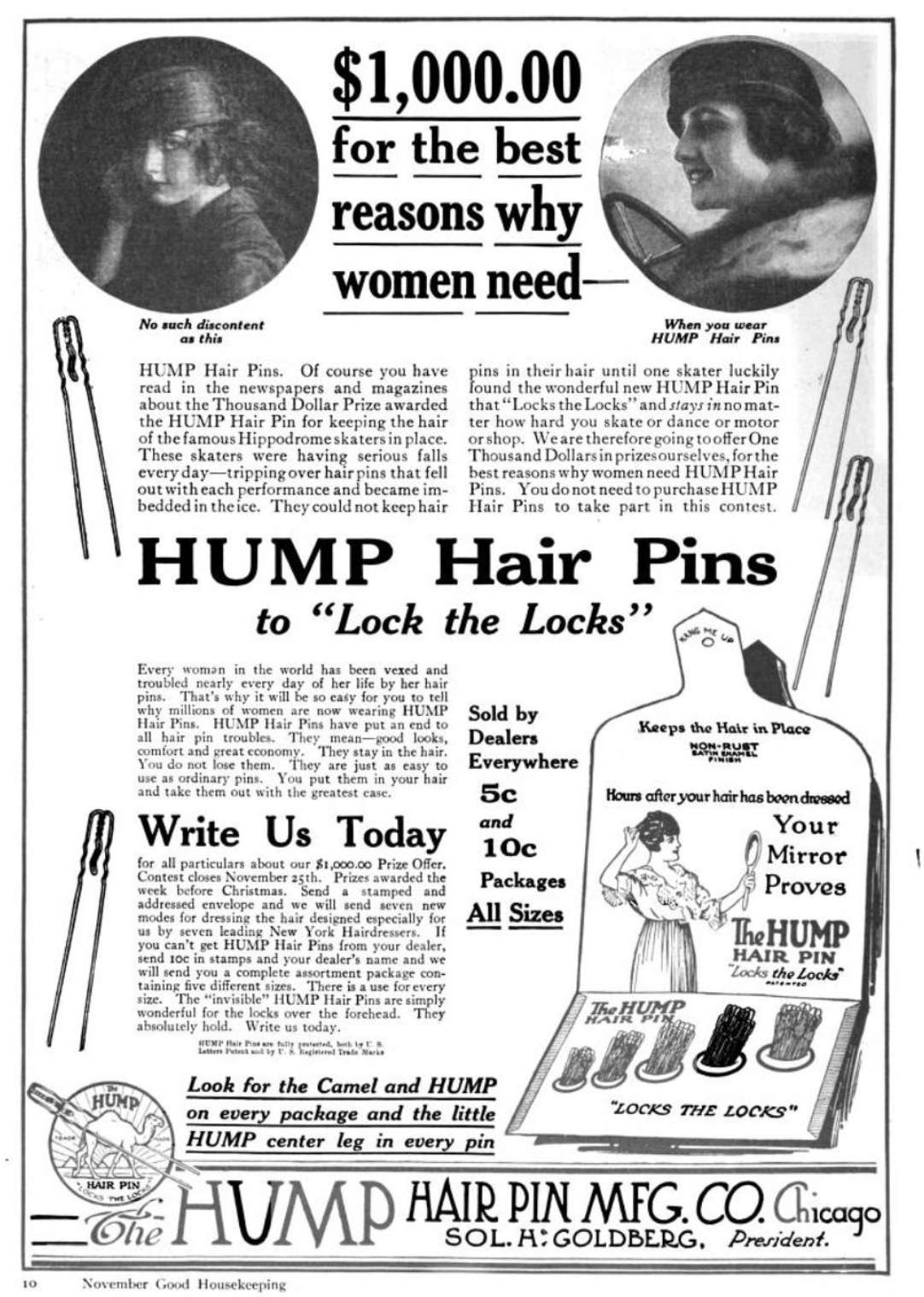

As part of that first promotional blitz, the company promoted a “$1,000 Prize” the Hump Hair Pin had supposedly been awarded by the famous ice skaters of the “World’s Greatest Stage: the New York Hippodrome.”

As part of that first promotional blitz, the company promoted a “$1,000 Prize” the Hump Hair Pin had supposedly been awarded by the famous ice skaters of the “World’s Greatest Stage: the New York Hippodrome.”

Apparently, the women in this figure skating performance troupe were constantly losing hair pins during their jumps, which would then stick in the ice and trip them up. “No solution was forthcoming,” one ad read, “until the recent advent of the wonderful new hair pin that has taken the feminine world by storm—the HUMP Hair Pin that ‘Locks the Locks.’

“With HUMP Hair Pins, women dance, skate, motor or shop for hours without disarranging their hair or losing their hair pins. . . . They’re made in all sizes, from the small ‘invisibles’ that are wonderful for the new curls and side locks, to the substantial sizes for heavy hair. Beautifully finished and put up in 5 cent and 10 cent packages for your pocket book and your dressing table.”

[Hump Hair Pin magazine ads from 1917 (left) and 1921 (right)]

The more colorful the ads got, the more popular the HUMP became, which in turn required extra acreage for the Prairie Avenue factory. Things were going well in Sol Goldberg’s personal life, as well, as he announced his engagement in 1921 to a Russian-born fashion designer named Ruth V. Kahan—the woman who would arguably plot the course, and identity, of the company every bit as much as Sol himself.

IV: Sol & Ruth vs. The Bob

“Irene Castle cost me $2 million when she bobbed her hair.” —Sol H. Goldberg

After four or five years of skyrocketing success, the Hump Hairpin Company was somewhat blindsided by a dramatic change in its clientele as the 1920s began. A decade earlier, it was estimated that 35,000,000 women in the U.S. alone used hair pins. Most of them had long hair, which required about 16 to 23 hair pins to hold in place. Factor in that most people also still treated said pins as disposable and replaceable (an estimated 65,000,000 were lost or thrown out every DAY, with about 50 lying on the ground on every average city block), and Sol Goldberg had what seemed to be a juggernaut of a business model; making more hair pins, he claimed, than anybody else on Earth.

Then, in a trend often attributed to the ice dancer Irene Castle, the era of the short bobbed hair-do began, and the stylings of the Jazz Age flapper along with it.

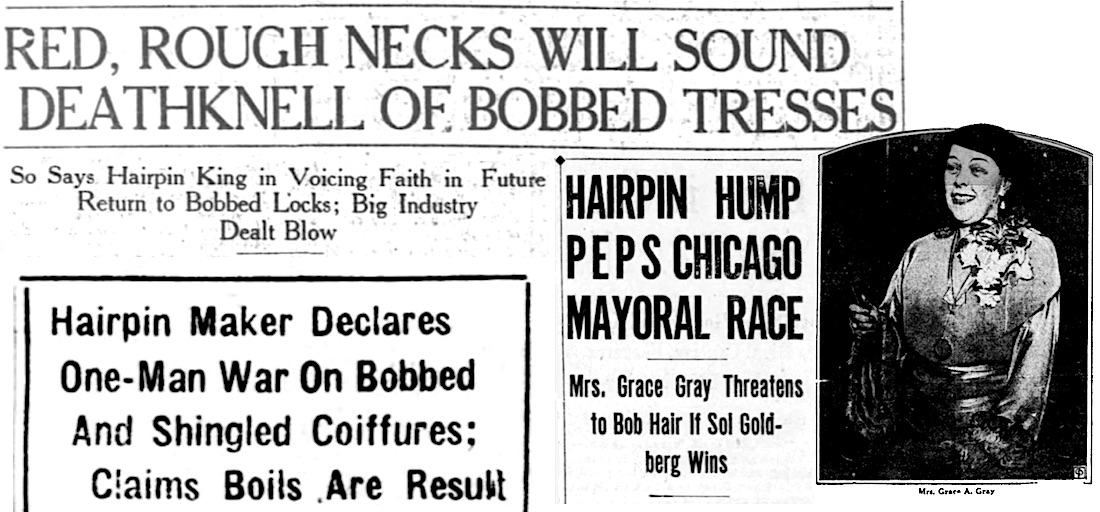

“I almost had heart failure when bobbed hair grew more popular,” Goldberg said in 1924, adding that he predicted it would soon lose its favor. A year later, when the bob was only increasing in popularity, a bitter Sol—while on a European jaunt in London—told the British press that he was declaring war on the style. “Bobbed hair causes shaved necks,” he said. “Shaved necks cause ingrown hair. Ingrown hairs cause boils. Just look in the mirror,” he instructed one of the female interviewers, “and see how your shaved neck makes your chin stick out.”

“I almost had heart failure when bobbed hair grew more popular,” Goldberg said in 1924, adding that he predicted it would soon lose its favor. A year later, when the bob was only increasing in popularity, a bitter Sol—while on a European jaunt in London—told the British press that he was declaring war on the style. “Bobbed hair causes shaved necks,” he said. “Shaved necks cause ingrown hair. Ingrown hairs cause boils. Just look in the mirror,” he instructed one of the female interviewers, “and see how your shaved neck makes your chin stick out.”

Sol’s nasty views on the bob never really changed. As late as 1935, one of his opponents for the Republican mayoral candidate nomination—a woman named Grace Gray—seemed to know it was still a sore subject. She told reporters that if Goldberg bested her for the nomination, she would turn her long hair into a bob out of “sheer disgust.”

“I’ll have my hair bobbed,” Gray announced. “I’ll get my daughter to bob her hair. I’ll ask the ladies of the Eastern Star and my bridge club to do the same thing. Let me tell you, those crooked little gimcracks will rise up to haunt Mr. Goldberg, who thinks he’s the only one who can give Chicago a business-like administration. Who made his business, anyway?”

In response, a surly and dismissive Goldberg said, “Build a better mousetrap and the world will beat you out of it. Give it a better hairpin and women will start bobbing their hair. . . . I never thought the hump in my hairpins would become a political issue. Why doesn’t she talk about taxation, the Great Lakes waterway or traffic conditions?”

[Highlights from Sol Goldberg’s personal war with “the bob.” Top headline: 1924, Bottom Left: 1925, Bottom Right: 1935, with picture of mayoral race opponent Grace Gray]

Predictably, the newspapers generally mocked Mrs. Gray (who was genuinely 48 years old rather than pretending to be) while admiring Goldberg for having “converted a piece of enamel wire into a $15,000,000 fortune.”

“And I’m resourceful, too,” Sol told them. “When black hair became blonde overnight did I cry? No. I had blonde hairpins galore quicker than you could say ‘a humped-back Herring!’ And when the bobbed hair craze came along I invented the bobbie pin. That’s having ideas.”

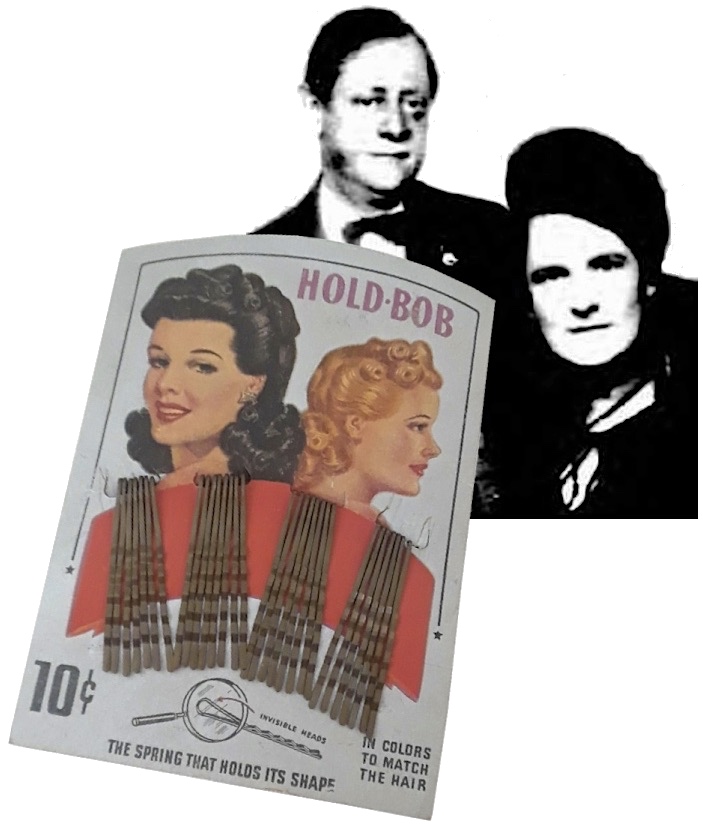

No one fact-checked Goldberg on that last claim, but it’s probably safe to say he did not invent the bobby pin. That innovation gets credited to a whole bunch of folks—from Sol’s old rival Frank DeLong to Luis Marcus in San Francisco. As for the bobby pin sold by the Hump Hair Pin MFG Co.—marketed as the “Hold-Bob”—not even that concept, it seems, was Sol’s.

Many years later, his widow Ruth acknowledged that she’d come up with the idea for the Hold-Bob while out for a leisurely game of golf. She had seen a woman playing at the next tee who had a short bob, and noticed she was using a bent piece of plain balin wire as a makeshift hair clip. Ruth proposed something similar to Sol, and—with Hump’s market share sinking—he put the new bobby pins into production.

One gets a sense that Ruth Goldberg was always more of an active participant in the Hump Hairpin business than her husband might have liked to let on.

V. The Camel Casts a Shadow

In the summer of 1929, having apparently survived the great bob scare, the Goldbergs made an aggressive business move, organizing the Chain Store Products Corporation, and making the Hump Hair Pin MFG Co. the first subsidiary of that new, bigger venture. The idea was to collect similarly minded manufacturing businesses across the country to create a hub for “popular priced products distributed through chain stores,” i.e., cheap toiletries.

The collapse of the stock market a few months later could have proven disastrous, but the business actually still spun a profit in 1930, although it’s unclear just how many other subsidiaries Chain Store Products ultimately acquired.

The collapse of the stock market a few months later could have proven disastrous, but the business actually still spun a profit in 1930, although it’s unclear just how many other subsidiaries Chain Store Products ultimately acquired.

“I don’t like to carry all my eggs in one basket,” Sol Goldberg later said. “I have invested my money in a number of other enterprises. If one loses money for a while, the others make up for it. I use my money and the loyalty and services of other people, and we are all better off.”

Sol’s apparent confidence at the outset of the Great Depression is most evident in his real estate maneuvers. Between 1929 and 1931, he commissioned the construction of a pair of noteworthy buildings in Logan Square; a two-story, $250,000 Egyptian-style office complex at Milwaukee Ave. and Spaulding Ave.; and a six-story, $600,000 “flat-iron” high-rise at the intersection of Milwaukee Ave. and Diversey, which was later became the Morris B. Sachs Department Store. The smaller of the two buildings is fairly unrecognizable these days, having had its art-deco facade removed years ago. The tower at Milwaukee and Diversey, however, has had a renaissance in the 21st century, fully restored and celebrating its origins. After two decades in disrepair, the building re-emerged as the “Hairpin Lofts” in 2012, maintaining the decorative Hump Hairpin camel motif built into the facade and lobby floor 80 years prior. Along with 28 apartments, the Hairpin Lofts includes 7,000 square feet of retail space and 8,000 square feet dedicated to the Logan Square Community Arts Center.

[Sol Goldberg office buildings, then and now. Left: 3414 W. Diversey Ave., now known as the Hairpin Lofts, complete with the original camel design in the lobby floor. Right: Block at Milwaukee Ave. and Spaulding; still standing today, but sans all the original facade.]

[Sol Goldberg office buildings, then and now. Left: 3414 W. Diversey Ave., now known as the Hairpin Lofts, complete with the original camel design in the lobby floor. Right: Block at Milwaukee Ave. and Spaulding; still standing today, but sans all the original facade.]

When it was still brand new, the “Hump” flat-iron building was a similar point of pride for the neighborhood, and something Sol Goldberg could hang his hat on as he made his first foray into politics in 1935.

“In local politics Mr. Goldberg is virtually unknown,” the Tribune reported at the time, “although he has an acquaintanceship with national political leaders. He insists that he does not seek the mayor’s chair for personal gain, but rather because he has been urged to run by friends who promise the backing of business and industrial interests.”

“I have ideas,” Sol told the paper, referencing his terrible campaign slogan. “And, what is better, I know what I DON’T know. I know enough about business to give the city a good, efficient administration and I know enough to surround myself with competent, experienced men who will follow out my ideas.

“I have faith in Chicago. I know that this city will continue to grow and prosper. To prove my faith, I have invested between seven and eight million dollars in real estate and construction during the last five years of depression.”

At the time, the Tribune claimed that the Hump Hair Pin Company employed 2,700 people between its plants in Chicago and England, and that Goldberg was a director or officer of at least 27 other corporations, with real estate holdings valued at $15 million.

Would the public be willing to vote for a completely inexperienced politician on the merits of his business fortunes? Well, that much is obvious. The story didn’t play out that way for Sol Goldberg, however.

Just a week after proclaiming his “faith in Chicago,” and mere days after sparring with fellow candidate Grace Gray over hair bobbing threats, Sol suddenly announced he was backing out of the race for the Republican nomination. On top of that, he strangely endorsed incumbent Democratic mayor Edward Kelly, who eventually trounced the Republican candidate Emil C. Wetten. At the time, Goldberg claimed that “his business as ‘Hairpin King’ is too important to him to risk his title in the coming city election.” The better likelihood is that he started to recognize what extra scrutiny might mean for himself and his business, which didn’t always operate on the up-and-up.

Sol H. Goldberg was a very clever and highly resourceful fellow, but like his father before him, he was sometimes willing to cut corners or fudge the truth for reasons beyond just harmless self-promotion.

On several occasions during his younger days, Sol reported robberies that didn’t always hold up under further examination. The same year he patented the Hump hair pin, for example, he claimed that $400 worth of diamonds (about $12,000 in modern money) had been stolen from him on a train outside Chicago while he had stepped away to smoke a cigar. A decade later, he accused two off-duty Chicago cops of beating and robbing him and his girlfriend after a traffic dispute. The cops told a different story, claiming Goldberg had brandished a gun and a scuffle had ensured, but that nothing had been stolen.

No one took much notice of those unusual incidents, but as Sol accumulated more wealth, more controversies followed—including repeated investigations and penalties for tax fraud from the IRS. Things got decidedly uglier towards the end of the Depression, as in the span of a few months in 1939, Goldberg was sued for $1 million in unpaid bonds and—in a wholly unrelated crackdown—got raked over the coals by a federal judge for worker exploitation within the Hump Hairpin MFG Co. . . . including a scandalous charge of child labor abuses.

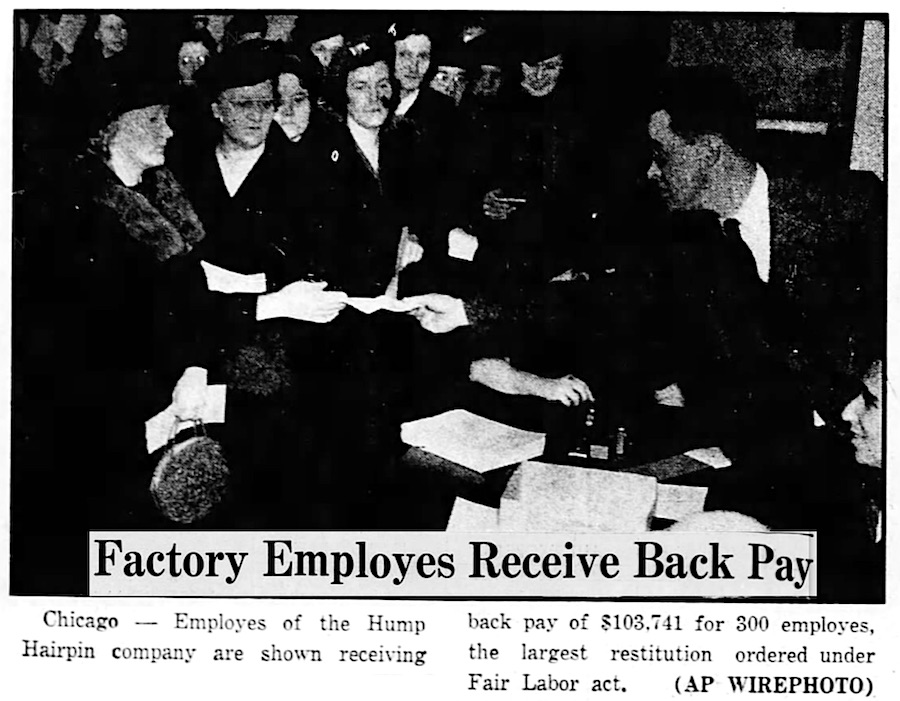

In what was then the “largest restitution case involving a single company since enforcement of the Fair Labor Standards Act began,” the Hump Hairpin MFG Co. / Chain Store Products Corp. was forced “to restore more than $100,000 in back wages” to about 300 of its work-from-home employees—a large majority of whom were actually children who’d been hired to insert hairpins into cardboard containers. Most of these child laborers lived within a mile radius of 35th Street and Halsted on the South Side, and were paid from 10 to 20 cents per hour.

At the time, the expanded Hump Hairpin plant at 1918-1936 S. Prairie Avenue was producing 56 million pins every day, and so the company blamed their hired distributors for employing the child workers, claiming it was out of their control. Unfortunately for Sol H. Goldberg, it would be the last story he’d ever spin for the press. By the summer of 1940, he was dead from unknown causes, and the Hump Hair Pin MFG Co. was headed into wartime production with the widowed Ruth Goldberg as its new president.

VI. Meet the Gaylords

“Any woman can outdo her husband in business if she wants to put her mind to it. The trouble is that enough women don’t want to put their minds to anything. They’d rather be dumb, because men like them better that way.” —Ruth Goldberg, aka Ruth Gaylord

Surprisingly to some, the death of the “Hairpin King” didn’t spell doom for the Hump Hair Pin MFG Company, although it did lead to its rebirth in many ways.

Surprisingly to some, the death of the “Hairpin King” didn’t spell doom for the Hump Hair Pin MFG Company, although it did lead to its rebirth in many ways.

As a wartime president, so to speak, Ruth Goldberg glided seamlessly into her new role, shifting from a housewife and mother of four to the head of a plant making pillbox and tank piercing shell fuses for the army.

“Now I manage the house, the children and the business,” she said. “I’d like to see a man take on a job like that.”

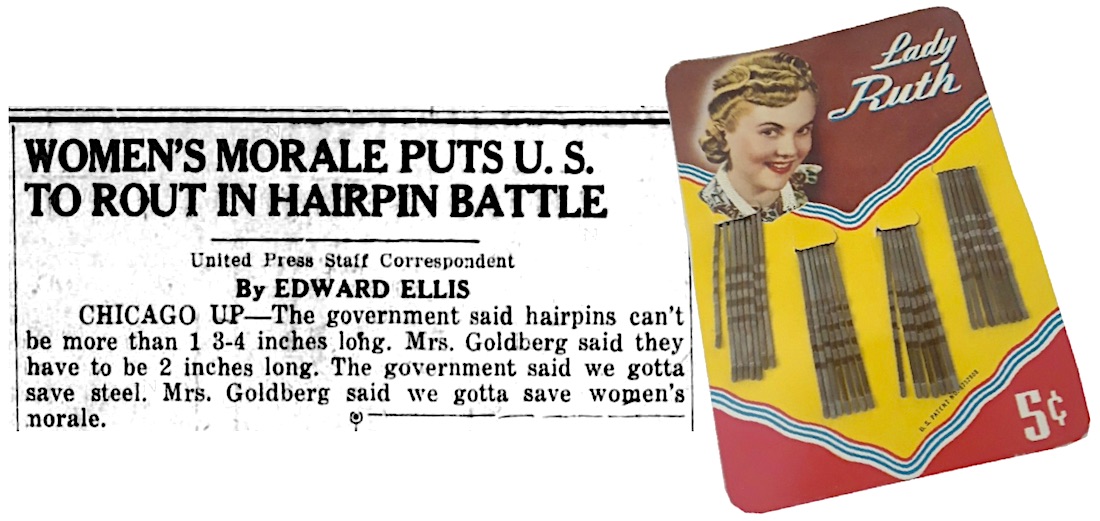

During the war years, the Hump factory’s normal production of hair pins was slashed by 80%, as the government not only demanded military production, but also an overall rationing of steel. Part of Ruth Goldberg’s mission, however, was to convince the government that hair pins actually were relevant and still vital to public morale on the home front.

“The people in charge,” she said in 1943, “had to be educated to the importance of hairpins. What men can’t understand is that hairpins, far from being a triviality, are an essential part of women’s apparel.” Her efforts worked, as she won some concessions on the number and length of pins her plant could start producing.

The Hump factory got some additional, much needed positive press in 1943, when newspapers caught wind of an amusing contest the plant’s machinists had created to pass the hours—giving names to their screw machines (as if they were thoroughbreds) and racing one another each day to see who could produce the most fuse parts: $3 to the winner, $1.50 for placing, 50 cents to the show. The “mechanical steeds,” as the United Press called them, had names like Shangri-la, the Gremlin, Man O’ War Jr., and War Admiral.

“Production is up 10 percent because of this,” Ruth Goldberg said. “And that’s without counting increased production due to the company’s incentive plan.”

By 1945, Ruth—whose sons Sol Jr. and James were serving in the Armed Forces themselves— had saved and revitalized her company’s reputation to the point that she was personally cited with an Army-Navy “E” Award for excellence in wartime production. Treating this almost like a baptism, Ruth Goldberg chose to guide the business back into peacetime under a completely new banner. The famed Hump Hair Pin and dull Chain Store Products Corp. were gone . . . and Gaylord Products Incorporated was born.

There is no clear indication as to what inspired the name change, but Ruth Goldberg clearly loved the ring of it—so much so that she changed her own surname to match it. Even after re-marrying a year later, to a New York industrialist named Jack Weaver, she carried on as Ruth K. Gaylord, and—stranger still—convinced her four adult children to become Gaylords, as well. Ruth even came to refer to her late husband Sol Goldberg as “Sol Gaylord,” a name he doesn’t seem to have ever used in his own lifetime. In line with that, the Rosehill Cemetery plot where Sol and Ruth are buried prominently features the Gaylord name, which must be confusing for the Hairpin King, wherever he may be.

Anyway, from 1946 onward, Gaylord Products and its primary brand name, “Gayla” also erased any trace of the old camel and “Hump” trademarks. The business continued producing cheap hair pins, as well as hair rollers, ties, bows, hair nets, etc.—many of them backed by patents collected by Ruth Gaylord and/or her son James, and most sold under the Gayla name.

There were about 900 employees still working at the old Prairie Avenue factory at the start of the 1950s, but those numbers began to tail off into the 1960s. In the end, the company formerly known as Hump Hairpin never did leave the plant that Sol Goldberg had built for it way back in 1915. It also never left the ownership of the family formerly known as Goldberg.

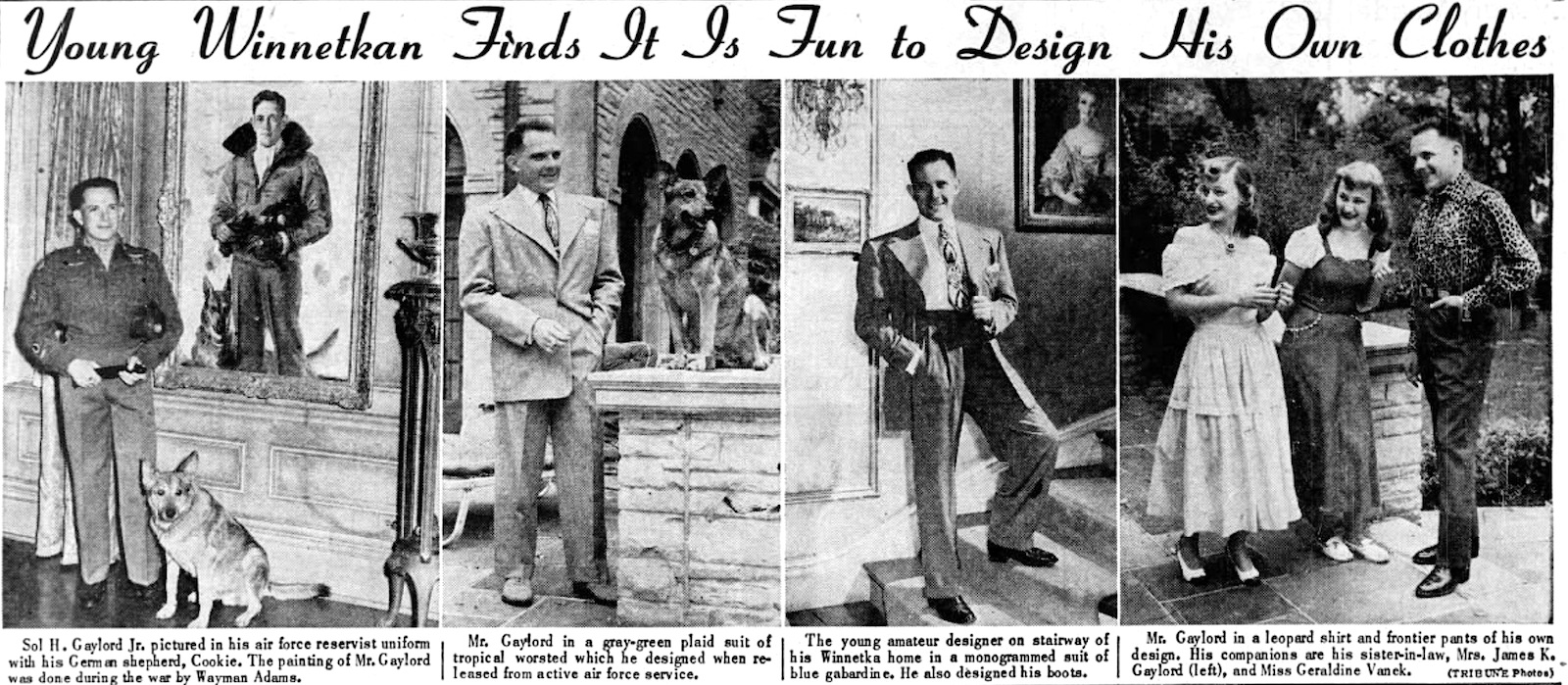

During the ‘60s, with Ruth K. Gaylord approaching retirement, her sons James Gaylord and Edward Gaylord took on executive roles. Eldest son Sol Gaylord Jr.—who’d gained some attention after the war as a clothing designer—was involved in the business, as well, but died suddenly in 1966.

[Sol Goldberg Jr. followed his mother Ruth’s lead after the war, changing his name to Sol H. Gaylord; trying his hand at clothing design (his mom’s original passion); and eventually working for the family business. His clothing design chops were featured in the Tribune in 1949]

The company’s final years, from the late ‘60s to the early ‘70s, were a slow march to doom, as competition from cheaper chain store imports from East Asia crippled the Gayla brands. It wasn’t an easy life for the workers at the Gaylord factory, either. One such woman, a 22 year-old named Audrey Griffin, was profiled by the Tribune in 1967. She had recently had her first child, and when she returned to work after maternity leave, she was moved from her old job inspecting hair rollers to a new one, “catching” hair pins.

“Her responsibility: Seven machines which drop hair pins onto rods,” the Tribune explained. “Mrs. Griffin picks up an average of 200 rods an hour from each machine, then drops the rods into baskets and reloads new rods.

“‘I like my work,’ she says. ‘I don’t like sitting at home. I’m not used to it. I’ve worked since I was graduated from high school.’” Audrey’s daily shift went from 7 AM to 3:30 PM, Monday to Friday, and she was paid $1.40 per hour (about $10.50 per hour with inflation factored in).

“‘I like my work,’ she says. ‘I don’t like sitting at home. I’m not used to it. I’ve worked since I was graduated from high school.’” Audrey’s daily shift went from 7 AM to 3:30 PM, Monday to Friday, and she was paid $1.40 per hour (about $10.50 per hour with inflation factored in).

If Audrey was still working for Gaylord Products by 1975, she would have been part of the last team to carry out a vision started way back in 1903. The company appears to have been quietly dissolved around this time; its plant sold and employees let go. The Prairie Avenue facility was torn down in 1999 and replaced with new townhouses; the first residential construction on the historic street in 95 years.

When Ruth K. Gaylord died in 1979, her obituary made no reference to her significant contributions as a female executive in the male-dominated manufacturing world.

“We’ve had about enough of that ‘helpless little woman talk,” she once told reporters in 1946. “It’s time men let women in on what’s going on—and it’s time women tried to find out. . . . There’s one thing for sure, however. If women are dumb, it’s because their husbands made them that way.”

Sources:

“A Crank Who Wants a Consulship In Order to Crush the Lily” – Pittsburgh Dispatch, April 25, 1889

The Hairpin Lofts – Official Website

“He Is of Noble Blood” – The Inter Ocean, Jan 2, 1889

“At the Our Club: Young Ladies Entertained By the Members” – Logansport Reporter, April 25, 1896

A Jew in the Public Arena: The Career of Israel Zangwill, by Meri-Jane Rochelson

“Excellent Show by the Elks Minstrels to a Crowded House” – Streator Free Press, April 24, 1902

“To Make Hairpins: Big Company Organized in Illinois for that Purpose” – Mattoon Commercial, Feb 18, 1904

Hints to Inventors, by Robert Grimshaw, 1907

“Manufacturing Property Shows Much Activity” – Chicago Tribune, Sept 19, 1915

“Chicago Policeman Held as Auto Bandit” – Fort Wayne Weekly Sentinel, Sept 7, 1916

“Fight to See Who’s Entitled to Title of ‘Hump'” – The Day Book, April 29, 1916

“De Long Hook & Eye Co. vs Hump Hairpin MFG Co.” – Supreme Court of Illinois, April 21, 1921

“Red, Rough Necks Will Sound Deathknell of Bobbed Tresses” – Caspar Star-Tribune, Dec 28, 1924

“Hairpin King Deplores Bob” – Chattanooga News, Nov 1, 1924

“Hairpin Maker Declares One-Man War on Bobbed and Shingled Coiffures; Claims Boils are Result” – Pittsburgh Daily Post, April 14, 1925

“Want to Get Rich? The Place to Find Gold Is In Your Own Mind” – Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, Feb 5, 1950

“Sol H. Goldberg Builds Edifice on Milwaukee” – Chicago Tribune, May 26, 1929

Chain Store Products Corp. Initial Stock Offer – Decatur Evening Herald, July 9, 1929

“Builds Block at Milwaukee and Spaulding” – Chicago Tribune, July 26, 1931

“Goldberg Builds His Platform on Story of Hairpin” – Chicago Tribune, Jan 26, 1935

“Hairpin Hump Peps Chicago Mayoral Race” – Hammond Times (Indiana), Jan 29, 1935

“Goldberg to Quit Race” – Cincinnati Enquirer, Jan 31, 1935

“Sol H. Goldberg” – Reports of the U.S. Board of Tax Appeals, Vol. 36, 1937

“Suit for Million is Filed Against Sol H. Goldberg” – Chicago Tribune, July 13, 1939

“Hairpin Firm Agrees to Abide By Labor Laws” – Chicago Tribune, Dec 30, 1939

“Millionaire Hairpin Manufacturer Dies” – The Dispatch (Moline, IL), June 5, 1940

Dale Carnegie Column – Corpus Christi Caller-Times, June 10, 1941

“Women’s Morale Puts U.S. to Rout in Hairpin Battle” – Okemah News Leader (OK), June 25, 1943

“Hairpins Make Way for the War” – Detroit Free Press, April 17, 1943

“Name Machines After Thoroughbreds to Speed Production” – Freeport Journal-Standard, July 24, 1943

“Cited for War Work” – AP, May 15, 1945

“The ‘Little Woman’ Isn’t So Dumb, Just Acts That Way and Gets By With It” – United Press, Feb 4, 1946

“Young Winnetkan Finds It Is Fun to Design His Own Clothes” – Chicago Tribune, July 29, 1949

“Working Woman” – Chicago Tribune, Oct 23, 1967

“Spotlight on Prairie Avenue” – Glessner Journal, May 2016

Archived Reader Comments:

“in the late 60’s i met john gaylord, he wanted an idea how much the machine shop was worth, i gave him an estimate. one day after that i parked on cullerton to have lunch with the manager of vogue tire and saw a line of employees all the way around the corner. they were waiting to get into the building to get their things. they had been fired. a few days later i again met with john and gave him information on re buildings in the area. his mother put the building up for sale. also the building at 1528 s. state. after months a friend of mine bought the prairie avenue building. i had made an offer of $35,000.00 for state street and the lawyer called and had said he would buy the building and tear it down before he would let mrs. gaylard sell for that price. more time went by and the fellow from rubloff called me and said mrs gaylord would sell to me for my price. i bought the state street building with a partner lyman dunn for my price. never talked to john or his mother again. i had always told john his mother made a mistake in shuting down that way.” —tom murphy, 2019

James was quite brilliant with automotive engineering. He has a few patents, for example. I worked for him in the mid 70s after he moved his office from north Nevada. At that time he was making and selling aftermarket car engine items like the Compu Spark. I visited the plant in Tecate once. He could talk about autos for hours! He had a lot of contacts in the car biz as well.

James was in Paradise Valley / Scottsdale in the mid 70s, working with designers to market and sell aftermarket automotive parts via mail order. He had an office moved from North Nevada to Arizona for health reasons, I think. Ruth owned a large piece of land that was on Lincoln Dr by Invergordon, and the property tax on such a large lot became very expensive. I think they sold it as James got older. James and Ed were involved with the Gaylord Gladiator concept car in 1955-57, so James had a long history of interest in auto engineering. He was a big talker, so I don’t retain a lot of details, but he was fascinating to listen too. Hope Heinz von Krug who kept his car fleet in order was able to retire after all his service to the family. We got to borrow the Edsel to run errands close by. Good memories of an interesting family, although I only met James and Bonita and his attorney, David.

Hello Steve, My parents knew your uncle Sol and he occasionally visited our Wilmette home. Once Sol brought his nephew ,as a young child, over to our home-was it you?He told us that any broom that was worn down at one and was magic and could fly. We had a wonderful time hopping around the livingroom thinking that we were really flying. The nephew seemed like a really nice kid. We were about the same age. Was it you? The nephew asked if he could keep the broom and I felt guilty and selfish saying I wanted to keep it. We had a great time. Afterwards, my parents said it wasn’t magic and slightly spoiled the effect.

I have a box of Hold-Bob Hair Pins made in Canada by Hump Hairpin Manufacturing Co of Canada, St Hyacinthe, PO Canada. I can find no information about this and interested to know more.

I have a single shot pistol that I acquired from my uncle. It is a specially made pistol with the inscription:

“Made by Gaylord Products, Inc.

Chicago, 16, ILL”

This is an unusual pistol. I have never seen another like it nor can I find anyone who knows anything about these guns. I do know that my uncle ordered it and highly prized it.

I would appreciate any information about these pistols.

Terrell– I do not know the exact pistol but it was created by Sol Gaylord and his gun designer Jimmy Tollenger. I wish I could give you more info, but he collected many types of guns from Flint Lock rifles to the guns they designed, like a 6 shot derringer. Sol was my Uncle and I used to “play” with all these objects. Most were designed and created at the Prairie Avenue plant. I hope this helps some

My father worked at Gaylord in the early 60’s. He took me to the factory on Saturdays and put me in a box and let me ride on the conveyor. Jimmy, Ruth’s son used to come over to our house in Chicago with his Corvettes. I can remember him giving me rides in them. I found a bunch of hairpins at my mothers home the other day. I use them in my granddaughters hair. Imagine that!

I believe James went to Calif. to produced rock music in the 60’s. I remember talking to him about it on the phone then. He seemed like quite a kind person.His health Did not seem good around that time.He didn’t seem to be wild like his brother. I believe ,not 100 percent certain, his sister June Also died young at about age 50 .

I just posted but made a mistake in Writing my emAIL. Sol Gaylord Jr. was a friend of the family. Do you know Where I Could find out more information about him? I remember him as a rather crazy person who brought a gun over to our house. However, He Was very good with children. What Was the cause of his death? I thought He died of M.S. My mother said women wore him out. Going through my mother’s things after her death, I found some notes from “Guess who”. I wondered if they were from him.

I have six new packs of hump hair pens size 4. What is the value now

My father worked as the chief electrician at Gaylord Products until his retirement in the late 1970s. He knew Ruth Gaylord and her sons Sol Gaylord, Jr and Ed Gaylord; I don’t recall any mention of James. My mother worked as the nurse in the plant after WWII. She dated Sol, Jr for a while but met my father there in the late 1940s and they married in 1950, whereupon my mother quit work and stayed home to raise my brother and me. I remember going into the factory with my father twice a year, on Sundays, when he would have to walk through the entire factory to manually change the clocks from standard time to daylight savings time, and back again. I had many Gayla hair products that he brought home from work.